Significance

How plants respond and adjust their growth to cope with environmental changes is a long-standing question in biology. By studying the initial dark-to-light transition, we reveal that a microprotein-imposed suppression of protein activity is adopted by plants to achieve rapid switch from skotomorphogenic to photomorphogenic programs. Microproteins are essential bioactive regulators in animals. A large number of microproteins are predicted in plants, but very few of them are functionally characterized. We identified two microproteins that are tissue-specifically stimulated by light and directly disrupt the oligomerization of key transcription factors in light signaling. This microprotein-directed allosteric deactivation can be utilized to develop versatile tools for posttranslational regulation of target proteins in molecular breeding.

Keywords: light signaling, protein oligomerization, microprotein, PIFs, EIN3/EIL1

Abstract

Buried seedlings undergo dramatic developmental transitions when they emerge from soil into sunlight. As central transcription factors suppressing light responses, PHYTOCHROME-INTERACTING FACTORs (PIFs) and ETHYLENE-INSENSITIVE 3 (EIN3) actively function in darkness and must be promptly repressed upon light to initiate deetiolation. Microproteins are evolutionarily conserved small single-domain proteins that act as posttranslational regulators in eukaryotes. Although hundreds to thousands of microproteins are predicted to exist in plants, their target molecules, biological roles, and mechanisms of action remain largely unknown. Here, we show that two microproteins, miP1a and miP1b (miP1a/b), are robustly stimulated in the dark-to-light transition. miP1a/b are primarily expressed in cotyledons and hypocotyl, exhibiting tissue-specific patterns similar to those of PIFs and EIN3. We demonstrate that PIFs and EIN3 assemble functional oligomers by self-interaction, while miP1a/b directly interact with and disrupt the oligomerization of PIFs and EIN3 by forming nonfunctional protein complexes. As a result, the DNA binding capacity and transcriptional activity of PIFs and EIN3 are predominantly suppressed. These biochemical findings are further supported by genetic evidence. miP1a/b positively regulate photomorphogenic development, and constitutively expressing miP1a/b rescues the delayed apical hook unfolding and cotyledon development of plants overexpressing PIFs and EIN3. Our study reveals that microproteins provide a temporal and negative control of the master transcription factors' oligomerization to achieve timely developmental transitions upon environmental changes.

Light is one of the most important environmental factors that modulate plant growth and development (1–3). Terrestrial plant seeds often germinate in darkness under the cover of soil or fallen leaves. Utilizing the energy reserves in seeds, the germinated seedlings adopt a skotomorphogenic program in the dark, characterized by an elongated embryonic stem (hypocotyl), formation of an apical hook, and closed small etiolated cotyledons (4, 5). The skotomorphogenic strategy allows seedlings to quickly reach the soil surface and protect the fragile shoot apical meristem (6–8). Upon emergence, seedlings undergo a dramatic developmental transition toward the photomorphogenic program, including hypocotyl growth inhibition, apical hook unfolding, and cotyledon separation, expansion, and greening (4, 9, 10). This light-triggered transition is essential for plant survival and controlled by sophisticated gene regulation networks.

Distinct sets of photoreceptors are employed by plants to perceive various wavelengths of light. Phytochromes are red/far-red light receptors that sense and transduce light signals to produce a series of molecular and physiological changes (1, 11–13). Downstream of phytochromes, two groups of transcription factors, the basic helix–loop–helix (bHLH) PHYTOCHROME-INTERACTING FACTORs (PIFs) and plant-specific ETHYLENE-INSENSITIVE3 and EIN3-LIKE1 (EIN3/EIL1), act as key negative regulators of light signaling (14–16). PIFs and EIN3/EIL1 modulate a large number of light-regulated genes in a collaborative or independent manner. Dark-grown ein3 eil1 mutant displays compromised apical hook formation and pif1 pif3 pif4 pif5 mutant exhibits partially photomorphogenic phenotype, while combined mutations in EIN3/EIL1 and four PIF loci (pif1 pif3 pif4 pif5 ein3 eil1 sextuple mutant) result in constitutive photomorphogenesis in the dark (5, 17–21). PIFs and EIN3/EIL1 proteins accumulate abundantly in darkness and undergo rapid degradation induced by photoactivated phytochromes to initiate light responses (7, 13, 22).

In eukaryotic organisms, a large proportion of transcripts contain short open reading frames (sORFs) (23, 24). Extensive analyses of genomes, transcriptomes, and proteasomes reveal that some sORFs can be translated into small peptides or microproteins (miPs) (25, 26). There is growing evidence showing that miPs can function in multiple ways, including transcriptional repression, retention of proteins in the cytoplasm, and ion channel inhibition (25, 26). Genome-wide searches for potential miPs have been conducted according to three criteria: 1) a length of fewer than 140 amino acids; 2) the presence of a single protein domain capable of protein–protein interaction; and 3) sequence related to larger proteins (27–29). Although thousands of proteins fitting the criteria for classification as miPs have been identified in plants and animals, very few of them have been functionally characterized (30). Recently, two miPs, miP1a/BBX31 (encoded by AT3G21890) and miP1b/BBX30 (encoded by AT4G15248) (miP1a/b) with lengths of 121 and 117 amino acids, were experimentally validated in plants (29). Being classified into the BBX family, miP1a/b contain one B-box domain for protein–protein interaction, but lack the CCT domain responsible for DNA binding (29, 31–33). miP1a/b interact with CONSTANS (CO) and bridge CO into a repressor complex containing TOPLESS, thus inhibiting FLOWERING LOCUS T (FT) expression and causing late flowering (29).

In this study, we reveal that key transcription factors PIFs and EIN3/EIL1 act in oligomers to control light-regulated developmental programs. Upon light irradiation, miP1a/b are dramatically elevated and directly disrupt oligomerization of PIFs and EIN3, achieving rapid and specific repression of their DNA binding capacities. Therefore, light-activated miP1a/b enforce allosteric deactivation of PIFs and EIN3 to promote photomorphogenic development.

Results

The Tissue-Specific Expression Patterns of miP1a/b Are Similar to Those of PIFs and EIN3.

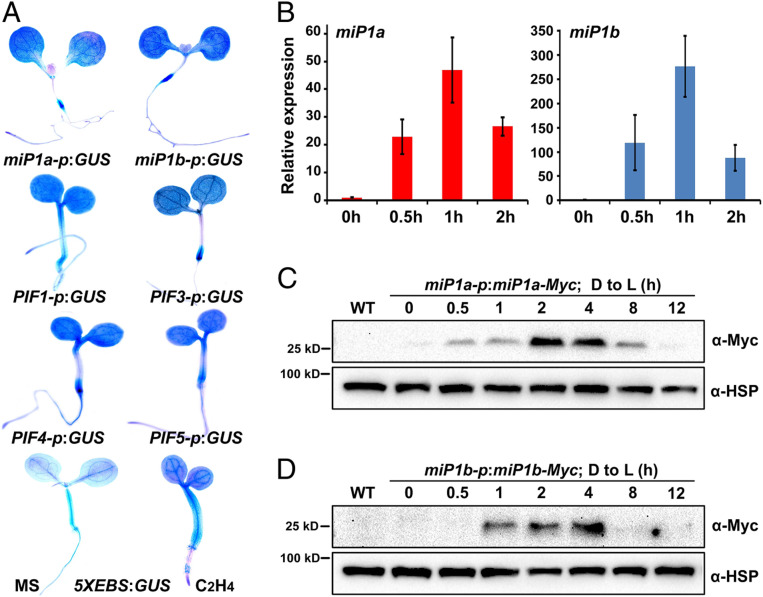

To dissect the roles of miP1a and miP1b in seedling development, we first adopted a GUS staining assay to characterize their tissue-specific expression patterns. We generated transgenic plants in which the GUS gene was driven by the promoter of miP1a or miP1b in the Col-0 (wild type [WT]) background. The cotyledons, cotyledon–hypocotyl junctions, and hypocotyl–root junctions of the miP1a-p:GUS/WT and miP1b-p:GUS/WT seedlings were highly stained (Fig. 1A). This staining pattern was similar to previously reported staining patterns for PIFs and EIN3 (5, 34, 35). Next, we examined the gene expression patterns of PIFs (PIF1, PIF3, PIF4, and PIF5) using PIF-p:GUS transgenic plants. All of the PIFs were primarily expressed in the cotyledons, cotyledon–hypocotyl junctions, and hypocotyl–root junctions, in which they showed expression patterns that were highly similar to those of miP1a/b (Fig. 1A). To determine the tissue-specific actions of EIN3, we utilized 5XEBS:GUS transgenic plants in which five EIN3 binding sequences in tandem were fused with the GUS reporter. Whole seedlings, including the cotyledons, hypocotyls, and roots, were stained, and ethylene treatment dramatically increased the intensity of GUS signals (Fig. 1A). These observations reveal that miP1a/b are tissue-specifically expressed in patterns that largely overlap with those of PIFs and EIN3.

Fig. 1.

Spatial and temporal expression patterns of miP1a and miP1b genes in Arabidopsis seedlings. (A) Representative images of GUS staining in 5-d-old light-grown seedlings. 5XEBS:GUS seedlings were grown on 1/2 MS medium without (MS) or with 10 ppm ethylene (C2H4). (B) RT-qPCR analysis of the gene expression levels of miP1a and miP1b during the dark-to-light transition. WT seedlings were grown in the dark for 3 d and then exposed to light for the indicated periods of time. Mean ± SD; n = 3. (C and D) Immunoblot analysis of miP1a (C) and miP1b (D) protein abundance during the dark-to-light transition. The seedlings were grown in the dark for 3 d and then exposed to light for the indicated periods of time. Anti-Myc and anti-HSP antibodies were used for immunoblots. WT was used as a negative control. HSP proteins were utilized for loading controls.

Light Stimulates miP1a/b Expression to Transiently Elevate miP1a/b Protein Levels.

To investigate the manner in which miP1a/b are regulated by light, we measured the expression levels of miP1a/b during the dark-to-light transition. Seedlings were grown in the dark for 3 d and then exposed to white light irradiation for a period that was gradually lengthened. Notably, transcription of miP1a was strongly induced as much as 20-fold by 0.5 h light exposure (Fig. 1B). The expression level of miP1a was further increased when the irradiation period was prolonged to 1 h, but began to decrease after 2 h of light exposure (Fig. 1B). The regulation pattern of the miP1b gene was similar to that of miP1a with over 100-fold changes by light exposure for 0.5 h (Fig. 1B). These results indicate that miP1a/b expression is rapidly and dramatically induced by light irradiation.

The dynamics of endogenous miP1a/b proteins were monitored by assessing transgenic plants in which the miP1a or miP1b gene was driven by its native promoter (miP1a-p:miP1a-Myc/WT or miP1b-p:miP1b-Myc/WT). Consistent with the transcriptional regulatory pattern, miP1a protein was detected at an extremely low level in the dark (Fig. 1C). With 0.5 h of light exposure, the protein levels of miP1a were prominently induced and progressively increased as the light irradiation period was lengthened from 0.5 h to 4 h (Fig. 1C). Following prolonged exposure periods of 8 h or 12 h, miP1a protein abundance decreased gradually to an undetectable level (Fig. 1C). The dynamics of miP1b protein level regulation during light exposure were similar to those of miP1a, but miP1b protein began to accumulate after 1 h of light exposure and disappeared following 8 h of light irradiation (Fig. 1D). These data demonstrate that miP1a/b protein abundance is rapidly and transiently elevated during the dark-to-light transition.

miP1a/b Interact with PIFs and EIN3 Proteins.

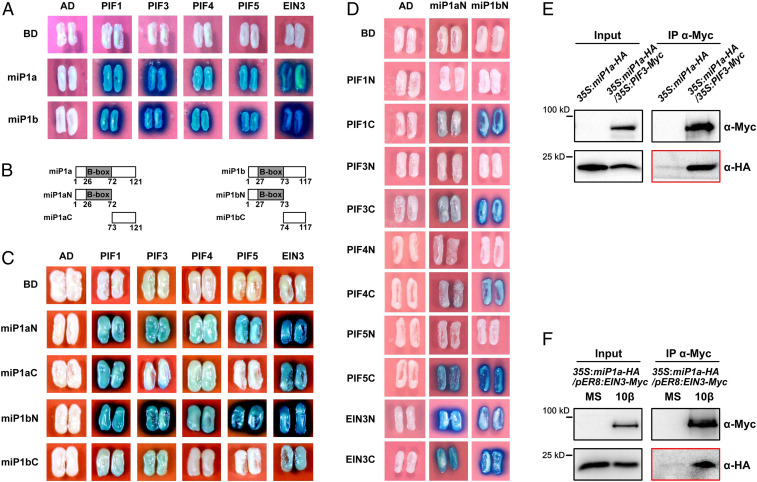

The similar tissue-specific expression patterns promoted us to investigate whether miP1a/b interact with PIFs and EIN3. Yeast two-hybrid assays showed that both miP1a and miP1b directly interacted with PIF1, PIF3, PIF4, PIF5, and EIN3 (Fig. 2A). Next, we separately tested the N terminus regions of miP1a/b (miP1aN or miP1bN), which contain the B-box domain, and their C terminus regions (miP1aC or miP1bC) (Fig. 2B). miP1aN and miP1bN strongly interacted with all of the tested PIFs and EIN3 (Fig. 2C), but the binding activities of the combinations of miP1aC/miP1bC with PIFs and EIN3 were generally much weaker (Fig. 2C). No binding activity was detected for miP1aC-PIF5, miP1bC-PIF4, or miP1bC-PIF5 (Fig. 2C). These results suggest that miP1a/b interact directly with PIFs and EIN3 primarily through the B-box domain. Moreover, we examined the interactions between miP1a/b and truncated versions of PIFs and EIN3. miP1aN and miP1bN interacted only with the C-terminal portions of four PIFs (Fig. 2D), which contain the bHLH domain responsible for protein–protein interaction and DNA binding. Both the N-terminal and C-terminal portions of EIN3 were targeted by miP1a and miP1b (Fig. 2D).

Fig. 2.

miP1a and miP1b physically interact with PIF1, PIF3, PIF4, PIF5, and EIN3. (A) Yeast two-hybrid assays for the interactions between miP1a and miP1b (miP1a/b) with PIFs and EIN3. Full-length miP1a or miP1b was fused with a LexA DNA binding domain (BD). Full-length PIF1, PIF3, PIF4, PIF5, or EIN3 was fused with an activation domain (AD). Empty vectors (BD or AD) were used as negative controls. (B) Schematic representations of the full-length and various truncated versions of miP1a (Left) and miP1b (Right) used in the yeast two-hybrid assays. The numbers represent the amino acid residues. (C and D) Yeast two-hybrid assays for the interactions between truncated versions of miP1a/b with PIFs and EIN3. The N or C terminus of miP1a/b was fused with a BD. The full-length and truncated PIFs or EIN3 was fused with an AD. Empty vectors (BD or AD) were used as negative controls. (E) Co-IP assays for the interactions between miP1a and PIF3 in Arabidopsis seedlings. Total protein was extracted from 3-d-old etiolated seedlings and immunoprecipitated by anti-Myc antibodies. Anti-Myc and anti-HA antibodies were used for immunoblots. (F) Co-IP assays for the interactions between miP1a and EIN3 in Arabidopsis seedlings. The seedlings were grown on 1/2 MS medium without (MS) or with (10β) 10 μM β-estradiol in the dark for 3 d. Anti-Myc antibodies were used for immunoprecipitation. Anti-Myc and anti-HA antibodies were used for immunoblots.

Next, the physical interactions of miP1a/b with PIFs and EIN3 were assessed in vivo. In the bimolecular fluorescence complementation (BiFC) assay, a miP1a or miP1b protein was fused to the split C terminus of YFP (miP1a-YFPc or miP1b-YFPc), and a PIF or EIN3 protein was fused to the split N terminus of YFP (PIFs-YFPn or EIN3-YFPn). Coexpressing miP1a-YFPc or miP1b-YFPc with PIF1-YFPn, PIF3-YFPn, PIF4-YFPn, PIF5-YFPn, or EIN3-YFPn reconstituted the YFP fluorescence signal in the nucleus of Nicotiana benthamiana epidermal cells (SI Appendix, Fig. S1). No YFP fluorescence signals were detected for the control combinations of GST fused with split YFP proteins (SI Appendix, Fig. S1). In the coimmunoprecipitation (co-IP) assay, immunoprecipitation of PIF3-Myc proteins using anti-Myc antibodies strongly enriched miP1a-HA proteins (Fig. 2E), indicating that PIF3 associates with miP1a in Arabidopsis seedlings. Similarly, we found that miP1a-HA proteins were also coimmunoprecipitated by the bait EIN3-Myc proteins (Fig. 2F). Taken together, these results demonstrate that miP1a/b directly interact with PIFs and EIN3.

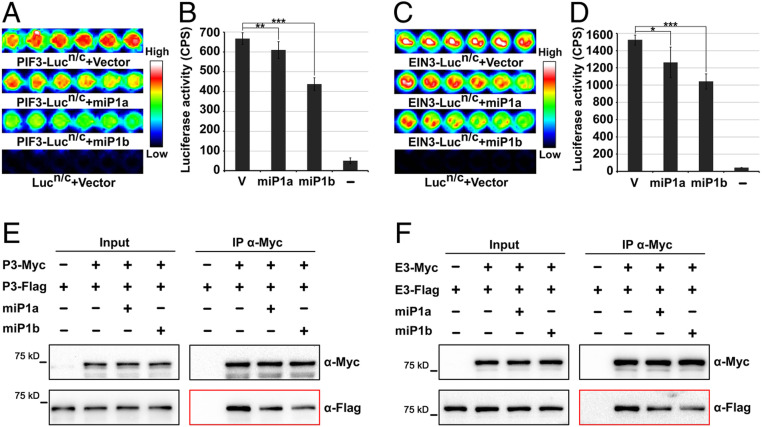

miP1a/b Inhibit the Self-Associations of PIF3 and EIN3.

It has been reported that microproteins disrupt complex formation to repress target proteins (26). Given the direct interactions between miP1a/b and PIFs/EIN3, we conducted experiments to determine whether miP1a/b affect the self-interactions of PIFs and EIN3. Firefly luciferase complementation imaging (LCI) assays were performed to evaluate the effects of miP1a/b on the self-interactions of PIF3 and EIN3. Full-length PIF3 or EIN3 was fused to the split N and C terminus of firefly luciferase (PIF3-Lucn/c and EIN3-Lucn/c). The reconstitution of luciferase activity by PIF3-Lucn and PIF3-Lucc in HEK293T cells indicated the self-interaction of PIF3 (Fig. 3 A and B). When we coexpressed miP1a or miP1b with PIF3-Lucn/c, the luciferase activities were significantly decreased, exhibiting ∼80% and 60% of PIF3 self-interaction for miP1a and miP1b, respectively (Fig. 3 A and B). Similarly, EIN3-Lucn and EIN3-Lucc reconstituted strong luciferase activity, and coexpressing miP1a or miP1b reduced the signals to 70% and 60% of their original intensity, respectively (Fig. 3 C and D). Immunoblot analysis demonstrated that the protein levels of PIF3-Lucn/c and EIN3-Lucn/c coexpression with an empty vector or miP1a/b were comparable among the samples (SI Appendix, Fig. S2). As a control, full-length firefly luciferase expressed in HEK293T cells displayed high luciferase luminescence that was not altered by coexpressing miP1a or miP1b (SI Appendix, Fig. S3). These results demonstrate that miP1a/b interfere with the self-interactions of PIF3 and EIN3.

Fig. 3.

miP1a and miP1b repress the self-interactions of PIF3 and EIN3. (A–D) Representative images (A and C) and quantitative analysis (B and D) of luciferase bioluminescence from LCI assays in HEK293T cells showing that miP1a/b repress the self-associations of PIF3 (A and B) and EIN3 (C and D). Full-length PIF3 or EIN3 was fused with the split N- or C-terminal fragments of luciferase (Lucn/c). pcDNA3.1-miP1a-HA, pcDNA3.1-miP1b-HA, or pcDNA3.1-HA empty vector (V) was cotransformed into HEK293T cells. Empty pcDNA3.1-Lucn/c and pcDNA3.1-HA vectors were used as negative controls (−). CPS, counts per second. Mean ± SD; n = 6. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, and ***P < 0.001. Student’s t test. (E and F) Co-IP assays determining the effects of miP1a/b on the self-interactions of PIF3 (E) and EIN3 (F). Full-length PIF3 or EIN3 was fused with Myc or Flag tag. Myc and Flag-tagged PIF3 (P3-Myc and P3-Flag) or EIN3 (E3-Myc and E3-Flag) proteins were coexpressed with pcDNA3.1-HA empty vector (−) or with pcDNA3.1-miP1a/b-HA (+) in HEK293T cells. Anti-Myc antibodies were used for immunoprecipitation. Anti-Myc and anti-Flag antibodies were used for immunoblots.

Additionally, the effects of miP1a/b on PIFs and EIN3 self-associations were assessed in co-IP assays. PIF3 proteins were fused with Myc or Flag tag, respectively, and cotransfected into HEK293T cells. The immunoblot results showed that PIF3-Flag proteins were coimmunoprecipitated by the bait PIF3-Myc proteins (Fig. 3E). When miP1a or miP1b proteins were coexpressed, the levels of coimmunoprecipitated PIF3-Flag proteins were largely reduced (Fig. 3E and SI Appendix, Fig. S4 A and B). The co-IP results also showed that EIN3 protein interacted with itself, and this self-interaction was significantly suppressed by miP1a/b (Fig. 3F and SI Appendix, Fig. S4 C and D). Collectively, we conclude that miP1a/b repress the self-associations of PIF3 and EIN3.

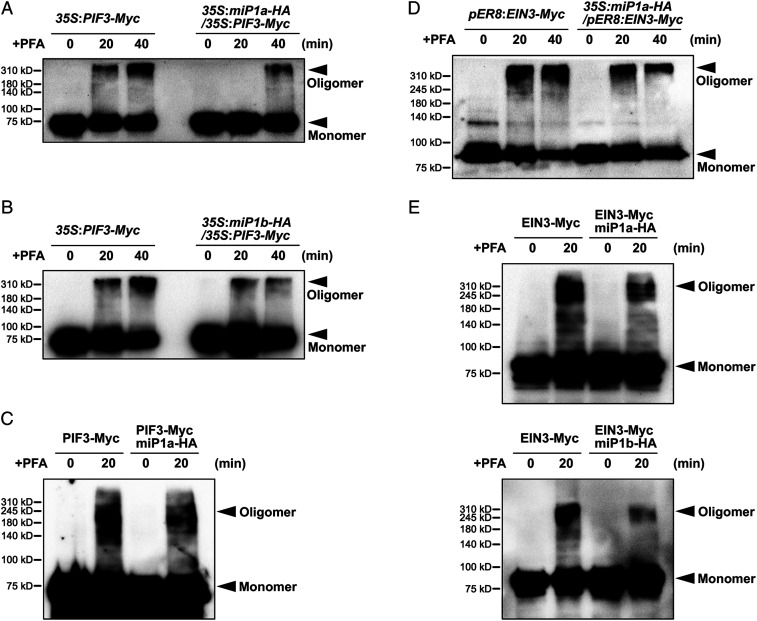

miP1a/b Disrupt the Assembly of PIF3 and EIN3 Oligomers.

Given the self-interactions of PIFs and EIN3, chemical fixative paraformaldehyde (PFA) crosslinking assays were performed to examine the oligomeric status of PIFs and EIN3. Without PFA treatment, the monomeric PIF3-Myc proteins of 35S:PIF3-Myc transgenic plants exhibited a molecular weight of 75 kDa (Fig. 4A). In the presence of PFA, the PIF3-Myc protein bands migrated at ∼310 kDa (Fig. 4A), suggesting that PIF3-Myc proteins are assembled in tetramers. When the PFA treatment period was prolonged from 20 min to 40 min, the intensity of the oligomeric band increased, while that of the monomeric band decreased (Fig. 4A). Next, miP1a-HA was introduced into 35S:PIF3-Myc to generate 35S:miP1a-HA/35S:PIF3-Myc transgenic plants. The intensity of the oligomeric bands of PIF3 proteins was strongly reduced by the presence of miP1a (Fig. 4A), indicating that miP1a inhibited oligomerization of PIF3 proteins in seedlings. Moreover, miP1b also strongly repressed assembly of PIF3 oligomers in vivo (Fig. 4B). We further examined the oligomeric formation of PIF3 in vitro. With PFA crosslinking, PIF3-Myc proteins exhibited prominent oligomer bands, which were largely reduced by adding miP1a proteins (Fig. 4C).

Fig. 4.

miP1a and miP1b disrupt the oligomerization of PIF3 and EIN3. (A and B) Chemical crosslinking assays show that PIF3 forms an oligomer in vivo, while miP1a (A) or miP1b (B) represses PIF3 oligomerization. Three-day-old etiolated seedlings were incubated with PFA for the indicated periods of time. Immunoblot analysis was performed using anti-Myc antibodies. (C) miP1a directly inhibits PIF3 oligomerization in vitro. PIF3-Myc protein mixed with or without miP1a-HA was treated with PFA for the indicated periods of time. Immunoblot analysis was performed using anti-Myc antibodies. (D) Chemical crosslinking assays show that EIN3 forms an oligomer in vivo, while miP1a represses EIN3 oligomerization. Three-day-old etiolated seedlings grown on 1/2 MS medium with 10 μM β-estradiol were incubated with PFA for the indicated periods of time. Immunoblot analysis was performed using anti-Myc antibodies. (E) miP1a/b directly inhibit EIN3 oligomerization in vitro. EIN3-Myc mixed with or without miP1a-HA (Top) or miP1b-HA (Bottom) was treated with PFA for the indicated periods of time. Immunoblot analysis was performed using anti-Myc antibodies.

To dissect the oligomeric status of EIN3, we used pER8:EIN3-Myc, in which EIN3-Myc expression was controlled by β-estradiol application, and overexpressed miP1a-HA in the homozygous pER8:EIN3-Myc background to generate 35S:miP1a-HA/pER8:EIN3-Myc transgenic plants. In pER8:EIN3-Myc transgenic plants with PFA crosslinking, EIN3-Myc proteins were present as oligomers, and the oligomeric bands exhibited a molecular weight over 310 kDa (Fig. 4D), suggesting that EIN3 was present as a tetramer in Arabidopsis seedlings. Remarkably, overexpression of miP1a dramatically reduced the abundance of EIN3 oligomers (Fig. 4D). Consistent with the inhibitory roles of miP1a on EIN3’s oligomerization in Arabidopsis, addition of miP1a/b decreased the oligomeric forms of EIN3 in vitro (Fig. 4E), demonstrating that miP1a/b directly inhibited the oligomerization of EIN3. Notably, PIF3-Myc exhibited multiple oligomeric bands between 140 kDa and 310 kDa (Fig. 4C), and the oligomeric forms of EIN3-Myc were enriched around 245 kDa and 310 kDa in vitro (Fig. 4E). It is suggested that PIF3 and EIN3 prefer to form higher-order oligomers in plants, which might require other cofactors. Together, these results reveal that PIF3 and EIN3 proteins in seedlings are present as tetramers, and their oligomerization can be disrupted directly by miP1a/b.

miP1a/b Sequester PIF3 and EIN3 Binding to Their Target Genes.

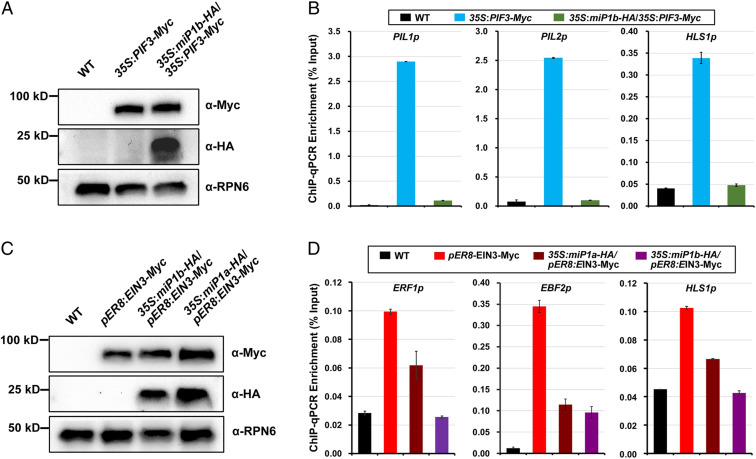

Given the direct interactions between miP1a/b and PIFs/EIN3, as well as repression of PIF3 and EIN3 oligomerization by miP1a/b, we were intrigued as to whether miP1a/b affect the DNA binding ability of PIF3 or EIN3. To address this question, we performed chromatin immunoprecipitation-qPCR (ChIP-qPCR) assays to evaluate the DNA binding capacity of PIF3 in vivo. We first examined the protein levels of PIF3-Myc in 35S:PIF3-Myc and 35S:miP1b-HA/35S:PIF3-Myc seedlings, which showed similar levels of PIF3-Myc proteins (Fig. 5A). In the ChIP-qPCR assay with precipitation by anti-Myc antibodies, we found that the promoter regions of PIL1, PIL2, and HLS1 were strongly enriched in 35S:PIF3-Myc seedlings, but not in WT control seedlings (Fig. 5B). However, in 35S:miP1b-HA/35S:PIF3-Myc seedlings with miP1b overexpression, enrichment of the promoter regions of PIL1, PIL2, and HLS1 was largely reduced (Fig. 5B), suggesting that miP1b compromises the association of PIF3 with its target genes.

Fig. 5.

miP1a and miP1b sequester PIF3 and EIN3 binding to their target genes. (A) Immunoblot analysis of PIF3-Myc and miP1b-HA protein abundance in 3-d-old etiolated seedlings. WT was used as a negative control and the RPN6 protein was utilized as a loading control. (B) ChIP-qPCR assay showing enrichment of the promoter fragments of PIL1, PIL2, and HLS1 bound by PIF3 in 3-d-old etiolated seedlings. Anti-Myc antibodies were used for precipitation. WT seedlings with anti-Myc antibodies were used as negative controls. Mean ± SD; n = 3. (C) Immunoblot analysis of EIN3-Myc, miP1a-HA, and miP1b-HA protein abundance. Seedlings were grown on 1/2 MS medium with 10 μM β-estradiol in the dark for 3 d. WT was used as a negative control and the RPN6 protein was utilized as a loading control. (D) ChIP-qPCR assay showing enrichment of the promoter fragments of ERF1, EBF2, and HLS1 bound by EIN3 in seedlings. Seedlings were grown on 1/2 MS medium with 10 μM β-estradiol in the dark for 3 d. Anti-Myc antibodies were used for precipitation. WT seedlings with anti-Myc antibodies were used as negative controls. Mean ± SD; n = 3.

Moreover, the protein levels of EIN3 were similar in the pER8:EIN3-Myc, 35S:miP1a-HA/pER8:EIN3-Myc, and 35S:miP1b-HA/pER8:EIN3-Myc seedlings (Fig. 5C). The ChIP-qPCR results showed that EIN3 proteins were associated with the promoter regions of ERF1, EBF2, and HLS1 in pER8:EIN3-Myc seedlings in comparison with those of WT control seedlings (Fig. 5D). miP1a and miP1b dramatically repressed the binding of EIN3 to the DNA of its target genes, with notably reduced enrichment of the ERF1, EBF2, and HLS1 promoters in 35S:miP1a-HA/pER8:EIN3-Myc and 35S:miP1b-HA/pER8:EIN3-Myc seedlings (Fig. 5D). Therefore, these data indicate that miP1a/b suppress the DNA binding capacities of PIF3 and EIN3.

miP1a/b Repress the Transcriptional Activities of PIF3 and EIN3.

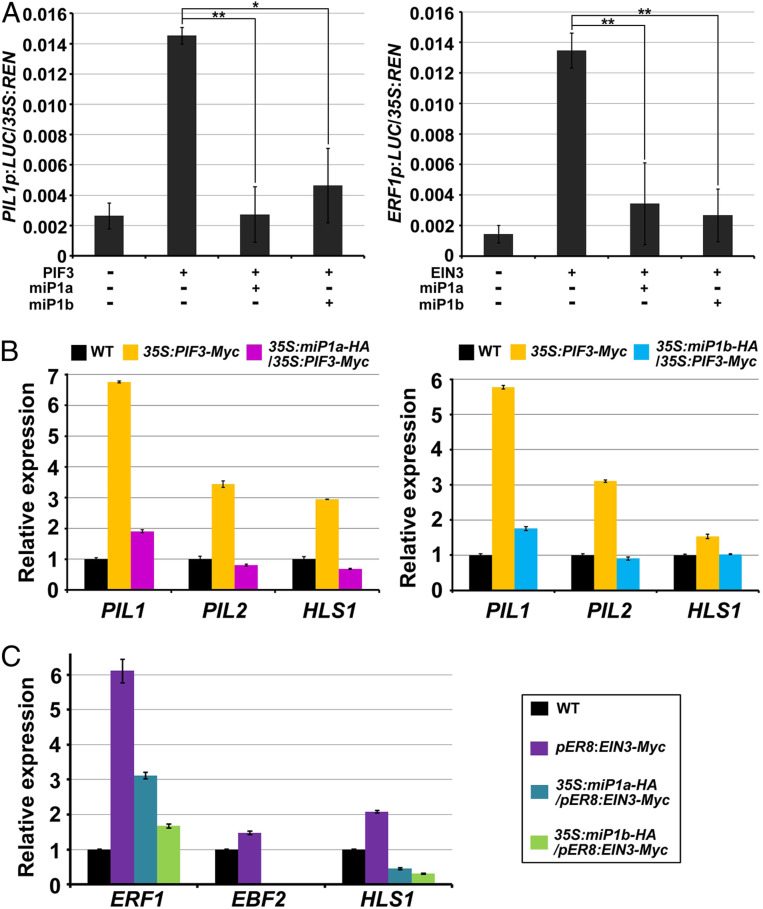

Next, a dual-LUC assay was performed in N. benthamiana leaves to assess the effects of miP1a and miP1b on the transcriptional activities of PIFs and EIN3. We utilized a firefly luciferase (LUC) gene driven by the PIL1 or ERF1 promoter to indicate the transcriptional activity of PIF3 or EIN3, respectively. PIF3 increased PIL1 gene expression by approximately sixfold in comparison with the empty vector control (Fig. 6A). The expression level of PIL1 was largely reduced by coexpression of miP1a or miP1b (Fig. 6A). Similarly, activation of ERF1 gene expression by EIN3 was dramatically repressed by contransformation of N. benthamiana leaves with miP1a or miP1b protein (Fig. 6A). In addition, we found that the expression of RBCS1A, an internal control gene, was not regulated by PIF3 or EIN3 alone or coinfiltration of miP1a/b (SI Appendix, Fig. S5A). These results indicate that miP1a/b act as repressors of the transcriptional activity of PIF3 and EIN3.

Fig. 6.

miP1a and miP1b repress the transcriptional activity of PIF3 and EIN3. (A) Transient dual LUC reporter gene assays for assessing the transcriptional activity of PIF3 and EIN3 in N. benthamiana leaf cells. The leaves were transfected with the firefly luciferase (LUC) reporter PIL1p:LUC construct cotransformed with PIF3 + vector, PIF3 + miP1a, or PIF3 + miP1b (Left), or the leaves were transfected with the reporter ERF1p:LUC construct cotransformed with EIN3 + vector, EIN3 + miP1a, or EIN3 + miP1b (Right). LUC activity was normalized to renilla luciferase (35S:REN). Mean ± SD; n = 5. Empty vectors were used as negative controls (−). *P < 0.05, and **P < 0.01. Student’s t test. (B and C) RT-qPCR results showing the expression levels of the indicated genes in 3-d-old etiolated seedlings grown on 1/2 MS medium (B) or 1/2 MS medium with 10 μM β-estradiol (C). Mean ± SD; n = 3.

We further examined whether the transcriptional activities of PIF3 and EIN3 in Arabidopsis were affected by miP1a/b. RT-qPCR assays revealed that the expression levels of PIF3-targeted genes PIL1, PIL2, and HLS1 were up-regulated in 35S:PIF3-Myc seedlings, but these levels were markedly decreased in 35S:miP1a-HA/35S:PIF3-Myc or 35S:miP1b-HA/35S:PIF3-Myc seedlings to a lower level comparable to that of WT seedlings (Fig. 6B). These data suggest that miP1a/b inhibit the transcriptional activation by PIF3 of its target genes. Moreover, we showed that EIN3 activates gene expression of target genes ERF1, EBF2, and HLS1 in pER8:EIN3-Myc seedlings with β-estradiol treatment (Fig. 6C). However, overexpression of miP1a or miP1b in pER8:EIN3-Myc seedlings suppressed EIN3-activated gene expression of ERF1, EBF2, and HLS1 (Fig. 6C). As a control, the expression levels of RBCS1A were similar across these samples (SI Appendix, Fig. S5B). Therefore, we conclude that miP1a/b repress the transcriptional activity of PIF3 and EIN3 by inhibiting binding to their target genes.

miP1a/b Promote Seedling Deetiolation in the Dark-to-Light Transition.

Given the inhibitory roles of miP1a/b on PIFs and EIN3, we next explored the roles of miP1a/b in regulating deetiolation. Dark-grown WT seedlings exhibited a folded apical hook and tightly closed small cotyledons. With light exposure, the apical hooks and cotyledons of etiolated WT seedlings gradually opened (SI Appendix, Fig. S6 A and B), and the area of cotyledons gradually increased with prolonged light irradiation (SI Appendix, Fig. S6 C and D). Overexpression of miP1a or miP1b in WT seedlings (miP1a-ox and miP1b-ox) caused notably accelerated apical hook unfolding and cotyledon opening during the dark-to-light transition (SI Appendix, Fig. S6 A and B). The cotyledons of miP1a-ox and miP1b-ox seedlings were much larger than those of WT seedlings even in the dark, and they rapidly expanded along with light irradiation (SI Appendix, Fig. S6 C and D). We further examined the phenotypes of miP1a miP1b double mutant (32). Dark-grown miP1a miP1b seedlings displayed apical hook formation and cotyledon development similar to those of WT seedlings (SI Appendix, Fig. S6). However, light-induced opening of apical hooks and cotyledons in miP1a miP1b seedlings was notably delayed (SI Appendix, Fig. S6 A and B). Moreover, expansion of miP1a miP1b cotyledons was largely insensitive to light irradiation, and these cotyledons exhibited no obvious increase in size even after 4 h of light exposure (SI Appendix, Fig. S6 C and D). Thus, we conclude that miP1a/b play critical roles in the promotion of apical hook unfolding, cotyledon opening, and expansion during the dark-to-light transition.

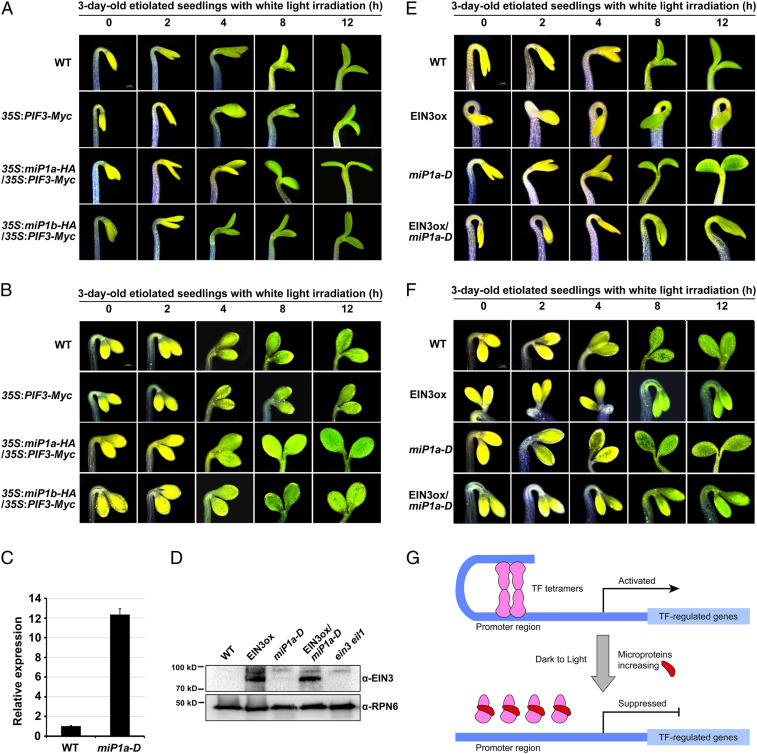

miP1a/b Relieve the Repression of PIF3/EIN3 on Photomorphogenic Development.

Next, we investigated the effects of miP1a/b on the physiological functions of PIFs and EIN3. When the etiolated seedlings were exposed to light irradiation, 35S:PIF3-Myc seedlings exhibited delayed apical hook and cotyledon opening, with less expanded cotyledons (Fig. 7 A and B and SI Appendix, Figs. S7 and S8). 35S:miP1a-HA/35S:PIF3-Myc and 35S:miP1b-HA/35S:PIF3-Myc seedlings overexpressing miP1a or miP1b, respectively, showed notably accelerated apical hook and cotyledon opening (Fig. 7A and SI Appendix, Fig. S7), as well as full rescue of the poorly expanded cotyledons of 35S:PIF3-Myc seedlings under light irradiation (Fig. 7B and SI Appendix, Fig. S8). These results indicated that miP1a/b repress the inhibitory effects of PIF3 on deetiolation.

Fig. 7.

miP1a and miP1b predominantly suppress the function of PIF3 and EIN3 to promote photomorphogenic development. (A and B) Representative images of light-induced apical hook unfolding, cotyledon opening (A) and cotyledon expansion (B) of etiolated seedlings. Seedlings were grown in the dark for 3 d and then exposed to light for the indicated periods of time. (Scale bar: 1 mm.) (C) RT-qPCR results showing the gene expression levels of miP1a in 3-d-old etiolated seedlings. Mean ± SD; n = 3. (D) Immunoblots for endogenous EIN3 protein in 3-d-old etiolated seedlings. Anti-EIN3 and anti-RPN6 antibodies were used for immunoblots. ein3 eil1 was used as a negative control. RPN6 was used as a loading control. (E and F) Representative images of light-induced apical hook unfolding, cotyledon opening (E) and cotyledon expansion (F) of etiolated seedlings. Seedlings were grown in the dark for 3 d and then exposed to light for the indicated periods of time. (Scale bar: 1 mm.) (G) A proposed model depicting microprotein-directed disassembly of key transcription factor oligomers during the dark-to-light transition. In the dark, transcription factors (TF, PIFs, and EIN3/EIL1) assemble active tetramers, and subsequently associate with and regulate downstream genes to repress light responses. Upon light exposure, two microproteins, miP1a and miP1b, are robustly elevated. miP1a/b directly interact with target TFs, disrupt TF tetramers, and sequester their DNA binding capacity, promptly suppressing their function to initiate photomorphogenic development.

We also obtained a T-DNA insertion line, in which the T-DNA was inserted into the 5′-UTR of miP1a. RT-qPCR assays showed that expression of miP1a was constitutively up-regulated in the miP1a mutant (Fig. 7C), suggesting that it was a gain-of-function mutant, which was thus designated miP1a-D. Next, crossing was used to generate the EIN3ox/miP1a-D line, in which EIN3 and miP1a were overexpressed. The immunoblot analysis with anti-EIN3 antibodies showed that the endogenous EIN3 proteins in EIN3ox and EIN3ox/miP1a-D seedlings were similar (Fig. 7D), indicating that overexpressing miP1a did not affect EIN3 protein abundance. Dark-grown EIN3ox seedlings displayed exaggerated apical hook curvature, which was largely opened in EIN3ox/miP1a-D seedlings (Fig. 7E and SI Appendix, Fig. S9), indicating that miP1a represses the function of EIN3 in maintaining hook formation. Consistently, light-induced apical hook unfolding was accelerated in EIN3ox/miP1a-D seedlings in comparison with EIN3ox seedlings (Fig. 7E and SI Appendix, Fig. S9). The cotyledons of EIN3ox/miP1a-D seedlings remained closed after 12 h of light exposure (Fig. 7E and SI Appendix, Fig. S9). When the period of light irradiation was prolonged to 3 d, the cotyledons of WT and miP1a-D seedlings were fully opened, but the cotyledons of EIN3ox seedlings were partially opened, with an angle of ∼120° (SI Appendix, Fig. S11A). miP1a-D rescued the repressed cotyledon opening of EIN3ox to display fully opened cotyledons in EIN3ox/miP1a-D (SI Appendix, Fig. S11A). Moreover, EIN3ox exhibited extremely small cotyledons, while miP1a-D mostly rescued the inhibited cotyledon expansion of EIN3ox to a level comparable to that of WT (Fig. 7F and SI Appendix, Figs. S10 and S11B). Based on these findings, we propose a model in which light stimulates miP1a/b to promote photomorphogenic development by direct allosteric inactivation of PIF3 and EIN3 (Fig. 7G).

Discussion

Many proteins function in high-order complexes formed by protein–protein interactions. This operation mode enhances the biological activity and specificity of proteins, while the formation and disruption of complexes provides functional regulation (36–38). PIFs belong to the bHLH transcription factor superfamily (39). Similar to other bHLH proteins in mammals and plants (40), PIF proteins interact with themselves and among each other (41). Moreover, recombinant N-terminal truncation of EIN3 (82 to 352 amino acids [aa]) acts as a homodimer, and full-length EIN3 likely forms high-order complexes to bind DNA in vitro (42, 43). However, the action mode of PIFs and EIN3 in vivo remains undefined. In this study, we found that PIFs and EIN3 assemble into homotetramers to function in plants. miP1a/b directly inhibit the self-associations of PIFs and EIN3 to repress their oligomerization and DNA binding ability. Notably, a recent study unraveling the crystal structure of bHLH transcription factor MYC2 revealed that MYC2 exists as a tetramer, and tetrameric MYC2 possesses greatly enhanced stability and DNA binding capacity (44). A tetramer can bind to two DNA sites to increase the binding capacity and stability, as well as provide more opportunities for cofactor recruitment to initiate transcription. These findings indicate that oligomeric status is important for transcription factor function and define the critical roles of miPs in posttranslational regulation.

It has been assumed that photomorphogenesis is the default pathway for plant development (4). In the dark, photomorphogenesis is repressed by multiple negative regulators to allow skotomorphogenesis to occur. Deactivation of PIFs and EIN3/EIL1, which act as master transcription factors in repression of photomorphogenesis, triggers the switch from skotomorphogenesis to photomorphogenesis upon exposure to light (5, 19, 20). Previous studies have established that light induces rapid degradation of PIFs and EIN3/EIL1 proteins to initiate photomorphogenesis (16, 39). Here, we propose a miP1a/b-mediated derepression module that promotes photomorphogenesis during the dark-to-light transition. It is achieved through light-triggered rapid elevation of miP1a/b, which directly repress the transcriptional activity of PIFs and EIN3 by inhibiting their oligomerization and DNA binding capacity. As important integrators of multiple pathways, PIFs and EIN3 mediate a wide range of responses to various external or internal signals (2, 3, 45). This miP-mediated module enables direct repression of the activity of PIFs and EIN3 without affecting their protein abundance. Therefore, photomorphogenic development can be timely initiated with retaining a low level of stable miP1a/b-repressed PIFs and EIN3 proteins. In response to environmental or physiological signals, the miPs can disengage and allow transcription factors to promptly assemble active oligomers for gene expression control.

Ever since the first identified miP INHIBITOR OF DNA BINDING (Id) (46), studies of miPs have revealed that these proteins are distributed widely across species and regulate a variety of biological processes. For example, members of the Id family of proteins inhibit HLH transcription factors’ dimerization and DNA binding during immune system development, neural determination, and tumorigenesis (47–49). Here we show that miP1a/b promote plant photomorphogenesis by directly repressing the oligomerization of key transcription factors PIFs and EIN3, suggesting a recurring theme in the evolution of miPs. Recently, miP1a/b were shown to promote hypocotyl growth in continuous visible light (32), while miP1a enhances the inhibitory effect of ultraviolet-B (UV-B) on hypocotyl elongation and tolerance to high doses of UV-B radiation (33). It is tempting to speculate whether miP1a/b adopt similar mechanisms to regulate target transcription factors in these processes. Intriguingly, miP1a/b have been previously shown to function in adult plant leaves as a bridge that recruits the transcriptional repressor TOPLESS to CO protein to repress flowering (29), suggesting that miP1a/b employ multiple inhibitory mechanisms in different developmental stages. In addition, miP1a/b-type proteins originated in the Pentapetalae family where the monocotyledonous and dicotyledonous lineages diverge (29). Buried monocotyledonous seedlings usually adopt a sharp coleoptile to penetrate the soil, whereas dicotyledonous seedlings maintain small and closed cotyledons and form an apical hook to facilitate emergence (50, 51). Thus, miP1a/b may have contributed to the successful terrestrialization of dicotyledonous plants by improving their survival of soil emergence.

Materials and Methods

Plant Materials and Growth Conditions.

The WT Arabidopsis thaliana ecotype used in this study is Columbia-0 background. Detailed information regarding PIFs-p:GUS (35), 5XEBS:GUS (52, 53), EIN3ox (54), pER8:EIN3-Myc/ein3 eil1 ebf1 ebf2 (7), 35S:PIF3-Myc (55), and miP1a miP1b (32) has been reported previously. The T-DNA insertion mutant miP1a-D (GK-288G08) was obtained from the Nottingham Arabidopsis Stock Centre (NASC). The full-length coding sequences of miP1a and miP1b genes were cloned into pENTR4 vector (Invitrogen) to create pENTR4-miP1a and pENTR4-miP1b constructs. The miP1a and miP1b promoters, consisting of the regions 2,000 bp and 1,883 bp upstream from the predicted translational initiation site of miP1a and miP1b, were used to create pENTR4-miP1a-p and pENTR4-miP1b-p constructs. The miP1a and miP1b promoters fused to miP1a and miP1b coding sequences were used to create pENTR4-miP1a-p-miP1a and pENTR4-miP1b-p-miP1b constructs. Primers used for plasmid construction are listed in SI Appendix, Table S1. The pENTR4 constructs containing PCR fragments were recombined into the pGWBs binary vectors (56). pENTR4-miP1a and pENTR4-miP1b were recombined into pGWB614 to generate 35S:miP1a-HA and 35S:miP1b-HA constructs. pENTR4-miP1a-p and pENTR4-miP1b-p were recombined into pGW433 to generated miP1a-p:GUS and miP1b-p:GUS constructs. pENTR4-miP1a-p-miP1a and pENTR4-miP1b-p-miP1b were recombined into pGWB616 to generate miP1a-p:miP1a-Myc and miP1b-p:miP1b-Myc constructs. Agrobacterium tumefaciens strain GV3101 carrying these constructs was transformed into the indicated WT, pER8:EIN3-Myc/ein3 eil1 ebf1 ebf2 or 35S:PIF3-Myc Arabidopsis plants by the floral dip method. The seeds were surface sterilized using 75% ethanol containing 0.5% Triton X-100. The sterilized seeds were planted on half-strength Murashige and Skoog (1/2 MS) medium (2.2 g/L MS salts, 5 g/L sucrose, and 8 g/L agar, pH = 5.7) unless otherwise specified. For chemical treatment, 10 μM β-estradiol was added to the 1/2 MS medium. After stratification at 4 °C in the dark for 3 d, the seeds were irradiated with white light for 6 h to induce germination and then incubated at 22 °C in darkness or white light (10 μmol m−2 s−1).

GUS Staining.

For GUS staining, 5-d-old white-light-grown seedlings were submerged in a GUS staining solution (0.1 M sodium phosphate buffer, 0.5 mM K4Fe(CN)6, 1 mM K3Fe(CN)6, 1% Triton X-100, 1 mM ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (EDTA), and 1 mg/mL X-gluc) and incubated overnight in the dark at 37 °C. A series of gradient ethanol solutions (100%, 90%, and 75%) was used for destaining and representative photos were presented.

RNA Extraction and RT-qPCR.

Three-day-old etiolated seedlings with or without indicated regimen of light exposure were harvested in liquid nitrogen in a dark room under a dim green safe light and ground to powder. The Spectrum Plant Total RNA Kit (Sigma) was used to extract total RNA. Spectrophotometry and gel electrophoretic analysis were performed to assess RNA quality. One microgram of total RNA was used to synthesize first-strand cDNA using the ReverTra Ace qPCR RT Master Mix (Toyobo). RT-qPCR was performed using SYBR Green qPCR Master Mix (TaKaRa) with an ABI Fast 7500 Real-Time system. All gene expression values were normalized with respect to two reference genes, SAND (AT2G28390) and PP2A (AT1G13320) (57, 58). The relative expression levels normalized to SAND were consistent with those normalized to PP2A. Three independent biological replicates were performed and the representative results normalized to PP2A were presented.

HEK293T Cell Culture and Transfection.

Dulbecco's modified Eagle’s medium (DMEM) supplemented with 10% (vol/vol) fetal bovine serum, 100 IU penicillin and 100 mg/L streptomycin was used for human embryonic kidney (HEK)293T cell culture. Cells were grown at 37 °C overnight in a 5% (vol/vol) CO2 incubator. Cell transfection was performed by using a calcium phosphate method as previously described (59). Briefly, CaCl2–DNA precipitates containing 2 μg of plasmid DNA were added into 2 × Hepes-buffered saline (50 mM Hepes, pH = 7.5, 1.5 mM Na2HPO4, 250 mM NaCl, 10 mM KCl, 12 mM dextrose, adjust final pH to 7.05) and then were incubated at room temperature for 5 min to make a transfection mixture. After adding the transfection mixture, the cell culture was gently rotated for 40 min and subjected to culture for 36 to 48 h before harvesting.

Co-IP Assays.

For co-IP assays in mammalian cells, full-length coding sequences of miP1a, miP1b, PIF3, or EIN3 were cloned into the indicated tagged pcDNA3.1 vectors (Invitrogen), and the constructs were transfected in HEK293T cells as above described. Proteins were added into binding buffer (20 mM Tris⋅HCl, pH = 7.5, 150 mM NaCl and 1 mM EDTA) and gently rotated with anti-Myc antibodies (Sigma-Aldrich, M4439) for 1 h, after which they were incubated with protein G agarose beads (Millipore) for 1 h at 4 °C. The beads were washed four times with wash buffer (50 mM Tris⋅HCl, 0.5% Triton X-100, 1 mM EDTA and 10% glycerol) before collection. Anti-Myc (Sigma-Aldrich; M4439, 1:2,000 dilution) and anti-Flag (Invitrogen; FG4R, 1:1,000 dilution) antibodies were used for immunoblot analysis.

For co-IP assays in Arabidopsis seedlings, total proteins were extracted in extraction buffer (50 mM Tris⋅HCl, pH = 7.5, 150 mM NaCl, 10 mM MgCl2, 0.5 mM EDTA, 10% glycerol, and protease inhibitor mixture). The protein extraction solution was incubated with anti-Myc antibodies (Sigma-Aldrich, M4439) for 1 h, after which it was incubated with protein G agarose beads (Millipore) for 1 h at 4 °C. The beads were washed with washing buffer (50 mM Tris⋅HCl, pH = 7.5, 200 mM NaCl, 10 mM MgCl2, and 0.5 mM EDTA) four times. The washed beads were collected by centrifugation for immunoblot analysis using anti-Myc (Sigma-Aldrich; M4439, 1:2,000 dilution) and anti-HA (Cell Signaling; C29F4, 1:1,000 dilution) antibodies.

Immunoblot Analysis.

The seedlings were grown in the dark for 3 d with or without white light irradiation for the indicated periods. For chemical crosslinking in Arabidopsis, the seedlings were harvested and submerged in 0.5% PFA (Sigma-Aldrich) solution for the indicated periods. Total proteins were extracted in extraction buffer (50 mM Tris⋅HCl, pH = 7.5, 10 mM MgCl2, 150 mM NaCl, and 1 mM phenylmethanesulfonyl fluoride [PMSF]). For in vitro chemical crosslinking, total proteins were extracted in lysis buffer (20 mM Hepes, pH = 7.4, 100 mM NaCl, and protease inhibitor mixture) and were mixed with PFA in a final concentration of 0.2% for 20 min. The protein solution was mixed in sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS) loading buffer and separated on SDS–polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis gels. Anti-Myc (Sigma-Aldrich; M4439, 1:2,000 dilution), anti-HSP90 (Abmart, 51099–31-PU, 1:4,000 dilution), anti-HA (Cell Signaling; C29F4, 1:1,000 dilution), anti-Luc (Invitrogen; CS17, 1:2,000 dilution), anti–β-Actin (Sigma-Aldrich; A2228, 1:5,000 dilution), anti-RPN6 (Abmart, X-Q9LP45-N, 1:5,000 dilution), anti-PIF3 (1:1,000 dilution) (18), and anti-EIN3 (1:500 dilution) (60) antibodies were used for the immunoblotting analysis.

Yeast Two-Hybrid Assay.

The full-length and truncated variants of PIFs and EIN3 (PIF1N [1 to 150 aa], PIF1C [151 to 478 aa], PIF3N [1 to 192 aa], PIF3C [184 to 523 aa], PIF4N [1 to 208 aa], PIF4C [209 to 429 aa], PIF5N [1 to 200 aa], PIF5C [201 to 443 aa], EIN3N [1 to 341 aa], EIN3C [342 to 628 aa]) were cloned into pB42AD vector (Clontech). The full-length and truncated variants of miP1a and miP1b (miP1aN [1 to 72 aa], miP1aC [73 to 121 aa], miP1bN [1 to 73 aa], miP1bC [74 to 117 aa]) were cloned into pLexA vector (Clontech) to construct the BD-fusion plasmids. Each plasmid combination was transformed into yeast strain EGY48 that carries a pLacZi reporter plasmid as described in the Yeast Protocols Handbook (Clontech). The transformants were selected on SD/−Trp −Ura −His dropout medium at 30 °C for 2 d. Protein–protein interaction was further detected using SD/ −Trp −Ura −His dropout medium supplied with 20 mg/mL X-gal (5-bromo-4-chloro-3-indolyl β-D-galactopyranoside) for blue color development.

BiFC Assay.

The full-length coding sequences of PIF1, PIF3, PIF4, PIF5, EIN3, miP1a, miP1b, and GST (as a negative control) were cloned into pENTR4 vector (Invitrogen) and the entry constructs were recombinant into the pGWnY/pGWcY binary vectors containing the N/C terminus of YFP (61). A. tumefaciens strain GV3101, carrying each of the indicated plasmid pairs, was infiltrated into N. benthamiana leaves. The two constructs in each pair were mixed equally. After 2 d, the YFP fluorescence signals were observed and imaged under a Carl Zeiss confocal laser scanning microscope (LSM510 Meta) with an excitation wavelength of 514 nm.

Firefly LCI Assay.

The full-length coding sequences of firefly luciferase (Luc), miP1a, miP1b, PIF3, or EIN3 were fused separately into the indicated tagged pcDNA3.1 vectors (Invitrogen), and the constructs were transfected in HEK293T cells as above described. For each construct combination, six replicates were performed using individual pools of transfected cells. Cells were dissociated with trypsin (Gibco) and collected by soft centrifugation. The collected cells were washed and then resuspended with PBS. A total of 40 μL of cell suspension was added into a well of 96-well plate and D-Luciferin potassium salt solution (Yeasen Biotech) was added to each well at a final concentration of 1 mM. After a 5-min incubation in darkness at room temperature, luciferase bioluminescence images and signals were obtained by using a Berthold Technologies Multimode Reader LB942, and bioluminescence intensity was quantified by IndiGo software.

ChIP-qPCR Assay.

ChIP was performed in a dark room with dim green light as previously described (62–64). Two grams of 3-d-old etiolated seedlings for each sample was crosslinked in 1% formaldehyde under vacuum for 30 min and terminated by adding glycine to a final concentration of 0.125 M. The harvested seedlings were ground to powder in liquid nitrogen and suspended in extraction buffer I (10 mM Tris⋅HCl, pH = 8, 10 mM MgCl2, 0.4 M sucrose, 5 mM β-mercaptoethanol, 1 mM PMSF, and protease inhibitor mixture). The suspension was centrifuged at 4,000 rpm at 4 °C for 20 min. The pellet was resuspended in extraction buffer II (10 mM Tris⋅HCl, pH = 8, 10 mM MgCl2, 1% Triton X-100, 0.25 M sucrose, 5 mM β-mercaptoethanol, 1 mM PMSF, and protease inhibitor mixture) and centrifuged at 14,000 rpm at 4 °C for 10 min. The pellet was resuspended in extraction buffer III (10 mM Tris⋅HCl, pH = 8, 2 mM MgCl2, 1.7 M sucrose, 0.15% Triton X-100, 5 mM β-mercaptoethanol, 1 mM PMSF, and protease inhibitor mixture) and loaded onto extraction buffer III, and then was centrifuged at 14,000 rpm at 4 °C for 1 h. The pellet was resuspended in nuclear lysis buffer (50 mM Tris⋅HCl, pH = 8.0, 10 mM EDTA, 1% SDS, and protease inhibitor mixture), sonicated with a Branson sonifier and centrifuged at 14,000 rpm at 4 °C for 10 min. The supernatant was diluted with ChIP dilution buffer (16.7 mM Tris⋅HCl, pH = 8.0, 1.1% Triton X-100, 1.2 mM EDTA and 167 mM NaCl). The immunoprecipitation was performed by using anti-Myc antibodies (M4439; Sigma-Aldrich) overnight at 4 °C and protein G agarose beads (Millipore) for 2 h at 4 °C to pull down protein–DNA complexes. The immunocomplex was successively washed by low-salt wash buffer (150 mM NaCl, 1% Triton X-100, 0.1% SDS, 2 mM EDTA, and 20 mM Tris⋅HCl, pH = 8.0), high-salt wash buffer (500 mM NaCl, 1% Triton X-100, 0.1% SDS, 2 mM EDTA, and 20 mM Tris⋅HCl, pH = 8.0), LiCl wash buffer (0.25 M LiCl, 1% sodium deoxycholate, 1% Nonidet P-40, 1 mM EDTA, and 10 mM Tris⋅HCl, pH = 8.0), and TE buffer (10 mM Tris⋅HCl, pH 8.0, and 1 mM EDTA) and then was eluted with elution buffer (1% SDS and 0.1 M NaHCO3). The eluates and input control were reverse crosslinked with a final concentration of 200 mM NaCl at 65 °C overnight. After treating with RNase A and proteinase K, DNA was extracted with phenol-chloroform and then ethanol precipitation. The DNA pellet was resuspended in sterilized water for qPCR. qPCR was performed using SYBR Green qPCR Master Mix (TaKaRa) with an ABI Fast 7500 Real-Time system to amplify specific DNA fragments. Wild-type seedlings side by side were used as the negative control. The percentage of IP DNA to its corresponding input DNA was represented as enrichment for each target.

Dual-Luciferase Reporter Assay.

The ERF1, PIL1, and RBCS1A promoters, consisting of the regions 2,000 bp, 1,813 bp, and 2,000 bp upstream from the predicted translational initiation site of ERF1, PIL1, and RBCS1A, were cloned into pGreenII-0800-LUC vector (65), respectively. The full-length coding sequences of PIF3, EIN3, miP1a, and miP1b genes were cloned into pENTR4 vector (Invitrogen) and then were recombined into the binary vector pGW617 to make the effector constructs. A. tumefaciens strain GV3101, carrying each of the indicated plasmid pairs, was infiltrated into N. benthamiana leaves. The indicated constructs in each combination were mixed equally. After 2 d, the activity levels of firefly luciferase (LUC) and renilla luciferase (REN) were measured using the Dual-Luciferase Reporter Assay System kit (Promega) with a GloMax 20/20 luminometer (Promega).

Phenotype Analysis.

The seedlings were grown in the dark for 3 d and then transferred to white light irradiation (10 μmol m−2 s−1) for the indicated periods. The angle between two cotyledons was recorded as the cotyledon opening angle. The apical hook angle was determined by 180° minus the angle between the tangential apical part and the hypocotyl (66). Measurement was performed by ImageJ software (https://imagej.nih.gov/ij/). At least 100 seedlings per sample were measured for cotyledon opening or apical hook angle, and at least 14 cotyledons per sample were measured for cotyledon area. The representative images taken by using Leica Microsystem M205FA were presented.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We greatly appreciate Peter Quail for the PIFs-p:GUS seeds, Joseph Ecker for the 5XEBS:GUS and EIN3ox seeds, Dongqing Xu for the miP1a mip1b seeds, and Xing Shen for experimental assistance. This work was supported by grants from the National Key R&D Program of China (2016YFA0502900) and the National Science Foundation of China (31822004, 31770304, and 31770208). H.S. was supported by the Support Project of High-Level Teachers in Beijing Municipal Universities in the Period of 13th Five-Year Plan (CIT&TCD20190331). Q.W. was supported by a China Postdoctoral Science Foundation Grant (2019M650325).

Footnotes

The authors declare no competing interest.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission.

Data deposition: Sequence data in this study can be found in the Arabidopsis Genome Initiative or GenBank/EMBL data libraries under the following accession nos.: miP1a/BBX31 (AT3G21890), miP1b/BBX30 (AT4G15248), EIN3 (AT3G20770), EIL1 (AT2G27050), PIF1 (AT2G20180), PIF3 (AT1G09530), PIF4 (AT2G43010), PIF5 (AT3G59060), ERF1 (AT3G23240), EBF2 (AT5G25350), HLS1 (AT4G37580), PIL1 (AT2G46970), PIL2 (AT3G62090), RBCS1A (AT1G67090), PP2A (AT1G13320), and SAND (AT2G28390).

This article contains supporting information online at https://www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.2002313117/-/DCSupplemental.

Data Availability.

This article does not contain datasets, code, or materials in addition to those included.

References

- 1.Chen M., Chory J., Fankhauser C., Light signal transduction in higher plants. Annu. Rev. Genet. 38, 87–117 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Leivar P., Monte E., PIFs: Systems integrators in plant development. Plant Cell 26, 56–78 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.de Wit M., Galvão V. C., Fankhauser C., Light-mediated hormonal regulation of plant growth and development. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 67, 513–537 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wei N. et al., Arabidopsis COP8, COP10, and COP11 genes are involved in repression of photomorphogenic development in darkness. Plant Cell 6, 629–643 (1994). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Shi H. et al., Genome-wide regulation of light-controlled seedling morphogenesis by three families of transcription factors. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 115, 6482–6487 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zhong S. et al., Ethylene-orchestrated circuitry coordinates a seedling’s response to soil cover and etiolated growth. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 111, 3913–3920 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Shi H. et al., Seedlings transduce the depth and mechanical pressure of covering soil using COP1 and ethylene to regulate EBF1/EBF2 for soil emergence. Curr. Biol. 26, 139–149 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Shen X., Li Y., Pan Y., Zhong S., Activation of HLS1 by mechanical stress via ethylene-stabilized EIN3 is crucial for seedling soil emergence. Front. Plant Sci. 7, 1571 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Von Arnim A., Deng X. W., Light control of seedling development. Annu. Rev. Plant Physiol. Plant Mol. Biol. 47, 215–243 (1996). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lau O. S., Deng X. W., The photomorphogenic repressors COP1 and DET1: 20 years later. Trends Plant Sci. 17, 584–593 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Quail P. H. et al., Phytochromes: Photosensory perception and signal transduction. Science 268, 675–680 (1995). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rockwell N. C., Su Y. S., Lagarias J. C., Phytochrome structure and signaling mechanisms. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 57, 837–858 (2006). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Xu X., Paik I., Zhu L., Huq E., Illuminating progress in phytochrome-mediated light signaling pathways. Trends Plant Sci. 20, 641–650 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ni M., Tepperman J. M., Quail P. H., PIF3, a phytochrome-interacting factor necessary for normal photoinduced signal transduction, is a novel basic helix-loop-helix protein. Cell 95, 657–667 (1998). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Huq E. et al., Phytochrome-interacting factor 1 is a critical bHLH regulator of chlorophyll biosynthesis. Science 305, 1937–1941 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Shi H. et al., The red light receptor phytochrome B directly enhances substrate-E3 ligase interactions to attenuate ethylene responses. Dev. Cell 39, 597–610 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jeong J. et al., Phytochrome and ethylene signaling integration in Arabidopsis occurs via the transcriptional regulation of genes Co-targeted by PIFs and EIN3. Front. Plant Sci. 7, 1055 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Liu X. et al., EIN3 and PIF3 form an interdependent module that represses chloroplast development in buried seedlings. Plant Cell 29, 3051–3067 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Leivar P. et al., Multiple phytochrome-interacting bHLH transcription factors repress premature seedling photomorphogenesis in darkness. Curr. Biol. 18, 1815–1823 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Shin J. et al., Phytochromes promote seedling light responses by inhibiting four negatively-acting phytochrome-interacting factors. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 106, 7660–7665 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zhang X. et al., Integrated regulation of apical hook development by transcriptional coupling of EIN3/EIL1 and PIFs in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 30, 1971–1988 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ni W. et al., A mutually assured destruction mechanism attenuates light signaling in Arabidopsis. Science 344, 1160–1164 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Saghatelian A., Couso J. P., Discovery and characterization of smORF-encoded bioactive polypeptides. Nat. Chem. Biol. 11, 909–916 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hanada K. et al., Small open reading frames associated with morphogenesis are hidden in plant genomes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 110, 2395–2400 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Eguen T., Straub D., Graeff M., Wenkel S., MicroProteins: Small size-big impact. Trends Plant Sci. 20, 477–482 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Staudt A. C., Wenkel S., Regulation of protein function by “microProteins”. EMBO Rep. 12, 35–42 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bhati K. K. et al., Approaches to identify and characterize microProteins and their potential uses in biotechnology. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 75, 2529–2536 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.de Klein N., Magnani E., Banf M., Rhee S. Y., microProtein Prediction Program (miP3): A software for predicting microProteins and their target transcription factors. Int. J. Genomics 2015, 734147 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Graeff M. et al., MicroProtein-mediated recruitment of CONSTANS into a TOPLESS trimeric complex represses flowering in Arabidopsis. PLoS Genet. 12, e1005959 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Straub D., Wenkel S., Cross-species genome-wide identification of evolutionary conserved MicroProteins. Genome Biol. Evol. 9, 777–789 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Khanna R. et al., The Arabidopsis B-box zinc finger family. Plant Cell 21, 3416–3420 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Heng Y. et al., B-box containing proteins BBX30 and BBX31, acting downstream of HY5, negatively regulate photomorphogenesis in Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol. 180, 497–508 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Yadav A. et al., The B-Box-containing MicroProtein miP1a/BBX31 regulates photomorphogenesis and UV-B protection. Plant Physiol. 179, 1876–1892 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zhong S. et al., A molecular framework of light-controlled phytohormone action in Arabidopsis. Curr. Biol. 22, 1530–1535 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Zhang Y. et al., A quartet of PIF bHLH factors provides a transcriptionally centered signaling hub that regulates seedling morphogenesis through differential expression-patterning of shared target genes in Arabidopsis. PLoS Genet. 9, e1003244 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Seo P. J., Hong S. Y., Kim S. G., Park C. M., Competitive inhibition of transcription factors by small interfering peptides. Trends Plant Sci. 16, 541–549 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lyu M. et al., Oligomerization and photo-deoligomerization of HOOKLESS1 controls plant differential cell growth. Dev. Cell 51, 78–88.e3 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hornitschek P., Lorrain S., Zoete V., Michielin O., Fankhauser C., Inhibition of the shade avoidance response by formation of non-DNA binding bHLH heterodimers. EMBO J. 28, 3893–3902 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Leivar P., Quail P. H., PIFs: Pivotal components in a cellular signaling hub. Trends Plant Sci. 16, 19–28 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Jones S., An overview of the basic helix-loop-helix proteins. Genome Biol. 5, 226 (2004). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Bu Q., Castillon A., Chen F., Zhu L., Huq E., Dimerization and blue light regulation of PIF1 interacting bHLH proteins in Arabidopsis. Plant Mol. Biol. 77, 501–511 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Song J. et al., Biochemical and structural insights into the mechanism of DNA recognition by Arabidopsis ETHYLENE INSENSITIVE3. PLoS One 10, e0137439 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Solano R., Stepanova A., Chao Q., Ecker J. R., Nuclear events in ethylene signaling: A transcriptional cascade mediated by ETHYLENE-INSENSITIVE3 and ETHYLENE-RESPONSE-FACTOR1. Genes Dev. 12, 3703–3714 (1998). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Lian T. F., Xu Y. P., Li L. F., Su X. D., Crystal structure of tetrameric Arabidopsis MYC2 reveals the mechanism of enhanced interaction with DNA. Cell Rep. 19, 1334–1342 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Chang K. N. et al., Temporal transcriptional response to ethylene gas drives growth hormone cross-regulation in Arabidopsis. eLife 2, e00675 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Benezra R., Davis R. L., Lockshon D., Turner D. L., Weintraub H., The protein Id: A negative regulator of helix-loop-helix DNA binding proteins. Cell 61, 49–59 (1990). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Morrow M. A., Mayer E. W., Perez C. A., Adlam M., Siu G., Overexpression of the Helix-Loop-Helix protein Id2 blocks T cell development at multiple stages. Mol. Immunol. 36, 491–503 (1999). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kondo T., Raff M., The Id4 HLH protein and the timing of oligodendrocyte differentiation. EMBO J. 19, 1998–2007 (2000). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Ruzinova M. B., Benezra R., Id proteins in development, cell cycle and cancer. Trends Cell Biol. 13, 410–418 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Yang C., Lu X., Ma B., Chen S. Y., Zhang J. S., Ethylene signaling in rice and Arabidopsis: Conserved and diverged aspects. Mol. Plant 8, 495–505 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Gommers C. M. M., Monte E., Seedling establishment: A dimmer switch-regulated process between dark and light signaling. Plant Physiol. 176, 1061–1074 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Stepanova A. N., Hoyt J. M., Hamilton A. A., Alonso J. M., A Link between ethylene and auxin uncovered by the characterization of two root-specific ethylene-insensitive mutants in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 17, 2230–2242 (2005). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.An F. et al., Coordinated regulation of apical hook development by gibberellins and ethylene in etiolated Arabidopsis seedlings. Cell Res. 22, 915–927 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Chao Q. et al., Activation of the ethylene gas response pathway in Arabidopsis by the nuclear protein ETHYLENE-INSENSITIVE3 and related proteins. Cell 89, 1133–1144 (1997). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Al-Sady B., Ni W., Kircher S., Schäfer E., Quail P. H., Photoactivated phytochrome induces rapid PIF3 phosphorylation prior to proteasome-mediated degradation. Mol. Cell 23, 439–446 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Nakagawa T. et al., Improved Gateway binary vectors: High-performance vectors for creation of fusion constructs in transgenic analysis of plants. Biosci. Biotechnol. Biochem. 71, 2095–2100 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Hong S. M., Bahn S. C., Lyu A., Jung H. S., Ahn J. H., Identification and testing of superior reference genes for a starting pool of transcript normalization in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell Physiol. 51, 1694–1706 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Remans T. et al., Reliable gene expression analysis by reverse transcription-quantitative PCR: Reporting and minimizing the uncertainty in data accuracy. Plant Cell 26, 3829–3837 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Wang Q. et al., Photoactivation and inactivation of Arabidopsis cryptochrome 2. Science 354, 343–347 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Zhong S. et al., EIN3/EIL1 cooperate with PIF1 to prevent photo-oxidation and to promote greening of Arabidopsis seedlings. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 106, 21431–21436 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Earley K. W. et al., Gateway-compatible vectors for plant functional genomics and proteomics. Plant J. 45, 616–629 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Gendrel A. V., Lippman Z., Martienssen R., Colot V., Profiling histone modification patterns in plants using genomic tiling microarrays. Nat. Methods 2, 213–218 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Shi H. et al., HFR1 sequesters PIF1 to govern the transcriptional network underlying light-initiated seed germination in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 25, 3770–3784 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Lee J. et al., Analysis of transcription factor HY5 genomic binding sites revealed its hierarchical role in light regulation of development. Plant Cell 19, 731–749 (2007). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Hellens R. P. et al., Transient expression vectors for functional genomics, quantification of promoter activity and RNA silencing in plants. Plant Methods 1, 13 (2005). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Vandenbussche F. et al., The auxin influx carriers AUX1 and LAX3 are involved in auxin-ethylene interactions during apical hook development in Arabidopsis thaliana seedlings. Development 137, 597–606 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

This article does not contain datasets, code, or materials in addition to those included.