Key Points

Question

Are mindfulness-based interventions associated with decreased anxiety in adults with cancer?

Findings

In this systematic review and meta-analysis of 28 randomized clinical trials with 3053 participants, mindfulness-based interventions were associated with reductions in the severity of anxiety in adults with cancer up to 6 months after delivery of mindfulness sessions compared with usual care, waitlist control, or no intervention; a concomitant reduction in the severity of depression and improvement in health-related quality of life was also observed. None of the trials used mindfulness-based interventions in children with cancer.

Meaning

Mindfulness-based interventions were associated with a reduction in anxiety and depression in adults with cancer.

This systematic review and meta-analysis of 28 randomized controlled trials examines the effectiveness in mindfulness-based interventions in reducing anxiety and depression in adult patients with cancer.

Abstract

Importance

Mindfulness-based interventions (MBIs), grounded in mindfulness, focus on purposely paying attention to experiences occurring at the present moment without judgment. MBIs are increasingly used by patients with cancer for the reduction of anxiety, but it remains unclear if MBIs reduce anxiety in patients with cancer.

Objective

To evaluate the association of MBIs with reductions in the severity of anxiety in patients with cancer.

Data Sources

Systematic searches of MEDLINE, Embase, Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials, CINAHL, PsycINFO, and SCOPUS were conducted from database inception to May 2019 to identify relevant citations.

Study Selection

Randomized clinical trials (RCTs) that compared MBI with usual care, waitlist controls, or no intervention for the management of anxiety in cancer patients were included. Two reviewers conducted a blinded screening. Of 101 initially identified studies, 28 met the inclusion criteria.

Data Extraction and Synthesis

Two reviewers independently extracted the data. The Cochrane Collaboration risk-of-bias tool was used to assess the quality of RCTs, and the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analyses reporting guideline was followed. Summary effect measures were reported as standardized mean differences (SMDs) and calculated using a random-effects model.

Main Outcomes and Measures

Our primary outcome was the measure of severity of short-term anxiety (up to 1-month postintervention); secondary outcomes were the severity of medium-term (1 to ≤6 months postintervention) and long-term (>6 to 12 months postintervention) anxiety, depression, and health-related quality of life of patients and caregivers.

Results

This meta-analysis included 28 RCTs enrolling 3053 adults with cancer. None of the trials were conducted in children. Mindfulness was associated with significant reductions in the severity of short-term anxiety (23 trials; 2339 participants; SMD, −0.51; 95% CI, −0.70 to −0.33; I2 = 76%). The association of mindfulness with short-term anxiety did not vary by evaluated patient, intervention, or study characteristics. Mindfulness was also associated with the reduction of medium-term anxiety (9 trials; 965 participants; SMD, −0.43; 95% CI, −0.68 to −0.18; I2 = 66%). No reduction in long-term anxiety was observed (2 trials; 403 participants; SMD, −0.02; 95% CI, −0.38 to 0.34; I2 = 68%). MBIs were associated with a reduction in the severity of depression in the short term (19 trials; 1874 participants; SMD, −0.73; 95% CI; −1.00 to −0.46; I2 = 86%) and the medium term (8 trials; 891 participants; SMD, −0.85; 95% CI, −1.35 to −0.35; I2 = 91%) and improved health-related quality of life in patients in the short term (9 trials; 1108 participants; SMD, 0.51; 95% CI, 0.20 to 0.82; I2 = 82%) and the medium term (5 trials; 771 participants; SMD, 0.29; 95% CI, 0.06 to 0.52; I2 = 57%).

Conclusions and Relevance

In this study, MBIs were associated with reductions in anxiety and depression up to 6 months postintervention in adults with cancer. Future trials should explore the long-term association of mindfulness with anxiety and depression in adults with cancer and determine its efficacy in more diverse cancer populations using active controls.

Introduction

Anxiety is highly prevalent among patients with cancer.1,2,3 Approximately 10% to 19% of adults with cancer experience anxiety during or after cancer treatment.2,3,4 Similarly, 14% to 27% of children with cancer experience anxiety.5,6 Cancer-related anxiety is multifactorial and may stem from patients’ psychologic response to the diagnosis and treatment of cancer and from changes in body image, sexual function, work, and social interactions.1,7 Anxiety reduces patients’ health-related quality of life (HRQoL) and can also reduce treatment adherence.8,9,10 In 2014, the American Society of Clinical Oncology recommended individual and group psychologic interventions, such as cognitive-behavioral therapy, applied relaxation, and pharmacologic approaches, to treat cancer-related anxiety.11 Mindfulness, a type of mind and body intervention, was not identified as an intervention for the management of anxiety in these guidelines.11,12

Mindfulness is a technique whereby a person becomes purposefully cognizant of the present moment and learns to address their thoughts, feelings, and sensations in a nonjudgmental manner.13,14 Many patients with cancer use mindfulness to manage anxiety, depression, and emotional distress during and after their cancer treatment.15,16,17,18,19 Several randomized clinical trials (RCTs) conducted during the past decade18,19,20,21,22 have examined the effect of mindfulness-based interventions on anxiety, depression, psychological distress, and HRQoL in adults with cancer. The results of these trials are conflicting about the effect of mindfulness on anxiety.18,20,21,23

Previous systematic reviews have evaluated the associations of mindfulness-based stress reduction (MBSR), a widely used mindfulness-based intervention, with psychologic symptoms and HRQoL among patients with breast cancer.24,25,26,27 These reviews did not explore the association of mindfulness with anxiety in other cancer types and did not examine different types of mindfulness-based interventions, such as mindfulness-based cognitive therapy (MBCT) or mindfulness-based cancer recovery (MBCR).24,25,26,27 Since the publication of these systematic reviews, several RCTs have been performed. These trials evaluated the effect of various mindfulness-based interventions in patients with cancer.

In light of the growing literature on the use of mindfulness-based interventions for the reduction of anxiety and depression among patients with cancer, we conducted this systematic review and meta-analysis to synthesize the existing evidence. Our primary objective was to determine whether mindfulness-based interventions were associated with reductions in the severity of anxiety in adults and children with cancer. Our secondary objective was to determine whether these associations varied by cancer type, intervention, or methods of the study.

Methods

Search Strategy and Identification of Studies

Our systematic review was conducted according to an a priori protocol. We searched MEDLINE, Embase, Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials, CINAHL, PsycINFO, and SCOPUS from database inception to May 2019 to identify relevant citations of published RCTs, using individualized systematic search strategies for each database. The search strategy was developed by a health sciences librarian and peer reviewed by a second librarian using the Peer Review of Electronic Search Strategies checklist.28 The search strategy is presented in eTable 1 in the Supplement. We contacted study authors when required to request pertinent unpublished data or seek clarification on study methods or results. Reference lists of narrative and systematic reviews and of the included trials were hand-searched for additional citations. Our findings are reported according to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) reporting guideline.

Study Selection and Data Extraction

We included RCTs comprised of a patient population of adults (≥18 years) or children (<18 years) with cancer or who were undergoing hematopoietic stem cell transplant as a treatment for cancer (≥80% of the study population). Enrolled patients were randomized to mindfulness-based interventions or usual care, waitlist, no intervention, or sham control groups for the management of anxiety. We excluded observational, quasi-randomized, crossover, or cluster-randomized trial designs and trials that did not report any outcomes of interest to this review. We did not restrict inclusion by language or date of publication.

Two reviewers (S.O. and J.Y.) independently evaluated the titles and abstracts. The full text of any citation considered potentially relevant by either reviewer was retrieved and assessed for eligibility. The inclusion of trials in this meta-analysis was determined by agreement of the 2 reviewers with discrepancies resolved by a third reviewer (L.S., A.M.A-S, or R.Z.).

We extracted data from included trials using standardized data extraction forms. Study-level variables included the year of publication and enrollment, country of study, age of participants (adults vs children), cancer diagnosis (breast, prostate, other cancer, or more than 1 cancer type), cancer stage (nonmetastatic, metastatic, or both), the timing of intervention (during cancer treatment, following completion of treatment, or both), selective enrollment of palliative care patients (author defined), presence of anxiety as an eligibility criterion for recruitment (author-defined threshold), characteristics of the intervention and control groups, and anxiety, depression, and HRQoL scores up to 1 month, between 1 and 6 months inclusive, and from 6 months up to 1 year postintervention. We decided a priori to include overall or global HRQoL scores for the data synthesis. General health HRQoL scores were extracted from the studies that did not provide global or overall HRQoL scores.

Outcomes

Incorporating recommendations from patients and stakeholders, our primary outcome was self-reported short-term (≤1 month postintervention) severity of anxiety measured by any anxiety assessment scale. For studies that used more than 1 type of anxiety assessment scale, we defined a hierarchy of anxiety assessment scales based on the most prevalent scale used among the included trials to use in the primary analysis (eTable 2 in the Supplement). For instance, if a trial reported anxiety using both the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale–Anxiety (HADS-A) and the Beck Anxiety Inventory scale, the anxiety scores measured by the HADS-A scale were used for the primary outcome. Our secondary outcomes were medium-term (1 to ≤6 months postintervention) and long-term (>6 to 12 months postintervention) severity of self-reported anxiety, self-reported severity of depression across all the depression scales used in the included studies, patients’ overall or general HRQoL scores assessed by self-reported HRQoL questionnaires, and caregivers’ HRQoL scores assessed by self-reported questionnaires in short-, medium-, and long-term follow up.

Intervention and Comparator

Mindfulness was defined as a technique in which a person learns to focus attention in the present to become mindful of thoughts, feelings, and sensations and observes them in a nonjudgmental way to achieve greater calmness, physical relaxation, and psychologic balance.13,14 For our review, we included the mindfulness-based interventions (eg, MBSR, MBCT, MBCR, or mindfulness-based art therapy [MBAT]) that use mindfulness as the foundation of a therapeutic intervention instead of as an ancillary component.13,14 Interventions that include mindfulness as 1 of many elements (eg, yoga, Qigong, and tai chi) were not included because it is difficult to determine the effect of mindfulness in the setting of the physical movement. The control groups in the trials were usual care, waitlist, no intervention, or sham control.

Risk of Bias Assessment

We assessed the internal validity of included trials using the Cochrane Collaboration Risk of Bias tool.28,29 This tool categorizes the overall risk of study bias and consists of 6 domains (ie, sequence generation, allocation concealment, blinding, incomplete outcome data, selective outcome reporting, and other sources of bias). Each domain is rated low risk, unclear risk, or high risk. Information regarding the risk of bias was used to guide sensitivity analyses and explore sources of heterogeneity. Discrepancies in assessments between the 2 reviewers were resolved by consensus or by a third reviewer (A.M.A-S. or L.S.), as required.

Statistical Analysis

We used the standardized mean difference (SMD) to synthesize data across studies, which measured anxiety, depression, or HRQoL using a variety of scales.29 Weighted mean difference (WMD) was used to synthesize data for analyses concerning specific anxiety and depression scales. A summary effect estimate less than 0 indicates that the mean score was lower (ie, better) in the mindfulness group compared with the control group. The generic inverse variance method was used to weight the effects. A random-effects model was used for all analyses. We assessed statistical heterogeneity between trials using the I2 statistic.30

For the primary outcome, we evaluated potential publication bias using funnel plot analysis and visual inspection of the forest plot.31 In the event of potential publication bias, the trim-and-fill technique was used to determine the effect of potential bias using Comprehensive Meta-analysis software, version 2 (Biostat).32 Meta-analyses were conducted using Review Manager, version 5.3.5 (The Cochrane Collaboration). All tests of statistical inference reflect a 2-sided α < .05.

We evaluated the following factors in subgroup analyses: (1) type of cancer (ie, breast cancer vs mixed cancer population and other cancer types), (2) cancer stage (ie, nonmetastatic vs metastatic vs both nonmetastatic and metastatic), (3) timing of intervention (ie, during cancer treatment vs after cancer treatment vs both during and after cancer treatment), (4) mindfulness-based intervention type (ie, MBCT vs MBSR vs MBCR vs MBAT), (5) group vs nongroup or individual delivery setting, (6) number of weeks of intervention (<8 weeks vs ≥8 weeks), (7) sequence generation (ie, low vs high or unclear risk of bias), and (8) allocation concealment (low vs unclear or high risk of bias). We determined whether the mindfulness-based intervention effect varied by subgroups using the P value for interaction.

Results

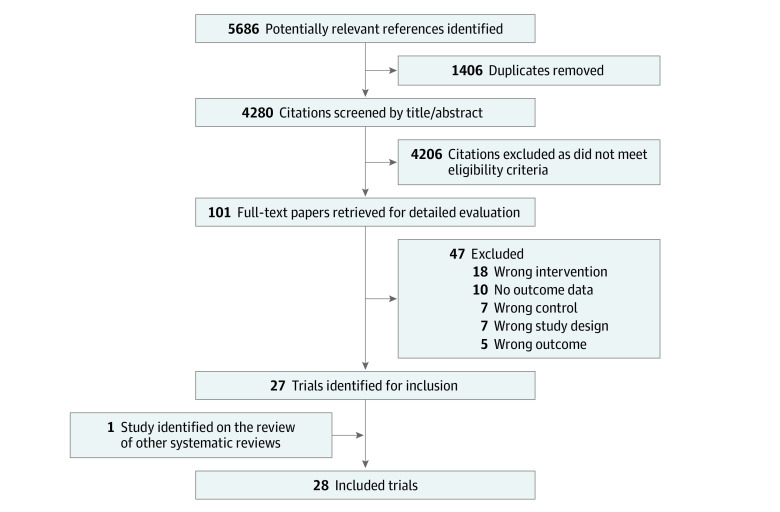

Our electronic search strategy identified 5686 citations, of which 27 trials met the eligibility criteria (Figure 1).16,18,19,20,21,22,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51,52,53,54 We included 1 additional trial identified through hand searching. One trial by Compen et al21 randomized patients to in-person MBCT, internet-based MBCT, and usual care cohorts and thus represented 2 separate analyses, for an overall total of 29 mindfulness-based comparisons (3053 participants). All trials were published as full-text articles in English. These trials were conducted in 13 countries from 4 continents (Table 1). None of the trials included children or adolescents with cancer. Trials of breast cancer patients were the most common (12 trials [42.8%]). Even in trials including more than 1 type of cancer (11 trials), breast cancer was the most common diagnosis in all but 1.21,40,44,49,51,53

Figure 1. Flow Diagram of Trial Identification and Selection.

Table 1. Characteristics of 28 Studies Included in the Systematic Review.

| Source; Countrya | Age range, y | Cancer diagnosis | Cancer stage | Timing | Total patients, No. | Intervention | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Type | Delivery | Mode | Duration, wk | ||||||

| Liu et al,33 2019; China | NA | Thyroid | Nonmetastatic | On therapy | 120 | MBSR | Group | In-person | 8 |

| Franco et al,34 2019; Spain | NA | Breast | NA | NA | 36 | Mindfulness-based program | Group | In-person | 7 |

| Compen et al,21 2018; the Netherlands | NA | >1 | Nonmetastatic and metastatic | Both | 116 | MBCT and eMBCT | Group | In-person and web-based | 8 |

| Lorca et al,35 2018; Spain | NA | >1 | NA | Both | 108 | Mindfulness-based program | Individual | CD | 50-60 min |

| Russell et al,36 2018; Australia | 22-78 | Melanoma | Nonmetastatic | Off therapy | 69 | Mindfulness-based program | Nongroup | Web-based | 6 |

| Chambers et al,37 2017; Australia and New Zealand | NA | Prostate | Nonmetastatic and metastatic | Both | 189 | MBCT | Group | In-person | 8 |

| Kenne et al,38 2017; Sweden | 34-80 | Breast | NA | Off therapy | 120 | MBSR | Group | In-person | 8 |

| Schellekens et al,39 2017; the Netherlands | NA | Lung | Nonmetastatic and metastatic | Both | 63 | MBSR | Group | In-person | 8 |

| Zhang et al,22 2017; China | 17-71 | Leukemia | NA | On therapy | 65 | Mindfulness-based psychological care | Nongroup | In-person | 5 |

| Zhang et al,19 2017; China | 30-62 | Breast | Nonmetastatic | Off therapy | 60 | MBSR | Group | In-person | 8 |

| Blaes et al,40 2016; United States | 36-79 | >1 | Nonmetastatic | Off therapy | 42 | MBCR | Group | In-person | 8 |

| Jang et al,41 2016; Korea | NA | Breast | Nonmetastatic | Off therapy | 24 | MBAT | Group | In-person | 12 |

| Johannsen et al,42 2016; Denmark | NA | Breast | Nonmetastatic | Off therapy | 129 | MBCT | Group | In-person | 8 |

| Lengacher et al,18 2016; United States | NA | Breast | Nonmetastatic | Off therapy | 322 | MBSR | Group | In-person | 6 |

| Vaziri et al,20 2016; Iran | NA | Breast | Nonmetastatic | On therapy | 20 | MBCT | Group | NA | 8 |

| Bower et al,43 2015; United States | 28.4-60 | Breast | Nonmetastatic | Off therapy | 71 | Mindful awareness practices | Group | In-person | 6 |

| Johns et al,44 2015; United States | NA | >1 | Nonmetastatic and metastatic | Off therapy | 35 | MBSR | Group | In-person | 7 |

| Kingston et al,45 2015; Ireland | NA | >1 | NA | Both | 16 | MBCT | Group | In-person | 8 |

| Zernicke et al,46 2014; Canada | 29-79 | >1 | Nonmetastatic and metastatic | Off therapy | 62 | MBCR | Group | Web-based | 8 |

| Würtzen et al,47 2013; Denmark | NA | Breast | Nonmetastatic | Both | 336 | MBSR | Group | In-person | 8 |

| Hoffman et al,16 2012; United Kingdom | 18-80 | Breast | Nonmetastatic | Off therapy | 229 | MBSR | Group | In-person | 8 |

| Henderson et al,48 2013; United States | NA | Breast | Nonmetastatic | Both | 111 | MBSR | Group | In-person | 20 |

| Lerman et al,49 2012; United States | NA | >1 | NA | Both | 77 | MBSR | Group | In-person | 8 |

| Bränström et al,50 2010; Sweden | NA | >1 | NA | NA | 85 | MBSR | Group | In-person | 8 |

| Foley et al,51 2010; Australia | 24-78 | >1 | Nonmetastatic and metastatic | NA | 115 | MBCT | Group | In-person | 8 |

| Lengacher et al,52 2009; United States | NA | Breast | Nonmetastatic | Off therapy | 84 | MBSR | Group | In-person | 6 |

| Monti et al,53 2006; United States | 26-82 | >1 | Nonmetastatic and metastatic | Both | 111 | MBAT | Group | In-person | 8 |

| Speca et al,542000; Canada | NA | >1 | Nonmetastatic and metastatic | Both | 109 | MBSR | Group | In-person | 7 |

Abbreviations: eMBCT, web-based mindfulness-based cognitive therapy; MBAT, mindfulness-based art therapy; MBCR, mindfulness-based cancer recovery; MBSR, mindfulness-based stress reduction; NA, not available.

All included trials were conducted among adults.

The 2 most common mindfulness-based interventions used in the trials were MBSR (13 trials [46.4%]) and MBCT (6 trials [24.1%]). Trials used usual care (14 trials) and waitlist (14 trials) equally as comparators. The median duration of intervention was 8 weeks (range, 1 hour to 20 weeks). Anxiety assessment scales used across all included trials are listed in eTable 2 in the Supplement. Among the 12 reported anxiety scales, the 2 most common scales were the HADS-A (5 trials) and the State-Trait Anxiety Inventory (STAI; 5 trials).

The risk of bias assessment is presented in eFigure 1 in the Supplement. As participants and outcome assessors could not be blinded because of the nature of the interventions and patient-reported anxiety outcome, all trials were considered at a high risk of performance and detection bias.

Primary Outcome

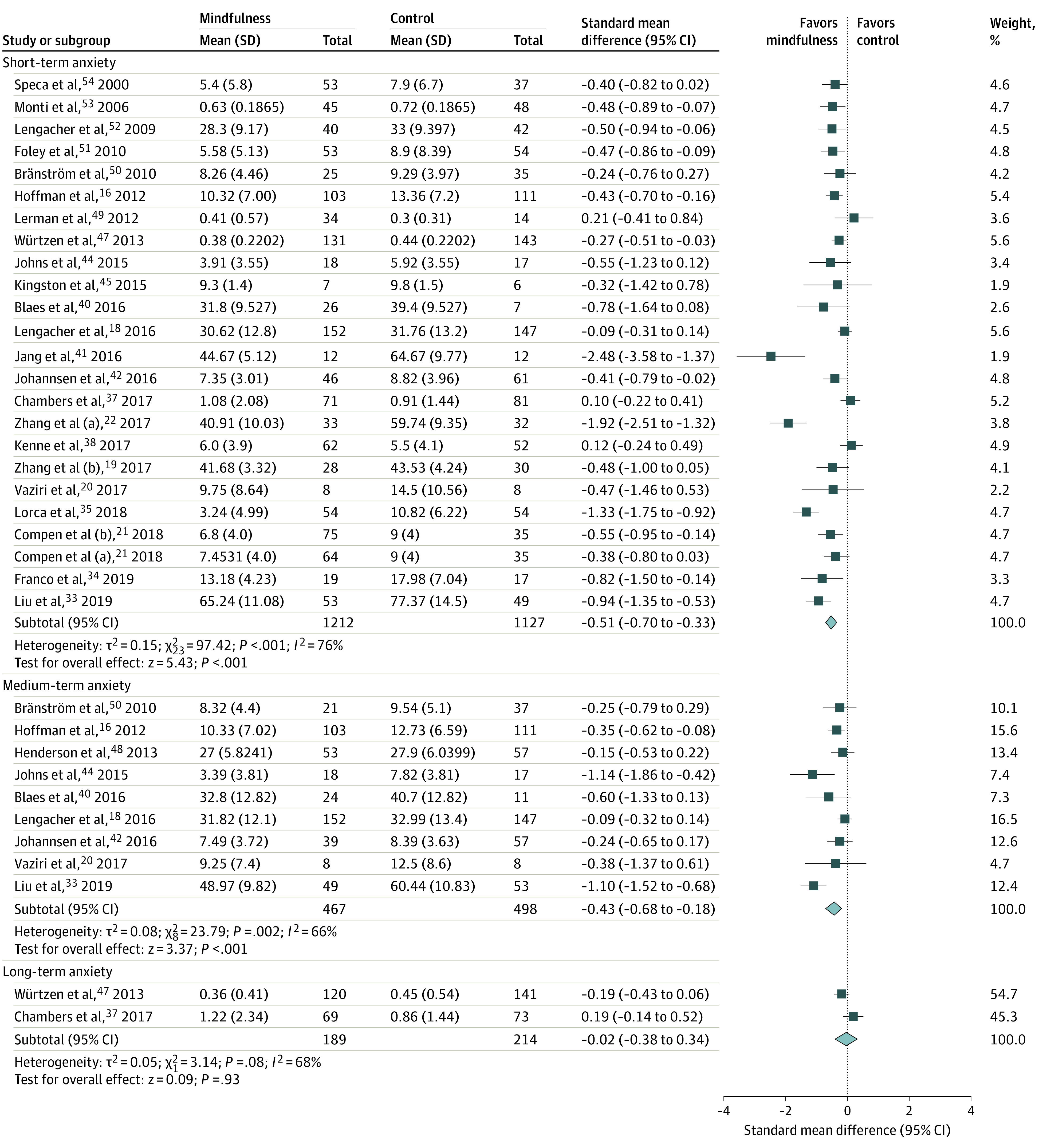

Mindfulness-based interventions were associated with reductions in the severity of short-term anxiety (23 trials; 2339 participants; SMD, −0.51; 95% CI, −0.70 to −0.33; I2 = 76%) (Figure 2). Similar results were found when limiting the analysis to trials that measured anxiety using the HADS-A (6 trials; 503 participants; WMD, −1.03; 95% CI, −1.82 to −0.23; I2 = 32%) or STAI scales (5 trials; 580 participants; WMD, −4.00; 95% CI, −5.21 to −2.78; I2 = 80%). On sensitivity analysis, the effect estimate was reduced (22 trials; 2231 participants; SMD, −0.46; 95% CI, −0.64 to −0.29; I2 = 72%) when the trial by Lorca et al35 was excluded because of the very short duration of the intervention (50-60 minutes). Examination of the funnel plot for the primary outcome showed the potential absence of small-size studies showing no effect of mindfulness; however, no statistically significant evidence of publication bias was present using trim-and-fill methods (eFigure 2 in the Supplement).

Figure 2. Forest Plot of Association of Mindfulness-Based Interventions With Anxiety in the Short Term, Medium Term, and Long Term.

The size of the square reflects study’s relative weight, and the diamond represents the aggregate standardized mean difference and 95% CI. Studies that have multiple listed entries perform multiple analyses between distinct patient groups.

Table 2 illustrates the a priori subgroup analyses performed to explore heterogeneity in the association of mindfulness with a reduction in short-term anxiety. Subgroup analyses that included the type and stage of cancer, timing of treatment, intervention type, duration of treatment, delivery setting, number of weeks of intervention, and the presence of adequate randomization or allocation concealment could not explain the heterogeneity in the effect of mindfulness (Table 2).

Table 2. Association of Mindfulness-Based Interventions With Short-Term Anxiety by Patient, Intervention, and Methodological Factors in 28 Included Studies.

| Subgroup | Trials, No. | Patients, No. | SMD (95% CI) | I2, % | P value for interaction |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Type of cancer | |||||

| Breast | 10 | 1224 | −0.40 (−0.62 to −0.17) | 68 | .33 |

| >1 Cancer and other cancer types | 14 | 1115 | −0.57 (−0.86 to −0.29) | 76 | |

| Cancer stage | |||||

| Nonmetastatic | 10 | 1209 | −0.52 (−0.73 to −0.31) | 69 | .31 |

| Metastatic | 0 | 0 | NA | ||

| Metastatic and nonmetastatic | 7 | 686 | −0.36 (−0.55 to −0.16) | 37 | |

| Timing of intervention | |||||

| During cancer treatment | 3 | 183 | −1.16 (−1.94 to −0.38) | 78 | .19 |

| After cancer treatment | 9 | 966 | −0.43 (−0.70 to −0.17) | 71 | |

| Both during and after cancer treatment | 9 | 989 | −0.39 (−0.68 to −0.11) | 76 | |

| Intervention type | |||||

| Mindfulness-based stress reduction | 11 | 1376 | −0.32 (−0.49 to −0.14) | 57 | .52 |

| Mindfulness-based cognitive therapy | 7 | 604 | −0.32 (−0.53 to −0.12) | 31 | |

| Mindfulness-based art therapy | 2 | 117 | −1.41 (−3.36 to 0.54) | 91 | |

| Mindfulness-based cancer recovery | 1 | 33 | −0.78 (−1.64 to 0.08) | NAa | |

| Delivery setting | |||||

| Group | 21 | 2067 | −0.39 (−0.54 to −0.24) | 60 | .07 |

| Nongroup | 3 | 272 | −1.19 (−2.05 to −0.34) | 90 | |

| Length of intervention, wks | |||||

| <8 | 7 | 715 | −0.78 (−1.27 to −0.29) | 88 | .14 |

| ≥8 | 17 | 1624 | −0.39 (−0.57 to −0.21) | 71 | |

| Adequate sequence generation | |||||

| Yes | 18 | 2028 | −0.43 (−0.61 to −0.26) | 71 | .23 |

| Unclear | 6 | 311 | −0.83 (−1.46 to −0.21) | 82 | |

| Adequate allocation concealment | |||||

| Yes | 10 | 1361 | −0.36 (−0.54 to −0.17) | 63 | .32 |

| Unclear | 14 | 978 | −0.68 (−1.02 to −0.34) | 76 |

Abbreviations: NA, not applicable; SMD, standardized mean difference.

I2 is not calculated here because only 1 study reported this outcome.

Secondary Outcomes

Mindfulness-based interventions reduced the severity of medium-term (1 to 6 months postintervention) anxiety (9 trials; 965 participants; SMD, −0.43; 95% CI, −0.68 to −0.18; I2 = 66%) (Figure 2). Mindfulness-based interventions were not associated with a long-term (>6 months to 1 year postintervention) reduction in anxiety (2 trials; 403 participants; SMD, −0.02; 95% CI, −0.38 to 0.34; I2 = 68%) (Figure 2).

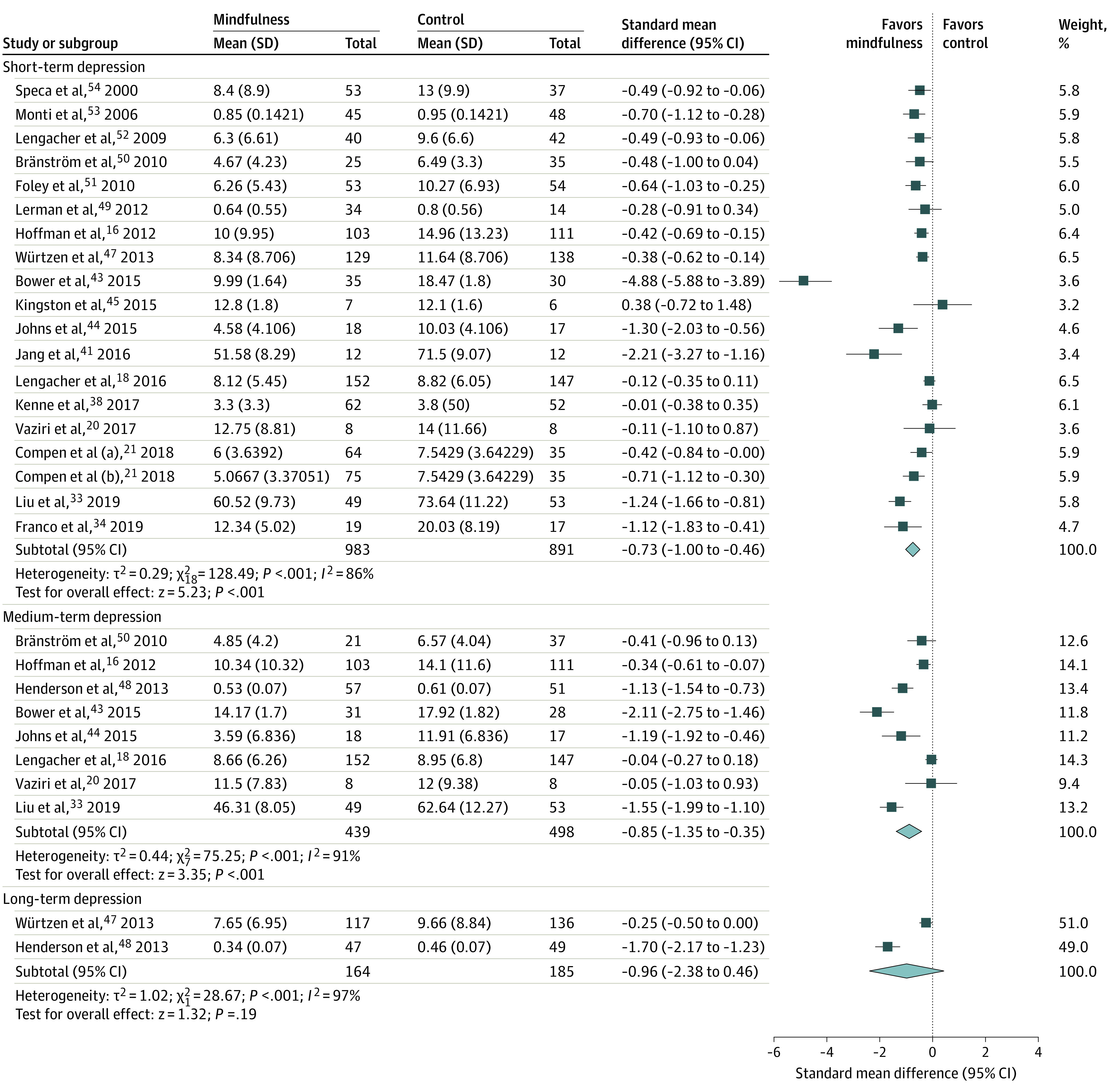

Mindfulness-based interventions were associated with reductions in the severity of short-term depression (19 trials; 1874 participants; SMD, −0.73; 95% CI, −1.00 to −0.46; I2 = 86%) (Figure 3) and medium-term depression (8 trials; 891 participants; SMD, −0.85; 95% CI, −1.35 to −0.35; I2 = 91%) (Figure 3). The list of all depression assessment scales used in the included trials is provided in eTable 3 in the Supplement. Mindfulness-based interventions were associated with a reduction in depression when the analysis was limited to trials reporting the HADS-D (5 trials; 396 participants; WMD, −1.16; 95% CI, −1.94 to −0.38; I2 = 54%). Mindfulness was not associated with a reduction in the severity of depression in the long term (2 trials; 349 participants; SMD, −0.96; 95% CI, −2.38 to 0.46; I2 = 97%) (Figure 3).

Figure 3. Forest Plot of Association of Mindfulness-Based Interventions With Depression in Short Term, Medium Term, and Long Term.

The size of the square reflects study’s relative weight, and the diamond represents the aggregate standardized mean difference and 95% CI. Studies that have multiple listed entries perform multiple analyses between distinct patient groups.

Mindfulness-based interventions were associated with improved overall HRQoL scores in the short term (9 trials; 1108 participants; SMD, 0.51; 95% CI, 0.20 to 0.82; I2 = 82%) and medium term (5 trials; 771 participants; SMD, 0.29; 95% CI, 0.06 to 0.52; I2 = 57%). The included HRQoL assessment scales are listed in eTable 4 in the Supplement. The only trial reporting the effect of mindfulness on long-term HRQoL did not demonstrate any improvement in HRQoL (1 trial; 153 participants; WMD, 0.78; 95% CI, −5.98 to 7.54). None of the included trials reported caregivers’ HRQoL.

Discussion

In this systematic review and meta-analysis, we found that mindfulness-based interventions were associated with reductions in the severity of anxiety in the short term and medium term, but not in the long term, among adults with cancer. Mindfulness was associated with a significant improvement in short-term and medium-term, but not in long-term, depression or HRQoL.

Our study builds on previously published systematic reviews.24,25,26,27 We incorporated diverse mindfulness-based interventions across all cancer populations, whereas the majority of the published systematic reviews were narrowly focused on MBSR interventions in patients with breast cancer.24,26,27 The only published systematic review examining various types of mindfulness interventions across different cancer diagnoses in adults included only 9 trials and did not use rigorous methods for meta-analysis and assessing the quality of included trials.55 In contrast, we used robust methods for identifying trials and synthesizing data. Our review identified a larger number of trials, synthesized the effect of treatment at various time points, and assessed subgroup differences and the risk of bias across included studies. The larger sample size improved the precision of the effect estimates and enabled us to perform subgroup analysis to explore heterogeneity.

An SMD of 0.51 suggests a moderate reduction in short-term anxiety associated with mindfulness.56,57 This association with reduction in short-term anxiety remained significant even when studies using the HADS-A and STAI were analyzed separately. The minimum clinically important difference (MCID) associated with HADS-A and STAI has not been identified for patients with cancer in the literature. The reported MCID for HADS-A among patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease is 1.5.58 If we extrapolate the MCID of the HADS-A scale from patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease to patients with cancer, the observed reduction in short-term anxiety on the HADS-A scale (1.03) is lower than the clinically meaningful threshold. Similar to anxiety, the observed short-term association of mindfulness with depression could not reach a clinically significant threshold. However, it should be noted that behavioral therapies, recommended by American Society of Clinical Oncology as 1 of the modalities for the treatment of anxiety and depression in adults with cancer, are associated with small to moderate effect sizes, similar to mindfulness-based interventions.11,59 Furthermore, mindfulness-based interventions also positively affect other symptoms, such as fatigue, distress, and pain in patients with cancer.60,61 Therefore, we suggest that mindfulness-based interventions should be considered an effective treatment option for reducing short-term and medium-term anxiety among adults with cancer. Comparing mindfulness-based interventions with other effective interventions for anxiety, such as drugs and behavioral therapies, should be the focus of future research in adults with cancer.

We also demonstrated that, in the longer term, mindfulness-based interventions were associated with little or no benefit on anxiety, depression, or quality of life. Our confidence in the long-term effects of mindfulness-based interventions is low because only 2 trials reported the long-term effects of mindfulness. It is plausible that the absence of booster or follow-up sessions after an initial 8 to 12 weeks of intervention might have diminished the durability of effect. As mindfulness is a skill-building approach, booster sessions may provide participants with the opportunity to master difficult skills and to generalize the mindfulness skills to newly encountered situations in life.

The effect of mindfulness on short-term anxiety did not differ by the assessed patient, intervention, and study characteristics. Specifically, the short-term benefits of mindfulness on anxiety were dependent neither on the type of cancer nor on the treatment phase. These results suggest that examined mindfulness-based interventions could result in the reduction of short-term anxiety of adults regardless of cancer type or stage of treatment. Furthermore, the association of mindfulness with reductions in short-term anxiety was not restricted to studies providing 8 weeks or more of mindfulness and group sessions; instead, the reduction in anxiety was marginally higher when mindfulness was delivered in the individual setting. In clinical practice, mindfulness-based interventions are typically offered in a group setting during an 8-week period.21,26,37 The longer-duration group sessions can be challenging for patients who either have complications related to cancer or are on active treatment. Young adults with cancer who are well connected with technology may also prefer shorter mindfulness sessions delivered by telehealth, video-interface, or a mobile application.62 Our findings suggest that individually delivered or shorter duration mindfulness-based interventions can be offered to the patients with cancer who cannot commit to group sessions or 8 weeks of intervention due to their illnesses or other barriers.

Limitations

Our systematic review has limitations that deserve comment. We cannot be certain that the observed treatment gains were exclusively due to the mindfulness intervention and not because of the facilitator’s attention, group support, and social interaction, given that none of the trials included an attention control group that matched the intervention group on all of these elements. These nonspecific factors are inherent components of the mindfulness intervention and can potentially affect the outcome. Women were overrepresented in the trials with mixed cancer populations,21,49,51,53 and 43% of included trials were done in patients with breast cancer who had completed curative treatment. The effect size for men in the gender-inclusive trials was not reported separately.21,49,51,53 The only trial that exclusively enrolled men with advanced prostate cancer did not show any reduction in anxiety.37 Men may be less receptive and responsive to mindfulness because of their different coping mechanisms than women.63 Therefore, further investigation of how gender affects the efficacy of mindfulness is warranted. There was also no representation of patients in palliative care or undergoing hematopoietic stem cell transplant in the included trials. None of the included trials were conducted in children or in patients with metastatic disease exclusively. Consequently, the results of this meta-analysis may not be generalizable to all cancer populations and settings. Most included trials did not use standardized tools to measure the total time spent practicing mindfulness per week or reported changes in the mindfulness. These factors may explain the heterogeneity in the measured effect, which subgroup analysis did not demonstrate. Other unmeasured patient characteristics in the included trials may also have contributed to the heterogeneity. Finally, imprecision, related to the small sample size, limited our confidence in the long-term effects of mindfulness-based interventions on the studied outcomes.

Conclusions

In this study, mindfulness-based interventions were associated with short-term and medium-term reductions in anxiety and depression along with improved quality of life among adult patients with cancer. Future studies should assess the efficacy of mindfulness in different settings, include diverse cancer populations such as children and men, and compare mindfulness with other effective interventions for anxiety and depression.

eTable 1. Search Strategy

eTable 2. Self-reported Anxiety Assessment Scales Used in the Included Trials (n = 28)

eTable 3. Self-reported Depression Assessment Scales Used in the Included Trials (n = 28)

eTable 4. Self-reported Health-related Quality of Life Assessment Scales Used in the Included Trials (n = 28)

eFigure 1. Summary of the Risk of Bias of Studies Included in the Systematic Review (n = 28)

eFigure 2. Funnel Plot “Trim-and-Fill” Technique Assessing Publication Bias for Short-term Reduction in Severity of Anxiety

References

- 1.Pitman A, Suleman S, Hyde N, Hodgkiss A. Depression and anxiety in patients with cancer. BMJ. 2018;361:k1415. doi: 10.1136/bmj.k1415 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Linden W, Vodermaier A, Mackenzie R, Greig D. Anxiety and depression after cancer diagnosis: prevalence rates by cancer type, gender, and age. J Affect Disord. 2012;141(2-3):343-351. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2012.03.025 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mitchell AJ, Chan M, Bhatti H, et al. . Prevalence of depression, anxiety, and adjustment disorder in oncological, haematological, and palliative-care settings: a meta-analysis of 94 interview-based studies. Lancet Oncol. 2011;12(2):160-174. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(11)70002-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mitchell AJ, Ferguson DW, Gill J, Paul J, Symonds P. Depression and anxiety in long-term cancer survivors compared with spouses and healthy controls: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Oncol. 2013;14(8):721-732. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(13)70244-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.von Essen L, Enskär K, Kreuger A, Larsson B, Sjödén PO. Self-esteem, depression and anxiety among Swedish children and adolescents on and off cancer treatment. Acta Paediatr. 2000;89(2):229-236. doi: 10.1111/j.1651-2227.2000.tb01221.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Buchanan N, Maloney K, Tsang S, Stork LC, Neglia JP, Kadan-Lottick NS. Risk of depression, anxiety, and somatization one month after diagnosis in children with standard risk ALL on COG AALL0331. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26(15_suppl):10052. doi: 10.1200/jco.2008.26.15_suppl.10052 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Stark DP, House A. Anxiety in cancer patients. Br J Cancer. 2000;83(10):1261-1267. doi: 10.1054/bjoc.2000.1405 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Yang HC, Brothers BM, Andersen BL. Stress and quality of life in breast cancer recurrence: moderation or mediation of coping? Ann Behav Med. 2008;35(2):188-197. doi: 10.1007/s12160-008-9016-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Frick E, Tyroller M, Panzer M. Anxiety, depression and quality of life of cancer patients undergoing radiation therapy: a cross-sectional study in a community hospital outpatient centre. Eur J Cancer Care (Engl). 2007;16(2):130-136. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2354.2006.00720.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bodurka-Bevers D, Basen-Engquist K, Carmack CL, et al. . Depression, anxiety, and quality of life in patients with epithelial ovarian cancer. Gynecol Oncol. 2000;78(3 Pt 1):302-308. doi: 10.1006/gyno.2000.5908 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Andersen BL, DeRubeis RJ, Berman BS, et al. ; American Society of Clinical Oncology . Screening, assessment, and care of anxiety and depressive symptoms in adults with cancer: an American Society of Clinical Oncology guideline adaptation. J Clin Oncol. 2014;32(15):1605-1619. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2013.52.4611 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.National Center for Complementary and Integrative Health Mind and body practices. Updated September 2017. Accessed March 6, 2019. https://www.nccih.nih.gov/health/mind-and-body-practices

- 13.Goleman D. The Meditative Mind: The Varieties of Meditative Experience. Jeremy P. Tarcher/Perigee Books; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Goyal M, Singh S, Sibinga EMS, et al. . Meditation programs for psychological stress and well-being: comparative effectiveness review No. 124. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality ; January 2014. Accessed June 26, 2020. https://www.effectivehealthcare.ahrq.gov/reports/final.cfm [PubMed]

- 15.Carlson LE, Speca M, Patel KD, Goodey E. Mindfulness-based stress reduction in relation to quality of life, mood, symptoms of stress, and immune parameters in breast and prostate cancer outpatients. Psychosom Med. 2003;65(4):571-581. doi: 10.1097/01.PSY.0000074003.35911.41 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hoffman CJ, Ersser SJ, Hopkinson JB, Nicholls PG, Harrington JE, Thomas PW. Effectiveness of mindfulness-based stress reduction in mood, breast- and endocrine-related quality of life, and well-being in stage 0 to III breast cancer: a randomized, controlled trial. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30(12):1335-1342. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2010.34.0331 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lee CE, Kim S, Kim S, Joo HM, Lee S. Effects of a mindfulness-based stress reduction program on the physical and psychological status and quality of life in patients with metastatic breast cancer. Holist Nurs Pract. 2017;31(4):260-269. doi: 10.1097/HNP.0000000000000220 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lengacher CA, Reich RR, Paterson CL, et al. . Examination of broad symptom improvement resulting from mindfulness-based stress reduction in breast cancer survivors: a randomized controlled trial. J Clin Oncol. 2016;34(24):2827-2834. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2015.65.7874 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zhang JY, Zhou YQ, Feng ZW, Fan YN, Zeng GC, Wei L. Randomized controlled trial of mindfulness-based stress reduction (MBSR) on posttraumatic growth of Chinese breast cancer survivors. Psychol Health Med. 2017;22(1):94-109. doi: 10.1080/13548506.2016.1146405 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Vaziri ZS, Mashhadi A, Shamloo ZS, Shahidsales S. Mindfulness-based cognitive therapy, cognitive emotion regulation and clinical symptoms in females with breast cancer. Iran J Psychiatry Behav Sci. 2017;11(4):e4158. doi: 10.17795/ijpbs-4158 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Compen F, Bisseling E, Schellekens M, et al. . Face-to-face and internet-based mindfulness-based cognitive therapy compared with treatment as usual in reducing psychological distress in patients with cancer: a multicenter randomized controlled trial. J Clin Oncol. 2018;36(23):2413-2421. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2017.76.5669 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zhang R, Yin J, Zhou Y. Effects of mindfulness-based psychological care on mood and sleep of leukemia patients in chemotherapy. Int J Nurs Sci. 2017;4(4):357-361. doi: 10.1016/j.ijnss.2017.07.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chambers S, Foley E, Clutton S, et al. . Mindfulness-based cognitive therapy for men with advanced prostate cancer: A randomised controlled trial. Psychooncology. 2016;25(suppl 3):8. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Haller H, Winkler MM, Klose P, Dobos G, Kümmel S, Cramer H. Mindfulness-based interventions for women with breast cancer: an updated systematic review and meta-analysis. Acta Oncol. 2017;56(12):1665-1676. doi: 10.1080/0284186X.2017.1342862 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Huang HP, He M, Wang HY, Zhou M. A meta-analysis of the benefits of mindfulness-based stress reduction (MBSR) on psychological function among breast cancer (BC) survivors. Breast Cancer. 2016;23(4):568-576. doi: 10.1007/s12282-015-0604-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zhang Q, Zhao H, Zheng Y. Effectiveness of mindfulness-based stress reduction (MBSR) on symptom variables and health-related quality of life in breast cancer patients—a systematic review and meta-analysis. Support Care Cancer. 2019;27(3):771-781. doi: 10.1007/s00520-018-4570-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Schell LK, Monsef I, Wöckel A, Skoetz N. Mindfulness-based stress reduction for women diagnosed with breast cancer. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2019;3:CD011518. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD011518.pub2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.McGowan J, Sampson M, Salzwedel DM, Cogo E, Foerster V, Lefebvre C. PRESS Peer Review of Electronic Search Strategies: 2015 guideline statement. J Clin Epidemiol. 2016;75:40-46. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2016.01.021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Higgins J, Thomas J, eds. Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions. The Cochrane Collaboration; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Higgins JP, Thompson SG. Quantifying heterogeneity in a meta-analysis. Stat Med. 2002;21(11):1539-1558. doi: 10.1002/sim.1186 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sterne JA, Egger M, Smith GD. Systematic reviews in health care: investigating and dealing with publication and other biases in meta-analysis. BMJ. 2001;323(7304):101-105. doi: 10.1136/bmj.323.7304.101 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Duval S, Tweedie R. Trim and fill: a simple funnel-plot-based method of testing and adjusting for publication bias in meta-analysis. Biometrics. 2000;56(2):455-463. doi: 10.1111/j.0006-341X.2000.00455.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Liu T, Zhang W, Xiao S, et al. . Mindfulness-based stress reduction in patients with differentiated thyroid cancer receiving radioactive iodine therapy: a randomized controlled trial. Cancer Manag Res. 2019;11:467-474. doi: 10.2147/CMAR.S183299 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Franco C, Amutio A, Mañas I, et al. . Improving psychosocial functioning in mastectomized women through a mindfulness-based program: flow meditation. Int J Stress Manag. 2019; Advance online publication. doi: 10.1037/str0000120 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lorca AM, Lorca MM, Criado JJ, et al. . Using mindfulness to reduce anxiety during PET/CT studies. Mindfulness. 2019;10:1163-1168. doi: 10.1007/s12671-018-1065-2 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Russell L, Ugalde A, Orellana L, et al. . A pilot randomised controlled trial of an online mindfulness-based program for people diagnosed with melanoma. Support Care Cancer. 2019;27(7):2735-2746. doi: 10.1007/s00520-018-4574-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Chambers SK, Occhipinti S, Foley E, et al. . Mindfulness-based cognitive therapy in advanced prostate cancer: a randomized controlled trial. J Clin Oncol. 2017;35(3):291-297. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2016.68.8788 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kenne Sarenmalm E, Mårtensson LB, Andersson BA, Karlsson P, Bergh I. Mindfulness and its efficacy for psychological and biological responses in women with breast cancer. Cancer Med. 2017;6(5):1108-1122. doi: 10.1002/cam4.1052 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Schellekens MPJ, van den Hurk DGM, Prins JB, et al. . Mindfulness-based stress reduction added to care as usual for lung cancer patients and/or their partners: A multicentre randomized controlled trial. Psychooncology. 2017;26(12):2118-2126. doi: 10.1002/pon.4430 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Blaes AH, Fenner D, Bachanova V, et al. . Mindfulness-based cancer recovery in survivors recovering from chemotherapy and radiation. J Community Support Oncol. 2016;14(8):351-358. doi: 10.12788/jcso.0244 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Jang SH, Kang SY, Lee HJ, Lee SY. Beneficial effect of mindfulness-based art therapy in patients with breast cancer—a randomized controlled trial. Explore (NY). 2016;12(5):333-340. doi: 10.1016/j.explore.2016.06.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Johannsen M, O’Connor M, O’Toole MS, Jensen AB, Højris I, Zachariae R. Efficacy of mindfulness-based cognitive therapy on late post-treatment pain in women treated for primary breast cancer: a randomized controlled Trial. J Clin Oncol. 2016;34(28):3390-3399. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2015.65.0770 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Bower JE, Crosswell AD, Stanton AL, et al. . Mindfulness meditation for younger breast cancer survivors: a randomized controlled trial. Cancer. 2015;121(8):1231-1240. doi: 10.1002/cncr.29194 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Johns SA, Brown LF, Beck-Coon K, Monahan PO, Tong Y, Kroenke K. Randomized controlled pilot study of mindfulness-based stress reduction for persistently fatigued cancer survivors. Psychooncology. 2015;24(8):885-893. doi: 10.1002/pon.3648 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kingston T, Collier S, Hevey D, et al. . Mindfulness-based cognitive therapy for psycho-oncology patients: an exploratory study. Ir J Psychol Med. 2015;32(3):265-274. doi: 10.1017/ipm.2014.81 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Zernicke KA, Campbell TS, Speca M, McCabe-Ruff K, Flowers S, Carlson LE. A randomized wait-list controlled trial of feasibility and efficacy of an online mindfulness-based cancer recovery program: the eTherapy for Cancer Applying Mindfulness Trial. Psychosom Med. 2014;76(4):257-267. doi: 10.1097/PSY.0000000000000053 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Würtzen H, Dalton SO, Elsass P, et al. . Mindfulness significantly reduces self-reported levels of anxiety and depression: results of a randomised controlled trial among 336 Danish women treated for stage I-III breast cancer. Eur J Cancer. 2013;49(6):1365-1373. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2012.10.030 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Henderson VP, Massion AO, Clemow L, Hurley TG, Druker S, Hébert JR. A randomized controlled trial of mindfulness-based stress reduction for women with early-stage breast cancer receiving radiotherapy. Integr Cancer Ther. 2013;12(5):404-413. doi: 10.1177/1534735412473640 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Lerman R, Jarski R, Rea H, Gellish R, Vicini F. Improving symptoms and quality of life of female cancer survivors: a randomized controlled study. Ann Surg Oncol. 2012;19(2):373-378. doi: 10.1245/s10434-011-2051-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Bränström R, Kvillemo P, Brandberg Y, Moskowitz JT. Self-report mindfulness as a mediator of psychological well-being in a stress reduction intervention for cancer patients—a randomized study. Ann Behav Med. 2010;39(2):151-161. doi: 10.1007/s12160-010-9168-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Foley E, Baillie A, Huxter M, Price M, Sinclair E. Mindfulness-based cognitive therapy for individuals whose lives have been affected by cancer: a randomized controlled trial. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2010;78(1):72-79. doi: 10.1037/a0017566 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Lengacher CA, Johnson-Mallard V, Post-White J, et al. . Randomized controlled trial of mindfulness-based stress reduction (MBSR) for survivors of breast cancer. Psychooncology. 2009;18(12):1261-1272. doi: 10.1002/pon.1529 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Monti DA, Peterson C, Kunkel EJ, et al. . A randomized, controlled trial of mindfulness-based art therapy (MBAT) for women with cancer. Psychooncology. 2006;15(5):363-373. doi: 10.1002/pon.988 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Speca M, Carlson LE, Goodey E, Angen M. A randomized, wait-list controlled clinical trial: the effect of a mindfulness meditation-based stress reduction program on mood and symptoms of stress in cancer outpatients. Psychosom Med. 2000;62(5):613-622. doi: 10.1097/00006842-200009000-00004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Piet J, Würtzen H, Zachariae R. The effect of mindfulness-based therapy on symptoms of anxiety and depression in adult cancer patients and survivors: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2012;80(6):1007-1020. doi: 10.1037/a0028329 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Cohen J. Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences. L. Erlbaum Associates; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Faraone SV. Interpreting estimates of treatment effects: implications for managed care. P T. 2008;33(12):700-711. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Puhan MA, Frey M, Büchi S, Schünemann HJ. The minimal important difference of the hospital anxiety and depression scale in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2008;6:46. doi: 10.1186/1477-7525-6-46 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Duijts SF, Faber MM, Oldenburg HS, van Beurden M, Aaronson NK. Effectiveness of behavioral techniques and physical exercise on psychosocial functioning and health-related quality of life in breast cancer patients and survivors--a meta-analysis. Psychooncology. 2011;20(2):115-126. doi: 10.1002/pon.1728 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Zimmaro LA, Carson JW, Olsen MK, Sanders LL, Keefe FJ, Porter LS. Greater mindfulness associated with lower pain, fatigue, and psychological distress in women with metastatic breast cancer. Psychooncology. 2020;29(2):263-270. doi: 10.1002/pon.5223 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Duong N, Davis H, Robinson PD, et al. . Mind and body practices for fatigue reduction in patients with cancer and hematopoietic stem cell transplant recipients: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol. 2017;120:210-216. doi: 10.1016/j.critrevonc.2017.11.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Chadi N, Weisbaum E, Vo DX, Ahola Kohut S. Mindfulness-based interventions for adolescents: time to consider telehealth. J Altern Complement Med. 2020;26(3):172-175. doi: 10.1089/acm.2019.0302 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Yousaf O, Grunfeld EA, Hunter MS. A systematic review of the factors associated with delays in medical and psychological help-seeking among men. Health Psychol Rev. 2015;9(2):264-276. doi: 10.1080/17437199.2013.840954 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

eTable 1. Search Strategy

eTable 2. Self-reported Anxiety Assessment Scales Used in the Included Trials (n = 28)

eTable 3. Self-reported Depression Assessment Scales Used in the Included Trials (n = 28)

eTable 4. Self-reported Health-related Quality of Life Assessment Scales Used in the Included Trials (n = 28)

eFigure 1. Summary of the Risk of Bias of Studies Included in the Systematic Review (n = 28)

eFigure 2. Funnel Plot “Trim-and-Fill” Technique Assessing Publication Bias for Short-term Reduction in Severity of Anxiety