Abstract

Immunotherapies such as immune checkpoint blockade benefit only a portion of patients with head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. The multidisciplinary field of nanomedicine is emerging as a promising strategy to achieve maximal anti-tumor effect in cancer immunotherapy and to turn non-responders into responders. Various methods have been developed to deliver therapeutic agents that can overcome bio-barriers, improve therapeutic delivery into the tumor and lymphoid tissues and reduce adverse effects in normal tissues. Additional modification strategies also have been employed to improve targeting and boost cytotoxic T cell-based immune responses. Here, we review the state-of-the-art use of nanotechnologies in the laboratory, in advanced preclinical phases as well as those running through clinical trials assessing their advantages and challenges.

Keywords: nanotherapeutics; drug delivery; cancer immunotherapy; nanovaccine; head and neck squamous cell carcinoma, human papillomavirus

Introduction

Head and neck squamous cell carcinoma (HNSCC) still remains the sixth most common malignancy worldwide with >830,000 cases and >430,000 deaths each year 1. Although the overall 5-year survival rate of patients with HNSCC is about 40-60%, in cases with locoregionally advanced disease this number may be much lower 2. During the past few years, cancer immunotherapy, especially immune checkpoint blockade (ICB) approaches, were able to generate durable immune responses and led to improved survival in patients with advanced HNSCC, according to the results of clinical trials 3, 4. In 2019, pembrolizumab, an anti-programmed cell death-1 (anti-PD1) antibody, in combination with chemotherapy has been approved for the first-line treatment of patients with recurrent or distant metastatic (R/M) HNSCC. However, the overall response rates were about 20% in advanced HNSCC patients who received PD1 or PD-ligand (L)1 checkpoint inhibitor treatments 4-6. Notably, a number of severe immune-related adverse events such as dermatitis, colitis, hepatitis, and pneumonitis are also developed in some patients and required a delayed administration of ICB treatment or other interventions 7, 8. Other strategies like adoptive cell transfer or anti-cancer vaccines are limited by reduced T cell activity, the development of autoimmune toxicity or weak immunogenicity 9, 10. Studies revealed that the heterogeneity in the spatial distribution of tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes (TILs), cancer stem cell (CSCs)-related immune invasion and the immunosuppressive microenvironment are the main factors contributing to the lower efficacy of ICB treatment at clinical stage 10, 11. In addition, similarly to the conventional cytotoxic chemotherapy drugs, immunotherapy is constrained by transport processes. The limited capability of immune-checkpoint inhibitors to permeate into the targeted solid tumor tissue would compromise the treatment efficacy 12, 13. Thus, a conceptual understanding of cancer immunotherapy resistance as well as the development and implementation of pipelines to maximize therapeutic outcomes and reduce severe immune-related systemic toxicity is urgently needed.

One important consideration for the development of optimized immunotherapies is nanomedicine, i.e. utilizing nanotechnology to improve the transport of therapeutics selectively into tumor tissue, remodel the immunity, minimize toxicity and immune-related adverse events 14. First, nanosized carriers can incorporate several functional elements to protect drugs from degradation, improve sustained drug release, enhance permeation, and deliver tumor-associated antigens (TAA), chemotherapy drugs, phototherapy sensitizers, siRNAs, etc. 13. These characteristics would enable the achievement of therapeutic concentrations of drugs with limited toxicity. Second, the ability to recognize pathological tissues distinct from normal tissues would improve site-specific delivery of nanotherapeutics 13. One example is the multistage vector platform (MSV), composed of three components with different manipulation that can display different biodistribution profiles 15. The first stage vector is porous silicon microparticles which can circulate in the blood and overcome transport bio-barriers to reach the tumor vasculature. The second stage vector is nanoparticles (NPs) loaded in the pores of porous silicon microparticles that can be released into the tissue upon the degradation of silicon materials. Finally, therapeutic small molecules loaded in the nanoparticles can be delivered and effective on both tumor cells and immune cells 15. Taking advantages of these unique properties, preclinical studies have demonstrated that these approaches are successful in cancer vaccination by co-delivery of TAAs, neoantigens or adjuvants to dendritic cells (DCs), the design of artificial antigen presenting cells (aAPCs) and reversing the immunosuppressive microenvironment 14.

In this review, we summarize nanotechnology based strategies in the development of treatment modalities to improve the outcome and to decrease the toxicity of immunotherapeutics against HNSCCs. Ultimately, such efforts will help to find the potential targets and build a foundation for the development of novel nano-immunotherapeutics for HNSCC.

Immuno-oncology features of HNSCC

HNSCC is an immunosuppressive disease with phenotypic and functional intratumor cellular heterogeneity 16, 17. HNSCC tumors interfere with the immune system by employing many mechanisms that modulate functions of immune cells to develop immune evasion and immune escape (for more detailed information, please refer to reviews by Albers et al. and Qian et al. 18, 19). The potential mechanisms for the dysfunction of biological steps in immunity against cancer cells being responsible for the limited response to ICB treatment have been explored in HNSCC 11, 20-26. Recently, three tumor-immunophenotypes and related molecular pathways have been recognized according to the spatial distribution of T cells within the tumor microenvironment 23. The presence of high PD-L1 expression, high density of TILs and B cells, IFN-γ signatures and intact antigen presentation (i.e., high tumor mutation burden) is characterized as the inflamed phenotype 23, 27. Immune-excluded phenotype is defined as an immunosuppressive tumor microenvironment by the presence of myeloid-derived suppressor cells (MDSCs), reactive stroma, TGF-β signatures, low major histocompatibility complex class I (MHC-I) expression, low TILs and angiogenesis 16, 27, 28. Immune-desert tumors are associated with lack of TILs, neuroendocrine features, low MHC-I expression, fatty acid metabolism and Wnt/β-catenin signaling 23, 27. A clinical study has further identified distinct immunological profiles in oropharyngeal cancer (OPC) being related to ICB responses 26. In addition, activation of alterative immune checkpoints such as T-cell immunoglobulin mucin-3 (TIM-3) were identified to confer resistance to therapeutic PD-1 inhibition 29. Moreover, we and others found that CSCs play an important role in immune suppression, immune evasion and immune escape. The non-specific target of HNSCC-CSCs may contribute to treatment resistance, tumor recurrence and metastasis 10, 16. The immune heterogeneity described herein raises clinical challenges for patient stratification and for designing a well-tailored immunotherapy.

Currently, carcinogen-exposure-associated tumors represent the majority of HNSCCs with a rising incidence of high-risk human papillomavirus (HR-HPV)-driven HNSCCs 30. HR-HPV-driven HNSCCs show distinct clinical presentations regarding treatment response, overall survival and prognosis compared to HR-HPV negative HNSCCs 31. Accordingly, the 8th edition of the American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC) downstaged the HR-HPV-associated OPC compared to HR-HPV negative OPC 32. Notably, the immune features of HR-HPV-driven tumors are distinguishable from HR-HPV negative tumors. For example, a B-cell associated signature within the population of TILs was prominent in HR-HPV positive HNSCCs compared to HPV-negative HNSCCs 33. A spectrum of different immune lineages between HR-HPV-driven and -negative HNSCC has recently been demonstrated by a single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq) analysis 34. Specifically, CD4+ T follicular helper (CD4+ Tconv) cells (TFP) were significantly enriched in TILs of HR-HPV-driven tumors. HNSCC patients with a gene expression signature associated with CD4+ Tconv cells had a longer progression-free survival 34. The identified differences between the two tumor types within the same anatomical site may exist due to virus-derived immunity. Notably, TFP play a dominant role in the production of long-lasting humoral immunity which is important for immunization 35. Further, differentiation of CD4+ T cells into either TFP or type 1 helper T (TH1) cells can be modulated by exposure of DCs to type I interferon in a recombinant vesicular stomatitis virus (VSV) infection model 36. Regarding to the ICB treatment, patients with HR-HPV+ HNSCC had a better response to anti-PD-1 treatment 37. The total PD-1+ TIL was identified to be higher in HR-HPV+ patients with better clinical outcome 38. RNA-sequencing analysis demonstrates that patients with HR-HPV+ OPC has immune rich phenotype and were associated with a favorable response to anti-PD-1/PD-L1 therapy 26. Further, dysfunctional PD-1high CD8+ TILs were more frequent in HR-HPV negative patients with worse outcome 38. However, nivolumab treatment produces tumor regression in only a minority of patients with recurrent HR-HPV-driven cancer 37. A recent study demonstrated that treatment with nivolumab in addition with the HR-HPV 16 vaccine ISA101 increased the overall response rate to 33% comparing to 16% to 22% with ICB alone in patients with HR-HPV-driven tumor 39. Ultimately, a substantial strategy for immunotherapy in HNSCC and an in-depth study of the dissimilar of immune responses between the two tumor types would be necessary.

Nanotechnology-based-drug-delivery systems

Nano-scaled materials such as liposomes, micelles, MSV and metal-organic frameworks (MOFs) are optimized as nanocarriers to incorporate with anti-cancer drugs or biomolecules for the development of localized drug delivery systems 40. For example, anticancer drugs including doxorubicin, paclitaxel, cisplatin, topotecan, 5-fluorouracil and small interfering RNA (siRNA) have been developed for cancer nanotherapeutics 41, 42. In HNSCCs, earlier studies demonstrated that tumor growth was inhibited and survival was prolonged in response to treatment with cisplatin-loaded polymeric micelles (CDDP/m) in mouse models 12, 43. Specifically, the delayed release of CDDP from the polymeric shell can overcome the degradation of free drug by interaction with glutathione 12. More importantly, this platform is able to concurrently target CSCs, because CSCs have an increased glutathione level compared to bulk tumor cells. Additionally, greater therapeutic efficacy was achieved upon utilization of cyclic Arg-Gly-Asp (cRGD) peptide-installed CDDP/m (cRGD-CDDP/m) that the αvβ5 integrins overexpressed in HNSCC-CSCs could be successfully recognized by the cRGD peptide 44. Moreover, cRGD-CDDP/m has been found to home to lymph node metastases rapidly 44. In this regard, clinical trials are currently underway to test the feasibility of cRGD-CDDP/m against pancreatic cancer (NC-6004, Nanocarrier Co., Ltd) and are expected to be investigated in HNSCC. Similar results have been achieved with nanoparticles formulated with 5-FU or Doxorubicin in vitro and in vivo compared to free drugs 45, 46. Notably, the MSV platform incorporating three components on different spatial scales (microparticles, nanoparticles and small molecules) is designed to overcome a wide range of biological barriers through bio-nano interactions 15. At clinical stage, Abraxane, nanoparticle albumin-bound paclitaxel has been evaluated as a part of combination chemo-radiotherapy in locally advanced HNSCC and R/M HNSCC 47.

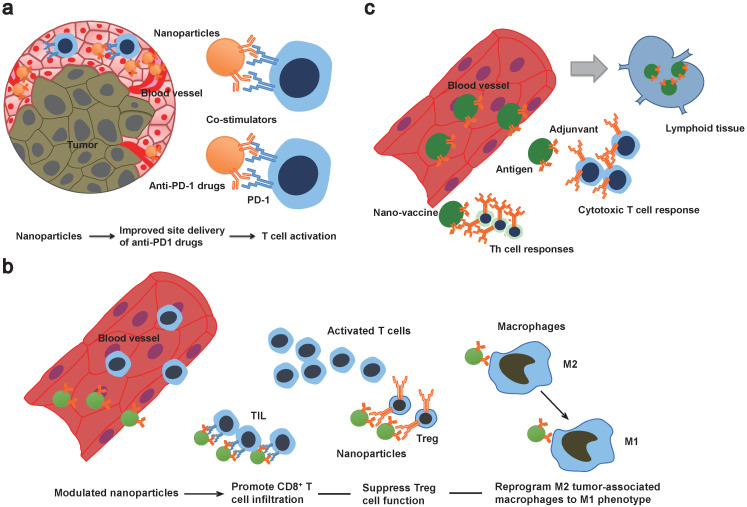

In addition to nanoformulated conventional drugs, modulation of immune checkpoint inhibitors is also expected to improve the treatment efficacy and overcome sequential immune-related side effects (Figure 1, Table 1). For instance, a design of co-delivery of anti-PD1 and antitumor necrosis factor receptor superfamily member 4 (aOX40) by PLGA nanoparticles can spatiotemporally co-delivery drugs into the tumor site 48. Specifically, higher rates of T cell activation and increased immunological memory with enhanced therapeutic efficacy were observed in melanoma and breast tumor models 48. This dual immunotherapy nanoparticle-based platform demonstrates a novel strategy to improve the combination immunotherapy. Another strategy is utilizing nanomaterials that enable triggered activation or induce drug release in pathological tissue specifically. A clinical stage example is drug CX-072, a protease-cleavable Probody therapeutic directed against programmed cell death ligand 1 (PD-L1), for patients with advanced or recurrent solid tumors or lymphomas that currently is in phase I/II clinical trials (https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT03013491). In particular, the antigen-binding site of the Probodies is masked with a peptide, and in the tumor microenvironment, the masking peptide can be cleaved by tumor-associated proteases that enable the release of Probody antibody 49. This approach can minimize the antigen binding to normal cells and reduce autoimmune-like effects 49.

Figure 1.

Schematic illustration of multifunctional properties of nanoimmunotherapeutics. a) Nanotechnology-based theranostic approaches can improve transport spatiotemporally. Co-delivery of stimulators or conventional drugs can be developed as combination therapy. b) Modulated nanoplatforms can prime a suppressive tumor microenvironment. c) Nanovaccine co-delivered tumor antigens and adjuvants can be drained into lymphoid tissue and induce strong antigen specific cytotoxic T cell and Th cell responses. TIL: tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes.

Table 1.

Examples of nanoimmunotherapeutics in head and neck squamous cell carcinoma

| Delivery platform | Composition | Cancer model | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| Immunotherapy | |||

| Multidomain peptide assembled nanofibrous matrix | K2(SL)6K2 multidomain peptide, Cyclic dinucleotides | Mouse HNSCC (MOC2-E6E7 cells) | 83 |

| PC7A nanoparticle | 2-(Hexamethyleneimino) ethyl methacrylate (C7A-MA) monomer, PEG-b-PC7A copolymer, HPV-16 E7 peptide | TC-1 tumor-bearing mice | 66 |

| PLGA nanoparticle | Poly (lactic-co-glycolic acid), Nano-diamino-tetrac | Oral cancer cell lines (OEC-M1 cells) | 84 |

| Tocopherol-modified hyaluronic acid nano suspension | Tocopherol-modified hyaluronic acid (HA-Toco), TLR7/8 dual agonist resiquimod (R848) | Mouse OSCC (AT84 cells) | 85 |

| Combination therapy | |||

| Nanoscale metal-organic framework | DBP-Hf nMOF based on 5,15-di (p-benzoato) porphyrin bridging ligand, Indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase | Mouse HNSCC (SQ20B cells) | 86 |

| Polydopamine coated spiky gold nanoparticles | Polydopamine coated spiky gold nanoparticles, Doxorubicin | Mouse HNSCC, lung metastasis (TC-1 cells) | 87 |

| Liposome | DOTMA: cholesterol 1: 1, Murine Interleukin 2, Murine Interleukin 12 plasmid | Mouse HNSCC (SCCVII cells) | 88 |

| Co-assembled binary telodendrimers nanoparticle | PEG5K-CA4-ICGD4 (PCI): a linear PEG block, four dendritic hydrophobic photothermal conversion agents (indocyanine green derivatives, ICGD) and four dendritic cholic acids (CA); PEG5K-Cys4-L8-CA8 (PCLC): PEG, four cysteines and eight CA. PCI: PCLC 1: 1, Doxorubicin, Imiquimod | Mouse oral cancer (OSC-3 cells) | 89 |

| Polyanhydride nanoparticle (20: 80 CPTEG: CPH) | 20: 80 CPTEG: CPH. CPTEG: 1,8-bis (p-carboxyphenox-y)-3,6-dioxaoctane; CPH: 1,6-bis (p-carboxyphenoxy) hexane, IL-1α | Mouse HNSCC (SQ20B and Cal-27 cells) | 90 |

| PLGA-PEG nanoparticle | Poly (lactic-co-glycolic acid)-PEG, Doxorubicin, R848, CCL20, Poly (I: C) | TC-1 tumor-bearing mice | 91 |

| Sterically stabilized cationic liposome | DC-Chol: DOPE: PEG-PE (4: 6: 0.06), CpG-ODN | Mouse HNSCC (KCCT873 cells) | 92 |

| PC7A nanoparticle | 2-(Hexamethyleneimino) ethyl methacrylate (C7A-MA) monomer, PEG-b-PC7A copolymer, HPV-16 E7 peptide | TC-1 tumor-bearing mice | 93 |

| Nanovaccine | |||

| Poly (propylene sulfide) nanoparticle | Poly (propylene sulfide) nanoparticle with disulfide conjugated peptide, HPV-16 E7 peptide, CpG-B 1826 oligonucleotide | TC-1 tumor-bearing mice | 94 |

| R-DOTAP cationic lipid nanoparticle | R-1,2-dioleoyl-3-trimethyl-ammonium-propane (R-DOTAP), HPV-16 E7 and other antigens | TC-1 tumor-bearing mice | 67 |

| DOTMA/DOPE liposome | DOTMA, DOPE, HPV-16 E7 mRNA | TC-1 tumor-bearing mice | 60 |

| PLGA nanoparticles | Poly (lactic-co-glycolic acid), HPV-16 E7 peptide, ploy (I: C) | TC-1 tumor-bearing mice | 95 |

| PLGA nanoparticles | Poly (lactic-co-glycolic acid), Mutated HPV-16 E7 and E6/E7 protein, R848, poly (I: C) | TC-1 tumor-bearing mice, cynomolgus monkey | 96 |

| DOTMA/DOPE liposome | DOTMA, DOPE, Plasmid encoding HPV-16 E6, E7 | TC-1 tumor-bearing mice | 69 |

| Synthetic high-density lipoprotein nanodisc | 1,2-Dimyristoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphocholine (DMPC), ApoA1 mimetic peptide 22A, HPV-16 E7 peptide, MPLA, CpG | TC-1 tumor-bearing mice | 97 |

| Liposome | Cholesterol/DOPC/PEG-DSPE/maleimide-PEG-DSPE at 35/60/2.5/2.5 or 35/62.5/0/2.5 mol%, Anti-CD137, IL-2 | TC-1 tumor-bearing mice | 98 |

| Mesoporous silica micro-rod | Mesoporous silica micro-rod, Polyethyleneimine, HPV-16 E7 peptide, GM-CSF, CPG-ODN | TC-1 tumor-bearing mice | 99 |

| Q11 peptide assembled nanofiber | Peptides Q11 (Ac-QQKFQFQFEQQ-Am), E7 (44-62) was appended to the N terminus of peptide Q11 through a flexible linker, Ser-Gly-Ser-Gly, HPV-16 E7 peptide | TC-1 tumor-bearing mice | 100 |

| Hyaluronic acid-modified cationic lipid-PLGA hybrid nanoparticles | Cationic lipid (3β-[N-(N′,N′, dimethylaminoethane)-carbamoyl] cholesterol hydrochloride, DC-Chol), Hyaluronic acid, poly (lactic-co-glycolic acid), HPV-16 E7 peptide, ploy (I: C), CpG-ODN | TC-1 tumor-bearing mice | 101 |

| Heterocyclic lipid nanoparticle | Dihydroimidazole-linked lipids A2-Iso5-2DC18 and A12-Iso5-2DC18, HPV-16 E7 mRNA | TC-1 tumor-bearing mice | 102 |

| Supercharged green fluorescent protein | Supercharged green fluorescent protein (+36 GFP), HPV-16 E7 DNA, protein | TC-1 tumor-bearing mice | 103 |

| PLGA nanoparticle | PLGA NP coated with murine aCD40-mAb FGK45, HPV-16 E7, Pam3CSK4, Poly (I: C), aCD40-mAb | TC-1 tumor-bearing mice | 104 |

| Carboxymethyl dextran-based polymeric conjugate | Carboxymethyl dextran, ovalbumin was chemically affixed to CMD via reductive amination between the reducing end group of CMD and the amino group of OVA, Ovalbumin peptide | TC-1 tumor-bearing mice | 105 |

| HIV tat peptide | 18-mer cationic peptide RKKRRQRRRRAHYNEVTF (Tat-E7), HPV-16 E7 peptide, GM-CSF DNA | TC-1 tumor-bearing mice | 106 |

| PEG-PE micelle | Polyethylene glycol-phosphatidylethanolamine (PEG-PE) micelles, Ovalbumin peptide | TC-1 tumor-bearing mice | 107 |

| Bacterial outer membrane vesicles | Escherichia coli recombinant DH5α cell-derived outer membrane vesicles, HPV-16 E7 protein | TC-1 tumor-bearing mice | 108 |

| PLGA nanoparticles | Poly (lactic-co-glycolic acid), Cell or tumor lysate | HNSCC cell line (FaDu and FAT cells) | 109 |

| Tumor-derived autophagosome | Autophagosome secreted by SCC7 tumor cells | Mouse HNSCC (SCC7 cells) | 110 |

| Nanosatellite | Polysiloxane-containing polymer-coated iron oxide core with inert gold satellites, E6/E7 peptide +cGAMP | Mouse HNSCC (PCI-13, UMSCC22b, UMSCC47, and FaDu cells) | 65 |

| Liposome | Cationic lipid reagent DOTAP, Total tumor RNA | Nasopharyngeal Carcinoma cell line (C15 and C666-1 cells) | 111 |

| Branched amphiphilic peptide capsules | Peptides bis (FLIVIGSII)-K-K4 and bis (FLIVI)-K-K4, Plasmid DNA encoding HPV-16 E7 | TC-1 tumor-bearing mice | 112 |

| Virus-like particles | E7 inserted into Hepatitis B virus core antigen (aa. 1-149), HPV-16 E7 epitope | TC-1 tumor-bearing mice | 113 |

| Liposome | DOTAP and cholesterol (1: 1 or 1: 0 molar ratio), Plasmid DNA, HPV-16 E7 peptide | TC-1 tumor-bearing mice | 114 |

| Chitosan-coated selenium nanoparticle | Chitosan-coated selenium nanoparticle, Fluc-mRNA | Nasopharyngeal carcinoma cell line (KB cells) | 115 |

| PMIDA coated CoO nanoparticles | N-Phosnomethyliminodiacetic acid coated cobalt oxide nanoparticle, Human oral carcinoma (KB) cell lysate | Oral cancer cell line (KB cells) | 116 |

| Mesoporous silica rods | Mesoporous silica rods, GM-CSF + CpG-ODN + E7 peptide | Mouse HNSCC (MOC2-E6E7 cells) | 117 |

Abbreviation: DBP-Hf: di (p-benzoato) porphyrin-hafnium; nMOF: nanoscale metal-organic framework; HNSCC: head and neck squamous cell carcinoma; CPTEG: 1,8-bis (p-carboxyphenox-y)-3,6-dioxaoctane; CPH: 1,6-bis (p-carboxyphenoxy) hexane; R848: dual TLR7/8 activator Resiquimod; PLGA: poly (lactic-co-glycolic acid); CCL20: Macrophage Inflammatory Protein-3 alpha (MIP3α); CpG-ODN: CpG Oligodeoxynucleotides; HPV-16: human papillomavirus type 16; TLR7/8: toll-like receptor 7 and 8; OSCC: oral squamous cell carcinoma; R-DOTAP: R-1,2-dioleoyl-3-trimethyl-ammonium-propane; DMPC: 1,2-Dimyristoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphocholine; DOPC: Dioleoylphosphocholine; PEG: polyethylene glycol; DSPE: distearoylphosphoethanolamine; GM-CSF: granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor; Q11: Ac-QQKFQFQFEQQ-Am; GFP: green fluorescent protein; NP: nanoparticles; CMD: carboxymethyl dextran; OVA: ovalbumin; cGAMP: cyclic GMP-AMP; PMIDA: N-Phosnomethyliminodiacetic acid; CoO: cobalt oxide.

Immune-priming approaches

In order to maximize the immune therapeutic effect, modulating the tumor microenvironment is also under investigation (Figure 1). For example, an in vivo T cell targeted drug delivery system incorporating nanoparticles with antibodies and small molecules has been developed. Compared to free drugs, this approach enables less dosage to confer the ICB effect of PD1+ T cells and to reduce toxicity 50. Additionally, this approach co-delivers a TLR7/8 agonist that can promote CD8+ T cell infiltration into the tumor site 50. In another study, tLyp1 peptide-modified hybrid nanoparticles conjugated with the drug Imatinib was shown to target and modulate intratumoral Treg cell suppression through inhibition of STAT3 and STAT5 phosphorylation 51. When combined with anti-cytotoxic T-lymphocyte antigen-4 (anti-CTLA-4) treatment, it was shown to reduce of Treg cells and increase of CD8+ T cells infiltration at the tumor site and consequently elevate the survival rate in a mouse model 51. Zhang et al. developed lipid nanoparticles incorporating with the tumor-targeting peptide iRGD, a PI3K inhibitor and a α-GalCer agonist of therapeutic T cells 52. They found this systematic treatment could reverse the tumor microenvironment from immune-suppressive to immune-stimulatory and enable tumor-specific CAR-T cells homing to the cancer lesion 52. In addition to modulating the T cells, nanoparticles formulated with mRNAs encoding interferon regulatory factor 5 and IKKb kinase have shown its ability to reprogram tumor-associated macrophages from M2 phenotype to M1 phenotype. Because M2 phenotype is associated with immunosuppressive functions leading to tumor progression, metastases and therapy resistance, this complement approach would enable physicians to obviate immunosuppression and to design a companion strategy to augment the treatment efficacy of immunotherapy 53. It should be noted that, a recent study demonstrated that maintaining both phenotypes of M1 and M2 in the tumor microenvironment with a fine-turned ratio rather than a polarization to all-M1 population would improve the treatment efficacy of nanoparticle-mediated chemotherapy 54. Taken together, these findings present a straightforward solution to improve antitumor effect of immunotherapy by a repertoire of nanoparticles loaded with drugs in modulating the tumor microenvironment.

Nanovaccines

Successful therapeutic cancer vaccines depend on the recognition of tumor specific antigens, co-delivery of adjuvant and the delivery vehicles. In HNSCC, specific antigens such as HR-HPV oncogenic proteins, p53 and CSC-related proteins can prime immune cells to induce a robust immune response 19, 55. For example, vaccination targeted to HR-HPV E6 and E7 oncoproteins can induce T-cell responses against HPV-16 and a complete histologic response 39, 56. Adjuvant DC-based vaccination against p53 has shown modest vaccine-specific immunity in patients with HNSCC 55. Other strategies, e.g. targeting stem cell transcription factors like NANOG might eradicate CSCs particularly 57. However, their clinical efficacies may be limited in advanced HNSCC due to the immunosuppressive factors in the tumor microenvironment and by the sequential physical spatio-temporal peculiarities 19. Nanomedicine has the potential to facilitate vaccination-induced antitumor effects and to reverse immune suppression. Because therapeutic agents can be freely selected and congregated on nanocarriers according to the intended application, nanovaccine can not only codeliver tumor antigens and adjuvants to lymphoid tissues in close proximity, but also further enhance therapeutic efficacy by loading with immunosuppressive inhibitors or immunostimulatory compounds 58.

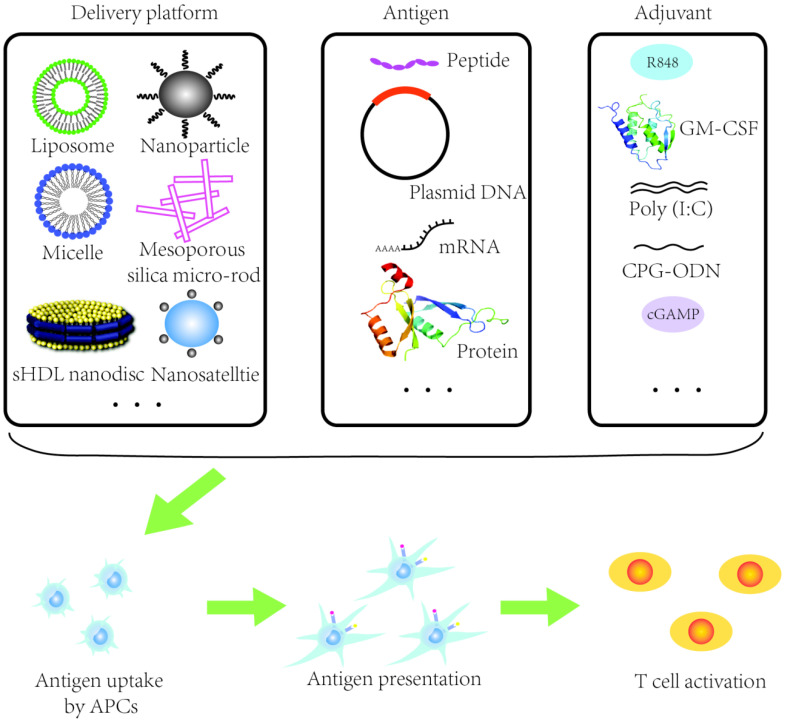

"Proof of concept" studies have shown that nanocarriers can successfully co-deliver tumor antigens and adjuvants and the expansion of tumor-specific T cells can be rapidly potentiated (Figure 2) 59. Nanomaterials such as liposomes or poly lactic-co-glycolic acid (PLGA) nanoparticles have been utilized to design therapeutic HR-HPV vaccine (Table 1). It has been shown that HR-HPV nanovaccines induce a strongly T cell immunity in preclinical studies. For instance, a liposomal HPV16 mRNA formulation, RNA-lipoplex (RNA-LPX) was administered intravenously in murine HR-HPV16-positive TC-1 and C3 tumor models 60. This approach displayed a robust E7 antigen-specific CD8+ T cell response with a strong and sustainable memory phenotype and a less immune suppressive microenvironment 60. Moreover, the combination of anti-PD-L1 treatment augmented the complete remissions of tumor and improved overall survival, and importantly, a late tumor relapse 60. Nanovaccine with tumor antigen MUC1 mRNA designed against triple negative breast cancer in combination with an anti-CTLA-4 monoclonal antibody can be successfully delivered to DCs in lymph nodes resulting in an enhanced T cell anti-tumor immune response 61. MUC1 is expressed in HNSCC and it has been shown in a MUC1-specific CAR-T cell therapy approach in vitro and in vivo 62. In another approach, researchers fused cancer cells with DCs and used the fusion cells' membrane to derive cytomembrane nanovaccine particles that simulated a direct T cell activation and indirect DC-mediated T cell activation 63. The therapeutic effect of nanovaccines was conferred by their phenotype mimicking tumor cells and antigen presenting cells simultaneously resulting in strong immune responses against cancer cells. Despite breast and colorectal cancer being used in this study, DC-HNSCC cell fusions have been created before 64 and could be employed similarly in future studies.

Figure 2.

Schematic illustration of a nanovaccine. APCs: antigen presenting cells. sHDL: synthetic high-density lipoprotein. Ploy(I:C): Ploy-deoxy-inosinic-deoxy-cytidylic acid. GM-CSF: granulocyte-macrophage colony stimulating factor. CpG-ODN: CpG oligodeoxynucleotides. cGAMP: Cyclic guanosine monophosphate-adenosine monophosphate.

As shown above, nanovaccines hold a great promise as a tool to synergize with ICB. Recently, Tan et al. identified the oncogene SOX2 to facilitate the immune suppression by the STING-type I interferon (IFN-I) signaling pathway in HNSCCs 65. The authors further developed a novel nanosatellite vaccine delivery system incorporating STING agonist and tumor antigens and demonstrated a rapid accumulation in the lymph node, improved IFN-I signaling and TIL in the tumor microenvironment 65. Moreover, a combination of nanosatellite vaccine with anti-PD-L1 significantly expands tumor-specific CTLs and reduces PD-1high and Tim3+ CD8+ CTL 65. PC7A NP, a synthetic polymeric nanoparticle that incorporates tumor antigens can induce strong antigen-specific cytotoxic T cell and Th cell responses in tumor models of melanoma, colon cancer, and HPV-E6/E7 TC-1 tumors 66. Notably, PC7A NPPC7A NP is an ultra-pH sensitive nanoparticle that can transport into draining lymph nodes successfully and potentiate efficient cytosolic delivery of tumor antigens to antigen presenting cells (APCs) where type I interferon-stimulated genes were activated 66. Moreover, a long-term antitumor memory could be induced by the PC7A NP treatment, as seen by an inhibition of tumor formation in those tumor-free mice that were previously treated with nanovaccine and then rechallenged with tumor cells in the HPV-E6/E7 TC-1 tumor model 66. Synergistic with anti-PD1 antibodies, the PC7A nanovaccine has also shown an improved anti-tumor immunity and survival in the TC-1 model 66. In line with these studies, a HR-HPV nanovaccine formulating the CL 1,2-dioleoyl-3-trimethyl-ammonium-propane (DOTAP) and long HR-HPV peptides can successfully boost strong anti-tumor immunity and synergize with an anti-PD1 checkpoint inhibitor 67. As illustrated in Table 1, these studies have been focused on current vaccine strategies. More targets are currently discovered and nanomedicine is constantly evolving, promising a better impact for future immunotherapeutics.

A clinical study has shown that a liposomal vaccine combined with idiotype, a tumor-specific antigen, and adjuvant interleukin-2 (IL-2) induces sustained tumor-specific T-cell responses in lymphoma patients 68. It has been demonstrated that nanoparticles can also protect the degradation of mRNA vaccines to improve the systemic delivery of antigens to DCs where de novo T cell responses against vaccine antigens were observed in vitro and in patients with advanced melanoma in a phase I clinical trial 69. Further, a multifunctional RNA-loaded magnetic liposomes (RNA-NPs) platform was developed to initiate potent antitumor immunity and importantly, to predict the responders after vaccination with magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) 70. RNA-NPs incorporated with the T2 MRI contrast-enhancing effects of iron oxide nanoparticles can enhance DCs transfection and detect DCs migration to lymph nodes with MRI. These effects have been seen in 2 days after vaccination and the reductions of tumors were correlated with survival in murine B16F10-OVA tumor models. Recently, a combinatorial design of biodegradable polymeric DNA nanoparticles for local delivery in solid tumors has been developed 71. This platform utilizes nonviral cargo poly (beta-amino ester)s (PBAE)-based nanoparticles to deliver DNA to tumor cells expressing MHC-I and ultimately, induces expression of the co-stimulatory molecule 4-1BBL and IL-12 secretion which leads to activation of cell-mediated cytotoxic immune responses. These genetically reprogrammed tumor cells are therefore termed tumor-associated antigen-presenting cells. This approach can avoid the intrinsic immunogenicity or toxicity as commonly seen in vectors like viruses or lipid nanoparticles 71. Additionally, various nanoparticles have been utilized for developing therapeutic T cells for adoptive therapies. Please refer to a review by Yang et al. for more detailed information 59.

Combination therapy

Application of nanomedicine to develop combination therapy has been studied to improve the median survival with long-term memory responses in cancer patients who receive immunotherapy. In the clinical setting, only a fraction of patients display immune response to antitumor immunotherapy 10. Toxicities associated with ICB are a pivotal issue where the adjustment of drug ratios to optimize clinical efficacy and safety are considered 72. In addition, several studies demonstrated that treatment failure is mainly related to immune suppressive factors in the tumor microenvironment 73. Given of the ability of nanocarriers to load various anticancer drugs, it is important to consider the combination of more than one therapeutic using nanotechnology, which is a significant advantage to increase the clinical response of cancer immunotherapy. One consideration is utilizing nanocarriers to combine chemotherapeutic drugs to trigger immunogenic cell death (ICD) of cancer cells, a process that can induce immune activation. For example, combinations of doxorubicin and anti-PD1 drugs can be delivered by synthetic high-density lipoprotein (sHDL) nanodiscs which can not only reduce the off-target toxicity of chemo-drugs, but also amplify antitumor CD8+ T cell responses 74. This may be important because as seen in a recent study, there were no significant changes of posttreatment to pretreatment median CD8+TIL density ratio in OPC patients who received durvalumab (PD-L1 inhibitor) ordurvalumab plus tremelimumab (CTLA-4 inhibitor) 75. Yang et al. developed a nanovesicle platform which includes pH-responsive nanovesicles (pRNVs) self-assembled from block copolymer polyethylene glycol-b-cationic polypeptide (PEG-b-cPPT) 76. These nanovesicles can encapsulate a photosensitizer and indoximod, an indoleamine 2, 3-dioxygenase inhibitor, to improve efficient drug delivery. The dual combination can also induce reactive oxygen species (ROS) generation and ICD effects. Importantly, the recruitment of DCs was increased, the immune response was activated and the tumor microenvironment was modulated via indoximod with increased CD8+ T cell infiltration 76. Other approaches such as immunotherapy combined with photothermal therapy or photodynamic therapy or gene therapy were also reported (for a detailed overview, please refer to a review by Nam et al.) 77. Remarkably, these strategies not only improve the synthetic site-specific drug delivery but also induce robust immune activation.

Conclusions and prospections

Taking advantage of the physiochemical properties of various nanomaterials, nanotechnology-based theranostic approaches have been explored to improve transport and biodistribution of therapeutic drugs, reduce side effects and consequently, widen the therapeutic window in curative cancer treatments and other diseases 78, 79. To date, clinically available nanodrugs for cancer treatment such as Abraxance (albumin-bound paclitaxel) and Vyxeos (lioposomal daunorubicin and cytarabine) are applied in R/M HNSCC, breast, lung, and pancreatic cancer, metastatic breast cancer and high-risk acute myeloid leukemia 47, 80, 81. In addition, preclinical studies have shown that HNSCC-CSCs can be targeted through multidisciplinary nanotechnology-based approaches. Specifically, strategies to prime the tumor microenvironment in cases of recurrent or metastatic HNSCC have the potential to improve immune therapeutic outcomes. Preclinical study and clinical trials have shown the promising results of combination therapy with immunotherapy and conventional therapy 39. Thus, the therapeutic development of HNSCC can be achieved as a result of the enormous progress in nanomedicine.

Although the concept of nanoimmunotherapeutics is not too far from clinical reality, there are a number of obstacles that needed to be addressed to move preclinical findings to clinical application. For example, the pharmacokinetics, stability and circulation time of nanoimmunotherapeutics in the bloodstream, the effectiveness and the long-term safety of the delivery systems should be further investigated and the feasibility of these platforms in functional preclinical HNSCC models is necessary to advance for clinical trials. However, remodeling the tumor microenvironment remains challenge to establish in the preclinical models. Given by the heterogeneity within tumor and between individuals as discussed in previous sections, a multi-modal approach that combines engineering strategy and multiple therapeutics should be explored to augment the efficacy of immunotherapies and to improve site-specific delivery. One example is the image-guided therapeutic where nanoparticle-based immunotherapeutic platforms in combination with MRI have been employed successfully to achieve local and systemic anti-tumor effects 70. In addition, patient stratification and biomarkers that can be exploited to predict immunotherapy response are also of importance to tailor treatment. Importantly, beyond the advantage of drug-delivery systems, nanomedicine would also improve the understanding of the underlying mechanisms and contribute to cancer diagnostics 54. Notably, a recent study identified clonotypes of T cells are related to clinical responses to ICB by analyzing deep single-cell sequencing of RNA and T cell receptor repertoires in tumor tissue, adjacent normal tissue and blood. These clonotypes can also be detected in peripheral blood of responsive patients which may promote the development of rational biomarkers 82. However, it remains largely unknown for immune-excluded and immune-desert tumors.

Taken together, innovation in nanotechnology design will likely synergize the current practical approach to elicit robust treatment response and to build a deeper quantitative and conceptual understanding of cancer disease in the era of immunotherapy.

Acknowledgments

This work was partially funded by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (81702091), the Medical and the Health Science Project of Zhejiang Province (2019KY327), and Guangji Talents Foundation Award (E) of Zhejiang Cancer Hospital.

Author Contributions

X.Q contributed to conceiving the concept, wrote the first draft of the manuscript. Q. X contributed to writing parts of the manuscript and summarized tables. M.F., J.Z. and J.C. contributed to writing parts of the manuscript. H.D and L.Y. prepared the figures. X.Q., F.L., F.O., H.S., A.M.K. and A.E.A revised the manuscript. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

References

- 1.Bray F, Ferlay J, Soerjomataram I, Siegel RL, Torre LA, Jemal A. Global cancer statistics 2018: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA: a cancer journal for clinicians. 2018;68:394–424. doi: 10.3322/caac.21492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Leemans CR, Snijders PJF, Brakenhoff RH. The molecular landscape of head and neck cancer. Nature reviews Cancer. 2018;18:269–82. doi: 10.1038/nrc.2018.11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Swanson MS, Sinha UK. Rationale for combined blockade of PD-1 and CTLA-4 in advanced head and neck squamous cell cancer-review of current data. Oral oncology. 2015;51:12–5. doi: 10.1016/j.oraloncology.2014.10.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Seiwert TY, Burtness B, Mehra R, Weiss J, Berger R, Eder JP. et al. Safety and clinical activity of pembrolizumab for treatment of recurrent or metastatic squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck (KEYNOTE-012): an open-label, multicentre, phase 1b trial. The Lancet Oncology. 2016;17:956–65. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(16)30066-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Burtness B, Harrington KJ, Greil R, Soulieres D, Tahara M, de Castro G Jr. et al. Pembrolizumab alone or with chemotherapy versus cetuximab with chemotherapy for recurrent or metastatic squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck (KEYNOTE-048): a randomised, open-label, phase 3 study. Lancet. 2019;394:1915–28. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(19)32591-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cohen EEW, Soulieres D, Le Tourneau C, Dinis J, Licitra L, Ahn MJ. et al. Pembrolizumab versus methotrexate, docetaxel, or cetuximab for recurrent or metastatic head-and-neck squamous cell carcinoma (KEYNOTE-040): a randomised, open-label, phase 3 study. Lancet. 2019;393:156–67. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(18)31999-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Friedman CF, Proverbs-Singh TA, Postow MA. Treatment of the Immune-Related Adverse Effects of Immune Checkpoint Inhibitors: A Review. JAMA Oncol. 2016;2:1346–53. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2016.1051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Postow MA, Hellmann MD. Adverse Events Associated with Immune Checkpoint Blockade. The New England journal of medicine. 2018;378:1165. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc1801663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Magalhaes I, Carvalho-Queiroz C, Hartana CA, Kaiser A, Lukic A, Mints M. et al. Facing the future: challenges and opportunities in adoptive T cell therapy in cancer. Expert Opin Biol Ther. 2019;19:811–27. doi: 10.1080/14712598.2019.1608179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Qian X, Leonard F, Wenhao Y, Sudhoff H, Hoffmann TK, Ferrone S. et al. Immunotherapeutics for head and neck squamous cell carcinoma stem cells. Hno. 2020;68:94–99. doi: 10.1007/s00106-020-00819-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kok VC. Current Understanding of the Mechanisms Underlying Immune Evasion From PD-1/PD-L1 Immune Checkpoint Blockade in Head and Neck Cancer. Front Oncol. 2020;10:268. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2020.00268. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Murakami M, Cabral H, Matsumoto Y, Wu S, Kano MR, Yamori T. et al. Improving drug potency and efficacy by nanocarrier-mediated subcellular targeting. Science translational medicine. 2011;3:64ra2. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3001385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Shen H, Sun T, Hoang HH, Burchfield JS, Hamilton GF, Mittendorf EA. et al. Enhancing cancer immunotherapy through nanotechnology-mediated tumor infiltration and activation of immune cells. Semin Immunol. 2017;34:114–22. doi: 10.1016/j.smim.2017.09.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Goldberg MS. Improving cancer immunotherapy through nanotechnology. Nature reviews Cancer. 2019;19:587–602. doi: 10.1038/s41568-019-0186-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Venuta A, Wolfram J, Shen H, Ferrari M. Post-nano strategies for drug delivery: Multistage porous silicon microvectors. J Mater Chem B. 2017;5:207–19. doi: 10.1039/C6TB01978A. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Qian X, Nie X, Yao W, Klinghammer K, Sudhoff H, Kaufmann AM. et al. Reactive oxygen species in cancer stem cells of head and neck squamous cancer. Seminars in cancer biology. 2018;53:248–57. doi: 10.1016/j.semcancer.2018.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Qian X, Nie X, Wollenberg B, Sudhoff H, Kaufmann AM, Albers AE. Heterogeneity of Head and Neck Squamous Cell Carcinoma Stem Cells. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2019;1139:23–40. doi: 10.1007/978-3-030-14366-4_2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Albers AE, Strauss L, Liao T, Hoffmann TK, Kaufmann AM. T cell-tumor interaction directs the development of immunotherapies in head and neck cancer. Clin Dev Immunol. 2010;2010:236378. doi: 10.1155/2010/236378. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Qian X, Ma C, Nie X, Lu J, Lenarz M, Kaufmann AM. et al. Biology and immunology of cancer stem(-like) cells in head and neck cancer. Critical reviews in oncology/hematology. 2015;95:337–45. doi: 10.1016/j.critrevonc.2015.03.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Almangush A, Leivo I, Makitie AA. Overall assessment of tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes in head and neck squamous cell carcinoma: time to take notice. Acta Otolaryngol. 2020. p: 1-3. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 21.Chen SMY, Krinsky AL, Woolaver RA, Wang X, Chen Z, Wang JH. Tumor immune microenvironment in head and neck cancers. Molecular carcinogenesis. 2020;59:766–774. doi: 10.1002/mc.23162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chen YP, Wang YQ, Lv JW, Li YQ, Chua MLK, Le QT. et al. Identification and validation of novel microenvironment-based immune molecular subgroups of head and neck squamous cell carcinoma: implications for immunotherapy. Annals of oncology: official journal of the European Society for Medical Oncology / ESMO. 2019;30:68–75. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdy470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hegde PS, Chen DS. Top 10 Challenges in Cancer Immunotherapy. Immunity. 2020;52:17–35. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2019.12.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cramer JD, Burtness B, Ferris RL. Immunotherapy for head and neck cancer: Recent advances and future directions. Oral oncology. 2019;99:104460. doi: 10.1016/j.oraloncology.2019.104460. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Keenan TE, Burke KP, Van Allen EM. Genomic correlates of response to immune checkpoint blockade. Nature medicine. 2019;25:389–402. doi: 10.1038/s41591-019-0382-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kim MH, Kim JH, Lee JM, Choi JW, Jung D, Cho H. et al. Molecular subtypes of oropharyngeal cancer show distinct immune microenvironment related with immune checkpoint blockade response. British journal of cancer. 2020;122:1649–1660. doi: 10.1038/s41416-020-0796-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hegde PS, Karanikas V, Evers S. The Where, the When, and the How of Immune Monitoring for Cancer Immunotherapies in the Era of Checkpoint Inhibition. Clinical cancer research: an official journal of the American Association for Cancer Research. 2016;22:1865–74. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-15-1507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mariathasan S, Turley SJ, Nickles D, Castiglioni A, Yuen K, Wang Y. et al. TGFbeta attenuates tumour response to PD-L1 blockade by contributing to exclusion of T cells. Nature. 2018;554:544–8. doi: 10.1038/nature25501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Shayan G, Srivastava R, Li J, Schmitt N, Kane LP, Ferris RL. Adaptive resistance to anti-PD1 therapy by Tim-3 upregulation is mediated by the PI3K-Akt pathway in head and neck cancer. Oncoimmunology. 2017;6:e1261779. doi: 10.1080/2162402X.2016.1261779. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.LeHew CW, Weatherspoon DJ, Peterson CE, Goben A, Reitmajer K, Sroussi H. et al. The Health System and Policy Implications of Changing Epidemiology for Oral Cavity and Oropharyngeal Cancers in the United States From 1995 to 2016. Epidemiol Rev. 2017;39:132–47. doi: 10.1093/epirev/mxw001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Qian X, Nguyen DT, Dong Y, Sinikovic B, Kaufmann AM, Myers JN. et al. Prognostic Score Predicts Survival in HPV-Negative Head and Neck Squamous Cell Cancer Patients. Int J Biol Sci. 2019;15:1336–44. doi: 10.7150/ijbs.33329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lydiatt WM, Patel SG, O'Sullivan B, Brandwein MS, Ridge JA, Migliacci JC. et al. Head and Neck cancers-major changes in the American Joint Committee on cancer eighth edition cancer staging manual. CA: a cancer journal for clinicians. 2017;67:122–37. doi: 10.3322/caac.21389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wood O, Woo J, Seumois G, Savelyeva N, McCann KJ, Singh D. et al. Gene expression analysis of TIL rich HPV-driven head and neck tumors reveals a distinct B-cell signature when compared to HPV independent tumors. Oncotarget. 2016;7:56781–97. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.10788. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Cillo AR, Kurten CHL, Tabib T, Qi Z, Onkar S, Wang T. et al. Immune Landscape of Viral- and Carcinogen-Driven Head and Neck Cancer. Immunity. 2020;52:183–99. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2019.11.014. e9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Linterman MA, Hill DL. Can follicular helper T cells be targeted to improve vaccine efficacy? F1000Res. 2016. 5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 36.De Giovanni M, Cutillo V, Giladi A, Sala E, Maganuco CG, Medaglia C. et al. Spatiotemporal regulation of type I interferon expression determines the antiviral polarization of CD4(+) T cells. Nat Immunol. 2020;21:321–330. doi: 10.1038/s41590-020-0596-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ferris RL, Blumenschein G Jr, Fayette J, Guigay J, Colevas AD, Licitra L. et al. Nivolumab for Recurrent Squamous-Cell Carcinoma of the Head and Neck. The New England journal of medicine. 2016;375:1856–67. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1602252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kansy BA, Concha-Benavente F, Srivastava RM, Jie HB, Shayan G, Lei Y. et al. PD-1 Status in CD8(+) T Cells Associates with Survival and Anti-PD-1 Therapeutic Outcomes in Head and Neck Cancer. Cancer research. 2017;77:6353–64. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-16-3167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Massarelli E, William W, Johnson F, Kies M, Ferrarotto R, Guo M. et al. Combining Immune Checkpoint Blockade and Tumor-Specific Vaccine for Patients With Incurable Human Papillomavirus 16-Related Cancer: A Phase 2 Clinical Trial. JAMA Oncol. 2019;5:67–73. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2018.4051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wong XY, Sena-Torralba A, Alvarez-Diduk R, Muthoosamy K, Merkoci A. Nanomaterials for Nanotheranostics: Tuning Their Properties According to Disease Needs. ACS Nano. 2020;14:2585–627. doi: 10.1021/acsnano.9b08133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Zhuang J, Kuo CH, Chou LY, Liu DY, Weerapana E, Tsung CK. Optimized metal-organic-framework nanospheres for drug delivery: evaluation of small-molecule encapsulation. ACS Nano. 2014;8:2812–9. doi: 10.1021/nn406590q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wolfram J, Ferrari M. Clinical Cancer Nanomedicine. Nano Today. 2019;25:85–98. doi: 10.1016/j.nantod.2019.02.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Makino J, Cabral H, Miura Y, Matsumoto Y, Wang M, Kinoh H. et al. cRGD-installed polymeric micelles loading platinum anticancer drugs enable cooperative treatment against lymph node metastasis. J Control Release. 2015;220:783–91. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2015.10.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Miyano K, Cabral H, Miura Y, Matsumoto Y, Mochida Y, Kinoh H. et al. cRGD peptide installation on cisplatin-loaded nanomedicines enhances efficacy against locally advanced head and neck squamous cell carcinoma bearing cancer stem-like cells. J Control Release. 2017;261:275–86. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2017.06.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Zhao H, Feng H, Liu D, Liu J, Ji N, Chen F. et al. Self-Assembling Monomeric Nucleoside Molecular Nanoparticles Loaded with 5-FU Enhancing Therapeutic Efficacy against Oral Cancer. ACS Nano. 2015;9:9638–51. doi: 10.1021/acsnano.5b04520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Mohan A, Narayanan S, Balasubramanian G, Sethuraman S, Krishnan UM. Dual drug loaded nanoliposomal chemotherapy: A promising strategy for treatment of head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. Eur J Pharm Biopharm. 2016;99:73–83. doi: 10.1016/j.ejpb.2015.11.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Chun SG, Hughes R, Sumer BD, Myers LL, Truelson JM, Khan SA. et al. A Phase I/II Study of Nab-Paclitaxel, Cisplatin, and Cetuximab With Concurrent Radiation Therapy for Locally Advanced Squamous Cell Cancer of the Head and Neck. Cancer Invest. 2017;35:23–31. doi: 10.1080/07357907.2016.1213275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Mi Y, Smith CC, Yang F, Qi Y, Roche KC, Serody JS. et al. A Dual Immunotherapy Nanoparticle Improves T-Cell Activation and Cancer Immunotherapy. Adv Mater. 2018;30:e1706098. doi: 10.1002/adma.201706098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Pauthner M, Yeung J, Ullman C, Bakker J, Wurch T, Reichert JM. et al. Antibody Engineering & Therapeutics, the annual meeting of The Antibody Society December 7-10, 2015, San Diego, CA, USA. MAbs. 2016;8:617–52. doi: 10.1080/19420862.2016.1153211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Schmid D, Park CG, Hartl CA, Subedi N, Cartwright AN, Puerto RB. et al. T cell-targeting nanoparticles focus delivery of immunotherapy to improve antitumor immunity. Nature communications. 2017;8:1747. doi: 10.1038/s41467-017-01830-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Ou W, Thapa RK, Jiang L, Soe ZC, Gautam M, Chang JH. et al. Regulatory T cell-targeted hybrid nanoparticles combined with immuno-checkpoint blockage for cancer immunotherapy. J Control Release. 2018;281:84–96. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2018.05.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Zhang F, Stephan SB, Ene CI, Smith TT, Holland EC, Stephan MT. Nanoparticles That Reshape the Tumor Milieu Create a Therapeutic Window for Effective T-cell Therapy in Solid Malignancies. Cancer research. 2018;78:3718–30. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-18-0306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Zhang F, Parayath NN, Ene CI, Stephan SB, Koehne AL, Coon ME. et al. Genetic programming of macrophages to perform anti-tumor functions using targeted mRNA nanocarriers. Nature communications. 2019;10:3974. doi: 10.1038/s41467-019-11911-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Leonard F, Curtis LT, Hamed AR, Zhang C, Chau E, Sieving D. et al. Nonlinear response to cancer nanotherapy due to macrophage interactions revealed by mathematical modeling and evaluated in a murine model via CRISPR-modulated macrophage polarization. Cancer Immunol Immunother. 2020;69:731–744. doi: 10.1007/s00262-020-02504-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Schuler PJ, Harasymczuk M, Visus C, Deleo A, Trivedi S, Lei Y. et al. Phase I dendritic cell p53 peptide vaccine for head and neck cancer. Clinical cancer research: an official journal of the American Association for Cancer Research. 2014;20:2433–44. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-13-2617. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.van Poelgeest MI, Welters MJ, Vermeij R, Stynenbosch LF, Loof NM, Berends-van der Meer DM. et al. Vaccination against Oncoproteins of HPV16 for Noninvasive Vulvar/Vaginal Lesions: Lesion Clearance Is Related to the Strength of the T-Cell Response. Clinical cancer research: an official journal of the American Association for Cancer Research. 2016;22:2342–50. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-15-2594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Wefers C, Schreibelt G, Massuger L, de Vries IJM, Torensma R. Immune Curbing of Cancer Stem Cells by CTLs Directed to NANOG. Front Immunol. 2018;9:1412. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2018.01412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Grippin AJ, Sayour EJ, Mitchell DA. Translational nanoparticle engineering for cancer vaccines. Oncoimmunology. 2017;6:e1290036. doi: 10.1080/2162402X.2017.1290036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Yang WJ, Zhou LJ, Lau J, Hu S, Chen XY. Functional T cell activation by smart nanosystems for effective cancer immunotherapy. Nano Today. 2019;27:28–47. [Google Scholar]

- 60.Grunwitz C, Salomon N, Vascotto F, Selmi A, Bukur T, Diken M. et al. HPV16 RNA-LPX vaccine mediates complete regression of aggressively growing HPV-positive mouse tumors and establishes protective T cell memory. Oncoimmunology. 2019;8:e1629259. doi: 10.1080/2162402X.2019.1629259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Liu L, Wang Y, Miao L, Liu Q, Musetti S, Li J. et al. Combination Immunotherapy of MUC1 mRNA Nano-vaccine and CTLA-4 Blockade Effectively Inhibits Growth of Triple Negative Breast Cancer. Molecular therapy: the journal of the American Society of Gene Therapy. 2018;26:45–55. doi: 10.1016/j.ymthe.2017.10.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Mei Z, Zhang K, Lam AK, Huang J, Qiu F, Qiao B. et al. MUC1 as a target for CAR-T therapy in head and neck squamous cell carinoma. Cancer medicine. 2020;9:640–52. doi: 10.1002/cam4.2733. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Liu WL, Zou MZ, Liu T, Zeng JY, Li X, Yu WY. et al. Cytomembrane nanovaccines show therapeutic effects by mimicking tumor cells and antigen presenting cells. Nature communications. 2019;10:3199. doi: 10.1038/s41467-019-11157-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Weise JB, Maune S, Gorogh T, Kabelitz D, Arnold N, Pfisterer J. et al. A dendritic cell based hybrid cell vaccine generated by electrofusion for immunotherapy strategies in HNSCC. Auris Nasus Larynx. 2004;31:149–53. doi: 10.1016/j.anl.2004.01.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Tan YS, Sansanaphongpricha K, Xie Y, Donnelly CR, Luo X, Heath BR. et al. Mitigating SOX2-potentiated Immune Escape of Head and Neck Squamous Cell Carcinoma with a STING-inducing Nanosatellite Vaccine. Clin Cancer Res. 2018;24:4242–55. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-17-2807. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Luo M, Wang H, Wang Z, Cai H, Lu Z, Li Y. et al. A STING-activating nanovaccine for cancer immunotherapy. Nat Nanotechnol. 2017;12:648–54. doi: 10.1038/nnano.2017.52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Gandhapudi SK, Ward M, Bush JPC, Bedu-Addo F, Conn G, Woodward JG. Antigen Priming with Enantiospecific Cationic Lipid Nanoparticles Induces Potent Antitumor CTL Responses through Novel Induction of a Type I IFN Response. J Immunol. 2019;202:3524–36. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1801634. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Neelapu SS, Baskar S, Gause BL, Kobrin CB, Watson TM, Frye AR. et al. Human autologous tumor-specific T-cell responses induced by liposomal delivery of a lymphoma antigen. Clinical cancer research: an official journal of the American Association for Cancer Research. 2004;10:8309–17. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-04-1071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Kranz LM, Diken M, Haas H, Kreiter S, Loquai C, Reuter KC. et al. Systemic RNA delivery to dendritic cells exploits antiviral defence for cancer immunotherapy. Nature. 2016;534:396–401. doi: 10.1038/nature18300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Grippin AJ, Wummer B, Wildes T, Dyson K, Trivedi V, Yang C. et al. Dendritic Cell-Activating Magnetic Nanoparticles Enable Early Prediction of Antitumor Response with Magnetic Resonance Imaging. ACS Nano. 2019;13:13884–98. doi: 10.1021/acsnano.9b05037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Tzeng SY, Patel KK, Wilson DR, Meyer RA, Rhodes KR, Green JJ. In situ genetic engineering of tumors for long-lasting and systemic immunotherapy. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2020;117:4043–4052. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1916039117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Naidoo J, Page DB, Li BT, Connell LC, Schindler K, Lacouture ME. et al. Toxicities of the anti-PD-1 and anti-PD-L1 immune checkpoint antibodies. Annals of oncology: official journal of the European Society for Medical Oncology / ESMO. 2015;26:2375–91. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdv383. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Phuengkham H, Ren L, Shin IW, Lim YT. Nanoengineered Immune Niches for Reprogramming the Immunosuppressive Tumor Microenvironment and Enhancing Cancer Immunotherapy. Adv Mater. 2019;31:e1803322. doi: 10.1002/adma.201803322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Kuai R, Yuan W, Son S, Nam J, Xu Y, Fan Y. et al. Elimination of established tumors with nanodisc-based combination chemoimmunotherapy. Sci Adv. 2018;4:eaao1736. doi: 10.1126/sciadv.aao1736. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Ferrarotto R, Bell D, Rubin ML, Hutcheson KA, Johnson JM, Goepfert RP, Impact of neoadjuvant durvalumab with or without tremelimumab on CD8+ tumor lymphocyte density, safety, and efficacy in patients with oropharynx cancer: CIAO trial. Clinical cancer research: an official journal of the American Association for Cancer Research. 2020. 10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 76.Yang W, Zhang F, Deng H, Lin L, Wang S, Kang F. et al. Smart Nanovesicle-Mediated Immunogenic Cell Death through Tumor Microenvironment Modulation for Effective Photodynamic Immunotherapy. ACS Nano. 2019;14:620–631. doi: 10.1021/acsnano.9b07212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Nam J, Son S, Park KS, Zou WP, Shea LD, Moon JJ. Cancer nanomedicine for combination cancer immunotherapy. Nat Rev Mater. 2019;4:398–414. [Google Scholar]

- 78.Fabbri J, Espinosa JP, Pensel PE, Medici SK, Gamboa GU, Benoit JP. et al. Do albendazole-loaded lipid nanocapsules enhance the bioavailability of albendazole in the brain of healthy mice? Acta Trop. 2020;201:105215. doi: 10.1016/j.actatropica.2019.105215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Leal J, Peng X, Liu X, Arasappan D, Wylie DC, Schwartz SH. et al. Peptides as surface coatings of nanoparticles that penetrate human cystic fibrosis sputum and uniformly distribute in vivo following pulmonary delivery. J Control Release. 2020;322:457–469. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2020.03.032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Shi J, Kantoff PW, Wooster R, Farokhzad OC. Cancer nanomedicine: progress, challenges and opportunities. Nature reviews Cancer. 2017;17:20–37. doi: 10.1038/nrc.2016.108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Adkins D, Ley J, Michel L, Wildes TM, Thorstad W, Gay HA. et al. nab-Paclitaxel, cisplatin, and 5-fluorouracil followed by concurrent cisplatin and radiation for head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. Oral oncology. 2016;61:1–7. doi: 10.1016/j.oraloncology.2016.07.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Wu TD, Madireddi S, de Almeida PE, Banchereau R, Chen YJ, Chitre AS. et al. Peripheral T cell expansion predicts tumour infiltration and clinical response. Nature. 2020;579:274–278. doi: 10.1038/s41586-020-2056-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Leach DG, Dharmaraj N, Piotrowski SL, Lopez-Silva TL, Lei YL, Sikora AG. et al. STINGel: Controlled release of a cyclic dinucleotide for enhanced cancer immunotherapy. Biomaterials. 2018;163:67–75. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2018.01.035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Lin SJ, Chin YT, Ho Y, Chou SY, Sh Yang YC, Nana AW. et al. Nano-diamino-tetrac (NDAT) inhibits PD-L1 expression which is essential for proliferation in oral cancer cells. Food Chem Toxicol. 2018;120:1–11. doi: 10.1016/j.fct.2018.06.058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Lu R, Groer C, Kleindl PA, Moulder KR, Huang A, Hunt JR. et al. Formulation and preclinical evaluation of a toll-like receptor 7/8 agonist as an anti-tumoral immunomodulator. J Control Release. 2019;306:165–76. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2019.06.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Lu K, He C, Guo N, Chan C, Ni K, Lan G. et al. Low-dose X-ray radiotherapy-radiodynamic therapy via nanoscale metal-organic frameworks enhances checkpoint blockade immunotherapy. Nat Biomed Eng. 2018;2:600–10. doi: 10.1038/s41551-018-0203-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Nam J, Son S, Ochyl LJ, Kuai R, Schwendeman A, Moon JJ. Chemo-photothermal therapy combination elicits anti-tumor immunity against advanced metastatic cancer. Nat Commun. 2018;9:1074. doi: 10.1038/s41467-018-03473-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Xian J, Yang H, Lin Y, Liu S. Combination nonviral murine interleukin 2 and interleukin 12 gene therapy and radiotherapy for head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. 2005; 131: 1079-85. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 89.Zhang L, Jing D, Wang L, Sun Y, Li JJ, Hill B. et al. Unique Photochemo-Immuno-Nanoplatform against Orthotopic Xenograft Oral Cancer and Metastatic Syngeneic Breast Cancer. Nano Lett. 2018;18:7092–103. doi: 10.1021/acs.nanolett.8b03096. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Espinosa-Cotton M, Rodman Iii SN, Ross KA, Jensen IJ, Sangodeyi-Miller K, McLaren AJ. et al. Interleukin-1 alpha increases anti-tumor efficacy of cetuximab in head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. J Immunother Cancer. 2019;7:79. doi: 10.1186/s40425-019-0550-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Da Silva CG, Camps MGM, Li T, Zerrillo L, Lowik CW, Ossendorp F. et al. Effective chemoimmunotherapy by co-delivery of doxorubicin and immune adjuvants in biodegradable nanoparticles. Theranostics. 2019;9:6485–500. doi: 10.7150/thno.34429. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Ishii KJ, Kawakami K, Gursel I, Conover J, Joshi BH, Klinman DM. et al. Antitumor therapy with bacterial DNA and toxin: complete regression of established tumor induced by liposomal CpG oligodeoxynucleotides plus interleukin-13 cytotoxin. Clinical cancer rsearch. 2003;9:6516–22. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Luo M, Liu Z, Zhang X, Han C, Samandi LZ, Dong C, Synergistic STING activation by PC7A nanovaccine and ionizing radiation improves cancer immunotherapy. 2019; 300: 154-60. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 94.Galliverti G, Tichet M, Domingos-Pereira S, Hauert S, Nardelli-Haefliger D, Swartz MA. et al. Nanoparticle Conjugation of Human Papillomavirus 16 E7-long Peptides Enhances Therapeutic Vaccine Efficacy against Solid Tumors in Mice. Cancer Immunol Res. 2018;6:1301–13. doi: 10.1158/2326-6066.CIR-18-0166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Han HD, Byeon Y, Kang TH, Jung ID, Lee JW, Shin BC. et al. Toll-like receptor 3-induced immune response by poly(d,l-lactide-co-glycolide) nanoparticles for dendritic cell-based cancer immunotherapy. Int J Nanomedicine. 2016;11:5729–42. doi: 10.2147/IJN.S109001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Ilyinskii PO, Kovalev GI, O'Neil CP, Roy CJ, Michaud AM, Drefs NM. et al. Synthetic vaccine particles for durable cytolytic T lymphocyte responses and anti-tumor immunotherapy. PLoS One. 2018;13:e0197694. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0197694. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Kuai R, Sun X, Yuan W, Ochyl LJ, Xu Y, Hassani Najafabadi A. et al. Dual TLR agonist nanodiscs as a strong adjuvant system for vaccines and immunotherapy. J Control Release. 2018;282:131–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2018.04.041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Kwong B, Gai SA, Elkhader J, Wittrup KD, Irvine DJ. Localized immunotherapy via liposome-anchored Anti-CD137 + IL-2 prevents lethal toxicity and elicits local and systemic antitumor immunity. Cancer Res. 2013;73:1547–58. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-12-3343. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Li AW, Sobral MC, Badrinath S, Choi Y, Graveline A, Stafford AG. et al. A facile approach to enhance antigen response for personalized cancer vaccination. Nat Mater. 2018;17:528–34. doi: 10.1038/s41563-018-0028-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Li S, Zhang Q, Bai H, Huang W, Shu C, Ye C. et al. Self-Assembled Nanofibers Elicit Potent HPV16 E7-Specific Cellular Immunity And Abolish Established TC-1 Graft Tumor. Int J Nanomedicine. 2019;14:8209–19. doi: 10.2147/IJN.S214525. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Liu C, Chu X, Yan M, Qi J, Liu H, Gao F. et al. Encapsulation of Poly I:C and the natural phosphodiester CpG ODN enhanced the efficacy of a hyaluronic acid-modified cationic lipid-PLGA hybrid nanoparticle vaccine in TC-1-grafted tumors. Int J Pharm. 2018;553:327–37. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpharm.2018.10.054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Miao L, Li L, Huang Y, Delcassian D, Chahal J, Han J. et al. Delivery of mRNA vaccines with heterocyclic lipids increases anti-tumor efficacy by STING-mediated immune cell activation. Nature biotechnology. 2019;37:1174–85. doi: 10.1038/s41587-019-0247-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Motevalli F, Bolhassani A, Hesami S, Shahbazi S. Supercharged green fluorescent protein delivers HPV16E7 DNA and protein into mammalian cells in vitro and in vivo. Immunol Lett. 2018;194:29–39. doi: 10.1016/j.imlet.2017.12.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Rosalia RA, Cruz LJ, van Duikeren S, Tromp AT, Silva AL, Jiskoot W. et al. CD40-targeted dendritic cell delivery of PLGA-nanoparticle vaccines induce potent anti-tumor responses. Biomaterials. 2015;40:88–97. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2014.10.053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Shin JM, Song SH, Vijayakameswara Rao N, Lee ES, Ko H, Park JH. A carboxymethyl dextran-based polymeric conjugate as the antigen carrier for cancer immunotherapy. Biomaterials Research. 2018;22:21. doi: 10.1186/s40824-018-0131-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Tang J, Yin R, Tian Y, Huang Z, Shi J, Fu X. et al. A novel self-assembled nanoparticle vaccine with HIV-1 Tat(4)(9)(-)(5)(7)/HPV16 E7(4)(9)(-)(5)(7) fusion peptide and GM-CSF DNA elicits potent and prolonged CD8(+) T cell-dependent anti-tumor immunity in mice. Vaccine. 2012;30:1071–82. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2011.12.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Wang L, Wang Z, Qin Y, Liang W. Delivered antigen peptides to resident CD8alpha(+) DCs in lymph node by micelle-based vaccine augment antigen-specific CD8(+) effector T cell response. Eur J Pharm Biopharm. 2020;147:76–86. doi: 10.1016/j.ejpb.2019.12.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Wang S, Huang W, Li K, Yao Y, Yang X, Bai H. et al. Engineered outer membrane vesicle is potent to elicit HPV16E7-specific cellular immunity in a mouse model of TC-1 graft tumor. Int J Nanomedicine. 2017;12:6813–25. doi: 10.2147/IJN.S143264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Prasad S, Cody V, Saucier-Sawyer JK, Fadel TR, Edelson RL, Birchall MA. et al. Optimization of stability, encapsulation, release, and cross-priming of tumor antigen-containing PLGA nanoparticles. Pharm Res. 2012;29:2565–77. doi: 10.1007/s11095-012-0787-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Su H, Luo Q, Xie H, Huang X, Ni Y, Mou Y. et al. Therapeutic antitumor efficacy of tumor-derived autophagosome (DRibble) vaccine on head and neck cancer. Int J Nanomedicine. 2015;10:1921–30. doi: 10.2147/IJN.S74204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Tyagi RK, Parmar R, Patel N. A generic RNA pulsed DC based approach for developing therapeutic intervention against nasopharyngeal carcinoma. Hum Vaccin Immunother. 2017;13:854–66. doi: 10.1080/21645515.2016.1256518. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Avila LA, Aps L, Ploscariu N, Sukthankar P, Guo R, Wilkinson KE. et al. Gene delivery and immunomodulatory effects of plasmid DNA associated with Branched Amphiphilic Peptide Capsules. J Control Release. 2016;241:15–24. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2016.08.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Chu X, Li Y, Long Q, Xia Y, Yao Y, Sun W. et al. Chimeric HBcAg virus-like particles presenting a HPV 16 E7 epitope significantly suppressed tumor progression through preventive or therapeutic immunization in a TC-1-grafted mouse model. Int J Nanomedicine. 2016;11:2417–29. doi: 10.2147/IJN.S102467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Cui Z, Han SJ, Vangasseri DP, Huang L. Immunostimulation mechanism of LPD nanoparticle as a vaccine carrier. 2005; 2: 22-8. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 115.Maiyo F, Singh M. Folate-Targeted mRNA Delivery Using Chitosan-Functionalized Selenium Nanoparticles: Potential in Cancer Immunotherapy. Pharmaceuticals (Basel) 2019;12:164. doi: 10.3390/ph12040164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Chattopadhyay S, Dash SK, Ghosh T, Das S, Tripathy S, Mandal D. et al. Anticancer and immunostimulatory role of encapsulated tumor antigen containing cobalt oxide nanoparticles. J Biol Inorg Chem. 2013;18:957–73. doi: 10.1007/s00775-013-1044-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Dharmaraj N, Piotrowski SL, Huang C, Newton JM, Golfman LS, Hanoteau A. et al. Anti-tumor immunity induced by ectopic expression of viral antigens is transient and limited by immune escape. Oncoimmunology. 2019;8:e1568809. doi: 10.1080/2162402X.2019.1568809. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]