Highlights

-

•

Communities can respond to COVID-19 by mobilizing volunteers to coproduce services.

-

•

Long-term alliances between civic groups and governments enable volunteer action.

-

•

In the first wave, volunteers shifted to COVID relief, crowding out other causes.

-

•

Mobile technology and prior crisis experience galvinized professional volunteers.

Keywords: COVID-19, Coproduction, Community development, Volunteering, Asia, China

Abstract

The COVID-19 pandemic created a critical need for citizen volunteers working with government to protect public health and to augment overwhelmed public services. Our research examines the crucial role of community volunteers and their effective deployment during a crisis. We analyze individual and collaborative service activities based on usage data from 85,699 COVID-19 volunteers gathered through China’s leading digital volunteering platform, as well as a survey conducted among a sample of 2,270 of these COVID-19 volunteers using the platform and interviews with 14 civil society leaders in charge of coordinating service activities. Several results emerge: the value of collaboration among local citizens, civil society including community-based groups, and regional government to fill gaps in public services; the key role of experienced local volunteers, who rapidly shifted to COVID-19 from other causes as the pandemic peaked; and an example of state-led coproduction based on long-term relationships. Our analysis provides insight into the role of volunteerism and coproduction in China's response to the pandemic, laying groundwork for future research. The findings can help support the response to COVID-19 and future crises by more effectively leveraging human capital and technology in community service delivery.

1. Introduction

COVID-19 has drastically disrupted the personal and professional lives of billions of citizens globally and forced governments throughout the world to quickly adapt to a new reality characterized by increasing mortality rates, lockdowns, social distancing, and teleworking (Oldekop et al., 2020). The first wave of the pandemic overwhelmed public health systems worldwide, posing a threat not only to those directly infected and suffering, but to society at large (Weible et al., 2020). Governments face enormous challenges in dealing with the virus, adopting new policies, supporting vulnerable communities and individuals, making progress on sustainable development goals, and finding new ways to achieve results under intense pressure (Barbier and Burgess, 2020, Naidoo and Fisher, 2020).

Scholars have long argued that government response during a crisis needs to be coordinated with and supported by other actors, such as citizens, civil society including community and nongovernmental organizations, and other network partners (Kapucu, 2006). Collaboration among government, volunteers, and community groups can be considered a form of coproduction (Goodwin, 2019, Ostrom, 1972). Following Elinor Ostrom’s seminal work, coproduction can be defined as “the process through which inputs used to provide a good or service are contributed by individuals who are not ‘in’ the same organization” (Ostrom, 1996, 1073). Coproduction usually refers to the direct involvement of citizen “lay actors” (Nabatchi, Sicilia, & Sancino, 2017, 769) with government in voluntarily providing public services that create value for their communities (McGranahan, 2015, Ostrom, 1996). Coproduction can involve citizens and community groups, who are better aware of local conditions and help to assure that interventions reflect specific needs and customs (Ostrom, 1990, Verschuere, Brandsen, & Pestoff, 2012).

Volunteering is a key component of coproduction, as coproducing volunteers actively provide relevant public services to their own communities, typically without tangible compensation (Nabatchi et al., 2017). Working with volunteers and voluntary groups to provide community services has the potential to fill acute gaps and prevent public agencies from being overwhelmed during crisis events, such as COVID-19. Yet a main barrier to public volunteerism is government capacity to effectively utilize volunteers and to match volunteer coproducers with appropriate tasks (Gazley & Brudney, 2005).

Digital platforms (e.g., mobile apps) can play a key role in addressing this barrier, helping to marshal efforts and resources to ameliorate the effects of the pandemic. Communication-related mobile apps help overcome existing geographical, temporal, and organizational barriers (Lember, Brandsen, & Tõnurist, 2019) and scale the coproduction process by reaching more participants more quickly with up-to-date information (Meijer, 2012), while supporting non-pharmaceutical interventions such as social distancing that aim to reduce contact rates in times of contagion (Ferguson et al., 2020, Oldekop et al., 2020).

In China, after the initial outbreak of COVID-19 in Wuhan, the pandemic rapidly spread as the country began its most important annual holiday, the Spring Festival (Chen, Yang, Yang, Wang, & Bärnighausen, 2020). Following swiftly on the pandemic’s heels was a wave of volunteers, often recruited via mobile apps, to support and extend official efforts, engage in urgent on-the-ground tasks ranging from emergency transport and the delivery of food, masks, and medicine to vulnerable populations, and provide logistical support for frontline medical staff. In recent years, China’s government has come to realize the value of leveraging civil society organizations to deliver social services, meet public needs, and strengthen its own legitimacy (Moore, 2019, Schwarz, Eva, & Newman, 2020). As a result, volunteerism in China has gradually gained momentum since the 2008 Sichuan Earthquake, the 2008 Beijing Olympics, and the 2010 Shanghai World Expo (Cheung, Lo, & Liu, 2012).

As noted by Wu, Zhao, Zhang, and Liu, 2018, 1206), “the Chinese government has been a primary mobilizer of citizens’ volunteer participation,” often through community organizations assisting the state on local service delivery. This is an example of top-down and state-driven coproduction (Li, Hu, Liu, & Fang, 2019) that differs from the bottom-up coproduction frequently found in the global South (Castán Broto and Neves Alves, 2018, Mitlin, 2008). In China, volunteer networks are operated by community organizations yet endorsed by government (Hu, 2020) which initiates the process through long-term relationships with civil society and legitimates volunteer action.

Scholars state that “the evidence base for coproduction is relatively weak” (Nabatchi et al., 2017, 766) and “there has been little quantitative empirical research on citizen coproduction” (Bovaird, Stoker, Jones, Löffler, & Pinilla Roncancio, 2016). To close this research gap, we analyzed usage data from 85,699 COVID-19 volunteers gathered through China’s leading volunteering digital platform from January to February 2020, as the first wave of the pandemic peaked in China. We then conducted a more individualized survey among a sample of 2,270 of these COVID-19 volunteers followed by semi-structured interviews with 14 senior managers of civil society organizations in charge of coordinating the service activities in Zhejiang Province. This mixed methods approach involving three levels of data acknowledges the importance of methodological diversity in pursuit of a robust understanding of the research questions.

Our study makes two contributions to theory and practice. First, the volunteer dynamics seen here in terms of swift ramping up and switching over to COVID-19 suggest a “crowding out” or redeployment effect of experienced volunteers in response to the crisis. Second, China’s recent experience illustrates how community organizations and citizen volunteers can work together with public sector agencies at a local level. Their experience speaks to one of the classic challenges of coproduction: How to create sustainable cooperation between government and citizens that continues beyond a particular crisis, such as COVID-19, and forms enduring relationships to address future challenges (Lam, 1996, Schmidt, 2019). Despite these contributions, our study does have some limitations. The limited time frame and single-country focus restrict generalizability of the findings; instead, we aim to provide a useful base for future studies in multiple country settings, possibly with multiple rounds of data collection over time.

The remainder of this article is structured as follows: The next section details the methods used in collecting quantitative and qualitative data from volunteers on the frontlines of the pandemic in China. Section 3 analyzes the results, including volunteering trends and demographics during the peak, the role of experience and preparation, and the collaborative relationship of government, volunteers, and civil society. Finally, we interpret the findings through the lens of coproduction theory and make recommendations for the future.

2. Evidence from the COVID-19 frontline

We gathered the original digital data for this study from 85,699 volunteers working from January 21 to February 22, 2020—the period when the COVID-19 pandemic emerged, peaked, and subsided in eastern China. Existing data were collected via the ‘ZYH’ (ZhiYuanHui, meaning “volunteering together”) volunteer app, focusing on usage, overall volunteering patterns and aggregated demographic information (see sections 3.1. and 3.3.). As a mobile platform for smartphone users, ZYH is the most popular app for volunteers and a range of civil society organizations in China, operating in all 31 provinces. Its key functions include volunteer recruitment posts, a search function for individuals to find and join volunteer projects, and a social media element allowing participants to share their experiences. While not specifically launched for COVID-19, the app soon came to be used for pandemic-related volunteering in January 2020.

We then hosted an electronic survey through the ZYH app for individual volunteers from this larger user group. A total of 5,000 randomly selected COVID-19 volunteers received a survey invitation automatically generated by the ZYH system. The survey resulted in a respondent sample of 2,270 volunteers, a response rate of 45%, and provided more individualized information about their efforts, such as perceived effectiveness and experience (see sections 3.1.2., 3.2., and 3.3.).

Finally, one-on-one semi-structured interviews lasting approximately 20–30 min were conducted by one of the authors with 14 local civil society leaders who have played an important role in recruiting and deploying volunteers, using ZYH, during this time period. This provided information on volunteers and government collaboration from an organizational perspective (see sections 3.3. and 3.4.). Applying purposive sampling, we interviewed one civil society leader from each of 11 sub-provincial and prefecture-level cities, along with three additional leaders interviewed from the hardest-hit cities (i.e., Hangzhou, Wenzhou, and Taizhou). These cities are valuable examples because each subprovincial or prefecture-level city encompasses a large metropolitan area with three to six million people, including an urban core and surrounding area of smaller cities, towns and villages.

3. Results

Our findings reveal numerous details about the rise in volunteer numbers, characteristics and experience of the volunteers, as well as government volunteer relations.

3.1. Rise and redeployment of COVID-19 volunteers

Digital usage data from the ZYH app (N = 85,699) over the span of one month (January 21 - February 22, 2020) provides a snapshot of volunteering in the eastern province of Zhejiang over the timeline of the pandemic. During this time period, these volunteers contributed a total of 3,544,780 volunteer hours averaging out to 41.36 hours per person on COVID-related efforts1 .

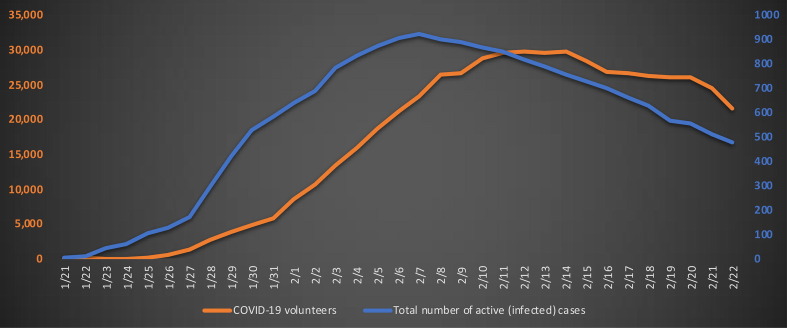

3.1.1. Pandemic spreads, volunteering rises

The daily volunteering rate began slowly and then grew robustly in response to the infection rate (see Figure 1 ). On January 21, the number of COVID-19 related volunteers working through the app in the region was just 9 among total ZYH volunteers of 12,111. As the virus took hold in central China’s Hubei Province, the capital city of Wuhan entered lockdown on January 23, with 16 more Hubei cities locking down by January 25 (Leung, Wu, Liu, & Leung, 2020). At the same time, volunteering in the east reached a low ebb as the Spring Festival or Lunar New Year, the most important Chinese holiday, began (Chen et al., 2020). As the virus swept east into Zhejiang, the daily volunteer rate rose: from 522 COVID-19 volunteers on January 26 to 18,553 on February 5. The city of Wenzhou in eastern Zhejiang locked down February 2, followed by semi-lockdowns across 50 major cities. Daily rates of volunteering grew as pandemic conditions worsened: by the time infections peaked on February 7, more than 20,000 volunteers per day were involved in Zhejiang relief efforts2 . The daily volunteering rate peaked at 29,772 on February 12 and remained above 20,000 through February 22, as the curve began to flatten and gradual re-opening began in Wenzhou and other hard-hit areas.

Fig. 1.

Number of COVID-19 Volunteers and Infected Cases per Day.

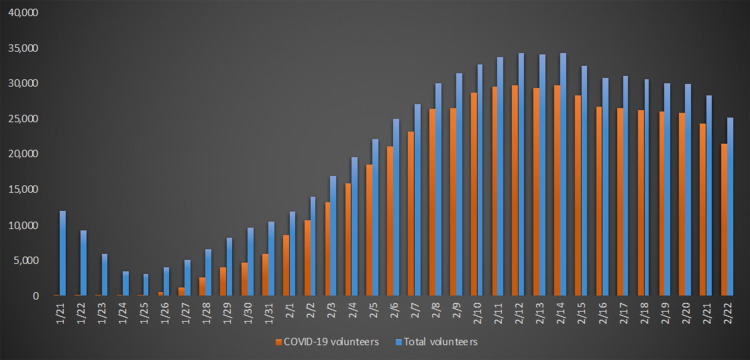

3.1.2. Crowding out or redeployment?

Based on digital usage data, Figure 2 highlights the volunteer focus on COVID-19 rather than other social issues during the peak of the pandemic. Early in the crisis, prior to January 24, COVID-related volunteers constituted less than 1% of total daily volunteers. The proportion of COVID-19-related volunteers rose swiftly from 4% on January 25 to 25% on January 27 to 50% on January 30 before peaking close to 88% of the volunteers on February 10. As the infection rate slowly subsided, the proportion of COVID-19 volunteers to total daily volunteers remained above 80% through February 22.

Fig. 2.

Number of COVID-19 Volunteers to Total Volunteers per Day.

The volunteer survey data (N = 2,270) further illuminates this trend. While some new volunteers joined due to the pandemic, the majority had previously enlisted for other causes. More than three-fourths (76.3%) of the surveyed volunteers were registered on ZYH before the pandemic (e.g., for environmental protection or elderly care) and shifted their focus to COVID-19, suggesting that the urgency of the pandemic “crowded out” other social issues. Viewed more positively, this crowding out represents redeployment of volunteer resources in a crisis.

Redeployment occurred at both organizational and individual levels, as noted in the qualitative interviews with civil society leaders. For instance, one community group that orginally supported special needs children expanded to offering pandemic-related support for this population and their families during the outbreak. Another organization that originally had focused on ridesharing adapted its efforts to provide emergency patient transport, material delivery, rescue, and logistics.

The crowding-out effect – or redeployment – matters not only to those causes that are temporarily abandoned but also to the process of coproduction. While coproduction is a voluntary effort on the part of individuals and organizations, a top-down approach led by the state (Li et al., 2019) has agenda-setting power to focus attention during a crisis, attracting and coordinating voluntary coproduction efforts in the public interest. Successful coproduction can also leverage long-term relationships among existing volunteers and local community groups (Joshi & Moore, 2004, Mitlin and Bartlett, 2018), who can rapidly redeploy from one issue to another while utilizing local knowledge and previous expertise in the face of a public crisis.

3.2. Characteristics of volunteers

As seen in the survey sample (N = 2270), volunteers came from a broad range of occupational backgrounds. This included private firms and entrepreneurs (19.2%), freelancers and not employed (18.3%), and public institutes such as health, science, and education (15.9%). While 10.8% of survey respondents stated they were mobilized by a leadership figure, 85.8% stated they volunteered on their own initiative, indicating a strong voluntary motive for the great majority.

Regarding gender, over the entire period (January 21 to February 22), the proportion of male volunteers was somewhat higher than that of females (55% vs. 45%), based on the digital usage data and in contrast with the findings in other contexts showing women’s higher volunteering rates (Parrado, Van Ryzin, Bovaird, & Löffler, 2013). This may be due to school closures, as well as China’s Spring Festival (January 25–26), when female family members are often preoccupied with household tasks and holiday preparations. As the pandemic worsened, the proportion of females volunteers increased, with 52–55% males remaining.

3.3. Experienced midlife volunteers

A further observation pertains to the experience and midlife stage of volunteers. During the pandemic, senior citizens could not be expected to volunteer, given the health risks involved. As a result, the average age of volunteers during the first wave was 40–42 years old, and this trend was consistent every day and night from mid-January to mid-February. This finding fits with volunteering patterns in other contexts such as the US and the UK, where well-qualified midlife citizens play a key role, particularly in community services (Wilson, 2012).

However, the real value of age is rooted in experience. Participants’ experience enhances professionalized service delivery, a key feature of coproduction, and a growing trend in volunteerism generally (Ganesh & McAllum, 2012). Both the survey and qualitative interviews provide insights regarding experience. Among survey respondents, those volunteers who had been registered longer on the ZYH app between 2015 and 2020, gaining volunteer experience, had a higher level of perceived effectiveness in terms of whether they believed the volunteering helped control the pandemic (based on an ANOVA of effectiveness score by ZYH registration year: F(5/2265) = 3.202, p < .007).

In addition, interviews with civil society leaders show they valued midlife volunteers for their experience gained through employment or previous crisis volunteering. One leader observed: “There are a total of 50 of our backbone volunteers. Many of them came out with me [before]. We are now 35 to 40 years old and have experienced a lot … including typhoons and earthquakes. They are very experienced in all aspects, and they have become our main backbone” [R10]. Other leaders commented, “Volunteers are in their 30s, 40s, and 50s. They are basically local people” [R2]; “We have participated in most of the disaster relief in China. Our team has rich experience and training” [R9].

This finding extends earlier work suggesting that the decision to coproduce is strongly influenced by the human capital and knowledge of citizens (Alford, 2009) and that older citizens are often more likely to collaborate with the public sector than their younger counterparts (Parrado et al., 2013). Scholars note that successful coproduction requires citizen competence such as experience and professional skills in order for individuals to feel confident contributing (van Eijk & Steen, 2014). In this way, coproduction taps into citizen resources as part of a portfolio of strategies to achieve broader public goals (Alford, 2009, Xue & Liou, 2012).

3.4. Government-volunteer relations

Many of the Zhejiang COVID-19 volunteers provided service through civil society organizations that have long-term relationships with regional and local governments to provide specific types of services to members of their own communities during times of need. Working at the city and county level, these organizations helped to organize the service, endorsed by and often led by government, with community volunteers delivering the service to extend the efforts of public professionals. Evidence of this arrangement emerged in all 14 of the interviews conducted with the civil society leaders, several of whom described examples of working with public agencies on previous efforts and emergencies. One leader commented: “Our nongovernmental public welfare organization works closely with the government. We cooperate with them, we want to make up for some of their deficiencies” [R10]. Another leader noted, “The government informs our organization of the places in need. It tells us the number of volunteers needed for each point. Then we are actively recruiting on the mobile app” [R14].

An example that illustrates the ongoing relationship is the case of the civil affairs bureau in the city of Wenzhou that formed a joint institute with a community organization, with each side contributing personnel and sharing an office space. Since 2012, they have jointly coordinated logistical and educational projects. During the pandemic, the institute and its volunteers acted as a channel for farm product distribution between rural areas and communities under lockdown [R14].

Examples such as these demonstrate how volunteer activity is coordinated by community groups at the behest of government agencies, which initiate requests through local networks of local organizations. This reflects a top-down version of coproduction that Li and colleagues termed “state-led coproduction” (2019, 250) in which the state retains control over critical components, setting priorities, and providing legitimacy. This approach contrasts sharply with the instances of bottom-up coproduction frequently found in the global South (Mitlin & Bartlett, 2018). Nevertheless, the provision of pandemic-related services has become more participatory in China, extending citizen involvement to areas previously reserved primarily for the government, due to necessity as well as policies encouraging volunteerism. While bottom-up forms of coproduction are an important strategy for grassroots organizations to increase political power (Castán Broto and Neves Alves, 2018, Mitlin, 2008), top-down state-led coproduction is useful during public crises that require swift, decisive action at the center as well as engagement of local communities to respond effectively.

4. Conclusion

This study generates lessons from the frontline of COVID-19 in China, based on digital data from 85,699 volunteers along with 2,270 survey respondents and interviews with 14 community leaders, with relevance for other countries combating the global pandemic (Oldekop et al., 2020). The results illustrate a key role for experienced volunteers who were able to swiftly deploy, or redeploy, to address the emerging crisis. A collaborative approach leveraging networks among public agencies, community organizations, and citizen volunteers allowed rapid mobilization to meet urgent demand for public services (Lee, Heo & Seo, 2020). These findings from Zhejiang Province provide empirical evidence of citizen coproduction through volunteering in east Asia, which has previously been neglected in the research (Bovaird, Stoker, Jones, Löffler, & Pinilla Roncancio, 2016, Ma and Wu, 2020).

On a conceptual and practical level, the study provides useful insights into top-down, state-led coproduction implemented through long-term relationships among local agencies, organizations and people. The localization of crisis response contrasts sharply with the expanding phenomenon of overseas volunteering (Meneghini, 2016) that uses professionals or youth from one country (usually from the global North) to carry out activities in another country (usually in the global South) for a limited period of time. It also diverges from primary reliance on government or international development organizations typically associated with crisis response. Relying on long-term local volunteers also helps to alleviate the gap in essential services left when volunteers from international NGOs must repatriate (Tierney & Boodoosingh, 2020). Instead, these COVID-19 volunteers in China were members of the communities they served who were able to understand local norms, relationships, and dialects, applying competences on the ground close to home. As Ostrom (1996, 1083) predicted, “coproduction rapidly spills over to other areas.” In our study, coproduction involving local volunteers and groups guided by government not only addressed COVID-19 but enhances capacity for swift ramping-up to fill gaps in services when future crises occur.

Despite the positive results, citizen volunteerism should not be considered a panacea for meeting public needs (Bovaird, 2007), or an opportunity for states to abrogate responsibility (McLennan et al., 2016), engage in cost-shifting, or divert additional burden to vulnerable groups (Mitlin & Bartlett, 2018). Such efforts are unlikely to result in sustained development or citizen engagement.

Going forward, coproduction is likely to become increasingly relevant. As the long-term effects of COVID-19 hit governments, there will be a growing need to involve citizen volunteers and community groups in capacity building (Moreno, Noguchi, & Harder, 2017). As noted by Weible and colleagues (2020, 236), “The pandemic calls on citizen coproduction in the realization of policy goals on an unprecedented scale.” Our findings offer a springboard for future research, to consider the potential of integrating experienced local volunteers, working through community organizations and public agencies, more systematically to meet societal needs.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Acknowledgment

The authors would like to thank Liam Campling, Alessandro Sancino, Trui Steen, Yuejun Wang, Yixing Zhao, Sipei Xu, Yufei Zhou, Tongtong Zhong, Laize Liu, and two anonymous reviewers for their very valuable comments on earlier versions of this article. This research was supported by grants from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (NSFC 71672174), Zhejiang Provincial Natural Science Foundation of China (ZPNSFC R17G020002), and Fundamental Research Funds for Central Universities in China.

Footnotes

Digital usage data from the app indicated 3,544,780 volunteer hours from January 21 to February 22. Dividing this figure by total number of COVID-related volunteers active on the app during this time period (85,699) gives an average of 41.36 hours per person.

Throughout February, nighttime volunteers averaged nearly 10% of volunteer shifts, working 4 to 5 hours per night.

References

- Alford, J. (2009). Engaging public sector clients: From service-delivery to co-production. Basingstoke, UK: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Barbier E.B., Burgess J.C. Sustainability and development after COVID-19. World Development. 2020;135:105082. doi: 10.1016/j.worlddev.2020.105082. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bovaird T. Beyond engagement and participation: User and community coproduction of public services. Public Administration Review. 2007;67(5):846–860. [Google Scholar]

- Bovaird T., Stoker G., Jones T., Löffler E., Pinilla Roncancio M. Activating collective co-production of public services: Influencing citizens to participate in complex governance mechanisms in the UK. International Review of Administrative Sciences. 2016;82(1):47–68. [Google Scholar]

- Castán Broto V., Neves Alves S. Intersectionality challenges for the co-production of urban services: Notes for a theoretical and methodological agenda. Environment and Urbanization. 2018;30(2):367–386. [Google Scholar]

- Chen S., Yang J., Yang W., Wang C., Bärnighausen T. COVID-19 control in China during mass population movements at New Year. The Lancet. 2020;395(10226):764–766. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30421-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheung C.-K., Lo T.W., Liu S.-C. Measuring volunteering empowerment and competence in Shanghai. Administration in Social Work. 2012;36(2):149–174. [Google Scholar]

- Ferguson N.M., Laydon D., Nedjati-Gilani G., Imai N., Ainslie K., Baguelin M.…Ghani A.C. Imperial College COVID-19 Response Team; London: 2020. Impact of non-pharmaceutical interventions (NPI) to reduce COVID-19 mortality and healthcare demand. [Google Scholar]

- Ganesh S., McAllum K. Volunteering and professionalization: Trends in tension? Management Communication Quarterly. 2012;26(1):152–158. [Google Scholar]

- Gazley B., Brudney J.L. Volunteer involvement in local government after September 11: The continuing question of capacity. Public Administration Review. 2005;65(2):131–142. [Google Scholar]

- Goodwin G. The problem and promise of coproduction: Politics, history, and autonomy. World Development. 2019;122:501–513. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, M. (2020). Making the state's volunteers in contemporary China. Voluntas: International Journal of Voluntary and Nonprofit Organizations, doi: 10.1007/s11266-019-00190-9.

- Joshi A., Moore M. Institutionalised co-production: Unorthodox public service delivery in challenging environments. Journal of Development Studies. 2004;40(4):31–49. [Google Scholar]

- Kapucu N. Interagency communication networks during emergencies: Boundary spanners in multi-agency coordination. The American Review of Public Administration. 2006;36(2):207–225. [Google Scholar]

- Lam W.F. Institutional design of public agencies and coproduction: A study of irrigation associations in Taiwan. World Development. 1996;24(6):1039–1054. [Google Scholar]

- Lee D., Heo K., Seo Y. COVID-19 in South Korea: Lessons for developing countries. World Development. 2020;135:105057. doi: 10.1016/j.worlddev.2020.105057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lember V., Brandsen T., Tõnurist P. The potential impacts of digital technologies on co-production and co-creation. Public Management Review. 2019;21(11):1665–1686. [Google Scholar]

- Leung K., Wu J.T., Liu D., Leung G.M. First-wave COVID-19 transmissibility and severity in China outside Hubei after control measures, and second-wave scenario planning: A modelling impact assessment. The Lancet. 2020;395(10233):1382–1393. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30746-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li B., Hu B., Liu T., Fang L. Can co-production be state-led? Policy pilots in four Chinese cities. Environment and Urbanization. 2019;31(1):249–266. [Google Scholar]

- Ma L., Wu X. Citizen engagement and co-production of e-government services in China. Journal of Chinese Governance. 2020;5(1):68–89. [Google Scholar]

- McGranahan G. Realizing the right to sanitation in deprived urban communities: Meeting the challenges of collective action, coproduction, affordability, and housing tenure. World Development. 2015;68:242–253. [Google Scholar]

- McLennan B., Whittaker J., Handmer J. The changing landscape of disaster volunteering: Opportunities, responses and gaps in Australia. Natural Hazards. 2016;84(3):2031–2048. [Google Scholar]

- Meijer, A. (2012). Co-production in an information age. In V. Pestoff, T. Brandsen, & B. Verschuere (Eds.), New public governance, the third sector and co-production, pp. 192–208. New York: Routledge.

- Meneghini A.M. A meaningful break in a flat life: The motivations behind overseas volunteering. Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Quarterly. 2016;45(6):1214–1233. [Google Scholar]

- Mitlin D. With and beyond the state — co-production as a route to political influence, power and transformation for grassroots organizations. Environment and Urbanization. 2008;20(2):339–360. [Google Scholar]

- Mitlin D., Bartlett S. Editorial: Co-production – key ideas. Environment and Urbanization. 2018;30(2):355–366. [Google Scholar]

- Moore S.M. Legitimacy, development and sustainability: Understanding water policy and politics in contemporary China. The China Quarterly. 2019;237:153–173. [Google Scholar]

- Moreno J.M., Noguchi L.M., Harder M.K. Understanding the process of community capacity-building: A case study of two programs in Yunnan Province, China. World Development. 2017;97:122–137. [Google Scholar]

- Nabatchi T., Sancino A., Sicilia M. Varieties of participation in public services: The who, when, and what of coproduction. Public Administration Review. 2017;77(5):766–776. [Google Scholar]

- Naidoo S., Fisher B. Sustainable development goals: Pandemic reset. Nature. 2020;583:198–201. doi: 10.1038/d41586-020-01999-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oldekop J.A., Horner R., Hulme D., Adhikari R., Agarwal B., Alford M.…Zhang Y.-F. COVID-19 and the case for global development. World Development. 2020;134:105044. doi: 10.1016/j.worlddev.2020.105044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ostrom E. Metropolitan reform: Propositions derived from two traditions. Social Science Quarterly. 1972;53(3):474–493. [Google Scholar]

- Ostrom E. Cambridge University Press; Cambridge: 1990. Governing the commons: The evolution of instituions for collective action. [Google Scholar]

- Ostrom E. Crossing the great divide: Coproduction, synergy, and development. World Development. 1996;24(6):1073–1087. [Google Scholar]

- Parrado S., Van Ryzin G.G., Bovaird T., Löffler E. Correlates of co-production: Evidence from a five-nation survey of citizens. International Public Management Journal. 2013;16(1):85–112. [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt A. Tensions and dilemmas in crisis governance: Responding to citizen volunteers. Administration & Society. 2019;51(7):1171–1195. [Google Scholar]

- Schwarz G., Eva N., Newman A. Can public leadership increase public service motivation and job performance? Public Administration Review. 2020;80(4):543–554. [Google Scholar]

- Tierney A., Boodoosingh R. Challenges to NGOs’ ability to bid for funding due to the repatriation of volunteers: The case of Samoa. World Development. 2020;136 doi: 10.1016/j.worlddev.2020.105113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Eijk C.J.A., Steen T.P.S. Why people co-produce: Analysing citizens’ perceptions on co-planning engagement in health care services. Public Management Review. 2014;16(3):358–382. [Google Scholar]

- Verschuere B., Brandsen T., Pestoff V. Co-production: The state of the art in research and the future agenda. Voluntas: International Journal of Voluntary and Nonprofit Organizations. 2012;23(4):1083–1101. [Google Scholar]

- Weible C.M., Nohrstedt D., Cairney P., Carter D.P., Crow D.A., Durnová A.P., Stone D. COVID-19 and the policy sciences: Initial reactions and perspectives. Policy Sciences. 2020;53(2):225–241. doi: 10.1007/s11077-020-09381-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson J. Volunteerism research: A review essay. Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Quarterly. 2012;41(2):176–212. [Google Scholar]

- Wu Z., Zhao R., Zhang X., Liu F. Impact of social capital on volunteering and giving: Evidence from urban China. Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Quarterly. 2018;47(6):1201–1222. [Google Scholar]

- Xue L., Liou K.T. Government reform in China: Concepts and reform cases. Review of Public Personnel Administration. 2012;32(2):115–133. [Google Scholar]