Abstract

The purposes of this study were to identify the sexuality-related topics parents and gay, bisexual, or queer (GBQ) adolescent males discussed at home and to describe the topics GBQ adolescent males recommend for parents to discuss with future cohorts of GBQ youth. Minimal research on parent-child sex communication with sexual minority adolescents prevents the development of interventions that would benefit adolescent males with same-sex attractions, behaviors and identities. As part of a multimethod qualitative study, we interviewed 30 GBQ adolescent males ages 15-20 and asked them to perform card sorts. From a list of 48 topics, we explored sexuality-related issues GBQ males were familiar with, the topics they discussed with a parent, and topics they suggested parents address with GBQ males at home. Most participants reported that parents assumed them heterosexual during sex talks prior to GBQ adolescent males’ coming out. Participants challenged the heteronormative scripts used by parents when discussing sex and health. Participants identified sexuality topics that parents did not routinely cover during sex talks, but that GBQ youth felt would have been useful for them growing up with emergent identities. A non-heteronormative approach to parent-child sex communication is recommended to provide appropriate guidance about sex and HIV/STI prevention to this youth population. Our findings highlight a need to reconfigure parental sexuality scripts to be more inclusive when assisting GBQ males navigate adolescence.

Keywords: parent-child sex communication, GBQ youth, card sorts, young men who have sex with men, safer sex

INTRODUCTION

The need to implement early-age comprehensive sexual health interventions for gay, bisexual, and queer (GBQ) adolescent and young adult males is increasing as this population remains disproportionately affected by HIV/STI incidence in the United States.1 Among HIV infections in the U.S. for adolescents and young adult males in 2017, 94.2% were though male-to-male sexual contact.2 Nationally, sex education in school systems often fails to provide a foundational understanding of sexuality-related health topics and skills relevant to GBQ adolescent and young adult males, and when done, are provided in a non-affirming manner.3,4 Given that around 7% of U.S. adolescent males identify as gay, bisexual or categorize their sexual orientation as unsure,5 there is a need for proximal resources that can answer their emergent questions and facilitate their learning about same-sex oriented behavior and health issues.6

Experts in adolescent and young adult sexual health recognize the need for alternative, interpersonal approaches, specifically capitalizing on parents’ investment in their child’s well-being,7 to fill the void in providing comprehensive sexual health education to GBQ adolescent males.8-9 As the national average age of GBQ adolescent and young adult males disclosing their same-sex attractions continues to decrease,10-11 this presents parents and other guardian figures with an important opportunity to increase their involvement in positively shaping their child’s sexual health development.12 For instance, family acceptance is predictive of greater GBQ self-esteem and protects youth against depression, substance abuse, and suicidality,12 while those who lack family support report greater distress across adolescence and young adulthood compared to GBQ youth with supportive families.14 Further, parents are in a unique position to help socialize GBQ adolescents and young adult males into healthy sexual behaviors, both by providing accurate information about sex and by fostering responsible sexual decision-making skills.15

Parent-child sex communication – bidirectional conversations about sex and sexuality-related issues between parents and children – has been linked with adolescents’ increased engagement in HIV/STI risk reduction strategies (e.g., resisting sexual peer pressure, increased condom use, and increased access to sexual health services).16-20 The majority of parent-child sex communication research, however, has been conducted among presumably heterosexual parent-child dyads, with minimal information on how conversations occur between parents and GBQ male dyads.15-16 Young people, in general, have indicated a greater desire for parents to talk about sex more frequently, at earlier ages, and about a wide range of topics.21 Despite willingness to have sexual health discussions with their GBQ child, many parents are challenged by communication-related barriers. These include not having sufficient knowledge about GBQ-specific sex practices and health needs,22 feelings of awkwardness when talking about topics of a sexual nature,23 and a lack of credible resources that they can access to facilitate sensitive discussions.24 Youth perspectives on appropriate sexual health topics for parent-child sex conversations will not only inform the breadth of topical needs for parent-child sex discussions with GBQ adolescent and young adult males but will also provide programmatic insight that will help address parents’ communication barriers.

Sexual script theory provides a useful framework for examining parent-child sex communication between parents and their GBQ sons.25 Sexual scripts elucidate how individuals think about sexuality in the context of their social and cultural values and offers insight into individuals’ “blueprints” for socially acceptable sexual behavior and experiences.26 One sexual script that dominates Western cultures, the traditional sexual script,27 identifies sexual intercourse between heterosexual cisgender (congruence of sex at birth and gender identity) men and women as “real sex.” This sexual script excludes sexual and gender minorities by failing to recognize the full spectrum and fluidity of sexual behaviors occurring between persons of diverse genders and sexual orientations.28-29 The heteronormative sexual scripts that privilege penile-vaginal sexual intercourse between heterosexual cisgender men and women in turn impacts how parents communicate with their children about sex and sexuality.

Emerging research on sex communication between sexual and gender minority youth and their parents describe parent’s lack of understanding about LGBTQ-specific topics as a barrier to inclusive sex talks at home.22,24 For GBQ adolescents who report receiving sexual health information from parents, they recall discussing how to say no to sex, HIV prevention, and methods of birth control.30 However, discussions about sex and dating have been found to decrease after GBQ sons come out,31 while another study found a risk relationship between communicating with parents about abstinence, condom use, and choosing partners with recent unprotected anal intercourse.32 Nevertheless, given prior findings demonstrating GBQ adolescent and young adult males’ preference for parents as their source for sexual health information33-34 and maternal sex communication associated with routine HIV testing,35 we sought to identify from GBQ adolescent and young adult males the sex-related topics (or lack thereof) discussed between parents and GBQ children and to describe the sex-related topics they believe parents should address with future cohorts of GBQ youth.

METHODS

Data for this study comes from a multimethod qualitative investigation that explored the experiences and perspectives of GBQ adolescent and young adult males regarding parent-child sex communication. Youth in this study participated in a card sort activity (described below) as part of a semi-structured interview. The semi-structured interview aimed to gather the rich descriptions and meanings they attributed to many of the topics they discussed about this sensitive parent-child interaction.36 Full details of the development of the interview guide, data collection procedures, and interview analyses are described elsewhere.37 All demographic surveys, interviews, and card sorts were conducted by a young, racial/ethnic, gay adult with training in qualitative research methodologies and extensive HIV prevention experience with GBQ youth from diverse backgrounds in both clinical and community settings. Most interviews occurred at private offices within student community centers while some occurred during off-peak hours (minimal customer traffic) at coffee shops and restaurants picked by participants. A waiver of parental consent was secured from the Duke University IRB to accommodate the participation of youth under the age of 18 who may not have yet disclosed their sexual orientation to parents or youth from unsupportive families.38

Study Participants

Participants were eligible if they were cisgender adolescent and young adult males who self-identified as GBQ, were between 15 to 20 years old, and could recall at least one conversation with a parent about sex. We used purposive, maximum variation sampling to ensure racial/ethnic diversity and recruited from Gay-Straight Alliances in high schools; lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and queer (LGBTQ) student centers at universities; and community events in central North Carolina. Prior to and throughout recruitment, our research staff consulted with key stakeholders from the local LGBTQ community and sought their input regarding how best to identify and approach other recruitment sites and potential participants. We recruited 30 participants, who provided informed consent prior to in-depth interviews and the card sort activity.

Card Sort Materials

Card sorting is a strategy that has been used to determine priority goals,39 identify learning needs,40 and develop interventions.41 In this study, participants were asked to perform a series of card sorts to determine the various sex-related topics that were discussed with parents as well as which topics future groups of GBQ adolescent and young adult males should know about from their parents. Overall, card sorting was an ideal methodology since participants were able to think aloud and provide their rationale while sorting the cards.42 Additionally, card sorting was efficient, simple to administer, and easily understood by the participants.43

There were 28 pre-printed cards with general topics (e.g., human anatomy, dating, STIs) chosen from published sex communication research applicable to all adolescents44 and topics pertaining to GBQ adolescent and young adult males (e.g., anal sex), which were identified in consultation with health professionals specializing in sexual minority health. The pre-printed cards had a uniform font on 4x8-inch laminated cards, which facilitated the manipulation and organization of the cards.40,42 Additional blank cards were also provided for topics that participants wanted to add. These blank cards were also used to write down emerging concepts unknown to the interviewer, regional/slang words, or topics previously not documented in the sex communication literature. The participant-identified emergent topics were added to the original pile and shown to subsequent participants.

Card Sort Procedures

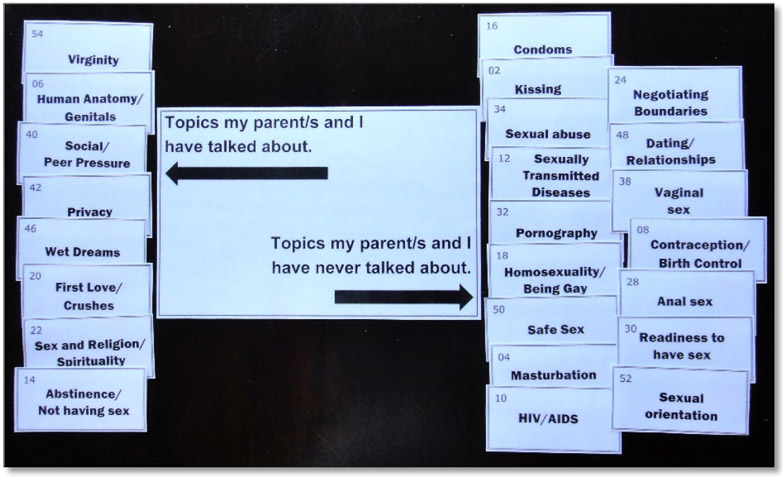

Table 1 lists the questions asked during the card sort. In the first card sort, participants organized 28 proposed topics based on whether or not they were familiar with the topics identified from prior literature and consultation with sexual minority health experts. The total number of topics was within the range of topics recommended for card sorts.45 In this first round of the card sort activity, participants also proposed emergent sex-related topics that they felt were relevant to comprehensive sexual health education among GBQ adolescent and young adult males. The second card sort involved participants recalling topics that parents discussed with them (Figure 1). The third card sort elicited topics participants thought parents should discuss with future cohorts of GBQ adolescent and young adult males who had either disclosed their sexuality or whose parents suspected may have same-sex attractions, behaviors, or identities. Throughout the card sorts, the participants were asked to explain why they sorted a certain way or to elaborate on how to best implement their recommendations. The card sorts lasted anywhere between 30 minutes to an hour per participant.

Table 1.

Card Sorting Questions

| Instructions/Question |

|---|

|

Figure 1.

Sample card sort

Card Sort Data Analysis

After each interview, audio recordings were transcribed verbatim, and card-sort tabulation forms verified by listening to the audio recordings and reviewing the tabulation sheet. For each of the three card-sort questions, the percent of participants selecting a given topic (card) was calculated. The percent for an emergent topic was calculated based on the number of participants who had the topic available as an option when addressing the question. For analysis, data initially entered into unique Excel files for each card sort were converted to SAS 9.3 dataset. Finally, we juxtaposed the proportion of participants who indicated topics based on familiarity, ever discussed with a parent, and whether they recommend specific topics as necessary for effective parent-child sex communication.

RESULTS

Participants

Among participants, 23 (76%) identified as gay, 5 (16.7%) as bisexual, and 2 (6.7%) as queer. Five participants were between 15 to 17 years old, while twenty-five (83%) were between 18 and 20 years old. Twenty-six participants (86.7%) reported having disclosed their sexual orientation to their parents. The racial/ethnic breakdown of participants included 11 (36.7%) White, 10 (33.3%) Latino, 4 (13.3%) Black, 4 (13.3%) Asian, and one (3.3%) multiracial (Table 2). Nineteen participants (67%) did not live with their parents at the time of the interviews. The mean age of the participants was 18.5 years.

Table 2.

Demographic Characteristics, N=30 GBQ adolescents and young adults

| Variable | n (%) |

|---|---|

| Sexual Orientation | |

| Gay | 23 (76.7) |

| Bisexual | 5 (16.7) |

| Queer | 2 ( 6.7) |

| Race/Ethnicity | |

| Asian | 4 (13.3) |

| Black | 4 (13.3) |

| Latino | 10 (33.3) |

| Multiracial | 1 ( 3.3) |

| White | 11 (36.7) |

| Education | |

| High School | 9 (30.0) |

| College | 21 (70.0) |

| Age | |

| 15 – 17 years | 5 (17) |

| 18 – 20 years | 25 (83) |

| Residence | |

| Living with parent/s | 11 (37) |

| Not living with parents | 19 (63) |

| Parents’ Awareness of Son’s Sexual Orientation | |

| Definitely Knows | 26 (86.7) |

| Probably Knows | 1 ( 3.3) |

| Probably Does Not Know | 2 ( 6.7) |

| Definitely Does Not Know | 1 ( 3.3) |

Most Familiar Topics

Familiarity with the 28 topics proposed based on prior literature and sexual minority health experts was high across all topics (Table 4), ranging from 83.3% (e.g., emotions and online dating) to 100% familiarity (e.g., oral sex, homosexuality, and pornography). When questioned about their level of familiarity with these topics, the majority of participants suggested that they could clearly explain the concepts of the given topic, but did not necessarily have actual experience with that topic. In addition to these 28 topics, participants suggested 20 additional sex-related topics with which they were familiar and warranted consideration for effective parent-sex communication (Table 3). These topics included conversations related to safety and health (e.g., fembashing [violence targeted to non-masculine males]; alcohol, drugs and sex; consent; pre-exposure prophylaxis), discussions about dating and relationships (e.g., break ups, co-dependence, hook-up culture, polyamory, unrequited love, sexting, younger and older relationships), and knowledge about gender-related concerns (e.g., masculinity; transgender issues).

Table 4.

Top 30 (respectively) most frequent sexual health topics by card sorts activity

| Topic | Familiarity n (percentage) |

Discussed with Parent n (percentage) |

Recommended for Discussions n (percentage) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Abstinence/Not Having Sex | 30 (100.0%) | 18 (60.0%)b | 27 (90.0%) |

| Alcohol, Drugs and Sex | 17 (56.7%)a | 24 (80.0%) | |

| Anal Sex | 30 (100.0%) | 26 (86.7%) | |

| Break Ups | 13 (43.3%)b | ||

| Condoms | 30 (100.0%) | 22 (73.3%)a | 29 (96.7%) |

| Consent | 26 ( 86.7%) | 26 (86.7%) | |

| Contraception/Birth Control | 29 ( 96.7%) | 16 (53.3%)b | 26 (86.7%) |

| Dating/Relationships | 29 ( 96.7%) | 25 (83.3%)b | 28 (93.3%) |

| Emotions | 25 ( 83.3%) | 21 (70.0%)b | 25 (83.3%) |

| First Love/Crushes | 29 ( 96.7%) | 20 (66.7%)b | 28 (96.7%) |

| Harassment (by Peers) | 11 (36.7%)b | 29 (96.7%) | |

| HIV/AIDS | 29 ( 96.7%) | 17 (56.7%)a | 28 (93.3%) |

| Homosexuality/Being Gay | 30 (100.0%) | 24 (80.0%)a | 29 (96.7%) |

| Hook-Ups on Smart Phones | 26 ( 86.7%) | ||

| Human Anatomy/Genitals | 29 ( 96.7%) | 19 (63.3%)b | 26 (86.7%) |

| Kissing | 29 ( 96.7%) | 14 (46.7%)b | 27 (90.0%) |

| Masturbation | 30 (100.0%) | 15 (50.0%)b | 26 (86.7%) |

| Masculinity | 10 (33.3%)b | ||

| Multiple Sexual Partners (concurrent) | 29 ( 96.7%) | 13 (43.3%)a | 26 (86.7%) |

| Online Dating | 25 ( 83.3%) | 24 (80.0%) | |

| Oral Sex | 30 (100.0%) | 26 (86.7%) | |

| Pornography | 30 (100.0%) | 17 (56.7%)b | 26 (86.7%) |

| Privacy | 30 (100.0%) | 20 (66.7%)b | 28 (93.3%) |

| Readiness to Have Sex | 28 ( 93.3%) | 11 (36.7%)b | 26 (86.7%) |

| Safe Sex | 30 (100.0%) | 19 (66.7%)a | 29 (96.7%) |

| Sex and Religion/Spirituality | 16 (53.3%)b | ||

| Sexting | 12 (40.0%)a | 24 (80.0%) | |

| Sexual Abuse | 30 (100.0%) | 13 (43.3%)b | 29 (96.7%) |

| Sexual Coercion by a Partner | 29 ( 96.7%) | 28 (93.3%) | |

| Sexual Orientations | 30 (100.0%) | 25 (83.3%)a | 29 (96.7%) |

| Sexually Transmitted Infections | 30 (100.0%) | 17 (56.7%)a | 29 (96.7%) |

| Social/Peer Pressure | 29 ( 96.7%) | 23 (76.7%)b | 27 (90.0%) |

| Talking/Negotiating Boundaries | 24 (80.0%) | ||

| Tops and Bottoms | 26 ( 86.7%) | ||

| Vaginal Sex | 27 ( 90.0%) | 14 (46.7%)b | |

| Virginity | 30 (100.0%) | 21 (70.0%)b | 27 (90.0%) |

| Wet Dreams | 28 ( 93.3%) | ||

| Younger and Older Relationships | 12 (40.0%)a |

Notes:

Recalled as discussed mostly after sons’ GBQ identity disclosure

Recalled as discussed mostly before sons’ GBQ identity disclosure.

Table 3.

Original card sort topics and emergent topics suggested by participants

| Original topics identified from the literature and health experts |

Emergent topics added during the study by participants |

|---|---|

| Abstinence/ Not Having Sex | Alcohol, Drugs and Sex |

| Anal Sex | Asexuality |

| Condoms | Bisexuality |

| Contraception/ Birth Control | Break Ups |

| Dating/Relationships | Co-Dependence |

| Emotions | Consent |

| First Love/Crushes | Fembashing |

| Harassment (by peers) | Fetishes |

| Homosexuality/ Being Gay | Hook-up Apps on Smart Phones |

| HIV/AIDS | Hook-up Culture |

| Human Anatomy/ Genitals | Masculinity |

| Kissing | Mental Illness/ Mental Health |

| Masturbation | Online Dating |

| Oral Sex | Pre-Exposure Prophylaxis |

| Privacy | Polyamory |

| Pornography | Sexting |

| Readiness to Have Sex | Transgender Issues |

| Safe Sex | Tops and Bottoms |

| Sex and Religion/ Spirituality | Unrequited Love |

| Sexual Abuse | Younger and Older Relationships |

| Sexual Coercion by a Partner | |

| Sexual Orientation | |

| Sexually Transmitted Infections | |

| Social/Peer Pressure | |

| Talking/ Negotiating Boundaries | |

| Vaginal Sex | |

| Virginity | |

| Wet Dreams |

Topics Discussed with a Parent/Guardian

Participants described a variety of topics they had ever discussed with at least one parent or guardian. Discussed topics can also be classified based on if and when the participant had disclosed his GBQ sexual identity with his parent. Among the most common topics discussed with parents, 19 were primarily discussed pre-disclosure as GBQ and 10 were discussed after coming out. Prior to coming out, the most common topics discussed between parents and their GBQ son revolved around romantic interests (e.g., crushes), dating, virginity, and social/peer pressure. Most participants reported that these topics were discussed by parents with the assumption that they were heterosexual.

Topics that were salient to parent-child sex communication post-disclosure included conversations about being gay, safe sex, and condom use. Discussions about HIV and other STI’s were moderately discussed between parents and their GBQ sons, with a little over half (56.7%) of participants indicating these conversations. However, these participants noted that upon disclosure, their sexual orientation was specifically discussed along with warnings about HIV/AIDS and warnings against mixing alcohol, drugs, and sex. Specifically, parents’ sex discussions with their sons relied upon and reinforced stereotypes of gay men as being HIV-infected or at certain risk for HIV infection. One participant recalled:

“She was distraught, ‘I wish you didn’t have to live this kind of life that has more conflict…more things that could go wrong.’ She talked to me about AIDS like it was something that was totally going to happen…I was going to get AIDS at some point, and she didn’t want that. This was all on the phone… She kind of unloaded on me. It was a long conversation. She was tearful that I was gay” (D.S., 20 years old, White, gay).

As reflected by this quote, some participants indicated that while many parents were able to have conversations about sex-related topics with their sons post-sexual identity disclosure, many of these discussions were emotional in nature with parents expressing concern by projecting and perpetuating negative stereotypes of GBQ individuals. Despite their parental concerns, many participants reported hearing problematic messages after disclosure. One participant stated:

“She was like, ‘I just want to make sure you’re OK…You need to think about what this means. It’s a hard life to be gay.’ And I was like, ‘OK, it’s not going to change…the fact that I’m gay.’ And she kept saying silly stuff…microaggressions. She didn’t know she was being homophobic.” (M.E., 18 years old, Latino, gay)

Lastly, we identified eight topics that were very familiar among participants but were uncommonly or infrequently discussed with parents (Table 4). These topics tended to be more sexually explicit in nature including types of sex (e.g., oral and anal sex; tops and bottoms; hooking up via smart phones) and sexual safety (e.g., consent and sexual coercion from a partner).

Recommended Topics for Effective Parent-Child Sex Communications

As seen in Table 4, most of the recommended topics (n=26; 86.7%) that participants suggested were important to parent-child sex communication overlapped with topics with which they were most familiar. Four additional topics with which participants were less familiar/unfamiliar, but endorsed as necessary for discussions, were related to interpersonal safety (e.g., alcohol, drugs and sex; harassment by peers; sexting; and talking/negotiating boundaries). One participant opined:

“Regardless of how much we don’t like it, there is a lot of alcohol, a lot of drugs, and a lot of sex in our middle schools. It’s perfectly fine to let your child be aware that those things are there in middle school and that they will be a whole lot more prominent in high school!” (G.C., 18 years old, Black, bisexual)

Another participant felt strongly that sexting had implications for safety and shared:

“Parents should talk to gay sons about sexting because you never know what they’re doing. They may be sexting the wrong person and that will ‘open’ their minds when they’re not ready and will act stupidly. Boys can be sending nude pictures to one person who then sends it to another and it will go around the school. Then he will commit suicide.” (M.W., 20 years old, Latino, gay)

Six topics were endorsed as recommended for parent-child sex conversations but were not commonly discussed by participants and their parents. These topics included types of sexual behavior (e.g., anal and oral sex), sexual safety (e.g., consent; sexual coercion by a partner; talking/negotiating boundaries), and online dating. One participant suggested a way parents can broadly address sexual behavior:

“I’m not sure if I’m overthinking this topic, but parents should just say ‘Sex exists and sex is oral, anal, vaginal, etc.’ because hetero couples have anal sex and it’s becoming more prevalent. And HIV is prevalent in all these, but more easily contracted through anal sex. And given how the child responds to you, you can take it to the next level or NOT take it to the next level.” (I.H., 20 years old, Asian, gay)

Still another participant shared the importance of parents addressing sexual safety:

“Consent, coercion, and setting boundaries all go together. Understanding consent is always the first thing you should have before you have sex with anyone. Understanding sexual abuse – what to do to protect yourself and what to do to make sure you’re not a perpetrator. I’ve read of male-identified or gay students who are afraid to bring up that they were sexually abused because they didn’t think people would take them seriously or listen to them. Addressing [safety] from multiple standpoints is important early on.” (A.J., 19 years old, Black, gay)

We observed that almost half of the sample (n=14) recommended that parents address all original 28 topics and 20 emerging topics with their GBQ sons, with the remaining participants recommending the majority of those topics. When asked why parents should discuss all the topics on the cards, many participants agreed that each topic was a distinct concept relevant to future experiences of each GBQ youth. One participant explained:

“Each of those topics can be beneficial or harmful if you don’t know them. They’re very important. You may think it’s not important [until] you are in a situation -- you don’t really know. But if your parents discuss it with you, you’re more aware so you know what’s going to happen” (T.R., 19 years old, Latino, gay).

Finally, while linking recommendations to experiences based on the discussions they had with their parents (second card sort), participants recommended that future parent-guided conversations about sex should address these topics in a factual, non-judgmental manner. If parents were considering having discussions with sons who have just disclosed as GBQ, participants recommended inclusion of practical topics such as how to handle first same-sex crushes or what dating another GBQ adolescent male might be like.

The sample viewed conversations about sexual abstinence, readiness to have sex, and virginity as crucial, but requested that they be broached with a same-sex angle. One participant recommended ways for parents to encourage inclusive discussions:

“When you’re having the sex talk, you have to say ‘People have sex. Sometimes they choose not to. You can time when you want to initiate sex. Do you want to wait a while? Do you want to have it in college? How do you want to pace yourself? Because you won’t penetrate a woman, how do you define virginity? Have you had anal yet? Is it something you want to hold off on or maybe do sooner?’” (G.O., 19 years old, White, gay)

For them, discussions with parents about refraining from early sex was seen in the modern sense of waiting for the right male with whom to sexually debut after a sound relationship has been established – a narrative that, a generation or two earlier, was previously exclusive to their heterosexual peers.

DISCUSSION

The purposes of this study were to identify the sexuality-related topics GBQ adolescent and young adult males discussed with parents and to summarize topics that youth identified were crucial for parents to discuss with future cohorts of GBQ youth. Participants overwhelmingly endorsed the original and emergent topics as important to discuss between parents and their GBQ sons. Our findings from GBQ sons challenge the practice of heteronormative scripts and indicate a need for sexuality education through inclusive parent-child sex communication. As opposed to traditional sexual scripts, which for many were limited to the mechanics of heterosexual intercourse, the inclusive topics recommended for discussion by this sample reflect the more encompassing term sexuality which incorporates “sex, gender identities and roles, sexual orientation, eroticism, pleasure, intimacy and reproduction”.46 Based on this GBQ sample’s experiences, the comprehensiveness of their card sort recommendations is a response to parents’ limited and heteronormative socialization scripts.

Our findings support that many GBQ adolescent and young adult males face ongoing challenges to readily accessing parents/guardians as informational resources for needed and desired topics.47 According to many participants, parents had not discussed interpersonal issues related to safety (from sexual abuse, harassment from peers, or sexual coercion) or healthy sexual expression (e.g., anal or oral sex, masturbation). The topics that participants discussed most with their parents prior to disclosure as GBQ largely mirrored those reported in prior literature based on presumably heterosexual samples.15 These include human anatomy, an emphasis on abstinence and virginity, dealing with social/peer pressure, and dynamics between sex and religion. Thus, our findings indicate that sex communication pre-disclosure is framed within heteronormative expectations and traditional sexual scripts and is a missed opportunity for parents to teach sons about how to stay safe and how to protect themselves as young men with same-sex attractions and behaviors.

Similar to prior findings, participants in our study described discussions on homosexuality/being gay emerging as an often-covered topic after disclosure, along with parental emphasis on safe sex and minimizing risk for HIV and STIs.31 These conversations commonly perpetuated negative stereotypes of GBQ individuals. This finding adds to the evidence that despite parental concern for their child’s health and well-being,48 sex communication for many parents of GBQ adolescent and young adult males is a reactive or emotional process instead of a health-promotive conversation.32 Furthermore, having discussions about HIV and STIs post-disclosure without conversations about modes of transmission risk like oral or anal intercourse may suggest that parents are omitting critical pieces to sons understanding their sexual health.

It is important to note that while the sex topics recalled by the sample were based on stereotypes about gay men and their risks for HIV/STIs and appeared stigmatizing, more than half of these adolescents and young adults endorsed majority of the topics be discussed by parents with future cohorts of GBQ youth. Despite parental reliance on traditional sexuality scripts, parents are viewed as potential sources of sexual health information.37 A rewriting of parental sexual scripts and reconfiguration of expectations is necessary to meet their GBQ sons’ unique needs. GBQ adolescent and young adult males recommend more inclusive sex communication and suggest a positive approach that is at odds with how most parents themselves were raised. For these families, interventions supporting parents to become more knowledgeable about GBQ topics is therefore of prime importance. Parents’ heteronormative sexual scripts and knowledge gaps must be addressed before sons turn to unreliable sources such as sexually explicit media.47 Supportive parental intervention can address barriers related to communication discomfort, lack of LGBT-specific knowledge and addressing the ambient heteronormativity noted in U.S.-based sex communication literature.15, 24

Despite the breadth of topic considerations explored with our GBQ participants regarding parent-child sex communication, there are a few limitations that should be noted in this study. First, our participants indicated that they came from supportive families, which is often variable among GBQ adolescent and young adult males. Of the 26 participants whose parents knew of their sexual orientation, only one reported parental rejection and is currently living with a foster parent. Second, our participants came from a school-based sample who were heavily recruited from LGBTQ-serving organizations. The experiences of GBQ youth who are in jurisdictions outside of catchment areas for LGBTQ-serving organizations may differ considerably from our participants and are a particular concern since they may not be receiving any type of social support related to their sexual orientation and would most likely be the ones to maximally benefit from such services. Third, our recruitment flyers explicitly targeted gay, bisexual, or queer adolescents and young adult males, which may have inadvertently excluded youth with same-sex attractions and behaviors, but did not personally self-identify as GBQ. Also, the conversations and topics reported were based solely on adolescent GBQ individuals’ recollections and would benefit from parallel reports from parents. Relatedly, our sample was composed predominantly of younger adults who may have been subject to recall bias given that many parent-child sex communication may have occurred when they were younger. Relatedly, participants’ self-report of familiarity with the topics could have been influenced by social desirability bias that could have encouraged them to express familiarity despite not having full comprehension of a topic. While the interviewer asked follow-up questions when participants appeared uncertain about a topic yet claimed familiarity, the use of validated measures in future research could provide a better assessment of familiarity. Additionally, future studies should consider recruiting parent-child dyads for a more complete picture about how these conversations occur, the topics that are covered, and how parents can communicate with GBQ adolescent boys about sex in a manner that is sensitive to their same-sex attractions, behaviors, and identities. Finally, since our recommendations do not extend to GBQ individuals who are unable to disclose their sexual orientation to their parents during adolescence or early adulthood, quantitative surveillance methods may assist in reaching larger numbers of GBQ adolescent and young adult males from diverse backgrounds who would be more comfortable providing responses with greater anonymity.

Our study’s findings have important considerations for interventions that aim to promote inclusive parent-child sex communication. Our diverse sample of GBQ adolescent and young adult males challenged traditional sexual scripts that have been the norm when sex is discussed within parent and guardian dyadic interactions. Efforts are needed to educate parents of GBQ adolescent and young adult males on how and why traditional sexual scripts ineffectively provide their child with a sexual health knowledge base to enact risk reduction strategies. In addition, interventions should aim to alleviate parents’ sex communication barriers.22,24 This may be accomplished by identifying instrumental resources that increase parents’ efficacy to not only discuss topics such as sexual orientation in a more accepting and non-judgmental manner, unconstrained by heteronormative expectations (e.g., masculinity as traditionally defined), but also to address topics that are explicit and often uncomfortable. Additionally, salient sociocultural dynamics (e.g. religious background) that exist within family structures, along with personality characteristics of parents and teens (e.g. introversion/extroversion), may have proximal impact on inclusive sex communication and would benefit from future investigations. Also, parents and other primary guardians possess the power to normalize discussions on uncomfortable topics, which in the long-term may have a lasting health-promotive impact on their GBQ child’s sexual health development. Further, our sample made explicit a breadth of issues that are pertinent only to cisgender male adolescents and young adults. Unique as these findings are, this report cannot be extended to the sexual socialization needs of cisgender lesbian, bisexual or queer-identifying female adolescents. The same research questions are thus recommended to be explored among families with sexual minority female adolescents. Similarly, investigating sex communication between cisgender parents with transgender adolescents would be prudent since this is another youth group that is disproportionately affected by HIV/STI infections and for which parental sexual health resources are sparse (cite). Lastly, while this report was focused on the sex topics pertinent for home-based discussions with parents according to GBQ adolescent and young adults’ needs, the value of inclusive parent-child sex communication for parents with heterosexual children would also benefit from further study. Peers have been consistently identified as a source of sex information by sexual minority youth and are the resource GBQ adolescent and young adult males turn to when they do not receive inclusive sexual health information in their own homes.49

CONCLUSIONS

GBQ adolescent and young adult males recommend that parents re-examine the heteronormative parental sexual socialization scripts they use at home. Instead, GBQ adolescent and young adult males recommend that parent-child sex communication not assume that sons are heterosexual and be more inclusive of potential adolescent same-sex attractions, behaviors or identities. This study provided an extensive list of sexuality-related topics that are recommended for parents to address with GBQ adolescent and young adult males. While it may appear challenging for parents, topic recommendations from sons help to ensure that sex communication occurs in a way that GBQ adolescent and young adult males are able to process and retain information that is both needed and relevant. Parental sexuality communication scripts need to be reconfigured to meet the needs of this youth population. This reconfiguration begins with an inclusive approach to sex and sexuality.

Acknowledgements:

This study was funded by the National Institutes of Health (F31NR015013). The study also received supplementary funding from the Surgeon General C. Everett Koop HIV/AIDS Research Award. The funding sources had no involvement in the study design, data collection, analysis, interpretation, write-up or any decisions regarding the publication of results.

Abbreviations:

- GBQ

gay, bisexual, and queer

- HIV

Human Immunodeficiency Virus

- STI

sexually-transmitted infections

References

- [1].CDC. HIV and young men who have sex with men. 2014;1–4. https://www.cdc.gov/healthyyouth/sexualbehaviors/pdf/hiv_factsheet_ymsm.pdf. Accessed March 21, 2019.

- [2].CDC, 2017. https://www.cdc.gov/hiv/pdf/library/slidesets/cdc-hiv-surveillance-adolescents-young-adults-2017.pdf

- [3].Currin JM, Hubach RD, Durham AR, Kavanaugh KE, Vineyard Z, Croff JM. How gay and bisexual men compensate for the lack of meaningful sex education in a socially conservative state. Sex Education. 2017. November 2;17(6):667–81. 10.1080/14681811.2017.1355298 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Du Bois SN, Emerson E, Mustanski B. Condom-related problems among a racially diverse sample of young men who have sex with men. AIDS Behav. 2011. October 1;15(7):1342–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Kann L, Olsen EO, McManus T, et al. Sexual Identity, Sex of Sexual Contacts, and Health-Related Behaviors Among Students in Grades 9–12 — United States and Selected Sites, 2015. MMWR Surveill Summ 2016;65(No. SS-9):1–202. DOI: 10.15585/mmwr.ss6509a1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Parker Caroline M., et al. “The urgent need for research and interventions to address family-based stigma and discrimination against lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and queer youth.” J. of Adol Health 63.4 (2018): 383–393. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Mustanski B, Hunter J. Parents as agents of HIV prevention for gay, lesbian, and bisexual youth. In Pequegnat W, Bell C, eds. Families and HIV/AIDS. New York, NY: Springer; 2012:249–60. [Google Scholar]

- [8].Bouris A, Guilamo-Ramos V, Pickard A, et al. A systematic review of parental influences on the health and well-being of lesbian, gay, and bisexual youth: Time for a new public health research and practice agenda. J Prim Prev. 2010. December 1;31(5-6):273–309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Bauermeister JA, Johns MM, Sandfort TG, Eisenberg A, Grossman AH, D’Augelli AR. Relationship trajectories and psychological well-being among sexual minority youth. J Youth Adolesc. 2010. October 1;39(10):1148–63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Calzo JP, Antonucci TC, Mays VM, Cochran SD. Retrospective recall of sexual orientation identity development among gay, lesbian, and bisexual adults. Dev Psychol. 2011. November;47(6):1658. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Martos AJ, Nezhad S, Meyer IH. Variations in sexual identity milestones among lesbians, gay men, and bisexuals. Sex Res Social Policy. 2015. March 1;12(1):24–33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Bauermeister J, Connochie D Jadwin-Cakmak L, & Steven Meanley. (2017). “Gender Policing During Childhood and the Psychological Well-Being of Young Adult Sexual Minority Men in the United States.” American Journal of Men’s Health, 11, 693–701. 10.1177/1557988316680938. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Ryan Caitlin, et al. “Family acceptance in adolescence and the health of LGBT young adults.” J. of Child and Adol Psych Nrsg 23.4 (2010): 205–213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].McConnell Elizabeth A., Birkett Michelle, and Mustanski Brian. “Families matter: Social support and mental health trajectories among lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender youth.” J of Adol Health 59.6 (2016): 674–680. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Flores D, Barroso J. 21st century parent–child sex communication in the United States: A process review. J Sex Res. 2017. June 13;54(4-5):532–48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Widman L, Choukas-Bradley S, Noar SM, Nesi J, Garrett K. Parent-adolescent sexual communication and adolescent safer sex behavior: A meta-analysis. JAMA Pediatr. 2016. January 1;170(1):52–61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Kapungu CT, Baptiste D, Holmbeck G, et al. Beyond the “birds and the bees”: Gender differences in sex-related communication among urban African-American adolescents. Fam Process. 2010. June;49(2):251–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Widman L, Choukas-Bradley S, Helms SW, Golin CE, Prinstein MJ. Sexual communication between early adolescents and their dating partners, parents, and best friends. J Sex Res. 2014. October 1;51(7):731–41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Hall KS, Moreau C, Trussell J. Associations between sexual and reproductive health communication and health service use among US adolescent women. Perspect Sex Reprod Health. 2012. March;44(1):6–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Guilamo-Ramos V, Lee JJ, Jaccard J. Parent-adolescent communication about contraception and condom use. JAMA Pediatr. 2016. January 1;170(1):14–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Pariera KL, Brody E. “Talk more about it”: Emerging adults’ attitudes about how and when parents should talk about sex. Sex Res Social Policy. 2017:1–1.28824733 [Google Scholar]

- [22].Newcomb ME, Feinstein BA, Matson M, Macapagal K, Mustanski B. “I have no idea what’s going on out there:” Parents’ perspectives on promoting sexual health in lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender adolescents. Sex Res Social Policy. 2018. June 1:1–2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].LaSala MC. Condoms and connection: Parents, gay and bisexual youth, and HIV risk. J Marital Fam Ther. 2015. October;41(4):451–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Rose ID, Friedman DB, Annang L, Spencer SM, Lindley LL. Health communication practices among parents and sexual minority youth. J LGBT Youth. 2014. July 3;11(3):316–35. [Google Scholar]

- [25].Gagnon JH, Simon W. Sexual Conduct: The Social Sources of Human Sexuality. Chicago, IL: Aldine; 1973. [Google Scholar]

- [26].Frith H, Kitzinger C. Reformulating sexual script theory: Developing a discursive psychology of sexual negotiation. Theory & Psychology. 2001. April;11(2):209–32. [Google Scholar]

- [27].Rostosky SS, Travis CB. Menopause and sexuality: Ageism and sexism unite. In: Travis CB, White JB, eds. Sexuality, Society, and Feminism. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association; 2000:181–209. [Google Scholar]

- [28].Dotson-Blake KP, Knox D, Zusman ME. Exploring social sexual scripts related to oral sex: A profile of college student perceptions. Professional Counselor. 2012;2(1):1. [Google Scholar]

- [29].Wiederman MW. The gendered nature of sexual scripts. The Family Journal. 2005. October;13(4):496–502. [Google Scholar]

- [30].Nelson KM, Pantalone D, Carey M Sexual health education for adolescent males who are interested in sex with males: An investigation of experiences, preferences, and needs. J of Adol Health 64.1 (2019): 36–42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Feinstein BA, Thomann M, Coventry R, Macapagal K, Mustanski B, Newcomb ME. Gay and bisexual adolescent boys’ perspectives on parent-adolescent relationships and parenting practices related to teen sex and dating. Arch Sex Behav. 2018. August 1;47(6):1825–37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Thoma BC, Hueber DM. Parental monitoring, parent-adolescent communication about sex, and sexual risk among young men who have sex with men. AIDS Behav. 2014. August;18(8):1604–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Flores D, Docherty SL, Relf MV, et al. “It’s almost like gay sex doesn’t exist”: parent-child sex communication according to gay, bisexual, and queer male adolescents. J Adolesc Res. 2019;34(5):528–562. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Voisin DR, Bird JD, Shiu CS, & Krieger C “It’s crazy being a Black, gay youth.” Getting information about HIV prevention: A pilot study.” J of Adol 36.1 (2013): 111–119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Bouris A, Hill BJ, Fisher K, Erickson G, Schneider JA. Mother–son communication about sex and routine human immunodeficiency virus testing among younger men of color who have sex with men. J. of Adol Health, (2015). 57(5), 515–522. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Denzin NK, Lincoln YS. SAGE Handbook of Qualitative Research. 4th ed. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- [37].Flores DD, Abboud S, Barroso J. Hegemonic masculinity during parent-child sex communication with sexual minority male adolescents. Am J Sex Educ. 2019. doi: 10.1080/15546128.2019.1626312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Flores DD, McKinney R, Arscott J, et al. Obtaining waivers of parental consent: a strategy endorsed by gay, bisexual, and queer adolescent males for HIV prevention research. Nurs Outlook. 2018;66(2):138–148. doi: 10.1016/j.outlook.2017.09.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].Lang FR, Carstensen LL. Time counts: Future time perspective, goals, and social relationships. Psychol Aging. 2002. March;17(1):125–139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].Luniewski M, Reigle J, White B. Card sort: an assessment tool for the educational needs of patients with heart failure. Am J Crit Care. 1999. September 1;8(5):297. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [41].Natasi B, Berg MJ. Using ethnography to strengthen and evaluate intervention programs. In: Schensul JJ, LeCompte MD, Hess GA Jr, et al. , eds. Using Ethnographic Data: Interventions, Public Programming, and Public Policy. Walnut Creek, CA: Altamira; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- [42].Neufeld A, Harrison MJ, Rempel GR, Larocque S, Dublin S, Stewart M, Hughes K. Practical issues in using a card sort in a study of nonsupport and family caregiving. Qual Health Res. 2004. December;14(10):1418–28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [43].Rugg G, McGeorge P. The sorting techniques: a tutorial paper on card sorts, picture sorts and item sorts. Expert Systems. 1997. May;14(2):80–93. [Google Scholar]

- [44].Heisler JM. Family communication about sex: Parents and college-aged offspring recall discussion topics, satisfaction, and parental involvement. J Fam Commun. 2005. October 1;5(4):295–312. [Google Scholar]

- [45].Saunders MNK. Combining card sorts and in-depth interviews. In: Lyon F, Möllering G, Saunders MNK, eds. Handbook of Research Methods on Trust. Northampton, MA: Edward Elgar Publishing; 2012:110–120. [Google Scholar]

- [46].World Health Organization. Defining sexual health: Report of a technical consultation on sexual health 28–31 January 2002, Geneva. WHO website. Published 2006. Accessed March 21, 2019. https://www.who.int/reproductivehealth/publications/sexual_health/defining_sh/en/ [Google Scholar]

- [47].Kubicek K, Beyer WJ, Weiss G, Iverson E, Kipke MD. In the dark: Young men’s stories of sexual initiation in the absence of relevant sexual health information. Health Ed Behav. 2010. April;37(2):243–63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [48].Ryan C (2014). Generating a revolution in prevention, wellness & care for LGBT children & youth, Temple Political & Civil Rights Law Review, 23(2):331–344. [Google Scholar]

- [49].Johns MM, Liddon N, Jayne PE, Beltran O, Steiner RJ, & Morris E (2018). Systematic mapping of relationship-level protective factors and sexual health outcomes among sexual minority youth: The role of peers, parents, partners, and providers. LGBT health, 5(1), 6–32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]