Abstract

Background

The association between the polymorphisms in the vitamin D receptor (VDR) gene and the risk of type 1 diabetes mellitus (T1DM) has been evaluated in several studies. However, the findings were inconclusive. Thus, we conducted a meta-analysis to comprehensively evaluate the effect of VDR gene polymorphisms on the risk of T1DM.

Methods

All relevant studies reporting the association between VDR gene polymorphisms and susceptibility to T1DM published up to May 2020 were identified by comprehensive systematic database search in ISI Web of Science, Scopus, and PubMed/MEDLINE. Strength of association were assessed by calculating of pooled odds ratios (ORs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs). The methodological quality of each study was assessed according to the Newcastle–Ottawa Scale. To find the potential sources of heterogeneity, meta-regression and subgroup analysis were also performed.

Results

A total of 39 case–control studies were included in this meta-analysis. The results of overall population rejected any significant association between VDR gene polymorphisms and T1DM risk. However, the pooled results of subgroup analysis revealed significant negative and positive associations between FokI and BsmI polymorphisms and T1DM in Africans and Americans, respectively.

Conclusions

This meta-analysis suggested a significant association between VDR gene polymorphism and T1DM susceptibility in ethnic-specific analysis.

Keywords: Vitamin D receptor, Type 1 diabetes mellitus, Polymorphism, Meta-analysis

Background

Type 1 diabetes mellitus (T1DM) is a globally-widespread disease that is characterized by a reduction in insulin production or the production of ineffective insulin [1]. It is generally believed that the immune-associated destruction of beta cells of the islets of Langerhans causes the disease, resulting in lower insulin levels (that is called type 1a diabetes mellitus). In a smaller T1DM subset, no evidence of autoimmunity can be found (type 1b) [2]. T1DM constitutes roughly 5 to 10% of all diabetes cases, and its prevalence is still rising [3]. With more than half a million children living with T1DM, and almost 90,000 children diagnosed each year, T1DM inflicts mostly children of under 15 years of age [4]. It is well known that T1DM is a multi-factorial autoimmune disorder caused by interactions between genetic and environmental factors [5].

Vitamin D (VitD) is a steroid molecule that has many roles in the body, such as regulation of the immune cells. In addition to immune responses, VitD is also involved in the etiopathogenesis of several disorders, such as cancer, autoimmune disorders, cardiovascular disorders, asthma, and diabetes [6–9]. In animal model of T1DM, VitD suppresses the occurrence of diabetes, by regulating the T helper (Th) 1/Th2 cytokine balance in the local pancreatic lesions [10, 11]. Moreover, VitD inhibits T cell activation and secretion of pro-inflammatory cytokines, such as interleukin (IL)-1, IL-6, IL-12, tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-α, and interferon (IFN)-γ, which are involved in the pathogenesis of T1DM [12–14]. Mostly, VitD exerts its function through vitamin D receptor (VDR), which is found in the nuclei of target cells, such as lymphocytes, macrophages, and pancreatic cells. VDR is a member of the nuclear hormone receptors superfamily and has been linked to insulin sensitivity and secretion [15].

Four common single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) of VDR gene are FokI (rs2228570), TaqI (rs731236), BsmI (rs1544410), and ApaI (rs7975232). Among them, ApaI, BsmI, and TaqI polymorphisms are located in the 3′-end of VDR gene which lead to silent mutation associated with increased VDR mRNA stability. In contrast, FokI SNP is located in the start codon that produces a protein with shorter size (424 amino acids), which is more active than the long form (427 amino acids) [8, 16, 17]. Over the course of past few decades, the VDR gene polymorphisms have been associated with susceptibility to numerous autoimmune disorders [8, 18, 19].

In recent years, several studies have investigated the association between VDR gene SNPs and T1DM in all over the world, which have yielded conflicting results. The reasons for these discrepancies might be small sample sizes, clinical heterogeneity, and low statistical power. Therefore, a comprehensive meta-analysis might be the best way to solve these problems. Two previous meta-analyses performed by Tizaouia et al. in 2014 [20] and Guo et al. in 2006 [21] reported that VDR gene polymorphisms were not associated with the susceptibility to T1DM. However, Zhang et al. in 2012 [22] demonstrated that BsmI polymorphism was significantly associated with the risk of T1DM. Furthermore, Sahin et al. in 2017 indicated that BsmI and TaqI polymorphisms were associated withT1DM risk in children with less than average 15 years old [23]. Qin et al. in 2014 evaluated the association of only BsmI SNP with T1DM risk and demonstrated its association in the overall analysis, as well as in Asians, Latino, and Africans [24]. In 2014, Wang et al., by including 20 studies, reported that BsmI polymorphism might be a risk factor for susceptibility to T1DM in the East Asian population, and the FokI polymorphism was associated with an increased risk of T1DM in the West Asian population [25].

Since several articles published after the last meta-analysis, here we conducted an updated meta-analysis with the aim of providing a much more reliable conclusion on the significance of the association between VDR gene polymorphisms and T1DM risk.

Methods

This meta-analysis was conducted according to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines, including search strategy, inclusion and exclusion criteria, data extraction and quality assessment, and statistical analysis [26].

Search strategy

Three electronic databases (PubMed/MEDLINE, Scopus, and Web of Science) were systematically searched for studies regarding the association of VDR gene polymorphisms, including FokI (rs2228570) and/or TaqI (rs731236) and/or BsmI (rs1544410) and/or ApaI (rs7975232), and T1DM susceptibility, which were published before May 2020. The following combinations of search terms were used: (“T1D” OR “type 1 diabetes” OR “diabetes”) AND (“VDR” OR “vitamin D receptor”) AND (“polymorphisms” OR “SNP” OR “variation” OR “mutation”). The reference lists of review articles were also manually searched for additional pertinent publications. Original data in English language and human population studies were collected.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Eligible studies must meet the following criteria: a) All studies assessing the association of VDR gene polymorphisms and T1DM risk; b) All studies reporting sufficient data to calculate the odds ratio (OR) and its 95% confidence intervals (CIs); c) All studies with distinct case and control groups (case-control and cohort design). The exclusion criteria were: a) studies that their genotype or allele frequency could not be extracted; b) letters, non-English publications, animal studies, case reports, reviews, comments, book chapters, and abstracts; c) duplicate and republished studies. The application of these criteria recognized 39 studies eligible for the quantitative analysis.

Data extraction and quality assessment

According to a standardized extraction form, the following data were independently extracted by two reviewers: the author’s name, journal and year of publication, country of origin, ethnicity, number of case and control for each gender separately, genotype and allele frequencies in cases and healthy groups, mean or range of age, genotyping method, total sample size of cases and controls. The third reviewer finalized the extracted data, and potential discrepancies were resolved by consensus. For quality assessment of the included publications, the Newcastle-Ottawa Scale (NOS) was applied [27]. In this respect, studies with 0–3, 4–6 or 7–9 scores were, respectively, of low, moderate, and high-quality.

Statistical analysis

Deviation from Hardy–Weinberg equilibrium (HWE) for distribution of the allele frequencies was analyzed by χ2-test in control groups. The strength of association between VDR gene polymorphisms and T1DM susceptibility was estimated by calculating pooled OR and its 95% CI. Different comparison model for FokI, TaqI, BsmI, and ApaI were as follows: FokI; dominant model (ff + Ff vs. FF), recessive model (ff vs. Ff + FF), allelic model (f vs. F), homozygote (ff vs. FF), and heterozygote (Ff vs. FF): TaqI; dominant model (tt + Tt vs. TT), recessive model (tt vs. Tt + TT), allelic model (t vs. T), homozygote (tt vs. TT), and heterozygote (Tt vs. TT): BsmI; dominant model (bb + Bb vs. BB), recessive model (bb vs. Bb + BB), allelic model (b vs. B), homozygote (bb vs. BB), and heterozygote (Bb vs. BB): ApaI; dominant model (aa+Aa vs. AA), recessive model (aa vs. Aa+AA), allelic model (a vs. A), homozygote (aa vs. AA), and heterozygote (Aa vs. AA). The heterogeneity among studies was measured by the χ2 test-based Q statistic, and I2 value which quantify the degree of heterogeneity [28]. Accordingly, heterogeneity was considered significant if I2 values exceeded 50% or the Q statistic had a P value of less than 0.1 and random-effects model (DerSimonian–Laird approach) was carried out [29]. Otherwise, the fixed-effects model (Mantel–Haenszel approach) was performed for combination of data [30]. In order to assess the predefined sources of heterogeneity among included studies, subgroup analysis and meta-regression analysis based on year of population, and ethnicity were performed. Stability of our results was assessed by sensitivity analysis. Potential publication bias was estimated by Egger’s linear regression test, and also Begg’s test was employed to estimate the funnel plot asymmetry (P value< 0.05 considered statistically significant) [31, 32]. The data analyses were carried out using STATA (version 14.0; Stata Corporation, College Station, TX) and SPSS (version 23.0; SPSS, Inc. Chicago, IL).

Results

Study characteristics

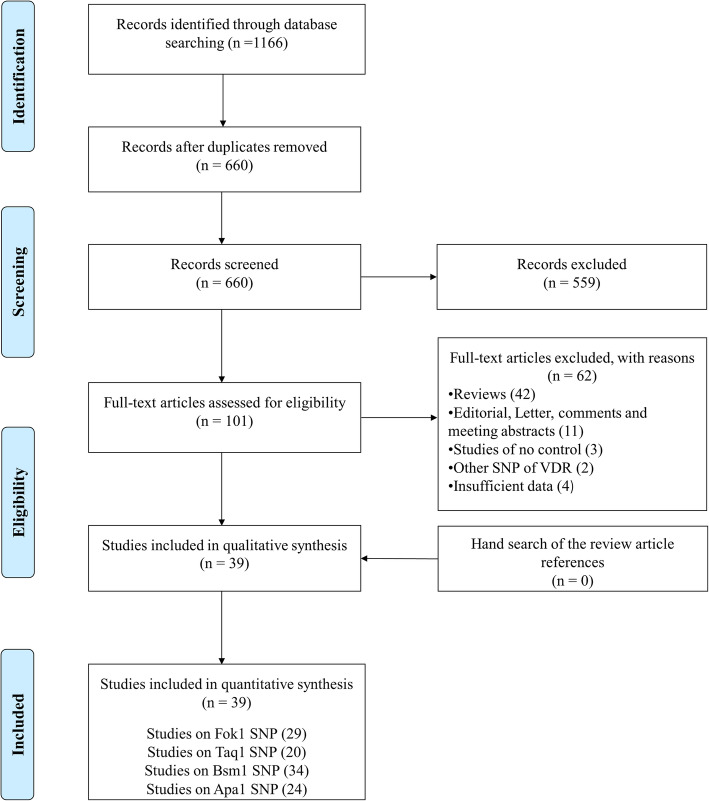

Regarding to aforementioned keywords, a total of 1116 studies were initially retrieved. Of these studies, 456 publications were duplicate, 559 and 62 publications excluded by title & abstract and full text examination, respectively. Finally, 39 studies qualified for quantitative analysis. It should be noted that while the latest meta-analysis by Tizaouia et al. [20] in 2014 included 23 studies, we performed the updated meta-analysis by adding 16 more articles. Also, no studies were found by hand search (Fig. 1). The eligible studies were published from 1998 to 2019 and had an overall good methodological quality with NOS scores ranging from 6 to 8. Polymerase chain reaction-restriction fragment length polymorphism (PCR- RFLP) and Taq-man were used by majority of included studies as genotyping method. Tables 1 and 2 summarized the characteristics and genotype frequency of the included studies.

Fig. 1.

Flow diagram of study selection process

Table 1.

Characteristics of studies included in meta-analysis of overall T1DM

| Study author | Year | Country | Ethnicity | Sex cases/controls | Total cases/control | Age case/control (Mean) | Genotyping method | Quality score |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| FokI (rs2228570) | ||||||||

| Ban et al. [33] | 2001 | Japan | Asian |

M = 50/60 F = 100/150 |

108 / 250 | 26.0 ± 3.8 / NR | RFLP-PCR | 7 |

| Fassbender et al. [34] | 2002 | Germany | European |

M = 42/33 F = 27/30 |

75 / 57 | 34.1 ± 11.1 / 33.5 ± 10.1 | RFLP-PCR | 6 |

| Gyorffy et al. [35] | 2002 | Hungary | European |

M = 57/50 F = 53/50 |

107 / 103 | 23.5 ± 5.11 / NR | RFLP-PCR | 7 |

| Turpeinen (Turku) et al. [36] | 2003 | Finland | European |

M = NR F=NR |

274 / 808 | NR / NR | Mini sequencing | 8 |

| Turpeinen (Tampere) et al. [36] | 2003 | Finland | European |

M = NR F=NR |

55 / 457 | NR / NR | Mini sequencing | 8 |

| Turpeinen (Oulu) et al. [36] | 2003 | Finland | European |

M = NR F=NR |

249 / 795 | NR / NR | Mini sequencing | 8 |

| Audi (barcellona) et al. [37] | 2004 | Spain | European |

M = 69/86 F = 153/122 |

155 / 275 | NR / NR | Mini sequencing | 7 |

| Audi (navarra) et al. [37] | 2004 | Spain | European |

M = 40/46 F = 58/58 |

86 / 116 | NR / NR | Mini sequencing | 7 |

| San Pedro et al. [38] | 2005 | Spain | European |

M = NR F=NR |

71 / 88 | 14.5 ± 9.9 / NR | RFLP-PCR | 6 |

| Zemunik et al. [39] | 2005 | Croatia | European |

M = 72/62 F=NR |

134 / 232 | 8.6 ± 4.3 / NR | RFLP-PCR | 7 |

| Capoluongo et al. [40] | 2006 | Italy | European |

M = 135/111 F = 135/111 |

246 / 246 | 39.3 ± 11.1 / 39.6 ± 9.1 | RFLP-PCR | 8 |

| Lemos et al. [41] | 2008 | Portugal | European |

M = 113/94 F = 143/106 |

207 / 249 | 27.5 ± 10.2 / 36.8 ± 13.8 | RFLP-PCR | 8 |

| Israni et al. [42] | 2009 | India | Asian |

M = 131/135 F = 116/81 |

236 / 197 | 15.1 ± 7.30 / 30.1 ± 10.2 | RFLP-PCR | 7 |

| Mory et al. [43] | 2009 | Brazil | American |

M = NR F=NR |

177 / 182 | 17.2 ± 5.4 / 12.2 ± 8.1 | RFLP-PCR | 7 |

| Panierakis et al. [15] | 2009 | Greece | European |

M = NR F = 52/44 |

100 / 96 | NR / NR | Mini sequencing | 6 |

| Yavuz et al. [44] | 2011 | turkey | European |

M = 60/57 F = 73/61 |

117 / 134 | 27.6 ± 7.3 / 26.2 ± 5.3 | RFLP-PCR | 6 |

| Yokota et al. [45] | 2012 | Japan | Asian |

M = NR F=NR |

108 / 220 | NR / NR | NR | 7 |

| Bonakdaran et al. [46] | 2012 | Iran | Asian |

M = 28/41 F = 19/26 |

69 / 45 | NR / NR | RFLP-PCR | 6 |

| Sahin et al. [47] | 2012 | Turkey | European |

M = NR F=NR |

85 / 80 | NR / NR | NR | 6 |

| Mohammadnejad et al. [48] | 2012 | Iran | Asian |

M = 32/55 F = 50/50 |

87 / 100 | 27.93 ± 10.86 / 28.58 ± 7.40 | RFLP-PCR | 6 |

| Vedralova et al. [49] | 2012 | Czech | European |

M = NR F=NR |

116 / 113 | 67.0 ± 12.44 / 45.0 ± 7.31 | RFLP-PCR | 6 |

| Greer et al. [50] | 2012 | Australia | Australian |

M = NR F=NR |

50 / 55 | NR / NR | RFLP-PCR | 6 |

| Hamed et al. [51] | 2013 | Egypt | African |

M = 64/68 F = 18/22 |

132 / 40 | 8.5 ± 3.3 / 9.0 ± 1.5 | RFLP-PCR | 6 |

| Abd-Allah et al. [52] | 2014 | Egypt | African |

M = 42/78 F = 42/78 |

120 / 120 | 11.7 ± 2.8 / 11.1 ± 2.6 | RFLP-PCR | 7 |

| Kafoury et al. [53] | 2014 | Egypt | African |

M = 25/35 F=NR |

60 / 60 | 11.2 ± 3.7 / 27.2 ± 6.4 | RFLP-PCR | 6 |

| Nasreen et al. [54] | 2016 | Pakistan | Asian |

M = 25/19 F = 23/21 |

44 / 44 | 14.81 ± 2.7 / 17.92 ± 2.8 | RFLP-PCR | 6 |

| Mukhtar et al. [55] | 2017 | Pakistan | Asian |

M = NR F=NR |

102 / 100 | 13/2 / 13/8 | RFLP-PCR | 6 |

| Ali et al. [56] | 2018 | Saudi Arabia | Asian |

M = 54/46 F = 43/59 |

100 / 102 | 10.33 ± 3.15 / > 35 | RFLP-PCR | 7 |

| Rasoul et al. [57] | 2019 | Kuwait | Asian |

M = NR F=NR |

253 / 214 | 8.5 ± 5.5 / 8.9 ± 5.2 | RFLP-PCR | 8 |

| TaqI (rs731236) | ||||||||

| Chang et al. [58] | 2000 | China | Asian |

M = 71/86 F = 156/92 |

157 /248 | 23.5 ± 5.11 / 32.4 ± 6.6 | RFLP-PCR | 8 |

| Fassbender et al. [34] | 2002 | Germany | European |

M = 57/50 F = 53/50 |

75 /57 | 5.8 ± 2.3 / NR | RFLP-PCR | 6 |

| Gyorffy et al. [35] | 2002 | Hungary, | European |

M = 57/50 F = 53/50 |

107 / 103 | 23.5 ± 5.11 / NR | RFLP-PCR | 7 |

| Skrabic et al. [59] | 2003 | Croatia | European |

M = 72/62 F = 60/72 |

134 / 132 | 8.69 ± 4.3 / 8.24 ± 4.9 | RFLP-PCR | 7 |

| Bianco et al. [60] | 2004 | Italy | European |

M = NR F=NR |

31 / 36 | NR / NR | RFLP-PCR | 6 |

| San Pedro et al. [38] | 2005 | Spain | European |

M = NR F=NR |

71 / 88 | 14.5 ± 9.9 / NR | RFLP-PCR | 6 |

| Garcia et al. [61] | 2007 | Chile | American |

M = 120/96 F = 106/97 |

216 / 203 | 9.3 ± 4.2 / 10.3 ± 2.5 | RFLP-PCR | 8 |

| Lemos et al. [41] | 2008 | Portugal | European |

M = NR F=NR |

205 / 232 | 27.5 ± 10.2 / 36.8 ± 13.8 | RFLP-PCR | 8 |

| Israni et al. [42] | 2009 | India | Asian |

M = 131/135 F = 116/81 |

236 / 197 | 15.1 ± 7.30 / 30.1 ± 10.2 | RFLP-PCR | 7 |

| Panierakis et al. [15] | 2009 | Greece | European |

M = NR F = 52/44 |

100 / 96 | NR / NR | Mini sequencing | 6 |

| Yavuz et al. [44] | 2011 | Turkey | European |

M = 60/57 F = 73/61 |

117 / 134 | 27.6 ± 7.3 / 26.2 ± 5.3 | RFLP-PCR | 6 |

| Bonakdaran et al. [46] | 2012 | Iran | Asian |

M = 28/41 F = 19/26 |

69 / 45 | NR / NR | RFLP-PCR | 6 |

| Mohammadnejad et al. [48] | 2012 | Iran | Asian |

M = 32/55 F = 50/50 |

87 / 100 | 27.93 ± 10.86 / 28.58 ± 7.40 | RFLP-PCR | 6 |

| Greer et al. [50] | 2012 | Australia | Australian |

M = NR F=NR |

50 / 55 | NR / NR | RFLP-PCR | 6 |

| Abd-Allah et al. [52] | 2014 | Egypt | African |

M = 42/78 F = 42/78 |

120 / 120 | 11.7 ± 2.8 / 11.1 ± 2.6 | RFLP-PCR | 7 |

| Cheon et al. [62] | 2015 | Korea | Asian |

M = 35/46 F = 53/60 |

81 / 113 | 10.28 ± 3.73 / 9.98 ± 3.56 | RFLP-PCR | 6 |

| Khalid et al. [63] | 2016 | Saudi Arabia | Asian |

M = NR F=NR |

100 / 50 | 11.48 ± 3.39 / 9.50 ± 4.23 | RFLP-PCR | 6 |

| Iyer et al. [64] | 2017 | Saudi Arabia | Asian |

M = 25/25 F = 25/25 |

50 / 50 | 25.37 ± 4.07 / 23.44 ± 5.38 | RFLP-PCR | 6 |

| Rasoul et al. [57] | 2019 | Kuwait | Asian |

M = NR F=NR |

253 / 214 | 8.5 ± 5.5 / 8.9 ± 5.2 | RFLP-PCR | 8 |

| Ahmed et al. [65] | 2019 | Egypt | African |

M = 24/25 F = 26/25 |

50 / 50 | 11.16 ± 3.27 / 10.97 ± 2.77 | RFLP-PCR | 6 |

| BsmI (rs1544410) | ||||||||

| Hauache et al. [66] | 1998 | Brazil | American |

M = NR F = 31/63 |

78 / 94 | 15.5 ± 6.0 / 49 ± 11 | RFLP-PCR | 6 |

| Chang et al. [58] | 2000 | China | Asian |

M = 71/86 F = 156/92 |

157 / 248 | 23.5 ± 5.11 / 32.4 ± 6.6 | RFLP-PCR | 8 |

| Fassbender et al. [34] | 2002 | Germany | European |

M = 57/50 F = 53/50 |

75 / 57 | 5.8 ± 2.3 / NR | RFLP-PCR | 6 |

| Gyorffy et al. [35] | 2002 | Hungary | European |

M = 57/50 F = 53/50 |

107 / 103 | 23.5 ± 5.11 / NR | RFLP-PCR | 7 |

| Motohashi et al. [67] | 2002 | Japan | Asian |

M = 96/107 F = 101/121 |

203 / 222 | 34.6 ± 16.9 / 44.4 ± 13.7 | RFLP-PCR | 8 |

| Skrabic et al. [59] | 2003 | Croatia | European |

M = 72/62 F = 60/72 |

134 / 132 | 8.69 ± 4.3 / 8.24 ± 4.9 | RFLP-PCR | 7 |

| Turpeinen (Turku) et al. [36] | 2003 | Finland | European |

M = NR F=NR |

220 / 844 | NR / NR | Mini sequencing | 8 |

| Turpeinen (Tampere) et al. [36] | 2003 | Finland | European |

M = NR F=NR |

58 / 1175 | NR / NR | Mini sequencing | 8 |

| Turpeinen (Oulu) et al. [36] | 2003 | Finland | European |

M = NR F=NR |

226 / 818 | NR / NR | Mini sequencing | 8 |

| Audi (barcellona) et al. [37] | 2004 | Spain | European |

M = 69/84 F = 153/121 |

153 / 274 | NR / NR | Mini sequencing | 7 |

| Audi (navarra) et al. [37] | 2004 | Spain | European |

M = 40/49 F = 58/58 |

89 /116 | NR / NR | Mini sequencing | 7 |

| Bianco et al. [60] | 2004 | Italy | European |

M = NR F=NR |

31 / 36 | NR / NR | RFLP-PCR | 6 |

| San Pedro et al. [38] | 2005 | Spain | European |

M = NR F=NR |

71 / 88 | 14.5 ± 9.9 / NR | RFLP-PCR | 6 |

| Capoluongo et al. [40] | 2006 | Italy | European |

M = 135/111 F = 135/111 |

246 / 246 | 39.3 ± 11.1 / 39.6 ± 9.1 | RFLP-PCR | 8 |

| Garcia et al. [61] | 2007 | Chile | American |

M = NR F = 106/97 |

208 / 203 | 9.3 ± 4.2 / 10.3 ± 2.5 | RFLP-PCR | 8 |

| Lemos et al. [41] | 2008 | Portugal | European |

M = NR F=NR |

207 / 248 | 27.5 ± 10.2 / 36.8 ± 13.8 | RFLP-PCR | 8 |

| Shimada et al. [68] | 2008 | Japan | Asian |

M = 357/417 F=NR |

774 / 599 | 29/8 / NR | RFLP-PCR | 8 |

| Israni et al. [42] | 2009 | India | Asian |

M = 131/135 F = 116/81 |

236 / 197 | 15.1 ± 7.30 / 30.1 ± 10.2 | RFLP-PCR | 7 |

| Mory et al. [43] | 2009 | Brazil | American |

M = NR F=NR |

177 / 182 | 17.2 ± 5.4 / 12.2 ± 8.1 | RFLP-PCR | 7 |

| Panierakis et al. [15] | 2009 | Greece | European |

M = NR F = 52/44 |

100 / 96 | NR / NR | Mini sequencing | 6 |

| Yavuz et al. [44] | 2011 | Turkey | European |

M = 60/57 F = 73/61 |

117 / 134 | 27.6 ± 7.3 / 26.2 ± 5.3 | RFLP-PCR | 6 |

| Tawfeek et al. [69] | 2011 | Arabic Saudi | Asian |

M = 0/30 F = 0/14 |

30 / 14 | 35.7 ± 5.33 / 33.2 ± 4.06 | RFLP-PCR | 6 |

| Bonakdaran et al. [46] | 2012 | Iran | Asian |

M = 28/41 F = 19/26 |

69 / 45 | NR / NR | RFLP-PCR | 6 |

| Vedralova et al. [49] | 2012 | Czech | European |

M = NR F=NR |

104 / 83 | 67.0 ± 12.44 / 45.0 ± 7.31 | RFLP-PCR | 6 |

| Mohammadnejad et al. [48] | 2012 | Iran | Asian |

M = 32/55 F = 50/50 |

87 / 100 | 27.93 ± 10.86 / 28.58 ± 7.40 | RFLP-PCR | 6 |

| Moubarak et al. [70] | 2013 | Syria | Asian |

M = 25/30 F = 24/26 |

55 / 50 | 13.75 ± 6.91 / 39.86 ± 11.66 | RFLP-PCR | 6 |

| Abd-Allah et al. [52] | 2014 | Egypt | Africian |

M = 42/78 F = 42/78 |

120 / 120 | 11.7 ± 2.8 / 11.1 ± 2.6 | RFLP-PCR | 7 |

| Kafoury et al. [53] | 2014 | Egypt | Africian |

M = 25/35 F=NR |

60 / 56 | 11.2 ± 3.7 / 27.2 ± 6.4 | RFLP-PCR | 6 |

| Cheon et al. [62] | 2015 | Korea | Asian |

M = 35/46 F = 53/60 |

81 / 113 | 10.28 ± 3.73 / 9.98 ± 3.56 | RFLP-PCR | 6 |

| Khalid et al. [63] | 2016 | Saudi Arabia | Asian |

M = NR F=NR |

100 / 50 | 11.48 ± 3.39 / 9.50 ± 4.23 | RFLP-PCR | 6 |

| Iyer et al. [64] | 2017 | Saudi Arabia | Asian |

M = 25/25 F = 25/25 |

50 / 50 | 25.37 ± 4.07 / 23.44 ± 5.38 | RFLP-PCR | 6 |

| Ali et al. [56] | 2018 | Saudi Arabia | Asian |

M = 54/46 F = 43/59 |

100 / 102 | 10.33 ± 3.15 / > 35 | RFLP-PCR | 7 |

| Rasoul et al. [57] | 2019 | Kuwait | Asian |

M = NR F=NR |

253 / 214 | 8.5 ± 5.5 / 8.9 ± 5.2 | RFLP-PCR | 8 |

| Ahmed et al. [65] | 2019 | Egypt | African |

M = 24/25 F = 26/25 |

50 / 50 | 11.16 ± 3.27 / 10.97 ± 2.77 | RFLP-PCR | 6 |

| ApaI (rs7975232) | ||||||||

| Chang et al. [58] | 2000 | China | Asian |

M = 71/86 F = 156/92 |

157 / 248 | 23.5 ± 5.11 / 32.4 ± 6.6 | RFLP-PCR | 8 |

| Gyorffy et al. [35] | 2002 | Hungary | European |

M = 57/50 F = 53/50 |

107 / 103 | 23.5 ± 5.11 / NR | RFLP-PCR | 7 |

| Skrabic et al. [59] | 2003 | Croatia | European |

M = 72/62 F = 60/72 |

134 / 132 | 8.69 ± 4.3 / 8.24 ± 4.9 | RFLP-PCR | 7 |

| Turpeinen (Turku) et al. [36] | 2003 | Finland | European |

M = NR F=NR |

198 / 797 | NR / NR | Mini sequencing | 8 |

| Turpeinen (Tampere) et al. [36] | 2003 | Finland | European |

M = NR F=NR |

56 / 450 | NR / NR | Mini sequencing | 8 |

| Turpeinen (Oulu) et al. [36] | 2003 | Finland | European |

M = NR F=NR |

239 / 843 | NR / NR | Mini sequencing | 8 |

| Bianco et al. [60] | 2004 | Italy | European |

M = NR F=NR |

31 / 36 | NR / NR | RFLP-PCR | 6 |

| San Pedro et al. [38] | 2005 | Spain | European |

M = NR F=NR |

71 / 88 | 14.5 ± 9.9 / NR | RFLP-PCR | 6 |

| Garcia et al. [61] | 2007 | Chile | American |

M = NR F = 106/97 |

213 / 203 | 9.3 ± 4.2 / 10.3 ± 2.5 | RFLP-PCR | 8 |

| Lemos et al. [41] | 2008 | Portugal | European |

M = NR F=NR |

205 / 232 | 27.5 ± 10.2 / 36.8 ± 13.8 | RFLP-PCR | 8 |

| Israni et al. [42] | 2009 | India | Asian |

M = 131/135 F = 116/81 |

236 / 197 | 15.1 ± 7.30 / 30.1 ± 10.2 | RFLP-PCR | 7 |

| Panierakis et al. [15] | 2009 | Greece | European |

M = NR F = 52/44 |

100 / 96 | NR / NR | Mini sequencing | 6 |

| Yavuz et al. [44] | 2011 | Turkey | European |

M = 60/57 F = 73/61 |

117 / 136 | 27.6 ± 7.3 / 26.2 ± 5.3 | RFLP-PCR | 6 |

| Bonakdaran et al. [46] | 2012 | Iran | Asian |

M = 28/41 F = 19/26 |

69 / 45 | NR / NR | RFLP-PCR | 6 |

| Mohammadnejad et al. [48] | 2012 | Iran | Asian |

M = 32/55 F = 50/50 |

87 / 100 | 27.93 ± 10.86 / 28.58 ± 7.40 | RFLP-PCR | 6 |

| Greer et al. [50] | 2012 | Australia | Australian |

M = NR F=NR |

50 / 55 | NR / NR | RFLP-PCR | 6 |

| Abd-Allah et al. [52] | 2014 | Egypt | African |

M = 42/78 F = 42/78 |

120 / 120 | 11.7 ± 2.8 / 11.1 ± 2.6 | RFLP-PCR | 7 |

| Cheon et al. [62] | 2015 | Korea | Asian |

M = 35/46 F = 53/60 |

81 / 113 | 10.28 ± 3.73 / 9.98 ± 3.56 | RFLP-PCR | 6 |

| Khalid et al. [63] | 2016 | Saudi Arabia | Asian |

M = NR F=NR |

100 / 50 | 11.48 ± 3.39 / 9.50 ± 4.23 | RFLP-PCR | 6 |

| Nasreen et al. [54] | 2016 | Pakistan | Asian |

M = 25/19 F = 23/21 |

44 / 44 | 14.81 ± 2.7 / 17.92 ± 2.8 | RFLP-PCR | 6 |

| Iyer et al. [64] | 2017 | Saudi Arabia | Asian |

M = 25/25 F = 25/25 |

50 / 50 | 25.37 ± 4.07 / 23.44 ± 5.38 | RFLP-PCR | 6 |

| Mukhtar et al. [55] | 2017 | Pakistan | Asian |

M = NR F=NR |

102 / 100 | 13/2 / 13/8 | RFLP-PCR | 6 |

| Rasoul et al. [57] | 2019 | Kuwait | Asian |

M = NR F=NR |

252 / 214 | 8.5 ± 5.5 / 8.9 ± 5.2 | RFLP-PCR | 8 |

| Ahmed et al. [65] | 2019 | Egypt | African |

M = 24/25 F = 26/25 |

50 / 50 | 11.16 ± 3.27 / 10.97 ± 2.77 | RFLP-PCR | 6 |

NR not reported, M male, F female

Table 2.

Distribution of genotype and allele among T1DM patients and controls

| Study author | T1DM cases | Healthy control | P-HWE | MAF | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| FF | Ff | ff | F | f | FF | Ff | Ff | F | f | |||

| FokI (rs2228570) | ||||||||||||

| Ban et al. [33] | 50 | 52 | 6 | 152 | 64 | 82 | 138 | 30 | 302 | 198 | 0.01 | 0.396 |

| Fassbender et al. [34] | 35 | 30 | 10 | 100 | 50 | 19 | 30 | 8 | 68 | 46 | 0.48 | 0.403 |

| Gyorffy et al. [35] | 32 | 56 | 19 | 120 | 94 | 34 | 47 | 22 | 115 | 91 | 0.44 | 0.441 |

| Turpeinen (Turku) et al. [36] | 50 | 150 | 74 | 250 | 298 | 102 | 414 | 292 | 618 | 998 | 0.01 | 0.617 |

| Turpeinen (Tampere) et al. [36] | 7 | 28 | 20 | 42 | 68 | 61 | 226 | 170 | 348 | 566 | 0.29 | 0.619 |

| Turpeinen (Oulu) et al. [36] | 37 | 114 | 98 | 188 | 310 | 93 | 360 | 342 | 546 | 1044 | 0.9 | 0.656 |

| Audi (barcellona) et al. [37] | 69 | 68 | 18 | 206 | 104 | 105 | 142 | 28 | 352 | 198 | 0.04 | 0.36 |

| Audi (navarra) et al. [37] | 35 | 45 | 6 | 115 | 57 | 41 | 53 | 22 | 135 | 97 | 0.51 | 0.418 |

| San Pedro et al. [38] | 31 | 35 | 5 | 97 | 45 | 41 | 39 | 8 | 121 | 55 | 0.76 | 0.312 |

| Zemunik et al. [39] | 42 | 63 | 29 | 147 | 121 | 73 | 136 | 23 | 282 | 182 | < 0.001 | 0.392 |

| Capoluongo et al. [40] | 89 | 112 | 45 | 290 | 202 | 91 | 127 | 28 | 309 | 183 | 0.09 | 0.371 |

| Lemos et al. [41] | 81 | 101 | 25 | 263 | 151 | 97 | 114 | 38 | 308 | 190 | 0.63 | 0.381 |

| Israni et al. [42] | 142 | 79 | 15 | 363 | 109 | 116 | 76 | 5 | 308 | 86 | 0.06 | 0.218 |

| Mory et al. [43] | 80 | 81 | 16 | 241 | 113 | 91 | 67 | 24 | 249 | 115 | 0.04 | 0.315 |

| Panierakis et al. [15] | 50 | 43 | 7 | 143 | 57 | 64 | 31 | 1 | 159 | 33 | 0.18 | 0.171 |

| Yavuz et al. [44] | 61 | 46 | 10 | 168 | 66 | 60 | 63 | 11 | 183 | 85 | 0.32 | 0.317 |

| Yokota et al. [45] | 50 | 46 | 12 | 146 | 70 | 59 | 20 | 141 | 138 | 302 | < 0.001 | 0.686 |

| Bonakdaran et al. [46] | 38 | 25 | 6 | 101 | 37 | 18 | 20 | 7 | 56 | 34 | 0.71 | 0.377 |

| Sahin et al. [47] | 54 | 31 | 0 | 139 | 31 | 43 | 28 | 9 | 114 | 46 | 0.19 | 0.287 |

| Mohammadnejad et al. [48] | 49 | 33 | 5 | 131 | 43 | 55 | 40 | 5 | 150 | 50 | 0.5 | 0.25 |

| Vedralova et al. [49] | 38 | 60 | 18 | 136 | 96 | 25 | 76 | 12 | 126 | 100 | < 0.001 | 0.442 |

| Greer et al. [50] | 21 | 21 | 8 | 63 | 37 | 28 | 22 | 5 | 78 | 32 | 0.82 | 0.29 |

| Hamed et al. [51] | 24 | 92 | 16 | 140 | 124 | 8 | 28 | 4 | 44 | 36 | 0.008 | 0.45 |

| Abd-Allah et al. [52] | 58 | 50 | 12 | 166 | 74 | 78 | 38 | 4 | 194 | 46 | 0.8 | 0.191 |

| Kafoury et al. [53] | 23 | 21 | 16 | 67 | 53 | 41 | 12 | 7 | 94 | 26 | 0.001 | 0.216 |

| Nasreen et al. [54] | 32 | 12 | 0 | 76 | 12 | 25 | 19 | 0 | 69 | 19 | 0.06 | 0.215 |

| Mukhtar et al. [55] | 84 | 13 | 5 | 181 | 23 | 100 | 0 | 0 | 200 | 0 | < 0.001 | 0 |

| Ali et al. [56] | 64 | 33 | 3 | 161 | 39 | 79 | 21 | 2 | 179 | 25 | 0.66 | 0.122 |

| Rasoul et al. [57] | 178 | 30 | 45 | 386 | 120 | 146 | 67 | 1 | 359 | 69 | 0.02 | 0.161 |

| Study author | T1DM cases | Healthy control | P-HWE | MAF | ||||||||

| TT | Tt | tt | T | t | TT | Tt | tt | T | t | |||

| TaqI (rs731236) | ||||||||||||

| Chang et al. [58] | 142 | 15 | 0 | 299 | 15 | 233 | 14 | 1 | 480 | 16 | 0.13 | 0.032 |

| Fassbender et al. [34] | 34 | 31 | 10 | 99 | 51 | 19 | 20 | 18 | 58 | 56 | 0.02 | 0.491 |

| Gyorffy et al. [35] | 46 | 34 | 27 | 126 | 88 | 42 | 27 | 34 | 111 | 95 | < 0.001 | 0.461 |

| Skrabic et al. [59] | 54 | 55 | 25 | 163 | 105 | 48 | 72 | 12 | 168 | 96 | 0.04 | 0.363 |

| Bianco et al. [60] | 10 | 18 | 3 | 38 | 24 | 11 | 20 | 5 | 42 | 30 | 0.39 | 0.416 |

| San Pedro et al. [38] | 24 | 36 | 11 | 84 | 58 | 31 | 43 | 14 | 105 | 71 | 0.88 | 0.403 |

| Garcia et al. [61] | 115 | 79 | 22 | 309 | 123 | 121 | 69 | 13 | 311 | 95 | 0.46 | 0.233 |

| Lemos et al. [41] | 70 | 94 | 41 | 234 | 176 | 91 | 95 | 46 | 277 | 187 | 0.02 | 0.403 |

| Israni et al. [42] | 91 | 112 | 33 | 294 | 178 | 80 | 98 | 19 | 258 | 136 | 0.15 | 0.345 |

| Panierakis et al. [15] | 34 | 59 | 7 | 127 | 73 | 10 | 64 | 22 | 84 | 108 | < 0.001 | 0.562 |

| Yavuz et al. [44] | 37 | 58 | 22 | 132 | 102 | 41 | 66 | 27 | 148 | 120 | 0.96 | 0.447 |

| Bonakdaran et al. [46] | 34 | 28 | 7 | 96 | 42 | 20 | 17 | 8 | 57 | 33 | 0.21 | 0.366 |

| Mohammadnejad et al. [48] | 32 | 52 | 3 | 116 | 58 | 59 | 41 | 0 | 159 | 41 | < 0.001 | 0.205 |

| Greer et al. [50] | 18 | 26 | 6 | 62 | 38 | 26 | 24 | 5 | 76 | 34 | 0.87 | 0.309 |

| Abd-Allah et al. [52] | 42 | 66 | 12 | 150 | 90 | 33 | 69 | 18 | 135 | 105 | 0.06 | 0.437 |

| Cheon et al. [62] | 66 | 15 | 0 | 147 | 15 | 105 | 8 | 0 | 218 | 8 | 0.69 | 0.035 |

| Khalid et al. [63] | 63 | 22 | 15 | 148 | 52 | 19 | 16 | 15 | 54 | 46 | 0.01 | 0.46 |

| Iyer et al. [64] | 19 | 14 | 17 | 52 | 48 | 16 | 16 | 18 | 48 | 52 | 0.01 | 0.52 |

| Rasoul et al. [57] | 96 | 96 | 61 | 288 | 218 | 156 | 36 | 22 | 348 | 80 | < 0.001 | 0.186 |

| Ahmed et al. [65] | 0 | 42 | 8 | 42 | 58 | 0 | 40 | 10 | 40 | 60 | < 0.001 | 0.6 |

| Study author | T1DM cases | Healthy control | P-HWE | MAF | ||||||||

| BB | Bb | bb | B | b | BB | Bb | bb | B | b | |||

| BsmI (rs1544410) | ||||||||||||

| Hauache et al. [66] | 13 | 39 | 26 | 65 | 91 | 12 | 43 | 39 | 67 | 121 | 0.97 | 0.643 |

| Chang et al. [58] | 4 | 16 | 137 | 24 | 290 | 1 | 16 | 231 | 18 | 478 | 0.22 | 0.963 |

| Fassbender et al. [34] | 14 | 35 | 26 | 63 | 87 | 18 | 25 | 14 | 61 | 53 | 0.37 | 0.464 |

| Gyorffy et al. [35] | 19 | 46 | 42 | 84 | 130 | 16 | 53 | 34 | 85 | 121 | 0.53 | 0.587 |

| Motohashi et al. [67] | 12 | 64 | 127 | 88 | 318 | 1 | 49 | 172 | 51 | 393 | 0.2 | 0.885 |

| Skrabic et al. [59] | 24 | 58 | 52 | 106 | 162 | 17 | 74 | 41 | 108 | 156 | 0.06 | 0.59 |

| Turpeinen (Turku) et al. [36] | 97 | 97 | 26 | 291 | 149 | 354 | 388 | 102 | 1096 | 592 | 0.78 | 0.35 |

| Turpeinen (Tampere) et al. [36] | 29 | 22 | 7 | 80 | 36 | 533 | 488 | 154 | 1554 | 796 | 0.01 | 0.338 |

| Turpeinen (Oulu) et al. [36] | 90 | 103 | 33 | 283 | 169 | 403 | 305 | 110 | 1111 | 525 | < 0.001 | 0.32 |

| Audi (barcellona) et al. [37] | 21 | 73 | 59 | 115 | 191 | 46 | 147 | 81 | 239 | 309 | 0.13 | 0.563 |

| Audi (navarra) et al. [37] | 20 | 43 | 26 | 83 | 95 | 19 | 53 | 44 | 91 | 141 | 0.65 | 0.607 |

| Bianco et al. [60] | 13 | 14 | 4 | 40 | 22 | 14 | 17 | 5 | 45 | 27 | 0.96 | 0.375 |

| San Pedro et al. [38] | 15 | 40 | 16 | 70 | 72 | 17 | 44 | 27 | 78 | 98 | 0.9 | 0.556 |

| Capoluongo et al. [40] | 62 | 125 | 59 | 249 | 243 | 61 | 122 | 63 | 244 | 248 | 0.89 | 0.504 |

| Garcia et al. [61] | 21 | 110 | 77 | 152 | 264 | 14 | 74 | 115 | 102 | 304 | 0.65 | 0.748 |

| Lemos et al. [41] | 43 | 96 | 68 | 182 | 232 | 56 | 107 | 85 | 219 | 277 | 0.04 | 0.558 |

| Shimada et al. [68] | 32 | 165 | 577 | 229 | 1319 | 7 | 121 | 471 | 135 | 1063 | 0.8 | 0.887 |

| Israni et al. [42] | 79 | 120 | 37 | 278 | 194 | 56 | 94 | 47 | 206 | 188 | 0.53 | 0.477 |

| Mory et al. [43] | 60 | 57 | 60 | 177 | 177 | 38 | 74 | 70 | 150 | 214 | 0.62 | 0.587 |

| Panierakis et al. [15] | 23 | 57 | 20 | 103 | 97 | 38 | 43 | 15 | 119 | 73 | 0.62 | 0.38 |

| Yavuz et al. [44] | 20 | 57 | 40 | 97 | 137 | 14 | 59 | 61 | 87 | 181 | 0.96 | 0.675 |

| Tawfeek et al. [69] | 3 | 18 | 9 | 24 | 36 | 1 | 8 | 5 | 10 | 18 | 0.36 | 0.642 |

| Bonakdaran et al. [46] | 14 | 26 | 29 | 54 | 84 | 16 | 11 | 18 | 43 | 47 | < 0.001 | 0.522 |

| Vedralova et al. [49] | 43 | 47 | 14 | 133 | 75 | 30 | 33 | 20 | 93 | 73 | 0.07 | 0.439 |

| Mohammadnejad et al. [48] | 11 | 36 | 40 | 58 | 116 | 9 | 45 | 46 | 63 | 137 | 0.66 | 0.685 |

| Moubarak et al. [70] | 7 | 25 | 23 | 39 | 71 | 14 | 26 | 10 | 54 | 46 | 0.74 | 0.46 |

| Abd-Allah et al. [52] | 27 | 68 | 25 | 122 | 118 | 48 | 52 | 20 | 148 | 92 | 0.36 | 0.383 |

| Kafoury et al. [53] | 8 | 13 | 39 | 29 | 91 | 4 | 11 | 41 | 19 | 93 | 0.02 | 0.83 |

| Cheon et al. [62] | 0 | 13 | 68 | 13 | 149 | 1 | 4 | 108 | 6 | 220 | < 0.001 | 0.973 |

| Khalid et al. [63] | 51 | 32 | 17 | 134 | 66 | 19 | 21 | 10 | 59 | 41 | 0.35 | 0.41 |

| Iyer et al. [64] | 8 | 12 | 30 | 28 | 72 | 26 | 12 | 12 | 64 | 36 | < 0.001 | 0.36 |

| Ali et al. [56] | 30 | 45 | 25 | 105 | 95 | 62 | 28 | 12 | 152 | 52 | 0.005 | 0.254 |

| Rasoul et al. [57] | 141 | 83 | 29 | 365 | 141 | 120 | 66 | 28 | 306 | 122 | < 0.001 | 0.285 |

| Ahmed et al. [65] | 8 | 35 | 7 | 51 | 49 | 32 | 18 | 0 | 82 | 18 | < 0.001 | 0.19 |

| Study author | T1DM cases | Healthy control | P-HWE | MAF | ||||||||

| AA | Aa | aa | A | a | AA | Aa | aa | A | a | |||

| ApaI (rs7975232) | ||||||||||||

| Chang et al. [58] | 16 | 76 | 65 | 108 | 206 | 13 | 105 | 130 | 131 | 365 | 0.16 | 0.735 |

| Gyorffy et al. [35] | 23 | 27 | 57 | 73 | 141 | 33 | 45 | 25 | 111 | 95 | 0.21 | 0.461 |

| Skrabic et al. [59] | 66 | 52 | 16 | 184 | 84 | 51 | 66 | 15 | 168 | 96 | 0.35 | 0.363 |

| Turpeinen (Turku) et al. [36] | 35 | 106 | 57 | 176 | 220 | 152 | 441 | 204 | 745 | 849 | 0.001 | 0.532 |

| Turpeinen (Tampere) et al. [36] | 13 | 23 | 20 | 49 | 63 | 69 | 229 | 152 | 367 | 533 | 0.25 | 0.592 |

| Turpeinen (Oulu) et al. [36] | 43 | 115 | 81 | 201 | 277 | 165 | 389 | 289 | 719 | 967 | 0.09 | 0.573 |

| Bianco et al. [60] | 18 | 11 | 2 | 47 | 15 | 11 | 20 | 5 | 42 | 30 | 0.39 | 0.416 |

| San Pedro et al. [38] | 15 | 37 | 19 | 67 | 75 | 28 | 43 | 17 | 99 | 77 | 0.94 | 0.437 |

| Garcia et al. [61] | 54 | 115 | 44 | 223 | 203 | 43 | 125 | 35 | 211 | 195 | < 0.001 | 0.48 |

| Lemos et al. [41] | 55 | 100 | 50 | 210 | 200 | 68 | 101 | 63 | 237 | 227 | 0.04 | 0.489 |

| Israni et al. [42] | 85 | 133 | 18 | 303 | 169 | 60 | 110 | 27 | 230 | 164 | 0.03 | 0.416 |

| Panierakis et al. [15] | 37 | 57 | 6 | 131 | 69 | 23 | 58 | 15 | 104 | 88 | 0.03 | 0.458 |

| Yavuz et al. [44] | 36 | 58 | 23 | 130 | 104 | 35 | 70 | 31 | 140 | 132 | 0.72 | 0.485 |

| Bonakdaran et al. [46] | 13 | 52 | 4 | 78 | 60 | 18 | 26 | 1 | 62 | 28 | 0.01 | 0.311 |

| Mohammadnejad et al. [48] | 27 | 48 | 12 | 102 | 72 | 27 | 57 | 16 | 111 | 89 | 0.12 | 0.445 |

| Greer et al. [50] | 15 | 24 | 11 | 54 | 46 | 12 | 32 | 11 | 56 | 54 | 0.22 | 0.49 |

| Abd-Allah et al. [52] | 44 | 65 | 11 | 153 | 87 | 36 | 68 | 16 | 140 | 100 | 0.06 | 0.416 |

| Cheon et al. [62] | 5 | 32 | 44 | 42 | 120 | 9 | 34 | 70 | 52 | 174 | 0.1 | 0.769 |

| Khalid et al. [63] | 49 | 44 | 7 | 142 | 58 | 26 | 21 | 3 | 73 | 27 | 0.64 | 0.27 |

| Nasreen et al. [54] | 14 | 25 | 5 | 53 | 35 | 15 | 25 | 4 | 55 | 33 | 0.15 | 0.375 |

| Iyer et al. [64] | 17 | 16 | 17 | 50 | 50 | 18 | 16 | 16 | 52 | 48 | 0.01 | 0.48 |

| Mukhtar et al. [55] | 43 | 26 | 33 | 112 | 92 | 86 | 0 | 14 | 172 | 28 | < 0.001 | 0.14 |

| Rasoul et al. [57] | 192 | 31 | 29 | 415 | 89 | 162 | 37 | 15 | 361 | 67 | < 0.001 | 0.156 |

| Ahmed et al. [65] | 24 | 22 | 4 | 70 | 30 | 37 | 13 | 0 | 87 | 13 | < 0.001 | 0.15 |

P-HWE P value for Hardy–Weinberg equilibrium, MAF minor allele frequency of control group

Quantitative synthesis

Meta-analysis of the association between FokI (rs2228570) polymorphism and T1DM risk

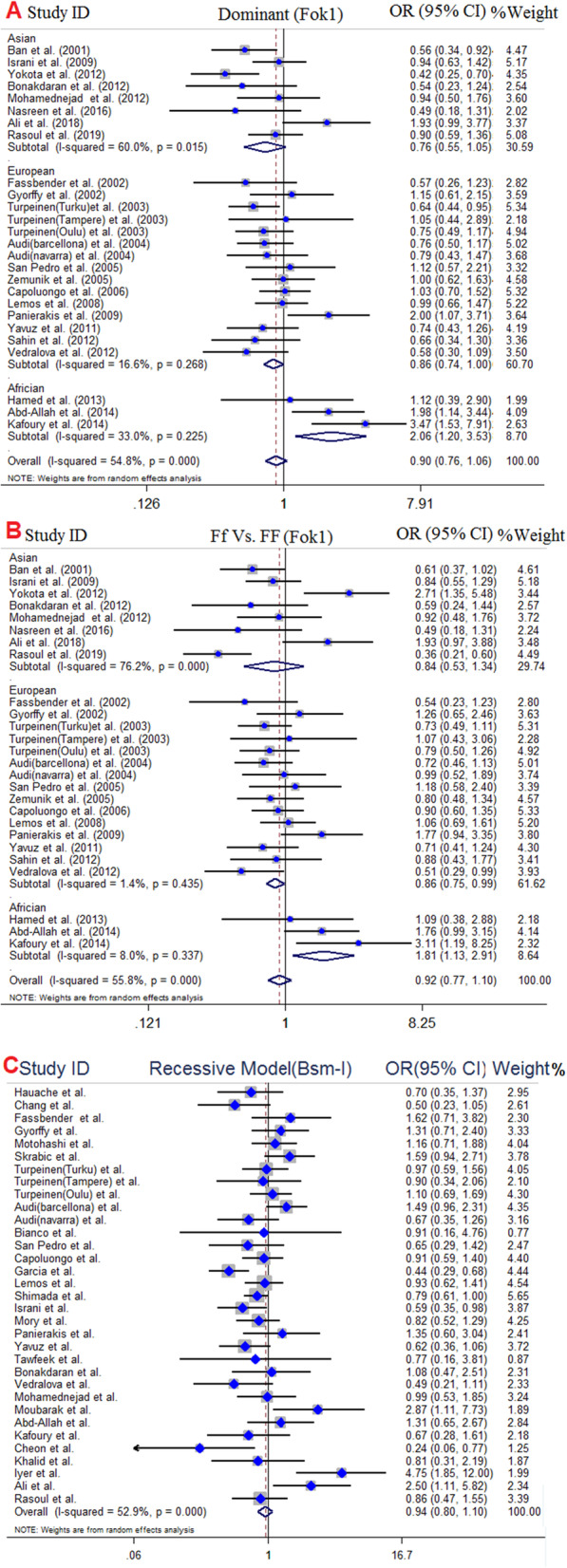

Overall, 29 case-control studies with 3723 cases and 5578 controls were analyzed for assessment of FokI polymorphism and T1DM risk. Of 29 studies, 15 studies were conducted in European countries [15, 34–36, 38–41, 44, 47, 49, 71], 9 studies were in Asian countries [33, 42, 45, 46, 48, 54–57], 3 studies were in African population [51–53] and eventually one study in Australia [50] and one study in American population [43]. Among studies were performed in Europe, Audi et al. [71] conducted an association study in different city of Spain (Barcelona and Navarra) and reported all data separately including genotype and allele frequency; thus we considered each population as a separate study. The pooled results revealed no significant association in overall population across all genotype models, meanwhile subgroup analysis according to ethnicity showed decreased risk of T1DM susceptibility in European population [dominant model (OR = 0.86, 95% CI, 0.74–1.00, P = 0.05) and heterozygote contrast (OR = 0.86, 95% CI, 0.75–0.99, P = 0.04)] and increased risk of T1DM susceptibility in African population under all genotype models; dominant model (OR = 2.06, 95% CI, 1.20–3.53, P = 0.008), recessive model (OR = 2.14, 95% CI, 1.03–4.43, P = 0.04), allelic model (OR = 1.17, 95% CI, 1.06–2.97, P = 0.02), ff vs. FF model (OR = 3.11, 95% CI, 1.44–6.69, P = 0.004), and Ff vs. FF model (OR = 1.81, 95% CI, 1.13–2.91, P = 0.01). Besides, susceptibility to T1DM in Asians compared to Africans and Europeans were not affected by FokI polymorphism (Fig. 2). The results of pooled ORs, heterogeneity tests and publication bias tests in different analysis models are shown in Table 3.

Fig. 2.

Pooled OR and 95% CI of individual studies and pooled data for the association between ApaI gene polymorphism and T1DM risk in heterozygote contrast (Aa vs. AA)

Table 3.

Main results of pooled ORs in meta-analysis of Vitamin D Receptor gene polymorphisms

| Group | Genetic Model | Case/Control | Test of Association | Test of Heterogenicity | Test of publication bias | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (Begg’s test) | (Egger’s test) | |||||||||

| OR | 95%CI (P value) | I2 (%) | P | Z | P | T | P | |||

| FokI (rs2228570) | ||||||||||

| Overall | Dominant model | 3723 / 5578 | 0.92 | 0.79–1.08 (0.31) | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | 0.28 | 0.78 | 0.79 | 0.43 |

| Recessive model | 3723 / 5578 | 0.98 | 0.71–1.35 (0.91) | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | 1.43 | 0.15 | 1.28 | 0.21 | |

| Allelic model | 3723 / 5578 | 0.96 | 0.81–1.14 (0.65) | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | 0.71 | 0.47 | 0.87 | 0.39 | |

| ff vs. FF | 3723 / 5578 | 0.96 | 0.69–1.35 (0.83) | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | 1.70 | 0.09 | 1.78 | 0.08 | |

| Ff vs. FF | 3723 / 5578 | 0.94 | 0.79–1.12 (0.49) | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | 1.19 | 0.23 | 1.23 | 0.22 | |

| European | Dominant model | 3723 / 5578 | 0.86 | 0.74–1.00 (0.05) | 0.268 | 0.268 | −0.15 | 0.88 | 0.33 | 0.74 |

| Recessive model | 2077 / 3849 | 1.00 | 0.77–1.30 (0.98) | 0.011 | 0.011 | 0.60 | 0.54 | 1.15 | 0.27 | |

| Allelic model | 2077 / 3849 | 0.93 | 0.82–1.06 (0.28) | 0.015 | 0.015 | - 0.05 | 0.96 | 0.69 | 0.50 | |

| ff vs. FF | 2077 / 3849 | 0.90 | 0.67–1.20 (0.46) | 0.046 | 0.046 | 0.27 | 0.78 | 1.01 | 0.33 | |

| Ff vs. FF | 2077 / 3849 | 0.86 | 0.75–0.99 (0.04) | 0.435 | 0.435 | 0.74 | 0.45 | 0.59 | 0.56 | |

| Asian | Dominant model | 2077 / 3849 | 0.76 | 0.55–1.05 (0.09) | 0.015 | 0.015 | - 0.74 | 0.45 | −0.31 | 0.76 |

| Recessive model | 1107 / 1272 | 0.93 | 0.23–3.68 (0.91) | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | 1.65 | 0.09 | 3.26 | 0.02 | |

| Allelic model | 1107 / 1272 | 0.78 | 0.46–1.33 (0.36) | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | − 0.25 | 0.80 | 0.04 | 0.97 | |

| ff vs. FF | 1107 / 1272 | 0.87 | 0.25–3.01 (0.82) | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | 1.95 | 0.05 | 3.01 | 0.03 | |

| Ff vs. FF | 1107 / 1272 | 0.84 | 0.53–1.34 (0.47) | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | 0.49 | 0.62 | 0.50 | 0.63 | |

| African | Dominant model | 1107 / 1272 | 2.06 | 1.20–3.53 (0.008) | 0.225 | 0.225 | - 0.52 | 0.60 | −0.19 | 0.88 |

| Recessive model | 312 /220 | 2.14 | 1.03–4.43 (0.04) | 0.382 | 0.382 | - 0.52 | 0.60 | −0.60 | 0.65 | |

| Allelic model | 312 /220 | 1.77 | 1.06–2.97 (0.02) | 0.057 | 0.057 | 0.52 | 0.60 | 0.23 | 0.85 | |

| ff vs. FF | 312 /220 | 3.11 | 1.44–6.69 (0.004) | 0.493 | 0.493 | - 1.57 | 0.11 | −1.65 | 0.34 | |

| Ff vs. FF | 312 /220 | 1.81 | 1.13–2.91 (0.01) | 0.337 | 0.337 | - 0.52 | 0.60 | 0.03 | 0.98 | |

| TaqI (rs731236) | ||||||||||

| Overall | Dominant model | 1873 / 1895 | 1.06 | 0.78 – 1.45 (0.70) | 78.3 | < 0.001 | − 0.45 | 0.65 | −1.61 | 0.12 |

| Recessive model | 1873 / 1895 | 0.91 | 0.66 – 1.26(0.58) | 59.1 | 0.001 | −1.93 | 0.05 | −1.93 | 0.07 | |

| Allelic model | 1873/ 1895 | 1.02 | 0.81 – 1.29 (0.86) | 81.9 | < 0.001 | −0.24 | 0.80 | − 0.96 | 0.34 | |

| tt vs. TT | 1873 / 1895 | 0.90 | 0.58 – 1.39 (0.62) | 72.9 | < 0.001 | −2.14 | 0.03 | −2.65 | 0.01 | |

| Tt vs.TT | 1873 / 18995 | 1.12 | 0.84– 1.49 (0.45) | 70.7 | < 0.001 | −0.39 | 0.69 | −1.04 | 0.31 | |

| European | Dominant model | 840 / 878 | 0.82 | 0.59–1.13 (0.23) | 49.1 | 0.056 | −1.48 | 0.13 | −1.88 | 0.11 |

| Recessive model | 840 / 878 | 0.78 | 0.50–1.21 (0.26) | 55.1 | 0.029 | −1.24 | 0.21 | −0.95 | 0.38 | |

| Allelic model | 840 / 878 | 0.92 | 0.76–1.11 (0.36) | 9.6 | 0.356 | −1.73 | 0.08 | −1.27 | 0.25 | |

| tt vs. TT | 840 / 878 | 0.75 | 0.44–1.27 (0.28) | 61.1 | 0.012 | −1.73 | 0.08 | −1.68 | 0.14 | |

| Tt vs.TT | 840 / 878 | 0.87 | 0.64–1.20 (0.40) | 39.8 | 0.114 | − 0.99 | 0.32 | −1.10 | 0.31 | |

| Asian | Dominant model | 1033 / 1017 | 1.40 | 0.75 – 2.58 (0.28) | 85.7 | < 0.001 | 0 | 1 | −1.08 | 0.31 |

| Recessive model | 1033 / 1017 | 1.05 | 0.51 – 2.16 (0.88) | 74.5 | 0.008 | −2.44 | 0.01 | −3.55 | 0.02 | |

| Allelic model | 1033 / 1017 | 1.27 | 0.75 – 2.14 (0.36) | 88.7 | < 0.001 | 0 | 1 | −0.75 | 0.45 | |

| tt vs. TT | 1033 / 1017 | 1.03 | 0.37 – 2.85 (0.95) | 85.4 | < 0.001 | −1.69 | 0.09 | −3.10 | 0.03 | |

| Tt vs.TT | 1033 / 1017 | 1.46 | 0.83 – 2.58 (0.19) | 80.1 | < 0.001 | − 0.83 | 0.40 | − 0.77 | 0.46 | |

| BsmI (rs1544410) | ||||||||||

| Overall | Dominant model | 4826 / 7159 | 1.02 | 0.80– 1.30 (0.88) | 76.3 | < 0.001 | −0.25 | 0.80 | 0.48 | 0.63 |

| Recessive model | 4826 / 7159 | 0.94 | 0.80 – 1.10 (0.45) | 52.9 | < 0.001 | 0.13 | 0.89 | 0.20 | 0.84 | |

| Allelic model | 4826 / 7159 | 0.99 | 0.86 – 1.15 (0.92) | 77.6 | < 0.001 | 0.21 | 0.83 | 0.16 | 0.87 | |

| bb vs. BB | 4826 / 7159 | 0.96 | 0.75– 1.23 (0.74) | 59.8 | < 0.001 | −0.59 | −0.55 | −0.69 | 0.49 | |

| Bb vs. BB | 4826 / 7159 | 1.07 | 0.88 – 1.29 (0.52) | 53.9 | < 0.001 | −0.19 | 0.84 | −0.58 | 0.56 | |

| European | Dominant model | 1938 / 4450 | 0.94 | 0.71–1.24 (0.66) | 71.0 | < 0.001 | −0.25 | 0.80 | 0.89 | 0.39 |

| Recessive model | 1938 / 4450 | 1.00 | 0.85–1.19 (0.95) | 20.7 | 0.223 | −0.25 | 0.80 | −0.63 | 0.54 | |

| Allelic model | 1938 / 4450 | 1.00 | 0.89–1.13 (0.93) | 41.7 | 0.046 | −0.35 | 0.72 | −0.75 | 0.46 | |

| bb vs. BB | 1938 / 4450 | 0.99 | 0.80–1.23 (0.92) | 16.1 | 0.273 | 0.05 | 0.96 | −0.57 | 0.57 | |

| Bb vs. BB | 1938 / 4450 | 1.05 | 0.89–1.25 (0.56) | 15.0 | 0.286 | −0.45 | 0.65 | −0.99 | 0.34 | |

| Asian | Dominant model | 2195 /2004 | 1.05 | 0.61 – 1.79 (0.87) | 77.8 | < 0.001 | − 0.12 | 0.90 | −0.38 | 0.71 |

| Recessive model | 2195 /2004 | 1.02 | 0.73 – 1.40 (0.92) | 65.7 | < 0.001 | −0.38 | 0.70 | 0.18 | 0.86 | |

| Allelic model | 2195 /2004 | 1.00 | 0.72 – 1.38 (0.97) | 85 | < 0.001 | 0.38 | 0.70 | 0.24 | 0.81 | |

| bb vs. BB | 2195 /2004 | 1.07 | 0.55 – 2.09 (0.84) | 76.8 | < 0.001 | −0.12 | 0.90 | −0.42 | 0.68 | |

| Bb vs. BB | 2195 /2004 | 1.07 | 0.67 – 1.71(0.77) | 63.5 | < 0.001 | 0.12 | 0.90 | −0.49 | 0.63 | |

| American | Dominant model | 463 / 479 | 0.57 | 0.39–0.84 (0.004) | 0.0 | 0.755 | 1.57 | 0.11 | 14.1 | 0.04 |

| Recessive model | 463 / 479 | 0.62 | 0.41–0.94 (0.02) | 50.5 | 0.133 | 0.52 | 0.60 | 0.38 | 0.76 | |

| Allelic model | 463 / 479 | 0.66 | 0.54–0.81 (< 0.001) | 0.0 | 0.549 | 0.52 | 0.60 | 0.80 | 0.57 | |

| bb vs. BB | 463 / 479 | 0.52 | 0.34–0.80 (0.003) | 0.0 | 0.876 | 0.52 | 0.60 | 0.06 | 0.96 | |

| Bb vs. BB | 463 / 479 | 0.66 | 0.41–1.05 (0.08) | 13.2 | 0.316 | 0.52 | 0.60 | 1.56 | 0.36 | |

| African | Dominant model | 230 / 226 | 2.41 | 0.63–9.18 (0.19) | 81 | 0.065 | −0.52 | 0.60 | −0.15 | 0.90 |

| Recessive model | 230 / 226 | 0.99 | 0.52–1.89 (0.96) | 26.8 | 0.242 | −1 | 0.31 | 0.18 | 0.23 | |

| Allelic model | 230 / 226 | 1.63 | 0.65–4.08 (0.29) | 86.3 | 0.031 | −0.52 | 0.60 | 0.05 | 0.96 | |

| bb vs. BB | 230 / 226 | 1.18 | 0.26–5.25 (0.83) | 67.0 | 0.082 | −1 | 0.31 | 0.15 | 0.35 | |

| Bb vs. BB | 230 / 226 | 2.40 | 0.81–7.17 (0.11) | 63.9 | 0.141 | −0.52 | 0.60 | −0.16 | 0.89 | |

| ApaI (rs7975232) | ||||||||||

| Overall | Dominant model | 2436 / 4074 | 1.03 | 0.82–1.29 (0.79) | 66.2 | < 0.001 | 0.25 | 0.80 | 0.62 | 0.54 |

| Recessive model | 2436 / 4074 | 1.03 | 0.90–1.17 (0.68) | 48.4 | 0.005 | 0.24 | 0.81 | 0.20 | 0.84 | |

| Allelic model | 2436 / 4074 | 1.05 | 0.90–1.23 (0.52) | 72.7 | < 0.001 | 0.99 | 0.32 | 0.98 | 0.34 | |

| aa vs. AA | 2436 / 4074 | 1.02 | 0.77–1.33 (0.90) | 52.9 | 0.002 | −0.18 | 0.85 | −0.56 | 0.57 | |

| Aa vs. AA | 2436 / 4074 | 0.91 | 0.80–1.04 (0.18) | 25.5 | 0.355 | −0.03 | 0.97 | 0.05 | 0.97 | |

| European | Dominant model | 1258/ 2913 | 0.91 | 0.70–1.18 (0.47) | 49.1 | 0.039 | −0.98 | 0.32 | −1.24 | 0.25 |

| Recessive model | 1258/ 2913 | 1.09 | 0.92–1.30 (0.32) | 56.9 | 0.013 | −0.63 | 0.53 | −0.28 | 0.78 | |

| Allelic model | 1258/ 2913 | 0.99 | 0.81–1.21 (0.90) | 68.6 | 0.001 | −1.16 | 0.24 | −0.62 | 0.54 | |

| aa vs. AA | 1258/ 2913 | 1.02 | 0.72–1.45 (0.91) | 53.1 | 0.024 | −1.70 | 0.08 | −1.03 | 0.33 | |

| Aa vs. AA | 1258/ 2913 | 0.90 | 0.75–1.09 (0.29) | 29.5 | 0.174 | −1.70 | 0.08 | −2.23 | 0.05 | |

| Asian | Dominant model | 1178 / 1161 | 1.27 | 0.78–2.05 (0.34) | 77.4 | < 0.001 | 1.70 | 0.08 | 0.90 | 0.39 |

| Recessive model | 1178 / 1161 | 0.91 | 0.71–1.15 (0.42) | 52.0 | 0.027 | 1.88 | 0.06 | 1.26 | 0.24 | |

| Allelic model | 1178 / 1161 | 1.15 | 0.82–1.62 (0.40) | 82.2 | < 0.001 | 1.34 | 0.18 | 1.69 | 0.13 | |

| aa vs. AA | 1178 / 1161 | 1.14 | 0.63–2.04 (0.66) | 64.8 | 0.002 | 1.34 | 0.18 | 0.23 | 0.82 | |

| Aa vs. AA | 1178 / 1161 | 0.92 | 0.72–1.18 (0.52) | 6.8 | 0.379 | 1.46 | 0.14 | 1.35 | 0.22 | |

Meta-analysis of the association between TaqI (rs731236) polymorphism and T1DM risk

There were 20 case-control studies with 1837 cases and 1895 controls concerning TaqI polymorphism and T1DM risk. Studies were performed in different population, 8 studies were in Europeans [15, 34, 35, 38, 41, 44, 59, 60], 8 studies in Asians [42, 46, 48, 57, 58, 62–64], 2 studies in Africans [52, 65] and one study each was in Australia [50] and Americans [61]. Meta-analysis rejected any significant association between TaqI SNP and the risk of T1DM susceptibility. Moreover, the results of subgroup analysis by ethnicity were not significant under five genotype models. In subgroup analysis, since there was only one study for the Australians [50], Americans [61], and two studies for Africans [52, 65], these studies were excluded from the analysis. The results of pooled ORs, heterogeneity tests and publication bias tests in different analysis models are shown in Table 3.

Meta-analysis of the association between BsmI (rs1544410) polymorphism and T1DM risk

To examining the association between BsmI polymorphism and T1DM risk, 34 case-control studies with 4826 cases and 7159 controls subjects were included. It was detected that 15 studies with 1938 cases and 4450 controls were performed in European countries [15, 34–36, 38, 40, 41, 44, 49, 59, 60, 71] which among these 15 studies, Turpeinen et al. [36] conducted an association study in different city of Finland (Turku, Tampere and Oulu) and reported all data separately, including genotype and allele frequency; thus we considered each population as a separate study. Moreover, 13 studies out of 34 eligible studies were carried out in Asian populations [42, 46, 48, 56–58, 62–64, 67–70], 3 studies were in Americans [43, 61, 66] and three studies were in Africans [52, 53, 65]. No significant association between BsmI polymorphism and T1DM risk were found under all genotype models for the overall population. However, pooled results of subgroup analysis indicated markedly significant negative associations between BsmI SNP and the risk of T1DM susceptibility in American populations across all genotype models; dominant model (OR = 0.57, 95% CI, 0.39–0.84, P = 0.004), recessive model (OR = 0.62, 95% CI, 0.41–0.94, P = 0.02), allelic model (OR = 0.66, 95% CI, 0.54–0.81, P < 0.001), bb vs. BB model (OR = 0.52, 95% CI, 0.34–0.80, P = 0.003), except Bb vs. BB model (OR = 0.66, 95% CI, 0.41–1.05, P = 0.08) (Fig. 3). No significant association was detected for European, Asian and African population. The results of pooled ORs, heterogeneity tests and publication bias tests in different analysis models are shown in Table 3.

Fig. 3.

Pooled odds ratio (OR) and 95% confidence interval of individual studies and pooled data for the association between FokI, BsmI gene polymorphism and T1DM risk in different ethnicity subgroups and overall populations for A; dominant model (FokI), B; Ff vs. FF Model (FokI), and C; Recessive Model (BsmI)

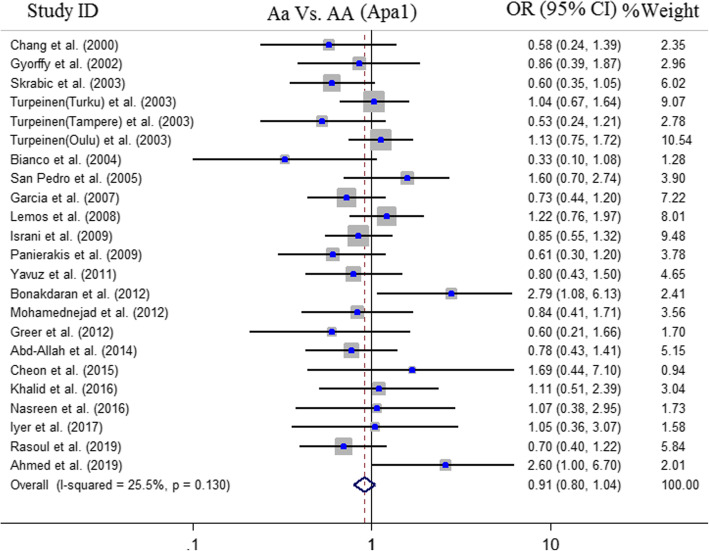

Meta-analysis of the association between ApaI (rs7975232) polymorphism and T1DM risk

Finally, 24 case-control studies with 2436 cases and 4074 controls were identified eligible for quantitative synthesis of the association between ApaI polymorphism and T1DM risk. Overall, 10 studies were conducted in Europe [15, 35, 36, 38, 41, 44, 59, 60], 10 studies were in Asia [42, 46, 48, 54, 55, 57, 58, 62–64], 2 studies in Africa [52, 65] and one study each was in Australia [50] and America [61]. Because of limited number of studies performed in Australia, America and Africa these studies were excluded from subgroup analysis. The results demonstrated no significant association between the ApaI polymorphism and risk of T1DM in the overall population and ethnic-specific analysis (Fig. 3). The results of pooled ORs, heterogeneity tests and publication bias tests in different analysis models are shown in Table 3.

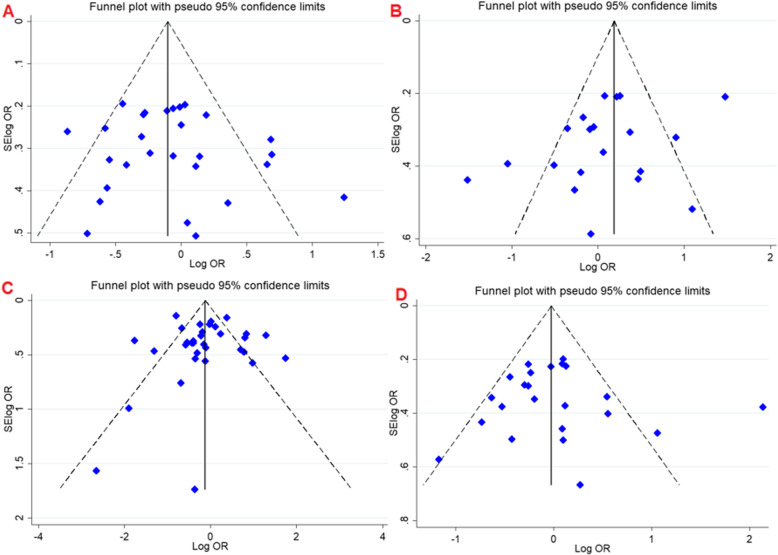

Evaluation of heterogeneity and publication bias

During the meta-analysis of VDR gene polymorphism evidence of substantial to moderate heterogeneity was detected. However, partial heterogeneity was resolved while the data were stratified by ethnicity. Publication bias was evaluated by funnel plot, Begg’s test and Egger’s test. There was no obvious evidence of asymmetry from the shapes of the funnel plots (Fig. 4), and all P values of Begg’s test and Egger’s test were > 0.05, which showed no evidences of publication biases.

Fig. 4.

Begg’s funnel plot for publication bias test. A; dominant model FokI. B; dominant model TaqI. C; dominant model BsmI. D; dominant model ApaI. Each point represents a separate study for the indicated association

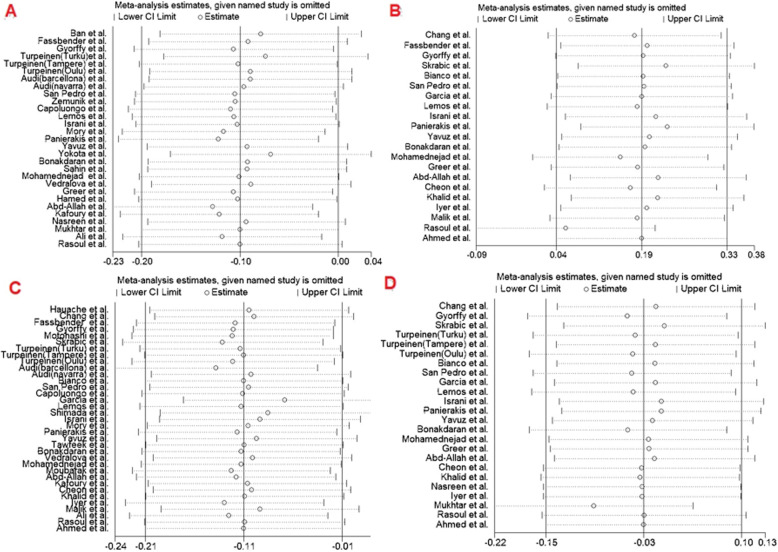

Sensitivity analysis

The leave-one-out method was used in the sensitivity analysis to explore the effect of individual data on the pooled ORs. The significance of ORs was not altered through omitting any single study in the dominant model for FokI, TaqI, BsmI and ApaI SNPs, indicating that our results were statistically robust (Fig. 5).

Fig. 5.

Sensitivity analysis in present meta-analysis investigates the single nucleotide polymorphisms of Vitamin D Receptor contribute to risk for T1DM (A, FokI; B, TaqI; C, BsmI; D, ApaI)

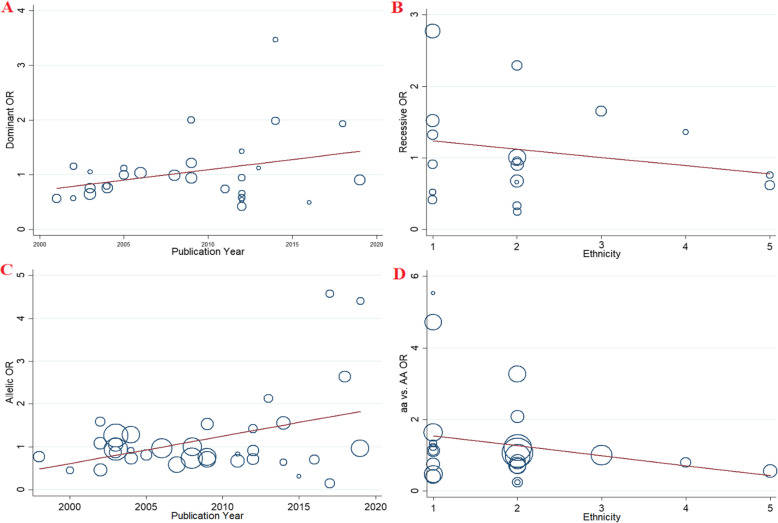

Bayesian meta-regression analysis

Meta-regression and subgroup analyses were performed to explore potential sources of heterogeneity among included studies (Table 4). The findings of meta-regression indicated that ethnicity can be the potential source of heterogeneity, therefore, subgroup analysis was performed to attenuate the effect of these parameters. (Fig. 6).

Table 4.

Meta-regression analyses of potential source of heterogeneity

| Heterogeneity Factor | Coefficient | SE | T | P-value | 95% CI | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| UL | LL | ||||||

| FokI (rs2228570) | |||||||

| Publication Year | Dominant model | 0.037 | 0.021 | 1.74 | 0.09 | - 0.006 | 0.082 |

| Recessive model | 0.763 | 0.313 | 2.44 | 0.02 | 0.117 | 1.410 | |

| Allelic model | 0.037 | 0.018 | 2.07 | 0.04 | 0.001 | 0.074 | |

| ff vs. FF | 0.631 | 0.242 | 2.60 | 0.01 | 0.130 | 1.131 | |

| Ff vs. FF | 0.032 | 0.022 | 1.43 | 0.16 | −0.014 | 0.078 | |

| Ethnicity | Dominant model | 0.322 | 0.081 | 3.97 | 0.001 | 0.155 | 0.489 |

| Recessive model | −1.10 | 1.43 | −0.77 | 0.44 | −4.063 | 1.85 | |

| Allelic model | 0.231 | 0.073 | 3.15 | 0.004 | 0.080 | 0.382 | |

| ff VS. FF | −0.591 | 1.134 | −0.52 | 0.60 | −2.932 | 1.749 | |

| Ff vs. FF | 0.217 | 0.097 | 2.23 | 0.03 | 0.017 | 0.416 | |

| TaqI (rs731236) | |||||||

| Publication Year | Dominant model | 0.069 | 0.037 | 1.83 | 0.08 | −0.010 | 0.148 |

| Recessive model | 0.020 | 0.031 | 0.65 | 0.52 | −0.046 | 0.087 | |

| Allelic model | 0.038 | 0.026 | 1.47 | 0.15 | −0.016 | 0.093 | |

| tt vs. TT | 0.063 | 0.048 | 1.32 | 0.20 | −0.039 | 0.166 | |

| Tt vs.TT | 0.064 | 0.037 | 1.72 | 0.10 | −0.014 | 0.142 | |

| Ethnicity | Dominant model | −0.249 | 0.207 | −1.20 | 0.24 | −0.684 | 0.185 |

| Recessive model | −0.114 | 0.145 | −0.79 | 0.44 | − 0.424 | 0.194 | |

| Allelic model | −0.145 | 0.123 | −1.18 | 0.25 | −0.404 | 0.113 | |

| tt vs. TT | −0.167 | 0.253 | −0.66 | 0.51 | −0.707 | 0.373 | |

| Tt vs.TT | −0.250 | 0.200 | −1.25 | 0.22 | −0.670 | 0.170 | |

| BsmI (rs1544410) | |||||||

| Publication Year | Dominant model | 0.142 | 0.046 | 3.03 | 0.005 | 0.046 | 0.237 |

| Recessive model | 0.031 | 0.024 | 1.29 | 0.20 | −0.018 | 0.081 | |

| Allelic model | 0.063 | 0.025 | 2.54 | 0.01 | 0.012 | 0.115 | |

| bb vs. BB | 0.103 | 0.047 | 2.17 | 0.03 | 0.006 | 0.200 | |

| Bb vs. BB | 0.095 | 0.033 | 2.84 | 0.008 | 0.026 | 0.163 | |

| Ethnicity | Dominant model | 0.482 | 0.265 | 1.82 | 0.07 | −0.058 | 1.023 |

| Recessive model | −0.133 | 0.139 | −0.96 | 0.34 | −0.417 | 0.149 | |

| Allelic model | 0.152 | 0.143 | 1.07 | 0.293 | −0.138 | 0.444 | |

| bb vs. BB | −0.274 | 0.280 | −0.98 | 0.33 | −0.846 | 0.296 | |

| Bb vs. BB | 0.381 | 0.188 | 2.03 | 0.05 | −0.002 | 0.764 | |

| ApaI (rs7975232) | |||||||

| Publication Year | Dominant model | 0.098 | 0.054 | 1.81 | 0.08 | −0.014 | 0.211 |

| Recessive model | 0.005 | 0.030 | 0.18 | 0.86 | −0.057 | 0.068 | |

| Allelic model | 0.052 | 0.032 | 1.64 | 0.11 | −0.013 | 0.119 | |

| aa vs. AA | 0.042 | 0.042 | 0.98 | 0.33 | −0.047 | 0.131 | |

| Aa vs. AA | 0.027 | 0.019 | 1.37 | 0.18 | −0.014 | 0.069 | |

| Ethnicity | Dominant model | −0.130 | 0.290 | −0.45 | 0.65 | −0.733 | 0.471 |

| Recessive model | −0.086 | 0.175 | −0.49 | 0.62 | −0.452 | 0.279 | |

| Allelic model | 0.007 | 0.171 | 0.04 | 0.96 | −0.348 | 0.362 | |

| aa vs. AA | −0.279 | 0.243 | −1.15 | 0.26 | −0.785 | 0.226 | |

| Aa vs. AA | 0.033 | 0.103 | 0.32 | 0.74 | −0.181 | 0.248 | |

Fig. 6.

Meta-regression plots of the association between VDR gene polymorphisms and risk of CAD based on; A: Publication year (Dominant model), B: Ethnicity (Recessive model), C: Publication year (Allelic model), C: Ethnicity (aa vs. AA model)

Discussion

In this study, we performed a systematic review and meta-analysis to achieve a vivid and exact approximation of the associations between the VDR gene polymorphisms, including FokI (rs2228570), TaqI (rs731236), BsmI (rs1544410), and ApaI (rs7975232) and susceptibility to T1DM. The findings of meta-analysis on 39 case–control studies, containing 29 studies with 3723 cases and 5578 controls for FokI, 20 studies with 1837 cases and 1895 controls for TaqI, 34 studies with 4826 cases and 7159 controls for BsmI, and 24 studies with 2436 cases and 4074 controls for ApaI, indicated no significant association of VDR gene polymorphisms with T1DM risk in overall population. That notwithstanding, the subgroup analysis resulted in identification of significant associations between FokI and BsmI polymorphism and T1DM in African and American population. Our study provided some beneficial points over previous studies. First, this meta-analysis included further studies with more sample size compared with the previous studies, conferring more conclusive results. Second, we performed subgroup analysis by ethnicity to indicated association of VDR gene polymorphisms with T1DM risk in different ethnical groups.

Over the course of past years, a bulk of studies has addressed the association of VDR gene polymorphisms and risk of T1DM throughout various populations, resulting in conflicting findings [61, 67]. Such discrepancies might stem from diversity in detection methods, differences in diagnostic criterions, clinical heterogeneity, small sample sizes, low statistical power, and interactions between genetic and environmental contributing factors according to variations in the geo-epidemiological factors. As a consequence, three previous meta-analyses by Guo et al. [21] in 2006 [including 11 studies for FokI (1424 cases and 3301 controls), 13 studies for BsmI (1601cases and 4207 controls), 9 studies for ApaI (1101 cases and 2805 controls), and 7 studies for TaqI (681 cases and 781 controls)], Zhang et al. [22] in 2012 [T1DM cases and 4049 controls in 21 studies for BsmI, 2167 T1DM cases and 3402 controls in 17 studies for FokI, 1166 T1DM cases and 2328 controls in 11 studies for ApaI, and 1041 T1DM cases and 1137 controls in 8 studies for TaqI], and Tizaouia et al. [20] in 2014 (13 studies for TaqI, 23 studies for BsmI, 15 studies for ApaI, and 18 studies for FokI) were carried out to resolved the conundrum and attain an exact approximation. They indicated that VDR gene SNPs were not associated with T1DM risk, except than BsmI polymorphism association with T1DM predisposition that was observed in Zhang et al. [22] study. Upon the latest meta-analysis published in 2014, several original association studies evaluated the role of VDR gene polymorphisms with T1DM risk. As a result, the necessity for performing an updated meta-analysis is sensed to come up with resolution of the limitations of individual association studies and to gain a much more valid and comprehensive pooled estimation on the association of VDR gene polymorphisms with T1D risk.

Previous meta-analysis performed by Tizaouia et al. [20] in 2014 reported no significant association of VDR gene FokI polymorphism with risk of T1D. According to our meta-analysis, the pooled results in overall population across all genotype models demonstrated no significant association of VDR gene FokI polymorphism; nonetheless, subgroup analysis according to ethnicity showed a marginally-significant decreased susceptibility to T1DM in European population according to dominant genetic model and heterozygote comparison, while an increased risk of T1DM in African population according to all genotype models. In addition, our meta-analysis did not support any significant association between TaqI SNP and susceptibility to T1DM. Furthermore, the results of subgroup analysis according to ethnicity did not show any significant association in all genetic models. However, in the subgroup analysis, given that there was only one study in the Australian [50] and American [61] populations, and two studies in the African [52, 65] population, the subgroup analysis was not performed in these populations. In line with our findings, previous meta-analysis by Tizaouia et al. [20] also did not show significant association of VDR gene TaqI polymorphism with risk of T1D. According to the previous meta-analysis, BsmI SNP was not the risk factor for T1D susceptibility. However, after excluding one study, a marginal significant (P = 0.051) association was found in the homozygous model. On the other side, our meta-analysis also revealed that BsmI polymorphism was not a risk for T1DM in all genetic models when all of the population were analyzed. Nonetheless, subgroup analysis demonstrated a strong negative significant association between BsmI SNP and the risk of T1DM in American population in all of the genetic model comparisons. Finally neither our meta-analysis nor the previous one by Tizaouia et al. [20] found any significant association of ApaI polymorphism and T1DM risk in overall as well as subgroup analyses. Taken together, although our meta-analysis included further studies compared to the previous study, the overall analysis was almost the same. Nonetheless, our subgroup analysis indicated association of VDR genetic polymorphisms with T1DM risk in different ethnical groups.

In their meta-analysis, Tizaoui et al. [20] indicated in the stratification analysis that publication year, age, gender, estimated VitD levels, and latitude modulated the association between VDR gene polymorphisms and T1D risk. Furthermore, another meta-analysis revealed a relationship between winter ultraviolet radiation (UVR) and VDR gene polymorphisms in T1DM, implying to the influence of the UVR on the association between VDR polymorphisms and T1DM susceptibility [72]. During the four cooler months, it was observed that latitude strongly determines the available levels of VitD producing UV. As latitude increases, the amount of VitD producing UV decreases, which may prevent VitD synthesis in humans [73]. As a result, the latitude of the locations in which the individuals live may impress the susceptibility to develop T1DM.

Despite we tried to conduct best meta-analysis of the VDR gene polymorphisms and susceptibility to RA, there was also a number of limitations that should be taken into account. First, there was significant heterogeneity across studies, which may lessen the certainty of the results. However, we tried to find and attenuate its effect by meta-regression and subgroup analysis. Consequently, heterogeneity was still an unavoidable problem that may influence the accuracy of the overall results. Second, only articles published in the English language were include in this meta-analysis. Third, our meta-analysis was based on crude approximation of the genetic variations regardless of adjusting the analysis by gender, age, VitD intake, and other environmental factors like exposure to sun light, as several studies noted the involvement of these parameters as well as gene-environment and gene-gene interactions in the susceptibility and of RA and we could not analyze it owing to a lack of published well-structured data.

Conclusion

In conclusion, this study was a systematic review and meta-analysis of 40 case–control association studies to come up with the clear estimation of the associations between the VDR gene SNPs [FokI (rs2228570), TaqI (rs731236), BsmI (rs1544410), and ApaI (rs7975232)] and susceptibility to T1DM. The findings of meta-analysis revealed no significant association of VDR gene SNPs with T1DM risk in the overall population. However, the subgroup analysis indicated significant associations between FokI and BsmI polymorphism and T1DM risk in African and American population. As a limitation, we did not evaluate a number of VDR gene SNPs that might act in interaction with environmental factors to determine the fate of T1DM pathogenicity. Further investigations on the VDR, above and beyond the genetic as well as traditional risk factors, may confer a possibility for identification of critical susceptibility factors in the disease development, which might be applicable in the personalized medicine for better and optimized therapy of T1DM patients.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Mrs. Maryam Izad for all her support.

Disclosure of conflict of interest

Not applicable.

Abbreviations

- T1DM

Type 1 diabetes mellitus

- VDR

Vitamin D receptor

- Vitamin D

VitD

- SNP

Single nucleotide polymorphisms

- IL

Interleukin

- PRISMA

Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta-Analyses

- NOS

Newcastle-Ottawa Scale

- UVR

Ultraviolet radiation

- Th

T helper

- TNF

Tumor necrosis factor

- IFN

Interferon

- HWE

Hardy–Weinberg equilibrium

- PCR- RFLP

Polymerase chain reaction-restriction fragment length polymorphism

Authors’ contributions

NZ participated in study design and manuscript drafting. RB, participated in literature search and contributed to manuscript drafting. MHM analyzed the data and participated in drafting the manuscript. SA analyzed and interpreted the data and participated in manuscript drafting. PM contributed to data analysis and prepared the original draft. BR performed the literature search, analyzed data, and participated in manuscript drafting. DI performed the literature search, developed the main idea, and participated in manuscript drafting. MY performed the literature search and participated in manuscript drafting. HM performed data interpretation and participated in manuscript drafting. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Availability of data and materials

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Na Zhai, Email: zhai13331222287@126.com.

Haleh Mikaeili, Email: mikaeilihale@gmail.com.

References

- 1.Gupta G, et al. A clinical update on metformin and lung cancer in diabetic patients. Panminerva Med. 2018;60(2):70–75. doi: 10.23736/S0031-0808.18.03394-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Atkinson MA, Eisenbarth GS, Michels AW. Type 1 diabetes. Lancet. 2014;383(9911):69–82. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)60591-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Miettinen ME, et al. Genetic determinants of serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D concentration during pregnancy and type 1 diabetes in the child. PLoS One. 2017;12(10):e0184942. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0184942. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Diaz-Valencia PA, Bougnères P, Valleron A-J. Global epidemiology of type 1 diabetes in young adults and adults: a systematic review. BMC Public Health. 2015;15(1):255. doi: 10.1186/s12889-015-1591-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Todd JA, et al. Robust associations of four new chromosome regions from genome-wide analyses of type 1 diabetes. Nat Genet. 2007;39(7):857. doi: 10.1038/ng2068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Vaidya A, Williams JS. The relationship between vitamin D and the renin-angiotensin system in the pathophysiology of hypertension, kidney disease, and diabetes. Metabolism. 2012;61(4):450–458. doi: 10.1016/j.metabol.2011.09.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Riek AE, et al. Vitamin D suppression of endoplasmic reticulum stress promotes an antiatherogenic monocyte/macrophage phenotype in type 2 diabetic patients. J Biol Chem. 2012;287(46):38482–38494. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112.386912. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Makoui MH, Imani D, Motallebnezhad M, Azimi M, Razi B. Vitamin D receptor gene polymorphism and susceptibility to asthma: Meta-analysis based on 17 case-control studies. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2020;124(1):57–69. doi: 10.1016/j.anai.2019.10.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bagheri-Hosseinabadi Z, et al. Vitamin D receptor (VDR) gene polymorphism and risk of rheumatoid arthritis (RA): systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin Rheumatol. 2020. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 10.Bhalla AK, et al. 1, 25-Dihydroxyvitamin D3 inhibits antigen-induced T cell activation. J Immunol. 1984;133(4):1748–1754. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lemire JM. Immunomodulatory actions of 1, 25-dihydroxyvitamin D3. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol. 1995;53(1–6):599–602. doi: 10.1016/0960-0760(95)00106-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Riachy R, et al. 1, 25-Dihydroxyvitamin D 3 protects human pancreatic islets against cytokine-induced apoptosis via down-regulation of the Fas receptor. Apoptosis. 2006;11(2):151–159. doi: 10.1007/s10495-006-3558-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Trembleau S, et al. The role of IL-12 in the induction of organ-specific autoimmune diseases. Immunol Today. 1995;16(8):383–386. doi: 10.1016/0167-5699(95)80006-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Uitterlinden AG, et al. Genetics and biology of vitamin D receptor polymorphisms. Gene. 2004;338(2):143–156. doi: 10.1016/j.gene.2004.05.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Panierakis C, et al. Vitamin D receptor gene polymorphisms and susceptibility to type 1 diabetes in Crete, Greece. Clin Immunol. 2009;133(2):276–281. doi: 10.1016/j.clim.2009.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wang Q, et al. Quantitative assessment of the associations between four polymorphisms (FokI, ApaI, BsmI, TaqI) of vitamin D receptor gene and risk of diabetes mellitus. Mol Biol Rep. 2012;39(10):9405–9414. doi: 10.1007/s11033-012-1805-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ferrari S, et al. Vitamin D receptor gene start codon polymorphisms (FokI) and bone mineral density: interaction with age, dietary calcium, and 3′-end region polymorphisms. J Bone Miner Res. 1998;13(6):925–930. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.1998.13.6.925. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Imani D, et al. Association between vitamin D receptor (VDR) polymorphisms and the risk of multiple sclerosis (MS): an updated meta-analysis. BMC Neurol. 2019;19(1):339. doi: 10.1186/s12883-019-1577-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Valdivielso JM, Fernandez E. Vitamin D receptor polymorphisms and diseases. Clin Chim Acta. 2006;371(1–2):1–12. doi: 10.1016/j.cca.2006.02.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tizaoui K, et al. Contribution of VDR polymorphisms to type 1 diabetes susceptibility: systematic review of case–control studies and meta-analysis. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol. 2014;143:240–249. doi: 10.1016/j.jsbmb.2014.03.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Guo S-W, et al. Meta-analysis of vitamin D receptor polymorphisms and type 1 diabetes: a HuGE review of genetic association studies. Am J Epidemiol. 2006;164(8):711–724. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwj278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zhang J, et al. Polymorphisms in the vitamin D receptor gene and type 1 diabetes mellitus risk: an update by meta-analysis. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2012;355(1):135–142. doi: 10.1016/j.mce.2012.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sahin OA, et al. Association of vitamin D receptor polymorphisms and type 1 diabetes susceptibility in children: a meta-analysis. Endocr Connections. 2017;6(3):159–171. doi: 10.1530/EC-16-0110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Qin W-H, et al. A meta-analysis of association of vitamin D receptor BsmI gene polymorphism with the risk of type 1 diabetes mellitus. J Recept Signal Transduct. 2014;34(5):372–377. doi: 10.3109/10799893.2014.903420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wang G, et al. Associations between two polymorphisms (FokI and BsmI) of vitamin D receptor gene and type 1 diabetes mellitus in Asian population: a meta-analysis. PLoS One. 2014;9(3):e89325. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0089325. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Moher D, et al. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. Ann Intern Med. 2009;151(4):264–269. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-151-4-200908180-00135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Stang A. Critical evaluation of the Newcastle-Ottawa scale for the assessment of the quality of nonrandomized studies in meta-analyses. Eur J Epidemiol. 2010;25(9):603–605. doi: 10.1007/s10654-010-9491-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Huedo-Medina TB, et al. Assessing heterogeneity in meta-analysis: Q statistic or I2 index? Psychol Methods. 2006;11(2):193. doi: 10.1037/1082-989X.11.2.193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.DerSimonian R, Laird N. Meta-analysis in clinical trials control. Clin Trials. 1986;7:177–188. doi: 10.1016/0197-2456(86)90046-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mantel N, Haenszel W. Statistical aspects of the analysis of data from retrospective studies of disease. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1959;22(4):719–748. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Egger M, et al. Bias in meta-analysis detected by a simple, graphical test. Bmj. 1997;315(7109):629–634. doi: 10.1136/bmj.315.7109.629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Begg CB, Mazumdar M. Operating characteristics of a rank correlation test for publication bias. Biometrics. 1994;50:1088–1101. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ban Y, et al. Vitamin D receptor initiation codon polymorphism influences genetic susceptibility to type 1 diabetes mellitus in the Japanese population. BMC Med Genet. 2001;2(1):7. doi: 10.1186/1471-2350-2-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Fassbender W, et al. VDR gene polymorphisms are overrepresented in German patients with type 1 diabetes compared to healthy controls without effect on biochemical parameters of bone metabolism. Horm Metab Res. 2002;34(06):330–337. doi: 10.1055/s-2002-33262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Gyorffy B, et al. Gender-specific association of vitamin D receptor polymorphism combinations with type 1 diabetes mellitus. Eur J Endocrinol. 2002;147(6):803–808. doi: 10.1530/eje.0.1470803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Turpeinen H, et al. Vitamin D receptor polymorphisms: no association with type 1 diabetes in the Finnish population. Eur J Endocrinol. 2003;149(6):591–596. doi: 10.1530/eje.0.1490591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Martí G, Audí L, Esteban C, Oyarzábal M, Chueca M, Gussinyé M, Yeste D, Fernández-Cancio M, Andaluz P, Carrascosa A. Asociación de los polimorfismos del gen del receptor de la vitamina D con la diabetes mellitus tipo 1 en dos poblaciones españolas. Med Clín. 2004;123(8):286–290. doi: 10.1016/s0025-7753(04)74494-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Pedro JS, et al. Heterogeneity of vitamin D receptor gene association with celiac disease and type 1 diabetes mellitus. Autoimmunity. 2005;38(6):439–444. doi: 10.1080/08916930500288455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Zemunik T, et al. FokI polymorphism, vitamin D receptor, and interleukin-1 receptor haplotypes are associated with type 1 diabetes in the Dalmatian population. J Mol Diagn. 2005;7(5):600–604. doi: 10.1016/S1525-1578(10)60593-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Capoluongo E, et al. Slight association between type 1 diabetes and “ff” VDR FokI genotype in patients from the Italian Lazio region. Lack of association with diabetes complications. Clin Biochem. 2006;39(9):888–892. doi: 10.1016/j.clinbiochem.2006.05.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lemos MC, et al. Lack of association of vitamin D receptor gene polymorphisms with susceptibility to type 1 diabetes mellitus in the Portuguese population. Hum Immunol. 2008;69(2):134–138. doi: 10.1016/j.humimm.2008.01.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Israni N, et al. Interaction of vitamin D receptor with HLA DRB1* 0301 in type 1 diabetes patients from North India. PLoS One. 2009;4(12):e8023. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0008023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Mory DB, et al. Prevalence of vitamin D receptor gene polymorphisms FokI and BsmI in Brazilian individuals with type 1 diabetes and their relation to β-cell autoimmunity and to remaining β-cell function. Hum Immunol. 2009;70(6):447–451. doi: 10.1016/j.humimm.2009.03.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Yavuz DG, et al. Vitamin D receptor gene BsmI, FokI, ApaI, TaqI polymorphisms and bone mineral density in a group of Turkish type 1 diabetic patients. Acta Diabetol. 2011;48(4):329–336. doi: 10.1007/s00592-011-0284-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Yokota I, et al. Association between vitamin D receptor genotype and age of onset in juvenile Japanese patients with type 1 diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2002;25(7):1244. doi: 10.2337/diacare.25.7.1244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Bonakdaran S, et al. Vitamin D receptor gene polymorphisms in type 1 diabetes mellitus: a new pattern from Khorasan province, Islamic Republic of Iran. 2012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]