Abstract

Background

The aetiologies and pathogeneses of the joint diseases rheumatoid arthritis (RA) and spondyloarthritis (SpA) are still not fully elucidated. To increase our understanding of the molecular pathogenesis, we analysed the protein composition of synovial fluid (SF) from rheumatoid arthritis (RA) and spondyloarthritis (SpA) patients.

Methods

Fifty-six synovial fluid samples (RA, n = 32; SpA, n = 24) were digested with trypsin, and the resulting peptides were separated by liquid chromatography and analysed by tandem mass spectrometry. Additionally, the concentration of cell-free DNA (cfDNA) in the synovial fluid was measured, and plasma C-reactive protein (CRP) was determined.

Results

Three hundred thirty five proteins were identified within the SF. The more abundant proteins seen in RA SF were inflammatory proteins, including proteins originating from neutrophil granulocytes, while SpA SF had less inflammatory proteins and a higher concentration of haptoglobin. The concentration of cell-free DNA in the SF increased together with proteins that may have originated from neutrophils. Plasma CRP levels in both RA and SpA, correlated to other acute phase reactants.

Conclusions

The proteomic results underline that neutrophils are central in the RA pathology but not in SpA, and even though inhibitors of neutrophils (migration, proteinase inhibitors) were present in the SF it was not sufficient to interrupt the disease process.

Keywords: Proteomics, Synovial fluid, Rheumatoid arthritis, Spondyloarthritis, Cell-free DNA, Neutrophil extracellular traps

Background

The rheumatic diseases constitute a group of diseases that affects joints, ligaments, tendons, bones and can also show systemic manifestations. Rheumatoid arthritis (RA) and spondyloarthritis (SpA) are common inflammatory systemic joint diseases, with a prevalence of 0.5–1% and 0.1–0.3% respectively [1, 2]. RA is characterized by autoantibodies, including antibodies to citrullinated proteins (adaptive immune system) and neutrophil infiltration (innate immune system) of the synovial fluid (SF), whereas SpA is an autoinflammatory disorder of the innate immune system [3]. RA is twice as common in women, while SpA is twice as common in males [1, 4]. RA typically affects the small joints of the extremities and as the disease progress, cartilage and bone destruction can occur. In SpA, arthritis often affects the small joints of the spine, sacroiliac joints, and large joints of the extremities. As both diseases progress, cartilage and bone destruction often occur. Extra articular manifestations can include enthesitis, psoriasis, uveitis, and inflammatory bowel disease.

Diagnosis of RA and SpA is based on the clinical manifestations, genetic- and biochemical markers, accompanied by imaging techniques (radiographs and magnetic resonance imaging)[5, 6]. The two main serological tests for the RA diagnosis are rheumatoid factor (RF) [7], and anti-citrullinated protein antibodies (ACPA) [8]. Citrullination is a deamination of the side chain of the amino acid arginine catalysed by citrullinating enzymes, peptidyl arginine deiminases (PAD), in particular PAD4 and PAD2, of which single nucleotide polymorphisms in PAD4 are associated with RA susceptibility [9]. In RA both RF and ACPA are positively associated with the development of a more severe disease progression [10].

In SpA, MHC class I type HLA-B27 is present in up to 90% of the patients [11] and with less than 5% of the patients being RF or ACPA positive [12]. The two diseases can thereby be differentiated, but in rare cases the two diseases can co-exist [13]. In both diseases C-reactive protein (CRP) can be increased during active disease. Additionally, in spite the known differences, understanding of the RA and SpA aetiologies remains incomplete.

The protein composition (Proteome) of SF has previously been investigated. By use of 2D-gel electrophoresis Noh et al. [14] analysed the proteome of SF from RA patients early and late in the disease development and compared it with serum from healthy donors. They found several low molecular weight proteins in the SF compared with serum. In addition, they showed that tumour necrosis-alpha-induced Adipose-Related Protein and Zinc Finger Protein, ZNF658, could be detected as possible markers for RA in serum. Using LC-MS/MS based proteomics Mateos et al. [15] pooled SF from 20 RA patients and compared the results to a pool of 20 SF from osteoarthrosis (OA) patients. They found proteins related to inflammation to be dominant in the RA group, and proteins involved in the formation and remodelling of the extracellular matrix in the OA group. Similar results were obtained by Balakrishnan et al. [16] who pooled 5 RA and 5 OA samples, respectively, and also found increased amounts of inflammatory markers of the S100 protein family and matrix metalloproteinases (MMP) in the RA group.

Using quantitative proteomics, Mahendran et al. [17] analysed individual SF samples from 10 RA, 10 psoriatic arthritis patients (PsA) and 10 controls. PsA is a subgroup of SpA and, compared to the controls, MMP3 was highly increased in both disease groups. Overall, the SF proteomics of PsA and SpA were highly similar.

To determine the molecular differences in SF from RA and SpA patients, we characterized the proteome of 56 individual SF samples from RA (n=32) and SpA (n=24) patients. This allowed us to avoid pooling samples and thereby reveal minor differences between the disease groups. To compare proteomic results with biochemical parameters, C-reactive protein (CRP) in plasma as acute phase marker, and cell-free DNA (cfDNA) as SF pseudo-marker for neutrophil extracellular traps (NETs) were determined [18].

Methods

Human subjects and biobank samples

The clinical samples were collected under the project “INflamation in ARThritis (INART), approved by The Central Denmark Region Committees on Health Research Ethics (1-10-72-291-12). All patients were >18 years of age, fulfilling the ACR/EULAR criteria for RA and ASAS criteria for SpA, respectively [6, 19]. The diagnosis was supported by determination of RF (38% positive) and ACPA (42% positive) for RA patients, and by determination of HLA-B27 for SpA patients (84% positive) determined by Department of Biochemistry at Aarhus University Hospital, Denmark.

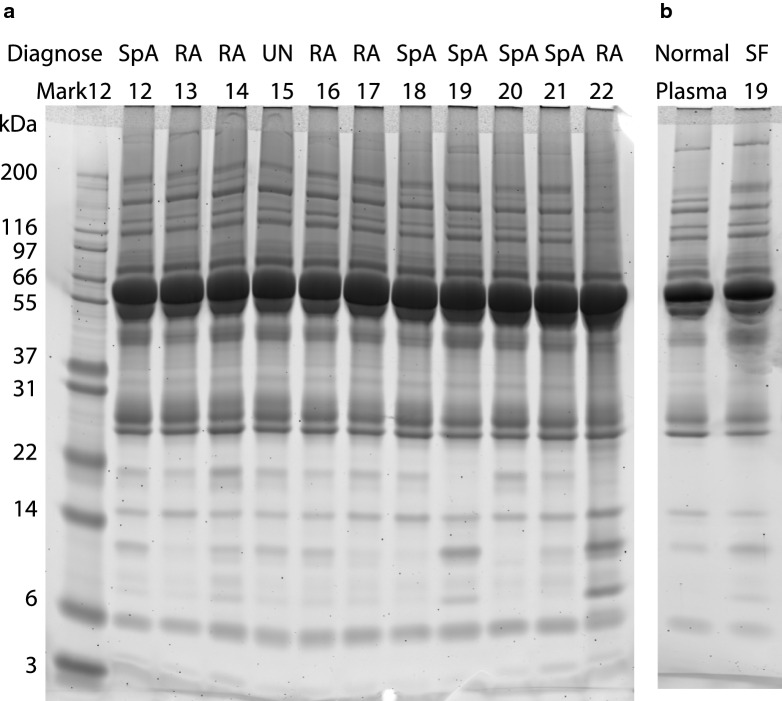

Sodium dodecyl sulphate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis of SF

SF was cleared for cellular debris by centrifugation at 600×g for 15 min at 20 °C, before storage at -80 °C. After thawing, the samples were centrifuged at 20,000×g for 10 min at 4 °C. The protein concentration was measured with the Bicinchonic Acid (BCA) Protein Assay (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA) according the manufactures instruction. Five µg protein in SDS-samples buffer (Expedeon, San Diego, CA) were separated by 12% SDS-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (Expedeon). As molecular weight standard, 2.5 µl Mark12® (Thermo Fisher Scientific) was used. The proteins were stained with Krypton™ Fluorescent Protein Stain (Thermo Fisher Scientific) according the manufactures instruction and scanned on an Amersham Typhoon Biomolecular Imager (GE Healthcare, Chicago, IL).

Sample preparation for proteomics

For sample preparation “filter-aided sample preparation” (FASP) was used [20, 21]. Briefly, 100 µg SF-protein was dissolved in 5% (w/v) sodium deoxycholate (SDC) in 50 mM triethylammonium bicarbonate (TEAB). The samples were heated to 90 °C for 5 min. Molecular weight cut-off Spinfilters 10 kDa (YM10; Millipore, Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) were used for buffer exchange between the different steps. The samples were reduced with 12 mM Tris(2-carboxyethyl) phosphine hydrochloride (TCEP), alkylated with 40 mM iodoacetamide (IAA) and digested with 0.4 μg sequencing grade modified trypsin (Promega, Fitchburg, Wisconsin, USA) resuspended in 0.5% SDC, 50 mM TEAB. After digestion, the peptides were collected, and acidified with 0.1% trifluoroacetic acid (TFA). The peptide product was purified using ethyl acetate extraction and the final product was dried down in a vacuum centrifuge and stored at − 80 °C. Prior to analysis, the samples were resuspended in 2% acetonitrile (ACN) and 0.1% TFA.

Mass spectrometry-based proteomics analysis

The mass spectrometry-based analysis was performed according to Bennike et al. [20] in a randomized patient order. The protein solution was analysed on an automated LC-electrospray ionization (ESI) MS/MS system using an Ultimate 3000 UPLC system with a nanopump module. The system was coupled online to a Thermo-Electron Q Exactive Plus mass spectrometer (Thermo Scientific, Waltham, USA) with an emitter for nanospray ionization. Triplicate runs of each sample (5% of digested material) were loaded onto the C18 reversed phase column (Dionex; Acclaim PepMap100 C18, 5 μm precolumn and 50 cm Acclaim Pepmap RSLC, 75 μm ID main column, Thermo Scientific) and eluted with a linear gradient of 96% solvent A (1% formic acid) and 4% solvent B (acetonitrile)[20] which was increased to 35% solvent B on a 90 min ramp gradient. The MS was operated in data dependent acquisition (DDA) mode, selecting the 12 precursor-ions with the highest intensity for higher energy collisional dissociation (HCD) fragmentation. The raw- and processed data have been made available via ProteomeXchange with identifier PXD010723 [22].

Proteomics data analysis

A label-free analysis of the proteomics data was performed in MaxQuant v1.6.0.1. The fragment scans were searched against a Uniprot database containing all reviewed Homo sapiens proteins.

(Uniprot reference proteome UPID5640; downloaded 08.2017). The following abundant peptide modifications were included in the analysis: carbamidomethylated cysteine residues (fixed), acetylation of N peptides from the N-terminal of proteins (variable), and oxidation of methionine (variable). The build-in MaxQuant target-decoy search strategy was applied and used to adjust the false discovery rate (FDR) of identified peptides and proteins to max 1%. The MaxQuant MaxLFQ feature, which estimates peptide and protein abundances based on normalized summed peptide precursor intensities, was applied. The resulting label free protein abundance (LFQ) data was processed in Perseus v1.6.0.2 [23]. All protein abundances were log2-transformed. Only for the unsupervised principle component analysis (PCA), did we replace (imputed) missing values with values drawn from a normal distribution to circumvent the problem that PCA cannot handle missing values [24, 25]. This was done by using standard parameters in Perseus for label-free proteomics data, to simulate signals from low-abundant proteins (width = 0.3, downshift = 1.8). Technical replicates were combined by the median, and differentially expressed proteins were identified by t-tests, corrected for multiple hypothesis testing using permutation-based false-positive control with standard parameters in Perseus (s0 = 0.1, FDR < 0.05). Protein function was analysed using Gene Ontology (GO) nomenclature from UniProt protein knowledgebase (UniProtKB) (http://www.uniprot.org) annotation and the software tool “Software tool for researching annotations of proteins” (STRAP) [26]. Unsupervised hierarchical clustering with Euclidean distance calculations was performed on z-score normalized data using standard parameters in Perseus (300 clusters, 10 iterations). Pearson’s correlation analyses of the LFQ values were performed as previously described [27]. Finally, for exploratory analyses we performed linear mixed effect models and random forest modelling using R.

C-reactive protein

CRP was measured at the Department of Biochemistry at Aarhus University Hospital as part of routine care using a Cobas 6000 (Chemistry XPT).

Cell-free DNA measurement

SF was thawed and centrifuged at 15,000×g for 15 min, diluted 1:25 in 10 mM Tris, pH 8.0 with 1 mM EDTA (TE-buffer). The Quant-iT™ PicoGreen™ dsDNA Assay Kit (ThermoFisher Scientific) was used according to the manufacture’s instruction using 96 well Microplates, PP, F-Bottom black chimney well design (Sigma Aldrich). Fourfold dilution series of DNA were included on all plates (1 µg/ml, 250 ng/ml, 62 ng/ml, 15.6 ng/ml, 3.9 ng/ml, 970 pg/ml, 243 pg/ml, 0 pg/ml). Samples and standards were prepared and measured in duplicates. Plates were measured on an Enspire Multimode Plate Reader (Perkin Elmer, Waltham, MA) with excitation 480 nm and emission 520 nm.

Results

Patient material

SF was obtained from patients visiting the outpatient clinic at Aarhus University Hospital at the time when therapeutic arthrocentesis was performed. Of the 32 RA patients, five were in treatment with TNF inhibitors (Adalimumab®, Certolizumab® or Etanercept®), four with the IL-6 receptor antagonist Tocilizumab® and three with T-cell activation inhibitor Abatacept®. Nineteen of the RA patients were in methotrexate treatment. Of the 24 SpA patients 6 were in treatment with TNF inhibitors and one with Abatacept®. In the RA group 38% was positive for RF and 42% positive for ACPA. In the group of SpA patients 84% was of the HLA-B27 tissue type.

SDS-PAGE analysis of SF

The protein concentration in the 56 SF-samples varied from 15.7 to 55.4 mg/ml with a mean of 38.1 mg/ml, which is slightly higher than the ~ 25 mg/ml reported in SF from healthy persons. The higher protein-concentration is likely caused by the inflammation [28]. To analyse for major differences in the protein composition, all SF-samples were visualized by 12% SDS-PAGE (Fig. 1a, patient number 12–22). Human albumin bands with a size of 66.5 kDa were seen in all samples with a similar intensity, showing that the adjusted protein load was identical for all samples. Variation was only seen in band patterns below 20 kDa. Comparing the samples, there was no observable correlation between the low molecular weight band patterns and the diagnosis. SF is a filtrate of plasma plus proteins produced locally in the joint. Therefore, we compared a SF sample from a SpA patient to plasma from a healthy participant using SDS-PAGE (Fig. 1b), and only minor differences in low molecular weight bands were seen between normal plasma and SF from SpA patient 19. This indicates that the majority of proteins in an inflamed joint is plasma-derived proteins.

Fig. 1.

12% SDS-PAGE of SF and plasma stained with Krypton™ Fluorescent Protein Stain. a Lane 1: Molecular weight standard. Lanes 2–12: SF from patient 12–22. The diagnosis is marked over the patient numbers, SpA and RA. b Comparison of normal plasma with

Quantitative proteomics analysis of SF proteins in RA and SpA

Because of the high similarity between the overall protein composition of RA and SpA samples, a label-free proteomics analysis was performed to get a deeper proteome coverage and obtain relative quantitative information to reveal the differences in SF of the 56 samples (RA n = 32, SpA n =24). Each SF sample was digested in solution with trypsin, separated by nanoUPLC and peptides were sequenced using tandem MS by HCD fragmentation. All samples were analysed in triplicates, resulting in 168 MS-runs. Cumulated, we identified 335 proteins (false discovery rate (FDR) < 1%). Following stringent filtering to ensure high-quality quantitative data, 266 proteins were quantifiable cumulated in the SF samples (Additional file 1: Table S1).

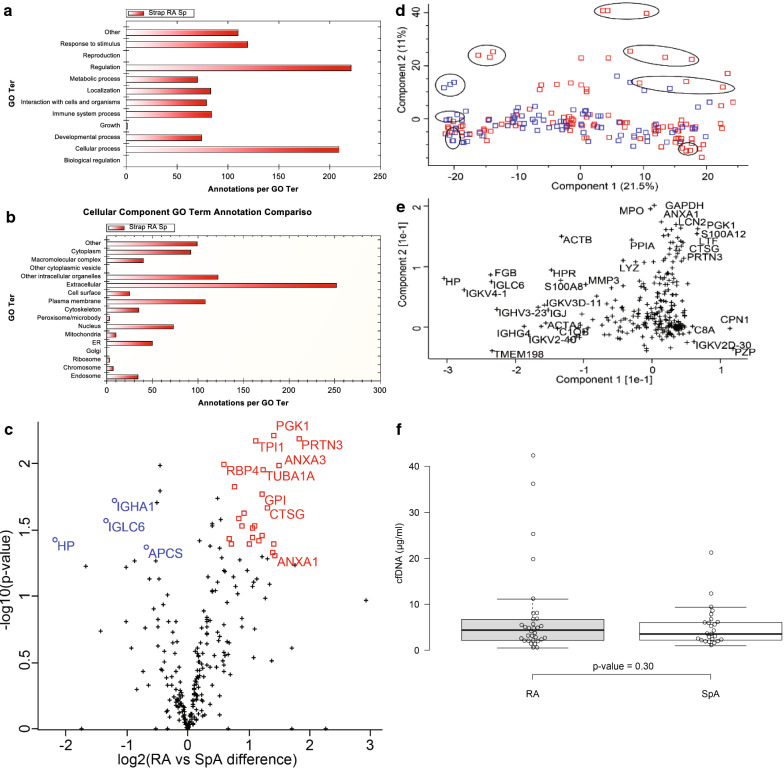

Overall SF proteome segregation by gene ontology characterization

The quantifiable proteins were classified according to their functional Gene ontology (GO) information obtained from UniProtKB and GO annotation and visualized with the STRAP software according to “biological process” and “cellular component” (Fig. 2). As shown in Fig. 2a (biological processes), characterization of the biological process (Fig. 2a) identified 85 proteins associated with the immune system, and in addition the groups “regulation” and “cellular process” were dominant. The GO cellular component (Fig. 2b) showed that 252 proteins were classified as “extracellular” in agreement with SF being an extracellular fluid. In addition, many proteins have the annotation “Other intracellular organelles”. This GO nomenclature covers the secretory pathway group. Furthermore, few proteins are seen in the groups: “nucleus”, “cytoplasm” and “cytoskeleton”, supporting a high degree of cellular infiltration in SF from these patients.

Fig. 2.

Proteomic analysis. Gene ontology for the 266 quantified proteins visualized with the STRAP software; a Biological processes b Cellular component. c, d PCA analysis of identified proteins. d Grouping of technical repeats (encircled) are for the majority located together. RA patients are marked red and SpA patients blue. Principle component 2 mainly separates the RA and SpA patients. d Analysis of proteins that contribute to 1st and 2nd components of PCA. Principal component 1 separates samples based on haptoglobin (HP), Fibrinogen beta chain (FGB) and several immunoglobulins (IG) proteins. Principal component 2 separates samples based on inflammatory proteins as Myeloperoxidase (MPO), S100-A12 protein (S100A12), Lysozyme C (LYZ), Neutrophil gelatinase-associated lipocalin (LCN2) and Cathepsin G (GTSG). E) Comparison of RA and SpA protein abundances. Gene names are given for a subset of proteins passing p-value < 0.05 as determined by t-test. □: more abundant in RA, ○: more abundant SpA, +: not significantly changed. f Student-T test of cfDNA concentrations in SF from RA and SpA patients. No significant difference was observed (p-value < 0.05)

Comparison of RA and SpA proteomes by Principal component analysis (PCA)

The overall similarities between the 168 LC–MS runs were investigated by an unsupervised PCA plot on the complete data set before merging the technical triplicates. The scores plot revealed that the technical repeats mostly cluster together (Fig. 2c, encircled). This demonstrates a smaller technical variance than interpersonal difference between the samples, as expected for a sensitive and robust analysis method. The first principal component (the largest possible variation 21%, X-axis) does not discriminate between RA and SpA patients (Fig 2c), whereas the second component (highest variance to first component 11%, Y-axis) is discriminative for some of the RA patients (Fig 2c).

Proteins that contribute the most to the variation in component one and two were analysed by a factor loading plot (Fig. 2d). Principle component 1 was largely separated based on haptoglobin (HP), Fibrinogen beta chain (FGB) and several immunoglobulin proteins encoded from variable (V) gene segments of both heavy chain and light chain. Principle component 2 became separated on basis of inflammatory proteins, including Myeloperoxidase, S100-A12 protein, Lysozyme C, Cathepsin G and Neutrophil gelatinase-associated lipocalin. (Fig. 2d). This indicates that the PC2 separation is based on the inflammatory joint status of the patients. Accordingly, the four RA patients with the highest PC2-value (pt. 22, 25, 34, and 64) had significantly increased SF IgM (mean increase 6.34, p-value 0.04). In these patients CRP was also increased, although not significantly.

Analysis of SF protein differences between RA and SpA

Comparing all identified proteins of RA to all of SpA using t-tests, none of the proteins passed multiple hypothesis correction (q-value < 0.05). However, applying a less strict cut-off without multiple hypothesis correction (p-value < 0.05, log2 (fold change) > 0.5 or < − 0.5), 25 more abundant proteins in RA compared to SpA were identified, in addition to 4 less abundant proteins (Fig. 2e, Table 1). The majority of the more abundant RA-proteins are present in neutrophil granulocytes and monocytes (Table 1 marked a) or proteins involved in the glycolysis (Table 1 marked b). This is in agreement with the preliminary conclusions from the PCA, and indicates the presence of infiltrating neutrophils in the SF from RA patients, in agreement with previous reports [3]. In addition, the data demonstrates the significantly lower/lack of infiltrating neutrophils in SpA, highlighting a central difference in the pathogenesis of RA and SpA.

Table 1.

Proteins with a significant abundance difference (p-value < 0.05, log2 (fold change) > ± 0.5) between RA and SpA synovial fluid

| RA SpA fold change (%) | p-value | Protein names |

|---|---|---|

| 357 | 0.006 | Myeloblastina |

| 281 | 0.010 | Annexin A3 |

| 270 | 0.050 | Annexin A1 |

| 267 | 0.006 | Phosphoglycerate kinase 1 |

| 267 | 0.041 | Alpha-actinin-1 |

| 263 | 0.047 | Myeloid cell nuclear differentiation antigena |

| 247 | 0.022 | Cathepsin Ga |

| 236 | 0.011 | Tubulin alpha-1A chain |

| 234 | 0.017 | Glucose-6-phosphate isomeraseb |

| 232 | 0.035 | Ras-related C3 botulinum toxin substrate 2 |

| 224 | 0.039 | Heat shock-related 70 kDa protein 2 |

| 217 | 0.007 | Triosephosphate isomeraseb |

| 213 | 0.030 | Moesin |

| 209 | 0.031 | Pyruvate kinaseb |

| 208 | 0.036 | Adenylyl cyclase-associated protein 1a |

| 202 | 0.040 | Glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenaseb |

| 189 | 0.024 | 14-3-3 protein zeta/delta |

| 186 | 0.030 | Beta-2-microglobulin |

| 179 | 0.026 | Profilin-1 |

| 171 | 0.015 | Phosphoglycerate mutase 1b |

| 164 | 0.041 | Plastin-2 |

| 160 | 0.037 | Transgelin-2 |

| 151 | 0.010 | Retinol-binding protein 4 |

| 145 | 0.026 | Complement factor D |

| 144 | 0.044 | Transketolase |

| 62 | 0.043 | Serum amyloid P-component |

| 43 | 0.019 | Ig alpha-1 chain C region |

| 40 | 0.027 | Ig lambda-6 chain C region |

| 22 | 0.038 | Haptoglobin |

aProteins specific for neutrophile grunolocytes and monocytes

bEnzymes involved in glycolysis

Correlation of protein changes to concentration of cell-free DNA in SF

Cell-free DNA (cfDNA) in plasma is an inflammatory marker for RA and has been proposed as a predictive marker for biological disease-modifying anti-rheumatic drugs (DMARD) treatment [29, 30]. cfDNA in the SF was measured by a fluorometric method. The SF cfDNA concentration was found to vary between 0.5 to 42.2 µg/ml. These values are an order of tree magnitude higher than can be observed in plasma from RA patients [29, 30], and it reflects that cfDNA originates from cells present in SF. SF cfDNA could be measured in both patient groups, but no statistically significant difference between the intra articular cfDNA concentrations was observed between the RA and SpA patients (RAmean = 7.3 µg/ml, SpAmean = 5.1 µg/ml, t-test p-value = 0.30) (Fig. 2f). The SF samples were centrifuged to remove cells before freezing and to avoid the release of cellular DNA. However, it cannot be excluded that cell lysis occurred after collection and prior to centrifugation. With this reservation in mind, the SF levels of cfDNA was correlated to the SF protein abundance levels to identify functional proteins, which could elucidate the biological interpretation of the cfDNA measurements. Sixty-eight proteins correlated significantly (p-value < 0.05) with the amount of cfDNA in the SF (Table 2).

Table 2.

Correlation Analysis: Synovial fluid proteins identified by mass spectrometry across all RA and SpA samples correlating significantly (p-value < 0.05) to synovial fluid cfDNA

| UPID | Protein name | Gene name | R | p-value | NETs |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| P62805 | Histone H4 | HIST1H4A | 0.9170 | 1.52E−06 | + |

| P14780 | Matrix metalloproteinase-9 | MMP9 | 0.8141 | 4.02E−06 | + |

| P80188 | Neutrophil gelatinase-associated lipocalin | LCN2 | 0.7925 | 3.88E−08 | + |

| P07900 | Heat shock protein HSP 90-alpha | HSP90AA1 | 0.7314 | 4.40E−06 | |

| P37837 | Transaldolase | TALDO1 | 0.7292 | 7.12E−03 | |

| P02788 | Lactotransferrin | LTF | 0.7158 | 5.62E−10 | + |

| P20160 | Azurocidin | AZU1 | 0.7114 | 4.61E−05 | + |

| Q99880 | Histone H2B type 1-L | HIST1H2BL | 0.7008 | 1.61E−05 | + |

| P12814 | Alpha-actinin-1 | ACTN1 | 0.6964 | 3.86E−05 | + |

| P61626 | Lysozyme C | LYZ | 0.6946 | 1.57E−08 | + |

| P24158 | Myeloblastin | PRTN3 | 0.6803 | 4.89E−05 | + |

| P15153 | Ras-related C3 botulinum toxin substrate 2 | RAC2 | 0.6803 | 1.31E−04 | |

| P52566 | Rho GDP-dissociation inhibitor 2 | ARHGDIB | 0.6694 | 1.25E−03 | |

| P08246 | Neutrophil elastase | ELANE | 0.6660 | 1.35E−03 | + |

| P05164 | Myeloperoxidase | MPO | 0.6584 | 4.89E−07 | + |

| P52209 | 6-phosphogluconate dehydrogenase, decarboxylating | PGD | 0.6529 | 4.04E−04 | |

| P0DMV9 | Heat shock 70 kDa protein 1B | HSPA1B | 0.6524 | 1.35E−03 | |

| P63261 | Actin, cytoplasmic 2 | ACTG1 | 0.6419 | 1.28E−07 | |

| P00558 | Phosphoglycerate kinase 1 | PGK1 | 0.6270 | 3.28E−05 | |

| Q99878 | Histone H2A type 1-J | HIST1H2AJ | 0.6265 | 1.05E−03 | + |

| P04406 | Glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase | GAPDH | 0.6096 | 3.33E−06 | |

| P06744 | Glucose-6-phosphate isomerase | GPI | 0.6007 | 3.99E−03 | |

| P12429 | Annexin A3 | ANXA3 | 0.5955 | 2.14E−03 | |

| P08311 | Cathepsin G | CTSG | 0.5944 | 1.66E−04 | + |

| P06733 | Alpha-enolase | ENO1 | 0.5942 | 1.38E−06 | + |

| P14618 | Pyruvate kinase PKM | PKM | 0.5898 | 2.15E−06 | |

| P06702 | Protein S100-A9 | S100A9 | 0.5857 | 2.12E−06 | + |

| P07737 | Profilin-1 | PFN1 | 0.5778 | 5.90E−06 | |

| P08670 | Vimentin | VIM | 0.5745 | 1.58E−05 | |

| P60174 | Triosephosphate isomerase | TPI1 | 0.5720 | 4.09E−04 | |

| P13796 | Plastin-2 | LCP1 | 0.5704 | 5.45E−06 | + |

| Q01518 | Adenylyl cyclase-associated protein 1 | CAP1 | 0.5698 | 1.53E−04 | |

| P09211 | Glutathione S-transferase P | GSTP1 | 0.5578 | 1.67E−03 | |

| P00338 | l-Lactate dehydrogenase A chain | LDHA | 0.5531 | 4.14E−03 | |

| P04083 | Annexin A1 | ANXA1 | 0.5486 | 1.40E−04 | |

| P01033 | Metalloproteinase inhibitor 1 | TIMP1 | 0.5463 | 3.21E−04 | |

| P26038 | Moesin | MSN | 0.5314 | 4.19E−04 | |

| P62937 | Peptidyl-prolyl cis-trans isomerase A | PPIA | 0.5142 | 1.85E−04 | |

| P30740 | Leukocyte elastase inhibitor | SERPINB1 | 0.5103 | 4.34E−02 | |

| P18669 | Phosphoglycerate mutase 1 | PGAM1 | 0.5080 | 3.13E−04 | |

| Q71U36 | Tubulin alpha-1A chain | TUBA1A | 0.4917 | 1.07E−02 | |

| P22894 | Neutrophil collagenase | MMP8 | 0.4728 | 4.74E−03 | |

| P80511 | Protein S100-A12 | S100A12 | 0.4689 | 5.16E−03 | |

| P63104 | 14-3-3 protein zeta/delta | YWHAZ | 0.4675 | 2.70E−03 | |

| P29401 | Transketolase | TKT | 0.4575 | 1.58E−03 | |

| P09960 | Leukotriene A-4 hydrolase | LTA4H | 0.4572 | 3.91E−03 | |

| P23528 | Cofilin-1 | CFL1 | 0.4462 | 1.89E−03 | |

| P68133 | Actin, alpha skeletal muscle | ACTA1 | 0.4370 | 2.01E−02 | |

| P08133 | Annexin A6 | ANXA6 | 0.4199 | 7.79E−03 | |

| P02679 | Fibrinogen gamma chain | FGG | 0.4183 | 1.34E−03 | |

| P36222 | Chitinase-3-like protein 1 | CHI3L1 | 0.4106 | 7.67E−03 | |

| P12111 | Collagen alpha-3(VI) chain | COL6A3 | 0.3898 | 3.26E−03 | |

| P07195 | l-Lactate dehydrogenase B chain | LDHB | 0.3686 | 3.19E−02 | |

| P04075 | Fructose-bisphosphate aldolase A | ALDOA | 0.3684 | 2.94E−02 | |

| P02741 | C-reactive protein | CRP | 0.3470 | 8.78E−03 | |

| P04003 | C4b-binding protein alpha chain | C4BPA | 0.3119 | 2.17E−02 | |

| P02763 | Alpha-1-acid glycoprotein 1 | ORM1 | 0.3061 | 2.18E−02 | |

| P02750 | Leucine-rich alpha-2-glycoprotein | LRG1 | 0.3046 | 2.24E−02 | |

| P04040 | Catalase | CAT | 0.2955 | 2.70E−02 | |

| P07225 | Vitamin K-dependent protein S | PROS1 | 0.2941 | 2.78E−02 | |

| P08603 | Complement factor H | CFH | 0.2883 | 3.12E−02 | |

| P0DJI8 | Serum amyloid A-1 protein | SAA1 | 0.2866 | 3.56E−02 | |

| P60709 | Actin, cytoplasmic 1 | ACTB | 0.2793 | 4.09E−02 | |

| P49747 | Cartilage oligomeric matrix protein | COMP | − 0.2706 | 4.37E−02 | |

| P02751 | Fibronectin | FN1 | − 0.2939 | 2.79E−02 | |

| Q13790 | Apolipoprotein F | APOF | − 0.4627 | 3.02E−03 | |

| Q96RL7 | Vacuolar protein sorting-associated protein 13A | VPS13A | − 0.5619 | 1.23E−02 | |

| Q66K66 | Transmembrane protein 198 | TMEM198 | − 0.5646 | 2.27E−02 |

Correlation of proteins found changed/increased by proteomic in SF to regulatory pathways

To identify underlying biological themes and pathways of the correlating proteins, a GO enrichment analysis using the Reactome pathway database, calculated with all identified SF-proteins as background was performed [31]. The list of synovial fluid proteins with a positive correlation with cfDNA, was significantly enriched (FDR < 0.05) in five biological pathways (Table 3). Thirty-nine of the proteins were tagged as “Immune System” (R-HSA-168256), 31 as “Innate Immune System” (R-HSA-168249) and 26 of the 68 proteins (38%) were categorized as “Neutrophil degranulation” (R-HAS-6798695). The Glycolysis (R-HAS-70171) pathway was also significant enriched, in agreement with the anaerobic metabolism of neutrophils and liberation of the cytoplasmic enzymes upon cell disruption [32].

Table 3.

Statistical significant enriched Reactome biological pathways for synovial fluid proteins associated with the synovial fluid cfDNA concentration

| Reactome ID | Name | #Proteins | FDR |

|---|---|---|---|

| R-HSA-70171 | Glycolysis | 8 | 1.15e−02 |

| R-HSA-6798695 | Neutrophil degranulation | 26 | 1.15e−02 |

| R-HSA-71387 | Metabolism of carbohydrates | 11 | 3.36e−02 |

| R-HSA-70263 | Gluconeogenesis | 7 | 4.85e−02 |

| R-HSA-168256 | Immune system | 39 | 4.85e−02 |

NETs are formed in the process of NETosis where neutrophils ejects DNA with histones, in addition to cytoplasmic and secretory granules to form a web-like structure [33, 34]. Of the 11 most correlated proteins to cfDNA, 9 were known NETs proteins (Table 2, labelled “+”). Therefore, the presence of cfDNA correlates with proteins predominantly found in neutrophil granulocytes in both RA and SpA SF, and in vivo liberation of DNA prior to sample collection is therefore likely and not a sampling artefact.

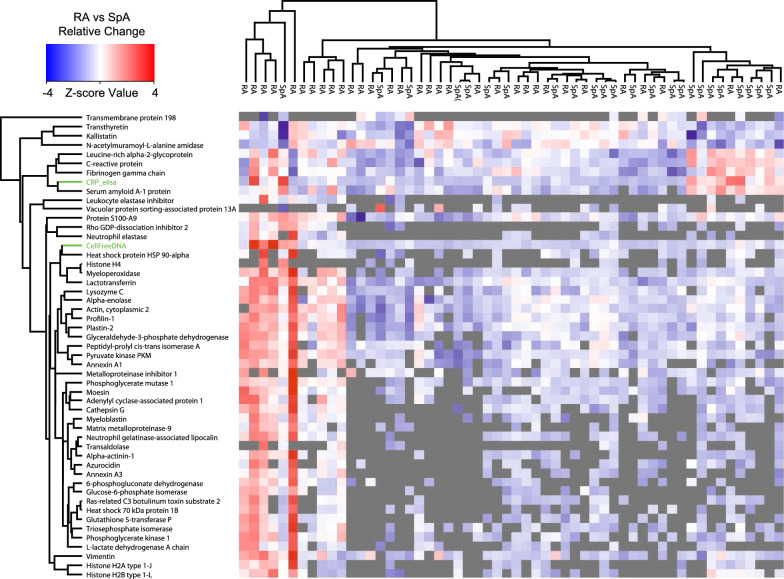

Twenty-nine proteins known to be associated with NETs formation have been identified by MS [34, 35]. Of these 29 proteins, 21 were identified in the SF. To visualize the cfDNA correlation to NETs proteins a hierarchical clustering with the 21 proteins and SF cfDNA was performed (Fig. 3). The analysis showed that high concentration of cfDNA was correlated to presence of NETs proteins. NETs formation is enhanced by Resistin, that can be produced by synoviocytes in joints of RA patients [36, 37]. The receptor for Resistin is the Adenylyl cyclase-associated protein 1 (CAP1) [36]. Accordingly, CAP1 was found to be more abundant in the RA group (Table 1) and correlated significantly and positively with cfDNA (R = 0.5698, p-value = 1.53*10−4) (Table 2). The findings indicate that NETs formation is more abundant in RA-joints compared to SpA, again pointing to the involvement of NETs in RA which recently has been demonstrated to sustain inflammation in other inflammatory diseases.

Fig. 3.

Hierarchical clustering of cfDNA and plasm CRP correlated proteins. For the clustering all proteins correlating positive R > 0.5 or negativ R < − 0.5 to plasma CRP or cfDNA were selected (Tables 2, 4). Values of plasma CRP (log2) and cfDNA (log2) were included in the clustering (labelled green). The diagnosis is marked over the clustering. NGAL is the abbreviation for Neutrophil gelatinase-associated lipocalin

Correlation of plasma CRP to SF proteins

A common inflammatory marker used in SpA and RA is plasma-CRP, which has a half-life of 19 h [38]. Therefore, in addition to cfDNA, the measured plasma-CRP was correlated to protein abundances in SF, with the aim to identify inflammation-associated proteins. Forty-one proteins were found to correlate significantly with plasma-CRP (p-value < 0.05), 22 of which correlated positively and 19 negatively. Reassuringly, SF-CRP correlated positively with plasma-CRP (R = 0.7148, p-value = 6.12*10−10), verifying the validity of the MS-based proteomics data (Table 4). The other proteins correlating positively to plasma-CRP were also acute phase reactants, e.g. alpha-1-antichymotrypsin, serum amyloid A-1 protein, and, further, other protein groups influenced by plasma-CRP such as complement system proteins (Table 4). Proteins correlating negatively included known “Negative” acute-phase proteins such as albumin, transferrin, transthyretin and retinol-binding protein 4 [39, 40].

Table 4.

SF proteins identified by proteomics with statistically significant correlation (p-value < 0.05) to plasma CRP

| UPID | Protein name | Gene name | R | p value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| P0DJI8 | Serum amyloid A-1 protein* | SAA1 | 0.7254 | 5.47E−10 |

| P02741 | C-reactive protein* | CRP | 0.7148 | 6.12E−10 |

| P02750 | Leucine-rich alpha-2-glycoprotein* | LRG1 | 0.5769 | 3.26E−06 |

| P02679 | Fibrinogen gamma chain* | FGG | 0.5399 | 1.75E−05 |

| Q7Z4H8 | KDEL motif-containing protein 2 | KDELC2 | 0.4856 | 4.82E−02 |

| P18428 | Lipopolysaccharide-binding protein | LBP | 0.4765 | 2.05E−04 |

| P07225 | Vitamin K-dependent protein S* | PROS1 | 0.4328 | 8.64E−04 |

| Q06033 | Inter-alpha-trypsin inhibitor heavy chain H3 | ITIH3 | 0.4321 | 9.85E−04 |

| P00751 | Complement factor B | CFB | 0.4182 | 1.34E−03 |

| P02671 | Fibrinogen alpha chain | FGA | 0.3954 | 2.56E−03 |

| P06702 | Protein S100-A9* | S100A9 | 0.3913 | 2.86E−03 |

| P02748 | Complement component C9 | C9 | 0.3893 | 3.02E−03 |

| P01011 | Alpha-1-antichymotrypsin | SERPINA3 | 0.3868 | 3.23E−03 |

| P01009 | Alpha-1-antitrypsin | SERPINA1 | 0.3865 | 3.26E−03 |

| P68133 | Actin, alpha skeletal muscle* | ACTA1 | 0.3791 | 4.66E−02 |

| P02743 | Serum amyloid P-component | APCS | 0.3657 | 6.03E−03 |

| P08603 | Complement factor H* | CFH | 0.3298 | 1.30E−02 |

| P36222 | Chitinase-3-like protein 1* | CHI3L1 | 0.3170 | 4.34E−02 |

| P02788 | Lactotransferrin* | LTF | 0.3042 | 2.26E−02 |

| P05156 | Complement factor I | CFI | 0.2866 | 3.23E−02 |

| P04003 | C4b-binding protein alpha chain* | C4BPA | 0.2727 | 4.60E−02 |

| Q14624 | Inter-alpha-trypsin inhibitor heavy chain H4 | ITIH4 | 0.2683 | 4.56E−02 |

| P27169 | Serum paraoxonase/arylesterase 1 | PON1 | − 0.2719 | 4.27E−02 |

| P02753 | Retinol-binding protein 4 | RBP4 | − 0.2900 | 3.02E−02 |

| P05452 | Tetranectin | CLEC3B | − 0.2923 | 2.88E−02 |

| P02656 | Apolipoprotein C-III | APOC3 | − 0.2934 | 2.82E−02 |

| Q92954 | Proteoglycan 4 | PRG4 | − 0.2970 | 2.62E−02 |

| P01871 | Ig mu chain C region | IGHM | − 0.2997 | 2.48E−02 |

| P19823 | Inter-alpha-trypsin inhibitor heavy chain H2 | ITIH2 | − 0.3006 | 2.44E−02 |

| P19827 | Inter-alpha-trypsin inhibitor heavy chain H1 | ITIH1 | − 0.3293 | 1.32E−02 |

| P02751 | Fibronectin* | FN1 | − 0.3301 | 1.30E−02 |

| P22352 | Glutathione peroxidase 3 | GPX3 | − 0.3325 | 2.74E−02 |

| P02647 | Apolipoprotein A-I | APOA1 | − 0.3343 | 1.18E−02 |

| P43652 | Afamin | AFM | − 0.3650 | 5.67E−03 |

| P02787 | Transferrin | TF | − 0.3669 | 5.41E−03 |

| P05154 | Plasma serine protease inhibitor | SERPINA5 | − 0.3706 | 9.51E−03 |

| P06396 | Gelsolin | GSN | − 0.3730 | 4.63E−03 |

| P02768 | Albumin | ALB | − 0.4892 | 1.30E−04 |

| Q96PD5 | N-Acetylmuramoyl-L-alanine amidase | PGLYRP2 | − 0.5021 | 8.06E−05 |

| P02766 | Transthyretin | TTR | − 0.5277 | 2.93E−05 |

| P29622 | Kallistatin | SERPINA4 | − 0.5492 | 1.17E−05 |

Proteins marked with * are also positive correlated to SF cfDNA

Correlation of SF proteins to plasma-CRP and SF cfDNA

The two inflammatory markers, plasma-CRP and SF cfDNA correlated, but not strongly (R = 0.4765, p-value = 2.01*10−4). However, the proteins correlating positively or negatively to each of the two markers were considerably different, and of the 109 statistically significantly correlating proteins, only 12 (11%) were common (Tables 2, 4). Hierarchical clustering with positive correlated proteins to both cfDNA (Fig. 3) and positive as well as negative correlated proteins to plasma CRP, showed a distinct clustering (Fig. 3) with a group of 11, predominantly RA patients with NETs markers (Fig. 3, left). Three of these patients were in biological treatment, showing that the treatment was not responsible for the generation of cfDNA. A group of 10, predominantly SpA patients, correlated with acute phase reactants without NETs proteins (Fig. 3, right), demonstrating the involvement of NETs in RA and the likely subgrouping of the SpA patients. On average a stronger correlating with cfDNA to granulocyte proteins (mean absolute difference 0.13, p-value 1.15*10−6) were seen than to plasma CRP.

Discussion

The findings presented in the present study is, to our knowledge, the first unbiased proteomic approach of examining and comparing RA and SpA SF protein composition. The findings were further correlated with plasma CRP levels and SF cfDNA for discriminating factors. Among the RA patients, proteins from neutrophils were more dominant in SF. Haptoglobin was the only protein found reduced in SF from RA compared with SpA patients, in accordance with higher levels of the scavenging receptor for haptoglobin–haemoglobin CD163 in RA patients [41]. Proteins from neutrophils and glycolytic enzymes correlated strongly to cfDNA in SF predominantly from RA patients. CRP and other acute phase reactants were seen in both RA and SpA patients, but high amounts of acute phase reactants were also detected in SpA patients without neutrophil granulocyte markers.

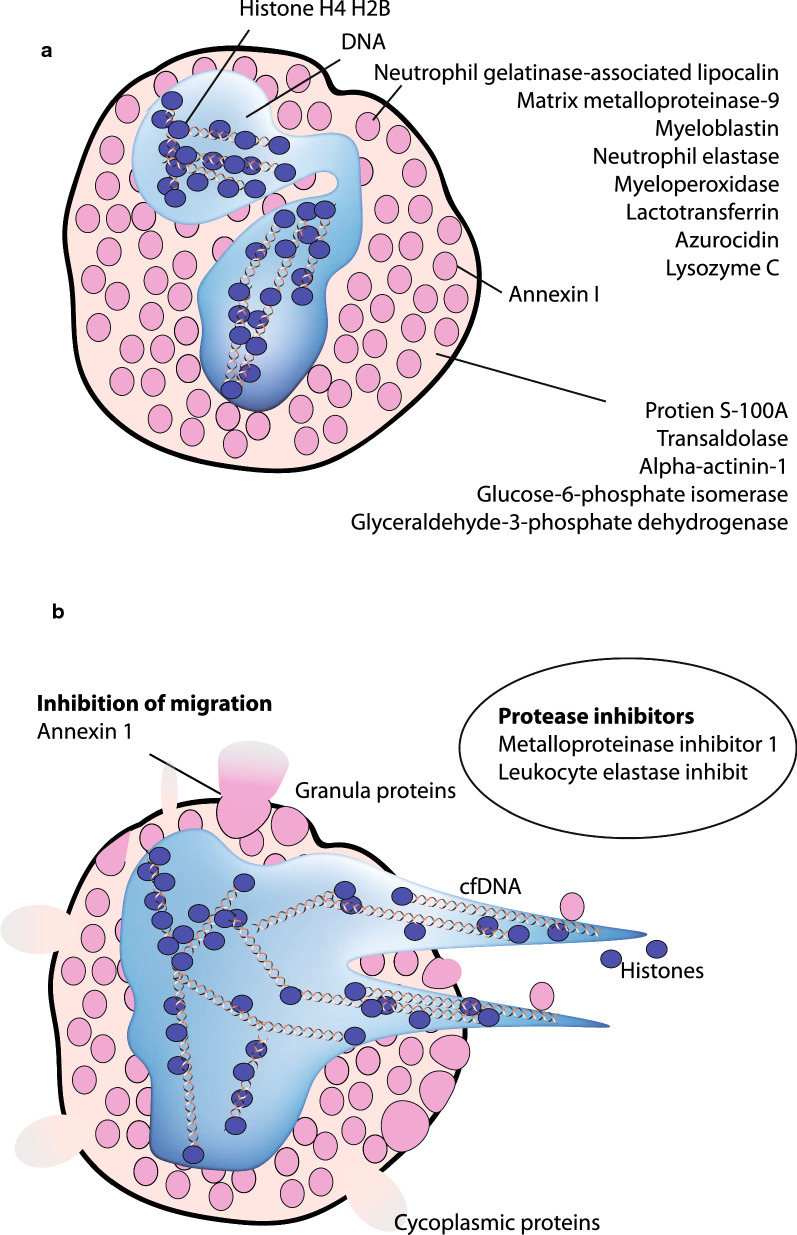

NETs is formed by neutrophils undergoing NETosis, where DNA is expelled from the cells within the tissue lining and in biofluids to form web-like structures together with histones, S100-proteins, and proteins stored in secretory granules (Fig. 4) [34]. NETs markers, as circulating cfDNA, can be used to monitor treatment efficiency of biological DMARD in RA patients [29].

Fig. 4.

Localization of neutrophil proteins that correlate to cfDNA detected in SF. a Schematic drawing of a neutrophil and localisation of proteins correlating to cfDNA. Nucleus (blue) shows DNA and chromatin. Cytoplasmic granules are shown in pink. Annexin 1 is present in the granular membranes but translocated to the cytoplasmic membrane upon degranulation/NETs formation. Cytoplasm (light pink). b During NETosis proteins from all compartments can be released. In inflamed RA joint—both granular, cytoplasmic, nuclear proteins, Annexin 1 and cfDNA were detected in SF. Annexin 1 is an inhibitor of migration of neutrophil to inflammation. Metalloproteinase inhibitor 1 and Leukocyte elastase inhibitor were correlated to cfDNA. The origin of these inhibitors is unknown

Correlation of SF cfDNA to known NETs proteins in SF was found, indicating that the origin of cfDNA was from neutrophils and thereby that NETosis likely had occurred in the joints in vivo. Due to the presence of both the cytoplasmic S100-proteins and the nuclear histone proteins, degranulation of neutrophils without NETosis is unlikely. The DNA-binding protein, Histone H4, is the most correlated protein with cfDNA. Furthermore, MMP9, NGAL (Neutrophil gelatinase-associated lipocalin) and other NETs proteins were also strongly correlated to the presence of cfDNA in the samples (Table 2), indicating that the cfDNA originated from NETosis process. Cytoplasmic proteins as Glucose-6-phosphate isomerase and Glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase correlated also to cfDNA indicating cell rupture (Fig. 4).

Neutrophils contain many proteases with tissue destructive effects. In the SF with high cfDNA, MMP9, MMP8, neutrophil elastase, Myeloblastin and Cathepsin G, that can contribute to destruction, were found (Table 2). MMP9 forms a high molecular weight complex with NGAL, that protects MMP9 from degradation and thereby prolongs its proteolytic activity and tissue destruction [42]. NGAL is upregulated in human neutrophils by granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating (GM-CSF), and in SF of RA compared to OA patients, higher concentrations of NGAL was measured [43]. This is in agreement with reports of higher plasma MMP9 in RA patients compared with OA, and that a higher enzymatic activity was found in SF of RA patients [44, 45]. Furthermore, neutrophils from RA patients compared to healthy controls have a tendency to undergo NETosis easier when treated with PMA [18]. MMP9 could also be produced by synoviocytes in SF from RA patients, but its high correlation to cfDNA shows that the MMP9 most likely originated from neutrophils [46].

Metalloproteinase inhibitor 1 and Leukocyte elastase inhibitor both correlated to cfDNA, but the cell type producing these inhibitors are unclear (Fig. 4). Metalloproteinase inhibitor 1 can form a complex with MMP9 and NGAL. Therefore, the in vivo MMP9 activity is difficult to determine. Ahrens et al. [45] have shown active MMP9 gelatinase activity in SF from RA patients by use of gel zymography, and thus, MMP9 was separated from Metalloproteinase inhibitor 1. Annexin 1, released by neutrophils, is an inhibitor of migration of neutrophils from the blood to the inflamed site, and even though Annexin 1 was present in the SF with cfDNA, it was unable to prevent disease progression (Fig 4).

Katano et al. [43] proposed GM-CSF as a target for treatment of RA and this is now supported by human trials. Patients with high SF cfDNA and NGAL could therefore be a distinct clinical endotype that may benefit from such a treatment [47]. Sato et al. [37] proposed that Resistin produced by synovial tissue could be important for the pathogenesis of RA. The receptor for Resistin, CAP1, was present in SF and correlated to cfDNA. CAP1 is a cytoplasmic protein, but is translocated to the cell membrane when Resistin is present [48]. Resistin enhances NETosis [36], but whether CAP1 in SF can function as a receptor antagonist in its free form is presently unknown.

Plasma CRP is a central marker used in combination with 28-joint Disease Activity Score (DAS28CRP) and Ankylosing Spondylitis Disease Activity Score (ASDAS) to determine disease progression and treatment success, that correlates to disease progression [49]. When plasma CRP was correlated to SF proteomic data, other known positively and negatively regulated acute phase reactants were found (Tables 3 and 4, Fig. 3). Proteins correlated to plasma CRP and cfDNA, respectively, had only 12% proteins in common. Leucine-rich alpha-2-glycoprotein (LRG1) is correlated to both CRP and cfDNA. It is an acute phase protein induced primarily by IL-6 in the liver [50, 51], but is also a neutrophil secondary granule protein released together with lactoferrin, and thus its correlation to both CRP and cfDNA is explainable [52]. LRG1 inhibits the anti-proliferative effect of transforming growth factor ß1 (TGFß1) on myeloid cells [51]. TGFß1 regulates the anti-inflammatory process in the synovial membrane in RA patients, and is important for the self-regulation that can result in remission periods [53]. In RA patients treated with anti-interleukin-6 receptor antibody (RoActemra) LRG1 was a better marker for remission than CRP, matrix metalloproteinase 3 level and erythrocyte sedimentation rate [54]. As shown in the present study, this can be due to LRG1 being a maker for both acute phase reactants and for neutrophil degranulation/NETosis. As shown in Fig. 3, a group of manly SpA patients had high CRP and acute phase reactants without granulocyte markers, confirming the central role of neutrophil granulocytes in the pathogenesis of RA.

The differences between RA and SpA identified here are in line with results from randomized clinical trials with already approved drugs. Thus, T-cell targeted therapies such as inhibitors of IL-17 has shown efficacy in SpA but not in RA. In contrast, therapies targeting myeloid derived cytokines such as inhibitors of IL-1 and IL-6 are effective in RA but not in SpA [55]. Our findings also support that RA is a very heterogenous disease as proposed by others [56]. Thus, a subgroup of RA patients with high neutrophil activation was found. High degree of neutrophil priming and NETosis is also present in other diseases such as systemic lupus erythematosus and granulomatosis with polyangiitis [33, 57]. Some of the drugs used for treatment of these diseases such as the C5a receptor inhibitor Avacopan® could, therefore, also be effective in RA patients with high neutrophil activation. In this way, the study could help guide future drug development to treat immune mediated inflammatory arthritis.

Conclusions

The proteomics of SF from SpA and RA patients showed a marked difference in the amounts of proteins from the innate immune system, primarily originating from neutrophil granulocytes. The presence of these proteins was more pronounced in the RA patient group. These proteins were also correlated to SF cfDNA indicating NETosis. Neutrophils produce IL-6 that induces acute phase reactants, but surprisingly, little correlation between NETs proteins/cfDNA and acute phase reactants/CRP was seen, indicating that two different inflammatory mechanisms are used for increase in CRP and cfDNA. This is in agreement with the recent finding that mature neutrophils are unresponsive to IL-6 due to the absence of gp130 in the IL-6 receptor complex [58]. Some of the patients with high cfDNA were in treatment with anti-interleukin-6 receptor (RoActemra®) or TNF-α antagonists. This may have influenced the amounts of acute phase reactants. However, in a patient material as presented in this study, SF cfDNA is an indicator of intraarticular NETosis. Therefore, SF cfDNA measurement may be used as an indicator of severe arthritis, and our findings demonstrate the involvement of NETs in RA but less in SpA pathogenesis.

Supplementary information

Additional file 1. Combined list of identified proteins in all samples.

Acknowledgment

We thank laboratory assistant Ditte Bech Laursen for technical assistance with the project.

Abbreviations

- ACPA

anti-cyclic citrullinated protein antibodies

- cfDNA

cell-free DNA

- CRP

C-reactive protein

- ESI

LC-electrospray ionization

- FDR

false discovery rate

- HCD

higher energy collisional dissociation

- LFQ

label free quantification

- MHC

major histocompatibility complex

- OA

osteoarthrosis

- PAD

peptidyl arginine deiminases

- PCA

principle component analysis

- RA

Rheumatoid arthritis

- MMP

Matrix metalloproteinases

- MS/MS

tandem mass spectrometry

- NETs

neutrophil extracellular traps

- RF

rheumatoid factor

- SDC

sodium deoxycholate

- SF

synovial fluids

- SpA

spondyloarthritis

- UniProtKB

UniProt protein knowledgebase

- UPLC

ultra-performance liquid chromatography

- TEAB

triethylammonium bicarbonate

Authors’ contributions

TWK and BWD: ethics approval and collection of patient data and samples. SB: SDS-PAGE and preparation of samples for MS. AS, KK and TBGP: performing the LC-MS/MS. AS, TBB, SB, KK and TBGP: data analysis. SB, TBB, AS, GC, and ML drafted the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

This study was supported by Aase and Ejner Danielsens Foundation (Grant 10-001785), Danish National Mass Spectrometry Platform for Functional Proteomics (PRO-MS), Danish Rheumatism Association (Grant R116-Rp4652), The Obel Family Foundation (Grant 25508), The Beckett Foundation, The Hertha Christensen Foundation, The Lundbeck Foundation (R181-2014-3372), and The Carlsberg Foundation (CF14-0561).

Availability of data and materials

The raw- and processed data have been made available via ProteomeXchange with identifier PXD010723

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The clinical samples were collected under the project “INflamation in ARThritis (INART), approved by The Central Denmark Region Committees on Health Research Ethics (1-10-72-291-12). All patients were > 18 years of age, fulfilling the ACR/EULAR criteria for RA and ASAS criteria for SpA, respectively.

Consent for publication

We agree for publication upon acceptance and we agree that all copyright ownership for the article is transferred to Clinical Proteomics. The material submitted is new, original and has not been submitted to another journal for concurrent consideration.

Competing interests

The authors declared that they have no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Svend Birkelund, Email: sbirkelund@hst.aau.dk.

Tue Bjerg Bennike, Email: tbe@hst.aau.dk.

Kenneth Kastaniegaard, Email: kkas@biogenity.com.

Mads Lausen, Email: mln@hst.aau.dk.

Thomas Bouet Guldbæk Poulsen, Email: tbgp@hst.aau.dk.

Tue Wenzel Kragstrup, Email: tuekra@rm.dk.

Bent Winding Deleuran, Email: bd@biomed.au.dk.

Gunna Christiansen, Email: gunnac@hst.aau.dk.

Allan Stensballe, Email: as@hst.aau.dk.

Supplementary information

Supplementary information accompanies this paper at 10.1186/s12014-020-09292-9.

References

- 1.Linos A, Worthington JW, O’Fallon WM, Kurland LT. The epidemiology of rheumatoid arthritis in Rochester, Minnesota: a study of incidence, prevalence, and mortality. Am J Epidemiol. 1980;111:87–98. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a112878. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wang R, Ward MM. Epidemiology of axial spondyloarthritis: an update. Curr Opin Rheumatol. 2018;30:137–143. doi: 10.1097/BOR.0000000000000475. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ottonello L, Cutolo M, Frumento G, Arduino N, Bertolotto M, Mancini M, et al. Synovial fluid from patients with rheumatoid arthritis inhibits neutrophil apoptosis: role of adenosine and proinflammatory cytokines. Rheumatol Narnia. 2002;41:1249–1260. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/41.11.1249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Will R, Edmunds L, Elswood J, Calin A. Is there sexual inequality in ankylosing spondylitis? A study of 498 women and 1202 men. J Rheumatol. 1990;17:1649–1652. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Allen A, Carville S, McKenna F. Diagnosis and management of rheumatoid arthritis in adults: summary of updated NICE guidance. BMJ. 2018;362:k3015. doi: 10.1136/bmj.k3015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sieper J, Rudwaleit M, Baraliakos X, Brandt J, Braun J, Burgos-Vargas R, et al. The Assessment of SpondyloArthritis international Society (ASAS) handbook: A guide to assess spondyloarthritis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2009;6:8. doi: 10.1136/ard.2008.104018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Edelman GM, Kunkel HG, Franklin EC. Interaction of the rheumatoid factor with antigen-antibody complexes and aggregated gamma globulin. J Exp Med. 1958;108:105–120. doi: 10.1084/jem.108.1.105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bizzaro N, Mazzanti G, Tonutti E, Villalta D, Tozzoli R. Diagnostic accuracy of the anti-citrulline antibody assay for rheumatoid arthritis. Clin Chem. 2001;47:1089–1093. doi: 10.1093/clinchem/47.6.1089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Suzuki A, Yamada R, Chang X, Tokuhiro S, Sawada T, Suzuki M, et al. Functional haplotypes of PADI4, encoding citrullinating enzyme peptidylarginine deiminase 4, are associated with rheumatoid arthritis. Nat Genet. 2003;34:395–402. doi: 10.1038/ng1206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.van de Stadt LA, van der Horst AR, de Koning MHMT, Bos WH, Wolbink GJ, van de Stadt RJ, et al. The extent of the anti-citrullinated protein antibody repertoire is associated with arthritis development in patients with seropositive arthralgia. Ann Rheum Dis. 2011;70:128–133. doi: 10.1136/ard.2010.132662. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Harper BE, Reveille JD. Spondyloarthritis: clinical suspicion, diagnosis, and sports. 2009. p. 29–34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 12.Swart A, Burlingame RW, Gürtler I, Mahler M. Third generation anti-citrullinated peptide antibody assay is a sensitive marker in rheumatoid factor negative rheumatoid arthritis. Clin Chim Acta. 2012;414:266–272. doi: 10.1016/j.cca.2012.09.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Barczyńska TA, Węgierska M, Żuchowski P, Dura M, Zalewska J, Waszczak M, et al. Coexistence of rheumatoid arthritis and ankylosing spondylitis. Reumatologia. 2015;53:279–285. doi: 10.5114/reum.2015.55832. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Noh R, Park SG, Ju JH, Chi SW, Kim S, Lee CK, et al. Comparative proteomic analyses of synovial fluids and serums from rheumatoid arthritis patients. J Microbiol Biotechnol. 2014;24:119–126. doi: 10.4014/jmb.1307.07046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mateos J, Lourido L, Fernández-Puente P, Calamia V, Fernández-López C, Oreiro N, et al. Differential protein profiling of synovial fluid from rheumatoid arthritis and osteoarthritis patients using LC-MALDI TOF/TOF. J Proteomics. 2012;75:2869–2878. doi: 10.1016/j.jprot.2011.12.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Balakrishnan L, Bhattacharjee M, Ahmad S, Nirujogi R, Renuse S, Subbannayya Y, et al. Differential proteomic analysis of synovial fluid from rheumatoid arthritis and osteoarthritis patients. Clin Proteomics. 2014;11:1. doi: 10.1186/1559-0275-11-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mahendran SM, Keystone EC, Krawetz RJ, Liang K, Diamandis EP, Chandran V. Elucidating the endogenous synovial fluid proteome and peptidome of inflammatory arthritis using label-free mass spectrometry. Clin Proteomics BioMed Central. 2019;16:1–13. doi: 10.1186/s12014-019-9243-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sur Chowdhury C, Giaglis S, Walker UA, Buser A, Hahn S, Hasler P. Enhanced neutrophil extracellular trap generation in rheumatoid arthritis: analysis of underlying signal transduction pathways and potential diagnostic utility. Arthritis Res. Ther. 2014;16:R122. doi: 10.1186/ar4579. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dejaco C, Singh YP, Perel P, Hutchings A, Camellino D, Mackie S, et al. 2015 recommendations for the management of polymyalgia rheumatica: a European League Against Rheumatism/American College of Rheumatology collaborative initiative. Ann Rheum Dis. 2015;74:1799–1807. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2015-207492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bennike TB, Carlsen TG, Ellingsen T, Bonderup OK, Glerup H, Bøgsted M, et al. Neutrophil extracellular traps in ulcerative colitis. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2015;21:2052–2067. doi: 10.1097/MIB.0000000000000460. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.León IR, Schwämmle V, Jensen ON, Sprenger RR. Quantitative assessment of in-solution digestion efficiency identifies optimal protocols for unbiased protein analysis. Mol Cell Proteomics. 2013;12:2992–3005. doi: 10.1074/mcp.M112.025585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Vizcaíno J, Deutsch EEW, Wang R, Vizcaino JA, Deutsch EEW, Wang R, et al. ProteomeXchange provides globally coordinated proteomics data submission and dissemination. Nat Biotechnol. 2014;32:223–226. doi: 10.1038/nbt.2839\n. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cox J, Hein MY, Luber CA, Paron I, Nagaraj N, Mann M. Accurate proteome-wide label-free quantification by delayed normalization and maximal peptide ratio extraction, termed MaxLFQ. Mol Cell Proteomics. 2014;13:2513–2526. doi: 10.1074/mcp.m113.031591. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Grung B, Manne R. Missing values in principal component analysis. Chemom Intell Lab Syst. 1998;42:125–139. doi: 10.1016/S0169-7439(98)00031-8. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bennike TB, Carlsen TG, Ellingsen T, Bonderup OK, Glerup H, Bøgsted M, et al. Neutrophil extracellular traps in ulcerative colitis. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2015;1:1. doi: 10.1097/MIB.0000000000000460. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bhatia VN, Perlman DH, Costello CE, McComb ME. Software tool for researching annotations of proteins: open-source protein annotation software with data visualization. Anal Chem. 2009;81:9819–9823. doi: 10.1021/ac901335x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bennike TB, Ellingsen T, Glerup H, Bonderup OK, Carlsen TG, Meyer MK, et al. Proteome analysis of rheumatoid arthritis gut mucosa. J Proteome Res. 2017;16:356–364. doi: 10.1021/acs.jproteome.6b00598. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bennike T, Ayturk U, Haslauer CM, Froehlich JW, Proffen BL, Barnaby O, et al. A normative study of the synovial fluid proteome from healthy porcine knee joints. J Proteome Res. 2014;13:4377–4387. doi: 10.1021/pr500587x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hashimoto T, Yoshida K, Hashimoto N, Nakai A, Kaneshiro K, Suzuki K, et al. Circulating cell free DNA: a marker to predict the therapeutic response for biological DMARDs in rheumatoid arthritis. Int J Rheum Dis. 2017;20:722–730. doi: 10.1111/1756-185X.12959. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Pérez-Sánchez C, Ruiz-Limón P, Aguirre MA, Jiménez-Gómez Y, Arias-delaRosa I, Ábalos-Aguilera MC, et al. Diagnostic potential of NETosis-derived products for disease activity, atherosclerosis and therapeutic effectiveness in Rheumatoid Arthritis patients. J Autoimmun. 2017;82:31–40. doi: 10.1016/j.jaut.2017.04.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Haw R, Hermjakob H, D’Eustachio P, Stein L. Reactome pathway analysis to enrich biological discovery in proteomics data sets. Proteomics. 2011;11:3598–3613. doi: 10.1002/pmic.201100066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kramer PA, Ravi S, Chacko B, Johnson MS, Darley-Usmar VM. A review of the mitochondrial and glycolytic metabolism in human platelets and leukocytes: implications for their use as bioenergetic biomarkers. Redox Biol. 2014;2:206–210. doi: 10.1016/j.redox.2013.12.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kaplan MJ, Radic M. Neutrophil extracellular traps: double-edged swords of innate immunity. J Immunol. 2012;189:2689–2695. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1201719. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Urban CF, Ermert D, Schmid M, Abu-Abed U, Goosmann C, Nacken W, et al. Neutrophil extracellular traps contain calprotectin, a cytosolic protein complex involved in host defense against Candida albicans. PLoS Pathog. 2009;5:8. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000639. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Carmona-Rivera C, Zhao W, Yalavarthi S, Kaplan MJ. Neutrophil extracellular traps induce endothelial dysfunction in systemic lupus erythematosus through the activation of matrix metalloproteinase-2. Ann Rheum Dis. 2015;74:1417–1424. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2013-204837. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Jiang S, Park DW, Tadie J-M, Gregoire M, Deshane J, Pittet JF, et al. Human resistin promotes neutrophil proinflammatory activation and neutrophil extracellular trap formation and increases severity of acute lung injury. J. Immunol. 2014;192:4795–4803. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1302764. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sato H, Muraoka S, Kusunoki N, Masuoka S, Yamada S, Ogasawara H, et al. Resistin upregulates chemokine production by fibroblast-like synoviocytes from patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Res. Ther. 2017;19:6–11. doi: 10.1186/s13075-017-1472-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Vigushin DM, Pepys MB, Hawkins PN. Metabolic and scintigraphic studies of radioiodinated human C-reactive protein in health and disease. J Clin Invest. 1993;91:1351–1357. doi: 10.1172/JCI116336. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Larson LM, Namaste SM, Williams AM, Engle-Stone R, Addo OY, Suchdev PS, et al. Adjusting retinol-binding protein concentrations for inflammation: Biomarkers Reflecting Inflammation and Nutritional Determinants of Anemia (BRINDA) project. Am J Clin Nutr. 2017;106:390S–401S. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.116.142166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ritchie RF, Palomaki GE, Neveux LM, Navolotskaia O, Ledue TB, Craig WY. Reference distributions for alpha2-macroglobulin: a practical, simple and clinically relevant approach in a large cohort. J Clin Lab Anal. 2004;18:139–147. doi: 10.1002/jcla.20012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Greisen SR, Moller HJ, Stengaard-Pedersen K, Hetland ML, Hørslev-Petersen K, Jørgensen A, et al. Soluble macrophage-derived CD163 is a marker of disease activity and progression in early rheumatoid arthritis. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 2011;29:689–692. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Yan L, Borregaard N, Kjeldsen L, Moses MA. The high molecular weight urinary matrix metalloproteinase (MMP) activity is a complex of gelatinase B/MMP-9 and neutrophil gelatinase-associated lipocalin (NGAL): modulation of MMP-9 activity by NGAL. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:37258–37265. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M106089200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Katano M, Okamoto K, Arito M, Kawakami Y, Kurokawa MS, Suematsu N, et al. Implication of granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor induced neutrophil gelatinase-associated lipocalin in pathogenesis of rheumatoid arthritis revealed by proteome analysis. Arthritis Res Ther. 2009;11:R3. doi: 10.1186/ar2587. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Sopata I, Wize J, Filipowicz-Sosnowska A, Stanisławska-Biernat E, Brzezińska B, Maślinński S. Neutrophil gelatinase levels in plasma and synovial fluid of patients with rheumatic diseases. Rheumatol Int. 1995;15:9–14. doi: 10.1007/BF00286763. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ahrens D, Koch AE, Pope RM, Stein-Picarella M, Niedbala MJ. Expression of matrix metalloproteinase 9 (96-kd gelatinase B) in human rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 1996;39:1576–1587. doi: 10.1002/art.1780390919. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Zhou M, Qin S, Chu Y, Wang F, Chen L, Lu Y. Immunolocalization of MMP-2 and MMP-9 in human rheumatoid synovium. Int J Clin Exp Pathol. 2014;7:3048–3056. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Burmester GR, McInnes IB, Kremer JM, Miranda P, Vencovský J, Godwood A, et al. Mavrilimumab, a fully human granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor receptor α monoclonal antibody. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2018;70:679–689. doi: 10.1002/art.40420. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Lee S, Lee HC, Kwon YW, Lee SE, Cho Y, Kim J, et al. Adenylyl cyclase-associated protein 1 is a receptor for human resistin and mediates inflammatory actions of human monocytes. Cell Metab . 2014;19:484–497. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2014.01.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Wells G, Becker J-C, Teng J, Dougados M, Schiff M, Smolen J, et al. Validation of the 28-joint Disease Activity Score (DAS28) and European League Against Rheumatism response criteria based on C-reactive protein against disease progression in patients with rheumatoid arthritis, and comparison with the DAS28 based on erythr. Ann Rheum Dis. 2009;68:954–960. doi: 10.1136/ard.2007.084459. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Bini L, Magi B, Marzocchi B, Cellesi C, Berti B, Raggiaschi R, et al. Two-dimensional electrophoretic patterns of acute-phase human serum proteins in the course of bacterial and viral diseases. Electrophoresis. 1996;17:612–616. doi: 10.1002/elps.1150170333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Shirai R, Hirano F, Ohkura N, Ikeda K, Inoue S. Up-regulation of the expression of leucine-rich α2-glycoprotein in hepatocytes by the mediators of acute-phase response. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2009;382:776–779. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2009.03.104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Druhan LJ, Lance A, Li S, Price AE, Emerson JT, Baxter SA, et al. Leucine rich α-2 glycoprotein: a novel neutrophil granule protein and modulator of myelopoiesis. PLoS ONE. 2017;12:e0170261. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0170261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Taketazu F, Kato M, Gobl A, Ichijo H, ten Dijke P, Itoh J, et al. Enhanced expression of transforming growth factor-beta s and transforming growth factor-beta type II receptor in the synovial tissues of patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Lab Invest. 1994;70:620–630. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Fujimoto M, Serada S, Suzuki K, Nishikawa A, Ogata A, Nanki T, et al. Brief report: leucine-rich α 2 -glycoprotein as a potential biomarker for joint inflammation during anti-interleukin-6 biologic therapy in rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2015;67:2056–2060. doi: 10.1002/art.39164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Schett G, Elewaut D, McInnes IB, Dayer JM, Neurath MF. Toward a cytokine-based disease taxonomy. Nat Med Nat Med. 2013;19:822–824. doi: 10.1038/nm.3260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.McGonagle D, Watad A, Savic S. Mechanistic immunological based classification of rheumatoid arthritis. Autoimmun. Rev. 2018;17:1115–1123. doi: 10.1016/j.autrev.2018.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Nakazawa D, Masuda S, Tomaru U, Ishizu A. Pathogenesis and therapeutic interventions for ANCA-associated vasculitis. Nat Rev Rheumatol. 2019;15:91–101. doi: 10.1038/s41584-018-0145-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Wilkinson AN, Gartlan KH, Kelly G, Samson LD, Olver SD, Avery J, et al. Granulocytes are unresponsive to IL-6 due to an absence of gp130. J Immunol. 2018;200:3547–3555. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1701191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Additional file 1. Combined list of identified proteins in all samples.

Data Availability Statement

The raw- and processed data have been made available via ProteomeXchange with identifier PXD010723