Abstract

This study describes correlations between the dollar amount of relief funding authorized by the US Congress to fund prevention, diagnosis, and treatment of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) and to reimburse health care entities for lost revenues, and county-level Black population fraction accounting for county COVID-19 burden, comorbidity, and hospital financial health.

The Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security (CARES) Act and Paycheck Protection Program together designated $175 billion for coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) response efforts and reimbursement to health care entities for expenses or lost revenues.1

The most important factor driving funding allocation is past revenue. However, revenue is an imperfect measure of need because it is also influenced by prices, overuse, payer mix, and market consolidation.2 Moreover, non-White and indigent populations generate lower revenues, due to underinsurance and undertreatment,3,4 and hospitals caring for them may receive less relief despite confronting a greater burden of COVID-19.5

We examined how relief funding relates to the health and financial needs of US counties, focusing on disproportionately Black counties.

Methods

Relief funding is allocated according to a complex, nonlinear formula (combining revenue, location, uninsurance, and COVID-19 hospitalizations; see eTables 1 and 2 in the Supplement for details). We measured (1) how this allocation relates to the health and financial needs of counties, and (2) whether this allocation strategy was associated with differences in funding by county racial composition. Ideally, 2 counties receiving equal funding should have equal needs, irrespective of racial composition.

To measure needs, we used county-level data to form 3 categories: COVID-19 burden (cumulative deaths and cases and cumulative severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 case-to-test ratio as of June 28, 2020; non–COVID-19 deaths between February 1 and July 1, 2020), comorbidities exacerbating COVID-19 (hypertension, end-stage kidney disease, obesity, smoking, diabetes), and hospital financial health (mean operating margin, cash on hand, as estimated in prior research6). We summarized these categories with mean z scores (eg, for financial health: each hospital’s margin and cash were converted to z scores by subtracting means and dividing by standard deviations [SDs], then averaged across all hospitals in the county).

We then projected anticipated relief funding for Medicare-participating entities based on announced policies as of July 5, 2020 ($120 billion) by county. We modeled allocations to acute care hospitals, the largest category of health spending, using 2015 Cost Reports. We attributed hospital funding to counties by share of 2015 Medicare fee-for-service admissions, and assumed nonhospital entities (for whom revenue data were not available) were proportional.

We regressed measures of need on relief funding and calculated R2 to measure how needs varied with funding allocation. We repeated regressions with an indicator for counties with the largest Black population fraction (top quartile). We used Stata version 16.1 (StataCorp). Two-sided P < .05 defined statistical significance. This study was approved by the National Bureau of Economic Research Institutional Review Board.

Results

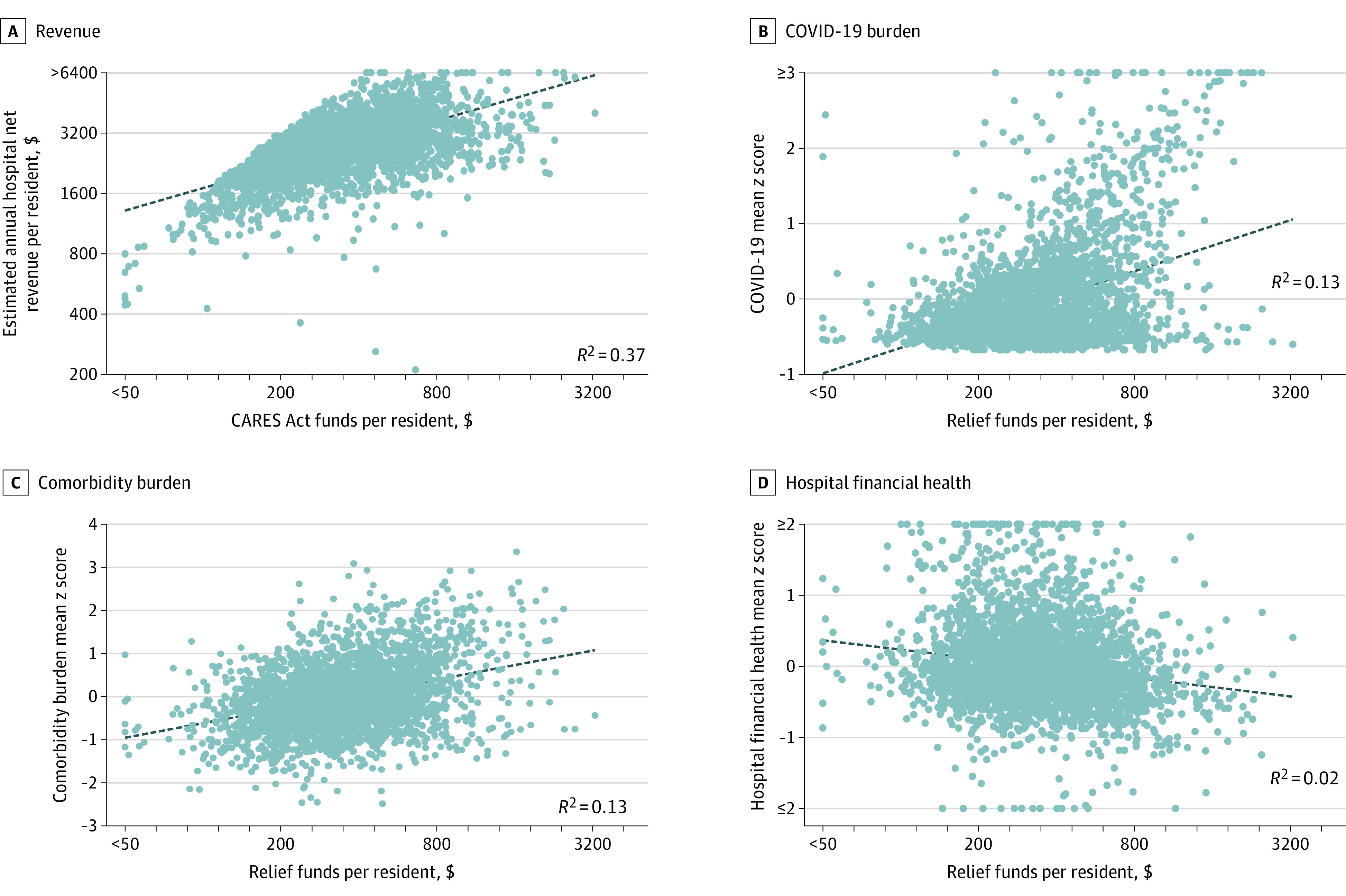

The Figure shows relief funding reflected hospital revenues (R2 = 0.37) more than COVID-19 burden (R2 = 0.13), comorbidities (R2 = 0.13), or hospital financial health (R2 = 0.02).

Figure. Correlation Between County Measures of Health and Financial Need and Relief Funding.

Net revenue per resident refers to the estimated annual net revenue across all hospitals. Z scores are calculated by subtracting the mean and dividing by the standard deviation for a given metric. The coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) mean z score is estimated as the mean of z scores for the following outcomes: cumulative COVID-19 deaths per 100 000, cumulative COVID-19 cases per 100 000, non–COVID-19 deaths per 100 000, and severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) case-to-test ratio. Higher COVID-19 mean z scores indicate higher burden of COVID-19 (higher COVID-19 cases, higher COVID-19 and non–COVID-19 deaths, higher positive SARS-CoV-2 case-to-test ratio). The mean comorbidity burden z score is the mean of the z scores among the following comorbidities, estimated using population-based data on prevalence: end-stage kidney disease, diabetes, hypertension, obesity, and smoking. Higher mean comorbidity z scores indicate poorer health. The mean hospital finance z score includes the following metrics: mean hospital operating margin and days of cash on hand across Medicare fee-for-service admissions within the county. Higher mean hospital finance z scores indicate better financial health. Best fit lines were fitted linearly for all panels. For each panel, more than 95% of counties are within the bounds of the axes. The remaining counties are top or bottom coded for scatterplot visualization only. The dots indicate counties and the dashed lines indicate the best fit line across all counties.

Across 3124 counties, mean (SD) relief funding per resident was $411 ($277). Disproportionately Black counties (29.6% Black, N = 781) received $126 more funding ($506 vs $380, P < .001) than other counties (2.3% Black, N = 2343). However, among counties receiving the same funding, disproportionately Black counties had higher COVID-19 burden (mean z score: +0.50 SD, P < .001), more comorbidities (+0.73 SD, P < .001), and worse hospital finances (–0.12 SD, P < .001) than other counties (Table). Differences in all individual metrics were also large and statistically significant, including more COVID-19 cases and deaths (+404.0 and +17.6 per 100 000, both P < .001), more non–COVID-19 deaths (+33.3 per 100 000, P < .001), lower operating margins (–0.90%, P = .02), and less cash on hand (–15.2 days, P = .001).

Table. Differences in County Health and Financial Needs by Race, Holding Relief Funding Constanta.

| No. | Overall mean across counties | Excess in top-quartile Black counties, holding funding constant (95% CI) | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Measures of health and financial need | ||||

| COVID-19 | ||||

| Burden (mean z score) | 3124 | 0 | 0.50 (0.44 to 0.55) | <.001 |

| Cases per 100 000 | 3124 | 484.7 | 404.0 (346.6 to 461.4) | <.001 |

| Deaths per 100 000 | 3124 | 16.9 | 17.6 (15.3 to 20.0) | <.001 |

| Non–COVID-19 deaths per 100 000 | 629 | 385.3 | 33.3 (9.22 to 57.4) | .007 |

| SARS-CoV-2 case-to-test ratio, % | 1504 | 6.45 | 3.14 (2.26 to 4.02) | .02 |

| Comorbidity burden (mean z score) | 3124 | 0 | 0.73 (0.68 to 0.79) | <.001 |

| Prevalence, % | ||||

| End-stage kidney disease | 2679 | 0.22 | 0.10 (0.09 to 0.11) | <.001 |

| Diabetes | 3124 | 12.1 | 2.25 (1.93 to 2.57) | <.001 |

| Hypertension | 3123 | 39.4 | 4.63 (4.40 to 4.86) | <.001 |

| Obesity | 3124 | 32.8 | 2.91 (2.48 to 3.34) | <.001 |

| Smoking | 3123 | 17.9 | 1.19 (0.91 to 1.47) | <.001 |

| Hospital financial health (mean z score) | 3124 | 0 | −0.12 (−0.18 to −0.06) | <.001 |

| Operating margin, % | 3124 | 4.97 | −0.90 (−1.64 to −0.15) | .02 |

| Cash on hand, d | 3124 | 133.3 | −15.2 (−23.9 to −6.41) | .001 |

Abbreviations: COVID-19, coronavirus disease 2019; SARS-CoV-2, severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2.

Further details on data sources are provided in eTables 1 and 2 in the Supplement. Data on COVID-19 deaths and cases and SARS-CoV-2 tests are cumulative, recorded on June 28, 2020. Data on non–COVID-19 deaths per 100 000 are recorded from February 1 to July 1, 2020.

Discussion

Tying relief funding to revenue resulted in allocations largely unrelated to health or financial needs. It also meant disproportionately Black communities receiving the same level of relief funding as other counties had greater health and financial needs. Although race may co-vary with socioeconomic status or education, it is unique in having special protections under the law. The findings suggest the relief funding allocation may have a “disparate impact” on Black populations, a legal concept referring to policies that negatively affect a protected group, even if they do not explicitly use information about that group.

Study limitations include that it relied primarily on estimated rather than actual disbursement, which may vary with changes in policy or COVID-19 burden, and that nonhospital revenues were not available.

Policy makers should consider aligning funding with measures of need rather than revenue, which would increase both equity and economic efficiency.

Section Editor: Jody W. Zylke, MD, Deputy Editor.

eTable 1. Sources for Estimates of Health and Financial Need

eTable 2. Method to Estimate Funding Allocation for Medicare-Participating Entities

References

- 1.Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security (CARES) Act, Pub L No. 116-136.

- 2.Schwartz K, Damico A Distribution of CARES Act funding among providers. Kaiser Family Foundation. Published May 13, 2020. Accessed July 5, 2020. https://www.kff.org/coronavirus-covid-19/issue-brief/distribution-of-cares-act-funding-among-hospitals/

- 3.Institute of Medicine Unequal Treatment: Confronting Racial and Ethnic Disparities in Health Care. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2003. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lillie-Blanton M, Hoffman C. The role of health insurance coverage in reducing racial/ethnic disparities in health care. Health Aff (Millwood). 2005;24(2):398-408. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.24.2.398 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dowling MK, Kelly RL. Policy solutions for reversing the color-blind public health response to COVID-19 in the US. JAMA. 2020;324(3):229-230. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.10531 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Khullar D, Bond AM, Schpero WL. COVID-19 and the financial health of US hospitals. JAMA. 2020;323(21):2127-2128. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.6269 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

eTable 1. Sources for Estimates of Health and Financial Need

eTable 2. Method to Estimate Funding Allocation for Medicare-Participating Entities