Abstract

Purpose: To determine the relationship between pubertal development and postpubertal gonadal function in childhood cancer survivors.

Methods: Childhood cancer survivors (≥10 years of age) who received follow-up care in a pediatric oncology group in an academic medical center during the period from January 1, 1985, to July 1, 2010 were included in this case series. Their pubertal development and gonadal function were evaluated.

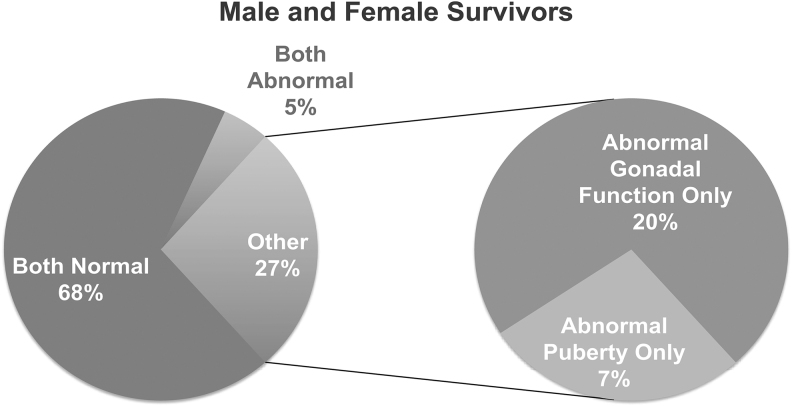

Results: The cohort consists of 39 males (age 10–21 years) and 35 females (age 10–29 years) with a variety of cancer diagnosis and treatments. The average age at diagnosis was ∼7.5 years. The average age at the time of the study was 16 and 16.7 years in males and females, respectively, representing a mean follow-up interval of ∼9 years. Despite the fact that 60% of survivors received cyclophosphamide equivalents and 16.2% received cranial radiation or brain tumor resection, the majority of survivors (68%) presented with both normal puberty and normal gonadal functions at the time of follow-up. In 27% of survivors, puberty development did not predict gonadal function in early adulthood: 20% of survivors had normal puberty, but abnormal gonadal function; 7% of survivors had abnormal puberty, but gonadal function remained normal as young adults.

Conclusions: Most childhood cancer survivors had normal puberty and gonadal function despite a variety of cancer treatment modalities. However, normal puberty did not predict normal gonadal function later in life in many survivors. Therefore, close follow-up with gonadal function in adolescent and early adulthood years is essential.

Keywords: childhood cancer survivor, puberty, gonadal function, premature ovarian insufficiency, chemotherapy, radiation therapy

Introduction

Major therapeutic advances over the past decades have resulted in 5- and 10-year survival rates for childhood cancer now exceeding 80%.1 It was estimated that there were 65,190 cancer survivors aged birth to 14 years and 47,180 survivors aged 15–19 years living in the United States as of January 1, 2016.2 Approximately 70% of pediatric cancer survivors will develop at least one medical complication or disability by 30 years from diagnosis, most of which can be attributed to their previous cancer treatments.3 Endocrine and reproductive disturbances are among the most common late effects of cancer treatment, affecting 40%–60% of childhood cancer survivors.4–6 Individuals exposed to radiotherapy and high doses of alkylating agents are at particularly high risk of developing endocrine complications.7–9 One important aspect of endocrinopathy may involve alterations in pubertal development. The diagnosis and treatment of a childhood malignancy before the onset of puberty has the potential to profoundly affect the timing and the tempo of puberty. Central nervous system (CNS) tumors located in the hypothalamic/pituitary region, surgical resection in this location, and exposure to CNS radiotherapy are all associated with both precocious and delayed puberty.10,11 Chemotherapy and radiation can directly damage the gonads, which can result in absent, arrested, or delayed puberty.10,11 As a result of the inability of oocytes to regenerate after injury, a number of chemotherapeutic agents significantly increase the risks of developing premature ovarian insufficiency.12,13 The parenthood probability in cancer survivors is significantly reduced compared with the general population.14 The likelihood that testicular or ovarian function will be lost is dependent upon both age of receiving the gonadotoxic treatment and type of chemotherapeutic agents. Alkylating agents especially cyclophosphamide and its equivalents are most commonly implicated in premature gonadal failure.15–19 Amenorrhea rates associated with cyclophosphamide equivalents increase with higher cumulative doses.16,20 The Children's Oncology Group (COG) has now recommended that FSH, LH, estradiol, and testosterone should be screened at age 13, and as clinically indicated in patients with delayed puberty, amenorrhea and/or clinical signs and symptoms of estrogen deficiency.21

However, it remains unclear whether children who have normal pubertal development after cancer treatments have normal gonadal function as young adults, as few studies have followed childhood cancer survivors longitudinally through puberty and early adulthood and examined the association between pubertal development and postpubertal gonadal function. The Childhood Cancer Survivor Study has published several studies on gonadal function and fertility following chemotherapy and radiation.22,23 These studies included extremely large numbers of survivors with long-term follow-up and the data were well analyzed. However, due to the self-reporting nature of the database, the detailed pubertal and reproductive history, as well as hormonal measurements of gonadal function, was not reported.24 Therefore, we conducted this retrospective study to examine the detailed cancer and developmental history as well as laboratory measures of gonadal function in a cohort of childhood cancer survivors after long-term follow-up, especially focusing on abnormal pubertal development and gonadal dysfunction. We found that during the follow-up period (on average 9 years after cancer treatments), most childhood cancer survivors had normal puberty and gonadal function despite a variety of cancer treatment modalities. However, normal puberty did not predict normal gonadal function later in life in a significant number of survivors.

Patients and Methods

After obtaining approval from the Internal Review Board at Walter Reed National Military Medical Center (WRNMMC), we conducted a retrospective chart review. Childhood cancer survivors (≥10 years of age) who received care at the WRNMMC during the period from January 1, 1985, to July 1, 2010, were identified through the registry maintained by the WRNMMC childhood cancer survivor clinic and their medical records were reviewed. The exclusion criteria include patients who started cancer treatments after 18 years of age, who underwent gonadectomy, and who had ongoing chemotherapy or radiation therapy at the time of the review. Laboratory measures of gonadal function, including FSH and LH in all survivors, estradiol level in females, and testosterone level in males, were obtained during routine medical care. FSH, LH, and estradiol levels in female survivors were obtained in the early follicular phase between menstrual cycle days 2–5 if menses were present. At the time of data collection, antimullerian hormone (AMH) was not a standard ovarian reserve test that was routinely offered in cancer survivor clinics, and therefore, we do not have the data available in this study. Cancer treatment history, including history of surgery, chemotherapy, and radiation therapy, was carefully recorded in each survivor. We also obtained detailed history and physical examination information, specifically including Tanner stage, puberty development, growth curve, and testicular volume in males. The data were analyzed in an anonymous manner and no patient identifier was linked to the data set. Only pooled data analysis results are presented here.

Precocious puberty was diagnosed by any sign of secondary sexual maturity before 8 years of age in girls and 9 years of age in boys. Delayed puberty was defined by lack of testicular enlargement in boys by age 14 years, and lack of breast development in girls by age 13 years. A diagnosis of hypogonadotropic hypogonadism was made in males with low morning testosterone levels (<200 ng/dL) and low or normal LH and FSH levels, or females with low estradiol and low or normal FSH levels and amenorrhea. In males, small testicular volume (<20 mL) and oligospermia, if semen analysis is collected, were used to diagnose germ cell or seminiferous tubular insufficiency, whereas elevated serum levels of LH with low levels of testosterone were consistent with the diagnosis of Leydig cell failure. In females, primary ovarian insufficiency (POI) was characterized by menstrual irregularity and FSH in the menopausal range (≥40 mIU/mL in our laboratory).

Results

We identified a cohort of 74 childhood cancer survivors, including 39 males (age 10–21 years) and 35 females (age 10–29 years). The average age at diagnosis was ∼7.5 years. The average age at the time of study was 16 and 16.7 years in males and females, respectively, representing a mean follow-up interval of ∼9 years (Table 1). A variety of cancers were diagnosed in this cohort, including leukemia, lymphoma, rhabdomyosarcoma, sarcoma, Wilms tumor, neuroblastoma, and CNS tumors. A high percentage of survivors underwent gonadotoxic treatments, with 60% having received cyclophosphamide equivalents. Two survivors received abdominal radiation, and one male received total body radiation. Twelve survivors received cranial radiation or brain tumor resection (Table 2).

Table 1.

Survivor Cohort Age Characteristics

| Gender | Age at cancer diagnosis | Age at completion of cancer treatment | Age at time of study |

|---|---|---|---|

| Male (n = 39) | 7.4 ± 7.4 | 8.8 ± 4.1 | 16.0 ± 3.3 |

| Female (n = 35) | 7.5 ± 7.6 | 8.5 ± 5.4 | 16.7 ± 5.7 |

Age in years; mean ± SD.

SD, standard deviation.

Table 2.

Cancer Treatment Characteristics

| Cancer treatments | Female (n = 35) | Male (n = 39) |

|---|---|---|

| Cyclophosphamide equivalents | 21 (60.0) | 23 (58.9) |

| Abdominal radiation | 1 (2.8) | 1 (2.6) |

| TB radiation | 0 | 1 (2.6) |

| Head radiation | 5 (14.3) | 5 (12.8) |

| Brain tumor resection | 1 (2.8) | 1 (2.6) |

Data presented as number of survivors (% of the subgroup). The discrepancy between the total number of survivors and the numbers accounted for in this table was due to some of the survivors not receiving any of the listed treatment modalities, while others received multiple treatments.

TB, total body.

All male survivors received cancer diagnosis by 16 years of age and 79% by 12 (Table 3). Among 23 survivors who were treated with cyclophosphamide equivalents, those with abnormal puberty (n = 4) also had brain radiation or surgery. Two of the patients with abnormal puberty had normal gonadal function, whereas another two presented with tubular insufficiency. All patients with testicular failure (n = 4) received cyclophosphamide equivalents and/or brain radiation (Table 4). Of the six male survivors with abnormal gonadal functions, five had normal puberty, and one showed slow linear growth. All male patients with primary hypogonadism received cyclophosphamide equivalents, and those with secondary hypogonadism received cranial radiation or brain tumor resection (Table 5).

Table 3.

Development of Abnormal Puberty or Gonadal Function in Different Age Groups

| Age at diagnosis (years) | Survivors |

Abnormal pubertya |

Gonadal dysfunctiona |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Male (n = 39), % | Female (n = 35), % | Male, % | Female, % | Male, % | Female, % | |

| ≤10 | 71.8 | 71.4 | 7.7 | 12 | 10.3 | 2.9 |

| 11–14 | 20.5 | 17.1 | 2.6 | 0 | 2.6 | 5.7 |

| 15–18 | 7.7 | 11.4 | 0 | 0 | 2.6 | 0 |

Percentage calculated as % of total male or female survivors.

Table 4.

Survivors with Abnormal Pubertal Development

| Gender | Abnormal puberty | Age at diagnosis (years) | Age at time of study (years) | Diagnosis | Treatments | Gonadal function |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Male | Precocious | 1 | 10 | Hypothalamic juvenile pilocytic astrocytoma | Cranial XRT | N/A |

| Male | Delayed | 4 | 18 | Acute myeloid leukemia | Cyclophosphamide+TB XRT | Tubular insufficiency |

| Male | Interrupted | 12 | 21 | CNS germinoma | Cyclophosphamide+cranial spinal XRT | Normal |

| Male | Delayed | 9 | 21 | Parapharyngeal rhabdomyosarcoma | Cyclophosphamide+head/neck/pharyngeal XRT | Tubular insufficiency |

| Female | Precocious | 1 | 10 | Atypical tereatoid rhabdoid CNS posterior fossa tumor | Cranial XRT | N/A |

| Female | Precocious | 7 | 18 | Neurofibromatosis type1 left temporal astrocytoma | Brain tumor resection | Normal |

| Female | Delayed | 5 | 17 | Atypical rhabdoid/teratoid brain tumor | Brain tumor resection+cranial/spinal XRT | Normal |

Among chemotherapy agents, only cyclophosphamide equivalents are listed.

CNS, central nervous system; N/A, not applicable; XRT, radiation.

Table 5.

Survivors with Abnormal Gonadal Function

| Gender | Abnormal gonadal function | Age at diagnosis (years) | Age at time of study (years) | Diagnosis | Treatments | Puberty |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Male | Tubular insufficiency | 9 | 21 | Parapharyngeal rhabdomyosarcoma | Cyclophosphamide+head/neck/pharyngeal XRT | Slow linear growth |

| Male | Tubular insufficiency | 11 | 17 | ALL | Ifosfamide | Normal |

| Male | Tubular insufficiency | 4 | 18 | AML | Cyclophosphamide+TB XRT | Normal |

| Male | Primary hypogonadism | 15 | 20 | Mediastinal sarcoma | Cyclophosphamide+mediastinum XRT | Normal |

| Male | Secondary hypogonadism | 2 | 15 | T cell non-Hodgkin lymphoma | Cranial XRT | Normal |

| Male | Secondary hypogonadism | 2.5 | 21 | Left temporal mixed oligodendroglioma and possible disembryoplastic-neuroepithelial tumor | Procarbazine+brain tumor resection | Normal |

| Female | POI at 15 years old | 14 | 24 | Ewing sarcoma | Cyclophosphamide, ifosfamide | Normal |

| Female | POI at 16 years old | 14 | 17 | Wilms tumor | Cyclophosphamide+abdominal XRT | Normal |

| Female | POI at 11 years old | 3 | 11 | Parameningeal nasopharyngeal rhabdomyosarcoma | Cyclophosphamide+nasopharyngeal XRT | Normal |

Among chemotherapy agents, only cyclophosphamide equivalents are listed.

ALL, acute lymphocytic leukemia; AML, acute myeloid leukemia; POI, primary ovarian insufficiency.

Among the 35 female childhood cancer survivors, 25 (71%) were diagnosed by 10 years of age (Table 3), 3 of whom developed abnormal puberty, and 1 had abnormal gonadal function. Six survivors were diagnosed between 11 and 14 years of age, two of whom developed abnormal gonadal function (Table 4). None of the four patients diagnosed at 15–18 years of age developed abnormal gonadal function. Similar to male survivors, all females with abnormal puberty (n = 3) had cranial radiation or brain tumor resection (Table 4). Two of these three patients had normal gonadal function and one was premenarchal. Although 60% were treated with cyclophosphamide equivalents, all had normal puberty and 90% had normal sex hormone profiles. Female patients with abnormal gonadal function (n = 3) did not experience abnormal pubertal development. All three survivors with premature ovarian failure but normal puberty had been treated with cyclophosphamide equivalents (Table 5).

Combining all the male and female survivors, 68% of survivors presented with both normal puberty and normal gonadal functions at the time of follow-up (Fig. 1). In 5% of survivors, both were abnormal. In the remaining 27% of survivors, puberty development did not predict gonadal function in early adulthood: 20% of survivors had normal puberty, but abnormal gonadal function; 7% of survivors had abnormal puberty, but gonadal function remained normal as young adults (Fig. 1).

FIG. 1.

Summary of puberty and gonadal function in all survivors.

Discussion

By carefully evaluating the medical records and sex hormone profiles in this cohort of childhood cancer survivors on average 9 years following the completion of their cancer treatments, we found that most childhood cancer survivors had normal puberty and gonadal function despite a variety of cancer treatment modalities. Cranial radiation or brain surgery especially in combination with cyclophosphamide equivalents significantly increased the risk for abnormal puberty and secondary gonadal failure. Normal puberty did not predict normal gonadal function later in life in many survivors, and therefore, close follow-up with gonadal function in adolescent and early adulthood years is essential.

A major strength of this study is the detailed medical history, physical examination, and endocrine laboratory results that provide additional details not available from larger studies using mainly self-reported data. The bias caused by self-reporting is limited. The other strengths of our study include the following: (1) most survivors were diagnosed before the onset of puberty, and followed into late teens or early 20s, with a record of detailed pubertal development over many clinic visits, thus allowing a full evaluation of the pubertal development. (2) Mean follow-up period was 9 years after the cancer diagnosis, which is adequate for the assessment of changes in gonadal function in adolescents and young adults. However, we acknowledge that the gonadal function continues to change during later reproductive years in these survivors and abnormal gonadal function such as POI continues to emerge with age. (3) The cohort of survivors includes both genders, and a wide variety of cancer diagnosis and treatment protocols, representing a typical patient population in a pediatric oncology practice. Our findings are thus applicable to daily practice and will be helpful in patient counseling.

Our study has several limitations: It is a retrospective study that only represents one time point for laboratory data collection, and thus lacks the strengths of a prospective or longitudinal study. At the time this study was conducted, the AMH level was not a standard measure for ovarian reserve testing; therefore, we only report the other four hormone levels in our study.

Similar to previous studies,25 our study demonstrated that cranial radiotherapy is a significant risk factor for perturbation of puberty development and secondary hypogonadism. Cyclophosphamide equivalents alone, or in combination with cranial radiotherapy, are a major risk factor for gonadal dysfunction both in male and female survivors.26 However, to our knowledge, no prior study explicitly examined the concurrence of puberty disturbance and gonadal dysfunction at a later age. Our study demonstrated that in a significant percentage of survivors, there is a dissociation between puberty development abnormality and gonadal dysfunction. With longer duration of follow-up, it is possible that this percentage of disassociation may be even higher. Just like regular menses do not reflect normal fertility, a normal puberty does not predict normal ovarian reserve or testicular function in postpubertal years. Our findings may help physicians who offer routine follow-up of childhood cancer survivors to provide better counseling. Close surveillance of gonadal function and endocrinopathy in all childhood cancer survivors following standard long-term follow-up guidelines is warranted.

Ethical Approval

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki Declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Informed Consent

As an anonymous retrospective study, no patient identifiers were retained, and no informed consent was required. This study was approved by the Internal Review Board at WRNMMC and the need for informed consent was waived as part of the study approval.

Disclaimer

The views expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not reflect the official policy of the Department of Army, Department of Defense, or U.S. Government.

Authors' Contributions

B.Y. analyzed the data and wrote the article. R.F. and M.V. edited the article. M.M. collected patient data and edited the article.

Author Disclosure Statement

All authors declare no conflict of interest.

Funding Information

This study was funded in part by NIH grants K08 CA222835, P30 CA015704, K12HD00849 (Reproductive Scientist Development Program) (To B.Y.).

References

- 1. Siegel RL, Miller KD, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2017. CA Cancer J Clin 2017;67:7–30 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Miller KD, Siegel RL, Lin CC, et al. Cancer treatment and survivorship statistics, 2016. CA Cancer J Clin 2016;66:271–89 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Oeffinger KC, Mertens AC, Sklar CA, et al. Chronic health conditions in adult survivors of childhood cancer. N Engl J Med 2006;355:1572–82 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Chemaitilly W, Cohen LE, Mostoufi-Moab S, et al. Endocrine late effects in childhood cancer survivors. J Clin Oncol 2018;36:2153–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Sklar CA, Antal Z, Chemaitilly W, et al. Hypothalamic-pituitary and growth disorders in survivors of childhood cancer: an Endocrine Society Clinical Practice Guideline. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2018;103:2761–84 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Brignardello E, Felicetti F, Castiglione A, et al. Endocrine health conditions in adult survivors of childhood cancer: the need for specialized adult-focused follow-up clinics. Eur J Endocrinol 2013;168:465–72 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Hudson MM, Mulrooney DA, Bowers DC, et al. High-risk populations identified in Childhood Cancer Survivor Study investigations: implications for risk-based surveillance. J Clin Oncol 2009;27:2405–14 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Chemaitilly W, Sklar CA. Endocrine complications in long-term survivors of childhood cancers. Endocr Relat Cancer 2010;17:R141–59 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Nandagopal R, Laverdiere C, Mulrooney D, et al. Endocrine late effects of childhood cancer therapy: a report from the Children's Oncology Group. Horm Res 2008;69:65–74 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Armstrong GT, Chow EJ, Sklar CA. Alterations in pubertal timing following therapy for childhood malignancies. Endocr Dev 2009;15:25–39 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Armstrong GT, Whitton JA, Gajjar A, et al. Abnormal timing of menarche in survivors of central nervous system tumors: a report from the Childhood Cancer Survivor Study. Cancer 2009;115:2562–70 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Bedoschi G, Navarro PA, Oktay K. Chemotherapy-induced damage to ovary: mechanisms and clinical impact. Future Oncol 2016;12:2333–44 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Oktay K, Sonmezer M. Chemotherapy and amenorrhea: risks and treatment options. Curr Opin Obstet Gynecol 2008;20:408–15 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Magelssen H, Melve KK, Skjaerven R, Fossa SD. Parenthood probability and pregnancy outcome in patients with a cancer diagnosis during adolescence and young adulthood. Hum Reprod 2008;23:178–86 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Teinturier C, Hartmann O, Valteau-Couanet D, et al. Ovarian function after autologous bone marrow transplantation in childhood: high-dose busulfan is a major cause of ovarian failure. Bone Marrow Transplant 1998;22:989–94 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Koyama H, Wada T, Nishizawa Y, et al. Cyclophosphamide-induced ovarian failure and its therapeutic significance in patients with breast cancer. Cancer 1977;39:1403–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Schilsky RL, Sherins RJ, Hubbard SM, et al. Long-term follow up of ovarian function in women treated with MOPP chemotherapy for Hodgkin's disease. Am J Med 1981;71:552–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Stillman RJ, Schinfeld JS, Schiff I, et al. Ovarian failure in long-term survivors of childhood malignancy. Am J Obstet Gynecol 1981;139:62–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Green DM, Nolan VG, Goodman PJ, et al. The cyclophosphamide equivalent dose as an approach for quantifying alkylating agent exposure: a report from the Childhood Cancer Survivor Study. Pediatr Blood Cancer 2014;61:53–67 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Ioannidis JP, Katsifis GE, Tzioufas AG, Moutsopoulos HM. Predictors of sustained amenorrhea from pulsed intravenous cyclophosphamide in premenopausal women with systemic lupus erythematosus. J Rheumatol 2002;29:2129–35 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Children's Oncology Group. Long-term follow-up guidelines for survivors of childhood, adolescent and young adult cancers, version 5.0. 2018. Accessed March8, 2020 from: http://www.survivorshipguidelines.org/

- 22. Green DM, Kawashima T, Stovall M, et al. Fertility of female survivors of childhood cancer: a report from the childhood cancer survivor study. J Clin Oncol 2009;27:2677–85 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Green DM, Kawashima T, Stovall M, et al. Fertility of male survivors of childhood cancer: a report from the Childhood Cancer Survivor Study. J Clin Oncol 2010;28:332–9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Armstrong AY, Calis KA, Nelson LM. Do survivors of childhood cancer have an increased incidence of primary ovarian insufficiency? Nat Clin Pract Endocrinol Metab 2007;3:326–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Dixon SB, Bjornard KL, Alberts NM, et al. Factors influencing risk-based care of the childhood cancer survivor in the 21st century. CA Cancer J Clin 2018;68:133–52 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Oeffinger KC, Hudson MM. Long-term complications following childhood and adolescent cancer: foundations for providing risk-based health care for survivors. CA Cancer J Clin 2004;54:208–36 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]