Abstract

Purpose

Acrolein, a highly reactive unsaturated aldehyde, is known to facilitate glial cell migration, one of the pathological hallmarks in diabetic retinopathy. However, cellular mechanisms of acrolein generation in retinal glial cells remains elusive. In the present study, we investigated the role and regulation of spermine oxidase (SMOX), one of the enzymes related to acrolein generation, in retinal glial cells under hypoxic condition.

Methods

Immunofluorescence staining for SMOX was performed using sections of fibrovascular tissues obtained from patients with proliferative diabetic retinopathy. Expression levels of polyamine oxidation enzymes including SMOX were analyzed in rat retinal Müller cell line 5 (TR-MUL5) cells under either normoxic or hypoxic conditions. The transcriptional activity of Smox in TR-MUL5 cells was evaluated using the luciferase assay. Levels of acrolein-conjugated protein, Nε-(3-formyl-3,4-dehydropiperidino) lysine adduct (FDP-Lys), and hydrogen peroxide were measured.

Results

SMOX was localized in glial cells in fibrovascular tissues. Hypoxia induced SMOX production in TR-MUL5 cells, which was suppressed by silencing of hypoxia-inducible factor-1α (Hif1a), but not Hif2a. Transcriptional activity of Smox was regulated through HIF-1 binding to hypoxia response elements 2, 3, and 4 sites in the promoter region of Smox. Generation of FDP-Lys and hydrogen peroxide increased in TR-MUL5 cells under hypoxic condition, which was abrogated by SMOX inhibitor MDL72527.

Conclusions

The current data demonstrated that hypoxia regulates production of SMOX, which plays a role in the generation of oxidative stress inducers, through HIF-1α signaling in Müller glial cells under hypoxic condition.

Keywords: spermine oxidase, hypoxia, Müller glial cells, acrolein

Diabetic retinopathy, a microvascular complication in patients with diabetes, is the leading cause of blindness in developed countries.1 Accumulating evidence from the recent basic and clinical researches suggests that vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) induced by hypoxia plays a crucial role in retinal neovascularization, which eventually leads to fibrovascular proliferation in late-stage diabetic retinopathy.2–4 However, molecular mechanisms underlying fibrovascular proliferation in diabetic retinopathy have not been fully elucidated.

Polyamines are small polycationic molecules with two or more primary amino groups. They function in various biological processes, including cell proliferation and differentiation.5 Mammals have three naturally occurring polyamines: putrescine, spermidine, and spermine.6 Of these, spermine possesses the highest biological activity,7 and conversion of spermine to spermidine occurs through one of two distinct pathways. Spermine is degraded through the back-conversion via the spermine N1-acetyltransferase (SAT1)/peroxisomal N(1)-acetyl-spermine/spermidine oxidase (PAOX) cascade, which generates 3-acetamidopropanal.8 Alternatively, spermine is directly oxidized by spermine oxidase (SMOX) that produces 3-aminopropanal. Whereas 3-acetamidopropanal hardly forms acrolein as its byproduct,9 3-aminopropanal is nonenzymatically converted to acrolein.10

Acrolein is a highly reactive unsaturated aldehyde that preferentially reacts with cysteine, lysine, and histidine residues in peptide chains to preserve aldehyde functionality.11,12 Our previous study demonstrated that the acrolein-conjugated protein Nε-(3-formyl-3,4-dehydropiperidino) lysine adduct (FDP-Lys) accumulates in glial cells of fibrovascular tissues of patients with proliferative diabetic retinopathy (PDR).13 Furthermore, subsequent analyses revealed that the production of acrolein is catalyzed by semicarbazide-sensitive amine oxidase (SSAO), a copper-containing enzyme that deaminates aromatic and aliphatic amines, reduces glutathione production, and consequently increases the generation of reactive oxygen species in retinal microvascular endothelial cells.14 This causes oxidative stress and disrupts cellular homeostasis in patients with diabetes. We recently elucidated that acrolein increases oxidative stress by reducing the antioxidant glutathione in cultured Müller glial cells and accelerates its cellular motility by inducing chemokine (CXC motif) ligand 1 in an autocrine fashion.15 In eyes with PDR, postmortem immunohistochemical studies elucidated that Müller glial cells, a major cellular source of VEGF, migrate into the retina and toward the vitreoretinal surface.16,17 Thus evidence indicates that acrolein is a causative factor for glial cell migration in diabetic retinopathy, and cellular machinery of acrolein generation in retinal glial cells, which lack SSAO, is yet to be understood.

SMOX is a flavin adenine dinucleotide-containing enzyme that catalyzes the oxidative degradation of spermine, a polyamine, to produce spermidine, hydrogen peroxides, and 3-aminopropanal that is, as aforementioned, nonenzymatically converted to acrolein. Müller glial cells are the cellular components of the mammalian retina that contain endogenous spermine.18 Moreover, a study showed that the level of spermine in the vitreous was approximately 15 times higher in patients with PDR than in those without diabetic retinopathy.19 These findings indicate that spermine and its related products are involved in the pathogenesis of diabetic retinopathy. However, spermine metabolism in retinal glial cells, which is likely to be important for further understanding of the pathogenesis of diabetic retinopathy, has not fully been investigated.

The aim of this study was to investigate the effect of hypoxia on SMOX production and its regulatory mechanism in retinal glial cells under hypoxic condition.

Materials and Methods

Cell Culture

Conditionally immortalized rat retinal Müller cell line 5 (TR-MUL5) from transgenic rats harboring the temperature-sensitive simian virus 40 large T-antigen gene was provided by Fact Inc. (Sendai, Japan).20 TR-MUL5 cells were cultured in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (DMEM; FUJIFILM Wako Pure Chemical Corporation, Osaka, Japan) containing 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) and incubated at 33°C. The following experiments were performed at a 5% CO2 with either 20% O2 for normoxia or 1% O2 balanced with N2 for hypoxia at 37°C. All experiments were performed with cells in a subconfluent state and at passages 25 to 40.

Immunofluorescence Microscopy

Fibrovascular tissues were collected from patients with PDR, including two men and one woman, with a mean age of 52.7 ± 4.0 years, and embedded in paraffin after fixation in 4% paraformaldehyde (PFA) and stored at 4°C. This study was conducted in accordance with the tenets of the Declaration of Helsinki. The study protocol was approved by the institutional review committee of the Hokkaido University Hospital (#014-0293). Sections were deparaffinized in xylene, dehydrated through a graded alcohol series, and subsequently rehydrated in deionized water. After microwave-based antigen retrieval with 10 mM citrate buffer (pH 6.0) for 15 minutes, sections were blocked in 10% normal goat serum (Thermo Fisher Scientific) for 1 hour. At 4°C, sections were probed overnight with the following primary antibodies: rabbit anti-SMOX (1:100; Proteintech, Chicago, IL, USA), rabbit anti-SAT1 (1:100; Thermo Fisher Scientific), rabbit anti-PAOX (1:100; Proteintech), and mouse anti-glial fibrillary acid protein (GFAP) (1:100; Leica Microsystems, Exton, PA, USA). The secondary antibodies Alexa Fluor 488 and 546 (1:200; Thermo Fisher Scientific) were used for fluorescence detection. Normal rabbit IgG (1:100; R&D Systems, Inc., Minneapolis, MN, USA) and normal mouse IgG (1:100; Dako, Santa Clara, CA, USA) were used as a negative control. Nuclei were counterstained with DAPI, and sections were visualized under a fluorescence microscope (Keyence, Tokyo, Japan).

For immunofluorescence staining of vimentin in TR-MUL5, the cells were cultured in a 6-well plate with sterile glasses for 24 hours under either normoxic or hypoxic conditions, fixed with 4% PFA for 10 minutes, and permeabilized with 0.2% Triton X-100 for 15 minutes. Subsequently, cells were blocked with 5% normal goat serum and incubated overnight at 4°C with mouse anti-vimentin (1:50; Thermo Fisher Scientific) antibody. Normal mouse IgG (1:50; Dako) in place of the primary antibody was used as a negative control. The secondary antibodies for fluorescent detection were Alexa Fluor 546 (1:200; Thermo Fisher Scientific). Nuclei were counterstained with DAPI, and stained sections were visualized using fluorescence microscope (Keyence).

Real-Time Quantitative-Polymerase Chain Reaction (qPCR)

Following the manufacturers’ instructions, total RNA was isolated using TRI Reagent (Molecular Research Center, Inc., Cincinnati, OH, USA), and reverse transcription was then performed to cDNA with GoScript reverse transcriptase (Promega, Madison, WI, USA). The primer sequences used for real-time qPCR were 5′-CGGGGAAAATGGAAACGTCAG-3′ (forward) and 5′-ACTTTGCATACCGTCCGTACT-3′ (reverse) for Smox, 5′-CCTGGTTGCAGAAGTGCCTAA-3′ (forward) and 5′-GTACATGGCAAAACCAACAATGC-3′ (reverse) for Sat1, 5′-TGGGCCCTCCCATTAGACAG-3′ (forward) and 5′-GTCCTGCTGAGGGTTCAAG-3′ (reverse) for Paox, 5′-AGCAGATGTGAATGCAGACCAAAGA-3′ (forward) and 5′-TGGCTCACCGCCTTGGCTT-3′ (reverse) for Vegfa, and 5′-GGGAAATCGTGCGTGACATT-3′ (forward) and 5′-GCGGCAGTGGCCATCTC-3′ (reverse) for Actb. Real‐time qPCR was performed using the GoTaq qPCR Master Mix (Promega) and StepOne Plus Systems (Thermo Fisher Scientific). Gene expression levels were calculated using the 2-∆∆CT method, and all experimental samples were normalized using Actb as the internal control.

Enzyme-Linked Immunosorbent Assay (ELISA)

TR-MUL5 cells were cultured under normoxic or hypoxic condition for 24 hours. Levels of SMOX protein in the cell lysate were analyzed using ELISA kits for rat SMOX (MyBioSource, San Diego, CA, USA) following the manufacturer's protocol. Absorbance was read at 450 nm on a microplate reader (Tecan Sunrise; Tecan, Inc., Männedorf, Switzerland). SMOX concentration was normalized by total protein concentration of cell lysates measured by bicinchoninic acid protein assay kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific).

Cell Viability Assay

TR-MUL5 cells were seeded into a 96-well plate and incubated for 24 hours at 33°C in the atmosphere of 95% air and 5% CO2. Subsequently, the cells were cultured under normoxic or hypoxic condition for 6 or 24 hours, and cell viability was assessed using CellTiter-Glo 2.0 (Promega), according to the manufacturer's instruction. Luminescence was measured by an Infinite 200 PRO microplate reader (Tecan Sunrise; Tecan, Inc.).

RNA Interference

TR-MUL5 cells were transfected with a 5-nM final concentration of various Dicer-substrate siRNA (DsiRNA) for suppressing the gene expression of hypoxia-inducible factor-1α (Hif1a) or HIF-2α (Hif2a) (Hif1a siRNA-1, rn.Ri.Hif1a.13.1; Hif1a siRNA-2, rn.Ri.Hif1a.13.2; Hif2a siRNA-1, rn.Ri.Hif2a.13.1; Hif2a siRNA-2, rn.Ri.Hif2a.13.2) (IDT, Coralville, Iowa, USA), and negative control siRNA (Ctrl-siRNA, Mission SIC-001; Sigma-Aldrich Corp., St. Louis, MO, USA). Transfections were performed using the Lipofectamine RNAiMAX reagent (Thermo Fisher Scientific). The composite transfection mixture was replaced with 10% FBS/DMEM 24 hours after the transfection. Subsequently, real-time PCR and ELISA for SMOX were performed after 6 and 24 hours of hypoxic stimulation, respectively.

Transient Transfection and Luciferase Assay

TR-MUL5 cells were seeded in a 96-well plate at 1.5 × 104 cells/well containing 65 µL of 10% FBS/DMEM. After incubation for 24 hours, cells were cotransfected with the X-tremeGENE HP DNA transfection reagent (Sigma-Aldrich) containing the pGL4.10 luciferase vector (Firefly-expressing plasmid; Promega), with the Smox promoter (–1067 to +122 bp from transcriptional start site of Smox), and pRL-CMV vector (Renilla-expressing plasmid; Promega). Cells were incubated under hypoxic or normoxic conditions for 24 hours after waiting 24 hours after transfection. Firefly and Renilla luciferase activities were determined using the Dual-Glo luciferase assay system (Promega), and the luciferase activity (a Firefly: Renilla luciferase ratio) was measured according to the manufacturer's instructions. The promoter sequence analysis revealed six putative hypoxia response elements (HREs), 5′-A/GCGTG-3’, over the Smox promoter region. Subsequently, the Smox promoter reporter with each of the six mutant sites was modified into a pGL4.10 luciferase vector using PrimeSTAR Mutagenesis Basal Kit (Takara Bio, Shiga, Japan). The HRE wild-type or mutated constructs, together with pRL-CMV, were transiently cotransfected into TR-MUL5 cells, followed by treatment with hypoxia, and the luciferase activity was measured.

Measurement of Hydrogen Peroxide and FDP-Lys Production

TR-MUL5 cells were cultured with or without 50 µM SMOX inhibitor (MDL72527; Sigma-Aldrich) for 24 hours with or without hypoxia stimulation. Subsequently, cells were incubated in phosphate buffered saline at 37°C for 3 hours, and the concentration of hydrogen peroxide in the supernatant was measured using the Hydrogen Peroxide Detection Kit (Cell Technology, Inc., Fremont, CA, USA), according to the manufacturer's protocol.

FDP-Lys concentration in the supernatant was evaluated using the ELISA kit (MK-150; Takara Bio) and normalized by protein concentration measured using the Quick Start Bradford 1× Dye Reagent (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA, USA).

Statistical Analyses

Data are expressed as mean ± standard error of the mean for three to six individual experiments. Differences between two groups were compared using the Student's t-test. For comparisons of multiple groups, the 1-way ANOVA and Tukey's honestly significant difference multiple comparisons test were used. A P value <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

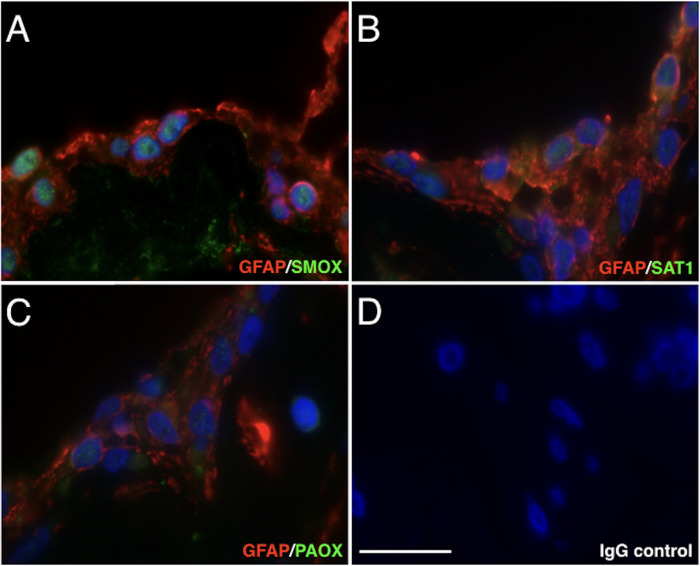

Localization of SMOX, SAT1, and PAOX in Fibrovascular Tissues

To investigate the tissue localization of polyamine catabolic enzymes in fibrovascular tissues of patients with PDR, we performed immunofluorescent staining for polyamine oxidase enzymes, that is, SMOX, SAT1, and PAOX. Immunofluorescence staining showed that SMOX signals were intensely localized in the nucleus of GFAP-positive cells of the fibrovascular tissues (Fig. 1A). However, SAT1 and PAOX signals were weakly detected in glial cells (Figs. 1B, 1C). The staining data indicated that SMOX predominantly plays a role in spermine oxidation in retinal glial cells of fibrovascular tissues.

Figure 1.

Immunofluorescence staining of SMOX, SAT1, and PAOX in fibrovascular tissues of patients with PDR. (A) Green, SMOX (Alexa Fluor 488); red, GFAP (Alexa Fluor 546). (B) Green, SAT1; red, GFAP. (C) Green, PAOX; red, GFAP. (D) Negative control (rabbit and mouse normal IgG) in sequential sections. Scale bar = 20 µm.

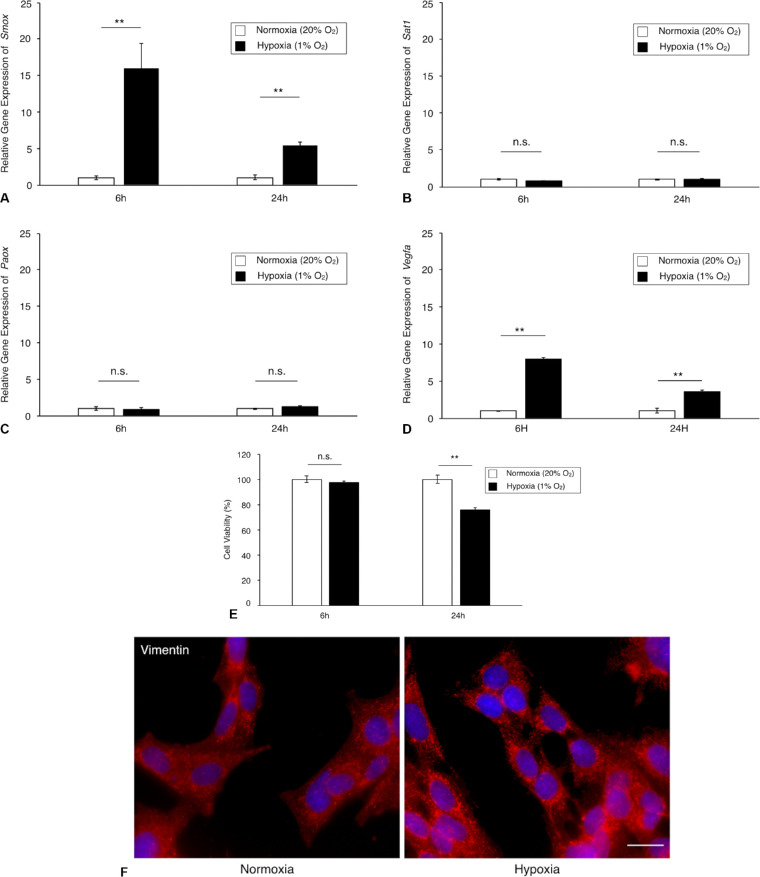

Hypoxic Upregulation of SMOX Expression in TR-MUL5 Cells

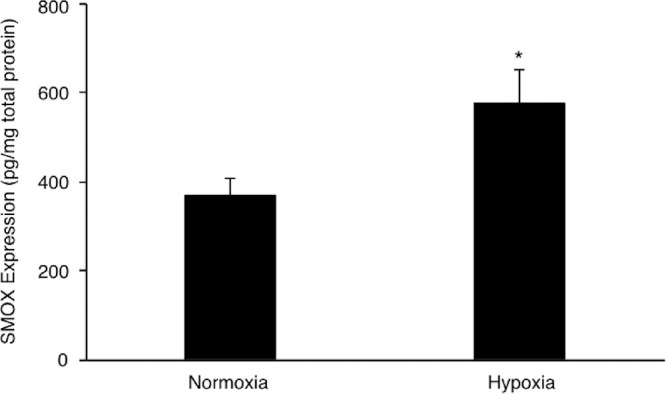

To determine whether polyamine catabolic enzymes are regulated by hypoxic stimulation in TR-MUL5 cells, we examined the mRNA expression levels of Smox, Sat1, and Paox. Under hypoxic condition, the mRNA expression of Smox was significantly upregulated in TR-MUL5 cells at 6 hours and followed with a slight upregulation at 24 hours (Fig. 2A). In contrast, no significant upregulations were observed in mRNA expressions of Sat1 and Paox in TR-MUL5 cells (Figs. 2B, 2C). The mRNA expression level of Vegfa, which was used as a positive control, significantly increased under hypoxic condition (Fig. 2D). Hypoxic condition reduced the cell viability of TR-MUL5 when cultured for 24 hours, but not at 6 hours (Fig. 2E). In addition, immunofluorescent signal of vimentin was found more intensely in TR-MUL5 cells cultured under hypoxic condition than those under normoxic condition (Fig. 2F), indicating the presence of cellular stress at 24 hours after hypoxic stimulation, which reduced Smox mRNA upregulation with time. Consistent with the mRNA data, protein concentration of SMOX under hypoxic condition significantly increased to 1.5 times (P < 0.05) of that under normoxic conditions (Fig. 3). The current data demonstrated that hypoxia upregulates SMOX in retinal glial cells.

Figure 2.

Gene expression levels of polyamine catabolic enzymes in TR-MUL5 cells under hypoxic condition. (A–C) Real-time qPCR analysis for Smox, Sat1, and Paox in TR-MUL5 cells. (D) Real-time qPCR analysis for Vegfa as a positive control. (E) Cell viability assay. (F) Immunofluorescence staining for vimentin. n = 3 in each group. **P < 0.01, n.s., not significant.

Figure 3.

SMOX protein levels in TR-MUL5 cells under hypoxic condition (1% O2) for 24 hours. n = 3 in each group. *P < 0.05.

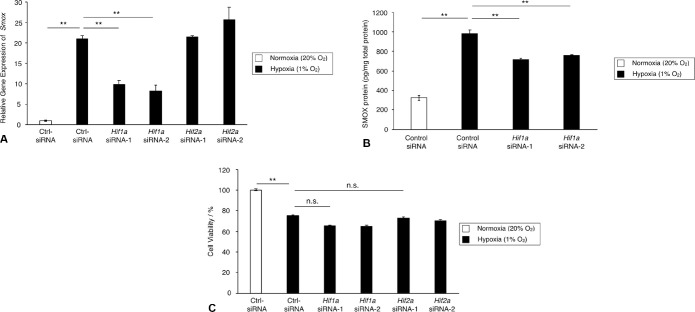

HIF-1α Modulation of the SMOX Expression Level in TR-MUL5 Cells under Hypoxic Condition

HIF, a transcriptional factor, is responsible for cellular responses to hypoxia and regulates various genes that are required for adaptation to hypoxia. To determine whether HIF mediates Smox expression under hypoxic condition, we examined the expression level of Smox mRNA with silencing of either Hif1a or Hif2a. As shown in Figure 4A, expression of Smox was significantly reduced by Hif1a siRNAs, but not by Hif2a siRNAs (Hif2a siRNA-1, P = 0.49; Hif2a siRNA-2, P = 0.06). In accordance with the gene expression data, the protein level of SMOX increased under hypoxic condition and was reduced by Hif1a knockdown (Fig. 4B). Cell viability was unchanged by silencing of either Hif1a or Hif2a (Fig. 4C). These results indicated that HIF-1α, but not HIF-2α, is a primary mediator that regulates SMOX production in TR-MUL5 cells under hypoxic condition.

Figure 4.

Expression and production of SMOX in TR-MUL5 cells with silencing of Hif1a or Hif2a under hypoxic condition (1% O2). TR-MUL5 cells were transfected with control siRNA (Ctrl-siRNA), siRNAs for Hif-1α (Hif1a siRNA-1 and -2), or siRNAs for Hif2a (Hif2a siRNA-1 and -2) and cultivated with or without hypoxic stimulation. (A) Real-time qPCR analysis for Smox mRNA expression 6 hours after hypoxic stimulation. (B) SMOX protein levels in TR-MUL5 cells measured by ELISA 24 hours after hypoxia stimulation. (C) Cell viability assay. n = 3 in each group. **P < 0.01, n.s., not significant.

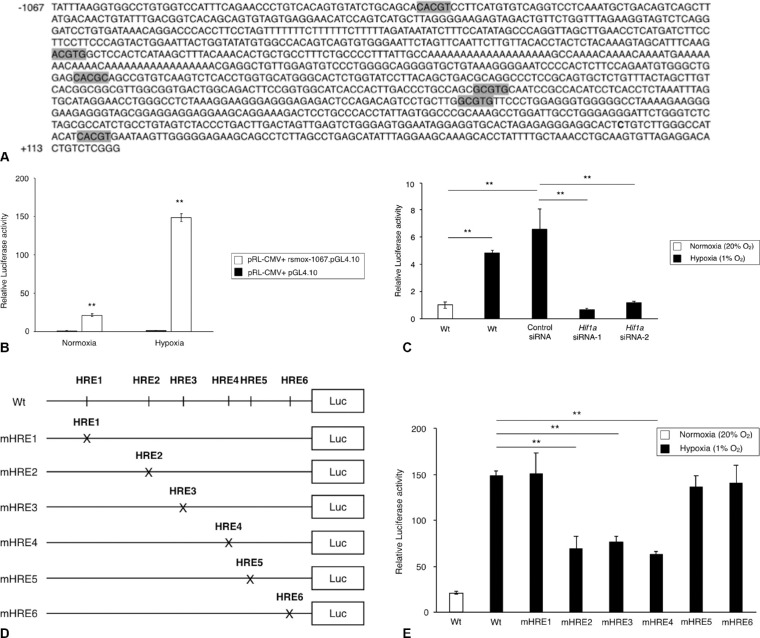

Functional HRE Sites in the SMOX Promoter Region under Hypoxic Condition

Next we examined whether the hypoxic induction of Smox is regulated at the transcriptional level. An analysis of the genomic sequences of rat Smox (NCBI: NC_005102.4) revealed six HRE sites within the promoter region (Fig. 5A). Based on the locations of HRE sites, sequences from –1067 to +122 of the Smox encoding region were cloned into the pGL4.10 luciferase reporter plasmid (rsmox-1067.pGL4.10). To evaluate the functional activity of the Smox promoter, transfection experiments were performed using Smox promoter–reporter vector constructs in TR-MUL5 cells under normoxic or hypoxic condition. As shown in Figure 5B, transcriptional activity of constructs containing rsmox-1067.pGL4.10 were higher under hypoxic condition compared with cells cotransfected with the empty pGL4.10 vector. To further test whether hypoxia regulates Smox transcriptional activity via HIF-1α, we evaluated luciferase activity after cotransfecting the Smox promoter–reporter vector with Hif1a siRNA. As a result, the transcriptional activation of Smox was significantly suppressed by silencing of Hif1a (Fig. 5C), indicating that Hif1a is involved in the hypoxic regulation of Smox transcriptional activity. To investigate the respective activity of the six HRE sites, we generated mutant reporter constructs using site-directed mutagenesis (Fig. 5D). As shown in Figure 5E, the HRE mutant sites (mHRE) 2, 3, and 4 exhibited significant decrease in luciferase activity compared with the nonmutated control, suggesting that these three HRE sites in the Smox promoter contribute to the transcriptional activation of Smox. The current results suggest that hypoxia regulates Smox transcriptional activity via HIF-1α binding to HRE2, HRE3, and HRE4 sites in the Smox promoter.

Figure 5.

Identification of HRE sites in the Smox promoter. (A) Six potential HRE sites located in the rat Smox promoter in the sequence analysis. (B) Luciferase assay for the transcriptional activity of the Smox promoter in TR-MUL5 cells under either normoxic or hypoxic conditions for 24 hours (20% O2 or 1% O2). (C) Effects of Hif1a silencing on Smox expression in TR-MUL5 cells under hypoxic condition (1% O2) for 24 hours. (D) Mutant luciferase constructs designed for each of the six HRE sites via site-direct mutagenesis using the –1067 Luc reporter plasmid as a backbone. (E) Effects of Smox promoter mutations on the Smox transcriptional activity in TR-MUL5 cells stimulated with hypoxia for 24 hours. n = 6 in each group. **P < 0.01.

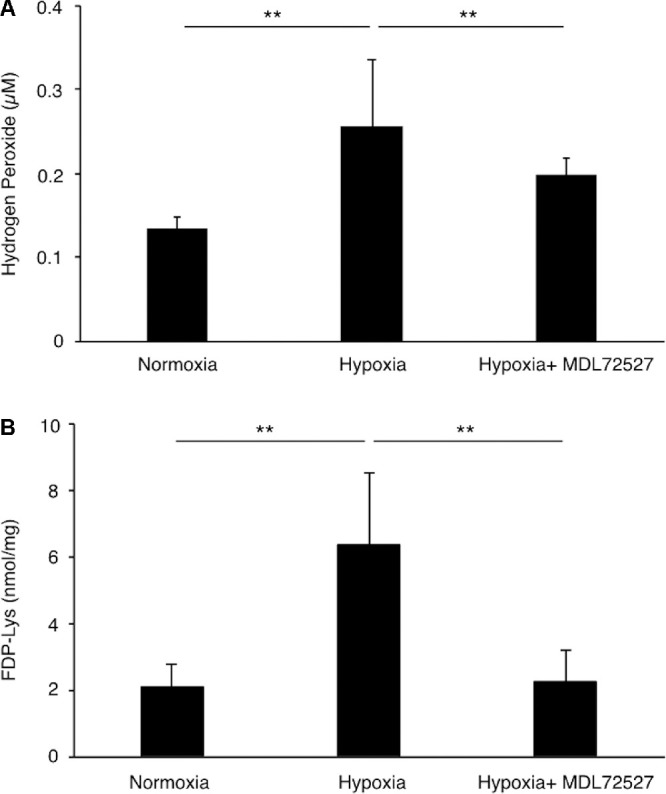

Production of Hydrogen Peroxide and FDP-Lys Mediated by SMOX under Hypoxic Condition in TR-MUL5 Cells

To investigate the role of SMOX in Müller glial cells under hypoxic condition, we measured the concentration of hydrogen peroxide and FDP-Lys, acrolein-conjugated protein, with or without the SMOX inhibitor (MDL72527) under hypoxic condition in TR-MUL5 cells. The concentration of hydrogen peroxide significantly increased in the supernatants of the TR-MUL5 cells under hypoxic condition for 24 hours, whereas their production was reduced by the SMOX inhibitor (Fig. 6A). In addition, FDP-Lys production significantly increased under hypoxic condition for 24 hours, which was suppressed by the SMOX inhibitor (Fig. 6B). These data indicated that SMOX induced by hypoxia participates in the production of hydrogen peroxide and FDP-Lys in retinal456 glial cells.

Figure 6.

Hydrogen peroxide and acrolein generation in TR-MUL5 cells under hypoxic condition (1% O2) for 24 hours. (A) Hydrogen peroxide and (B) FDP-Lys concentration in TR-MUL5 cells treated with or without SMOX inhibitor MDL72527. n = 6 in each group. **P < 0.01.

Discussion

In the present study, we obtained the following findings: (1) SMOX, a polyamine oxidase enzyme, is localized in retinal glial cells of fibrovascular tissues; (2) SMOX production increases in retinal glial cells under hypoxic condition; (3) HIF-1α is a regulator of SMOX induction in retinal glial cells when exposed to hypoxia; and (4) SMOX mediates productions of hydrogen peroxide and acrolein as byproducts in retinal glial cells. The current study provides evidence that hypoxia induces SMOX via HIF-1α signaling in retinal glial cells, presumably participating in fibrovascular proliferation in eyes with PDR.

Müller glial cells are the principal glial cell type in the retina that contribute to structural support and maintenance of the complex metabolism.21,22 However, in PDR, they provoke fibrovascular proliferation with propensities for migration,16,17 myofibroblastic transdifferentiation,23 and angiogenic activity.24,25 Therefore the activation mechanism of Müller glial cells in diabetic retinopathy should be investigated. In the current study, we primarily focused on SMOX induction in retinal glial cells because SMOX enzymatically generates 3-aminopropanal, the precursor of unsaturated aldehyde acrolein, which promotes cellular motility of cultured Müller glial cells during spermine oxidation.15

In the present study, we stained polyamine oxidation enzymes, including SMOX, SAT1, and PAOX, in fibrovascular tissues and demonstrated that SMOX was predominantly present in a cluster of glial cells in the fibrovascular tissues. In contrast, fluorescent staining signals of SAT1 and PAOX were faint. Consistent with the immunofluorescence data, the PCR data showed that all the polyamine oxidation enzymes are expressed in cultured Müller glial cells and hypoxic stimulation exclusively upregulates SMOX alone in cultured glial cells. In the advanced stage of diabetic retinopathy, obliteration of retinal microvasculature elicits a decrease in tissue oxygen concentration,26,27 and tissue hypoxia induces extensive cellular responses, including neovascularization, which eventually results in proliferative changes at the vitreoretinal surface in eyes with diabetic retinopathy. Hence fibrovascular tissues are theoretically deprived of adequate tissue oxygen. The current data indicated that SMOX is a predominant enzyme for spermine oxidation in glial cells migrated into fibrovascular tissues.

SMOX is a highly inducible enzyme in the polyamine catabolism cascade. SMOX expression is upregulated by inflammatory cytokines, including tumor necrosis factor-α and interleukin-6.28,29 In addition, dysregulation of SMOX alters intracellular polyamine levels and is associated with the progression of various human diseases, such as cancer,30,31 ulcerative colitis,32 stroke,33 and diabetes.34 With respect to ocular diseases, SMOX expression is upregulated in the retinal tissue of streptozotocin-induced diabetic mice.35 Additionally, the current study elucidated that hypoxia enhances SMOX production in retinal glial cells. In general, polyamines, including spermine, have been recognized as essential components for various cellular functions. Conversely, recent studies have demonstrated that polyamines are implicated in cell apoptosis36,37 and autophagy.38 Several studies showed that excessive spermine exerts cellular toxicity.39,40 Spermine oxidation by SMOX could be a common trigger for pathological changes in various diseases, including diabetic retinopathy.

Cellular activities in response to hypoxia, for instance, angiogenesis and erythropoiesis, are regulated via the highly conserved HIF family, consisting of heterodimers composed of one of the three α-subunits (HIF-1α, HIF-2α, or HIF-3α) and a β-subunit known as the aryl hydrocarbon nuclear translocator.41 Of these, HIF-1 is a heterodimeric basic helix-loop-helix transcription factor composed of two subunits, HIF-1α and HIF-1β.42 The HIF-1 complex recognizes HRE motifs in the promoter of a broad range of target genes.43 In the present study, Hif1a knockdown using the siRNA technique suppressed the increase in SMOX transcription, whereas Hif2a knockdown showed no suppressive effect on SMOX transcription, indicating that HIF-1, but not HIF-2, regulates transcriptional activity of SMOX in glial cells exposed to hypoxia. Furthermore, using luciferase assay, we demonstrated that HIF binding sites in the promoter region of SMOX are HRE2, HRE3, and HRE4. The luciferase assay data also supported that HIF-1 is a mediator of SMOX transcription in retinal glial cells under hypoxic condition.

Finally, the role of hypoxia-induced SMOX in retinal glial cells was, at least in part, elucidated in the present study. Hypoxic stimulation to cultured glial cells elevated the levels of hydrogen peroxide and FDP-Lys, both of which were abrogated by the potent SMOX inhibitor MDL72527, indicating that SMOX produces the two oxidative stress inducers through the enzymatic conversion of spermine to spermidine in retinal glial cells under hypoxic condition. Previous studies elucidated that both hydrogen peroxide and acrolein are implicated in a wide range of systemic diseases, such as Alzheimer disease,44 brain infarction,45 cardiovascular diseases,46 and diabetes.47,48 In eyes with PDR, FDP-Lys, a reactive intermediate that can covalently bind to thiols, including glutathione, through the retained electrophilic carbonyl moiety, accumulates in the vitreous14 and glial clusters of fibrovascular tissues13 in patients with PDR. Collectively, the previous and current data indicated that SMOX participates in the pathogenesis of PDR via increased production of cellular stressors. Future in vivo studies are warranted to further elucidate the pathological properties of SMOX in eyes of diabetic retinopathy.

Conclusions

The current study elucidated the SMOX induction system in retinal glial cells under hypoxic condition. One scientific significance of the present research is that it implies the involvement of SMOX in ischemic retinopathies, including retinal vein occlusion, retinopathy of prematurity, and diabetic retinopathy. To date, these diseases have been treated as vascular diseases; however, much attention has recently been paid to the neurodegenerative aspects of the diseases. Because SMOX has been recognized as a potential molecular target to prevent neurodegeneration in diabetic retinopathy,49 SMOX inhibition may have the potential for simultaneous therapeutic intervention, neuroprotection, and fibrovascular proliferation prevention in diabetic retinopathy.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Ikuyo Hirose, Shiho Yoshida, and Takashi Matsuda (Hokkaido University) for their skillful technical assistance.

Supported by Grant-in-Aid for Scientific Research (C) (18K09393, 17K11442) of the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science.

Disclosure: D. Wu, None; K. Noda, None; M. Murata, None; Y. Liu, None; A. Kanda, None; S. Ishida, None

References

- 1. Lee R, Wong TY, Sabanayagam C. Epidemiology of diabetic retinopathy, diabetic macular edema and related vision loss. Eye Vis (Lond). 2015; 2: 17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Adamis AP, Miller JW, Bernal MT, et al.. Increased vascular endothelial growth factor levels in the vitreous of eyes with proliferative diabetic retinopathy. Am J Ophthalmol. 1994; 118: 445–450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Heier JS, Korobelnik JF, Brown DM, et al.. Intravitreal aflibercept for diabetic macular edema: 148-week results from the VISTA and VIVID studies. Ophthalmology. 2016; 123: 2376–2385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Ip MS, Domalpally A, Sun JK, Ehrlich JS. Long-term effects of therapy with ranibizumab on diabetic retinopathy severity and baseline risk factors for worsening retinopathy. Ophthalmology. 2015; 122: 367–374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Heby O. Role of polyamines in the control of cell proliferation and differentiation. Differentiation. 1981; 19: 1–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Pegg AE. Toxicity of polyamines and their metabolic products. Chem Res Toxicol. 2013; 26: 1782–1800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Aikens D, Bunce S, Onasch F, Parker R 3rd, Hurwitz C, Clemans S. The interactions between nucleic acids and polyamines. II. Protonation constants and 13C-NMR chemical shift assignments of spermidine, spermine, and homologs. Biophys Chem. 1983; 17: 67–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Gawandi V, Fitzpatrick PF. The synthesis of deuterium-labeled spermine, N-acetylspermine and N-acetylspermidine. J Labelled Comp Radiopharm. 2007; 50: 666–670. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Sharmin S, Sakata K, Kashiwagi K, et al.. Polyamine cytotoxicity in the presence of bovine serum amine oxidase. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2001; 282: 228–235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Cervelli M, Leonetti A, Cervoni L, et al.. Stability of spermine oxidase to thermal and chemical denaturation: comparison with bovine serum amine oxidase. Amino Acids. 2016; 48: 2283–2291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Aldini G, Orioli M, Carini M. Protein modification by acrolein: relevance to pathological conditions and inhibition by aldehyde sequestering agents. Mol Nutr Food Res. 2011; 55: 1301–1319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Stevens JF, Maier CS. Acrolein: sources, metabolism, and biomolecular interactions relevant to human health and disease. Mol Nutr Food Res. 2008; 52: 7–25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Dong Y, Noda K, Murata M, et al.. Localization of acrolein-lysine adduct in fibrovascular tissues of proliferative diabetic retinopathy. Curr Eye Res. 2017; 42: 111–117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Murata M, Noda K, Kawasaki A, et al.. Soluble vascular adhesion protein-1 mediates spermine oxidation as semicarbazide-sensitive amine oxidase: possible role in proliferative diabetic retinopathy. Curr Eye Res. 2017; 42: 1674–1683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Murata M, Noda K, Yoshida S, et al.. Unsaturated aldehyde acrolein promotes retinal glial cell migration. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2019; 60: 4425–4435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Nork TM, Wallow IH, Sramek SJ, Anderson G. Muller's cell involvement in proliferative diabetic retinopathy. Arch Ophthalmol. 1987; 105: 1424–1429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Ohira A, de Juan E Jr. Characterization of glial involvement in proliferative diabetic retinopathy. Ophthalmologica. 1990; 201: 187–195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Biedermann B, Skatchkov SN, Brunk I, et al.. Spermine/spermidine is expressed by retinal glial (Muller) cells and controls distinct K+ channels of their membrane. Glia. 1998; 23: 209–220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Nicoletti R, Venza I, Ceci G, Visalli M, Teti D, Reibaldi A. Vitreous polyamines spermidine, putrescine, and spermine in human proliferative disorders of the retina. Br J Ophthalmol. 2003; 87: 1038–1042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Tomi M, Funaki T, Abukawa H, et al.. Expression and regulation of L-cystine transporter, system xc-, in the newly developed rat retinal Muller cell line (TR-MUL). Glia. 2003; 43: 208–217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Bringmann A, Pannicke T, Grosche J, et al.. Muller cells in the healthy and diseased retina. Prog Retin Eye Res. 2006; 25: 397–424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Willbold E, Layer PG. Muller glia cells and their possible roles during retina differentiation in vivo and in vitro. Histol Histopathol. 1998; 13: 531–552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Guidry C, Bradley KM, King JL. Tractional force generation by human muller cells: growth factor responsiveness and integrin receptor involvement. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2003; 44: 1355–1363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Ishida S, Shinoda K, Kawashima S, Oguchi Y, Okada Y, Ikeda E. Coexpression of VEGF receptors VEGF-R2 and neuropilin-1 in proliferative diabetic retinopathy. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2000; 41: 1649–1656. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Noda K, Ishida S, Shinoda H, et al.. Hypoxia induces the expression of membrane-type 1 matrix metalloproteinase in retinal glial cells. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2005; 46: 3817–3824. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Frank RN. Diabetic retinopathy. N Engl J Med. 2004; 350: 48–58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Sutherland FS, Stefansson E, Hatchell DL, Reiser H. Retinal oxygen consumption in vitro. The effect of diabetes mellitus, oxygen and glucose. Acta Ophthalmol (Copenh). 1990; 68: 715–720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Babbar N, Casero RA Jr. Tumor necrosis factor-alpha increases reactive oxygen species by inducing spermine oxidase in human lung epithelial cells: a potential mechanism for inflammation-induced carcinogenesis. Cancer Res. 2006; 66: 11125–11130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Cervelli M, Bellavia G, Fratini E, et al.. Spermine oxidase (SMO) activity in breast tumor tissues and biochemical analysis of the anticancer spermine analogues BENSpm and CPENSpm. BMC Cancer. 2010; 10: 555. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Goodwin AC, Jadallah S, Toubaji A, et al.. Increased spermine oxidase expression in human prostate cancer and prostatic intraepithelial neoplasia tissues. Prostate. 2008; 68: 766–772. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Snezhkina AV, Krasnov GS, Lipatova AV, et al.. The dysregulation of polyamine metabolism in colorectal cancer is associated with overexpression of c-Myc and C/EBPbeta rather than Enterotoxigenic Bacteroides fragilis infection. Oxid Med Cell Longev. 2016; 2016: 2353560. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Hong SK, Chaturvedi R, Piazuelo MB, et al.. Increased expression and cellular localization of spermine oxidase in ulcerative colitis and relationship to disease activity. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2010; 16: 1557–1566. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Tomitori H, Usui T, Saeki N, et al.. Polyamine oxidase and acrolein as novel biochemical markers for diagnosis of cerebral stroke. Stroke. 2005; 36: 2609–2613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Seghieri G, Gironi A, Niccolai M, et al.. Serum spermidine oxidase activity in patients with insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus and microvascular complications. Acta Diabetol Lat. 1990; 27: 303–308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Liu F, Saul AB, Pichavaram P, et al.. Pharmacological inhibition of spermine oxidase reduces neurodegeneration and improves retinal function in diabetic mice. J Clin Med. 2020; 9: 340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Lasbury ME, Merali S, Durant PJ, Tschang D, Ray CA, Lee CH. Polyamine-mediated apoptosis of alveolar macrophages during Pneumocystis pneumonia. J Biol Chem. 2007; 282: 11009–11020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Pignatti C, Tantini B, Stefanelli C, Flamigni F. Signal transduction pathways linking polyamines to apoptosis. Amino Acids. 2004; 27: 359–365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Chae YB, Kim MM. Activation of p53 by spermine mediates induction of autophagy in HT1080 cells. Int J Biol Macromol. 2014; 63: 56–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Del Rio B, Redruello B, Linares DM, et al.. Spermine and spermidine are cytotoxic towards intestinal cell cultures, but are they a health hazard at concentrations found in foods? Food Chem. 2018; 269: 321–326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Kaneko S, Ueda-Yamada M, Ando A, et al.. Cytotoxic effect of spermine on retinal pigment epithelial cells. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2007; 48: 455–463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Zamudio S, Wu Y, Ietta F, et al.. Human placental hypoxia-inducible factor-1alpha expression correlates with clinical outcomes in chronic hypoxia in vivo. Am J Pathol. 2007; 170: 2171–2179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Wang GL, Jiang BH, Rue EA, Semenza GL. Hypoxia-inducible factor 1 is a basic-helix-loop-helix-PAS heterodimer regulated by cellular O2 tension. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1995; 92: 5510–5514. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Zhong H, De Marzo AM, Laughner E, et al.. Overexpression of hypoxia-inducible factor 1alpha in common human cancers and their metastases. Cancer Res. 1999; 59: 5830–5835. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Huang YJ, Jin MH, Pi RB, et al.. Acrolein induces Alzheimer's disease-like pathologies in vitro and in vivo. Toxicol Lett. 2013; 217: 184–191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Saiki R, Nishimura K, Ishii I, et al.. Intense correlation between brain infarction and protein-conjugated acrolein. Stroke. 2009; 40: 3356–3361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. DeJarnett N, Conklin DJ, Riggs DW, et al.. Acrolein exposure is associated with increased cardiovascular disease risk. J Am Heart Assoc. 2014; 3: e000934. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Feroe AG, Attanasio R, Scinicariello F. Acrolein metabolites, diabetes and insulin resistance. Environ Res. 2016; 148: 1–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Zozulinska DA, Wierusz-Wysocka B, Wysocki H, Majchrzak AE, Wykretowicz A. The influence of insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus (IDDM) duration on superoxide anion and hydrogen peroxide production by polymorphonuclear neutrophils. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 1996; 33: 139–144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Narayanan SP, Shosha E, Palani CD. Spermine oxidase: a promising therapeutic target for neurodegeneration in diabetic retinopathy. Pharmacol Res. 2019; 147: 104299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]