Highlights

-

•

What is the primary question addressed by this study?

-

•

How have ECT practices changed to adapt to public health guidelines for treating older adults amidst the coronavirus 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic?

-

•

What is the main finding of this study?

-

•

Electroconvulsive therapy (ECT) continues to be an essential treatment for older adults with severe mental illness, and extensive infection control and public health measures are being taken to mitigate risk of transmission while sustaining operations.

-

•

What is the meaning of the finding?

-

•

Substantial changes to ECT practices are anticipated to be long-standing and will likely evolve further in response to availability of testing and treatment for COVID-19.

Key Words: ECT, coronavirus, aerosol-generating

Abstract

The ubiquitous coronavirus 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic has required healthcare providers across all disciplines to rapidly adapt to public health guidelines to reduce risk while maintaining quality of care. Electroconvulsive therapy (ECT), which involves an aerosol-generating procedure from manual ventilation with a bag mask valve while under anesthesia, has undergone drastic practice changes in order to minimize disruption of treatment in the midst of COVID-19. In this paper, we provide a consensus statement on the clinical practice changes in ECT specific to older adults based on expert group discussions of ECT practitioners across the country and a systematic review of the literature. There is a universal consensus that ECT is an essential treatment of severe mental illness. In addition, there is a clear consensus on what modifications are imperative to ensure continued delivery of ECT in a manner that is safe for patients and staff, while maintaining the viability of ECT services. Approaches to modifications in ECT to address infection control, altered ECT procedures, and adjusting ECT operations are almost uniform across the globe. With modified ECT procedures, it is possible to continue to meet the needs of older patients while mitigating risk of transmission to this vulnerable population.

INTRODUCTION

With over 3.8 million cases in the United States alone,1 the coronavirus 2019 disease (COVID-19) caused by the novel coronavirus (SARS-CoV-2) has had a profound impact on health care systems. Because COVID-19 primarily presents as a respiratory illness and is transmitted through respiratory droplets, great care must be taken to reduce the risk of transmission during as electroconvulsive therapy (ECT), which involves an aerosol-generating procedure from manual ventilation with a bag mask valve while under anesthesia. The danger of ECT practice during COVID-19 is compounded as patients who undergo ECT are often older, frail, and at higher risk than the general population. ECT is deemed an essential procedure by the American Psychiatric Association2 and drastic changes to ECT practices have been necessary to mitigate risk for both patients and staff while continuing to provide essential care.

For the geriatric population with severe depression or psychosis who are highly burdened by psychiatric symptomatology, ECT is an important and necessary treatment. Data have shown that ECT is safe in older adults despite medical comorbidities and is highly effective in treating severe psychiatric illnesses such as major depressive disorder, psychosis, mania, and behavioral symptoms of dementia.3 , 4 Disruption in the acute course of ECT in the absence of adverse events would be harmful for older patients, potentially precipitating clinical decline.

Continuing safe administration of ECT to those who need it while at the same time maintaining safety for patients and staff presents an extraordinary challenge in clinical practice. In this paper we describe modifications in ECT practices due to the COVID-19 pandemic based on expert consensus. The aim is to help guide ECT clinicians in continuing to provide ECT in a manner that is safe for patients and staff while still preserving public health efforts to mitigate and avoid infection spread.

METHODS

The development of this expert consensus statement involved the following steps: 1) topic selection; 2) expert group discussion; and 3) systematic review of literature.

Topic Selection

The focus of this paper is on the impact of COVID-19 on ECT practices. Questions have arisen regarding what modifications are needed to administer ECT in a manner that is safe for both patients and staff, within the available resources, and consistent with good clinical practice. With such rapidly evolving information, a consensus statement will consolidate and disseminate current knowledge and provide guidance to ECT practitioners and stakeholders.

Expert Group Discussion

The expert group is comprised of ECT experts involved in the conduct of ECT-AD (A Randomized Controlled Trial of Electroconvulsive Therapy plus Usual Care versus Simulated-ECT plus Usual Care for the Acute Management of Severe Agitation in Alzheimer's Dementia), an NIH-funded multisite clinical trial of ECT for the treatment of severe agitation and aggression in dementia. The authors serve as site PIs (ML, AH, LN, MM, GP, BF), site co-investigators (SS, SS), and project manager (HH), and have expertise in psychiatry, geriatric psychiatry, and ECT clinical administration and research. The conception, design, and content of the manuscript were discussed during weekly ECT-AD meetings from March thru May 2020. In-depth discussions were held regarding modifications that were being implemented at each of the sites. In addition, an email question "Are there any changes to your ECT practice specific to geriatric patients?" was sent out to the International Society for ECT and Neurostimulation listserv and responses were compiled.

Systematic Review of Literature

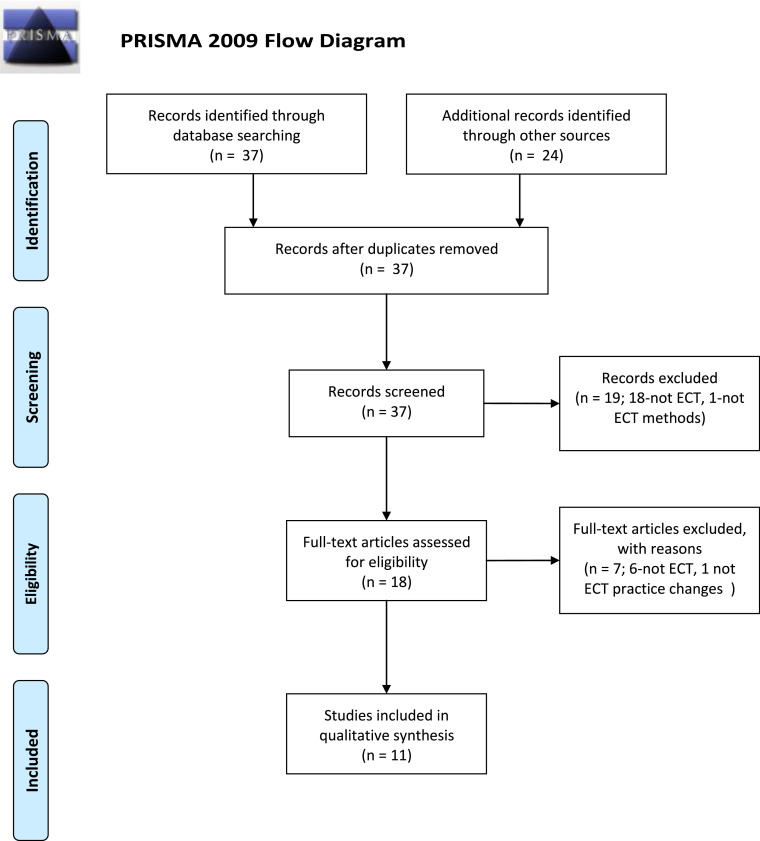

The literature was searched by a medical librarian for ECT or neurostimulation combined with COVID-19. The search strategies were created using a combination of keywords and standardized index terms. Searches were run in May 2020 in Google Scholar, Ovid EBM Reviews, Ovid Embase (1974+), Ovid Medline (1946+ including epub ahead of print, in-process & other non-indexed citations), Ovid PsycINFO (1806+), Scopus (1970+), and Web of Science (1975+). Results were limited to English citations from 2019+. All results were exported to Endnote where obvious duplicates were removed leaving 37 citations. Search strategies are provided in the appendix. Two authors (ML, SS) independently reviewed titles and abstracts to select relevant studies, and disagreements were resolved by consensus.

RESULTS

Results from ECT-AD discussions, insights from International Society for ECT and Neurostimulation members, and information from the systematic review are collated and described below.

Systematic Review

Of 37 articles identified from the search, 11 met inclusion criteria and were included in the review, reported in the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses flow diagram. (Fig. 1 ) The articles summarized in Table 1 include four from the United States and Canada, four from outside the United States, and three statements and guidelines from professional associations.

FIGURE 1.

PRISMA 2009 flow diagram. PRISMA, Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses.

TABLE 1.

Summary of Relevant United States and International Literature on ECT Practice Changes Due to COVID-19.

| United States/Canada | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Author, Year | Type of Article | Group/Specialty | Aim/Purpose | ECT Practice Modifications |

| Bryson and Aloysi, 202011US | Commentary | Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai Anesthesiology, Psychiatry |

To describe ECT strategies during the first 4 weeks of the SARS-CoV-2 outbreak in New York City. |

|

| Burhan et al, 202012 Canada |

Reflection | Parkwood Institute-Mental Health Care Building, an academic site of Western University in London Ontario Canada. |

To describe approach of a rigorous patient prioritization process for selection of ECT patients. |

|

| Espinoza et al, 202013 United States |

Editorial | UCLA, Medical University of South Carolina, Medical College of Georgia, Augusta University Psychiatry | To emphasize ECT as an essential treatment. |

|

| Flexman et al, 202014 | Consensus statement | Society for Neuroscience in Anesthesiology and Critical Care (SNACC) | To provide advice for neuroanesthesia clinical practice, including ECT. |

|

| International | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Author, Year | Type of Article | Group/Specialty | Aim/Purpose | ECT Practice Modifications |

| Braithwaite, 202010 United Kingdom |

Case report | Psychiatry | To describe successful ECT in a 67-year old male with life threatening severe major depression with catatonia, who was positive for SARS-CoV-2 with active symptoms and radiological evidence of pneumonitis. |

|

| Colbert, 202015 Ireland |

Images in Clinical ECT | Psychiatry | To illustrate visually the PPE ensemble worn by members of the ECT team, including gowns, headgear, masks, goggles and gloves. |

|

| Sienaert, 20209 Belgium |

Perspective | KU Leuven, Academic Center for ECT and Neuromodulation (AcCENT), Center of anatomical sciences and education UHasselt, Department of infection control, Department of Anesthesiology | To provide a perspective on the essential nature of ECT and describe measures to guide practitioners in safe administration of ECT. |

|

| Tor, 202016 Singapore |

Commentary | Department of Mood and Anxiety, West Zone, Institute of Mental Health | To describe ECT challenges in Singapore and describe ECT modifications to adapt to COVID-19 environment. |

|

| Non-indexed | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Author, Year | Type of Article | Group/Specialty | Aim/Purpose | ECT Practice Modifications |

| National Network of Depression Centers (NNDC), 202017 United States |

Announcement | NNDC is a network of depression centers that collaborate to advance state-of-the-science in the field of mood disorders. | NNDC Urges Medical Officials to Consider ECT an Essential Medical Service. |

|

| International Society for ECT and Neurostimulation (ISEN), 202018 United States |

Letter | ISEN is an international organization dedicated to promoting safe, ethical and effective use of ECT and other brain stimulation therapies for the treatment of neuropsychiatric illness through education and research. | To address concerns of ISEN members and ECT professionals on how best to provide ECT services during the crisis, and provides suggestions about practice adaptations. |

|

| Tenenbein et al, 202019 Canada |

Guidelines | University of Manitoba, Department of Anesthesiology, Perioperative & Pain Medicine, WRHA Anesthesia Program Anesthesia – Shared Health | To provide guidelines for providing ECT safely while mitigating risks of COVID-19 transmission. |

|

DISCUSSION

Based on the expert group discussions and systematic review of the literature, there is a clear universal agreement that ECT is an essential treatment that should continue to be provided even during this pandemic. There is a clear consensus regarding the modifications that are essential to ensure that providing ECT care is safe for patients and staff. There are also changes to care processes and workflow that are common to all ECT practices. (Fig. 2 ) Despite the clear consensus on current standards in ECT practice, there is a lack of literature specific to older adults. The following recommendations represent a consolidation of the expert group discussions, results of the systematic review, and incorporation of considerations specific to treating older adults with ECT in the current pandemic environment.

FIGURE 2.

Electroconvulsive therapy during COVID-19 pandemic Perioperative considerations.

Source: Flexman AM, Abcejo AS, Avitsian R, et al. Neuroanesthesia Practice During the COVID-19 Pandemic: Recommendations From Society for Neuroscience in Anesthesiology and Critical Care (SNACC). J Neurosurg Anesthesiol. 2020;32(3):202-209. doi:10.1097/ANA.0000000000000691

INFECTION PREVENTION AND CONTROL MEASURES

Based on the assumption that any patient is potentially infected or a carrier of COVID-19, ECT practices must follow standard, contact, and airborne precautions, as well as eye protection measures. Personal protective equipment protects health care workers, sanitation and disinfection practices reduce the risk of viral transmission, and clustering of ECT patients can help prevent cross contamination.

PPE

The use of PPE is imperative for staff protection, in order to reduce the spread of COVID-19 through patient contact. All health care personnel involved in the administration of ECT are required to wear N95 respirators, which require prior fit testing and education for N95 respirator use. A procedure mask can be worn over the N95 respirator as an additional precaution if prolonged or repeated use is anticipated. In addition to N95 respirators and procedure masks, goggles, eye shields, or face shields have been added to standard PPE to further prevent contact with potentially infected droplets. Gloves are required, and some use double gloves and replace the outer gloves after each patient in order to prevent cross contamination between patients. Gowns are standard and changed at varying times, although not required in some institutions.

While protecting health care personnel during ECT is paramount, the widespread shortage of proper PPE has presented extensive obstacles to this goal. Policies and guidelines on PPE are institution-specific and evolving based on PPE availability. In ECT facilities with adequate PPE resources, staff in the screening area, waiting room, preparation or IV room, and recovery room are also fitted with N95 respirators. A lack of surplus in most locations requires staff to be assigned one set of PPE, and to reuse as appropriate. Maintenance of N95 respirators is the responsibility of individual staff, and the N95 respirators can be kept in the ECT facility for reuse in individual, labelled bags. Like the N95 respirators, other protective equipment such as procedure masks, goggles, eye shields, or face shields also often need to be reused due to supply shortages. Gowns and head coverings however should be disposed of at the end of each day. Gloves are not reused. Every personnel must be trained in proper donning (putting on) and doffing (taking off), as well as PPE disposal. In general ECT clinics are restricting or completely banning the presence of non-essential personnel in the treatment area to maximize the preservation of PPE for essential staff.

Sanitation and Disinfection

The SARS-CoV-2 virus has been shown to survive in aerosols and on surfaces for many days.5 The need for environmental cleaning and decontamination lowers the risk of viral transmission. Treatment rooms are cleaned thoroughly after each treatment day, by housekeeping or facility staff. However, to protect janitorial staff or housekeeping, gloves and procedure masks are recommended, as well as limiting exposure to the treatment rooms to before or after the treatments are completed. This means that the treatment team personnel are responsible for sanitizing with hospital-grade wipes between patients, including the ECT machine, computer keyboards and/or mouse, anesthesia machine, and any countertop. ECT personnel replace outer gloves, or change gloves and wash hands, between each patient. Bite blocks, if used, should be disposable. To protect the anesthesia machine from being contaminated, a viral filter should be used for each patient. At the time of supply constraints, viral filters are placed in a paper bag, labeled and stored for future use on the same patient.

Clustering Strategy: Outpatient and Inpatient ECT

ECT treatment facilities that serve both inpatients and outpatients minimize patient-to-patient exposure by allocating the different populations to different treatment “clusters” or to different days, a practice which greatly decreases the chance of cross-contamination between groups during transport and recovery. Inpatients can be further clustered by unit. Some departments have also designated treatment “teams” who alternate working certain shifts to further reduce risk of exposure.

ECT patient census is also impacted greatly by the effects of COVID-19. As local incidence increases, having a patient test positive on a psychiatric inpatient unit becomes more likely. A moratorium on admissions for an inpatient unit thus leads to a lower inpatient ECT census, which can further affect the ability to schedule ECT for inpatients and outpatients on separate days and may require services to operate fewer days per week. Hospital administrations have also pressured many sites to reduce operational days.

Although never ideal, sites have had to reduce their current patient censuses - some by as much as half – in order to accommodate reduced operations. Reducing or altogether interrupting treatment can be somewhat standardized with the use of a flow chart or algorithm, but ultimately this must be carefully considered on a case-by-case basis. Important factors to consider are the age of the patient, their location (i.e., are they currently in a nursing home or living independently), and the potential outcome of relapse. When deciding whether or not to treat a patient during this time, a fundamental consideration is to weigh the risk of exposure to a hospital setting and potentially infected asymptomatic staff and/or other patients with the benefit of avoiding a severe relapse and admission to the emergency room.

CHANGES TO ECT PROCEDURES

Pre ECT

COVID screening is performed prior to each visit. Screening questions include 1) Does the patient have close contact with a person with a laboratory confirmed case of COVID-19? 2) In the last 14 days, has the patient experienced fever or new symptoms of cough or shortness of breath, sore throat, diarrhea, respiratory distress, chills, myalgias, loss of smell, or change or loss of taste sensation.

If a patient is symptomatic, COVID-19 testing is indicated. Whether to test asymptomatic patients coming from a higher risk environment such as a nursing home is dependent on several factors. If there have been known cases or contacts, then testing is recommended. However, some facilities have been on lockdown and have eliminated any contact between clients, and others may refuse to test asymptomatic individuals. Furthermore, state and federal guidelines regarding testing continue to evolve based on availability and other factors, making these decisions more complicated. Therefore, the decision to test an asymptomatic individual coming from a high-risk environment is case dependent but should be strongly considered.

During Treatment

Ventilation

Masked ventilation causing aerosolization may be the biggest risk to patients and staff in terms of potential exposure. The use of High Efficiency Particulate Air (HEPA) filters for masked ventilation and anesthesia prevent the anesthesia machine itself from becoming contaminated and exposing subsequent patients. Although not an ideal practice, rationing of these supplies is often necessary due to shortages; many sites are saving HEPA filters in biohazard bags to be used again for the same patient.

Some sites have used pre-oxygenation to avoid bagged mask ventilation (BMV) use during the procedure for appropriate patients.6 Pre-oxygenation is done with a regular or non-rebreather mask (slight difference between sites) for several minutes pre-treatment, and then having the patients self-hyperventilate as they go off to sleep to try to minimize BMV. While some patients still require BMV, it is avoided as much as possible, which has the advantage of cutting down the risk of aerosolization, and helps preserve HEPA filters.

Air recirculation

Given that BMV during ECT is an aerosol-generating procedure, facilities have revised the time interval between ECT treatments based on factors such as the size of ECT treatment rooms, capacity of the ventilation systems, air changes per hour in the building, and location of exhaust vents. Determining the air changes per hour or air circulation rate in the building will help roughly calculate time to clear up most of the room air and thereby the aerosols. The air circulation times can vary and are only estimates. Center for Disease Control has guidelines that help calculate the time required for air-borne contaminant removal by efficiency. Close attention should be paid to the assumptions in the tables provided in the appendices of the guideline.7 A collaboration between engineering infection control departments can be helpful in trying to determine a reasonable amount of time to wait before bringing another patient into the room. Some institutions have used two or more treatment rooms and alternate between rooms to allow more air recirculation between patients in each room. Obviously, this option is not available at many ECT sites.

Anesthesia

Anesthetic dosing generally has remained unchanged in response to the virus. However, some sites have tried to keep succinylcholine doses at the lower end of the safe range in order to allow for a quicker return of spontaneous breathing after the seizure. This minimizes BMV overall, and in sites using the preoxygenation and/or self-hyperventilation technique described above, may allow for the elimination of BMV altogether in some cases.

ECT titration

For newly-initiated acute courses of ECT, some ECT psychiatrists continue the usual method of determining the seizure threshold, while others have stopped the titration method to determine seizure threshold. One method being used is starting at 100% energy at the first ECT, in order to minimize the time a patient is not breathing since they are not being ventilated. Other methods include use of a prior stimulus dose (if applicable) or an age-based approach. When titration method is used to determine seizure threshold, other ECT providers use 6–12 times the seizure threshold for subsequent ECT when using right unilateral placement.

Post ECT

Recovery room practice has not been dramatically altered by the risk of COVID. However, recovery nurses should wear eye protection and surgical masks. Some sites felt that nurses working with patients in immediate recovery should have N95 masks given the risk of exposure due to close contact while patients may be coughing and emitting secretions. Patients who are coughing and not fully awake should be allowed to recover in the treatment room and be brought out only when they are not coughing. As early as possible, before bringing the patient out of the treatment room, a procedure mask should be correctly placed on the patient's face. Patients should be separated by at least 6 feet and/or physical barriers such as partitions or curtains, if possible. Some sites have shortened their stay requirement in the recovery room or recovery lounge (if a 2-stage recovery) in order to avoid crowding in these areas and maximize social distancing.

ECT OPERATIONS

Starting ECT

Nursing homes and other long-term care (LTC) facilities for older adults are known to have high transmission rates for infectious diseases, and thus have unfortunately become “hot spots” for the spread of COVID-19.8 For this reason, ECT services have had to be especially stringent when considering treating older patients referred from LTC facilities – not only due to the risk that an incoming patient may infect ECT staff and other patients, but also the risk of rapid spread to other vulnerable older adults if a patient carries COVID-19 back to their LTC facility. It is paramount to involve the medical staff at the LTC facility when weighing the pros and cons of treating these patients. In places where pre-op testing is not readily available, some ECT services have chosen to stop accepting any geriatric patients or those coming from LTC facilities.

Stopping ECT

Due to the COVID-19 crisis, many centers felt significant pressure to quickly and dramatically reduce the size of their ECT census. Given this, and the increased mortality and morbidity risk of COVID-19 to geriatric patients, the decision regarding continuing ECT treatment, especially in the continuation or maintenance phase requires a risk and/or benefit analysis. Treatment discontinuation, in some cases, can result in dangerous relapse of symptoms that are not well controlled by other means which could send patients to the emergency room – an especially hazardous setting for a geriatric patient during this time. Additionally, a full relapse can result in an inpatient admission and the need for another acute course of ECT, which both introduces additional risks to the patient and utilizes more valuable resources. To avoid this, clinicians are tapering down the frequency of ECT treatments slowly while patients are closely monitored by the primary psychiatric providers. Close communication between the ECT service and the outpatient treating psychiatrist is essential to establish a safe treatment plan.

To Treat or Not to Treat

In the US, it is clear across ECT practices that any known COVID-19 positive patient, whether symptomatic or not, does not get treated with ECT unless it is determined as life-saving for a life-threatening condition. In such rare cases, ECT should be administered in an operating room set-up with negative pressure. However, in Belgium patients with COVID-19 continue to receive ECT with a special treatment schedule,9 and a single case report in the UK described successful ECT treatment of a patient with severe catatonia who was ill with COVID-19.10

In patients who previously tested positive but are now asymptomatic, the criteria for treating with ECT are either 1) 2 weeks from being diagnosed and 3 days of being asymptomatic, or 2) 2 weeks of being asymptomatic. The same criteria can be used for people who had symptoms suggestive of COVID-19 but were never tested as the symptoms did not meet testing threshold. With all patients, 2 consecutive negative tests and no new exposure indicate it is safe to proceed with ECT. For patients who test positive during a course of ECT, the decision to extend testing to other patients is based on clinical indications and clinical judgment. These criteria vary by ECT practice.

Consent Issues

An important issue that is missing in the literature is that of informed consent and disclosure of risks related to COVID-19 transmission, which is particularly important in older adults who have increased risk of more severe illness and morbidity from COVID-19. Based on expert group discussions, there is a consensus that the potential risk of COVID-19 transmission should be discussed with the patients and the legal authorized representatives or substitute decision-makers. Across all the ECT practice sites, written consent forms for ECT have not been altered to include specific COVID-19 wording, consistent with all other practices that involve aerosol-generating procedures.

CONCLUSIONS

There is a clear and universal consensus that ECT is a critical and essential treatment. In older adults, ECT may be life saving for treatment resistant depression, depression with psychotic features, catatonia, and severe agitation and aggression in individuals with dementia. Reduction in the delivery of both acute and maintenance ECT treatment for older adults as a result of COVID-19 restrictions have resulted in less effective treatment and greater relapse of severe mood disorders and agitation in older adults. Further, the clinical practice of ECT has rapidly changed as a consequence of the pandemic, and approaches to mitigate infection transmission in the setting of the COVID-19 are almost uniform across the globe. Current testing for COVID-19 is limited by testing equipment availability and treatment trials and vaccine development are in very early stages of development. Therefore, modifications to the practice of ECT are likely to last for a substantial period of time and may evolve further as the understanding and treatment of COVID-19 and availability of PPE improve. The community of clinicians involved in neurotherapeutics must continue to collaborate, share lessons learned and collect systematic outcome data to ensure safe access to ECT administered with the highest standards of infection mitigation.

Authors’ Contribution

MIL wrote this manuscript using content gathered by, and with revision from, SS, APH, BPF, SNS, GP, LN, and MM. HLH contributed to the organization, composition, and revision of the manuscript.

Acknowledgements

The ECT-AD project described is supported by the National Institutes of Health through Grant R01 AG061100. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the NIH.

Disclosure

The authors thank Hannah M. Chapman for help with manuscript preparation, Danielle J. Gerberi, M.L.S., AHIP for creating systematic review search strategies, Joyce R. McFadden, M.L.S., AHIP for assistance with obtaining articles for systematic review, and William E. Hoffman for assistance with copyright and permission.

The authors report no conflicts with any product mentioned or concept discussed in this article.

References

- 1.CDC . 2020. Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) in the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/cases-updates/cases-in-us.html Published June 24. Available at: Accessed June 24, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 2.APA: Practice Guidance for COVID-19. Available at: Accessed May 13, 2020. https://www.psychiatry.org/psychiatrists/covid-19-coronavirus/practice-guidance-for-covid-19. Accessed August 24, 2020

- 3.Meyer JP, Swetter SK, Kellner CH. Electroconvulsive therapy in geriatric psychiatry: a selective review. Psychiatr Clin North Am. 2018;41:79–93. doi: 10.1016/j.psc.2017.10.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hermida AP, Tang Y-L, Glass O. Efficacy and safety of ECT for behavioral and psychological symptoms of dementia (BPSD): a retrospective chart review. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry Off J Am Assoc Geriatr Psychiatry. 2020;28:157–163. doi: 10.1016/j.jagp.2019.09.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.van Doremalen N, Bushmaker T, Morris DH. Aerosol and surface stability of SARS-CoV-2 as compared with SARS-CoV-1. N Engl J Med. 2020;382:1564–1567. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc2004973. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Luccarelli J, Fernandez-Robles C, Fernandez-Robles C. Modified anesthesia protocol for electroconvulsive therapy permits reduction in aerosol-generating bag-mask ventilation during the COVID-19 pandemic. Psychother Psychosom. 2020:1–6. doi: 10.1159/000509113. Published online June 18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.2019. Environmental Guidelines | Guidelines Library | Infection Control | CDC.https://www.cdc.gov/infectioncontrol/guidelines/environmental/index.html Published July 23. Available at: Accessed May 26, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Davidson PM, Szanton SL. Nursing homes and COVID-19: We can and should do better. J Clin Nurs. 2020 doi: 10.1111/jocn.15297. Published online April 12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sienaert P, Lambrichts S, Popleu L. Electroconvulsive therapy during COVID-19-times: our patients cannot wait. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry Off J Am Assoc Geriatr Psychiatry. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.jagp.2020.04.013. Published online April 22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Braithwaite R, McKeown HL, Lawrence VJ. Successful electroconvulsive therapy in a patient with confirmed, symptomatic covid-19. J ECT. 2020 doi: 10.1097/YCT.0000000000000706. Publish Ahead of Print. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bryson EO, Aloysi AS. A strategy for management of ECT patients during the COVID-19 pandemic. J ECT. 2020 doi: 10.1097/YCT.0000000000000702. Published online May 12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Burhan AM, Safi A, Blair M. Electroconvulsive therapy for geriatric depression in the COVID-19 Era: reflection on the ethics. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2020;0 doi: 10.1016/j.jagp.2020.05.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Espinoza RT, Kellner CH, McCall WV. Electroconvulsive therapy during COVID-19: an essential medical procedure-maintaining service viability and accessibility. J ECT. 2020;36:78–79. doi: 10.1097/YCT.0000000000000689. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Flexman AM, Abcejo AS, Avitsian R. Neuroanesthesia practice during the COVID-19 pandemic: recommendations from society for neuroscience in anesthesiology and critical care (SNACC) J Neurosurg Anesthesiol. 2020;32:202–209. doi: 10.1097/ANA.0000000000000691. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Colbert S-A, McCarron S, Ryan G. Images in clinical ECT: immediate impact of COVID-19 on ECT practice. J ECT. 2020 doi: 10.1097/YCT.0000000000000688. Published online March 31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tor PC, Phu AHH, Koh DSH. ECT in a time of COVID-19. J ECT. 2020 doi: 10.1097/YCT.0000000000000690. Published online March 31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.NNDC Urges Medical Officials to Consider ECT an Essential Medical Service . 2020. National Network of Depression Centers.https://nndc.org/nndc-urges-medical-officials-to-consider-ect-an-essential-medical-service/ Published April 21. Available at: Accessed June 21, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 18.ISEN . 2020. COVID-19 and ECT Letter. Published online. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tenenbeim M, Enns M, Haberman C. 2020. COVID-19 Guidelines for ECT in Shared Health.https://umanitoba.ca/faculties/health_sciences/medicine/units/anesthesia/media/ECT-COVID19_Guidelines_April_9_2020.pdf Published online April 7. Available at: Accessed August 24, 2020. [Google Scholar]