Abstract

Rationale:

The ubiquitin-proteasome system (UPS) and the autophagic-lysosomal pathway (ALP) are pivotal to proteostasis. Targeting these pathways is emerging as an attractive strategy for treating cancer. However, a significant proportion of patients who receive a proteasome inhibitor-containing regime show cardiotoxicity. Moreover, UPS and ALP defects are implicated in cardiac pathogenesis. Hence, a better understanding of the cross-talk between the two catabolic pathways will help advance cardiac pathophysiology and medicine.

Objective:

Systemic proteasome inhibition (PSMI) was shown to increase p62/SQSTM1 expression and induce myocardial macroautophagy. Here we investigate how proteasome malfunction activates cardiac ALP.

Methods and Results:

Myocardial macroautophagy, transcription factor EB (TFEB) expression and activity, and p62 expression were markedly increased in mice with either cardiomyocyte-restricted ablation of Psmc1 (an essential proteasome subunit gene) or pharmacological PSMI. In cultured cardiomyocytes, PSMI-induced increases in TFEB activation and p62 expression were blunted by pharmacological and genetic calcineurin inhibition and by siRNA-mediated Molcn1 silencing. PSMI induced remarkable increases in myocardial autophagic flux in wild type (WT) mice but not p62 null (p62-KO) mice. Bortezomib-induced left ventricular wall thickening and diastolic malfunction was exacerbated by p62 deficiency. In cultured cardiomyocytes from WT mice but not p62-KO mice, PSMI induced increases in LC3-II flux and the lysosomal removal of ubiquitinated proteins. Myocardial TFEB activation by PSMI as reflected by TFEB nuclear localization and target gene expression was strikingly less in p62-KO mice compared with WT mice.

Conclusions:

(1) The activation of cardiac macroautophagy by proteasomal malfunction is mediated by the Mocln1-calcineurin-TFEB-p62 pathway; (2) p62 unexpectedly exerts a feed-forward effect on TFEB activation by proteasome malfunction; and (3) targeting the Mcoln1-calcineurin-TFEB-p62 pathway may provide new means to intervene cardiac ALP activation during proteasome malfunction.

Keywords: TFEB, p62/SQSTM1, Mcoln1, calcineurin, proteasome inhibitor

Graphical Abstract

INTRODUCTION

The ubiquitin-proteasome system (UPS) is responsible for the degradation of the vast majority of cellular proteins, pivotal to both protein quality control and the regulatory degradation of normal proteins essential to virtually all cellular processes.1 The autophagic-lysosomal pathway (ALP) also plays a crucial role in intracellular quality control via removal of aberrant protein aggregates and defective or surplus organelles, in addition to provision of fuels by self-digesting a portion of cytoplasm during energy crisis.2 UPS and ALP were historically believed to function in parallel in the cell but emerging evidence suggests their cross-talk although the underlying molecular mechanisms remain poorly understood.3

In UPS-mediated protein degradation, the proteasome carries out the final proteolytic step of poly-ubiquitinated proteins and, as indicated by emerging evidence, its functioning is highly regulated and often constitutes the rate–limiting step.4 Studies on human myocardium with cardiomyopathies and end-stage heart failure have yielded compelling evidence that cardiac proteasome functional insufficiency (PFI) occurs in a large subset of heart disease during progression to heart failure and may play a major pathogenic role therein.5, 6 Studies using animal models have established the necessity of PFI in both rare and common forms of cardiac disorders such as cardiac proteinopathy,7 myocardial ischemia/reperfusion injury,7–9 pressure-overloaded cardiac hypertrophy and failure,10, 11 and diabetic cardiomyopathy.12 Therefore, beyond search for measures to improve cardiac proteasome functioning,13 a better understanding of how cardiomyocytes and hearts respond to proteasome impairment will help identify potential therapeutic strategies to maintain cardiac proteostasis. Prior studies have shown that pharmacological proteasome inhibition (PSMI) increases myocardial macroautophagy (hereafter referred to as autophagy);14 and both autophagy and p62/SQSTM1 in cardiomyocytes are markedly increased in the compensatory stage of cardiac proteinopathy.15, 16 The latter exemplifies heart disease with increased proteotoxic stress and is associated with PFI.15–18 However, the molecular mechanisms governing the activation of autophagy by proteasome malfunction and the role of p62 upregulation in the induction of cardiac autophagy by PSMI remain undefined.

Transcription factor EB (TFEB) is a master regulator of lysosomal genesis, ALP, and catabolism. At baseline, TFEB is phosphorylated at multiple residues by kinases including the all-important mechanistic target of rapamycin complex 1 (mTORC1) and possibly extracellular signal-regulated kinase 2 and MAP4K3.19 Phosphorylated TFEB is bound by chaperone 14-3-3 and segregated in the cytoplasm where a large fraction of, if not all, TFEB proteins are localized on the membrane of lysosomes. During starvation or lysosomal stress, mTORC1 is inactivated and stops phosphorylating TFEB while TFEB is dephosphorylated by calcineurin, allowing TFEB nuclear translocation. Here the activation of calcineurin is induced by the release of lysosomal Ca2+ via the Ca2+ channel mucolipin1 (MCOLN1).20 In the nucleus, TFEB binds to a common 10-base E box-like palindromic sequence, referred to as the coordinated lysosomal expression and regulation (CLEAR) element, and thereby activates the transcription of an entire network of genes harboring the CLEAR motif. This network is known as the CLEAR network consisting of genes involved in lysosomal genesis, autophagosome formation and even mitochondrial biogenesis.21 The role of TFEB activation in cardiac pathophysiology has begun to unveil;16, 22–25 however, it remains untested how TFEB participates in the crosstalk between the UPS and ALP, especially in bridging proteasome malfunction and autophagy activation. Hence, we performed the present study to address these critical questions.

The present study has identified that both TFEB activation and p62/Sqstm1 upregulation were induced by both genetic and pharmacological PSMI in the heart and cardiomyocytes, established that TFEB activation by PSMI is calcineurin- and Mcoln1- dependent, demonstrated that p62 is required for induction of autophagy by PSMI and for lysosomal removal of ubiquitinated proteins in cardiomyocytes with proteasome malfunction, and discovered that p62 exerts an unexpected feedforward effect on the TFEB activation by PSMI. Taken together, the present study identifies the Mcolon1-calcineurin-TFEB-p62 pathway for proteasome malfunction to induce autophagy in the heart, which yields new mechanistic insight into the crosstalk between the UPS and ALP and provides potentially new therapeutic targets for modulating cardiac proteostasis.

METHODS

A full description of Materials and Methods can be found in online supplements.

The authors declare that all supporting data are available within the article and its online supplementary files.

Animal models.

The mice harboring the Psmc1 floxed allele (Psmc1f/f),26 the αMyHC-Cre transgenic (tg) mouse [B6.FVB-Tg(Myh6-cre)2182Mds/J; also known as αMyHC-Cre],27 global p62 knockout (p62-KO) mice,28 GFPdgn tg mice,29 and the GFP-LC3 tg mice,30 were previously described. All mice were converted to C57BL/6J background before being used for this current study. All protocols for animal use and care were approved by the University of South Dakota Institutional Animal Care and Use of Committee and conform to the NIH Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals.

Neonatal rat or mouse cardiomyocyte cultures and genetic manipulations.

Statistical methods.

GraphPad Prism software (Version 8.4.1; GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA 92108) was used. All continuous variables are presented as mean ± SD unless indicated otherwise. All data were examined for normality with the Shaprio Wilk’s test prior to application of parametric statistical tests. Those that failed this test were analyzed with the Mann-Whitney test. Tests used for statistical significance evaluations of each data set are specified in figure legends. In all cases where 1-, 2-, or 3-way ANOVA was used, there was a significant overall treatment effect and Tukey’s test was performed for pairwise comparisons. A p value <0.05 is considered statistically significant, which yielded a False Discovery Rate (FDR) below 5% for any of the multiple testing in this study (Figures 5E, 6C, 6F, and 8B) as estimated with the Benjamini Hochberg method. The Holm-Sidak method was used for multiple testing correction whenever multiple t tests were used.

Figure 5. PSMI by BZM leads to dephosphorylation and nuclear translocation of TFEB in NRVMs.

NRVMs were treated with BZM (25 nM) or DMSO for 12 or 24 hours before analyses. A, Western blot analyses for TFEB (top). The stain-free total proteins (bottom) on the PVDF membrane were used as loading control. B and C, NRVMs were treated with DSMO or BZM for 12 hours (B) and 24 hours (C), respectively, and subjected to cytosolic and nuclear fractionation, followed by western blot analyses. GAPDH and Histone H3 (H3) were probed as a cytoplasmic and nuclear protein marker, respectively. N = 3 biological repeats/group. D, NRVMs were treated with DMSO or BZM (25 nM) for 12 hours and immunostaind for TFEB (green). The nuclei and F-actin were counterstained with DAPI (blue) and Phalloidin (red), respectively. Representative fluorescence confocal micrographs are shown. Scale bar = 40 μm. E, NRVMs were transfected with siLuci (circle) or siRNA against rat TFEB (siTFEB; triangle) for 48 hours, followed by treatment with BZM (25 nM; red) or vehicle (yellow) for additional 24 hours. Shown are mRNA levels of the indicated genes assessed by qPCR from 3 biological repeats of each group. P values are derived from two way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s test and are all statistically significant after correction for 6 testings (6 genes) with the Benjamini Hochberg procedure.

Figure 6. TFEB activation by PSMI in NRVMs is calcineurin- and Mcoln1-dependent.

A and B, NRVMs were treated with cyclosporine A (CsA; 1.5 μM; solid circle) or vehicle control (open circle) for 4 hours and subsequently with BZM (25 nM) for additional 12 hours. Western blot analyses for TFEB in the cytosolic and nuclear fractions (A) and the densitometry data (B). GAPDH and histone H3 (H3) were probed as a cytoplasmic and nuclear protein marker, respectively. C, Knockdown of calcineurin (Cn) Aβ with specific siRNA (siCnAβ) significantly attenuated the activation of TFEB target genes by proteasome inhibition with BZM. NRVMs were transfected with siCnAβ (triangle) or siLuci (circle) for 48 hours and then treated with bortezomib (BZM, 25 nM; solid symbols) or vehicle control (open symbol) for additional 24 hours. The transcripts of the indicated genes were assessed with qPCR. D-F, NRVMs were transfected with siRNAs specific for Mcoln1 (si-Mcoln1) or for luciferase (si-Luc) for 72 hours and treated with BZM (25 nM) for additional 12 hours. The cells were subjected to subcellular protein fractionation or for total RNA extraction. D and E, Western blot analyses for TFEB in the cytosolic and nuclear fractions (D) and the densitometry data (E). F, qPCR analyses for the indicated TFEB target genes. The p values shown are from two-sided and unpaired t test (B, E) or two way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s tests (C, F). All the p values smaller 0.05 in C and F remain statistically significant after correction for multiple-testing (6 genes in parallel) using the Benjamini Hochberg procedure.

Figure 8. Ablation of p62 (p62KO) attenuates myocardial TFEB activation by PSMI in mice.

WT and p62KO mice were treated with MG262 or vehicle control as described in Figure 7A. Ventricular myocardium was collected for the analyses. A, Confocal micrographs of immunofluorescence staining for TFEB (green) and counter-staining with DAPI (blue) for nuclei and with Phalloidin (red) for F-actin. Bar = 40 μm. B, qPCR analyses for the indicated target genes of TFEB. Shown p values are derived from two way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s test and are all statistically significant after correction for multiple-testing (5 genes) with the Holm-Sidak method. C, An overall model for proteasome malfunction to activate autophagy through the Mcoln1-calcineurin-TFEB-p62 pathway. Proteasome malfunction accumulates and activates calcineurin, which in turn dephosphorylates and activates TFEB; the activation of TFEB increases the expression of Mcoln1, p62 and other genes of the CLEAR network and thereby increases autophagy. Mcoln1 and p62 in turn exert a feed-forward effect on TFEB activation; p62 does so potentially through sequestration of mTORC1 into the aggregates of ubiquitinated proteins and thereby preventing mTORC1 from phosphorylating TFEB. Meanwhile, p62 recruits and condenses ubiquitinated proteins for autophagic degradation. PSMI, proteasome inhibition; CnA, calcineurin; Psmc1KO, cardiomyocyte-restricted knockout of Psmc1; Ub. pro., ubiquitinated proteins.

RESULTS

Increases in myocardial p62, LC3-II, and autophagosomes in Psmc1CKO mice.

To date, the impact of cardiac proteasome malfunction on autophagy has not been examined in a genetic model of PSMI. PSMC1/Rpt2 is an AAA-ATPase subunit of the 19S proteasome and is required for the assembly and functioning of 26S proteasomes.26, 31 Using the Cre-Loxp system, we achieved perinatal cardiomyocyte-restricted knockout of the Psmc1 gene (Psmc1CKO; Supplementary Figure I). Comparing the homozygous Psmc1CKO (αMyHC-Cre+::Psmc1f/f) mice with littermate control mice (CTL) consisting of αMyHC-Cre+, Psmc1f/+, Psmc1f/f, and heterozygous Psmc1CKO (αMyHC-Cre+::PSMC1f/+) mice, we confirmed the deletion of the Psmc1 gene in cardiomyocytes, resulting in ~85% reduction of myocardial Psmc1 proteins and the loss of nuclear-enriched Psmc1 staining in cardiomyocytes, but not in non-cardiomyocyte cells (Supplementary Figure IB–D). As expected,26 Psmc1CKO caused substantial accumulation of myocardial ubiquitinated proteins and, when coupled with a UPS surrogate substrate GFPdgn,29 increased myocardial GFPdgn protein levels (Figure 1A–1C). Thus, we have created a genetic model of cardiomyocyte-restricted PSMI.

Figure 1. Psmc1CKO increased myocardial p62, LC3-II, and autophagosomes in mice.

A, Western blot analyses for the indicated proteins in the hearts of CTL (yellow circle; n=5) and Psmc1CKO (red circle; n=6) mice at postnatal day 2 (P2). Ub, ubiquitin conjugates. B and C, GFPdgn transgene was introduced into CTL (n=3) and Psmc1CKO (n=5) mice. Myocardial GFPdgn protein levels in indicated P2 mice were assessed by western blot (B) and quantified (C). D, Immunostaining of ubiquitin (green) and p62 (red) in myocardium sections from P2 mice. Arrowheads mark cardiomyocytes with increased ubiquitinated proteins and p62. Nuclei were counter-stained with DAPI (blue). Bar, 10 μm. E and F, Western blots (E) of myocardial LC3 (n=4 mice for CTL and 3 for Psmc1CKO) and p62 (n=4 mice for CTL and 4 for Psmc1CKO) at P2 and the quantification (F). G and H, GFP-LC3 transgene was crossed into CTL and Psmc1CKO (KO) mice to label autophagosome (green puncta). Shown are confocal fluorescent images (G) of myocardium sections from P2 mice and the quantification of GFP-positive puncta (H) where 4 CTL and 3 KO mice were used and 2 technical repeats per mouse were included. Bar, 10 μm. The precise p values are shown immediately above the pairwise comparison bracket (the same for all figures) and they are from two-sided and unpaired t test (C, F), or nested t-tests (H).

We then probed the impact of genetic PSMI on the ALP. Loss of Psmc1 led to ~1.6-fold upregulation of myocardial LC3-II (an autophagosome marker) and ~3.3-fold of increase in p62/Sqstm1, compared with the CTL (Figure 1E, 1F). p62 is a prototype autophagic receptor that shuttles ubiquitinated proteins to autophagosomes for degradation.32 We found the increased p62 frequently co-localized with ubiquitin-positive aggregates in Psmc1CKO hearts (Figure 1D). To visualize the abundance of autophagosomes, we cross-bred a GFP-LC3 transgene into CTL and Psmc1CKO mice and observed more than 5-fold increases of GFP-positive puncta in Psmc1CKO hearts (Figure 1G–1H). Together, these in vivo data suggest that genetic PSMI induces the ALP in the heart.

Homozygous Psmc1CKO mice developed severe cardiac failure shortly after birth, as revealed by conscious echocardiography (Echo) at postnatal day 2. Echo analyses showed unchanged left ventricular (LV) end-diastolic posterior wall thickness (LVPW) but increased LV internal diameter (LVID) at both end-diastole and end-systole, decreased LV ejection fraction (EF), and reduced conscious heart rate in comparison with their littermate controls, including αMyHC-Cre transgenic, Psmc1f/+, Psmc1f/f, and heterozygous Psmc1CKO mice. All homozygous Psmc1CKO mice died by postnatal day 10 (Supplementary Figure II). Our data demonstrate that Psmc1 is essential for cardiac UPS function, cardiac development and perinatal survival in mice.

Upregulation of p62 and autophagic flux in cardiomyocytes by genetic PSMI.

The increase of autophagosomes observed in Psmc1CKO hearts could be secondary to cardiac dysfunction and/or a consequence to an impairment in the removal of autophagosomes. To address this question, we tried autophagic flux assays using intraperitoneal injections of bafilomycin A1 (BFA) to block lysosomal removal of autophagosomes but our multiple attempts failed because, unlike 2-week-old or older mice,33 the BFA-treated neonatal mice (5 days or younger), especially the Psmc1CKO ones, died before a discernible cardiac lysosome inhibition can be achieved. Hence, we turned to cardiomyocyte cultures for autophagic flux assays. First, we induced Psmc1 deletion by infecting neonatal cardiomyocytes from Psmc1f/f mice with adenoviruses expressing Cre (Ad-Cre). LC3-II proteins were significantly reduced in Psmc1-depleted cells, and inhibition of lysosomes with bafilomycin A1 (BFA) led to a greater increase of LC3-II in these cells when compared with the control cells (Figure 2A, C, D); by contrast, Ad-Cre did not alter LC3-II flux in WT mouse cardiomyocytes (Figure 2B–D). These data demonstrate that PSMI via ablation of Psmc1 increases LC3-II flux in cardiomyocytes. Next, we silenced Psmc1 in neonatal rat ventricular myocytes (NRVMs) using Psmc1-speicfic siRNA (siPsmc1), which led to a remarkable increase in total ubiquitinated proteins and p62 (Figure 2E, F). Lysosomal inhibition with BFA accumulated more p62 proteins in NRVMs transfected with siPsmc1 than in those treated with a control siRNA targeting Luciferase (siLuci) (Figure 2G–I), indicating that Psmc1 knockdown increases p62 flux, another indicator of autophagic flux.34 The LC3-II flux or p62 flux index (Figure 2D, 2I) respectively refers to the net amount of LC3-II or p62 proteins accumulated by the BFA-mediated lysosomal inhibition. Consistently, confocal microscopy of double-immunostaining for LC3 and ubiquitin detected that siPsmc1 increased both ubiquitin and LC3 puncta in cultured NRVMs and that BFA treatment appeared to accumulate more LC3 puncta and ubiquitin puncta in siPsmc1 treated NRVMs than in those treated by siLuci (Figure 2J), which further supports that genetic PMSI increases autophagic flux in cardiomyocytes. Notably, most of the LC3 puncta are ubiquitin-positive (Figure 2J), suggesting that removal of the ubiquitinated proteins accumulated by PSMI is a major role of the increased autophagic flux. Together, these data demonstrate compellingly that genetic PSMI is sufficient to activate autophagy in cardiomyocytes.

Figure 2. Genetic inhibition of the proteasome increases p62 and autophagic flux in cardiomyocytes.

A - D, Neonatal mouse ventricular cardiomyocytes (NMVMs) were isolated from neonatal PSMC1f/f (A) or WT (B) mice and infected with Ad-Gal (circle) or Ad-Cre (triangle) for 72 hours. The cells were treated with vehicle (Veh) or Bafilomycin A1 (BFA, 100 nM) for 4 hours before harvest. Shown are representative western blots of the indicated proteins (A, B) and the pooled densitometry data of LC3-II (C) and derived LC3-II flux (D). E - J, Neonatal rat ventricular myocytes (NRVMs) were transfected with siRNAs targeting Psmc1 (siPSMC1; red) or luciferase (siLuci, yellow) for 72 hours. Some of the cells were treated with BFA (100 nM, 2 hours) or Veh for autophagic flux assays (G-J). E-I, Western blots (E, G) and the quantification of p62 (H) and the derived p62 flux (I). Each lane and dot represent a biological repeat; n=4 biological repeats for each group in all quantitative panels. The p values shown are either the precise p values derived from two-sided and unpaired t test (D, I) or the adjusted p values from two way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s tests (C, H) or from multiple t-tests corrected for multiple testing with the Holm-Sidak method (F). J, Representative confocal fluorescent images of cells immunostained for ubiquitin (Ub, green) and LC3 (red).

Activation of myocardial TFEB in mice by pharmacological and genetic PSMI.

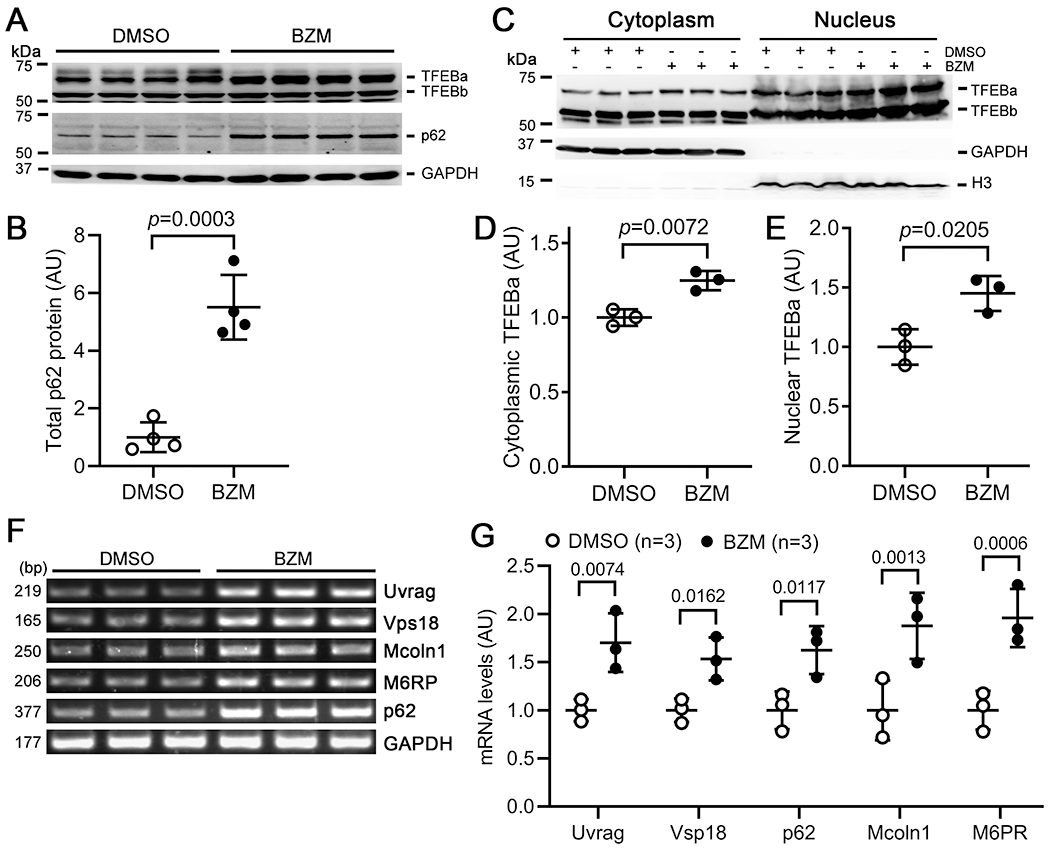

The molecular mechanisms underlying the interplay between the UPS and autophagy are incompletely understood. TFEB is a master regulator of autophagy and lysosome function by acting as a transcription factor that induces the expression of a network of genes involved in autophagosome and lysosome biogenesis.19 Western blot analysis showed that administration of a bolus of bortezomib (BZM, 10 μg/kg), markedly increased myocardial p62 (Figure 3A, B) and ubiquitinated proteins in mice (Supplementary Figure III). This was accompanied by a reduction of the slower-migrating TFEBa band and consequently an increase of its faster migrating counterpart (Figure 3A), indicative of increases in dephosphorylated TFEBa by pharmacological PSMI. Dephosphorylated TFEB is prone to nuclear translocation to induce autophagy.19 Indeed, subcellular fractionation analyses revealed increases of TFEBa in both cytoplasmic and nuclear fractions of the myocardium from mice treated with BZM, compared with vehicle control treatment (Figure 3C–3E; Supplementary Figure IV). Similarly, PSMI seemed to have triggered nuclear translocation of TFEBb as well (Figure 3C). In further support of the transactivation of TFEB by PSMI, gene expression analyses revealed significant increases in the mRNA levels of Uvrag, Vps18, Mcoln1, M6PR and p62/Sqstm1, the well-known target genes of TFEB,19 in BZM-treated mouse hearts (Figure 3F, G).

Figure 3. Pharmacological PSMI increases myocardial p62 and activates TFEB in mice.

Mixed sex WT mice at 5 weeks of age were treated with bortezomib (BZM; 10 μg/kg, i.p.; open circle) or vehicle control (60% DMSO in saline; solid circle) for 12 hours. Ventricular myocardium was sampled for protein and RNA analyses. A and B, Western blots (A) of indicated proteins and pooled densitometry data of p62 proteins (B). N= 4 mice/group; two-sided and unpaired t-test.. C-E, Western blot (C) of TFEB in the cytoplasmic and nuclear fractions of ventricular myocardial proteins and the densitometry data (D, E). Here in-lane loading control used the stain-free total protein imaging technology (Supplementary Figure 4). GAPDH and histone H3 (H3) serve as cytoplasmic and nuclear proteins marks, respectively. N=3 mice/group; two-sided and unpaired t-test. F and G, Representative images of RT-PCR (F) and quantitative real-time PCR (qPCR) data (G) of indicated genes. N=3 mice/group; shown are adjusted p value derived from the multiple t-tests corrected with the Holm-Sidak method. Each lane and each dot represent a unique mouse.

To determine if genetic PSMI also activates TFEB, we performed immunostaining to analyze TFEB localization in mouse hearts at postnatal day 2 and observed ~3-fold more cardiomyocytes with nuclear TFEB-positive staining in Psmc1CKO hearts (Figure 4A, 4B). Western blot analysis revealed that depletion of Psmc1 resulted in a significant increase of TFEBa proteins in mouse hearts (Figure 4C–4D). Psmc1CKO also significantly increased the transcripts of TFEB target genes including p62/Sqstm1, Uvrag, Vps18 and Mcoln1 (Figure 4E).

Figure 4. Genetic PSMI via Psmc1CKO activates myocardial TFEB in mice.

A and B, Immunostaining of TFEB (green) in the myocardium sections of CTL (yellow circle) and Psmc1CKO (KO; red circle) mice at P2. Representative confocal micrographs (A) and the percentage of TFEB-positive nuclei (arrowheads) were quantified (B). The sections were counterstained with Phalloidin (red) and DAPI (blue), respectively. Bar, 20 μm. C and D, Western blots (C) and the quantification (D) of TFEB in CTL and Psmc1CKO hearts at P2. E, qPCR analyses of indicated genes in CTL and Psmc1CKO hearts. Each lane and each dot represent a unique mouse. The p values shown are from two-sided and unpaired t test (B, D), or multiple t-tests corrected for multiple testing with the Holm-Sidak method (E).

In cultured NRVMs, BZM treatment also dramatically reduced the slower-migrating TFEBa and increased the faster-migrating TFEBa (Figure 5A), indicative of enhanced dephosphorylation and nuclear translocation. Indeed, subcellular fractionation analyses showed that nuclear TFEBa is the faster-migrating forms and BZM treatment led to a significant accumulation of TFEBa in the nucleus at both 12 and 24 hours (Figure 5B, C). Immunostaining for TFEB further confirmed that more BZM-treated cardiomyocytes than the control cells displayed nuclear enrichment of TFEB (Figure 5D). The mediating role of TFEB in the induction of p62 and other ALP genes by PSMI was further confirmed by the TFEB knockdown experiments, which revealed that TFEB knockdown significantly attenuated PSMI-induced upregulation of the mRNA levels of p62 and other ALP-related genes (Figure 5E) and p62 proteins (Supplementary Figure V).

Together, these lines of in vivo and in vitro evidence compellingly demonstrate that both pharmacological and genetic PSMI activate TFEB and its downstream signaling in cardiomyocytes.

TFEB activation by PSMI in a calcineurin-dependent manner.

Phosphorylation of TFEB dictates its subcellular localization and transcriptional activity; the dephosphorylated TFEB translocates from cytoplasm to the nucleus where it initiates downstream gene expression.19 We have previously reported that PSMI activates the calcineurin-NFAT pathway in cardiomyocytes and mouse hearts.35 Here we observed that the mRNA levels of MCIP1.4, a target gene of the calcineurin-NFAT pathway, were significantly higher in cultured NRVMs and mouse hearts that were treated with a proteasome inhibitor than those in the controls (Supplementary Figure VI). Cyclosporine A (CsA) is a potent calcineurin inhibitor. CsA treatment restored the levels of the slower-migrating TFEB bands in the BZM-treated cardiomyocytes in a dose-dependent manner (Supplementary Figure VII), indicating that calcineurin activation is responsible for PSMI-induced TFEB dephosphorylation. Subcellular fractionation (Figure 6A, B) and immunostaining (Supplementary Figure VIII) further confirmed that inhibition of calcineurin by CsA blunted BZM-induced TFEB nuclear translocation. Moreover, CsA treatment attenuated BZM induction of an array of TFEB target genes involved in autophagy and lysosome biogenesis (Supplementary Figure IXA, B). Genetic inhibition of calcineurin via calcineurin Aβ knockdown also significantly attenuated the activation of TFEB target genes by PSMI (Figure 6C). Together, these findings demonstrate that calcineurin activity is required for PSMI to activate TFEB in cardiomyocytes.

TFEB activation by PSMI requires Mucolipin 1 (Mcoln1).

Mcoln1, also known as transient receptor potential mucolipin 1 (TRPML1), is the main calcium channel on the membrane of late endosomes and lysosomes.20 It is purported that during autophagic activation, calcium released from lysosomes via Mcoln1 activates calcineurin, which in turn dephosphorylates TFEB and promotes TFEB nuclear translocation.20 To our best knowledge, this has not been demonstrated in cardiomyocytes. We observed significant upregulation of Mcoln1 gene expression in BZM-treated hearts, Psmc1CKO hearts, and BZM-treated cultured cardiomyocytes (Figures 3, 4, 6). We then determined the impact of silencing Mcoln1 via transfection of Mcoln1-specific siRNA on PSMI-induced TFEB activation in cultured NRVMs. Our results showed that silence of Mcoln1 effectively suppressed BZM-induced TFEB nuclear translocation (Figure 6D, E) and attenuated BZM-induced upregulation of TFEB downstream genes (Figure 6F, Supplementary Figure IXC, D). Thus, we conclude that PSMI-induced TFEB activation requires Mcoln1.

Requirement of p62 for PSMI to increase autophagy flux in mouse cardiomyocytes and hearts.

p62 can serve as an adaptor protein that bridges ubiquitinated proteins or organelles to autophagosomes for selective degradation although p62 also may play a role in non-selective autophagy and even non-autophagy processes.32 This is supported by the co-localization among p62, ubiquitin, and LC3 puncta in cardiomyocytes with PSMI (Supplementary Figure X). PSMI upregulates p62 at both mRNA and protein levels in the heart (Figures 1E, 2A, 3A, 3B, 3F, 3G and 4E) in a TFEB dependent manner (Supplementary Figure V) but its roles in PSMI-induced autophagy and TFEB activation are not clear. At baseline, myocardial LC3-II flux was comparable between wild type (WT) and p62-KO mice; PSMI with MG-262 significantly increased LC3-II turnover in WT mouse hearts but not in p62-KO hearts (Figure 7A–7C). To determine whether the effect of p62-KO observed in mouse hearts is cardiomyocyte-autonomous, we also performed similar tests in cultured mouse cardiomyocytes isolated from WT and p62-KO neonatal mice. Similar to the results from the in vivo tests, PSMI induced a significant increase in LC3-II flux in WT cardiomyocytes but not in p62-KO cardiomyocytes. Different from the in vivo findings, LC3-II flux was significantly lower in p62-null cardiomyocytes than in WT cardiomyocytes under the basal condition (Figure 7D–7F). Moreover, we also assessed the effects of PSMI with BZM and of lysosome inhibition with BFA on the level of steady state ubiquitin conjugates in these cardiomyocytes (Supplementary Figures XI). Treatment with either BZM or BFA alone induced a marked increase of total ubiquitinated proteins in both WT and p62-KO cells but the increase in the p62-KO cells was much less than in the WT cells. The treatment combining BZM and BFA showed a discernible additive effect in the WT but not p62-KO cells, indicating that p62 is required for proteasome malfunction to increase the lysosome-mediated clearance of ubiquitinated proteins in cardiomyocytes. Importantly, experiments using cultured NRVMs also revealed that genetic PSMI via siRNA-mediated Psmc1 silence induced remarkably less accumulation of total ubiquitinated proteins in the cells with siRNA-mediated p62 depletion compared with those without p62 depletion (Supplementary Figures XII). Taken together, these in vivo and in vitro experiments demonstrate that compensatory upregulation of autophagic degradation of ubiquitinated proteins under a PSMI or proteasome malfunction state requires p62.

Figure 7. p62 is required for PSMI to increase autophagic flux in mouse hearts and cardiomyocytes.

A-C, Western blots (A) and the quantification of myocardial LC3-II (B) and the derived LC3-II flux (C). WT and p62KO mice at 6-8 weeks of age were first treated with MG262 (5 μmol/kg, i.p.; solid symbol) or vehicle control (DMSO; open symbol) for 11 hours and subsequently with bafilomycin A1 (BFA, 3 μmol/kg, i.p.; triangle) or DMSO (circle) for additional 1 hour. Ventricular myocardium were collected for the analyses. N=3 mice for each group. D-F, LC3-II flux assays for cardiomyocytes isolated from WT and p62KO mice at postnatal day 2. The cells were treated with bortezomib (BZM; 25 nM) for 6 hours, followed by BFA (25 nM) treatment for additional 6 hours. Shown are western blots (D) of indicated proteins and the quantification of LC3-II (E) and derived LC3-II flux (F) from 3 biological repeats. The stain-free total proteins serve as loading control (L.C.) and a segment of the image is shown. Data were analyzed by two-way (C, F) or three-way (B, E) ANOVA, which all show statistical significance in both treatment effects and interaction among factors; as such they were followed by Tukey’s post hoc multiple comparisons tests to give rise the p values shown in the figure. N = 3 mice for each group.

p62 deficiency exacerbates PSMI-induced LV diastolic malfunction.

At baseline, 5~6 weeks old p62-KO mice showed a moderate decrease in the body weight (BW)-normalized Echo-derived LV mass and corrected LV mass, compared with WT mice (p=0.028 for both) but the BW and all other Echo-based parameters were comparable between them (Supplementary Table-I). We treated sex-matched WT and p62-KO mice with daily intraperitoneal injections of BZM (1mg/g) or vehicle control. We observed no difference in mouse mortality as each group had a BZM-treated mouse died at the third and fourth days after initiation of the injection. We performed longitudinal comparison of Echo parameters within each mouse between 3 hours post the 3rd injection and baseline (Supplementary Figures XIII and XVI). The 3 consecutive daily injections of BZM did not consistently change the heart rate in either genotype but led to significant BW decreases and the decreases are comparable between two genotypes. BZM-induced increases in EF and fractional shortening (FS), as well as changes in all other end-systolic parameters are not significantly different between WT and p62-KO mice. However, the BZM-induced increases in all end-diastolic parameters as well as the decreases in LV end-diastolic volume/BW, stroke volume (SV), cardiac output (CO), SV/BW, and CO/BW are significantly greater in p62-KO mice than in WT mice. Echo-based LV mass and corrected LV mass were significantly decreased by BZM in WT but not p62KO mice and a similar trend was evident when the LV mass parameters were normalized to BW. Hence, the moderate difference of the BW-normalized LV mass parameters between the two genotypes at baseline was obliterated by BZM treatment, resulting in a comparable heart weight/BW ratio or ventricular weight/BW ratio between the two genotypes after the BZM treatment (Supplementary Figure XV). Taken together, these data indicate that p62 protects against PSMI from impairing diastolic function.

A positive feedback by p62/Sqstm1 on TFEB activation.

p62 is a TFEB target gene. Our data presented thus far also compellingly support that induction of p62 by PSMI in cardiomyocytes is mediated by TFEB activation. Although p62 is just one of the TFEB target genes, PSMI-induced increases in autophagic removal of both LC3-II and ubiquitinated proteins were completely abolished in mouse hearts and cardiomyocytes deficient of p62. This prompted us to speculate that p62 is required for PSMI to sustain TFEB activation; hence, we further compared the TFEB activation by PSMI between WT and p62-KO mice. Immunofluorescence confocal microscopy showed that p62 deficiency significantly attenuated PSMI-induced TFEB nuclear translocation (Figure 8A). mRNA expression analyses further showed that induction of representative TFEB target genes by PSMI was discernibly less effective in p62-KO mice than in WT mice (Figure 8B, Supplementary Figure XVI). These results indicate that p62 unexpectedly plays a feed-forward role in continuous TFEB activation during PSMI. To explore preliminarily a potential underlying mechanism, we found that BZM treatment suppressed mTORC1 and mTOR proteins largely co-localized with the increased p62 puncta in NRVMs treated with BZM (Supplementary Figure-XVII).

DISCUSSION

Both UPS and ALP are pivotal to protein quality and quantity control in the cell. Targeting these pathways is becoming an attractive strategy for treating human disease, especially for cancer therapies. For example, proteasome inhibitors are highly efficacious in treating multiple myeloma.36 However, a significant proportion of patients receiving a proteasome inhibitor-containing regime show cardiotoxicity.37 Moreover, UPS and ALP defects are implicated in the pathogenesis of a large subset of heart disease or heart failure.2 Therefore, a better understanding of the interplay between these two catabolic pathways is expected to advance cardiac pathophysiology and to identify potentially new therapeutic targets. Prior studies have suggested that proteasome malfunction increases p62 and activates autophagy in cardiomyocytes but the underlying mechanisms were unclear.14, 15 Here we have confirmed this with genetically induced cardiac PSMI. More importantly, we have delineated for the first time the Mcoln1-calcineurin-TFEB-p62 pathway in mediating the autophagic activation by proteasome malfunction and discovered that Mcoln1 and p62 play an essential feed-forward role in TFEB activation by PSMI (Figure 8C). Activation of autophagy apparently acts to minimize the toxicity resulting from proteasome malfunction and thereby helps maintain proteostasis in the cell. These discoveries provide significant mechanistic insight into cardiac proteostasis.

Proteasome malfunction activates the ALP.

Both proteasome malfunction and activation of autophagy are observed in the heart of well-established mouse models of cardiac proteinopathy and a mouse model of hypertrophic cardiomyopathy that carries a mutant of myosin-binding protein C.15, 38 Supporting a functional link between the UPS and the ALP in myocardium, administration of BZM to mice increased autophagosomes and autophagic flux in the heart.14 The present study has achieved and characterized cardiomyocyte-restricted ablation of an essential proteasome subunit gene (Psmc1) for the first time in vertebrates (Supplementary Figure I, II), which along with genetic PSMI in cultured cardiomyocytes confirms that PSMI activates autophagy (Figure 1 and 2). PSMC1 is indispensable for 26S proteasomes. Deletion of Psmc1 in neurons caused neuronal degeneration in mice.26 Here we report that targeting Psmc1 in mouse hearts also led to severe proteasome impairment, as evidenced by the drastic accumulation of ubiquitinated proteins and protein aggregates and by a significant increase of the proteasome surrogate substrate (GFPdgn). Upon proteasome inactivation, we observed a remarkable increase of autophagosomes and an upregulation of autophagic proteins, including p62 and LC3-II in the heart. Moreover, p62 frequently co-localized with ubiquitinated proteins and LC3 puncta (i.e., autophagosomes) in Psmc1-depleted cardiomyocytes (Supplementary Figure X), representing an intermediate state of these cargos en route to lysosomal degradation. These lines of evidence, coupled with the increased autophagic flux in Psmc1-deficient cardiomyocytes, demonstrate that autophagy is activated by genetically induced proteasome malfunction in the heart. Apparently, the ALP activation is not sufficient to compensate loss of proteasome function in the heart because perinatal Psmc1 ablation in cardiomyocytes resulted in severe dilated cardiomyopathy and mouse premature death (Supplementary Figure II).

Proteasome malfunction activates TFEB.

One of the most important contributions of this study is the discovery that PSMI activates TFEB, the master transcription regulator for the ALP. First, we found that pharmacological PSMI increases myocardial TFEB protein levels, TFEB nuclear translocation, and TFEB target gene expression (Figure 3); second, genetic PSMI via Psmc1CKO increased TFEB nuclear localization and TFEB target gene expression in mice (Figure 4); and lastly, PSMI induced rapidly TFEB dephosphorylation, nuclear translocation, target gene expression in a cardiomyocyte-autologous manner (Figures 5, 6). Thus, both in vitro and in vivo evidence compellingly demonstrate a rapid activation of TFEB by proteasome malfunction.

The activation of TFEB is capable of upregulating coordinately the full spectrum of ALP genes required for sustained autophagic degradation. Indeed, induction of ALP genes including p62 by PSMI in cardiomyocytes was significantly attenuated by TFEB inhibition (Figure 5E and Supplementary Figure V). Hence, our identification of a previously unrecognized role of TFEB in mediating the crosstalk between the UPS and ALP is highly significant because increasing TFEB has been shown to confer cardioprotection under a number of pathological conditions.22, 23, 39

Proteasome malfunction activates TFEB via Mcoln1-Calcineurin.

In TFEB activation by starvation, calcineurin which is activated by the calcium released from the lysosome via Mcoln1, is responsible for the dephosphorylation of TFEB.20 The role of calcineurin in the activation of TFEB by PSMI has not been examined in any cell types before. We previously showed the activation of the calcineurin-NFAT pathway in cultured cardiomyocytes by PSMI and in the heart of mice with UPS functional insufficiency.35 And this is further confirmed in the present study because the mRNA levels of MCIP1.4/Rcan1, a bona fide target gene of the calcineurin-NFAT pathway, were significantly increased by PSMI in both cultured cardiomyocytes and intact mice (Supplementary Figure VI). This increased calcineurin activity plays an important role in mediating the TFEB activation by PSMI because inhibition of calcineurin phosphatase activity with CsA diminished PSMI-induced TFEBa dephosphorylation in a dose-dependent fashion (Supplementary Figure VII) and markedly reduced PSMI-induced TFEB nuclear localization and target gene expression (Figure 6; Supplementary Figure VIII). This is further supported by that siRNA-mediated calcineurin inhibition also significantly attenuated the induction of representative TFEB target genes by PSMI (Supplementary Figure IX).

The role of Mcoln1 in TFEB activation was not investigated previously in cardiomyocytes; moreover, the role of Mcoln1 in the activation of TFEB by PSMI has not been examined in any cell types before. Here we found that as a target gene of TFEB, Mcoln1 expression was significantly increased by PSMI whereas prevention of this increase abolished PSMI-induced TFEBa nuclear translocation and the expression of TFEB target genes (Figure 6), demonstrating for the first time that Mcoln1 is indispensable in the TFEB activation by PSMI. This also indicates that calcium release from lysosomes to the cytosol via Mcoln1 plays an essential role in the activation of the phosphatase calcineurin by PSMI and that Mcoln1 exerts a feedforward role in the TFEB activation by PSMI. Since it has been reported that calcineurin is degraded by the UPS and calcineurin proteins accumulate in mouse hearts with UPS impairment,35, 40 it is highly likely that PSMI increases calcineurin activities through both stabilization of calcineurin proteins and, via Mcoln1, facilitation of calcineurin activation. As a lysosomal calcium channel, Mcoln1 can be activated by lysosomal stress.41 Upon PSMI, the share of ubiquitinated proteins that goes to the ALP for degradation is dramatically increased and thereby imposes stress on lysosomes. Mcoln1 can act as a reactive oxygen species (ROS) sensor and be activated by increased ROS;42 hence, the activation of Mcoln1 by PSMI may also be through increasing ROS as PSMI has been shown to increase ROS production in the cell.43

The role of p62/Sqstm1 in the activation of autophagy by PSMI.

We previously reported upregulation of myocardial p62 and autophagy in mouse models of cardiac proteinopathy.15 Here we collected both in vivo and in vitro evidence that both pharmacological and genetic PSMI upregulate both mRNA and protein levels of p62 in cardiomyocytes (Figures 1–4, 6, 7). At least a part of this upregulation is mediated by TFEB because inhibition of TFEB activation via calcineurin inhibition, Mcoln1 knockdown (Figure 6), or TFEB knockdown (Supplementary Figure V) all blunted the induction of p62 by PSMI. In agreement with our findings, a recent study detected in non-cardiac cells that a short exposure to BZM could lead to a rapid increase in the mRNA levels of p62 and GABARAPL1 but not in other ALP genes although a longer exposure induced most of them.44 In stark contrast to our findings, their further experiments showed TFEB knockdown did not alter the induction of p62 by BZM in M17 cells,44 suggesting the mechanisms by which PSMI upregulates p62 may be cell-type specific.

p62 can bind ubiquitinated substrates via its ubiquitin-associated domain (UBA) and help the bound cargos to form aggregates through its PB1-domain-mediated self-oligomerization;3 meanwhile, p62 recruits and activates the core autophagosome machinery and recruits ATG8/LC3 decorated phagophore via its LC3-interacting region (LIR).32, 45 Hence, p62 acting as the prototype receptor for ubiquitinated cargos plays likely an important role in cargo-initiated selective autophagy. However, the in vivo necessity of p62 in cardiac proteostasis at baseline and during proteotoxic stress was not established before the present study. Here we detected that the basal level of myocardial lysosome-mediated LC3-II flux was comparable between WT and p62-KO mice but the responses of the LC3-II flux to PSMI were drastically different between them (Figure 7A–7C). During PSMI, myocardial LC3-II flux was substantially increased in WT mice but the flux became completely undetectable in the p62-KO mice. Similar findings were obtained in cultured neonatal mouse cardiomyocytes but, notably, p62-deifciency significantly decreased LC3-II flux and the lysosome-mediated flux of ubiquitinated proteins under both the control culturing condition and during PSMI (Figure 7D–7F, Supplementary Figure XI). This difference between in vivo and cell culture studies is likely caused by that cardiomyocytes when cultured in vitro experience inevitable stresses even in absence of exposure to a proteasome inhibitor. Taken together, these new in vivo and in vitro findings support compellingly that p62 is required for activation of autophagy and for lysosomal removal of ubiquitinated proteins in cardiomyocytes and hearts during proteasome malfunction.

There is strong evidence that the rapid upregulation of p62 by PSMI helps channel ubiquitinated proteins to the ALP for degradation and thereby alleviates the accumulation of ubiquitinated proteins resulting from proteasome malfunction. p62 does so through promoting the aggregation of ubiquitinated proteins and targeting the ubiquitinated cargoes to the ALP. This is consistent with our findings that most p62 proteins are co-localized with ubiquitin-positive protein aggregates and LC3-positive puncta in cardiomyocytes with PSMI (Figures 1D, 2I and Supplementary Figure X). Besides binding to ubiquitinated cargos and targeting them selectively to the ALP, p62 was recently shown to recognize and bind the N-degron in proteins that are normally degraded by the UPS via the N-end rule pathway.46 Hence, upon proteasome impairment, the accumulated proteins with an N-degron may use the upregulated p62 as the bridge to the ALP pathway in a ubiquitin-independent manner. Nevertheless, the rapid upregulation of p62 by PSMI requires ubiquitination, according to a recent report.44 Consistent with findings from prior studies using cultured cells,44 including cultured cardiomyocytes,15 our in vivo and in vitro work revealed that the PSMI-induced increases in the steady state total ubiquitinated proteins in hearts (data not shown) and cultured cardiomyocytes (Supplementary Figures XI) were significantly less in p62-KO mice compared with WT mice and this was recapitulated in NRVMs subjected to siRNA-mediated Psmc1 and p62 silencing (Supplementary Figure XII). These findings suggest that in absence of p62-meidated aggregation, a significant portion of ubiquitinated proteins may undergo deubiquitination in cardiomyocytes with proteasome malfunction.

The role of p62/Sqstm1 in the activation of TFEB by PSMI.

An unexpected finding of this study is that p62 positively feeds back on TFEB activation in the heart, as evidenced by that cardiac TFEB nuclear localization and target gene expression induced by PSMI were remarkably attenuated in the p62-KO mice than the WT mice (Figure 8). The mechanism by which p62 does so is currently unclear. Nevertheless, we detected that PSMI suppressed mTORC1 activities (Supplementary Figure VIIA, B), which is consistent with TFEB activation by PSMI because mTORC1 phosphorylates and inactivates TFEB.19 More interestingly, an increased proportion of mTOR proteins was co-localized with p62-positive protein aggregates in BZM-treated NRVMs (Supplementary Figure XVIIC). Hence, we propose that p62-meidated aggregation of ubiquitinated proteins during PSMI sequesters mTOR and prevents it from phosphorylating TFEB, rendering TFEB more susceptible to calcineurin-mediated dephosphorylation. It is also conceivable that the consumption of lysosomal machinery by p62-mediated increases of autophagy during PSMI can activate TFEB to replenish ALP machinery.

Supplementary Material

NOVELTY AND SIGNIFICANCE.

What Is Known?

Proteasome functional insufficiency contributes to cardiac pathogenesis.

Pharmacological proteasome inhibition (PSMI) upregulates calcineurin signaling, p62/Sqstm1, and autophagy.

Transcription factor EB (TFEB) is a master regulator of the autophagic-lysosomal pathway (ALP).

What New Information Does This Article Contribute?

Genetic PSMI upregulates p62, activates TFEB, and induces autophagy in cardiomyocytes and hearts.

Calcineurin and mucolipin 1 (Mcoln1) mediate the TFEB activation by PSMI whereas TFEB in turn mediates the upregulation of p62 and autophagy by PSMI in cardiomyocytes.

Both p62 and Mcoln1 regulate the TFEB and autophagy activation by PSMI in a feed-forward manner.

Proteasome malfunction is implicated in the progression from a large subset of heart diseases to heart failure. Many patients receiving PSMI chemotherapies develop cardiotoxicity. Compensatory activation of cardiac autophagy occurs in heart diseases with proteasome malfunction but a mechanistic link between proteasome malfunction and autophagy remains obscure. We conducted this study to fill this critical gap. Here we have demonstrated that both cardiomyocyte-restricted PSMI and global PSMI upregulate myocardial p62 expression, TFEB activity, and autophagy. PSMI induction of TFEB dephosphorylation and nuclear translocation, as well as the expression of TFEB target genes (e.g., p62 and Mcoln1) in cardiomyocytes requires the lysosomal calcium channel Mcoln1 and the activation of the calcium-dependent phosphatase calcineurin. p62 deficiency abolishes PSMI induction of myocardial autophagy, attenuates the TFEB activation by PSMI, and exacerbates cardiac dysfunction induced by PSMI. Thus, we have identified that the Mocln1-calcineurin-TFEB-p62 pathway mediates the autophagy activation by the proteasome malfunction in cardiomyocytes and discovered that p62 unexpectedly exerts a feed-forward effect on TFEB activation. This not only yields new insight into the cross talk between proteasomal and lysosomal degradation but also promotes the search for new therapeutic strategies for heart disease with increased proteotoxicity.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We are in debt to Dr. Douglas S. Martin of the University of South Dakota Sanford School of Medicine and Dr. Erliang Zeng of University of Iowa College of Dentistry for their advice on statistical analyses.

SOURCES OF FUNDING

This study is in part supported by NIH R01 grants HL072166, HL085629 (to X.W.), and HL131667 (to X.W., T.C.), and HL124248 (to H.S.), and by AHA grant 19TPA34880050 (to H.S.).

Nonstandard Abbreviations and Acronyms :

- ALP

autophagic-lysosomal pathway

- BFA

bafilomycin A1

- CLEAR

the coordinated lysosomal expression and regulation element

- CnAβ

calcineurin catalytic subunit Aβ

- CsA

cyclosporine A

- CTL

control

- KO

knock out

- mTORC1

mechanistic target of rapamycin complex 1

- PFI

proteasome functional insufficiency

- Psmc1-cKO

cardiomyocyte-restricted knockout of the Psmc1 gene

- PSMI

proteasome inhibition

- UPS

ubiquitin-proteasome system

- WT

Wild type

Footnotes

DISCLOSURES

The authors declared there was no conflict of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Wang X, Pattison JS and Su H. Posttranslational modification and quality control. Circ Res. 2013;112:367–81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wang X and Robbins J. Proteasomal and lysosomal protein degradation and heart disease. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2014;71:16–24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wang C and Wang X. The interplay between autophagy and the ubiquitin-proteasome system in cardiac proteotoxicity. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2015;1852:188–94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Collins GA and Goldberg AL. The Logic of the 26S Proteasome. Cell. 2017;169:792–806. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Day SM. The ubiquitin proteasome system in human cardiomyopathies and heart failure. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2013;304:H1283–93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Weekes J, Morrison K, Mullen A, Wait R, Barton P and Dunn MJ. Hyperubiquitination of proteins in dilated cardiomyopathy. Proteomics. 2003;3:208–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Li J, Horak KM, Su H, Sanbe A, Robbins J and Wang X. Enhancement of proteasomal function protects against cardiac proteinopathy and ischemia/reperfusion injury in mice. J Clin Invest. 2011;121:3689–700. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tian Z, Zheng H, Li J, Li Y, Su H and Wang X. Genetically induced moderate inhibition of the proteasome in cardiomyocytes exacerbates myocardial ischemia-reperfusion injury in mice. Circ Res. 2012;111:532–42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Li J, Powell SR and Wang X. Enhancement of proteasome function by PA28α overexpression protects against oxidative stress. FASEB J. 2011;25:883–93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rajagopalan V, Zhao M, Reddy S, Fajardo GA, Wang X, Dewey S, Gomes AV and Bernstein D. Altered Ubiquitin-Proteasome Signaling in Right Ventricular Hypertrophy and Failure. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2013;305:H551–62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ranek MJ, Zheng H, Huang W, Kumarapeli AR, Li J, Liu J and Wang X. Genetically induced moderate inhibition of 20S proteasomes in cardiomyocytes facilitates heart failure in mice during systolic overload. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2015;85:273–81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Li J, Ma W, Yue G, Tang Y, Kim IM, Weintraub NL, Wang X and Su H. Cardiac proteasome functional insufficiency plays a pathogenic role in diabetic cardiomyopathy. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2017;102:53–60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wang X and Wang H. Priming the proteasome to protect against proteotoxicity. Trends Mol Med. 2020:(in press). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zheng Q, Su H, Tian Z and Wang X. Proteasome malfunction activates macroautophagy in the heart. Am J Cardiovasc Dis. 2011;1:214–26. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zheng Q, Su H, Ranek MJ and Wang X. Autophagy and p62 in cardiac proteinopathy. Circ Res. 2011;109:296–308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pan B, Lewno MT, Wu P and Wang X. Highly Dynamic Changes in the Activity and Regulation of Macroautophagy in Hearts Subjected to Increased Proteotoxic Stress. Front Physiol. 2019;10:758. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Liu J, Chen Q, Huang W, Horak KM, Zheng H, Mestril R and Wang X. Impairment of the ubiquitin-proteasome system in desminopathy mouse hearts. FASEB J. 2006;20:362–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chen Q, Liu JB, Horak KM, Zheng H, Kumarapeli AR, Li J, Li F, Gerdes AM, Wawrousek EF and Wang X. Intrasarcoplasmic amyloidosis impairs proteolytic function of proteasomes in cardiomyocytes by compromising substrate uptake. Circ Res. 2005;97:1018–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wang X and Cui T. Autophagy modulation: a potential therapeutic approach in cardiac hypertrophy. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2017;313:H304–H319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Medina DL, Di Paola S, Peluso I, Armani A, De Stefani D, Venditti R, Montefusco S, Scotto-Rosato A, Prezioso C, Forrester A, Settembre C, Wang W, Gao Q, Xu H, Sandri M, Rizzuto R, De Matteis MA and Ballabio A. Lysosomal calcium signalling regulates autophagy through calcineurin and TFEB. Nat Cell Biol. 2015;17:288–99. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Palmieri M, Impey S, Kang H, di Ronza A, Pelz C, Sardiello M and Ballabio A. Characterization of the CLEAR network reveals an integrated control of cellular clearance pathways. Hum Mol Genet. 2011;20:3852–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ma X, Mani K, Liu H, Kovacs A, Murphy JT, Foroughi L, French BA, Weinheimer CJ, Kraja A, Benjamin IJ, Hill JA, Javaheri A and Diwan A. Transcription Factor EB Activation Rescues Advanced alphaB-Crystallin Mutation-Induced Cardiomyopathy by Normalizing Desmin Localization. J Am Heart Assoc. 2019;8:e010866. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pan B, Zhang H, Cui T and Wang X. TFEB activation protects against cardiac proteotoxicity via increasing autophagic flux. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2017;113:51–62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ma X, Godar RJ, Liu H and Diwan A. Enhancing lysosome biogenesis attenuates BNIP3-induced cardiomyocyte death. Autophagy. 2012;8:297–309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Godar RJ, Ma X, Liu H, Murphy JT, Weinheimer CJ, Kovacs A, Crosby SD, Saftig P and Diwan A. Repetitive stimulation of autophagy-lysosome machinery by intermittent fasting preconditions the myocardium to ischemia-reperfusion injury. Autophagy. 2015;11:1537–60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bedford L, Hay D, Devoy A, Paine S, Powe DG, Seth R, Gray T, Topham I, Fone K, Rezvani N, Mee M, Soane T, Layfield R, Sheppard PW, Ebendal T, Usoskin D, Lowe J and Mayer RJ. Depletion of 26S proteasomes in mouse brain neurons causes neurodegeneration and Lewy-like inclusions resembling human pale bodies. J Neurosci. 2008;28:8189–98. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Agah R, Frenkel PA, French BA, Michael LH, Overbeek PA and Schneider MD. Gene recombination in postmitotic cells. Targeted expression of Cre recombinase provokes cardiac-restricted, site-specific rearrangement in adult ventricular muscle in vivo. J Clin Invest. 1997;100:169–79. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Komatsu M, Waguri S, Koike M, Sou YS, Ueno T, Hara T, Mizushima N, Iwata J, Ezaki J, Murata S, Hamazaki J, Nishito Y, Iemura S, Natsume T, Yanagawa T, Uwayama J, Warabi E, Yoshida H, Ishii T, Kobayashi A, Yamamoto M, Yue Z, Uchiyama Y, Kominami E and Tanaka K. Homeostatic levels of p62 control cytoplasmic inclusion body formation in autophagy-deficient mice. Cell. 2007;131:1149–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kumarapeli AR, Horak KM, Glasford JW, Li J, Chen Q, Liu J, Zheng H and Wang X. A novel transgenic mouse model reveals deregulation of the ubiquitin-proteasome system in the heart by doxorubicin. FASEB J. 2005;19:2051–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mizushima N, Yamamoto A, Matsui M, Yoshimori T and Ohsumi Y. In vivo analysis of autophagy in response to nutrient starvation using transgenic mice expressing a fluorescent autophagosome marker. Mol Biol Cell. 2004;15:1101–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Glickman MH and Ciechanover A. The ubiquitin-proteasome proteolytic pathway: destruction for the sake of construction. Physiol Rev. 2002;82:373–428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Turco E, Witt M, Abert C, Bock-Bierbaum T, Su MY, Trapannone R, Sztacho M, Danieli A, Shi X, Zaffagnini G, Gamper A, Schuschnig M, Fracchiolla D, Bernklau D, Romanov J, Hartl M, Hurley JH, Daumke O and Martens S. FIP200 Claw Domain Binding to p62 Promotes Autophagosome Formation at Ubiquitin Condensates. Mol Cell. 2019;74:330–346 e11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Su H, Li F, Ranek MJ, Wei N and Wang X. COP9 signalosome regulates autophagosome maturation. Circulation. 2011;124:2117–28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gottlieb RA, Andres AM, Sin J and Taylor DP. Untangling autophagy measurements: all fluxed up. Circ Res. 2015;116:504–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Tang M, Li J, Huang W, Su H, Liang Q, Tian Z, Horak KM, Molkentin JD and Wang X. Proteasome functional insufficiency activates the calcineurin-NFAT pathway in cardiomyocytes and promotes maladaptive remodelling of stressed mouse hearts. Cardiovasc Res. 2010;88:424–33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Aguiar PM, de Mendonca Lima T, Colleoni GWB and Storpirtis S. Efficacy and safety of bortezomib, thalidomide, and lenalidomide in multiple myeloma: An overview of systematic reviews with meta-analyses. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol. 2017;113:195–212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Chang HM, Moudgil R, Scarabelli T, Okwuosa TM and Yeh ETH. Cardiovascular Complications of Cancer Therapy: Best Practices in Diagnosis, Prevention, and Management: Part 1. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2017;70:2536–2551. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Schlossarek S, Englmann DR, Sultan KR, Sauer M, Eschenhagen T and Carrier L. Defective proteolytic systems in Mybpc3-targeted mice with cardiac hypertrophy. Basic research in cardiology. 2012;107:235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Trivedi PC, Bartlett JJ, Perez LJ, Brunt KR, Legare JF, Hassan A, Kienesberger PC and Pulinilkunnil T. Glucolipotoxicity diminishes cardiomyocyte TFEB and inhibits lysosomal autophagy during obesity and diabetes. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2016;1861:1893–1910. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Li HH, Kedar V, Zhang C, McDonough H, Arya R, Wang DZ and Patterson C. Atrogin-1/muscle atrophy F-box inhibits calcineurin-dependent cardiac hypertrophy by participating in an SCF ubiquitin ligase complex. J Clin Invest. 2004;114:1058–71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wang W, Gao Q, Yang M, Zhang X, Yu L, Lawas M, Li X, Bryant-Genevier M, Southall NT, Marugan J, Ferrer M and Xu H. Up-regulation of lysosomal TRPML1 channels is essential for lysosomal adaptation to nutrient starvation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2015;112:E1373–81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Zhang X, Cheng X, Yu L, Yang J, Calvo R, Patnaik S, Hu X, Gao Q, Yang M, Lawas M, Delling M, Marugan J, Ferrer M and Xu H. MCOLN1 is a ROS sensor in lysosomes that regulates autophagy. Nat Commun. 2016;7:12109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Perez-Galan P, Roue G, Villamor N, Montserrat E, Campo E and Colomer D. The proteasome inhibitor bortezomib induces apoptosis in mantle-cell lymphoma through generation of ROS and Noxa activation independent of p53 status. Blood. 2006;107:257–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Sha Z, Schnell HM, Ruoff K and Goldberg A. Rapid induction of p62 and GABARAPL1 upon proteasome inhibition promotes survival before autophagy activation. J Cell Biol. 2018;217:1757–1776. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Turco E, Fracchiolla D and Martens S. Recruitment and Activation of the ULK1/Atg1 Kinase Complex in Selective Autophagy. J Mol Biol. 2019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Cha-Molstad H, Yu JE, Feng Z, Lee SH, Kim JG, Yang P, Han B, Sung KW, Yoo YD, Hwang J, McGuire T, Shim SM, Song HD, Ganipisetti S, Wang N, Jang JM, Lee MJ, Kim SJ, Lee KH, Hong JT, Ciechanover A, Mook-Jung I, Kim KP, Xie XQ, Kwon YT and Kim BY. p62/SQSTM1/Sequestosome-1 is an N-recognin of the N-end rule pathway which modulates autophagosome biogenesis. Nat Commun. 2017;8:102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Su H, Li J, Menon S, Liu J, Kumarapeli AR, Wei N and Wang X. Perturbation of cullin deneddylation via conditional Csn8 ablation impairs the ubiquitin-proteasome system and causes cardiomyocyte necrosis and dilated cardiomyopathy in mice. Circ Res. 2011;108:40–50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Zhang H, Pan B, Wu P, Parajuli N, Rekhter MD, Goldberg AL and Wang X. PDE1 inhibition facilitates proteasomal degradation of misfolded proteins and protects against cardiac proteinopathy Sci Adv. 2019:(in press). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Zou J, Ma W, Li J, Littlejohn R, Zhou H, Kim IM, Fulton DJR, Chen W, Weintraub NL, Zhou J and Su H. Neddylation mediates ventricular chamber maturation through repression of Hippo signaling. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2018;115:E4101–E4110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.