Abstract

Minor salivary gland tumours represent 9–25% of all salivary gland tumours. South African epidemiological reports on minor salivary gland tumours are lacking. This study aims to evaluate the frequency, epidemiology and histology of minor salivary gland tumours in a defined South African population from 1997 to 2016. This cross sectional retrospective review of epithelial minor salivary gland neoplasms recorded patient demographic data: prevalence, age, gender, site, histology. There were 553 benign (57%) and malignant (43%) minor salivary gland tumours, in patients between the ages of 9 and 93 years. There was no significant age (p = 0.64) or gender (p = 0.18) difference between males and females. Common histologic types of salivary gland tumours in the continually evolving spectrum were pleomorphic adenoma (52%), adenoid cystic carcinoma (12%) and mucoepidermoid carcinoma (10%). Common sites were the palate (56%), cheek (11%), lip (9%) and paranasal sinuses (7%). Minor salivary gland tumours represent 2.3% of head and neck pathology. Although this prevalence is higher than reported, there is no overall increase in number diagnosed per year. Minor salivary gland tumours were more prevalent in females. Benign tumours occurred at a younger age than malignant tumours. This study serves as a baseline for future studies, especially in South Africa.

Keywords: Benign, Malignant, Minor, Salivary gland, Tumours, Neoplasia

Introduction

Salivary gland tumors (SGTs) are uncommon; with epithelial SGTs representing 2–6% of head and neck neoplasms [1–6]. They predominantly affect major salivary glands, especially the parotid gland, in which 80% are benign. Whilst most major SGTs are benign, the inverse is true for minor SGTs, with 80% being malignant [7].

Minor SGTs are uncommon, accounting for 9–25% of all SGTs [1–19]. Even though rare, there is a recent rise in the number of minor SGTs diagnosed and treated in the Department of Otorhinolaryngology, University of the Witwatersrand.

Whilst there are many global epidemiological reports on minor SGTs, there is a dearth in the literature on the frequency and distribution of minor SGTs in Africa, and especially South Africa. Most studies report a combined prevalence of major and minor SGTs, and do not separate their prevalence. This study provides an insight to the frequency and clinico-pathologic demographics of minor SGTs within a defined South African population in Johannesburg over a 20-year period.

Materials and Methods

Sample

This cross-sectional retrospective study (Ethics clearance: 170130) included data of patients diagnosed with benign and malignant minor SGTs in the Department of Oral Pathology, University of the Witwatersrand, Johannesburg, South Africa between January 1997 and December 2016. Demographic data included age, gender, site, and histologic diagnosis of patients with primary epithelial SGTs diagnosed as per the 2005 WHO Classification of SGTs (Table 1) [20]. Diagnosis was confirmed via histologic and immunohistochemical descriptions from histopathology reports. Tumors were not reviewed histologically, and were not reclassified according to recent, continually evolving SGT classifications.

Table 1.

WHO histological classification of epithelial tumours of the salivary gland [20]

| Malignant epithelial tumors | Benign epithelial tumors |

|---|---|

| Acinic cell carcinoma | Pleomorphic adenoma |

| Mucoepidermoid carcinoma | Myoepithelioma |

| Adenoid cystic carcinoma | Basal cell adenoma |

| Polymorphous low-grade adenocarcinoma (PLGA) | Warthin tumor |

| Epithelial-myoepithelial carcinoma | Oncocytoma |

| Clear cell carcinoma (NOS) | Canalicular adenoma |

| Basal cell adenocarcinoma | Sebaceous adenoma |

| Sebaceous carcinoma | Lymphadenoma |

| Sebaceous lymphadenocarcinoma | Sebaceous |

| Cystadenocarcinoma | Non-sebaceous |

| Low-grade cribriform cystadenocarcinoma | Ductal papillomas |

| Mucinous adenocarcinoma | Inverted ductal papilloma |

| Oncocytic carcinoma | Intraductal papilloma |

| Salivary duct carcinoma | Sialadenoma papilliferum |

| Adenocarcinoma (NOS) | Cystadenoma |

| Myoepithelial carcinoma | |

| Carcinoma ex pleomorphic adenoma | |

| Carcinosarcoma | |

| Metastasizing pleomorphic adenoma | |

| Squamous cell carcinoma | |

| Small cell carcinoma | |

| Large cell carcinoma | |

| Lymphoepithelial carcinoma | |

| Sialoblastoma |

It is important to be cognizant of the recent change in SGT terminology. Primary malignant epithelial SGTs included in the latest WHO classification (2017) include secretory carcinoma, intraductal carcinoma and poorly differentiated carcinoma [21]. Polymorphous low-grade adenocarcinoma (PLGA) is now termed polymorphous adenocarcinoma [21]. SGT classification is dynamic, and with advances in immunohistochemistry and the application of fluorescence in situ hybridization for molecular cytogenetic analysis, specific and refined changes continue to unfold.

This retrospective analysis of minor SGTs between 1997 and 2016 included only primary epithelial SGTs as classified by the WHO in 2005 (Table 1) [20].

Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

The study included SGTs with available histology results. It excluded patients with non-epithelial SGTs, metastatic, hematolymphoid and soft tissue tumors, and patients with incomplete records.

Statistical Analysis

Recorded data stored in Microsoft® Excel® spreadsheets was analyzed by standard statistical methods such as counts, frequency tables, and proportions described categorical variables. Age, a continuous variable, was analyzed with a t test. A Chi squared test analyzed the association between the subtypes and other variables. A multivariate logistic regression analysis (ANOVA) assessed the association between tumor types and other variables to control for confounders. A p value of < 0.05 was significant.

Results

Study Sample and Prevalence

Of 23,884 cases diagnosed during the 20-year period, there were 1275 (5.3%) SGTs, of which 553 (2.3%) were minor SGTs (Table 2, Fig. 1). The final sample was limited to 1247 SGTs as 28 cases had incomplete data.

Table 2.

Number and percentage of minor SGTs per annum from 1997-2016

| Year | Overall oral pathology diagnoses (n) | Minor SGTs | |

|---|---|---|---|

| N | % | ||

| 1997 | 636 | 27 | 4.24 |

| 1998 | 442 | 15 | 3.39 |

| 1999 | 1066 | 24 | 2.25 |

| 2000 | 1134 | 26 | 2.29 |

| 2001 | 1184 | 25 | 2.11 |

| 2002 | 1382 | 29 | 2.09 |

| 2003 | 1477 | 30 | 2.03 |

| 2004 | 1380 | 33 | 2.39 |

| 2005 | 1294 | 34 | 2.62 |

| 2006 | 1086 | 28 | 2.58 |

| 2007 | 1004 | 24 | 2.39 |

| 2008 | 1124 | 22 | 1.95 |

| 2009 | 1618 | 40 | 2.47 |

| 2010 | 1471 | 23 | 1.56 |

| 2011 | 1788 | 30 | 1.67 |

| 2012 | 1561 | 32 | 2.04 |

| 2013 | 1294 | 31 | 2.39 |

| 2014 | 812 | 31 | 3.81 |

| 2015 | 877 | 29 | 3.30 |

| 2016 | 1524 | 20 | 1.31 |

| Total | 23,884 | 553 | 2.31 |

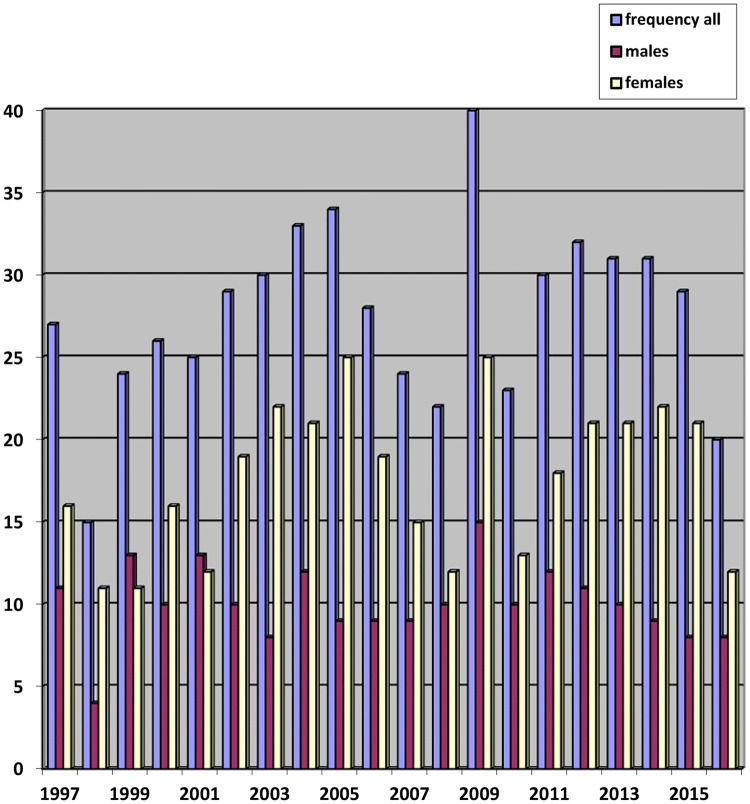

Fig. 1.

Annual frequency per year of minor SGTs

Prevalence of Minor SGTs

Figure 1 depicts the prevalence of minor SGTs, which included 553 (2.3%) minor SGTs, of which 315 (57%) were benign and 238 (43%) were malignant. The number of minor SGTs per year ranged from 15 to 40 cases (mean 27.65), the greatest number of cases seen in 2009.

Demographic Data

Minor SGTs occurred in patients between 9 and 93 years (44.1 ± 17.8 years; mean ± SD). There was no statistically significant difference in age between males (44.56 ± 17.73 years; mean ± SD) and females (43.82 ± 17.98 years; mean ± SD) with minor SGTs (p = 0.64). There was a statistically significant difference in patient age for benign (39.76 ± 17.46 years; mean ± SD) and malignant (49.81 ± 16.68 years; mean ± SD) minor SGTs (p = 0.00). Association between age and whether the minor SGT was benign or malignant was significant for both females and males, (p < 0.05). Across both genders, malignant tumors occurred in older patients.

There were 193 (54.8%) and 122 (60.7%) benign and 159 (45.2%) and 79 (39.3%) malignant minor SGTs in females and males respectively. Gender differences were not statistically significant (p = 0.18), despite there being a larger proportion of females with minor SGTs.

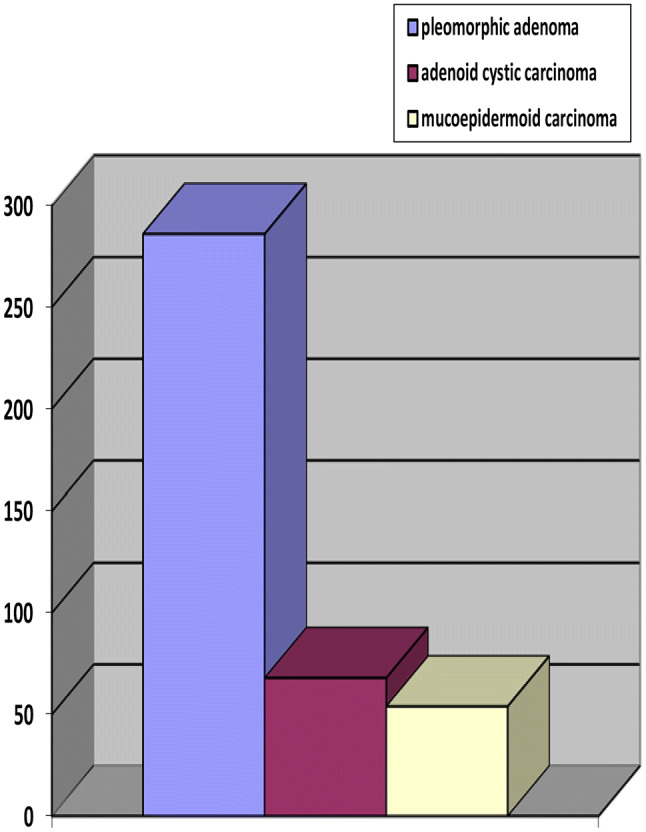

The three most common minor SGT histologic types were pleomorphic adenoma (n = 287; 51.9%), adenoid cystic carcinoma (n = 71; 12.8%) and mucoepidermoid carcinoma (n = 58; 10.5%). The three most common histologic types in males and females respectively were pleomorphic adenoma (n = 114; 39.7%; n = 173; 60.3%), adenoid cystic carcinoma (n = 21; 8.8%; n = 47; 14.9%) and mucoepidermoid carcinoma (n = 18; 7.6%; n = 37; 11.7%) (Fig. 2). The benign to malignant minor SGT ratio was higher for males than females; female patients were more likely to have malignant tumors.

Fig. 2.

Most common minor SGT histological types

The four most common sites for minor SGTs were the palate (56%), cheek (11.2%), lip (8.9%) and paranasal sinuses (7.4%). In both genders, minor SGTs occurred in all sites including hard palate, soft palate, and palate not otherwise specified as hard or soft palate (NOS) (Table 3).

Table 3.

Anatomical distribution and histology of minor SGTs

| Histologic type | FOM | Hard palate | Soft palate | Palate (NOS) | Cheek | Lip | Tongue | Sinuses | Other | Total (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M (%) | F (%) | ||||||||||

| Benign | 315 (57) | ||||||||||

| 122 (60.7) | 193 (54.8) | ||||||||||

| Pleomorphic adenoma | 0 | 78 | 25 | 93 | 19 | 28 | 1 | 9 | 34 | 287 (51.9) | |

| 114 (39.7) | 173 (60.3) | ||||||||||

| Myoepithelioma | 0 | 3 | 2 | 3 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 13 | |

| Canalicular adenoma | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 2 | 7 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 11 | |

| Cystadenoma | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 3 | |

| Malignant | 173 (60.3) | ||||||||||

| 79 (39.3) | 159 (45.2) | ||||||||||

| Acinic cell carcinoma | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 9 | 5 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 16 | |

| Mucoepidermoid carcinoma | 0 | 10 | 3 | 16 | 10 | 0 | 8 | 3 | 8 | 58 (10.5) | |

| 18 (7.6) | 37 (11.7) | ||||||||||

| Adenoid cystic carcinoma | 3 | 18 | 4 | 13 | 3 | 2 | 4 | 15 | 9 | 71 (12.8) | |

| 21 (8.8) | 47(14.9) | ||||||||||

| PLGA | 0 | 13 | 3 | 9 | 12 | 4 | 1 | 6 | 4 | 52 (9.4) | |

| Epithelial-myoepithelial carcinoma | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | |

| Basal cell adenocarcinoma | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | |

| Salivary duct carcinoma | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | |

| Adenocarcinoma (NOS) | 1 | 3 | 1 | 4 | 3 | 1 | 0 | 2 | 4 | 19 | |

| Myoepithelial carcinoma | 0 | 2 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 4 | 0 | 8 | |

| Carcinoma ex pleomorphic adenoma | 0 | 1 | 2 | 4 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 12 | |

| Total | 4 | 129 | 41 | 145 | 61 | 49 | 16 | 41 | 67 | 553 | |

| 201 (36.3) | 352 (63.7) | ||||||||||

FOM floor of mouth, NOS not otherwise specified

In men, benign SGTs were more prevalent than malignant SGTs in the hard palate (68.9%), soft palate (76.5%) and palate (NOS) (69%), and less common in the remaining minor salivary glands (46.9%). Association between age and benign/malignant tumors was not significant for the hard palate (p = 0.441), soft palate (p = 0.122), and palate (NOS) (p = 0.143), but was significant in other minor salivary glands (p < 0.05). Most SGTs of the hard palate occurred between 41 and 60 years, and most in soft palate and palate (NOS) were benign and occurred between 21 and 40 years, whereas more between 61 and 80 years were malignant. SGTs of the soft palate did not occur in males < 20 years. Most tumors of the remaining minor salivary glands occurred in patients < 40 years and were benign, whereas tumors between 41 and 80 + years were more likely malignant.

In females, benign SGTs were more prevalent than malignant SGTs in the hard palate (61.9%), soft palate (62.5%) and palate (NOS) (66.3%), and less common in other minor salivary glands (43.7%). Association between age and benign/malignant tumors in the hard palate (p < 0.05), palate (NOS) (p < 0.05) and other minor salivary glands (p < 0.05) was significant. It was not significant in the soft palate (p = 0.315). Benign tumors of the hard palate were more common in females < 20 years. In the soft palate, most tumors occurred between 21 and 40 years and most were benign, whereas most between 41 and 80 + years were more likely malignant. Most tumors in the palate (NOS) < 40 years were benign whereas more tumors between 41 and 81 + years were malignant. In other minor salivary glands, more tumors between 21 and 60 years and those over 80 years were malignant.

In males, the three most common minor SGT types of the hard and soft palate respectively were pleomorphic adenoma (66.7%; 76.5%), adenoid cystic carcinoma (13.3%; 11.8%) and PLGA (8.9%; 5.9%). The three most common tumors of the palate (NOS) and other minor salivary gland sites were pleomorphic adenoma (67.2%; 35.2%), mucoepidermoid carcinoma (8.6%; 11%) and adenoid cystic carcinoma (6.9; 9.9%). In females, the three most common minor SGT types in the hard palate were pleomorphic adenoma (57.1%), adenoid cystic carcinoma (11.9%) and mucoepidermoid carcinoma (9.5%). The three most common minor SGT types in the soft palate were pleomorphic adenoma (50%), mucoepidermoid carcinoma (12.5%) and PLGA/adenoid cystic carcinoma (8.3%), and in the palate (NOS) pleomorphic adenoma (62.8%), mucoepidermoid carcinoma (11.6%) and adenoid cystic carcinoma (10.5%). The three most common tumours of the remaining minor salivary glands were pleomorphic adenoma (39.5%), adenoid cystic carcinoma (18.4%) and PLGA (14.3%).

Discussion

The prevalence of minor SGTs over the 20-year period was 2.3% (n = 553). The mean number/year was 27.65; the highest prevalence (n = 40) observed in 2009. There was no overall increase in number of minor SGTs/year.

There was a decreasing trend in prevalence of minor SGTs over the last 5 years (2011–2016, n = 28.83) in comparison to the previous 6 years of the study (2004–2009, n = 30.17). Even though the number of cases/year since 2009 has decreased, a higher number of minor SGTs are still currently being diagnosed. This is significantly higher than other South African and African studies (8.75; 6.08; 7.16) [9, 13, 15].

Chinese reports showed much higher means/year (52; 42) compared to our study [4, 19]. Other Asian (18–21), European and American (2.42–8.5) studies showed much lower means/year) except for a single Californian study (19) [1–3, 5, 6, 10, 11, 14, 17, 18]. Reports from Iran, USA and Venezuela showed a much lower prevalence (0.3%; 0.4%; 0.7%) [10, 11, 16]. Most studies generally revealed a lower prevalence of minor SGTs besides this study and those from China (Table 4) [4, 19].

Table 4.

| Reports | Current | South Africa | Africa | International | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chinese | Other Asian | European | American | ||||

| Prevalence (means/year) | 27.7 | 8.75 | 6.08; 7.16 | 52; 42 | 18–21 | 2.42–8.5; 19 | |

| Prevalence (%/year) | 2.3 | 0.3 | 0.4; 0.7 | ||||

| Prevalence (overall %) | 44.34 | 16.9 | 28.5 | 27.2 | |||

| Mean age | 44 | 37; 41 | 33; 41 | ||||

| Gender: M:F | 1:1.8 | 1:1.3; 1:1.6 | 1:1.3;1:1.3;1:1 | 1.1:1 | > F | > F; 2.5:1 | > F |

| Benign:malignant SGTs | 1.4:1 | 2.6:1; 1.1:1 | 3:4:1;1:1.1 | >Malignant | 2:1 | Variable | |

| Most common SGT (%) | Pleomorphic adenoma | ||||||

| 51.9 | 70;48 | 90.1; 73.6; 68.3 | 81.8–96.4 | ||||

| Most common malignant SGT (%) | ACC:12.8 |

ACC: 37.5 PLGA: 30 |

ACC: 38.3 MEC |

ACC MEC |

|||

| Most common site | Palate | ||||||

M:F male:female, ACC adenoid cystic carcinoma, MEC Mucoepidermoid carcinoma

Many studies did not include the prevalence of minor SGTs or total number of cases, and some combined both major and minor SGTs making comparisons difficult.

The literature shows great variability in the prevalence of minor and major SGTs. In addition to differences in reporting of tumors, the unusually high prevalence of SGTs at our institution may be due to referral systems. Most patients undergoing biopsies for head/neck/oral pathology are referred to specialized oral/maxillofacial diagnostic centres which may result in biased representation of the pathology that actually occurs in that region [4, 19]. Another possibility, especially regarding the increase in malignant SGTs is the ‘harvesting effect’, which is the management of benign tumors by oral/maxillofacial surgeons themselves, with referral of patients with malignant minor SGTs to specialized academic institutions [2].

Global reports are unanimous in their findings of SGTs being more common in major salivary glands [5, 6, 14–16, 22, 23]. Our study concurs in that 55.7% were major and 44.3% minor SGTs. Studies from China (16.9%), Croatia (27.2%) and Pakistan (28.5%) showed a much lower percentage of minor SGTs [5, 12, 19].

Minor SGTs occurred in patients between 9 and 93 years (mean 44 years). There was no statistically significant age difference between males (45 years) and females (44 years) when considering minor SGTs only (p = 0.64). A statistically significant age difference was noted for patients with benign (40 years) and malignant (50 years) minor SGTs (p = 0.00). The association between age and whether minor SGTs were benign or malignant was statistically significant for both females and males (p < 0.05). Benign tumors occurred at a younger age for both males and females. Malignant SGTs were very uncommon in patients < 20 years for both sexes.

Previous South African studies showed significantly lower mean ages for males (37 years) and females (41 years), and showed benign SGTs at a younger age [8, 9]. Nigerian reports concurred with our study in terms of mean ages for both sexes for malignant SGTs, and showed benign SGTs at an earlier age; the mean age for both males and females being much lower for benign (33 years) and malignant (41 years) SGTs [13, 15]. Contrary to most studies, an American report showed malignant SGTs presenting much earlier, by an average of six years [2]. Most international studies agree that mean age of presentation for benign minor SGTs is significantly lower [3, 6, 11, 12, 17, 18]. Regarding gender distribution of minor SGTs in our study, 63.7% were females (n = 352) and 36.3% (n = 201) males. Most studies show minor SGTs to have a higher predilection for females [1–4, 8–11, 17, 22]. The benign to malignant SGT ratio was 1.2:1 in females and 1.5:1 in males. Females appeared more likely to have malignant tumors. Middle-aged females (between 40 and 61 years) showed a greater percentage of malignant SGTs.

Previous South African studies showed similar gender distribution for minor SGTs (females: 56%; 62%; males: 44%; 38%) [8, 9]. International studies (African, Asian, American) showed a higher predilection of minor SGTs in females [2–4, 7, 10, 11, 14, 18]. Zimbabwean and Ugandan reports corroborate the higher minor SGT involvement in females (55.67%; 56.7% compared to males (44.32%; 43.3%) [22, 23]. There was an equal gender predilection in a Nigerian study and a higher male predilection in Chinese (50.6%) and English reports (71.43%) [17, 19].

The benign (56.96%) to malignant (43.04%) minor SGT ratio was 1.38:1. Conflicting reports on prevalence of benign and malignant SGTs from South Africa, Africa and the international literature, especially regarding which tumors occurred more commonly may be due to geographical variations in populations, smoking, medication, radiation, occupational exposure and immune suppression. HIV may play a significant role in our cohort as South Africa has the highest global incidence [24, 25].

Similar to our study, far fewer malignant than benign minor SGTs were noted in one South African study (28% versus 72%), with another showing the converse (52% versus 48%) [8, 9]. Similarly international studies showed a higher prevalence of benign than malignant minor SGTs in Zimbabwe (77.35% versus 22.65%), Japan (67.1% versus 32.9%), America and Europe [1, 3, 10, 11, 22]. On the contrary slightly more malignant than benign minor SGTs were seen in Uganda (53% versus 47%), Asia and other American and European reports [2, 4–6, 14, 16, 18, 24]. Differences may be due to variations in geography, nomenclature, classifications and reporting centers’ expertise. Classification of SGTs is dynamic, and with advances in immunohistochemistry and fluorescence in situ hybridization for molecular cytogenetic analysis, more specific and refined changes continue to unfold.

An American study showed an increased prevalence in white patients, most being malignant, whereas a South African study showed more black patients, with most being benign [2, 8]. Whilst this may suggest race as a factor in minor SGT etiology, it may purely be a population bias reflecting patient demographics in the areas of study. It would be inappropriate to draw inferences regarding the role of race in SGT prevalence as the cohort, especially in the latter study, which may be entirely from the public sector, which, by nature of the South African demographics, comprises largely of black patients [8]. Our study refrained from investigating the role of race in patient demographics of SGTs.

The three most common minor SGT for both genders in our study were pleomorphic adenoma (51.9%), adenoid cystic carcinoma and mucoepidermoid carcinoma. After pleomorphic adenoma, the two most common benign tumors were myoepithelioma (2.2%) and canalicular adenoma (2%). In other South African studies, pleomorphic adenoma (70%; 48%) was most common, followed by monomorphic adenomas (currently canalicular adenoma/basal cell adenoma) (2.5%) [8, 9]. Similarly, in African studies pleomorphic adenoma (90.1%; 73.6%; 68.3%) was most common followed by basal cell adenoma (5.5%) and myoepithelioma (3.6%) [13, 22, 23]. Asian, American and European studies also found pleomorphic adenoma to be the most common benign minor SGT (81.8% to 96.4%) [1–5, 11, 14, 17–19].

The four most common malignant minor SGTs in this study were adenoid cystic carcinoma (12.8%), mucoepidermoid carcinoma (10.5%), PLGA (9.4%), and acinic cell carcinoma (2.9%). In prior South African studies, these were adenoid cystic carcinoma (37.5%), adenocarcinoma (26.7%), mucoepidermoid (23.2%), and carcinoma ex pleomorphic adenoma (8.9%); and PLGA (30%), adenoid cystic carcinoma (25%), mucoepidermoid carcinoma (16.7%), and carcinoma ex pleomorphic adenoma (14%) [8, 9].

Whilst certain African studies like our study showed adenoid cystic carcinoma (38.3%) to be the most common malignant minor SGT, followed by mucoepidermoid carcinoma (19.2%) and PLGA, others showed this to be mucoepidermoid carcinoma, adenoid cystic carcinoma and adenocarcinoma [13, 23]. International studies also report conflicting results for the most common malignant minor SGTs. Studies similar to our study showed adenoid cystic carcinoma to be most common followed by mucoepidermoid carcinoma [3, 4, 6, 7, 14, 16]. Others showed this to be mucoepidermoid carcinoma followed by adenoid cystic carcinoma or PLGA [5, 10, 11, 17, 18].

The most common site for minor SGTs in this study was the palate as a whole, including hard palate, soft palate and palate (NOS). The palate being the most common site correlated with most studies worldwide [1–5, 8–11, 13, 14, 16–19, 22, 23]. Most studies did not delineate specific palatal sites.

A limitation of the study is that it is a retrospective review of histology reports, and clinical information may have been lacking resulting in incomplete patient data. Since each case was not reviewed histologically, there remains a margin of error, albeit small.

The referral basis of tumors assessed was mainly from governmental academic institutions in South Africa, which represents one of the largest public/state referral centers in the country. Johannesburg is the most populous city in South Africa, with a population of 4.4 million [26]. The Departments of Otorhinolaryngology and Oral Pathology service the largest teaching and referral hospital in South Africa, based in the Greater Johannesburg Metropolitan area, with an unofficial population of 8 million [26]. Oral/maxillofacial biopsy specimens diagnosed in the Oral Pathology Unit are often received from patients from outlying, peripheral and rural areas, other provinces and neighboring countries such as Namibia, Mozambique, Swaziland and Zimbabwe, and this may reflect in increased prevalence of SGTs.

Whilst the sample size of minor SGTs was large, other tumors may have been analyzed in the Department of Anatomical Pathology, not Oral Pathology, and were not included. This study may not reflect the true prevalence of SGTs in this population at large. It is significant to note that this study is a description of the prevalence of minor SGTs diagnosed in a defined specialist Maxillofacial/Oral Pathology Unit. It by no means represents an accurate reflection of the prevalence of SGTs in Johannesburg. It is however, a relatively accurate and thorough insight of SGTs diagnosed in this specialized Oral Pathology Unit. The overall findings are relevant, and comparable to other South African medical centers. More than sufficient volume of minor SGTs has been analyzed for a meaningful outcome. A major strength no doubt is that the study offers an overview of SGTs, especially of minor salivary glands, seen in a defined South African population, and provides a baseline for future studies on SGTs, especially in South Africa.

Of the South African studies, ours showed the highest minor SGT prevalence. All showed an increased prevalence in females, the most common age being the fifth and sixth decades and most common site the palate. One report like ours, showed more benign than malignant minor SGTs, however another showed the converse [8, 9]. Pleomorphic adenoma was the most common tumor. Like our study, one report shows adenoid cystic carcinoma to be the most common minor SGT, whilst PLGA was the most common in another [8, 9].

The prevalence of benign (57%) and malignant (43%) minor SGTs was 2.2%, which is much higher than most previous reports. There was an overall increase of minor SGTs diagnosed per year. The most common minor SGTs are pleomorphic adenoma, adenoid cystic carcinoma and mucoepidermoid carcinoma. Both benign and malignant minor SGTs are more common in females. Benign tumors present on an average ten years earlier than malignant tumors. There is no gender difference in terms of age. The most common minor SGT site is the palate. Pleomorphic adenoma is the most common minor SGT for both genders at all sites. The most common minor SGTs of the hard palate are pleomorphic adenoma and adenoid cystic carcinoma for both genders. In the soft palate, mucoepidermoid carcinoma is more common in females. Mucoepidermoid carcinoma is the most common malignant tumor in the palate (NOS) across both genders. For all other sites, malignant minor SGTs were more common in females than males. The minor SGT demographic data presented may aid in an improved understanding of their clinico-pathologic characteristics, especially when compared to similar published reports.

Funding

No funding obtained.

Compliance with Ethical Standards

Conflict of interest

The authorrs declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

This study is a useful insight to the frequency and clinico-pathologic demographics of minor SGTs in a defined South African population, and compares the demographic data of patients with minor salivary glands in various American, European, Asian and African countries.

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Yaseer Mahomed, Email: dr.yaseero@gmail.com.

Shabnum Meer, Email: shabnum.meer@wits.ac.za, Email: shabnum.meer@nhls.ac.za.

References

- 1.Loyola AM, de Araújo VC, de Sousa SO, de Araújo NS. Minor salivary gland tumours. A retrospective study of 164 cases in a Brazilian population. Eur J Cancer B. 1995;31:197–201. doi: 10.1016/0964-1955(95)00001-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jansisyanont P, Blanchaert RH, Jr, Ord RA. Intraoral minor salivary gland neoplasm: a single institution experience of 80 cases. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2002;31:257–261. doi: 10.1054/ijom.2002.0223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Toida M, Shimokawa K, Makita H, et al. Intraoral minor salivary gland tumours: a clinicopathological study of 82 cases. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2005;34:528–532. doi: 10.1016/j.ijom.2004.10.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wang D, Li Y, He H, et al. Intraoral minor salivary gland tumours in a Chinese population: a retrospective study on 737 cases. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2007;104:94–100. doi: 10.1016/j.tripleo.2006.07.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lukšić I, Virag M, Manojlović S, Macan D. Salivary gland tumours: 25 years of experience from a single institution in Croatia. J Craniomaxillofacial Surg. 2012;40:e75–e81. doi: 10.1016/j.jcms.2011.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jaafari-Ashkavandi Z, Ashraf MJ, Moshaverinia M. Salivary gland tumours: a clinicopathologic study of 366 cases in southern Iran. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2013;14:27–30. doi: 10.7314/APJCP.2013.14.1.27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Strick MJ, Kelly C, Soames JV, McLean NR. Malignant tumours of the minor salivary glands—a 20 year review. Br J Plast Surg. 2004;57:624–631. doi: 10.1016/j.bjps.2004.04.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Isacsson G, Shear M. Intraoral salivary gland tumours: a retrospective study of 201 cases. J Oral Pathol. 1983;12:57–62. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0714.1983.tb00316.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Van Heerden WF, Raubenheimer EJ. Intraoral salivary gland neoplasms: a retrospective study of seventy cases in an African population. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1991;71:579–582. doi: 10.1016/0030-4220(91)90366-K. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rivera-Bastidas H, Ocanto RA, Acevedo AM. Intraoral minor salivary gland tumours: a retrospective study of 62 cases in a Venezuelan population. J Oral Pathol Med. 1996;25:1–4. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0714.1996.tb01214.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Buchner A, Merrell PW, Carpenter WM. Relative frequency of intra-oral minor salivary gland tumours: a study of 380 cases from Northern California and comparison to reports from other parts of the world. J Oral Pathol Med. 2007;36:207–214. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0714.2007.00522.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rahman B, Mamoon N, Jamal S, et al. Malignant tumours of the minor salivary glands in northern Pakistan: a clinicopathological study. Hematol Oncol Stem Cell Ther. 2008;1:90–93. doi: 10.1016/S1658-3876(08)50039-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gbotolorun OM, Arotiba GT, Effiom OA, Omitola OG. Minor salivary gland tumours in a Nigerian Hospital: a retrospective review of 146 cases. Odontostomatol Trop. 2008;31:17–23. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tilakaratne WM, Jayasooriya PR, Tennakoon TM, Saku T. Epithelial salivary tumours in Sri Lanka: a retrospective study of 713 cases. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol. 2009;108:90–99. doi: 10.1016/j.tripleo.2009.01.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lawal AO, Adisa AO, Kolude B, Adeyemi BF. Malignant salivary gland tumours of the head and neck region: a single institutions review. Pan Afr Med J. 2015;20:121. doi: 10.11604/pamj.2015.20.121.3458. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Taghavi N, Sargolzaei S, Mashhadiabbas F, Akbarzadeh A, Kardouni P. Salivary gland tumours: a 15-year report from Iran. Turk Patoloji Derg. 2016;32:35–39. doi: 10.5146/tjpath.2015.01336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Abrahão AC, Santos Netto Jde N, Pires FR, Santos TC, Cabral MG. Clinicopathological characteristics of tumours of the intraoral minor salivary glands in 170 Brazilian patients. Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2016;54:30–34. doi: 10.1016/j.bjoms.2015.10.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sarmento DJ, Morais M, Costa AL, Silveira EJ. Minor intraoral salivary gland tumours: a clinical-pathological study. Einstein (Sao Paulo). 2016;14:508–512. doi: 10.1590/s1679-45082016ao3749. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Shen SY, Wang WH, Liang R, Pan GQ, Qian YM. Clinicopathologic analysis of 2736 salivary gland cases over a 11-year period in Southwest China. Acta Otolaryngol. 2018;138:746–749. doi: 10.1080/00016489.2018.1455108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Barnes L, Eveson JW, Reichart P, Sidransky D. WHO classification of tumours. Pathology and genetics of head and neck tumours. Lyon: IARC Press; 2005. p. 210. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Seethala RR, Stenman G. Update from the 4th edition of the World Health Organization classification of head and neck tumours: tumours of the salivary gland. Head Neck Pathol. 2017;11:55–67. doi: 10.1007/s12105-017-0795-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chidzonga MM, Lopez Perez VM, Portilla-Alvarez AL. Salivary gland tumours in Zimbabwe: report of 282 cases. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1995;24:293–297. doi: 10.1016/S0901-5027(95)80032-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Vuhahula EA. Salivary gland tumours in Uganda: clinical pathology study. Afr Health Sci. 2004;4:15–23. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.To VS, Chan JY, Tsang RK, Wei WI. Review of salivary gland neoplasms. ISRN Otolaryngol. 2012;2012(16):872982. doi: 10.5402/2012/872982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Alli N, Meer S. Head and neck lymphomas: a 20-year review in an Oral Pathology Unit, Johannesburg, South Africa, a country with the highest global incidence of HIV/AIDS. Oral Oncol. 2017;67:17–23. doi: 10.1016/j.oraloncology.2017.01.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Johannesburg—World population review. http://worldpopulationreview.com/world-cities/johannesburg-population/. Accessed 1 Oct 2019.