Abstract

Aim

Evaluate pretreatment hemoglobin values as a prognostic factor in patients with locally advanced head and neck squamous cell carcinoma treated with concurrent chemoradiotherapy.

Background

Anemia is one of the most prevalent laboratory abnormalities in oncological disease. It leads to a decrease in cellular oxygen supply, altering radiosensitivity of tumor cells and compromising therapeutic outcomes.

Materials and Methods

Retrospective evaluation of patients with HNSCC treated with cCRT. Primary and secondary endpoint was to evaluate the correlation of Hb levels (≥12.5 g/dL or <12.5 g/dL) at the beginning of cCRT with overall survival (OS) and progression-free survival (PFS), respectively.

Results

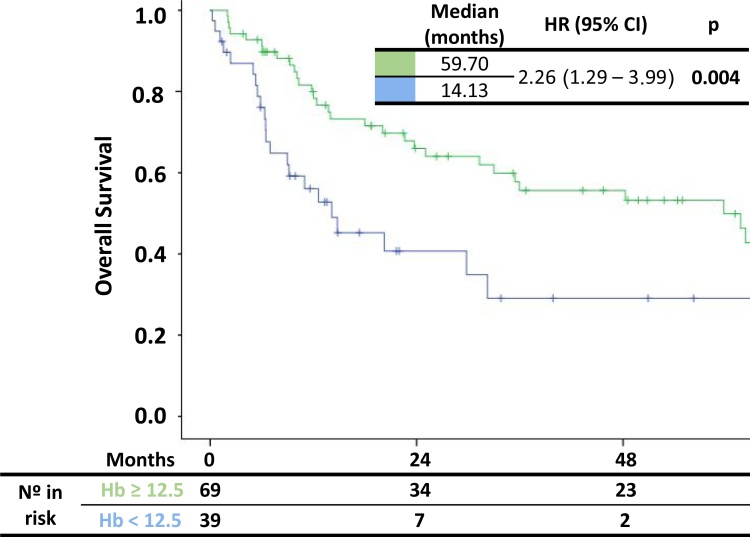

A total of 108 patients were identified. With a median follow-up of 16.10 months median OS was 59.70 months for Hb ≥12.5 g/dL vs. 14.13 months for Hb <12.5 g/dL (p = 0.004). PFS was 12.29 months for Hb ≥12.5 g/dL and 1.68 months for Hb <12.5 g/dL (p = 0.016).

Conclusions

In this analysis, Hb ≥12.5 g/dL correlated with significantly better OS and PFS. Further studies are needed to validate these findings.

Keywords: Hemoglobin, Anemia, Biomarkers, Head and neck neoplasms, Chemoradiotherapy

1. Background

In 2018, head and neck tumors were estimated to account for 3.7% of all new cancers and 13,740 of all number of cancer deaths in the United States.1 Worldwide, head and neck tumors account for more than 550,000 new cancer cases and 380,000 deaths from cancer annually, with a predominance of squamous cell carcinoma histology.2

Locoregionally advanced head and neck squamous cell carcinoma (HNSCC) is associated with an increased risk of both local recurrence and distant metastases.3 Combined modality approaches (surgery, radiation with or without chemotherapy) are required to optimize the chances of long-term disease control and data from randomized trials support integrated chemotherapy and radiation as a standard treatment option for patients with advanced tumors for whom an organ-preservation strategy is desirable.4 Despite these combined modality approaches, cure rates are poorer for this subgroup compared with early-stage counterparts, ranging from 10 to 65% depending on the primary site and disease extent and, although treatment outcomes have improved with the addition of chemo to radiation therapy, locoregional recurrence remains a significant concern, with 50–60% of patients experiencing local disease recurrence within 2 years of diagnosis.3, 4, 5

Additionally, it should be emphasized that these treatment options have substantial acute and late toxicities, with a significant impact on patients’ quality of life and survival. Thus, efforts should be employed to identify biomarkers of treatment outcomes in order to adjust treatment for specific patient subgroups and improve cancer control. Ideally, these biological markers should be easily available, simple to use, and cost-effective, with blood cell count being one such example.6, 7

Numerous studies have suggested that the presence of anemia is associated with worse local control and survival in various types of cancer, such as head and neck.7, 8, 9 Although a direct association between tumor hypoxia and anemia is unclear, anemia is known to lead to decreased cell oxygenation and has been shown to contribute to radiation and chemotherapy resistance via oxygen deprivation, a key element for the cytotoxic action of these therapies.8, 10, 11 Final results from the French Head and Neck Oncology and Radiotherapy Group trial 94-01 showed that stage and hemoglobin (Hb) levels before treatment were significant prognostic factors for survival and locoregional control.12 A low pretreatment Hb level (inferior to 12.5 g/dL) was found to be the most negative prognostic factor for overall survival (OS), specific disease-free survival, and locoregional control during the study's two-year follow-up, with a 92% probability of death in 37 (17%) patients with Hb levels lower than 12.5 g/L (odds ratio 10.36; 95% CI 3.07–34.97; p < 0.0001).12

2. Aim

The aim of the present retrospective analysis was to evaluate pretreatment Hb values as a prognostic factor in patients with locally advanced HNSCC treated with concurrent chemoradiotherapy (cCRT). The proposed hypothesis is that higher pretreatment Hb levels correlate with better survival.

3. Materials and methods

3.1. Study population

Patients with newly diagnosed locally advanced HNSCC treated with cCRT at Hospital de Santa Maria – Centro Hospitalar Universitário Lisboa Norte between January 2008 and December 2018 were consecutively enrolled and retrospectively evaluated. Patients underwent head and neck computerized tomography scan for external beam radiotherapy (EBRT) planning, with 3-mm image thickness reconstruction. Target volumes and dose report were in accordance with specific International Commission on Radiation Units (ICRU) for each EBRT technique applied.13, 14, 15 Patients treated from 2008 to 2014 were submitted to conformal EBRT (3D-CRT) and received 70 Gy in 35 fractions. Prescription dose was changed to 69.96 Gy in 33 fractions after 2014 due to the introduction of intensity-modulated radiotherapy (IMRT) with an integrated boost technique. During EBRT, patients were scheduled to receive three doses of intravenous cisplatin 100 mg/m2 on radiotherapy days 1, 22, and 43.

Twelve weeks after cCRT completion, patients were assessed for treatment response by clinical examination and computed tomography. Additional follow-up consisted of clinical examination every 3 months in the first year and every 3–6 months in the second year. After 2 years, follow-up intervals were extended to once a year, with radiographic assessment with computed tomography performed every year or whenever clinical progression was suspected. Progression and treatment response were defined according to the Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumors (RECIST).

The study primary endpoint was correlation of pretreatment Hb levels – stratified by ≥12.5 g/dL or <12.5 g/dL – with OS. As secondary endpoint, correlation of pretreatment Hb levels with PFS was investigated. The Hb cut off was established according to the literature.

Other clinical and laboratory baseline characteristics were retrieved from patients’ clinical records whenever available: age, performance status according to the Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG PS), smoking and alcohol history, primary tumor location, tumor grade, and staging according to the 7th edition of the American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC). Additionally, date of disease progression and time of death or last follow-up visit were also collected.

3.2. Statistical analysis

Sample size was not pre-planned, as this was a convenience sample, only determined by pre-defined inclusion criteria.

Patients were categorized according to parameters included in the analysis: gender (female vs. male), ECOG PS (0 or 1 vs. ≥2), primary tumor location (oral cavity vs. laryngopharyngeal, pharynx vs. laryngopharyngeal, and larynx vs. laryngopharyngeal), tumor stage (IV vs. others), smoking history (yes vs. no), and alcoholic habits (yes vs. no). Median and interquartile range (IQR) were reported for continuous variables and frequencies for categorical variables. To compare categorical variables among groups, χ2 and Fisher exact tests were used whenever appropriate. The Mann–Whitney test was used to compare medians.

Outcome measures consisted of OS and progression-free survival (PFS). OS was defined as time between treatment start and death, irrespective of cause. PFS was defined as time between treatment start and time of progression (as established by RECIST criteria) or death, whichever came first. Median OS and PFS were obtained using the Kaplan–Meier method and log-rank test was used to compare group outcomes. To assess the effect of analyzed parameters in response duration and prognosis, univariate and multivariate analyses were conducted using the Cox regression model. All statistical tests were two-tailed and statistical significance was assumed when the p-value was inferior to 0.05. IBM's SPSS statistics v.24 was used for statistical analysis.

4. Results

A total of 108 patients were treated with cCRT during the nearly 10-year period. All patients had sufficient follow-up data (12 weeks) and were thus eligible for study inclusion.

4.1. Baseline characteristics

Study cohort had a median of 58.5 years (IQR 50.0–64.0; min–max 18.0–77.0), with 93.5% of males and 89.8% of ≤1 ECOG PS patients. Most patients had been previously exposed to risk factors including alcohol and tobacco smoke (60.2% and 91.7%, respectively) and the most prevalent primary tumor site was the oral cavity (36.1%), followed by the pharynx (29.6%). Eighty patients (74.0%) had stage IV disease and only 2.8% of patients had early-stage disease and were eligible for cCRT instead of a unimodality therapeutic approach.

Pretreatment Hb levels ≥12.5 g/dL were observed in 63.9% of patients. None of the patients included in this study had history of blood transfusion prior to the start of cCRT. Groups stratified according to pretreatment Hb levels had well-balanced baseline characteristics, apart from primary tumor location and staging. It should be highlighted that ECOG PS was worse in 15% of patients with pretreatment Hb <12.5 g/dL in contrast with 7% of patients with pretreatment Hb ≥12.5 g/dL and almost 40% of patients with pretreatment Hb <12.5 g/dL are stage IVb versus only 15% in the group with pretreatment Hb ≥12.5 g/dL. Characteristics of both groups are detailed in Table 1.

Table 1.

Patients baseline characteristics in the global population and stratified by pretreatment hemoglobin levels.

| Global | Hb < 12.5 g/dL | Hb ≥ 12.5 g/dL | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patients, n | 108 | 39 | 69 | |

| Age | ||||

| Median, years | 58.5 | 61.0 | 58.0 | 0.416 |

| IQR, years | 50.0–64.0 | 53.0–64.0 | 49.5–64.0 | |

| Gender | ||||

| Male, n (%) | 101 (93.5) | 35 (89.7) | 66 (95.7) | 0.250 |

| Female, n (%) | 7 (6.5) | 4 (10.3) | 3 (4.3) | |

| Performance status – ECOG | ||||

| 0–1, n (%) | 97 (89.8) | 33 (84.6) | 64 (92.8) | 0.199 |

| ≥2, n (%) | 11 (10.2) | 6 (15.4) | 5 (7.2) | |

| Alcoholic habits | ||||

| Yes, n (%) | 65 (60.2) | 12 (30.8) | 30 (43.5) | 0.219 |

| No, n (%) | 42 (38.9) | 27 (69.2) | 38 (55.1) | |

| Missing data, n (%) | 1 (0.9) | – | 1 (1.4) | |

| Smoking habits | ||||

| Yes, n (%) | 99 (91.7) | 35 (89.7) | 64 (92.8) | 0.720 |

| No, n (%) | 9 (8.3) | 4 (10.3) | 5 (7.2) | |

| Primary tumor site | 0.006 | |||

| Oral cavity, n (%) | 39 (36.1) | 14 (35.9) | 25 (35.9) | 0.638 |

| Larynx, n (%) | 20 (18.5) | 3 (7.7) | 17 (24.6) | |

| Oral cavity, n (%) | 39 (36.1) | 14 (35.9) | 25 (35.9) | 1.000 |

| Pharynx, n (%) | 32 (29.6) | 11 (28.2) | 21 (30.4) | |

| Oral cavity, n (%) | 39 (36.1) | 14 (35.9) | 25 (35.9) | 0.216 |

| Pharyngolanryngeal, n (%) | 17 (15.7) | 11 (28.2) | 6 (8.7) | |

| Larynx, n (%) | 20 (18.5) | 3 (7.7) | 17 (24.6) | 0.888 |

| Pharynx, n (%) | 32 (29.6) | 11 (28.2) | 21 (30.4) | |

| Larynx, n (%) | 20 (18.5) | 3 (7.7) | 17 (24.6) | 0.010 |

| Pharyngolanryngeal, n (%) | 17 (15.7) | 11 (28.2) | 6 (8.7) | |

| Pharynx, n (%) | 32 (29.6) | 11 (28.2) | 21 (30.4) | 0.195 |

| Pharyngolanryngeal, n (%) | 17 (15.7) | 11 (28.2) | 6 (8.7) | |

| Stage grouping | 0.002 | |||

| II, n (%) | 3 (2.8) | 1 (2.6) | 2 (2.9) | 1.000 |

| III, n (%) | 24 (22.2) | 3 (7.7) | 21 (30.4) | |

| II, n (%) | 3 (2.8) | 1 (2.6) | 2 (2.9) | 1.000 |

| IVA, n (%) | 55 (50.9) | 20 (51.3) | 35 (50.7) | |

| II, n (%) | 3 (2.8) | 1 (2.6) | 2 (2.9) | 1.000 |

| IVB, n (%) | 25 (23.1) | 15 (38.5) | 10 (14.5) | |

| III, n (%) | 24 (22.2) | 3 (7.7) | 21 (30.4) | 0.224 |

| IVA, n (%) | 55 (50.9) | 20 (51.3) | 35 (50.7) | |

| III, n (%) | 24 (22.2) | 3 (7.7) | 21 (30.4) | 0.003 |

| IVB, n (%) | 25 (23.1) | 15 (38.5) | 10 (14.5) | |

| IVA, n (%) | 55 (50.9) | 20 (51.3) | 35 (50.7) | 0.219 |

| IVB, n (%) | 25 (23.1) | 15 (38.5) | 10 (14.5) | |

| Follow-up | ||||

| Median, months | 16.1 | 9.9 | 23.9 | |

| IQR, months | 6.7–45.0 | 5.5–20.2 | 10.0–71.8 |

IQR: interquartile range; ECOG: Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group; Hb: hemoglobin.

The overall median follow-up was 16.1 months (IQR 6.7–45.0). A total of 54 patients (50.0%) had died by the time of last follow-up, with a median time to death of 33.0 months (95% CI 10.0–56.0), 33 of which in the ≥12.5 g/dL pretreatment Hb level group and 21 in the <12.5 g/dL pretreatment Hb level group. Fifty-four patients remained on regular follow-up after cCRT completion, with regular radiographic assessment for disease progression.

4.2. Survival in cCRT-treated patients, stratified by pretreatment Hb levels

Median OS by Kaplan–Meier analysis (Fig. 1) was significantly longer for patients with pretreatment Hb ≥12.5 g/dL compared with those with pretreatment Hb <12.5 g/dL (59.70 months, 95% CI 3.91–24.34 vs. 14.13 months, 95% CI 31.02–88.37). Patients with pretreatment Hb levels <12.5 g/dL were 2.26 times more likely to die compared with patients with pretreatment Hb levels ≥12.5 g/dL (p = 0.004). OS analysis is shown in Table 2.

Fig. 1.

Kaplan–Meier curves of overall survival according to pretreatment hemoglobin levels.

HR: hazard ratio; CI: confidence interval; Hb: hemoglobin

Table 2.

Prognostic role of baseline characteristics and pretreatment hemoglobin levels: univariate and multivariate analysis for overall survival.

| OS | Univariate |

Multivariate |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HR | 95% CI | p-Value | HR | 95% CI | p-Value | |

| Hemoglobin | ||||||

| <12.5 g/dL vs. ≥12.5 g/dL | 2.26 | 1.29–3.99 | 0.005 | 1.97 | 1.10–3.53 | 0.004 |

| Gender | ||||||

| Female vs. male | 0.95 | 0.30–3.04 | 0.927 | – | – | – |

| Smoking habits | ||||||

| Yes vs. no | 1.35 | 0.49–3.75 | 0.567 | 0.540a | ||

| Alcoholic habits | ||||||

| Yes vs. no | 0.88 | 0.52–1.52 | 0.654 | – | – | – |

| ECOG | ||||||

| 0–1 vs. ≥2 | 0.77 | 0.33–1.80 | 0.542 | 0.926a | ||

| Primary tumor site | 0.150 | 0.066a | ||||

| Larynx vs. pharyngolaryngeal | 0.98 | 0.35–2.77 | 0.972 | |||

| Pharynx vs. pharyngolaryngeal | 1.04 | 0.40–2.67 | 0.937 | |||

| Oral cavity vs. pharyngolaryngeal | 1.94 | 0.79–4.77 | 0.150 | |||

| Stage grouping | ||||||

| IV vs. others | 2.02 | 1.03–3.97 | 0.040 | 0.128a | ||

OS: overall survival; IQR: interquartile range; HR: hazard ratio; ECOG: Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group; Hb: hemoglobin.

Included in multivariate analysis due to its prognostic factor.

In univariate analysis, only stratified pretreatment Hb levels and staging group were associated with better OS (Table 2). After adjusting for confounding and clinically significant factors, multivariate analysis revealed that pretreatment Hb levels ≥12.5 g/dL remained predictive of better survival (HR 1.97, 95% CI 1.10–3.53, p = 0.004) (Table 2).

4.3. Duration of response in cCRT-treated patients, stratified by pretreatment Hb levels

Median PFS was significantly longer in the ≥12.5 g/dL pretreatment Hb group (12.29 months, 95% CI 0.00–30.36) than in the <12.5 g/dL pretreatment Hb group (1.68 months, 95% CI 1.54–1.81; Table 3). Patients with lower pretreatment Hb levels were 2.22 times more likely to experience disease progression compared with those with higher pretreatment Hb levels (p = 0.016). PFS Kaplan–Meier curves are shown in Fig. 2. In multivariate analysis, after adjusting for confounding and clinically significant parameters, <12.5 g/dL pretreatment Hb levels remained predictive of worse PFS (HR 1.89, 95% CI 1.12–3.17, p = 0.016) (Table 3).

Table 3.

Prognostic role of baseline characteristics and pretreatment hemoglobin levels: univariate and multivariate analysis for progression-free survival.

| PFS | Univariate |

Multivariate |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HR | 95% CI | p-Value | HR | 95% CI | p-Value | |

| Hemoglobin | ||||||

| <12.5 g/dL vs. ≥12.5 g/dL | 2.22 | 1.38–3.59 | 0.001 | 1.89 | 1.12–3.17 | 0.016 |

| Gender | ||||||

| Female vs. male | 0.69 | 0.25–1.89 | 0.469 | – | – | – |

| Smoking habits | ||||||

| Yes vs. no | 0.57 | 0.23–1.41 | 0.221 | 0.224a | ||

| Alcoholic habits | ||||||

| Yes vs. no | 0.94 | 0.59–1.50 | 0.802 | – | – | – |

| ECOG | ||||||

| 0–1 vs. ≥2 | 0.71 | 0.34–1.48 | 0.357 | 0.515a | ||

| Primary tumor site | 0.001 | 0.013 | ||||

| Larynx vs. pharyngolaryngeal | 0.41 | 0.17–1.00 | 0.050 | 0.65 | 0.25–1.69 | 0.374 |

| Pharynx vs. pharyngolaryngeal | 0.61 | 0.30–1.26 | 0.182 | 0.91 | 0.42–1.99 | 0.812 |

| Oral cavity vs. pharyngolaryngeal | 1.58 | 0.81–3.06 | 0.180 | 1.93 | 0.99–3.87 | 0.062 |

| Stage grouping | ||||||

| IV vs. others | 0.40 | 0.21–0.72 | 0.003 | 0.172 | ||

PFS: progression free survival; IQR: interquartile range; HR: hazard ratio; ECOG: Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group; Hb: hemoglobin.

Included in multivariate analysis due to its prognostic factor.

Fig. 2.

Kaplan–Meier curves of progression-free survival according to pretreatment hemoglobin levels.

HR: hazard ratio; CI: confidence interval; Hb: hemoglobin

5. Conclusion

Low Hb is an easily accessible and cheap marker of systemic inflammation capable of guiding clinical decisions regarding survival and recurrence among locally advanced HNSCC patients undergoing cCRT. Evidence suggests that in some solid tumors as head and neck, low Hb levels correlate with detrimental tumor oxygenation and hence diminished control rate and survival outcomes, even after adjusting for others prognostic parameters.16, 17, 18, 19, 20, 21 Research regarding adaptation of tumor cells to oxygen variations is key and was granted the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine in 2019.

The mechanism underlying poor prognosis is not properly established and may depend on the therapeutic approach. For instance, in radiotherapy-treated patients, it is hypothesized that anemia may predispose to tumor hypoxia and, hence, to radiation resistance. Pretreatment hemoglobin levels reflect blood's oxygen-binding capacity, which is crucial both for tumor oxygen supply and for tumor cell response to cytotoxic therapy, particularly radiotherapy.6, 19, 20, 21, 22 Radiation ionizes water molecules and forms reactive oxygen species which react with deoxyribonucleic acid (DNA) and form DNA radicals. If available, in satisfactory amounts, oxygen reacts with DNA radicals and repairs radiation-induced DNA damage. Therefore, the tumor cell-killing ability of ionizing radiation is enhanced by oxygen up to 2.5–3 times, named the oxygen enhancement ratio.16, 20, 21, 22

When analyzing the impact of low Hb levels, the Hb cut-off value that may be useful for prognostic stratification should also be addressed.16 Conflicting results may be observed with different cut-offs or anemia definitions, potentially affecting reported outcomes. The impact of blood transfusions and erythropoietin on increasing Hb levels should also be considered. Erythropoietin is indicated for supportive care during treatment, but its impact on disease control and survival is not known. DAHANCA 10 interim results were alarming because patients had worse event-free survival (HR 1.36 [1.09–1.69]), disease-specific death (HR 1.43 [1.08–1.90]), and OS (HR 1.30 [1.02–1.64]) when darbepoetin alfa was administered to increase Hb values (>14.0 g/dL) without increased cardiovascular events.22 Phase III studies addressing this question and the impact of blood transfusions are therefore required.19 Recent studies are preferentially focused on the hypoxic status of HNSCC tumors rather than on Hb levels, with the purpose of investigating the value of functional imaging hypoxic markers, gene signatures, and new treatment strategies as specific hypoxic radiosensitizers (e.g. nimorazole).20, 21, 22, 23, 24, 25

In line with previous studies, the present data shows that pre-cCRT Hb values lower than 12.5 g/dL adversely affect OS (p = 0.005) and PFS (p = 0.001) outcomes in HNSCC patients. In multivariate analysis, pretreatment Hb levels remained a significant independent predictor of both OS (p = 0.004) and PFS (p = 0.016). Smoking habits were considered in this study for their prognostic role and for their impact on formation of carboxyhemoglobin, with subsequent hypoxia increase and radiation response decrease.26

Also, importantly, in this study patients with a pretreatment Hb value inferior to 12.5 g/dL were 2.26 more likely to die. Given this result, this parameter should be quantified and considered as a stratification factor in future randomized clinical trials. Additionally, efforts should be made to use these same alterations for improving the quality of life measurements, although at present time data regarding the impact of Hb correction in these patients’ outcomes is still lacking.20, 26, 27

Although this study suggests a potential role for pretreatment Hb levels as both a prognostic and predictive marker in locally advanced HNSCC treated with cCRT, it has some limitations. The primary is its small sample size and retrospective nature, with different sub-locations of disease that do not have the same biological behavior and prognostic. Moreover, each subgroup has a limited number of patients, so when analyzing the results, the impact of this biases associated with others, like the potentially missing data regarding clinical variables like toxicities or treatment interruptions, could increase, and the statistical power of this analysis can decrease. Second, this investigation was constrained to pretreatment Hb levels, not considering the potential impact of anemia diagnosed during treatment or of further lowered Hb levels throughout cCRT. Such variations may alter the true rate of anemic patients in this sample, with a potential impact in retrieved results. Third, it is also important to address the lack of information about Human papillomavirus (HPV) status. In our institution this data is only available since 2018, with only two p16-posite oropharyngeal squamous-cell carcinoma in concordance with the fact that the major risk factor for HNSCC in Portugal is smoking habits. Despite this, we recognize the potential bias of HPV infection, as recent studies have shown that hemoglobin concentration is also an independent prognostic factor for patients with p16-positive oropharyngeal squamous-cell carcinoma.28

In the present study, pretreatment Hb levels were an independent prognostic and predictive factor for survival outcomes, with higher pretreatment levels associated with duration and survival benefit in patients with locally advanced HNSCC treated with cCRT. These results are not novel, showing consistency with previously reported studies. Despite this, efforts to determine the mechanism by which anemia exerts its biologically detrimental effects and to ascertain the impact of its early correction in patient outcomes should be pursued and extended to other potential prognostic factors in order to better characterize individual prognosis and allow for a more tailored therapeutic approach, avoiding unnecessary risks and toxicities.

Conflicts of interest

None declared.

Financial disclosure

None declared.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank to all patients included in the analysis and to Joana Cavaco Silva for manuscript revision and writing.

References

- 1.Siegel R.L., Miller K.D., Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2018. CA Cancer J Clin. 2018;68(1):7–30. doi: 10.3322/caac.21442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fitzmaurice C., Allen C., Barber R.M. Global, Regional, and National Cancer Incidence, Mortality, Years of life lost, Years lived with Disability and Disability-adjusted life years for 32 cancer groups, 1990 to 2015: a systematic analysis for the global burden of disease study. JAMA Oncol. 2017;3(4):524–548. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2016.5688. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.McCloskey S.A., Jaggernauth W., Rigual N.R. Radiation treatment interruptions greater than one week and low hemoglobin levels (12 g/dL) are predictors of local regional failure after definitive concurrent chemotherapy and intensity-modulated radiation therapy for squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck. Am J Clin Oncol. 2009;32(6):587–591. doi: 10.1097/COC.0b013e3181967dd0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Forastiere A.A., Goepfert H., Maor M. Concurrent chemotherapy and radiotherapy for organ preservation in advanced laryngeal cancer. N Engl J Med. 2003;349(22):2091–2098. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa031317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Forastiere A.A., Zhang Q., Weber R.S. Long-term results of RTOG 91-11: a comparison of three nonsurgical treatment strategies to preserve the larynx in patients with locally advanced larynx cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2013;31(7):845–852. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2012.43.6097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tham T., Olson C., Wotman M. Evaluation of the prognostic utility of the hemoglobin-o-red cell distribution width ratio in head and neck cancer. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2018;275(11):2869–2878. doi: 10.1007/s00405-018-5144-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rades D., Stoehr M., Kazic N. Locally advanced sage IV squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck: impact of the pre-radiotherapy hemoglobin level and interruptions during radiotherapy. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2008;70(4):1108–1114. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2007.07.2380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pehlivam B., Zouhair A., Luthi F. Decrease in hemoglobin levels following surgery influences the outcome in head and neck cancer patients treated with accelerated postoperative radiotherapy. Ann Surg Oncol. 2009;16:1331–1336. doi: 10.1245/s10434-009-0355-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Narayanaswamy R.K., Potharaju M., Vaidhyswaran A.N., Perumal K. Pre-radiotherapy haemoglobin level is a prognosticator in locally advanced head and neck cancers treated with concurrent chemoradiation. JCDR. 2015;9(6):XC14–XC18. doi: 10.7860/JCDR/2015/11593.6102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Su N.W., Liu C.J., Leu Y.S., Lee J.C., Chen Y.J., Chang Y.F. Prolonged radiation time and low nadir hemoglobin during postoperative concurrent chemoradiotherapy are both poor prognostic factors with synergistic effect on locally advanced head and neck cancer patients. Onco Targets Ther. 2015;8:251–258. doi: 10.2147/OTT.S70204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hoff C.M. Importance of hemoglobin concentration and its modification for the outcome of head and neck cancer patients treated with radiotherapy. Acta Oncol. 2012;51(4):419–432. doi: 10.3109/0284186X.2011.653438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Denis F., Garaud P., Bardet E. Final results of the 94-01 French head and neck oncology and radiotherapy group randomized trial comparing radiotherapy alone with concomitant radiochemotherapy in advanced-stage oropharynx carcinoma. J Clin Oncol. 2004;22(1):69–76. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2004.08.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Landberg T., Chavaudra J., Dobbs J. Report 50. J ICRU. 1993;26(1) doi: 10.1093/jicru/os26.1.Report50. Available at: [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Landberg T., Chavaudra J., Dobbs J. Report 62. J ICRU. 1999;32(1) doi: 10.1093/jicru/os32.1.Report62. Available at: [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Report 83. J ICRU 2010;10(1). Available at: 10.1093/jicru/10.1.Report83. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 16.Nordsmark M., Bentzen S., Rudat V. Prognostic value of tumor oxygenation in 397 head and neck tumors after primary radiation therapy. An international multi-center study. Radiother Oncol. 2005;7(1):18–24. doi: 10.1016/j.radonc.2005.06.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bredell M.G., Ernst J., El-Kochaire I., Dahlem Y., Ikenberg K., Schumann D.M. Current relevance of hypoxia in head and neck cancer. Oncotarget. 2016;7(31):50781–50804. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.9549. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Molich Hoff C., Hansen H.S., Overgaard M. The importance of haemoglobin level and effect of transfusion in HNSCC patients treated with radiotherapy – results from the randomized DAHANCA 5. Radiother Oncol. 2011;98(1):28–33. doi: 10.1016/j.radonc.2010.09.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Baghi M., Wagenblast J., Hambek M. Pre-treatment haemoglobin level predicts response and survival after TPF induction polychemotherapy in advanced head and neck cancer patients. Clin Otolaryngol. 2008;33(3):245–251. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-4486.2008.01702.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Topkan E., Ekici N.Y., Ozdemir Y. Baseline hemoglobin <11.0 g/dL has stronger prognostic value than anemia status in nasopharynx cancers treated with chemoradiotherapy. Int J Biol Markers. 2019;34(2):139–147. doi: 10.1177/1724600818821688. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Vaupel P., Mayer A., Hockel M. Impact of hemoglobin levels on tumor oxygenation the higher, the better? Strahlenther Onkol. 2006;18(2):1543–1547. doi: 10.1007/s00066-006-1543-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Overgaard J., Hoff C.M., Hansen H.S. DAHANCA 10 - Effect of darbepoetin alfa and radiotherapy in the treatment of squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck. A multicenter, open-label, randomized, phase 3 trial by the Danish head and neck cancer group. Radiother Oncol. 2018;127(1):12–19. doi: 10.1016/j.radonc.2018.02.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hassan Metwally M.A., Ali R., Kuddu M. IAEA-HypoxX. A randomized multicenter study of the hypoxic radiosensitizer nimorazole concomitant with accelerated radiotherapy in head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. Radiother Oncol. 2015;116(1):15–20. doi: 10.1016/j.radonc.2015.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bentzen J., Toustrup K., Eriksen J.G., Primdahl H., Andersen L.J., Overgaard J. Locally advanced head and neck cancer treated with accelerated radiotherapy, the hypoxic modifier nimorazole and weekly cisplatin. Results from the DAHANCA 18 phase II study. Acta Oncol. 2015;54(7):1001–1007. doi: 10.3109/0284186X.2014.992547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Stieb S., Eleftheriou A., Warnock G., Guckenberger M., Riesterer O. Longitudinal PET imaging of tumor hypoxia during the course of radiotherapy. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2018;45(12):2201–2217. doi: 10.1007/s00259-018-4116-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Holf C.M., Grau C., Overgaard J. Effect of smoking on oxygen delivery and outcome in patients treated with radiotherapy for head and neck squamous cell carcinoma – a prospective study. Radiother Oncol. 2012;103(1):38–44. doi: 10.1016/j.radonc.2012.01.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.St. Lezin E., Karafin M.S., Bruhn R. Therapeutic impact of red blood cell transfusion on anemic outpatients: the RETRO study. Transfusion (Paris) 2019;59(6):1934–1943. doi: 10.1111/trf.15249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gorphe P., Idrissi Y.C., Tao Y. Anemia and neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio are prognostic in p16-positive oropharyngeal carcinoma treated with concurrent chemoradiation. Papillomavirus Res. 2018;5:32–37. doi: 10.1016/j.pvr.2017.12.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]