Abstract

The mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) cascade is a highly conserved signaling transduction module that transduces extracellular stimuli into intracellular responses in plants. Early studies of plant MAPKs focused on their functions in model plants. Based on the results of whole-genome sequencing, many MAPKs have been identified in horticultural plants, such as tomato and apple. Recent studies revealed that the MAPK cascade also plays crucial roles in the biotic and abiotic stress responses of horticultural plants. In this review, we summarize the composition and classification of MAPK cascades in horticultural plants and recent research on this cascade in responses to abiotic stresses (such as drought, extreme temperature and high salinity) and biotic stresses (such as pathogen infection). In addition, we discuss the most advanced research themes related to plant MAPK cascades, thus facilitating research on MAPK cascade functions in horticultural plants.

Keywords: signal transduction, MAPK cascades, horticultural plant, biotic stress, abiotic stress

Introduction

Horticultural plants, including fruits, vegetables, ornamental trees and flowers, are important economically valuable crops around the world. However, during plant growth and development, horticultural crops often suffer from a variety of stresses, including biotic stresses (e.g., diseases, pests) and abiotic stresses (e.g., drought, extreme temperature, high salinity), and these stresses seriously affect the quality and yield of these crops (Bai et al., 2018). In the process of resisting adverse stresses, plants have evolved sophisticated, complex and effective defense mechanisms, including signal perception, signal transduction, transcriptional regulation and immune responses, to reduce or avoid damage (Kissoudis et al., 2014). Studying the damage to plants caused by stresses and the response mechanisms of plants under stresses has become one of the focuses in plant stress resistance research.

Phosphorylation is a very important posttranslational modification (PTM) and the main method of signal transduction. The phosphorylation of proteins can transmit and amplify external signals by changing the expression of downstream genes and other biological processes (Wang et al., 2019). Protein kinases are a class of enzymes that catalyze the phosphorylation of related proteins, and the serine/threonine protein kinase family of mitogen-activated protein kinases (MAPKs) is one of the most widely studied gene families.

MAPKs are highly conserved signaling transduction modules and participate in many signal transduction processes through MAPK cascades. A typical MAPK cascade is composed of MAPK (MPK), MAPK kinase (MAPKK, MAP2K, MKK or MEK) and MAPK kinase kinase (MAPKKK, MAP3K or MEKK) (Ichimura et al., 2002; Rodriguez et al., 2010). In a classical MAPK signaling cascade, MAPKKK is activated by stimulated plasma membrane receptors and transmits signals downstream (Wang et al., 2014; Çakır and Kılıçkaya, 2015). MAPKKK activates MAPKK by phosphorylating the conserved S/T-XXXXX-S/T (S/T is serine/threonine, and X is an arbitrary amino acid) motif in MAPKK (Rodriguez et al., 2010). Subsequently, MAPKK activates MAPK by phosphorylating the TXY (T is threonine, Y is tyrosine, and X is any amino acid) motif in MAPK (Taj et al., 2010). Finally, MAPK activates downstream kinases, enzymes, transcription factors and other response factors and transmits extracellular environmental signals into cells (Zhang M. et al., 2018). Through stage-by-stage phosphorylation, the MAPK cascade can transmit and amplify signals to downstream proteins and activate the expression of resistance genes (Hamel et al., 2006). MAPKs regulate the expression of many genes through the phosphorylation of proteins, especially the phosphorylation of many transcription factors (Morris, 2001; Zhang and Klessig, 2001). The MAPK cascade plays important roles in mediating cell differentiation, cell development, hormonal activity, and abiotic and biotic stress responses (Komis et al., 2018). Increasing evidence indicates that genetic manipulation of the abundance or activity of some MAPK components can enhance tolerance to many stresses in crop plant species (Šamajová et al., 2013). In recent years, the function of MAPK cascades in horticultural plants has received widespread attention. This review summarizes the composition and classification of MAPK cascades in horticultural plants and the roles of MAPK signaling pathways in biotic and abiotic stresses responses.

Composition and Classification of MAPK Cascades in Horticultural Plants

Similar to model plants, the horticultural plant MAPK cascade also consists of three parts: MAPKKK, MAPKK and MAPK. By analyzing the genomes of various plants, the number of MAPKKKs was found to be the highest among the three superfamilies in the MAPK cascade, followed by MAPK and finally MAPKK (Xu and Zhang, 2015). A total of 80 MAPKKKs, 10 MAPKKs and 20 MAPKs have been reported in Arabidopsis thaliana (Colcombet and Hirt, 2008). Due to the development of whole-genome sequencing technology, many MAPK cascade components have been identified in horticultural plants. Eighty-nine MAPKKKs, five MAPKKs and 16 MAPKs can be found in tomato (Solanum lycopersicum) (Kong et al., 2012; Wu et al., 2014). Recent studies have demonstrated that 120 MAPKKKs, 9 MAPKKs and 26 MAPKs are present in the apple genome (Zhang et al., 2013; Sun et al., 2017). The cucumber (Cucumis sativus L.) genome-sequencing project discovered 59 MAPKKKs, six MAPKKs and 14 MAPKs (Wang et al., 2015). Twelve FvMAPKs, seven FvMAPKKs and 73 FvMAPKKKs were verified from the recently published strawberry (Fragaria vesca) genome (Shulaev et al., 2011; Zhou et al., 2017). The grapevine (Vitis vinifera) genome contains 14 MAPKs, five MAPKKs and 62 MAPKKKs (Çakır and Kılıçkaya, 2015).

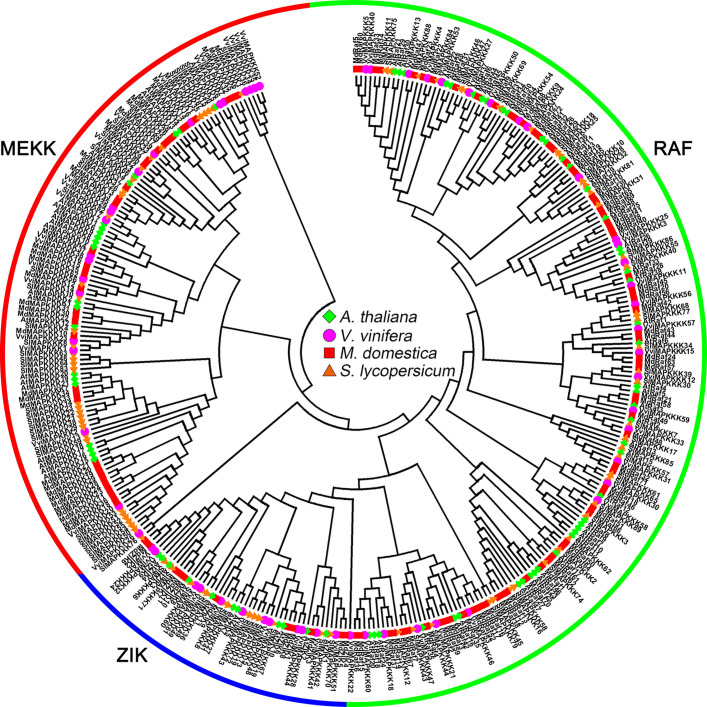

According to characteristic sequence motifs, MAPK family genes (MAPKs, MAPKKs and MAPKKKs) have been divided into many subfamilies. Based on genome sequencing data, dendrogram analysis was used to classify MAPK family genes from three typical horticultural plants (tomato, grapevine and apple) using Arabidopsis as the standard. MAPKKK can be subdivided into three groups in higher plants: the MEKK subfamily, Raf subfamily and ZIK (ZR1-interacting kinase) subfamily (Rodriguez et al., 2010). In the members of the MEKK subfamily, a conserved G(T/S)Px(W/Y/F)MAPEV kinase domain can be found; most ZIK subfamily proteins have the GTPEFMAPE(L/V)Y domain, while Raf subfamily members have the GTxx(W/Y)MAPE domain (Jonak et al., 2002). The Raf and ZIK subfamily proteins have a C-terminal kinase domain (KD) and a long N-terminal regulatory domain (RD) that might function in scaffolding to recruit MAPKKs and MAPKs (Ichimura et al., 2002; Rodriguez et al., 2010). MEKK subfamily members have a less conserved protein structure compared with the ZIK subfamily and Raf subfamily (Rao et al., 2010; Rodriguez et al., 2010). In the tomato genome, 89 putative MAPKKKs have been identified, including 33 MEKK subfamily members, 16 ZIK subfamily members, and 40 Raf subfamily members ( Figure 1 ) (Wu et al., 2014). Among the 62 MAPKKKs identified in grapevine, 21 VviMAPKKKs were in the MEKK subfamily, only 12 VviMAPKKKs belonged to the ZIK subfamily, and 29 VviMAPKKKs were grouped in the Raf subfamily ( Figure 1 ) (Çakır and Kılıçkaya, 2015). In apple, a total of 72 putative MdMAPKKKs were identified in the Raf subfamily, 11 in the ZIK subfamily and 37 in the MEKK subfamily ( Figure 1 ) (Sun et al., 2017).

Figure 1.

Phylogenetic analysis of MAPKKKs in various species. A total of 62 VviMAPKKKs from grapevine, 120 MdMAPKKKs from apple, 89 SlMAPKKKs from tomato and 78 AtMAPKKKs from Arabidopsis were used to create the neighbor-joining (NJ) tree using MEGA-X with 1,000 bootstraps.

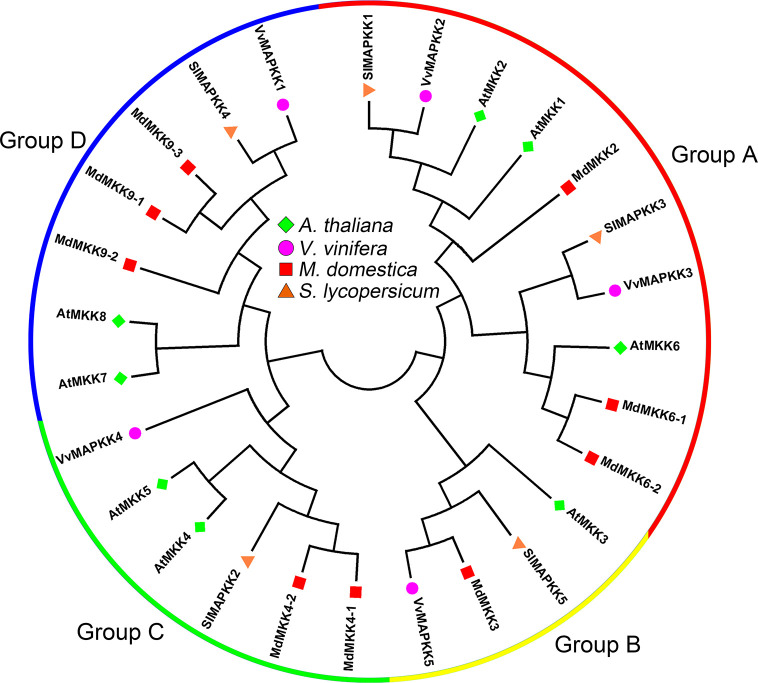

MAPKKs can be divided into four groups, A, B, C and D, according to amino acid sequence analysis (Ichimura et al., 2002). Among the five tomato MAPKKs, SlMAPKK1 and SlMAPKK3 belong to group A, SlMAPKK5 belongs to group B, SlMAPKK2 belongs to group C, and SlMAPKK4 belongs to group D ( Figure 2 ) (Wu et al., 2014). For grapevine MAPKKs, VvMKK2 and VvMKK3 were highly homologous with group A MAPKKs (AtMKK1, AtMKK2 and AtMKK6) in Arabidopsis, VvMKK5 was highly homologous with group B MAPKKs (AtMKK3) in Arabidopsis, VvMKK4 was highly homologous with group C MAPKKs (AtMKK4 and AtMKK5) in Arabidopsis, and VvMKK1 was highly homologous with group D MAPKKs (AtMKK8) in Arabidopsis ( Figure 2 ) (Çakır and Kılıçkaya, 2015). Among the 9 MKKs of apple, MKK2, MKK6-1 and MKK6-2 belong to group A, MKK3 belongs to group B, MKK4-1 and MKK4-2 belong to group C, and MKK9-1, MKK9-2 and MKK9-3 belong to group D ( Figure 2 ) (Zhang et al., 2013).

Figure 2.

Phylogenetic analysis of MAPKKs in various species. A total of 5 VviMAPKKs from grapevine, 9 MdMAPKKs from apple, 5 SlMAPKKs from tomato, and eight AtMAPKKs from Arabidopsis were used to create the neighbor-joining (NJ) tree using MEGA-X with 1,000 bootstraps. Four clades were labeled as Group A, Group B, Group C and Group D.

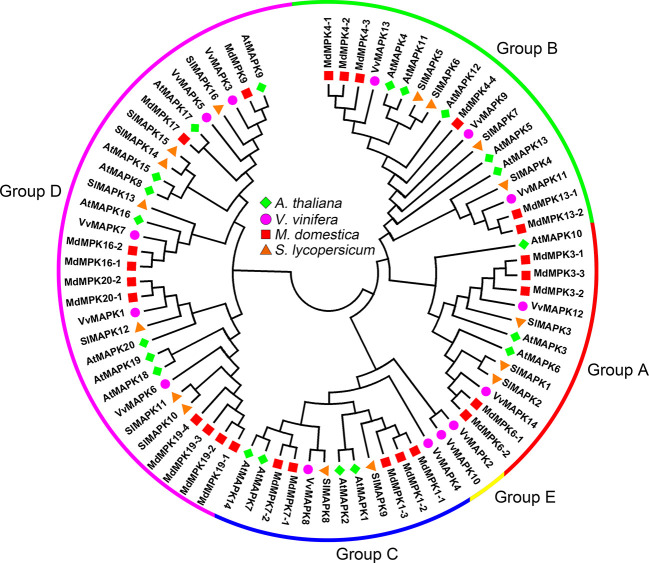

According to the conserved T-X-Y motif phosphorylated by MAPKK, MAPKs can be divided into two subfamilies, with one containing TEY motifs and the other containing TDY motifs. Subfamilies containing TEY motifs can be classified into three groups based on their structural features and sequences (Jonak et al., 2002). In the tomato genome, three MAPK genes (SlMAPK1–3) belong to group A, four MAPK genes (SlMAPK4–7) belong to group B, two MAPK genes (SlMAPK8–9) belong to group C, and seven MAPK genes (SlMAPK10–16) belong to group D ( Figure 3 ) (Kong et al., 2012). Although the grapevine genome contains fewer MAPKs than the Arabidopsis genome (20 MAPKs), the VvMAPKs have been divided into five subfamilies, which are different from those in other plant species (Çakır and Kılıçkaya, 2015). VvMAPK12 and VvMAPK14 are clustered in group A, VvMAPK9, VvMAPK11, and VvMAPK13 belong to group B, VvMAPK4 and VvMAPK8 are clustered in group C, the group D MAPKs in grapevine include VvMAPK1, VvMAPK3, VvMAPK5, VvMAPK6 and VvMAPK7, and VvMAPK2 and VvMAPK10 belong to group E, separate from the other groups ( Figure 3 ) (Çakır and Kılıçkaya, 2015). The MAPK gene family in apple is by far the largest compared to the estimates for other plant species. The phylogenetic tree divided the MAPKs into four groups (groups A, B, C and D) of monophyletic clades. Groups A and C both contain five apple MAPK genes, followed by group B (6 genes), and group D constitutes the largest clade containing 10 MdMAPKs ( Figure 3 ) (Zhang et al., 2013).

Figure 3.

Phylogenetic analysis of MAPKs in various species. A total of 14 VviMAPKs from grapevine, 26 MdMAPKs from apple, 16 SlMAPKs from tomato and 20 AtMAPKs from Arabidopsis were used to create the neighbor-joining (NJ) tree using MEGA-X with 1,000 bootstraps.

The Function of MAPK Cascades in Responses to Abiotic Stresses in Horticultural Plants

Facing abiotic stresses, such as drought, extreme temperature, and salinity, plants have generated specific mechanisms that can activate secondary messenger-mediated signal transduction, regulate the expression of resistance genes and ultimately help plants adapt and survive under these adverse stresses (Zhu, 2016; Zandalinas et al., 2019). In horticultural plants, MAPK cascades participate in responses to numerous abiotic stresses, including drought, extreme temperature, salinity, ozone and UV irradiation ( Table 1 ) (Ramani and Chelliah, 2007; Meng et al., 2014; Zhou et al., 2014; Yanagawa et al., 2016; Ji et al., 2017).

Table 1.

Overview of MAPKs involved in different stress responses in different species.

| Species | Gene Name | Response to Stress | Up/Down Regulated | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Actinidia Chinensis | AcMAPK4 | Salt Stress | up | Wang G. et al., 2018 |

| AcMAPK5 | Salt Stress | up | Wang G. et al., 2018 | |

| AcMAPK9 | Salt Stress | up | Wang G. et al., 2018 | |

| AcMAPK12 | Salt Stress | up | Wang G. et al., 2018 | |

| Brassica napus | BnMAPK1 | Response to Drought Stress |

Weng et al., 2014 | |

| Brassica rapa | BraMKK9 | Plasmodiophora brassicae infection | up | Piao et al., 2018 |

| BraMPK1 | Plasmodiophora brassicae infection | up | Piao et al., 2018 | |

| BraMPK2 | Plasmodiophora brassicae infection | up | Piao et al., 2018 | |

| BraMPK5 | Plasmodiophora brassicae infection | up | Piao et al., 2018 | |

| BraMPK9 | Plasmodiophora brassicae infection | up | Piao et al., 2018 | |

| BraMPK19 | Plasmodiophora brassicae infection | up | Piao et al., 2018 | |

| BraMPK20 | Plasmodiophora brassicae infection | up | Piao et al., 2018 | |

| Chrysanthemum morifolium | CmMPK1 | Low-temperature Stress | up | Song et al., 2018 |

| CmMPK3.1 | Low-temperature Stress | up | Song et al., 2018 | |

| CmMPK3.2 | Low-temperature Stress | up | Song et al., 2018 | |

| CmMPK4.2 | Low-temperature Stress | up | Song et al., 2018 | |

| CmMPK6 | Low-temperature Stress | up | Song et al., 2018 | |

| CmMPK9.1 | Low-temperature Stress | up | Song et al., 2018 | |

| CmMPK9.2 | Low-temperature Stress | up | Song et al., 2018 | |

| CmMPK13 | Low-temperature Stress | up | Song et al., 2018 | |

| CmMPK16 | Low-temperature Stress | up | Song et al., 2018 | |

| CmMPK18 | Low-temperature Stress | up | Song et al., 2018 | |

| CmMPK1 | High-temperature Stress | down | Song et al., 2018 | |

| CmMPK9.1 | High-temperature Stress | down | Song et al., 2018 | |

| CmMPK9.2 | High-temperature Stress | down | Song et al., 2018 | |

| CmMPK16 | High-temperature Stress | down | Song et al., 2018 | |

| CmMPK18 | High-temperature Stress | down | Song et al., 2018 | |

| CmMPK4.2 | Salt and Drought Stresses | up | Song et al., 2018 | |

| CmMPK13 | Salt and Drought Stresses | up | Song et al., 2018 | |

| CmMKK2 | Salt and Drought Stresses | up | Song et al., 2018 | |

| CmMKK4 | Salt and Drought Stresses | up | Song et al., 2018 | |

| Citrus sinensis | CsMAPK1 | Response to Xanthomonas citri Infection |

de Oliveira et al., 2013 | |

| Response to Xanthomonas aurantifolii Infection | ||||

| Cucumis sativus | CsMKK4 | High-temperature Stress | up | Wang et al., 2015 |

| Fragaria vesca | FvMAPK5 | Drought Stress | up | Zhou et al., 2017 |

| FvMAPK8 | Drought Stress | up | Zhou et al., 2017 | |

| FvMAPK3 | High-temperature Stress | up | Zhou et al., 2017 | |

| FvMAPKK1 | High-temperature Stress | up | Zhou et al., 2017 | |

| FvMAPKK3 | High-temperature Stress | up | Zhou et al., 2017 | |

| FvMAPKK6 | High-temperature Stress | up | Zhou et al., 2017 | |

| FvMAPKK7 | High-temperature Stress | up | Zhou et al., 2017 | |

| FvMAPK5 | Salt Stress | up | Zhou et al., 2017 | |

| FvMAPK9 | Salt Stress | up | Zhou et al., 2017 | |

| FvMAPK10 | Salt Stress | up | Zhou et al., 2017 | |

| FvMAPK11 | Salt Stress | up | Zhou et al., 2017 | |

| FvMAPK12 | Salt Stress | up | Zhou et al., 2017 | |

| FvMAPKK1 | Salt Stress | up | Zhou et al., 2017 | |

| FvMAPKK3 | Salt Stress | up | Zhou et al., 2017 | |

| FvMAPKK5 | Salt Stress | up | Zhou et al., 2017 | |

| Malus | MaMAPK | Drought Stress | up | Peng et al., 2006 |

| MdRaf5 | Respnose to Drought Stress |

Sun et al., 2017 | ||

| Manihot esculenta | MeMAPK4 | Salt Stress | down | Yan et al., 2016 |

| MeMAPK16 | Salt Stress | down | Yan et al., 2016 | |

| MeMAPK17 | Salt Stress | down | Yan et al., 2016 | |

| MeMAPK19 | Salt Stress | down | Yan et al., 2016 | |

| MeMAPK1 | Salt Stress | up | Yan et al., 2016 | |

| Moraceae morus | MnMAPK1 | Drought Stress | down | Wei et al., 2014 |

| MnMAPK2 | Drought Stress | down | Wei et al., 2014 | |

| MnMAPK3 | Drought Stress | up | Wei et al., 2014 | |

| MnMAPK4 | Drought Stress | up | Wei et al., 2014 | |

| MnMAPK6 | Drought Stress | up | Wei et al., 2014 | |

| MnMAPK7 | Drought Stress | up | Wei et al., 2014 | |

| MnMAPK8 | Drought Stress | up | Wei et al., 2014 | |

| MnMAPK9 | Drought Stress | up | Wei et al., 2014 | |

| MnMAPK1 | High-temperature Stress | up | Wei et al., 2014 | |

| MnMAPK5 | High-temperature Stress | up | Wei et al., 2014 | |

| MnMAPK6 | High-temperature Stress | up | Wei et al., 2014 | |

| MnMAPK9 | High-temperature Stress | up | Wei et al., 2014 | |

| MnMAPK2 | High-temperature Stress | down | Wei et al., 2014 | |

| MnMAPK3 | High-temperature Stress | down | Wei et al., 2014 | |

| MnMAPK8 | High-temperature Stress | down | Wei et al., 2014 | |

| MnMAPK10 | High-temperature Stress | down | Wei et al., 2014 | |

| MnMAPK1 | Low-temperature Stress | up | Wei et al., 2014 | |

| MnMAPK5 | Low-temperature Stress | up | Wei et al., 2014 | |

| MnMAPK1 | Salt Stress | up | Wei et al., 2014 | |

| MnMAPK9 | Salt Stress | up | Wei et al., 2014 | |

| MnMAPK10 | Salt Stress | up | Wei et al., 2014 | |

| MnMAPK3 | Salt Stress | down | Wei et al., 2014 | |

| MnMAPK4 | Salt Stress | down | Wei et al., 2014 | |

| MnMAPK7 | Salt Stress | down | Wei et al., 2014 | |

| MnMAPK8 | Salt Stress | down | Wei et al., 2014 | |

| Poncirus trifoliata | PtrMAPK | Drought Stress | up | Huang et al., 2011 |

| Solanum lycopersicum | SlMPK1 | High-temperature Stress | down | Ding et al., 2018 |

| SlMPK3 | Low-temperature Stress | up | Yu et al., 2015 | |

| SlMPK1 | Response to Herbivorous Insects Infection |

Kandoth et al., 2007 | ||

| SlMPK2 | Response to Herbivorous Insects Infection |

Kandoth et al., 2007 | ||

| SlMPK3 | Response to Herbivorous Insects Infection |

Kandoth et al., 2007 | ||

| SlMPK2 | Response to Xanthomonas campestris Infection |

Melech-Bonfil and Sessa, 2011 | ||

| SlMPK3 | Response to Xanthomonas campestris Infection |

Mayrose et al., 2004 | ||

| SlMKK2 | Response to Pseudomonas syringae Infection |

Pedley and Martin, 2004 | ||

| SlMKK4 | Response to Pseudomonas syringae Infection |

Pedley and Martin, 2004 | ||

| SlMAPKKKϵ | Response to Xanthomonas campestris Infection | Melech-Bonfil and Sessa, 2010 | ||

| Response to Pseudomonas syringae Infection | ||||

| Solanum tuberosm | StMEK2 | Response to Phytophthora infestans Infection |

Wang H. et al., 2018 | |

| Vitis vinifera | VviMAPKKK22 | Drought Stress | up | Wang et al., 2014 |

| VviMAPKKK23 | Drought Stress | up | Wang et al., 2014 | |

| VviMAPKKK51 | Drought Stress | up | Wang et al., 2014 | |

| VviMAPKKK54 | Drought Stress | up | Wang et al., 2014 | |

| VviMAPKKK31 | Erysiphe necator Infection | up | Wang et al., 2014 | |

| VviMAPKKK32 | Erysiphe necator Infection | up | Wang et al., 2014 | |

| VviMAPKKK34 | Erysiphe necator Infection | up | Wang et al., 2014 | |

| VviMAPKKK38 | Erysiphe necator Infection | up | Wang et al., 2014 | |

| VviMAPKKK39 | Erysiphe necator Infection | up | Wang et al., 2014 | |

| VviMAPKKK46 | Erysiphe necator Infection | up | Wang et al., 2014 | |

| VviMAPKKK50 | Erysiphe necator Infection | up | Wang et al., 2014 | |

| VviMAPKKK4 | Powdery mildew Infection | down | Wang et al., 2014 | |

| VviMAPKKK51 | Powdery mildew Infection | down | Wang et al., 2014 | |

| VviMAPKKK54 | Powdery mildew Infection | down | Wang et al., 2014 | |

MAPK Cascades Involved in Regulating Drought Tolerance

Drought is a major environmental factor limiting the productivity and distribution of plants (Shi et al., 2011; Zhang H. et al., 2018). Horticultural plant roots are extensive and substantially affected by the soil moisture content, and their growth and products are therefore seriously influenced by drought stress. Analyzing the molecular mechanism of drought tolerance has great significance for breeding drought-tolerant varieties. The MAPK cascade plays an important role in the drought stress response in horticultural plants. Three species of Malus were used to study the expression of MAPKs in response to drought stress: Malus hupehensis, a drought-sensitive species; Malus sieversii, a drought-tolerant species; and Malus micromalus, a species with moderate tolerance (Peng et al., 2006). The highest expression level of MaMAPK (GenBank accession No. AF435805) was observed in M. sieversii, followed by M. micromalus and M. hupehensis. MaMAPK was dramatically induced after drought treatment for 1.5 h. This expression pattern was consistent with antioxidant enzyme activity in three apple species under drought treatment (Peng et al., 2006). Mounting evidence indicates that MAPK cascades play important roles in regulating drought tolerance in apple. In four apple species, Malus hupehensis (Pamp.) Rehd. var. pinyiensis, Malus hupehensis (Pamp.) Rehd. var. taishanensis, Malus baccata (L.) Borkn and Malus sieversii (Ledeb.) Roem, 12 MAPKKKs were highly regulated in leaves treated with 20% PEG for 3 h (Sun et al., 2017). Overexpression of MdRaf5, an MAPKKK Raf-like group gene, dramatically enhanced drought tolerance in transgenic Arabidopsis plants by reducing transpiration rates and stomatal apertures (Sun et al., 2017). A recent study reported that arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi (AMF) can enhance drought tolerance by using MAPK signals for interactions between AMF and their apple plant hosts (Huang et al., 2020). During drought, the expression levels of MdMAPK16-2, MdMAPK17 and MdMAPK20-1 were increased by 36.93%, 58.14% and 54.14%, respectively, compared to those in apple seedlings without AMF inoculation (Huang et al., 2020). Exclusive activation of some MAPK kinases occurs in drought-treated horticultural plants. BnMAPK1 may be related to the response to drought stress in Brassica napus, and overexpression of BnMAPK1 enhanced drought tolerance by increasing cell water retention and root activity (Weng et al., 2014). In cucumber, all examined CsMAPKs were initially downregulated for the first 2 days before they were significantly upregulated after drought treatment (Wang et al., 2015). In strawberry, FvMAPK5 and FvMAPK8 belong to group B, which contains well-characterized MAPK genes, including AtMAPK3 and AtMAPK6 (Zhou et al., 2017). Research has indicated that FvMAPK5 and FvMAPK8 are important for abiotic stress responses, with functions similar to those of AtMAPK3 and AtMAPK6 due to transcriptional activation by drought (Zhou et al., 2017). In trifoliate orange (Poncirus trifoliata L. Raf), transcript levels of MAPKs were increased by dehydration (Huang et al., 2011). Overexpression of PtrMAPK had a significant effect on the improvement of drought tolerance in transgenic tobacco plants. The morphological appearances of PtrMAPK-overexpression transgenic lines were better than those of WT plants as more leaves remained green in the transgenic lines (Huang et al., 2011). In mulberry, eight MnMAPKs were significantly induced by drought treatment, and two MnMAPKs (MnMAPK1 and MnMAPK2) were significantly downregulated (Wei et al., 2014). Six MnMAPKs (MnMAPK3, MnMAPK4, MnMAPK6, MnMAPK7, MnMAPK8 and MnMAPK9) showed positively regulated expression, particularly MnMAPK7, which had very high expression levels after 10 days of drought treatment (Wei et al., 2014). In W14 (Manihot esculenta ssp. flabellifolia) subspecies, an ancestor of the wild cassava subspecies with strong drought tolerance, 20% of MeMAPK genes in leaves and 70% in roots were found to be induced by drought stress (Yan et al., 2016). The high ratio of drought-induced MeMAPK genes in roots indicates that MAPK genes may play a regulatory role in water uptake from soil by roots and may help maintain a strong tolerance to drought stress (Yan et al., 2016). When grapevine plants were subjected to drought stress, the expression levels of almost all VviMAPKKK genes significantly increased 8 days after drought treatment (Wang et al., 2014). VviMAPKKK22, VviMAPKKK23, VviMAPKKK51 and VviMAPKKK54 transcripts showed greater than 20-fold increased expression. This study provided the first insight into the possible involvement of grapevine MAPKKKs in drought stress (Wang et al., 2014). These results indicated that MAPK cascades play important roles in response to drought stress in horticultural plants.

MAPK Cascades Involved in Response to Extreme Temperature Stress

Temperature as an important environmental factor has an increasingly significant effect on plant growth and development (Quint et al., 2016). When plants suffer abnormal temperature, the cells present with dehydration, the intracellular pH and osmotic pressure increase, the plasma membrane system and cell structure are damaged, and the functions of organelles such as chloroplasts and mitochondria are abnormal, ultimately leading to metabolic disorders and causing significant losses in plant productivity (Yamazaki et al., 2009; Yin et al., 2014; Lohani et al., 2020). In model plants, MAPK cascades play an important role in response to temperature stress. The MAPK cascade in Brachypodium distachyon was temperature sensitive: 90% of the examined MAPK cascade genes were induced under cold stress, and 60% of the genes were induced by high temperature stress in B. distachyon (Jiang et al., 2015). In horticultural plants, SlMPK1 and SlMPK2, which are two MAPK genes in tomato (Solanum lycopersicum), are involved in brassinosteroid-mediated oxidative and heat stresses (Nie et al., 2013). SlMPK1 is a negative regulator of thermotolerance in tomato plants. Silencing of SlMPK1 in transgenic tomato enhances high-temperature tolerance, whereas SlMPK1-overexpression transgenic lines displayed lower tolerance to high temperature, with low levels of antioxidative enzyme activities and high levels of H2O2 and MDA (Ding et al., 2018). SlMPK3 is a low-temperature stress response gene. Transgenic plants overexpressing SlMPK3 exhibited a higher seed germination rate and longer root length than wild-type plants. Overexpression of SlMPK3 increased the activity of antioxidant enzymes, elevated the intracellular levels of proline and soluble sugars, and enhanced plant resistance under cold stress conditions (Yu et al., 2015). In cucumber, most of the MAPK cascade genes could be induced by extreme temperature treatment. Most of the examined CsMAPKs (except for CsMPK3 and CsMPK7) were upregulated, and the transcripts of CsMKK4 exhibited a pronounced increase at 8 h after heat treatment (Wang et al., 2015). In Fragaria vesca, the expression of 17 of the 19 MAPK genes (FvMAPK1-12; FvMPKK1-7) increased significantly at 18 days after flowering during low-temperature treatment, while the transcript levels of FvMAPK3, FvMPKK1, FvMPKK3, FvMPKK6 and FvMPKK7 were significantly upregulated by high-temperature treatment (Zhou et al., 2017). Among these genes, FvMAPKK3 showed specific activation by cold and heat stresses (Zhou et al., 2017). Research results have shown that mulberry MAPK genes also participate in response to extreme temperature. Eight MnMAPK genes were significantly induced by 40°C high-temperature treatment (Wei et al., 2014). Among them, MnMAPK1, MnMAPK5, MnMAPK6 and MnMAPK9 were upregulated, and MnMAPK2, MnMAPK3, MnMAPK8 and MnMAPK10 were downregulated. Under low-temperature (4°C) treatment, the expression levels of MnMAPK1 and MnMAPK5 were significantly upregulated (Wei et al., 2014). The CmMPK1, CmMPK3.1, CmMPK3.2, CmMPK4.2, CmMPK6, CmMPK9.1, CmMPK9.2, CmMPK13, CmMPK16 and CmMPK18 genes in Chrysanthemum morifolium were induced after cold treatment, but the expression levels of CmMPK1, CmMPK3.1, CmMPK3.2, CmMPK4.2, CmMPK9.1, CmMPK9.2, CmMPK16 and CmMPK18 were decreased or remained unchanged after heat shock treatment for 1 h (Song et al., 2018). The available results indicated that MAPK cascades regulated tolerance to heat or cold stresses in horticultural plants.

MAPK Cascades Involved in Response to Salt Stress

Salinity, as the major threat to agricultural production, endangers more than 50% of irrigated lands worldwide (Hasegawa et al., 2000; Yamaguchi and Blumwald, 2005; Munns et al., 2020). Exposure of plants to salt stress leads to potential disruption of membranes and proteins accompanied by rising levels of reactive oxygen species (ROS) and ultimately results in growth inhibition and loss of crop yields (Krasensky and Jonak, 2012; Yang and Guo, 2018; Osthoff et al., 2019). Li et al. (2015) reported that activation of MAPK protein (recognized by a phosphospecific antibody (pTEpY) and the band between 44 kD and 47 kD) can promote the expression levels of V-H+-ATPase, leading to high tolerance to salt in Keyuan-1 peppermint (a salt-tolerant peppermint species). Recently, research showed that this MAPK protein exhibited time-dependent activation in Keyuan-1 peppermint during 12 days of treatment with 150 mM NaCl and primarily modulated the pathway of essential oil metabolism at the transcript and enzyme levels of salt-tolerant peppermint upon NaCl stress (Li et al., 2016). Fen Jiao banana (Musa ABB PisangAwak, FJ) has higher tolerance to abiotic stress than BaXi Jiao banana (Musa acuminate L. AAA group cv. Cavendish, BX) (Wang et al., 2017). Research results indicated that the ratio of MAPKK and MAPKKK genes upregulated by salt stress was higher in FJ than in BX, implying that the MAPK cascade may be more active in FJ than in BX in response to salt stress (Wang et al., 2017). In mulberry, MnMAPKs can be induced by salt stress. After high-salinity treatment, three MnMAPKs (MnMAPK1, MnMAPK9 and MnMAPK10) were significantly upregulated, and four MnMAPKs (MnMAPK3, MnMAPK4, MnMAPK7 and MnMAPK8) were significantly downregulated (Wei et al., 2014). In Chrysanthemum morifolium, CmMPK13 and CmMKK4 were induced by salt stress; they were specifically expressed in roots, and their expression was significantly increased after PEG or salt treatment (Song et al., 2018). In addition, the expression levels of CmMPK4.2 and CmMKK2 increased after high-salinity and PEG treatment, which were also shown to interact strongly in yeast. Therefore, CmMKK4-CmMPK13 and CmMKK2-CmMPK4 may be involved in regulating salt tolerance in C. morifolium (Song et al., 2018). In cassava, MAPK family genes might be positively or negatively involved in the salt stress response. With high-salinity treatment, MeMAPK4 was obviously inhibited at all treatment time points, and MeMAPK16, MeMAPK17 and MeMAPK19 were repressed at several treatment time points. MeMAPK1 showed upregulation at all treatment time points (Yan et al., 2016). In kiwifruit, with high-salinity treatment, the expression of AcMAPK4, AcMAPK5, AcMAPK9 and AcMAPK12 was significantly upregulated at all treatment time points, indicating that these genes might be important regulators in response to salt stress (Wang G. et al., 2018). Furthermore, in response to salt stress, the expression of five FvMAPK genes (FvMAPK5, FvMAPK9, FvMAPK10, FvMAPK11 and FvMAPK12) and three FvMAPKK genes (FvMAPKK1, FvMAPKK3 and FvMAPKK5) also increased in F. vesca, and the transcript levels of FvMAPKK3 in leaves were specifically activated by salt stress (Zhou et al., 2017). Mounting evidence has shown that MAPK cascades were the key regulator of the response to salt stress in horticultural plants.

The Function of MAPK Cascades in Responses to Biotic Stresses in Horticultural Plants

During their growth and development, plants are often attacked by bacteria, fungi and viruses. With long-term evolution, higher plants have formed a series of defense mechanisms to resist pathogen infection, such as programmed cell death, cell wall thickening, ROS accumulation, pathogenesis-related (PR) protein synthesis, and transcriptional activation of defense genes (Nejat and Mantri, 2017; Vaahtera et al., 2019). The MAPK cascade is known to be one of the earliest activated pathways during defense activation in response to pathogenic infection (Bi and Zhou, 2017). MAPK cascades are involved in multiple defense responses, including the signaling of plant defense hormones, ROS generation, defense gene activation, and hypersensitive response (HR) cell death (Meng and Zhang, 2013). A comparative transcriptomic analysis was performed using root tissues of equivalent developmental stages between apple replant disease-tolerant Geneva® 935 (G.935) and susceptible Bud 9 (B.9) apple rootstocks after Pythium ultimum inoculation. A mitogen-activated protein kinase kinase kinase 3-like (MDP0000187103) gene demonstrated specific suppression in B.9, whereas the same gene was consistently upregulated in G.935 (Zhu et al., 2019). MAPK1, which belongs to group A MAPKs, played an important role in the defense response to two citrus canker pathogens, Xanthomonas citri and X. aurantifolii, in citrus (de Oliveira et al., 2013). Increased expression of MAPK1 was correlated with a reduction in canker symptoms and a decrease in bacterial growth. Overexpression of MAPK1 in sweet orange resulted in higher transcript levels of defense-related genes and significant accumulation of hydrogen peroxide in response to X. citri infection (de Oliveira et al., 2013). Previous studies showed that SlMPK1, SlMPK2 and SlMPK3 played important roles in the systemin-mediated response to insect herbivory by regulating jasmonic acid (JA) biosynthesis and the expression of JA-dependent defense genes in tomato (Kandoth et al., 2007). SlMPK genes were also involved in the Cf-4-mediated HR that mediated plant resistance to Cladosporium fulvum (Stulemeijer et al., 2007). Furthermore, SlMPK2 and SlMPK3 participated in the defense against Xanthomonas campestris pv. vesicatoria (Mayrose et al., 2004; Melech-Bonfil and Sessa, 2011). SlMKK2 and SlMKK4, two tomato MAPKKs, were found to activate SlMPK1 and SlMPK2 in vitro and to induce cell death when overexpressed in tomato leaves, thus indicating a possible MAPK cascade in the Pto-mediated defense response against Pseudomonas syringae pv. tomato (Pedley and Martin, 2004). SlMAPKKKϵ is required for HR-induced cell death and disease resistance against gram-negative bacterial pathogens in tomato by mediating the SlMAPKKKϵ-MEK2-WIPK/SIPK cascade. Silencing of SlMAPKKKϵ compromised tomato resistance to X. campestris and P. syringae strains, resulting in the appearance of disease symptoms and enhanced bacterial growth (Melech-Bonfil and Sessa, 2010). The triple kinase SlMAPKKKα has been demonstrated to function as a positive regulator of Pto-mediated cell death in transgenic Nicotiana benthamiana lines (del Pozo et al., 2004). In addition, two MAPK cascades, MEK2-WIPK and MEK1-NTF6, were involved in Pto-mediated disease resistance in tomato by regulating the expression of NPR1, a key regulator of systemic acquired resistance (Ekengren et al., 2003). Powdery mildew caused by the biotrophic ascomycete Erysiphe necator Schw. adversely affects grapevine growth, berry quality and grape production (Fung et al., 2008). When the grape was infected by E. necator, a strong increase in the transcripts of most MAPKKK genes (VviMAPKKK46, VviMAPKKK50, VviMAPKKK31, VviMAPKKK32, VviMAPKKK39, VviMAPKKK38 and VviMAPKKK34) was caused, and in particular, VviMAPKKK50 showed the highest transcript abundance. A few MAPKKK genes (VviMAPKKK4, VviMAPKKK54 and VviMAPKKK51) were significantly downregulated by powdery mildew infection, especially VviMAPKKK54 (Wang et al., 2014). In cucumber, a Trichoderma-induced MAPK (TIPK) is involved in fungal defense responses (Shoresh et al., 2006). Furthermore, qRT-PCR analyses were used to examine the expression levels of the CsMAPK genes in response to Pseudoperonospora cubensis. The results showed that all the examined CsMAPKs were downregulated after P. cubensis treatment, and the expression levels of CsMAPKKs irregularly increased or decreased following P. cubensis treatment (Wang et al., 2015). MEKK1-MKK4/5-MPK3/6-WRKY22/29 and MKK9-mediated modules were involved in the defense response to Plasmodiophora brassicae in Brassica rapa. Three pair-wise genes (BraMKK4-1/4-2, BraMKK5-1/5-2, and BraMPK6-1/6-2) and BraMPKs (MPK3 and MPK4) were strongly and continuously activated in the roots of the CS BJN3-2 plants (Chinese cabbage near-isogenic lines (NILs) carrying the clubroot-susceptible allele of crbcrb) (Piao et al., 2018). In the modules of MKK9-MPK1/2-WRKY53, MKK9-MPK5 and MKK9-MPK9/19/20, the transcripts of BraMKK9 and BraMPK1, BraMPK2, BraMPK5, BraMPK9, BraMPK19 and BraMPK20 were increased in B. rapa after P. brassicae infection (Piao et al., 2018). MAPK cascades serve as convergence points downstream of multiple cell surface-resident receptors (Devendrakumar et al., 2018). The StMEK2-mediated MAPK cascade is involved in potato immunity dependent on StLRPK1, which is a putative leucine-rich repeat transmembrane receptor-like kinase (Wang H. et al., 2018). Silencing StMEK2 in StLRRK1-overexpressing N. benthamiana plants attenuates resistance to Phytophthora infestans (Wang H. et al., 2018). Based on the previous research, we noticed that MAPK cascades regulate the disease resistance of horticultural plants through multiple signal transduction pathways.

Conclusion

Mounting evidence indicates that the plant stress-resistance signal transduction process is a complex network system, and that the MAPK cascade is at the center of the network. Through phosphorylation and dephosphorylation, the MAPK cascade progressively amplifies and transmits a variety of stress signals to downstream response factors and causes a series of stress responses. Analyzing the members of the MAPK cascade and its mechanism are critical for improving horticultural crop resistance through molecular biology. Furthermore, deeper knowledge of the mechanism of MAPK cascades might facilitate the development of novel strategies to improve stress tolerance in horticultural plants (Šamajová et al., 2013). Genetic engineering techniques offer various applications for improvement of biotic and abiotic stress tolerance in horticultural crops (Nehanjali et al., 2017). MAPK cascades, as regulators of gene transcription with central roles in signal transduction, have already been employed to increase abiotic stress tolerance (Nehanjali et al., 2017).

Although a large number of studies in horticultural plants have shown that MAPK cascades are involved in multiple biological processes in responses to abiotic and biotic stresses, research on the function of MAPK genes or the mechanism by which the MAPK cascade regulates plant stress resistance is still limited. In addition, different stress stimuli can activate the same MAPK cascade genes. For example, in strawberry, drought and salt damage can both activate MAPK5 (Zhou et al., 2017). Temperature and pathogens can activate MAPK1-3 genes in tomato (Kandoth et al., 2007; Nie et al., 2013; Yu et al., 2015; Ding et al., 2018). The same stress stimuli can also activate different MAPK cascades; for example, P. brassicae can activate MKK9-MPK1/2-WRKY53, MKK9-MPK5 and MKK9-MPK9/19/20 in B. rapa (Piao et al., 2018). Therefore, how the same MAPK cascade is activated by different stresses and causes different responses and how different MAPK cascades coordinate the division of labor under the same stress remain to be further verified by researchers. Thus, further analyses of MAPK cascades and the molecular mechanisms of plant stress resistance have great significance for elucidating the entire stress-tolerance signal transduction pathway in horticultural plants.

Author Contributions

CheW and LL conceived the project. CheW and XH wrote the article. XH, ChuW, and HW performed the bioinformatics analysis.

Funding

This work was financially supported by the Natural Science Foundation of Shandong Province (Grant No. ZR2019BC015) and the Agricultural Scientific and Technological Innovation Project of Shandong Academy of Agricultural Sciences (Grant Nos. CXGC2018E22 and CXGC2018F03).

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

- Bai Y., Kissoudis C., Yan Z., Visser R. G. F., van der Linden G. (2018). Plant behaviour under combined stress: tomato responses to combined salinity and pathogen stress. Plant J. 93, 781–793. 10.1111/tpj.13800 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bi G., Zhou J. M. (2017). MAP kinase signaling pathways: a hub of plant-microbe interactions. Cell Host. Microbe 21, 270–273. 10.1016/j.chom.2017.02.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Çakır B., Kılıçkaya O. (2015). Mitogen-activated protein kinase cascades in Vitis vinifera. Front. Plant Sci. 6, 556–574. 10.3389/fpls.2015.00556 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colcombet J., Hirt H. (2008). Arabidopsis MAPKs: a complex signalling network involved in multiple biological processes. Biochem. J. 413, 217–226. 10.1042/BJ20080625 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Oliveira M. L., Silva C. C. L., Abe V. Y., Costa M. G., Cernadas R. A., Benedetti C. E. (2013). Increased resistance against citrus canker mediated by a citrus mitogen-activated protein kinase. Mol. Plant Microbe Interact. 26, 1190–1199. 10.1094/MPMI-04-13-0122-R [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- del Pozo O., Pedley K. F., Martin G. B. (2004). MAPKKKalpha is a positive regulator of cell death associated with both plant immunity and disease. EMBO J. 23, 3072–3082. 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600283 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Devendrakumar K. T., Li X., Zhang Y. (2018). MAP kinase signalling: interplays between plant PAMP- and effector-triggered immunity. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 75, 2981–2989. 10.1007/s00018-018-2839-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ding H., He J., Wu Y., Wu X., Ge C., Wang Y., et al. (2018). The tomato mitogen-activated protein kinase SlMPK1 Is as a negative regulator of the high-temperature stress response. Plant Physiol. 177, 633–651. 10.1104/pp.18.00067 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ekengren S. K., Liu Y., Schiff M., Dinesh-Kumar S. P., Martin G. B. (2003). Two MAPK cascades, NPR1, and TGA transcription factors play a role in Pto-mediated disease resistance in tomato. Plant J. 36, 905–917. 10.1046/j.1365-313X.2003.01944.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fung R. W., Gonzalo M., Fekete C., Kovacs L. G., He Y., Marsh E., et al. (2008). Powdery mildew induces defense-oriented reprogramming of the transcriptome in a susceptible but not in a resistant grapevine. Plant Physiol. 146, 236–249. 10.1104/pp.107.108712 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamel L. P., Nicole M. C., Sritubtim S., Morency M. J., Ellis M., Ehlting J., et al. (2006). Ancient signals: comparative genomics of plant MAPK and MAPKK gene families. Trends Plant Sci. 11, 192–198. 10.1016/j.tplants.2006.02.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hasegawa P. M., Bressan R. A., Zhu J. K., Bohnert H. J. (2000). Plant cellular and molecular responses to high salinity. Annu. Rev. Plant Physiol. Plant Mol. Biol. 51, 463–499. 10.1146/annurev.arplant.51.1.463 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang X. S., Luo T., Fu X. Z., Fan Q. J., Liu J. H. (2011). Cloning and molecular characterization of a mitogen-activated protein kinase gene from Poncirus trifoliata whose ectopic expression confers dehydration/drought tolerance in transgenic tobacco. J. Exp. Bot. 62, 5191–5206. 10.1093/jxb/err229 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang D., Ma M. N., Wang Q., Zhang M. X., Jing G. Q., Li C., et al. (2020). Arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi enhanced drought resistance in apple by regulating genes in the MAPK pathway. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 149, 245–255. 10.1016/j.plaphy.2020.02.020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ichimura K., Shinozaki K., Tena G., Sheen J., Henry Y., Champion A., et al. (2002). Mitogen-activated protein kinase cascades in plants: a new nomenclature. Trends Plant Sci. 7, 301–308. 10.1016/S1360-1385(02)02302-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ji T., Li S., Huang M., Di Q., Wang X., Wei M., et al. (2017). Overexpression of cucumber phospholipase D alpha gene (CsPLDalpha) in tobacco enhanced salinity stress tolerance by regulating Na(+)-K(+) balance and lipid peroxidation. Front. Plant Sci. 8, 499. 10.3389/fpls.2017.00499 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang M., Wen F., Cao J., Li P., She J., Chu Z. (2015). Genome-wide exploration of the molecular evolution and regulatory network of mitogen-activated protein kinase cascades upon multiple stresses in Brachypodium distachyon . BMC Genomics 16, 228. 10.1186/s12864-015-1452-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jonak C., Okresz L., Bogre L., Hirt H. (2002). Complexity, cross talk and integration of plant MAP kinase signalling. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 5, 415–424. 10.1016/S1369-5266(02)00285-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kandoth P. K., Ranf S., Pancholi S. S., Jayanty S., Walla M. D., Miller W., et al. (2007). Tomato MAPKs LeMPK1, LeMPK2, and LeMPK3 function in the systemin-mediated defense response against herbivorous insects. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 104, 12205–12210. 10.1073/pnas.0700344104 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kissoudis C., van de Wiel C., Visser R. G., van der Linden G. (2014). Enhancing crop resilience to combined abiotic and biotic stress through the dissection of physiological and molecular crosstalk. Front. Plant Sci. 5, 207. 10.3389/fpls.2014.00207 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Komis G., Šamajová O., Ovečka M., Šamaj J. (2018). Cell and developmental biology of plant mitogen-activated protein kinases. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 69, 237–265. 10.1146/annurev-arplant-042817-040314 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kong F., Wang J., Cheng L., Liu S., Wu J., Peng Z., et al. (2012). Genome-wide analysis of the mitogen-activated protein kinase gene family in Solanum lycopersicum . Gene 499, 108–120. 10.1016/j.gene.2012.01.048 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krasensky J., Jonak C. (2012). Drought, salt, and temperature stress-induced metabolic rearrangements and regulatory networks. J. Exp. Bot. 63, 1593–1608. 10.1093/jxb/err460 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Z., Zhen Z., Guo K., Harvey P., Li J., Yang H. (2015). MAPK-mediated enhanced expression of vacuolar H(+)-ATPase confers the improved adaption to NaCl stress in a halotolerate peppermint (Mentha piperita L.). Protoplasma 253, 553–569. 10.1007/s00709-015-0834-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Z., Wang W., Li G., Guo K., Harvey P., Chen Q., et al. (2016). MAPK-mediated regulation of growth and essential oil composition in a salt-tolerant peppermint (Mentha piperita L.) under NaCl stress. Protoplasma 253, 1541–1556. 10.1007/s00709-015-0915-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lohani N., Singh M. B., Bhalla P. L. (2020). High temperature susceptibility of sexual reproduction in crop plants. J. Exp. Bot. 71, 555–568. 10.1093/jxb/erz426 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mayrose M., Bonshtien A., Sessa G. (2004). LeMPK3 is a mitogen-activated protein kinase with dual specificity induced during tomato defense and wounding responses. J. Biol. Chem. 279, 14819–14827. 10.1074/jbc.M313388200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Melech-Bonfil S., Sessa G. (2010). Tomato MAPKKKepsilon is a positive regulator of cell-death signaling networks associated with plant immunity. Plant J. 64, 379–391. 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2010.04333.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Melech-Bonfil S., Sessa G. (2011). The SlMKK2 and SlMPK2 genes play a role in tomato disease resistance to Xanthomonas campestris pv. vesicatoria. Plant Signal. Behav. 6, 154–156. 10.4161/psb.6.1.14311 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meng X. Z., Zhang S. Q. (2013). MAPK cascades in plant disease resistance signaling. Annu. Rev. Phytopathol. 51, 245–266. 10.1146/annurev-phyto-082712-102314 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meng Y., Ma N., Zhang Q., You Q., Li N., Ali Khan M., et al. (2014). Precise spatio-temporal modulation of ACC synthase by MPK6 cascade mediates the response of rose flowers to rehydration. Plant J. 79, 941–950. 10.1111/tpj.12594 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morris P. (2001). MAP kinase signal transduction pathways in plants. New Phytol. 151, 67–89. 10.1046/j.1469-8137.2001.00167.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Munns R., Passioura J. B., Colmer T. D., Byrt C. S. (2020). Osmotic adjustment and energy limitations to plant growth in saline soil. New Phytol. 225, 1091–1096. 10.1111/nph.15862 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nehanjali P., Kunwar H. S., Deepika S., Lal S., Pankaj K., Nanjundan J., et al. (2017). Genetic engineering strategies for biotic and abiotic stress tolerance and quality enhancement in horticultural crops: a comprehensive review. 3 Biotech. 7 (4), 239. 10.1007/s13205-017-0870-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nejat N., Mantri N. (2017). Plant immune system: crosstalk between responses to biotic and abiotic stresses the missing link in understanding plant defence. Curr. Issues Mol. Biol. 23, 1–16. 10.21775/cimb.023.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nie W. F., Wang M. M., Xia X. J., Zhou Y. H., Shi K., Chen Z., et al. (2013). Silencing of tomato RBOH1 and MPK2 abolishes brassinosteroid-induced H2O2 generation and stress tolerance. Plant Cell Environ. 36, 789–803. 10.1111/pce.12014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Osthoff A., Rose P. D. D., Baldauf J. A., Piepho H. P., Hochholdinger F. (2019). Transcriptomic reprogramming of barley seminal roots by combined water deficit and salt stress. BMC Genomics 20, 325. 10.1186/s12864-019-5634-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pedley K. F., Martin G. B. (2004). Identification of MAPKs and their possible MAPK kinase activators involved in the Pto-mediated defense response of tomato. J. Biol. Chem. 279, 49229–49235. 10.1074/jbc.M410323200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peng L. X., Gu L. K., Zheng C. C., Li D. Q., Shu H. R. (2006). Expression of MaMAPK gene in seedlings of Malus L. under water stress. Acta Biochim. Biophys. Sin. 38, 281–286. 10.1093/abbs/38.4.281 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piao Y., Jin K., He Y., Liu J., Liu S., Li X., et al. (2018). Genome-wide identification and role of MKK and MPK gene families in clubroot resistance of Brassica rapa . PloS One 13, e0191015. 10.1371/journal.pone.0191015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quint M., Delker C., Franklin K. A., Wigge P. A., Halliday K. J., van Zanten M. (2016). Molecular and genetic control of plant thermomorphogenesis. Nat. Plants 2, 15190. 10.1038/nplants.2015.190 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramani S., Chelliah J. (2007). UV-B-induced signaling events leading to enhanced-production of catharanthine in Catharanthus roseus cell suspension cultures. BMC Plant Biol. 7, 61. 10.1186/1471-2229-7-61 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rao K. P., Richa T., Kumar K., Raghuram B., Sinha A. K. (2010). In silico analysis reveals 75 members of mitogen-activated protein kinase kinase kinase gene family in rice. DNA Res. 17, 139–153. 10.1093/dnares/dsq011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodriguez M. C., Petersen M., Mundy J. (2010). Mitogen-activated protein kinase signaling in plants. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 61, 621–649. 10.1146/annurev-arplant-042809-112252 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Šamajová O., Plíhal O., Al-Yousif M., Hirt H., Šamaj J. (2013). Improvement of stress tolerance in plants by genetic manipulation of Mitogen-activated protein kinases. Biotechnol. Adv. 31, 118–128. 10.1016/j.biotechadv.2011.12.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shi J., Zhang L., An H., Wu C., Guo X. (2011). GhMPK16, a novel stress-responsive group D MAPK gene from cotton, is involved in disease resistance and drought sensitivity. BMC Mol. Biol. 12, 22. 10.1186/1471-2199-12-22 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shoresh M., Gal-On A., Leibman D., Chet I. (2006). Characterization of a mitogen-activated protein kinase gene from cucumber required for trichoderma-conferred plant resistance. Plant Physiol. 142, 1169–1179. 10.1104/pp.106.082107 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shulaev V., Sargent D. J., Crowhurst R. N., Mockler T. C., Folkerts O., Delcher A. L., et al. (2011). The genome of woodland strawberry (Fragaria vesca). Nat. Genet. 43, 109–116. 10.1038/ng.740 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Song A., Hu Y., Ding L., Zhang X., Li P., Liu Y., et al. (2018). Comprehensive analysis of mitogen-activated protein kinase cascades in chrysanthemum. Peer J. 6, e5037. 10.7717/peerj.5037 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stulemeijer I. J. E., Stratmann J. W., Joosten M. H. A. J. (2007). Tomato mitogen-activated protein kinases LeMPK1, LeMPK2, and LeMPK3 are activated during the Cf-4/Avr4-induced hypersensitive response and have distinct phosphorylation specificities. Plant Physiol. 144, 1481–1494. 10.1104/pp.107.101063 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun M., Xu Y., Huang J., Jiang Z., Shu H., Wang H., et al. (2017). Global identification, classification, and expression analysis of MAPKKK genes: functional characterization of mdraf5 reveals evolution and drought-responsive profile in apple. Sci. Rep. 7, 13511. 10.1038/s41598-017-13627-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taj G., Agarwal P., Grant M., Kumar A. (2010). MAPK machinery in plants: recognition and response to different stresses through multiple signal transduction pathways. Plant Signal. Behav. 5, 1370–1378. 10.4161/psb.5.11.13020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vaahtera L., Schulz J., Hamann T. (2019). Cell wall integrity maintenance during plant development and interaction with the environment. Nat. Plants 5, 924–932. 10.1038/s41477-019-0502-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang G., Lovato A., Polverari A., Wang M., Liang Y. H., Ma Y. C., et al. (2014). Genome-wide identification and analysis of mitogen activated protein kinase kinase kinase gene family in grapevine (Vitis vinifera). BMC Plant Biol. 14, 219. 10.1186/s12870-014-0219-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang J., Pan C., Wang Y., Ye L., Wu J., Chen L., et al. (2015). Genome-wide identification of MAPK, MAPKK, and MAPKKK gene families and transcriptional profiling analysis during development and stress response in cucumber. BMC Genomics 16, 386. 10.1186/s12864-015-1621-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang L., Hu W., Tie W., Ding Z., Ding X., Liu Y., et al. (2017). The MAPKKK and MAPKK gene families in banana: identification, phylogeny and expression during development, ripening and abiotic stress. Sci. Rep. 7, 1159. 10.1038/s41598-017-01357-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang G., Wang T., Jia Z.-H., Xuan J.-P., Pan D. L., Guo Z. R., et al. (2018). Genome-wide bioinformatics analysis of MAPK gene family in Kiwifruit (Actinidia Chinensis). Int. J. Mol. Sci. 19, E2510. 10.3390/ijms19092510 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang H., Chen Y., Wu X., Long Z., Sun C., Wang H., et al. (2018). A potato STRUBBELIG-RECEPTOR FAMILY member, StLRPK1, associates with StSERK3A/BAK1 and activates immunity. J. Exp. Bot. 69, 5573–5586. 10.1093/jxb/ery310 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang C., Guo H., He X., Zhang S., Wang J., Wang L., et al. (2019). Scaffold protein GhMORG1 enhances the resistance of cotton to Fusarium oxysporum by facilitating the MKK6-MPK4 cascade. Plant Biotechnol. J. 18, 1421–1433. 10.1111/pbi.13307 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wei C., Liu X., Long D., Guo Q., Fang Y., Bian C., et al. (2014). Molecular cloning and expression analysis of mulberry MAPK gene family. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 77, 108–116. 10.1016/j.plaphy.2014.02.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weng C.-M., Lu J.-X., Wan H.-F., Wang S.-W., Wang Z., Lu K., et al. (2014). Over-expression of BnMAPK1 in Brassica napus enhances tolerance to drought stress. J. Integr. Agric. 13, 2407–2415. 10.1016/S2095-3119(13)60696-6 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wu J., Wang J., Pan C., Guan X., Wang Y., Liu S., et al. (2014). Genome-wide identification of MAPKK and MAPKKK gene families in tomato and transcriptional profiling analysis during development and stress response. PloS One 9, e103032. 10.1371/journal.pone.0103032 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu J., Zhang S. (2015). Mitogen-activated protein kinase cascades in signaling plant growth and development. Trends Plant Sci. 20, 56–64. 10.1016/j.tplants.2014.10.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamaguchi T., Blumwald E. (2005). Developing salt-tolerant crop plants: challenges and opportunities. Trends Plant Sci. 10, 615–620. 10.1016/j.tplants.2005.10.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamazaki T., Kawamura Y., Uemura M. (2009). Extracellular freezing-induced mechanical stress and surface area regulation on the plasma membrane in cold-acclimated plant cells. Plant Signal. Behav. 4, 231–233. 10.4161/psb.4.3.7911 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yan Y., Wang L., Ding Z., Tie W., Ding X., Zeng C., et al. (2016). Genome-wide identification and expression analysis of the mitogen-activated protein kinase gene family in cassava. Front. Plant Sci. 7, 1294. 10.3389/fpls.2016.01294 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yanagawa Y., Yoda H., Osaki K., Amano Y., Aono M., Seo S., et al. (2016). Mitogen-activated protein kinase 4-like carrying an MEY motif instead of a TXY motif is involved in ozone tolerance and regulation of stomatal closure in tobacco. J. Exp. Bot. 67, 3471–3479. 10.1093/jxb/erw173 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang Y., Guo Y. (2018). Elucidating the molecular mechanisms mediating plant salt-stress responses. New Phytol. 217, 523–539. 10.1111/nph.14920 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yin Y.-X., Guo W.-L., Zhang Y.-L., Ji J.-J., Xiao H.-J., Yan F., et al. (2014). Cloning and characterisation of a pepper aquaporin, CaAQP, which reduces chilling stress in transgenic tobacco plants. Plant Cell Tissue Organ Cult. 118, 431–444. 10.1007/s11240-014-0495-3 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Yu L., Yan J., Yang Y., Zhu W. (2015). Overexpression of tomato mitogen-activated protein kinase SlMPK3 in tobacco increases tolerance to low temperature stress. Plant Cell Tissue Organ Cult. 121, 21–34. 10.1007/s11240-014-0675-1 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zandalinas S. I., Fritschi F. B., Mittler R. (2019). Signal transduction networks during stress combination. J. Exp. Bot. 71, 1734–1741. 10.1093/jxb/erz486 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang S., Klessig D. F. (2001). MAPK cascades in plant defense signaling. Trends Plant Sci. 6, 520–527. 10.1016/S1360-1385(01)02103-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang S., Xu R., Luo X., Jiang Z., Shu H. (2013). Genome-wide identification and expression analysis of MAPK and MAPKK gene family in Malus domestica. Gene 531, 377–387. 10.1016/j.gene.2013.07.107 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang H., Li Y., Zhu J.-K. (2018). Developing naturally stress-resistant crops for a sustainable agriculture. Nat. Plants 4, 989–996. 10.1038/s41477-018-0309-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang M., Su J., Zhang Y., Xu J., Zhang S. (2018). Conveying endogenous and exogenous signals: MAPK cascades in plant growth and defense. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 45, 1–10. 10.1016/j.pbi.2018.04.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou J., Xia X. J., Zhou Y. H., Shi K., Chen Z., Yu J. Q. (2014). RBOH1-dependent H2O2 production and subsequent activation of MPK1/2 play an important role in acclimation-induced cross-tolerance in tomato. J. Exp. Bot. 65, 595–607. 10.1093/jxb/ert404 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou H., Ren S., Han Y., Zhang Q., Qin L., Xing Y. (2017). Identification and analysis of mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) cascades in Fragaria vesca . Int. J. Mol. Sci. 18, E1766. 10.3390/ijms18081766 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu Y., Shao J., Zhou Z., Davis R. E. (2019). Genotype-specific suppression of multiple defense pathways in apple root during infection by Pythium ultimum . Hortic. Res. 6, 10. 10.1038/s41438-018-0087-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu J. K. (2016). Abiotic stress signaling and responses in plants. Cell 167, 313–324. 10.1016/j.cell.2016.08.029 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]