Abstract

Pairing vagus nerve stimulation (VNS) with rehabilitation has emerged as a potential strategy to improve recovery after neurological injury, an effect ascribed to VNS-dependent enhancement of synaptic plasticity. Previous studies demonstrate that pairing VNS with forelimb training increases forelimb movement representations in motor cortex. However, it is not known whether VNS-dependent enhancement of plasticity is restricted to forelimb training or whether VNS paired with other movements could induce plasticity of other motor representations. We tested the hypothesis that VNS paired with orofacial movements associated with chewing during an unskilled task would drive a specific increase in jaw representation in motor cortex compared to equivalent behavioral experience without VNS. Rats performed a behavioral task in which VNS at a specified intensity between 0 and 1.2 mA was paired with chewing 200 times per day for five days. Intracortical microstimulation (ICMS) was then used to document movement representations in motor cortex. VNS paired with chewing at 0.8 mA significantly increased motor cortex jaw representation compared to equivalent behavioral training without stimulation (Bonferroni-corrected unpaired t-test, p < 0.01). Higher and lower intensities failed to alter cortical plasticity. No changes in other movement representations or total motor cortex area were observed between groups. These results demonstrate that 0.8 mA VNS paired with training drives robust plasticity specific to the paired movement, is not restricted to forelimb representations, and occurs with training on an unskilled task. This suggests that moderate intensity VNS may be a useful adjuvant to enhance plasticity and support benefits of rehabilitative therapies targeting functions beyond upper limb movement.

Keywords: Vagus nerve stimulation, orofacial activity, intracortical microstimulation, cortical reorganization, motor cortex

1. Introduction

Vagus nerve stimulation (VNS) paired with rehabilitative training has emerged as a strategy to enhance recovery in the context of a wide range of neurological disorders including stroke, traumatic brain injury, and spinal cord injury [1–7]. Brief bursts of VNS rapidly activate the noradrenergic locus coeruleus (LC) and cholinergic nucleus basalis, two major neuromodulatory centers in the brain [8–13]. Coincident release of these pro-plasticity neuromodulators coupled with neural activity related to rehabilitation facilitates synaptic plasticity in task-specific activated circuits [8,12–15]. This targeted enhancement of plasticity in central networks after injury is believed to underlie VNS-dependent improvements in functional recovery [6,7].

A number of studies demonstrate that repeatedly pairing VNS with forelimb training drives specific reorganization of forelimb movement representations in motor cortex [9,10,16,17]. VNS-mediated plasticity exhibits an inverted-U relationship with stimulation intensity, such that low and high intensities fail to drive plasticity and moderate intensities significantly enhance plasticity [17,18]. This function has been coarsely defined; however, considering the importance of VNS-dependent enhancement of plasticity in its therapeutic effects, a finer delineation of the interaction between stimulation intensity and the magnitude of VNS-dependent plasticity is merited. In the present study, we sought to carefully define the relationship of plasticity at small increments of VNS intensity. Additionally, while the ability of VNS to enhance plasticity in forelimb circuits has been well-documented, VNS-mediated expansion of non-forelimb motor cortex representations has not been evaluated. Movement of the jaw muscles during chewing is a simple, innate motor behavior that represents a testbed for evaluating VNS-dependent plasticity. Here, we sought to leverage this simple behavior and test the hypothesis that VNS paired with orofacial movements associated with chewing would drive a specific increase in jaw representation in motor cortex compared to equivalent behavioral experience without VNS. Rats were trained to perform a simple behavioral task in which either short bursts of VNS at 0.4, 0.6, 0.8, 1.0, 1.2 mA, or sham stimulation were delivered coincident with chewing over the course of five days. After the final day of training, movement representations in motor cortex were assessed with intracortical microstimulation (ICMS). The results from this study provide a framework to develop other VNS-based therapy regimens to target improved recovery beyond upper limb motor function and independently confirm the existence of an inverted-U relationship between VNS intensity and plasticity.

2. Methods

Experimental procedures, statistical comparisons, and exclusion criteria were preregistered before beginning data collection (https://osf.io/594za/).

2.1. Subjects

Fifty-three female Sprague Dawley rats weighing approximately 250 grams and aged approximately 6 months were used in this study (Charles River Labs). All rats were housed in a reversed 12:12 hour light-dark cycle. Rats that underwent behavioral training were food restricted on weekdays during shaping and training with ad libitum access to food on weekends. All rats were maintained at or above 85% body weight relative to their initial weight upon beginning behavioral testing. All handling, housing, stimulation, and surgical procedures were approved by The University of Texas at Dallas Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee.

2.2. Behavioral Training

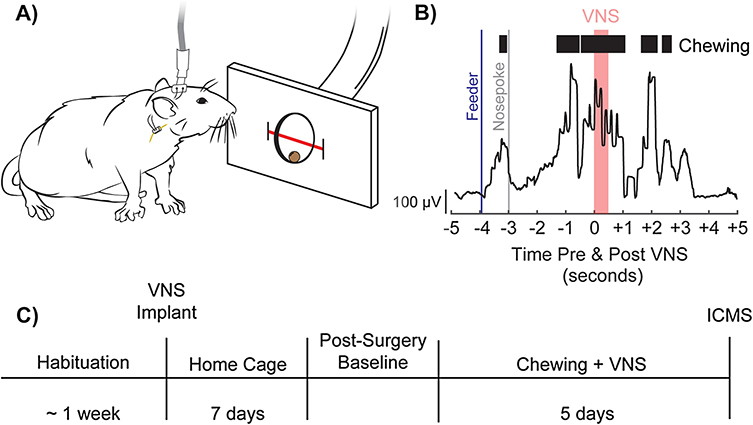

Rats were trained on a simple automated behavioral task that allowed triggering of VNS during chewing and associated orofacial movements involved in eating behavior. The behavioral training apparatus consisted of an acrylic cage with a nosepoke food dispenser at one end (Fig. 1A). A food pellet (45 mg dustless precision pellet, BioServ, Frenchtown, NJ) was delivered to the food dispenser. An infrared beam sensor positioned in the food dispenser was used to determine when the rat entered the nosepoke to retrieve the food pellet. Upon breaking the infrared beam, another pellet was dispensed after an 8 second delay. Each behavioral session continued until either 100 pellets had been dispensed, or until 1 hour had elapsed. Rats received a supplement of 10 grams of food pellets if they did not receive at least 100 pellets in a day to maintain weight.

Figure 1. Behavioral task and experimental design.

(A) Illustration of a rat performing the task. A stimulating cable stimulating cable plugged into a headmount-connector, the subcutaneous stimulation leads and nerve cuff, and the vagus nerve are shown. A feeder dispenses food pellets into a nosepoke and an infrared beam monitors movement into and out of the nosepoke. B) Representative image depicting task performance, superior masseter EMG activity, and the relative timing of pellet dispensal and VNS. C) Experimental timeline.

Rats performed training sessions twice per day, 5 days per week, with daily sessions separated by at least 2 hours until they could reliably consume 100 pellets within 1 hour each session. Rats were then implanted with a VNS cuff and recovered for 7 days in their home cage. Seven days after surgery, rats were allocated to groups to receive 5 days of training paired with either sham stimulation or VNS at varying intensities. Rats in VNS groups received a 500 ms burst of stimulation triggered 3 seconds after nosepoke beam break, which resulted in reliable delivery of VNS during chewing and orofacial movement (Fig. 1B). While this timing scheme was developed to ensure VNS delivery during chewing, eating behavior requires complex coordination of sensorimotor function and many other associated orofacial movements, such as swallowing, and licking, are co-occurring. Here, we will use the term “chewing” to describe the primary action taking place after food pellet retrieval and use the term to encompass all other sensorimotor actions taking place alongside it. At the conclusion of behavioral training, all rats underwent ICMS mapping. Untrained rats were not included as a control group in the current study, as previous reports demonstrate no significant differences in motor cortex representation between naïve and sham animals as a result of behavioral training [9,16].

2.3. Surgical Implantation

All surgeries were performed using aseptic technique under general anesthesia. Rats were implanted with a stimulating cuff on the left cervical vagus nerve as described in previous studies [2–4,17,19]. Rats were deeply anesthetized with ketamine hydrochloride (50 mg/kg, i.p.), xylazine (20 mg/kg, i.p.), and acepromazine (5 mg/kg, i.p.), and were placed in a stereotactic apparatus. Anesthesia level was maintained stably throughout surgery based on assessment of breathing rate, vibrissae whisking, toe pinch reflex, and pulse oximetry. An incision was made down the midline of the head to expose the skull. Bone screws were inserted into the skull at points surrounding the lamboid suture and over the cerebellum. A two-channel connector was mounted to the screws using acrylic. The rat was then removed from the stereotactic apparatus and placed in a supine position.

An incision was made on the left side of the neck and the overlying musculature was blunt dissected to reveal the left cervical vagus nerve. The nerve was gently dissected away from the carotid artery. A cuff electrode was implanted surrounding the vagus nerve, and the leads were tunneled subcutaneously to connect with the two-channel connector mounted on the skull. Nerve activation was confirmed by observation of a ≥ 5% drop in blood oxygen saturation in response to a 10 s stimulation train of VNS consisting of 0.8 mA, 100 μs biphasic pulses at 30 Hz, as in previous studies [17]. The head and neck incisions were then sutured, and rats received subcutaneous injections of 4 mL 50:50 0.9% saline 5% dextrose solution. A seven-day recovery period followed surgery.

2.4. Vagus Nerve Stimulation

After surgery, rats were randomly sorted into groups to receive either VNS at 0.4 mA (n = 3), 0.6 mA (n = 6), 0.8 mA (n = 8), 1.0 mA (n = 6), 1.2 mA (n = 4), or sham stimulation (n = 5) paired with chewing during behavioral training. During behavioral training, all rats, regardless of experimental group, were connected via headmount connector to a stimulation cable. Animals receiving sham stimulation were connected to the cable, but did not receive stimulation. In the initial sessions after implantation, rats were allowed to acclimate to being attached to stimulating cables until they performed at least 100 successful trials per day. Once acclimated, rats then underwent five days of training and received VNS or sham stimulation according to their group. Each 0.5 s stimulation train consisted of a 100 μsec biphasic pulses delivered at 30 Hz at an intensity of either 0.4, 0.6, 0.8, 1.0, or 1.2 mA, as appropriate for each experimental group. VNS was triggered 3 seconds after nosepoke beam break once a pellet had been dispensed during behavioral training, allowing stimulation to be delivered coincident with chewing of the pellet (Fig. 1B). A digital oscilloscope (PicoScope 2204A, PP906, Pico Technology) was used to monitor voltage across the vagus nerve during each stimulation to ensure cuff functionality.

2.5. Electromyography

Electromyography (EMG) was used to evaluate the timing of VNS administration relative to rhythmic jaw movement indicating chewing during behavioral training in a subset of rats. During EMG electrode implantation, rats were anesthetized, mounted in a stereotactic apparatus, and a four-channel headmount-connector was affixed to the skull, as described above for vagus nerve cuff implantation. Two bone screws welded to platinum-iridium leads were inserted in the skull and served as ground and reference connections. A ball electrode on the end of a third platinum iridium lead was tunneled subcutaneously and placed over the left superior masseter. The exposed headmount was encapsulated in acrylic and the skin incision was sutured closed.

During behavioral training, left superior masseter EMG activity was monitored using an amplifier (Model 1700 Differential AC Amplifier, AM-Systems) and a digital oscilloscope (PicoScope 2204A, PP906, Pico Technology) recording at a sampling rate of 10,000 Hz. EMG signals were bandpass filtered offline (Butterworth filter, 100 to 600 Hz) and an envelope detector applied (RMS, 250 ms window). Superior masseter on/off detection was set to a threshold of 300 μV. EMG recording of superior masseter activity was used to assess the accuracy of VNS timing relative to rhythmic jaw movement during chewing after pellet retrieval. A successful VNS pairing was considered to be a stimulation that occurred within two seconds after the onset of superior masseter movement exceeding detection threshold, a window that has been shown to be effective for VNS-mediated plasticity after pairing with a motor activity [7].

2.6. Intracortical Microstimulation Mapping

Within 24 hours of their last behavioral session, rats underwent ICMS to derive functional representation maps according to standard procedures [16,17,20–23]. Rats were anesthetized by intraperitoneal injections of ketamine hydrochloride (75 mg/kg) and xylazine (5 mg/kg) and received supplemental doses of ketamine (25 mg/kg) and xylazine (1.5 mg/kg) as necessary throughout the procedure in order to maintain a consistent level of anesthesia as indicated by breathing rate, vibrissae whisking, and toe pinch reflex. Rats were placed in a stereotactic apparatus and a craniotomy and durotomy were performed to expose the left motor cortex (4 mm to −3 mm AP and 0.25 mm to 5 mm ML). To prevent cortical swelling, a small incision was made in the cisterna magna.

A tungsten electrode with an impedance of approximately 0.7 MΩ (UEWMEGSEBN3M, FHC, Bowdoin, ME) was lowered into the brain to a depth of 1.8 mm, targeting motor outputs in layer V. Stimulation sites were then chosen at random on a grid with sites set 500 μm apart from each other. The next stimulation site was placed at least 1 mm away from the previous site whenever possible. Stimulation consisted of a 40 ms pulse train of 10 monophasic 200 μs cathodal pulses. Stimulation was increased from 10 μA until a movement was observed or until a maximum of 250 μA was reached. ICMS was conducted blinded with two experimenters, as previously described [9,16,17]. The first experimenter placed the electrode and recorded the data for each site. The second experimenter, blinded to group and electrode location, delivered stimulations and classified movements. Movements were classified into the following categories: jaw, neck, vibrissa, proximal forelimb, distal forelimb, and hindlimb. To confirm nerve cuff functionality, nerve activation was confirmed prior to ICMS by observation of a ≥ 5% drop in blood oxygen saturation in response to a 10 s stimulation train of VNS consisting of 0.8 mA, 100 μs biphasic pulses at 30 Hz, following standard procedures [17,24]. This procedure was performed prior to ICMS to avoid risk of damaging the nerve cuff leads during the ICMS surgery. Nerve cuff functionality was assessed in all subjects, regardless of group, and typically preceded ICMS by at least 90 minutes. All raw data from ICMS is available as supplementary material (Fig. S2A–F).

2.7. Subject Exclusion

All exclusion criteria were preregistered before data collection began. Thirty-two subjects were analyzed in the final results of the study out of a total of 53 subjects. Of the 21 subjects not used in final analysis, seven subjects were excluded due to non-functional stimulating cuffs, four subjects were excluded to a lack of drop in blood oxygen saturation in response to VNS, seven subjects were excluded due to mortality during surgical procedures, and three subjects were excluded due to mechanical failure of the headmount during behavioral training. Non-functional stimulating cuffs were identified by digital oscilloscope readings exceeding 40 V peak-to-peak, as in previous studies [17].

2.8. Statistics

Statistical methods and planned comparisons were preregistered and defined a priori. The primary outcome of this study was area of motor cortex generating jaw movements. All other movement representations were analyzed as secondary outcome measures. A one-way ANOVA was used to identify differences across groups. Post hoc Bonferroni-corrected unpaired two-tailed t-tests were used compare between individual groups, as appropriate. Statistical tests for each comparison are noted in the text (Table 1). All data are reported as mean ± SEM.

Table 1. Area of movement representations from ICMS.

Group analysis reveals a significant effect of group in motor cortex jaw representation only. A one-way ANOVA was used to identify differences across groups. Post hoc Bonferroni-corrected unpaired two-tailed t-tests with an alpha of 0.01 were used compare between individual groups, as appropriate. All data is displayed as mean ± SEM in mm2. Bolded results indicate significance.

| Group | Cortical area of movement representation (mm2) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Jaw | Proximal Forelimb | Distal Forelimb | Vibrissae | Neck | Hindlimb | |

| Sham | 1.25 ± 0.22 | 1.95 ± 0.86 | 4.00 ± 0.88 | 1.65 ± 0.68 | 0.15 ± 0.10 | 1.50 ± 0.31 |

| 0.4 mA | 1.08 ± 0.55 | 1.25 ± 0.52 | 4.33 ± 0.79 | 1.17 ± 0.73 | 0.08 ± 0.08 | 1.50 ± 0.38 |

| 0.6 mA | 1.38 ± 0.33 | 0.17 ± 0.12 | 5.46 ± 0.37 | 1.46 ± 0.48 | 0.21 ± 0.16 | 1.54 ± 0.22 |

| 0.8 mA | 2.69 ± 0.27 | 1.13 ± 0.34 | 4.44 ± 0.46 | 2.16 ± 0.74 | 0.25 ± 0.09 | 0.81 ± 0.35 |

| 1.0 mA | 1.75 ± 0.48 | 0.54 ± 0.19 | 4.46 ± 0.63 | 1.21 ± 0.23 | 0.08 ± 0.05 | 1.42 ± 0.42 |

| 1.2 mA | 1.13 ± 0.46 | 1.69 ± 0.58 | 4.94 ± 1.00 | 1.63 ± 0.97 | 0.06 ± 0.06 | 0.63 ± 0.30 |

|

ANOVA Results |

F = 3.1332 p = 0.024 |

F = 2.204 p = 0.084 |

F = 0.637 p = 0.674 |

F = 0.340 p = 0.884 |

F = 0.527 p = 0.753 |

F = 1.279 p = 0.303 |

3. Results

We sought to investigate whether pairing VNS with movement of the jaw and orofacial muscles would enhance jaw representation in motor cortex in an intensity-dependent manner. To do so, rats performed a simple behavioral task in which VNS at varying intensities or sham stimulation was timed to occur during chewing approximately 200 times per day for five days. Assessment of EMG activity in the superior masseter confirmed that VNS delivery occurred within 2 seconds of rhythmic jaw activity on 100% of trials; a time window that has been shown to be effective for VNS-mediated effects [7]. The day following the final day of behavioral training, intracortical microstimulation (ICMS) was used to document movement representations in the motor cortex.

3.1. Moderate intensity VNS paired with chewing increases jaw representation in motor cortex

Group analysis of motor cortex area eliciting jaw movement revealed significant differences between groups (One-way ANOVA, F[5,26] = 3.1332 p = 0.024). Moderate intensity 0.8 mA VNS paired with chewing significantly increased jaw representation compared to equivalent training on the task without VNS (Fig. 2A, Table 1, Unpaired t-test, p = 0.003). This is consistent with previous studies reporting that 0.8 mA VNS enhances training-specific plasticity in cortical networks [9,10,16,17]. No significant differences in jaw representation were observed after unpaired t-tests between sham and 0.4 mA (p = 0.75), 0.6 mA (p = 0.78), 1.0 mA (p = 0.40), or 1.2 mA (p = 0.80) VNS groups (Fig. 2A, Table 1). These results support two conclusions. First, VNS paired with unskilled behavioral tasks can drive robust plasticity in motor cortex. Second, there is a relatively narrow range of stimulation VNS intensities that support cortical plasticity.

Figure 2. VNS paired with chewing and associated orofacial movements enhances jaw-specific plasticity in motor cortex.

(A) 0.8 mA VNS paired with chewing and associated orofacial movements significantly increases jaw movement representation area in motor cortex compared to equivalent behavioral experience without VNS and VNS at 0.4, 0.6, 1.0, and 1.2 mA. (B) No change in total motor cortex area was observed between groups. Bars represent mean ± SEM. “*” indicates p < 0.01.

As expected, no differences in the cortical representation of untrained movements were observed between groups, suggesting that VNS-dependent plasticity is specific to the paired movement (Fig. S1, Table 1). Additionally, consistent with previous studies, total motor cortex area eliciting movements was also not affected by VNS (Fig. 2B; One-way ANOVA, F[5,26] = 0.330, p = 0.890). As expected, group analysis revealed no differences across groups in average stimulation threshold required to elicit movement (One-way ANOVA, F[5,26] = 0.503, p = 0.801). Together, these findings confirm that VNS-mediated plasticity is specific to the paired movement [6,7,9,16,17,25].

3.2. VNS does not alter behavioral performance

Group analysis of the timing between behavioral trials revealed no differences between groups (One-way ANOVA, F[5,26] = 1.437, p = 0.246). Furthermore, group analysis of the number of total stimulations given was not significantly different between groups (One-way ANOVA, F[5,26] = 1.248, p = 0.316). These results suggest that VNS does not alter behavioral performance or motivation and does not influence eating behavior.

4. Discussion

Previous studies demonstrate that repeatedly pairing VNS with a forelimb movement drives targeted motor cortex plasticity [9,10,16,17]. In the present study, we sought to investigate whether closed-loop VNS could be applied during a distinct training paradigm to enhance plasticity of other movement representations. Here, we provide the first report that VNS is able drive robust plasticity when paired with training on an unskilled task emphasizing non-forelimb musculature. This VNS-dependent increase in jaw area occurs in the absence of changes in other representations, indicating that VNS enhances plasticity specific to the trained movement. The findings from this study raise the possibility that VNS may be a useful adjuvant to enhance rehabilitative therapies targeting functions beyond upper limb movement.

Closed-loop VNS has emerged as a strategy to augment the effects of rehabilitation, an effect ascribed to VNS-dependent enhancement of synaptic plasticity [1–7]. Here, we show that pairing VNS with activation of the jaw muscles during chewing enhances plasticity specific to the paired movement. The observation of increased jaw representation in the present study demonstrates that the plasticity-enhancing effects of VNS paired with motor training are not restricted to forelimb movements, but can extend to other motor circuits depending on the training regimen. While forelimb dysfunction is common after stroke, roughly one third of those who undergo a stroke develop a speech aphasia and half will experience dysphagia [26–28]. Previous studies show increases in articulation and speech production in stroke patients with chronic Broca’s aphasia after melodic intonation therapy, as well as increases in perilesional white matter tract plasticity [29]. Cortical plasticity has also been implicated in recovery from dysphagia after stroke [30]. While the present study clearly does not approach the complexity of motor control necessary for speech production or modelling dysphagia, the jaw-related plasticity after VNS pairing reported here raises the possibility that pairing VNS with speech therapy may represent a means to enhance plasticity in networks associated with speech production and swallowing and thereby facilitate rehabilitation.

An inverted-U relationship between VNS intensity and plasticity has been observed previously, but has not been described with the resolution reported here [17,18]. While it has been repeatedly demonstrated that VNS at 0.8 mA is able to increase cortical plasticity and enhance recovery after neurological injury [1–7,9,17], that VNS at a slightly lower 0.6 mA or slightly higher 1.0 mA intensity fails to significantly alter motor cortex plasticity highlights a relatively narrow range of effective parameters. Stimulation intensities above 0.1 mA reliably activate afferent fibers and evoke robust spiking activity in the noradrenergic LC, a neuromodulatory center required for VNS-dependent enhancement of plasticity [8,31]. The absence of plasticity in this study at stimulation intensities well above the threshold to drive LC activity indicates that a particular level of network activation must be reached. However, the failure of higher intensity stimulation to enhance plasticity suggests that over-activation of these networks also prevents plasticity. Moreover, the absence of plasticity at higher stimulation intensities demonstrates that any direct motor or somatosensory activation in response to VNS, such as via activation of the recurrent laryngeal nerve, cannot account for plasticity observed with moderate intensity stimulation and instead is consistent with notion that VNS engages neuromodulatory networks to enhance plasticity. In practical terms, the apparently narrow range of effective VNS intensities observed here calls attention to the need for parameter optimization studies for active stimulation-based therapies.

While the inverted-U relationship between stimulation intensity and VNS-dependent enhancement of plasticity has been repeatedly observed in a number of conditions, the neuronal mechanisms that underlie this relationship are unclear. It is possible that high intensity VNS fails to enhance cortical plasticity due to overactivation and desensitization of relevant neuromodulatory systems [9,10,31]. G-protein coupled receptors for norepinephrine, acetylcholine, and serotonin, all of which are engaged by VNS and required for VNS-dependent plasticity, are known to exhibit profound desensitization [32]. Alternatively, activation of opposing classes of receptors could account for the inverted-U. Increases in VNS intensity drive monotonic increases in LC activation which increases levels of norepinephrine in motor cortex [8]. VNS at low intensities could thus produce activation of high affinity α-adrenergic receptors to support synaptic plasticity. As VNS intensity increases LC activation and subsequently norepinephrine levels, low affinity β-adrenergic receptors would be recruited and oppose the action of the α-adrenergic receptors, thus promoting stability in cortical networks. Under this configuration, moderate intensities of VNS would produce maximal activation of pro-plasticity α-receptors and minimize activation of pro-stability β-receptors. Indeed, the opposing effects of differential activation of noradrenergic receptors on plasticity has previously been described and could account for the findings reported here [17,33,34]. Future studies to delineate the role of these neuromodulatory systems on VNS-dependent plasticity may open avenues for concomitant pharmacological manipulation of VNS effects.

Engagement of different afferent fiber populations represents another potential mechanism underlying the inverted-U relationship of VNS intensity and plasticity. However, several pieces of evidence suggest that engagement of neuromodulatory networks, rather than activation of different fiber populations, determines VNS-dependent plasticity. While the intensities utilized in the present study span much of the range of A- and B-fiber thresholds, the roughly linear relationship of spike activity in the LC and VNS intensity would not be predicted by the approximate step function activation of two fiber types [8,35]. Moreover, a number of previous studies demonstrate that parameters that influence the timing of stimulation, such as frequency and duration, which would not recruit different fiber types, strongly influence the magnitude of VNS-dependent plasticity [36,37]. These features are consistent with a mechanism whereby VNS activates neuromodulatory networks that integrate the intensity and timing of stimulation to determine plasticity. Furthermore, activation of A- and B-fibers during VNS and their subsequent effects on respiration and cardiac function do not appear to predict effective parameters [38]. Still, a reliable biomarker may exist that could be used to predict stimulation parameters that drive plasticity most, and would prove useful to further clinical translation of VNS paired rehabilitation.

While VNS has been demonstrated to support plasticity with both jaw and forelimb-specific training regimens, the anatomy underlying jaw and forelimb movement is divergent. VNS enhances plasticity and recovery for a variety of forelimb tasks utilizing either the proximal or distal forelimb musculature, but the motor output pathways underlying these movements are predominately corticospinal in nature [1,2,4–7,9,16,17,25]. Rhythmic jaw movement can be evoked by a diverse group of brain areas that contribute to masticatory behavior. While descending projections have been traced from jaw motor cortex to the trigeminal motor neurons and pontobulbar reticular formation, several corticobulbar and medullar nuclei are implicated in both central rhythm generation of jaw movements as well as sensory integration and movement correction [39–41]. That these unique pathways appear to have a common mechanism of VNS-mediated plasticity suggests that VNS is highly adaptable at potentiating activated circuits regardless of underlying anatomy. Indeed, VNS-mediated plasticity and enhancement of recovery has been observed in distinct subcortical areas dependent on spared pathways after different levels and totalities of spinal cord injury [7]. VNS-mediated plasticity has also been observed in subcortical auditory nuclei as well as primary auditory cortex after VNS-tone pairing [42]. Together, these findings support a mechanism by which VNS-dependent engagement of neuromodulatory networks acts as a general means to facilitate synaptic plasticity, and the neural activity associated with training that coincides with delivery of VNS, such as rhythmic jaw movement associated with chewing in the present study, dictates the networks that undergo reorganization. Thus, in addition to the reorganization of movement representations in motor cortex, VNS-dependent enhancement of plasticity is likely co-occurring in other networks involved in orofacial sensorimotor function, including the supplemental motor area, cortical masticatory area (CMA), insula, and somatosensory areas as well. Indeed, neuroplasticity in areas such as these after training on both skilled and semi-automatic orofacial tasks has been observed [43,44].

In previous preclinical studies evaluating VNS-dependent enhancement of plasticity, it was necessary to train rats for several weeks to acquire proficiency on a behavioral task before initiating VNS pairing. In this study, however, we describe a VNS-pairing paradigm in which little training is necessary. This substantial reduction in the total amount of time promotes efficient testing, which is critical to studies aimed at parametrically characterizing stimulation parameters that typically require a large number of experimental groups. The robust increase in jaw representation driven by VNS, coupled with the rapid testing afforded by the simple behavioral paradigm, lay a framework for efficient optimization of stimulation parameters, which is necessary to facilitate clinical translation of VNS therapies.

There are a number of limitations in the current study that merit consideration. First, evaluation was restricted to female rats, because VNS and parameters have been extensively validated in this sex [9,16,17,23,25,31]. The use of female rats precludes direct conclusions about sex-specific differences in nerve activation and could potentially be confounded by timing of stimulation during the estrus cycle. While there is no evidence of a sex-specific effect of VNS on the central nervous system in humans [45–47], future studies should incorporate male rats to evaluate any differences in stimulation parameters. Secondly, the present study focused on quantification of gross jaw movement and did not further classify any sub-jaw or other orofacial movement representations. More precise methods, such as EMG, could be used to identify sub-circuit changes in response to VNS pairing. Identification of the specific facial representations that reorganize after VNS paired training on an orofacial task would undoubtedly be useful for assessing the feasibility of using VNS for treating complex disabilities after stroke, such as speech aphasia or dysphagia.

Supplementary Material

Highlights.

Vagus nerve stimulation (VNS) during jaw movement enhances motor cortex plasticity of the jaw.

VNS at low and high intensities during jaw movement fail to enhance motor cortex plasticity.

This small range of effective VNS intensities shows the need to find optimal VNS parameters.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Daniel Hulsey for help with planning and experimental design. We also thank Harshini Rallapalli, Daniel Razick, Madison Stevens, Sarah Jacob, Jennifer Derma, Ariba Hanif, Anjana Swami, Delphi Uthirakulathu, Vikram Ezhil, Kamal Safadi, Alissar Zammam, Abarnaa Vs, Aaron Kuo, Ayushi Bisaria, Yun-Yee Tsang, and Prathima Kandukuri for help with behavioral training and animal care, and Lena Lynn Sadler and Matt Buell for vagus nerve cuff construction. We would also like to thank Katelyn Millay, Eric Meyers, Holle Carey, Andrew Sloan, Jonathan Riley, and Michael Darrow for help developing behavioral programs and testing equipment. We also thank Nikki Simmons for help with artwork.

Sources of Funding

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health R01NS085167 and R01NS094384 and by the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (DARPA) Biological Technologies Office (BTO) Electrical Prescriptions (ElectRx) program under the auspices of Dr. Eric Van Gieson through the Space and Naval Warfare Systems Center, Pacific Cooperative Agreement No. N66001-15-2-4057 and the DARPA BTO Targeted Neuroplasticity Training (TNT) program under the auspices of Dr. Tristan McClure-Begley through the Space and Naval Warfare Systems Center, Pacific Grant/Contract No. N66001-17-2-4011.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest

MPK has a financial interesting in MicroTransponder, Inc., which is developing VNS for stroke.

All other authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- [1].Pruitt DT, Schmid AN, Kim LJ, Abe CM, Trieu JL, Choua C, et al. Vagus Nerve Stimulation Delivered with Motor Training Enhances Recovery of Function after Traumatic Brain Injury. J Neurotrauma 2016;33:871–9. doi: 10.1089/neu.2015.3972. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Khodaparast N, Hays SA, Sloan AM, Hulsey DR, Ruiz A, Pantoja M, et al. Vagus nerve stimulation during rehabilitative training improves forelimb strength following ischemic stroke. Neurobiol Dis 2013;60:80–8. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2013.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Khodaparast N, Hays SA, Sloan AM, Fayyaz T, Hulsey DR, Rennaker RL, et al. Vagus Nerve Stimulation Delivered During Motor Rehabilitation Improves Recovery in a Rat Model of Stroke. Neurorehabil Neural Repair 2014;28:698–706. doi: 10.1177/1545968314521006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Hays SA, Khodaparast N, Ruiz A, Sloan AM, Hulsey DR, Rennaker RL, et al. The timing and amount of vagus nerve stimulation during rehabilitative training affect poststroke recovery of forelimb strength. Neuroreport 2014;25:682–8. doi: 10.1097/WNR.0000000000000154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Hays SA, Ruiz A, Bethea T, Khodaparast N, Carmel JB, Rennaker RL, et al. Vagus nerve stimulation during rehabilitative training enhances recovery of forelimb function after ischemic stroke in aged rats. Neurobiol Aging 2016;43:111–8. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2016.03.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Meyers EC, Solorzano BR, James J, Ganzer PD, Lai ES, Rennaker RL, et al. Vagus Nerve Stimulation Enhances Stable Plasticity and Generalization of Stroke Recovery. Stroke 2018;49:710–7. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.117.019202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Ganzer PD, Darrow MJ, Meyers EC, Solorzano BR, Ruiz AD, Robertson NM, et al. Closed-loop neuromodulation restores network connectivity and motor control after spinal cord injury. Elife 2018;7:1–19. doi: 10.7554/eLife.32058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Hulsey DR, Riley JR, Loerwald KW, Rennaker RL, Kilgard MP, Hays SA. Parametric characterization of neural activity in the locus coeruleus in response to vagus nerve stimulation. Exp Neurol 2017;289:21–30. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2016.12.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Hulsey DR, Hays SA, Khodaparast N, Ruiz A, Das P, Rennaker RL, et al. Reorganization of Motor Cortex by Vagus Nerve Stimulation Requires Cholinergic Innervation. Brain Stimul 2016;9:174–81. doi: 10.1016/j.brs.2015.12.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Hulsey DR. Neuromodulatory pathways required for targeted plasticity therapy. 2018.

- [11].Nichols JA, Nichols AR, Smirnakis SM, Engineer ND, Kilgard MP, Atzori M. Vagus nerve stimulation modulates cortical synchrony and excitability through the activation of muscarinic receptors. Neuroscience 2011;189:207–14. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2011.05.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Dorr AE. Effect of Vagus Nerve Stimulation on Serotonergic and Noradrenergic Transmission. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 2006;318:890–8. doi: 10.1124/jpet.106.104166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Roosevelt RW, Smith DC, Clough RW, Jensen RA, Browning RA. Increased extracellular concentrations of norepinephrine in cortex and hippocampus following vagus nerve stimulation in the rat. Brain Res 2006;1119:124–32. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2006.08.048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Seol GH, Ziburkus J, Huang S, Song L, Kim IT, Takamiya K, et al. Neuromodulators Control the Polarity of Spike-Timing-Dependent Synaptic Plasticity. Neuron 2007;55:919–29. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2007.08.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].He K, Huertas M, Hong SZ, Tie XX, Hell JW, Shouval H, et al. Distinct Eligibility Traces for LTP and LTD in Cortical Synapses. Neuron 2015. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2015.09.037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Porter BA, Khodaparast N, Fayyaz T, Cheung RJ, Ahmed SS, Vrana WA, et al. Repeatedly Pairing Vagus Nerve Stimulation with a Movement Reorganizes Primary Motor Cortex. Cereb Cortex 2012;22:2365–74. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhr316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Morrison RA, Hulsey DR, Adcock KS, Rennaker RL, Kilgard MP, Hays SA. Vagus nerve stimulation intensity influences motor cortex plasticity. Brain Stimul 2018. doi: 10.1016/j.brs.2018.10.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Borland MS, Vrana WA, Moreno NA, Fogarty EA, Buell EP, Sharma P, et al. Cortical Map Plasticity as a Function of Vagus Nerve Stimulation Intensity. Brain Stimul 2016;9:117–23. doi: 10.1016/j.brs.2015.08.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Hays SA, Khodaparast N, Hulsey DR, Ruiz A, Sloan AM, Rennaker RL, et al. Vagus Nerve Stimulation During Rehabilitative Training Improves Functional Recovery After Intracerebral Hemorrhage. Stroke 2014;45:3097–100. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.114.006654. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Kleim JA, Bruneau R, Calder K, Pocock D, VandenBerg PM, MacDonald E, et al. Functional Organization of Adult Motor Cortex Is Dependent upon Continued Protein Synthesis. Neuron 2003;40:167–76. doi: 10.1016/S0896-6273(03)00592-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Neafsey EJ, Sievert C. A second forelimb motor area exists in rat frontal cortex. Brain Res 1982;232:151–6. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(82)90617-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Neafsey EJ, Bold EL, Haas G, Hurley-Gius KM, Quirk G, Sievert CF, et al. The organization of the rat motor cortex: a microstimulation mapping study. Brain Res 1986;396:77–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Pruitt DT, Schmid AN, Danaphongse TT, Flanagan KE, Morrison RA, Kilgard MP, et al. Forelimb training drives transient map reorganization in ipsilateral motor cortex. Behav Brain Res 2016;313:10–6. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2016.07.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Rios M, Bucksot J, Rahebi K, Engineer C, Kilgard M, Hays S. Protocol for Construction of Rat Nerve Stimulation Cuff Electrodes. Methods Protoc 2019. doi: 10.3390/mps2010019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Pruitt DT, Danaphongse TT, Schmid AN, Morrison RA, Kilgard MP, Rennaker RL, et al. Traumatic Brain Injury Occludes Training-Dependent Cortical Reorganization in the Contralesional Hemisphere. J Neurotrauma 2017;34:2495–503. doi: 10.1089/neu.2016.4796. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Engelter ST, Gostynski M, Papa S, Frei M, Born C, Ajdacic-Gross V, et al. Epidemiology of Aphasia Attributable to First Ischemic Stroke. Stroke 2006;37:1379–84. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000221815.64093.8c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Laska AC, Hellblom A, Murray V, Kahan T, Von Arbin M. Aphasia in acute stroke and relation to outcome. J Intern Med 2001;249:413–22. doi: 10.1046/j.13652796.2001.00812.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Permsirivanich W, Tipchatyotin S, Wongchai M, Leelamanit V, Setthawatcharawanich S, Sathirapanya P, et al. Comparing the effects of rehabilitation swallowing therapy vs. Neuromuscular electrical stimulation therapy among stroke patients with persistent pharyngeal dysphagia: A randomized controlled study. J Med Assoc Thail 2009. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Schlaug G, Marchina S, Norton A. Evidence for Plasticity in White-Matter Tracts of Patients with Chronic Broca’s Aphasia Undergoing Intense Intonation-based Speech Therapy. Ann N Y Acad Sci 2009;1169:385–94. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2009.04587.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Barritt AW, Smithard DG. Role of cerebral cortex plasticity in the recovery of swallowing function following dysphagic stroke. Dysphagia 2009. doi: 10.1007/s00455-008-9162-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Hulsey DR, Shedd CM, Sarker SF, Kilgard MP, Hays SA. Norepinephrine and serotonin are required for vagus nerve stimulation directed cortical plasticity. Exp Neurol 2019. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2019.112975. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Gainetdinov RR, Premont RT, Bohn LM, Lefkowitz RJ, Caron MG. Desensitization of G protein-coupled receptors and neuronal functions. Annu Rev Neurosci 2004;27:107–44. doi: 10.1146/annurev.neuro.27.070203.144206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Salgado H, Köhr G, Treviño M. Noradrenergic ‘Tone’ Determines Dichotomous Control of Cortical Spike-Timing-Dependent Plasticity. Sci Rep 2012;2:417. doi: 10.1038/srep00417. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Aston-Jones G, Cohen JD. An integrative theory of locus coeruleus-norepinephrine function: adaptive gain and optimal performance. Annu Rev Neurosci 2005;28:403–50. doi: 10.1146/annurev.neuro.28.061604.135709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].McAllen RM, Shafton AD, Bratton BO, Trevaks D, Furness JB. Calibration of thresholds for functional engagement of vagal A, B and C fiber groups in vivo. Bioelectron Med 2018. doi: 10.2217/bem-2017-0001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Buell EP, Borland MS, Loerwald KW, Chandler C, Hays SA, Engineer CT, et al. Vagus Nerve Stimulation Rate and Duration Determine whether Sensory Pairing Produces Neural Plasticity. Neuroscience 2019. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2019.03.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Buell EP, Loerwald KW, Engineer CT, Borland MS, Buell JM, Kelly CA, et al. Cortical map plasticity as a function of vagus nerve stimulation rate. Brain Stimul 2018;11:1218–24. doi: 10.1016/j.brs.2018.07.045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Bucksot JE, Morales Castelan K, Skipton SK, Hays SA. Parametric characterization of the rat Hering-Breuer reflex evoked with implanted and non-invasive vagus nerve stimulation. Exp Neurol 2020;327:113220. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2020.113220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].Chandler SH, Goldberg LJ. Intracellular analysis of synaptic mechanisms controlling spontaneous and cortically induced rhythmical jaw movements in the guinea pig. J Neurophysiol 1982;48:126–38. doi: 10.1152/jn.1982.48.1.126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].Nakamura Y, Katakura N. Generation of masticatory rhythm in the brainstem. Neurosci Res 1995;23:1–19. doi: 10.1016/0168-0102(95)90003-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [41].Lund JP. Mastication and its Control by the Brain Stem. Crit Rev Oral Biol Med 1991;2:33–64. doi: 10.1177/10454411910020010401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [42].Borland MS, Vrana WA, Moreno NA, Fogarty EA, Buell EP, Vanneste S, et al. Pairing vagus nerve stimulation with tones drives plasticity across the auditory pathway. J Neurophysiol 2019;122:659–71. doi: 10.1152/jn.00832.2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [43].Sessle BJ, Adachi K, Avivi-Arber L, Lee J, Nishiura H, Yao D, et al. Neuroplasticity of face primary motor cortex control of orofacial movements. Arch Oral Biol 2007;52:334–7. doi: 10.1016/j.archoralbio.2006.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [44].Avivi-Arber L, Lee J-C, Yao D, Adachi K, Sessle BJ. Neuroplasticity of face sensorimotor cortex and implications for control of orofacial movements. Jpn Dent Sci Rev 2010;46:132–42. doi: 10.1016/j.jdsr.2009.11.007. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- [45].Dawson J, Pierce D, Dixit A, Kimberley TJ, Robertson M, Tarver B, et al. Safety, Feasibility, and Efficacy of Vagus Nerve Stimulation Paired With Upper-Limb Rehabilitation After Ischemic Stroke. Stroke 2016;47:143–50. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.115.010477. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [46].Kimberley TJ, Pierce D, Prudente CN, Francisco GE, Yozbatiran N, Smith P, et al. Vagus nerve stimulation paired with upper limb rehabilitation after chronic stroke: A blinded randomized pilot study. Stroke 2018. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.118.022279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [47].Elliott RE, Morsi A, Kalhorn SP, Marcus J, Sellin J, Kang M, et al. Vagus nerve stimulation in 436 consecutive patients with treatment-resistant epilepsy: Long-term outcomes and predictors of response. Epilepsy Behav 2011. doi: 10.1016/j.yebeh.2010.10.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.