Abstract

Objective:

The TURKMI registry is designed to provide insight into the characteristics, management from symptom onset to hospital discharge, and outcome of patients with acute myocardial infarction (MI) in Turkey. We report the baseline and clinical characteristics of the TURKMI population.

Methods:

The TURKMI study is a nation-wide registry that was conducted in 50 centers capable of percutaneous coronary intervention selected from each EuroStat NUTS region in Turkey according to population sampling weight, prioritized by the number of hospitals in each region. All consecutive patients with acute MI admitted to coronary care units within 48 hours of symptom onset were prospectively enrolled during a predefined 2-week period between November 1, 2018 and November 16, 2018.

Results:

A total of 1930 consecutive patients (mean age, 62.0±13.2 years; 26.1% female) with a diagnosis of acute MI were prospectively enrolled. More than half of the patients were diagnosed with non-ST elevation MI (61.9%), and 38.1% were diagnosed with ST elevation MI. Coronary angiography was performed in 93.7% and, percutaneous coronary intervention was performed in 73.2% of the study population. Fibrinolytic therapy was administered to 13 patients (0.018%). Aspirin was prescribed in 99.3% of the patients, and 94% were on dual antiplatelet therapy at the time of discharge. Beta blockers were prescribed in 85.0%, anti-lipid drugs in 96.3%, angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitors in 58.4%, and angiotensin receptor blockers in 7.9%. Comparison with European countries revealed that TURKMI patients experienced MI at younger ages compared with patients in France, Switzerland, and the United Kingdom. The most prevalent risk factors in the TURKMI population were hypercholesterolemia (60.2%), hypertension (49.5%), smoking (48.8%), and diabetes (37.9%).

Conclusion:

The nation-wide TURKMI registry revealed that hypercholesterolemia, hypertension, and smoking were the most prevalent risk factors. TURKMI patients were younger compared with patients in European Countries. The TURKMI registry also confirmed that current treatment guidelines are largely adopted into clinical cardiology practice in Turkey in terms of antiplatelet, anti-ischemic, and anti-lipid therapy.

Keywords: acute myocardial infarction, registry, Turkey, coronary artery disease

Introduction

Management of acute coronary events has evolved rapidly during the past decades (1, 2). Practice guidelines have also improved recommendations with more aggressive targets based on the results of randomized controlled trials. Implementation of these guidelines is associated with an improvement in care and a significant reduction of major adverse coronary events. However, national registries have shown significant gaps between the recommendations of guidelines and their implementation into clinical practice in real-life settings (2). Many countries have reviewed national health policies with the help of these registries to address the extent to which current guidelines have been implemented (3-7). Moreover, many countries continuously revise their health policies to capture updated standards by repeating the national acute coronary registrations in certain time periods. In Turkey, there is no up-to-date registry representing the country’s population of patients with acute myocardial infarction (MI), but there are a few registries that provide information regarding the management of acute MI. Some of these are generalized and based on localized data; most are not representative of the Turkish population (8-10). The only acute MI registry with a high level of representation, TUMAR, was conducted 20 years ago, at a time when noninvasive treatment was more popular and new treatment modalities were not available. Therefore, the results of TUMAR cannot be compared with current practice (11). TURKMI, a nation-wide registry, was conducted to provide insight into the current real-life management of patients with acute MI in cardiology centers representing the population of Turkey. TURKMI also includes demographic information about patients presenting with acute MI in Turkey. In this study, we report the baseline characteristics and patient profile of the TURKMI population (3, 5, 6).

Methods

TURKMI was conducted as a 15-day snapshot registry to enroll consecutive patients with acute MI and evaluate the burden and variation of MI care and outcomes regarding adherence to current practice guidelines in Turkey. The rationale and design of the study have been described in detail previously (12). Briefly, all consecutive patients with acute MI who were admitted to the coronary care units of 50 cardiology clinics within 48 hours of symptom onset were prospectively enrolled between the dates of November 1 and November 15, 2018. The 50 cardiology clinics represented the 12 EuroNUTS statistical regions of Turkey proportional to Turkey’s 2018 census (12, 13). Figure 1 shows the distribution of centers representing Turkey’s population in the 12 EuroNUTS regions. All centers were chosen as emergent centers capable of percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI). There was an angiography team on duty 24 hours a day in 34 centers and an on-call team was available in 16 locations. The study protocol has been reviewed and approved by the Ethics Committee University of Health Sciences, Istanbul Mehmet Akif Ersoy Thoracic and Cardiovascular Surgery Training and Research Hospital (No: 2018-46 on October 9, 2018). Written informed consent was obtained from all participants.

Figure 1.

Centers participating in the TURKMI study and the number of patients enrolled

Men and women aged 18 years or older were enrolled if they fulfilled the following inclusion criteria; 1) hospitalized within 48 hours of onset of symptoms of the index event, 2) had a final (discharge) diagnosis of acute MI, either ST elevation MI (STEMI) or non-ST elevation (NSTEMI) with positive troponin levels, and 3) provided signed informed consent. Patients unwilling or unable to provide consent were excluded (n=3).

Diagnosis of MI was based on both elevated troponin levels and presence of at least 1 of the criteria (12, 14), including symptoms compatible with myocardial ischemia, new, or presumed new significant ST-T wave changes, left bundle branch block (LBBB) on 12-lead electrocardiogram (ECG) or new pathological Q wave on ECG (14). ST elevation consistent with MI was defined as new ST elevation at the J point in at least 2 contiguous leads with the cutoff value of 0.1 mV or higher in all leads except V2 and V3, in which the cutoff values were 0.2 mV or higher in men 40 years or older, 0.25 mV or higher in men younger than 40 years, or 0.15 mV or higher in women (14). In patients who met the MI criteria, STEMI was diagnosed if ST elevation criteria or new or presumed new LBBB was present. Otherwise, a diagnosis of NSTEMI was made. Posterior STEMI was diagnosed if ST depression in leads V1 to V3 accompanied ST elevation in the inferior and/or lateral leads, or if total or near total lesion was detected in the right coronary artery or circumflex artery in patients who underwent coronary angiography.

All enrolled patients underwent routine clinical assessments and received the standard medical care currently performed in routine clinical practice. According to the TURKMI protocol, prescriptions of drugs and indications of diagnostic or therapeutic procedures were left to participating cardiologists’ decision (12). As an observational protocol, patients did not receive any experimental intervention or treatment because of their participation. Baseline information included patient characteristics, medical history, presenting symptoms, clinical characteristics, electrocardiographic findings, and use of cardiac medications. Each patient’s hospital course was recorded in detail. All medications, including doses used before (on admission), in-hospital, and at the time of discharge, were captured. All available laboratory values, including lipid profile, fasting blood sugar, creatinine, white blood cell count, hemoglobin, hematocrit, platelet count, triglyceride, HbA1c, thyroid stimulating hormone, and troponin, were also recorded. ECG, echocardiography, and coronary angiography results were recorded and uploaded to an electronic data capture program.

Statistical analysis

All analyses were performed using SPSS 18.0 for Windows (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY), and a P value of less than 0.05 was considered significant. Categorical variables were presented as number and percentage, and were compared using the χ2 test or Fisher’s exact test between independent groups such as sex and risk categories. Graphical methods (e.g., histogram and probability plot) and analytical methods (e.g., Komogrov-Smirnov test) were used to assess whether continuous variables have normal distribution. These variables were given as means ± standard deviation or medians and interquartile range, depending on whether they have normal distribution or not, and were compared using an independent t test or the Mann-Whitney U test.

Results

A total of 1930 consecutive patients (mean age, 62.0±13.2 years; 26.1 % female) in 50 centers with a diagnosis of acute MI were prospectively enrolled between November 1 and November 16, 2018. Women were older than men (68.3±12.8 years vs. 59.8±12.6 years). The centers participating in the study and the number of patients enrolled are shown in Figure 1. Table 1 presents the baseline clinical characteristics of patients regarding presence of ST elevation (38.1% STEMI; 61.9% NSTEMI). A total of 726 (37.6%) patients were admitted to the study centers by referral from other centers that do not have PCI capability (STEMI: 39.9%, n=288; NSTEMI, 36.6%, n=438).

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics, cardiovascular risk factors, and clinical history of the TURKMI population

| Total n=1930 | NSTEMI n=1195 | STEMI n=735 | P value* | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, years (median, Q1-Q3) | 62 (53-71) | 63 (54-72) | 60 (51-70) | <0.001 |

| Age, year (mean±SD) | 62±13.2 | 63±12.7 | 60.4±13.8 | |

| Female patients, n (%) | 504 (26.1) | 343 (28.7) | 161 (21.9) | <0.001 |

| Body mass index (kg/m2) (median, Q1-Q3) | 27.4 (25-30.8) | 27.7 (25.2-31.1) | 27.1 (24.78-30.1) | 0.071 |

| Risk factors | ||||

| Hypertension, n (%) | ||||

| Based on patient’s self-report | 955 (49.5) | 672 (56.2) | 283 (38.5) | <0.001 |

| Dyslipidemia, n (%) | ||||

| Based on patient’s self-report | 233 (12.1) | 161 (13.5) | 72 (9.8) | 0.016 |

| Hypercholesterolemia (LDL ≥130 mg/dL or total | 875 (60.2) | 588 (64.3) | 287 (53.1) | <0.001 |

| cholesterol ≥200 mg/d or use of LDL-lowering agents)** | ||||

| Low HDL cholesterol (men: <40 mg/dL; women: <50 mg/dL) | 837 (56.6) | 523 (56.5) | 314 (56.8) | 0.928 |

| Elevated triglycerides (≥150 mg/dL) | 612 (43.7) | 418 (47.6) | 194 (37.2) | <0.001 |

| Dyslipidemia (Presence of any of the above criteria), n (%) | 1333 (88.3) | 850 (89.7) | 483 (86.1) | 0.037 |

| Diabetes, n (%) | ||||

| Based on patient’s self-report | 654 (33.9) | 448 (37.5) | 206 (28) | <0.001 |

| Based on patient’s self-report and/or use of anti-diabetic agents | 691 (37.9) | 472 (41.6) | 219 (31.9) | <0.001 |

| Obesity, n (%) | ||||

| Based on patient’s self-report | 112 (5.8) | 66 (5.5) | 46 (6.3) | 0.502 |

| Body mass index ≥30 kg/m2 | 497 (28.7) | 326 (30.5) | 171 (25.8) | 0.034 |

| Smoking, n (%) | 942 (48.8) | 529 (44.3) | 413 (56.2) | <0.001 |

| Family history of premature CVD, n (%) | 188 (9.7) | 109 (9.1) | 79 (10.7) | 0.242 |

| Alcohol, n (%) | 46 (2.4) | 24 (2) | 22 (3) | 0.168 |

| History of CVD, n (%) | ||||

| Coronary involvement (MI and/or CABG and/or PCI) | 550 (28.5) | 418 (35) | 132 (18) | <0.001 |

| Myocardial infarction | 262 (13.6) | 190 (15.9) | 72 (9.8) | <0.001 |

| Percutaneous coronary intervention | 339 (17.6) | 258 (21.6) | 81 (11) | <0.001 |

| Coronary bypass grafting | 165 (8.5) | 139 (11.6) | 26 (3.5) | <0.001 |

| Transient ischemic attack or stroke | 29 (1.5) | 13 (1.1) | 16 (2.2) | 0.056 |

| Peripheral arterial disease | 17 (0.9) | 10 (0.8) | 7 (1) | 0.792 |

| Heart failure | 45 (2.3) | 35 (2.9) | 10 (1.4) | 0.027 |

| Atrial fibrillation | 23 (1.2) | 16 (1.3) | 7 (1) | 0.447 |

| Valve surgery | 5 (0.3) | 5 (0.4) | 0 (0) | 0.164 |

| Pacemaker/intracardiac defibrillator | 7 (0.4) | 5 (0.4) | 2 (0.3) | 0.715 |

| Other | 25 (1.3) | 19 (1.6) | 6 (0.8) | 0.144 |

| Concomitant disease, n (%) | ||||

| Cancer | 54 (2.8) | 30 (2.5) | 24 (3.3) | 0.329 |

| Thyroid disease | 50 (2.6) | 30 (2.5) | 20 (2.7) | 0.777 |

| Renal failure | 103 (5.3) | 72 (6.0) | 31 (4.2) | 0.086 |

| Chronic obstructive lung disease | 95 (4.9) | 68 (5.7) | 27 (3.7) | 0.047 |

| Asthma | 35 (1.8) | 24 (2) | 11 (1.5) | 0.413 |

| History of bleeding | 10 (0.5) | 7 (0.6) | 3 (0.4) | 0.750 |

| Connective tissue disease | 9 (0.5) | 6 (0.5) | 3 (0.4) | 1.000 |

| Other | 142 (7.4) | 93 (7.8) | 49 (6.7) | 0.362 |

P value denotes the comparison of STEMI and NSTEMI.

As there were missing values in both statin use and lipid levels, analysis was conducted by excluding the missing values.

CABG - coronary artery bypass grafting; CVD - cardiovascular disease; HDL - high density lipoproteins; LDL - low density lipoproteins; MI - myocardial infarction; NSTEMI - non-ST elevation MI; PCI - percutaneous coronary intervention; SD - standard deviation; STEMI - ST elevation MI

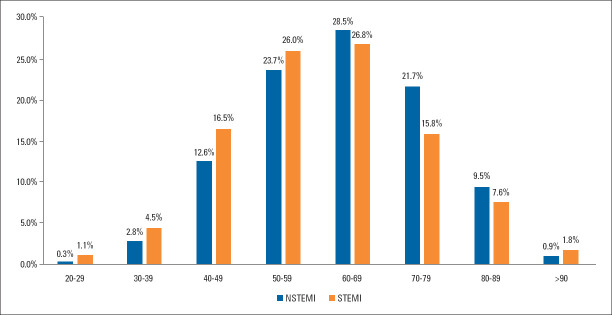

Patients with NSTEMI were older (p<0.001) (Fig. 2, Table 1). However, 22.1% of the STEMI and 15.7% of the NSTEMI patients were younger than 50 years (Fig. 2). Based on the patients’ self-reporting, half had hypertension and one-third were diabetic. Hypercholesterolemia based on the total cholesterol, LDL cholesterol levels, or use of anti-lipid agents was present in 60.2% of the TURKMI population. Diabetes mellitus, hypertension, and hypercholesterolemia were more common in NSTEMI patients than STEMI patients, whereas smoking was more common in STEMI patients than in NSTEMI patients. In both groups, fewer than 30% were women, and the number of women in the NSTEMI group was significantly higher than in the STEMI group (28.7% vs. 21.9%, p=0.001). History of previous coronary event was documented in 550 (28.5) of the patients. History of previous MI, previous coronary artery bypass surgery, or previous PCI was significantly higher in NSTEMI patients than in STEMI patients. In terms of comorbidities, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease was significantly more common in NSTEMI patients than in STEMI patients (Table 1).

Figure 2.

The distribution of age groups of patients hospitalized with acute myocardial infarction in Turkey

The primary complaints of the patients admitted with acute MI were chest pain (95%), dyspnea (17.8%), palpitations (4.1%), cardiac arrest (1.8%), and syncope (1.7%) (Table 2). Although the prevalence of chest pain was similar in both groups, more patients presented with dyspnea or palpitation in the NSTEMI group than in the STEMI group, whereas cardiac arrest was significantly more frequent in the STEMI group (Table 2). Chest pain was the most common presenting symptom in both women (95.4%) and men (94.8%) (p=0.580), whereas shortness of breath (25.8% vs. 15.4%, p<0.001) and palpitation (6.5% vs. 3.3%, p<0.005) were more common in women. There was no difference in the frequency of chest pain in diabetic and non-diabetic patients (94.4% vs. 94.2%), but diabetic patients had more symptoms of dyspnea than non-diabetic patients (23.7% vs. 14.9%, p<0.001). Cardiac arrest was also significantly higher in patients without diabetes (2.3% vs. 0.9%, p=0.035). The primary symptom was chest pain when the elderly (>70 years) and younger (≤70 years) patients were compared (94.6% vs. 95.2%, p=0.538). In the elderly, dyspnea (27.9% vs. 13.7%, p<0.001) and palpitation (6.0% vs. 3.4%, p=0.009) were significantly more frequent than in younger patients.

Table 2.

Presenting symptoms on admission

| All | STEMI | NSTEMI | P value* | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Typical chest pain, n (%) | 1833 (95) | 698 (95) | 1135 (95) | 0.990 |

| Dyspnea, n (%) | 345 (17.9) | 112 (15.2) | 233 (19.5) | 0.018 |

| Palpitation, n (%) | 80 (4.1) | 22 (3) | 58 (4.9) | 0.046 |

| Cardiac arrest, n (%) | 35 (1.8) | 29 (3.9) | 6 (0.5) | <0.001 |

| Syncope, n (%) | 33 (1.7) | 17 (2.3) | 16 (1.3) | 0.109 |

| Other, n (%) | 129 (6.7) | 53 (7.2) | 76 (6.4) | 0.467 |

| Pain in left and/or right arm, n (%) | 22 (1.1) | 9 (1.2) | 13 (1.1) | 0.784 |

P value denotes the comparison of STEMI and NSTEMI.

NSTEMI - non-ST elevation myocardial infarction; STEMI - ST elevation myocardial infarction

On admission, both mean systolic and diastolic blood pressure (BP) levels were significantly higher in NSTEMI patients compared with STEMI patients (systolic BP: 139±25 mm Hg vs. 127±26 mm Hg, p<0.001; diastolic BP: 81±15 mm Hg vs. 77±16 mm Hg, p<0.001). The laboratory and ECG findings of the TURKMI population are presented in Table 3.

Table 3.

Laboratory and electrocardiographic findings of the TURKMI patients

| NSTEMI | STEMI | Total | P value* | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Laboratory findings (Mean±SD) | ||||

| Blood glucose, mg/dL | 128.94±57.51 | 138.01±64.59 | 132.31±60.37 | 0.001 |

| Creatinine | 1.17±2.02 | 1.03±0.72 | 1.12±1.66 | 0.019 |

| White blood cell | 10.2±3.49 | 13.45±29.14 | 11.44±18.25 | <0.001 |

| Total cholesterol, mg/dL | 194.23±52 | 193.12±49.73 | 193.81±51.15 | 0.499 |

| LDL cholesterol, mg/dL (median 25%–75%) | 119 (90.1-148.0) | 121 (98-150) | 120 (94-149) | 0.135 |

| HDL cholesterol, mg/dL | 41.42±10.82 | 40.92±9.76 | 41.23±10.43 | 0.543 |

| Triglycerides, mg/dL | 171.5±121.17 | 151.91±119.65 | 164.15±120.93 | <0.001 |

| Electrocardiography findings on admission | ||||

| Rhythm, n (%) | ||||

| Sinus | 1083 (90.6) | 679 (92.4) | 1762 (91.3) | 0.185 |

| Atrial fibrillation/flutter | 78 (6.5) | 33 (4.4) | 110 (5.7) | 0.046 |

| Pacemaker | 5 (0.4) | 0 (0) | 5 (0.3) | 0.164 |

| Ventricular fibrillation/flutter | 2 (0.2) | 7 (1) | 9 (0.5) | 0.032 |

| Others | 10 (0.8) | 13 (1.8) | 23 (1.2) | 0.067 |

| Rate (pulse/min), median (Q1-Q3) | 79 (70-91) | 80 (68-92) | 79 (69-91) | 0.319 |

| New LBBB, n (%) | 22 (1.9) | 12 (1.7) | 34 (1.8) | 0.680 |

| New RBBB n (%) | 41 (3.5) | 27 (3.7) | 68 (3.6) | 0.846 |

| AV block, n (%) | 14 (1.2) | 30 (4.2) | 44 (2.3) | <0.001 |

| ST segment depression in 2 adjacent derivations ≥1 mm, n (%) | 362 (31) | 467 (64.6) | 829 (43.8) | <0.001 |

| T wave inversion, n (%) | 353 (30.3) | 124 (17.2) | 477 (25.3) | <0.001 |

| Non-specific ST/T changes, n (%) | 353 (30.3) | 78 (10.9) | 431 (22.9) | <0.001 |

P value denotes the comparison of STEMI and NSTEMI.

AV- atrioventricular block; LBBB - left bundle branch block; HDL - high density lipoprotein; LDL - low density lipoprotein; NSTEMI - non-ST elevation myocardial infarction;

RBBB - right bundle branch block; STEMI - ST elevation myocardial infarction

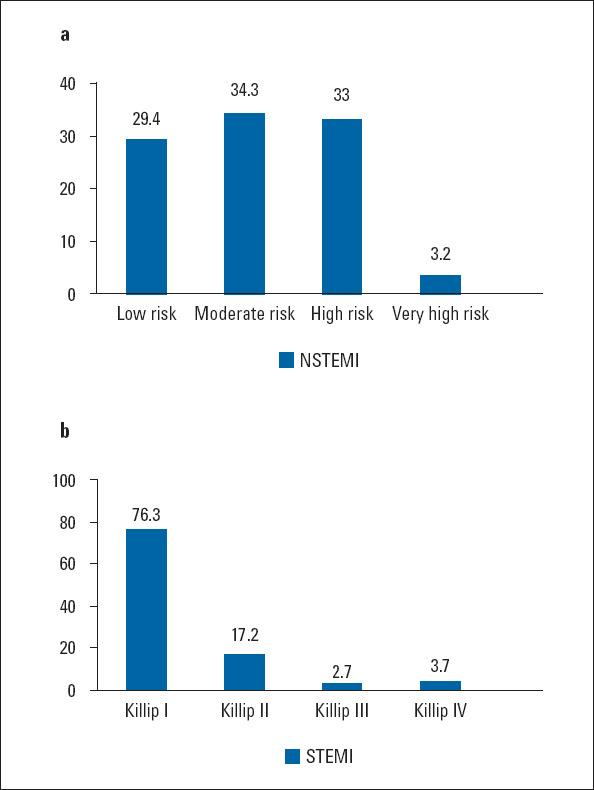

NSTEMI patients were classified according to the European Society of Cardiology guideline criteria (15) as low risk (29.4%), moderate risk (34.3%), high risk (33%), and very high risk (3.2%) at admission. Meanwhile, at the time of admission, 76.3% STEMI patients were Killip class I, 17.2% were class II, 2.7% were class III, and 3.7% were class IV (Fig. 3). Patients’ medications on admission and at the time of discharge are summarized in Table 4. On admission, more NSTEMI patients were on anti-platelets (aspirin, clopidogrel), beta blockers, calcium antagonists, anti-lipid agents, ACE inhibitors, diuretics, and anti-diabetic drugs compared with STEMI patients.

Figure 3.

(a) Risk classification of patients with NSTEMI. (b) Killip classification of patients with STEMI

Table 4.

Medications on admission and prescribed at discharge

| Total | NSTEMI | STEMI | P value* | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Medications on admission, n (%) | ||||

| Antiplatelet agents | ||||

| Acetyl salicylic acid | 534 (29.8) | 395 (35.3) | 139 (20.7) | <0.001 |

| Clopidogrel | 208 (11.6) | 168 (15) | 40 (6) | <0.001 |

| Ticagrelor | 26 (1.5) | 18 (1.6) | 8 (1.2) | 0.475 |

| Prasugrel | 3 (0.2) | 2 (0.2) | 1 (0.1) | -† |

| Beta blockers | 397 (22.2) | 311 (27.8) | 86 (12.8) | <0.001 |

| Calcium antagonists | 243 (13.6) | 170 (15.2) | 73 (10.9) | 0.010 |

| Nitrates | 70 (3.9) | 64 (5.7) | 6 (0.9) | <0.001 |

| Anti-lipid agents | 256 (14.3) | 203 (18.2) | 53 (7.9) | <0.001 |

| ACE inhibitors | 284 (15.9) | 205 (18.3) | 79 (11.8) | <0.001 |

| Medications prescribed at discharge, n (%) | ||||

| Antiplatelet agents | ||||

| Acetyl salicylic acid | 1830 (99.3) | 1141 (99) | 689 (99.9) | 0.038 |

| Clopidogrel | 930 (50.5) | 689 (59.8) | 241 (34.9) | <0.001 |

| Ticagrelor | 750 (40.7) | 354 (30.7) | 396 (57.4) | <0.001 |

| Prasugrel | 58 (3.1) | 22 (1.9) | 36 (5.2) | <0.001 |

| Dual antiplatelet therapy | 1731 (94) | 1059 (91.9) | 672 (97.4) | <0.001 |

| Anticoagulant agents | 68 (3.5) | 53 (4.4) | 15 (2) | |

| Warfarin | 28 (1.5) | 21 (1.8) | 7 (1) | |

| Dabigatran | 7 (0.4) | 6 (0.5) | 1 (0.1) | 0.270 |

| Rivaroxaban | 9 (0.5) | 6 (0.5) | 3 (0.4) | 1,000 |

| Apiksaban | 20 (1.1) | 17 (1.4) | 3 (0.4) | 0.040 |

| Edoxaban | 4 (0.2) | 3 (0.3) | 1 (0.1) | -† |

| Beta blockers | 1544 (85.0) | 965 (84.5) | 579 (85.9) | 0.418 |

| Calcium antagonists | 246 (13.5) | 192 (16.8) | 54 (8.0) | <0.001 |

| Anti-lipid agents | 1756 (96.3) | 1103 (96.2) | 653 (96.3) | 0.944 |

| Diuretics | 298 (16.4) | 204 (17.9) | 94 (13.9) | 0.029 |

| ACE inhibitors | 1061 (58.4) | 645 (56.5) | 416 (61.7) | 0.029 |

| Angiotension receptor blockers | 144 (7.9) | 103 (9.0) | 41 (6.1) | 0.025 |

| Digitalis | 9 (0.5) | 7 (0.6) | 2 (0.3) | 0.498 |

| Anti-arrhythmic agents | 24 (1.3) | 16 (1.4) | 8 (1.2) | 0.700 |

| Nitrates | 152 (8.4) | 124 (10.9) | 28 (4.2) | <0.001 |

| Anti-diabetic agents | 208 (11.5) | 145 (12.7) | 63 (9.3) | 0.030 |

P value denotes the comparison of STEMI and NSTEMI.

Not analyzed.

ACE - angiotension converting enzyme; NSTEMI - non-ST elevation myocardial infarction; STEMI - ST elevation myocardial infarction

Coronary angiography was performed in 93.7% of the study population, and PCI was performed in 73.2% at index hospitalization. The proportions of coronary angiography and PCI were significantly higher in STEMI patients compared with NSTEMI patients (98.8% vs. 90.5%, p<0.001; 94.4% vs. 60.2%, p<0.001, respectively). Fibrinolytic therapy was administered to only 13 patients (0.018%).

During the PCI mostly unfractionated heparin was used as an anticoagulant (96.3% overall; 97.0% in STEMI; 95.7% in NSTEMI). The use of low molecular weight heparin was exceptionally low. In 12.4% of the patients, a GPIIb/IIIa inhibitor was used during the procedure, with use being significantly higher in patients with STEMI (18.5% vs. 8.5%). The drugs given at discharge are noted in Table 4. Almost all patients were put on antiplatelet therapy. Aspirin was prescribed in 99.3% of the patients, and 94% were on dual antiplatelet therapy (DAPT). Among the DAPT drugs used, clopidogrel was the most preferred drug at 50.5%, followed by ticagrelor in 40.7% and prasugrel in 3.1%. Beta blockers were prescribed in 85.0% of patients, anti-lipid drugs in 96.3%, ACE inhibitors in 58.4%, and angiotensin receptor blockers in 7.9%.

Discussion

The baseline characteristics of the TURKMI study provided important information regarding clinical characteristics and the current clinical management of 1930 consecutive patients admitted to cardiology clinics in Turkey with acute MI within 48 hours of the onset of symptoms. A previous registry in Turkey, the TUMAR study, enrolled 3358 patients in 1998 and 1999 with the diagnosis of acute MI who were hospitalized in coronary intensive care units within 24 hours of symptom onset (11). The TUMAR study covered 52 centers from 23 provinces for a period of 1 year. Like the TURKMI study, the TURK-AKS study (16) was designed as a snapshot registry of 1 month, but the primary limitation was a lack of enrollment of consecutive patients. Similar to the TURKMI registry, this study was conducted to evaluate patient profiles, as well as diagnostic and practice patterns in acute coronary syndrome in Turkey. TURKMI enrolled 1930 patients with NSTEMI or STEMI (excluding unstable angina) within a prespecified 2-week period. The TURK-AKS study enrolled 3695 participants with acute coronary syndrome, including unstable angina, within a 3-year period between 2007 and 2010. However, because the TURK-AKS study enrolled patients in a non-consecutive way, its level of representation is expected to be low.

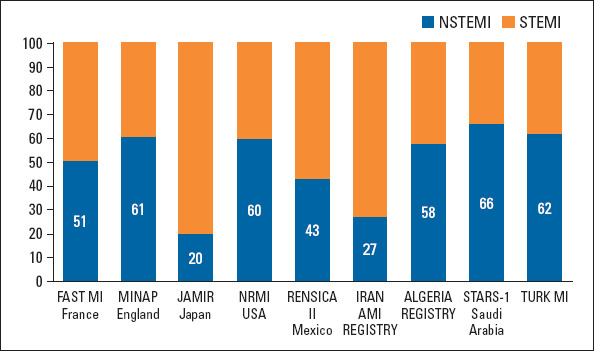

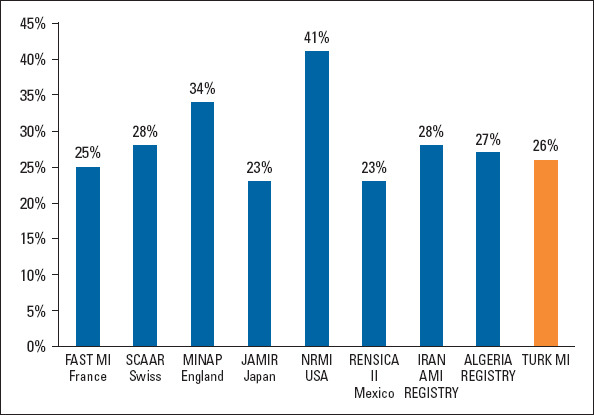

The number of patients in TURKMI registry presenting with NSTEMI was higher; 6 out of every 10 MIs are NSTEMI. This proportion of NSTEMI patients (61.9%) was similar to those observed in the American National Registry of Myocardial Infarction and English Myocardial Ischemia National Audit Project registries (Fig. 4) (17, 18). The proportion of NSTEMI patients was slightly higher in the Saudi Arabian registry (66%) than in the TURKMI registry. NSTEMIs constitute 58% of the Algerian and 51% of the French (FAST-MI) registries (6, 7, 19, 20). Meanwhile, in both the Iranian registry and the Japanese Acute Myocardial Infarction Registry, the rate of NSTEMI was much lower (27% and 20%, respectively) (21, 22).

Figure 4.

NSTEMI rates (%) in TURKMI and other country’s registries

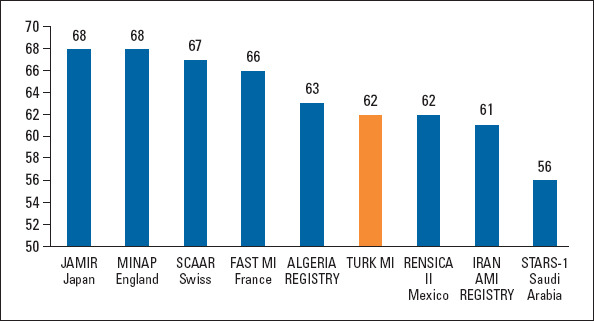

The mean age of the TURKMI population was 62±13 years. Patients with STEMI were significantly younger than the patients with NSTEMI, which might be explained by the higher rates of collaterals in older patients. TURKMI patients were similar in age compared with Iranian (21), Mexican (23), and Algerian (20) MI patients at the time of the index MI (Fig. 5), whereas the average MI age was younger (56 years) in Saudi Arabian MI patients (19). TURKMI patients experienced MI at younger ages compared with patients in other countries, including France (6, 7), Switzerland (24), the United Kingdom (18), and Japan (Fig. 6) (22). This is most likely associated with the high prevalence of dyslipidemias and smoking in Turkey. Moreover, the high prevalence of consanguinity probably has an important contribution to earlier MIs in Turkey (25).

Figure 5.

Mean age in TURKMI verses other acute myocardial infarction registries

Figure 6.

Percentage of women enrolled in TURKMI and other registries

Evaluation of cardiovascular risk factors revealed that hypercholesterolemia, hypertension, smoking, and diabetes were the most prevalent risk factors in patients presenting with MI in Turkey, as stated in previous analysis (26). The prevalence of smoking was significantly higher than the registries of France (36%), the United States (31%), and England (29%) (6, 7, 17, 18). TURKMI harbors higher smoking rate, with almost half of the MI population being current smokers.

The primary complaint was chest pain regardless of the type of MI, sex, age, and presence of diabetes. In the TURKMI study, the proportion of chest pain was 95% compared with 80% in the FAST-MI registry. This difference is probably due to typical chest pain being used as an inclusion criterion in the FAST-MI registry (6, 7). Similar to the FAST-MI study, cardiac arrest was more common in patients with STEMI, and shortness of breath was more prevalent in NSTEMIs in the TURKMI study. This is likely because the NSTEMI group had a higher proportion of women, previous MI, and heart failure. As expected, because of the high proportion of previous cardiovascular disease, the use of aspirin or other anti-platelets, beta blockers, and lipid lowering therapies was prevalent in patients presenting with NSTEMI on admission.

TURKMI revealed that guideline-recommended cardivascular medication at discharge is acceptable for many drugs, and that compliance was better than that seen in other national registries. At discharge, almost all patients were on aspirin therapy (99.3%), and 94% were on DAPT. The European Society of Cardiology guideline recommends ticagrelor or prasugrel in preference to clopidogrel as second antiplatelet agents for DAPT. These 3 antiplatelet agents are reimbursed in Turkey. However, other than aspiring, the most common drugs prescribed were clopidogrel (50.5%) and by ticagrelor (40.7%). Only 3.1% of the patients were on prasugrel. Most patients (96.3%) were on lipid lowering treatment at the time of discharge.

Study limitations

As stated in the rationale and design paper (12), TURKMI harbors the same major drawbacks of registries in general. In addition, the number of centers (n=50) could be considered a limitation. However, this number was selected because of budget restrictions. The number of centers in each EurNUTS region was determined proportional to the population to represent the Turkish people appropriately. Also, we selected hospitals capable of PCI, assuming that nearly all acute MI patients would eventually be directed to these centers. Otherwise, we would have missing values for patients who were transferred to other centers. Of note, coronary angiography units and interventional cardiologists are available in all provinces and most major towns in Turkey (27). Therefore, all patients with acute MI in all geographical regions in the country could reach cardiology centers with the capability of performing coronary angiography and percutaneous procedures within 1 hour. Therefore, with the assumption that all acute MI patients, including those who first presented to non-PCI centers, would be admitted or transferred to PCI-capable centers in the index region, all patients admitted within the first 48 hours of symptom onset were included. In contrast to previous registries in Turkey, we enrolled patients consecutively within a prespecified 2-week period, which also increases the level of representation of MI patients in Turkey. However, this type of enrollment might preclude obtaining information regarding seasonal variations of MI (28). Moreover, enrolling only patients presenting alive to cardiology centers will also lead to a bias of exclusion of those who cannot admit to care centers (death, elderly, bedridden, etc.).

Conclusion

The nation-wide TURKMI study outlined the characteristics of patients admitted with acute MI within 48 hours of the onset of symptoms to the selected cardiology centers capable of PCI in Turkey. Turkish MI patients were more likely to have dyslipidemia, diabetes, and smoking history and were younger compared with patients in European Countries. TURKMI also confirmed that current treatment guidelines have largely been adopted into clinical cardiology practice in Turkey in terms of antiplatelet, anti-ischemic, and anti-lipid therapy.

Acknowledgments:

TURKMI is an investigator-initiated study sponsored by the Turkish Society of Cardiology that receives major funding from Astra-Zeneca Company for this project.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest: None declared.

Peer-review: Externally peer-reviewed.

Authorship contributions: Concept – M.K.E., M.Kayıkçıoğlu, M.Kılıçkap, C.B.A., İ.H.K., İ.A., Y.G., E.Özkan, T.Ş., O.İ., E.Örnek, R.A., N.A., U.Z., Ü.Y.S., M.D., H.T., A.D., M.Y., M.A., O.S.D., M.U.S.; Design – M.K.E., M.Kayıkçıoğlu, M.Kılıçkap, C.B.A., İ.H.K., İ.A., Y.G., E.Özkan, T.Ş., O.İ., E.Örnek, R.A., N.A., U.Z., Ü.Y.S., M.D., H.T., A.D., M.Y., M.A., O.S.D., M.U.S.; Supervision – M.K.E., M.Kayıkçıoğlu, M.Kılıçkap, C.B.A., İ.H.K., İ.A., Y.G., E.Özkan, T.Ş., O.İ., E.Örnek, R.A., N.A., U.Z., Ü.Y.S., M.D., H.T., A.D., M.Y., M.A., O.S.D., M.U.S.; Fundings – M.K.E., M.Kayıkçıoğlu, M.Kılıçkap, C.B.A., İ.H.K., İ.A., Y.G., E.Özkan, T.Ş., O.İ., E.Örnek, R.A., N.A., U.Z., Ü.Y.S., M.D., H.T., A.D., M.Y., M.A., O.S.D., M.U.S.; Materials – M.K.E., M.Kayıkçıoğlu, M.Kılıçkap, C.B.A., İ.H.K., İ.A., Y.G., E.Özkan, T.Ş., O.İ., E.Örnek, R.A., N.A., U.Z., Ü.Y.S., M.D., H.T., A.D., M.Y., M.A., O.S.D., M.U.S.; Data collection and/or processing – M.K.E., M.Kayıkçıoğlu, M.Kılıçkap, C.B.A., İ.H.K., İ.A., Y.G., E.Özkan, T.Ş., O.İ., E.Örnek, R.A., N.A., U.Z., Ü.Y.S., M.D., H.T., A.D., M.Y., M.A., O.S.D., M.U.S.; Analysis and/or interpretation – M.K.E., M.Kayıkçıoğlu, M.Kılıçkap, C.B.A., İ.H.K., İ.A., Y.G., E.Özkan, T.Ş., O.İ., E.Örnek, R.A., N.A., U.Z., Ü.Y.S., M.D., H.T., A.D., M.Y., M.A., O.S.D., M.U.S.; Literature search – M.K.E., M.Kayıkçıoğlu, M.Kılıçkap, C.B.A., İ.H.K., İ.A., Y.G., E.Özkan, T.Ş., O.İ., E.Örnek, R.A., N.A., U.Z., Ü.Y.S., M.D., H.T., A.D., M.Y., M.A., O.S.D., M.U.S.; Writing – M.K.E., M.Kayıkçıoğlu, M.Kılıçkap, C.B.A., İ.H.K., İ.A., Y.G., E.Özkan, T.Ş., O.İ., E.Örnek, R.A., N.A., U.Z., Ü.Y.S., M.D., H.T., A.D., M.Y., M.A., O.S.D., M.U.S.; Critical review – M.K.E., M.Kayıkçıoğlu, M.Kılıçkap, C.B.A., İ.H.K., İ.A., Y.G., E.Özkan, T.Ş., O.İ., E.Örnek, R.A., N.A., U.Z., Ü.Y.S., M.D., H.T., A.D., M.Y., M.A., O.S.D., M.U.S.

TURKMI STUDY GROUP: Abant Izzet Baysal University: Mehmet Inanir, Osman Yasin Yalçin, Yilmaz Gunes; Adana City Hospital: Ibrahim Halil Kurt, Omer Genc, Abdullah Yildirim; Adiyaman University: Ramazan Asoglu; Aksaray University: Sinan Inci; Ankara NumuneTraining and Research Hospital: Ender Ornek, Mustafa Cetin, Emrullah Kiziltunc; Ankara University: Mustafa Kilickap; Ankara Yuksek Ihtisas Training and Research Hospital: Cagrı Yayla, Ahmet Goktuğ Ertem, Mehmet Kadri Akboga; Antalya Training and Research Hospital : Ahmet Genc, Gulsum Meral Yılmaz Oztekin; Batman State Hospital: Mesut Gitmez; Bursa Yuksek Ihtisas Training and Research Hospital; Burcu Tuncay, Veysi Can, Hasan Ari; Bulent Ecevit University: Fatih Pasa Tatar, Mustafa Umut Somuncu; Canakkale Onsekiz Mart University; Emine Gazi; Cukurova University; Cuma Yeşildas, Onur Sinan Deveci; Denizli State Hospital: Okan Er; Diyarbakir Gazi Yasargil Training and Research Hospital: Onder Ozturk; Ege University: Aytac Candemir, Meral Kayikçioglu, Oguz Yavuzgil; Elazıg Training and Research Hospital: Cetin Mirzaoğlu; Erzincan Binali Yildirim University: Eftal Murat Bakirci, Husnu Degirmenci; Harran University: Feyzullah Besli; Istanbul Bagcılar Training and Research Hospital: Orhan Ince, Emirhan Hancıoglu; Istanbul Bakirkoy Sadi Konuk Training and Research Hospital: Ibrahim Faruk Akurk, Ersan Oflar, Nihan Turhan Çaglar; Istanbul Bezmi Alem University: Hatice Aylin Yamac Halac; Istanbul Haseki Training and Research Hospital: Muhsin Kalyoncuoglu; Istanbul Kartal Kosuyolu Training and Research Hospital: Ismail Balaban, Mesut Karatas, Cevat Kirma; Istanbul Mehmet Akif Ersoy Training and Research Hospital: Arda Guler, Cemil Can, Arda Can Dogan, Ahmet Arif Yalcin; Istanbul International Sisli Kolan Hospital: Mustafa Kemal Erol; Istanbul Siyami Ersek Training and Research Hospital: Can Baba Arin; Istanbul University Cardiology Institute; Umit Yasar Sinan; Izmir Tepecik Training and Research Hospital: Murat Kücükokur, Oner Ozdogan; Kahramanmaras Sutcu Imam University: Ekrem Aksu, Hakan Günes; Kayseri Training and Research Hospital: Ziya Simsek, Eyüp Ozkan; Kırıkkale Yuksek Ihtisas Training and Research Hospital: Cengiz Sabanoğlu, Yunus Celik; Kutahya Health Science University: Taner Sen, Mehmet Ali Astarcıoglu; Malatya Training and Research Hospital: Ibrahim Aktas, Gokhan Gozubuyuk; Marmara University: Mustafa Kursat Tigen, Murat Sunbul; Mersin University: Ayça Arslan, Ahmet Celik; Mustafa Kemal University: Oguz Akkus; Necmettin Erbakan University: Yakup Alsancak; Osmangazi University: Muhammet Dural, Kadir Ugur Mert; Mugla Yucelen Hospital: Nuri Kose; Pamukkale University: Ismail Dogu Kiliç; Recep Tayyip Erdogan University: Nadir Emlek; Sakarya University: Ibrahim Kocayigit; Samsun Training and Research Hospital: Ahmet Yanik, Mustafa Yenerçag; Trabzon Ahi Evran Training and Research Hospital: Omer Faruk Çitrakoglu, Ihsan Dursun; Trakya University: Utku Zeybey, Servet Altay; Urfa Mehmet Akif Inan Training and Research Hospital: Sadettin Selcuk Baysal; Van Training and Research Hospital: Nesim Aladag, Remzi Sarikaya, Ramazan Duz; Van Yuzuncu Yil University: Mustafa Tuncer, Hasim Tuner; Yalova State Hospital: Ismail Ungan, Yildirim Beyazit University: Bilge Duran Karaduman, Engin Bozkurt.

References

- 1.Rasmussen JN, Chong A, Alter DA. Relationship between adherence to evidence-based pharmacotherapy and long-term mortality after acute myocardial infarction. JAMA. 2007;297:177–86. doi: 10.1001/jama.297.2.177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Smolina K, Wright FL, Rayner M, Goldacre MJ. Determinants of the decline in mortality from acute myocardial infarction in England between 2002 and 2010:linked national database study. BMJ. 2012;344:d8059. doi: 10.1136/bmj.d8059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chung SC, Gedeborg R, Nicholas O, James S, Jeppsson A, Wolfe C, et al. Acute myocardial infarction:a comparison of short-term survival in national outcome registries in Sweden and the UK. Lancet. 2014;383:1305–12. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)62070-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ibanez B, James S, Agewall S, Antunes MJ, Bucciarelli-Ducci C, Bueno H, et al. ESC Scientific Document Group. 2017 ESC Guidelines for the management of acute myocardial infarction in patients presenting with ST-segment elevation:The Task Force for the management of acute myocardial infarction in patients presenting with ST-segment elevation of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) Eur Heart J. 2018;39:119–77. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehx393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Authors/Task Force Members. Piepoli MF, Hoes AW, Agewall S, Albus C, Brotons C, Catapano AL, et al. 2016 European Guidelines on cardiovascular disease prevention in clinical practice:The Sixth Joint Task Force of the European Society of Cardiology and Other Societies on Cardiovascular Disease Prevention in Clinical Practice (constituted by representatives of 10 societies and by invited experts) Developed with the special contribution of the European Association for Cardiovascular Prevention &Rehabilitation (EACPR) Atherosclerosis. 2016;252:207–74. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2016.05.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Puymirat E, Cayla G, Cottin Y, Elbaz M, Henry P, Gerbaud E, et al. Twenty-year trends in profile, management and outcomes of patients with ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction according to use of reperfusion therapy:Data from the FAST-MI program 1995-2015. Am Heart J. 2019;214:97–106. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2019.05.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Schiele F, Gale CP, Simon T, Fox KAA, Bueno H, Lettino M, et al. Assessment of Quality Indicators for Acute Myocardial Infarction in the FAST-MI (French Registry of Acute ST-Elevation or Non-ST-Elevation Myocardial Infarction) Registries. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes. 2017;10 doi: 10.1161/CIRCOUTCOMES.116.003336. pii e003336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Doğan S, Dursun H, Can H, Ellidokuz H, Kaya D. Long-term assessment of coronary care unit patient profile and outcomes:analyses of the 12-years patient records. Turk J Med Sci. 2016;46:801–6. doi: 10.3906/sag-1502-88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kayikcioglu M, Alan B, Payzın S, Can LH. [Lipid profile, familial hypercholesterolemia prevalence, and 2-year cardiovascular outcome assessment in acute coronary syndrome:Real-life data of a retrospective cohort] Turk Kardiyol Dern Ars. 2019;47:476–86. doi: 10.5543/tkda.2019.07360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ertaş FS, Tokgözoğlu L EPICOR Study Group. Pre- and in-hospital antithrombotic management patterns and in-hospital outcomes in patients with acute coronary syndrome:data from the Turkish arm of the EPICOR study. Anatol J Cardiol. 2016;16:900–15. doi: 10.14744/AnatolJCardiol.2016.6755. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Enar R. 2nd ed. İstanbul: Nobel Tıp Kitabevi; 2004. Acute myocardial infarction Thrombocardiology [Turkish] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Erol MK, Kayıkçıoğlu M, Kılıçkap M. Rationale and design of the Turkish acute myocardial infarction registry:The TURKMI Study. Anatol J Cardiol. 2020;23:169–75. doi: 10.14744/AnatolJCardiol.2019.57522. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wikipedia contributors. NUTS statistical regions of Turkey [Internet]. Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia 2019 Apr 14, 20:24 UTC [cited 2019 Aug 16] (accessed Jan 2020) Available from:URL:https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=NUTS_statistical_regions_of_Turkey&oldid=892478048 .

- 14.Thygesen K, Alpert JS, Jaffe AS, Simoons ML, Chaitman BR, White HD, et al. Writing Group on the Joint ESC/ACCF/AHA/WHF Task Force for the Universal Definition of Myocardial Infarction. Third universal definition of myocardial infarction. Eur Heart J. 2012;33:2551–67. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehs184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Roffi M, Patrono C, Collet JP, Mueller C, Valgimigli M, Andreotti F, et al. ESC Scientific Document Group. 2015 ESC Guidelines for the management of acute coronary syndromes in patients presenting without persistent ST-segment elevation:Task Force for the Management of Acute Coronary Syndromes in Patients Presenting without Persistent ST-Segment Elevation of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) Eur Heart J. 2016;37:267–315. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehv320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kozan O, Ergene O, Oto A, Kaplan K TURK-AKS Investigators. A real life registry to evaluate patient profile, diagnostic and practice patterns in Acute Coronary Syndrome in Turkey:TURK-AKS study. Int J Cardiovascular Academy. 2017;3:85–93. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pitta SR, Grzybowski M, Welch RD, Frederick PD, Wahl R, Zalenski RJ. ST-segment depression on the initial electrocardiogram in acute myocardial infarction-prognostic significance and its effect on short-term mortality:A report from the National Registry of Myocardial Infarction (NRMI-2, 3, 4) Am J Cardiol. 2005;95:843–8. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2004.12.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wilkinson C, Weston C, Timmis A, Quinn T, Keys A, Gale CP. The Myocardial Ischaemia National Audit Project (MINAP) Eur Heart J Qual Care Clin Outcomes. 2020;6:19–22. doi: 10.1093/ehjqcco/qcz052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Alhabib KF, Kinsara AJ, Alghamdi S, Al-Murayeh M, Hussein GA, AlSaif S, et al. The first survey of the Saudi Acute Myocardial Infarction Registry Program:Main results and long-term outcomes (STARS-1 Program) PLoS One. 2019;14:e0216551. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0216551. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Boussouf K, Zaidi Z, Kaddour F, Djelaoudji A, Benkobbi S, Bayadi N, et al. Clinical Epidemiology of Acute Myocardial Infarction in Setif, Algeria:Finding from the Setif-AMI Registry. Health Sci J. 2019;13:633. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bahramali E, Askari A, Zakeri H, Farjam M, Dehghan A, Zendehdel K. Fasa Registry on Acute Myocardial Infarction (FaRMI):Feasibility Study and Pilot Phase Results. PLoS One. 2016;11:e0167579. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0167579. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Honda S, Nishihira K, Kojima S, Takegami M, Asaumi Y, Suzuki M, et al. JAMIR investigators. Rationale, Design, and Baseline Characteristics of the Prospective Japan Acute Myocardial Infarction Registry (JAMIR) Cardiovasc Drugs Ther. 2019;33:97–103. doi: 10.1007/s10557-018-6839-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Juárez-Herrera Ú, Jerjes-Sánchez C RENASICA II Investigators. Risk factors, therapeutic approaches, and in-hospital outcomes in Mexicans with ST-elevation acute myocardial infarction:the RENASICA II multicenter registry. Clin Cardiol. 2013;36:241–8. doi: 10.1002/clc.22107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Radovanovic D, Erne P, Urban P, Bertel O, Rickli H, Gaspoz JM AMIS Plus Investigators. Gender differences in management and outcomes in patients with acute coronary syndromes:results on 20.290 patients from the AMIS Plus Registry. Heart. 2007;93:1369–75. doi: 10.1136/hrt.2006.106781. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Turkish Statistical Institute. Turkish family life evaluation 2016 (accessed Jan 2020) Available from:URL;http://www.tuik.gov.tr/HbPrint.do?id=24646 .

- 26.Balbay Y, Gagnon-Arpin I, Malhan S, Öksüz ME, Sutherland G, Dobrescu A, et al. The impact of addressing modifiable risk factors to reduce the burden of cardiovascular disease in Turkey. Turk Kardiyol Dern Ars. 2019;47:487–97. doi: 10.5543/tkda.2019.40330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kayikcioğlu M, Oto A. Control and Management of Cardiovascular Disease in Turkey. Circulation. 2020;141:7–9. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.119.037606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Spencer FA, Goldberg RJ, Becker RC, Gore JM. Seasonal distribution of acute myocardial infarction in the second National Registry of Myocardial Infarction. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1998;31:1226–33. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(98)00098-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]