Abstract

Objective:

The purpose of this study was to determine the effects of surgical resection of muscle layer on the long-term survival of patients with hypertrophic obstructive cardiomyopathy (HOCM).

Methods:

The original study cohort consisted of 552 patients with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy (HCM), including 380 patients with HOCM and 172 patients with nonobstructive HCM. All these patients had a definite diagnosis in our center from October 1, 2009, to December 31, 2012. They were divided into three groups, viz., HOCM with myectomy group (n=194), nonoperated HOCM group (n=186), and nonobstructive HCM group (n=172). Median follow-up duration was 57.57±13.71 months, and the primary end point was a combination of mortality from all causes.

Results:

In this survival study, we compared the prognoses of patients with HOCM after myectomy, patients with nonoperated HOCM, and patients with nonobstructive HCM. Among the three groups, the myectomy group showed a lower rate of reaching the all-cause mortality with statistically indistinguishable overall survival compared with patients with nonobstructive HCM (p=0.514). Among patients with left ventricular outflow tract (LVOT) obstruction, the overall survival in the myectomy group was noticeably better than that in the nonoperated HOCM group (log-rank p<0.001). Parameters that showed a significant univariate correlation with survival included age, previous atrial fibrillation (AF), NT-proBNP, Cr, myectomy, and LV ejection fraction. When these variables were entered in the multivariate model, the only independent predictors of survival were myotomy [hazard ratio (HR): 0.109; 95% CI: 0.013–0.877, p<0.037], age (HR: 1.047; 95% CI: 1.007–1.088, p=0.021), and previous AF (HR: 2.659; 95% CI: 1.022–6.919, p=0.021).

Conclusion:

Patients with HOCM undergoing myectomy appeared to suffer from a lower risk of reaching the all-cause mortality and demonstrated statistically indistinguishable overall survival compared with patients with nonobstructive HCM. Multivariate analysis clearly demonstrated myectomy as a powerful, independent factor of survival, confirming that the differences in long-term survival recorded in this study may be due to surgical improvement in the LVOT gradient.

Keywords: hypertrophic obstructive cardiomyopathy, myectomy, prognosis

Introduction

Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy (HCM) is a genetic heart disease characterized by cardiomyocyte hypertrophy and interstitial fibrosis accompanied by ventricular muscle thickening, which primarily involves the left ventricle and the interventricular septum (1). Patients with HCM suffer a higher risk of developing heart failure and ventricular arrhythmias than the normal population, and accumulating increasing evidence suggests that HCM is the leading cause of sudden cardiac death in young individuals (2). Obstruction of flow in the left ventricular outflow tract (LVOT) is detected in approximately 70% of patients with HCM, referred to as hypertrophic obstructive cardiomyopathy (HOCM) (3). Although medical treatment can provide relief of symptoms, a considerable proportion of patients with HOCM remain symptomatic, for whom invasive treatment (primarily surgical septum myectomy) is a reputable treatment option (4, 5). For more than 40 years, surgical septum resection as the primary treatment approach for patients with HOCM has been effectively implemented, and a large number of long-term symptomatic and hemodynamic benefits can be obtained from the operation (6-9). Surgical septum myectomy is considered as a gold standard strategy for relieving refractory symptoms in patients with HOCM. However, surgical myectomy is generally performed in large medical centers where not all patients can have access, and the beneficial effect on long-term survival still remains a question that requires more clinical evidence than drug-managed patients with HOCM. In this study, we compared the long-term results of a series of major surgeries with those of patients with HOCM treated with a group of drugs and the expected survival rates of patients with nonobstructive HCM. We attempted to explore whether the improvement in LVOT obstruction by surgical septum myectomy has clinical benefits other than improving the quality of life. Herein, we report our comprehensive experience of both procedures, including perioperative complications, survival, and clinical outcome.

Methods

Ethics statement

This study was conducted in accordance with the ethical standards of the Declaration of Helsinki and China’s clinical practice regulations and guidelines. It was also approved by the Ethics Committee of Zhengzhou University People’s Hospital (Henan Provincial People’s Hospital, the Central China Fuwai Hospital, and Central China Branch of the National Cardiovascular Center; these four institutions are the same organization). Before the start of the study, written informed consents were obtained from all participants.

Study patients

All patients in this study were evaluated at Zhengzhou University People’s Hospital between October 1, 2009, and December 31, 2012. There were 552 patients (age ≥16 years) diagnosed with HCM, including 380 patients with HOCM and 172 patients with nonobstructive HCM. Patients with complete clinical information and medical history details, as well as those with any heart or systemic disease that significantly enlarged the magnitude of evident hypertrophy, such as uncontrolled hypertension (blood pressure monitoring ≥140/90 mm Hg), cardiac valve disease, amyloidosis, and congenital heart disease, were selected. Among these patients, 194 patients with HOCM accepted to undergo surgical myectomy. The diagnosis of HCM was made as described previously as follows (10-12): 1, wall thickness of one or more left ventricular myocardial segments ≥15 mm, measured by any imaging technique (echocardiography, computed tomography, or cardiac magnetic resonance imaging); 2, wall thickness (13–14 mm) with family history, electrocardiogram (ECG) abnormalities, noncardiac symptoms and signs, laboratory tests, and multimodality cardiac imaging; 3, diagnosis of HOCM, in addition to the two requirements of appeal, the following criteria must be met: patients with LVOT obstruction were diagnosed based on dynamic LVOT obstruction caused by anterior systolic displacement of mitral valve, with LVOT gradient ≥30 mm Hg at rest or during physiological provocation (such as the Valsalva maneuver, standing, and exercise). Significant dynamic LVOT obstruction was recorded by two-dimensional and Doppler echocardiography or, in the case of insufficient echocardiography, through invasive hemodynamic catheterization.

Despite maximum tolerance to medication, invasive therapy should be considered in patients with resting or irritating, moderate-to-severe symptoms [New York Heart Association (NYHA) ≥ III–IV] and/or recurrent exertional syncope to reduce the left ventricular oxygen saturation gradient of 50 mm Hg. After discussing the benefits and risks of each option, the choice of surgical resection was made through a common decision-making process.

Follow-up and endpoints

The follow-up began at the time of the first clinic contact of the patients after October 1, 2009, at Zhengzhou University People’s Hospital. At baseline, all patients were assessed for the following characteristics: age, sex, maximum left ventricular wall thickness, maximum LVOT gradient, NYHA functional class, left ventricular function, atrial fibrillation, and conventional risk factors for sudden cardiac death.

The primary end point of this study was all-cause mortality during the long-term follow-up. Mortality and adverse events were retrieved from hospital patient records, civil service population registrations, and information provided by patients themselves and/or their general practitioners at the follow-up centers. Patients who lost to follow-up were reviewed the last time they contacted them. If no incident occurred during the follow-up, the date of administrative review was set as December 31, 2012.

Data analysis

The SPSS 21.0 statistical software package for Windows was used for statistical analysis. Normally distributed variables were presented as mean±SD and compared using independent samples t-test or one-way ANOVA. Non-normally distributed variables were analyzed using the Kruskal–Wallis test and expressed as median values with interquartile range (IQR). Categorical variables were expressed as frequencies and percentages. The chi-square test was used to compare categorical variables. The hazard ratio (HR) was estimated by the Cox proportional hazard model. The Kaplan–Meier analysis was used to determine the cumulative survival of different groups. A p value <0.05 was considered to be statistically significant.

Results

Characteristics of study population and baseline clinical characteristics

From October 1, 2009, to December 31, 2012, a total of 552 consecutive patients with HCM (aged ≥16 years) were admitted to Zhengzhou University People’s Hospital, who included 380 patients with HOCM and 172 patients with nonobstructive HCM. Among the 380 patients with HOCM, 194 accepted to undergo surgical myectomy, and the remaining 186 patients with HOCM were medically managed. The 172 patients with nonobstructive HCM, without invasive treatment, accepted to receive the conventional method of medical management. Table 1 shows the baseline characteristics of the three treatment groups. According to the choice of treatment measures, the population was divided into three groups. The myotomy group had the highest NT-ProBNP level, the highest NYHA Class III or IV, the lowest systolic blood pressure/diastolic blood pressure, and the lowest incidence of atrial fibrillation or nonpersistent ventricular tachycardia. (We have separately listed the use of anticoagulants in patients with HCM complicated with atrial fibrillation as supplementary materials in Supplement Table 1).

Table 1.

Baseline clinical and demographic characteristics of the three hypertrophic cardiomyopathy patient subgroups

| Total (n=552) | Myectomy (n=194) | Nonoperated obstructive (n=186) | Nonobstructive (n=172) | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Demographics | |||||

| Age, y | 52.51±13.23 | 46.139±11.73 | 54.31±13.18 | 57.74±11.97 | 0.051 |

| Male, n (%) | 363 (65.8%) | 120 (61.9%) | 115 (61.8%) | 128 (74.4%) | 0.016 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 25.63±4.00 | 25.10±3.79 | 26.03±4.60 | 25.91±3.52 | 0.252 |

| Smoking, n (%) | 275 (49.8%) | 90 (46.4%) | 94 (50.5%) | 91 (52.9%) | 0.441 |

| Systolic BP (mm Hg) | 120.00 (110.00, 130.00) | 105.00 (120.00, 125.00) | 120.00 (120.00, 137.00) | 125.00 (120.00, 140.00) | <0.001 |

| Diastolic BP (mm Hg) | 75.00 (70.00, 80.00) | 70.00(60.00, 80.00) | 80.00 (70.00, 80.00) | 80.00 (70.00, 80.00) | <0.001 |

| NT-proBNP (fmol/mL) | 1312.80 (741.48, 2285.77) | 1534.10 (972.63, 2584.90) | 1185.30 (689.50, 2149.00) | 1076.20 (657.30, 1953.30) | 0.004 |

| Cr (μmol/L) | 77.65 (67.15, 92.41) | 75.98 (65.33, 92.64) | 74.91 (64.42, 86.40) | 82.30 (71.52, 96.12) | <0.001 |

| Comorbidities and risk factors | |||||

| Hypertension, n (%) | 221 (40.0%) | 38 (19.6%) | 91 (48.9%) | 89 (51.7%) | <0.001 |

| Diabetes mellitus, n (%) | 48 (8.7%) | 3 (1.5%) | 13 (7.0%) | 32 (18.6%) | <0.001 |

| Dyslipidemia, n (%) | 221 (38.2%) | 34 (17.5%) | 81 (43.5%) | 96 (55.8%) | <0.001 |

| Atrial fibrillation, n (%) | 101 (18.3%) | 20 (10.3%) | 37 (19.9%) | 44 (25.6%) | <0.001 |

| Nonsustained ventricular tachycardia, n (%) | 31 (5.6%) | 3 (1.5%) | 9 (4.8%) | 19 (11.0%) | <0.001 |

| Coronary artery disease, n (%) | 142 (25.7%) | 27 (13.9%) | 46 (24.7%) | 69 (40.1%) | <0.001 |

| Clearly family history of HCM, n (%) | 24 (4.3%) | 8 (4.1%) | 8 (4.3%) | 8 (4.7%) | 0.970 |

| NYHA Class III or IV, n (%) | 73 (13.2%) | 34 (17.5%) | 22 (11.9%) | 17 (9.9%) | 0.246 |

| Echocardiography | |||||

| Mitral regurgitation (Moderate and severe), n (%) | 95 (17.2%) | 68 (35.1%) | 22 (11.8%) | 5 (2.9%) | <0.001 |

| Interventricularseptal thickness (mm) | 19.00 (16.00, 22.00) | 20.00 (16.75, 23.00) | 18.00 (16.00, 23.00) | 18.00 (16.00, 21.00) | 0.018 |

| LV end-diastolic diameter (mm) | 43.00 (39.00, 47.00) | 42.00 (39.00, 46.00) | 42.00 (39.00, 46.00) | 45.00 (41.00, 49.00) | <0.001 |

| LV posterior wall thickness (mm) | 11.00 (10.00, 13.00) | 12.00 (10.00, 14.00) | 11.00 (10.00, 14.00) | 11.00 (10.00, 12.00) | <0.001 |

| LV ejection fraction (%) | 67.00 (60.00, 72.00) | 65.00 (60.00, 70.00) | 70.00 (65.00, 75.00) | 65.00 (60.00, 70.00) | <0.001 |

| LV outflow tract gradient, at rest (mmHg) | 52.00 (10.20, 86.00) | 81.00 (58.00, 100.00) | 57.80 (36.00, 88.00) | 6.80 (4.80,9.00) | <0.001 |

| LV outflow tract gradient, during physiological provocation (mm Hg) | 96.05±46.18 | 108.94±39.02 | 89.71±48.15 | -- | -- |

| Medications | |||||

| Beta-blocker, n (%) | 330 (59.8%) | 94 (48.5%) | 113 (60.8%) | 123 (71.5%) | <0.001 |

| ACEI/ARB, n (%) | 103 (18.7%) | 8 (4.1%) | 31 (16.7%) | 64 (37.2%) | <0.001 |

| Statin, n (%) | 128 (23.2%) | 13 (6.7%) | 44 (23.7%) | 71 (41.3%) | <0.001 |

| Calcium antagonist, n (%) | 149 (27.0%) | 22 (11.3%) | 64 (34.4%) | 63 (36.6%) | <0.001 |

| Implantable cardioverter defibrillator/pacemaker | 34 (6.2%) | 5 (2.6%) | 17 (9.1%) | 12 (7.0%) | 0.012 |

Values are mean±SD or interquartile range (IQR), n (%).

BMI - body mass index; NT-proBNP - N-terminal pro-brain natriuretic peptide; Cr - serum creatinine; BP - blood pressure; NYHA - New York Heart Association; LV - left ventricle; ACEI/ARB - angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor/angiotensin receptor blocker

Supplement Table 1.

The use of anticoagulants in HCM patients with atrial fibrillation

| Total | Myectomy group | Nonoperated obstructive group | Nonobstructive group | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Atrial fibrillation | 101 | 20 | 37 | 44 |

| Warfarin | 37 | 8 | 12 | 17 |

| Dabigatranetexilate | 2 | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| Rivaroxaban | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| Bayaspirin+Clopidogrel | 4 | 1 | 1 | 2 |

| Warfarin+Bayaspirin+Clopidogrel | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Warfarin+Bayaspirin | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| Bayaspirin | 29 | 5 | 13 | 11 |

| No anticoagulant or antiplatelet drugs | 26 | 6 | 8 | 12 |

The interventricular septal thickness LVOT pressure difference (resting state) and the LVOT pressure difference (physiological stimulation) in the myotomy group were slightly higher than those in the other two groups. Significant differences were noted in sex, history of hypertension, history of diabetes, history of dyslipidemia, and history of medication among the three groups. Age, smoking, family history, HCM, NYHA grade, and body mass index level showed no significant differences among the three groups.

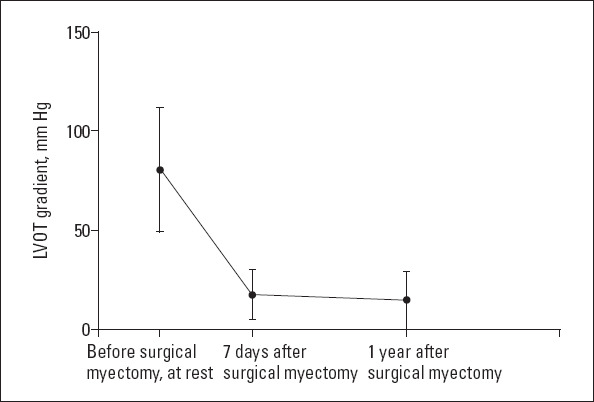

Clinical benefits of myectomy

In the myectomy group, the symptoms and hemodynamics were significantly improved after myectomy. The mean resting outflow gradient decreased from 80.47±31.31 to 17.51±14.00 mm Hg (7 days after operation) and 15.05±14.39 mm Hg (1 year after operation) (Fig. 1).

Figure 1.

The average LVOT gradient before and after surgical septum myectomy

Survival comparisons in patients with HOCM

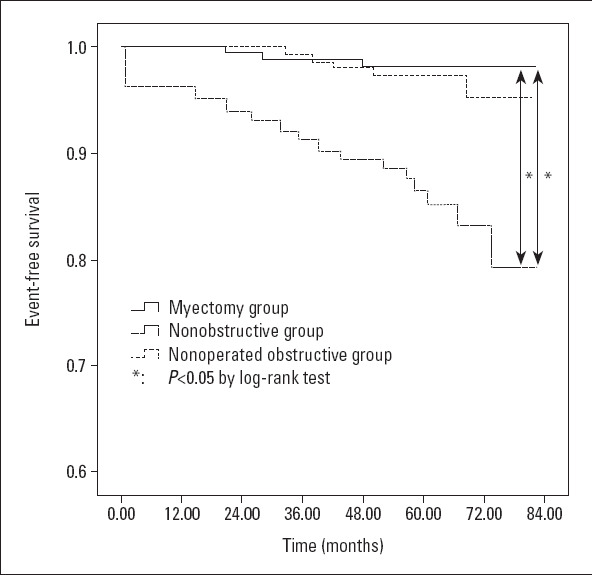

Among patients with LVOT obstruction (n=380), the overall survival rate of patients undergoing myomectomy was significantly better than that of patients with nonoperative HOCM (log-rank p<0.001, Fig. 2). Baseline parameters that showed a significant univariate correlation with survival included myotomy (HR: 0.119; 95% CI: 0.036–0.396, p=0.001), age (HR: 1.095; 95% CI: 1.095–1.131, p<0.001), previous atrial fibrillation (AF) (HR: 3.680; 95% CI: 1.669–8.113, p=0.001), NT-proBNP (100 fmol/mL) (HR: 1.034; 95% CI: 1.018–1.051, p<0.001), Cr (μmol/L) (HR: 1.015; 95% CI: 1.002–1.028, p=0.02), and LV ejection fraction (HR: 0.964; 95% CI: 1.018–1.051, p<0.001) (Table 2). When these variables were entered into the multivariate model, the only independent predictors of survival were myectomy (HR: 0.109; 95% CI: 0.013–0.877, p<0.037), age (HR: 1.047; 95% CI: 1.007–1.088, p=0.021), and previous AF (HR: 2.659; 95% CI: 1.022–6.919, p=0.021) (Table 2).

Figure 2.

Event-free survival

Table 2.

Univariate Cox analysis and multivariate Cox analysis for all-cause mortality in patients with HOCM

| Parameter | Univariate HR (95% CI) | P value | Multivariate HR (95% CI) | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 1.095 (1.059, 1.131) | <0.001 | 1.047 (1.007, 1.088) | 0.021 |

| Male | 0.536 (0.248, 1.157) | 0.112 | -- | -- |

| Previous AF | 3.680 (1.669, 8.113) | 0.001 | 2.659 (1.022, 6.919) | 0.045 |

| Coronary artery disease | 1.034 (0.534, 2.271) | 0.794 | -- | -- |

| Nonsustained ventricular tachycardia | 1.479 (0.200, 10.923) | 0.701 | -- | -- |

| NT-proBNP (100 fmol/mL) | 1.034 (1.018, 1.051) | <0.001 | 1.030 (1.006, 1.054) | 0.097 |

| Cr (μmol/L) | 1.015 (1.002, 1.028) | 0.02 | 1.000 (0.949, 1.017) | 0.987 |

| Baseline septal thickness, mm | 0.952 (0.880, 1.031) | 0.226 | -- | -- |

| LV ejection fraction (%) | 0.964 (0.934, 0.994) | <0.001 | 0.990 (0.949, 1.033) | 0.646 |

| LV end-diastolic diameter (mm) | 1.049 (0.998, 1.102) | 0.058 | -- | -- |

| Myectomy | 0.119 (0.036, 0.396) | 0.001 | 0.109 (0.013, 0.877) | 0.037 |

NT-proBNP - N-terminal pro-brain natriuretic peptide; Cr - serum creatinine; LV - left ventricle

Survival after myectomy

During the median follow-up period of 55.82±11.39 months, 3 patients (1.5%) died, including 1 patient (0.5%) who died of operation and the other 2 cases may have died of myocardial infarction (cardiogenic death). The average age at death was 50±17 years (range, 31–61 years), and death occurred at 25.19±23.49 months (range, 0.37–47.07 months) after myectomy (Table 3).

Table 3.

Clinical outcome at the end of study

| Total (n=552) | Myectomy (n=194) | Nonoperated obstructive (n=186) | Nonobstructive (n=172) | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Follow-up duration, Mos. | 57.57±13.71 | 55.82±11.39 | 55.58±17.28 | 61.46±11.07 | <0.001 |

| Periprocedural death | 1 (<1%) | 1 (<1%) | 0 | 0 | -- |

| Cardiac death | 21 (3.8%) | 2 (1.0%) | 14 (7.5%) | 5 (2.9%) | -- |

| Stroke | 2 (<1%) | 0 | 2 | 0 | -- |

| Unexplained death | 7 (1.2%) | 0 | 7 (3.8%) | 0 | -- |

| (The patients died outside the hospital, and the family members could not provide the details of the patient’s death.) All-cause mortality | 31 (5.6%) | 3 (1.5%) | 23 (12.4%) | 5 (2.9%) | <0.001 |

Survival comparisons including patients with obstructive and nonobstructive HCM

The survival of patients with obstructive hypertrophic myocardial infarction and that of patients with nonobstructive hypertrophic myocardial infarction were compared. Results showed that compared with patients with nonobstructive HCM, the myectomy group of patients showed no statistical difference in the overall survival (p=0.514) (Fig. 2). Among the three groups, patients with nonoperated HOCM suffered the highest risk of reaching the all-cause mortality (Fig. 2; vs. myectomy group, p<0.001, by log-rank test; vs. nonobstructive HCM group, p<0.001, by log-rank test).

Discussion

In this long-term survival study, we compared the prognoses of patients with HOCM after myectomy, patients with nonoperated HOCM, and patients with nonobstructive HCM. Among the three groups, the myectomy group was associated with a lower rate of reaching the all-cause mortality and demonstrated statistically indistinguishable overall survival compared with patients with nonobstructive HCM (p=0.514). Among patients with LVOT obstruction, the overall survival of patients in the myectomy group was significantly better than that of patients with nonoperated HOCM (log-rank p<0.001, Fig. 2). The parameters with a significant univariate association with survival included myectomy, age, previous AF, NT-proBNP, Cr (HR: 1.015; 95% CI: 1.002–1.028, p=0.02), and LV ejection fraction, When these variables were entered into the multivariate model, the only independent predictors of survival were myectomy (HR: 0.109; 95% CI: 0.013–0.877, p<0.037), age (HR: 1.047; 95% CI: 1.007–1.088, p=0.021), and previous AF (HR: 2.659; 95% CI: 1.022–6.919, p=0.021). The LVOT gradient of patients with HOCM showed significant amelioration after myectomy, and this improvement acted quickly and persistently (Fig. 1).

Hemodynamic and clinical results were consistent, in all respects, with those observed at other established HCM centers with longstanding myectomy programs (5, 13-19). For example, the LVOT obstruction basically disappeared, and in patients with a small gradient of 1.2±6.8 mm Hg, 94% of them showed improvement in the NYHA function in grade I or II due to the normalization of intraventricular LV pressure and the decrease of related mitral regurgitation. In addition, compared with obstruction, the clinical improvement after myectomy was comparable in resting patients, similar to previous surgical experience. Therefore, it is important to emphasize that when operated by experienced surgeons, muscle resection can continuously reverse the process of heart failure, generally returning the patients to normal (or near-normal) levels of activity and quality of life. A small number of clinically unresponsive patients who did not respond to myectomy were defined as patients with persistent postoperative NYHA III symptoms, although the surgery alleviated the outflow gradient. The determinant of this clinical process has not yet been completely resolved, but it is probably due to the primary role of diastolic dysfunction in symptom development. As a result of accumulated experience and improved myocardial protection techniques, the surgical mortality associated with myectomy has been significantly reduced from the initial surgical report (13). At present, in experienced centers, the procedural risk is 1%–2%, in fact, close to 0% in recent patients (20-25). In this study, periprocedural death occurred in one patient (0.5%), and approached to previous reports (13, 17). Furthermore, the long-term survival rate of patients with HOCM after myectomy was high, equivalent to the survival rate of patients with nonobstructive HCM. It is also reasonable to assume that heart failure will inevitably develop into death and/or severe disability. These data confirm that myectomy conveys the benefits of survival by alleviating the impedance of outflow and normalizing left ventricular pressure and mitral regurgitation.

Inevitably, it is impossible to strictly match myectomy and nonsurgical patients. However, we believe that statistical comparisons and conclusions are effective and clinically relevant. First, there was no significant difference in postoperative survival between patients with myotomy and patients with nonobstructive HCM. Second, the multivariate analysis clearly identified myectomy as a powerful, independent determinant of survival, confirming that the differences in long-term survival recorded here may be due to surgical relief of the LVOT gradient. Third, despite the significant aggravation of preoperative symptoms, the long-term survival rate of patients undergoing myectomy was much higher than that of patients with nonoperated HOCM with fewer symptoms.

Study limitations

Like all previous studies that evaluated myotomy, this investigation is a nonrandomized observational study. In particular, there is a significant difference in the average age among the three groups, indicating that selection bias plays a major role. One of the advantages of this study is the long-term follow-up and data integrity. An extensive search was conducted for all hospital records and surgical reports of all patients, and the examination of complications was completed. A questionnaire survey and telephone consultation, if necessary, were used to obtain more objective results of the patients’ symptom status during late follow-up. Finally, unlike several other studies, the advantage of this research is that perioperative complications and long-term results are analyzed in a single study. Since the direct cause of death was not available to us in some cases, we were not able to assess the survival rate of specific HCM-related deaths.

Conclusion

Patients with HOCM undergoing myectomy appeared to suffer from a lower risk of reaching the all-cause mortality and demonstrated statistically indistinguishable overall survival compared with patients with nonobstructive HCM. Multivariate analysis clearly demonstrated myectomy as a powerful, independent factor of survival, confirming that the differences in long-term survival recorded in this study may be due to surgical improvement in the LVOT gradient.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest: None declared.

Peer-review: Externally peer-reviewed.

Authorship contributions: Concept – C.G.; Design – X.M., M.L.; Supervision – X.M., C.G.; Fundings – X.M., M.L., Y.S., S.Z., C.G.; Materials – M.L., Y.S., S.Z., W.Z.; Data collection and/or processing – M.L., Y.S., S.Z., W.Z.; Analysis and/or interpretation – X.M., M.L.; Literature search – C.G.; Writing – X.M., M.L.; Critical review – X.M., M.L., S.Z., W.Z.

References

- 1.Semsarian C, Ingles J, Maron MS, Maron BJ. New perspectives on the prevalence of hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2015;65:1249–54. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2015.01.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sen-Chowdhry S, Jacoby D, Moon JC, McKenna WJ. Update on hypertrophic cardiomyopathy and a guide to the guidelines. Nat Rev Cardiol. 2016;13:651–75. doi: 10.1038/nrcardio.2016.140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Maron BJ, Maron MS. Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. Lancet. 2013;381:242–55. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)60397-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nagueh SF, Groves BM, Schwartz L, Smith KM, Wang A, Bach RG, et al. Alcohol septal ablation for the treatment of hypertrophic obstructive cardiomyopathy. A multicenter North American registry. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2011;58:2322–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2011.06.073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ball W, Ivanov J, Rakowski H, Wigle ED, Linghorne M, Ralph-Edwards A, et al. Long-term survival in patients with resting obstructive hypertrophic cardiomyopathy comparison of conservative versus invasive treatment. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2011;58:2313–21. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2011.08.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kirklin JW, Ellis FH., Jr Surgical relief of diffuse subvalvular aortic stenosis. Circulation. 1961;24:739–42. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.24.4.739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Morrow AG, Reitz BA, Epstein SE, Henry WL, Conkle DM, Itscoitz SB, et al. Operative treatment in hypertrophic subaortic stenosis. Techniques, and the results of pre and postoperative assessments in 83 patients. Circulation. 1975;52:88–102. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.52.1.88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Schönbeck MH, Brunner-La Rocca HP, Vogt PR, Lachat ML, Jenni R, Hess OM, et al. Long-term follow-up in hypertrophic obstructive cardiomyopathy after septal myectomy. Ann Thorac Surg. 1998;65:1207–14. doi: 10.1016/s0003-4975(98)00187-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Merrill WH, Friesinger GC, Graham TP, Jr, Byrd BF, 3rd, Drinkwater DC, Jr, Christian KG, et al. Long-lasting improvement after septal myectomy for hypertrophic obstructive cardiomyopathy. Ann Thorac Surg. 2000;69:1732–5. doi: 10.1016/s0003-4975(00)01314-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gersh BJ, Maron BJ, Bonow RO, Dearani JA, Fifer MA, Link MS, et al. American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines;American Association for Thoracic Surgery;American Society of Echocardiography;American Society of Nuclear Cardiology;Heart Failure Society of America;Heart Rhythm Society;Society for Cardiovascular Angiography and Interventions;Society of Thoracic Surgeons. 2011 ACCF/AHA guideline for the diagnosis and treatment of hypertrophic cardiomyopathy:a report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. Circulation. 2011;124:e783–831. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0b013e318223e2bd. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Elliott PM, Anastasakis A, Borger MA, Borggrefe M, Cecchi F, et al. Authors/Task Force members. 2014 ESC Guidelines on diagnosis and management of hypertrophic cardiomyopathy:the Task Force for the Diagnosis and Management of Hypertrophic Cardiomyopathy of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) Eur Heart J. 2014;35:2733–79. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehu284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zhang K, Meng X, Wang W, Zheng J, An S, Wang S, et al. Prognostic Value of Free Triiodothyronine Level in Patients With Hypertrophic Obstructive Cardiomyopathy. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2018;103:1198–205. doi: 10.1210/jc.2017-02386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ommen SR, Maron BJ, Olivotto I, Maron MS, Cecchi F, Betocchi S, et al. Long-term effects of surgical septal myectomy on survival in patients with obstructive hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2005;46:470–6. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2005.02.090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Woo A, Williams WG, Choi R, Wigle ED, Rozenblyum E, Fedwick K, et al. Clinical and echocardiographic determinants of long-term survival after surgical myectomy in obstructive hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. Circulation. 2005;111:2033–41. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000162460.36735.71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Smedira NG, Lytle BW, Lever HM, Rajeswaran J, Krishnaswamy G, Kaple RK, et al. Current effectiveness and risks of isolated septal myectomy for hypertrophic obstructive cardiomyopathy. Ann Thorac Surg. 2008;85:127–33. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2007.07.063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Desai MY, Bhonsale A, Smedira NG, Naji P, Thamilarasan M, Lytle BW, et al. Predictors of long-term outcomes in symptomatic hypertrophic obstructive cardiomyopathy patients undergoing surgical relief of left ventricular outflow tract obstruction. Circulation. 2013;128:209–16. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.112.000849. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sedehi D, Finocchiaro G, Tibayan Y, Chi J, Pavlovic A, Kim YM, et al. Long-term outcomes of septal reduction for obstructive hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. J Cardiol. 2015;66:57–62. doi: 10.1016/j.jjcc.2014.08.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Liebregts M, Vriesendorp PA, Mahmoodi BK, Schinkel AF, Michels M, ten Berg JM. A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Long-Term Outcomes After Septal Reduction Therapy in Patients With Hypertrophic Cardiomyopathy. JACC Heart Fail. 2015;3:896–905. doi: 10.1016/j.jchf.2015.06.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Maron BJ, Dearani JA, Ommen SR, Maron MS, Schaff HV, Nishimura RA, et al. Low Operative Mortality Achieved With Surgical Septal Myectomy:Role of Dedicated Hypertrophic Cardiomyopathy Centers in the Management of Dynamic Subaortic Obstruction. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2015;66:1307–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2015.06.1333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Maron BJ, McKenna WJ, Danielson GK, Kappenberger LJ, Kuhn HJ, Seidman CE, et al. Task Force on Clinical Expert Consensus Documents. American College of Cardiology;Committee for Practice Guidelines. European Society of Cardiology. American College of Cardiology/European Society of Cardiology clinical expert consensus document on hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. A report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation Task Force on Clinical Expert Consensus Documents and the European Society of Cardiology Committee for Practice Guidelines. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2003;42:1687–713. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(03)00941-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.van der Lee C, Kofflard MJ, van Herwerden LA, Vletter WB, ten Cate FJ. Sustained improvement after combined anterior mitral leaflet extension and myectomy in hypertrophic obstructive cardiomyopathy. Circulation. 2003;108:2088–92. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000092912.57140.14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ommen SR, Thomson HL, Nishimura RA, Tajik AJ, Schaff HV, Danielson GK. Clinical predictors and consequences of atrial fibrillation after surgical myectomy for obstructive hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. Am J Cardiol. 2002;89:242–4. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9149(01)02213-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ommen SR, Park SH, Click RL, Freeman WK, Schaff HV, Tajik AJ. Impact of intraoperative transesophageal echocardiography in the surgical management of hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. Am J Cardiol. 2002;90:1022–4. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9149(02)02694-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nagueh SF, Ommen SR, Lakkis NM, Killip D, Zoghbi WA, Schaff HV, et al. Comparison of ethanol septal reduction therapy with surgical myectomy for the treatment of hypertrophic obstructive cardiomyopathy. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2001;38:1701–6. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(01)01614-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Qin JX, Shiota T, Lever HM, Kapadia SR, Sitges M, Rubin DN, et al. Outcome of patients with hypertrophic obstructive cardiomyopathy after percutaneous transluminal septal myocardial ablation and septal myectomy surgery. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2001;38:1994–2000. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(01)01656-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]