Abstract

Objective

This study aimed to investigate the atypical computed tomography (CT) presentations of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) patients to comprehensively understand this highly infectious disease.

Methods

The clinical and chest CT imaging data of 16 patients diagnosed with COVID-19 were retrospectively analyzed, and patients with atypical CT presentations were selected for analysis and review.

Results

Of the 16 patients, 6 had atypical CT presentations, including 2 with faint ground glass opacities, 2 with single nodule, 1 with predominantly linear opacities, and 1 with predominantly reticular opacities. The dynamic changes of CT showed the faint ground glass opacities gradually became weak (2 cases). The scope of the single nodule was enlarged, and it developed into consolidation and residual fibrosis (2 cases). There was no obvious change of linear opacity (1 case). The reticular opacities were enlarged, then partially absorbed and new developed ground-glass opacities were found. Finally, the lesions were absorbed with residual fibrosis (1 case).

Conclusion

Atypical CT presentations of COVID-19 can be classified as faint ground glass opacities, single nodule, linear opacities, and reticular opacities. Understanding the atypical presentation of COVID-19 is beneficial in the assessment and epidemic prevention and control of this disease.

Keywords: Coronavirus, Pneumonia, Computed tomography

1. Introduction

The imaging changes in coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pneumonia have been extensively reported in the literature since its outbreak [[1], [2], [3], [4], [5]], but its atypical computed tomography (CT) presentations are rarely described. Timely confirmation of CT imaging data in such patients can provide reference for early clinical diagnosis, timely isolation and treatment, and improving patient prognosis. To further improve the radiographic examination and diagnosis of COVID-19 in patients, this study retrospectively analyzed the clinical and imaging data of 16 patients and selected 6 patients with atypical CT presentations for analysis. Further, we have summarized the findings with the aim of improving the level of imaging diagnosis.

2. Material and methods

2.1. Clinical data

The Institutional Review Board of Central People's Hospital of Zhanjiang approved this retrospective study and waived the requirement for informed consent due to the nature of the study. We have abided by patient data confidentiality and compliance as set out in the with the Declaration of Helsinki. Clinical and imaging data of 16 COVID-19 patients diagnosed between January 23, 2020 and February 19, 2020 were collected. All patients were diagnosed with COVID-19, as confirmed by two positive test results on reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction for severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) nucleic acid test. Among them, 6 patients (2 men and 4 women) aged between 25 and 68 years (average age, 44.6 years) exhibited atypical CT presentation. All these 6 patients had history of travel or residence in Wuhan 2 weeks before the onset of illness or had close contact with patients having fever from Wuhan before the onset of illness. Patients' general clinical data, body temperature, peripheral white blood cell (WBC) count, and C-reactive protein, procalcitonin, D-dimer, fibrinogen, and lactate dehydrogenase levels are shown in Table 1 .

Table 1.

Clinical characteristics of the patients with coronavirus disease 2019.

| Case | Gender | Age (years) | First symptom | Temperature (°C) ( × 109/L) | Lymphocyte Cell counts/L | Leukocyte | CRP mg/L | POCT ng/ml | D-Dimer μg/ml | FIB g/L | LDH U/L |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Male | 26 | Fever, fatigue | 38.6 | 3.1↓ | 0.87↓ | 13.11↑ | 0.6↑ | 0.44 | 2.38 | 185 |

| 2 | Male | 29 | Fever, cough | 37.8 | 6.0 | 2.76 | 0.10 | 0.206 | 0.13 | 3.91 | 197 |

| 3 | Female | 24 | Cough | 36.2 | 4.9 | 1.36↓ | 0.10 | 0.112 | 0.42 | 2.37 | 114 |

| 4 | Female | 25 | Fever | 38.0 | 5.7 | 2.42 | 0.10 | 0.136 | 0.21 | 2.66 | 197 |

| 5 | Male | 24 | Fever, cough | 38.2 | 4.6 | 1.25↓ | 0.10 | 0.1 | 0.22 | 3.12 | 166 |

| 6 | Male | 40 | Fever, cough, fatigue | 37.6 | 5.0 | 1.85 | 0.10 | 0.371 | 0.18 | 3.34 | 142 |

| 7 | Male | 30 | Fever, cough | 37.9 | 4.4 | 1.62 | 17.24↑ | 0.082 | 0.27 | 4.58↑ | 233 |

| 8 | Female | 40 | Fever, cough | 37.3 | 4.2 | 1.52 | 0.01 | 0.112 | 0.38 | 2.75 | 133 |

| 9 | Male | 55 | Fever, cough, fatigue | 38.5 | 3.4↓ | 0.93↓ | 29.93↑ | 0.237 | 0.46 | 4.01↑ | 279↑ |

| 10 | Male | 68 | Fever, headache,cough, sputum | 38.6 | 3.8↓ | 1.05↓ | 67.94↑ | 2.1↑ | 0.51 | 5.13↑ | 232 |

| 11 | Female | 33 | Fever, cough, sputum | 38.6 | 4.1↓ | 1.34↓ | 0.10 | 0.221 | 0.37 | 4.06↑ | 319↑ |

| 12 | Female | 65 | Fever, cough | 38.0 | 6.3 | 0.77↓ | 31.96↑ | 0.905↑ | 0.44 | 4.58↑ | 326↑ |

| 13 | Male | 25 | Fever, cough, sputum | 37.5 | 7.3 | 1.53 | 49.80↑ | 0.224 | 0.33 | 5.61↑ | 247↑ |

| 14 | Female | 25 | Cough | 36.2 | 4.9 | 1.36↓ | 0.10 | 0.112 | 0.42 | 2.37 | 114 |

| 15 | Male | 24 | Fever | 37.4 | 6.5 | 1.77 | 0.10 | 0.183 | 0.17 | 3.91 | 249↑ |

| 16 | Male | 46 | Fever | 37.6 | 6.3 | 2.82 | 0.01 | 0.211 | 0.22 | 2.56 | 176 |

CRP, C-reactive protein; POCT, procalcitonin; FIB, fibrinogen; LDH, lactate dehydrogenase.

2.2. Examination protocol

The SIEMENS SOMATOM Definition 16-row spiral CT was used for chest CT scanning. During CT, patients were placed in a supine position with their hands raised, and the scan was performed from the apex to the base of the lung while the patients held their breath. The scanning conditions were as follows: tube voltage, 100 kV (CARE Dose4D automatic tube current modulation technology was used to adjust tube current); reference tube current, 50 mA; slice thickness, 5 mm; and slice interval, 5 mm. After the scan was completed, multislice CT thin-layer reconstruction technology was used to reconstruct the images with a thickness of 1.0 mm and an interval of 1.0 mm.

2.3. Image analysis

Dynamic changes in the shape, distribution, density, margins, and images of multiple chest CT lesions in the early, progressive, and recovery stages were observed and analyzed. All radiographic images were independently analyzed by two attending radiologists, and consistent results were achieved through discussion and consensus. SPSS22.0 statistical software was used for statistical analysis. Consistency test was used to evaluate whether the chest CT manifestations of COVID-19 patients were typical and Kappa value was calculated.

3. Results

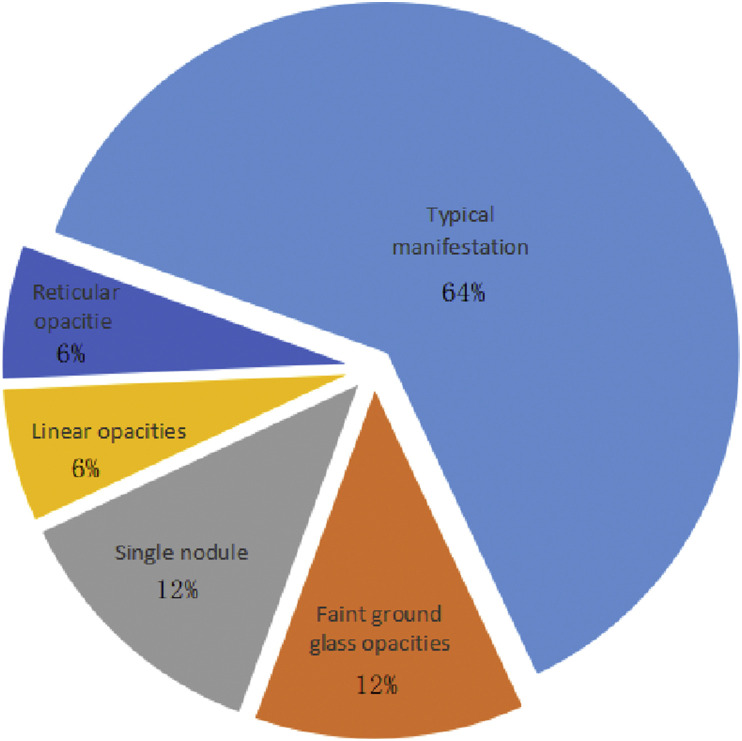

The results of chest CT were consistent between the two observers (Kappa = 0.72), and 6 cases (6/16,37.5%) were relatively atypical. The clinical types of the 6 atypical cases were all of the common type, including 2 cases of faint shadows (Fig. 1 ), 2 cases of single nodular type (Fig. 2 ), 1 case of predominantly linear shadows (Fig. 3 ) and 1 case of predominantly reticular opacities (Fig. 4 ) with CT findings, and the proportion of each type was shown in Fig. 5 . Of these 6 patients, 5 underwent CT examination within the first 1–3 days of disease onset, with 1 case of bilateral upper lung faint flaky shadows, 1 case of single faint shadow on the medial basal segment of the lower right lung, 2 cases of single subpleural nodular opacities (1 case in the posterior segment of the upper right lung and 1 case in the posterior basal segment of the lower left lung), and 1 case of reticular opacities in the posterior basal segment of the lower right lung. For the 5 patients who underwent examination at the early stages of disease onset, a second CT examination was performed on days 3–5. There were 2 cases of enlarged single nodules, of which there was 1 case of flaky consolidation opacities with unclear margins in the basal segment of the lower left lung; 1 case of faint shadows in the medial basal segment of the right lower lung; 1 case of bilateral faint shadows in the upper lungs that had generally dissipated; and 1 case of interlobular septal thickening and bronchovascular bundle thickening appearing as a reticular opacity in the lateral basal segment of the lower right lung that had higher extent than that observed before. A third CT examination was performed on days 6–9, and there were 2 cases of dissipated single subpleural lesions; 1 case of dissipation and reduction of lesions in the lateral basal segment of the lower right lung than that observed before, with a new reticular opacity in the medial basal segment and a small amount of ground-glass opacity; and 1 case of bilateral multiple linear opacities on initial CT examination after transfer from an outside hospital at day 7 after disease onset. On day 15, there was a slight progression of the lesion in the lateral basal segment of the lower right lung, and the lesions in the medial basal segment had dissipated than that observed before.

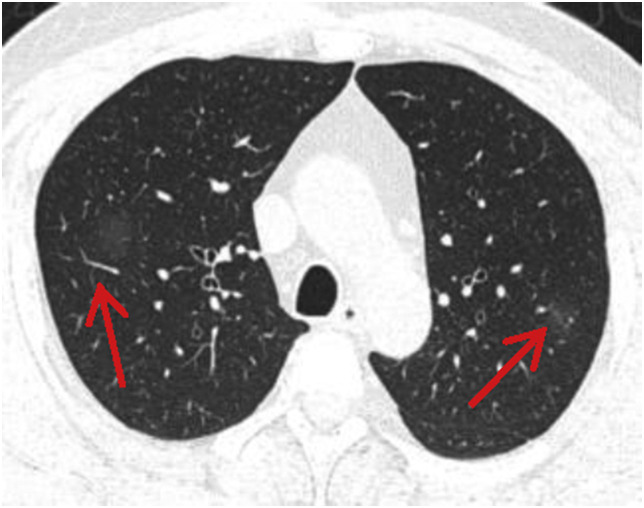

Fig. 1.

A 46-year-old male patient with fever for 0.5 days. Computed tomography revealed faint shadows (arrows) with unclear margins in the upper lungs.

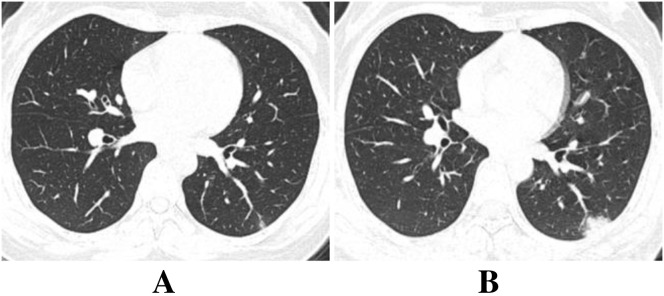

Fig. 2.

A 40-year-old female patient admitted for fever and cough for 4 days and diarrhea for 2 days. A, on day 1 after admission, computed tomography revealed a small nodular opacity in the posterior basal segment of the lower left lung; B, on day 3, the lesion exhibited a small patchy consolidation opacity with unclear margins.

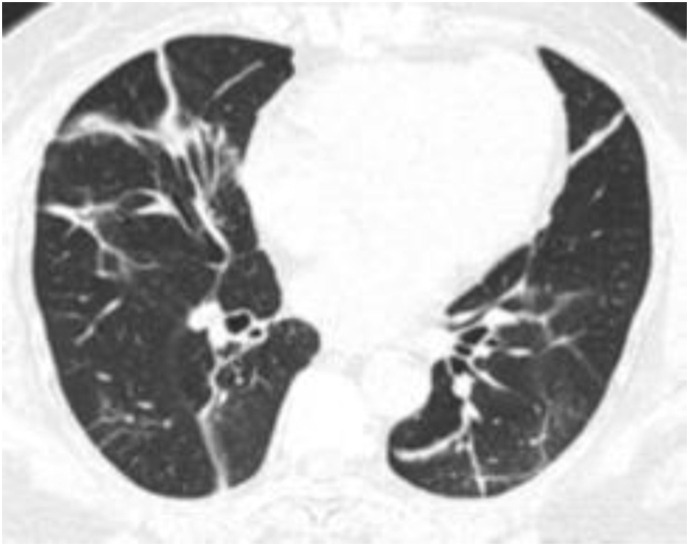

Fig. 3.

A 64-year-old female patient transferred from an outside hospital after treatment for 7 days with fever for 3 days. Computed tomography revealed multiple linear opacities in the lungs with clear margins.

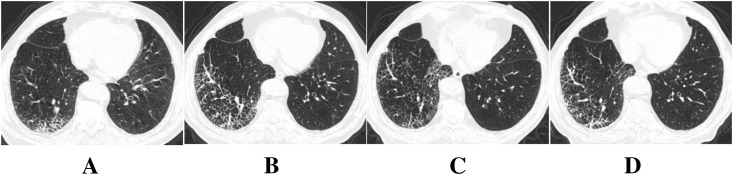

Fig. 4.

A 68-year-old male patient admitted after 2 days of fever, headache, cough, and sputum. A, on day 2, computed tomography revealed interlobular septal thickening in the posterior basal segment of the lower right lung. B, on day 5, interlobular septal thickening and bronchovascular bundle thickening were observed in the posterior and lateral basal segments of the lower right lung, which appeared as reticular changes, and the extent of the lesion increased. C, on day 9, the lesions in the posterior and lateral basal segments of the lower right lung were dissipated and reduced than that observed before, and there was a new reticular opacity and a small amount of ground-glass opacity in the medial basal segment. D, on day 15, the lesions in the posterior and lateral basal segments of the lower right lung progressed slightly more than before, and the medial basal lesions were more dissipated than before.

Fig. 5.

Distribution of the proportion of CT manifestations of COVID-19.

4. Discussion

4.1. COVID-19 clinical presentation and laboratory examination

COVID-19 is clinically characterized by fever, fatigue, and dry cough, which is accompanied by nasal congestion, runny nose, sore throat, and diarrhea in a small number of patients [6]. Among the clinical symptoms of the 6 patients in this cohort, 3 patients presented with fever at early stages and gradually developed cough and sputum symptoms, 2 patients presented with only fever, and 1 patient presented only with cough and not fever. It can be observed that some COVID-19 symptoms in this cohort are atypical and have hidden characteristics. Laboratory tests at the early stages of the disease usually reveal that the total peripheral WBC count is normal or decreased, the lymphocyte count is decreased, and liver enzyme, creatine kinase, and myoglobin levels are occasionally increased. Additionally, most patients have elevated C-reactive protein levels and erythrocyte sedimentation rates and normal procalcitonin levels, with elevated D-dimer levels in patients with severe COVID-19 [6]. In this cohort of 6 patients, the WBC count was normal or decreased and lymphocyte count was decreased in 3 patients (50%), suggesting that the patients had significant immune damage to the body's cells, which may be associated with infection of lymphocytes or induction of cytotoxicity or apoptosis by SARS-CoV-2 [7]. Etiological evidence is key to the diagnosis of COVID-19. Positive SARS-CoV-2 nucleic acid test results can be obtained from pharyngeal swabs, sputum, lower respiratory tract secretions, and blood, but false-negative nucleic acid test results are possible when the viral load is low. Therefore, when the patient's epidemiological history is known and chest CT findings support changes associated with viral pneumonia, a diagnosis cannot be completely ruled out even with multiple negative nucleic acid test results, and the patient should be followed up closely [8].

4.2. Atypical computed tomography presentation of COVID-19 and its pathological mechanism

There have been several reports on the typical presentation of COVID-19 on chest CT [[1], [2], [3], [4], [5]]. Common CT manifestations include multiple bilateral patchy ground-glass opacities and consolidation opacities that are predominantly distributed along the bronchovascular bundles and in the subpleural space, between which vascular thickening opacities and fine reticular opacities can be observed, which appear as a “crazy-paving pattern.” The 6 patients in this cohort had rare, atypical CT presentations such as faint shadows, single nodules, linear opacities, and reticular opacities. It may be related to the time of onset, length of disease and the underlying lung diseases, which should be closely related to clinical comprehensive analysis. In the 2 cases with faint shadows, the lesions could be easily overlooked. The patient may have been in the early stages of the disease, which is related to a small amount of virus replication, swelling of the alveolar wall epithelium, and mild involvement of the interlobular interstitial tissue [1,2]. In the 2 cases, single nodules were located in the subpleural space outside the lung tissue, meeting the distribution characteristics typical of COVID-19. Because of the small size of the virus (diameter: 60–140 nm), it can easily reach the distal airway, subsequently affecting the terminal bronchioles and lung interstitial tissue surrounding the respiratory bronchioles. However, the 2 patients only exhibited a single small nodule, in contrast to the typical multiple ground-glass opacities, which may be related to the extent of virus involvement being limited to only the interstitial tissue of the lobular core. Since lymphatic reflux in the lobular core area is centripetal, a round lobular core nodule can form easily. As the disease progresses, the area around the lobule also becomes involved, which subsequently spreads to the entire secondary lobule and diffuses to the surroundings, forming a small flaky consolidation opacity. There was 1 case of predominantly reticular opacities involving the lower right lobe. This may be because the bronchi in the lower right lobe are thick and short, the virus could enter more easily, and the target cells of COVID-19 might be located in the lower respiratory tract [9]. In this case, reticular opacities were predominant because the patient had chronic bronchitis and emphysema as underlying diseases. Hence, interlobular septal thickening and bronchovascular bundle thickening were observed in varying degrees from the early stages of the disease through the progressive stage and the recovery stage and only a few ground glass-like lesions were observed. During progression and dissipation, some lesions resolved but again progressed after treatment, suggesting that the imaging changes not only were restricted by the pattern of disease development but also were related to the treatment protocol, efficacy of treatment, presence of underlying diseases, age, and immune function. There was 1 case of predominantly linear opacities, which was transferred from an outside hospital. The initial CT examination performed at day 7 after onset in this case revealed multiple bilateral linear opacities in the lungs, classifying it as the resolution stage of disease. Since the virus primarily exhibits interstitial involvement with more lymphocyte infiltration, the alveolar pores are smaller, and the lesions dissipate relatively slowly, linear opacities persist for a long period of time during the process of dissipation, and a comprehensive judgment should be made in close conjunction with the clinical course to avoid misdiagnosis as chronic inflammation.

Different types of lung injury are caused by different viruses, but the same family of viruses causes similar pathological changes [10]. Although detailed reports on the pathological changes of COVID-19 are still insufficient, there have been reports describing the pathological changes on autopsy, and the pathological characteristics of COVID-19 are significantly similar to those of severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) and Middle East respiratory syndrome (MERS), which mainly manifest as diffuse alveolar injury, shedding of alveolar epithelial cells, and hyaline membrane formation [11]. The pathological changes of COVID-19 on autopsy, together with the pathological manifestations of SARS and MERS as a reference, are beneficial for understanding the mechanisms of atypical chest CT presentation of COVID-19.

The present study still has some limitations. Due to the limited number of case samples and the short study period, there is some research bias, and there are no imaging scores for clinical typing. Hence, further in-depth studies with large sample sizes are required. In summary, COVID-19 has a variety of atypical presentations on chest CT, specifically significantly faint ground-glass opacities or small nodular opacities that are prone to missed diagnosis and misdiagnosis. Familiarity with the atypical presentations of COVID-19 on CT examination has important reference value for the diagnosis and treatment of COVID-19 and is beneficial for disease screening and epidemic prevention and control when taken together with the patient's travel history, contact history, clinical symptoms, and laboratory examinations.

Author contributions

YZ, BY conceived the idea of the study. YZ, BY, XL-L, YL-L, YJ-D and LZ collected the data.WS-D and WD performed image analysis. BY and YZ wrote the manuscript. YZ performed the statistical analysis. BY and WD edited and reviewed the manuscript. All the authors discussed the results and commented on the manuscript.

Funding

The Program for Cultivating Reserve Talents in Medical Disciplines from the Health Committee of Yunnan Province (H-2018008).

Ethical statement

The Institutional Review Board of Central People's Hospital of Zhanjiang approved this retrospective study and waived requirements for informed consent from the patients.

Conflict of interest

The authors have no conflict of interest to declare.

Footnotes

Peer review under responsibility of Beijing You'an Hospital affiliated to Capital Medical University.

References

- 1.Chung M., Bernheim A., Mei X., Zhang N., Huang M., Zeng X. CT imaging features of 2019 novel coronavirus (2019-nCoV) Radiology. 2020;295(1):202–207. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2020200230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lei J., Li J., Li X., Qi X. CT imaging of the 2019 novel coronavirus (2019-nCoV) pneumonia. Radiology. 2020;295(1):18. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2020200236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Shi H., Han X., Jiang N., Cao Y., Alwalid O., Gu J. Radiological findings from 81 patients with COVID-19 pneumonia in Wuhan, China: a descriptive study. Lancet Infect Dis. 2020;20(4):425–434. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(20)30086-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ai T., Yang Z., Hou H., Zhan C., Chen C., Lv W. Correlation of chest CT and RT-PCR testing in coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) in China: a report of 1014 cases. Radiology. 2020;296(2):E32–E40. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2020200642. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pan F., Ye T., Sun P., Liang B., Li L., Zheng D. Time course of lung changes on chest CT during recovery from 2019 novel coronavirus (COVID-19) pneumonia. Radiology. 2020;295(3):715–721. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2020200370. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zhu N., Zhang D., Wang W., Li X., Yang B., Song J. A novel coronavirus from patients with pneumonia in China,2019. N Engl J Med. 2020;382(8):727–733. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2001017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Huang C., Wang Y., Li X. Clinical features of patients infected with 2019 novel coronavirus in Wuhan, China. Lancet. 2020;395(10223):497–506. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30183-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jin Y.H., Cai L., Cheng Z.S., Cheng H., Deng T., Fan Y. A rapid advice guideline for the diagnosis and treatment of 2019 novel coronavirus (2019-nCoV) infected pneumonia (standard version) Mil Med Res. 2020;7(1):4. doi: 10.1186/s40779-020-0233-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Phan L.T., Nguyen T.V., Luong Q.C., Nguyen T.V., Nguyen H.T., Le H.Q. Importation and human-to-human transmission of a novel coronavirus in Vietnam. N Engl J Med. 2020;382(9):872–874. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc2001272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Koo H.J., Lim S., Choe J., Choi S.H., Sung H., Do K.H. Radiographic and CT features of viral pneumonia. Radiographics. 2018;38(3):719–739. doi: 10.1148/rg.2018170048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Xu Z., Shi L., Wang Y.J., Zhang J., Huang L., Zhang C. Pathological findings of COVID-19 associated with acute respiratory distress syndrome. Lancet. 2020;8(4):420–422. doi: 10.1016/S2213-2600(20)30076-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]