Abstract

Purpose

Acute anterior uveitis (AAU) is a common intraocular inflammatory disease. AAU occurs in 30% to 50% of patients with ankylosing spondylitis (AS), and both conditions are strongly associated with human leukocyte antigen (HLA)-B27, implying a shared etiology. This study aims to apply genomewide association study (GWAS) to characterize the genetic associations of AAU and their relationship to the genetics of AS.

Methods

We undertook the GWAS analyses in 2752 patients with AS with AAU (cases) and 3836 patients with AS without AAU (controls). There were 7,436,415 single-nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) available after SNP microarray genotyping, imputation, and quality-control filtering.

Results

We identified one locus associated with AAU at genomewide significance: rs9378248 (P = 2.69 × 10−8, odds ratio [OR] = 0.78), lying close to HLA-B. Suggestive association was observed at 11 additional loci, including previously reported AS loci ERAP1 (rs27529, P = 2.19 × 10−7, OR = 1.22) and NOS2 (rs2274894, P = 8.22 × 10−7, OR = 0.83). Multiple novel suggestive associations were also identified, including MERTK (rs10171979, P = 2.56 × 10−6, OR = 1.20), KIFAP3 (rs508063, P = 5.64 × 10−7, OR = 1.20), CLCN7 (rs67412457, P = 1.33 × 10−6, OR = 1.25), ACAA2 (rs9947182, P = 9.70 × 10−7, OR = 1.37), and 5 intergenic loci. The SNP-based heritability is approximately 0.5 for AS alone, and is much higher (approximately 0.7) for AS with AAU. Consistent with the high heritability, a genomewide polygenic risk score shows strong power in identifying individuals at high risk of either AS with AAU or AS alone.

Conclusions

We report here the first GWAS for AAU and identify new susceptibility loci. Our findings confirm the strong overlap in etiopathogenesis of AAU with AS, and also provide new insights into the genetic basis of AAU.

Keywords: acute anterior uveitis, ankylosing spondylitis, GWAS, heritability, genetic risk scores

Uveitis is a major cause of ocular disease, leading to 5% to 10% of visual impairment worldwide.1 The prevalence varies depending on the ethnicity and geographic locations: 115 per 100,000 in America,2 40 per 100,000 in Japan,3 and 310 to 730 per 100,000 in Southern India.4 Acute anterior uveitis (AAU) is the most common type of uveitis and is characterized by inflammation of the anterior chamber.5 The typical clinical manifestations of AAU are that of abrupt onset of unilateral, often alternating, anterior uveitis, with significant cellular and protein extravasation into the anterior chamber and tendency for recurrences.6 AAU is frequently associated with spondyloarthropathies, such as ankylosing spondylitis (AS), psoriatic arthritis, and inflammatory bowel disease.7 Among those spondyloarthropathies, AS is the most common associated condition, present in 30% to 50% of patients with AAU. AAU is strongly associated with human leukocyte antigen (HLA)-B27.8 A large genetic study reported the prevalence of HLA-B27 was 81.8% in the group with ophthalmologist-diagnosed AAU and 92.0% in the group with self-reported AAU.9 Among patients with AAU who are HLA-B27 positive, the prevalence of concomitant AS rises to 80% to 84%.10

Multiple studies have demonstrated that genetic components play a major role in uveitis. Derhaag et al. found that the prevalence of AAU in HLA-B27-positive first-degree relatives of patients with AAU was 13%, significantly higher than the frequency of 1% in the HLA-B27-positive individuals without affected relatives, indicating high familiality.11 Several polymorphisms have been identified to be associated with the presence of AAU. To date, the strongest genetic association between a genetic component and AAU is attributable to HLA-B27, the major histocompatibility complex (MHC) type I allele. On the basis of genotyping using the Illumina Immunochip, a comparison between AAU and healthy control subjects found significant association over HLA-B, corresponding to the HLA-B27 tag single-nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) rs116488202.9 This study also found the association of three non-MHC loci, ERAP1, IL23R, and the intergenic region 2p15 with genomewide significance, and five loci reached a suggestive level of significance (IL10-IL19, IL18R1-IL1R1, IL6R, the chromosome 1q32 locus harboring KIF21B, and a retinal-related gene EYS).9 The authors also demonstrated significant differences in effect size of several previously discovered AS loci between AS+AAU+ and AS+AAU-, using two different models. In the first model (including the SNP and principal components), different effect sizes were observed in ERAP1, UBE2LE, ICOSLG, and EYS. In the second model (including the SNP, principal components, and HLA-B27 dose), different effect sizes were observed in ERAP1, ANTXR2, 21q22, and 2p15.9 Additionally, in an analysis comparing patients with AS with AAU versus controls, HLA-B27 and HLA-A*0201 were strongly associated with AAU using Illumina Exomechip microarray.12 Many candidate-gene association studies have reported nominal SNP associations in interleukin (IL) genes, tumor necrosis factor (TNF) genes, and complement factors correlated with anterior uveitis.13–15 However, those candidate-gene association studies were not adequately powered to reliably identify genes involved in AAU, nor did they control for potential population stratification effects, and, thus, their interpretation is unclear.

Genomewide association studies (GWAS) have proven to be a powerful and robust method to identify genetic associations with complex diseases over the past decade. For example, using GWAS, more than 100 AS susceptibility loci have been identified,16–20 which have been transformational in understanding the pathogenesis of AS,21,22 have changed disease management through repositioning of IL-17 inhibitors for management of the disease,23 and have stimulated several drug development programs.24 Although GWAS have been undertaken for nearly all major immune-mediated diseases, at this point, there have been no GWAS for AAU. This study aims to apply GWAS to characterize extensively the genetic associations of AAU and their relationship to the genetics of AS.

Methods

Sample Collection and Genotyping

AS case and control cohorts involved in this study are described in Supplementary Table S1. AS cases were defined by the modified New York criteria.25 Control participants were not specifically screened either for AS or AAU. All patients gave written informed consent, and ethics approval has been obtained from all relevant institutional ethics committees.

Genotyping and Quality Control

All the individuals of European descent have been previously genotyped using Illumina Infinium HumanCoreExome 24v1.1, according to the manufacturer's recommendations. Subsequently, bead intensity data were processed and normalized for each sample in Illumina GenomeStudio software. Data for successfully genotyped samples were extracted, and genotypes were called within collections using GenomeStudio. The human genome build 19 was used (UCSC).

The thresholds used in quality control include: a genotyping missingness rate of 0.05; an individual missingness rate of 0.05; a Hardy-Weinberg Equilibrium (HWE) threshold in controls of 1 × 10−6; a minor allele frequency (MAF) of 0.01; heterozygosity versus missingness outliers beyond three SDs were excluded; identity by descent (IBD) threshold of PI-HAT (proportion [IBD = 2] + 0.5 [IBD = 1]) 0.185 was used. Principal components analysis (PCA) was then computed using Genome-wide Complex Trait Analysis (GCTA) after the removal of regions of long-range linkage disequilibrium.26 Ancestry outliers were removed by using the top two components. A second round of PCA was then performed to better resolve ancestry differences within the cohorts. Principal components were used as covariates to control for population stratification.

Imputation

Genotyping data were imputed using Sanger imputation service (https://imputation.sanger.ac.uk/). Optional pre-phasing was with EAGLE227 and imputation with PBWT.28 The Haplotype Reference Consortium was used as the references panel. Imputed loci with quality score < 0.6 were excluded from the association testing. Detailed investigations of the MHC alleles and HLA loci were performed using SNP2HLA,29 which is an analysis package that performs HLA allele and amino acid imputation from SNP data and association analysis.

Association Analysis

Plink (https://www.cog-genomics.org/plink2)30 was used to perform association analyses with eigenvectors from PCA as covariates for population stratification control. Significance levels were defined as genomewide (P < 5 × 10−8) or suggestive when P > 5 × 10−8 but < 1 × 10−5. Previous reported loci were also examined. Subsequently, conditional analysis for secondary signal detection was performed in all susceptibility loci by fitting the primary SNP as a fixed effect. Manhattan plots and quantile to quantile (Q-Q) plots were displayed, and genomic inflation factor 1000 values were calculated. To identify the genetic basis of AAU, we designed the GWAS based on comparison of patients with AS with AAU (AS+AAU+) versus patients with AS without AAU (AS+AAU-). Locus zoom plotting was carried out using LocusZoom.31

Estimation of SNP-Based Heritability

We estimated the SNP-based heritability (SNP h2) by GCTA.26 Heritability is the proportion of the phenotypic variance accounted for by genetic effects. We investigated SNP-based heritability by designing three different comparisons: (1) patients with AS with AAU (AS+AAU+) versus patients with AS without AAU (AS+AAU-); (2) patients with AS without AAU (AS+AAU-) versus controls; and (3) patients with AS with AAU (AS+AAU+) versus controls. The estimation of heritability was performed for a range of disease prevalences.

Mendelian Randomization Analysis

To determine the most likely causal genes, we performed the summary data-based Mendelian randomization (SMR32) analysis for AAU with expression quantitative trait loci (eQTL) data. GWAS data consisted of patients with AS with AAU (AS+AAU+) and patients with AS without AAU (AS+AAU-), and the eQTL data was from the Consortium for the Architecture of Gene Expression (CAGE), which comprises individual-level whole-blood expression and genotype data on 2765 individuals.33 In the SMR analysis, only probes for which the P value of the top associated cis-eQTL was < 5 × 10−8 were included and the MHC region was excluded. To control the genomewide type I error rate, Bonferroni correction was used to account for multiple testing. Locus zoom plots of candidate loci were generated.

Genomewide Polygenic Risk Scores

Polygenic risk scores (PRS) were calculated for each individual using the adaptive MultiBLUP algorithm.34 Only genotyped SNPs in common between all SNP arrays where the missingness rate was <0.05, the MAF was >0.01, and the HWE P value was > 1 × 10−6 were used. A conservative approach was used whereby the cohort was divided into independent training and test sets, rather than using a cross-validation approach.35 The training set was then used to calculate the scoring matrix. This MultiBLUP algorithm first selected regions based on a P values’ threshold (option-sig1) obtained using the training cohort. Within these regions, all SNPs with a significance threshold greater than a second P value threshold (option-sig2) were considered by the algorithm, which then controls for the linkage disequilibrium structure. The P value thresholds were optimized by choosing a range of values between 1 × 10−7 and 1 × 10−3 for option-sig1 and 1 × 10−3 and 1 × 10−2 for option-sig2. Then the resulting weighted predictors were applied to the test cohort to obtain per sample scores from which the maximum area under the curve (AUC) was obtained.

Results

Comparison of Patients With AS With AAU versus AS Alone

To investigate the genetic basis of AAU while controlling for concomitant AS, we performed a GWAS comparing patients with AS with AAU (AS+AAU+) versus patients with AS without AAU (AS+AAU-). After individual quality control (QC) there were 2752 patients with AS and with AAU and 3836 patients with AS alone, respectively. Given our sample size, the study has > 80% power for risk alleles of MAF = 0.2, for heterozygote odds ratios (ORs) > 1.21 at a type 1 error rate of 5 × 10−8. After imputation and SNP QC, there were 7,436,415 SNPs (Supplementary Table S2). Subsequently, analysis of logistic regression with principal components as covariates against linear mixed models was conducted. The top four eigenvectors were controlled because additional eigenvectors did not reduce the genomic inflation factor. Quantile to quantile (Q-Q) plots are presented in Supplementary Figure S1. Genomic inflation factor (λ) calculated using 7,396,528 SNPs (MHC SNPs were excluded) was 1.008 (λ1000 for an equivalent study of 1000 cases and 1000 controls = 1.002), indicating minimal evidence of residual population stratification in the overall data set. Genomic inflation factors stratified by frequency, imputation quality score, and MHC are shown in Supplementary Table S3.

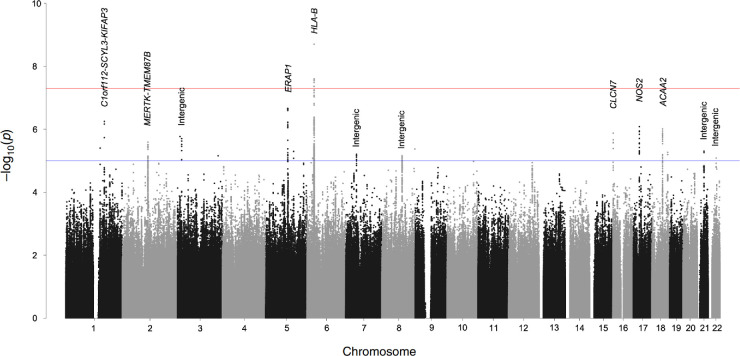

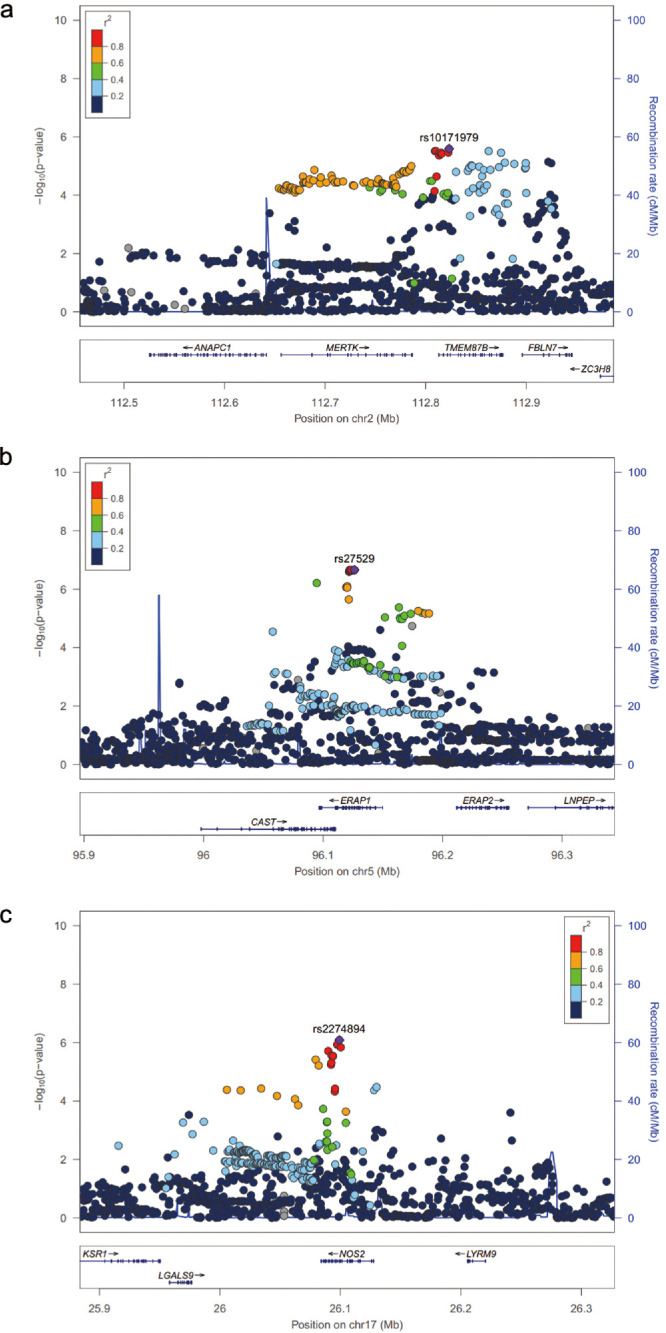

We identified one locus associated with AAU at genomewide significance: rs9378248 (P = 2.69 × 10−8, OR = 0.78), lying close to HLA-B, a known susceptibility gene for both AAU and AS (Table 1 and Fig. 1). Suggestive association was observed at 11 additional loci summarized in Table 1. We found suggestive association with SNPs in MERTK locus (rs10171979, P = 2.56 × 10−6, OR = 1.20), which is also a novel finding in our ongoing GWAS in AS (Table 1 and Fig. 2a). Association was also observed with SNPs at previously reported AS loci, including ERAP1 (rs27529, P = 2.19 × 10−7, OR = 1.22; Fig. 2b), and NOS2 (rs2274894, P = 8.22 × 10−7, OR = 0.83; Fig. 2c).

Table 1.

Results of the Association Analyses of Patients With AS with AAU versus patients with AS Without AAU

| SNP ID | Chr. | Position* | Nearby Genes | P Value | Effect Allele | OR | 95% CI | Associated With AS |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| rs9378248 | 6p21 | 31326289 | HLA-B | 2.69 × 10−8 | A | 0.78 | 0.71-0.85 | Yes |

| rs508063 | 1q24 | 169923676 | C1orf112-SCYL3-KIFAP3 | 5.64 × 10−7 | A | 1.20 | 1.12-1.28 | No |

| rs10171979 | 2q13 | 112823320 | MERTK-TMEM87B | 2.56 × 10−6 | C | 1.20 | 1.11-1.30 | Yes |

| rs76412624 | 3p24 | 18186605 | Intergenic | 1.98 × 10−6 | G | 0.67 | 0.57-0.79 | No |

| rs27529 | 5q15 | 96126308 | ERAP1 | 2.19 × 10−7 | A | 1.22 | 1.13-1.31 | Yes |

| rs7784778 | 7p12 | 46951833 | Intergenic | 6.22 × 10−6 | T | 0.84 | 0.78-0.91 | No |

| rs10093384 | 8q21 | 88635942 | Intergenic | 7.01 × 10−6 | A | 1.20 | 1.11-1.31 | No |

| rs67412457 | 16p13 | 1525710 | CLCN7 | 1.33 × 10−6 | A | 1.25 | 1.14-1.36 | No |

| rs2274894 | 17q11 | 26099171 | NOS2 | 8.22 × 10−7 | T | 0.83 | 0.78-0.90 | Yes |

| rs9947182 | 18q21 | 47253904 | ACAA2 | 9.70 × 10−7 | T | 1.37 | 1.21-1.55 | No |

| rs7281081 | 21q21 | 29471489 | Intergenic | 4.98 × 10−6 | T | 0.79 | 0.71-0.87 | No |

| rs1580226 | 22q12 | 34809453 | Intergenic | 8.26 × 10−6 | T | 0.82 | 0.75-0.89 | No |

Chr., chromosome; OR, odds ratio; 95% CI, 95% confidence interval.

UCSC, human genome build 19.

Figure 1.

Manhattan plot of association analyses of patients with AS with AAU versus patients with AS without AAU. Y axis represents the P values on the -log10 scale. The red line represents P = 5 × 10−8 (genomewide significance), and the blue dashed line represents P = 1 × 10−5 (suggestive association).

Figure 2.

Locus zoom plot of association results for MERTK-TMEM87B locus (a), ERAP1 locus (b), and NOS2 locus (c). The reference population for LD data is 1000 Genomes EUR. SNPs with missing LD information are shown in grey.

In addition to these discoveries, association was seen at loci not previously known to be associated with AAU or AS, including KIFAP3 (rs508063, P = 5.64 × 10−7, OR = 1.20), CLCN7 (rs67412457, P = 1.33 × 10−6, OR = 1.25), ACAA2 (rs9947182, P = 9.70 × 10−7, OR = 1.37), and five intergenic loci at 3p24 (rs76412624, P = 1.98 × 10−6, OR = 0.67), 7p12 (rs7784778, P = 6.22 × 10−6, OR = 0.84), 8q21 (rs10093384, P = 7.01 × 10−6, OR = 1.20), 21q21 (rs7281081, P = 4.98 × 10−6, OR = 0.79), and 22q12 (rs1580226, P = 8.26 × 10−6, OR = 0.82). Subsequently, conditional analysis for secondary signal detection was performed in all the 11 non-MHC loci by fitting the primary SNP as a fixed effect. After conditioning on these SNPs, no residual association was seen in these loci (P < 1 × 10−4), indicating no evidence in the current study for any secondary signal at these loci.

Investigation of Reported AS Genes in AAU GWAS

To investigate further potential overlaps and differences between genetic associations of AAU and AS, we examined the associations between the causal genes of AS and AAU. AS genetic associations that either achieved genomewide significance in individual studies or as part of a cross-disease study of pleiotropic genes were included.24 If the reference SNP had been genotyped or imputed in the current study, the OR was compared directly. Where this was not the case, tagSNPs were identified, linkage disequilibrium with the reference SNP determined using LDlink (ldlink.nci.nih.gov), then ODs were compared taking into account the directionality of the linkage disequilibrium. In addition to HLA-B, ERAP1, NOS2, and MERTK (Table 1), moderate association was observed with SNPs in additional known AS genes at IL23R, ASAP2, CMC1, IL12B, ZC3H12C, IL10, SP140, and PTPN2 (Supplementary Table S4). Furthermore, most of them showed the consistent direction of effect with the discoveries in AS GWAS (Supplementary Table S4, Supplementary Fig. S2). For example, rs11209032 in IL23R reported in AS GWAS with OR = 1.20,18 and this study showed OR = 1.14, with concordant direction of effect. In the ASAP2 locus, rs2666218 was observed in AS with OR = 1.12, and was associated with AAU with OR = 1.13. Moreover, the top SNP in our AAU analyses, rs56111045, was in very strong linkage disequilibrium with it (D’ = 1; R2 = 0.995). These results indicate a consistent direction of effect of ASAP2 locus in AS and AAU.

HLA Imputation and Association Analysis

To better understand the genetic basis of the MHC susceptibility loci, we performed HLA imputation using SNP2HLA.29 After removing subjects with poor HLA imputation quality, 2725 patients with AS with AAU (AS+AAU+) and 3796 patients with AS without AAU (AS+AAU-) remained and were included in the analysis of MHC susceptibility. In total, 424 HLA alleles (including alleles at either two-digit or four-digit resolution) and 1276 amino acid residues were imputed. For the HLA alleles, as expected, HLA-B*27 (P = 1.86 × 10−42, OR = 2.35) was the most significantly associated allele with AAU (Table 2). The question of whether HLA-B*27 exerts its influence through a dominant or additive genetic model was assessed. Results showed that homozygosity for HLA-B*27 confers OR of 3.3 (95% confidence interval [CI] = 2.45–4.45), and heterozygosity for HLA-B*27 confers OR of 2.93 (95% CI = 2.53–3.4). This finding is consistent with previous studies of AS GWAS,36,37 suggesting that HLA-B*27 homozygosity increases risk over heterozygosity. In addition to HLA-B*27 alleles, genomewide significant association was also observed in unconditioned analyses with HLA-C*02 allele (Table 2), which was also reported in AS genetics.38 Nominal associations were also seen between AAU and previously AS-associated allele HLA-DRB1*0103,38 which is also known to be associated with inflammatory bowel disease.39,40 To detect whether other HLA alleles affect AAU susceptibility independently from the HLA-B*27, additional conditional analyses were performed. After adjusting for the HLA-B*27 allele, the next most-associated HLA allele was HLA-DRB1*15 (P = 8.14 × 10−5, OR = 1.28). After conditioning on both HLA-B*27 and HLA-DRB1*15, lead association was seen with HLA-DPB1*03 (P = 4.83 × 10−3, OR = 1.17).

Table 2.

Association Analysis of HLA Alleles in the Comparison of Patients with AS with AAU versus Patients with AS without AAU

| HLA Allele# | Position* | OR | 95% CI | P Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| HLA-B*27 | 31431272 | 2.35 | 2.08-2.66 | 1.86 × 10−42 |

| HLA-B*2705 | 31431272 | 2.27 | 2.02-2.56 | 1.49 × 10−41 |

| HLA-C*02 | 31346171 | 1.33 | 1.21-1.45 | 3.37 × 10−9 |

| HLA-C*0202 | 31346171 | 1.33 | 1.21-1.45 | 3.37 × 10−9 |

| HLA-C*01 | 31346171 | 1.25 | 1.14-1.38 | 4.26 × 10−6 |

| HLA-C*0102 | 31346171 | 1.25 | 1.14-1.38 | 4.26 × 10−6 |

| HLA-DRB1*0103 | 32660042 | 1.34 | 1.14-1.57 | 0.00044 |

| HLA-DRB1*1501 | 32660042 | 1.23 | 1.09-1.39 | 0.00074 |

| HLA-C*0701 | 31346171 | 0.82 | 0.72-0.92 | 0.00078 |

| HLA-B*4402 | 31431272 | 0.79 | 0.68-0.91 | 0.0011 |

| HLA-C*05 | 31346171 | 0.80 | 0.70-0.91 | 0.0011 |

| HLA-C*0501 | 31346171 | 0.80 | 0.70-0.91 | 0.0011 |

| HLA-DQB1*0602 | 32739039 | 1.22 | 1.08-1.38 | 0.0018 |

| HLA-DRB1*15 | 32660042 | 1.21 | 1.07-1.37 | 0.0018 |

| HLA-B*08 | 31431272 | 0.81 | 0.71-0.93 | 0.0023 |

| HLA-B*0801 | 31431272 | 0.81 | 0.71-0.93 | 0.0023 |

| HLA-B*44 | 31431272 | 0.84 | 0.75-0.95 | 0.0051 |

| Adjusting for the HLA-B*27 allele | ||||

| HLA-DRB1*15 | 32660042 | 1.28 | 1.13-1.45 | 8.14 × 10−5 |

| HLA-B*07 | 31431272 | 1.30 | 1.13-1.50 | 0.00023 |

| HLA-DPB1*03 | 33157346 | 1.16 | 1.04-1.29 | 0.0088 |

| Adjusting for both HLA-B*27 and HLA-DRB1*15 allele | ||||

| HLA-DPB1*03 | 33157346 | 1.17 | 1.05-1.31 | 0.0048 |

OR, odds ratio; 95% CI, 95% confidence interval.

UCSC, human genome build 19.

HLA allele is imputed using SNP2HLA.

Considering amino acid residues, the most significant association was observed for amino acid position 97 in HLA-B (P = 6.09 × 10−43, OR = 2.36), which was also the strongest signal seen in AS study (Supplementary Table S5).38 Strong associations were also observed with the amino acid positions 70, 114, 77, 69, and 67 of HLA-B but all these signals lost significance (P > 1 × 10−5) conditioning on amino acid position 97 (Supplementary Table S5, Supplementary Table S6). After adjusting for the amino acid position 97, the most strongly associated signals were amino acid position 67 and 70 in HLA-B (P = 3.80 × 10−5, OR = 1.31; P = 4.42 × 10−5, OR = 1.31) and amino acid position 71 in HLA-DRB1 (P = 8.51 × 10−5, OR = 1.28; Supplementary Table S6).

Interactions Between ERAP1 and HLA-B27

Previous studies have observed that the association with the nonsynonymous SNP rs30187 (p.Lys528Arg) in the ERAP1 locus is restricted to HLA-B*27-positive or HLA-B*40-positive HLA-B27-negative patients with AS.36,38 To assess the gene-gene interactions between ERAP1 and HLA-B27 in AAU, we investigated the associations by conducting two different comparisons. In the comparison between HLA-B*27-positive AS+AAU+ subjects and all AS+AAU- subjects, we observed significant association with rs30187 in ERAP1 (P = 1.4 × 10−8, OR = 1.25). However, when we compared the HLA-B*27-negative AS+AAU+ subjects with all AS+AAU- subjects (n = 3796) or patients with HLA-B27-negative AS+AAU- (n = 927), we saw no association with rs30187 (P > 0.05). These observations further support the existence of an interaction between ERAP1 and HLA-B27. The study did not have sufficient power to test the interaction between HLA-B40 and ERAP1 variants so this was not performed.

eQTL Mendelian Randomization Analysis

To determine the most likely causal genes at associated loci, we performed the SMR32 analysis for AAU with eQTL data. GWAS data consisted of 2752 patients with AS with AAU (AS+AAU+) and 3836 patients with AS without AAU (AS+AAU-), and the eQTL data was from the CAGE, which comprises individual-level whole-blood expression and genotype data on 2765 individuals.33 In the SMR analysis, only probes for which the P value of the top associated cis-eQTL was < 5 × 10−8 were included and the MHC region was excluded. To control the genomewide type I error rate, Bonferroni correction was used to account for multiple testing, which resulted in a genomewide significance level of P = 5.95 × 10−6 (= 0.05/8403).

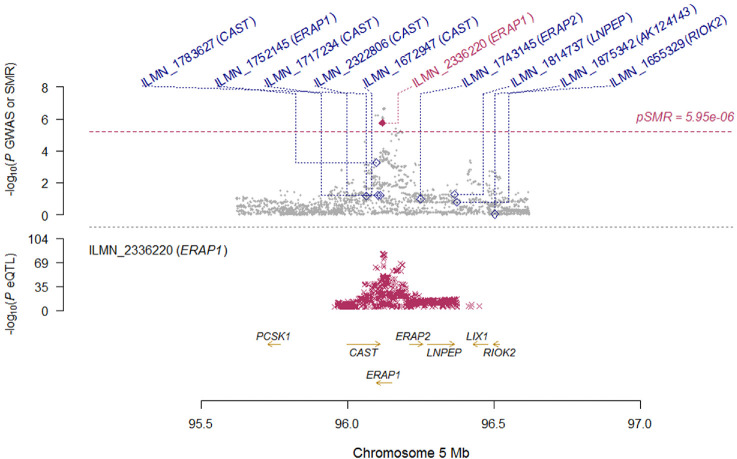

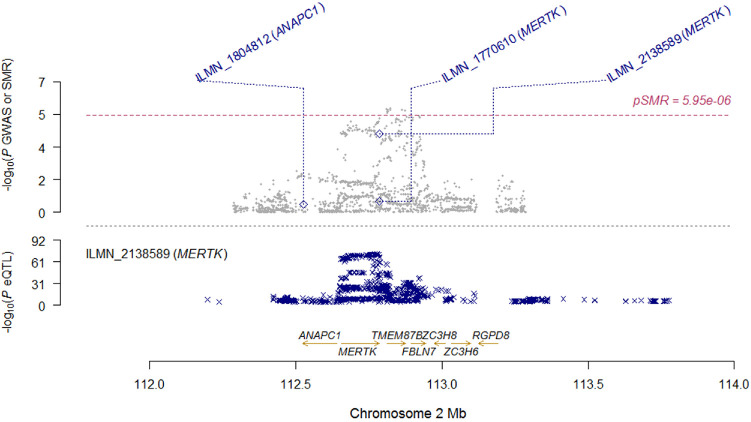

Results of top signals are summarized in Table 3. Notably, the most significant signal was ERAP1 (PGWAS = 7.91 × 10−7, PeQTL = 4.71 × 10−83, PSMR = 1.75 × 10−6), which reached genomewide significance (Table 3 and Fig. 3). In addition to ERAP1, the most associated gene was MERTK (PGWAS = 3.95 × 10−5, PeQTL = 4.02 × 10−73, PSMR = 6.25 × 10−5) which was very close to genomewide significance (Table 3 and Fig. 4). These findings indicate that ERAP1 and MERTK are the most functionally relevant genes in these two loci.

Table 3.

Results of Summary Data-Based Mendelian Randomization Analysis for AAU with eQTL Data

| GWAS | eQTL | SMR | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Probe ID | Chr. | Nearby Genes | Probe Position* | Top SNP | SNP Position* | Effect Allele | Effect Size | P Value | Effect Size | P Value | Effect Size | P Value |

| ILMN_2336220 | 5 | ERAP1 | 96118859 | rs39841 | 96120170 | G | 0.193 | 7.91 × 10−7 | 0.593 | 4.71 × 10−83 | 0.325 | 1.75 × 10−6 |

| ILMN_2138589 | 2 | MERTK | 112786554 | rs78116208 | 112769801 | T | 0.169 | 3.95 × 10−5 | −0.558 | 4.02 × 10−73 | −0.304 | 6.25 × 10−5 |

| ILMN_1723116 | 16 | AMFR | 56395803 | rs11644357 | 56445252 | G | −0.138 | 1.09 × 10−4 | −0.920 | 2.71 × 10−275 | 0.150 | 1.19 × 10−4 |

| ILMN_1664912 | 9 | IL11RA | 34661803 | rs2070074 | 34649442 | G | 0.203 | 4.28 × 10−4 | 1.290 | 9.16 × 10−144 | 0.157 | 4.95 × 10−4 |

| ILMN_1769550 | 17 | SLFN5 | 33593671 | rs12602385 | 33563756 | T | 0.129 | 4.02 × 10−4 | 0.464 | 4.90 × 10−61 | 0.278 | 5.29 × 10−4 |

| ILMN_1752145 | 5 | ERAP1 | 96098078 | rs1057569 | 96109610 | A | −0.150 | 4.29 × 10−4 | 0.562 | 3.88 × 10−75 | −0.267 | 5.43 × 10−4 |

| ILMN_1657475 | 9 | GALT | 34650419 | rs2070074 | 34649442 | G | 0.203 | 4.28 × 10−4 | −0.827 | 4.79 × 10−63 | −0.246 | 5.79 × 10−4 |

| ILMN_1774761 | 3 | CCR2 | 46401979 | rs2172247 | 46214670 | T | 0.131 | 3.06 × 10−4 | −0.254 | 4.88 × 10−20 | −0.518 | 8.03 × 10−4 |

| ILMN_1720024 | 9 | IL11RA | 34660552 | rs2070074 | 34649442 | G | 0.203 | 4.28 × 10−4 | 0.522 | 4.85 × 10−26 | 0.389 | 8.50 × 10−4 |

Chr., chromosome; GWAS, genomewide association study; eQTL, expression quantitative trait loci; SMR, summary data-based Mendelian randomization.

UCSC, human genome build 19.

Figure 3.

Locus zoom plot of SMR analysis for ERAP1 locus. Top plot, grey dots represent the P values for SNPs from the comparison between AS+AAU+ and AS+AAU-, diamonds represent the P values for probes from the SMR test. Bottom plot, the eQTL P values of SNPs from the CAGE study for the ILMN_2336220 probe tagging ERAP1.

Figure 4.

Locus zoom plot of SMR analysis for MERTK locus. Top plot, grey dots represent the P values for SNPs from the comparison between AS+AAU+ and AS+AAU-, diamonds represent the P values for probes from the SMR test. Bottom plot, the eQTL P values of SNPs from the CAGE study for the ILMN_2138589 probe tagging MERTK.

Estimation of SNP-Based Heritability

Heritability is the proportion of the phenotypic variance accounted for by genetic effects. We investigated SNP-based heritability by designing three different comparisons: (1) patients with AS with AAU versus AS alone; (2) patients with AS alone versus controls; and (3) patients with AS with AAU versus controls. The details are summarized in Table 4. The estimation of heritability was 0.40 to 0.43 in the comparison between patients with AS with AAU and patients with AS without AAU, adjusting prevalence from 0.3 to 0.5. Interestingly, in the comparison between AS alone and controls, the estimated heritability was 0.48 to 0.60, adjusting prevalence from 0.002 to 0.006. When we compared the patients with AS and with AAU to controls, the estimated heritability was 0.59 to 0.72, adjusting prevalence from 0.001 to 0.003. These discoveries not only confirmed that AS and AAU are highly heritably disorders, but also suggest that there are additional genetic contributors to AAU compared with AS alone.

Table 4.

Estimation of Heritability in Three Comparisons

| Cases (Number) | Controls (Number) | Heritability* (SE; Adjusted Prevalence) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| AS+AAU+ (2752) | AS+AAU− (3836) | 0.40 (0.071; 0.3) | 0.42 (0.075; 0.4) | 0.43 (0.077; 0.5) |

| AS+AAU− (3836) | Controls (14542) | 0.48 (0.008; 0.002) | 0.55 (0.010; 0.004) | 0.60 (0.010; 0.006) |

| AS+AAU+ (2752) | Controls (14542) | 0.59 (0.009; 0.001) | 0.67 (0.010; 0.002) | 0.72 (0.011; 0.003) |

Heritability is calculated using GCTA (https://cnsgenomics.com/software/gcta/#Download).

Genetic Risk Prediction

The greater heritability of AS+AAU+ compared with AS alone or AS+AAU- suggests that PRS have the potential to identify AAU cases likely to develop AS, and conversely AS cases likely to develop AAU. To assess the discriminatory capacity and accuracy in risk prediction, we first performed the analyses of PRS by using two different designs (1) AS+AAU+ versus AS+AAU-; and (2) AS+AAU+ versus controls. In the first comparison, AS+AAU+ versus AS+AAU-, the overall discriminatory capacity of PRS was weak (AUC = 0.56; 95% CI = 0.54–0.58; P value = 2.10 × 10−10). Assuming the prevalence of patients with AS with AAU is 40% among the AS population, those patients with AS in the top 50% of genetic risk had an estimated genetic risk of developing AAU of 43.3% (SD = 0.9%; Supplementary Fig. S3). Those in the bottom 50% had < 37% chance of developing the disease. Thus, in the setting of a patient with AS, PRS alone are currently not helpful in distinguishing those patients likely to develop AAU.

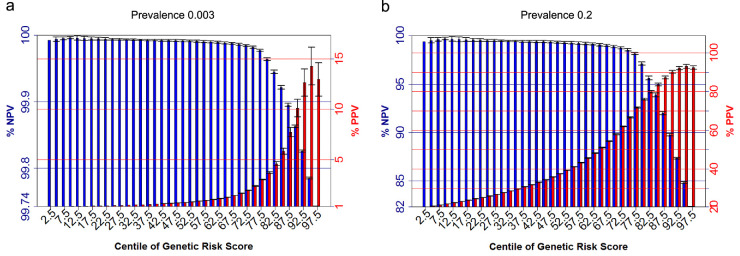

In the second comparison, AS+AAU+ versus controls, we observed the overall discriminatory capacity of genomewide PRS was very strong (AUC = 0.96; 95% CI = 0.955–0.966). When computing PRS using HLA-B27 alone, the AUC is 0.92 (95% CI = 0.915–0.927). Considering a general population setting, assuming the prevalence of patients with AS with AAU is 0.3% among the population, those in the top 10% of genetic risk had an estimated genetic risk of developing AS with AAU of 10.1% (SD = 0.9%; Fig. 5a), 2.9 times higher than the risk using HLA-B27 alone (3.5% [SD = 0.1%], Supplementary Fig. S4a). Those in the top 5% had a risk of developing AS with AAU of 14.3% (SD = 1.9%; Fig. 5a), 3.6 × higher than the risk estimate using HLA-B27 alone (4% [SD = 0.4%]). Those in the bottom 85% had < 0.1% chance of developing the disease, similar to the estimate using HLA-B27 alone. Considering a clinical setting where patients with AAU are being assessed for their risk of AS, assuming the prevalence of patients with AS with AAU is 20% in outpatient clinics, we observed the estimated genetic risk of developing disease of 90.3% (SD = 0.8%) for those in the top 10% and 93.2% (SD = 1.0%) for those in the top 5% (Fig. 5b). Using HLA-B27 alone, the estimated genetic risk of developing disease of 75.2% (SD = 0.9%) for those in the top 10% and 77.3% (SD = 1.9%). Considering negative predictive values, using the PRS the bottom 65% of patients would have < 1% chance of also having AS. The performance using a score for HLA-B27 alone is marginally worse, with the maximum negative predictive value (NPV) being 98%, 75% of the distribution (Supplementary Fig. S4b). These results indicate that genomewide PRS has better performance than HLA-B27 alone, particularly in positive predictive value (PPV) analyses.

Figure 5.

Positive and negative predictive values for patients with AS with AAU for centiles of genetic risk scores. The assumed prevalence of patients with AS with AAU of 0.3% among the population (a), and assumed prevalence of 20% in outpatient clinics (b). Error Bars denote 2 standard deviations based on 10-fold cross validation.

Discussion

This study has expanded understanding of the genetics of AAU, through the discovery of novel suggestive associated loci including MERTK, CLCN7, ACAA2, KIFAP3, and five intergenic loci. Among those new loci, MERTK locus is also a novel finding in our ongoing GWAS in AS. Interestingly, Mendelian randomization analysis for AAU with eQTL data showed that MERTK is the most functionally relevant gene in the locus.

MERTK is a member of the TYRO3/AXL/MER (TAM) receptor kinase family and encodes a transmembrane protein, which has fibronectin type-III domains, two immunoglobulin-like (Ig-like) C2-type domains, and one tyrosine kinase domain.41 The three TAM receptors interact functionally with one another in their pleiotropic roles in immune regulation, including in autoimmune and infectious diseases, and cancer.42 MERTK was not previously known to be associated with AS or AAU, whereas mutations in MERTK gene lead to an inherited retinal disorder, named retinitis pigmentosa.41 Notably, mutations in previously reported AAU-related gene EYS also lead to retinitis pigmentosa.9,43 In addition to retinitis pigmentosa, genetic associations of MERTK have also been reported in a few other traits. SNP associations with SNPs in linkage disequilibrium with the strongest associated SNP in AAU have previously been reported in multiple sclerosis and systolic blood pressure (r2 > 0.5, both concordant in direction), and with other SNPs not in linkage disequilibrium (r2 < 0.3) with rs10171979, including hepatitis C induced liver fibrosis, coronary artery disease, heel bone mineral density, and white blood cell count (https://www.ebi.ac.uk/gwas/genes/MERTK). Axl/Mertk double knockout mice are susceptible to T-cell mediated uveitis,44 and Tyro3/Axl/Mertk triple knockout mice develop bone marrow edema and macrophage and B-cell and T-cell infiltration, consistent with changes seen in spondyloarthritidies.45 MERTK is expressed at high levels in the ovaries, prostate, testis, lungs, retinas, and kidneys, and at lower levels in the heart, brain, and skeletal muscle.46 MERTK is also expressed in macrophages, dendritic cells, natural killer (NK) cells, NKT cells, and platelets.46–48 MERTK is not expressed on the normal lymphocytes but has been found to be expressed in a majority of lymphoblasts from patients with T-cell leukemia, certain subsets of B-cell leukemia, and mantle cell lymphoma.49,50 Additionally, MERTK signaling plays a role in various processes, such as macrophage clearance of apoptotic cells, platelet aggregation, cytoskeleton reorganization, and engulfment. Animal models that lack functional MERTK protein have macrophages that are unable to appropriately engulf apoptotic cells. This inefficient clearance of dead cells can lead to activation of inflammation and development of autoimmunity.51 Moreover, MERTK was also reported as a potent suppressor of T cell response.52 Taken together, these discoveries indicate the potential role of MERTK in the etiology of AAU. However, the functional relevance in this study was based on gene expression and did not include other functions. Future functional studies are necessary to further understand the biological mechanisms underpinning the association of MERTK with AAU.

This study also confirmed multiple discoveries from previous genetics of AS/AAU. We confirmed the association of previously reported loci associated with AAU from a large genetic study on the basis of immunochip genotyping, including HLA-B, ERAP1, IL23R, and IL10.9 We also confirmed the association of previously reported genetic loci associated with AS but not yet with AAU, including NOS2, ASAP2, CMC1, IL12B, ZC3H12C, SP140, and PTPN2. Furthermore, consistent with previous studies on MHC loci of AS/AAU, HLA imputation of this study showed that HLA-B*27 was the most significantly associated allele with AAU (Supplementary Fig. S5a), and we also observed HLA-B*27 homozygosity increases risk over heterozygosity. We also confirmed the existence of an interaction between ERAP1 and HLA-B*27 for AAU, which was initially discovered in a GWAS of AS. Minor additional risk association was seen with HLA-DRB1*15 (Supplementary Fig. S5b), consistent with previous reports using direct genotyping,53 and with HLA-DPB1*03 (Supplementary Fig. S5c), independent of HLA-B27, suggesting the presence of additional MHC encoded factors influencing AAU risk in patients with AS.

We have estimated SNP-based heritability in different comparisons, and found both patients with AS alone and patients with AS and with AAU showed high heritability. The estimations of heritability based on genotyped SNPs reached approximately 0.7, which is very close to the result from twin studies for AS alone (heritability > 0.9).54,55 Moreover, the AS+AAU+ cohort showed higher heritability than the AS+AAU- cohort, indicating that AAU cases carry additional genetic risk compared with cases with isolated AS. This supports further initiatives to identify AAU genetic susceptibility factors.

To assess the discriminatory capacity and accuracy in risk prediction using genomewide PRS, we first applied PRS on subjects with AS+AAU+ versus subjects with AS alone. But the overall discriminatory capacity of this PRS (AUC = 0.56) was too low to be of clinical utility. Subsequently, we applied PRS on subjects with AS+AAU+ versus controls. Interestingly, we observed the discriminatory capacity of PRS was very strong with AUC of 0.96, and higher than the discriminatory capacity of HLA-B27 alone (AUC = 0.92). The difference in performance of the PRS and HLA-B27 alone is more apparent when PPV and NPVs are considered. As HLA-B27 is only carried in approximately 8% of European-descent populations, it can only demonstrate increased risk in that small group, and provides no information about the relative risk of the disease across the remaining 92% of the population. In contrast, not only does the PRS provide higher PPVs even among HLA-B27 positive individuals, it also is informative about differences in AAU risk across HLA-B27 negative individuals. PRS also performed significantly better in excluding AS among patients with AAU than did HLA-B27 alone. These results suggest that PRS has significant potential clinical benefit in predicting the likelihood of developing AS with AAU, although it had limited capacity in risk prediction of the patients with AS developing AAU.

The prevalence of AAU increases almost linearly with increasing disease duration, with over 50% of patients with AS with > 40 years of disease duration having experienced AAU.9 Thus, it is likely that many patients classified in the current study as not being AAU affected will ultimately likely develop the complication. This reduces the power to detect genetic associations, to identify heritability, and to develop PRS. A further complication is the need to use study designs controlling for fact that these patients have an additional highly heritable disease, AS. The study design, therefore, is only able to distinguish factors that influence the risk of AAU over and above their effect on the risk of AS. Thus genetic effects on risk of AAU that are shared at similar strengths with AS will not be detected by this study design. Such associations could potentially be identified in studies comparing AAU cases not affected by AS with controls. However, the high prevalence of AS among AAU cases, and the high frequency of subclinical sacroiliitis in these patients, would mean that careful screening of cases would be required, and that cases would need to be old enough that AS would be unlikely to develop in the future if it had not already manifested. We also acknowledge the limitation of our study of lack of independent replication to test the observed associations across multiple cohorts. Future studies should consider our GWAS findings in different populations.

In conclusion, we report here the first GWAS for AAU and identified new susceptibility loci. The findings of association with the HLA-B, ERAP1, NOS2, and IL23R loci are consistent with a strong overlap in etiopathogenesis with AS. We identified new suggestive associated loci of AAU, including MERTK, which was reported to be involved in the development of autoimmunity, indicating the potential role of MERTK in the etiology of AAU. Further research is needed into the immunopathogenic mechanisms of AAU and AS. Investigation of genomewide polygenic risk scores of AS alone and AS with AAU both showed strong discriminatory capacity and high accuracy in risk prediction. Our findings suggest PRS based on GWAS data can quantify individual AS and AAU risks in clinically significant ways, potentially leading to the effective implementation of genetic discoveries in healthcare applications.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors thank all participating subjects with AS and healthy individuals who provided the DNA and clinical information necessary for this study. We would like to acknowledge the contributions of Anna Deminger, Sahlgrenska Academy at University of Gothenburg, and Urban Hellman, Umeå University, for their assistance in case recruitment and assessment and handling biological samples.

X.F.H. was funded by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (31771390). The TASC study was funded by the National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases (NIAMS) grants P01-052915, R01-AR046208. Funding was also received from the University of Texas Health Science Center at Houston CTSA grant UL1RR02418, Cedars-Sinai GCRC grant MO1-RR00425, Intramural Research Program, NIAMS/NIH, and Rebecca Cooper Foundation (Australia). This study was funded, in part, by Arthritis Research UK (Grants 19536 and 18797), by the Wellcome Trust (Grant number 076113), and by the Oxford Comprehensive Biomedical Research Centre ankylosing spondylitis chronic disease cohort (Theme Code: A91202). The New Zealand data was derived from participants in the Spondyloarthritis Genetics and the Environment Study (SAGE) and was funded by The Health Research Council, New Zealand. H.X. was funded by the National Natural Science Foundation of China Grant 81020108029 and 30872339. French sample collection was performed by the Groupe Française d'Etude Génétique des Spondylarthrites, coordinated by Professor Maxime Breban, and funded by the Agence Nationale de Recherche GEMISA grant reference ANR-10-MIDI-0002. We acknowledge the Understanding Society: The UK Household Longitudinal Study. This is led by the Institute for Social and Economic Research at the University of Essex and funded by the Economic and Social Research Council. The survey was conducted by NatCen and the genomewide scan data were analyzed and deposited by the Wellcome Trust Sanger Institute. Information on how to access the data can be found on the Understanding Society website https: www.understandingsociety.ac.uk/. We acknowledge and thank the TCRA AS Group for their support in recruiting patients for the study. M.A.B. is funded by a National Health and Medical Research Council (Australia) Senior Principal Research Fellowship, and support for this study was received from a National Health and Medical Research Council (Australia) program Grant (566938) and project Grant (569829), and from the Australian Cancer Research Foundation and Rebecca Cooper Medical Research Foundation. We are also very grateful for the invaluable support received from the National Ankylosing Spondylitis Society (UK) and Spondyloarthritis Association of America in case recruitment. Additional financial and technical support for patient recruitment was provided by the National Institute for Health Research Oxford Musculoskeletal Biomedical Research Unit and NIHR Thames Valley Comprehensive Local Research and an unrestricted educational grant from Abbott Laboratories. The authors acknowledge the sharing of data and samples by the BSRBR-AS Register in Aberdeen. Chief Investigator, Prof Gary Macfarlane and Dr Gareth Jones, Deputy Chief Investigator, created the BSRBR-AS study, which was commissioned by the British Society for Rheumatology, funded in part by Abbvie, Pfizer, and UCB. We are grateful to every patient, past and present staff of the BSRBR-AS register team, and to all clinical staff who recruited patients, followed them up and entered data – details here: https://www.abdn.ac.uk/iahs/research/epidemiology/spondyloarthritis.php#panel1011. Funding was also received from the Swedish Research Council and The Swedish state under the agreement between the Swedish government and the county councils, the ALF agreement. The Irish data was derived from participants in ASRI – The Ankylosing Spondylitis Registry of Ireland, which is funded by unrestricted grants from Abbvie and Pfizer. Funding bodies involved played no role in the study design, performance, or preparation of this manuscript.

Disclosure: X.-F. Huang, None; Z. Li, None; E. De Guzman, None; P. Robinson, None; L. Gensler, None; M.M. Ward, None; M.H. Rahbar, None; M. Lee, None; M.H. Weisman, None; G.J. Macfarlane, None; G.T. Jones, None; E. Klingberg, None; H. Forsblad-d'Elia, None; P. McCluskey, None; D. Wakefield, None; J.S. Coombes, None; M.A. Fiatarone Singh, None; Y. Mavros, None; N. Vlahovich, None; D.C. Hughes, None; H. Marzo-Ortega, None; I. Van der Horste-Bruinsma, None; F. O'Shea, None; T.M. Martin, None; J. Rosenbaum, None; M. Breban, None; Z.-B. Jin, None; P. Leo, None; J.D. Reveille, None; B.P. Wordsworth, None; M.A. Brown, None

References

- 1. Miserocchi E, Fogliato G, Modorati G, Bandello F. Review on the worldwide epidemiology of uveitis. Eur J Ophthalmol. 2013; 23: 705–717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Gritz DC, Wong IG.. Incidence and prevalence of uveitis in Northern California; the Northern California Epidemiology of Uveitis Study. Ophthalmology. 2004; 111: 491–500; discussion 500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Nakao K, Ohba N.. [Prevalence of endogenous uveitis in Kagoshima Prefecture, Southwest Japan]. Nippon Ganka Gakkai Zasshi. 1996; 100: 150–155. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Dandona L, Dandona R, John RK, McCarty CA, Rao GN. Population based assessment of uveitis in an urban population in southern India. Br J Ophthalmol. 2000; 84: 706–709. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. D'Ambrosio EM, La Cava M, Tortorella P, Gharbiya M, Campanella M, Iannetti L. Clinical features and complications of the HLA-B27-associated acute anterior uveitis: a metanalysis. Semin Ophthalmol. 2017; 32: 689–701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Chang JH, McCluskey PJ, Wakefield D. Acute anterior uveitis and HLA-B27. Surv Ophthalmol. 2005; 50: 364–388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Monnet D, Breban M, Hudry C, Dougados M, Brezin AP. Ophthalmic findings and frequency of extraocular manifestations in patients with HLA-B27 uveitis: a study of 175 cases. Ophthalmology. 2004; 111: 802–809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Brewerton DA, Caffrey M, Nicholls A, Walters D, James DC. Acute anterior uveitis and HL-A 27. Lancet. 1973; 302: 994–996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Robinson PC, Claushuis TA, Cortes A, et al.. Genetic dissection of acute anterior uveitis reveals similarities and differences in associations observed with ankylosing spondylitis. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2015; 67: 140–151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Tsirouki T, Dastiridou A, Symeonidis C, et al.. A focus on the epidemiology of uveitis. Ocul Immunol Inflamm. 2018; 26: 2–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Derhaag PJ, Linssen A, Broekema N, de Waal LP, Feltkamp TE. A familial study of the inheritance of HLA-B27-positive acute anterior uveitis. Am J Ophthalmol. 1988; 105: 603–606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Robinson PC, Leo PJ, Pointon JJ, et al.. The genetic associations of acute anterior uveitis and their overlap with the genetics of ankylosing spondylitis. Genes Immun. 2016; 17: 46–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Huang XF, Chi W, Lin D, et al.. Association of IL33 and IL1RAP polymorphisms with acute anterior uveitis. Curr Mol Med. 2018; 17: 471–477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Li H, Hou S, Yu H, et al.. Association of genetic variations in TNFSF15 with acute anterior uveitis in Chinese Han. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2015; 56: 4605–4610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Wang Y, Huang XF, Yang MM, et al.. CFI-rs7356506 is a genetic protective factor for acute anterior uveitis in Chinese patients. Br J Ophthalmol. 2014; 98: 1592–1596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Burton PR, Clayton DG, Cardon LR, et al.. Association scan of 14,500 nonsynonymous SNPs in four diseases identifies autoimmunity variants. Nat Genet. 2007; 39: 1329–1337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Reveille JD, Sims AM, Danoy P, et al.. Genome-wide association study of ankylosing spondylitis identifies non-MHC susceptibility loci. Nat Genet. 2010; 42: 123–127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Evans DM, Spencer CCA, Pointon JJ, et al.. Interaction between ERAP1 and HLA-B27 in ankylosing spondylitis implicates peptide handling in the mechanism for HLA-B27 in disease susceptibility. Nat Genet. 2011; 43: 761–767. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Cortes A, Hadler J, Pointon JP, et al.. Identification of multiple risk variants for ankylosing spondylitis through high-density genotyping of immune-related loci. Nat Genet. 2013; 45: 730–738. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Ellinghaus D, Jostins L, Spain SL, et al.. Analysis of five chronic inflammatory diseases identifies 27 new associations and highlights disease-specific patterns at shared loci. Nat Genet. 2016; 48: 510–518. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Ranganathan V, Gracey E, Brown MA, Inman RD, Haroon N. Pathogenesis of ankylosing spondylitis - recent advances and future directions. Nat Rev Rheumatol. 2017; 13: 359–367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Brown MA. Breakthroughs in genetic studies of ankylosing spondylitis. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2008; 47: 132–137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Visscher PM, Wray NR, Zhang Q, et al.. 10 Years of GWAS discovery: biology, function, and translation. Am J Hum Genet. 2017; 101: 5–22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Brown MA, Wordsworth BP.. Genetics in ankylosing spondylitis - current state of the art and translation into clinical outcomes. Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol. 2017; 31: 763–776. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. van der Linden S, Valkenburg HA, Cats A. Evaluation of diagnostic criteria for ankylosing spondylitis. A proposal for modification of the New York criteria. Arthritis Rheum. 1984; 27: 361–368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Yang J, Lee SH, Goddard ME, Visscher PM. GCTA: a tool for genome-wide complex trait analysis. Am J Hum Genet. 2011; 88: 76–82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Loh PR, Danecek P, Palamara PF, et al.. Reference-based phasing using the Haplotype Reference Consortium panel. Nat Genet. 2016; 48: 1443–1448. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Durbin R. Efficient haplotype matching and storage using the positional Burrows-Wheeler transform (PBWT). Bioinformatics. 2014; 30: 1266–1272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Jia X, Han B, Onengut-Gumuscu S, et al.. Imputing amino acid polymorphisms in human leukocyte antigens. PLoS One. 2013; 8: e64683. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Purcell S, Neale B, Todd-Brown K, et al.. PLINK: a tool set for whole-genome association and population-based linkage analyses. Am J Hum Genet. 2007; 81: 559–575. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Pruim RJ, Welch RP, Sanna S, et al.. LocusZoom: regional visualization of genome-wide association scan results. Bioinformatics. 2010; 26: 2336–2337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Zhu Z, Zhang F, Hu H, et al.. Integration of summary data from GWAS and eQTL studies predicts complex trait gene targets. Nat Genet. 2016; 48: 481–487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Lloyd-Jones LR, Holloway A, McRae A, et al.. The genetic architecture of gene expression in peripheral blood. Am J Hum Genet. 2017; 100: 228–237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Speed D, Balding DJ.. MultiBLUP: improved SNP-based prediction for complex traits. Genome Res. 2014; 24: 1550–1557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Leo PJ, Madeleine MM, Wang S, et al.. Defining the genetic susceptibility to cervical neoplasia-A genome-wide association study. PLoS Genet. 2017; 13: e1006866. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Evans DM, Spencer CC, Pointon JJ, et al.. Interaction between ERAP1 and HLA-B27 in ankylosing spondylitis implicates peptide handling in the mechanism for HLA-B27 in disease susceptibility. Nat Genet. 2011; 43: 761–767. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. International Genetics of Ankylosing Spondylitis Consortium (IGAS), Cortes A, Hadler J, et al.. Identification of multiple risk variants for ankylosing spondylitis through high-density genotyping of immune-related loci. Nat Genet. 2013; 45: 730–738. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Cortes A, Pulit SL, Leo PJ, et al.. Major histocompatibility complex associations of ankylosing spondylitis are complex and involve further epistasis with ERAP1. Nat Commun. 2015; 6: 7146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Silverberg MS, Mirea L, Bull SB, et al.. A population- and family-based study of Canadian families reveals association of HLA DRB1*0103 with colonic involvement in inflammatory bowel disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2003; 9: 1–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Lappalainen M, Halme L, Turunen U, et al.. Association of IL23R, TNFRSF1A, and HLA-DRB1*0103 allele variants with inflammatory bowel disease phenotypes in the Finnish population. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2008; 14: 1118–1124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Gal A, Li Y, Thompson DA, et al.. Mutations in MERTK, the human orthologue of the RCS rat retinal dystrophy gene, cause retinitis pigmentosa. Nat Genet. 2000; 26: 270–271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Lemke G. Biology of the TAM receptors. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol. 2013; 5: a009076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Abd El-Aziz MM, Barragan I, O'Driscoll CA, et al.. EYS, encoding an ortholog of Drosophila spacemaker, is mutated in autosomal recessive retinitis pigmentosa. Nat Genet. 2008; 40: 1285–1287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Ye F, Li Q, Ke Y, et al.. TAM receptor knockout mice are susceptible to retinal autoimmune induction. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2011; 52: 4239–4246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Waterborg CEJ, Koenders MI, van Lent P, van der Kraan PM, van de Loo FAJ. Tyro3/Axl/Mertk-deficient mice develop bone marrow edema which is an early pathological marker in rheumatoid arthritis. PLoS One. 2018; 13: e0205902. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Graham DK, Dawson TL, Mullaney DL, Snodgrass HR, Earp HS. Cloning and mRNA expression analysis of a novel human protooncogene, c-mer. Cell Growth Differ. 1994; 5: 647–657. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Behrens EM, Gadue P, Gong SY, Garrett S, Stein PL, Cohen PL. The mer receptor tyrosine kinase: expression and function suggest a role in innate immunity. Eur J Immunol. 2003; 33: 2160–2167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Angelillo-Scherrer A, de Frutos P, Aparicio C, et al.. Deficiency or inhibition of Gas6 causes platelet dysfunction and protects mice against thrombosis. Nat Med. 2001; 7: 215–221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Yeoh EJ, Ross ME, Shurtleff SA, et al.. Classification, subtype discovery, and prediction of outcome in pediatric acute lymphoblastic leukemia by gene expression profiling. Cancer Cell. 2002; 1: 133–143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Graham DK, Salzberg DB, Kurtzberg J, et al.. Ectopic expression of the proto-oncogene Mer in pediatric T-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Clin Cancer Res. 2006; 12: 2662–2669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Scott RS, McMahon EJ, Pop SM, et al.. Phagocytosis and clearance of apoptotic cells is mediated by MER. Nature. 2001; 411: 207–211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Cabezon R, Carrera-Silva EA, Florez-Grau G, et al.. MERTK as negative regulator of human T cell activation. J Leukoc Biol. 2015; 97: 751–760. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Reveille JD, Zhou X, Lee M, et al.. HLA class I and II alleles in susceptibility to ankylosing spondylitis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2019; 78: 66–73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Brown MA, Kennedy LG, MacGregor AJ, et al.. Susceptibility to ankylosing spondylitis in twins: the role of genes, HLA, and the environment. Arthritis Rheum. 1997; 40: 1823–1828. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Pedersen OB, Svendsen AJ, Ejstrup L, Skytthe A, Harris JR, Junker P. Ankylosing spondylitis in Danish and Norwegian twins: occurrence and the relative importance of genetic vs. environmental effectors in disease causation. Scand J Rheumatol. 2008; 37: 120–126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.