Abstract

This study investigated the effect of prostaglandin E1 (PGE-1) treatment on the biochemical and histopathological changes in a model of nephropathy that was induced using renal microembolism in rats. Wistar rats were assigned to three groups: a control group (C, normal), a renal microembolism (RM) group, and a renal microembolism treated with PGE-1 (RM + PGE-1) group. The renal microembolism was induced by an arterial injection of polymethylmethacrylate microbeads into the remaining kidney of nephrectomized rats. Intramuscular treatment with PGE-1 was initiated on the day of the induction of the renal microembolism and continued once weekly for up to 60 days. At the end of the treatment period, blood samples were taken to assess the serum creatinine and urea concentrations, and 24-h urine samples were collected to determine the total protein levels. The rats’ kidneys were removed and processed for histopathological analysis using the hematoxylin and eosin, periodic acid-Schiff, Mallory-Azan, and Picro-Sirius techniques. An immunohistochemical assay with vascular endothelial growth factor receptor-2 (anti-VEGFR-2) was also performed. The results showed that the PGE-1 treatment prevented vascular, glomerular, tubular, and interstitial alterations and reduced the biochemical changes, thus improving the renal function in rats that were subjected to renal microembolism. These effects could be partially attributable to an increase in the PGE-1-induced angiogenesis, because we observed an increase in the tissue expression of VEGFR-2, a specific marker of angiogenesis.

Keywords: Prostaglandin E1, renal microembolism, angiogenesis, kidneys

Introduction

Renal atheroembolism (RA) results from the displacement of large artery plaques that may result in chronic kidney disease through the obstruction of renal arterioles and glomerular capillaries that are associated with local inflammation and the development of fibrosis [1,2]. The incidence of this manifestation of renal disease has increased over the years as the population has aged and with the advent of new diagnosis and treatment modalities for patients with atherosclerotic disease [1,3]. Additionally, other risk factors, such as male sex, smoking, dyslipidemia, diabetes mellitus, and the presence of other cardiovascular diseases (e.g., stroke and abdominal aortic aneurysm), are more frequent in these patients [4].

Renal atheroembolism is a condition that impairs long-term renal function and patient survival [2]. Atheroembolic renal disease was previously only diagnosed post mortem. However, in the last two decades, the disease has been recognized as a clinical syndrome and is now thought to be a recognizable cause of kidney disease, with a diagnosis before death in most cases [5]. To date, no specific therapy for atheroembolic renal disease is available, and the treatment is mainly symptomatic and supportive. Some studies report the benefit of therapies that comprise corticosteroid, statins, and acetylsalicylic acid [2,6-8], with indications of renal replacement therapy (dialysis) in cases in which renal impairment is aggravated [5,8].

Both experimental and clinical studies are extremely important for elucidating the pathophysiological mechanisms that are involved in the development and maintenance of the disease, with a focus on more effective therapeutic alternatives. In a preliminary study we showed that severe vascular abnormalities and glomerular, tubular, and interstitial abnormalities in rat renal tissue, with the consequent impairment of renal function, occur in a model of microembolism-induced nephropathy [9]. These changes were observed to be strong 60 days after the induction of microembolism-induced chronic kidney disease. Moreover, an important finding from this model is the reduction of angiogenesis that is induced by renal microembolism, which can be considered a trigger for the progression of microembolism-induced nephropathy. Thus, one possibility is that treatment with an angiogenic drug may be beneficial for preventing some of the observed changes and consequently the progression of the disease.

Prostaglandin has been tested in this regard because it is a substance that is used to promote therapeutic angiogenesis [10,11]. Studies that have employed different experimental models of ischemia report that prostaglandins increase angiogenesis [3,12-15] and also exert several biological effects, including maintaining renal blood flow and the glomerular filtration rate [16-18].

The present study evaluated the effects of the prostaglandin E1 (PGE-1) on the biochemical and histopathological alterations in an experimental model of microembolism-induced nephropathy.

Materials and methods

Experimental design

The experimental protocol was approved by the Ethics Committee on the Use of Animals of the State University of Maringá (CEUA 1994250515). Male Wistar rats, 110-120 days old and initially weighing 350-400 g, were housed at a temperature of 22°C ± 2°C under a 12 h/12 h light/dark cycle with free access to food and water. After a 7-day adaptation period, the animals were divided into the following groups (n = 5/group): control (C; normal animals), renal microembolism (RM; nephrectomized animals that were subjected to renal microembolism), and renal microembolism treated with PGE-1 (RM + PGE-1; nephrectomized animals that were subjected to renal microembolism and treated with PGE-1). Treatment with PGE-1 (5.0 μg/kg, i.m.) was started on the day of the induction of the renal microembolism and continued once weekly for up to 60 days. The PGE-1 (Prostavasin®) that was used in the present study was commercially obtained from Biosintética Farmacêutica Ltda. (São Paulo, Brazil). The dose of PGE-1 that was used in this study was based on Moreschi et al. [15].

Induction of renal microembolism

The animals were anesthetized with thiopental (45 mg/kg, i.p.) and placed in the dorsal decubitus position on a dissection board, which was heated by artificial lighting. Iodinated alcohol was applied for antisepsis. A paramedian incision of the skin and peritoneum was then performed. The celiac, mesenteric, contralateral renal, and distal regions of the aorta were clamped to ensure blood flow only in the left renal artery. In the region anterior to the left renal artery ostium, a 0.2 ml suspension of microbeads (0.8 mg, 20-27 μm diameter, poly-methyl methacrylate, Cospheric, Santa Barbara, CA, USA) in physiological saline was administered. After administration of the suspension, the arterial clamps were maintained for 15 s, and the clamps on the aortic puncture site were maintained for 2 min to avoid bleeding. The right kidney was then removed to guarantee the uniform distribution of particles in the remaining left kidney (9). After suturing the peritoneum and abdominal wall, the animals were placed in appropriate boxes and maintained under the same conditions as described above. The animals were then monitored according to the established protocol sixty days after renal microembolism induction, the rats were kept in metabolic cages for 24 h for urine collection. Additionally, after a 12-h fast, the rats were anesthetized to collect blood from the abdominal aorta. Blood samples were centrifuged 1000 g, and their serum was separated to assess their creatinine and urea concentrations. The rats were then euthanized under deep anesthesia (isoflurane 5% + CO2). After euthanasia, the kidneys were removed, weighed, fixed in 10% formaldehyde for 24 h, and prepared for histological processing.

Determination of the serum creatinine and urea concentrations and the total protein levels in 24-h urine

The serum creatinine and urea concentrations and the 24-h urine protein levels were determined using a Siemens kit. The analyses were performed using chemiluminescent assays and Siemens Immulite 2000 automated equipment. The results are expressed as mg/dl.

Histopathological analyses of the renal tissue

After the histological processing, sets of semi-serial 5 μm cross sections were prepared. The following staining techniques were used: hematoxylin and eosin (HE), periodic acid-Schiff (PAS), Mallory-Azan, and Picro-Sirius. The hematoxylin/eosin-stained sections were used for morphometric and histopathological analyses to detect possible changes in Bowman’s space, the renal corpuscle, the renal interstitium, and the renal tubules using score-based rankings [19-22]. These sections were also used to determine the area of congestion within 2 mm2 of the cortical region of the kidney. The sections that were stained with PAS were used to measure the area that was occupied by the basal membrane. The sections that were stained with Mallory-Azan and Picro-Sirius were used to identify the total collagen deposits and the type I and type III collagens, respectively. For the morphometric analysis of the kidneys, random images of each slide/animal were captured with a 20× objective using an Olympus BX41 optical microscope (Olympus, Tokyo, Japan). The ImagePro Plus 4.5 image analysis system (Media Cybernetics) was used for all of the morphometric analyses. The results are expressed as the mean area (μm2) ± standard error of the mean.

Immunohistochemistry for the vascular endothelial growth factor receptor

The immunohistochemical technique was used to detect the angiogenesis (anti-vascular endothelial growth factor receptor-2 [VEGFR-2] antibody, catalog no. ab2349, Abcam, Cambridge, MA, USA). After deparaffinization, the sections were hydrated and incubated in a sodium citrate buffer solution and Tween-20 at a high temperature for 20 min for the antigen retrieval. After cooling, the sections were incubated in 10% hydrogen peroxide for 20 min to block the endogenous peroxidase activity, washed with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS; 0.1 M, pH 7.4), and re-incubated with 2% bovine serum albumin in PBS for 10 min to block nonspecific binding sites. The sections were incubated overnight at room temperature with a primary antibody (anti-VEGFR-2) at a concentration of 1:200 diluted in PBS. The sections were then washed with PBS and incubated for 90 min at room temperature with a secondary antibody (mouse anti-rabbit IgG-B, 1:200, Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Dallas, TX, USA). The sections were then washed with PBS and incubated with the Vectastain ABC kit (Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA, USA) for 30 min at room temperature for the secondary antibody binding. The sections were then washed again with PBS and incubated for 30 min at room temperature with the ImPACT AEC kit (Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA, USA) for revelation while being protected from light. The reaction was quenched with distilled water. The sections were then counterstained with Mayer’s hematoxylin and mounted in an aqueous medium (VectaMount AQ, Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA, USA). Random images of each slide/animal were captured using an Olympus BX41 optical microscope (Olympus, Tokyo, Japan) with a 20× objective. The slides were analyzed using ImagePro Plus 4.5 image analysis software (Media Cybernetics) to detect the immunoreactivity.

Statistical analysis

The results are expressed as the mean ± standard error of the mean (SEM). The statistical analysis was performed using Prism GraphPad (GraphPad Software, Inc., USA, 5.00) for comparisons between groups. Values of P < 0.05 were considered statistically significant. One-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) followed by Tukey’s post hoc was used for the analysis of data with a normal distribution (parameters biochemical, kidney weight, quantitative histopathological analysis and immunohistochemical data). The qualitative assessment of the histopathological data was analyzed using a Kruskal-Wallis non-parametric test followed by Dunn’s test.

Results

PGE-1 treatment improved renal function in rats that were subjected to microembolism-induced nephropathy

Table 1 shows the serum creatinine and urea concentrations and the 24-h urine protein levels 60 days after the surgical procedure. All of these biomarkers of renal function were significantly increased (all P < 0.05) in the RM group compared with the C group. The treatment with PGE-1 (RM + PGE-1 group) reduced the serum creatinine (18.3%) and urea (21.8%) concentrations and the 24-h urine protein levels (38.4%).

Table 1.

Serum concentrations of creatinine and urea, urine protein concentration (expressed as mg/dl), and remnant kidney weight (expressed as a percentage/100 g body weight of rats) in the control (C), renal microembolism (RM), and renal microembolism treated with PGE-1 (RM + PGE-1) groups at 60 days after the renal microembolism induction

| Experimental Groups | Parameters | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||

| creatinine (mg/dl) | urea (mg/dl) | 24-h urine protein (mg/dl) | kidney weight (mg/100 g) | |

| C | 0.31 ± 0.01 | 37.0 ± 1.1 | 94.3 ± 9.6 | 310 ± 10.1 |

| RM | 0.51 ± 0.03a | 53.8 ± 2.4a | 138.1 ± 8.2a | 400 ± 8.1a |

| RM + PGE-1 | 0.40 ± 0.02a,b | 42.0 ± 1.3b | 85.0 ± 8.5b | 400 ± 6.8a |

The data are expressed as the mean ± SEM of five animals per group.

P < 0.05, compared with the C group;

P < 0.05, compared with the RM group (one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s post hoc test).

PGE-1 treatment prevented the histopathological changes in rats that were subjected to microembolism-induced nephropathy

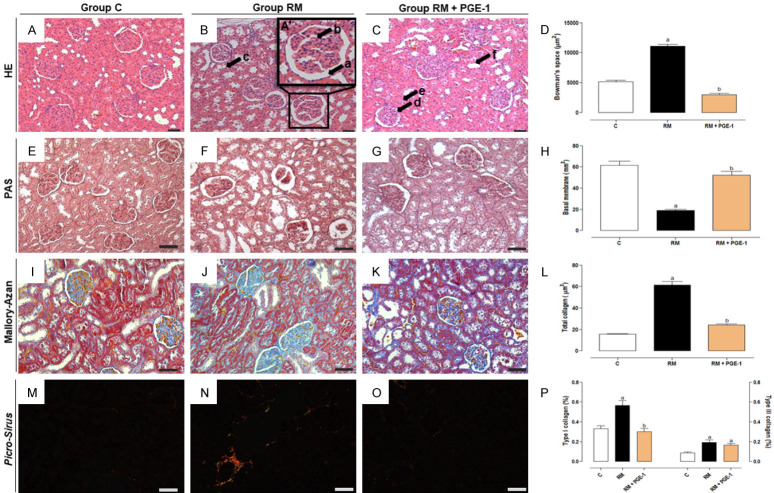

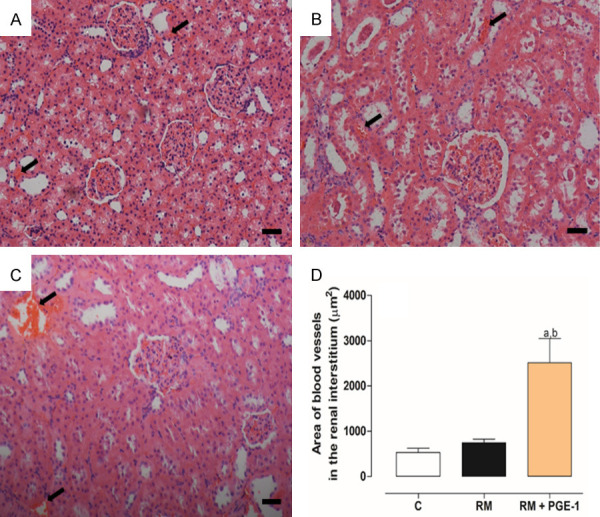

Figure 1 and Table 2 show the histopathological evaluations of the renal tissue in the different groups of rats. The histological analysis of the renal tissue by HE staining in the C group showed no abnormalities, presenting a preserved and intact renal architecture. In contrast, intense glomerular, tubular, and interstitial changes were observed in the RM group, which were significantly different (P < 0.05) from the C group. The treatment with PGE-1 (RM + PGE-1 group) significantly prevented these changes (P < 0.05; Table 2). The morphometry of the renal tissue showed significant changes in the RM group. A significant increase in Bowman’s space was observed compared with the C group (P < 0.05; Figure 1A-C). A significant decrease in the basal membrane of the kidney was observed in the RM group compared with the C group (P < 0.05; Figure 1D-F). In the RM + PGE-1 group, the Bowman’s space and the basal membrane were similar to the C group (Figure 1A-F). Significant increases in total collagen (Figure 1G-I), type I collagen, and type III collagen (Figure 1J-L) were observed in the RM group compared with the C group (all P < 0.05). Treatment with PGE-1 (RM + PGE-1 group) significantly reduced total collagen (Figure 1G-I) and type I collagen deposition (both P < 0.05) but did not modify the deposition of type III collagen, which was similar to the RM group (Figure 1J-L). Interestingly, morphological and morphometric evaluations by HE staining also indicated an extensive congested area in the renal interstitium in the RM + PGE-1 group compared with the RM group (Figure 3).

Figure 1.

Photomicrographs of the histopathological and morphometric changes in Bowman’s space (A-D - in μm2), basal membrane (E-H - in μm2), total collagen deposition (I-L - in μm2), type I and III collagen deposition (M-P - as a percentage), in the renal tissue of the control (C), renal microembolism (RM), and renal microembolism treated with PGE-1 (RM + PGE-1) groups at 60 days after the renal microembolism induction. The renal sections were stained using the hematoxylin and eosin, periodic acid-Schiff, Mallory-Azan trichrome, and Picro-Sirius techniques. Black arrows indicate: (A) dilatation of Bowman’s space, (B) dilatation of the capillary loops, (C) tubular degeneration, (D-F) indicate intact glomerule and proximal and distal tubules. 200× magnification. Each value represents the mean ± SEM of five animals per group. a P < 0.05, compared with the C group; b P < 0.05, compared with the RM group (one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s post hoc test).

Table 2.

Qualitative scoring assessment of the histopathological findings in renal tissue stained using the hematoxylin and eosin (HE) technique in the control (C), renal microembolism (RM), and renal microembolism treated with PGE-1 (RM + PGE-1) groups at 60 days after the renal microembolism induction

| Experimental Groups | Kidney changes | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||

| Corpuscle | Tubules | Interstitium | |||

|

|

|

|

|||

| Bowman’s space | Capillary loops | Cellularity | Cellular degeneration and necrosis | Inflammatory cells | |

| C | 0.00 ± 0.0 | 0.47 ± 0.2 | 0.00 ± 0.0 | 0.34 ± 0.2 | 0.10 ± 0.2 |

| RM | 2.30 ± 0.2a | 2.87 ± 0.2a | 2.51 ± 0.9a | 2.33 ± 0.3a | 2.41 ± 0.4a |

| RM + PGE-1 | 0.58 ± 0.1b | 0.64 ± 0.2b | 0.36 ± 0.1b | 0.50 ± 0.1b | 1.02 ± 0.3b |

The scores were assigned as follows: 0 (integral renal tissue), 1 (mild changes), 2 (moderate changes), and 3 (severe changes). The results are expressed as the mean ± SEM of five animals per group.

P < 0.05, compared with the C group;

P < 0.05, compared with the RM group (Kruskal-Wallis test followed by Dunn’s test).

Figure 3.

Representative photomicrographs of the renal tissue of the control - C (A), renal microembolism - RM (B), and renal microembolism treated with PGE-1 - RM + PGE-1 (C) groups, at 60 days after the renal microembolism induction. (D) Quantitative analysis of the congested area (in μm2) to an extension of 2 mm2 of the cortical region in the renal tissue. The black arrows indicate a congested area. Each value represents the mean ± SEM of five animals per group. a P < 0.05, compared with the C group; b P < 0.05, compared with the RM group (one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s post hoc test). 200× magnification.

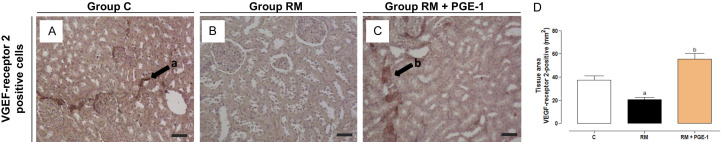

PGE-1 treatment promoted angiogenesis in rats that were subjected to microembolism-induced nephropathy

The immunostaining for VEGFR-2 revealed a significant decrease in VEGFR-positive cells in renal tissue in the RM group compared with the C group (P < 0.05). Treatment with PGE-1 caused an increase in the tissue expression of the vascular endothelial growth factor receptor-2, with a significant difference between the RM + PGE-1 group and the RM group (P < 0.05; Figure 2A-D).

Figure 2.

Representative photomicrographs and quantification of the number of VEGF receptor 2-positive cells (in μm2), in the renal tissue of the control (C), renal microembolism (RM), and renal microembolism treated with PGE-1 (RM + PGE-1) groups, at 60 days after the renal microembolism induction (A-D). Each value represents the mean ± SEM of five animals per group. a P < 0.05, compared with the C group; b P < 0.05, compared with the RM group (one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s post hoc test). 200× magnification.

Discussion

The present study investigated the effects of PGE-1 on the biochemical and histopathological changes in a model of nephropathy that was induced by renal microembolism in rats.

The injection of polymethylmethacrylate microbeads into the renal artery in unilaterally nephrectomized rats may mimic the clinical condition of chronic atheroembolic renal disease [9]. In the 60-day period, marked glomerular alterations (e.g., the dilatation of Bowman’s space and capillary loops and a decrease in cellularity), a reduction of the basal membrane area, tubular degeneration and necrosis, an intense interstitial inflammatory process, and large collagen deposition in renal tissue were observed. PGE-1, which was administered once weekly for up to 60 days, prevented glomerular and tubular changes in the basal membrane and renal interstitium, leading to an improvement in renal function, reflected by reductions of serum creatinine and urea concentrations and 24-h urine protein levels.

Sun et al. [23] used a distinct model of experimental nephropathy and found that PGE-1 treatment reduced serum creatinine concentrations and 24-h urine protein levels. This effect of PGE-1 can be at least partially explained by the preservation of endothelial cells, thus avoiding their rupture and consequent increase in permeability [23]. Similar observations were also reported in studies that used other models of renal injury [18,24,25].

Another important finding in the present study was the reduction of collagen deposition in PGE-1-treated rats, suggesting an antifibrogenic effect of PGE-1. Cai et al. [26] showed that PGE-1 treatment reduced the blood concentrations and tissue expression of profibrogenic factors, such as transforming growth factor-β. Luo et al. [27] reported that the absence of microsomal prostaglandin E synthase-1 expression, a precursor of prostaglandin, enhanced the expressions of the fibrogenic factors. These authors also found that the interaction between PGE-2 and the EP4 receptor inhibited the increase in type I collagen and fibronectin. Thus, one possible explanation for the present findings may be that treatment with PGE-1 was antifibrogenic, similar to PGE-2, because both PGE-1 and PGE-2 have actions on the same receptors [28,29]. Importantly, the alterations that were observed in this experimental model of renal microembolism-induced chronic kidney disease may also be related to impairments in microvasculature, in which a decrease in VEGFR-positive cells was observed [9]. In the present study, these results were replicated within the time period of 60 days.

Morphological and morphometric analysis using HE staining revealed that PGE-1 treatment significantly induced congested areas in the renal interstitium in animals that were subjected to renal microembolism-induced nephropathy. Interestingly, the immunohistochemical analysis revealed that this increase in vascularization could be attributable to the formation of new vessels, in which an increase in the tissue expression of VEGFR-2 (i.e., a specific marker of angiogenesis [23,30]) was observed.

According to some studies, VEGF promotes the proliferation and differentiation of endothelial cells, in addition to preventing the apoptosis of these cells [23,31]. Thus, this action could preserve renal blood flow and consequently inhibit cascades of pathophysiological events that culminate in the observed changes. The mechanism by which PGE-1 increases VEGFR-2 expression may be related to interactions between the PGE-1 and EP2 and EP4 receptors [23,32]. To our knowledge, this is the first study to evaluate the effect of PGE-1 treatment in an experimental model of microembolism-induced nephropathy in rats.

Altogether, the present data showed that the PGE-1 treatment prevented vascular, glomerular, tubular, and interstitial changes and improved renal function in a rat model of microembolism-induced nephropathy. These beneficial effects may be at least partially attributable to a PGE-1-induced increase in angiogenesis.

Our findings suggest that PGE-1 treatment could be a promising strategy for preventing atheroembolisms caused by surgical, vascular, or radiological procedures or after thrombolytic or anticoagulant therapy in high-risk patients.

Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful for the technical assistance of Jailson Araujo Dantas. This study was supported by grants from CNPq (Conselho Nacional de Desenvolvimento Científico e Tecnológico), and FA (Fundação Araucária-PR), Brazil.

Disclosure of conflict of interest

None.

References

- 1.Granata A, Insalaco M, Di Pietro F, Di Rosa S, Romano G, Scuderi R. Atheroembolism renal disease: diagnosis and etiologic factors. Clin Ter. 2012;163:313–322. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Scolari F, Ravani P. Atheroembolic renal disease. Lancet. 2010;375:1650–1660. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)62073-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chronopoulos A, Rosner MH, Cruz DN, Ronco C. Acute kidney injury in the elderly: a review. Contrib Nephrol. 2010;165:315–321. doi: 10.1159/000313772. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gutiérrez Solís E, Morales E, Rodríguez Jornet A, Andreu FJ, Rivera F, Vozmediano C, Gutiérrez E, Igarzábal A, Enguita AB, Praga M. Atheroembolic renal disease: analysis of clinical and therapeutic factors that influence its progression. Nefrologia. 2010;30:317–323. doi: 10.3265/Nefrologia.pre2010.Apr.10367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hachem GE, Nabbout RA. Atheroembolic renal disease: a beneficial effect of steroids. J Nephrol Ther. 2016;6:276. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mittal BV, Alexander MP, Rennke HG, Singh AK. Atheroembolic renal disease: a silent masquerader. Kidney Int. 2008;73:126–130. doi: 10.1038/sj.ki.5002433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tokatli A, Tatli E, Aksoyb M, Cakar MA. Cholesterol embolization syndrome after primary percutaneous coronary intervention in patient with acute anterior myocardial infarction. Int J Cardiovas Acad. 2016;2:62–64. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Vaidya PN, Finnigan NA. StatPearls [Internet] Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2020. Atheroembolic Kidney Disease. [Updated 2020 Apr 23] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bersani-Amado LE, da Rocha BA, Schneider LCL, Ames FQ, Breithaupt Faloppa AC, Araújo GB, Dantas JA, Bersani-Amado CA, Cuman RKN. Nephropathy induced by renal microembolism: a characterization of biochemical and histopathological changes in rats. Int J Clin Exp Pathol. 2019;12:2311–2323. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Clover AJ, McCarthy MJ. Developing strategies for therapeutic angiogenesis: vascular endothelial growth factor alone may not be answer. Br J Plast Surg. 2003;56:314. doi: 10.1016/s0007-1226(03)00230-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mehrabi MR, Ekmekcioglu C, Stanek B, Thalhammer T, Tamadoon F, Pacher R, Steiner GE, Wild T, Grimm M, Spieckermann PG, Mall G, Glogar HD. Angiogenesis stimulation in explanted hearts from patients pré-treated with intravenous prostaglandin E(1) J Heart Lung Transplant. 2001;20:465–473. doi: 10.1016/s1053-2498(00)00317-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mehrabi MR, Serbecic N, Tamaddon F, Pacher R, Horvath R, Mall G, Glogar HD. Clinical benefit of prostaglandin E1-treatment of patients with ischemic heart disease: stimulation of therapeutic angiogenesis in vital and infarcted myocardium. Biomed Pharmacother. 2003;57:173–178. doi: 10.1016/s0753-3322(03)00026-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Haider DG, Bucek RA, Giurgea AG, Maurer G, Glogar H, Minar E, Wolzt M, Mehrabi MR, Baghestanian M. PGE (1) analog alprostadil induces VEGF and eNOS expression in endothelial cells. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2005;289:2066–2072. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00147.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hajime I, Aihara M, Tomioka M, Watabe Y. Specific enhancement of vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) production in ischemic region by alprostadil - potential therapeutic application in pharmaceutical regenerative medicine. J Pharm Sci. 2013;122:158–161. doi: 10.1254/jphs.13033sc. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Moreschi D Jr, Fagundes DJ, Bersani-Amado LE, Hernandes L, Moreschi HK. Efeitos da prostaglandina E1 (PGE1) na gênese de capilares sanguíneos em músculo esquelético isquêmico de ratos: estudo histológico. J Vasc Bras. 2007;6:316–324. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Watkins MT, Al-Badawi H, Russo AL, Soler H, Peterson BM, Patton G. Human microvascular endothelial cell prostaglandin E1 synthesis during in vitro ischemia-reperfusion. J Cell Biochem. 2004;92:472–480. doi: 10.1002/jcb.20077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dołegowska B, Pikuła E, Safranow K, Olszewska M, Jakubowska K, Chlubek D, Gutowski P. Metabolism of eicosanoids and their action on renal function during ischaemia and reperfusion: the effect of alprostadil. Prostaglandins Leukot Essent Fatty Acids. 2006;75:403–411. doi: 10.1016/j.plefa.2006.07.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Soares BL, Freitas MA, Montero EF, Pitta GB, Miranda F Jr. Alprostadil attenuates inflammatory aspects and leucocytes adhesion on renal ischemia and reperfusion injury in rats. Acta Cir Bras. 2014;29(Suppl 2):55–60. doi: 10.1590/s0102-8650201400140011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Parlakpinar H, Acet A, Gul M, Altinoz E, Esrefoglu M, Colak C. Protective effects of melatonin on renal failure in pinealectomized rats. Int J Urol. 2007;14:743–748. doi: 10.1111/j.1442-2042.2007.01806.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kiris I, Kapan S, Kilbas A, Yilmaz N, Altuntas I, Karahan N, Okutan H. The protective effect of erythropoietin on renal injury induced by abdominal aortic-ischemia-reperfusion in rats. J Surg Res. 2008;149:206–213. doi: 10.1016/j.jss.2007.12.752. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Oruc O, Inci K, Aki FT, Zeybek D, Muftuoglu SF, Kilinc K, Ergen A. Sildenafil attenuates renal ischemia reperfusion injury by decreasing leukocyte infiltration. Acta Histochem. 2010;112:337–344. doi: 10.1016/j.acthis.2009.02.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Goudarzi M, Khodayar MJ, Hosseini Tabatabaei SMT, Ghaznavi H, Fatemi I, Mehrzadi S. Pretreatment with melatonin protects against cyclophosphamide-induced oxidative stress and renal damage in mice. Fundam Clin Pharmacol. 2017;31:625–635. doi: 10.1111/fcp.12303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sun D, Liu CX, Ma YY, Zhang L. Protective effect of prostaglandin E1 on renal miicrovascular injury in rats of acute aristolochic acid nephropathy. Ren Fail. 2011;33:225–232. doi: 10.3109/0886022X.2010.541586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Meurer M, Ebert K, Schweda F, Hocherl K. The renal vasodilatory effect of prostaglandins is ameliorated in isolated-perfused kidneys of endotoxemic mice. Pflugers Arch. 2018;470:1691–1703. doi: 10.1007/s00424-018-2183-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mahmoud IM, Hussein Ael-A, Sarhan ME, Awad AA, El Desoky I. Role of combined L-arginine and prostaglandin E1 in renal ischemia-reperfusion injury. Nephron Physiol. 2007;105:57–65. doi: 10.1159/000100425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cai WY, Gu YY, Li AM, Cui HQ, Yao Y. Effect of alprostadil combined with Diammonium glycyrrhizinate on renal interstial fibrosis in SD rats. Asian Pac J Trop Med. 2014;7:900–904. doi: 10.1016/S1995-7645(14)60157-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Luo R, Kakizoe Y, Wang F, Fan X, Hu S, Yang T, Wang W, Li C. Deficiency of mPGES-1 exacerbates renal fibrosis and inflammation in mice with unilateral ureteral obstruction. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2017;312:121–133. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00231.2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kambe T, Maruyama T, Naganawa A, Asada M, Seki A, Maruyama T, Nakai H, Toda M. Discovery of an 8-aza-5-thiaProstaglandin E1 analog as a highly selective EP4 receptor agonist. Chem Pharm Bull (Tokyo) 2011;59:1494–1508. doi: 10.1248/cpb.59.1494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Li F, He B, Ma X, Yu S, Roy R, Lentz SR, Tan K, Guzman ML, Zhao C, Xue HH. Prostaglandin E1 and its analog misoprostol inhibit human CML stem cell self-renewal via EP4 receptor activation and repression of AP-1. Cell Stem Cell. 2017;21:359–373. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2017.08.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Shibuya M. Vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF)-Receptor2: its biological functions, major signaling pathway, and specific ligand VEGF-E. Endothelium. 2006;13:63–69. doi: 10.1080/10623320600697955. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ferrara N, Gerber HP. The role of vascular endothelial growth factor in angiogenesis. Acta Haematol. 2001;106:148–156. doi: 10.1159/000046610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hori R, Nakagawa T, Yamamoto N, Hamaguchi K, Ito J. Role of prostaglandin E receptor subtypes EP2 and EP4 in autocrine and paracrine functions of vascular endothelial growth factor in the inner ear. BMC Neurosci. 2010;11:35. doi: 10.1186/1471-2202-11-35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]