Abstract

Background

The relationships between dietary intake of soybean products and incident hypertension were still uncertain. This study aimed to illustrate the associations between intake of soybean products with risks of incident hypertension and longitudinal changes of blood pressure in a prospective cohort study.

Methods

We included 67, 499 general Chinese adults from the Project of Prediction for Atherosclerosis Cardiovascular Disease Risk in China (China-PAR). Information about soybean products consumption was collected by standardized questionnaires, and study participants were categorized into the ideal (≥ 125 g/day) or non-ideal (< 125 g/day) group. Hazard ratios (HRs) and corresponding 95% confidence intervals (95% CIs) for incident hypertension were calculated using Cox proportional hazard models. Among participants with repeated measures of blood pressure, generalized linear models were used to examine the relationships between soybean products consumption and blood pressure changes.

Results

During a median follow-up of 7.4 years, compared with participants who consumed < 125 g of soybean products per day, multivariable adjusted HR for those in the ideal group was 0.73 (0.67-0.80). This inverse association remained robust across most subgroups while significant interactions were tested between soybean products intake and age, sex, urbanization and geographic region (P values for interaction < 0.05). The mean systolic and diastolic blood pressure levels were 1.05 (0.71-1.39) mmHg and 0.44 (0.22-0.66) mmHg lower among participants in the ideal group than those in the non-ideal group.

Conclusions

Our study showed that intake of soybean products might reduce the long-term blood pressure levels and hypertension incidence among Chinese population, which has important public health implications for primary prevention of hypertension.

Keywords: Blood pressure changes, Chinese population, Cohort study, Hypertension, Soybean products

1. Introduction

As a leading risk factor of disease burden, high systolic blood pressure (SBP) was accounting for 10.4 million deaths and 218 million disability-adjusted life-years (DALYs) in 2017 globally.[1] Given the aging population and the pervasion of modern lifestyles, we are expected to witness a continued increase of global prevalence of hypertension among adults from 26.4% in 2000 to 29.2% in 2025, and the number of adults with hypertension was predicted to increase by 60% to a total of 1.56 billion.[2] According to the data of China Hypertension Survey (2012-2015), 23.2% of Chinese adults were hypertensive[3] and caused approximately a quarter of global deaths and DALYs.[4] Therefore, the accompanying public health challenge is an essential issue to be solved urgently.

Soybean products have long been part of daily diet, and an impressive amount of studies has investigated its health effects during the past three decades.[5] Previous researches suggested that soybean products may be associated with reduced blood pressure (BP). However, discrepancies in conclusions still exist due to different designs of observational or clinical interventional studies, diverse characteristics of study populations, varying types of soybean products like tofu or isolated soy protein (ISP) or isoflavones extract, different manufacturing process, exposure durations, and consumption amounts.[6-12]

Moreover, soybean products are more likely to be taken as part of lifelong dietary pattern among Chinese population.[12-14] Cross-sectional investigations in the western populations yielded non-significant association between soy phytoestrogen consumption and BP.[15, 16] A longitudinal study among middle-aged and elderly Chinese women showed that soy protein intake was inversely associated with BP.[12] Nevertheless, evidence was limited on the associations of soybean products with risk of incident hypertension and longitudinal blood pressure changes among the Chinese population. Thus, additional epidemiologic studies are needed to clarify these inconsistencies among Chinese population.

Here, we aimed to investigate the association between usual intakes of total soybean products and risk of incident hypertension as well as longitudinal BP changes during follow-up among participants from the Prediction for Atherosclerotic Cardiovascular Disease (ASCVD) Risk in China (China-PAR), a large cohort study among general Chinese adults with a wide range of soybean products consumption levels.

2. Methods

2.1. Study population

The China-PAR project was initiated to investigate the epidemic of CVD and identify the risk factors among general Chinese adults, of which detailed description has been published elsewhere.[17] The currents study was based on three sub-cohorts of the China-PAR project with information on soybean products consumption, including the China Multi-Center Collaborative Study of Cardiovascular Epidemiology (China MUCA-1998), the International Collaborative Study of CVD in Asia (InterASIA), the Community Intervention of Metabolic Syndrome in China & Chinese Family Health Study (CIMIC). The China MUCA- 1998 cohort has been established since 1998, the InterASIA since 2001 and both were followed twice between 2007 to 2008, and 2012 to 2015, respectively. The CIMIC cohort was established during 2007 to 2008 and followed between 2012 and 2015. Participants were eligible for the present study if they attended the baseline survey and at least one follow-up examination, provided information on soybean products consumption, BP, and antihypertensive medication. Of the 113, 448 original participants, 8, 185 were lost to follow-up. We excluded 1, 896 participants who reported a history of CVD at baseline and 624 participants with missing data on soybean products consumption and 35, 244 with hypertension at baseline or missing information on BP. Finally, 67, 499 participants were available for the current study (Figure S1 in the supplementary material).

These preceding studies were approved by the Institutional Review Board at Fuwai Hospital and participating institutes. Informed consent was obtained from each participant prior to data collection.

2.2. Data collection and outcome measures

Information on age, gender, smoking and drinking status, physical activity, dietary habits and medical history was collected during field investigations by trained and certificated research staff using standard questionnaires at baseline. Soybean products consumption was measured by food frequency questionnaire. Participants were required to recall how frequently they consumed different soybean products, and the weight they consumed each time on average. The consumption amount was measured by the weight of tofu, and the amounts of other types (soy milk, bean curd, etc.) were converted into tofu based on the percent of soy protein content according to China Food Composition.[18] BP and anthropometric measurements were collected by trained and certified observers following standard protocols and technique during baseline clinical examination.[19] Participants were required to avoid cigarette smoking, alcohol, caffeinated beverages, and exercise for at least 30 min, and then three BP readings were obtained in a seated position after 5 min of rest. The average of the three BP measurements was employed in the analysis. Follow-up examinations included standardized questionnaires; physical examination followed the same practice protocols as the baseline.

2.3. Statistical methods

The daily consumption amounts of soybean products were categorized into the ideal (≥ 125 g/day) or non-ideal (< 125 g/day) group. This cut-point was chosen based on the recommendation of Dietary Guidelines for Chinese Residents.[20] Hypertension was defined as SBP ≥ 140 mmHg, and/or diastolic BP (DBP) ≥ 90 mmHg, and/or use of antihypertensive medication within the previous two weeks.[21] Incident cases were defined as participants who were identified as hypertensive during the follow-up surveys or reported use of anti-hypertension medication among those without hypertension at baseline. The number of person- years of follow-up was calculated from the date of baseline survey until date of identification of incident hypertension, start date of antihypertensive medication therapy, or the date of the last follow-up interview.

Differences in means and proportions of baseline characteristics according to soybean products intake categories were tested by t-test for continuous variables and chi-square test for categorical variables. Cox regression was used to calculate hazard ratios (HRs) and corresponding 95% confidence intervals (CIs) in relation to soybean products consumption. The following variables were adjusted stepwise in multivariable models: age (continuous), sex (men/women), region (north/south), area (rural/urban), cohort (InterASIA/China MUCA-1998/CIMIC), education level (≥ 12 years or not), family history of hypertension (yes or no), smoking (yes or no), alcohol drinking (yes or no), physical activity level (ideal or not), other dietary factors (including fresh fruits and vegetables, red meat, fish, and tea, ideal or not), body mass index (BMI) and baseline SBP. Definitions for ideal physical activity level and other dietary factor were described in detail elsewhere.[22] Restricted cubic splines were further employed to explore potential dose-response association between the daily consumption amounts of soybean products as a continuous variable and the risk of incident hypertension. After further exclusion of 902 participants at the first follow-up and 4, 649 participants at the second follow-up who were taking antihypertensive drugs, we also examine the relations of soybean products consumption to mean differences of BP levels during follow-up using generalized linear models among participants with repeated measures of BP. Subgroup analyses were carried out based on baseline characteristics and the interactions between soybean products consumption categories and baseline characteristics were also examined by adding product terms into multivariable models. A supplementary comparison of baseline characteristic was also conducted between included participants and those excluded because of loss to follow-up or missing information.

Statistical analyses were performed using SAS statistical package (version 9.4. SAS Institute, Inc., Cary, NC). All tests were two-sided, and P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

3. Results

The baseline characteristics are presented by soybean products consumption categories in Table 1. A total of 67, 499 participants accomplished the follow-up survey, with a median follow-up period of 7.4 years. Overall, 3, 679 (5.45%) consumed soybean products ≥ 125 g/day and 63, 820 (94.55%) < 125 g/day. Participants with higher soybean products intake were more likely to be older, physical active, be southern and rural residents, non-smokers, habitual drinkers, and to have lower prevalence of family history of hypertension, longer school education years, higher BMI and lower BP at baseline. Higher soybean products intake was also associated with the intake of fresh fruits and vegetables, fish, and tea. A total of 13, 123 participants developed hypertension during follow-up, with an overall incidence of 26.4/1000 person-years, 21.3/1000 person-years, and 26.7/ 1000 person-years among those with 125 g/day soybean product intake or not, separately.

1.

Baseline characteristics of study participants by soybean products consumption categories.

| All participants (n = 67, 499) | < 125 g/day (n = 63, 820) | ≥ 125 g/day (n = 3, 679) | P-value | |

| Continuous variables are presented as mean ± SD and categorical variables as percentage. BMI: body mass index; DBP: diastolic blood pressure; SBP: systolic blood pressure. | ||||

| Age, yrs | 48.78 ± 11.98 | 48.71 ± 11.94 | 49.91 ± 12.63 | < 0.0001 |

| Male, % | 39.47 | 39.45 | 39.93 | 0.5592 |

| Northern, % | 42.81 | 43.43 | 32.02 | < 0.0001 |

| Urban, % | 9.83 | 10.15 | 4.4 | < 0.0001 |

| Smokers, % | 26.51 | 26.61 | 24.94 | 0.0261 |

| Habitual drinkers, % | 18.05 | 17.91 | 20.53 | < 0.0001 |

| Family history of hypertension, % | 23.15 | 23.31 | 20.30 | < 0.0001 |

| School education ≥ 12 years, % | 15.62 | 15.57 | 16.46 | 0.1478 |

| Physical active, % | 69.23 | 68.68 | 78.73 | < 0.0001 |

| Fresh fruits and vegetables ≥ 500 g/day, % | 45.19 | 44.92 | 49.88 | < 0.0001 |

| Red meat ≤ 50 g/day, % | 86.51 | 86.49 | 86.79 | 0.6143 |

| Fish ≥ 200 g/week, % | 37.36 | 36.79 | 47.24 | < 0.0001 |

| Tea ≥ 50 g/month, % | 24.68 | 24.86 | 21.55 | < 0.0001 |

| BMI, kg/m2 | 23.05 ± 3.33 | 23.04 ± 3.32 | 23.31 ± 3.39 | < 0.0001 |

| SBP, mmHg | 117.11 ± 11.51 | 117.15 ± 11.52 | 116.39 ± 11.35 | < 0.0001 |

| DBP, mmHg | 73.48 ± 8.01 | 73.54 ± 7.99 | 72.32 ± 8.32 | < 0.0001 |

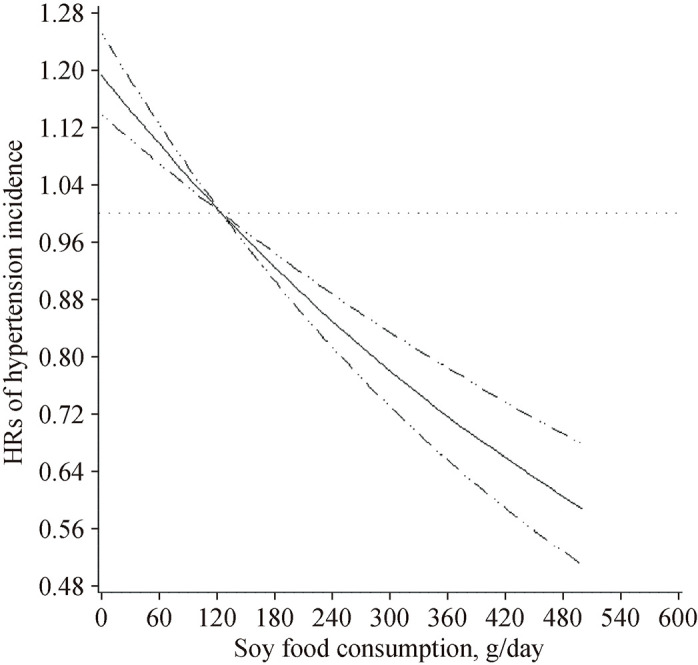

Soybean products intake was inversely associated with the risk of incident hypertension. Compared with participants who consumed < 125 g of soybean products per day, HR for those who consumed soybean products ≥ 125 g/day was 0.85 (95% CI: 0.77-0.92) after adjustment of age, sex, baseline BMI and SBP. Further adjustment of geographic region, urbanization, cohort sources, education level, family history of hypertension, smoking and drinking status, and physical activity level, the inverse association was strengthened, with HR of 0.73 (95% CI: 0.67-0.80). Adjusting for other dietary factors in the model, it did not make substantial changes to the observed association. In addition, analysis used restricted cubic splines indicated a linear, dose-response relation between soybean products consumption and incident hypertension (P-linear < 0.0001) (Figure 1).

1.

The dose-response analysis between consumption amounts of soybean products and HRs of hypertension incidence.

The middle line and upper and lower line represent the estimated HRs and its 95% confidence interval, respectively. HRs: hazard ratios.

There were significant interactions between soybean products intake and age, sex, urbanization and geographic region (P for interaction < 0.05). For example, compared with participants who consumed < 125 g soybean products per day, the multivariable adjusted HRs were 0.67 (95% CI: 0.59-0.76) for those consumed at least 125 g/day among women, and 0.81 (95% CI: 0.72-0.92) among men, respectively (P for interaction = 0.0056) (Figure 2).

2.

HRs of overall incidence of hypertension associated with ideal intake of soybean products (≥ 125 g/day).

Adjusted for age, sex, baseline BMI and SBP, geographic region, urbanization, cohort sources, education level, family history of hypertension, smoking and drinking status, and physical activity level. The black boxes represent hazard ratios and the horizontal lines represent 95% confidence interval. BMI: body mass index; SBP: systolic blood pressure.

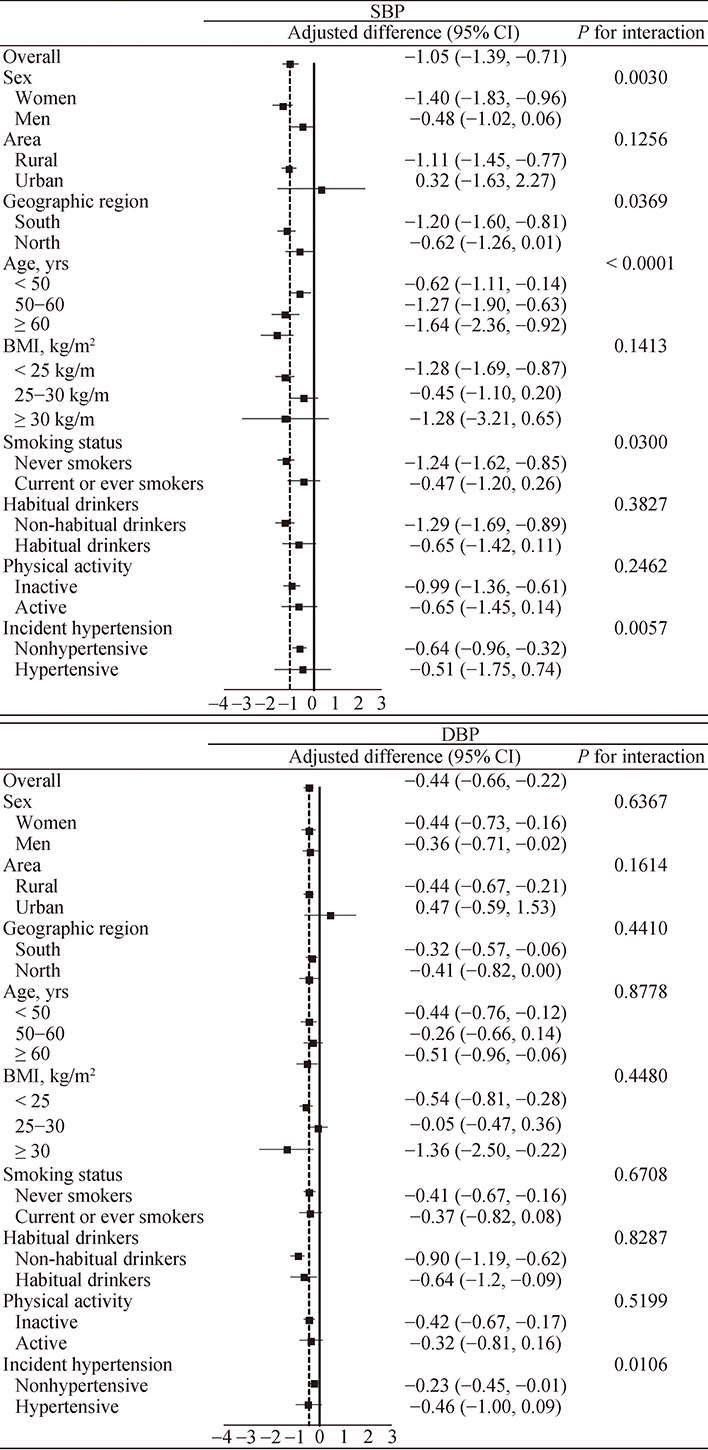

Ideal soybean products consumption was also inversely associated with both SBP and DBP levels (Figure 3). The multivariable adjusted mean SBP was 1.05 mmHg lower (95% CI: 0.71-1.39) and the mean DBP was 0.44 mmHg lower (95%CI: 0.22-0.66) among participants who consumed soybean products ≥ 125 g/day than those who consumed < 125 g/day. There were interactive effects between soybean products intake with sex, geographic region, age, and smoking status for SBP (All P for interaction < 0.05). For example, mean SBP was 1.40 mmHg (95% CI: 0.96- 1.83) lower among women who consumed ≥ 125 g/day soybean products than those who consumed < 125 g/day, while the SBP difference was much feeble and did not reach statistical significance among men. In addition, the association of soybean products intake with mean BP levels was more evident among those who did not develop hypertension during follow-up (P for interaction < 0.05 for both SBP and DBP).

3.

Changes in SBP and DBP (mmHg) during a median follow-up period of 7.4 years with ideal intake of soybean products (≥ 125 g/day).

Adjusted for age, sex, baseline BMI and SBP, geographic region, urbanization, cohort sources, education level, family history of hypertension, smoking and drinking status, and physical activity level. The black boxes represent changes in SBP and DBP and the horizontal lines represent 95% confidence intervals. DBP: diastolic blood pressure; SBP: systolic blood pressure.

In addition, compared with the included participants, the excluded ones were younger, more likely to be northern and urban residents, reported less family history of hypertension, more likely to be smokers, physical inactive and have higher BMI; they tended to eat more red meat, less fish and more soybean products; they also had higher baseline SBP and DBP levels.

4. Discussion

By employing data from large perspective cohorts, the present study illustrated the association between intake of soybean products and the risk of hypertension among general Chinese adults. At least 125 g/day intake of soybean products was associated with a 27% lower risk of incident hypertension, as well as 1.05 mmHg and 0.44 mmHg lower of SBP and DBP among apparently healthy Chinese adults during a median follow-up period of 7.4 years. These findings suggested that soybean products intake might be a healthy dietary choice for primary prevention against high BP.

The inverse associations between soybean products consumption and BP were biologically plausible. Soy and some of its important constituents, such as soy protein, isoflavones, phytosterols and lecithin, have been suggested to lower risk for high BP through improving endogenous nitric oxide production, promoting vasodilation, scavenging the free radicals, and relieving oxidative stress.[23-27] However, in vitro and animal studies do not duplicate the complexity of soybean products in their natural milieu, or others and thus, are of doubtful relevance to understanding the effects of soybean products in humans.

Some previous clinical studies have investigated the effect of soybean products on BP while inconsistencies still exist and deserve discussion. In the current study, mean SBP and DBP was 1.05 mmHg and 0.44 mmHg lower among participants with soybean products intake ≥ 125 g/day than those < 125 g/day, which was similar with those from randomized controlled trials (RCTs).[7-11] Different pooled analyses of previous RCTs showed that SBP and DBP were reduced by approximately 1.6 to 5.8 mmHg and 0 to 2.0 mmHg among soybean products, ISP or soy isoflavone extract treatment groups.[7-11] However, only a few of the original trials in the pooled analysis produced robust reductions in response to soybean products interventions while the vast majority reported only modest or non-significant reductions.[28-33] Unlike the assessment of traditional soybean products in this study, most of the trials focused on ISP or soy isoflavone extract, which neglected the effects of other soy components and their potential interactions. Differences in characteristics of the study participants, exposure durations and dosages also accounted for the discrepancies.

Despite large amounts trials, findings from epidemiologic studies with long observation periods are scanty. Results of the Shanghai Women's Health Study (SWHS) showed that the usual soy food intake at baseline was inversely associated with both SBP and DBP levels measured two or three years later. The reported mean differences were 1.9 mmHg and 0.9 mmHg lower of SBP/DBP among women with ≥ 25 g/day soy protein intake compared with those with < 25 g/day, which was strengthened among older and postmenopausal women.[12] In the current study, we found that soybean product intake was associated 1.05/0.44 mmHg lower of SBP/DBP among participants with 125 g/d intake compared with those who took less or none, and the protective effect against longitudinal BP increase was more pronounced among women. In addition, we found that 125 g/d soybean product intake was associated with 27% lower risk of hypertension. Soybean product intake was reported to be inversely associated with the development of high BP during the 5-year follow-up among middle-aged Japanese men and women with normal BP at baseline.[6] However, the result was only significant for fermented soy products like miso and natto, but not unfermented soy products (tofu).

There was an observed contrast between the strength of the association between soy intake and the reduced risk of developing hypertension, and the moderate magnitude of BP difference between people with high and low soy intake during follow-up. We considered it as a reflection of regression to the mean. In other words, participants with higher baseline BP levels were more likely to develop hypertension during follow-up, while their BP only needed to increase less to reach the diagnostic criteria or 140/90 mmHg.

Several other factors were observed to interact with soybean product intake on the risk of hypertension or BP changes. We found that intake of soybean products (≥ 125 g/day) could reduce the risk of incident hypertension for both sexes while the inverse association was strengthened among women. The risk of incident hypertension was reduced by 32% among women with soybean products intake (≥ 125 g/day) and by 19% among men, compared with those who took soybean products < 125 g/day (P for interaction = 0.0056). However, sex differences were detected in previous cross-sectional investigations in China and Japan, and they found that intake of soybean products was only inversely associated with BP levels only in men but not in women.[34, 35] These sex-differences could be result from the estrogen-like activity of soy isoflavones[36, 37] and the inconsistencies might be due to different risk factor and hypertension prevalence in different populations. We also notified interactions between soybean product intake and baseline residential areas and geographic regions. Hypertension incidence has been higher in northern China than that in southern China due to complex reasons including high-salt and high-energy diet, higher prevalence of obesity, higher alcohol consumption, lack of calcium and vitamin D, and cold weather, etc. The effects of all these risk factors might cover or weaken the observed effect of soybean products. In addition, the northern residents consumed less soybean products than the southern residents, which might also influence then statistical power. While for the residential areas, the main reason might be the limited number of individuals in urban areas. Further studies are still needed to confirm and clarify the interactions between baseline characteristics and intake of soybean products.

One of strengths of this study is that the large sample size of participants with a wide range of soybean products consumption allowed us to evaluate the effect of usual soybean products intake on hypertension in general populations. Rigorous field survey carried out by trained and certificated staff also guaranteed the data quality. However, several limitations of the current study should also be noted. First, the weight conversion and uniform across different soybean products in the current study was solely based on the constituent of soy protein. Thus, we could not differentiate the effects of other soy constituents like isoflavones, dietary fibers, and the potential interactions in between. Second, we used questionnaires to collect information on soybean intake instead of objective measurements, and meanwhile it was hard to obtain accurate date of hypertension incidence in a cohort study with limited follow-up surveys out of clinical setting. However, such memory deviations relating to exposure and outcome were unlikely to be associated with other. Thus, they might not serve as systematically recall bias or influence the results. Third, the younger age, higher intake of soybean products, and higher baseline BP levels of excluded participants might lead to slightly overestimation of the association. However, the small number of excluded participants might play only a limited role. In addition, we did not collect information regarding to the fermentation type of soybean products. Though the Japanese study showed that only fermented soybean products (natto and miso) could reduce the risk of high BP, our results were mainly based on unfermented soybean products (tofu, bean curd and soymilk, etc., which were the main consumed type in China). However, natto and miso are mainly consumed in Japan, and the local fermented soybean products (soy pasta or stinky tofu) are consumed much fewer in weight. Third, we could not rule out residual confounding despite the adjustment of a wide range of confounders. For example, we failed to collect information on dietary salt intake which had an obvious influence on blood pressure level.

In conclusion, we found that soybean products consumption could reduce the risk of incident hypertension and slower the longitudinal BP increase. As the leading risk factor of CVD, premature deaths and disease burden, even small change of BP is of great public health significance.[38] Our results indicated that soybean products intake might be a healthy dietary choice and provided direct scientific evidence for primary prevention of hypertension through dietary guidance among Chinese population.

Acknowledgements

We thank the staffs and participants of the China-PAR project for their important participation and contribution. This work was supported by the Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences (CAMS) Innovation Fund for Medical Sciences (2017-I2M-1-004, 2019-I2M-2-003), National Key Research & Development Program of China (2017YFC02 11700), and National Natural Science Foundation of China (91843302). The authors declared no conflicts of interest.

SUPPLEMENTARY DATA

Supplementary data to this article can be found online.

References

- 1.Global, regional, and national comparative risk assessment of 84 behavioural, environmental and occupational, and metabolic risks or clusters of risks for 195 countries and territories, 1990-2017: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2017. Lancet 2018; 392: 1923–1994.

- 2.Kearney PM, Whelton M, Reynolds K, et al. Global burden of hypertension: analysis of worldwide data. Lancet. 2005;365:217–223. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)17741-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wang Z, Chen Z, Zhang L, et al. Status of Hypertension in China: Results From the China Hypertension Survey, 2012- 2015. Circulation. 2018;137:2344–2356. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.117.032380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.WHO. GBD Compare Data Visualization. Vol 2019, p. GBD Compare Data Visualization.

- 5.Messina M. Soy and Health Update: Evaluation of the Clinical and Epidemiologic Literature. Nutrients. 2016;8:754. doi: 10.3390/nu8120754. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nozue M, Shimazu T, Sasazuki S, et al. Fermented Soy Product Intake Is Inversely Associated with the Development of High Blood Pressure: The Japan Public Health Center- Based Prospective Study. J Nutr. 2017;147:1749–1756. doi: 10.3945/jn.117.250282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mohammadifard N, Salehi-Abargouei A, Salas-Salvado J, et al. The effect of tree nut, peanut, and soy nut consumption on blood pressure: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled clinical trials. Am J Clin Nutr. 2015;101:966–982. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.114.091595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Taku K, Lin N, Cai D, et al. Effects of soy isoflavone extract supplements on blood pressure in adult humans: systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized placebo-controlled trials. J Hypertens. 2010;28:1971–1982. doi: 10.1097/HJH.0b013e32833c6edb. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Liu XX, Li SH, Chen JZ, et al. Effect of soy isoflavones on blood pressure: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Nutr Metab Cardiovasc Dis. 2012;22:463–470. doi: 10.1016/j.numecd.2010.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dong JY, Tong X, Wu ZW, et al. Effect of soya protein on blood pressure: a meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. Br J Nutr. 2011;106:317–326. doi: 10.1017/S0007114511000262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hooper L, Kroon PA, Rimm EB, et al. Flavonoids, flavonoid-rich foods, and cardiovascular risk: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Am J Clin Nutr. 2008;88:38–50. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/88.1.38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yang G, Shu XO, Jin F, et al. Longitudinal study of soy food intake and blood pressure among middle-aged and elderly Chinese women. Am J Clin Nutr. 2005;81:1012–1017. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/81.5.1012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Keinan-Boker L, Peeters PH, Mulligan AA, et al. Soy product consumption in 10 European countries: the European Prospective Investigation into Cancer and Nutrition (EPIC) study. Public Health Nutr. 2002;5:1217–1226. doi: 10.1079/PHN2002400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Liu Z, Li W, Sun J, et al. Intake of soy foods and soy isoflavones by rural adult women in China. Asia Pac J Clin Nutr. 2004;13:204–209. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Goodman-Gruen D, Kritz-Silverstein D. Usual dietary isoflavone intake is associated with cardiovascular disease risk factors in postmenopausal women. J Nutr. 2001;131:1202–1206. doi: 10.1093/jn/131.4.1202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.de Kleijn MJ, van der Schouw YT, Wilson PW, et al. Dietary intake of phytoestrogens is associated with a favorable metabolic cardiovascular risk profile in postmenopausal U.S. women: the Framingham study. J Nutr. 2002;132:276–282. doi: 10.1093/jn/132.2.276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yang X, Li J, Hu D, et al. Predicting the 10-Year Risks of Atherosclerotic Cardiovascular Disease in Chinese Population: The China-PAR Project (Prediction for ASCVD Risk in China) Circulation. 2016;134:1430–1440. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.116.022367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yang Y, Wang G, Pan X. China Food Composition, 2ed. Peking University Medical Press, 2009.

- 19.Perloff D, Grim C, Flack J, et al. Human blood pressure determination by sphygmomanometry. Circulation. 1993;88:2460–2470. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.88.5.2460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wang SS, Lay S, Yu HN, et al. Dietary Guidelines for Chinese Residents (2016): comments and comparisons. J Zhejiang Univ Sci B. 2016;17:649–656. doi: 10.1631/jzus.B1600341. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chobanian AV, Bakris GL, Black HR, et al. The Seventh Report of the Joint National Committee on Prevention, Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Pressure: the JNC 7 report. JAMA. 2003;289:2560–2572. doi: 10.1001/jama.289.19.2560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Han C, Liu F, Yang X, et al. Ideal cardiovascular health and incidence of atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease among Chinese adults: the China-PAR project. Sci China Life Sci. 2018;61:504–514. doi: 10.1007/s11427-018-9281-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ramdath DD, Padhi EM, Sarfaraz S, et al. Beyond the cholesterol-lowering effect of soy protein: a review of the effects of dietary soy and its constituents on risk factors for cardiovascular disease. Nutrients. 2017;9:324. doi: 10.3390/nu9040324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jackson RL, Greiwe JS, Schwen RJ. Emerging evidence of the health benefits of S-equol, an estrogen receptor beta agonist. Nutr Rev. 2011;69:432–448. doi: 10.1111/j.1753-4887.2011.00400.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Haddad Tabrizi S, Haddad E, Rajaram S, et al. The Effect of Soybean Lunasin on Cardiometabolic Risk Factors: A Randomized Clinical Trial. J Diet Suppl. 2019:1–14. doi: 10.1080/19390211.2019.1577937. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Liu J, Jia SH, Kirberger M, et al. Lunasin as a promising health-beneficial peptide. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci. 2014;18:2070–2075. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Guang C, Chen J, Sang S, et al. Biological functionality of soyasaponins and soyasapogenols. J Agric Food Chem. 2014;62:8247–8255. doi: 10.1021/jf503047a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Teede HJ, Dalais FS, Kotsopoulos D, et al. Dietary soy has both beneficial and potentially adverse cardiovascular effects: a placebo-controlled study in men and postmenopausal women. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2001;86:3053–3060. doi: 10.1210/jcem.86.7.7645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rivas M, Garay RP, Escanero JF, et al. Soy milk lowers blood pressure in men and women with mild to moderate essential hypertension. J Nutr. 2002;132:1900–1902. doi: 10.1093/jn/132.7.1900. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sagara M, Kanda T, M NJ, et al. Effects of dietary intake of soy protein and isoflavones on cardiovascular disease risk factors in high risk, middle-aged men in Scotland. J Am Coll Nutr. 2004;23:85–91. doi: 10.1080/07315724.2004.10719347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.He J, Gu D, Wu X, et al. Effect of soybean protein on blood pressure: a randomized, controlled trial. Ann Intern Med. 2005;143:1–9. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-143-1-200507050-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Welty FK, Lee KS, Lew NS, et al. Effect of soy nuts on blood pressure and lipid levels in hypertensive, prehypertensive, and normotensive postmenopausal women. Arch Intern Med. 2007;167:1060–1067. doi: 10.1001/archinte.167.10.1060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Liu ZM, Ho SC, Chen YM, et al. Effect of soy protein and isoflavones on blood pressure and endothelial cytokines: a 6-month randomized controlled trial among postmenopausal women. J Hypertens. 2013;31:384–392. doi: 10.1097/HJH.0b013e32835c0905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Nagata C, Shimizu H, Takami R, et al. Association of blood pressure with intake of soy products and other food groups in Japanese men and women. Prev Med. 2003;36:692–697. doi: 10.1016/S0091-7435(03)00052-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Pan A, Franco OH, Ye J, et al. Soy protein intake has sex- specific effects on the risk of metabolic syndrome in middle- aged and elderly Chinese. J Nutr. 2008;138:2413–2421. doi: 10.3945/jn.108.097519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Setchell KDR. The history and basic science development of soy isoflavones. Menopause. 2017;24:1338–1350. doi: 10.1097/GME.0000000000001018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hooper L, Ryder JJ, Kurzer MS, et al. Effects of soy protein and isoflavones on circulating hormone concentrations in pre- and post-menopausal women: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Hum Reprod Update. 2009;15:423–440. doi: 10.1093/humupd/dmp010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Stamler R. Implications of the INTERSALT study. Hypertension. 1991;17:I16–I20. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.17.1_Suppl.I16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary data to this article can be found online.