Abstract

Play is considered the main occupation for children. Pediatric occupational therapists utilize play either for evaluation or intervention purpose. However, play is not properly measured by occupational therapists, and the use of play instrument is limited. This systematic review was aimed at identifying play instruments relevant to occupational therapy practice and its clinimetric properties. A systematic search was conducted on six databases (Academic Search Complete, CINAHL, MEDLINE, Psychology and Behavioral Science Collection, Scopus, and ASEAN Citation Index) in January 2020. The quality of the included studies was evaluated using Law and MacDermid's Appraisal for Clinical Measurement Research Reports, and psychometric properties of play instruments were evaluated using Terwee's checklist while the clinical utility is extracted from each instrument. Initial search identifies 1,098 articles, and only 30 articles were included in the final analysis, extracting 8 play instruments. These instruments were predominantly practiced in the Western culture, which consists of several psychometric evidences. The Revised Knox Preschool Play Scale is considered the most extensive and comprehensive play instrument for extrinsic aspect, whereas the Test of Playfulness + Test of Environmental Supportiveness Unifying Measure is a promising play instrument for intrinsic aspect on play, where both instruments utilize observation. My Child's Play is a potential questionnaire-based play instrument. However, the current development of play instruments in the occupational therapy field is immature and constantly evolving, and occupational therapists should exercise good clinical reasoning when selecting a play instrument to use in practice.

1. Introduction

Occupational therapy for children is found as one of the largest practice areas globally [1]. For children, play is the most important occupation that dominates their use of time. Play can be one of the therapeutic goals and can be used as a medium of intervention, which helps to improve an individual's functional performance [1–4]. Play was found to be beneficial for biological, physical, mental, and social development [5]. In general, play is a learning process that equips children with necessary physical, psychological, cognitive, and social skills to facilitate normal development for typical children [6]. Therefore, selecting the right play activities as a means or as an end is important to bring the optimal outcome of children.

Using standardized play assessment can facilitate practitioners in identifying appropriate play activities to be set either as a goal or as a medium of intervention. However, utilization of standardized occupational therapy play instrument even as a research outcome is limited either on occupational therapy intervention [7] or on play-based intervention [2, 3]. An overview of reviews found no study that systematically identifies and investigates standardized occupational therapy instruments on play [8]. Several review studies were found during the literature search but were not in a systematic format. Stagnitti [6] listed three instruments: Knox Preschool Play Scale (and all its variation), Test of Playfulness, and Play History; however, the study was not systematically searched to identify any other play-based instruments. Sturgess [9] suggested several play instruments; however, only Play History and Preschool Play Scale were identified as occupational therapy-based instruments. Two reviews [10, 11] investigated functional assessments for children, and both identified that only the McDonald Play Inventory was used as an instrument tool for play. The limitation of the two reviews was the searching was limited to one journal platform. The absence of comprehensive review study as a guideline will hamper occupational therapy practitioners to efficiently use an appropriate play instrument and to plan an appropriate intervention.

Psychology, speech therapy, physiotherapy, and special education are other disciplines that have interest on play other than occupational therapy. Several instruments were developed by other professions, and several reviews investigated the psychometric properties of these instruments [12–14]. However, each discipline observed each aspect differently. Occupational therapy evaluates play itself, while other professions utilized play activity as a medium to evaluate a particular component [15]. For example, psychologists observe play to specifically evaluate the cognitive function and determine cognitive or social capacity [13, 14], and physiotherapists observe play to evaluate the physical capacity of children [12]. In addition, the only instrument-focused systematic review [12] investigated play-based assessment and not play assessment. Play-based assessment utilizes play activity but evaluates nonplay aspects, such as motor or cognitive functions, whereas play assessment evaluates play for the sake of play.

A study found that occupational therapists used various types of assessments to evaluate play, but some are not purported for play [16]. For example, majority of occupational therapists used Vineland Adaptive Behavior Scale and Battelle Developmental Inventory that evaluate adaptive behavior and general physical, cognitive, and social development in an intention to assess play. This may result in misled judgement on the intervention planning; there is evidence where play is used to elicit improvement in other areas, such as fine motor skills and cognitive function [16, 17]. Therefore, difference on the philosophical foundation of instruments may hinder occupational therapists to efficiently conduct the evaluation and interpret the findings effectively for the purpose of play.

Kuhaneck and colleagues [16] indicated a decreasing trend of using play instrument among occupational therapists. Several reasons were mentioned such as lack of knowledge on available play instruments and lack of continuing education on the existing play instruments. Lynch et al. [18] in their survey found a similar finding where occupational therapists considered play important but indicated lack of education either from research, theory, evaluation, or intervention that contributed to challenges in applying play-centered practice. Meanwhile, Wadley and Stagnitti [19] found that occupational therapists and teachers do appreciate the importance of play for children; however, parents' and family members' understanding on the therapeutic value of play is limited and does not consider play the main goal for the children's functional outcome. Using standardized assessment is part of evidence-based practice [20], enhances the confidence, and strengthens communication and message delivery [21] on the importance of play. Therefore, a systematic review should be conducted to gather play assessments relevant for use in occupational therapy practice to inform the practitioners on the available instruments, enhance evidence-based practice, and select the best instrument for efficient communication medium with clients.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Objective

This systematic review was registered on INPLASY (Registration Number: 202040156) and PROSPERO (CRD42020170370). The aim of this review is to identify and gather clinimetric evidence of play instruments developed by occupational therapists. Clinimetric refers to the evidence of psychometric properties (i.e., validity and reliability) and clinical utility of an instrument [22].

2.2. Study Identification

A systematic search was conducted on six electronic databases, namely, Academic Search Complete, CINAHL, MEDLINE, Psychology and Behavioral Science Collection, Scopus, and ASEAN Citation Index. Keywords were generated by discussion among authors and reviewing previous literatures. The following keywords were used: (“play” OR “play-based” OR “playthings”) AND (“evaluation” OR “assessment” OR “measurement” OR “battery” OR “test” OR “instrument”) AND (“validity” OR “reliability” OR “sensitivity” OR “precision” OR “specificity” OR “responsiveness” OR “psychometric”) with slight variation. Boolean operators, parenthesis, truncation, and wildcards were used whenever appropriate. For ASEAN Citation Index, only the word “play” was keyed in as the limited function of the search engine that does not allow for search string to be implemented. As the search number was overwhelming, restriction was imposed on keywords existent only in the title for play-related keywords. The search was conducted on 21 January 2020.

Manual search was conducted by screening the reference list of the included study. In addition, the identified instruments were searched for its original article. An innovative method using the “cited by” option in Google Scholar was performed on all original and included articles to allocate more potential articles [23]. Relevant citations were then selected, and the screening process was conducted for eligibility.

2.3. Eligibility Criteria

Each retrieved study was evaluated for its eligibility according to the following inclusion and exclusion criteria. The inclusion criteria were (i) study on the instrument for leisure type of play (not competitive play or sports), (ii) instrument generally evaluating play, (iii) study investigating the psychometric property of the instrument, (iv) the instrument used solely on play (not part of a multidimensional instrument), and (v) the instrument relevant for the use of occupational therapy. The last criteria were determined by scrutinizing the instruments found either developed or involved occupational therapist by reviewing the authors of the instrument's original study. Exclusion criteria were (i) not a primary study (i.e., review and editor note), (ii) no full text available, (iii) full text is not available in English, (iv) grey literature (e.g., thesis, book, and conference), and (v) nonpeer review journal article.

2.4. Study Selection

Duplicates were initially removed before the screening process. The first author screened the title for eligibility according to the predetermined criteria, followed by independent screening of the abstract and full text by both authors. The preconsensus agreement was calculated by comparing the final accepted articles between the two authors. Any disagreements were resolved through discussion between the two authors until consensus was achieved.

2.5. Data Extraction and Analysis

Included articles in the final analysis were narratively analyzed. Each article is extracted for study objective, study design, instrument investigated, number and characteristics of raters, number and characteristics of participants, country of the study, and findings on psychometric property. Extracted play instruments were then identified on its clinical utility focused on the application and administration aspects.

2.6. Quality Appraisal of the Study

Two quality assessment tools were used. The quality of each article is assessed using a quality appraisal evaluation form by Law and MacDermid [24]. Terwee's checklist [25] is used to evaluate the pool of psychometric evidence on each instrument found. Although the COnsensus-based Standards for the selection of health status Measurement Instruments (COSMIN; [26]) is considered the gold standard to evaluate the quality of the assessment tool instrument, however, it has several limitations to be used in this systematic review. First, the COSMIN was specifically developed to assess articles demonstrating patient-reported outcomes of health measurement instruments, which might not be suitable for some occupational therapy measurement tools such as play instruments that are complex, varied in terms of administration procedures, involved observation or proxy for rating, and comprised environmental and ecological elements [17, 27, 28]. Second, while the validity of the COSMIN is adequate [29], the reliability of the COSMIN through kappa analysis was poor [30]. Therefore, the use of Law and MacDermid's form and Terwee's checklists is better suited for this study.

Quality Appraisal for Clinical Measurement Research Reports Evaluation Form [24] is a 12-item checklist evaluating the quality of psychometric study on five domains that are research question, design, measurements, analyses, and recommendations. Each item on this form is assigned a score of 0–2 (2, best practice; 1, acceptable but suboptimal practice; and 0, substantially inadequate or inappropriate practice). Only item 6 can be denoted as N/A (not applicable) because it relates to the longitudinal type of study (i.e., test-retest). The total score is calculated by adding all scores from each item and then converted to a percentage. Higher score indicates better quality. The form was developed by rehabilitation experts from occupational therapy and physiotherapy backgrounds and has excellent interrater reliability [31–37] that has been used in environment-based instruments [28]. Quality assessments were administered by both authors and verified through discussion.

The Terwee checklist is an assessment tool to determine the quality of psychometric properties of the instrument [25]. For that purpose, studies were grouped based on the instrument described, and a summary of psychometric properties of each instrument was then prepared according to eight categories, namely, (i) content validity, (ii) internal consistency, (iii) criterion validity, (iv) construct validity, (v) reproducibility (agreement and reliability), (vi) responsiveness, (vii) floor or ceiling effect, and (viii) interpretability. Each instrument was then assessed against the quality criteria and rated according to four categories: positive (i.e., +), which means having a desired outcome with robust methodology; intermediate (i.e., ?), which means having a desired outcome with less robust methodology; poor (i.e., -), means having an undesired outcome or having poor methodology; and no information available (i.e., N/A). When two or more studies investigated the same property, the highest quality score for that item was recorded.

3. Results

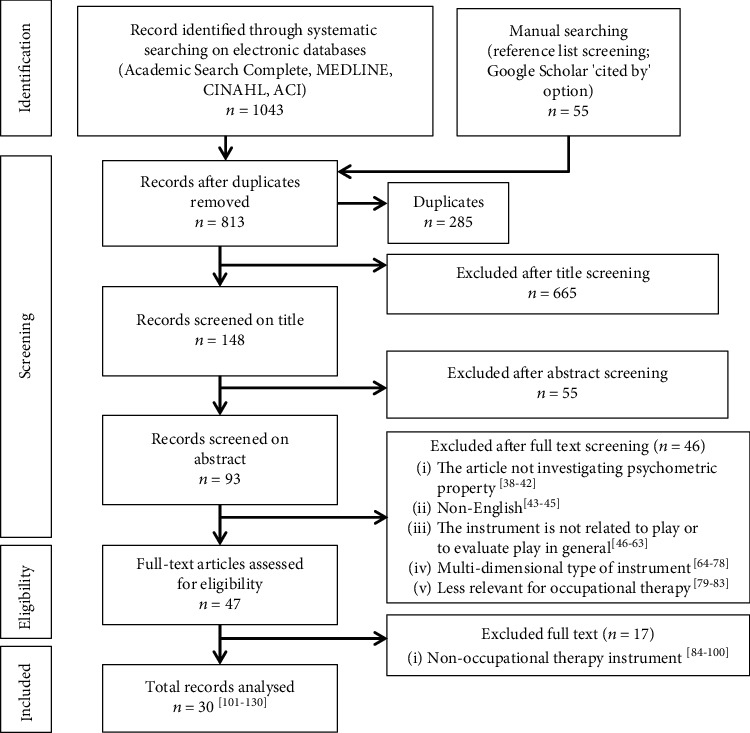

A total of 1,098 articles were retrieved; 1,043 were obtained from the electronic database search, and another 55 were later identified from the reference list of the included studies and list of relevant literature found using Google Scholar's “cited by” option. Ultimately, as shown in Figure 1, 63 [38–100] articles were excluded during the full-text screening and 30 [101–130] individual studies were selected after the screening process by the two authors (preconsensus agreement on accepted full text: 79.4%). The description of each included individual study and its psychometric report is presented in Table 1.

Figure 1.

Screening process.

Table 1.

Characteristic and psychometric reporting of individual studies.

| Author | Year | Instrument | Objective | Study design | Country | Participant | Rater | Finding |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dender & Stagnitti [108] | 2017 | IPPS | To explore the content and cultural validity for social aspect of the instrument | Qualitative | Australia | 6 pairs of indigenous children (i.e., 12 children) 14 community elders and mothers |

— | The extension instrument is culturally accepted and nonjudgmental. |

| Golchin et al. [109] | 2017 | ChIPPA | To establish the reliabilities, content, and cross-cultural validity of the translated Persian version of the instrument | Cross-sectional (validity) Cohort (reliabilities) |

Iran | 5 occupational therapists 31 typical children |

2 researchers | Internal consistency is α = 0.752. Reliability is excellent for intrarater (ICC = 0.99), interrater (ICC = 0.98) and moderate to strong for test-retest (ICC = 0.69–0.99). Content validity is strong (CVR = 0.81–1.00). |

| Stagnitti & Lewis [129] | 2015 | ChIPPA | To investigate the predictive validity of the instrument on semantic organization and narrative retelling skills using SAOLA | Cross-sectional | Australia | 48 typical and at risk of learning difficulty children | 3 examiners | The instruments predicted 23.8% of semantic organization and 18.2% of narrative retelling skills. |

| Dender & Stagnitti [107] | 2011 | I-ChIPPA | To investigate the cultural appropriateness of the adapted instrument and its reliability | Qualitative Cross-sectional |

Australia | 23 indigenous Australian children (i.e., 12 pairs) | 4 indigenous children | Cultural adaptation is satisfactory. The toys were found to be gender-neutral (p > 0.05). Overall, interrater reliability on toy use is moderate (ICC = −0.33–1.00). |

| Pfeifer et al. [120] | 2011 | ChIPPA | To establish the cross-cultural validity and reliability of the translated Portuguese version of the instrument | Cross-sectional | Brazil | 14 typical children | 1 occupational therapy student and 1 supervisor | Validity is established where the play material and duration are appropriate with the Brazilian context. Intrarater reliability is good (r = 0.90–0.97). Interrater reliability is moderate (r = 0.13–0.76). |

| McAloney & Stagnitti [117] | 2009 | ChIPPA | To investigate the concurrent validity of the instrument | Cross-sectional | Australia | 53 typical children | 1 researcher | Significant negative correlation was found between play and social. |

| Uren & Stagnitti [128] | 2009 | ChIPPA | To investigate the construct validity of the instrument | Cross-sectional | Australia | 41 children of typical or minor disabilities | 5 teachers | There is probable evidence on construct validity of the instrument Penn Interactive Peer Play Scale (PIPPS) and Leuven Involvement Scale for Young Children (LIS-YC) where several components were significantly moderately correlated. |

| Swindells & Stagnitti [127] | 2006 | ChIPPA | To investigate the construct validity of the instrument | Cross-sectional | Australia | 35 typical children | 2 researchers | Interrater reliability is strong (k = 0.7). There is probable evidence on construct validity of the instrument with Vineland Social-Emotional Early Childhood Scales; overall not significant but certain aspects were found significantly correlated. |

| Stagnitti & Unsworth [124] | 2004 | ChIPPA | To establish test-retest reliability of the instrument | Longitudinal | Australia | 38 typical and developmental delay children | 1 researcher | Test-retest reliability is moderate to strong (ICC = 0.57–0.85). |

| Stagnitti et al. [125] | 2000 | ChIPPA | To ascertain the discriminant validity and interrater reliability of the instrument | Cross-sectional | Australia | 82 typical and preacademic problem children | 3 occupational therapists | Interrater reliability is excellent (k = 0.96–1.00). Discriminant validity is established (p < 0.001) |

| Sposito et al. [123] | 2019 | Knox PPS | To verify the reliabilities of the Brazilian version of the instrument | Cross-sectional | Brazil | 135 typical children | 2 undergraduate occupational therapy students | Overall, the internal consistency is good (α = 0.48–0.95). Overall intrarater reliability (k = 0.18–0.99) is reported to be moderate to excellent and interrater reliability (k = −0.03–0.71) is moderate. |

| Pacciulio et al. [119] | 2010 | Knox PPS | To investigate the reliability and repeatability of the Brazilian version | Cohort | Brazil | 18 typical children | 2 examiners (one is the researcher; no further detail) | Strong intrarater correlation between the two occasions (r = 0.87–1.00). Strong interrater correlation between the two examiners (r = 0.78–0.99). |

| Lee & Hinojosa [116] | 2010 | Knox PPS | To establish the interrater and concurrent validity of the revised version of the instrument | Cross-sectional | United States of America | 61 children with autism | 2 researchers | Interrater reliability is excellent (ICC = 0.94) and construct validity with VABS is moderate (r = 0.52, p < 0.01). |

| Jankovich et al. [112] | 2008 | Knox PPS | To establish the interrater and construct validity of the revised version of the instrument | Cross-sectional | United States of America | 38 typically developing children | 2 occupational therapy students | Interrater agreement is high (81.8%–100%). Higher agreement was achieved on observation of older than younger children. Construct validity showed higher agreement between chronological and average play age for older than younger children. |

| Harrison & Keilhofner [111] | 1986 | Knox PPS | To determine the interrater and test-retest reliability and validity of the original instrument | Cross-sectional (interrater; concurrent validity) Longitudinal (test-retest) |

United States of America | 60 disabled preschool children | 3 observers (detail not mentioned) | Overall interrater reliability is substantial (ICC ≈ 0.67). Overall test-retest correlation is strong (r = 0.55–0.97). Concurrent validity indicates that the instrument correlates moderately with Parten's Social Play Hierarchy (kTau = 0.60–0.64) and Lunzer's Scale on Organization of Play Behavior (kTau = 0.50–0.89). The instrument correlated moderately with age (r = 0.01–0.91) for disabled children but strongly with typical children. |

| Bledsoe & Sheperd [102] | 1982 | Knox PPS | To determine the inter-rater, test-retest reliability and validity of the revised instrument | Cross-sectional (inter-rater; concurrent validity) Longitudinal (test-retest) |

United States of America | 90 typical children | 2 researchers cum observers | Overall, the inter-rater and test-retest yielded satisfactory correlation. Concurrent validity indicates that the instrument correlates moderately with Parten's Social Play Hierarchy and Lunzer's Scale on Organization of Play Behavior. The construct validity indicates that the instrument is correlated strongly with age. |

| McDonald & Vigen [118] | 2012 | McDonald Play Inventory | To examine the content, construct and discriminative, validity, internal consistency, and test-retest reliability of the instrument | Cross-sectional (validities, internal consistency) Longitudinal (test-retest) |

United States of America | 124 children 17 parents |

Self/proxy-rating 7 children (test-retest) |

Content validity is overall moderately correlated between items. Construct validity found that the instrument can discriminate between typical and disabled children. Concurrent validity between parent-child rating has low to moderate correlation (r = 0.04–0.49). Test-retest was strongly correlated (r = 0.69–0.82) between two time points. Internal consistency: α = 0.79–0.84. |

| Schneider & Rosenblum [122] | 2014 | My Child's Play | To describes the development, reliability, and validity of the instrument | Cross-sectional | Israel | 334 mothers | — | Concurrent validity with Parent as a Teacher Inventory is fair (r = 0.33; p < 0.001). Factor analysis established construct validity (αs = 0.63–0.81). Gender (girls>boys) and age were significantly different in score. Internal consistency: α = 0.86. |

| Lautamo & Heikkilä [113] | 2011 | PAGS | To investigate the interrater reliability of the instrument | Cross-sectional | Finland | 78 typical and atypical children | 12 professionals (teachers, occupational therapist, physiotherapist) | MFR on expected agreement (44.1%) and the observed agreement (50.8%) with Rasch kappa of 0.12. |

| Lautamo et al. [115] | 2011 | PAGS | To evaluate the validity of the instrument for use with children with language impairment over typical children | Cross-sectional | Finland | 156 typical and language impairment children | Proxy-rating (teachers, special education teachers, nurses, physiotherapist, occupational therapist) | The analysis found significant difference between the two groups, but 80% of the items are considered stable. |

| Lautamo et al. [114] | 2005 | PAGS | To determine the construct validity of the instrument | Cross-sectional | Finland | 93 typical and atypical children | Proxy-rating (teachers, special education teachers, nurses, occupational therapist) | The construct validity of the instrument is established by internal scale validity, and person response validity achieved strong goodness of fit value. |

| Behnke & Fetkovich [101] | 1984 | Play History Interview | To determine reliability in terms of interrater and test-retest and validity of the Play History Interview | Cross-sectional (interrater; concurrent validity) Longitudinal (test-retest) |

United States of America | 30 parents with nondisabled or disabled children | 2 researchers cum raters | Concurrent validity with Minnesota Child Development Inventory is overall moderate to strong. Known-group validity is able to discriminate between disabled and nondisabled children (p < 0.01). Interrater reliability is moderate to strong while test-retest has fair to strong correlation. |

| Sturgess & Ziviani [126] | 1995 | Playform | To explore the consistency on rating the instrument between three groups of rater | Cross-sectional | Australia | 13 children 13 parents 1 teacher |

— | Qualitatively, the rating between the three groups is relatively similar; parents scored slightly more positive than the children, but teachers are the most positive. |

| Bundy et al. [106] | 2009 | T-TUM | To investigate the translatability of the instrument to practice known as T-TUM (ToP+TOES Unifying Measure) | Cross-sectional | United States of America | 265 atypical children | — | At least 92% of the outcomes were within the limit for goodness of fit. The reliability enhanced to α = 0.96 for T-TUM. |

| Brentnall et al. [103] | 2008 | ToP | To evaluate the validity of instrument rating over different lengths and point of time | Cross-sectional | United States of America | 20 typical children | 3 researchers cum raters | Different time points have no significantly different observation outcome (p = 0.204) but significantly different than longer observation time (p < 0.001) but provide no added information. Longer observation time has poorer test-retest value (ICC = 0.033) compared to shorter time (ICC = 0.408–0.668). |

| Rigby & Gaik [121] | 2007 | ToP | To investigate the stability of the instruments over three different settings | Cohort | United States of America | 16 children with cerebral palsy | 1 researcher | The score showed significant difference across the three settings (i.e., home, community, and school) (p < 0.05). The children are most playful at home and least playful at school. |

| Hamm [110] | 2006 | ToP + TOES | To examine the validity and reliability of the instruments with children with and without disabilities | Cross-sectional | United States of America | 40 children with and without disabilities | 2 trained raters | Interrater agreement is 100%. Item response validity is 100%, and internal scale validity is 100%. There is less playfulness but higher correlation of the instrument with children with disabilities than without disabilities. |

| Bronson & Bundy [104] | 2001 | ToP + TOES | To evaluate the validity of the two instruments | Cross-sectional | United States of America | 160 children with and without disabilities | 10 raters (not specified) | The reliability is acceptable: α = 0.77. TOES construct validity is acceptable (94% fit). The environment (i.e., TOES) is correlated significantly with playfulness (i.e., ToP) (r = 0.401; p = 0.01). The TOES has significant difference between typical and disabled children (z = 2.96; p = 0.05). |

| Bundy et al. [105] | 2001 | ToP | To investigate the construct and concurrent validity and interrater reliability of the instrument | Cross-sectional | United States of America | 124 children (typical and special education) in total | 26 occupational therapists | Construct validity explained 93% of the items unidimensional construct on playfulness. Concurrent validity with Children's Playfulness Scale was found to be moderate (r = 0.46; p < 0.001). Interrater reliability achieved 96% consensus. |

| Okimoto et al. [130] | 1999 | ToP | To investigate the reliability and validity of the instrument | Cross-sectional | United States of America | 54 videotaped mother-CP-child dyad | 3 occupational therapists | The reliability is 97.5% fit within the acceptable range. The instrument was found to be sensitive to change. |

ChIPPA: Child-Initiated Pretend Play Assessment; I-ChIPPA: Indigenous ChIPPA; IPPS: Indigenous Play Partner Scale; Knox PPS: Revised Knox Preschool Play Scale; PAGS: Play Assessment for Group Setting; ToP: Test of Playfulness; TOES: Test of Environmental Supportiveness; T-TUM: ToP-TOES Unifying Measure.

Quality of individual studies was measured using Law and MacDermid's Quality Appraisal Tool, and the result is presented in Table 2. Overall, studies have the median score quality of 65.5% (range, 45–86%).

Table 2.

Quality assessment on each included study using Law and MacDermid [24] tool.

| Studies | Instrument◊ | Evaluation criteria† (score: 2 = good, 1 = moderate, 0 = poor, N/A = not applicable) | Total score (%) | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Item 1 | Item 2 | Item 3 | Item 4 | Item 5 | Item 6 | Item 7 | Item 8 | Item 9 | Item 10 | Item 11 | Item 12 | |||

| Dender & Stagnitti [108] | IPPS | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 1 | N/A | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 82 |

| Golchin et al. [109] | ChIPPA | 2 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 79 |

| Stagnitti et al. [125] | ChIPPA | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 0 | N/A | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 77 |

| Stagnitti & Lewis [129] | ChIPPA | 2 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 0 | N/A | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 1 | 68 |

| Uren & Stagnitti [128] | ChIPPA | 2 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 0 | N/A | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 1 | 64 |

| Swindells & Stagnitti [127] | ChIPPA | 2 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | N/A | 2 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 64 |

| Stagnitti & Unsworth [124] | ChIPPA | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 63 |

| Dender & Stagnitti [107] | I-ChIPPA | 1 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 0 | N/A | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 59 |

| Pfeifer et al. [120] | ChIPPA | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | N/A | 2 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 2 | 59 |

| McAloney & Stagnitti [117] | ChIPPA | 1 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 0 | N/A | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 59 |

| Sposito et al. [123] | Knox PPS | 2 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 2 | N/A | 2 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 73 |

| Jankovich et al. [112] | Knox PPS | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 0 | N/A | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 2 | 73 |

| Lee & Hinojosa [116] | Knox PPS | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 0 | N/A | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 64 |

| Bledsoe & Sheperd [102] | Knox PPS | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 63 |

| Harrison & Keilhofner [111] | Knox PPS | 1 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 54 |

| Pacciulio et al. [119] | Knox PPS | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | N/A | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 45 |

| McDonald & Vigen [118] | McDonald Play Inventory | 2 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 63 |

| Schneider & Rosenblum [120] | My Child's play | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 | N/A | 2 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 64 |

| Lautamo et al. [115] | PAGS | 2 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 1 | N/A | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 86 |

| Lautamo & Heikkilä [113] | PAGS | 2 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 1 | N/A | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 77 |

| Lautamo et al. [114] | PAGS | 2 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 1 | N/A | 2 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 77 |

| Behnke & Fetkovich [101] | Play history interview | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 2 | 67 |

| Sturgess & Ziviani [126] | Playform | 2 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 0 | N/A | 1 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 45 |

| Bundy et al. [106] | T-TUM | 1 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 1 | N/A | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 82 |

| Bronson & Bundy [104] | ToP + TOES | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1 | N/A | 2 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 82 |

| Hamm [110] | ToP + TOES | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 0 | N/A | 2 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 77 |

| Bundy et al. [105] | ToP | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1 | N/A | 2 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 2 | 77 |

| Brentnall et al. [103] | ToP | 2 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 75 |

| Rigby & Gaik [121] | ToP | 2 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 0 | N/A | 2 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 59 |

| Okimoto et al. [130] | ToP | 2 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 0 | N/A | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 50 |

†Item 1: relevant background on psychometric properties and research question; item 2: inclusion/exclusion criteria; item 3: specific psychometric hypothesis; item 4: appropriate scope of psychometric properties; item 5: appropriate sample size; item 6: appropriate retention/follow-up; item 7: specific descriptions of the measures (administration, scoring, interpretation procedures); item 8: standardization of methods; item 9: data presented for each hypothesis or purpose; item 10: appropriate statistical tests; item 11: appropriate secondary analyses; and item 12: conclusions/clinical recommendations supported by analyses and results. ◊ChIPPA: Child-Initiated Pretend Play Assessment; I-ChIPPA: Indigenous ChIPPA; IPPS: Indigenous Play Partner Scale; Knox PPS: Revised Knox Preschool Play Scale; PAGS: Play Assessment for Group Setting; ToP: Test of Playfulness; TOES: Test of Environmental Supportiveness; T-TUM: ToP-TOES Unifying Measure.

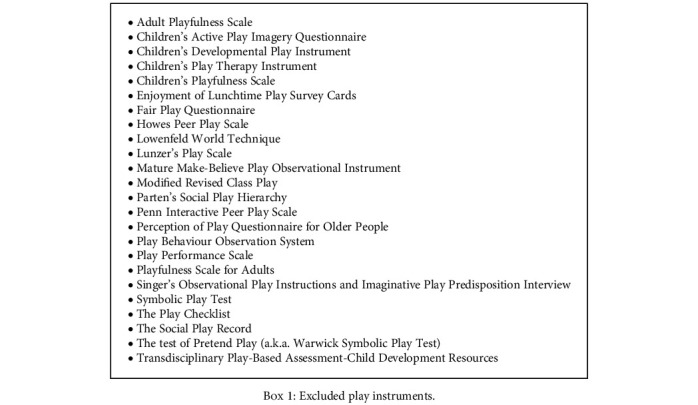

Eight original occupational therapy play instruments were extracted from the 30 included articles. The included instruments are (i) Child-Initiated Pretend Play Assessment (ChIPPA; including Indigenous Play Partner Scale), (ii) Revised Knox Preschool Play Scale (Knox PPS), (iii) McDonald's Play Inventory (MDPI), (iv) My Child's Play (MCP), (v) Play Assessment for Group Setting (PAGS), (vi) Playform, and (vii) Play History Interview (PHI) and Test of Playfulness (ToP, including Test of Environmental Supportiveness (TOES) and ToP-TOES Unifying Measure (T-TUM)). One occupational therapy instrument—Play Skills Inventory [38]—was found but was not included as there is no published journal article that investigated its psychometric property. Some of the instruments were published only once (i.e., McDonald's Play Inventory, My Child's Play, Playform, Play History Interview, and Play Assessment for Group Setting), whereas some were reported in several articles in different occasions (i.e., Knox PPS, ToP+TOES, and I-ChIPPA). Further analysis on the excluded full text articles was also conducted to identify available play instruments and listed in Box 1. However, those instruments are presented for information purpose and not to be included for analysis as they are nonoccupational therapy play instruments.

Box 1.

Excluded play instruments.

Instruments found usually investigated for concurrent and construct validity and interrater and test-retest reliability. Some instruments such as Knox PPS have been investigated on the same psychometric properties (e.g., interrater reliability and concurrent validity) over time. Homogeneity on the study location was identified where majority of the instruments have been investigated at the origin country. Most of the origin countries are Caucasian-dominant countries that are heavily influenced by the Western culture. The summary on psychometric evidences of each instrument extracted from individual studies is presented in Table 3.

Table 3.

Summary of the quality of psychometric properties of the instruments.

| Instrument tool | Terwee checklist [25] (score: + = positive; ? = intermediate; – = poor; 0 = no information available) | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Content validity | Internal consistency | Criterion validity | Construct validity | Reproducibility | Responsiveness | Floor or ceiling effect | Interpretability | ||

| Agreement | Reliability | ||||||||

| ChIPPA | +a, +b, +c | ?b | 0 | ? | ?, ?b | ?, ?a, ?b | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Knox's PPS | ? | ?d | 0 | ? | ? | +, ?d | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| McDonald Play Inventory | 0 | ? | 0 | — | 0 | ? | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| My Child's Play | + | + | 0 | + | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| PAGS | + | 0 | 0 | + | 0 | + | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Play History Interview | ? | 0 | 0 | ? | ? | ? | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Playform | + | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| ToP + TOES, T-TUM | +e, +f, +g | +f, +g | 0 | +e, +f, +g | ?e, ?f | ?e, ?f | 0 | 0 | ?f, +g |

aBrazilian-Portuguese ChIPPA; bIranian ChIPPA; cIndigenous Play Partner Scale (I-PPS); dKnox's Play Scale; eTest of Playfulness (ToP); fTest of Environmental Supportiveness (TOES); gToP-TOES Unifying Measure (T-TUM).

Several instruments are observation-based (i.e., ChIPPA, ToP, Knox's PPS, and Play Assessment for Group Settings) and evaluated by observing the children in play activities either in real situations or recorded videos, while some are perception-based by rating a questionnaire (i.e., McDonald's Play Inventory, My Child's Play, and Playform), and another is subjective-based instrument that retrieves information from a qualitative interview (i.e., Play History Interview). Most instruments focused on extrinsic elements, such as developmental, behavior and attitude, and skills and performance, except for ToP that views the intrinsic factor (e.g., motivation) of play.

In terms of availability, majority of the instruments are not commercially available. Only the ChIPPA, Knox PPS, and ToP are made commercial. However, ChIPPA is the costliest, whereas the other two are at an affordable range. For the other instruments, contacting the author to obtain the original instrument may be required. The utility description of each instrument is presented in Table 4.

Table 4.

Usability of the instruments.

| Instrument | Description | Procedure | Population | Administration | Duration | Scoring | Training requirement | Accessibility |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Child-Initiated Pretend Play Assessment (ChIPPA) (i) I-ChIPPA |

Assessment of the quality of a child's ability to self-initiate pretend play. | Observation on two play scenarios [15 minutes each, (i) conventional imaginative play using toys, (ii) symbolic play using “junk” materials]. | Children age 3–7 years old | Therapist observation | 30 minutes | Actions observed were coded and then counted to be translated into raw score. The raw score is then calculated in and transformed into percentage according to norm reference. | Self-learning through manual (75-minute video) | Require purchase |

| Extension of I-ChIPPA: Indigenous Play Partner Scale (IPPS) |

The extension (i.e., IPPS) provides an added evaluation on social aspect in play. | The IPPS added the observation on playing in pair. | For indigenous Australian | Similar to original instrument | Simultaneously with the original evaluation duration | Additional scoring on initiative playing in pair for social context. | Additional reading on the journal article | Part of the original purchase |

| Knox's Preschool Play Scale (i) Knox Play Scale (ii) Preschool Play Scale (iii) Revised Knox's Preschool Play Scale |

The instrument has been evolved over time. The instrument is to evaluate children's developmental play ages. | Consist of 4 dimensions (space management, material management, pretense/symbolic, participation) and 12 categories of play behaviors. 30-minute observation each for inside and outside play. | Children age 0 – 6 years old. | Observation | 1 hour | Each category (a.k.a. factor) is scored with either a+ when the behavior was present, a− when the behavior was absent, or NA when no opportunity to observe. The scoring is according to age, and play development is scored by transforming into mean score on factor/dimension. | Not required. Self-training by reading the manual | Require purchase |

| McDonald Play Inventory | The instrument is to measure play frequency and play style. | The instrument consists of two parts. Part one (i.e., MPAI) has four categories, and part two (i.e., MPSI) has six domains with a total of 80 items. | Children age 7–11 years old | Self-reported (children) Proxy-reported (parents) |

15 minutes (without assistance) 20–30 minutes (with assistance) |

Each item was scored on a five-point Likert scale. Total score is calculated by summing-up the individual scores for each part. | No training required | May need to contact the author |

| My Child's Play | The instrument is to measure parent's perception on child' play performance. | The instrument has four categories with a total of 45 items. | Children age 3–9 years old | Proxy-administered (parents) | Not mentioned | Each item was scored on a five-point Likert scale. Total score is calculated by summing-up the individual scores. Higher score indicates better outcome. | No training required | May need to contact the author. Possible to replicate from the article |

| Play Assessment for Group Settings (PAGS) | The instrument is to evaluate attitude on organized and imaginative play. | The instrument has 38 items and evaluated by observation during play activities in several occasions. | Children age 2–8 years old | Professional rater | No specific duration | Each item was scored on four-point Likert scale. The raw score is totaled from the individual items and then computed and transformed to logits. | No to minimal training (or self-training) | May need to contact the author. Possible to replicate from the article |

| Play History Interview | A semistructured qualitative questionnaire to identify play experiences, interactions, environments, and opportunities. | Five epochs: sensorimotor, symbolic and simple constructive, dramatic and complex constructive and pregame, games, recreational. |

Children age 0–16 years old | Therapist interviewing the caregivers | Not specified | Qualitative response on each epoch—materials (what), action (how), people (with whom), setting (where). | Encourage to be trained | May need to contact the author. Difficult to reproduce from the journal article |

| Playform (i) Child form (ii) Parent form (iii) Teacher form |

The instrument is to evaluate child's play competency. | The instrument has 20 items. | Children age 5–7 years old | Self-administered (children) Proxy-administered |

Average 15 minutes (range 10–25 minutes) | Scored each item on three-point Likert scale (“not very well,” “quite well,” “very well”). Total score is by counting the “very well” response. | No training required | May need to contact the author. Unable to reproduce from the journal article |

| Test of Playfulness (ToP) | The instrument is to evaluate intrinsic and internal component that reflects a child's transaction in a play context. | The instrument has four elements with a total of 29 items. | 6 months–18 years old | Therapist observation | 15 minutes | Each item was scored on four-point Likert scale. The score is then totaled overall from raw score and converted into a measure score. | Self-training by reading the manual | Require purchase |

| Extension of ToP: Test of Environmental Supportiveness (TOES) |

The instrument is to evaluate the element of environment that influences play. | The instrument has 17 items and focuses on five elements. | 15 months–12 years old | Similar to original instrument | Simultaneously with the original evaluation duration | Each item was scored on four-point Likert scale. The score is then totaled overall from raw score and converted into a measure score. | Self-training by reading the manual | Part of the original purchase |

4. Discussion

This review found various play instruments where only a small number were developed by an occupational therapist. Some of the instruments were also mentioned and described in the previous reviews [6, 9–11], and some of them are newly identified. Clemson and colleagues [131] suggested that an instrument should have at least evidence on content validity and interrater reliability. Conversely, Prinsen et al. [132] specified that an instrument should at least establish a psychometric evidence on content validity, followed by the internal structure of the instrument (i.e., structural validity, internal consistency, and cross-cultural validity). The instruments found in this review had at least basic psychometric property. However, when compared to other function-based instruments for children [8], the play instruments found have limited number of psychometric properties investigated. The psychometric investigation of the instruments was mostly around interrater reliability and content validity. Therefore, investigation on the other psychometric properties is warranted. In addition, the methodological quality of the studies is moderate. Aspects such as sample characteristics of the population type, number, size of the client participants and assessor participants, and generalizability can further be improved.

Several occupational therapy play instruments are recommended based on occasion. The Revised Knox Preschool Play Scale is considered the gold standard for occupational therapy play assessment and suitable to be used to evaluate extrinsic aspect of play. The Revised Knox Preschool Play Scale is an all-rounder that covers an extensive number of domains. Moreover, it is the most common play instrument tool used by occupational therapists and considered easy to administer [16]. In addition, the instrument is accepted across discipline such as psychologist and speech therapist, thereby becoming a good communication tool between disciplines. The Test of Playfulness and its extension, the Test of Environmental Supportiveness, are a unique instrument that can be used across the widest age range and evaluate the internal element of play, such as motivation; however, the latest innovation of instruments, known as ToP-TOES Unifying Measure (T-TUM), is a promising play instrument. The Revised Knox Preschool Play Scale and Test of Playfulness utilized observation. Observation provides qualitative findings that are useful and valuable for practitioners to complement their evaluation finding on the quantitative outcome [17]. However, using observational instruments may be less favorable for busy practitioners and on setting with various constrains [6]. Therefore, a questionnaire-based instrument is sought, and the My Child's Play instrument can be potentially used for this purpose. The selection of those instruments over the others considers the balance on the clinimetric properties. Psychometric evidence only does not guarantee an instrument application in practice; clinical utility of the instruments also plays a crucial role [28, 133]. Nevertheless, play instruments in occupational therapy remain immature and evolving; therefore, several potentials and opportunities are available to explore a new instrument development or improve the currently available instruments.

Play is an activity that may be influenced by geosociocultural environment surrounding a person [6, 17]. Cultural value may impose a meaning on an activity, including play. For example, a study by Dender and Stagnitti [107] found that indigenous children appreciate animal toys that resemble their culture compared to the common commercialized farm animal toys. Moreover, children struggle to perform pretend play using the given “scrap” materials because the material is foreign to their culture. In addition, the indigenous children also have difficulty to play alone as mostly the play activity happen in pair or group in the indigenous culture. Most instruments were developed in a developed and Western-influenced country, such as Australia and the United States. Thus, using an instrument developed in one culture to another distinct cultural group may unfairly disadvantage the latter one [134]. The accuracy of an instrument may be reduced; however, improper remedial of the instrument to suit another cultural need may affect the validity of the instrument where it cannot inform any group evaluated. The cross-cultural investigation on functional instrument tools for children is emphasized and warranted [135]. Limited investigation on cross-cultural validity has restricted the widespread applicability of play instruments internationally. Therefore, the usability of play instruments can widely be investigated among cross-countries.

Authorship bias may exist from included studies, and this may compromise the report quality of the article. Involvement of the developer or creator of the instrument in the included studies may have contributed toward bias on the discussion of findings such as emphasizing on positive arguments and suppressing negative outcomes [136]. Only the Knox PPS was found to minimize the impact of the authorship bias; all included studies on Knox PPS have little to no involvement of the original developer of the instrument. Involvement of the original developer has its benefits such as encouraging the promotion and research on the particular instrument but may be associated with challenges such as the aforementioned bias. Hence, any conflict of interest and funding disclosure should be properly addressed [137]. Readers should cautiously assess the information to ensure reaching a neutral decision.

The clinical utility is another aspect that should be considered besides the psychometric property of an instrument. Although this review did not extensively search for clinical utility, majority of instruments embedded a report on the clinical utility of instruments such as the ChIPPA (see Pfeifer et al. [120]). Some instruments such as Test of Playfulness reported the clinical utility in a separate publication [138]. Clinical utility aspects that warranted attention from researchers are on appropriateness (e.g., importance of clinical decision-making and impact on the existing treatment process), accessibility (e.g., cost-effectiveness, availability, and support by peer-professionals and organizations), practicability (e.g., suitability across settings and professional and training requirement), and acceptability (e.g., ethical, social, or psychological concern) [139]. Most of the publications reported the duration of administration and training requirement. However, explicit clinical utility should be reported together with the psychometric property publication of the instruments. This will increase the relevancy of instruments to be used by practitioners.

Majority of play instruments focused on preschool and school-aged children; limited for newborns, infants, and toddlers; and negligible for adolescents. While play is known as the dominant activity for children, its essence is available across lifespan [6, 140, 141]. The neglected populations are somewhat denied on their right to play. Other disciplines such as psychology have carefully considered this approach. For example, the Fair Play Questionnaire is a generic instrument that evaluates the social and ethical opportunity of adolescents in play participation especially in structured play [86]. Other studies investigated instruments to evaluate the playfulness among older people [83, 99]. As the developmental stages become more mature such as adolescents and adults, play concept usually inhibited and replaced with leisure [140], and this is where play evaluation is not a priority. For example, Henry [60] and Trottier et al. [63] examined the instrument on leisure aspect of adolescents as this concept becomes the main focus compared to play during this stage of the lifespan. However, play element should continue to be investigated across the lifespan.

4.1. Implication to Practice

Play has been argued as a complex construct and influenced by relative multidimensionality. Only a study by Rigby and Gaik [121] investigated the stability of measuring play in several settings (i.e., home, community, and school) which found that it may influence the playful experience but not exclusive to the specific type of setting. For example, one child may experience the highest level of playfulness at home and lowest at school, whereas another child may experience otherwise. Another study by Kielhofner et al. [41] showed that environmental setting and involved personnel significantly contribute toward the play quality. This warranted an attention to consider the environment as a mediating factor. Hence, among the play instruments found in this review, T-TUM has successfully addressed the issue of environmental effects but may require further investigation. On the other hand, a study by Hyndman et al. [100] indicate that play perception varies between days in a week and varies on happiness level perception before and after the play. This aspect was not extensively investigated in any occupational therapy play instrument. This information should be crucially considered when conducting play assessment to ensure consistent outcome and interpretation.

In practice, practitioners require an instrument that can provide information on extensive number of aspects, requires minimal training and low administrative burden, and is easy to interpret [21, 142]. However, occupational therapy practitioners should consider both characteristics (i.e., skills) and quality traits (i.e., enjoyment) on play either during the evaluation or intervention. Planning a play activity as intervention may support or inhibit the progression of clients depending on the appropriateness of planning. Using an appropriate standardized assessment is one of the ways to facilitate proper and evidence-based planning [21]. Having a good standardized assessment may provide confidence to practitioners in rationalizing the service [19, 20]. However, play is associated with various ambiguities, and the current development of existing instruments on play is limited to one small part of play as mentioned by Bundy [17]—“reducing play to skills” (p. 99)—that is unable to provide a holistic picture on the client's play condition. To address the current limitations, practitioners should exercise good clinical reasoning skills. Synthesizing the objective outcome (i.e., standardized assessment result) with clinical reasoning (i.e., values and belief) will strengthen the planning that benefits the client [6, 17, 143]. Therefore, practitioners should combine findings from the instrument with clinical reasoning for a better service.

4.2. Limitation and Recommendation

This systematic review has several limitations to be noted. First, articles included were only obtained from journal publications, and therefore, evidence on psychometric properties of the instrument may not be comprehensive. Several psychometric evidences such as content validity may be available in the manual instrument book such as ChIPPA [144]. Several instruments are only available in grey literature format that is not captured during the review search. For example, the Kid and Preteen Play Profile can be found in a book [145]. Second, the review only included publication in English language. Several articles found in this review were in foreign languages but excluded due to the limited ability to understand the articles. This is associated with disadvantages involving instruments that provide more psychometric evidences, especially on cross-cultural applicability. Third, some psychometric properties of the instrument are briefly reported as a small part of the original study (see, for example, Okimoto et al. [130]), which compromise reporting on the quality and inability to provide a detailed description on the psychometric evidence. Fourth, the use of Terwee's checklist is still not comprehensive enough to illustrate the available type of psychometric properties. Even the COSMIN taxonomy [132] does not provide the available extensive type of validity and reliability. According to Law and MacDermid [24], more than 25 types of validities and reliabilities were found. Therefore, future research may try to investigate other types of validity and reliability that can be added on the number of psychometric evidence of the instruments besides the existing ones. Nevertheless, this review can provide a comprehensive guideline for practitioners to select an appropriate play instrument in practice.

5. Conclusions

Several play assessments are available for occupational therapists used in practice. Outcome from standardized play instrument may convince stakeholders and clients to change their perception on play as a main goal for children rehabilitation. However, the current development of play instruments is immature and constantly evolving. Available instruments are constantly developed and continue to be improved. Nevertheless, several instruments such as the Revised Knox Preschool Play Scale are suitably used as a comprehensive play evaluation for extrinsic perspective of play. The Test of Playfulness + Test of Environmental Supportiveness Unifying Measure is promising in evaluating intrinsic perspectives of play. As both instruments utilized an observation approach, My Child's Play is a potential instrument for a questionnaire-based reported outcome. However, practitioners need to consider several aspects such as client's needs, support, and facility condition and exercise good clinical reasoning when selecting an instrument for use.

Acknowledgments

The protocol for this systematic review was registered on INPLASY (202040156) and is available in full on http://inplasy.com/ (doi:10.37766/inplasy2020.4.0156) as well as on PROSPERO (CRD42020170370). There were no requirements for an ethical review of this paper since no human participants were involved.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Novak I., Honan I. Effectiveness of paediatric occupational therapy for children with disabilities: a systematic review. Australian Occupational Therapy Journal. 2019;66(3):258–273. doi: 10.1111/1440-1630.12573. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cornell H. R., Lin T. T., Anderson J. A. A systematic review of play-based interventions for students with ADHD: implications for school-based occupational therapists. Journal of Occupational Therapy, Schools, & Early Intervention. 2018;11(2):192–211. doi: 10.1080/19411243.2018.1432446. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kuhaneck H., Spitzer S. L., Bodison S. C. A systematic review of interventions to improve the occupation of play in children with autism. OTJR: Occupation, Participation and Health. 2020;40(2):83–98. doi: 10.1177/1539449219880531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Schottelkorb A. A., Swan K. L., Ogawa Y. Intensive child-centered play therapy for children on the autism spectrum: a pilot study. Journal of Counseling & Development. 2020;98(1):63–73. doi: 10.1002/jcad.12300. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gomes N. R. R., Maia E. C., Varga I. V. D. Os benefícios do brincar para a saúde das crianças: uma revisão sistemática. Arquivos de Ciências da Saúde. 2018;25(2):47–51. doi: 10.17696/2318-3691.25.2.2018.867. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Stagnitti K. Understanding play: the implications for play assessment. Australian Occupational Therapy Journal. 2004;51(1):3–12. doi: 10.1046/j.1440-1630.2003.00387.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Romagnoli G., Leone A., Romagnoli G., et al. Occupational therapy's efficacy in children with Asperger's syndrome: a systematic review of randomized controlled trials. La Clinica Terapeutica. 2019;170(5):e382–e387. doi: 10.7417/CT.2019.2164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Romli M. H., Wan Yunus F., Mackenzie L. Overview of reviews of standardised occupation-based instruments for use in occupational therapy practice. Australian Occupational Therapy Journal. 2019;66(4):428–445. doi: 10.1111/1440-1630.12572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sturgess J. L. Current trends in assessing children’s play. British Journal of Occupational Therapy. 2016;60(9):410–414. doi: 10.1177/030802269706000908. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Brown T., Bourke-Taylor H. Children and youth instrument development and testing articles published in the American Journal of Occupational Therapy,2009–2013: a content, methodology, and instrument design review. American Journal of Occupational Therapy. 2014;68(5):e154–e216. doi: 10.5014/ajot.2014.012237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hilton C. L., Goloff S. E., Altaras O., Josman N. Review of instrument development and testing studies for children and youth. American Journal of Occupational Therapy. 2013;67(3):e30–e54. doi: 10.5014/ajot.2013.007831. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.O'Grady M. G., Dusing S. C. Reliability and validity of play-based assessments of motor and cognitive skills for infants and young children: a systematic review. Physical Therapy. 2015;95(1):25–38. doi: 10.2522/ptj.20140111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lifter K., Foster-Sanda S., Arzamarski C., Briesch J., McClure E. Overview of play. Infants & Young Children. 2011;24(3):225–245. doi: 10.1097/IYC.0b013e31821e995c. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Thompson B. N., Goldstein T. R. Disentangling pretend play measurement: defining the essential elements and developmental progression of pretense. Developmental Review. 2019;52(1):24–41. doi: 10.1016/j.dr.2019.100867. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ray-Kaeser S., Châtelain S., Kindler V., Schneider E. 2 The evaluation of play from occupational therapy and psychology perspectives. In: Besio S., Bulgarelli D., Stancheva-Popkostadinova V., editors. Evaluation of childrens' play: Tools and Methods. Warsaw, Poland: De Gruyter; 2018. pp. 19–57. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kuhaneck H. M., Tanta K. J., Coombs A. K., Pannone H. A survey of pediatric occupational therapists' use of play. Journal of Occupational Therapy, Schools, & Early Intervention. 2013;6(3):213–227. doi: 10.1080/19411243.2013.850940. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bundy A. Evidence to practice commentary: beware the traps of play assessment. Physical & Occupational Therapy in Pediatrics. 2010;30(2):98–100. doi: 10.3109/01942631003622723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lynch H., Prellwitz M., Schulze C., Moore A. H. The state of play in children’s occupational therapy: a comparison between Ireland, Sweden and Switzerland. British Journal of Occupational Therapy. 2017;81(1):42–50. doi: 10.1177/0308022617733256. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wadley C. C., Stagnitti K. The views and experiences of teachers, therapists and integration aides of play-based programs within specialist school settings. Journal of Occupational Therapy, Schools, & Early Intervention. 2020:1–14. doi: 10.1080/19411243.2020.1732261. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Unsworth C. A. Evidence-based practice depends on the routine use of outcome measures. British Jounal of Occupational Therapy. 2011;74(5):p. 209. doi: 10.4276/030802211X13046730116371. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Duncan E. A. S., Murray J. The barriers and facilitators to routine outcome measurement by allied health professionals in practice: a systematic review. BMC Health Services Research. 2012;12(1) doi: 10.1186/1472-6963-12-96. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fava G. A., Tomba E., Sonino N. Clinimetrics: the science of clinical measurements. International Journal of Clinical Practice. 2012;66(1):11–15. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-1241.2011.02825.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wright K., Golder S., Rodriguez-Lopez R. Citation searching: a systematic review case study of multiple risk behaviour interventions. BMC Medical Research Methodology. 2014;14(1) doi: 10.1186/1471-2288-14-73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Law M., Mac Dermid J. Evidence-Based Rehabilitation: A Guide to Practice. 3rd. United States of America: Slack Incorporated; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Terwee C. B., Bot S. D. M., de Boer M. R., et al. Quality criteria were proposed for measurement properties of health status questionnaires. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology. 2007;60(1):34–42. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2006.03.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Terwee C. B., Mokkink L. B., Knol D. L., Ostelo R. W. J. G., Bouter L. M., de Vet H. C. W. Rating the methodological quality in systematic reviews of studies on measurement properties: a scoring system for the COSMIN checklist. Quality of Life Research. 2012;21(4):651–657. doi: 10.1007/s11136-011-9960-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Yuen H. K., Austin S. L. Systematic review of studies on measurement properties of instruments for adults published in the American Journal of Occupational Therapy, 2009-2013. American Journal of Occupational Therapy. 2014;68(3):e97–e106. doi: 10.5014/ajot.2014.011171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Romli M. H., Mackenzie L., Lovarini M., Tan M. P., Clemson L. The clinimetric properties of instruments measuring home hazards for older people at risk of falling: a systematic review. Evaluation & the Health Professions. 2016;41(1):82–128. doi: 10.1177/0163278716684166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mokkink L. B., Terwee C. B., Knol D. L., et al. The COSMIN checklist for evaluating the methodological quality of studies on measurement properties: a clarification of its content. BMC Medical Research Methodology. 2010;10(1) doi: 10.1186/1471-2288-10-22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mokkink L. B., Terwee C. B., Gibbons E., et al. Inter-rater agreement and reliability of the COSMIN (consensus-based standards for the selection of health status measurement instruments) checklist. BMC Medical Research Methodology. 2010;10(1) doi: 10.1186/1471-2288-10-82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Flamand V., Massé-Alarie H., Schneider C. Psychometric evidence of spasticity measurement tools in cerebral palsy children and adolescents: a systematic review. Journal of Rehabilitation Medicine. 2013;45(1):14–23. doi: 10.2340/16501977-1082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Forhan M., Vrkljan B., MacDermid J. A systematic review of the quality of psychometric evidence supporting the use of an obesity-specific quality of life measure for use with persons who have class III obesity. Obesity Reviews. 2010;11(3):222–228. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-789X.2009.00612.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.MacDermid J. C., Walton D. M., Avery S., et al. Measurement properties of the neck disability index: a systematic review. Journal of Orthopaedic & Sports Physical Therapy. 2009;39(5):400–417. doi: 10.2519/jospt.2009.2930. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Rouleau D. M., Faber K., MacDermid J. C. Systematic review of patient-administered shoulder functional scores on instability. Journal of Shoulder and Elbow Surgery. 2010;19(8):1121–1128. doi: 10.1016/j.jse.2010.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Roy J. S., Desmeules F., MacDermid J. Psychometric properties of presenteeism scales for musculoskeletal disorders: a systematic review. Journal of Rehabilitation Medicine. 2011;43(1):23–31. doi: 10.2340/16501977-0643. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Roy J. S., MacDermid J. C., Woodhouse L. J. Measuring shoulder function: a systematic review of four questionnaires. Arthritis Care & Research. 2009;61(5):623–632. doi: 10.1002/art.24396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Roy J. S., MacDermid J. C., Woodhouse L. J. A systematic review of the psychometric properties of the Constant-Murley score. Journal of Shoulder and Elbow Surgery. 2010;19(1):157–164. doi: 10.1016/j.jse.2009.04.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hurff J. M. A Play Skills Inventory: a competency monitoring tool for the 10 year old. American Journal of Occupational Therapy. 1980;34(10):651–656. doi: 10.5014/ajot.34.10.651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Restall G., Magill-Evans J. Play and preschool children with Autism. American Journal of Occupational Therapy. 1994;48(2):113–120. doi: 10.5014/ajot.48.2.113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Morrison C. D., Bundy A. C., Fisher A. G. The contribution of motor skills and playfulness to the play performance of preschoolers. American Journal of Occupational Therapy. 1991;45(8):687–694. doi: 10.5014/ajot.45.8.687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kielhofner G., Barris R., Bauer D., Shoestock B., Walker L. A comparison of play behavior in nonhospitalized and hospitalized children. American Journal of Occupational Therapy. 1983;37(5):305–312. doi: 10.5014/ajot.37.5.305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hess L. M., Bundy A. C. The association between playfulness and coping in adolescents. Physical & Occupational Therapy in Pediatrics. 2009;23(2):5–17. doi: 10.1080/J006v23n02_02. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kim Y., Lee J. The development and validation of a playfulness scale for infants & toddlers. Korean Journal of Child Study. 2012;33(6):85–107. doi: 10.5723/KJCS.2012.33.6.85. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ermert C. Age, sex and diagnosis-specific differences in play of preschool children with the Scenotest: a study of the constructive validity of observation systems. Zeitschrift Fur Klinische Psychologie, Psychopathologie Und Psychotherapie. 1994;42(4):373–384. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Puttapuan P., Sriphetcharawut S. Cross cultural validity and reliability of the Kid Play Profile assessment for children aged 6-9 years: Thai version. Journal of Associated Medical Sciences. 2017;50(3) [Google Scholar]

- 46.Agaronov A., Leung M. M., Garcia J. M., et al. Feasibility and reliability of the System for Observing Play and Leisure Activity in Youth (SOPLAY) for measuring moderate to vigorous physical activity in children visiting an interactive children’s museum exhibition. American Journal of Health Promotion. 2016;32(1):210–214. doi: 10.1177/0890117116671074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Cassibba R., van Ijzendoorn M. H., D’Odorico L. Attachment and play in child care centres: reliability and validity of the attachment Q-sort for mothers and professional caregivers in Italy. International Journal of Behavioral Development. 2016;24(2):241–255. doi: 10.1080/016502500383377. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Favez N., Tissot H., Frascarolo F. Is it typical? The ecological validity of the observation of mother-father-infant interactions in the Lausanne Trilogue Play. European Journal of Developmental Psychology. 2017;16(1):113–121. doi: 10.1080/17405629.2017.1326907. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 49.George C., Solomon J. The attachment doll play assessment: predictive validity with concurrent mother-child interaction and maternal caregiving representations. Frontiers in Psychology. 2016;7(10) doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2016.01594. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Hamutoğlu N. B., Topal M., Samur Y., Gezgin D. M., Griffiths M. D. The development of the online player type Scale. International Journal of Cyber Behavior, Psychology and Learning. 2020;10(1):15–31. doi: 10.4018/IJCBPL.2020010102. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Levac D., Nawrotek J., Deschenes E., et al. Development and reliability evaluation of the movement rating instrument for virtual reality video game play. JMIR Serious Games. 2016;4(1):p. e9. doi: 10.2196/games.5528. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.McKenzie T. L., Cohen D. A., Sehgal A., Williamson S., Golinelli D. System for Observing Play and Recreation in Communities (SOPARC): reliability and feasibility measures. Journal of Physical Activity & Health. 2006;3(s1):S208–S222. doi: 10.1123/jpah.3.s1.s208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Niec L. N., Russ S. W. Children's internal representations, empathy, and fantasy play: a validity study of the SCORS-Q. Psychological Assessment. 2002;14(3):331–338. doi: 10.1037/1040-3590.14.3.331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Ray D. C., Purswell K., Haas S., Aldrete C. Child-centered play therapy-research integrity checklist: development, reliability, and use. International Journal of Play Therapy. 2017;26(4):207–217. doi: 10.1037/pla0000046. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Santos M. P. M., Rech C. R., Alberico C. O., et al. Utility and reliability of an App for the System for Observing Play and Recreation in Communities (iSOPARC®) Measurement in Physical Education & Exercise Science. 2016;20(2):93–98. doi: 10.1080/1091367X.2015.1120733. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Staiano A. E., Adams M. A., Norman G. J. Motivation for Exergame Play Inventory: construct validity and relationship to game play. Cyberpsychology. 2019;13(3):54–66. doi: 10.5817/CP2019-3-7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Stearns J. A., Wohlers B., McHugh T.-L. F., Kuzik N., Spence J. C. Reliability and validity of the PLAYfun tool with children and youth in Northern Canada. Measurement in Physical Education & Exercise Science. 2018;23(1):47–57. doi: 10.1080/1091367X.2018.1500368. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Tejeiro R. A., Espada J. P., Gonzálvez M. T., Christiansen P. Proprietes psychometriques de l'echelle Problem Video Game Playing chez les adultes. Revue Europeenne de Psychologie Appliquee. 2016;66(1):9–13. doi: 10.1016/j.erap.2015.11.004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Veitch J., Salmon J., Ball K. The validity and reliability of an instrument to assess children's outdoor play in various locations. Journal of Science & Medicine in Sport. 2009;12(5):579–582. doi: 10.1016/j.jsams.2008.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Henry A. D. Development of a measure of adolescent leisure interests. American Journal of Occupational Therapy. 1998;52(7):531–539. doi: 10.5014/ajot.52.7.531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.King G., Rigby P., Avery L. Revised Measure of Environmental Qualities of Activity Settings (MEQAS) for youth leisure and life skills activity settings. Disability & Rehabilitation. 2015;38(15):1509–1520. doi: 10.3109/09638288.2015.1103792. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.King G., Rigby P., Batorowicz B., et al. Development of a direct observation measure of environmental qualities of activity settings. Developmental Medicine & Child Neurology. 2014;56(8):763–769. doi: 10.1111/dmcn.12400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Trottier A. N., Brown G. T., Hobson S. J. G., Miller W. Reliability and validity of the Leisure Satisfaction Scale (LSS – short form) and the Adolescent Leisure Interest Profile (ALIP) Occupational Therapy International. 2002;9(2):131–144. doi: 10.1002/oti.161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Arestad K. E., MacPhee D., Lim C. Y., Khetani M. A. Cultural adaptation of a pediatric functional assessment for rehabilitation outcomes research. BMC Health Services Research. 2017;17(1):p. 658. doi: 10.1186/s12913-017-2592-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Åström F. M., Khetani M., Axelsson A. K. Young Children's Participation and Environment Measure: Swedish cultural adaptation. Physical & Occupational Therapy In Pediatrics. 2018;38(3):329–342. doi: 10.1080/01942638.2017.1318430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Batorowicz B., King G., Vane F., Pinto M., Raghavendra P. Exploring validation of a graphic symbol questionnaire to measure participation experiences of youth in activity settings. Augmentative and Alternative Communication. 2017;33(2):97–109. doi: 10.1080/07434618.2017.1307874. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Bult M. K., Verschuren O., Kertoy M. K., Lindeman E., Jongmans M. J., Ketelaar M. Psychometric evaluation of the Dutch version of the Assessment of Preschool Children's Participation (APCP): construct validity and test–retest reliability. Physical & Occupational Therapy In Pediatrics. 2013;33(4):372–383. doi: 10.3109/01942638.2013.764958. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Chen C. L., Chen C. Y., Shen I. H., Liu I. S., Kang L. J., Wu C. Y. Clinimetric properties of the Assessment of Preschool Children's Participation in children with cerebral palsy. Research in Developmental Disabilities. 2013;34(5):1528–1535. doi: 10.1016/j.ridd.2013.01.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Chien C. W., Li-Tsang C. W. P., Cheung P. P. P., Leung K. Y., Lin C. Y. Development and psychometric evaluation of the Chinese version of the Participation and Environment Measure for Children and Youth. Disability and Rehabilitation. 2019:1–11. doi: 10.1080/09638288.2018.1553210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Golos A., Weintraub N. The psychometric properties of the Structured Preschool Participation Observation (SPO) Physical & Occupational Therapy In Pediatrics. 2020:1–13. doi: 10.1080/01942638.2020.1711845. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Kang L. J., Hwang A. W., Palisano R. J., King G. A., Chiarello L. A., Chen C. L. Validation of the Chinese version of the Assessment of Preschool Children’s Participation for children with physical disabilities. Developmental Neurorehabilitation. 2016;20(5):266–273. doi: 10.3109/17518423.2016.1158746. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Khetani M. A., Graham J. E., Davies P. L., Law M. C., Simeonsson R. J. Psychometric properties of the Young Children's Participation and Environment Measure. Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation. 2015;96(2):307–316. doi: 10.1016/j.apmr.2014.09.031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Khetani M. A. Validation of environmental content in the young children's participation and environment measure. Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation. 2015;96(2):317–322. doi: 10.1016/j.apmr.2014.11.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.King G., Batorowicz B., Rigby P., McMain-Klein M., Thompson L., Pinto M. Development of a measure to assess youth Self-reported Experiences of Activity Settings (SEAS) International Journal of Disability, Development and Education. 2014;61(1):44–66. doi: 10.1080/1034912X.2014.878542. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Law M., King G., Petrenchik T., Kertoy M., Anaby D. The assessment of preschool children's participation: internal consistency and construct validity. Physical & Occupational Therapy In Pediatrics. 2011;32(3):272–287. doi: 10.3109/01942638.2012.662584. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Lim C. Y., Law M., Khetani M., Pollock N., Rosenbaum P. Establishing the cultural equivalence of the Young Children's Participation and Environment Measure (YC-PEM) for use in Singapore. Physical & Occupational Therapy In Pediatrics. 2016;36(4):422–439. doi: 10.3109/01942638.2015.1101044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Lim C. Y., Law M., Khetani M., Rosenbaum P., Pollock N. Psychometric evaluation of the Young Children's Participation and Environment Measure (YC-PEM) for use in Singapore. Physical & Occupational Therapy In Pediatrics. 2018;38(3):316–328. doi: 10.1080/01942638.2017.1347911. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Williams U., Law M., Hanna S., Gorter J. W. Using the Young Children’s Participation and Environment Measure (YC-PEM) to describe young children’s participation and relationship to disability and complexity. Journal of Developmental and Physical Disabilities. 2019;31(1):135–148. doi: 10.1007/s10882-018-9637-6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Aydin A. Turkish adaptation of Test of Pretended Play. Educational Sciences: Theory & Practice. 2012;12(2):916–925. [Google Scholar]