Abstract

Caffeine is one of the most used ergogenic aid for physical exercise and sports. However, its mechanism of action is still controversial. The adenosinergic hypothesis is promising due to the pharmacology of caffeine, a nonselective antagonist of adenosine A1 and A2A receptors. We now investigated A2AR as a possible ergogenic mechanism through pharmacological and genetic inactivation. Forty-two adult females (20.0 ± 0.2 g) and 40 male mice (23.9 ± 0.4 g) from a global and forebrain A2AR knockout (KO) colony ran an incremental exercise test with indirect calorimetry (V̇O2 and RER). We administered caffeine (15 mg/kg, i.p., nonselective) and SCH 58261 (1 mg/kg, i.p., selective A2AR antagonist) 15 min before the open field and exercise tests. We also evaluated the estrous cycle and infrared temperature immediately at the end of the exercise test. Caffeine and SCH 58621 were psychostimulant. Moreover, Caffeine and SCH 58621 were ergogenic, that is, they increased V̇O2max, running power, and critical power, showing that A2AR antagonism is ergogenic. Furthermore, the ergogenic effects of caffeine were abrogated in global and forebrain A2AR KO mice, showing that the antagonism of A2AR in forebrain neurons is responsible for the ergogenic action of caffeine. Furthermore, caffeine modified the exercising metabolism in an A2AR-dependent manner, and A2AR was paramount for exercise thermoregulation.

Subject terms: Metabolism, Neurophysiology

Introduction

The natural plant alkaloid caffeine (1,3,7-trimethylxantine) is one of the most common ergogenic substances for physical activity practitioners and athletes1–10. Caffeine increases endurance1,8–12, intermittent7,13,14 and resistance4,15 exercise in humans. In rodents, its ergogenic effects are conserved because caffeine increases running time on the treadmill at constant16,17 and accelerated speeds18,19. Sports sciences promote nonselective phosphodiesterase (PDE) inhibition7,8 and increased calcium mobilization2,7,8 as mechanisms for these ergogenic effects. However, the primary pharmacological effect of caffeine is the nonselective antagonism of adenosine A1 and A2A receptors (A1R, A2AR)20–23.

Adenosine can act as an inhibitory modulator of the Central Nervous System (CNS) associated with tiredness and drowsiness24–29. During exercise, circulating ADP/AMP/adenosine levels increase due to ATP hydrolysis30,31. However, there is still no substantial evidence on the role of adenosine in exercise-induced fatigue. It is just known that the nonselective A1R and A2AR agonist 5′-(N-ethylcarboxamido)adenosine (NECA), injected into the rat brain, abolishes the ergogenic effects of caffeine16.

Since there is increasing evidence that the adenosine modulation system critically controls allostasis29 and A2AR have a crucial role in the ability of caffeine to normalize brain function30, we hypothesized that caffeine decreases fatigue during exercise through antagonism of A2AR in the CNS. We combined the use of pharmacology (SCH 58261 and caffeine) and transgenic mice with tissue-selective deletion of A2AR, to test this hypothesis in an incremental running test with indirect calorimetry (or ergospirometry). A2AR knockout (KO) mice allow assessing if the ergogenic effect of caffeine persists in the absence of A2AR; the use of SCH 58261, the current reference for A2AR antagonists32,33, allows directly assessing the ergogenic role of A2AR. SCH 58261 has excellent selectivity and affinity for A2AR32,33, and affords motor benefits in animal models of Parkinson's disease as does caffeine, supporting the recent FDA approval of the A2AR antagonist Istradefylline for PD treatment33. Our goal is to assess the ergogenicity of A2AR using the pharmacological and genetic tools described above.

Methods

Animals and A2AR KO colony

We used 40 male (23.9 ± 0.4 g, 8–10 weeks old) and 42 female mice (20.0 ± 0.2 g, 8–10 weeks old) from our global-A2AR (A2AR KO) and forebrain-A2AR KO (fb-A2AR KO) inbred colony34,35 and wild type littermates. The sample size for ANOVA comparison had α = 0.05 and β = 0.8.

The inactivation of exon 2 of A2AR in a near congenic (N6) C57BL/6 genetic background was the method of generating A2AR KO mice36,37. We also have good experience with treadmill running in this strain38–40. A2AR KO mice and wild type littermates were matched for sex and age for each experiment. The Cre-loxP strategy, crossing floxed A2AR mice with mice expressing CRE under the forebrain-selective promoter CAM-kinase 2, allows generating fb-A2AR KO mice, as previously described34,41. We used global A2AR KO females and fb-A2AR KO males due to the characteristic of our colony.

Mice were housed in collective cages in HEPA-filtered ventilated racks (n = 3–5) under a controlled environment (12 h light–dark cycle, lights on at 7 AM, and room temperature of 21 ± 1 °C) with ad libitum access to food and water. Housing and handling were performed according to European Union guidelines (2010/63). The Ethical Committee of the Center for Neuroscience and Cell Biology (University of Coimbra) approved the study.

Drugs

7-(2-phenylethyl)-5-amino-2-(2-furyl)-pyrazolo-[4,3-e]-1,2,4-triazolo[1,5-c]pyrimidine (SCH 58261) was solubilized in 10% dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) in 0.9% NaCl – saline. Caffeine was dissolved in saline. SCH 58261 and caffeine were freshly prepared and administered intraperitoneally (volume of 10 mL/kg body mass). Caffeine, DMSO, and NaCl were obtained from Sigma-Aldrich and SCH 58261 from Tocris. The doses used of SCH 58261 (1 mg/kg) and caffeine (15 mg/kg) were based on our previous experience in the use of these compounds42,43 and pilot studies.

Experimental design

Fig.S1 shows the experimental design. The habituation of handling, injections (0.9% NaCl, i.p.), and moving treadmill (15 cm/s) occurred in the first three days of the experiment. The animals were treated with SCH 58261 (1 mg/kg, i.p.) and caffeine (15 mg/kg, i.p.) on days 4 and 5, 15 min before testing in the open field (4th day) and ergospirometry (5th day). The experiments took place between 9 AM and 5 PM, within the light phase of the mouse dark/light cycle, in a sound-attenuated and temperature/humidity controlled room (20.3 ± 0.6 °C and 62.8 ± 0.4% H2O) under low-intensity light (≈ 10 lx). The open field apparatus and the treadmill were cleaned with 10% ethanol between individual experiments. The allocation for the experimental groups was random. For each test, the experimental unit was an individual animal.

Open field

Mice explored an unaccustomed open field (38 × 38 cm) for 15 min. Locomotion was analyzed using an ANY-Maze video tracking system (Stoelting Co.).

Ergospirometry

Mice were accustomed to a single-lane treadmill (Panlab LE8710, Harvard apparatus) at speed 15 cm/s (10 min, slope 5°, 0.2 mA) with a 24 h interval between each habituation session (Fig. S1). The incremental running protocol started at 15 cm/s, with an increment of 5 cm/s every 2 min at 5° inclination40. The exercise lasted until running exhaustion, defined by the inability of the animal to leave the electrical grid for 5 s40,44.

Oxygen uptake (V̇O2) and carbon dioxide production (V̇CO2) were estimated in a metabolic chamber (Gas Analyzer ML206, 23 × 5 × 5 cm, AD Instruments, Harvard) coupled to the treadmill. The animals remained in the chamber for 15 min before exercise testing. Atmospheric air (≈21% O2, ≈0.03% CO2) was renewed at a rate 120 mL/min, using the same sampling rate for the LASER oxygen sensor (Oxigraf X2004, resolution 0.01%) and infrared carbon dioxide sensor (Servomex Model 15050, resolution 0.1%).

We estimated the running and critical power output for a treadmill based on a standard conversion of the vertical work, body weight, and running speed40,45,46. Running power is the sum (Σ) of all stages of the exercise test, and critical power is the running work performed above V̇O2max.

Vaginal cytology

We evaluated the estrous cycle immediately after the exercise test, through 4–5 consecutive vaginal lavages (with 40–50 μL of distilled H2O) then mounted on gelatinized slides (76 × 26 mm)47,48. These procedures lasted no more than 3–5 min, and there were no significant time delays between behavioral experiments and fluid collection for vaginal cytology.

The vaginal smear was desiccated at room temperature and covered with 0.1% crystal violet for 1 min, then twice washed with 1 mL H2O and desiccated at room temperature47,48. The slides were mounted with Eukitt medium (Sigma-Aldrich) and evaluated under an optical microscope at 1x, 5x, and 20x (Zeiss Axio Imager 2). We evaluated three cell types for determining the estrous cycle: nucleated epithelial cells, cornified epithelial cells, and leukocytes. Cellular prevalence defined proestrus (nucleated), estrus (cornified), metestrus (all types in the same proportion), and diestrus (leukocytes)47,48.

Thermal imaging

An infrared (IR) camera (FLiR C2, emissivity 0.95, FLiR Systems) placed overtop (25 cm height) of a plastic tube (25 cm diameter) was used to acquire a static dorsal thermal image40,49,50. IR images were taken immediately before and after exercise tests, namely at resting and recovery (Fig. 1H), respectively. IR images were analyzed with FLiR Tools software (Flir, Boston).

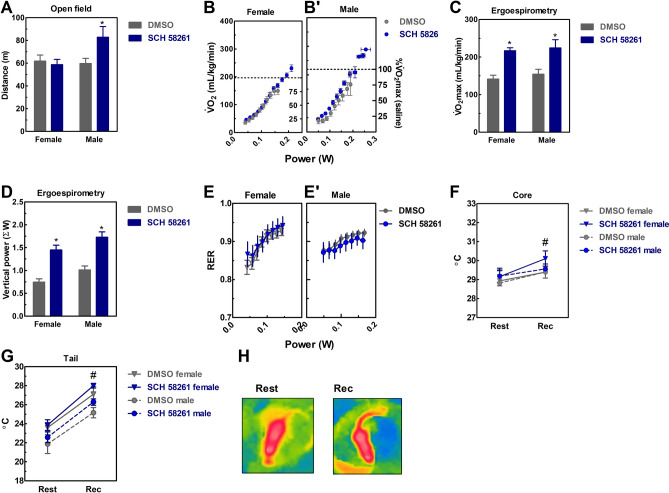

Figure 1.

Effects of SCH 58261 (1 mg/kg, i.p.) on locomotion (A), ergospirometry (B–E), and thermoregulation (F–H) of wild type male and female mice. (A) SCH 58261 was psychostimulant only in males. (B) The dotted line represents the V̇O2max of the DMSO group. Ergospirometry increased V̇O2 (B), running power (B), and metabolic rate (E) until the animals reached fatigue. SCH 58261 was ergogenic in both sexes, as it increased V̇O2max (C) and running power (D). The animals presented exercise-induced core and tail hyperthermia (H), which was not 58261 modified by SCH (F–G). Sex was a significant factor in decreasing maximum responses to V̇O2 (C) and running power (D), and increasing core and tail temperature in females. Data are presented as mean ± SEM. N = 8–9 animals/group for 12 independent experiments. *P < 0.05 vs. DMSO (Two-way ANOVA followed by Newman-Keuls post hoc test). # P < 0.05 vs. rest (Repeated measures ANOVA followed by Bonferroni post hoc test). DMSO dimethyl sulfoxide. Rec recovery. RER Respiratory Exchange Ratio. V̇O2 oxygen consumption.

Statistics

Data are presented as mean ± SEM in graphs built using the GraphPad Prism version 5.00 for Windows, GraphPad Software, San Diego California USA, www.graphpad.com.

Statistical analyzes were performed according to an intention-to-treat principle using StatSoft, Inc. (2007). STATISTICA (data analysis software system), version 8.0. www.statsoft.com. ANOVA two-way was used to evaluate open field, V̇O2max, running power, and resting and recovery temperature, followed by Newman-Keuls post hoc test. The evolution of submaximal V̇O2, running power, respiratory exchange ratio (RER), and heating were evaluated by ANOVA for repeated measures followed by Bonferroni post hoc test. The differences were considered significant when P < 0.05.

Effect sizes (Cohen's partial eta-square η2) were calculated for between-group changes in mean differences for V̇O2max, running power, and temperature, where a Cohen's η2 was used for ANOVA, defined as 0.01 small, 0.09 medium, and 0.25 large.

Results

SCH 58261: pharmacological inactivation of A2AR is ergogenic

SCH 58261 was psychostimulant for males, but not for females, since SCH 58261 only increased male locomotion in the open field (F1,39 = 4.5, η2 = 0.1, β = 0.54, 95% CI 58.8–72.1, P < 0.05, Fig. 1A).

The running power of females (F7,77 = 221, P < 0.05, Fig. 1B) and males (F7,84 = 183, P < 0.05, Fig. 1B') increased at each stage of the exercise test. Submaximal V̇O2 also increased to the maximum (V̇O2max, dotted line) of females (F8,77 = 168, P < 0.05, Fig. 1B) and males (F7,84 = 14.3, P < 0.05, Fig. 1B'). Female (F8,70 = 180, P < 0.05, Fig.S2A) and male (F8,70 = 164, P < 0.05, Fig.S2B) submaximal V̇CO2 kinetics was similar to V̇O2. SCH 58261 had no effect on these submaximal values.

We demonstrated for the first time that SCH 58261 is ergogenic since SCH 58261 increased V̇O2max (F1,36 = 27.7, η2 = 0.44, β = 0.99, 95% CI 0.16–0.2, P < 0.5, Fig. 1C) and running power (F1,35 = 55, η2 = 0.61, β = 1.0, 95% CI 1.0–1.3, P < 0.05, Fig. 1D) in both sexes.

SCH 58261 had no effect on increasing RER of females (F7,70 = 6.9, P < 0.5, η2 = 0.43, β = 0.99, Fig. 1E) and males (F7,84 = 9.4, η2 = 0.57, β = 0.99, P < 0.5, Fig. 1E’). Exercise test raised the animals' core (F1,26 = 5.5, η2 = 0.17, β = 0.62, 95% CI 28.7–29.39, P < 0.05, Fig. 1F) and tail temperature (F1,22 = 81, η2 = 0.78, β = 0.99, 95% CI 24.2–25.6, P < 0.05, Fig. 1G), with no effect of SCH 58261. Figure 1 shows the heating of the mouse's tail in post-exercise recovery (rec) in relation to rest. Three females at estrus (Fig.S3C) were excluded from temperature experiments due to large exercise-induced tail hyperthermia40. The previous results refer to females in diestrus (Fig.S3A), proestrus (Fig.S3B), and metestrus (Fig.S3D).

Caffeine is not ergogenic in global A2AR knockouts

Caffeine was psychostimulant based on its ability to increase locomotion in the wild type mice (F1,36 = 5.8, η2 = 0.13, β = 0.64, 95% CI 55.9–71.6, P < 0.05, Fig. 2A), an effect not seen in A2AR KO mice.

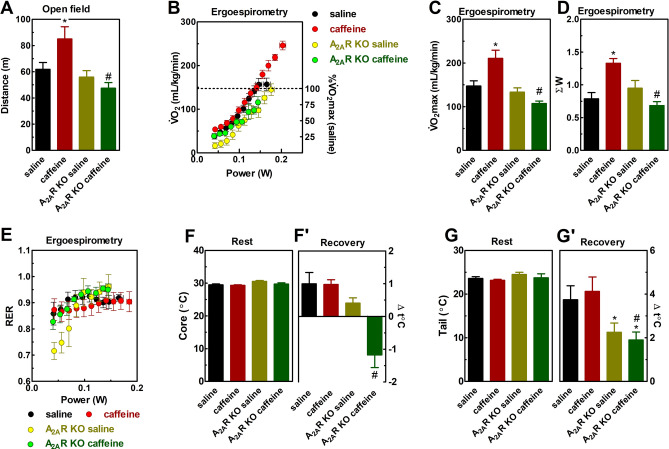

Figure 2.

Effects of caffeine (15 mg/kg, i.p.) in wild type and global A2AR KO mice on locomotion (A), ergospirometry (B–E), and thermoregulation (F–G) of female mice. (A) Caffeine displayed a psychostimulant effect in the open field in wild type mice, but not in A2AR KO mice. Ergospirometry increased V̇O2 (B), running power (B), and metabolic rate (E) until the animals reached fatigue. The dotted line represents the V̇O2max of the wild type-saline group (B). Caffeine increased V̇O2max (C) and running power (D) of wild type, but not A2AR KO mice. Exercise test induced hyperthermia, which was not affected by caffeine in wild type mice, whereas caffeine caused a hypothermic response in A2AR KO mice (F and G). Genotype was a significant factor for V̇O2max (C), running power (D), resting (F), and recovery (F' and G') temperatures. Data are described as mean ± SEM. N = 8–9 animals/group for 12 independent experiments. *P < 0.05 vs. saline and # P < 0.05 vs. caffeine (Two-way ANOVA followed by Newman-Keuls post hoc test). A2AR—adenosine A2A receptor. KO—knockout. Rec recovery. RER Respiratory Exchange Ratio. V̇O2 oxygen consumption.

Figure 2B shows the progressive increase in submaximal V̇O2 (F7,196 = 255, P < 0.05), V̇CO2 (F7,196 = 189, P < 0.05, Fig.S2C) and running power (F7,210 = 6,243, P < 0.05) at speeds 35–50 cm/s, with less V̇O2 for A2AR KO mice. Caffeine was ergogenic but only in mice expressing A2AR. Caffeine improved V̇O2max (F1,33 = 12.6, η2 = 0.28, β = 0.93, 95 CI 0.12–0.17, P < 0.05, Fig. 2C) and running power (F1,32 = 22.3, η2 = 0.4, β = 0.99, 95% CI 0.84–1.09, P < 0.05, Fig. 2D) of wild type mice. The increase in critical power was 43.1 ± 7.1% concerning controls. A2AR KO did not display the ergogenic effects of caffeine.

Caffeine slowed the progression of RER in the wild type mice (F7,133 = 3.5, η2 = 0.15, β = 0.96, P < 0.05, Fig. 2E). Resting core (Fig. 2F) and tail (Fig. 2G) temperatures were similar between groups. Exercise increased the core (F1,24 = 0.16, η2 = 0.99, β = 0.99, 95% CI 29.5–30.2, P < 0.05, Fig. 2F’) and tail (F1,25 = 82, η2 = 0.73, β = 0.99, 95% CI 26.2–27.6, P < 0.05, Fig. 2G’) temperature of wild type animals. Caffeine did not change the exercise-induced core and tail heating, which was lower in the A2AR KO mice. Core temperature even dropped in caffeine-treated A2AR KO mice, as expected from the participation of A1R, also targeted by caffeine, on the control of body temperature51.

Knocking out neuronal A2AR abrogates the ergogenic effects of caffeine

The psychostimulant effect of caffeine was operated by A2AR since caffeine increased the locomotion of wild type males in the open field (F1,34 = 8.6, η2 = 0.11, β = 0.55, 95% CI 65.5–78.3, P < 0.05, Fig. 3A), but not in fb-A2AR KO mice.

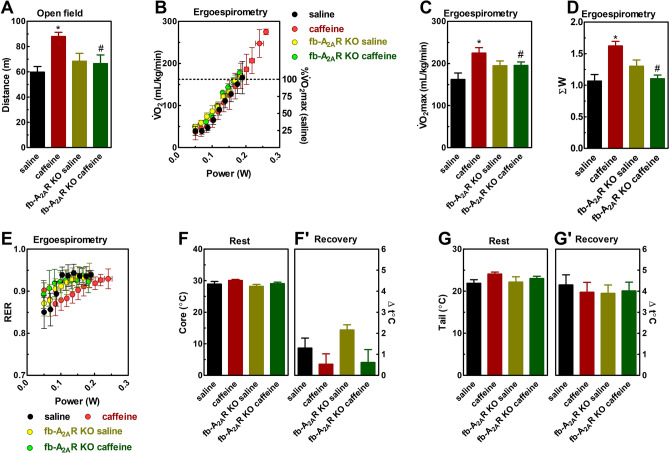

Figure 3.

Effects of caffeine (15 mg/kg, i.p.) in wild type and forebrain A2AR KO mice on motor behavior (A), ergospirometry (B–E), and thermoregulation (F, G) of male mice. (A) Caffeine displayed a psychostimulant effect in the open field in wild type mice, but not in forebrain-A2AR KO mice. Ergospirometry increased V̇O2 (B), running power (B), and metabolic rate (E) until the animals reached fatigue. The dotted line represents the V̇O2max of the wild type-saline group (B). Caffeine increased V̇O2max (C) and running power (D) of wild type, but not forebrain A2AR KO mice. Resting core (F) and tail (G) temperature and tail heating (G') were similar between groups. Data are presented as mean ± SEM. N = 8–9 animals/group for 12 independent experiments. *P < 0.05 vs. saline and #P < 0.05 vs. caffeine (Two-way ANOVA followed by Newman-Keuls post hoc test). A2AR adenosine A2A receptor, fb forebrain, KO knockout, Rec recovery, RER respiratory exchange ratio. V̇O2 oxygen consumption.

Submaximal V̇O2 (F7,147 = 329, P < 0.05, Fig. 3B) and V̇CO2 (F7,154 = 359, P < 0.05, Fig.S2D) increased during the exercise test without caffeine and genotype effects. Caffeine was ergogenic but only in mice expressing neuronal A2AR. Caffeine increased V̇O2max (F1,31 = 5.7, η2 = 0.16, β = 0.64, 95% CI 0.17–0.21, P < 0.05, Fig. 3C) and running power (F1,29 = 4.4, η2 = 0.13, β = 0.98, 95% CI 1.16–1.39, P < 0.05, Fig. 3D) of wild type animals. The increase in critical power was 31.9 ± 4.7% concerning controls. Most importantly, caffeine was not ergogenic in fb-A2AR KO mice.

The increase in RER during the exercise test was lower in animals treated with caffeine (F7,119 = 3.6, η2 = 0.17, β = 0.97, P < 0.05, Fig. 3E), wild type, and fb-A2AR KO. Resting and recovery core temperatures were similar in all groups (Figs. 3F and Fig. 3G). The exercise test did not change the core temperature (Fig. 3F’). However, exercise heated the mice's tail in a similar way between groups (F1,22 = 102, η2 = 0.69, β = 0.99, 95% CI 24.9–26.4, P < 0.05, Fig. 3G').

Discussion

Neuronal A2AR antagonism is ergogenic

Caffeine increases exercise performance in rodents16,17,19,26,40 and humans1,4,8–15,24,28,51,52. Our results show the key role of A2AR in the ergogenic effects of caffeine using pharmacological and genetic tools. Thus, the potent and selective A2AR antagonist SCH 58261 displayed an ergogenic effect similar to that of caffeine, and the ergogenic effect of caffeine was abrogated in A2AR KO mice.

SCH 58261 and caffeine improved V̇O2max, running and critical power of wild type mice. These results are in line with the improved running time observed in caffeine-treated rats16,26,53 and mice19. Further evidence for the ergogenic effect of caffeine is based on its ability to increase muscle power and endurance output in rodents54–58. For the first time, we demonstrated that the selective antagonism of A2AR is ergogenic. Also, for the first time, we demonstrated that the genetic inactivation of A2AR impaired the ergogenic effects of caffeine. Tissue-specific A2AR KO selectively in forebrain neurons further allowed showing that these ergogenic effects of caffeine are due to the antagonism of A2AR in forebrain neurons. Thus, we suggest that caffeine decreases central fatigue during exercise. Moreover, caffeine decreased RER in the submaximal stages of the exercise test, an effect also abrogated in A2AR KO mice. However, exercise-induced core and tail hyperthermia were similar among animals treated with SCH 58261 or caffeine, except for A2AR KO mice, suggesting possible A1R-A2AR-mediated interactions56,57 in the temperature control51.

Selective A2AR antagonism is psychostimulant in males, not females

We assessed the baseline motor behavior due to the motor nature of the running test, without any motor impairment found related to the different genotypes and treatments. Thus, the observed differences were not due to impaired animals' motor behavior. We also assessed the psychostimulant effects of caffeine and SCH 5826134. Notably, the effects of caffeine were abrogated in A2AR KO mice, and SCH 58261 did not modify locomotion in female mice. These results corroborate the robust evidence showing the psychostimulant effects of caffeine in male rodents58. However, little is known about the role of sexual dimorphism in adenosine signaling59–63. The absence of a psychostimulating effect of SCH 58261 in females is on step ahead, in notable agreement with the reported ability of the anxiolytic effect of SCH 58261 in males59–61 but not in females60. However, these differences did not disturb the ergogenic effects of SCH 58261 on females. Future studies will better understand sex differences in adenosine signaling, which was not the aim of this study.

The neuropharmacology of the ergogenic effects of SCH 58261 and caffeine

Adenosine is a potent purine that modulates CNS signaling and functions from its main A1R and A2AR21,23,29,62. Here, caffeine (nonspecific A1R and A2AR antagonist) and SCH 58261 (selective A2AR antagonist) similarly increased the V̇O2max, running power, and critical power of exercising male and female mice. Most importantly, these ergogenic effects were abrogated by the selective deletion of A2AR in forebrain neurons, which indicates the key role of CNS A2AR as an ergogenic mechanism. The basal nuclei, namely the striatum, is the brain region with the highest density of A2AR34,35,37,63, which prompts the hypothesis that the A2AR antagonism in the basal ganglia might mediate the ergogenic effect of SCH 58261. In resting and running rodents, caffeine intake can result in a concentration of caffeine of 50 µM in the brain19,64. This concentration is close to the EC50 of caffeine (40 µM) to antagonize A1R and A2AR in the CNS23. Since caffeine was not ergogenic in fb-A2AR KO mice, it is concluded that forebrain A2AR signal the ergogenic effects of caffeine. This provides a direct demonstration of the involvement of neuronal A2AR in the ergogenic effects of caffeine, as suggested by two previous reports showing that NECA prevented the ergogenic effects of caffeine in rats16 and, conversely, that systemic caffeine reversed the poor running performance of NECA-treated rats24. Although nonselective, the pharmacological use of NECA demonstrated that adenosine receptors are crucial for the ergogenic effects of caffeine16,26,53. We now identified A2AR, specifically located in forebrain neurons, as responsible for this ergogenicity of caffeine.

The neurological effects of caffeine highlight its action on the CNS. Caffeine decreases the rate of perceived exertion4–6,9,65, pain4,6,64,66,67, central and mental fatigue during exercise24,28,68,69, indicating that caffeine attenuates mental fatigue during exercise. Caffeine also improves performance expectations70, cognitive and executive functions65,71–73, and vigor74 in exercising subjects. The contribution of the CNS-mediated effects on exercise-induced fatigue conceptualizes central fatigue24,28,51,52,68,75. Caffeine reduces saccadic eyes fatigue24,28,also, the cortical silence of fatigued ankle muscles51,52. Moreover, caffeine increases spinal excitability76 and cortical motor area potentiation68 after exhausting exercise.

Caffeine decreases RER in mice expressing peripheral A2AR

Caffeine decreases the RER in submaximal exercise in humans1,77,78 and rats79. For the first time, we provide evidence that this metabolic effect involves a modification of the A2AR function. In the past, the inhibition of phosphodiesterase and increased intracellular calcium mobilization2,7,8,80 were the proposed mechanisms. However, these proposals are inconsistent with pharmacological data: caffeine has an EC50 for adenosine antagonism of 40 µM, 1,000 mM for phosphodiesterase inhibition, and 3,000 mM for Ca2+-triggered muscle contraction23. Higher caffeine concentrations cause toxicity (above 200 µM) and lethality (above 500 µM)23. Thus, biological effects for caffeine must be in the range below 100 µM. We have previously shown that caffeine reaches a plasma peak of 10 µM after caffeine intake (6 mg/kg) in running mice19. The metabolic effects of caffeine during exercise are currently associated with increased activity of the autonomic nervous system (ANS)1,19,77,78, including high blood adrenaline and lactate levels, tachycardia and increased blood pressure. However, we must recognize the limitations of lung-based RER measures and their effects on metabolism, due to the possible artifacts such as hyperventilation and disturbances in the acid–base balance.

Adenosine receptors are crucial for exercise-induced hyperthermia

The temperature changes observed were dependent on sex and genotype. The exercise test improved V̇O2, an index of heat production26, but the core temperature increased only in females. The tail temperature, an index of heat loss26, increased in both sexes. These results are in line with previous results from our group40. Caffeine and SCH 58261 did not modify these thermal responses to the exercise test. In males, tail heating of fb-A2AR KO mice was also similar to that of the wild type mice. However, the thermal response of the global A2AR KO females was different, indicating a peripheral role of these receptors, known to regulate body temperature51.

NECA (nonspecific A1R and A2AR agonist) causes core hypothermia in rats and rabbits26,76, an effect inhibited by 8-phenyltheophylline (a potent and selective antagonist for A1R and A2AR that crosses the blood–brain barrier, BBB)76, but unaffected by 8-(p-sulfophenyl)theophylline (another potent adenosine receptor antagonist with little BBB penetration)76, indicating a centrally-mediated effect. In the case of A2AR, its role in regulating body temperature is controversial81. The selective A2AR agonist 2-p-(2-carboxyethyl)-phenethylamino-5′-N-ethylcarboxamidoadenosine-hydrochloride (CGS 21680) induces hyperthermia in rats82 and mice83. We now show that SCH 58261 does not change resting and recovery temperature. This evidence suggests that the peripheral activation of A2AR can induce hypothermia in rodents, but this mechanism does not seem to be physiologically engaged as gauged by the lack of effects of the pharmacological or genetic blockade of A2AR. The previous data are from animals at rest—animals with CNS A2AR deletion present normal hyperthermia response during exercise. However, global A2AR KO displays a decreased response, even hypothermia, when treated with caffeine. Thus, A2AR seems to undergo a gain of function in the periphery during exercise. This data reinforces the well-known role of A1R in hypothermia81. Circulating adenosine levels increase during exercise30,31, and global A2AR KO imbalance appears to increase the A1R role, signaling hypothermia even after exercise. These results are limited to the use of infrared temperature, as we have not measured rectal temperature due to interference (vaginal manipulation) in the evaluation of the estrous cycle of females. Also, we kept the same methodology in males.

Conclusion

In summary, we have now demonstrated that A2AR antagonism is a mechanism of action for ergogenicity, as SCH 58261 was ergogenic. Furthermore, we showed that the antagonism of forebrain A2AR was the mechanism underlying the ergogenic effect of caffeine since caffeine was not ergogenic in fb-A2AR KO. The use of selective A2AR KO in forebrain neurons further reinforces the ergogenic role of caffeine in decreasing central fatigue, with possible involvement of decreased perceived exertion, pain, and mental fatigue in humans. Despite methodological limitations, our data further suggest that caffeine modified the exercising metabolism in an A2AR-dependent manner and that A2AR is essential for exercise thermoregulation.

Supplementary Information

Acknowledgments

The work was supported by Prémio Maratona da Saúde, CAPES-FCT (039/2014), CNPq (302234/2016-0), FCT (POCI-01-0145-FEDER-03127), and ERDF through Centro 2020 (project CENTRO-01-0145-FEDER-000008:BrainHealth 2020 and CENTRO-01-0246-FEDER-000010). A.S.A.Jr is a CNPq fellow. We would like to acknowledge Flávio N. F. Reis and Frederico C. Pereira (IBILI—Institute for Biomedical Imaging and Life Sciences, University of Coimbra) for making available the treadmill and gas analyzer.

Author contributions

A.S.A.Jr designed and performed the experiments, prepared the figures, and wrote the manuscript. A.E.S performed the experiments. P.M.C. designed the experiments and wrote the manuscript. R.A.C. designed the experiments and wrote the manuscript. All authors revised the manuscript.

Data availability

The datasets generated and analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Competing interests

RAC is a scientific consultant for the Institute for Scientific Information on Coffee (ISIC). All other authors declare no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

is available for this paper at 10.1038/s41598-020-69660-1.

References

- 1.Graham TE, Spriet LL. Metabolic, catecholamine, and exercise performance responses to various doses of caffeine. J. Appl. Physiol. 1995 doi: 10.1152/jappl.1995.78.3.867. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tarnopolsky MA. Effect of caffeine on the neuromuscular system: potential as an ergogenic aid. Appl. Physiol. Nutr. Metab. 2008 doi: 10.1139/H08-121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.McNaughton LARS. Two levels of caffeine ingestion on blood lactate and free fatty acid responses during incremental exercise. Res. Q. Exerc. Sport. 1987 doi: 10.1080/02701367.1987.10605458. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Grgic J, Mikulic P. Caffeine ingestion acutely enhances muscular strength and power but not muscular endurance in resistance-trained men. Eur. J. Sport Sci. 2017 doi: 10.1080/17461391.2017.1330362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Doherty M, Smith PM, Hughes MG, Davison RCR. Caffeine lowers perceptual response and increases power output during high-intensity cycling. J. Sports Sci. 2004 doi: 10.1080/02640410310001655741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Duncan MJ, Stanley M, Parkhouse N, Cook K, Smith M. Acute caffeine ingestion enhances strength performance and reduces perceived exertion and muscle pain perception during resistance exercise. Eur. J. Sport Sci. 2013 doi: 10.1080/17461391.2011.635811. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Davis JK, Green JM. Caffeine and anaerobic performance: Ergogenic value and mechanisms of action. Sports Med. 2009;39:813–832. doi: 10.2165/11317770-000000000-00000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Graham TE, Rush JWE, van Soeren MH. Caffeine and exercise: Metabolism and performance. Can. J. Appl. Physiol. 1994 doi: 10.1139/h94-010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Stadheim HK, Spencer M, Olsen R, Jensen J. Caffeine and performance over consecutive days of simulated competition. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 2014 doi: 10.1249/MSS.0000000000000288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jackman M, Wendling P, Friars D, Graham TE. Metabolic, catecholamine, and endurance responses to caffeine during intense exercise. J. Appl. Physiol. 1996 doi: 10.1152/jappl.1996.81.4.1658. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Flinn S, Gregory J, McNaughton LR, Tristram S, Davies P. Caffeine ingestion prior to incremental cycling to exhaustion in recreational cyclists. Int. J. Sports Med. 1990 doi: 10.1055/s-2007-1024789. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Spriet LL, et al. Caffeine ingestion and muscle metabolism during prolonged exercise in humans. Am. J. Physiol. Endocrinol. Metab. 1992 doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.1992.262.6.e891. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mohr M, Nielsen JJ, Bangsbo J. Caffeine intake improves intense intermittent exercise performance and reduces muscle interstitial potassium accumulation. J. Appl. Physiol. 2011 doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.01028.2010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Trice I, Haymes EM. Effects of caffeine ingestion on exercise-induced changes during high-intensity, intermittent exercise. Int. J. Sport Nutr. 1995 doi: 10.1123/ijsn.5.1.37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Van Soeren MH, Sathasivam P, Spriet LL, Graham TE. Caffeine metabolism and epinephrine responses during exercise in users and nonusers. J. Appl. Physiol. 1993 doi: 10.1152/jappl.1993.75.2.805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Davis JM, et al. Central nervous system effects of caffeine and adenosine on fatigue. Am. J. Physiol. Regul. Integr. Comp. Physiol. 2003 doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00386.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Claghorn GC, Thompson Z, Wi K, Van L, Garland T. Caffeine stimulates voluntary wheel running in mice without increasing aerobic capacity. Physiol. Behav. 2017 doi: 10.1016/j.physbeh.2016.12.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Aguiar AS, Speck AE, Canas PM, Cunha RA. Neuronal adenosine A2A receptors signal ergogenic effects of caffeine. bioRxiv. 2020 doi: 10.1101/2020.04.02.021923. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Solano, A. F., da Luz Scheffer, D., de Bem Alves, A. C., Jr, A.S.A. & Latini, A. Potential pitfalls when investigating the ergogenic effects of caffeine in mice. J. Syst. Integr. Neurosci. (2017). 10.15761/jsin.1000156

- 20.Fredholm BB, Bättig K, Holmén J, Nehlig A, Zvartau EE. Actions of caffeine in the brain with special reference to factors that contribute to its widespread use. Pharmacol. Rev. 1999;51:83–133. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fredholm BB. Adenosine, adenosine receptors and the actions of caffeine. Pharmacol. Toxicol. 1995 doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0773.1995.tb00111.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Svenningsson P, Nomikos GG, Ongini E, Fredholm BB. Antagonism of adenosine A(2A) receptors underlies the behavioural activating effect of caffeine and is associated with reduced expression of messenger RNA for NGFI-A and NGFI-B in caudate-putamen and nucleus accumbens. Neuroscience. 1997 doi: 10.1016/S0306-4522(97)00046-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Fredholm BB. On the mechanism of action of theophylline and caffeine. Acta Med. Scand. 1985 doi: 10.1111/j.0954-6820.1985.tb01650.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Connell CJW, Thompson B, Turuwhenua J, Srzich A, Gant N. Fatigue-related impairments in oculomotor control are prevented by norepinephrine-dopamine reuptake inhibition. Sci. Rep. 2017 doi: 10.1038/srep42726. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Yohn SE, et al. Effort-related motivational effects of the pro-inflammatory cytokine interleukin-6: pharmacological and neurochemical characterization. Psychopharmacology. 2016 doi: 10.1007/s00213-016-4392-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zheng X, Hasegawa H. Administration of caffeine inhibited adenosine receptor agonist-induced decreases in motor performance, thermoregulation, and brain neurotransmitter release in exercising rats. Pharmacol. Biochem. Behav. 2016 doi: 10.1016/j.pbb.2015.10.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Nunes EJ, et al. Differential effects of selective adenosine antagonists on the effort-related impairments induced by dopamine D1 and D2 antagonism. Neuroscience. 2010 doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2010.05.068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Connell CJW, et al. Fatigue related impairments in oculomotor control are prevented by caffeine. Sci. Rep. 2016 doi: 10.1038/srep26614. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Snyder SH. Adenosine as a neuromodulator. Annu. Rev. Neurosci. 1985 doi: 10.1146/annurev.ne.08.030185.000535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Moritz CEJ, et al. Altered extracellular ATP, ADP, and AMP hydrolysis in blood serum of sedentary individuals after an acute, aerobic, moderate exercise session. Mol. Cell. Biochem. 2017 doi: 10.1007/s11010-016-2880-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Miron VV, et al. High-intensity intermittent exercise increases adenosine hydrolysis in platelets and lymphocytes and promotes platelet aggregation in futsal athletes. Platelets. 2019 doi: 10.1080/09537104.2018.1529299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ongini E, Monopoli A, Cacciari B, Giovanni Baraldi P. Selective adenosine A2A receptor antagonists. Farmaco. 2001 doi: 10.1016/S0014-827X(01)01024-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zocchi C, et al. The non-xanthine heterocyclic compound SCH 58261 is a new potent and selective A2a adenosine receptor antagonist. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 1996;276:398–404. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Shen HY, et al. A critical role of the adenosine A2A receptor in extrastriatal neurons in modulating psychomotor activity as revealed by opposite phenotypes of striatum and forebrain A2A receptor knock-outs. J. Neurosci. 2008 doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5255-07.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Shen HY, et al. Adenosine a2A receptors in striatal glutamatergic terminals and GABAergic neurons oppositely modulate psychostimulant action and DARPP-32 phosphorylation. PLoS ONE. 2013 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0080902. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Chen JF, et al. A(2A) adenosine receptor deficiency attenuates brain injury induced by transient focal ischemia in mice. J. Neurosci. 1999 doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.19-21-09192.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Chen JF, et al. Neuroprotection by caffeine and A(2A) adenosine receptor inactivation in a model of Parkinson’s disease. J. Neurosci. 2001 doi: 10.1523/jneurosci.21-10-j0001.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Aguiar AS, et al. Mitochondrial IV complex and brain neurothrophic derived factor responses of mice brain cortex after downhill training. Neurosci. Lett. 2007 doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2007.08.058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Aguiar AS, et al. Exercise improves cognitive impairment and dopamine metabolism in MPTP-treated mice. Neurotox. Res. 2016;29:118–125. doi: 10.1007/s12640-015-9566-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Aguiar AS, Speck AE, Amaral IM, Canas PM, Cunha RA. The exercise sex gap and the impact of the estrous cycle on exercise performance in mice. Sci. Rep. 2018;8:1–8. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-17765-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Bastia E, et al. A crucial role for forebrain adenosine A2A receptors in amphetamine sensitization. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2005 doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1300630. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.El Yacoubi M, Ledent C, Parmentier M, Costentin J, Vaugeois JM. SCH 58261 and ZM 241385 differentially prevent the motor effects of CGS 21680 in mice: evidence for a functional ‘atypical’ adenosine A(2A) receptor. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2000 doi: 10.1016/S0014-2999(00)00399-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Yacoubi ME, et al. The stimulant effects of caffeine on locomotor behaviour in mice are mediated through its blockade of adenosine A 2A receptors. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2000 doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0703170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ayachi M, Niel R, Momken I, Billat VL, Mille-Hamard L. Validation of a ramp running protocol for determination of the true VO2max in mice. Front. Physiol. 2016 doi: 10.3389/fphys.2016.00372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Barbato JC, et al. Spectrum of aerobic endurance running performance in eleven inbred strains of rats. J. Appl. Physiol. 1998 doi: 10.1152/jappl.1998.85.2.530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Speck AE, Aguiar AS. Letter to the editor: mechanisms of sex differences in exercise capacity. Am. J. Physiol. Regul. Integr. Comp. Physiol. 2020 doi: 10.1152/AJPREGU.00187.2019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Caligioni CS. Assessing reproductive status/stages in mice. Curr. Protoc. Neurosci. 2009 doi: 10.1002/0471142301.nsa04is48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.McLean AC, Valenzuela N, Fai S, Bennett SAL. Performing vaginal lavage, crystal violet staining, and vaginal cytological evaluation for mouse estrous cycle staging identification. J. Vis. Exp. 2012 doi: 10.3791/4389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Loro E, et al. IL-15Rα is a determinant of muscle fuel utilization, and its loss protects against obesity. Am. J. Physiol. Regul. Integr. Comp. Physiol. 2015 doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00505.2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Odermatt TS, Dedual MA, Borsigova M, Wueest S, Konrad D. Adipocyte-specific gp130 signalling mediates exercise-induced weight reduction. Int. J. Obes. 2020 doi: 10.1038/s41366-019-0444-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.De Carvalho M, Marcelino E, De Mendonça A. Electrophysiological studies in healthy subjects involving caffeine. J. Alzheimer’s Dis. 2010 doi: 10.3233/JAD-2010-1377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Walton C, Kalmar J, Cafarelli E. Caffeine increases spinal excitability in humans. Muscle Nerve. 2003 doi: 10.1002/mus.10457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Zheng X, Takatsu S, Wang H, Hasegawa H. Acute intraperitoneal injection of caffeine improves endurance exercise performance in association with increasing brain dopamine release during exercise. Pharmacol. Biochem. Behav. 2014 doi: 10.1016/j.pbb.2014.03.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Neyroud D, et al. Toxic doses of caffeine are needed to increase skeletal muscle contractility. Am. J. Physiol. Cell Physiol. 2019 doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00269.2018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Tallis J, James RS, Cox VM, Duncan MJ. Is the ergogenicity of caffeine affected by increasing age? The direct effect of a physiological concentration of caffeine on the power output of maximally stimulated edl and diaphragm muscle isolated from the mouse. J. Nutr. Heal. Aging. 2017 doi: 10.1007/s12603-016-0832-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Tallis J, James RS, Cox VM, Duncan MJ. The effect of physiological concentrations of caffeine on the power output of maximally and submaximally stimulated mouse EDL (fast) and soleus (slow) muscle. J. Appl. Physiol. 2012 doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00801.2011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Tallis J, Higgins MF, Cox VM, Duncan MJ, James RS. Does a physiological concentration of taurine increase acute muscle power output, time to fatigue, and recovery in isolated mouse soleus (slow) muscle with or without the presence of caffeine? Can. J. Physiol. Pharmacol. 2014 doi: 10.1139/cjpp-2013-0195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Tallis J, James RS, Cox VM, Duncan MJ. The effect of a physiological concentration of caffeine on the endurance of maximally and submaximally stimulated mouse soleus muscle. J. Physiol. Sci. 2013 doi: 10.1007/s12576-012-0247-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Domenici MR, et al. Behavioral and electrophysiological effects of the adenosine A2A receptor antagonist SCH 58261 in R6/2 Huntington’s disease mice. Neurobiol. Dis. 2007 doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2007.07.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Caetano L, et al. Adenosine A 2A receptor regulation of microglia morphological remodeling-gender bias in physiology and in a model of chronic anxiety. Mol. Psychiatry. 2017 doi: 10.1038/mp.2016.173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Scattoni ML, et al. Adenosine A2A receptor blockade before striatal excitotoxic lesions prevents long term behavioural disturbances in the quinolinic rat model of Huntington’s disease. Behav. Brain Res. 2007 doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2006.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Ferré S, Díaz-Ríos M, Salamone JD, Prediger RD. New Developments on the adenosine mechanisms of the central effects of caffeine and their implications for neuropsychiatric disorders. J. Caffeine Adenosine Res. 2018 doi: 10.1089/caff.2018.0017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Canas PM, et al. Neuronal adenosine A2A receptors are critical mediators of neurodegeneration triggered by convulsions. eNeuro. 2018 doi: 10.1523/ENEURO.0385-18.2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.O’Connor PJ, Motl RW, Broglio SP, Ely MR. Dose-dependent effect of caffeine on reducing leg muscle pain during cycling exercise is unrelated to systolic blood pressure. Pain. 2004 doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2004.01.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Duncan MJ, Dobell AP, Caygill CL, Eyre E, Tallis J. The effect of acute caffeine ingestion on upper body anaerobic exercise and cognitive performance. Eur. J. Sport Sci. 2019 doi: 10.1080/17461391.2018.1508505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Motl RW, O’Connor PJ, Dishman RK. Effect of caffeine on perceptions of leg muscle pain during moderate intensity cycling exercise. J. Pain. 2003 doi: 10.1016/S1526-5900(03)00635-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Maridakis V, O’Connor PJ, Dudley GA, McCully KK. Caffeine attenuates delayed-onset muscle pain and force loss following eccentric exercise. J. Pain. 2007 doi: 10.1016/j.jpain.2006.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Kalmar JM, Cafarelli E. Central fatigue and transcranial magnetic stimulation: effect of caffeine and the confound of peripheral transmission failure. J. Neurosci. Methods. 2004 doi: 10.1016/j.jneumeth.2004.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Shabir A, Hooton A, Tallis J, Higgins MF. The influence of caffeine expectancies on sport, exercise, and cognitive performance. Nutrients. 2018 doi: 10.3390/nu10101528. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Franco-Alvarenga PE, et al. Caffeine improved cycling trial performance in mentally fatigued cyclists, regardless of alterations in prefrontal cortex activation. Physiol. Behav. 2019 doi: 10.1016/j.physbeh.2019.02.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Kumar N, Wheaton LA, Snow TK, Millard-Stafford M. Exercise and caffeine improve sustained attention following fatigue independent of fitness status. Fatigue Biomed. Heal. Behav. 2015 doi: 10.1080/21641846.2015.1027553. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Hogervorst E, et al. Caffeine improves physical and cognitive performance during exhaustive exercise. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 2008 doi: 10.1249/MSS.0b013e31817bb8b7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Hogervorst E, Riedel WJ, Kovacs E, Brouns F, Jolles J. Caffeine improves cognitive performance after strenuous physical exercise. Int. J. Sports Med. 1999 doi: 10.1055/s-2007-971144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Azevedo R, Silva-Cavalcante MD, Gualano B, Lima-Silva AE, Bertuzzi R. Effects of caffeine ingestion on endurance performance in mentally fatigued individuals. Eur. J. Appl. Physiol. 2016 doi: 10.1007/s00421-016-3483-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Alves AC, et al. Role of adenosine A2A receptors in the central fatigue of neurodegenerative diseases. J. Caffeine Adenosine Res. 2019;9:145–156. doi: 10.1089/caff.2019.0009. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Matuszek M, Ga̧gało IT. The effect of N6-cyclohexyladenosine and 5′’-N-ethylcarboxamidoadenosine on body temperature in normothermic rabbits. Gen. Pharmacol. Vasc. Syst. 1996 doi: 10.1016/0306-3623(95)00098-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Nishijima Y, et al. Influence of caffeine ingestion on autonomic nervous activity during endurance exercise in humans. Eur. J. Appl. Physiol. 2002 doi: 10.1007/s00421-002-0678-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Bangsbo J, Jacobsen K, Nordberg N, Christensen NJ, Graham T. Acute and habitual caffeine ingestion and metabolic responses to steady-state exercise. J. Appl. Physiol. 1992 doi: 10.1152/jappl.1992.72.4.1297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Ryu S, et al. Caffeine as a lipolytic food component increases endurance performance in rats and athletes. J. Nutr. Sci. Vitaminol. (Tokyo). 2001 doi: 10.3177/jnsv.47.139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Boswell-Smith V, Spina D, Page CP. Phosphodiesterase inhibitors. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2006 doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0706495. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Yang JN, Chen JF, Fredholm BB. Physiological roles of A 1 and A 2A adenosine receptors in regulating heart rate, body temperature, and locomotion as revealed using knockout mice and caffeine. Am. J. Physiol. Hear. Circ. Physiol. 2009 doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00754.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Coupar IM, Tran BLT. Effects of adenosine agonists on consumptive behaviour and body temperature. J. Pharm. Pharmacol. 2002 doi: 10.1211/0022357021778330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Korkutata M, et al. Enhancing endogenous adenosine A2A receptor signaling induces slow-wave sleep without affecting body temperature and cardiovascular function. Neuropharmacology. 2019 doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2018.10.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated and analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.