Abstract

Sudden cardiac arrest remains an unexpected and dynamic cardiovascular disease process that continues to present challenges for accurate risk prediction and prevention. The notion of a circadian pattern in the occurrence of sudden cardiac arrest had long been supported by the presence of an early morning peak; however, more recent studies are calling this observation into question. This likely paradigm shift in the presentation and mechanisms of sudden cardiac arrest has major implications and needs to be carefully considered. In this review, we present the current state of the science of circadian and septadian trends in sudden cardiac arrest through an in-depth analysis of the published literature.

Background

Despite significant advances in our understanding of heart disease treatment and prevention, sudden cardiac arrest is still responsible for 50% of all cardiovascular deaths, accounting for an estimated 370,000 deaths in the U.S. alone (1). And according to the CARES registry, the overall survival rate in out-of-hospital cardiac arrest in the United States is in the range of 10%, even in the presence of first responder systems (2). Whether or not peak times exist for sudden cardiac arrest has long been an important issue, with major clinical and research implications (Fig. 1). Though early studies have suggested an association between sudden cardiac arrest and circadian/septadian rhythm, similar to that exhibited in non-fatal MI, more recent studies have brought this previously accepted dogma into question. Ongoing population-based and pathologic studies continue to investigate improved methods to identify at-risk individuals; however, the dynamic nature of this disease process presents unique challenges that require a deeper understanding of time trends in the occurrence of sudden cardiac arrest. In this review, we present the current state of the science of circadian and septadian trends in sudden cardiac arrest through an in-depth analysis of the published literature.

Figure 1:

The implications of a loss of the circadian variation in sudden cardiac arrest.

Lethal arrhythmias are the most common cause of sudden cardiac death, and though the majority of these deaths are due to ischemia and coronary artery disease, many deaths occur suddenly in apparently healthy individuals. Population risk can differ from individual risk, making prediction of sudden cardiac arrest more challenging than simply identifying those with risk factors for coronary artery disease or other heart disease (1). The public health implications also remain substantial as the mean age of those affected by sudden cardiac arrest is usually in the mid-60s, which is 10–15 years less than the average life expectancy in the U.S. Over the years, the circadian trends identified for sudden cardiac arrest have been attributed to several physiologic parameters within the cardiovascular system – heart rate, blood pressure, QT interval, and ventricular effective refractory period (3). In addition, cortisol levels, catecholamine levels, vascular tone, and platelet aggregation have also been implicated in exhibiting biorhythmic fluctuation (4–6). Murine models have shown that abnormalities in myocardial repolarization and the related increase in vulnerability to ventricular arrhythmias have been associated to circadian rhythm patterns, and this has lent to further understanding of circadian variation in sudden cardiac death in humans (3). A shift away from a previously accepted relationship between sudden cardiac arrest and predictable circadian, septadian, and seasonal patterns is important. It would implore the need for further research and population-based studies on how and why this shift has occurred and if it has led to any improvements in our treatment or prevention of the disease process itself.

In order to better understand this topic, the terms sudden cardiac arrest and sudden cardiac death are important to define. Sudden cardiac arrest is the abrupt cessation of cardiac mechanical activity and the absence of signs of circulation, and access to emergency medical response data is required for this definition (2). Sudden cardiac death is the result of unsuccessful attempts to restore circulation for sudden cardiac arrest. It has also been defined as a natural and unexpected death from cardiac causes that occurs with a sudden loss of consciousness within an hour of an acute change in cardiovascular status, or if unwitnessed, within 24 h of being observed in apparently good health (1, 7). Given the major differences in the nature and etiology between out-of-hospital and in-hospital sudden cardiac arrest, for the purpose of this review, we shall be referring exclusively to the former condition. Sudden cardiac arrest can present with a spectrum of lethal arrhythmias including ventricular tachycardia, ventricular fibrillation, pulseless electrical activity, or asystole. The presenting rhythm has a great impact on the overall prognosis and survival to hospital discharge (1). Overall, the prevalence of ventricular fibrillation-related sudden death events is decreasing, while the more common presenting rhythm is pulseless electrical activity. This may be attributable to consistent findings of improved resuscitation rates and improvement in prevention and treatment of coronary artery disease (8). This increase in pulseless electrical activity may potentially help to explain the loss of a circadian rhythm in sudden cardiac arrest, but this phenomenon has not been evaluated in research studies.

Circadian Rhythm and Sudden Cardiac Arrest

In 1987, Muller and his colleagues published a retrospective study of the death certificates of 2203 patients in Massachusetts who died outside of the hospital in 1983 (9). They found a circadian variation in sudden cardiac death with two peaks during 24 h – the primary peak occurred from 7am to 11am and a secondary peak occurred between 5pm to 6pm. These results corresponded with the findings of the MILIS Study Group in 1985 that described the onset of acute myocardial infarction as following a circadian rhythm with a peak from 6am to noon (10). Also in 1987, Willich et al. showed that the incidence of sudden cardiac death peaked between 7am and 9am in 429 patients (11). Retrospective analysis of the Beta Blocker Heart Attack Trial in 1989 showed that in 101 patients, sudden cardiac death peaks mid-morning, and beta blockers were effective in preventing or blunting this phenomenon (12). In another study by Willich and colleagues in 1992, the likelihood of sudden cardiac death was found to be higher in the initial 3 h post-awakening (13). In another large retrospective study, the City of Houston Emergency Medical Services reports were examined in 1992 and showed that in 1019 individuals, the frequency of out of hospital cardiac arrest is increased between 6am and noon (14). Other studies conducted in a similar time frame have corroborated these findings, reporting that the frequency of sudden cardiac death also is increased between 6am and noon (15–17).

Because many of the original studies of the patterns of cardiac arrhythmias had been limited to the use of 24-hour ambulatory monitors, the development of implantable cardioverter-defibrillator (ICD) technology and data storage allowed for the examination of long-term continuous heart rate and arrhythmia monitoring. In the first study performed using ICD data, Lampert et al. showed that in 32 patients with coronary artery disease, sustained recurrent ventricular tachycardia displayed peak frequency in the morning, similar to what had been seen with sudden cardiac death (18). However, in another study by Wood et al., 43 patients with ICDs (81% with known coronary artery disease) and recorded tachyarrhythmias were followed for an average of 7.5 months, and they showed that the peak tachycardia frequency occurred between noon and 5pm. They also noted that this circadian variation was absent in patients on antiarrhythmic therapy (19). In a larger study by Tofler and colleagues of 483 individuals with Ventak PRx ICDs and a total of 1217 episodes of ventricular tachycardia, the incidence of ventricular tachycardia appeared to peak between 9am and noon with a nadir during the night (3 am to 6 am), which coincided with earlier findings from Lampert et al. (20). Mallavarapu et al. also analyzed the incidence and timing of ventricular arrhythmias in 390 patients with ischemic heart disease and found 2692 episodes of ventricular arrhythmias that followed a circadian pattern, with the highest incidence of ventricular arrhythmias occurring between 10am and 11am and a nadir between 2am and 3am (21). In both these later studies, circadian patterns were present irrespective of sex, age or left ventricular function.

The similarity in peak frequency of ventricular arrhythmias, sudden death, and myocardial infarction in these studies alludes to an ischemic basis for the mechanism of sudden cardiac arrest, suggesting that patients with non-ischemic heart disease should not have a circadian variation in their incidence of ventricular arrhythmias. However, in a study conducted by Englund and colleagues, 310 patients – 204 with ischemic heart disease and 106 with non-ischemic heart disease – and their ventricular arrhythmia data from their ICDs were studied (22). Of 1061 ventricular arrhythmia episodes that were recorded (682 in ischemic heart disease group and 379 in non-ischemic heart disease group), a typical circadian pattern was noted with a primary morning peak (7am to 10am) and secondary afternoon peak with nadir between 3am to 4am. Most importantly, there was no significant difference between the two groups. This suggested that the mechanism for ventricular tachycardia and possibly sudden cardiac arrest may occur in a circadian pattern regardless of the underlying heart disease.

Septadian and Seasonal Variation of Sudden Cardiac Arrest

In addition to a strong diurnal association with sudden cardiac arrest, other studies have shown that there also may be a weekly and seasonal variation, as that seen in prior studies with acute myocardial infarction (23). Arntz et al. analyzed EMS data in West Berlin from 1987 to 1991 of 24,061 sudden deaths, and they found robust circadian, septadian, and seasonal variation for sudden cardiac death (24). The nadir of events occurred between midnight and 6am, with a peak in sudden death between 6am and 12pm on essentially every day of the week. As reported in other studies, the primary peak occurred between 9am and 12pm, and a minor secondary peak in the late afternoon. They also found that most events occurred on Mondays with the least events occurring on Sundays, especially in patients < 65 years of age. Lastly, they noted that sudden cardiac death tends to peak in the winter (December – February) and is the lowest during the summer months (June – August). Peters et al. also examined the effects of circadian and septadian rhythms on ICD shocks in 683 patients with Guidant Ventak PRx ICDs (25, 26). They found a prominent peak in occurrence of ventricular arrhythmias on Monday, with a midweek decline and a secondary peak later in the week, while there was a nadir during the weekend. Interestingly, this pattern was not seen in patients receiving beta blockers. They later noted that there appeared to be a broad peak in the incidence of ICD shocks between 9am and 6pm with a noticeable nadir between 9pm and 6am. The daily diurnal variation appeared to be consistent throughout the week, but there were twice as many ICD firings on Mondays as compared with Saturdays. This Monday peak has traditionally been attributed to the stressors associated with the start of a new work week. In a more recent study of the Veterans Affairs National Cardiac Device Surveillance database, 763 ischemic and non-ischemic cardiomyopathy patients with ICDs and ventricular tachyarrhythmias were analyzed between 2005 and 2017 (27). In addition to demonstrating a predominant afternoon peak, the incidence of ventricular arrhythmias also displayed a septadian pattern with a marked reduction in the frequency of ventricular arrhythmias on Saturday and Sunday. However, this study also did not identify the classic morning or Monday peaks in ventricular tachyarrhythmias that have been reported in previous analyses.

Loss of Circadian and Septadian Variation in Sudden Cardiac Arrest

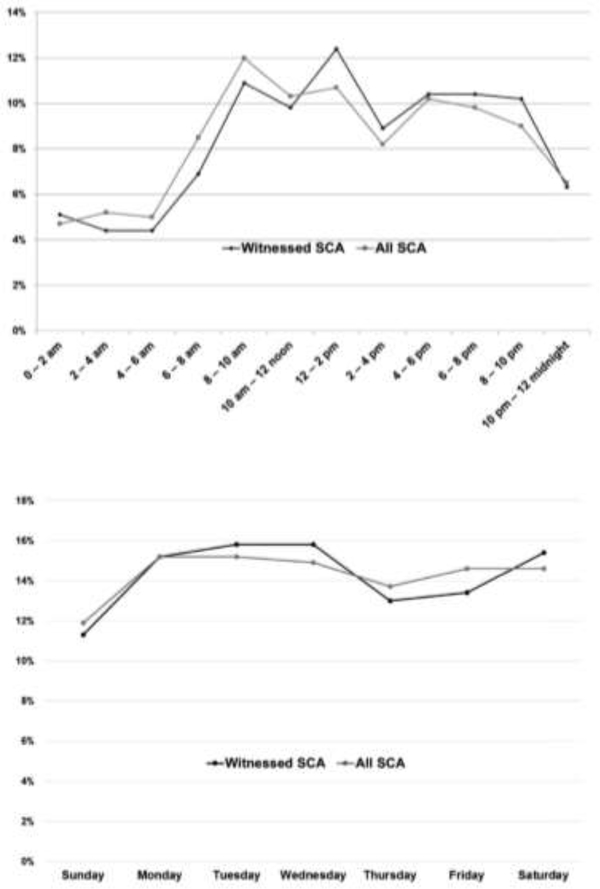

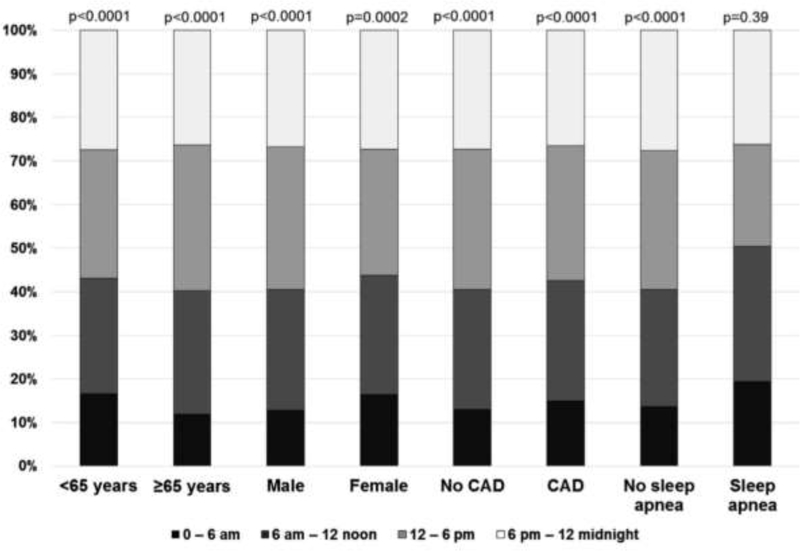

In contrast to the earlier studies described above, which appeared to show a trend toward biorhythmic variation in sudden cardiac arrest in both ischemic and non-ischemic cardiomyopathy patients, post-hoc analysis of 186 patients in the SCD-HeFT study who experienced ICD therapies for life-threatening recurrent ventricular arrhythmias yielded very different results (28). This study reported an absence of circadian or septadian patterns. The expected peak in ICD therapies in the early morning was not observed, and there was no increase in ICD therapies on Mondays. However, an early morning nadir was noted in the entire cohort as in prior studies, and there was an increased rate of ventricular arrhythmias on Mondays in the subgroup not on beta blocker therapy. A subgroup analysis showed that ischemic patients, NYHA Class II heart failure patients, and younger patients had a more prominent early morning nadir. Most recently, circadian and septadian variation of sudden cardiac arrest were evaluated in the community setting and showed very similar results. The Oregon Sudden Unexpected Death Study reported a similar deviation from previously published data on circadian and septadian patterns and sudden cardiac arrest in a population-based study, of which at least 50% of patients had normal left ventricular ejection fraction prior to their cardiac arrest event (29). Between 2002 and 2014, 1535 patients were identified with accurately timed (based on 911 calls to EMS and first EMS contact) and witnessed sudden cardiac arrests. They identified no morning peak, but there was an early morning nadir between 12am and 6am as noted in prior studies (Fig. 2). Interestingly, no circadian differences were observed in patients with sleep apnea (Fig. 3). Additionally, there was no Monday peak, but a nadir in sudden cardiac arrest was observed on Sundays. It is important to recognize that the loss of circadian and septadian variation in SCD has been reported only by the two most recent studies. The first of these, the SCD-Heft sub-study (28) may be limited by the relatively small sample size. A potential limitation of the more recent Oregon Sudden Unexpected Death Study analysis (29) could be the innate bias of witnessed cardiac arrests (and consequent 911 calls) occurring less frequently at night compared to the daytime. However, this would not affect the findings of daytime loss of the morning peak that was observed both in the subset of witnessed cardiac arrest as well as the overall group.

Figure 2:

Circadian and septadian patterns in sudden cardiac arrest as evaluated by proportions of events occurring during 2-hour intervals and on each day of the week. The expected SCA peak during the morning hours and on Mondays was absent. A new nadir was seen on Sunday. There were no significant differences in the subgroup of SCA events witnessed by bystanders or emergency medical response personnel compared to the overall SCA events. SCA = sudden cardiac arrest. (Modified from Ni et al. Shift in sudden cardiac arrest. Heart Rhythm. 2019)

Figure 3:

Proportions of sudden cardiac arrest occurrence in specific subgroups of individuals based on time of day. (Modified from Ni et al. Shift in sudden cardiac arrest. Heart Rhythm. 2019)

A Paradigm Shift

This change in the previously accepted dogma of circadian and septadian patterns of ventricular arrhythmias and sudden cardiac arrest has major public health implications and raises important questions about how and why this unexpected shift has occurred. In order to explain the differences noted in the SCD-HeFT substudy, Patton et al. suggested that the lower mean EF of 20% compared to prior studies may have resulted in other pathways of autonomic dysregulation, thereby affecting expected biorhythmic patterns (28). Moreover, the study was conducted in patients with primary prevention ICDs whereas previous studies were mainly performed in patients with secondary prevention ICDs. Whether or not the lack of daily or weekly patterns noted in the primary prevention ICD subset can be generalized to the population at risk for sudden cardiac arrest and sudden cardiac death remains unclear, but the Oregon Sudden Unexpected Death Study findings do corroborate these results.

Since the earlier studies of circadian rhythm were performed, there has been widespread implementation of guideline-directed medical therapy for heart failure with beta blockers, angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors, and angiotension receptor blockers. The addition of these medications and their combined effects on neurohormonal suppression, reverse remodeling, and vasodilation contribute to a decrease in overall sympathetic nervous system activity, which may at least in part explain the loss of circadian variation reported by the two most recent studies. Both the beta blocker heart attack trial and a substudy of the ICD trial by Wood et al. showed that there was a blunting in the circadian patterns of sudden cardiac arrest in patients on beta blockers and anti-arrhythmic therapies, which supports this premise (12, 19).

We cannot rule out a potential contribution of increased accuracy of determining the exact time of sudden cardiac arrest, facilitated by prospectively obtained 911 call and other emergency medical services information in the Oregon study, as well as exact timing of recurrent ventricular arrhythmias available in the SCD-HeFT population. In previous studies, especially prior to the use of defibrillators, it was difficult to reliably assess the temporal relationships of sudden cardiac arrest and sudden cardiac death. In addition, retrospective death certificate-based surveillance, which is what many of the prior studies relied on for diagnosis of sudden death, has been shown to result in significant overestimation and inaccuracy in reporting the incidence of sudden cardiac arrest (30). However, given that multiple studies and animal models have all showed a biologic rhythm for occurrence of ventricular arrhythmias, sudden cardiac arrest, and sudden death, it is more likely that loss of the circadian rhythm may have major contributions from shifts in environmental and biologic factors.

Emotional and psychological stressors have been shown to be related to an increased incidence of ventricular arrhythmias and sudden death (31, 32), and as the World Health Organization refers to stress as the “health epidemic of the 21st century,” it is very possible that with our technological advances (internet, smart phones, etc.) and the ability to be accessible at all hours, 7 days a week, the previously reported stressors at the beginning of the work week now pervade the entire week. Given the rapid alterations in how we electronically and digitally communicate with others, altered sleep routines may also be changing the previously normal 24 h patterns of activity, which has a large effect on the natural circadian rhythm. Moreover, the reported finding that patients with sleep apnea do not have the same nadir in sudden cardiac death as those without sleep apnea, increasing obesity and rates of sleep apnea may also be contributing to the shift away from a circadian rhythm in sudden cardiac arrest.

Future Directions

The findings from the SCD-HeFT and the Oregon Sudden Unexpected Death Study have significant implications for public health and the overall utilization of health care resources. Given the deviation in both patient and environmental factors that previously accounted for the presence of circadian and septadian variations in sudden cardiac arrest, more studies are needed in order to help elucidate the mechanisms behind this new shift. The conflicting findings of the recent Veterans Affairs study in ICD patients (27) are also important to consider, but a focus on more population-based research that is not solely limited to patients with ICDs is imperative. Establishing whether or not circadian rhythm plays a role in sudden cardiac arrest could be vital for optimal distribution of health care resources and emergency medical services during the 24 h period.

Furthermore, this paradigm shift may help to build new risk prediction models or at least help us to identify patients who may be more at risk for lethal arrhythmias during the nighttime hours, such as patients with obstructive sleep apnea. The identification of such sub-groups would allow us to better allocate medical resources and focus on goals for both prevention and treatment. Attention to management of psychosocial stressors will also be critical as technological advances continue at a rapid pace. The more widespread use of beta blockers may have, in part, accounted for the decrease in morning sympathetic surges that previously led to arrhythmogenic events. As newer treatments emerge, we will need to constantly re-assess our current risk models to account for such differences. Similarly, as robust autonomics are more commonly associated with ventricular arrhythmias, the increased prevalence of autonomic dysfunction, which is common in many chronic diseases such as diabetes, may also be playing a role in the emergence of pulseless electrical activity and asystole as the predominating presenting rhythms for sudden cardiac arrest. Whether the paradigm shift in shockable versus non-shockable rhythms may have contributed to the loss of sudden cardiac arrest circadian variation also warrants further investigation.

Conclusion

Though prior studies have shown a peak time associated with sudden cardiac arrest with predictable circadian and septadian variation, newer studies have shown a loss of these patterns, suggesting that this may no longer be the case. Both patient-related as well as environmental factors may play a role. Because this paradigm shift has profound research, clinical, and public health implications, it needs careful consideration and requires evaluation in further population-based studies.

Acknowledgments

Funding sources: Funded by National Institutes of Health, National Heart Lung and Blood Institute (NHLBI) grants R01HL122492 and R01HL126938 to SSC. SSC holds the Pauline and Harold Price Chair in Cardiac Electrophysiology at Cedars-Sinai, Los Angeles.

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest

AR: none

SSC: none

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Myerburg RJaG JJ Cardiac Arrest and Sudden Cardiac Death. In: Zipes DPL P; Braunwald E; Bonow RO; Mann DL; Tomaselli GF, editor. Braunwald’s Heart Disease: A Textbook of Cardiovascular Medicine. 1: Elsevier; 2019. p. 807–47. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Benjamin EJ, Muntner P, Alonso A, Bittencourt MS, Callaway CW, Carson AP, et al. Heart Disease and Stroke Statistics-2019 Update: A Report From the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2019;139(10):e56–e528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jeyaraj D, Haldar SM, Wan X, McCauley MD, Ripperger JA, Hu K, et al. Circadian rhythms govern cardiac repolarization and arrhythmogenesis. Nature. 2012;483(7387):96–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Paschos GK, FitzGerald GA. Circadian clocks and vascular function. Circ Res. 2010;106(5):833–41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Takeda N, Maemura K. Circadian clock and cardiovascular disease. J Cardiol. 2011;57(3):249–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Takeda N, Maemura K. Circadian clock and the onset of cardiovascular events. Hypertens Res. 2016;39(6):383–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fishman GI, Chugh SS, Dimarco JP, Albert CM, Anderson ME, Bonow RO, et al. Sudden cardiac death prediction and prevention: report from a National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute and Heart Rhythm Society Workshop. Circulation. 2010;122(22):2335–48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Teodorescu C, Reinier K, Dervan C, Uy-Evanado A, Samara M, Mariani R, et al. Factors associated with pulseless electric activity versus ventricular fibrillation: the Oregon sudden unexpected death study. Circulation. 2010;122(21):2116–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Muller JEL PL; Willich SN; Tofler GH; Aylmer G; Klangos I; Stone PH Circadian variation in the frequency of sudden cardiac death. Circulation. 1987;75:131–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Muller JE, Stone PH, Turi ZG, Rutherford JD, Czeisler CA, Parker C, et al. Circadian variation in the frequency of onset of acute myocardial infarction. N Engl J Med. 1985;313(21):1315–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Willich SN, Levy D, Rocco MB, Tofler GH, Stone PH, Muller JE. Circadian variation in the incidence of sudden cardiac death in the Framingham Heart Study population. Am J Cardiol. 1987;60(10):801–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Peters RW, Muller JE, Goldstein S, Byington R, Friedman LM. Propranolol and the morning increase in the frequency of sudden cardiac death (BHAT Study). Am J Cardiol. 1989;63(20):1518–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Willich SN, Goldberg RJ, Maclure M, Perriello L, Muller JE. Increased onset of sudden cardiac death in the first three hours after awakening. Am J Cardiol. 1992;70(1):65–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Levine RL, Pepe PE, Fromm RE Jr., Curka PA, Clark PA. Prospective evidence of a circadian rhythm for out-of-hospital cardiac arrests. Jama. 1992;267(21):2935–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Arntz HRW SN; Oeff M; Bruggemann T; Stern R; Heinzmann A; Matenaer B; Schroder R. Circadian Variation of Sudden Cardiac Death Reflects Age-Related Variability in Ventricular Fibrillation. Circulation. 1993;88:2284–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Aronow WS, Ahn C. Circadian variation of primary cardiac arrest or sudden cardiac death in patients aged 62 to 100 years (mean 82). Am J Cardiol. 1993;71(16):1455–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Moser DK, Stevenson WG, Woo MA, Stevenson LW. Timing of sudden death in patients with heart failure. Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 1994;24(4):963–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lampert RR L; Batsford W; Lee F; McPherson C Circadian variation of sustained ventricular tachycardia in patients with coronary artery disease and implantable cardioverter-defibrillators. Circulation. 1994;90:241–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wood MA, Simpson PM, London WB, Stambler BS, Herre JM, Bernstein RC, et al. Circadian pattern of ventricular tachyarrhythmias in patients with implantable cardioverter-defibrillators. Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 1995;25(4):901–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tofler GH, Gebara OC, Mittleman MA, Taylor P, Siegel W, Venditti FJ Jr., et al. Morning peak in ventricular tachyarrhythmias detected by time of implantable cardioverter/defibrillator therapy. The CPI Investigators. Circulation. 1995;92(5):1203–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mallavarapu CP S; Schwartzman D; Callans DJ; Heo J; Gottlieb CD; Marchlinski FE Circadian variation of ventricular arrhythmia recurrences after cardioverter-defibrillator implantation in patients with healed myocardial infarcts. American Journal of Cardiology. 1995;75:1140–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Englund A, Behrens S, Wegscheider K, Rowland E. Circadian variation of malignant ventricular arrhythmias in patients with ischemic and nonischemic heart disease after cardioverter defibrillator implantation. Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 1999;34(5):1560–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Peckova M, Fahrenbruch CE, Cobb LA, Hallstrom AP. Weekly and seasonal variation in the incidence of cardiac arrests. American Heart Journal. 1999;137(3):512–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Arntz HRW SN; Schreiber C; Bruggemann T; Stern R; Schultheib HP Diurnal, weekly, and seasonal variation of sudden death. European Heart Journal. 2000;21:315–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Peters RW, McQuillan S, Resnick SK, Gold MR. Increased Monday incidence of life-threatening ventricular arrhythmias. Experience with a third-generation implantable defibrillator. Circulation. 1996;94(6):1346–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Peters RWM S; Gold MR Interaction of septadian and circadian rhythms in life-threatening ventricular arrhythmias in patients with implantable cardioverter-defibrillators. American Journal of Cardiology. 1999;84:555–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Li Y, Nantsupawat T, Tholakanahalli V, Adabag S, Wang Z, Benditt DG, et al. Characteristics and periodicity of sustained ventricular tachyarrhythmia events in a population of military veterans with implantable cardioverter defibrillator. J Interv Card Electrophysiol. 2019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Patton KK, Hellkamp AS, Lee KL, Mark DB, Johnson GW, Anderson J, et al. Unexpected deviation in circadian variation of ventricular arrhythmias: the SCD-HeFT (Sudden Cardiac Death in Heart Failure Trial). J Am Coll Cardiol. 2014;63(24):2702–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ni Y-M, Rusinaru C, Reinier K, Uy-Evanado A, Chugh H, Stecker EC, et al. Unexpected shift in circadian and septadian variation of sudden cardiac arrest: the Oregon Sudden Unexpected Death Study. Heart Rhythm. 2019;16(3):411–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Chugh SS, Jui J, Gunson K, Stecker EC, John BT, Thompson B, et al. Current burden of sudden cardiac death: multiple source surveillance versus retrospective death certificate-based review in a large U.S. community. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2004;44(6):1268–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lampert R, Joska T, Burg MM, Batsford WP, McPherson CA, Jain D. Emotional and Physical Precipitants of Ventricular Arrhythmia. Circulation. 2002;106(14):1800–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hemingway H, Malik M, Marmot M. Social and psychosocial influences on sudden cardiac death, ventricular arrhythmia and cardiac autonomic function. Eur Heart J. 2001;22(13):1082–101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]