Abstract

Objective

To assess the impact of separation of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) polymerase chain reaction (PCR)-positive mother–newborn dyads on breastfeeding outcomes.

Study design

This observational longitudinal cohort study of mothers with SARS-CoV-2 PCR-and their infants at 3 NYU Langone Health hospitals was conducted between March 25, 2020, and May 30, 2020. Mothers were surveyed by telephone regarding predelivery feeding plans, in-hospital feeding, and home feeding of their neonates. Any change prompted an additional question to determine whether this change was due to coronavirus disease-2019 (COVID-19).

Results

Of the 160 mother–newborn dyads, 103 mothers were reached by telephone, and 85 consented to participate. There was no significant difference in the predelivery feeding plan between the separated and unseparated dyads (P = .268). Higher rates of breastfeeding were observed in the unseparated dyads compared with the separated dyads both in the hospital (P < .001) and at home (P = .012). Only 2 mothers in each group reported expressed breast milk as the hospital feeding source (5.6% of unseparated vs 4.1% of separated). COVID-19 was more commonly cited as the reason for change in the separated group (49.0% vs 16.7%; P < .001). When the dyads were further stratified by symptom status into 4 groups—asymptomatic separated, asymptomatic unseparated, symptomatic separated, and symptomatic unseparated—the results remained unchanged.

Conclusions

In the setting of COVID-19, separation of mother–newborn dyads impacts breastfeeding outcomes, with lower rates of breastfeeding both during hospitalization and at home following discharge compared with unseparated mothers and infants. No evidence of vertical transmission was observed; 1 case of postnatal transmission occurred from an unmasked symptomatic mother who held her infant at birth.

Keywords: SARS-CoV-2, breastfeeding, isolation precautions, mother–baby separation

Abbreviations: AAP, American Academy of Pediatrics; BH, NYU Langone Hospital-Brooklyn; CDC, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; COVID-19, Coronavirus disease-2019; LOS, Length of stay; NICU, Neonatal intensive care unit; NYULH, NYU Langone Health; PCR, Polymerase chain reaction; SARS-CoV-2, Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2; TH, Tisch Hospital; WH, Winthrop Hospital; WHO, World Health Organization

The novel severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2), responsible for coronavirus disease-2019 (COVID-19), has spread globally, reaching pandemic status on March 11, 2020.1 Cases of COVID-19 in New York State reached a peak in April 2020, with more than 386 000 cases and 24 000 deaths recorded by June 2020.2 , 3

Early in the COVID-19 pandemic, limited data existed regarding the risk of adverse outcomes for pregnant women infected with SARS-CoV-2, and the risk of vertical or horizontal transmission to their newborns was unknown. Given the uncertainty surrounding potential transmission from an infected mother to her neonate, early guidance relied on a cautious approach and recommended separation of mother–newborn dyads to minimize the risk of transmission. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) and American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) each published interim guidelines for the management of neonates born to mothers with confirmed or suspected COVID-19, including recommendations for temporary separation of these dyads.4 , 5 Given the lack of evidence demonstrating SARS-CoV-2 transmission in breast milk, both the AAP and CDC recommended expression of breast milk after meticulous hand hygiene and feeding of the expressed milk to separated neonates by designated caregivers.4 , 5 In contrast, the World Health Organization (WHO) issued guidance supporting direct breastfeeding for all mothers with COVID-19, both asymptomatic and symptomatic, except in cases of severe illness or another complication that would inhibit care of the infant or interfere with breastfeeding.6

Recognizing the paucity of evidence, and with a goal of limiting exposure of neonates, the NYU Langone Health system (NYULH) issued early internal guidance recommending separating these mother–newborn dyads at birth. In line with the recommendations of the AAP and CDC, the NYULH guidelines advocated expression of breast milk for mothers intending to breastfeed, with bottle-feeding by designated caregivers.

We recognize the importance of breastfeeding and advocate for supportive environments and policies to facilitate breastfeeding, including early skin-to-skin contact and rooming-in.7 , 8 At 6 weeks after our initial local guidelines were published, they were modified to allow asymptomatic mothers who were SARS-CoV-2 polymerase chain reaction (PCR)-positive to room-in with their infants while wearing masks and using proper hand hygiene techniques. In addition, our local policy was changed to allow and encourage mothers to feed their infants directly on the breast, if desired.

Given the potential impact of policies on transmission, health, and breastfeeding behavior, we recognize the importance of validating policies, with the goal of informing future guidance. To assess the impact of our policy change regarding mother–newborn dyad separation on breastfeeding rates, we evaluated mothers' predelivery plans for feeding and compared these with actual outcomes of breastfeeding during perinatal admission and following discharge.

Methods

For this observational longitudinal cohort study, we studied mother–newborn dyads at 3 NYULH hospitals between March 25, 2020, and May 30, 2020. The NYULH Institutional Review Board approved this study. Tisch Hospital (TH) is a university-based tertiary and quaternary hospital in Manhattan with more than 6000 births annually, NYU-Winthrop Hospital (WH) is a tertiary hospital in Nassau County (a suburb of New York City) with more than 5000 annual births, and NYU Langone Hospital-Brooklyn (BH) is an academic hospital in Brooklyn with more than 4000 annual births.9 All 3 hospitals are designated as Baby-Friendly Hospitals through the Baby Friendly Hospital Initiative, led jointly by the WHO and United Nations International Children's Emergency Fund (UNICEF), and both TH and WH are designated by New York State as regional perinatal centers. The published baseline breastfeeding rates of infants being fed any breast milk and those exclusively breastfed during hospitalization are 97.7% and 89.8% at TH, 85.5% and 44.2% at WH, and 89.8% and 38.6% at BH.9

Dyads were identified by NYULH Datacore services and were included in the study if all the following inclusion criteria were met: maternal age ≥18 years, positive maternal SARS-CoV-2 PCR test by nasopharyngeal swab, and SARS-CoV-2 PCR test by nasopharyngeal swab performed on the infant (regardless of test result). Background demographic and clinical data for these dyads was obtained through the Electronic Privacy Information Center (EPIC) electronic medical record system and stored, deidentified, in a secure database. Maternal baseline characteristics included age, ethnicity, race, gravidity, parity, type of delivery, reason for delivery, health status after delivery, symptoms of COVID-19, medications for COVID-19, and contraindication to breastfeeding. Neonatal characteristics included gestational age, sex, anthropometric measurements at birth, Apgar scores, admission to a newborn nursery or neonatal intensive care unit (NICU), body temperature during hospitalization, presence of comorbidities including respiratory distress or temperature derangements, and timing of SARS-CoV-2 nasopharyngeal swab testing. Additional baseline data collected included whether a lactation consultation was obtained, the type of isolation precautions used, and the type of separation of the dyad.

Mothers were contacted by telephone between May 27, 2020, and June 17, 2020, by 1 of the investigators to obtain consent and authorization for voluntary participation in the telephone study. Three attempts were made to contact each mother. If contact was made and the mother consented to participate, the investigator proceeded to ask how she had planned to feed her infant before delivery, how the infant had been fed during hospitalization following delivery, and how the infant had been fed since discharge from the hospital. For each question, the following 4 answer choices were offered: breastfeeding, expressed breast milk, formula, or mixed feeding. If a change in feeding type between predelivery plan, hospital feeding, or home feeding was identified, the mother was asked about the reason for the change and whether this change was due to COVID-19.

Statistical Analyses

Descriptive statistics (mean ± SD or median and IQR for continuous variables; frequencies and percentages for categorical variables) were calculated for the sample of mothers and neonates separately. The χ2 test or Fisher exact test, as deemed appropriate, was used to compare those who were separated from those who were not separated for categorical variables. The analysis of total length of stay (LOS) was accomplished by applying standard methods of survival analysis, that is, computing the Kaplan–Meier product limit curves, with group (NICU and newborn nursery) as the stratification variable.10 No data were considered censored. The 2 groups were compared using the log-rank test. The median total LOS was obtained from the Kaplan–Meier/product-limit estimates and their corresponding 95% CIs were computed using the Greenwood formula to calculate the standard error.11 A result was considered statistically significant at the P < .05 level of significance. All analyses were performed using SAS version 9.4 (SAS Institute, Cary, North Carolina).

Results

Baseline Characteristics

A combined total of 160 mother–newborn dyads from the 3 hospitals met the study's inclusion criteria and were included in the baseline characteristic cohort. Of these, 80 dyads were identified at WH, 33 dyads were identified at TH, and 47 dyads were identified at BH. Maternal baseline characteristics are included in Table I . The mean maternal age was 30.8 years, and 59 mothers (36.9%) were symptomatic during perinatal hospitalization, with fever (>37.7°C), cough, shortness of breath, or a combination of these. Twenty-five mothers (15.6%) had been symptomatic before the perinatal admission but were no longer symptomatic during hospitalization. A total of 149 mothers (93.1%) were characterized as being well for breastfeeding following delivery, whereas 11 (6.9%) were ill and unable to breastfeed. Overall, 148 deliveries (92.5%) were expected, and the remaining 12 were preterm deliveries owing to various indications; 120 infants (75%) were born via spontaneous vaginal delivery, 38 (23.7%) were born via cesarean delivery due to various indications, and 2 (1.3%) were born extramurally. A lactation consultation was initiated for 64 mothers (40%), of whom 38 received lactation consultation services during hospitalization. Only 1 mother had a contraindication for breastfeeding, due to maternal opioid dependence and neonatal abstinence syndrome.

Table I.

Maternal and infant characteristics (N = 160 unless specified)

| Characteristics | Value |

|---|---|

| Maternal | |

| Age, y, mean ± SD (median) | 30.8 ± 6.2 (31) |

| Gravida, mean ± SD (median) | 3.4 ± 2.5 (3) |

| Parity, mean ± SD (median) | 1.7 ± 1.9 (1) |

| Gestational age, mean ± SD (median) | 38.8 ± 1.7 (39.1) |

| Ethnicity, n (%) | |

| Non-Hispanic | 91 (56.9) |

| Hispanic | 65 (40.6) |

| Unknown | 4 (2.5) |

| Race, n (%) | |

| White | 84 (52.5) |

| Black | 13 (8.1) |

| Asian | 2 (1.3) |

| Native Hawaiian/other Pacific Islander | 9 (5.6) |

| Other | 52 (32.5) |

| Symptoms | |

| Never symptomatic, n (%) | 76 (47.5) |

| Symptomatic only during admission, n (%) | 21 (13.1) |

| Symptomatic before and during admission, n (%) | 38 (23.8) |

| Symptomatic only before admission, n (%) | 25 (15.6) |

| Day of symptoms,∗ mean ± SD (median) | −14.6 ± 17.1 (−7) |

| Fever (>100 °F), n (%) | 49 (30.6) |

| Cough, n (%) | 65 (40.6) |

| Shortness of breath, n (%) | 13 (8.1) |

| Maternal medications, n (%) | |

| None | 134 (89.4) |

| Hydroxychloroquine | 15 (9.4) |

| Azithromycin | 10 (6.3) |

| Tocilizumab | 3 (1.9) |

| Remdesivir | 2 (1.3) |

| Lopinavir-ritonavir | 3 (1.9) |

| Heparin | 5 (3.1) |

| Reason for delivery, n (%) | |

| Expected | 148 (92.5) |

| Preterm (infant indication) | 2 (1.3) |

| Preterm (maternal indication) | 6 (3.8) |

| Maternal COVID-19 | 4 (2.5) |

| Method of delivery | |

| Vaginal delivery | 120 (75.0) |

| Elective primary cesarean | 1 (0.6) |

| Repeat cesarean | 11 (6.9) |

| Cesarean for failed induction | 2 (1.3) |

| Cesarean for failure to progress | 4 (2.5) |

| Cesarean for Non Reassuring Fetal Heart Tracing | 7 (4.4) |

| Cesarean for breech | 3 (1.9) |

| Emergency Cesarean | 6 (3.8) |

| Cesarean for maternal indication (eg, preeclampsia, placenta previa) | 4 (2.5) |

| Extramural delivery | 2 (1.3) |

| Rupture of membranes, h, mean ± SD (median) (N = 159) | 5.5 ± 7.1 (2) |

| Infant characteristics | |

| Sex, n (%) | |

| Male | 71 (44.4) |

| Female | 89 (55.6) |

| Birth weight, kg, mean ± SD (median) | 3.3 ± 0.5 (3.28) |

| Length, cm, mean ± SD (median) | 0.51 ± 0.03 (0.51) |

| Head circumference, cm, mean ± SD (median) | 33.6 ± 1.6 (33.5) |

| Apagar 0 min, median (IQR) (N = 159) | 9 (8-9) |

| Apgar 5 min, median (IQR) (N = 159) | 9 (9-9) |

| SGA/AGA/LGA, n (%) | |

| SGA | 10 (6.3) |

| AGA | 143 (89.4) |

| LGA | 7 (4.4) |

| Need for resuscitation (PPV), n (%) | 15 (9.4) |

| Newborn nursery or NICU, N (%) | |

| Newborn nursery | 145 (90.6) |

| NICU | 15 (9.4) |

| Isolation type, n (%) | |

| No isolation | 7 (4.4) |

| Contact only | 1 (0.6) |

| Contact/airborne/eye protection | 88 (55.0) |

| Contact/droplet/eye protection | 64 (40.0) |

| First test age, h, mean ± SD (median) | 21.5 ± 7.8 (24) |

| Second test age, h, mean ± SD (median) (N = 90) | 50.3 ± 18.0 (48) |

| Maximum temperature during hospitalization, °C, mean ± SD (median) | 37.3 ± 0.3 (37.2) |

| Total LOS, d, mean ± SD (median) | 3.0 ± 7.1 (2) |

| NICU LOS, d, mean ± SD (median) (N = 18) | 13.4 ± 18.4 (4.5) |

SGA, small for gestational age; AGA, average for gestational age; LGA, large for gestational age; PPV, positive pressure ventilation.

Negative number represents days before delivery.

Neonatal baseline characteristics are presented in Table I. Fifteen neonates (9.4%) required resuscitation with positive-pressure ventilation, and 145 (90.6%) were admitted to the newborn nursery. Among the 15 symptomatic neonates, 4 had fever, 11 had respiratory distress, 4 had feeding intolerance, 1 had rhinorrhea, and 7 had hypothermia. At the time of this report, 1 neonate remained hospitalized in the NICU, and the others had all been discharged. For neonates admitted to the newborn nursery, the median LOS was 2 days (95% CI, 1 to 2 days), compared with 3 days (95% CI, 2 to 19 days) for those admitted to the NICU. Only 1 infant had a positive SARS-CoV-2 PCR test (on day of life 5, after a negative test at birth); the remainder had negative tests throughout. This infant was held by an unmasked symptomatic mother immediately after birth.

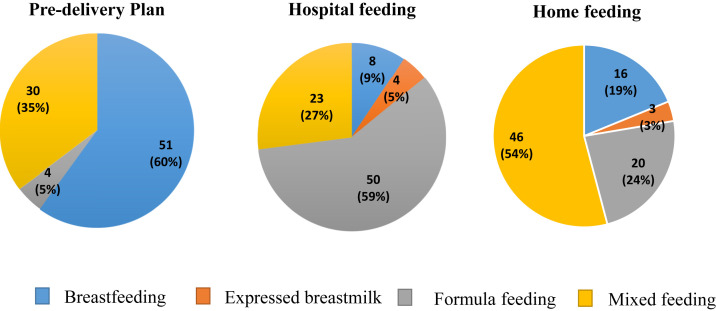

Telephone Survey

Telephone contact was made with 103 mothers (64.4%). Of these, 85 (82.5%) consented to participation in the telephone survey. The date of the telephone call ranged from a minimum of 10 days after birth to a maximum of 77 days after birth (median, 45 days). Survey responses are presented in the Figure . A total of 30 mothers (35.3%) indicated that COVID-19, and specifically the separation and subsequent difficulty with latching, was the reason for the change in feeding plan from predelivery to hospital or home. No change in feeding occurred from the predelivery plan to hospital or home feeding for 23 mothers (27.1%).

Figure.

Telephone survey results: maternal predelivery plan vs actual hospital and home feeding.

There was no statistically significant difference in predelivery feeding plan between the separated and unseparated dyads (P = .268) (Table II ). Hospital feeding type differed significantly for every single feeding type between the separated and unseparated dyads (P < .001), with higher rates of breastfeeding among unseparated dyads compared with separated dyads (22.2% vs 0%) and higher rates of formula feeding among separated dyads compared with unseparated dyads (81.6% vs 27.8%) (Table II). Only 2 mothers in each group reported using expressed breast milk as the sole feeding source during hospitalization (5.6% in the unseparated group vs 4.1% in the separated group). A higher percentage of mothers in the unseparated group reported a mix of feeding types, with a combination of breastfeeding, expressed breast milk, and formula, compared with the separated group (44.4% vs 14.3%). Home feeding type also differed significantly for each single feeding type between the separated and unseparated dyads (P = .012), again with higher rates of breastfeeding among unseparated dyads compared with separated dyads (27.8% vs 12.2%) and higher rates of formula feeding among separated dyads compared with unseparated dyads (34.7% vs 8.3%) (Table II). Again, the unseparated mothers reported higher rates of expressed breast milk (5.6% vs 2.0%), as well as higher rates of mixed feeding (58.3% vs 51.0%). The reason for the change in feeding type from the predelivery plan to hospital and/or home feeding type differed significantly between the 2 groups (P < .001), with a higher percentage in the separated group reporting a change due to COVID-19 (49.0% vs 16.7%). There was no difference in the rate of lactation consultation between the separated and unseparated dyads (40.4% vs 40.6%; P < .98).

Table II.

Telephone survey responses by separation status

| Responses | Separated, n (%) | Not separated, n (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Predelivery plan (P = .268) | ||

| Breastfeeding | 28 (57.1) | 23 (63.9) |

| Formula feeding | 1 (2.0) | 3 (8.3) |

| Mixed feeding | 20 (40.8) | 10 (27.8) |

| Hospital feeding (P < .001) | ||

| Breastfeeding | 0 (0) | 8 (22.2) |

| Expressed breast milk | 2 (4.1) | 2 (5.6) |

| Formula feeding | 40 (81.6) | 10 (27.8) |

| Mixed feeding | 7 (14.3) | 16 (44.4) |

| Home feeding (P = .012) | ||

| Breastfeeding | 6 (12.2) | 10 (27.8) |

| Expressed breast milk | 1 (2.0) | 2 (5.6) |

| Formula feeding | 17 (34.7) | 3 (8.3) |

| Mixed feeding | 25 (51.0) | 21 (58.3) |

| Reason plan changed (P < .001) | ||

| Plan did not change | 6 (12.2) | 17 (47.2) |

| Due to COVID-19 (including separation and subsequent difficulty with latching) | 24 (49.0) | 6 (16.7) |

| Other | 4 (8.2) | 10 (27.8) |

| No response | 15 (30.6) | 3 (8.3) |

When the separated and unseparated dyad groups were further stratified into 4 groups by symptom status—asymptomatic separated, asymptomatic unseparated, symptomatic separated, and symptomatic unseparated—the results remained unchanged. No statistically significant differences in the predelivery feeding plan were observed among the 4 groups (P = .698) (Table III ). Hospital feeding type differed significantly for each single feeding type among all 4 groups of dyads (P < .001), with the highest rate of breastfeeding in the asymptomatic unseparated group (22.6%), and the highest rate of formula feeding in the symptomatic separated group (83.3%) (Table III). Home feeding type also differed significantly for every single feeding type among all 4 groups of dyads (P = .018), with the highest rate of breastfeeding in the asymptomatic unseparated group (22.6%) and the highest rate of formula feeding in the asymptomatic separated group (36.8%) (Table III). The highest rate of mixed feeding was observed in the asymptomatic unseparated group, both during hospitalization (45.2%) and at home (64.5%). The reason for the change in feeding type from the predelivery plan to hospital and/or home feeding type differed significantly among the 4 groups (P < .001). A higher percentage reported a change due to COVID-19 in the asymptomatic separated group (57.9%) and the symptomatic separated group (43.3%) compared with both the asymptomatic unseparated group (16.1%) and the symptomatic unseparated group (20.0%).

Table III.

Telephone survey responses by separation and symptom status

| Responses | Asymptomatic separated, n (%) | Asymptomatic not separated, n (%) | Symptomatic separated, n (%) | Symptomatic not separated, n (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Predelivery plan (P = .698) | ||||

| Breastfeeding | 10 (52.6) | 19 (61.3%) | 18 (60.0%) | 4 (80.0%) |

| Formula feeding | 0 (0) | 3 (9.7%) | 1 (3.3%) | 0 (0%) |

| Mixed feeding | 9 (47.4) | 9 (29.0%) | 11 (36.7%) | 1 (20.0%) |

| Hospital feeding (P < .001) | ||||

| Breastfeeding | 0 (0) | 7 (22.6) | 0 (0) | 1 (20.0) |

| Expressed breast milk | 0 (0) | 1 (3.2) | 2 (6.7) | 1 (20.0) |

| Formula feeding | 15 (78.9) | 9 (29.0) | 25 (83.3) | 1 (20.0) |

| Mixed feeding | 4 (21.1) | 14 (45.2) | 3 (10.0) | 2 (40.0) |

| Home feeding (P = .018) | ||||

| Breastfeeding | 1 (5.3) | 7 (22.6) | 5 (16.7) | 3 (60.0) |

| Expressed breast milk | 0 (0) | 1 (3.2) | 1 (3.3) | 1 (20.0) |

| Formula feeding | 7 (36.8) | 3 (9.7) | 10 (33.3) | 0 (0) |

| Mixed feeding | 11 (57.9) | 20 (64.5) | 14 (46.7) | 1 (20.0) |

| Reason plan changed (P < .001) | ||||

| Plan did not change | 3 (15.8) | 16 (51.6) | 3 (10.0) | 1 (20.0) |

| COVID-19∗ | 11 (57.9) | 5 (16.1) | 13 (43.3) | 1 (20.0) |

| Other | 3 (15.8) | 9 (29.0) | 1 (3.3) | 1 (20.0) |

| No response | 2 (10.5) | 1 (3.2) | 13 (43.3) | 2 (40.0) |

Including separation and subsequent difficulty with latching.

Discussion

In this study, we found that SARS-CoV-2 infection has a significant impact on mother–newborn dyads with respect to breastfeeding outcomes both in the hospital setting and at home. We found a statistically significant lower rate of breastfeeding among separated dyads compared with unseparated dyads. Importantly, we found no clinical evidence of vertical or horizontal transmission from asymptomatic mothers to their infants. One case of likely postnatal transmission occurred from a symptomatic mother to her neonate; the infant was found to be SARS-CoV-2 PCR-positive on a nasopharyngeal swab performed on day of life 5, after testing negative at birth.

Early published data during the COVID-19 pandemic highlighted variable disease severity and outcomes for neonates and underscored a lack of clear evidence or understanding of transmission surrounding spread from infected mothers to their infants, through either vertical or horizontal transmission. A case series of 9 pregnant women with confirmed COVID-19 during the third trimester of pregnancy in China suggested that in utero, vertical transmission of SARS-CoV-2 to neonates did not occur, because samples of amniotic fluid, cord blood, and neonatal throat swabs tested at birth for SARS-CoV-2 were all negative.12 Similarly, a case series of 10 neonates (including one set of twins) born to nine mothers in China reported negative SARS-CoV-2 nucleic acid testing performed on pharyngeal swabs for all 10 neonates.13 In a cohort study in China, of 33 infants born to mothers with COVID-19, 3 were found to have early-onset infection with SARS-CoV-2, with positive nasopharyngeal and anal swabs on days of life 2 and 4.14 The authors suggested that in light of the strict infection control measures in place during these deliveries, vertical transmission could not be ruled out as the source of the neonates' SARS-CoV-2 infection.14 Importantly, these infants were not tested before day of life 2, and the infection control measures in place were not described, raising the possibility of horizontal rather than vertical transmission. Another case report, from Iran, described a 15-day-old neonate who came to attention with fever and lethargy after his mother exhibited symptoms consistent with COVID-19; the infant tested positive for SARS-CoV-2 by reverse-transcriptase PCR testing, suggesting possible horizontal transmission.15

During a tumultuous period with rapid spread of SARS-CoV-2 and inconclusive evidence to guide evolving practices surrounding childbirth and postpartum neonatal care, our institution implemented guidelines supporting separation of mother–newborn dyads, with the goal of limiting exposure and infection of neonates. Our guidelines mirror those of the CDC and AAP, and no distinction was made between symptomatic and asymptomatic mothers; separation at birth was recommended for all infants born to mothers with positive SARS-CoV-2 PCR regardless of symptoms.4 , 5

As time progressed through the pandemic, NYULH frequently reviewed and revised our policies to address the needs of our patients and reflect the most up-to-date knowledge and evidence surrounding COVID-19. It became evident that separation of mother–newborn dyads was particularly stressful for many mothers and their newborns and that the impact of separation on breastfeeding could be harmful.16 With a continued lack of evidence suggesting substantial transmission of SARS-CoV-2 via breast milk, our policy was modified on April 20, 2020, to allow asymptomatic mother who were SARS-CoV-2 PCR-positive to room-in with their infants. Furthermore, our new policy allowed asymptomatic mothers to breastfeed while wearing masks and using strict hand hygiene. This change echoed the WHO guidance supporting direct breastfeeding, but unlike the WHO guidelines, which recommend direct breastfeeding also for symptomatic mothers, our new guidelines limit contact between symptomatic mothers and their newborns and continue to support expression of breast milk and bottle feeding by designated caregivers.6

At the time of this report, several centers around the world have published their experiences and recommendations surrounding management of SARS-CoV-2–positive mother–newborn dyads during the pandemic.17, 18, 19 Data on the impact of separation of infected mother–newborn dyads on breastfeeding outcomes has been lacking, however. In a commentary outlining the key literature opposing separation of mother–newborn dyads, the authors highlighted the absence of evidence demonstrating a negative effect of separation during the COVID-19 pandemic.20 The AAP Section on Neonatal-Perinatal Medicine is currently collecting data on mothers who are SARS-CoV-2–positive and their infants in a national registry, with the goal of studying transmission of the virus and outcomes of these neonates and analyzing the impact of infection control policies, including dyad separation.

Our study provides evidence that in the setting of the COVID-19 pandemic, separation of asymptomatic mother–newborn dyads has a significant negative impact on breastfeeding outcomes. Our findings suggest that separation of mother–newborn dyads results in lower rates of breastfeeding both during hospitalization and at home following discharge, and in higher rates of formula feeding as a substitute. Higher rates of mixed feeding type (breastfeeding, expressed breast milk, and formula) were observed in the unseparated dyads compared with the separated dyads, suggesting that even when formula supplementation is used, rooming-in is associated with higher rates of being fed any breast milk, which persisted beyond hospitalization. Many mothers reported that once reunited with their infants after separation, attempts at breastfeeding were frequently unsuccessful due to difficulty with latching and the infant's preference for bottle-feeding.

Although a significant between-group difference was observed in the percentage of mothers reporting expressed breast milk as the sole feeding type during hospitalization (4.1% of unseparated mothers vs 5.6% of separated mothers), the total number of mothers using expressed breast milk as the feeding type was small. When considering the rates of mixed feeding, the overall rates of expressed breast milk were likely higher, as 14.3% of separated mothers and 44.4% of unseparated mothers reported a mix of feeding types (breastfeeding, expressed breast milk, and formula) during hospitalization. Nevertheless, when the rate of mixed feeding for each group is compared with the same group's rate of formula feeding (81.6% of separated mothers and 27.8% of unseparated mothers), it becomes evident that separated dyads had lower rates of breast milk expression irrespective of formula supplementation. Promotion of breast milk expression for mothers separated from their infants due to COVID-19 is emphasized as a goal in all the published guidelines, and our failure to do so highlights an opportunity for intervention and improvement in our support of mothers with COVID-19. Although there was no significant difference in the rate of lactation consultation utilization between the separated and unseparated dyads (40.4% vs 40.6%), perhaps this illuminates a potential opportunity for increased provision of lactation services to separated dyads in the future.

Notably, only 1 infant in our cohort tested positive for SARS-CoV-2 during hospitalization. The infant's initial nasopharyngeal swab at birth was negative for SARS-CoV-2 but became positive on a repeat swab test on day of life 5. Fifteen neonates in our study exhibited symptoms of fever, respiratory distress, feeding intolerance, rhinorrhea, hypothermia, or a combination of these. Although the 1 infant who tested positive on day of life 5 experienced fever, considered attributable to neonatal abstinence syndrome, the infant was otherwise asymptomatic with regard to COVID-19. In the remaining 14 neonates, symptoms were largely attributed to prematurity or environmental causes. We did not assess the impact of neonates symptoms or the impact of NICU admission on breastfeeding outcomes, and suggest that these may be the focus of future studies.

Although our local revised guidelines support rooming-in only for asymptomatic dyads, some symptomatic mothers still favor rooming-in after education about the risks of transmission. The sample size for this group of symptomatic unseparated dyads was small (n = 5), but when the separated and unseparated groups were further stratified to account for symptom status, our findings still demonstrate significant differences in feeding type both in the hospital and at home, with higher rates of breastfeeding in the unseparated dyads and higher rates of formula feeding in the separated dyads. The risks of transmission always must be weighed against the impact on breastfeeding as a result of separation. In keeping with the CDC recommendations highlighting the risk of transmission through respiratory droplets from symptomatic mothers, we continue to separate dyads in cases where the mother is symptomatic with cough.21

Several limitations of this study should be noted. First, variation exists with regard to demographic characteristics of the 3 hospitals included, notably in the different baseline rates of exclusive breastfeeding. In addition, early on, maternal testing protocols varied among the 3 sites. At WH, universal screening of all delivering mothers was instituted early, with a focus on cohorting mothers for rooming purposes based on test results, owing to a limited number of single-occupancy rooms in the mother–baby unit. Both TH and BH initially tested only symptomatic mothers, but both subsequently initiated universal screening protocols. We addressed these variations by pooling data from the 3 sites together.

The last infant respiratory sample for SARS-CoV-2 PCR testing was obtained at a mean of 50 hours and likely would not reflect horizontal transmission. Further data were restricted to maternal questioning at the time of phone survey. Our relatively small sample size does not exclude low rates of infant acquisition of SARS-CoV-2 illness.

Data Statement

Data sharing statement available at www.jpeds.com.

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Supplementary Data

References

- 1.World Health Organization WHO Director General’s opening remarks at the media briefing on COVID-19, 11 March 2020. https://www.who.int/dg/speeches/detail/who-director-general-s-opening-remarks-at-the-media-briefing-on-covid-19---11-march-2020 Accessed June 10 2020.

- 2.New York State Department of Health New York State statewide COVID-19 testing dataset. https://health.data.ny.gov/Health/New-York-State-Statewide-COVID-19-Testing/xdss-u53e

- 3.New York State Department of Health NYSDOH COVID-19 Tracker. https://covid19tracker.health.ny.gov/views/NYS-COVID19-Tracker/NYSDOHCOVID-19Tracker-Map?%3Aembed=yes&%3Atoolbar=no&%3Atabs=n

- 4.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Interim considerations for infection prevention and control of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) in inpatient obstetric healthcare settings. https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/hcp/inpatient-obstetric-healthcare-guidance.html Accessed June 11 2020.

- 5.Puopolo K., Hudak M.L., Kimberlin D.W., Cummings J. American Academy of Pediatrics Committee on Fetus and Newborn, Section on Neonatal Perinatal Medicine, and Committee on Infectious Diseases. Initial guidance: management of infants born to mothers with COVID-19. https://www.tn.gov/content/dam/tn/health/documents/cedep/novel-coronavirus/AAP_COVID-19-Initial-Newborn-Guidance.pdf Accessed June 10 2020.

- 6.World Health Organization Clinical management of severe acute respiratory infection (SARI) when COVID-19 disease is suspected: interim guidance, 13 March 2020. https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/331446 Accessed June 11 2020.

- 7.American Academy of Pediatrics Section on Breastfeeding Breastfeeding and the use of human milk. Accessed June 10 2020. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 8.Cohen S.S., Alexander D.D., Krebs N.F., Young B.E., Cabana M.D., Erdmann P. Factors associated with breastfeeding initiation and continuation: a meta-analysis. J Pediatr. 2018;203:190–196.e21. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2018.08.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.New York State Department of Health Hospital maternity-related procedures and practices statistics. https://www.health.ny.gov/statistics/facilities/hospital/maternity/

- 10.Lee E.T. 2nd ed. Wiley; New York (NY): 1992. Statistical methods for survival data analysis. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Greenwood M. vol 33. Her Majesty’s Stationery Office; London: 1926. The errors of sampling of the survivorship table. (Reports on public health and medical subjects). [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chen H., Guo J., Wang C., Luo F., Yu X., Zhang W. Clinical characteristics and intrauterine vertical transmission potential of COVID-19 infection in nine pregnant women: a retrospective review of medical records. Lancet. 2020;395:809–815. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30360-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zhu H., Wang L., Fang C., Peng S., Zhang L., Chang G. Clinical analysis of 10 neonates born to mothers with 2019-nCoV pneumonia. Transl Pediatr. 2020;9:51–60. doi: 10.21037/tp.2020.02.06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zeng L., Xia S., Yuan W., Yan K., Xiao F., Shao J. Neonatal early-onset infection with SARS-CoV-2 in 33 neonates born to mothers with COVID-19 in Wuhan, China. JAMA Pediatr. 2020;174:722–725. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2020.0878. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kamali Aghdam M., Jafari N., Eftekhari K. Novel coronavirus in a 15-day-old neonate with clinical signs of sepsis: a case report. Infect Dis (Lond) 2020;52:427–429. doi: 10.1080/23744235.2020.1747634. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Stuebe A. Should infants be separated from mothers with COVID-19? First, do no harm. Breastfeed Med. 2020;15:351–352. doi: 10.1089/bfm.2020.29153.ams. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Amatya S., Corr T.E., Gandhi C.K., Glass K.M., Kresch M.J., Mujsce D.J. Management of newborns exposed to mothers with confirmed or suspected COVID-19. J Perinatol. 2020;40:987–996. doi: 10.1038/s41372-020-0695-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Salvatori G., De Rose D.U., Concato C., Alario D., Olivini N., Dotta A. Managing COVID-19–positive maternal–infant dyads: an Italian experience. Breastfeed Med. 2020;15:347–348. doi: 10.1089/bfm.2020.0095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Giuliani C., Li Volsi P., Brun E., Chiambretti A., Giandalia A., Tonutti L. Breastfeeding during the COVID-19 pandemic: suggestions on behalf of woman study group of AMD. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2020;165:108239. doi: 10.1016/j.diabres.2020.108239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tomori C., Gribble K., Palmquist A.E.L., Ververs M., Gross M.S. When separation is not the answer: breastfeeding mothers and infants affected by COVID-19. Matern Child Nutr. 2020 doi: 10.1111/mcn.13033. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Evaluation and management considerations for neonates at risk for COVID-19. https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/hcp/caring-for-newborns.html Accessed June 11 2020.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.