Abstract

Background:

Adult survivors of childhood osteosarcoma and Ewing sarcoma are at risk of developing therapy-related chronic health conditions. We characterized the cumulative burden of chronic conditions and health status of survivors of childhood bone sarcomas.

Methods:

Survivors (n=207) treated between 1964 and 2002 underwent comprehensive clinical assessments (history/physical examination, laboratory analysis, physical and neurocognitive testing) and were compared to community controls (n=272). Health conditions were defined and graded according to a modified version of the National Cancer Institute’s Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events and the cumulative burden estimated.

Results:

Osteosarcoma and Ewing sarcoma survivors (median age 13.6 years at diagnosis [range 1.7–24.8]; age at evaluation 36.6 years [20.7–66.4]) demonstrated an increased prevalence of cardiomyopathy (14.5%, p<0.005) compared to controls. Nearly 30% of osteosarcoma survivors had evidence of hypertension. By age 35 years, osteosarcoma and Ewing sarcoma survivors had, on average, 12.0 (95% CI:10.2–14.2) and 10.6 (8.9–12.6) grade 1–4 conditions and 4.0 (3.2–5.1) and 3.5 (2.7–4.5) grade 3–4 conditions, respectively, compared to controls (3.3 [2.9–3.7] grade 1–4 and 0.9 [0.7–1.0] grade 3–4). Both survivor cohorts exhibited impaired 6-minute walk test, walking efficiency, mobility, strength and endurance (p<0.0001). Accumulation of ≥4 grade 3–4 chronic conditions was associated with deficits in executive function (relative risk[RR]: osteosarcoma 1.6[1.0–2.4], p=0.049; Ewing sarcoma 2.0[1.2–3.3], p=0.01) and attention (RR: osteosarcoma 2.3[1.2–4.2], p=0.008).

Conclusions:

Survivors of osteosarcoma and Ewing sarcoma experience a high cumulative burden of chronic health conditions, with impairments of physical function and neurocognition.

Impact:

Early intervention strategies may ameliorate the risk of co-morbidities in bone sarcoma survivors.

Keywords: osteosarcoma, Ewing sarcoma, survivorship, chronic health conditions, cumulative burden

INTRODUCTION

Improvements in therapies for childhood cancer have increased the number of survivors living decades beyond treatment. However, improved survival has also revealed the long-term sequelae of cancer therapy, impacting every organ system and contributing to substantial morbidity and premature mortality. By age 45 years, 95.5% of survivors of childhood cancer will have at least one chronic health condition and 80.5% a serious or life-threatening disorder.1

Adjuvant chemotherapy and aggressive local control measures are credited with improving survival rates for children and adolescents diagnosed with osteosarcoma and Ewing sarcoma from less than 20% to 65–75% for localized disease over the past five decades.2, 3 Survivors, however, experience significant risks for chronic health conditions related to prior therapeutic exposures. Historical regimens have been associated with cardiac, pulmonary, and neurocognitive morbidities,4, 5 as well as risk of secondary neoplasms.6 In addition, the predilection of bone sarcomas for extremity sites requiring limb-salvage surgery or amputation has implications for long-term physical performance deficits.7

Ascertainment of health outcomes among bone sarcoma survivors has largely relied upon registry and self-reported data.5, 8, 9 Such investigations may be limited by an inability to uniformly define responses as well as assess and validate significant findings. In addition, discordance between patient-reported and provider-assessed physical performance raises concern that survivors may underestimate measurable deficits in function.10 A comprehensive understanding of disease burden will inform and guide appropriate screening and care for this aging population. Our aim was to comprehensively characterize the cumulative burden and prevalence of chronic health conditions as well as physical and neurocognitive performance among adult survivors of childhood osteosarcoma and Ewing sarcoma.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study population

Participants included survivors of osteosarcoma and Ewing sarcoma enrolled in the St. Jude Lifetime Cohort (SJLIFE), an ongoing study to facilitate prospective medical assessment of health outcomes among survivors of childhood cancer.11 Eligibility included treatment at St. Jude Children’s Research Hospital (SJCRH) and, for this analysis, current age ≥18 years and ≥10 years from cancer diagnosis. Medical records were abstracted for therapeutic exposures, including surgeries and cumulative doses of chemotherapy and radiation (from diagnosis to present). A community-control group (n=272) was recruited from friends and non-first-degree relatives of SJCRH patients. The protocol was approved by the Institutional Review Board and was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and Good Clinical Practices as per the International Conference on Harmonization. Survivors and controls provided written informed consent for participation and release of medical records to validate and grade the severity of conditions diagnosed prior to or at the SJLIFE study assessment.

Survivors and controls completed a comprehensive clinical assessment on the SJCRH campus that included: a history and standardized physical examination, core laboratory battery, questionnaires detailing sociodemographic details, testing of neurocognitive and physical performance, and risk-based diagnostic studies according to the Children’s Oncology Group’s Long-Term Follow-Up Guidelines for Survivors of Childhood, Adolescent, and Young Adult Cancers.1, 12 Assessments were identical for survivors and controls except hearing loss (self-reported by controls), bone mineral density (BMD, assessed by dual-energy x-ray absorptiometry in survivors), and semen analysis (offered only to survivors). BMD was incorporated into cumulative burden analysis by multiple imputation using robust population-based normative data.13 Oligospermia/azoospermia were not included in the cumulative burden.

Outcomes

Chronic health conditions were classified using a modified version of the National Cancer Institute (NCI) Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events (CTCAE) v.4.03.14 The cumulative burden of grades 1–4 and 3–4 chronic conditions was calculated from the mean cumulative count of recurrent and multiple health conditions, as previously described.15, 16 Prevalence was assessed for conditions most commonly reported among survivors including: cardiovascular (cardiomyopathy, hypertension, myocardial infarction, hypercholesterolemia), neurologic (peripheral motor and sensory neuropathy), chronic kidney disease, musculoskeletal (decreased BMD, scoliosis, prosthetic malfunction), sensorineural hearing loss, pulmonary [abnormal forced expiratory volume in one second (FEV1), total lung capacity (TLC), diffusing capacity of lung for carbon monoxide corrected for hemoglobin (DLCOcorr)], endocrine (abnormal fasting glucose, overweight/obesity), and reproductive [sex hormone insufficiency (central hypogonadism defined by deficits in luteinizing hormone (LH)/follicle stimulating hormone (FSH), premature ovarian insufficiency (POI) in females, and Leydig cell failure in males),1, 17, 18 oligospermia/azoospermia]. Conditions were categorized as mild (grade 1), moderate (grade 2), severe/disabling (grade 3), or life-threatening (grade 4).14 BMD was assessed using T-scores based on population norms.13 POI was diagnosed in female survivors with delayed/interrupted puberty or amenorrhea >5 years after therapy and <40 years of age. In amenorrheic women <40 years not on hormonal treatments, serum estadriol <17 pg/mL and FSH >30 IU/L were considered indicative of POI.19 Leydig cell failure was diagnosed in male survivors on sex-hormone replacement therapy or serum total testosterone <250 ng/dL and LH >9.85 IU/L if untreated.20

Six functional domains were measured: aerobic function [6-minute walk test, walking efficiency ((maximum heart rate – resting heart rate)/distance walked in six minutes)], mobility (Timed Up and Go test), strength (hand grip, peak isokinetic torque of quadriceps at 60°/sec), muscular endurance (peak isokinetic torque of quadriceps at 300°/sec), flexibility (sit and reach test, ankle dorsiflexion), and balance (sensory organization test, vestibular score) by clinically trained exercise physiologists.21 (Supplemental Table 1) Physical function impairment was defined as >1.5 standard deviations (SD) below the age-, sex-matched z-score for controls; subjects who were unable to complete tests due to physical limitations were considered impaired. Participants self-reported their frequency of exercise within 180 days of assessment; physically active was defined as ≥150 minutes/week of moderate activity (with vigorous activity counted as 1.67 times moderate activity) per CDC guidelines.22

For survivors and controls, neurocognitive function was assessed in three domains: attention, executive function, and memory.23–26 Three neurocognitive measures were analyzed for each domain; for each measure impairment was defined as ≥1 and <2 standard deviations (SD) (mild, Grade 1), ≥2 and <3 SD (moderate, Grade 2), and ≥3 SD (severe, Grade 3) below the mean age-adjusted general population normative Z-scores. The highest grade among the three measures was used as the domain grade. Survivors with a history of neurodevelopmental disorder, neurologic event unrelated to cancer, or non-primary English language status were not evaluated (n=31).

Statistical Analysis

Two-sample t-tests and χ2 statistics were used to compare demographic and treatment-related characteristics between survivors and controls and between participating and non-participating survivors.

Mean cumulative count of recurrent/multiple health events was calculated by organ system as a measure of overall cumulative burden of chronic conditions.15, 16 The age-specific cumulative burden and 95% confidence intervals (CI) were estimated by summarizing chronic health conditions occurring per survivor and community control using the bootstrap percentile method.27 The prevalence of physical function impairments was compared to controls using χ2 or Fisher exact tests. Modified Poisson regression28 was used to estimate relative risks of neurocognitive impairments associated with prevalence of chronic conditions, adjusted for age, sex, and age at diagnosis.

The standardized incidence ratios (SIRs) of observed-to-expected secondary neoplasms used age, sex, and calendar year-specific cancer incidence from the NCI’s Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results program. Person-years at risk for secondary neoplasms were calculated 5 years from initial cancer diagnosis to subsequent neoplasm, death or last contact, whichever occurred first. SAS version 9.4 and R version 3.4.3 were used for all statistical analyses.

RESULTS

Among 298 survivors of osteosarcoma or Ewing sarcoma eligible for participation, 207 (69.5%) returned for an on-campus clinical assessment (osteosarcoma, n=117; Ewing sarcoma, n=90). An additional 22 (7.4%) agreed but had not yet returned, 16 (5.4%) completed a survey only, 10 (3.3%) could not be located and 43 (14.4%) declined participation (Supplemental Figure 1). No significant differences were identified between participating and non-participating survivors on clinical or demographic characteristics; some observed therapeutic differences were likely related to historical changes in initial and/or relapsed therapies over time (Supplemental Table 2).

Survivors’ initial diagnoses extended from 1964 to 2002. Both survivor cohorts were over 50% male with a median age at diagnosis in the adolescent years (osteosarcoma 13.8 years [range 3.2–23.6]; Ewing sarcoma 13.3 years [1.7–24.8]); the overall median age at evaluation was 36.6 years (osteosarcoma 37.6 years [20.8–65.1]; Ewing sarcoma 34.2 [20.7–66.4]) (Table 1). Compared to controls (median age 34.6 years [18.1–70]), osteosarcoma survivors were slightly older (p=0.033) and more racially diverse (p=0.025); they were also less likely to be married (p=0.03) or have full-time employment at the time of assessment (p=0.047).

Table 1.

Characteristics of study osteosarcoma, Ewing sarcoma survivors and community controls.

| Osteosarcoma (N=117) |

Ewing Sarcoma (N=90) |

Controls (N=272) |

OS vs. Control | EWS vs. Control | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | (%) | N | (%) | N | (%) | (p) | (p) | |

| Male | 63 | (53.8) | 53 | (58.9) | 130 | (47.8) | 0.27 | 0.068 |

| Female | 54 | (46.2) | 37 | (41.1) | 142 | (52.2) | ||

| Race | ||||||||

| White | 92 | (78.6) | 85 | (94.4) | 238 | (87.5) | 0.025 | 0.065 |

| Other | 25 | (21.4) | 5 | (5.6) | 34 | (12.5) | ||

| Age (years) | ||||||||

| Diagnosis | ||||||||

| 0–9 | 19 | (16.2) | 30 | (33.3) | ||||

| 10–18 | 89 | (76.1) | 46 | (51.1) | ||||

| ≥18 | 9 | (7.7) | 14 | (15.6) | ||||

| Evaluation | ||||||||

| ≤29 | 27 | (23.1) | 26 | (28.9) | 88 | (32.4) | 0.033 | 0.86 |

| 30–39 | 37 | (31.6) | 33 | (36.7) | 102 | (37.5) | ||

| 40–49 | 39 | (33.3) | 21 | (23.3) | 58 | (21.3) | ||

| ≥50 | 14 | (12.0) | 10 | (11.1) | 24 | (8.8) | ||

| Time since diagnosis (years) | ||||||||

| ≤19 | 38 | (32.5) | 36 | (40.0) | ||||

| 20–29 | 44 | (37.6) | 36 | (40.0) | ||||

| ≥30 | 35 | (29.9) | 18 | (20.0) | ||||

| Education | ||||||||

| <12 years | 8 | (6.8) | 9 | (10.0) | 12 | (4.4) | 0.60 | 0.11 |

| High school/GED | 21 | (18.0) | 15 | (16.7) | 46 | (16.9) | ||

| Vocational training | 6 | (5.1) | 6 | (6.7) | 7 | (2.6) | ||

| Some College | 37 | (31.6) | 19 | (21.1) | 83 | (30.5) | ||

| College graduate | 29 | (24.8) | 26 | (28.9) | 83 | (30.5) | ||

| Postgraduate | 16 | (13.7) | 15 | (16.7) | 41 | (15.1) | ||

| Employment | ||||||||

| Full-time | 65 | (55.6) | 58 | (64.4) | 180 | (66.2) | 0.047* | 0.76* |

| Part-time | 6 | (5.1) | 8 | (8.9) | 33 | (12.1) | ||

| Unemployed | 36 | (30.8) | 21 | (23.3) | 45 | (16.5) | ||

| Student/Homemaker | 10 | (8.5) | 3 | (3.3) | 14 | (5.1) | ||

| Health Insurance | ||||||||

| Insured | 97 | (82.9) | 73 | (81.1) | 230 | (84.6) | 0.68 | 0.44 |

| Uninsured | 20 | (17.1) | 17 | (18.9) | 42 | (15.4) | ||

| Marital Status | ||||||||

| Single/Never married | 35 | (30.2) | 20 | (22.2) | 57 | (21.0) | 0.030 | 0.96 |

| Married/Living with partner | 63 | (54.3) | 61 | (67.8) | 186 | (68.4) | ||

| Separated/Divorced/Widowed | 18 | (15.5) | 9 | (10.0) | 29 | (10.7) | ||

| Independently Living | ||||||||

| Yes | 100 | (85.5) | 81 | (90.0) | 234 | (86.0) | 0.89 | 0.33 |

| No | 17 | (14.5) | 9 | (10.0) | 38 | (14.0) | ||

| Tobacco Use | ||||||||

| Current smoker | 32 | (27.4) | 19 | (21.1) | 55 | (20.2) | 0.30 | 0.92 |

| Past smoker | 17 | (14.5) | 13 | (14.4) | 44 | (16.2) | ||

| Never smoked | 68 | (58.1) | 58 | (64.4) | 173 | (63.6) | ||

| Primary Tumor Site | ||||||||

| Lower extremity | 101 | (86.3) | 28 | (31.1) | ||||

| Upper extremity | 10 | (8.5) | 8 | (8.9) | ||||

| Pelvis | 2 | (1.7) | 15 | (16.7) | ||||

| Axial non-pelvic | 4 | (3.4) | 39 | (43.3) | ||||

| Surgery | ||||||||

| Amputation | 81 | (69.2) | 10 | (11.1) | ||||

| Limb-sparing surgery | 31 | (26.5) | 10 | (11.1) | ||||

| Non-extremity surgery | 5 | (4.3) | 42 | (46.7) | ||||

| No surgery | 0 | (0.0) | 28 | (31.1) | ||||

| Thoracotomy/chest wall | 27 | (23.1) | 18 | (20.0) | ||||

| Chemotherapy | ||||||||

| Alkylating Agents | 109 | (93.2) | 90 | (100) | ||||

| Anthracyclines | 107 | (91.5) | 88 | (97.8) | ||||

| Methotrexate | 89 | (76.1) | 1 | (1.1) | ||||

| Cisplatin | 46 | (39.3) | 2 | (2.2) | ||||

| Carboplatin | 37 | (31.6) | 1 | (1.1) | ||||

| Etoposide | 2 | (1.7) | 36 | (40.0) | ||||

| Bleomycin | 15 | (12.8) | 0 | (0.0) | ||||

| Vincristine | 5 | (4.3) | 90 | (100) | ||||

| Radiation | ||||||||

| Pelvis | 0 | (0.0) | 27 | (30.0) | ||||

| Chest | 2 | (1.7) | 24 | (26.7) | ||||

| Brain/Cranium | 2 | (1.7) | 6 | (6.7) | ||||

Full-time vs. less than full-time

All osteosarcoma survivors had surgical resection with 69% undergoing amputation. Nearly all survivors (96%) were exposed to alkylating agents [cyclophosphamide equivalent dose; osteosarcoma median 7,817 mg/m2(range; 1,714–29,169); Ewing sarcoma median 21,183 mg/m2(5,301–36,965)] and anthracyclines [380 mg/m2(91–565) and 348 mg/m2(45–447), respectively] with the addition of high-dose methotrexate [107 gram/m2(25–212)] and heavy metals [cisplatin 400 mg/m2(100–562) or carboplatin 2,961 mg/m2(1,115–6,117)] for osteosarcoma survivors and epipodophyllotoxins [2,846 mg/m2(1,554–4,138)] and vinca alkaloids [11 mg/m2(2–54)] for Ewing sarcoma survivors (Supplemental Table 3). Nearly two-thirds of Ewing sarcoma survivors received radiation therapy to their primary tumor site.

Chronic Health Conditions

The cumulative burden of chronic health conditions for survivors was substantially elevated compared to controls across all age groups and organ systems (Figure 1; Supplemental Table 4a–d). By age 35 years, an osteosarcoma survivor was expected to accumulate, on average, 12.0 grade 1–4 conditions (95% CI:10.2–14.2) and 4.0 (95% CI:3.2–5.1) grade 3–4 conditions; and a Ewing sarcoma survivor 10.6 grade 1–4 (95% CI:8.9–12.6) and 3.5 (95% CI:2.7–4.5) grade 3–4 conditions. In contrast, similarly aged community controls were expected to accumulate an average of 3.3 (95% CI:2.9–3.7) grade 1–4 and 0.9 (95% CI:0.7–1.0) grade 3–4 conditions. Cumulative burden of cardiovascular and musculoskeletal conditions were particularly prominent (Figure 1), with at least 1 severe or life-threatening cardiovascular condition among every 4 survivors expected by age 35 (osteosarcoma 0.26, 95% CI:0.13–0.43; Ewing sarcoma 0.27, 95% CI:0.11–0.48) and at least one or more grade 3–4 musculoskeletal conditions expected per survivor [1.75 (95% CI:1.36–2.16) and 1.0 (95% CI:0.61–1.41)] among osteosarcoma and Ewing sarcoma, respectively.

Figure 1.

Cumulative burden and 95% confidence intervals of grade 1–4 and 3–4 overall chronic health conditions and cardiovascular and musculoskeletal conditions among survivors of osteosarcoma (a) and Ewing sarcoma (b).

The most prevalent chronic health conditions are shown in Tables 2a and 2b. Over 20% of osteosarcoma survivors had evidence of clinically significant cardiomyopathy (grades 2–4). The majority (61.5%) of this young adult population had evidence of hypertension, with 30% at levels indicating a need for anti-hypertensive medications (≥grade 2) versus 14.7% of controls. The prevalence of cardiomyopathy was lower among Ewing sarcoma survivors but still significantly elevated compared to controls (6.6% vs. 0.6%, p=0.004). Over 20% of osteosarcoma survivors had decreased FEV1 and DLCOcorr, compared to 7.4% and 4.8% in controls (p<0.001). Thoracotomy/chest wall surgery was associated with abnormal pulmonary function (p<0.001). Ewing sarcoma survivors had decreased FEV1 (20%), TLC (14.4%) and DLCOcorr (21.1%). On multivariate analysis, chest radiotherapy was associated with increased risk of abnormal pulmonary function; thoracotomy/chest wall surgery was associated with decreased lung capacity (Supplemental Table 5). While osteosarcoma survivors experienced higher rates of conditions associated with platinum exposure such as hearing loss (39.3% vs. 2.9%, p<0.001), chronic kidney disease (7.7% vs 1.1%, p=0.001), and peripheral sensory neuropathy (47.9% vs. 12.9%, p<0.001), they also demonstrated an increased prevalence of motor neuropathies (17% vs. 0%, p<0.001). Notably, more than one third of survivors had radiographic evidence of osteopenia (33.3% for both osteosarcoma and Ewing sarcoma) or osteoporosis (3.4% and 5.6% for osteosarcoma and Ewing sarcoma, respectively). Decreased BMD was more prevalent among osteosarcoma amputees (p=0.0008). A higher prevalence of sex hormone insufficiency was observed in both groups but only significantly higher among Ewing sarcoma survivors compared to controls (19.5% vs. 3.3%, p<0.0001). Among males evaluated by semen analysis, 45.9% (N=17/37) of osteosarcoma survivors and 89.5% (N=34/38) of Ewing sarcoma survivors had oligospermia/azoospermia. The prevalence of conditions such as diabetes, obesity, and hyperlipidemia were not increased compared to controls.

Table 2a.

Prevalence of chronic health conditions of survivors of osteosarcoma (OS) (N=117) and community controls (N=272).

| Cardiomyopathy | Hypertension | Myocardial infarction | Hypercholesterolemia | |||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OS Survivors | Controls | OS Survivors | Controls | OS Survivors | Controls | OS Survivors | Controls | |||||||||||||||||

| N | (%) | N | (%) | (p) | N | (%) | N | (%) | (p) | N | (%) | N | (%) | (p) | N | (%) | N | (%) | (p) | |||||

| Normal | 93 | (79.5) | 270 | (99.3) | <0.001 | 45 | (38.5) | 153 | (56.3) | 0.001 | 108 | (92.3) | 269 | (98.9) | 0.001 | 70 | (59.8) | 191 | (70.2) | 0.045 | ||||

| Grade 1 | 0 | (0) | 0 | (0) | 37 | (31.6) | 79 | (29.0) | 0 | (0) | 2 | (0.7) | 32 | (27.4) | 64 | (23.5) | ||||||||

| Grade 2 | 8 | (6.8) | 1 | (0.3) | 20 | (17.1) | 31 | (11.4) | 1 | (0.9) | 0 | (0) | 14 | (12.0) | 17 | (6.3) | ||||||||

| Grade 3 | 14 | (12.0) | 1 | (0.3) | 15 | (12.8) | 9 | (3.3) | 8 | (6.8) | 1 | (0.4) | 1 | (0.9) | 0 | (0) | ||||||||

| Grade 4 | 2 | (1.7) | 0 | (0) | 0 | (0) | 0 | (0) | 0 | (0) | 0 | (0) | 0 | (0) | 0 | (0) | ||||||||

| Hypertriglyceridemia | Peripheral Motor Neuropathy | Peripheral Sensory Neuropathy | Chronic Kidney Disease | |||||||||||||||||||||

| OS Survivors | Controls | OS Survivors | Controls | OS Survivors | Controls | OS Survivors | Controls | |||||||||||||||||

| N | (%) | N | (%) | (p) | N | (%) | N | (%) | (p) | N | (%) | N | (%) | (p) | N | (%) | N | (%) | (p) | |||||

| 88 | (75.2) | 219 | (80.5) | 0.25 | 97 | (82.9) | 272 | (100) | <0.001 | 61 | (52.1) | 237 | (87.1) | <0.001 | 108 | (92.3) | 269 | (98.9) | 0.001 | |||||

| Grade 1 | 21 | (18.0) | 42 | (15.4) | 8 | (6.8) | 0 | (0) | 48 | (41.0) | 30 | (11) | 0 | (0) | 0 | (0) | ||||||||

| Grade 2 | 8 | (6.8) | 10 | (3.7) | 10 | (8.5) | 0 | (0) | 6 | (5.1) | 5 | (1.8) | 7 | (6.0) | 3 | (1.1) | ||||||||

| Grade 3 | 0 | (0) | 1 | (0.3) | 2 | (1.7) | 0 | (0) | 2 | (1.7) | 0 | (0) | 2 | (1.7) | 0 | (0) | ||||||||

| Grade 4 | 0 | (0) | 0 | (0) | 0 | (0) | 0 | (0) | 0 | (0) | 0 | (0) | 0 | (0) | 0 | (0) | ||||||||

| Decreased Bone Mineral Density | Scoliosis | Prosthetic Malfunction‡ | Sensorineural Hearing Loss | |||||||||||||||||||||

| OS Survivors | Controls† | OS Survivors | Controls | OS Survivors | Controls | OS Survivors | Controls | |||||||||||||||||

| N | (%) | N | (%) | (p) | N | (%) | N | (%) | (p) | N | (%) | N | (%) | (p) | N | (%) | N | (%) | (p) | |||||

| Normal | 74 | (63.2) | -- | -- | -- | 96 | (82.0) | 271 | (99.6) | <0.001 | 19 | (41.3) | -- | -- | -- | 71 | (60.7) | 264 | (97.1) | <0.001 | ||||

| Grade 1 | 39 | (33.3) | -- | -- | 14 | (12.0) | 1 | (0.4) | 0 | (0) | -- | -- | 7 | (6.0) | 5 | (1.8) | ||||||||

| Grade 2 | 4 | (3.4) | -- | -- | 7 | (6) | 0 | (0) | 1 | (2.2) | -- | -- | 8 | (6.8) | 0 | (0) | ||||||||

| Grade 3 | 0 | (0) | -- | -- | 0 | (0) | 0 | (0) | 26 | (56.5) | -- | -- | 23 | (19.7) | 0 | (0) | ||||||||

| Grade 4 | 0 | (0) | -- | -- | 0 | (0) | 0 | (0) | 0 | (0) | -- | -- | 8 | (6.8) | 3 | (1.1) | ||||||||

| Abnormal FEV1 | Abnormal TLC | Abnormal DLCOcorr | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| OS Survivors | Controls | OS Survivors | Controls | OS Survivors | Controls | |||||||||||||||||||

| N | (%) | N | (%) | (p) | N | (%) | N | (%) | (p) | N | (%) | N | (%) | (p) | ||||||||||

| Normal | 89 | (76.1) | 252 | (92.6) | <0.001 | 110 | (94.0) | 265 | (97.4) | 0.14 | 91 | (77.8) | 259 | (95.2) | <0.001 | |||||||||

| Grade 1 | 16 | (13.7) | 12 | (4.4) | 2 | (1.7) | 6 | (2.2) | 0 | (0) | 12 | (4.4) | ||||||||||||

| Grade 2 | 8 | (6.8) | 5 | (1.8) | 2 | (1.7) | 1 | (0.3) | 25 | (21.4) | 1 | (0.3) | ||||||||||||

| Grade 3 | 2 | (1.7) | 3 | (1.1) | 3 | (2.6) | 0 | (0) | 1 | (0.9) | 0 | (0) | ||||||||||||

| Grade 4 | 2 | (1.7) | 0 | (0) | 0 | (0) | 0 | (0) | 0 | (0) | 0 | (0) | ||||||||||||

| Abnormal Fasting Glucose | Overweight/Obesity | Sex Hormone Insufficiency* | Oligospermia/Azoospermia** | |||||||||||||||||||||

| OS Survivors | Controls | OS Survivors | Controls | OS Survivors | Controls | OS Survivors | Controls† | |||||||||||||||||

| N | (%) | N | (%) | (p) | N | (%) | N | (%) | (p) | N | (%) | N | (%) | (p) | N | (%) | N | (%) | (p) | |||||

| Normal | 92 | (78.6) | 218 | (80.1) | 0.73 | 44 | (37.6) | 100 | (36.8) | 0.88 | 95 | (92.2) | 232 | (96.7) | 0.093 | 20 | (54.1) | -- | -- | -- | ||||

| Grade 1 | 22 | (18.8) | 43 | (15.8) | 0 | (0) | 0 | (0) | 0 | (0) | 0 | (0) | 0 | (0) | -- | -- | ||||||||

| Grade 2 | 2 | (1.7) | 10 | (3.7) | 36 | (30.8) | 69 | (25.4) | 4 | (3.9) | 0 | (0) | 8 | (21.6) | -- | -- | ||||||||

| Grade 3 | 1 | (0.9) | 1 | (0.4) | 31 | (26.5) | 78 | (28.7) | 4 | (3.9) | 8 | (3.3) | 9 | (24.3) | -- | -- | ||||||||

| Grade 4 | 0 | (0) | 0 | (0) | 6 | (5.1) | 25 | (9.2) | 0 | (0) | 0 | (0) | 0 | (0) | -- | -- | ||||||||

FEV1: forced expiratory volume in one second; TLC: total lung capacity; DLCOcorr: diffusion capacity of lungs for carbon monoxide corrected for hemoglobin

Not assessed among controls

Assessed among survivors with primary limb-sparing surgery (n=46)

Assessed among evaluable survivors (n=103) and controls (n=240); women above age of 40 years or actively receiving hormonal therapy were considered inevaluable

Assessed among male survivors who consented to semen analysis (n=37)

Table 2b.

Prevalence of chronic health conditions of survivors of Ewing sarcoma (EWS) (N=90) and community controls (N=272).

| Cardiomyopathy | Hypertension | Myocardial infarction | Hypercholesterolemia | |||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| EWS Survivors | Controls | EWS Survivors | Controls | EWS Survivors | Controls | EWS Survivors | Controls | |||||||||||||||||

| N | (%) | N | (%) | (p) | N | (%) | N | (%) | (p) | N | (%) | N | (%) | (p) | N | (%) | N | (%) | (p) | |||||

| Cardiovascular | Normal | 84 | (93.3) | 270 | (99.3) | 0.004 | 42 | (46.7) | 153 | (56.3) | 0.11 | 90 | (100) | 269 | (98.9) | 1.0 | 57 | (63.3) | 191 | (70.2) | 0.22 | |||

| Grade 1 | 0 | (0) | 0 | (0) | 36 | (40.0) | 79 | (29.0) | 0 | (0) | 2 | (0.7) | 29 | (32.2) | 64 | (23.5) | ||||||||

| Grade 2 | 3 | (3.3) | 1 | (0.3) | 11 | (12.2) | 31 | (11.4) | 0 | (0) | 0 | (0) | 4 | (4.4) | 17 | (6.3) | ||||||||

| Grade 3 | 3 | (3.3) | 1 | (0.3) | 1 | (1.1) | 9 | (3.3) | 0 | (0) | 1 | (0.3) | 0 | (0) | 0 | (0) | ||||||||

| Grade 4 | 0 | (0) | 0 | (0) | 0 | (0) | 0 | (0) | 0 | (0) | 0 | (0) | 0 | (0) | 0 | (0) | ||||||||

| Hypertriglyceridemia | Peripheral Motor Neuropathy | Peripheral Sensory Neuropathy | Chronic Kidney Disease | |||||||||||||||||||||

| EWS Survivors | Controls | EWS Survivors | Controls | EWS Survivors | Controls | EWS Survivors | Controls | |||||||||||||||||

| N | (%) | N | (%) | (p) | N | (%) | N | (%) | (p) | N | (%) | N | (%) | (p) | N | (%) | N | (%) | (p) | |||||

| Normal | 76 | (84.4) | 272 | (100) | 0.24 | Neurologic | 76 | (84.4) | 272 | (100) | <0.001 | 55 | (61.1) | 237 | (87.1) | <0.001 | Renal | 87 | (96.7) | 269 | (98.9) | 0.17 | ||

| Grade 1 | 8 | (8.9) | 0 | (0) | 8 | (8.9) | 0 | (0) | 29 | (32.2) | 30 | (11) | 1 | (1.1) | 0 | (0) | ||||||||

| Grade 2 | 6 | (6.7) | 0 | (0) | 6 | (6.7) | 0 | (0) | 4 | (4.4) | 5 | (1.8) | 2 | (2.2) | 3 | (1.1) | ||||||||

| Grade 3 | 0 | (0) | 0 | (0) | 0 | (0) | 0 | (0) | 2 | (2.2) | 0 | (0) | 0 | (0) | 0 | (0) | ||||||||

| Grade 4 | 0 | (0) | 0 | (0) | 0 | (0) | 0 | (0) | 0 | (0) | 0 | (0) | 0 | (0) | 0 | (0) | ||||||||

| Decreased Bone Mineral Density | Scoliosis | Prosthetic Malfunction‡ | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| EWS Survivors | Controls† | EWS Survivors | Controls | EWS Survivors | Controls | |||||||||||||||||||

| N | (%) | N | (%) | (p) | N | (%) | N | (%) | (p) | N | (%) | N | (%) | (p) | ||||||||||

| Normal | 55 | (61.1) | -- | 67 | (74.4) | 271 | (99.6) | <0.001 | 8 | (66.7) | -- | -- | -- | |||||||||||

| Grade 1 | 30 | (33.3) | -- | -- | 14 | (15.6) | 1 | (0.3) | 0 | (0) | -- | -- | ||||||||||||

| Grade 2 | 5 | (5.6) | -- | -- | 5 | (5.6) | 0 | (0) | 0 | (0) | -- | -- | ||||||||||||

| Grade 3 | 0 | (0) | -- | -- | 4 | (4.4) | 0 | (0) | 4 | (33.3) | -- | -- | ||||||||||||

| Grade 4 | 0 | (0) | -- | -- | 0 | (0) | 0 | (0) | 0 | (0) | -- | -- | ||||||||||||

| Abnormal FEV1 | Abnormal TLC | Abnormal DLCOcorr | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| EWS Survivors | Controls | EWS Survivors | Controls | EWS Survivors | Controls | |||||||||||||||||||

| N | (%) | N | (%) | (p) | N | (%) | N | (%) | (p) | N | (%) | N | (%) | (p) | ||||||||||

| Normal | 72 | (80.0) | 252 | (92.6) | 0.001 | 77 | (85.6) | 265 | (97.4) | <0.001 | 71 | (78.9) | 259 | (95.2) | <0.001 | |||||||||

| Grade 1 | 8 | (8.9) | 12 | (4.4) | 4 | (4.4) | 6 | (2.2) | 0 | (0) | 12 | (4.4) | ||||||||||||

| Grade 2 | 6 | (6.7) | 5 | (1.8) | 6 | (6.7) | 1 | (0.3) | 18 | (20.0) | 1 | (0.3) | ||||||||||||

| Grade 3 | 3 | (3.3) | 3 | (1.1) | 3 | (3.3) | 0 | (0) | 1 | (1.1) | 0 | (0) | ||||||||||||

| Grade 4 | 1 | (1.1) | 0 | (0) | 0 | (0) | 0 | (0) | 0 | (0) | 0 | (0) | ||||||||||||

| Abnormal Fasting Glucose | Overweight/Obesity | Sex Hormone Insufficiency* | Oligospermia/Azoospermia** | |||||||||||||||||||||

| EWS Survivors | Controls | EWS Survivors | Controls | EWS Survivors | Controls | EWS Survivors | Controls† | |||||||||||||||||

| N | (%) | N | (%) | (p) | N | (%) | N | (%) | (p) | N | (%) | N | (%) | (p) | N | (%) | N | (%) | (p) | |||||

| Normal | 68 | (75.6) | 218 | (80.1) | 0.35 | 33 | (36.7) | 100 | (36.8) | 0.99 | 66 | (80.5) | 232 | (96.7) | <0.001 | 4 | (10.5) | -- | -- | -- | ||||

| Grade 1 | 14 | (15.6) | 43 | (15.8) | 0 | (0) | 0 | (0) | 0 | (0) | 0 | (0) | 0 | (0) | -- | -- | ||||||||

| Grade 2 | 2 | (2.2) | 10 | (3.7) | 28 | (31.1) | 69 | (25.4) | 9 | (11.0) | 0 | (0) | 11 | (28.9) | -- | -- | ||||||||

| Grade 3 | 5 | (5.6) | 1 | (0.3) | 24 | (26.7) | 78 | (28.7) | 7 | (8.5) | 8 | (3.3) | 23 | (60.5) | -- | -- | ||||||||

| Grade 4 | 1 | (1.1) | 0 | (0) | 5 | (5.6) | 25 | (9.2) | 0 | (0) | 0 | (0) | 0 | (0) | -- | -- | ||||||||

FEV1: forced expiratory volume in one second; TLC: total lung capacity; DLCOcorr: diffusion capacity of lungs for carbon monoxide corrected for hemoglobin

Not assessed among controls

Assessed among survivors with primary limb-sparing surgery (n=12)

Assessed among evaluable survivors (n=82) and controls (n=240); women above age of 40 years or actively receiving hormonal therapy were considered inevaluable

Assessed among male survivors who consented to semen analysis (n=38)

Subsequent Neoplasms

At a median of 25 years (8.3–36.4) from diagnosis, ten (8.5%) osteosarcoma and five (5.5%) Ewing sarcoma survivors developed 18 total secondary neoplasms (SNs) (Supplemental Table 6). Osteosarcoma survivors had a 3-fold (SIR 3.3, 95% CI:1.6–6.0%) and Ewing sarcoma survivors a 4-fold (SIR 4.1, 95% CI:1.8–8.1) higher risk of SN compared to the general population. Of the eight secondary neoplasms diagnosed among five Ewing sarcoma survivors, 62.5% arose within or adjacent to prior radiation fields, including cases of papillary thyroid carcinoma and ductal breast carcinoma arising in patients who received lung and chest wall radiation.

Physical Performance

The physical performance of sarcoma survivors was significantly diminished compared to controls (Figure 2). Greater than half of all osteosarcoma survivors demonstrated impaired measures of aerobic function (six-minute walk test; 54.9%, 95% CI:45.2–64.2%; walking efficiency 38.4%, 95% CI:29.4–48.1%) and mobility (timed up and go test; 53.9%, 95% CI:44.4–63.2%) compared to controls (p<0.0001). More than a third demonstrated impaired lower extremity strength and endurance. More Ewing sarcoma survivors than controls were also impaired on aerobic function (six-minute walk test; 20.5%, p<0.0001) and mobility (19.3%, p<0.0001) and had significant deficits in lower extremity strength (32.1%), endurance (18.5%), and flexibility (sit and reach, 13.8%; passive dorsiflexion, 14.8%; active dorsiflexion, 19.3%). Decreased BMD was associated with decreased grip (p=0.005) and quadriceps strength (p=0.025).

Figure 2.

Prevalence of physical performance deficits among survivors of osteosarcoma (OS) and Ewing sarcoma (EWS).

Among osteosarcoma lower extremity amputees (n=73), 58 walked with a prosthesis; fifteen used a cane or crutches for support. Six of eight Ewing sarcoma lower extremity amputees used a prosthesis; 2 used crutches. Among survivors with limb-sparing procedures, all but one ambulated without assistive devices. Comparing by surgical procedure (Supplemental Table 7), osteosarcoma survivors with a primary pelvic resection or lower extremity amputation had worse performance than those with an upper extremity primary tumor or a lower extremity limb-sparing surgery on aerobic function (p<0.0001), mobility (p<0.0001), and walking efficiency (p=0.004), while those with a limb-sparing procedure had diminished lower extremity muscle strength (p=0.048). Among Ewing sarcoma survivors, no differences in physical performance were observed among surgical groups, likely due to use of definitive radiotherapy for pelvic and extremity tumors rather than aggressive surgical resection.

Adjusting for age, sex and body mass index, survivors of osteosarcoma (RR 1.64, 95% CI:1.32–2.04) and Ewing sarcoma (RR 1.47, 95% CI:1.14–1.91) were more likely than controls to be inactive. No associations between exercise frequency and musculoskeletal chronic conditions were observed. Among osteosarcoma survivors, physical inactivity was associated with impaired six-minute walk (p=0.014) and walking efficiency (p=0.01).

Neurocognitive Function

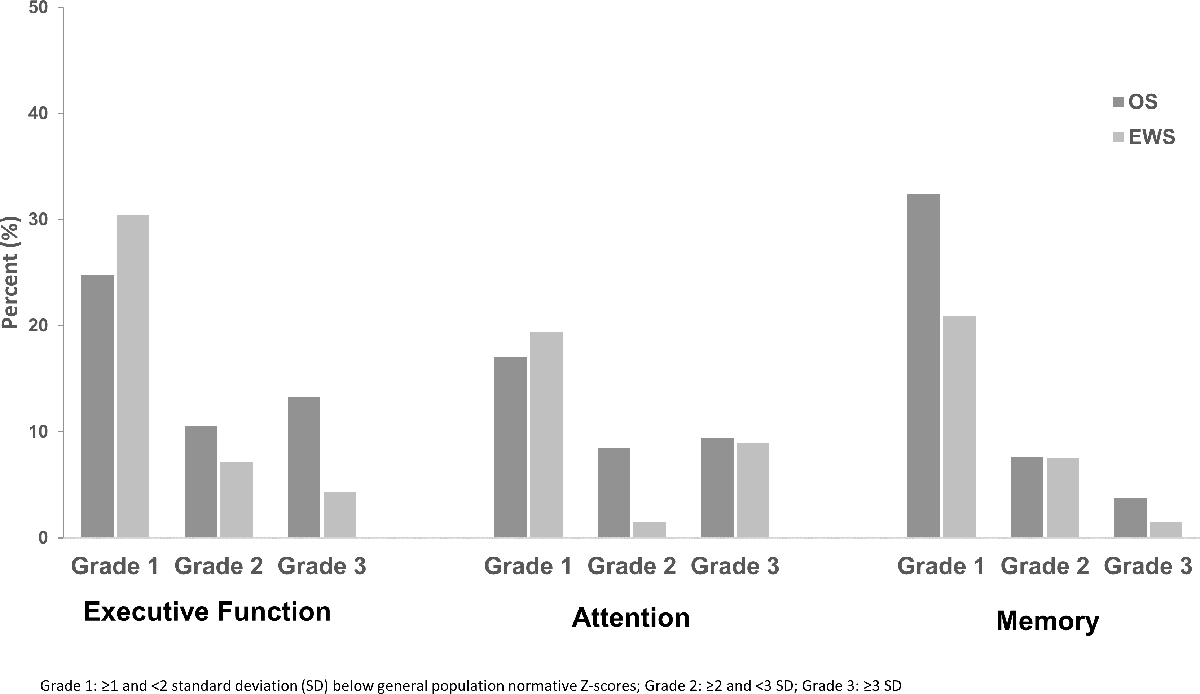

Among survivors with comprehensive neurocognitive testing (osteosarcoma=106, Ewing sarcoma=69), 48.6% of osteosarcoma survivors and 42% of Ewing sarcoma survivors had deficits in executive function (≥Grade 1), with moderate to severe (Grade 2–3) impairments in 23.8% and 11.6%, respectively. For attention, moderate to severe impairment (Grade 2–3) was identified in 17.9% and 10.5%, and memory impairment in 11.4% and 9.0%, respectively, of osteosarcoma and Ewing sarcoma survivors. Compared to controls (Figure 3), osteosarcoma survivors demonstrated higher rates of impaired executive function, particularly Grade 2–3 impairments (p<0.0001), as well as worse memory (p=0.043); no differences were observed between Ewing sarcoma survivors and controls. After adjustment for age and sex, hypertension (relative risk (RR) 2.0, 95% CI:1.2–3.3) and obesity (RR 1.9, 95% CI:1.1–3.1) were associated with increased risk of attention impairment in osteosarcoma survivors. Osteosarcoma survivors with 4 or more grade 3–4 conditions had a greater risk of impaired executive function (RR 1.6, 95% CI:1–2.4, p=0.049) and attention (RR 2.3, 95% CI:1.2–4.2, p=0.008) compared to survivors with ≤ 1 condition (Table 3). Ewing sarcoma survivors with 4 or more grade 3–4 conditions also had increased risk of impairment of executive function (RR 2.0, 95% CI:1.2–3.3, p=0.01).

Figure 3.

Neurocognitive impairment among survivors of osteosarcoma, Ewing sarcoma and controls.

Table 3.

Association of Grade 3–4 chronic health conditions with neurocognitive impairments.

| Predictor | Executive Function | Attention | Memory | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Osteosarcoma | RR | 95% CI | P | RR | 95% CI | P | RR | 95% CI | P |

| 0.94 | (0.64–1.4) | 0.77 | 0.9 | (0.53–1.5) | 0.68 | 0.97 | (0.63–1.5) | 0.89 | |

| Age at diagnosis (year) | 0.98 | (0.93–1.0) | 0.29 | 0.95 | (0.9–1.0) | 0.08 | 0.98 | (0.93–1.0) | 0.45 |

| Grade 3–4 CHCs | |||||||||

| 0–1 | 1 | -- | -- | 1 | -- | -- | 1 | -- | -- |

| 2 | 1.6 | (1.0–2.5) | 0.07 | 1.4 | (0.66–3.1) | 0.37 | 1.4 | (0.88–2.4) | 0.15 |

| 3 | 0.78 | (0.37–1.6) | 0.51 | 1.3 | (0.58–3.1) | 0.49 | 0.76 | (0.36–1.6) | 0.47 |

| ≥ 4 | 1.6 | (1–2.4) | 0.049 | 2.3 | (1.2–4.2) | 0.008 | 1.0 | (0.58–1.8) | 0.94 |

| Ewing Sarcoma | RR | 95% CI | P | RR | 95% CI | P | RR | 95% CI | P |

| Gender (female vs. male) | 1.0 | (0.6–1.7) | 0.95 | 0.92 | (0.43–2.0) | 0.82 | 1.4 | (0.68–2.9) | 0.37 |

| Age at diagnosis (year) | 1.1 | (1.0–1.1) | 0.02 | 1.0 | (1.0–1.1) | 0.49 | 1.0 | (0.94–1.1) | 0.66 |

| Grade 3–4 CHCs | |||||||||

| 0–1 | 1 | -- | -- | 1 | -- | -- | 1 | -- | -- |

| 2 | 0.89 | (0.42–1.9) | 0.76 | 1.2 | (0.48–3.1) | 0.67 | 1.1 | (0.43–2.6) | 0.92 |

| 3 | 0.38 | (0.06–2.4) | 0.30 | 0.57 | (0.09–3.8) | 0.56 | 1.1 | (0.33–3.7) | 0.87 |

| ≥ 4 | 2.0 | (1.2–3.3) | 0.01 | 1.9 | (0.8–4.4) | 0.15 | 0.77 | (0.25–2.3) | 0.64 |

DISCUSSION

Pediatric bone sarcomas require intensive multimodal therapy to achieve sustained disease control, but the scope and impact of treatment-related morbidity on long-term health status has not previously been clinically characterized. This comprehensive assessment of health status, physical and neurocognitive performance of adult survivors of pediatric bone sarcomas demonstrates a significantly elevated cumulative burden and prevalence of chronic health conditions. Cardiovascular and musculoskeletal impairments are particularly prevalent. Furthermore, significant impairments in physical and neurocognitive function not previously described in this population were identified. Through clinical assessments, we provide a more detailed and comprehensive view of the accumulation of health conditions in this population and its impact on their healthcare requirements.

Both survivor cohorts demonstrated an excess risk of cardiomyopathy, with a particularly high prevalence among osteosarcoma survivors (20.5%). Additionally, nearly two-thirds of osteosarcoma survivors had evidence of hypertension, with 30% requiring medications (grade ≥ 2), twice the rate of both Ewing sarcoma survivors and controls. Our findings exceed prevalence rates for hypertension in other studies evaluating survivors of childhood sarcomas29–31 We additionally identified a high prevalence of pre-hypertension (CTCAE grade 1) at an earlier age then previously described. The increased prevalence of hypertension and other cardiac conditions observed in osteosarcoma survivors is likely multi-factorial. A prior study evaluating blood pressures across all childhood cancer survivors at our institution did not identify significant associations between chemotherapy and hypertension;32 furthermore, a recent systematic review of nephrotoxic treatments of childhood cancer failed to identify chemotherapeutic exposures as a risk factor for hypertension.33 Increased rates of chronic kidney disease were seen among osteosarcoma survivors compared to Ewing sarcoma, potentially related to platinum-based drugs utilized in many osteosarcoma protocols. Renal impairment is well established to increase the risk of cardiovascular morbidities and may also contribute to the burden of cardiac conditions in osteosarcoma survivors.34 Importantly, hypertension after anthracycline exposure increases risk of coronary artery disease, valvular disease and heart failure, and is independently associated with increased risk of cardiac-related mortality.31 Earlier recognition and treatment of hypertension among osteosarcoma survivors may preserve cardiac health in this population.35 Recent studies of intensive blood pressure control among subjects with increased cardiovascular risks have shown reductions in subsequent cardiac events and all-cause mortality; investigations of aggressive hypertension management in osteosarcoma survivors should be considered.36 While other modifiable risk factors (e.g. diabetes, dyslipidemia, obesity) were not increased compared to controls (Table 2), the excessive cumulative burden of cardiac conditions underscores the need for counseling regarding physical activity, dietary modifications and tobacco use to mitigate additional risks of early-onset cardiac disease in this high-risk group.

Primary hypogonadism and abnormal sperm concentrations were frequent among Ewing sarcoma survivors consistent with exposure to gonadotoxic alkylating agents and pelvic radiation exposure, particularly among females. Similar rates of infertility may be expected with modern treatment approaches which utilize similar cumulative dosages. Osteosarcoma survivors from this era also frequently received cyclophosphamide equivalent dosing at levels associated with oligospermia and decreased likelihood of pregnancy.37, 38 The impact of ifosfamide exposure from recent contemporary trials may have yet to be fully observed.39 Exposure to cisplatin has also been associated with reduced fertility and hypogonadism in males. As many osteosarcoma survivors in our cohort received both alkylating agents and cisplatin or carboplatin, only a subset of males provided semen samples, thus we could not independently assess the impact of alkylators or platinum-based therapies on primary male fertility.38 Contemporary North American pediatric protocols for osteosarcoma, which incorporate methotrexate, doxorubicin and cisplatin without alkylating agents, may yield lower rates of infertility than those demonstrated in our cohort. Ongoing collaborative studies of survivors provide an opportunity to investigate primary outcomes in survivors, based on semen analysis, and characterize the effect of platinum-based drugs on spermatogenesis and fertility. Recognizing improvements in survival across treatment eras, our findings highlight the importance of offering fertility preservation methods to newly diagnosed patients with sarcomas, and screening for evidence of hypogonadism in survivors to provide appropriate interventions such as hormonal replacement therapy.

As expected in a population with musculoskeletal tumors,21, 40 for whom local control is invasive (amputation or limb-sparing surgery) or confers damage that interferes with growth (radiation), clinical assessments of physical performance revealed significant functional deficits among survivors across all six domains studied. An important finding in this study was the discovery of impaired walking efficiency, which depends on integrated function of the musculoskeletal and cardiorespiratory systems, in all survivors, but particularly among osteosarcoma survivors with amputation. Suboptimal cardiac function and limb abnormalities are likely reasons for this limitation. Inefficient movement is a deterrent to regular participation in physical activity41 and problematic in a population already at risk for cardiovascular conditions.42 Because data indicate that inactivity among childhood cancer survivors confers increased risk for cardiovascular disease and death,43, 44 early interventions to optimize physical function, both during and following completion of therapy, may improve survivors’ ability to engage in more strenuous physical activity. Interventions should be tailored to accommodate the unique combination of chronic conditions and impairments seen in this population. Specialists with knowledge and experience treating patients with cancer are needed to prescribe appropriate dose, intensity, frequency and progression of exercise. Pilot studies of pre-operative strengthening and mobility training for patients with lower extremity sarcomas demonstrated feasibility and improved post-operative functional mobility.45

Survivors of osteosarcoma demonstrated increased prevalence of impaired executive function and memory loss compared to controls; this is consistent with our previous report on neurocognitive impairment among osteosarcoma survivors, with noted deficits in processing speed, memory, and attention.4 The increased sample size of osteosarcoma survivors in the current cohort allows for more precise evaluation of deficits in this population. Ewing sarcoma survivors did not appear to have an increased prevalence of neurocognitive impairment, a positive finding for this group. No associations of therapeutic exposures such as cisplatin or methotrexate with neurocognition were identified to explain these differences. We recently demonstrated associations between physical activity and neurocognitive outcomes in survivors of acute lymphoblastic leukemia;46 exercise intolerance and overall poor physical health could contribute to greater risk of neurocognitive changes in osteosarcoma survivors, who demonstrated impaired aerobic function and mobility in our study. Future studies should evaluate interventions for physical performance and associations with neurocognitive outcomes in survivors. Among both survivor cohorts, a higher level of moderate to severe chronic health conditions increased risk of executive function; increasing evidence suggests that systemic health conditions affect neurocognitive function in survivors. Neurocognitive impairments have been observed in Hodgkin lymphoma, non-Hodgkin lymphoma and osteosarcoma and associated with cardiac, pulmonary and endocrine conditions.47 Our findings provide further evidence that systemic effects of therapy yield lasting impacts on patient neurocognitive outcomes and support the development of strategies to ameliorate therapy-related toxicities to better preserve function in survivorship. Screening for neurocognitive impairments may allow for pharmacologic interventions or enrollment in rehabilitative programs.47

Despite having the longest follow-up and most comprehensive clinical assessment of bone sarcoma survivors, some limitations should be considered when interpreting our results. The inclusion criteria of survival 10 years from diagnosis may have excluded certain earlier onset conditions such as therapy-related acute leukemias and early cardiomyopathy. Participation required returning to SJCRH, potentially excluding those who were unable to travel due to work, family commitments, health-related issues, or death; this could have resulted in an under- or overestimation of our findings. Despite this, no significant differences were identified between survivors who did or did not participate in the overall SJLIFE cohort.48 Some patients had returned to SJCRH for years prior to the SJLIFE study for follow-up of late effects, it is possible that these survivors experienced more preventive care and interventions. Our results therefore may be less generalizable to the broader population of childhood cancer survivors. Changes in surgical practices over treatment eras may also limit generalizability as limb-sparing procedures have become standard treatment for extremity bone sarcomas. However, 20 to 30% of reconstructions will require revision or replacement, secondary to infection or mechanical failure.49, 50 Survivors therefore will likely continue to acquire a high burden of musculoskeletal conditions through prosthetic malfunction, chronic pain/neuropathy, or even conversion to amputation. Advances in surgical techniques and endoprostheses as well as improved delivery of radiation may improve the future physical function of these survivors while minimizing radiation-induced injury. The rarity of some outcomes and small sample sizes prevented more robust analytic investigation of potential associations with various demographic and treatment factors.

In this systematically assessed cohort of young adult survivors of childhood bone sarcomas, we demonstrate not only a high prevalence of chronic health conditions but, importantly, a high magnitude of health conditions and impairments in physical and cognitive function. Clinical ascertainment of these parameters provides a clearer picture of the impact of late sequelae on general health and performance status during adulthood. Our findings are important to guide health care initiatives and interventions aimed at bone sarcoma survivors that can be implemented early in survivorship or even during active treatment. Pre-emptive action to reduce the cumulative burden of late effects may allow for prolonged survival and improved quality of life.

Supplementary Material

GRANT SUPPORT:

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health: Cancer Center Support (CORE) Grant CA21765 (PI: C.W. Roberts) and U01 CA195547 (M-PI: M.M. Hudson and L.L. Robison), and the American Lebanese Syrian Associated Charities (all authors received).

Footnotes

Data are shared according to the St. Jude Lifetime Cohort Study Resource Sharing Plan.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST: the authors declare no potential conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES:

- 1.Hudson MM, Ness KK, Gurney JG, et al. Clinical ascertainment of health outcomes among adults treated for childhood cancer. JAMA. 2013;309: 2371–2381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gaspar N, Hawkins DS, Dirksen U, et al. Ewing Sarcoma: Current Management and Future Approaches Through Collaboration. J Clin Oncol. 2015;33: 3036–3046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Isakoff MS, Bielack SS, Meltzer P, Gorlick R. Osteosarcoma: Current Treatment and a Collaborative Pathway to Success. J Clin Oncol. 2015;33: 3029–3035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Edelmann MN, Daryani VM, Bishop MW, et al. Neurocognitive and Patient-Reported Outcomes in Adult Survivors of Childhood Osteosarcoma. JAMA Oncol. 2016;2: 201–208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nagarajan R, Kamruzzaman A, Ness KK, et al. Twenty years of follow-up of survivors of childhood osteosarcoma: a report from the Childhood Cancer Survivor Study. Cancer. 2011;117: 625–634. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Meadows AT, Friedman DL, Neglia JP, et al. Second neoplasms in survivors of childhood cancer: findings from the Childhood Cancer Survivor Study cohort. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27: 2356–2362. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hoffman MC, Mulrooney DA, Steinberger J, Lee J, Baker KS, Ness KK. Deficits in physical function among young childhood cancer survivors. J Clin Oncol. 2013;31: 2799–2805. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fidler MM, Frobisher C, Guha J, et al. Long-term adverse outcomes in survivors of childhood bone sarcoma: the British Childhood Cancer Survivor Study. Br J Cancer. 2015;112: 1857–1865. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Marina NM, Liu Q, Donaldson SS, et al. Longitudinal follow-up of adult survivors of Ewing sarcoma: A report from the Childhood Cancer Survivor Study. Cancer. 2017;123: 2551–2560. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Smith WA, Li Z, Loftin M, et al. Measured versus self-reported physical function in adult survivors of childhood cancer. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2014;46: 211–218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hudson MM, Ness KK, Nolan VG, et al. Prospective medical assessment of adults surviving childhood cancer: study design, cohort characteristics, and feasibility of the St. Jude Lifetime Cohort study. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2011;56: 825–836. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Landier W, Bhatia S, Eshelman DA, et al. Development of risk-based guidelines for pediatric cancer survivors: the Children’s Oncology Group Long-Term Follow-Up Guidelines from the Children’s Oncology Group Late Effects Committee and Nursing Discipline. J Clin Oncol. 2004;22: 4979–4990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kelly TL, Wilson KE, Heymsfield SB. Dual energy X-Ray absorptiometry body composition reference values from NHANES. PLoS One. 2009;4: e7038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hudson MM, Ehrhardt MJ, Bhakta N, et al. Approach for Classification and Severity Grading of Long-term and Late-Onset Health Events among Childhood Cancer Survivors in the St. Jude Lifetime Cohort. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2017;26: 666–674. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bhakta N, Liu Q, Ness KK, et al. The cumulative burden of surviving childhood cancer: an initial report from the St Jude Lifetime Cohort Study (SJLIFE). Lancet. 2017;390: 2569–2582. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dong H, Robison LL, Leisenring WM, Martin LJ, Armstrong GT, Yasui Y. Estimating the burden of recurrent events in the presence of competing risks: the method of mean cumulative count. Am J Epidemiol. 2015;181: 532–540. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.van Iersel L, Li Z, Srivastava DK, et al. Hypothalamic-Pituitary Disorders in Childhood Cancer Survivors: Prevalence, Risk Factors and Long-Term Health Outcomes. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chemaitilly W, Li Z, Krasin MJ, et al. Premature Ovarian Insufficiency in Childhood Cancer Survivors: A Report From the St. Jude Lifetime Cohort. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2017;102: 2242–2250. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chemaitilly W, Li Z, Krasin MJ, et al. Premature Ovarian Insufficiency in Childhood Cancer Survivors: A Report From the St. Jude Lifetime Cohort. Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism. 2017;102: 2242–2250. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chemaitilly W, Liu Q, van Iersel L, et al. Leydig Cell Function in Male Survivors of Childhood Cancer: A Report From the St Jude Lifetime Cohort Study. J Clin Oncol. 2019;37: 3018–3031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fernandez-Pineda I, Hudson MM, Pappo AS, et al. Long-term functional outcomes and quality of life in adult survivors of childhood extremity sarcomas: a report from the St. Jude Lifetime Cohort Study. J Cancer Surviv. 2017;11: 1–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Piercy KL, Troiano RP, Ballard RM, et al. The Physical Activity Guidelines for Americans. JAMA. 2018;320: 2020–2028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Strauss E, Sherman EMS, Spreen O, Spreen O. A compendium of neuropsychological tests : administration, norms, and commentary. 3rd ed Oxford ; New York: Oxford University Press, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Conners CK. Conners’ Continuous Performance Test II. North Tonawanda, NY: Multi-Health Systems, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wechsler D Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale. San Antonio, TX: Psychological Corporation, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Delis DC KJ, Kaplan E, Ober BA. California Verbal Learning Test, 2nd ed San Antonio, TX: Psychological Corporation, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Geskus RB. Cause-specific cumulative incidence estimation and the fine and gray model under both left truncation and right censoring. Biometrics. 2011;67: 39–49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zou G A modified poisson regression approach to prospective studies with binary data. Am J Epidemiol. 2004;159: 702–706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Aksnes LH, Bauer HC, Dahl AA, et al. Health status at long-term follow-up in patients treated for extremity localized Ewing Sarcoma or osteosarcoma: a Scandinavian sarcoma group study. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2009;53: 84–89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Schiavetti A, Pedetti V, Varrasso G, et al. Long-term renal function and hypertension in adult survivors of childhood sarcoma: Single center experience. Pediatr Hematol Oncol. 2018;35: 167–176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Armstrong GT, Oeffinger KC, Chen Y, et al. Modifiable risk factors and major cardiac events among adult survivors of childhood cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2013;31: 3673–3680. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gibson TM, Li Z, Green DM, et al. Blood Pressure Status in Adult Survivors of Childhood Cancer: A Report from the St. Jude Lifetime Cohort Study. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2017;26: 1705–1713. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kooijmans EC, Bokenkamp A, Tjahjadi NS, et al. Early and late adverse renal effects after potentially nephrotoxic treatment for childhood cancer. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2019;3: CD008944. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kavey RE, Allada V, Daniels SR, et al. Cardiovascular risk reduction in high-risk pediatric patients: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association Expert Panel on Population and Prevention Science; the Councils on Cardiovascular Disease in the Young, Epidemiology and Prevention, Nutrition, Physical Activity and Metabolism, High Blood Pressure Research, Cardiovascular Nursing, and the Kidney in Heart Disease; and the Interdisciplinary Working Group on Quality of Care and Outcomes Research: endorsed by the American Academy of Pediatrics. Circulation. 2006;114: 2710–2738. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.James PA, Oparil S, Carter BL, et al. 2014 evidence-based guideline for the management of high blood pressure in adults: report from the panel members appointed to the Eighth Joint National Committee (JNC 8). JAMA. 2014;311: 507–520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Group SR, Wright JT Jr., Williamson JD, et al. A Randomized Trial of Intensive versus Standard Blood-Pressure Control. N Engl J Med. 2015;373: 2103–2116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Green DM, Liu W, Kutteh WH, et al. Cumulative alkylating agent exposure and semen parameters in adult survivors of childhood cancer: a report from the St Jude Lifetime Cohort Study. Lancet Oncol. 2014;15: 1215–1223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Chow EJ, Stratton KL, Leisenring WM, et al. Pregnancy after chemotherapy in male and female survivors of childhood cancer treated between 1970 and 1999: a report from the Childhood Cancer Survivor Study cohort. Lancet Oncol. 2016;17: 567–576. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Marina NM, Smeland S, Bielack SS, et al. Comparison of MAPIE versus MAP in patients with a poor response to preoperative chemotherapy for newly diagnosed high-grade osteosarcoma (EURAMOS-1): an open-label, international, randomised controlled trial. Lancet Oncol. 2016;17: 1396–1408. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Stokke J, Sung L, Gupta A, Lindberg A, Rosenberg AR. Systematic review and meta-analysis of objective and subjective quality of life among pediatric, adolescent, and young adult bone tumor survivors. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2015;62: 1616–1629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ness KK, Leisenring WM, Huang S, et al. Predictors of inactive lifestyle among adult survivors of childhood cancer: a report from the Childhood Cancer Survivor Study. Cancer. 2009;115: 1984–1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Armstrong GT, Joshi VM, Ness KK, et al. Comprehensive Echocardiographic Detection of Treatment-Related Cardiac Dysfunction in Adult Survivors of Childhood Cancer: Results From the St. Jude Lifetime Cohort Study. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2015;65: 2511–2522. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Jones LW, Liu Q, Armstrong GT, et al. Exercise and risk of major cardiovascular events in adult survivors of childhood hodgkin lymphoma: a report from the childhood cancer survivor study. J Clin Oncol. 2014;32: 3643–3650. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Scott JM, Li N, Liu Q, et al. Association of Exercise With Mortality in Adult Survivors of Childhood Cancer. JAMA Oncol. 2018;4: 1352–1358. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Corr AM, Liu W, Bishop M, et al. Feasibility and functional outcomes of children and adolescents undergoing preoperative chemotherapy prior to a limb-sparing procedure or amputation. Rehabil Oncol. 2017;35: 38–45. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Phillips NS, Howell CR, Lanctot JQ, et al. Physical fitness and neurocognitive outcomes in adult survivors of childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia: A report from the St. Jude Lifetime cohort. Cancer. 2020;126: 640–648. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Krull KR, Hardy KK, Kahalley LS, Schuitema I, Kesler SR. Neurocognitive Outcomes and Interventions in Long-Term Survivors of Childhood Cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2018;36: 2181–2189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ojha RP, Oancea SC, Ness KK, et al. Assessment of potential bias from non-participation in a dynamic clinical cohort of long-term childhood cancer survivors: results from the St. Jude Lifetime Cohort Study. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2013;60: 856–864. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Henderson ER, Groundland JS, Pala E, et al. Failure mode classification for tumor endoprostheses: retrospective review of five institutions and a literature review. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2011;93: 418–429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Albergo JI, Gaston CL, Aponte-Tinao LA, et al. Proximal Tibia Reconstruction After Bone Tumor Resection: Are Survivorship and Outcomes of Endoprosthetic Replacement and Osteoarticular Allograft Similar? Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2017;475: 676–682. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.