Abstract

Understanding the function of nitric oxide (NO), a lipophilic messenger in physiological processes across nervous, cardiovascular and immune systems, is currently impeded by the dearth of tools to deliver this gaseous molecule in situ to specific cells. To address this need, we developed iron sulfide nanoclusters that catalyse NO generation from benign sodium nitrite in the presence of modest electric fields. Locally generated NO activates the NO-sensitive cation channel, transient receptor potential vanilloid family member 1 (TRPV1), and latency of TRPV1-mediated Ca2+ responses can be controlled by varying the applied voltage. Integrating these electrocatalytic nanoclusters with multimaterial fibres allows NO-mediated neuronal interrogation in vivo. In situ generation of NO within the ventral tegmental area via the electrocatalytic fibres evoked neuronal excitation in the targeted brain region and its excitatory projections. This NO generation platform may advance mechanistic studies of the role of NO in the nervous system and other organs.

Nitric oxide (NO) is a gaseous signalling molecule involved in multiple biological processes, including neurotransmission, cardiovascular homeostasis, and immune response1–4. In the central nervous system, NO is involved in mediating synaptic plasticity and neurosecretion5. The essential role of NO across multiple signalling pathways has evoked a demand for regulating its levels in vitro and in vivo. Early studies have targeted endogenous NO synthase enzymes via genetic knock-out strategies or systemic delivery of pharmacological inhibitors6–8. More recently, NO-releasing materials (NORMs), triggered by non-enzymatic or enzymatic processes, have been designed to achieve more controlled and localized delivery of this molecule9–11. However, as tuning of the NO-release kinetics in a single NORM has been challenging9,12, multiple injections of different NORMs were necessary to study the biological effects of NO12,13. Furthermore, degradation of NORMs during delivery has often resulted in the off-target release of this molecule14,15. Consequently, there remains a need for techniques enabling the local release of NO at the cells and tissues of interest with tuneable release kinetics.

To address this need, we propose an electrocatalytic route to generate NO (Fig. 1a). This approach draws inspiration from enzymatic denitrification reaction of nitrite (NO2−) or nitrate (NO3-) substrates in biological systems16–18. Although the detailed mechanism of NO generation by enzymes remains an area of active study, it has been demonstrated that metal atoms such as copper and iron in these enzymes serve as active catalytic sites for NO2− reduction processes18. We aim to mimic this biological NO generation by employing nanoscale iron sulfide-based catalysts for the electrochemical denitrification reaction (Eq. 1)19:

| (1) |

Where NHE indicates normal hydrogen electrode.

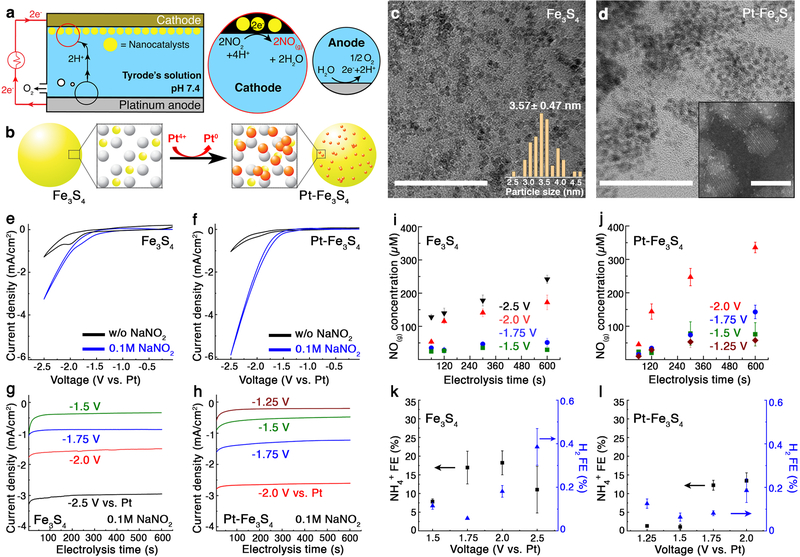

Fig. 1:

Fe3S4 and Pt-Fe3S4 nanocatalysts for electrochemical reduction of NO2− into NO. a, An illustration of the electrochemical NO-delivery system. b, A schematic of the galvanic replacement method for decoration on the Fe3S4 nanocatalysts with Pt. Fe, S, and Pt atoms are marked in yellow, white, and red, respectively. c-d, Transmission electron microscope (TEM) images of the Fe3S4 (c) and the Pt-Fe3S4 (d) nanocatalysts. Scale bar: 50 nm. Insets show the size distribution of the Fe3S4, obtained from 50 randomly chosen nanoparticles (c) and high-resolution scanning TEM images of the Pt-Fe3S4 nanocatalysts (d). Scale bar: 5 nm. The experiment was repeated three times independently with similar results. e-f, Cyclic voltammetry (CV) curves of the Fe3S4 (e) and the Pt-Fe3S4 (f) nanocatalysts in the presence and absence of NO2−. Scan rate: 50 mV/s. g-h, Chronoamperometry profiles of the Fe3S4 (g) and the Pt-Fe3S4 (h) nanocatalysts. i-j, Voltage-dependent NO generation (mean ± standard deviation (s.d.)) from the Fe3S4 (i) and the Pt-Fe3S4 (j) nanocatalysts (n=3 independent experiments for each group). k-l, The Faradaic efficiency (FE) for NH4+ and H2 (mean ± s.d.) from the Fe3S4 (k) and the Pt-Fe3S4 (l) nanocatalysts (n=3 independent experiments for each group). Voltage ranges of –1.5 V to –2.5 V and –1.25 V to –2.0 V vs Pt were chosen for the Fe3S4 and the Pt-Fe3S4 nanocatalysts, respectively.

In the presence of an electric field, NO2− can be reduced by iron sulfide-based catalysts at the cathode allowing for the localized generation of NO. Furthermore, the NO release kinetics can be quantitatively controlled by varying the applied voltage. We applied this strategy to control NO-dependent neuronal signalling in vitro and in the mouse brain.

Electrochemical NO generation by iron sulfide-based nanocatalysts

Fe3S4 nanocatalysts with diameters of ~3 nm were prepared through a hot injection method20. To achieve increased catalytic activity and selectivity toward NO, we also explored Pt, a widely studied NO2− reduction catalyst19,21,22, as a hetero-atom dopant on the surface of the Fe3S4 nanoclusters. Pt decoration was conducted via a galvanic replacement method (Fig. 1b–d and Supplementary Fig. 1–3)23. High-resolution high-angle annular dark-field scanning transmission electron microscopy (HAADF-STEM) images and bright-field STEM images revealed the presence of single Pt atoms and their clusters on the Fe3S4 nanocatalysts following the galvanic replacement (Fig. 1d and Supplementary Fig. 4).

Electrocatalytic activity of the Fe3S4 and Pt-decorated Fe3S4 nanocatalysts (Pt-Fe3S4) was assessed by loading them onto cathodes in a one-compartment electrochemical cell with a two-electrode configuration. In the absence of NO2−, cyclic voltammetry (CV) curves of the nanocatalysts exhibited only broad redox features appearing at approximately –2.0 V vs Pt, followed by hydrogen evolution reaction at approximately –2.3 V vs Pt (Fig 1e,f, and Supplementary Fig. 5). In the presence of 0.1 M NaNO2, threshold voltages were positively shifted, and significant Faradaic currents appeared in the CV curves of Fe3S4 and Pt-Fe3S4 nanocatalysts. We found that these Faradaic currents increased as the concentration of NO2− or supporting electrolyte in the Tyrode’s solution increased, confirming that NO2− was electrochemically reduced (Supplementary Fig. 6 and Fig. 7). As anticipated, Pt-Fe3S4 nanocatalysts showed higher activity as compared to Fe3S4 counterparts (Fig. 1e,f).

The identity of the products in electrocatalytic cells with the Fe3S4 and Pt-Fe3S4 loaded cathodes was examined via chronoamperometry between –1.5 and –2.5 V and –1.25 V and –2.0 V vs Pt, respectively (Fig. 1g,h). The amount of generated NO was quantified by using 4-amino−5-methylamino−2’,7’-difluorofluorescein (DAF-FM), a NO capturing reagent24, which reacts with NO to form a fluorescent benzotriazole derivative (Supplementary Fig. 8)25. The measured NO concentration likely presents a lower-bound value due to the expected loss of this unstable molecule26,27. The analysis thus only provided voltage-dependent electrochemical NO generation kinetics for each nanocatalyst. In the case of the Fe3S4 nanocatalysts, the amounts of captured NO monotonically increased with electrolysis time, implying that some of the generated NO could be accumulated despite its decay. Additionally, more NO was detected at greater negative voltages, consistent with CV and chronoamperometry results (Fig. 1i). Similar electrokinetic trends were observed in the Pt-Fe3S4 nanocatalysts (Fig. 1j). Consistent with CV measurements, the amount of captured NO produced at the Pt-Fe3S4 containing cathodes was higher than that produced at the cathodes loaded with Fe3S4 nanocatalysts. Based on the captured amount of NO, Faradaic efficiency toward NO (FENO) was plotted versus the applied voltage. Due to the NO decay, 10−20 % of FENO was obtained and the FENO decreased over time during electrolysis (Supplementary Fig. 9).

To further understand the generation, diffusion, and decay of NO, we calculated the time- and distance-dependent NO concentration profiles with respect to the cathodes (details in Methods)27,28. Our calculations indicated that NO concentration rapidly decreased in the first 1000 μm from the cathode and the concentration profile reached steady state within a short period of time (< 1 s), due to autooxidation. These results indicated that the effects of electrochemically generated NO are spatially restricted due to its short half-life. Similarly, the type of electrocatalyst was shown to influence the equilibrium NO profiles (Supplementary Fig. 10, 11).

In addition to NO, we also quantified undesirable side products at the cathode, such as molecular hydrogen (H2(g)), ammonium ions (NH4+(aq)), and hydrogen peroxide (H2O2(aq)) and confirmed that negligible quantities of side products were generated (Fig. 1k,l, and Supplementary Fig. 12, 13)19. At the anode, predominantly oxygen evolution was observed with minor evolution of chlorine (Supplementary Fig. 14). Taken together, these findings indicated that NO was the major NO2− reduction product for both nanocatalysts.

Modulation of cell signalling via electrochemically generated NO in vitro

To illustrate the utility of our electrocatalytic approach for controlling NO-mediated biological signalling, we first applied it to trigger NO-sensitive ion channels in vitro. Among the diversity of ion channels that react with NO, cation channels from the transient receptor potential vanilloid (TRPV) family were shown to be triggered by this molecule via S-nitrosylation of the cysteine residues within their pores3,29. Consequently, we adopted TRPV family member 1 (TRPV1), a well-characterized receptor of thermal and chemical stimuli broadly expressed in the central and peripheral nervous system, as a test-bed for the NO-mediated signalling.

Human embryonic kidney (HEK) 293FT cells were co-transfected with a plasmid carrying TRPV1 separated from a fluorescent protein mCherry by the posttranscriptional cleavage linker p2A under the excitatory neuronal promoter calmodulin kinase II α-subunit (CaMKIIα::TRPV1-p2A-mCherry) and a plasmid carrying a genetically encoded fluorescent calcium ion (Ca2+) indicator GCaMP6s under the broad cytomegalovirus promoter (CMV::GCaMP6s). The latter allowed for monitoring of intracellular Ca2+ influx in response to the triggering of TRPV1. Consistent with the previous reports3,29, an increase in intracellular Ca2+ in cells expressing TRPV1 (TRPV1+) was observed in response to the NO donor (DEA NONOate), whereas cells not expressing TRPV1 (TRPV1–) did not exhibit any increase in intracellular Ca2+. Approximately 96 % of TRPV1+ cells showed robust Ca2+ responses (as marked by the normalized GCaMP6s fluorescence increase ΔF/Fo ≥ 50 %) induced by 10 mM of the donor following 200 s (Fig. 2a,b). A noticeable increase in intracellular Ca2+ was observed at donor concentrations as low as 500 μM (Supplementary Fig. 15). Consistent with Ca2+ imaging results, whole-cell patch-clamp recordings showed that the addition of the NO donor induced significant inward currents in TRPV1+ cells, but not in TRPV1- cells (Fig. 2c, d).

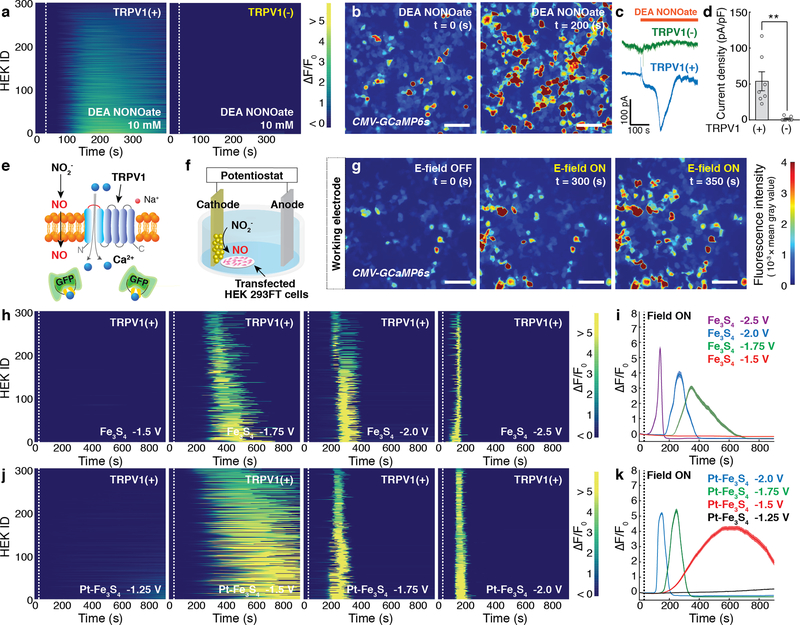

Fig. 2: Electrochemically produced NO triggers TRPV1.

a, GCaMP6s fluorescence intensity in 300 TRPV1+ (Left) or TRPV1– (Right) HEK293FT cells following addition of a NO donor, DEA NONOate (10 mM), at 30 s (dashed lines). b, Representative time-lapse images of global Ca2+ responses in TRPV1+ cells in response to the DEA NONOate infusion. Scale bar: 50 μm. c, Representative whole-cell patch-clamp traces of TRPV1+ cells (blue) and TRPV1- cells (green) in response to DEA NONOate infusion at the holding potential of – 40 mV. d, Peak current density (mean ± standard error of the mean (s.e.m.)) following DEA NONOate infusion in TRPV1+ cell or TRPV1- cells. A significant difference was observed between two groups, as confirmed by one-tailed Student’s t-test (n = 7 cells for each group, ** (p = 0.0038) < 0.01). e, A schematic illustrating Ca2+ influx through TRPV1 mediated by electrochemically produced NO. f, Experimental scheme for the electrochemical NO-delivery in vitro. g, Representative time-lapse images of Ca2+ influx into TRPV1+ cells evoked by the Fe3S4-catalysed NO generation at –1.75 V vs Pt. The cathode decorated with the Fe3S4 nanocatalysts was positioned at the left edge in all the images. Scale bar: 50 μm. (a, b, and g) The experiment was repeated three times independently with similar results. h-k, Individual (h, j) and averaged (i, k) GCaMP6s fluorescence traces for TRPV1+ cells (n = 300 cells for each trace) in the presence of Fe3S4 (h, i) and the Pt-Fe3S4 (j, k) nanocatalysts and 0.1 M NaNO2. Voltages of –1.5, –1.75, –2.0, –2.5 V and –1.25, –1.5, –1.75, –2.0 V vs Pt were applied at 30 s (dashed lines) in the presence of Fe3S4 and Pt-Fe3S4 nanocatalysts, respectively. i, k, Solid lines, and shaded areas indicate the mean and s.e.m., respectively. F0 indicates the mean of the fluorescence intensity during the initial 10 s of measurement.

We then investigated whether the electrochemical NO-delivery could similarly evoke intracellular Ca2+ influx through TRPV1 (Fig. 2e). In these experiments, conductive fluorine-doped tin oxide (FTO) substrates coated with Fe3S4 or Pt-Fe3S4 acted as cathodes against Pt anodes in Tyrode’s solution containing 0.1 M NaNO2. Cathodes were positioned in the immediate proximity of the TRPV1+ cells to ensure the efficient delivery of NO (Fig. 2f). NO generation catalysed by Fe3S4 nanoclusters at the cathode triggered Ca2+ influx into TRPV1+ cells. At –1.75 V vs Pt, only TRPV1+ cells within 50 μm proximity from the cathode were activated after 300 s. Consistent with our calculations of the NO diffusion profiles (Supplementary Fig. 10), the Ca2+ influx into the TRPV1+ cells located at greater distances from the cathodes was triggered gradually (Fig. 2g, Supplementary Fig. 16).

Ca2+ influx into TRPV1+ cells at the identical reaction conditions was blocked by the addition of 20 μM TRPV1 antagonist BCTC (N-(4-tertiarybutylphenyl)−4-(3-chloropyridin−2-yl) tetrahydropyrazine−1(2H)-carboxamide)30. No substantial Ca2+ influx was observed in TRPV1– cells in the presence of applied voltage and NaNO2 and in TRPV1+ cells in the absence of NaNO2. Additionally, injection of NH4+, a minor byproduct of the NO2− reduction, did not yield measurable Ca2+ responses in TRPV1+ cells (Supplementary Fig. 17). Furthermore, we found that ascorbate, which can selectively reduce nitrosothiol generated from the interaction between NO and thiol groups in TRPV13,31, reduced the intracellular Ca2+ concentration as indicated by the decrease in GCaMP6s fluorescence (Supplementary Fig. 18). These results supported that the Ca2+ influxes observed in TRPV1+ cells are mainly attributable to electrochemically formed NO.

The electrochemical approach further afforded variations in the latency of the Ca2+ responses in TRPV1+ cells. Consistent with accelerated NO release kinetics, lower latency Ca2+ responses were observed in TRPV1+ cells by increasing the negative voltage at the nanocatalyst loaded cathodes vs Pt (Fig. 2h–k). In the presence of Fe3S4 nanocatalysts, a robust increase in GCaMP6s fluorescence (ΔF/Fo ≥ 50 %) in TRPV1+ cells was observed 255 ± 3 s, 192 ± 1 s, and 92 ± 2 s following application of –1.75 V, –2.0 V, and –2.5 V, respectively (Fig. 2h). Peak Ca2+ influx was observed at 345 s at –1.75 V, 265 s at –2.0 V, and 144 s at –2.5 V (Fig. 2i). No response was observed at voltages ≥ –1.5 V (Fig. 2h, i). Higher electrocatalytic activity of Pt-Fe3S4 nanoclusters allowed for NO generation at lower negative voltages (≥–1.5 V), and lower latency Ca2+ responses were observed as compared to those observed for Fe3S4 nanocatalysts at the same applied voltage (Fig. 2j, k).

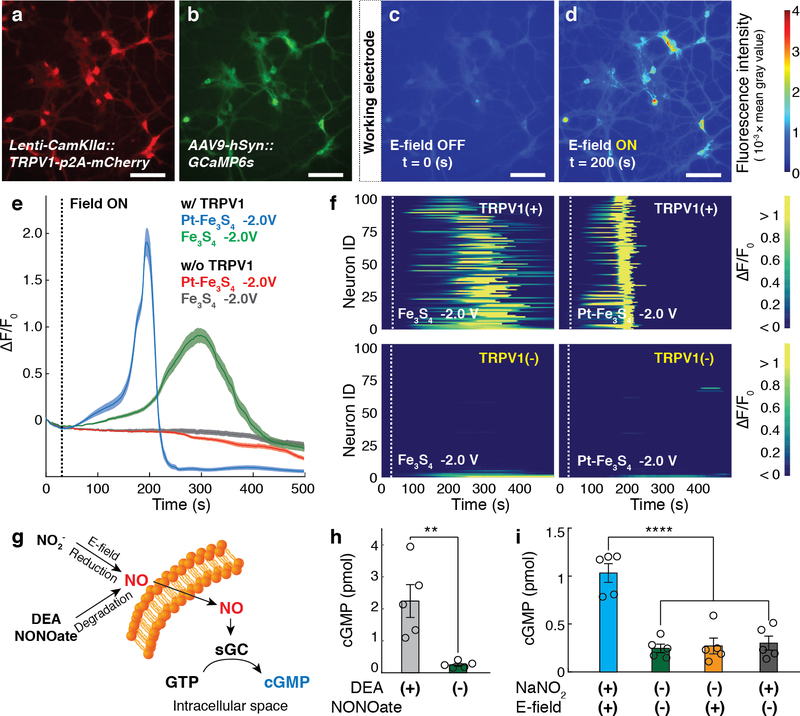

Electrochemically generated NO was sufficient to activate TRPV1+ primary hippocampal neurons. The neurons were co-transduced with lentivirus and adeno-associated virus serotype 9 carrying TRPV1-p2A-mCherry and GCaMP6s under CaMKIIα and broad neuronal human synapsin promoter, respectively (Lenti-CaMKIIα::TRPV1-p2A-mCherry and AAV9-hSyn::GCaMP6s) (Fig. 3a,b). In the presence of Fe3S4 or Pt-Fe3S4 nanocatalysts, NO generated by applying –2.0 V was sufficient to drive Ca2+ influx into 87 % of TRPV1+ neurons (ΔF/Fo ≥ 50 %). In contrast, negligible Ca2+ responses were evoked in TRPV1– neurons at identical reaction conditions. Consistent with observations in HEK293FT cells, the latency to reach GCaMP6s fluorescence increase ΔF/Fo ≥ 50 % in TRPV1+ neurons was shorter in the presence of Pt-Fe3S4 (153 ± 2 s) than in the presence of Fe3S4 nanocatalysts (234 ± 10 s) (Fig. 3c–f).

Fig. 3: Signalling pathways mediated by electrocatalytic NO generation in vitro.

a-b, Fluorescent images of hippocampal neurons co-transduced with TRPV1 and GCaMP6s. Scale bar: 50 μm. c-d, Representative images of GCaMP6s intensity of TRPV1+ neurons prior to (c) and following (d) NO release electrocatalysed by Pt-Fe3S4 at –2.0 V vs Pt. The Pt-Fe3S4 nanocatalysts-loaded cathode was located at the left edge in all the images. (a-d) The experiment was repeated three times independently with similar results. e, Normalized GCaMP6s fluorescence averaged across TRPV1+ and TRPV1– neurons (n = 100 neurons for each trace) following NO delivery electrocatalysed by Pt-Fe3S4 and Fe3S4 nanoclusters at –2.0 V vs Pt applied at 30 s (dashed line). Solid lines and shaded areas indicate the mean and s.e.m., respectively. f, Individual GCaMP6s fluorescence in 100 TRPV1+ and 100 TRPV1– neurons following NO delivery electrocatalysed by Pt-Fe3S4 and Fe3S4 at –2.0 V vs Pt applied at 30 s (dashed lines). F0 indicates the mean of the fluorescence intensity during the initial 10 s of measurement. g, An illustration of the NO-sGC-cGMP signalling pathway in genetically intact cerebellar neurons. GTP stands for guanosine 5’-triphosphate. h, Intracellular cGMP levels (mean ± s.e.m.) in 5 × 106 cerebellar neurons following incubation with DEA NONOate (10 mM) or Tyrode’s solution for 5 min. A significant difference was found between two groups, as assessed by one-tailed Student’s t-test (n = 5 independent experiments for each group, ** (p = 0.0089) < 0.01). i, Intracellular cGMP levels (mean ± s.e.m.) in 5 × 106 cerebellar neurons following NO delivery electrocatalysed by Pt-Fe3S4 at –2.5 V vs Pt for 5 min. Statistical significance of an increase in cGMP levels after NO delivery as compared to controls was confirmed by one-way ANOVA and Tukey’s multiple comparison test (n = 5 independent experiments for each group, F3,16 = 24.41, **** (p = 3.3 × 10−6) < 0.0001).

We then examined whether electrochemically generated NO could activate the soluble guanylate cyclase (sGC), an intracellular and endogenous NO receptor, in genetically intact cerebellar neurons. The sGC activity in neurons was evaluated by measuring the intracellular cyclic guanosine 3’5’-monophosphate (cGMP) levels (Fig. 3g). Consistent with prior research32, a substantial increase in the cGMP levels in the neurons (~ 800 %) was observed following the addition of 10 mM of the NO donor (Fig. 3h). Similarly, NO generated by Pt-Fe3S4 nanocatalysts at –2.5 V vs Pt increased the cGMP levels in the cerebellar neurons, whereas no significant changes in the cGMP levels were found in the absence of the applied voltage or addition of NaNO2 (Fig. 3i). These results indicated that our electrocatalytic approach could be extended to modulate the endogenous NO-signalling pathways. For instance, in future it may be possible to apply our approach to advance the study of synaptic plasticity mediated by NO through its interactions with sGC5. Furthermore, spatial restriction and tuneable kinetics afforded by our approach may offer additional insights into the role of NO in specific circuits or signalling cascades33.

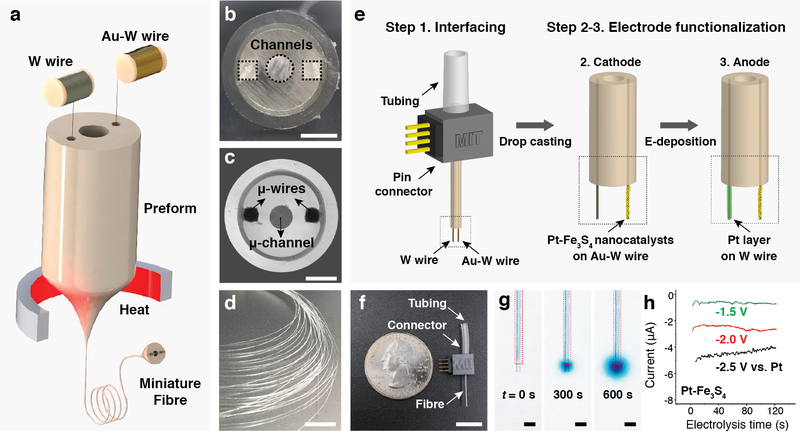

Design and characterization of implantable NO-delivery probes

To investigate the utility of our NO-delivery approach for applications in vivo, we designed miniature electrocatalytic probes suitable for chronic implantation into the mouse brain. We adopted a thermal drawing process that has previously enabled the fabrication of multifunctional, fibres for neural interfaces (Fig. 4a–d)34,35. A macroscopic polycarbonate preform (12 mm in diameter) containing three hollow channels was fabricated by standard machining (Fig. 4b)35. One of the channels was intended for delivery of NaNO2 solution and the remaining two channels were designed to host microelectrodes forming the electrocatalytic cell for reduction of the delivered NaNO2 into NO. During the draw (Fig. 4a), the preform (Fig. 4b) was heated above the polycarbonate glass transition temperature and stretched into a 5 m-long fibre with a diameter of ~ 400 μm (Fig. 4c,d). Tungsten and gold-coated tungsten microwires (50 μm in diameter) were directly converged into the preform from the wire spools (Fig. 4a), resulting in a probe featuring two microelectrodes and a microfluidic channel.

Fig. 4: Fabrication and characterization of the NO-delivery fibre.

a, An illustration of the fibre drawing process. Tungsten and gold-plated tungsten wires were converged into the preform during the draw. b, Cross-sectional image of the preform containing three hollow channels. Scale bar: 3 mm. c, Cross-sectional microscope image of the resulting fibre. Scale bar: 100 μm. d, A photograph of a bundle of fibre produced during the draw. Scale bar: 10 cm. e, An illustration of fibre connectorization, followed by functionalization of the cathode and anode microwires with Pt-Fe3S4 nanocatalysts and Pt layer, respectively. f, A photograph of a fully assembled NO-delivery fibre. Scale bar: 10 mm. g, Infusion of Tyrode’s solution containing 0.1 M NaNO2 and a dye (BlueJuice) into a brain phantom (0.6% agarose gel) through the microfluidic channel. Images were taken at 0, 300 and 600 s after the infusion at a rate of 100 nL/min. Scale bar: 500 μm. h, Chronoamperometry profiles of the NO-delivery fibre in the Tyrode’s solution containing 0.1 M NaNO2.

Following fibre connectorization to external tubing and electrical pin connectors, 300 μm lengths of the embedded microwires were exposed from the fibre tips for further functionalization. Pt-Fe3S4 nanoclusters, which exhibited greater electrocatalytic activity as compared to Fe3S4 counterparts, were deposited onto the exposed gold-coated tungsten microwire cathodes. The tungsten microwires were electroplated with Pt and used as the anodes (Fig. 4e and Supplementary Fig. 19)36. The fully assembled NO-delivery fibres exhibited height and weight of ~25 mm and 0.3−0.4 g, respectively (Fig. 4f). The microfluidic capabilities of the probes were corroborated by passing the solution of a blue dye and NaNO2 into agarose brain phantoms (Fig. 4g). Electrocatalytic conversion of the delivered NaNO2 into NO was characterized via chronoamperometry. The current density at the exposed microwires (50 μm in diameter and 300 μm in length) was - 4 mA/cm2 at –2.0 V vs Pt, which was similar to that in the bulk electrochemical cells used for the in vitro studies (Fig. 1h, Fig. 4h, and Supplementary Fig. 20). Akin to the bulk cells, the electrocatalytic fibres were capable of NO generation at the cathodes, which mediated Ca2+ influx in TRPV1+ cells in vitro, while oxygen evolution mainly occurred at the anodes (Supplementary Fig. 21, 22).

NO-mediated neuronal stimulation in vivo

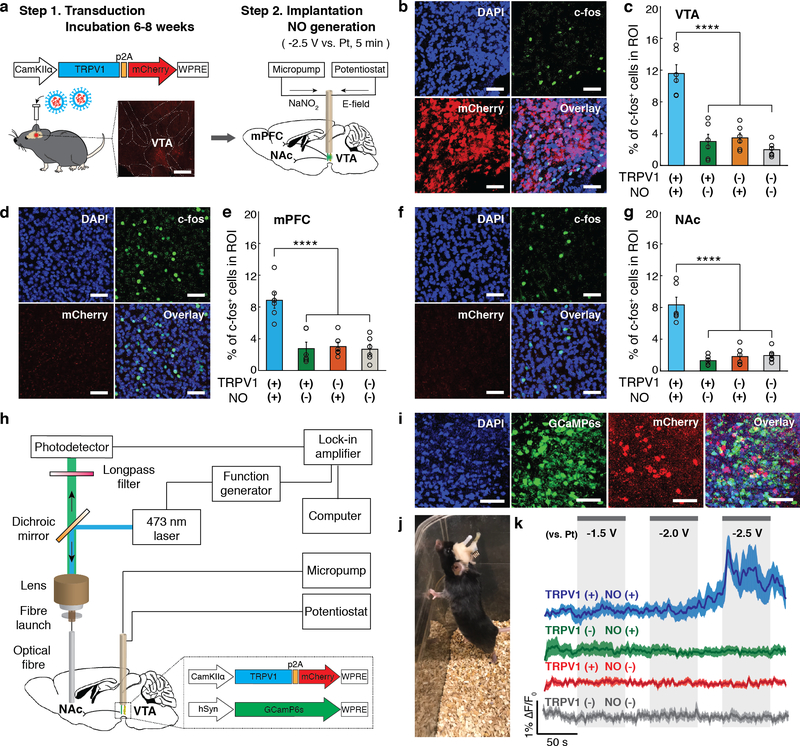

We next applied the electrocatalytic fibres to drive NO-mediated responses in vivo. We chose mouse ventral tegmental area (VTA) as our target brain region due to its low endogenous TRPV1 expression levels and well-characterized projection circuits37–39. The mice were transduced in the VTA with Lenti-CaMKIIα::TRPV1-p2A-mCherry (TRPV1+) or a control virus (Lenti-CaMKIIα::mCherry, TRPV1–) to account for potential effects of NO on the endogenously expressed channels40,41. Following a 6−8 weeks incubation period, the mice were implanted with NO-generation fibres in the same region. TRPV1 expression as marked by mCherry fluorescence was observed in the ~350 μm radial vicinity from the viral injection sites in the VTA. The anatomical locations of the exposed microwires of the implanted electrocatalytic fibres were aligned with TRPV1 expression in the VTA (Supplementary Fig. 23). To locally generate NO with the implanted fibres, Tyrode’s solution containing 0.1 M NaNO2 was infused into the VTA via the microfluidic channels and –2.5 V was applied to the integrated Pt-Fe3S4 coated cathodes vs the integrated Pt-coated anodes (Fig. 5a).

Fig. 5: Neuronal stimulation mediated by NO-delivery via implanted fibres in vivo.

a, An illustration of the virus-assisted gene delivery, fibre implantation, and NO generation in the mouse brain. Inset: A confocal image of TRPV1-p2A-mCherry expression in the mouse VTA. Scale bar: 500 μm. b-g, Confocal images (in TRPV1+ mice) (b, d, and f) and percentages of the c-fos expressing neurons among DAPI-labeled cells (mean ± s.e.m.) (c, e, and g) in the region of interest (ROI) in the VTA (b, c), mPFC (d, e), and NAc (f, g) following electrocatalytic NO generation in the VTA. Scale bar: 50 μm. Statistical significance of an increase in c-fos expression after NO generation in TRPV1+ mice as compared to controls was confirmed by one-way ANOVA and Tukey’s multiple comparison tests (n = 6 mice, VTA F3,20 = 29.97 p = 1.3 × 10−7, mPFC F3,20 = 15.49 p = 1.92 × 10−5, NAc F3,20 = 33.54 p = 5.4 × 10−8, **** p < 0.0001). h, An illustration of the fibre photometry setup integrated with the micropump and potentiostat for NO generation. i, Representative confocal microscope images of a mouse VTA co-expressing GCaMP6s and TRPV1-p2A-mCherry. Scale bar: 50 μm. The experiment was repeated three times independently with similar results. j, A mouse implanted with a NO-delivery fibre in the VTA and an optical fibre in the NAc. k, Normalized GCaMP6s fluorescence traces in the NAc of the anesthetized TRPV1+ (blue) and TRPV1– (green) mice in the presence of NO generation and the NAc of TRPV1+ (red) and TRPV1- mice (gray) in the presence of voltage alone (no NaNO2 infusion). Solid lines and shaded areas indicate the mean and s.e.m., respectively (n = 5 mice per condition). F0 indicates the mean of the fluorescence intensity during the initial 10 s of measurement.

The extent of NO-mediated neuronal excitation in the VTA was first investigated via the immunofluorescence analysis of the expression of an immediate-early gene c-fos, which was previously shown to be upregulated in electroactive cells in response to Ca2+ influx42. Consistent with these prior reports38,39, a significantly higher percentage of c-fos positive cells relative to all cells as marked by nuclear stain DAPI was found in the VTA of TRPV1+ mice subjected NO generation as compared to control groups, which included TRPV1+ mice where the voltage was not applied following NaNO2 delivery, TRPV1– mice subjected to NO generation, and TRPV1– mice where the only voltage was applied without NaNO2 delivery (Fig. 5b,c). We also observed upregulation of c-fos expression in the nucleus accumbens (NAc) and medial prefrontal cortex (mPFC) of TRPV1+ mice subjected to electrocatalytic NO generation (Fig. 5d–g). The NAc and mPFC receive excitatory projections from the VTA37–39.

Consistent with c-fos expression analyses, fibre photometry recordings of GCaMP6s fluorescence showed that NO released from the implanted fibres could trigger neuronal activity in the VTA (Fig. 5h–k). In these experiments, a cocktail of Lenti-CaMKIIα::TRPV1-p2A-mCherry (or Lenti-CaMKIIα::mCherry) and AAV9-hSyn::GCaMP6s was injected into the mouse VTA (Fig. 5i). Following a 6−8 week incubation period, the mice were implanted with the NO delivery fibres in the VTA and the conventional silica optical fibres the NAc, respectively (Fig. 5j). Confocal image analyses confirmed the GCaMP6s expression in cell bodies in the VTA and the VTA axons projecting to the NAc (Supplementary Fig. 24). Consistent with prior studies that have shown that neuronal stimulation in the VTA can be photometrically detected in their excitatory projections in the NAc39, we found that in TRPV1+ mice NO-mediated excitation of the VTA neurons yields an increase in the GCaMP6s fluorescence in their terminals in the NAc. A modest increase in intracellular Ca2+ was observed following a 60 s long application of –2.0 V to the fibre cathodes in the presence of NaNO2. Applying –2.5 V has resulted in a rapid rise in GCaMP6s fluorescence consistent with accelerated NO generation kinetics. No significant GCaMP6s fluorescence change was observed in TRPV1– mice under the same stimulation conditions (Fig. 5k). These findings indicate that the interplay between the TRPV1 overexpression and NO delivery in the VTA dominates over other possible mechanisms potentially contributing to the GCaMP6s fluorescence increase in the NAc, including modulation of non-VTA neurons potentially projecting to the NAc from the surrounding regions that could have been directly transduced by the AAV9-hSyn::GCaMP6s. Similarly, the application of the cathode voltage alone was insufficient to evoke Ca2+ influx in the NAc projecting axons in either TRPV1+ or TRPV1- mice (Fig. 5k). This is expected as the current elicited by –2.5 V was ~ 5 μA, which was significantly lower than the values (≥50 μA) typically used for direct electric neural stimulation43,44.

To evaluate the biocompatibility of our NO-delivery strategy in vivo, we investigated the interfaces between the brain tissue and the implanted fibres. Consistent with prior tissue analyses in the vicinity of polymer fibres34,35, NO-delivery fibres (400 μm in diameter) resulted in the significantly lower presence of astrocytes (as marked by glial fibrillary acidic protein, GFAP) and activated microglia (as marked by ionized calcium-binding adaptor molecule 1, Iba1) 7 days following implantation, as compared to the relatively smaller stainless steel microwires (300 μm in diameter). In the case of GFAP, the statistical difference between fibre and microwire groups was still observable 28 days following implantation, while there was no noticeable difference in Iba1 levels among groups following the same time period. Furthermore, we did not detect significant variations in levels of GFAP and Iba1 markers between the mice subjected vs not subjected to NO stimulation, likely due to the intermittent nature of NO release exclusively in the presence of applied voltage and the rapid decay of NO26 (Supplementary Fig. 25). In addition, no noticeable differences in cytotoxicity (and no observable deleterious effects on the local tissue) were observed between the VTA of mice subjected vs not subjected to NO generation as quantified by the cleaved caspase−3 assays (Supplementary Fig. 26). Finally, we confirmed that the Pt-Fe3S4 nanocatalysts, which did not evoke any observable cytotoxic responses in vitro or in vivo, remained stable at the surfaces of the cathodes two months following implantation into the mouse brain (Supplementary Fig. 27, 28).

Conclusions

We have designed a strategy that enables the on-demand generation of NO, a lipophilic messenger in physiological processes including synaptic plasticity, vasodilation, and tumoricidal action of macrophages1,2, from the benign metabolite NaNO2 by applying an electric field to electrochemically active nanocatalysts. This strategy affords in situ generation of NO with controllable release kinetics in the targeted regions. Furthermore, this electrocatalytic system was implemented in an implantable probe created via a multimaterial fibre drawing allowing for NO-mediated interrogation of neural circuits in vivo. Although demonstrated for activation of a particular NO-sensitive channel (TRPV1) in vivo, this electrochemical NO-delivery paradigm could be extended to target other NO-sensitive ion channels3 (Supplementary Fig. 29) and endogenous NO receptors5,45, advancing the mechanistic understanding of NO function in the nervous system and other organs.

Methods

Fe3S4 nanocatalyst synthesis

The Fe3S4 nanocatalysts were synthesized via a hot injection method. A Schlenk line (James Glass), 4-channel temperature controller (J-KEM, QUAD-J-S), heating mantle (capacity: 100 mL), 3-neck flask (capacity: 100 mL, joint size: 14/20), glass condenser, vacuum adapter, hypodermic needle (Air-Tite, 16G × 5”), glass syringe with metal luer-lock hub (capacity: 10 mL), and injection needle (BD Medical, 18G × 1 1/2”) were used for the synthesis (Supplementary Fig. 1). Two different mixtures were prepared in separate 3-neck flasks under air. In the first mixture, 2 mmol of FeCl3 and 1 mmol of FeCl2 – 4H2O were dissolved in 10 mL of oleylamine. In the other flask, 4 mmol of elementary sulfur was dissolved in 5 mL of oleylamine. The holes of each 3-neck flask were plugged with a rubber septum, a thermocouple, and a condenser. Next, a nitrogen backfill and vacuum cycle was done three times at room temperature to remove the oxygen from both flasks. After this, these two separate mixtures were degassed at 60 °C for at least 1 hour with vigorous stirring under vacuum. After degassing, both flasks were switched back to a nitrogen atmosphere by flowing nitrogen into each flask. Next, the iron-oleylamine mixture was heated to 150 °C under nitrogen with ~10 °C/min ramp rate, while maintaining the sulfur pot at 60 °C under a nitrogen atmosphere. When the iron-oleylamine flask reached ~140 °C, a hypodermic needle was inserted in the sulfur pot and a separate needle was inserted in iron-oleylamine pot. Immediately after the iron-oleylamine mixture reached 150 °C, a glass syringe was connected to the hypodermic needle and the 5 mL of the sulfur mixture was removed with a glass syringe. The Glass syringe was then detached from the hypodermic needle and connected to the injection needle on iron-oleylamine pot. The sulfur mixture was injected rapidly into the iron-oleylamine solution. The reaction temperature was then set to be 240 °C and aged for 1 hour under nitrogen. The Fe3S4 containing solution was naturally cooled to below 100 °C under nitrogen. Then, all the ports were detached carefully and the black Fe3S4 containing solution was transferred into a glass vial.

Purification and ligand exchange of Fe3S4 nanocatalysts

The as-synthesized Fe3S4 containing solution was placed in a 60 °C oven for 30 min prior to purification. Then a 1:1:2 ratio of the synthesized solution (400 μL), ethanol (400 μL), and acetone (800 μL), were mixed and centrifuged (15,500 rpm, 5 min). The supernatant was discarded. Then 400 μL of toluene and 800 μL of acetone were added to the Fe3S4 precipitates. The mixture was sonicated and vortexed for 1 min and centrifuged (15,500 rpm, 5 min) again. This purification was then performed one more time, twice in total. After the purification steps, 500 μL of hexane was added to re-disperse the Fe3S4 nanocatalysts with sonication and vortexing. For the size selection, the hexane solution was centrifuged at 5,000 rpm for 30 s so that bigger sized particles (> 50 nm) were precipitated while the supernatant containing 3 nm-sized Fe3S4 nanocatalysts could be collected for further ligand exchange processes. Since as-synthesized Fe3S4 nanocatalysts are covered by hydrophobic oleylamine ligands, a ligand exchange was required. The Fe3S4 nanocatalysts were initially dispersed in 500 μL of hexane, and the concentration was roughly ~3.2 mg/mL. Then, 500 μL of a DMF solution of 0.01 M NOBF4 was mixed with 500 μL of Fe3S4 nanocatalysts containing solution in hexanes. The mixed solution was sonicated until a phase transfer occurred. We observed that Fe3S4 nanocatalysts in the hydrophobic hexane layer transferred to the hydrophilic DMF layer, as displayed in Supplementary Fig. 2. For purification, centrifugation (15,500 rpm, 5 min) was done with 300 μL of toluene and 300 μL of acetone. The collected Fe3S4 nanocatalysts were dispersed in 400 μL of ethanol.

Electrode preparation and electrochemical study

20 μL of the BF4 treated Fe3S4 nanocatalysts-containing solution was dropped on a 1 cm × 1 cm FTO glass in a 60 °C oven. The Fe3S4 droplet spread well on the entire FTO glass. The drop-casting was repeated for 4 times. The electrode was dried in a 60 °C oven for 1 hour. To make Pt decorated Fe3S4 nanocatalysts, 350 μM of K2PtCl6 was prepared in 40 mL of de-ionized water. The Fe3S4 nanocatalysts loaded FTO glass was then immersed in a K2PtCl6 solution and a magnetic stir bar was placed at the bottom of the beaker. Next, the solution was heated to 50 °C with stirring and aged for 1 hour. Then, the Pt decorated Fe3S4 (Pt-Fe3S4) nanocatalyst loaded FTO glass was gently rinsed with de-ionized water and dried at 80 °C oven. Fe3S4 or Pt-Fe3S4 nanocatalysts loaded FTO glasses were used as the cathode, and Pt foil was used as the anode. The electrochemical measurements were conducted with a VMP3 Multi-channel potentiostat from Biologic.

NO quantification

For NO quantification, an external standard curve was first obtained using DEA NONOate. DEA NONOate provides 1.5 equivalents of NO with a 16 minute half-life31. 100 μL of DEA NONOate solutions with the concentration ranging from 0 μM to 400 μM was mixed with 100 μL of 600 μM DAF-FM in Tyrode’s solution in 96 well plates. Fluorescence of a DEA NONOate and DAF-FM reagent mixture was recorded over 4 hours until the fluorescence intensity reached a plateau (Supplementary Fig. 8). In order to capture the electrochemically generated NO, DAF-FM in Tyrode’s solution was directly added into the electrolyte solution, right after electrolysis.

Calculation methods for the diffusion profile of NO

We estimated the NO diffusion profiles through a simple diffusion-reaction model (Supplementary Figure 10, 11). The NO generated from the cathodes can be dissipated by its autooxidation processes27,28, and thus we considered the autooxidation process (equation 2,3) of NO in our model.

| (2) |

| (3) |

By combining the formation rate of NO at the electrode and its dissipation rate through autooxidation process, the overall diffusion equation can be described as follows:

| (4) |

| (5) |

| (6) |

| (7) |

Where k1= 2.9 × 106 M−2s−1, DNO = 2.21 × 10−5 cm2-s−1 46, and CO2 in water = 40 mg/L at 1 bar and 25°C. The diffusion profile of CNO (x, t) was calculated by solving equation (4) with boundary and initial conditions given by the experimental data (eq 5−7). In this calculation, we assumed NO diffused into the pure aqueous media from the electrode surface (x=0) into the bulk where the concentration was defined as zero (eq 4). We have defined our bulk at x=1000 μm and increasing this distance has little effect on the qualitative nature of these curves (this value ideally represents infinity but due to numerical constraints is set to an actual value). We also assume that the oxygen concentration is constant and at equilibrium with oxygen in the atmosphere.

Cell culture

The HEK 293FT cell was maintained in DMEM with 10 % fetal bovine serum (FBS). The HEK 293FT cell line was a gift from Feng Zhang (MIT). The cell line is negative for mycoplasma contamination, as confirmed by microscopic inspection. Before cell seeding, 3 × 5 mm glass coverslips (German Glass, Electron Microscopy) in each 24 well plate were coated with 20 μL of Matrigel® solution for 2 hours. For transfection, 1 μL of Lipofectamine® 2000 and 500 ng of total DNA in 50 μL of Opti-MEM were added to each well. pLenti-CaMKIIα-TRPV1-p2A-mCherry (developed in house38) and CMV-GCMAP6s were used for the transfection. CMV-GCaMP6s was a gift from Douglas Kim (Addgene plasmid # 40753). After 24 hours, calcium imaging experiments were performed with transfected cells on the coverslips. In the case of the primary rat hippocampal culture, hippocampi were carefully extracted from neonatal rat pups (P1), followed by a dissociation process with Papain (Worthington Biochemical). Before plating hippocampi, 3 × 5 mm glass coverslips in each 24 well plate were coated with 20 μL of Matrigel® solution. After 3 days, glia inhibition was conducted with a FUDR (5-fluoro−2’-deoxyuridine, F0503 Sigma Aldrich) solution. Viral transfections were conducted by adding 1 μL of the Lenti-CaMKIIα-TRPV1-p2A-mCherry (>109 transducing units/mL) and AAV9-hSyn::GCaMP6s (>1012 transducing units/mL) to each well on day 5 and day 7, respectively. AAV9-hSyn::GCaMP6s was a gift from Douglas Kim (Addgene viral prep # 100843-AAV9). Calcium imaging experiments of transfected neurons were conducted on day 14. Primary cultured cerebellar neurons were extracted from neonatal rat pups (P8) and then dissociated according to the previous reports32. Dissociated cerebellar neurons were plated onto either 35 mm tissue culture plates or 12 mm glass coverslips, which were pre-coated with Matrigel® solution. The seeding density was 5 × 105 cells/cm2. After 2 days, glial inhibition was conducted with a FUDR solution. The cerebellar neurons were maintained in neurobasal medium (Gibco) supplemented with B27 (Gibco), GlutaMAX(Gibco), and 25 mM KCl. All experiments in this work were approved by the MIT Committee on Animal Care.

in vitro calcium imaging experiments and GCaMP6s fluorescence analysis

For experiments involving the NO donor, HEK 293FT cells cultured on glass coverslips were each placed in 24 well plate, which contained 2 mL of Tyrode’s solution. Fluorescence changes in GCaMP6s were recorded with an inverted fluorescence microscope at a frame rate of 1 s. After 30 s of recording, 100 μL of Tyrode’s solution containing various concentrations of DEA NONOate was injected to each well plate. For in vitro validation of the electrochemical NO delivery system, Fe3S4 or Pt-Fe3S4 nanocatalysts deposited FTO electrodes (1 cm × 2 cm × 0.2 cm) and Pt electrode (Pt wire) were fixed inside each 24 well plate. After the fixation of two electrodes, 2 mL of Tyrode’s solution containing 0.1 M NaNO2 was added to each well plate. HEK 293FT cells or neurons cultured on glass coverslips were placed right next to the FTO electrode. After 30 s of recording, we started to apply various voltages from –1.25 V to –2.5 V vs Pt to the FTO electrodes using a Bipotentiostat SP−300 from Biologic. Constant voltages were applied until the end of the calcium imaging experiments. For experiments involving TRPV1 antagonist, HEK 293FT cells were incubated with 20 μM BCTC (≥98%, Sigma Aldrich) for 30 min prior to the calcium imaging experiments. Fluorescent intensity of each cell was analyzed with ImageJ and F0 value was calculated by averaging its fluorescent values during the initial 10 s of measurement. Averaged ΔF/F0 values were obtained utilizing 300 HEK 293FT cells or 100 neurons randomly selected from at least three independently performed tests.

Electrophysiology

Whole-cell patch-clamp recordings were performed with MultiClamp 700B amplifier and Digidata 1440A digitizer (Axon Instrument) at room temperature. The micropipettes were fabricated from borosilicate glass tubes (O.D.: 1.5 mm, I.D.: 0.86 mm, BF150−86−7.5, Shutter Instrument) with a flaming brown micropipette puller (P−80/PC, Shutter Instrument). The intracellular solution was comprised of 142 mM K-gluconate, 2 mM KCl, 0.2 mM ethylene glycol tetraacetic acid (EGTA), 4 mM MgATP, 10 mM HEPES, 7 mM Na2-phosphocreatine. The pH was adjusted to 7.4. The extracellular solution was comprised of 125 mM NaCl, 2 mM KCl, 2 mM MgCl2, 2 mM CaCl2, 25 mM HEPES, and 51 mM D-glucose. The pH was adjusted to 7.4. Cells were perfused with a gravity-fed perfusion system at a rate of 1−2 mL/min before stimulation. Pulse sequences were formed by a Digitizer through pClamp 10.2 (Molecular Devices). Signals were sampled at 10 kHz and were then low-pass filtered at 1 kHz. The total membrane capacitance was estimated from the surface area of the cell, according to the previous report47. Due to its short lifetime, NO donor was rapidly injected into the extracellular solution with gel-loading pipette tips (Fisher Scientific).

Measurement of cGMP levels in cultured cerebellar neurons

The cultured cerebellar neurons were first washed with pre-warmed Tyrode’s solution three times 8−9 days after seeding. To minimize the degradation of generated cGMP, neurons were then pre-incubated with Tyrode’s solution containing 200 μM 3-isobutylmethylxanthine, cGMP phosphodiesterase inhibitor, for 30 min before stimulation. After stimulation, the solutions were carefully removed, and then neurons were extracted utilizing a 0.1 M HCl solution for cGMP assay. cGMP levels in the cell lysates were analyzed using the cGMP enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) kit (Cayman chemical, no.581021) after the acetylation of samples.

Preform fabrication and fibre drawing

The macroscopic preforms were developed by machining two rectangular grooves of 1.5 mm × 1.5 mm on polycarbonate (PC; Ajedium Films) tube with inner and outer diameter of 3.175 mm and 9.525 mm respectively. This was followed by sequentially rolling additional sheets of PC, cyclic olefin copolymer (COC; TOPAS) and PC to yield a final overall preform diameter of ~ 12 mm. The preform was consolidated in a vacuum oven at 175 °C for 30 min. All the fibre drawing processes were conducted using a custom-built fibre drawing tower34. The fibres were drawn by placing the preform in a three-zone heating furnace, where the top, middle, and bottom zones were heated to 150 °C, 285 °C, and 110 °C, respectively. The preform was fed into the furnace at a rate of 1 mm/min and drawn at a speed of 900 mm/min, which resulted in a draw-down ratio of 30. A tungsten microwire (50 μm diameter, 99.95%, Goodfellow) and a gold-coated tungsten microwire (50 μm diameter, 0.5 μm Au coating, 99.95%, Goodfellow) were continuously fed into the preform during the draw.

Device connectorization

To establish electrical interfacing with embedded electrodes, the electrodes were exposed from the PC cladding with a sharp razor blade and then bonded to copper wires (40 AWG) with two-part silver epoxy (Epotek). The wires were then soldered to Mill-Max male pin connectors. For interfacing with the central microfluidic channel, the fibre was inserted into a 0.5 mm diameter ethylene-vinyl acetate tubing and sealed with UV-curable epoxy. Finally, the entire pin connector and fluidic interface region of the fibre probe was coated with 5-min epoxy (Devcon) for mechanical stability and electrical insulation. Then, 300 μm of embedded microwire was exposed from the tip of the fibre with a sharp razor blade. Pt-Fe3S4 nanocatalysts were then deposited onto the exposed gold-coated tungsten microwire utilizing the same method for depositing the nanocatalysts onto the FTO electrode. Lastly, Pt was electrodeposited on the tungsten microwire by continuous cycling the voltage from –1.2 V to 0 V vs Pt (Supplementary Fig. 19)36. After ten consecutive scans, the fibre was gently rinsed with de-ionized water and then dried in an oven. The thickness of the deposited Pt layer is approximately a fraction of a micron.

Injection of virus solutions into mouse brain

All in vivo studies were approved by the MIT Committee on Animal Care and performed according to the National Institutes of Health Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals. Male C57BL/6 mice (Jackson Laboratory) aged 8 weeks were utilized and all surgeries were conducted under aseptic conditions. Mice were anesthetized with isoflurane (0.5−2.5 % in O2) with a rodent anesthesia machine (VET EQUIP). Anesthetized mice were positioned in a stereotaxic frame (David Kopf Instruments) and ophthalmic ointment was applied to the eyes. Skin incisions were then performed to expose and align the skull. Coordinates for the injection and implantation were established based on the Mouse Brain Atlas48. For c-fos quantification assays, 1.5 μL of Lentivirus solution (>109 transducing units/mL) (Lenti-CaMKIIα::TRPV1-p2A-mCherry or Lenti-CaMKIIα::mCherry) was injected into VTA (coordinates relative to bregma; −3.3 mm anteriorposterior (AP); −0.5 mm mediolateral (ML); and −4.4 mm dorsoventral (DV)48) using a microinjection apparatus (10 μL NanoFil Syringe, beveled 33-gauge needles facing the dorso-lateral side, UMP−3 Syringe pump, and controller Micro4, World Precision Instruments) at an infusion rate of 80 nL/min. For fibre photometry experiments, a mixture of 1.4 μL of Lentivirus solution (>109 transducing units/mL) (Lenti-CaMKIIα::TRPV1-p2A-mCherry or Lenti-CaMKIIα::mCherry) and 0.7 μL of AAV solution (>1012 transducing units/mL) (AAV9-hSyn::GCaMP6s) were injected into the VTA. After injection, the syringe was lifted by 0.1 mm from the initial coordinates and remained at least 10 min before a slow withdrawal. After injection, skin tissue was sutured and the mice recovered on a heating pad. During surgery, all the mice were given a subcutaneous injection of buprenorphine (0.05 mg/kg). Recovered mice were maintained at a 12-h light/dark cycle and provided with water and food ad libitum.

Implantation of NO-delivery fibre and fibre optic cannula into mouse brain

Implantation of the NO-delivery fibre was conducted after 6−8 weeks of virus injection to allow for sufficient viral expression. Mice were anesthetized and positioned in a stereotaxic frame as described previously35. For c-fos quantification assays, NO-delivery fibres were implanted into the VTA coordinates. The fibres were firmly fixed to the skull with three layers of adhesive (C&B Metabond; Parkell) and dental cement (Jet-Set 4, Lang Dental). For fibre photometry experiments, fibre optic cannula (∅ 2.5 mm ceramic ferrule, ∅ 400 μm core, 0.50 NA, length = 10 mm, Thorlabs) was additionally implanted into NAc coordinates (1.25 mm AP; −0.75 mm ML, −3.9 mm DV48) after the implantation of the NO-delivery fibres in VTA. The cannula was also fixed to the skull with the adhesive and dental cement. After implantation and fixation, the remaining exposed skull was fully covered with the adhesive and dental cement. All the mice were given a subcutaneous injection of buprenorphine (0.05 mg/kg) during surgery, followed by the recovery process on a heating pad.

In vivo NO delivery for immunohistochemistry and fibre photometry analyses

After implantation and recovery processes, mice were anesthetized through an intraperitoneal (IP) injection of ketamine (100mg/kg) and xylazine (10mg/kg) mixture in saline and transferred to NO generation setup. First, 3 μL of NaNO2 containing Tyrode’s solution was injected through microfluidic channels into the mouse brain at an infusion rate of 500 nL/min. Then, the mice were subjected to the NO generation by applying –2.5 V vs Pt to the cathode for 5 min with the Bipotentiostat SP−300 from Biologic. To ensure sufficient delivery of NaNO2, 3 μL of the same NaNO2 solution was additionally injected during the NO generation at an infusion rate of 500 nL/min. In the case of the control group where TRPV1- mice were subjected to NO stimulation, an identical NO generation method was used. For the control groups without NO generation, only an injection of the NaNO2 solution was performed to TRPV1+ mice without applying the voltages or only application of voltages to the cathodes (−2.5 V vs Pt, 5 min) was performed to TRPV1- mice without NaNO2 injection. After NO delivery or control experiments, all the mice kept in their home cages for 60 min to allow for c-fos expression. For fibre photometry analyses, 3 μL of NaNO2 containing Tyrode’s solution was injected through microfluidic channels into the mouse brain at an infusion rate of 500 nL/min before NO generation. Next, the following applied voltages and electrolysis times were applied to the cathode in a sequential manner; –1.5 V for 60 s, 0 V for 30 s, –2.0 V for 60 s, 0 V for 30 s, –2.5 V for 60 s, 0 V vs Pt for 30 s. At the same time, 3 μL of the same NaNO2 solution was additionally injected at an infusion rate of 500 nL/min. Detailed methods for immunohistochemistry and fibre photometry analyses can be found in Supplementary Methods.

Data availability

The data that support the plots within this paper and other findings of this study are available from the corresponding authors upon reasonable request.

Code Availability

All scripts are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank D. Kim and F. Zhang for the generous gifts of the plasmids and cell lines. This work was funded in part by the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke (5R01NS086804) and the National Institutes of Health (NIH) BRAIN Initiative (1R01MH111872). This work made use of the MIT MRSEC Shared Experimental Facilities under award number DMR−14−19807 from the National Science Foundation (NSF). Funding for this research was also provided by the Department of Chemical Engineering at MIT. J.P. is a recipient of scholarship from the Kwanjeong Educational Foundation. J.H.M and Z.J.S are supported by NSF Graduate Research Fellowships under Grant number 1122374.

Footnotes

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Additional Information

Supplementary information is available in the online version of the paper. Reprints and permission information is available online at www.nature.com/reprints.

References

- 1.Bredt DS & Snyder SH NITRIC OXIDE: A Physiologic Messenger Molecule. Annu. Rev. Biochem 63, 175–195 (1994). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mustafa AK, Gadalla MM & Snyder SH Signaling by gasotransmitters. Sci. Signal 2, (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Yoshida T et al. Nitric oxide activates TRP channels by cysteine S-nitrosylation. Nat. Chem. Biol 2, 596 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lundberg JO, Weitzberg E & Gladwin MT The nitrate-nitrite-nitric oxide pathway in physiology and therapeutics. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov 7, 156–167 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Calabrese V et al. Nitric oxide in the central nervous system: neuroprotection versus neurotoxicity. Nat. Rev. Neurosci 8, 766 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Huang Z et al. Effects of cerebral ischemia in mice deficient in neuronal nitric oxide synthase. Science (80−. ) 265, 1883 LP–1885 (1994). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Liu VWT & Huang PL Cardiovascular roles of nitric oxide: A review of insights from nitric oxide synthase gene disrupted mice†. Cardiovasc. Res 77, 19–29 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Yoshida T, Limmroth V, Irikura K & Moskowitz MA The NOS Inhibitor, 7-Nitroindazole, Decreases Focal Infarct Volume but Not the Response to Topical Acetylcholine in Pial Vessels. J. Cereb. Blood Flow Metab 14, 924–929 (1994). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wang PG et al. Nitric Oxide Donors: Chemical Activities and Biological Applications. Chem. Rev 102, 1091–1134 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jen MC, Serrano MC, Van Lith R & Ameer GA Polymer-based nitric oxide therapies: Recent insights for biomedical applications. Adv. Funct. Mater 22, 239–260 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Xiang HJ, Guo M & Liu JG Transition-Metal Nitrosyls for Photocontrolled Nitric Oxide Delivery. Eur. J. Inorg. Chem 2017, 1586–1595 (2017). [Google Scholar]

- 12.Feelisch M The use of nitric oxide donors in pharmacological studies. Naunyn. Schmiedebergs. Arch. Pharmacol 358, 113–122 (1998). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Miller MR & Megson IL Recent developments in nitric oxide donor drugs. Br. J. Pharmacol 151, 305–321 (2007). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zhou EY et al. Near-Infrared Photoactivatable Nitric Oxide Donors with Integrated Photoacoustic Monitoring. J. Am. Chem. Soc 140, 11686–11697 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Suchyta DJ & Schoenfisch MH Controlled Release of Nitric Oxide from Liposomes. ACS Biomater. Sci. Eng 3, 2136–2143 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Simon J & Klotz MG Diversity and evolution of bioenergetic systems involved in microbial nitrogen compound transformations. Biochim. Biophys. Acta - Bioenerg 1827, 114–135 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Einsle O et al. Structure of cytochrome c nitrite reductase. Nature 400, 476–480 (1999). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tocheva EI, Rosell FI, Mauk AG & Murphy MEP Side-On Copper-Nitrosyl Coordination by Nitrite Reductase. Science (80−. ). 304, 867–870 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rosca V, Duca M, de Groot MT & Koper MTM ChemInform Abstract: Nitrogen Cycle Electrocatalysis. ChemInform 40, 2209–2244 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Joo J et al. Generalized and facile synthesis of semiconducting metal sulfide nanocrystals. J. Am. Chem. Soc 125, 11100–11105 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gadde RR & Bruckenstein S The electroduction of nitrite in 0.1 M HClO4 at platinum. J. Electroanal. Chem 50, 163–174 (1974). [Google Scholar]

- 22.Savannah W, Company R & River S Electrochemical reduction of nitrates and nitrites in alkaline nuclear waste solutions. J. Appl. Electrochem 26, 1–9 (1996). [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bard Allen J., Parsons Roger, J. J. Standard Potentials in Aqueous Solution. (1985).

- 24.Kojima H et al. Fluorescent Indicators for Imaging Nitric Oxide Production. Angew. Chemie Int. Ed 38, 3209–3212 (1999). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Eberhardt M et al. H2S and NO cooperatively regulate vascular tone by activating a neuroendocrine HNO-TRPA1-CGRP signalling pathway. Nat. Commun 5, (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Thomas DD, Liu X, Kantrow SP & Lancaster JR The biological lifetime of nitric oxide: Implications for the perivascular dynamics of NO and O<sub>2</sub> Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci 98, 355 LP–360 (2001). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Goldstein S & Czapski G Mechanism of the Nitrosation of Thiols and Amines by Oxygenated •NO Solutions: the Nature of the Nitrosating Intermediates. J. Am. Chem. Soc 118, 3419–3425 (1996). [Google Scholar]

- 28.Goldstein S & Czapski G Kinetics of Nitric Oxide Autoxidation in Aqueous Solution in the Absence and Presence of Various Reductants. The Nature of the Oxidizing Intermediates. J. Am. Chem. Soc 117, 12078–12084 (1995). [Google Scholar]

- 29.Miyamoto T, Dubin AE, Petrus MJ & Patapoutian A TRPV1 and TRPA1 Mediate Peripheral Nitric Oxide-Induced Nociception in Mice. PLoS One 4, e7596 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Valenzano KJ et al. <em>N</em>-(4-Tertiarybutylphenyl)−4-(3-chloropyridin−2-yl)tetrahydropyrazine −1(2<em>H</em>)-carbox-amide (BCTC), a Novel, Orally Effective Vanilloid Receptor 1 Antagonist with Analgesic Properties: I. In Vitro Characterization. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther 306, 377 LP–386 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Jaffrey SR, Erdjument-Bromage H, Ferris CD, Tempst P & Snyder SH Protein S-nitrosylation: a physiological signal for neuronal nitric oxide. Nat. Cell Biol 3, 193 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hermenegildo C et al. Chronic hyperammonemia impairs the glutamate–nitric oxide–cyclic GMP pathway in cerebellar neurons in culture and in the rat in vivo. Eur. J. Neurosci 10, 3201–3209 (1998). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hardingham N, Dachtler J & Fox K The role of nitric oxide in pre-synaptic plasticity and homeostasis. Frontiers in Cellular Neuroscience 7, 190 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Canales A et al. Multifunctional fibers for simultaneous optical, electrical and chemical interrogation of neural circuits in vivo. Nat. Biotechnol 33, 277 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Park S et al. One-step optogenetics with multifunctional flexible polymer fibers. Nat. Neurosci 20, 612 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Stoychev D, Papoutsis A, Kelaidopoulou A, Kokkinidis G & Milchev A Electrodeposition of platinum on metallic and nonmetallic substrates - Selection of experimental conditions. Mater. Chem. Phys 72, 360–365 (2001). [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lammel S et al. Input-specific control of reward and aversion in the ventral tegmental area. Nature 491, 212 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Chen R, Romero G, Christiansen MG, Mohr A & Anikeeva P Wireless magnetothermal deep brain stimulation. Science (80−. ). 1261821 (2015). doi: 10.1126/science.1261821 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Gunaydin LA et al. Natural Neural Projection Dynamics Underlying Social Behavior. Cell 157, 1535–1551 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Nugent FS, Penick EC & Kauer JA Opioids block long-term potentiation of inhibitory synapses. Nature 446, 1086 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Iravani MM, Kashefi K, Mander P, Rose S & Jenner P Involvement of inducible nitric oxide synthase in inflammation-induced dopaminergic neurodegeneration. Neuroscience 110, 49–58 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sagar SM, Sharp FR & Curran T Expression of c-fos protein in brain: metabolic mapping at the cellular level. Science (80−. ). 240, 1328 LP–1331 (1988). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Christoph GR, Leonzio RJ & Wilcox KS Stimulation of the lateral habenula inhibits dopamine-containing neurons in the substantia nigra and ventral tegmental area of the rat. J. Neurosci 6, 613 LP–619 (1986). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Monai H et al. Calcium imaging reveals glial involvement in transcranial direct current stimulation-induced plasticity in mouse brain. Nat. Commun 7, 11100 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

References

- 45.Furchgott RF & Jothianandan D Endothelium-Dependent and -Independent Vasodilation Involving Cyclic GMP: Relaxation Induced by Nitric Oxide, Carbon Monoxide and Light. J. Vasc. Res 28, 52–61 (1991). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Zacharia IG & Deen WM Diffusivity and solubility of nitric oxide in water and saline. Ann. Biomed. Eng 33, 214–222 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Gentet LJ, Stuart GJ & Clements JD Direct Measurement of Specific Membrane Capacitance in Neurons. Biophys. J 79, 314–320 (2000). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Franklin KBJ & Paxinos G The mouse brain in stereotaxic coordinates. 3, (Academic press; New York:, 2008). [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the plots within this paper and other findings of this study are available from the corresponding authors upon reasonable request.