Abstract

Objectives

Quality and safety of emergency care is critical. Patients rely on emergency medicine (EM) for accessible, timely and high-quality care in addition to providing a ‘safety-net’ function. Demand is increasing, creating resource challenges in all settings. Where EM is well established, this is recognised through the implementation of quality standards and staff training for patient safety. In settings where EM is developing, immense system and patient pressures exist, thereby necessitating the availability of tiered standards appropriate to the local context.

Methods

The original quality framework arose from expert consensus at the International Federation of Emergency Medicine (IFEM) Symposium for Quality and Safety in Emergency Care (UK, 2011). The IFEM Quality and Safety Special Interest Group members have subsequently refined it to achieve a consensus in 2018.

Results

Patients should expect EDs to provide effective acute care. To do this, trained emergency personnel should make patient-centred, timely and expert decisions to provide care, supported by systems, processes, diagnostics, appropriate equipment and facilities. Enablers to high-quality care include appropriate staff, access to care (including financial), coordinated emergency care through the whole patient journey and monitoring of outcomes. Crowding directly impacts on patient quality of care, morbidity and mortality. Quality indicators should be pragmatic, measurable and prioritised as components of an improvement strategy which should be developed, tailored and implemented in each setting.

Conclusion

EDs globally have a remit to deliver the best care possible. IFEM has defined and updated an international consensus framework for quality and safety.

Keywords: quality improvement, safety, risk management, emergency care systems, emergency department

Introduction

Emergency medicine (EM) has been in existence for over 50 years; its rise and spread across the globe occurred through an almost simultaneous development in the International Federation of Emergency Medicine (IFEM) founder nations of Australia, Canada, New Zealand, the USA and the UK.

EDs are increasingly used by patients, who regard them as providing accessible, timely and high-quality healthcare. They also serve an important ‘safety-net’ function when other elements of the healthcare system are, or are perceived to be, deficient. The rise in the use of EDs exceeds population growth and changes in population morbidity.1 There is the potential for a reduction in both the quality and the safety of care, especially if capacity cannot grow to match demand.2 3 The ED may be known by various terms in different jurisdictions including emergency room, A&E, emergency units, receiving room or casualty.

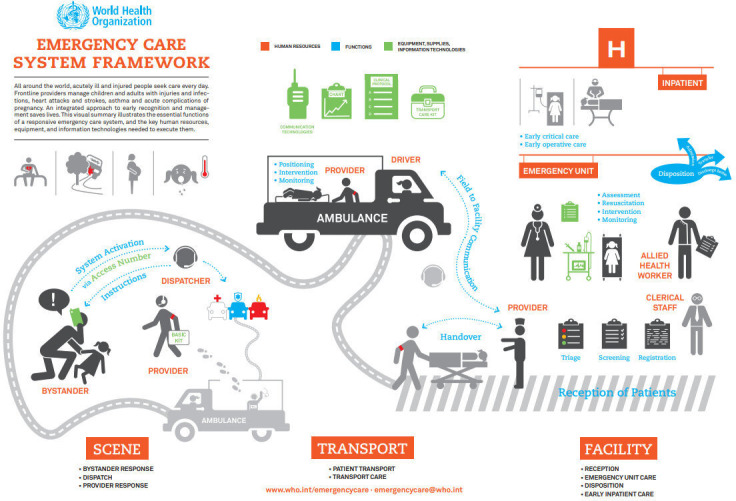

The most important consideration is that the ED cannot function in isolation and commonly exists as the hub of an Emergency Care System Framework (ECSF) (figure 1).4 Developed by the WHO, the ECSF captures essential emergency care functions at the scene of injury or illness, during transport and through the ED to early inpatient care. The ED is a crucial part of the patient care system and necessitates close collaboration with all stakeholders. In May 2019, the World Health Assembly (WHA) passed resolution 72:31 calling on all countries to assess and develop their emergency care systems, in order to ensure timely care for the acutely ill and injured and achieve universal health coverage. A key component for action includes the creation of mechanisms to improve the coordination, quality and safety of emergency care.

Figure 1.

Emergency Care Systems Framework.4

A hospital and community that embraces a culture of quality and patient safety will support the implementation of changes that improve care across the system. In countries where EM is well established, attention is now focused on defining and assuring quality in emergency care, driven by metrics, fiscal resource stewardship, accreditation standards, training status and medico-legal concerns. IFEM members have done extensive work within their own healthcare systems to identify quality in ED care,5–7 applying various measures and promoting these measurements as important to the public and funding bodies. In some countries, there has been mandatory implementation of quality standards or requirements for quality improvement and patient safety training in specialty organisations, associations and colleges.8–10 In countries where EM is emerging, a stepwise approach to tiers of quality measures can be implemented appropriate to the local setting.

Methods

The original ‘Quality Framework’11 document arose from the sessions and discussions that took place at the (IFEM) Symposium for Quality and Safety in Emergency Care, hosted by the College of Emergency Medicine in the UK in 2011. It was presented and further refined at the 14th International Conference on Emergency Medicine in 2012. In 2016, IFEM formed a Quality and Safety Special Interest Group (SIG) which met at its congresses with a remit to respond to the initial framework’s call for evidence concerning successful EM Quality and Safety approaches. At the 2018 meeting, the IFEM Quality and Safety SIG recognised there was sufficient new evidence to develop a second edition framework. Led by the Chair, KH and Deputy Chair, MT, the updated framework was drafted which through iterative email circulations, achieving consensus agreement by the authors. It was approved by the IFEM Board in December 2018.

Results

What patients should expect from an ED

The IFEM terminology Delphi project defines an ED as: “The area of a medical facility devoted to provision of an organized system of emergency medical care that is staffed by Emergency Medicine Specialist Physicians and/or Emergency Physicians and has the basic resources to resuscitate, diagnose and treat patients with medical emergencies”.11 In many countries, trainee doctors, junior doctors, nurses and physician assistants will also staff the ED.

The ED is a unique location at which patients can access emergency care, ideally 24 hours a day, 365 days a year. The ED can manage different types of medical emergencies (illness, injury and mental health) in all age groups. For the general public, the ED is one of the main interfaces of the health service with the community.

Within all countries, patients in an ED should expect the following:

The right personnel

Healthcare staff who are appropriately trained and qualified to deliver emergency care. Key is the early involvement of senior doctors with specific expertise in EM for their ability to resuscitate and stabilise critical patients and to facilitate early referral to appropriate specialities.

The right decision-making

At all levels of ED function, from managerial/administrative levels to the frontline, the importance of critical thinking in decision-making should be recognised and emphasised.

The right processes

To ensure early recognition of those patients requiring immediate attention and prompt time critical interventions and the timely assessment, investigation and management of those with emergency conditions. This will involve appropriate access to and utilisation of diagnostic support services (such as basic pathology and laboratory services and in higher resource settings may include ultrasound, CT and MRI scanning).

The right approach

Patient-centred care with an emphasis on the relief of suffering, good communication and the overall patient (and their accompanying/caring persons) experience. This will lead to optimal outcomes for patients receiving ED treatment.

The right location

A dedicated ED, which is properly equipped (eg, with monitoring equipment, medications and supplies) and provides timely access to necessary investigations to manage the presenting patients. There should be adequate space to provide the necessary patient care in an environment that is secure and promotes patient privacy and dignity; acutely ill and injured patients should not be routinely cared for in hallways or non-equipped overflow spaces. Sometimes it may be prudent for ambulance services to bypass certain EDs to go to a centre, which focuses on time critical conditions such as stroke or trauma. Interhospital transfer of patients will be necessary from all EDs unless every service is on site. The right systems and personnel should be available for safe and timely transfer, after resuscitation and stabilisation with service agreements between the sending and receiving hospitals.

In countries where an EM system is established, patients can also expect:

Expertise in critical care in collaboration with colleagues from anaesthesia and intensive care.

Early access to specialist inpatient and outpatient services to ensure appropriate ongoing evaluation and treatment of patients.

Optimisation of the appropriate duration of stay in the ED to ensure patient care but avoid overcrowding, especially with inpatients.

Development of additional services alongside core ED activity to enhance the quality and safety of emergency care. Such services may include short stay/observation facilities, alternative patient pathways, social and mental health services and/or associated outpatient activity. The system enables timely discharge from the ED or admission to other services or other hospitals and links with the community for ongoing support, such as outpatient services and general practitioners.

Enablers and barriers to quality care

There are multiple aspects of providing care, which are categorised below. Each enabler describes ‘best practice’ and barriers describe factors that may lead to the provision of suboptimal care.

Staff

Trained, qualified and motivated to deliver efficient, effective and timely patient-centred care, compliant with local or national guidelines for ED staffing numbers, including allied health professionals and support staff.

Barriers

Inadequate training or numbers of ED care providers, lack of availability of qualified emergency care providers, staff burn-out, low morale, poor remuneration, inadequate career development opportunities, high turnover, adverse incidents, lack of coordinated teamwork, culture of apathy and weak leadership.

Physical structures

Appropriate size and numbers of rooms for case mix, waiting area, reception, triage and diagnostics, staff and patient washrooms, clean areas with appropriate lighting, heating and privacy, adequate ventilation, clean running water and adequate staff facilities. Fail proof and intuitively designed equipment, including well-stocked consumables and information technology (IT) systems, which are maintained and updated regularly.

Barriers

Lack of dedicated (or shared) space, overflow of patients into corridors/hallways; poor/outdated/poorly maintained equipment and/or supplies due to poor system processes, lack of resources or lack of availability; lack of privacy and dignity; dirty/contaminated facilities; poor flow design and poor hygiene processes.

Access to care

Where ‘universal’ healthcare systems exist (eg, Australia, New Zealand, Canada, the UK, much of Europe) access to EDs and subsequent care is available to citizens. These countries’ citizens are not dependent on the coverage by health insurance or have the ability to pay upfront.

Barriers

For many countries, including some with well-developed healthcare systems, access is dependent on the ability to pay or health insurance coverage. The requirement to travel for care, especially in areas with limited infrastructure, lack of social support or the inability to take time off from employment may also limit treatment options. In many areas around the world, poverty limits access to affordable care or health insurance. While EM providers understand the need for care irrespective of insurance status or the ability to pay, it is often challenging for healthcare leadership or other providers to ‘waive’ the costs. At times, basic care may be provided, but ongoing treatment may not proceed without evidence of the ability to pay. This presents a significant barrier to quality care.

ED processes

There are processes to support effective high-quality care, such as specific triage systems and tools and standard protocols and guidelines for the management of common and high-risk presentations (eg, chest pain, head injury, sepsis, and major trauma).

Barriers

Inadequate consideration of human factors, lack of processes, protocols and guidelines (or poor adherence to any guidelines that do exist), ad hoc or poorly designed systems, weak or absent IT structure, a lack of time to develop and implement processes, or a lack of local data to support the development of country-specific protocols and guidelines.

Coordinated emergency care throughout the patient pathway

A systems approach that begins before the ED and is apparent for the whole patient pathway (healthcare system), with shared ownership and a collaborative approach involving primary or prehospital care and hospital specialists integrated with all components of the care pathway. Much focused endeavour is on ED flow (discharge from or admission to hospital); however, improved ED flow can be perceived as having negative impacts on other areas of organisational care, such as preplanned admissions.

Barriers

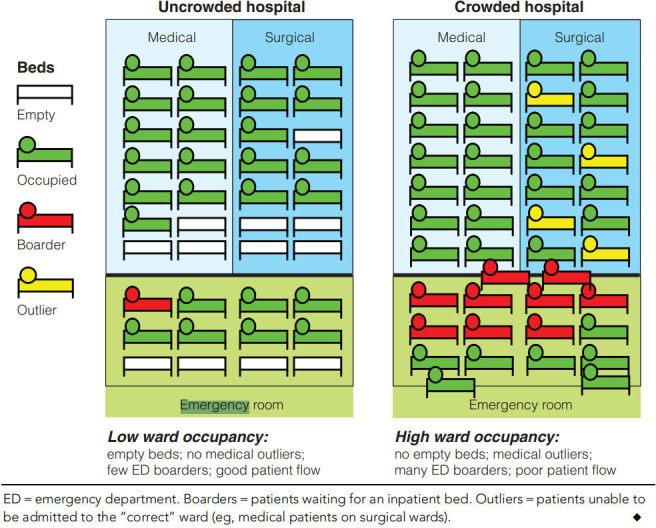

Lack of whole-systems approach and coordination resulting in crowding in the ED, lack of system support for the ED, weak integration with community, prehospital and hospital services, poor or absent design, duplication of processes and equipment. EDs do not control the inflow and outflow, therefore crowding represents a system failure in terms of supply and demand. A crowded hospital(figure 2) impairs multiple aspects of clinical care including time to be seen by ED clinician, ED length of stay, patient flow and appropriate bed allocation. [12] Crowding results in delays for time critical interventions, poor patient and staff experience and avoidable errors.12–21

Figure 2.

Hospital crowding states. Boarders, patients waiting for an inpatient bed. Outliers, patients unable to be admitted to the ‘correct’ ward (eg, medical patients on surgical wards).12 (Permission to reproduce granted by authors.)

Monitoring of outcomes

There must be monitoring and analytic systems, preferably IT-based, that provide informative data on the impact of the above, plus adverse incident reporting, mortality and morbidity review and complaint monitoring to highlight both individual and system failure or success. This should be combined with a programme to actively seek out instances of poor quality or compromised safety and ensure continuous improvement in the ED. In many healthcare systems, this would fit within an overall structure of clinical governance.

Barriers

Lack of monitoring systems and information technology support, weak or absent systems of governance and review, failure to engage with other components of the emergency care pathway, lack of management support, with the ED viewed in isolation.

Quality indicators

Quality indicators should be pragmatic, measurable and centred on current health priorities. Any suite of emergency system indicators must go beyond the ED, to encompass the patient’s entire pathway from prehospital to postdischarge. Resources for data collection and benchmarking are essential to guide standards. There are tools22 and consensus documents23 that can help aid the selection of appropriate quality indicators. Standardisation of EM datasets and definitions enables comparison across different environments. A widely adopted approach to standardise reporting and to determine the applicability and clinical relevance of scholarly findings has been the development and implementation of Utstein-style guidelines. There is a template for uniform reporting of standardised measures of the care provided in the ED. This will allow comparison between systems (and is particularly pertinent with respect to quality indicators) to enable better translation and interpretation of systems between settings.24

The Institute of Medicine framework encompasses IFEM’s aspiration of “right patient to the right clinician at the right time in the right setting”.11 The six domains25 cover a range of issues that are fundamental to the delivery of high-quality care in any ED but the exact measures used will depend on local factors, the availability of data and overarching elements of the healthcare system (figure 3). A series of quality domains and their associated quality measures under a structure, process and outcome framework is shown in table 1.

Figure 3.

Institute of Medicine domains of ‘high quality care’.

Table 1.

Suggested indicators for EDs, grouped by the domains of structure, process and outcome to address the six Institute of Medicine domains of ‘high quality care’

| Domain | Structure | Process | Outcome |

| Safe |

Clinicians with the right skill mix

Adequate and appropriate assessment spaces Adequate security |

Reporting system for safety concerns (without fear of reprisal) Ability to share and learn from adverse incidents Administration acts on staff concerns |

Analysis of incident reports (there should be many non-serious incidents and a few serious incidents) Incidence of hospital-acquired infection, medication errors, violent incidents |

| Effective |

Adequate assessment spaces

Sufficient equipment Adequate and effective monitoring Disaster/major incident plan |

Care standards or evidence-based guidelines for common and important presentations available Quality improvement activity being conducted |

Audit performance against international, national or local standards for common presentations, such as sepsis or multiple injuries Morbidity/Mortality (general or specified conditions)29 Hospitalised Standard Mortality Ratio 30 Diagnostic and procedural errors |

| Patient-centred |

Structural environment allows for privacy and dignity Dedicated areas for vulnerable groups (eg, children, mentally ill, elderly) |

Patient complaint system (with follow-up actions) Left without being seen rate |

Patient experience

Patients’ ability to participate in own care Collection and use of patient-reported outcomes Time to analgesia audit |

| Timely |

Ambulance notification system

Adequate clinicians to initially assess a patient promptly |

Patients seen initially by a clinician trained in triage

Time to consultation by doctor Time to be seen by decision maker Patients needing admission are moved swiftly out of the ED |

Total length of stay in the ED (from arrival to departure) Percentage of patients who leave the ED without being seen |

| Efficient | Emergency clinicians available who can assess and provide initial treatment for all emergency presentations, regardless of age or pathology | Patients investigated and treated according to evidence-based guidelines

Appropriate use of investigations Appropriate and timely support from other specialities |

Number of admissions from the ED Avoidable patient re-presentations to the ED Good communication with other healthcare providers |

| Equitable | ED available to all patients who need it, 24/7, regardless of age, disease or finances | Patients seen in order of clinical priority |

Comparable access and clinical outcomes despite:

|

Key activities that develop and maintain quality and safety in EDs include:

Audits—a structured process of quality assurance to compare, benchmark and prioritise by reviewing what is happening in EDs compared with what should be occurring. The use of audit information should be used to guide processes of review with the focus of ongoing improvement.26

Incident Monitoring—a system in which the staff and patients can report concerns in an efficient manner without fear of reprisal, in which the results are analysed and acted on. Speciality-specific systems, such as the Emergency Medicine Events Register, is a good example of this.27 28

Guidelines which are complete (covers all ED scenarios and conditions), accessible (easy to use interface, guided by intuition, logically arranged), practical and relevant to local patients.

Morbidity and mortality review with multidisciplinary attendance in a blame-free setting so learning can be maximised.29

Integration and communication with ambulance, hospital specialities and primary care.

Discussion

All EDs have an obligation to deliver care that is demonstrably safe and of the highest possible quality. The IFEM has defined a framework for quality and safety in the ED. It sets out expectations for patients attending any ED globally and the additional expectations for EDs functioning in a developed healthcare system.

Patients or the public were not involved in the design, development, reporting or dissemination plans of the updated quality framework. This may be seen as a limitation for this work. Although patients are central to our EM work, this high-level consensus is aimed at a health system perspective from a variety of providers and leaders. Patient contribution will be crucial when this document is implemented at the local level and patient experience can be leveraged in a more meaningful and direct way. It is envisaged that with the implementation of the framework, the patient experience information will be necessary to plan for quality and patient safety improvement processes.

The enablers and barriers to quality care in the ED can be considered under a series of headings. A number of quality indicators have been proposed to allow measurement. There is an urgent need to improve the evidence base to determine which quality indicators have the potential to successfully improve clinical outcomes, staff and patient experience in a cost-efficient manner and to develop indicators that will guide practice improvement. It is hoped that this framework will provide a common consensus to underpin the pursuit of quality and safety in all EDs globally, thereby improving the outcome and experience of emergency patients and our staff worldwide. To achieve these goals, access to and the provision of emergency care must be a priority for healthcare systems at local, regional and national level and the recent WHA resolution provides this impetus. The next focus needs to be on transition from consensus-based quality measures. Global implications from the completion of international research projects would support this stewardship.

Acknowledgments

We would like to acknowledge the editors of the 2012 Framework for Quality and Safety in the Emergency Department: Drs Fiona Lecky, Jonathan Benger, Suzanne Mason, Peter Cameron and Chris Walsh. We would also like to thank Associate Professor Katie Walker who greatly assisted with manuscript review and preparation.

Footnotes

Handling editor: Ellen Weber

Twitter: @hansendisease

Collaborators: IFEM Quality and Safety Special Interest Group: Katie Walker.

Contributors: KH: initiated the concept, organised the group, developed the first draft, contributed to writing and review of manuscript, developed the tables and images, prepared manuscript for submission, led the revision. MT: assisted with planning of the document, developed the first draft with KH, contributed to writing and performed thorough and multiple reviews of the manuscript, assisted with preparation of tables, prepared manuscript for submission. AB: contributed to writing and review of manuscript. BH: contributed to writing and review of manuscript. GP: contributed to writing and review of manuscript. JB: contributed to writing and review of manuscript, author of the first edition. LBC: contributed to writing and review of manuscript. FL: contributed to writing and review of manuscript, author of the first edition. SV: contributed to writing and review of manuscript. PC: contributed to writing and review of manuscript, author of the first edition. GW: contributed to writing and review of manuscript. LK: contributed to writing and review of manuscript.

Funding: The authors have not declared a specific grant for this research from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: Professor Jonathan Benger is an Emergency Physician in the UK and is the acting Chief Medical Officer for NHS Digital, the national information and technology partner to the health and care system in England. Dr Kim Hansen is Chair of the Board of the Emergency Medicine Foundation in Australia.

Patient and public involvement: Patients and/or the public were not involved in the design, or conduct, or reporting, or dissemination plans of this research.

Patient consent for publication: Not required.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data availability statement: Data sharing not applicable as no datasets generated and/or analysed for this study.

Author note: This paper is derived from the 2018 Update Quality Framework document available from the International Federation for Emergency Medicine resources library at https://www.ifem.cc/wpcontent/uploads/2019/05/An-Updated-Framework-on-Quality-and-Safety-in-Emergency-MedicineJanuary-2019.pdf.

Contributor Information

IFEM Quality and Safety Special Interest Group:

References

- 1. Lowthian JA, Curtis AJ, Jolley DJ, et al. Demand at the emergency department front door: 10-year trends in presentations. Med J Aust 2012;196:128–32. 10.5694/mja11.10955 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Richardson DB, Mountain D. Myths versus facts in emergency department overcrowding and hospital access block. Med J Aust 2009;190:369–74. 10.5694/j.1326-5377.2009.tb02451.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Pines JM, Hilton JA, Weber EJ, et al. International perspectives on emergency department crowding. Acad Emerg Med 2011;18:1358–70. 10.1111/j.1553-2712.2011.01235.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. World Health Organization Emergency care systems framework. Available: https://www.who.int/emergencycare/emergencycare_infographic/en/ [Accessed 4 Aug 2019].

- 5. Health Quality Ontario Emergency department return visit quality program [Internet]. Available: http://www.hqontario.ca/Quality-Improvement/Quality-Improvement-in-Action/Emergency-Department-Return-Visit-Quality-Program [Accessed 15 Jul 2019].

- 6. Cameron PA, Schull MJ, Cooke MW. A framework for measuring quality in the emergency department. Emerg Med J 2011;28:735–40. 10.1136/emj.2011.112250 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Keroack MA, Youngberg BJ, Cerese JL, et al. Organizational factors associated with high performance in quality and safety in academic medical centers. Acad Med 2007;82:1178–86. 10.1097/ACM.0b013e318159e1ff [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Centres for Medicare and Medicaid services National Impact Assessment of the Centres for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) Quality Measures Reports [Internet], 2012. Available: https://www.cms.gov/medicare/quality-initiatives-patient-assessment-instruments/qualitymeasures/national-impact-assessment-of-the-centers-for-medicare-and-medicaid-services-cms-quality-measures-reports.html [Accessed 15 Jul 2019].

- 9. Frank J, Snell L, Sherbino J. CanMEDS 2015 Physician Competency Framework [Internet], 2015. Available: http://canmeds.royalcollege.ca/uploads/en/framework/CanMEDS2015Framework_EN_Reduced.pdf [Accessed 15 Jul 2019].

- 10. Newell R, Slesinger T, Cheung D, et al. Emergency Medicine Quality Measures [Internet]. ACEPNow, 2012. Available: https://www.acepnow.com/article/emergency-medicine-quality-measures/ [Accessed 15 Jul 2019].

- 11. Lecky F, Benger J, Mason S, et al. The International Federation for emergency medicine framework for quality and safety in the emergency department. Emerg Med J 2014;31:926–9. 10.1136/emermed-2013-203000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Sprivulis PC, Da Silva J-A, Jacobs IG, et al. The association between hospital overcrowding and mortality among patients admitted via Western Australian emergency departments. Med J Aust 2006;184:208–12. 10.5694/j.1326-5377.2006.tb00203.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Ackroyd-Stolarz S, Read Guernsey J, Mackinnon NJ, et al. The association between a prolonged stay in the emergency department and adverse events in older patients admitted to hospital: a retrospective cohort study. BMJ Qual Saf 2011;20:564–9. 10.1136/bmjqs.2009.034926 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Schull MJ, Vermeulen M, Slaughter G, et al. Emergency department crowding and thrombolysis delays in acute myocardial infarction. Ann Emerg Med 2004;44:577–85. 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2004.05.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Carter EJ, Pouch SM, Larson EL. The relationship between emergency department crowding and patient outcomes: a systematic review. J Nurs Scholarsh 2014;46:106–15. 10.1111/jnu.12055 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Pines JM, Hollander JE. Emergency department crowding is associated with poor care for patients with severe pain. Ann Emerg Med 2008;51:1–5. 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2007.07.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Fee C, Weber EJ, Maak CA, et al. Effect of emergency department crowding on time to antibiotics in patients admitted with community-acquired pneumonia. Ann Emerg Med 2007;50:501–9. 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2007.08.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Diercks DB, Roe MT, Chen AY, et al. Prolonged emergency department stays of non-ST-segment-elevation myocardial infarction patients are associated with worse adherence to the American College of Cardiology/American heart association guidelines for management and increased adverse events. Ann Emerg Med 2007;50:489–96. 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2007.03.033 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Richardson DB. Increase in patient mortality at 10 days associated with emergency department overcrowding. Med J Aust 2006;184:213–6. 10.5694/j.1326-5377.2006.tb00204.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Pines JM, Hollander JE, Localio AR, et al. The association between emergency department crowding and hospital performance on antibiotic timing for pneumonia and percutaneous intervention for myocardial infarction. Acad Emerg Med 2006;13:873–8. 10.1197/j.aem.2006.03.568 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Hwang U, Richardson LD, Sonuyi TO, et al. The effect of emergency department crowding on the management of pain in older adults with hip fracture. J Am Geriatr Soc 2006;54:270–5. 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2005.00587.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Jones P, Shepherd M, Wells S, et al. Review article: what makes a good healthcare quality indicator? A systematic review and validation study. Emerg Med Australas 2014;26:113–24. 10.1111/1742-6723.12195 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Broccoli MC, Moresky R, Dixon J, et al. Defining quality indicators for emergency care delivery: findings of an expert consensus process by emergency care practitioners in Africa. BMJ Glob Health 2018;3:e000479 10.1136/bmjgh-2017-000479 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Hruska K, Castrén M, Banerjee J, et al. Template for uniform reporting of emergency department measures, consensus according to the Utstein method. Eur J Emerg Med 2019;26:417–22. 10.1097/MEJ.0000000000000582 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Leavitt M, Wolfe A. Medscape's response to the Institute of medicine report: crossing the quality chasm: a new health system for the 21st century. MedGenMed 2001;3:2. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Canadian Association of Emergency Physicians Quality improvement and patient safety (QIPS) Resources [Internet], 2018. Available: https://caep.ca/qips-resources/ [Accessed 15 Jul 2019].

- 27. Schultz TJ, Crock C, Hansen K, et al. Piloting an online incident reporting system in Australasian emergency medicine. Emerg Med Australas 2014;26:461–7. 10.1111/1742-6723.12271 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Hansen K, Schultz T, Crock C, et al. The emergency medicine events register: an analysis of the first 150 incidents entered into a novel, online incident reporting registry. Emerg Med Australas 2016;28:544–50. 10.1111/1742-6723.12620 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Calder LA, Kwok ESH, Adam Cwinn A, et al. Enhancing the quality of morbidity and mortality rounds: the Ottawa M&M model. Acad Emerg Med 2014;21:314–21. 10.1111/acem.12330 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Berthelot S, Lang ES, Quan H, et al. Development of a hospital standardized mortality ratio for emergency department care. Ann Emerg Med 2016;67:517–24. 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2015.08.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]