Abstract

Schizophrenia is a common mental disorder with high heritability. It is genetically complex and to date more than a hundred risk loci have been identified. Association of environmental factors and schizophrenia has also been reported, while epigenetic analyses have yielded ambiguous and sometimes conflicting results. Here, we analyzed fresh frozen post-mortem brain tissue from a cohort of 73 subjects diagnosed with schizophrenia and 52 control samples, using the Illumina Infinium HumanMethylation450 Bead Chip, to investigate genome-wide DNA methylation patterns in the two groups.

Analysis of differential methylation was performed with the Bioconductor Minfi package and modern machine-learning and visualization techniques, which were shown previously to be successful in detecting and highlighting differentially methylated patterns in case-control studies. In this dataset, however, these methods did not uncover any significant signals discerning the patient group and healthy controls, suggesting that if there are methylation changes associated with schizophrenia, they are heterogeneous and complex with small effect.

Keywords: DNA methylation, Schizophrenia, machine learning, classification, clustering

1. Introduction

Schizophrenia is characterized by hallucinations, delusions, thought disorder, and cognitive deficits. It is a complex disease that affects approximately 0.5–1% of the population. Even though schizophrenia has a strong genetic component (Rujescu 2012), the disorder does not show Mendelian inheritance. In addition of the complex genetics of schizophrenia, other complexities include fluctuating disease course with periods of remission and relapse, sex differences, peaks of disease susceptibility that coincide with hormonal changes etc. (Mill et al. 2008). In addition, environmental risk such as urbanicity (Pedersen and Mortensen 2001), migrant status (Cantor-Graae and Selten 2005), childhood maltreatment (Arseneault et al. 2011), prenatal infections (Brown and Derkits 2010), and cannabis use (Moore et al. 2007) also contribute to schizophrenia susceptibility.

These observations have led to the speculation that epigenetics is involved in the disease development (Labrie, Pai, and Petronis 2012). Epigenetics is chemical modifications of the DNA that can affect gene regulation, without altering the nucleotide sequence. One example of such a modification is DNA methylation (DNAm), which is the addition of a methyl group to cytosine and converts cytosine to a 5-methyl-cytosine. The modification is correlated with gene expression (Jakovcevski and Akbarian 2012). Interestingly, DNAm is actively involved in regulating glial cell differentiation from neural stem cells and function in the brain (Takizawa et al. 2001). Therefore, studying the epigenetic modifications present in brain cells is critical to gain a more complete understanding of the role of the epigenome in brain functions.

It is not possible to perform methylation studies in vivo in the brain, and many studies are done using peripheral tissue such as blood. Although working with peripheral tissue has its advantages, methylation studies in blood may not detect the pathogenesis of brain disorders. In a recent study, it was observed that only 7.9% of CpG sites showed a statistically significant, large correlation between blood and brain tissue (Walton et al. 2016). Therefore, studies in post-mortem brain tissue are very important. Previous studies have indicated that schizophrenia is associated with a global gene expression disturbance across cortical regions in the brain (Horváth, Janka, and Mirnics 2011) and DNA methylation may be involved in these gene expression changes (Labrie, Pai, and Petronis 2012).

Using the Illumina’s Infinium® HumanMethylation450 BeadChip Assay it is possible to analyze 450 000 CpG sites across the genome. Several methylation studies in brain tissue from subjects diagnosed with schizophrenia have been published during the last years using this technology (Gagliano et al. 2016; Lee and Huang 2016; McKinney et al. 2017; Montano et al. 2016; Ruzicka, Subburaju, and Benes 2017). The majority of the studies have targeted specific regions although some genome-wide studies have been performed, as reviewed previously (Dempster et al. 2013).

In one of the studies using this array, 20 subjects and 23 control individuals have been analyzed. Four CpG sites were found to be differentially methylated, close to the genes GSDMD, RASA3, HTR5A and PPFIA1. Gene ontology (GO) analyses of significant sites indicated that genes associated with differentially methylated CpG sites were enriched for pathways related to ‘schizophrenia and other neuropsychiatric disorders’ and ‘nervous system development and function (Pidsley et al. 2014). In another study genome-wide methylation patterns in prefrontal cortex were compared between 108 adult subjects diagnosed with schizophrenia and 136 non-psychiatric control individuals using the 450K array. GO analysis revealed that the top differentially methylated CpGs were located near genes involved in embryo development, cell fate commitment and nervous system differentiation (Jaffe et al. 2016). The GSDMD gene (identified in the smaller study) has been found to be marginally significant in the larger study but the findings for the other genes could not be replicated. The difficulty to find consistent results among different studies, both at the genetic level and in the pathway analyses might be due to the limitations of the analysis methods, including the computational methods, as well as clinical heterogeneity of the subjects, including antipsychotic medication history.

The ambiguous and varying results of previous studies of methylation modifications in schizophrenia brain tissue prompted us to investigate DNA methylation using a different computational analysis approach. We analyzed brain tissue obtained from 73 individuals diagnosed with schizophrenia and 52 control subjects, using the Illumina 450K bead chip array. The data was analyzed using both canonical methods and state-of-the-art machine learning methods, that have been successfully applied on other DNAm data detecting methylation patterns in ageing and cancer subtyping.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study design

Frontal cortex post-mortem brain tissue samples from subjects diagnosed with schizophrenia and healthy subjects were obtained from international brain banks. In total, tissue samples from 73 subjects diagnosed with schizophrenia and 52 individuals were obtained (Supplementary Table 1). The tissue samples were obtained from four different biobanks, Harvard Brain Tissue Resource center, (HBRC) Massachusets (USA), University of Mississippi Medical Center (UMMC) (USA), London Neurodegenerative Brain Bank (LNDBB) (UK) and MRC Sudden Death Brain and Tissue Bank(MRCE) , Edinburgh (UK), with age and sex matched between subjects with a schizophrenia diagnosis and healthy subjects for each tissue bank. At the time of the autopsy the next-of-kin was always asked if the tissue could be used for research purposes, this was done also in cases where subjects had agreed to participate in the study prior to death. The families of the deceased individual were interviewed and informed that the tissue would be used to increase the knowledge regarding neurological and psychiatric disorders. The specimens were handled according to standardized procedures used in brain research. The majority of the samples (n=107) were from the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex (Brodmann areas 8 and 9) and 18 samples were from orbitofrontal cortex (Brodmann areas 11 and 12). In the analysis the tissues from the different Brodmann areas were analyzed together, since a parallel analysis of the transcriptome did not show significant differences in expression between the two brain regions. Demographic data for age, gender, brain region, pH, post-mortem interval (PMI) and RNA Integrity (RIN) for the subjects diagnosed with schizophrena and the control group are summarized in Table 1. Regional Ethical Review Board in Uppsala approved the use of samples in this study (Dnr 2012/082). For brain samples from the University of Mississippi Medical Center, recruitment, tissue collection, and retrospective psychiatric assessment were performed under a protocol approved by the Institutional Review Boards at University of Mississippi Medical Center and University Hospitals Cleveland Medical Center, Cleveland, OH. All work was carried out in accordance with The Code of Ethics of the World Medical Association (Declaration of Helsinki). Informed written consent was obtained from legally-defined next-of-kin for tissue collection, access to medical records, and informant interviews. Tissues were collected at autopsy at the Cuyahoga County Medical Examiner’s Office, Cleveland, OH, and rapidly frozen. Subjects died suddenly without a prolonged agonal state and the cause of death was determined by the Medical Examiner. Blood samples were assayed by the Medical Examiner’s Office for all currently available antidepressant and antipsychotic medications, as well as ethanol, barbiturates, benzodiazepines, cocaine, amphetamines, opiates, phencyclidine, cannabinoids, and antiepileptic drugs. A licensed clinical social worker administered the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Disorders (First et al., 1995), to knowledgeable next-of-kin for all subjects. Psychopathology was independently assessed by a clinical psychologist and a psychiatrist (both board certified) and a consensus diagnosis was reached using information from the interview, medical records, law enforcement, and the medical examiner. Twenty one and five subjects met DSM-IV criteria for schizophrenia and schizoaffective disorder, respectively. Retrospective psychiatric assessments for the University of Mississippi Medical Center samples were performed as outlined in (Zhu et al. 2012).

Table 1.

Demographics of the samples obtained from the brain banks.

| Demographics | Schizophrenia (n=73) | Control (n=52) | Statistics |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age ± s.d. | 52.5 ± 16.9 | 58.6 ± 15.3 | 0.04 (t-test) |

| Gender | 32F: 41M | 21F: 31M | 0.72 (Chi-square) |

| DLPFC: OFC | 67: 6 | 40: 12 | 0.04 (Chi-square) |

| PMI (hours) ± s.d | 32 ± 21.9 | 38 ± 19.9 | 0.15 (t-test) |

| pH ± s.d | 6.5 ± 0.2 | 6.3 ± 0.1 | 0.01 (t-test) |

| RIN ± s.d | 6.9 ± 1.1 | 6.7 ± 1.0 | 0.31 (t-test) |

DLPFC: dorsolateral prefrontal cortex; OFC: orbitofrontal cortex; PMI: post-mortem interval.

M: male; F:female; RIN: RNA integrity number

Fresh frozen tissue samples were molded in Optimal Cutting Temperature (OCT) and approximately 15 to 20 sections (10 µm) were sliced with a cryostat microtome. DNA was extracted using the QIAamp DNA Mini Kit (Qiagen, Cat No./ID: 51306). The quantity of the DNA was estimated using a Qubit® flourometer 2.0 (Invitrogen/Life technologies); Between 500ng and 1 μg of DNA was sent to the SNP&SEQ Technology Platform at Uppsala University for bisulfite conversion and methylation detection with Illumina’s Infinium® HumanMethylation450 BeadChip Assay. More than 450 000 CpG sites were analyzed, covering 99% of the RefSeq genes, with an average of 17 CpG sites per gene region distributed across the promoter, 5’UTR, first exon, gene body, and 3’UTR (Illumina’s HumanMethylation450 BeadChip Data Sheet).

2.2. Data Analysis

We analyzed the DNA methylation (DNAm) data in order to identify possible differentiating patterns between schizophrenic and control samples. The methylation level is estimated by the beta value, a value between 0 and 1, which represents the ratio of methylated and unmethylated alleles in a cell population.

We started by reading the raw data (IDAT-files) into Bioconductor’s Minfi package (version 1.20.2) (Aryee et al. 2014). The raw data was preprocessed using “preprocessIllumina” function, leading to 485,512 probes and then the beta values were generated from the intensities data. As next step, differentially methylated regions (DMRs) were targeted using bumphunter Bioconductor package. To obtain significant (p-value < 0.05) bump(s) (or DMRs) with at least 3 probes in each region (L >=3), we tried setting different values for the cutoff parameter (identifying the percentage of the difference between case and control), with 1000 permutations (B=1000).

We then classified the samples based on their methylation levels using Monte Carlo feature selection (MCFS) (Draminski et al. 2008), and the ROSETTA rule-based modeling software (Øhrn and Komorowski 1997; Komorowski, Øhrn, and Skowron 2002). In brief, this method works based on a structure known as a decision table, where each row represents a sample and the columns list the features (attributes) of the samples. The features in our analysis are the CpG sites from the chip and their measured beta values. The last column in the table is the outcome (or decision). Here it was either “schizophrenia” or “control”.

In order to remove the CpG sites carrying no differentiating signal over all samples, we applied a standard deviation (SD) filtering. Since applying a SD filtering of 0.2 (as we did in Moghadam et al., 2017), i.e. excluding CpG sites with a standard deviation smaller than 0.2 over all samples, left us with only 3,710 probes, we applied a less stringent filter of 0.06, leading to 351,112 probes. We also excluded the probes from chromosomes X and Y to adjust for the gender effect.

The beta values were discretized as follows: unmethylated for the beta values smaller or equal to 0.2, intermediate for beta values between 0.2 and 0.8, and methylated for beta values higher or equal to 0.8. MCFS was applied to detect the CpG sites that significantly contribute to classification. This process is done prior to training the rule-based modeling in order to reduce the computation time or make it feasible by including only informative features (CpG sites). The selected features were then extracted out of the original decision table into a new one with the same number of samples but only the selected set of features, and then the classifier was generated using ROSETTA.

ROSETTA is based on rough set modeling and its classifier consists of a set of minimal IF-THEN rules that are easy to read and directly interpretable. Each rule shows how a single condition (singleton rule) or a combination of conditions (conjunctive rule) leads to a certain outcome (decision). Here the decisions are “schizophrenic” or “control”. A sample rule looks like the following:

IF CG1 = methylated AND CG2 = unmethylated AND CG3 = methylated THEN

‘schizophrenic’

The rules should be read as: if the condition(s) in the IF part are satisfied for a sample, the model predicts it belongs to the decision class (the THEN part of the rule). Each rule can be evaluated by support and accuracy. The support shows the number of samples for which both IF part and THEN part match the rule, and accuracy is calculated by dividing support by the number of samples matching the IF part of the rule.

Next, we analyzed the data with an unsupervised learning method named methylSaguaro (Torabi Moghadam et al., manuscript in preparation) that segments the genome into differentially methylated patterns. This method employs Saguaro (Zamani et al. 2013), an algorithm that combines neural networks and hidden Markov models. In contrast to the supervised learning methods, here no a priori hypothesis is given to the system while being trained.

Finally, to investigate and highlight the general patterns of DNAm between the schizophrenic and control samples, we used PiiL (Moghadam et al. 2017), an interactive gene pathway browser. PiiL facilitates specific hypothesis testing and searching for specific patterns by projecting the DNA methylation and/or gene expression data onto KEGG pathways, and providing a comprehensive set of analytical functions; among them, various filters for selecting a subset of multiple CpG sites that are related to a specific gene. This avoids the informative sites to be averaged by the other non-informative ones. We projected the data over KEGG pathways implicated in schizophrenia, including “Neurotrophin signaling pathway”, “Dopaminergic synapse”, “Serotonergic synapse”, “Axon guidance”, “GABAergic synapse” and “ErbB signaling pathway” (Brisch et al. 2014).

3. Results

No significantly differentially methylated regions (DMR) were identified in the bumphunter analysis tool using parameters mentioned in the Method section and a cutoff threshold of 0.2. To get any significant result, we had to lower the cutoff threshold down to 0.05. Using this parameter, we obtained 10 regions, with half of them located on chromosome 6, covering different HLA class II beta chain paralogs. Other regions called by bumphunter included the genes VAX1, OTX2, HOOK2, ROPN1B and VTRNA2–1. The differentially methylated regions, identified with the decreased cutoff are listed in Table 2.

Table 2 -.

list of differentially methylated regions called by bumphunter

| Chrom. | Start-End | Neighboring gene | Number of probes | p-val. | Average beta values for cases / controls | SD of beta values for cases / controls |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chr3 | 125708958–125709740 | ROPN1B | 6 | 0.008 | 0.2433 / 0.3224 | 0.1604 / 0.1708 |

| Chr5 | 135416205–135416613 | VTRNA2–1 | 10 | 0.004 | 0.4785 / 0.4132 | 0.1828 / 0.2161 |

| Chr19 | 12876846–12877188 | HOOK2 | 4 | 0.01 | 0.3580 / 0.4340 | 0.1778 / 0.17 |

| Chr6 | 32606845–32607224 | HLA-DQA1 | 4 | 0.02 | 0.5527 / 0.4857 | 0.2302 / 0.2137 |

| Chr6 | 32549139–32549361 | HLA-DRB1 | 3 | 0.02 | 0.6255 / 0.5491 | 0.1998 / 0.2276 |

| Chr6 | 33033176–33033484 | HLA-DPA1 | 3 | 0.03 | 0.7730 / 0.7015 | 0.1607 / 0.2027 |

| Chr10 | 118892211–118892869 | VAX1 | 4 | 0.04 | 0.3116 / 0.3665 | 0.1021 / 0.1048 |

| Chr14 | 57276789–57277366 | OTX2 | 4 | 0.04 | 0.4163 / 0.4709 | 0.0639 / 0.0760 |

| Chr6 | 32526021–32526260 | HLA-DRB5 | 3 | 0.04 | 0.5810 / 0.5156 | 0.3014 / 0.3054 |

| Chr6 | 32546743–32547167 | HLA-DRB5 | 3 | 0.04 | 0.4450 / 0.3801 | 0.1672 / 0.1473 |

In previous analyses, we have successfully applied our feature selection and classification method to identify combinatorial patterns of DNAm over age in healthy human brain based on data from the 27K HumanMethylation BeadChip (Torabi Moghadam et al. 2016). MCFS ranks the features by their Relative Importance (RI) score, which is a measurement of the contribution of features in the classification. This pipeline, however, did not return any significant features on this data set, i.e. CpG sites that contribute significantly in classifying schizophrenic and control samples. We thus chose the first 100 features ranked by their RI score, and used them to train our model. In order to compare the accuracy of the model, we repeated this procedure by selecting top 200, 300, … and 1000 ranked features and generating a classifier for each set. The best accuracy mean, calculated by a 10-fold cross validation was obtained for the model trained with the top 500 features. The rules in this classifier were filtered for their accuracy (over 95%) and their coverage (over 70%). Coverage shows the percentage of samples that each rule classifies, and helps avoiding rules that are too specific in the model. Using the filtered rules, we could classify the schizophrenic samples with conjunctive rules with average 20 conditions, but since none of the rules for the control class passed the filtering, the accuracy of the model dropped down to 60%, which is only slightly above the expectation of 50% for a random null model.

We also tried this method with different discretization of the beta values. In this experiment, we divided the intermediate range into two and three equal bins. Again, MCFS did not return any significant feature, and by generating the classifier with top ranked features, as before, we did not obtain a more accurate classifier.

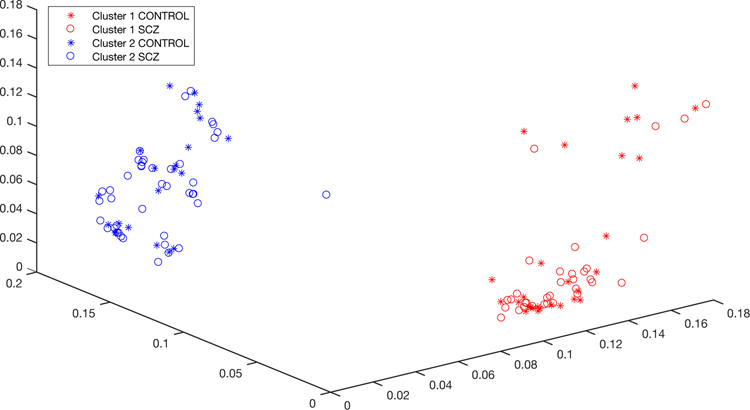

Our unsupervised learning method has been applied on the same type of array data; successfully detecting clusters matching with different cancer types and also subtypes of the same cancer in a different study (Torabi Moghadam et al., manuscript in preparation). In the present study, the algorithm grouped the samples into two clusters; however, as Figure 1 shows, the schizophrenic state is not the factor that separates them. The differentiating regions that make these clusters consist of 3 CpG sites at the upstream (possible promoter region) of the HLA-DRB1 gene, 3 sites located at one of its introns and 6 sites located at intronic parts of the HLA-DRB6 gene.

Figure 1.

methylSaguaro clusters the samples into two groups, where schizophrenic and control samples are mixed between clusters.

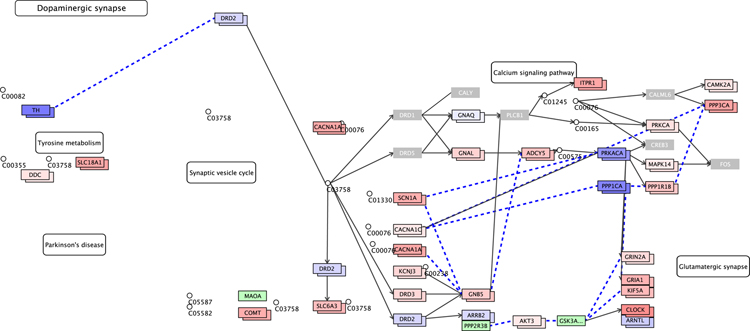

Furthermore, we utilized PiiL (Moghadam et al. 2017) which facilitates assessing DNAm patterns in the context of gene pathways or on a list of candidate genes. We projected the data over multiple pathways related to schizophrenia, mentioned in the Data Analysis section. As a representative example, we show in Figure 2 the KEGG’s “dopaminergic synapse” pathway, with color-coded methylation data generated using PiiL. Among various options for choosing a subset of all CpG sites that relate to a gene, we filtered out the CpG sites with a standard deviation (SD) lower than 0.05 over all samples. Genes that are shown in gray are the ones with no site passing the filter. Increasing the SD filter to 0.1 leaves only a few genes highlighted, indicating that for most of the genes the difference among the samples is very small. The genes colored in blue have a beta value close to zero and the color fades into white as the beta value approaches zero and turns from light red to darker red the closer beta value is to 1. The gray genes are the ones with no CpG site surviving the standard deviation filtering (or any other applied filter) and the genes in light green had no match with any of the annotated sites in the data.

Figure 2.

PiiL’s group-wise view for DNA methylation data projected on (part of) KEGG’s dopaminergic synapse pathway. The genes colored in gray show that they have no CpG site that has a standard deviation greater than 0.05 overall samples. The genes with two boxes show the average methylation level in schizophrenic (top box) versus average methylation level of control samples (underneath box), color-codes as blue for hypomethylation and red for hypermethylation. The genes in green did not get a match with any annotated CpG site in the data.

In PiiL’s “group-wise view”, for each of the matching genes in the pathway, the average methylation level of the samples with schizophrenia and the average methylation level of the controls are shown in two adjacent boxes. This visualization, which transforms the beta values to colors, facilitates the comparison of the two groups and confirms that there is no difference based on the schizophrenic versus control grouping in the dopaminergic synapse pathway, as shown in Figure 2.

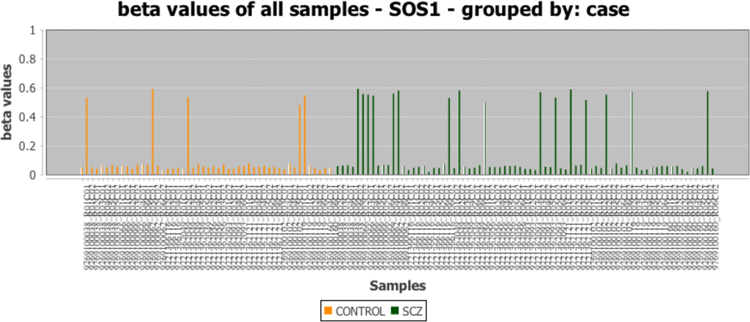

Using PiiL’s functionality, we could easily confirm that the differentiation in the highlighted genes is randomly distributed between the samples of both affected subjects and control group, i.e. for the highlighted genes there is no difference in average methylation between the two groups. For example, a single site in the SOS1 gene shows differential methylation between samples that survives our standard deviation threshold. However, while we could detect signals, none of them were linked to mental disease, with cases and controls being indistinguishable, and is likely a result of natural variation in the population (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

PiiL features enable rapid assessment of the data. There is a single intronic CpG site in SOS1 gene (a member of ErbB signaling pathway) that survives the standard deviation filtering and shows a differentiating pattern between samples, but the samples with a different methylation level are not overrepresented in neither the patient nor control groups.

The beta values for all individuals for the methylated regions described in Table 2 are submitted to the GEO repository (accession number: GSE128601).

4. Discussion

Our results suggest that there is no obvious link between DNAm and schizophrenia, at least not detectable with the samples and resolution of analysis used in the present study. It is well known that schizophrenia is highly genetically complex and heterogeneous, with recent genome-wide association studies (GWAS) yielding >100 loci explaining a minor fraction of the heritability (Schizophrenia Working Group of the Psychiatric Genomics 2014). A similar level of complexity and contribution to risk at the level of methylation would not be possible to detect unless a significantly larger sample size was used. Meanwhile, studies of gene expression in schizophrenia have highlighted genes and pathways that exhibit differential expression, using sample sizes in the tens to hundreds (Chang et al. 2017; Fromer et al. 2016). Our results indicate that simple methylation differences do not seem to account for these expression changes. Previous studies of methylation in schizophrenia have yielded conflicting results with little overlap between studies, and some have also indicated a lack of major differentially methylated sites between subjects diagnosed with schizophrenia and controls (Teroganova et al. 2016). Thus, while there is an observed component of family origin and risk of developing schizophrenia, both previous genetic studies and our results suggest that schizophrenia is highly complex and heterogeneous at both at the level of genetics and epigenetics.

Although, our analysis do not identify a clear association between methylation and schizophrenia, we noted a trend towards significant finding in the HLA-region. The finding is interesting since the HLA region is one of the most consistent positive finding in schizophrenia association studies. In addition, other bumps hit different regions of VAX1, OTX2, HOOK2, ROPN1B and VTRNA2–1. Of these, VAX1 and OTX2 are both important for normal brain development, with expression restricted to the brain. Mutations in these genes are associated with eye disorders as well as intellectual disability/developmental delay (Schilter et al. 2011; Slavotinek et al. 2012). VTRNA2–1 could also be of potential interest since strong allele specific imprinting is observed for this gene in several tissues, including brain tissue with hypermethylation of the maternal allele (Paliwal et al. 2013) and could be a possible link between environmental factors and schizophrenia. In addition, VTRNA2–1 has previously been shown to display methylation differences associated with season of birth (Silver et al. 2015). An association between season of birth and risk for schizophrenia is a well established and robust finding in epidemiological studies (Davies et al. 2003). Unfortunately, we do not have date of birth information for the individuals included in this study, and can therefore cannot exclude that the trend we see is actually a results of differences in birth season between patients and controls.

We cannot rule out that current technology limits the sensitivity of detecting subtle changes in methylation. The current analysis was performed on bulk frontal cortex tissue, which contains a range of different cell types. In addition we do not have information regarding the layers from which the samples are derived. Single cell methylation analysis might provide more detailed information about cell type specific changes. Whole genome bisulfite re-sequencing would also increase the resolution of analysis by covering all CpG sites in the genome and not only the ones represented on the 450k array. Given the success of the analysis methods applied to other areas, such as ageing or DNAm changes in cancer, it is unlikely that the lack of signal is due to inadequate data processing. Therefore, any potential methylation signals are rather weak and below detection levels. In practical terms, our results suggest that methylation is not a viable target for treatment of schizophrenia in the near future.

We examined the data using three proven methods, yet yielding no conclusive results with regards to how schizophrenia might be linked to aberrant or different patterns in DNAm.

While we cannot rule out that schizophrenia might be linked to altered methylation, the apparent absence of a strong connection might give valuable insights into the onset, progression and treatment of schizophrenia: the DNAm status of any given CpG site is not necessarily permanent, yet extremely difficult to alter from the outside of a cell, in particular when targeting a specific type of cells.

In conclusion, we expect that our findings with regards to schizophrenia and DNAm, albeit negative on the surface, will contribute to future research.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgement

We thank Harvard Brain Tissue Resource Center, which is supported in part by PHS grant number R24 MH068855, the MRC London neurodegenerative diseases brain bank, and MRS Sudden Death Brain & Tissue bank for the tissue donations. Brain tissues were also provided by the Postmortem Brain Core of the NIH/COBRE Center for Psychiatric Neuroscience (P30 GM103328), University of Mississippi Medical Center (UMMC). UMMC acknowledges the contributions of Drs. James Overholser, George Jurjus and Herbert Y. Meltzer, and of Lesa Dieter and Gouri Mahajan in psychiatric assessments and tissue dissection, and deeply appreciates the contributions made by the families consenting to donate brain tissue and be interviewed. The support of the Cuyahoga County Medical Examiner’s Office, Cleveland, OH, USA, is also acknowledged. Sequencing was performed using the SciLifeLab National Genomics Infrastructure at Uppsala Genome Center and the Uppsala SNP & SEQ Facility. Computational analyses were performed on resources provided by SNIC through Uppsala Multidisciplinary Center for Advanced Computational Science (UPPMAX). MGG was supported by the Swedish Research Council FORMAS. BT and JK were supported by a contract from FORMAS; JK was supported in part by an eSSENCE grant and in part by a grant from the Polish National Science Centre [DEC-2015/16/W/NZ2/00314]. Sample preparation and methylation analysis was funded by European Research Council ERC Starting Grant Agreement n. 282330 (to LF) and by a grant from Marcus Borgström’s foundation, Uppsala University (ELC).

Abbreviations:

- DNAm

DNA methylation

- MCFS

Monte Carlo Feature Selection

- CpG

Cytosine-phosphate-Guanine

- DMR

Deferentially Methylated Region

References

- Arseneault Louise, Cannon Mary, Fisher Helen L., Polanczyk Guilherme, Moffitt Terrie E., and Caspi Avshalom. 2011. ‘Childhood trauma and children’s emerging psychotic symptoms: A genetically sensitive longitudinal cohort study’, The American Journal of Psychiatry, 168: 65–72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aryee MJ, Jaffe AE, Corrada-Bravo H, Ladd-Acosta C, Feinberg AP, Hansen KD, and Irizarry RA. 2014. ‘Minfi: a flexible and comprehensive Bioconductor package for the analysis of Infinium DNA methylation microarrays’, Bioinformatics, 30: 1363–69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brisch R, Saniotis A, Wolf R, Bielau H, Bernstein HG, Steiner J, Bogerts B, Braun K, Jankowski Z, Kumaratilake J, Henneberg M, and Gos T. 2014. ‘The role of dopamine in schizophrenia from a neurobiological and evolutionary perspective: old fashioned, but still in vogue’, Front Psychiatry, 5: 47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown Alan S., and Derkits Elena J.. 2010. ‘Prenatal infection and schizophrenia: a review of epidemiologic and translational studies’, The American Journal of Psychiatry, 167: 261–80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cantor-Graae Elizabeth, and Selten Jean-Paul. 2005. ‘Schizophrenia and migration: a meta-analysis and review’, The American Journal of Psychiatry, 162: 12–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang X, Liu Y, Hahn CG, Gur RE, Sleiman PMA, and Hakonarson H. 2017. ‘RNA-seq analysis of amygdala tissue reveals characteristic expression profiles in schizophrenia’, Transl Psychiatry, 7: e1203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davies G, Welham J, Chant D, Torrey EF, and McGrath J. 2003. ‘A systematic review and meta-analysis of Northern Hemisphere season of birth studies in schizophrenia’, Schizophr Bull, 29: 587–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dempster E, Viana J, Pidsley R, and Mill J. 2013. ‘Epigenetic studies of schizophrenia: progress, predicaments, and promises for the future’, Schizophr Bull, 39: 11–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Draminski M, Rada-Iglesias A, Enroth S, Wadelius C, Koronacki J, and Komorowski J. 2008. ‘Monte Carlo feature selection for supervised classification’, Bioinformatics, 24: 110–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fromer M, Roussos P, Sieberts SK, Johnson JS, Kavanagh DH, Perumal TM, Ruderfer DM, Oh EC, Topol A, Shah HR, Klei LL, Kramer R, Pinto D, Gumus ZH, Cicek AE, Dang KK, Browne A, Lu C, Xie L, Readhead B, Stahl EA, Xiao J, Parvizi M, Hamamsy T, Fullard JF, Wang YC, Mahajan MC, Derry JM, Dudley JT, Hemby SE, Logsdon BA, Talbot K, Raj T, Bennett DA, De Jager PL, Zhu J, Zhang B, Sullivan PF, Chess A, Purcell SM, Shinobu LA, Mangravite LM, Toyoshiba H, Gur RE, Hahn CG, Lewis DA, Haroutunian V, Peters MA, Lipska BK, Buxbaum JD, Schadt EE, Hirai K, Roeder K, Brennand KJ, Katsanis N, Domenici E, Devlin B, and Sklar P. 2016. ‘Gene expression elucidates functional impact of polygenic risk for schizophrenia’, Nat Neurosci, 19: 1442–53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gagliano SA, Ptak C, Mak DYF, Shamsi M, Oh G, Knight J, Boutros PC, and Petronis A. 2016. ‘Allele-Skewed DNA Modification in the Brain: Relevance to a Schizophrenia GWAS’, Am J Hum Genet, 98: 956–62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horváth Szatmár, Janka Zoltán, and Mirnics Károly. 2011. ‘Analyzing schizophrenia by DNA microarrays’, Biological Psychiatry, 69: 157–62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jaffe AE, Gao Y, Deep-Soboslay A, Tao R, Hyde TM, Weinberger DR, and Kleinman JE. 2016. ‘Mapping DNA methylation across development, genotype and schizophrenia in the human frontal cortex’, Nature Neuroscience, 19: 40-+. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jakovcevski Mira, and Akbarian Schahram. 2012. ‘Epigenetic mechanisms in neurological disease’, Nature Medicine, 18: 1194–204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Komorowski Jan, Øhrn Aleksander, and Skowron Andrzej. 2002. “Case studies: public domain, multiple mining tasks systems: ROSETTA rough sets” In Handbook of data mining and knowledge discovery, 554–59. Oxford University Press, Inc. [Google Scholar]

- Labrie Viviane, Pai Shraddha, and Petronis Arturas. 2012. ‘Epigenetics of major psychosis: progress, problems and perspectives’, Trends in genetics: TIG, 28: 427–35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee SA, and Huang KC. 2016. ‘Epigenetic profiling of human brain differential DNA methylation networks in schizophrenia’, BMC Med Genomics, 9: 68. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKinney B, Ding Y, Lewis DA, and Sweet RA. 2017. ‘DNA methylation as a putative mechanism for reduced dendritic spine density in the superior temporal gyrus of subjects with schizophrenia’, Translational Psychiatry, 7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mill Jonathan, Tang Thomas, Kaminsky Zachary, Khare Tarang, Yazdanpanah Simin, Bouchard Luigi, Jia Peixin, Assadzadeh Abbas, Flanagan James, Schumacher Axel, Wang Sun-Chong, and Petronis Arturas. 2008. ‘Epigenomic profiling reveals DNA-methylation changes associated with major psychosis’, American Journal of Human Genetics, 82: 696–711. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moghadam BT, Zamani N, Komorowski J, and Grabherr M. 2017. ‘PiiL: visualization of DNA methylation and gene expression data in gene pathways’, BMC Genomics, 18: 571. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Montano C, Taub MA, Jaffe A, Briem E, Feinberg JI, Trygvadottir R, Idrizi A, Runarsson A, Berndsen B, Gur RC, Moore TM, Perry RT, Fugman D, Sabunciyan S, Yolken RH, Hyde TM, Kleinman JE, Sobell JL, Pato CN, Pato MT, Go RC, Nimgaonkar V, Weinberger DR, Braff D, Gur RE, Fallin MD, and Feinberg AP. 2016. ‘Association of DNA Methylation Differences With Schizophrenia in an Epigenome-Wide Association Study’, JAMA Psychiatry, 73: 506–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moore Theresa H. M., Zammit Stanley, Anne Lingford-Hughes Thomas R. E. Barnes, Jones Peter B., Burke Margaret, and Lewis Glyn. 2007. ‘Cannabis use and risk of psychotic or affective mental health outcomes: a systematic review’, The Lancet, 370: 319–28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Øhrn Aleksander, and Komorowski Jan. 1997. “Rosetta--a rough set toolkit for analysis of data.” In Proc. Third International Joint Conference on Information Sciences Citeseer. [Google Scholar]

- Paliwal A, Temkin AM, Kerkel K, Yale A, Yotova I, Drost N, Lax S, Nhan-Chang CL, Powell C, Borczuk A, Aviv A, Wapner R, Chen X, Nagy PL, Schork N, Do C, Torkamani A, and Tycko B. 2013. ‘Comparative anatomy of chromosomal domains with imprinted and non-imprinted allele-specific DNA methylation’, PLoS Genet, 9: e1003622. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pedersen CB, and Mortensen PB. 2001. ‘Evidence of a dose-response relationship between urbanicity during upbringing and schizophrenia risk’, Archives of General Psychiatry, 58: 1039–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pidsley R, Viana J, Hannon E, Spiers H, Troakes C, Al-Saraj S, Mechawar N, Turecki G, Schalkwyk LC, Bray NJ, and Mill J. 2014. ‘Methylomic profiling of human brain tissue supports a neurodevelopmental origin for schizophrenia’, Genome Biology, 15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rujescu Dan. 2012. ‘Schizophrenia genes: on the matter of their convergence’, Current Topics in Behavioral Neurosciences, 12: 429–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruzicka WB, Subburaju S, and Benes FM. 2017. ‘Variability of DNA Methylation within Schizophrenia Risk Loci across Subregions of Human Hippocampus’, Genes, 8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schilter KF, Schneider A, Bardakjian T, Soucy JF, Tyler RC, Reis LM, and Semina EV. 2011. ‘OTX2 microphthalmia syndrome: four novel mutations and delineation of a phenotype’, Clin Genet, 79: 158–68. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schizophrenia Working Group of the Psychiatric Genomics, Consortium. 2014. ‘Biological insights from 108 schizophrenia-associated genetic loci’, Nature, 511: 421–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silver MJ, Kessler NJ, Hennig BJ, Dominguez-Salas P, Laritsky E, Baker MS, Coarfa C, Hernandez-Vargas H, Castelino JM, Routledge MN, Gong YY, Herceg Z, Lee YS, Lee K, Moore SE, Fulford AJ, Prentice AM, and Waterland RA. 2015. ‘Independent genomewide screens identify the tumor suppressor VTRNA2–1 as a human epiallele responsive to periconceptional environment’, Genome Biol, 16: 118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Slavotinek AM, Chao R, Vacik T, Yahyavi M, Abouzeid H, Bardakjian T, Schneider A, Shaw G, Sherr EH, Lemke G, Youssef M, and Schorderet DF. 2012. ‘VAX1 mutation associated with microphthalmia, corpus callosum agenesis, and orofacial clefting: the first description of a VAX1 phenotype in humans’, Hum Mutat, 33: 364–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takizawa T, Nakashima K, Namihira M, Ochiai W, Uemura A, Yanagisawa M, Fujita N, Nakao M, and Taga T. 2001. ‘DNA methylation is a critical cell-intrinsic determinant of astrocyte differentiation in the fetal brain’, Developmental Cell, 1: 749–58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teroganova N, Girshkin L, Suter CM, and Green MJ. 2016. ‘DNA methylation in peripheral tissue of schizophrenia and bipolar disorder: a systematic review’, BMC Genet, 17: 27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Torabi Moghadam B, Dabrowski M, Kaminska B, Grabherr MG, and Komorowski J. 2016. ‘Combinatorial identification of DNA methylation patterns over age in the human brain’, BMC Bioinformatics, 17: 393. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walton Esther, Hass Johanna, Liu Jingyu, Roffman Joshua L., Bernardoni Fabio, Roessner Veit, Kirsch Matthias, Schackert Gabriele, Calhoun Vince, and Ehrlich Stefan. 2016. ‘Correspondence of DNA Methylation Between Blood and Brain Tissue and Its Application to Schizophrenia Research’, Schizophrenia Bulletin, 42: 406–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zamani N, Russell P, Lantz H, Hoeppner MP, Meadows JRS, Vijay N, Mauceli E, di Palma F, Lindblad-Toh K, Jern P, and Grabherr MG. 2013. ‘Unsupervised genome-wide recognition of local relationship patterns’, Bmc Genomics, 14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu H, Urban DJ, Blashka J, McPheeters MT, Kroeze WK, Mieczkowski P, Overholser JC, Jurjus GJ, Dieter L, Mahajan GJ, Rajkowska G, Wang ZF, Sullivan PF, Stockmeier CA, and Roth BL. 2012. ‘Quantitative Analysis of Focused A-To-I RNA Editing Sites by Ultra-High-Throughput Sequencing in Psychiatric Disorders’, Plos One, 7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.