Abstract

Lung cancer is the second most prevalent cancer. Non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) is the most common type of lung cancer. The low efficacy in current chemotherapies impels to find new alternatives to prevent or treat NSCLC. Rice bran oil is cytotoxic to A549 cells, a NSCLC cell line. Here, we identified 24-methylenecyloartanyl ferulate (24-mCAF) as the main component responsible for the cytotoxicity in A549 cells. An iTRAQ-based quantitative proteomics analysis revealed that 24-mCAF inhibits cell proliferation and activates cell death and apoptosis. 24-mCAF induces up-regulation of Myb binding protein 1A (MYBBP1A), a tumor suppressor that halts cancer progression. 24-mCAF inhibits the activity of AKT and Aurora B kinase, two Ser/Thr kinases involved in MYBBP1A regulation and that represent important targets in NSCLC. This study provides the first insight of the effect of 24-mCAF, the main component of rice bran oil, on A459 cells at the cellular and molecular levels.

Keywords: 24-methylenecyloartanyl ferulate, oryzanol, iTRAQ, non-small cell lung cancer, rice bran, quantitative proteomics

Graphical Abstract

INTRODUCTION

Lung cancer is the leading cause of cancer death in men and women. In 2018, lung and bronchus cancers are expected to cause approximately 25% of the cancer deaths in the United States. It is the second most commonly diagnosed cancer, accounting for 14% of the new cases and its prevalence keeps increasing worldwide each year.1

Non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) is the most common type of lung cancer, representing about 85% of the cases. The two most commonly mutated oncogenes in NSCLC are the epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) and Kirsten rat sarcoma (KRAS). Mutations in these two genes are mutually exclusive in NSCLC. When EGFR is overexpressed, it causes cells to grow in a faster and uncontrolled way. Erlotinib and gefitinib are epidermal growth factor receptor tyrosine kinase inhibitors (EGFR-TKIs) that block the signal from the overexpressed EGFR and that are used as a treatment for NSCLC. KRAS encodes a GTPase downstream of EGFR which signals through the PI3K/AKT/mTOR and STAT pathways involved in cell survival, and the RAS/RAF/MEK/MAPK pathway (also known as the MAPK/ERK pathway) involved in cell proliferation. KRAS mutations also result in uncontrolled growth. Cells presenting KRAS mutations are not sensitive to treatment with TKIs drugs such as erlotinib and gefitinib. General cancer treatments, such as surgery, chemotherapy and radiotherapy, are usually applied to NSCLC patients with KRAS mutations, since there is no targeted therapy available.2,3 KRAS is one of the most difficult drug targets and although some KRAS inhibitors have been reported in the past few years, the design of effective drugs remains a big challenge. KRAS mutations occur in approximately 33% of NSCLCs and the prognosis of this type of cancer is very poor. There is a great need for the development and implementation of a novel, effective and affordable treatment and prevention for this kind of cancer.4

Plant extracts have been widely used in traditional medicine for centuries. Nowadays, the use of bioactive phytochemicals and nutraceuticals is gaining attention due to their low cost, low toxicity, high tolerability and reported health benefits.5 Rice is the most important staple food. Rice bran oil is cytotoxic to A549 cells, a human adenocarcinoma epithelial cell line that carries KRAS mutations.6 γ-Oryzanol is a mixture of ferulate esters of triterpene alcohols and plant sterols that constitutes the major component of rice bran oil, representing about 4% of the crude extract. γ-Oryzanol has numerous benefits for human health, including cholesterol lowering capacity and anti-oxidant, anti-inflammatory and cytotoxic effects.7–10 The cytotoxic properties of γ-oryzanol have been tested in various cancer cell lines and animal models. In the prostate cancer cell lines DU145 and PC3, γ-oryzanol inhibits cell growth by down-regulating genes involved in oxidative stress protection and cell proliferation, like catalase, glutathione peroxidase and caveolin-1,11 activating apoptosis and blocking cell cycle progression at G2/M in PC3 cells and at G0/G1 in DU145 cells.12 In breast cancer cells, 24-methylenecyloartanyl ferulate (24-mCAF), the most abundant component of γ-oryzanol, promotes the expression of parvin-β. This protein is significantly down-regulated in breast tumors and breast cancer cell lines and is involved in anchorage-independent cell growth, cell survival and oncogenic transformation.13 However, the molecular mechanism of γ-oryzanol is not yet fully understood and its effect has not been studied for non-small cell lung cancer. Furthermore, the health benefits of γ-oryzanol have mostly only been studied as a mixture.

In the present work, we investigated the cytotoxicity of the four most abundant components of γ-oryzanol, 24-mCAF, cycloartenylferulate (CAF), campesterylferulate (CMF) and β-sitosterylferulate (β-SF) (Table 1),14 in A549 cells. We used an iTRAQ-based quantitative proteomics approach to identify the changes in the proteome of A549 cells and protein networks in response to γ-oryzanol. Enzymatic assays and Western blotting were used to verify our proteomics data and to identify the direct molecular targets of these compounds. This study provides the first insights into the molecular mechanisms of γ-oryzanol against NSCLC.

Table 1.

Composition of γ-oryzanol, modified from Kim et al.14

| Name | Abbreviation | % of total mass | Structure |

|---|---|---|---|

| 24-methylenecycloartanyl ferulate | 24-mCAF | 23–42 |  |

| Cycloartenyl ferulate | CAF | 10–41 | |

| Campesteryl ferulate | CMF | 8–20 | |

| β-sitosteryl ferulate | β-SF | 7–14 |

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Materials

24-mCAF, CAF, CMF and β-SF were available from previous studies.13,14 A549 human adenocarcinoma epithelial cells were obtained from the American Type Culture Collection (Manassas, VA). Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle Medium (DMEM), fetal bovine serum (FBS) and phosphate buffered saline (PBS) were purchased from Gibco (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA). Methylthiazol tetrazolium (MTT), triethylammonium bicarbonate (TEAB) buffer, bovine serum albumin (BSA) and dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) were obtained from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO) and culture flasks and plates from Corning (Corning, NY). Gel and buffer preparation reagents, polyvinylidene difluoride (PDVF) membranes, Mini Trans-Blot Electrophoretic Transfer Cell and alkaline phosphatase conjugate substrate kit were obtained from Bio-Rad (Hercules, CA). Antibodies were purchased from Invitrogen (Carlsbad, CA).

Cell culture

A549 cells were cultured in DMEM (high glucose, pyruvate) supplemented with 10% v/v FBS, 100 U/mL penicillin and 100 μg/mL streptomycin, which is referred to as “complete DMEM”. Cells were grown at 37 ºC and 5% CO2 in a fully humidified atmosphere.

Cell viability assay

Cells were seeded in 96-well plates at a concentration of 104 cells per well in 100 μL of complete DMEM and incubated for 24 h. They were starved with FBS-free medium for 24 h. 24-mCAF, CAF, CMF and β-SF were added at concentrations of 0, 10, 25, 50 and 75 μM. DMSO was used as a solvent carrier for γ-oryzanol; the final concentration of DMSO in each condition was 0.75% v/v. There were three biological replicates of each treatment. Cells were treated for 72 h and then incubated with 200 μL of 500 μg/mL MTT for 4 h. The supernatant was removed after centrifugation at 2,000 rpm for 10 min. An aliquot of 200 μL of DMSO was added and the optical density was then read at 550 nm (OD550).

Protein extraction

Cells were plated in complete DMEM in 75 cm2 culture flasks. When the cells reached approximately 50% confluence, they were starved with 0.05% v/v FBS for 24 h. The cells were treated with 50 μM 24-mCAF for 72 h and a control culture was treated with DMSO (the total amount of DMSO in both conditions was 0.5% v/v). Four biological replicates of each condition were used. After 72 h of treatment, the cells were harvested using a cell scraper and washed 3 times with PBS, centrifuging at 2,000 rpm for 10 min each time. Pellets were resuspended in 0.5 mL lysis buffer (10 mM Tris, pH 7.4, 100 mM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA, 2 mM Na3VO4, 1 mM EGTA, 1 mM NaF, 20 mM Na4P2O7, 1% v/v Triton X-100, 10% v/v glycerol, 0.1% v/v SDS, 0.5% v/v deoxycholate, and HaltTM protease inhibitor cocktail) and incubated for 30 min, mixing on a vortex every 10 min. Lysates were then sonicated in ice using an ultrasonic cell disruptor for 15 s, 3 times, waiting 2 min in between, and centrifuged for 10 min at 13,000 rpm and 4 ºC. The supernatant was transferred to a clean tube. Protein concentration was measured according to the Bradford method. Samples were diluted 1:8 and 4 μL were mixed with 200 μL of BioRad Protein Assay Dye diluted 1:5 in a 96-well microtiter plate. BSA was used as a calibrator. Absorbance was read at 595 nm.

Buffer exchange and sample concentration

In order to avoid interference of components from the lysis buffer with the iTRAQ labeling reaction, the buffer was exchanged to 1 M TEAB pH 8.5 using an Amicon Ultra-0.5 mL 3K centrifugal filter. The sample was concentrated to 100 μL.

Protein digestion

One hundred micrograms of each sample (4 controls and 4 treatments) were transferred to new tubes. The volume was adjusted to 20 μL with TEAB buffer. Proteins were denatured and reduced using 0.05% v/v SDS and 5 mM tris(2-carboxyethyl) phosphine and incubating at 60 ºC for 1 h. Cysteine residues were alkylated with methylmethanethiosulfate (10 mM) for 10 min at room temperature. Proteins were digested by adding 5 μg of sequencing-grade modified porcine trypsin resuspended in water and incubating at 37 ºC for 14 h.

iTRAQ-labeling

iTRAQ-8plex reagents were resuspended in 50 μL of isopropanol, added to the samples and allowed to react for 2 h at room temperature. Labels 113, 114, 115 and 119 were used on the control samples; labels 116, 117, 118 and 121 were used on the treated samples. After labeling, samples were pooled together and TEAB buffer was evaporated on a SpeedVac™, adding water (20 μL) to avoid dryness. The sample was then resuspended in 100 μL of SCX-A (7 mM KH2PO4, 30% acetonitrile, pH 2.65) and pH was adjusted with phosphoric acid to < 2.65.

Sample fractionation

Sample was fractionated using strong cation exchange chromatography (SCX) on an Agilent 1100 high performance liquid chromatograph (HPLC) system equipped with a diode array detector and with a polysulfoethylaspartamide column (2.1 × 200 mm, 5 μm beads, 200 Å pore size). A 100-μL aliquot of sample was injected. The flow rate was 0.2 mL/min. Elution gradient was 5 min of 100% SCX-A, 0–30% SCX-B (7 mM KH2PO4, 30% ACN, 500 Mm KCl, pH 2.65) in 10 min, 30–60% SCX-B in 20 min, 60–100% SCX-B in 5 min, 100% SCX-B for 5 min and 100% SCX-A for 15 min. One-minute fractions were collected from 5 to 60 min after the start of the gradient. Fraction volume was reduced to 100 μL in SpeedVac™ and fractions were desalted with 100 μL ZipTip C18 tips.

LC-MS/MS analysis

High-resolution mass spectrometric data were obtained on a Bruker maXis Impact nanoLC-QTOF-MS spectrometer (Bruker Daltonics, Billerica, ME) equipped with a CaptiveSpray source and a Magic C18AQ reversed-phase analytical column (0.1 x 150 mm, 3 μm particles and 200 Å pore size). Elution was with a gradient from 5% to 45% solvent B in 80 min at a flow rate of 500 nL/min. Solvent A was 0.1% v/v formic acid (FA), 5% v/v acetonitrile (ACN) and 95% v/v LC-MS-grade water. Solvent B was 0.1% v/v FA, 95% v/v ACN and 5% v/v water. Samples were measured in auto MS/MS mode and a mass range of m/z 50–2200 with a fixed cycle time of 3 s. Acquisition speed was 2 Hz in MS and 4 or 16 Hz in MS/MS mode depending on precursor intensity. Precursors were selected in the m/z 300–1221 and 1225–2200 range with charge states at 2–5 (exclusion of singly charge ions). Active exclusion was activated after 1 spectrum for 2 min. The collision energy was adjusted between 23–65 eV as a function of the m/z value. Three technical replicates per fraction were acquired.

Data analysis

Peak list files in mascot generic file (mgf) format were generated using Compass Data Analysis version 4.1 (Bruker Daltonics). The intensity threshold was set to 1,000 and no smooth process was applied. Peak lists were submitted to ProteinScape version 3.1 (Bruker Daltonics) for Mascot search. Swissprot was used as a database. The peptide and MS/MS tolerance were set to 50 ppm and 0.06 Da, respectively. Trypsin was the cleaving enzyme and two missed cleavages were allowed. Methylthio (C) and iTRAQ-8plex (K and N-term) were added as fixed modifications. Oxidation (M) and iTRAQ-8plex (Y) were added as variable modifications. Proteins with a score below 20 and peptides with a score below 15 were discarded.

Quantification ratios were obtained using WARP-LC (Bruker Daltonics). Biological and technical replicates were used to set up a cutoff ratio that can determine which proteins were upand down-regulated, and also to identify proteins that were consistently expressed in the control samples. All ratio possibilities between the 4 controls were calculated (114/113, 115/113, 119/113, 115/114, 119/114 and 115/119) and they were normalized dividing by the overall median. The median of normalized ratios was calculated for each protein and it was used to set up a cutoff of 1.25 (Supporting information Figure S-1). Proteins inside this range were considered to be consistently expressed in the control samples; proteins outside of this range were considered to have different expression in the different control samples and were not accepted for further analysis.

All combinations of treatment/control ratios were calculated for the accepted proteins (116/113, 117/113, 118/113, 121/113, 116/114, 117/114, 118/114, 121/114, 116/115, 117/115, 118/115, 121/115, 116/119, 117/119, 118/119 and 121/119). Ratios were normalized dividing by the overall median. The median of all normalized ratios was calculated for each protein and the 1.25-fold cutoff was applied to determine what proteins were up- and down-regulated (Supporting information Figure S-2). Data were analyzed through the use of Ingenuity Pathway Analysis (IPA) (Qiagen, Redwood City, CA).

Western bolt

Equal amounts of cell lysate (40 μg) were separated by sodium dodecyl sulfate polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) with an 8% v/v polyacrilamide gel. Three independent experiments using three different biological replicates of both control and treated samples were carried out. Proteins were transferred to polyvinylidene difluoride (PVDF) membranes (0.2 μm pore size) by electroblotting for 90 min at 100 V using Mini Trans-Blot Electrophoretic Transfer Cell. Transfer buffer was 25 mM Tris, 192 mM glycine, 20% v/v ethanol. Membranes were blocked with 3% w/v BSA in Tris-buffered saline, 0.1% v/v Tween 20 (TBST) buffer for 1 h at room temperature. Primary antibodies were rabbit anti-MYBBP1A and mouse anti-β-actin diluted at 1:1000 in 1% w/v BSA in TBST. MYBBP1A (148 kDa) was the target protein and β-actin (42 kDa) was used as a loading control. Membrane was incubated with primary antibodies overnight at 4 ºC. Secondary antibodies were alkaline phosphatase conjugated anti-rabbit/anti-mouse IgG diluted at 1:3000 in 1% w/v BSA in TBST buffer. Membranes were washed 3 times for 5 min with TBST buffer, incubated with corresponding secondary antibody for 1 h at room temperature and washed again 3 times for 5 min with TBST buffer. Alkaline phosphatase conjugate substrate kit was used to measure alkaline phosphatase activity. Membranes were conjugated with substrate for 20 min, washed for 10 min in deionized water, dried for 5 min in an incubator at 30 ºC and scanned. ImageJ (National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD) was used to measure band density. The density of the MYBBP1A bands was normalized dividing by the density of the β-actin bands for each sample. Normalized MYBBP1A densities were used to calculate the treated/control expression ratio. The average ratio for the three experimental replicates and the standard deviation of the mean (SEM) were calculated and compared to the ratio obtained with iTRAQ.

Kinase Luminescent Assay

Kinase inhibition was assessed with the ADP-Glo Kinase Assay following a procedure previously described.15,16 For screening, a kinase at a concentration of 5 ng/μL was assayed in a reaction mixture containing 50 ng/μL substrate, 40 mM Tris, pH 7.5, 20 mM MgCl2, 0.1 mg/mL BSA, 50 μM dithiothreitol, 25 μM ATP, 50 μM 24m-CAF or 5% DMSO as vehicle. The reaction mixture was incubated for 1 h at room temperature followed by the addition of the ADP-Glo reagents according to the manufacturer’s protocol. The kinase inhibitor staurosporine was used as a reference at 1 μM. Each data point was collected in quadruplicate of two independent experiments.

RESULTS

γ-Oryzanol inhibits cell viability of A549 cells

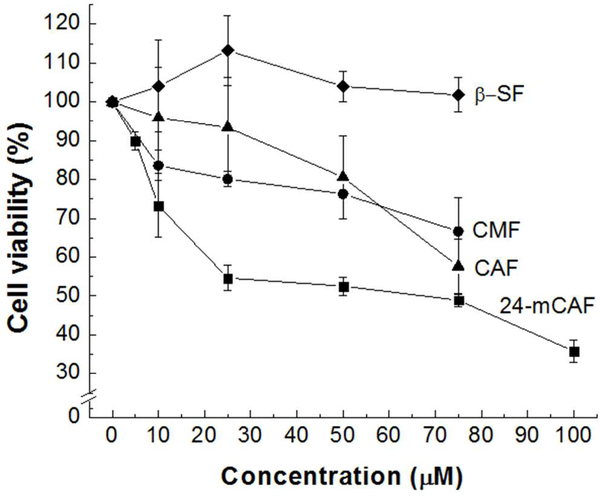

We tested the cytotoxicity of each of the four major components in γ-oryzanol (24-mCAF, CAF, CMF and β-SF) on A549 NSCLC cells using an MTT assay. 24-mCAF, CAF and CMF showed significant inhibition of cell viability, whereas β-SF did not affect it (Figure 1). Among the four γ-oryzanols, 24-mCAF showed the strongest inhibition with an IC50 < 75 μM.

Figure 1.

Effect of γ-oryzanols (24-mCAF, CAF, CMF and β-SF) on cell viability of A549 cells. Cell viability is represented as a percentage of the control. Error bars represent the standard deviation of the mean (SEM). Sample size (n) = 3.

Quantitative analysis of the changes in protein expression in response to 24-mCAF

To better understand the mechanism of action of 24-mCAF on A549 cells, we performed an iTRAQ-based quantitative proteomic analysis and compared protein levels of untreated A549 cells to cells treated with 50 μM of 24-mCAF for 72 h. Four biological replicates of each condition were analyzed, each of them marked with a different iTRAQ label. We identified a total of 484 proteins, from which 432 were consistently expressed in the control samples and were accepted for analysis (Supporting information Figure S-1). A 1.25-fold cutoff was established according to the procedure described by Unwin et al.17 This cutoff was used to determine which proteins were differentially expressed. Distribution of the ratios is shown in Figure S-2. A total of 58 differentially expressed proteins were identified, 29 of which were up-regulated and 29 down-regulated (Supporting information Table S-1).

Differentially expressed proteins were subjected to IPA. The results revealed that 32 of them were cytoplasmic proteins, 18 were nuclear proteins, six were plasma membrane proteins and two were extracellular proteins. Twenty of these proteins were enzymes, nine were transcription factors and five were transporters (data not shown). Cellular function analyses indicated that cell death, apoptosis and cell proliferation were the most affected cellular processes by 24-mCAF (Table 2). Cell death and apoptosis were activated, whereas cell proliferation was inactivated. Eighteen of the differentially expressed proteins contributed to the activation of cell death, 14 to the activation of apoptosis and 11 to the inactivation of cell proliferation.

Table 2.

Most affected cellular functions by 24-mCAF

| Cellular functions | Activation State | P-value overlap1 | z-score2 | Contributing proteins3 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cell death | Activated | 1.67E-07 | 1.477 | 18 | ↓ATP1A2, ↓EIF3E, ↑FH, ↓GLS, ↓ITGA3, ↑MYBBP1A, ↓NAA15, ↓PSMC6, ↓RPL11, ↓SF3B1, ↓SLC25A10, ↑SMARCC1, ↓SNRPB, ↓TGM2, ↓TOP2B, ↓TPD52, ↓UBQLN1, ↓VAPB |

| Apoptosis | Activated | 9.32E-05 | 2.062 | 14 | ↓ATP1A2, ↑FH, ↓GLS, ↑HEXB, ↓ITGA3, ↑MDHl, ↑MYBBP1A, ↓NAA15, ↓SF3B1, ↓SLC25A10, ↑SMARCC1, ↑TMEM109, ↓TOP2B, ↓TPD52, ↓UBQLNl |

| Cell proliferation | Inactivated | 1.27E02 | −0.908 | 11 | ↓CA12, ↓EIF3E, ↓GLS, ↑GPI, ↓ITGA3, ↑MYBBP1A, ↓PTGES, ↑SEC23A, ↓SF3B1, ↓TGM2, ↓TPD52, ↑WARS |

Probability that the detected differentially expressed proteins overlap with the proteins involved in a specific cellular function by chance

Score calculated by IPA that quantifies the activation or inactivation of a cellular function. A z-score >1 is considered to be activated function and a z-score <−1 is considered to be inactivated.

Numbers indicate the amount of detected differentially expressed proteins involved in this function; arrows indicate up- (↑) or down-regulation (↓); letter code indicates the protein accession number

MYBBP1A is up-regulated by γ-oryzanol

Several differentially expressed proteins relevant to oncology were downstream of MYBBP1A, a transcriptional regulator that was up-regulated by 24-mCAF. MYBBP1A acts as a tumor suppressor by binding to several proteins involved in cancer progression. These proteins include p53, NFκB and sirtuin 6 (SIRT6). p53 is a transcription factor well known for its role in cell cycle control; its interaction with MYBBP1A allows its activation and induces cell cycle arrest and apoptosis. NFκB controls inflammatory processes and cell survival; MYBBP1A inhibits the transcription of NFκB, leading to inhibition of these processes. SIRT6 is a deacylase known to act as a metastasis-inducing protein in NSCLC. It inactivates a series of transcription factors that control the expression of a large number of proteins, including the tumor protein D52 (TPD52), NADH dehydrogenase ubiquinone 1 beta subcomplex subunit 9 (NDUFB9), fumarate hydratase (FH), malate dehydrogenase (MDH1), vesicle-trafficking protein SEC22B and SEC23A. These 8 proteins, which are downstream MYBBP1A, were differentially expressed after treatment with 24-mCAF and their up- or down-regulation is consistent with MYBBP1A up-regulation. TPD52 and SEC22B are typically over-expressed in NSCLC; they act inducing cell migration and invasion and they were down-regulated by 24-mCAF. NDUFB9, FH and SEC23A are tumor suppressive proteins involved in the control of cell invasion which down-regulation is associated with metastasis. These proteins were up-regulated by 24-mCAF. Our results suggest that the upregulation of MYBBP1A contributes to stop cancer progression via its interaction with proteins directly involved in cancer related processes, such as p53 and NFκB, and through the inactivation of SIRT6, which leads to the up- or down-regulation of TPD52, NDUFB9, FH, MDH1, SEC22B and SEC23A and UGGT1 (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Physiological consequences of MYBBP1A up-regulation by 24-mCAF in A549 cells. Induced cellular functions are shown in orange; repressed cellular functions are shown in blue. Up-regulated proteins are shown in red, down-regulated proteins in green. Colored numbers underneath protein names show iTRAQ ratios; ratios >1 indicate up-regulation, ratios <1 indicate down-regulation. Arrow-headed lines indicate activation; bar-headed lines indicate inhibition; solid lines designate direct relationships and dashed lines designate indirect relationships.

Up-regulation of MYBBP1A was verified by Western blot (Figure 3A). Band density of MYBBP1A was normalized with that of β-actin. MYBBP1A was significantly over-expressed in the sample treated with 24-mCAF compared to the control sample. These results supported the ones obtained with iTRAQ (Figure 3B).

Figure 3.

(A) Western blot analysis of the differential expression of MYBBP1A in A549 cells treated and non-treated with 24-mCAF. (B) Comparison of the expression ratios obtained with iTRAQ and Western blot. Western blot expression ratios are expressed as the average ± standard deviation of the mean (SEM). Sample size (n) = 3.

γ-Oryzanol inhibits Aurora B Kinase and AKT activity

We showed that 24-mCAF stops cancer progression through up-regulation of MYBBP1A, but the molecular mechanism that leads to this up-regulation as well as the direct targets of the compound remains unknown. Regulation of MYBBP1A is poorly understood. George et al.18 reported that high levels of phosphorylated (active) AKT are associated with low levels of MYBBP1A. AKT is the major effector of the phosphoinositide 3-kinase (PI3K) pathway, involved in cell survival, and it is typically hyper-activated in non-small cell lung cancer, as well as in other types of cancer. Inactivation of AKT would lead to up-regulation of MYBBP1A. MYBBP1A is also known to be a substrate of Aurora B kinase, which is an essential regulator of mitosis that is also frequently over-activated in non-small cell lung cancer.19 Aurora B kinase phosphorylates MYBBP1A, but the effect of this modification on the stability and function of MYBBP1A is not yet known. We tested the effect of 24-mCAF on selected 32 cytoplasmic kinases from the CGMC, AGC and CK1 families relevant to cancer processes, including AKT and Aurora B kinase (Figure 4). Our results showed that the kinase activity of Aurora B kinase and AKT were significantly inhibited (69.8% and 58.7%, respectively) upon treatment of 24-mCAF. These results suggest that 24-mCAF directly inhibits AKT and Aurora B kinase, which may in part induce downstream MYBBP1A upregulation in cells. In addition, these two kinases are involved in numerous cancer related processes and are important targets in cancer therapy. Our proteomics results support inhibition of AKT and Aurora B kinase by 24-mCAF. AKT regulates the hypoxia inducible factor (HIF), an essential transcriptional activator of genes involved in cell migration and invasion. In this study, we have detected up-regulation of FH, which leads to degradation of HIF, reducing metastasis.20,21 Moreover, AKT inactivation has been related to protein-glutamine gamma-glutamyltransferase 2 (TGM2) and TPD52 down-regulation. TGM2 is involved in inflammatory processes and TPD52 in cell migration and invasion.22,23 Both proteins were down-regulated by 24-mCAF (Table 2 and Figure 2). AKT is also thought to promote vesicle-trafficking between the ER and the Golgi.24 Here, we show that the vesicle-trafficking proteins SEC22B is down-regulated by 24-mCAF. A proposed mechanism of action for 24-mCAF is depicted in Figure 5.

Figure 4.

Enzymatic activities for kinases from the CGMC, AGC and CK1 families treated with 50 μM 24-mCAF dissolved in DMSO. N=4. Data are mean ± SEM. ****p < 0.0001.

Figure 5.

Proposed mechanism of action of 24-mCAF in A549 cells.

DISCUSSION

NSCLC is the most common type of cancer. Its increasing prevalence and the lack of effective treatments make the need to find new alternatives to prevent or treat this disease a matter of great importance. γ-Oryzanol is a mixture of steryl ferulates found in rice and other cereal grains that has numerous health benefits. The cytotoxic effects of γ-oryzanol as a mixture have previously been reported for some types of cancer, but not for NSCLC. In addition, the pure components of?-oryzanol have not been studied on cytotoxicity in cancer cells. We tested the effect of the most abundant components in the γ-oryzanol mixture (24-mCAF, CAF, CMF and β-SF) against A549 cells. 24-mCAF, CAF and CMF significantly inhibited cell proliferation, whereas β-SF did not (Figure 1). Among all compounds, 24-mCAF showed the highest inhibitory effect with an IC50 < 75 μM. This concentration is around 100 times lower than the concentrations reported for prostate cancer cell lines by Klongpityapong et al.11 This is probably due to the fact that the cytotoxicity of?-oryzanol had previously been studied only as a mixture. Here, we showed that pure 24-mCAF is the most potent component in the γ-oryzanol mixture responsible for the cytotoxic activity in A549 cancer cells. In contrast, Sakai et al.25 reported that treatment of γ-oryzanol in bovine aortic endothelial cells (BAECs) did not affect cell viability, indicating that γ-oryzanol is not toxic to healthy systems.

To better understand the effect of?-oryzanol on NSCLC, we analyzed the changes caused by 24-mCAF in the proteome of A549 cells. The most affected cellular processes by 24-mCAF were cell death, apoptosis, and cell proliferation (Table 2). Cell death and apoptosis were activated, whereas cell proliferation was inhibited. These findings support the cytotoxicity of γ-oryzanol in A549 cells and also correlate well with the previous studies that γ-oryzanol induced apoptosis and blocked cell cycle progression in prostate cancer cells.12

MYBBP1A is a transcriptional regulator that acts as a tumor suppressor and it is up-regulated by 24-mCAF. It connects ribosome biogenesis to regulation of cell cycle progression and cell proliferation.26 MYBBP1A is mostly present in the nucleolus, but when nucleolar disruption occurs and ribosome biogenesis is inhibited, it is translocated to the nucleoplasm, where it binds p53 and facilitates its tetramerization and activation, inducing cell cycle arrest and apoptosis.27 MYBBP1A is also a repressor of NFκB, which leads to inhibition of inflammatory processes.28 Inhibition of NFκB by γ-oryzanol was previously reported by Sakai et al.25 Another interaction partner of MYBBP1A is SRIT6. This protein plays multiple complex roles in cancer; depending on the type of cancer, it can act as a tumor suppressor or as a cancer-inducing protein. In NSCLC, SIRT6 is up-regulated. Knockdown of SIRT6 in A459 cells reduces cell migration and invasion, whereas its over-expression induces metastasis.29 SIRT6 promotes the expression of COX-2, a tumor-inducing protein that is involved in cell proliferation and survival.30 Upregulation of MYBBP1A produces inactivation of SIRT6, which leads to down-regulation of COX-2 and consequently to the inhibition of cell proliferation.

SIRT6 indirectly regulates the expression of numerous proteins, including TPD52, NDUFB9, FH, MDH1, SEC22B and SEC23A (IPA, www.qiagen.com/ingenuity). These eight proteins were differentially expressed in this study, and their expression direction is consistent with SITR6 inactivation. TPD52 and SEC22B were down-regulated by 24-mCAF, whereas NDUFB9, FH, MDH1 and SEC23A were up-regulated. The differential expression of most of these proteins correlates with cancer inhibition. TPD52 is over-expressed in lung adenocarcioma; its over-expression enhances cancer cell aggressiveness and contributes to several oncogenic pathways. Knockdown of TPD52 significantly suppresses cancer cell migration and invasion.31 SEC22B is a vesicle-trafficking protein that is involved in lipid metabolism at contact sites between the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) and the plasma membrane. Lipid production and transfer at these membrane contact sites are essential for membrane expansion, which is important in cell migration.32 Okayama et al.33 carried out a proteomic study to identify proteins related to prognosis in lung adenocarcinoma and found that SEC22B was over-expressed in patients with poor prognosis. NDUFB9 is an accessory subunit of the mitochondrial membrane respiratory chain NADH dehydrogenase (Complex I) and it is down-regulated in highly metastatic cancer cells. Down-regulation of NDUFB9 produces complex I deficiency, which disturbs electron transfer and leads to a disruption of the NAD+/NADH balance. Together with other processes, this unbalance induces cell migration and invasion.34 FH converts fumarate to malate in the tricarboxylic acid cycle. In A549 cells, FH is significantly under-expressed at both mRNA and protein levels compared with non-cancer cells. Down-regulation of FH increases the amount of intracellular fumaric acid, which inhibits the hydroxylation of the hypoxia-inducible factor (HIF). If HIF cannot be hydroxylated, it cannot be degraded by the proteasome. HIF regulates the expression of several genes like vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF), erythropoietin (EPO), platelet derived growth factor (PDGF), EGFR, glucose transporter protein 1 (GLUT-1), and transforming growth factor-alpha (TGF-α). These genes are involved in maintaining the energy metabolism of tumor cells, promoting tumor angiogenesis, invasion, and metastasis.35 MDH1 catalyzes the conversion of malate to oxaloacetate in the cytoplasm and it has also been reported to be a transcriptional co-activator of p53. It is stabilized and activated by translocating to the nucleus and binding to p53-responsive elements in the promoter of downstream genes. When MDH1 is down-regulated, binding of acetylated p53 is significantly reduced, which results in loss of p53-mediated cell cycle arrest and apoptosis.36 SEC23A is essential for the secretion of components of the extracellular membrane, such as collagen and cartilage oligomeric matrix protein.37 It is also important in the secretion of metastasis suppressive proteins, like Igfbp4 and Tinagl1.37 Knockdown of SEC23A increases cell proliferation, migration and invasion.38 Taken together, the present study implicated that multiple mechanisms could be involved in up-regulation of MYBBP1A by 24-mCAF against cancer progression (Figure 2).

Nevertheless, the targets that directly interact with 24-mCAF remained so far unknown. In order to identify the direct target, we tested the inhibitory effect of 24-mCAF on AKT and Aurora B kinases, both involved in MYBBP1A regulation. Our results indicated that both enzymes, which play an important role in several types of cancer, are directly and selectively inhibited by 24-mCAF (Figure 4). Aurora B kinase is a member of the Aurora Ser/Thr family that represents a well-known target for cancer therapy. It is a regulator of mitosis that participates in controlling the assembly of the nucleolar RNA-processing machinery, which controls the translocation of MYBBP1A from the nucleolus to the nucleus.19,26 Aurora B kinase is an important KRAS target in NSCLC and its inhibition is an attractive approach to be explored for KRAS-induced lung cancer therapy.39 AKT is also a Ser/Thr kinase that regulates multiple biological processes, including cell survival and proliferation. Hyper-activated AKT is very frequently found in cancers and it causes uncontrolled cell cycle progression. AKT promotes cell survival by phosphorylating a large number of substrates. MYBBP1A has not been reported to be a substrate of AKT, but overactive AKT are associated with low levels of MYBBP1A.18 AKT is a validated target for drug development, but no AKT inhibitor has yet been approved for oncogenic use.

This study substantiates the cytotoxic effect of γ-oryzanol and sheds light on its mechanism of action against NSCLC (Figure 5). Blocking KRAS signaling by targeting downstream effectors has been challenging, since KRAS regulates multiple effectors that contribute to oncogenesis. Here, we show that 24-mCAF intervenes multiple pathways in cancer processes and targets at least two of these effectors (Aurora B and AKT). Inhibition of Aurora B and AKT could in part lead to MYBBP1A upregulation that represses cell proliferation and induces cell death and apoptosis. While additional knowledge is necessary to understand the molecular mechanisms, we confer the therapeutic potential of 24-mCAF for NSCLC treatment and prevention.

Supplementary Material

Figure S-1. Plot of the logarithm of the median of all possible control/control ratios against the Mascot score.

Figure S-2. Plot of the logarithm of the median of all possible treated/control ratios against Mascot score.

Table S-1. Protein identification and iTRAQ-based relative quantification.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

We thank Dr. Nicholas G. James for providing the tissue culture facility necessary to carry out this study, and Dr. Margaret R. Baker and Dr. Camila A. Ortega Ramírez for helpful discussions.

FUNDING SOURCES

This work was supported in part by the National Institutes of Health Research Centers in Minority Institutions Program (8G12 MD007601–29) and the Korean Rural Development Administration (Grant no. PJ011884 and PJ01178704). SD was a Fulbright scholar.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest Disclosure

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

REFERENCES

- (1).American Cancer Society. Cancer Facts and Figures 2018. [Google Scholar]

- (2).Krypuy M; Newnham GM; Thomas DM; Conron M; Dobrovic A High resolution melting analysis for the rapid and sensitive detection of mutations in clinical samples: KRAS codon 12 and 13 mutations in non-small cell lung cancer. BMC Cancer 2006, 6, 295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (3).Riely GJ; Marks J; Pao W KRAS Mutations in Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer. Proc. Am. Thorac. Soc 2009, 6 (2), 201–205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (4).Ostrem JM; Peters U; Sos ML; Wells J. a; Shokat KM K-Ras(G12C) inhibitors allosterically control GTP affinity and effector interactions. Nature 2013, 503 (7477), 548–551. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (5).Pal HC; Hunt KM; Diamond A;Elmets CA;Afaq F Phytochemicalsforthe Management of Melanoma. Mini Rev. Med. Chem 2016, 16 (12), 953–979. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (6).Dapar MLG;Garzon JF;Demayo CG Cytotoxic activityandAntioxidant Potentials of hexane and Methanol extracts of IR64 Rice bran against Human Lung ( A549) and Colon ( HCT116 ) Carcinomas. Int. Res. J. Biol. Sci 2013, 2 (5), 19–23. [Google Scholar]

- (7).Patel M;Naik SN Gamma-oryzanolfromricebranoil- Areview. J.Sci.Ind.Res. (India) 2004, 63 (7), 569–578. [Google Scholar]

- (8).Wang L;Lin Q; Yang T;Liang Y;Nie Y; Luo Y; Shen J; Fu X;Tang Y;Luo F Oryzanol Modifies High Fat Diet-Induced Obesity, Liver Gene Expression Profile, and Inflammation Response in Mice. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2017, 65 (38), 8374–8385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (9).Yu S;Nehus ZT;Badger TM;Fang N QuantificationofvitaminEand?-oryzanol components in rice germ and bran. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2007, 55 (18), 7308–7313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (10).Luo HF; Li Q; Yu S; Badger TM; Fang N Cytotoxic hydroxylated triterpene alcohol ferulates from rice bran. J. Nat. Prod. 2005, 68 (1), 94–97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (11).Klongpityapong P; Supabphol R; Supabphol A Antioxidant effects of gamma-oryzanol on human prostate cancer cells. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev 2013, 14 (9), 5421–5425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (12).Hirsch GE; Parisi MM; Martins LAM; Andrade CMB; Barbé-Tuana FM; Guma FTCR Gamma-oryzanol reduces caveolin-1 and PCGEM1 expression, markers of aggressiveness in prostate cancer cell lines. Prostate 2015, 75 (8), 783–797. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (13).Kim HW; Lim EJ; Jang HH; Cui X; Kang DR; Lee SH; Kim HR; Choe JS; Yang YM; Kim JB; et al. 24-Methylenecycloartanyl ferulate, a major compound of?-oryzanol, promotes parvin-beta expression through an interaction with peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-gamma 2 in human breast cancer cells. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2015, 468 (4), 574–579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (14).Kim HW; Kim JB; Shanmugavelan P; Kim SN; Cho YS; Kim HR; Lee J-T; Jeon W-T; Lee DJ Evaluation of?-oryzanol content and composition from the grains of pigmented rice-germplasms by LC-DAD-ESI/MS. BMC Res. Notes 2013, 6 (1), 149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (15).Zegzouti H; Zdanovskaia M; Hsiao K; Goueli SA ADP-Glo: A bioluminescent and homogeneous ADP monitoring assay for kinases. Assay Drug Dev. Technol. 2009, 7, 560–572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (16).Liang Z; Zhang B; Su WW; Williams PG; Li QX C-Glycosylflavones Alleviate Tau Phosphorylation and Amyloid Neurotoxicity through GSK3ß Inhibition. ACS Chem. Neurosci 2016, 7 (7), 912–923. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (17).Unwin RD; Griffiths JR; Whetton AD Simultaneous analysis of relative protein expression levels across multiple samples using iTRAQ isobaric tags with 2D nano LC-MS/MS. Nat. Protoc. 2010, 5 (9), 1574–1582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (18).George B; Horn D; Bayo P; Zaoui K; Flechtenmacher C; Grabe N; Plinkert P; Krizhanovsky V; Hess J Regulation and function of Myb-binding protein 1A (MYBBP1A) in cellular senescence and pathogenesis of head and neck cancer. Cancer Lett. 2015, 358 (2), 191–199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (19).Perrera C; Colombo R; Valsasina B; Carpinelli P; Troiani S; Modugno M; Gianellini L; Cappella P; Isacchi A; Moll J; et al. Identification of Myb-binding Protein 1A ( MYBBP1A ) as a Novel Substrate for Aurora B Kinase. J. Biol. Chem. 2010, 285 (16), 11775–11785. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (20).Agani F; Jiang B-H Oxygen-independent Regulation of HIF-1: Novel Involvement of PI3K/ AKT/mTOR Pathway in Cancer. Curr. Cancer Drug Targets 2013, 13 (3), 245–251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (21).King A; Selak MA; Gottlieb E Succinate dehydrogenase and fumarate hydratase: Linking mitochondrial dysfunction and cancer. Oncogene 2006, 25 (34), 4675–4682. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (22).Lai T; Greenberg C TGM2 and implications for human disease: role of alternative splicing. Front. Biosci. 2013, 18 (2), 504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (23).Ummanni R; Teller S; Junker H; Zimmermann U; Venz S; Scharf C; Giebel J; Walther R Altered expression of tumor protein D52 regulates apoptosis and migration of prostate cancer cells. FEBS J. 2008, 275 (22), 5703–5713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (24).Sharpe LJ; Luu W; Brown AJ Akt phosphorylates Sec24: New clues into the regulation of ER-to-Golgi trafficking. Traffic 2011, 12 (1), 19–27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (25).Sakai S; Murata T; Tsubosaka Y; Ushio H; Hori M; Ozaki H gamma-Oryzanol reduces adhesion molecule expression in vascular endothelial cells via suppression of nuclear factor-kappaB activation. J Agric Food Chem 2012, 60 (13), 3367–3372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (26).Yamauchi T; Keough RA; Gonda TJ; Ishii S Ribosomal stress induces processing of Mybbp1a and its translocation from the nucleolus to the nucleoplasm. Genes to Cells 2008, 13 (1), 27–39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (27).Ono W; Hayashi Y; Yokoyama W; Kuroda T; Kishimoto H; Ito I; Kimura K; Akaogi K; Waku T; Yanagisawa J The nucleolar protein Myb-binding protein 1A (MYBBP1A) enhances p53 tetramerization and acetylation in response to nucleolar disruption. J. Biol. Chem. 2014, 289 (8), 4928–4940. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (28).Owen H; Elser M; Cheung E; Gersbach M; Kraus W; Hottiger M MYBBP1A is a novel repressor of NFκB. J. Mol. Biol. 2007, 366, 725–736. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (29).Bai L; Lin G; Sun L; Liu Y; Huang X; Cao C; Guo Y; Xie C Upregulation of SIRT6 predicts poor prognosis and promotes metastasis of non-small cell lung cancer via the ERK1 / 2 / MMP9 pathway. Oncotarget 2016, 7 (26), 40377–40386. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (30).Ming M; Han W; Zhao B; Sundaresan N; Deng C; Gupta M; He Y SIRT6 promotes COX-2 expression and acts as an oncogene in skin cancer. Cancer Res. 2014, 7, 5925–5933. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (31).Kumamoto T; Seki N; Mataki H; Mizuno K; Kamikawaji K; Samukawa T; Koshizuka K; Goto Y; Inoue H Regulation of TPD52 by antitumor microRNA-218 suppresses cancer cell migration and invasion in lung squamous cell carcinoma. Int. J. Oncol. 2016, 49, 1870–1880. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (32).Petkovic M; Jemaiel A; Daste F; Specht CG; Izeddin I; Vorkel D; Verbavatz J-M; Darzacq X; Triller A; Pfenninger KH; et al. The SNARE Sec22b has a nonfusogenic function in plasma membrane expansion. Nat. Cell Biol. 2014, 16 (5), 434–444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (33).Okayama A; Miyagi Y; Oshita F; Nishi M; Nakamura Y; Nagashima Y; Akimoto K; Ryo A; Hirano H Proteomic analysis of proteins related to prognosis of lung adenocarcinoma. J. Proteome Res. 2014, 13 (11), 4686–4694. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (34).Li LD; Sun HF; Liu XX; Gao SP; Jiang HL; Hu X; Jin W Down-regulation of NDUFB9 promotes breast cancer cell proliferation, metastasis by mediating mitochondrial metabolism. PLoS One 2015, 10 (12), 1–15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (35).Ming Z; Jiang M; Li W; Fan N; Deng W; Zhong Y; Zhang Y; Zhang Q; Yang S Bioinformatics analysis and expression study of fumarate hydratase in lung cancer. Thorac. Cancer 2014, 5 (6), 543–549. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (36).Lee SM; Kim JH; Cho EJ; Youn HD A nucleocytoplasmic malate dehydrogenase regulates p53 transcriptional activity in response to metabolic stress. Cell Death Differ. 2009, 16 (5), 738–748. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (37).Boyadjiev SA; Fromme JC; Ben J; Chong SS; Nauta C; Hur DJ; Zhang G; Hamamoto S; Schekman R; Ravazzola M; et al. Cranio-lenticulo-sutural dysplasia is caused by a SEC23A mutation leading to abnormal endoplasmic-reticulum-to-Golgi trafficking. Nat. Genet. 2006, 38, 1192–1197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (38).Li CC; Zhao L; Chen Y; He T; Chen X; Mao J; Li CC; Lyu J; Meng QH MicroRNA-21 promotes proliferation, migration, and invasion of colorectal cancer, and tumor growth associated with down-regulation of sec23a expression. BMC Cancer 2016, 16, 605. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (39).Dos Santos EO; Carneiro-Lobo TC; Aoki MN; Levantini E; Bassères DS Aurora kinase targeting in lung cancer reduces KRAS-induced transformation. Mol. Cancer 2016, 15, 12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Figure S-1. Plot of the logarithm of the median of all possible control/control ratios against the Mascot score.

Figure S-2. Plot of the logarithm of the median of all possible treated/control ratios against Mascot score.

Table S-1. Protein identification and iTRAQ-based relative quantification.