Abstract

Introduction

There is limited research on difficulties with activities of daily living (I/ADLs) among older adults living alone with cognitive impairment, including differences by race/ethnicity.

Methods

For U.S. Health and Retirement Study (2000–2014) participants aged 55+ living alone with cognitive impairment (4,666 individuals; 9,091 observations), we evaluated I/ADL difficulty and help.

Results

Among 4.3 million adults aged 55+ living alone with cognitive impairment, an estimated 46% reported an I/ADL difficulty; 72% reported not receiving help with an I/ADL. Women reported more difficulty than men. Compared to white women, black women were 22% more likely to report a difficulty without help, and Latina women were 36% more likely to report a difficulty with help. Among men, racial/ethnic differences in outcomes were not significant. Patterns of difficulty without help by race/ethnicity were similar among Medicaid beneficiaries.

Discussion

Findings call for targeted efforts to support older adults living alone with cognitive impairment.

Keywords: activities of daily living, aging in place, CIND, dementia, disability, limitations, living arrangement, population-based study, service gaps

1 |. INTRODUCTION

An estimated one third of older adults with cognitive impairment in the United States live alone.1 Previous studies, primarily of non-Latino white and community or clinic-based samples, have shown that older adults with cognitive impairment who live alone are at greater risk than those living with others for adverse health outcomes, including untreated medical conditions,2–4 self-neglect,3,5,6 malnutrition,5,7 falls,5–7 and fires.8 Older adults living alone with cognitive impairment also report a high number of unmet needs in managing money, medications, and mobility5,7 as well as in basic activities of daily living (ADLs).9,10

There is limited population-level research on the characteristics of older adults living alone with cognitive impairment,11 their difficulties with instrumental or basic activities of daily living (I/ADLs), and whether they receive help. Furthermore, little is known about whether I/ADL difficulties and assistance with these difficulties differ by race and ethnicity. Among older adults in the United States, African-Americans and some Latino subgroups face a greater relative burden of dementia,12,13 late-life disability,14 and fewer resources for formal care.15–17 However, racial/ethnic differences in I/ADL difficulty—and assistance with I/ADLs—have not been evaluated among older adults living alone with cognitive impairment.

In the present study, we identified older adults living alone with probable dementia or cognitive impairment in population-level cohort data on older community-dwelling older adults in the United States. Among this sample, we evaluated the prevalence of difficulty in I/ADLs, receipt of assistance with these I/ADLs, and racial/ethnic differences in these outcomes. We hypothesized that racial and ethnic minorities living alone with cognitive impairment would have higher prevalence of I/ADL difficulty overall and would report less assistance. Finally, we evaluated whether coverage by the U.S. Medicaid program attenuated any observed differences by race/ethnicity or, alternatively, whether race/ethnic differences in outcomes were only present among those not receiving Medicaid. Given that Medicaid covers long-term services and supports (eg, home care aides, adult day health centers) for individuals who meet financial and functional eligibility criteria,18 we hypothesized that any differences in help with I/ADL difficulties by race/ethnicity would be diminished among Medicaid recipients.

2 |. METHODS

2.1 |. Sample

We used data from the Health and Retirement Survey (HRS), a biennial panel survey of older adults in U.S. households refreshed every 6 years to be nationally representative of the population aged 50 and over. Because pooled panel analysis of ages 55 and over are consistently representative, we focused on respondents 55 years and older. Interviews included brief cognitive assessments and proxy reports of cognition that allowed respondents to be classified as cognitively normal; having probable cognitive impairment, no dementia (CIND); or probable dementia.19 We used an established algorithm (detailed below) to identify individuals with either probable CIND or probable dementia and identified those who lived alone using the household roster from the RAND version of the HRS data.20 We pooled data for eight waves from 2000 to 2014 to improve sample size and capacity to evaluate racial/ethnic patterns.

Of the 9418 person-wave observations of respondents living alone with dementia/CIND in any wave between 2000 and 2014, we dropped 301 because the respondent was under age 55, 3 because they had incomplete information on race or Hispanic identification, and 24 because they included no data on I/ADL outcomes. Our final analysis sample included 4666 unique individuals who provided 9091 observations across repeated waves; 792 (8.7%) observations corresponded to interviews for which proxy informants responded to the questionnaire. This analyses study used version 3 of the RAND HRS longitudinal file 2014, the RAND Family Data 2014 v.1, and the current versions of the RAND HRS Fat Files from 2000 to 2014, downloaded from the HRS public website.

2.2 |. Outcome measures

We measured self- and proxy-reported difficulty in six basic ADLs and five lADLs. The six basic ADLs included dressing, walking across a room, bathing, eating, getting in and out of bed, and toileting. The five lADLs included preparing a hot meal, shopping for groceries, making phone calls, taking medications, and managing money. We defined difficulty according to standard methodologies,20 with a modification to capture otherwise unrecorded IADL difficulty when help is reported. We additionally constructed indices of difficulty without help and difficulty with help for each activity using the associated follow-up questions (see the supporting information Appendix).

These methods produced 11 binary indicators of difficulty for each of the I/ADLs, another 11 indicators of difficulty without help for each of these I/ADLs, and 11 indicators of difficulty with help for these same I/ADLs. We summed indicators across I/ADLs into three measures of the count of I/ADLs (a) overall, (b) with help, and (c) without help. We used these count variables to create binary indicators of having any difficulty (ie, between 1 and 11 I/ADLs vs 0 I/ADLs), any difficulty without help (ie, between 1 and 11 I/ADLs without help vs 0 I/ADLs without help), and any difficulty with help (ie, between 1 and 11 I/ADLs with help vs 0 I/ADLs with help).

2.3 |. Assessment of probable cognitive impairment

Probable dementia/CIND was classified with an algorithm that used respondents’ performance scores on a version of the Telephone Interview for Cognitive Status (TICS) and proxy-reported information on cognitive impairment and functional limitations.19 The TICS-M-27 sums scores from immediate and delayed word recall (0 to 20), backward counting from 20 (0 to 2), and serial subtraction of up to five 7’s from 100 (0 to 5; total range: 0 to 27). The proxy impairment index equaled the sum of the proxy’s assessment on a five-point Likert scale of the respondent’s memory (0 to 4, from excellent at 0 to poor at 4), the proxy’s assessment of whether cognitive impairments would have precluded an interview (scored between 0 and 2, where 0 corresponded to “no reason to think respondent has any cognitive limitations” and 2 corresponded to “respondent has cognitive limitations that prevent” interview), and the sum of any difficulty on five lADLs (preparing a hot meal, shopping for groceries, making phone calls, taking medications, and managing money).

Respondents were classified as having probable dementia if they scored ≤6 on the TICS or if the proxy interview cognitive impairment index was 6 or more; as having CIND if between 7 and 11 on the TICS or between 3 and 5 on the proxy index; as normal range if between 12 and 27 on the TICS or 0 to 2 on the proxy index. Because our primary outcomes include I/ADL difficulty, we explored whether IADLs in the proxy index for cognitive impairment produced a mechanical correlation between cognitive impairment and I/ADL difficulty. About 1% of respondents with likely dementia or CIND were so classified because of I/ADL difficulty alone. Our estimates remained consistent in sensitivity analyses that excluded this group.

This algorithm was previously validated with the Aging, Demographics and Memory study (ADAMS) data using diagnoses based on the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-III-R, DSM-IV), and a consensus panel in case of discrepancies19,21 and has been shown to have good validity at a population level.22 We used the longitudinal dataset containing these indexes and categorizations provided by Langa et al.23

2.4 |. Covariates

We report descriptive characteristics of the sample across the following sociodemographic covariates: education (in years), wealth (in inflation-adjusted 2014 USD), home ownership (yes/no), current Medicaid coverage (yes/no), the presence of adult children living closer or farther than 16 km from the respondent, marital status (currently married, divorced, widowed, never married).

Primary covariates in our analytic models were age and survey wave. Models were stratified by sex and self-reported race and ethnicity. We constructed four non-overlapping race/ethnicity groups: non-Hispanic white (“white”), non-Hispanic black (“black” or “African-American”), Hispanic or Latino, and other. In ancillary analyses, we evaluated outcomes for those with current Medicaid coverage.

2.5 |. Statistical analyses

We compared demographic characteristics of older adults living alone with probable dementia and CIND to those whose scores suggested normal cognition. Among those with dementia/CIND, we then estimated the age-adjusted prevalence of I/ADL difficulty, difficulty without help, and difficulty with help in the pooled cohort data stratified by race/ethnicity and sex. We applied respondents’ wave-specific weights to pooled estimates of sample means.

To test whether outcomes were significantly different by race/ethnicity, we specified generalized estimating equations (GEE) with a binomial distribution, log link function, and an unstructured covariance matrix to account for repeated observations of individuals. In our baseline GEE specification, we calculated each individual’s average weight across all observed waves and used that average for each observation (see supporting information Appendix). We first estimated these models without adjustment and then adjusted by age and HRS wave. We evaluated whether Medicaid coverage modified any racial/ethnic differences in difficulty without help with a multiplicative interaction term between the binary Medicaid coverage indicator and race/ethnicity. Finally, we evaluated differences in difficulty overall and with and without help by sex and race/ethnicity across specific I/ADLs.

All analyses were carried out in STATA v.14.

3 |. RESULTS

3.1 |. Background characteristics

Estimates from the pooled sample of eight biennial waves (2000 to 2014) suggested that approximately 1 million older individuals were living alone with probable dementia in U.S. communities in any given year during this time period, two thirds of whom were female. Another 3.3 million were living alone with probable CIND, with a similar sex composition (an estimated 2.9 million women and 1.4 million men; Table 1).

TABLE 1.

Descriptive characteristics of adults aged 55+ living alone, by cognitive status

| Women |

Men |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dementia or CIND | Normalcognition | Dementia or CIND | Normalcognition | |

| Study participants (unweighted) | 6,295 | 16,500 | 2,796 | 6,176 |

| Population estimates (weighted) | 22,824,901 | 71,452,822 | 11,570,835 | 33,589,686 |

| Population estimates (weighted, average) | 2,853,113 | 8,931,603 | 1,446,354 | 4,198,711 |

| Age (y) | 78.25 (11.54) | 70.62 (10.05) | 72.52(11.57) | 66.93 (8.44) |

| White (%) | 69.8 | 85.5 | 65.5 | 83.8 |

| Black (%) | 17.6 | 8.5 | 23.2 | 9.6 |

| Hispanic (%) | 10.1 | 3.9 | 8.2 | 4.8 |

| Other (%) | 2.5 | 2.1 | 3.1 | 1.8 |

| Education (y) | 10.68 (3.73) | 13.09 (2.51) | 10.62 (3.78) | 13.51 (2.41) |

| Financial wealth (2014$) | $83,573 ($311,219) | $177,110 ($522,414) | $98,119 ($541,159) | $317,043 ($3,055,475) |

| Owns home (%) | 55.2 | 71.2 | 54.8 | 69.1 |

| Medicaid (%) | 22.5 | 7.9 | 21.1 | 6.7 |

| Children ≤16 km | 0.95 (1.28) | 0.77 (1.05) | 0.79 (1.20) | 0.55 (0.85) |

| Children >16 km | 1.82 (2.06) | 1.66(1.66) | 1.78 (2.08) | 1.49 (1.49) |

| Married (%) | 1.1 | 1.7 | 2.6 | 4.3 |

| Divorced (%) | 20.6 | 33.4 | 38.3 | 48.9 |

| Widowed (%) | 71.5 | 54.2 | 41.0 | 25.0 |

| Never married (%) | 6.8 | 10.7 | 18.1 | 21.8 |

Notes: Statistics are reported asmean(standard deviation) for age, education, financialwealth, and children; and as percentage for other variables.Underlying data are pooled observations of respondents living alone in the 2000 to 2014 waves of the Health and Retirement Study. All statistics are estimated using wave-specific sample weights.

Abbreviation: CIND, cognitive impairment, no dementia

Compared to older adults living alone without dementia/CIND, those living alone with probable dementia/CIND were older; disproportionately black or Latino/a; and averaged lower education, lower wealth, lower home ownership rates, and higher use of Medicaid (Table 1).

In unadjusted analyses, rates of any I/ADL difficulty (40% to 50%), any difficulty without help (30%), and any difficulty with help (30%) were each twice as high or higher among older adults living alone with cognitive impairment as they were among their cognitively normal counterparts (Table S1 in supporting information).

3.2 |. Differences in I/ADL difficulty overall, with, and without help

About 50% of women and 40% of men living alone with dementia/CIND reported at least one I/ADL difficulty; 33% of women and 30% of men reported at least one difficulty without help; and 33% of women and 20% of men reported at least one difficulty with help (Table 2, bottom row in panel A [women] and panel C [men], averages by race/ethnicity groups shown in the columns).

TABLE 2.

Prevalence of I/ADL difficulty and help among those living alone with dementia or CIND by race and ethnicity and byMedicaid usage

| Panel A: all women |

White (n = 3,786) |

Black (n = 1,603) |

Hispanic (n = 763) |

||||||

| Any difficulty (%) | Any difficulty without help (%) | Any difficulty with help (%) | Any difficulty (%) | Any difficulty without help (%) | Any difficulty with help (%) | Any difficulty (%) | Any difficulty without help (%) | Any difficulty with help (%) | |

| 6 ADLs | 35.9 | 27.5 | 16.0 | 40.3 | 33.5 | 17.3 | 44.4 | 32.0 | 24.4 |

| 5 lADLs | 37.1 | 12.9 | 31.6 | 36.2 | 13.2 | 28.9 | 41.4 | 11.8 | 35.9 |

| 11 l/ADLs | 48.4 | 33.2 | 34.2 | 50.1 | 38.8 | 32.5 | 53.7 | 36.4 | 39.4 |

| Panel B: women covered by Medicaid |

White (n = 521) |

Black (n = 526) |

Hispanic (n = 405) |

||||||

| Any difficulty (%) | Any difficulty without help (%) | Any difficulty with help (%) | Any difficulty (%) | Any difficulty without help (%) | Any difficulty with help (%) | Any difficulty (%) | Any difficulty without help (%) | Any difficulty with help (%) | |

| 6 ADLs | 47.7 | 34.8 | 24.5 | 53.1 | 39.8 | 29.4 | 53.5 | 37.2 | 32.0 |

| 5 lADLs | 48.8 | 15.6 | 41.0 | 46.7 | 16.5 | 39.4 | 48.9 | 13.9 | 42.1 |

| 11 l/ADLs | 60.9 | 39.7 | 45.7 | 62.4 | 46.3 | 45.6 | 63.5 | 43.6 | 46.0 |

| Panel C: Allmen |

White (n = 1,621) |

Black (n = 856) |

Hispanic (n = 249) |

||||||

| Any difficulty (%) | Any difficulty without help (%) | Any difficulty with help (%) | Any difficulty (%) | Any difficulty without help (%) | Any difficulty with help (%) | Any difficulty (%) | Any difficulty without help (%) | Any difficulty with help (%) | |

| 6 ADLs | 29.8 | 25.4 | 9.6 | 27.2 | 24.7 | 7.6 | 30.1 | 25.8 | 9.0 |

| 5 lADLs | 28.5 | 11.9 | 22.1 | 25.5 | 10.7 | 17.3 | 27.8 | 16.4 | 15.2 |

| 11 l/ADLs | 41.4 | 31.3 | 24.2 | 37.8 | 30.7 | 18.7 | 39.4 | 30.5 | 18.7 |

| Panel D: Men covered by Medicaid |

White (n = 212) |

Black (n = 225) |

Hispanic (n = 97) |

||||||

| Any difficulty (%) | Any difficulty without help (%) | Any difficulty with help (%) | Any difficulty (%) | Any difficulty without help (%) | Any difficulty with help (%) | Any difficulty (%) | Any difficulty without help (%) | Any difficulty with help (%) | |

| 6 ADLs | 37.8 | 33.1 | 14.4 | 33.5 | 30.0 | 10.6 | 32.7 | 29.5 | 9.0 |

| 5 lADLs | 38.3 | 19.0 | 32.5 | 34.0 | 13.9 | 21.9 | 32.7 | 18.0 | 21.0 |

| 11 l/ADLs | 51.8 | 43.1 | 33.2 | 48.6 | 39.1 | 23.8 | 46.4 | 36.1 | 26.6 |

Notes: Statistics are reported as percentages for all variables. Underlying data are pooled observations of respondents living alone with probable dementia or CIND observed in the 2000 to 2014 waves of the Health and Retirement Study. Medicaid coverage is defined as self-reported current coverage.Difficultywith orwithout help is expressed here as a percentage of all individuals, bothwith and without any difficulty. All statistics are estimated using wave-specific sample weights.

Abbreviations: ADL, activities of daily living; CIND, cognitive impairment, no dementia; I/ADL, instrumental activities of daily living

Among men and women in the sample, non-Latino white respondents living alone with cognitive impairment were on average 5 to 7 years older than their racial/ethnic minority counterparts (Table 1). After adjusting for age and survey wave, the risk of any I/ADL difficulty among black women (Table 3, panel A, prevalence ratio [PR]: 1.13, 95% confidence interval [CI]: 1.03, 1.23) and also among Latina women (PR: 1.21, 95% CI: 1.08, 1.35) was higher than for non-Latina white women.

TABLE 3.

Generalized estimating equation models of any I/ADL difficulty, difficulty without help, and difficulty without help among individuals living alone with CIND or dementia

| Panel A: women |

White (n = 3786) Prevalence (%) |

Black (n = 1603) Prevalence ratio [95% CI] |

Hispanic (n = 763) Prevalence ratio [95% CI] |

| Any I/ADL difficulty | 48.1 | 1.13 [1.03,1.23]** | 1.21 [1.08,1.35]** |

| Any I/ADL difficulty without help | 33.0 | 1.22 [1.09,1.37]** | 1.08 [0.92,1.28] |

| Any I/ADL difficulty with help | 33.9 | 1.09 [0.97,1.24] | 1.36 [1.18,1.57]** |

| Panel B:Men | White (n = 1621) | Black (n = 856) | Hispanic (n = 249) |

| Prevalence (%) | Prevalence ratio [95% CI] | Prevalence ratio [95% CI] | |

| Any I/ADL difficulty | 41.3 | 1.03 [0.88,1.21] | 1.00 [0.78,1.28] |

| Any I/ADL difficulty without help | 31.3 | 1.07 [0.89,1.28] | 1.05 [0.78,1.41] |

| Any I/ADL difficulty with help | 24.1 | 0.96 [0.75,1.24] | 0.89 [0.62,1.27] |

Notes: Underlying data are pooled observations of respondents living alone with probable dementia or CIND observed in the 2000 to 2014 waves of the Health and Retirement Study. This universe includes respondents who reported no I/ADL difficulty, who could not have difficultywith orwithout help by definition. Each row displays results from a separatemodel. The first column shows the prevalence of any ADL or IADL difficulty (with help,without help) among the baseline group, non-Hispanic whites. The other columns display risk ratios and their 95% confidence intervals from a generalized estimating equation (“xtgee”) configured to the binomial distribution, log link function, and unstructured within-group correlation. Covariates include race/ethnicity, 10-year age categorical variables, and HRS wave indicator variables. Sample weights are set equal to the respondent’s average weight in the sample. Asterisks denote statistical significance at the 5%(*) and 1%(**) levels.

Abbreviations: ADL, activities of daily living; CI, confidence interval; CIND, cognitive impairment, no dementia; I/ADL, instrumental activities of daily living

Black women living alone with probable dementia/CIND were at greater risk (PR: 1.22, 95% CI: 1.09, 1.37) of reporting at least one I/ADL difficulty without help than their white counterparts, but the risk was not significantly different for Latina compared to non-Latina white women. Conversely, Latina women had a higher risk than white women of reporting a difficulty with help (PR: 1.36, 95% CI: 1.18, 1.57), while there was no evidence of a different rate in reporting difficulty with help among black compared to white women. Results were qualitatively similar in models that restricted the analytic sample to respondents who reported at least one I/ADL difficulty (Table S3 in supporting information). Among men, there was no evidence of significant differences in I/ADL difficulty with or without help by race/ethnicity, and prevalence ratios hovered near unity.

In the analytic sample, 3% reported Medicaid coverage only, 67% of respondents reported Medicare coverage only, and 20% were dualeligible (Table S4 in supporting information). Compared to the overall sample, these rates of Medicaid coverage were relatively high (see supporting information Appendix). For both women (Table 2, panel B) and men (Table 2, panel D) reporting being on Medicaid, the proportions of individuals with any difficulty, with any difficulty without help, and with any difficulty with help were higher than in the overall samples of women and men living alone with dementia/CIND. This was true across all race/ethnic groups.

While Medicaid was associated with higher rates of I/ADL difficulty, as would be expected given Medicaid eligibility criteria, there was no evidence that being on Medicaid modified the association between race/ethnicity and I/ADL difficulty (overall, with help, or without help), as evidenced by the non-significant multiplicative interaction terms between Medicaid status and race/ethnicity variables in Table S5 in supporting information. For example, the magnitude of difference in the prevalence of I/ADL difficulty help for black versus non-Latina white women was the same in Medicaid versus non-Medicaid recipients. Similarly, the absence of significant differences in difficulty without help for Latina versus non-Latina white women and among men overall remained consistent for both Medicaid and non-Medicaid beneficiaries (see also Figure S1 in supporting information).

3.3 |. Difficulty and help received with specific I/ADLs

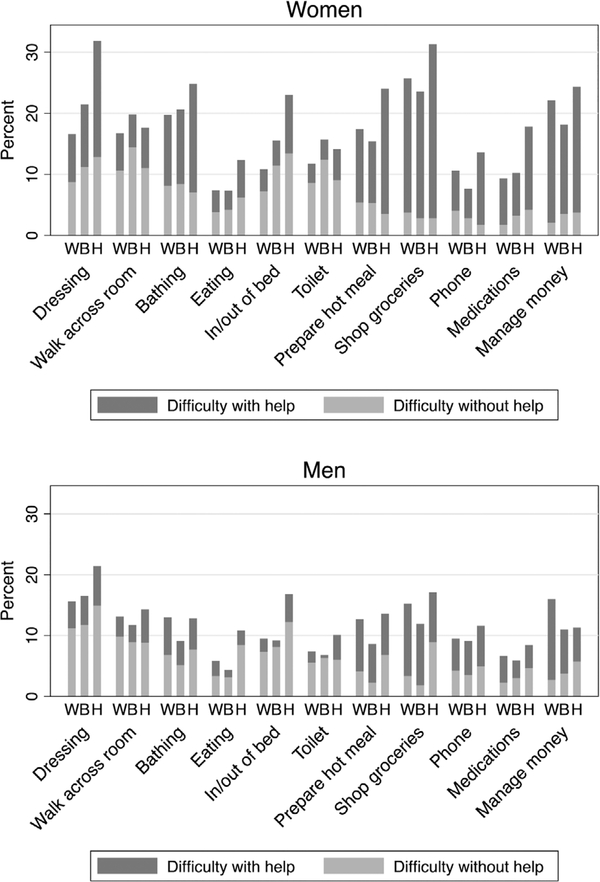

Compared to men, women reported higher prevalence of any difficulty across most specific I/ADLs (combined heights of light and dark bars in Figure 1), and also higher rates of any difficulty without help (light bars) and of any difficulty with help (dark bars). Among women, there were racial/ethnic differences in rates of difficulty for select individual I/ADLs. Most notably, unadjusted rates of difficulty with dressing and getting in or out of bed among Latina women were twice those observed among non-Latina whites. Rates of difficulty with and without help among these specific activities were also elevated for Latina compared to non-Latina whites.

FIGURE1.

Instrumental activities of daily living difficulty by help received, sex, and race/ethnicity among individuals living alone with cognitive impairment, no dementia (CIND) or dementia NOTE: See notes to Table 3 and Table S2 in supporting information. Rates of any difficulty in the activity equal the combined height of the dark (any difficulty with help) plus light (any difficulty without help) rectangles.

4 |. DISCUSSION

In a population-based cohort that was nationally representative of community-dwelling older adults in the United States between 2000 and 2014, we estimated that about 4.3 million older individuals were living alone with probable dementia or CIND at any given time. Half of older adults living alone with dementia/CIND reported any difficulty with at least one I/ADL, one third reported at least one I/ADL difficulty without help, and one third reported at least one I/ADL difficulty with help. Among those reporting at least one I/ADL difficulty, 72% reported at least one difficulty without help, and 66% reported at least one difficulty with help.

This is one of few population-based studies of I/ADL difficulty in outcomes for older adults in the United States living alone with cognitive impairment. It is the first, to our knowledge, that has evaluated differences in I/ADL difficulty with and without help by race/ethnicity. Amjad et al.1 evaluated the prevalence of living alone among individuals with cognitive impairment, and Gibson et al.11 evaluated characteristics among older adults living alone with cognitive impairment, including patterns of formal and informal assistance, both using population-based data that was representative of Medicare recipients. Neither study examined differences by race/ethnicity or evaluated potential modifiers of these differences.

Among older adults living alone with probable dementia/CIND, we estimated a higher prevalence of any I/ADL difficulty among women than men, and there was heterogeneity in difficulty across specific I/ADLs and across race/ethnicity. We found elevated age-adjusted rates of any I/ADL difficulty among both black and Latina women compared to whites. Black women were also around 20% more likely to report a difficulty without help than comparable white women, while Latina women were about 33% more likely than white women to report a difficulty with help. These results imply that minority women had a higher prevalence of I/ADL difficulty than comparable white women, but the nature of the inequality differed. Black women had more disability than white women and—to the extent that difficulty without help reflects precarity24–28 as well as some degree of unmet need for assistance with I/ADLs— black women were also more likely to be in this state of heightened precarity and possibly living with unmet needs for care. For Latinas, the results suggested elevated rates of disability relative to whites. However, their comparatively similar rates of difficulty without help may suggest that Latinas did not necessarily experience precarity and/or unmet need at a higher rate than their non-Latina white counterparts.

We expected that any observed differences in I/ADL difficulties and receipt of assistance by race/ethnicity would be diminished among Medicaid beneficiaries, given that Medicaid provides formal long-term services and supports to eligible old adults. We found no support for this; there was no evidence that racial/ethnic differences in rates of difficulty without help were either exacerbated or attenuated by Medicaid coverage. It is possible that Medicaid might have affected the nature of help received, for example extending paid formal care to poorer elderly who would otherwise use informal care or the number of hours of care received. Future analyses could explore these dynamics using linkages between the HRS and Medicaid administrative data on long-term services and supports.

Although we found a high prevalence of any I/ADL difficulty among the entire analytic sample of older adults living alone with probable dementia/CIND, the true percentages could be higher. Qualitative studies28–30 have found that respondents sometimes understate needs to avoid unwanted relocations. Further, cognitive impairment might reduce respondents’ ability to assess their own capacity to perform specific I/ADLs. This discrepancy was also observed in an ongoing qualitative study of older adults living alone with dementia.28,30–32 To our knowledge, the extent of these two types of potential measurement error with bias in the HRS is unknown and deserving of inquiry.

Given well-documented disparities in late-life disability,14 the lack of significant racial/ethnic inequalities among men was surprising. Observed I/ADL difficulty and help received depends on whether respondents were able to remain in living in the community, which in turn depends on ability to perform daily activities. Sample attrition might have attenuated any true racial/ethnic differences among those observed alone at home. But why this might be specific to men is unclear. Alternatively, varying results by gender could reflect underlying differences in the nature of living alone with cognitive impairment. For example, nearly 75% of women living alone with cognitive impairment were widowed, compared with only 41.0% among men. Men living alone were much more likely never to have married (21.3% versus 9.6% per Table 1), which suggests a different dynamic may have been present.

4.1 |. Limitations

The results should be viewed in light of a number of limitations. First, there is likely substantial measurement error introduced in analyses evaluating self-reported outcomes for people with cognitive impairment. For respondents unable or deemed too impaired to participate in the survey, HRS interviewed a proxy, but proxies may not have full information about cognitive impairment, functional limitations, or help. Alternatively, proxy informants may more accurately report on respondents’ needs and receipt of help, particularly if the informant is involved with providing care. Proxy informants have been shown to provide unbiased measures of cognition33 and valid reports of functional status.34

There may also be substantial selection bias. Some capacity to perform basic ADLs is generally necessary to remain in the community, meaning that those most vulnerable in terms of I/ADL difficulty and unmet needs for help were likely not included in the sample. Future work evaluating outcomes for this population is merited.

Another limitation derives from the phrasing of questions in the HRS, which is ambiguous about the need for help. An explicit assumption is that respondents who received help must have needed it. The implicit assumption is that people who do not receive help also do not need any help and must have adopted accommodations that enabled them to complete the activity independently. But we find it plausible that some respondents who reported difficulty but no help actually needed the help but did not have access to it, whether for financial or other reasons. Given the typically progressive nature of dementia and cognitive impairment, even if respondents were able to complete I/ADLs without assistance, they will likely need assistance in the future. Finally, as with any quantitative study of vulnerable populations that are also small in size, the HRS pooled sample may underrepresent the group of older adults living alone with cognitive impairment.

5 |. CONCLUSION

Among community-dwelling older adults living alone with probable dementia or cognitive impairment, we found high rates of any I/ADL difficulty in basic and instrumental activities of daily living, and high rates of any difficulty with and without help. The prevalence of I/ADL difficulty without assistance was significantly higher for black women compared to white women, but there were no differences for Latinas versus non-Latina white women, and no race/ethnic differences in the prevalence of difficulty without help for men. Finally, Medicaid status did not modify observed differences—or lack thereof —in I/ADL difficulty without help. Future research in this area could identify resources that promote quality of life for this vulnerable population. This may include better support and connection to sources of formal and informal assistance. The high prevalence of difficulty without help suggests that the currently available long-term services and supports may not adequately ensure that older adults living alone with cognitive impairment are receiving necessary assistance with activities of daily living.

Supplementary Material

RESEARCH IN CONTEXT.

Systematic review: There is limited population-level research on the characteristics of older adults living alone with cognitive impairment, and no prior research on racial/ethnic differences in disability and help received among this subpopulation. Relevant citations are appropriately cited.

Interpretation: We compared older adults living alone with probable cognitive impairment to those living alone without impairment, and we compared blacks and Latinos to whites. Our results reveal high and highly variable levels of difficulty with ordinary and instrumental activities of daily living across sex and race/ethnicity among older U.S. adults living alone with cognitive impairment, a group that numbers about 4.3 million. We also found large variation in help with difficulties. Differences were unaffected by Medicaid coverage.

Future directions: Results motivate future work to identify resources that promote increased supports for older adults with cognitive impairment living alone.

Acknowledgments

FUNDING

This work was supported by the National Institute on Aging (R56AG062165 PI Portacolone; K01AG049102 PI Portacolone; K01AG056602 PI Torres; T32AG049663 PI Glymour/Hiatt). This work was also supported by the New Investigator Research Grant Award (NIRG 15-362325 PI Portacolone) from the Alzheimer’s Association and by the Pepper Center at UCSF (P30AG044281 PI Covinsky), which promotes promising new research aimed at better understanding and addressing late-life disability in vulnerable populations. Opinions reflect those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of the granting agencies. The funders played no role in study design; collection, analysis, or interpretation of data; writing of the article; or the decision to submit for publication.

Funding information

National Institute on Aging, Grant/Award Numbers: R56AG062165, K01AG049102, K01AG056602, T32AG049663; New Investigator Research, Grant/Award Number: NIRG 15-362325

Footnotes

SUPPORTING INFORMATION

Additional supporting information may be found online in the Supporting Information section at the end of the article.

REFERENCES

- 1.Amjad H, Roth DL, Samus QM, Yasar S, Wolff JL. Potentially unsafe activities and living conditions of older adults with dementia. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2016;64(6):1223–1232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cermakova P, Nelson M, Secnik J, et al. Living alone with Alzheimer’s disease: data from SveDem, the Swedish Dementia Registry. J Alzheimers Dis. 2017;58(4):1265–1272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Meaney AM, Croke M, Kirby M. Needs assessment in dementia. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2005;20(4):322–329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Schneider J, Hallam A, Murray J, et al. Formal and informal care for people with dementia: factors associated with service receipt. Aging Ment Health. 2002;6(3):255–265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Miranda-Castillo C, Woods B, Orrell M. People with dementia living alone: what are their needs and what kind of support are they receiving? Int Psychogeriatr. 2010;22(4):607–617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tierney MC, Snow WG, Charles J, Moineddin R, Kiss A. Neuropsychological predictors of self-neglect in cognitively impaired older people who live alone. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2007;15(2):140–148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tuokko H, MacCourt P, Heath Y. Home alone with dementia. Aging Ment Health. 1999;3(1):21–27. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Elder AT, Squires T, Busuttil A. Fire fatalities in elderly people. Age Ageing. 1996;25(3):214–216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Edwards DMJ. Alone and confused: community-residing older African Americans with dementia. Dementia. 2007;6:489–506. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Webber PA, Fox P, Burnette D. Living alone with Alzheimer’s disease: effects on health and social service utilization patterns. Gerontologist. 1994;34(1):8–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gibson AK, Richardson VE. Living alone with cognitive impairment. Am J Alzheimers Dis Other Demen. 2017;32(1):56–62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mayeda ER, Glymour MM, Quesenberry CP, Whitmer RA. Inequalities in dementia incidence between six racial and ethnic groups over 14 years. Alzheimers Dement. 2016;12(3):216–224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chen C, Zissimopoulos JM.Racial and ethnic differences in trends in dementia prevalence and risk factors in the United States. Alzheimers Dement (N Y). 2018;4:510–520. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Schoeni RF, Martin LG, Andreski PM, Freedman VA. Persistent and growing socioeconomic disparities in disability among the elderly: 1982–2002. Am J Public Health. 2005;95(11):2065–2070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Smedley BD, Stith AY, Nelson AR, editors. Institute of Medicine (US) Committee on Understanding and Eliminating Racial and Ethnic Disparities in Health Care. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2003. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bowen ME, Gonzalez HM. Racial/ethnic differences in the relationship between the use of health care services and functional disability: the health and retirement study (1992–2004). Gerontologist. 2008;48(5):659–667. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Martin LG, Zimmer Z, Lee J. Foundations of activity of daily living trajectories of older Americans. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci. 2017;72(1):129–139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Colello KJ. Medicaid financial eligibility for long term services and supports CRS Report RA3506. 2017. Washington, D.C.: Congressional Research Service; Available at: http://govbudget.com/wpcontent/uploads/2018/10/Medicaid-Financial-Eligibility-for-Long-Term-Services-and-Supports.pdf. Accessed: August 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Crimmins EM, Kim JK, Langa KM, Weir DR. Assessment of cognition using surveys and neuropsychological assessment: the Health and Retirement Study and the Aging, Demographics, and Memory Study. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci. 2011;66(suppl):i162–i171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bugliari D CN, Chan C, Hayden O, et al. RAND HRS Longitudinal File 2014 (V2) Documentation. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan’s Institute for Social Research; 2018. http://hrsonline.isr.umich.edu/data/index.html. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Plassman BL, Langa KM, Fisher GG, et al. Prevalence of dementia in the United States: the aging, demographics, and memory study. Neuroepidemiology. 2007;29(1–2):125–132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gianattasio KZ, Wu Q, Glymour MM, Power MC. Comparison of methods for algorithmic classification of dementia status in the health and retirement study. Epidemiology. 2019;30(2):291–302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Langa KM, Weir DW, Kabeto M, Sonnega A. Langa-Weir Classification Of Cognitive Function (1995 onward). Ann Arbor: University of Michigan’s Institute for Social Research; 2018. http://hrsonline.isr.umich.edu/modules/meta/researcher-contributions/langa-weir-classifications/Data_Description_Langa_Weir_Classifications.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gill TM, Robison JT, Tinetti ME. Difficulty and dependence: two components of the disability continuum among community-living older persons. Ann Intern Med. 1998;128(2):96–101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Reuben DB.Warning signs along the road to functional dependency. Ann Intern Med. 1998;128(2):138–139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Grenier A, Lloyd L, Phillipson C. Precarity in late life: rethinking dementia as a ‘frailed’ old age. Sociol Health Illn. 2017;39(2): 318–330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Grenier A, Phillipson C & Settersten RA (Eds.). Precarity and Ageing: Understanding Insecurity and Risk in Later Life. (2020). Bristol, UK: Policy Press. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Portacolone E, Rubinstein RL, Covinsky KE, Halpern J, Johnson JK. The Precarity of Older Adults Living Alone With Cognitive Impairment. Gerontologist. 2019;59(2):271–280. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Portacolone E, Covinsky KE, Johnson JK, Rubinstein RL & Halpern J. Expectations and concerns of older adults with cognitive impairment about their relationship with medical providers: a call for therapeutic alliances. Qual Health Res. (In Press). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Portacolone E, Johnson JK, Covinsky KE, Halpern J, Rubinstein RL. The effects and meanings of receiving a diagnosis of mild cognitive impairment or Alzheimer’s Disease when one lives alone. J Alzheimers Dis. 2018;61(4):1517–1529. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Portacolone E On living alone with Alzheimer’s disease. Care Wkly. 2018;2018:1–4. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Portacolone E, Covinsky KE, Johnson JK, Rubinstein RL, Halpern J. Walking the tightrope between study participant autonomy and researcher integrity: the case study of a research participant with Alzheimer’s Disease Pursuing Euthanasia in Switzerland. J Empir Res Hum Res Ethics. 2019;14(5):483–486. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Weir D, Faul J, Langa K. Proxy interviews and bias in the distribution of cognitive abilities due to non-response in longitudinal studies: a comparison of HRS and ELSA. Longit Life Course Stud. 2011;2(2):170–184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Chan KS, Kasper JD, Brandt J, Pezzin LE. Measurement equivalence in ADL and IADL difficulty across international surveys of aging: findings from the HRS, SHARE, and ELSA. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci. 2012;67(1):121–132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.