Abstract

Disinhibition, mainly caused by damage in frontotemporal brain regions, is one of the major causes of caregiver distress in neurodegenerative dementias. Behavioural inhibition deficits are usually described as a loss of social conduct and impulsivity, whereas cognitive inhibition deficits refer to impairments in the suppression of prepotent verbal responses and resistance to distractor interference.

In this review, we aim to discuss inhibition deficits in neurodegenerative dementias through behavioural, cognitive, neuroanatomical and neurophysiological exploration. We also discuss impulsivity and compulsivity behaviours as related to disinhibition. We will therefore describe different tests available to assess both behavioural and cognitive disinhibition and summarise different manifestations of disinhibition across several neurodegenerative diseases (behavioural variant of frontotemporal dementia, Alzheimer's disease, Parkinson's disease, progressive supranuclear palsy, Huntington's disease). Finally, we will present the latest findings about structural, metabolic, functional, neurophysiological and also neuropathological correlates of inhibition impairments. We will briefly conclude by mentioning some of the latest pharmacological and non pharmacological treatment options available for disinhibition.

Within this framework, we aim to highlight i) the current interests and limits of tests and questionnaires available to assess behavioural and cognitive inhibition in clinical practice and in clinical research; ii) the interpretation of impulsivity and compulsivity within the spectrum of inhibition deficits; and iii) the brain regions and networks involved in such behaviours.

Keywords: Disinhibition, Behavioural variant of frontotemporal dementia (bvFTD), Alzheimer's disease (AD), Inhibition assessment, Brain correlates

1. Introduction

1.1. Definition

“All the movements of our body are not merely those dictated by impulse or weariness; they are the correct expression of what we consider decorous. Without impulses, we could take no part in social life; on the other hand, without inhibitions, we could not correct, direct, and utilize our impulses”. (Maria Montessori).

Defining cognitive and behavioural inhibition is a complex task. In 2013, Bari and Robbins (2013) published a large and comprehensive review on inhibition and impulsivity and they listed 18 types of “inhibition” belonging to different levels of “analysis”. These types ranged from more fundamental aspects, such as synaptic inhibition like neuronal hyperpolarisation mediated by GABA fixation for example, to more complex inhibition mechanisms, such as social inhibition.

From a neuropsychological and clinical point of view, two major types can be defined: cognitive and behavioural inhibition (Aron, 2007). They are both part of the ‘cognitive control’ system, an umbrella term to define a range of inhibitory mechanisms from the inhibition of prepotent tendencies, to the updating of working memory contents and consequential shifting between tasks (Miyake et al., 2000). This division may seem artificial, but it reflects the need to distinguish the observed phenomena from a clinical standpoint. In agreement with such a division, in obsessive compulsive disorders, for example, failures in cognitive or behavioural inhibitory processes lead to different syndromic behaviours: obsessions and compulsions respectively (Chamberlain et al., 2005). From a neurodevelopmental perspective, behavioural inhibition, such as the ability to control movements, appears to develop before cognitive inhibition, which acts on mental processes (Wilson & Kipp, 1998). Both cognitive and behavioural inhibition appear to then become increasingly efficient with age (Mischel et al., 1989; Olson, 1989; Harnishfeger, 1995).

In an attempt to keep this distinction, cognitive inhibition is defined as the ability to resist an exogenous or endogenous interference, inhibit cognitive contents or processes previously activated and suppress inappropriate or irrelevant responses (Wilson & Kipp, 1998). It can be intentional and conscious (such as thought suppression), or unintentional and unconscious (such as the gating of irrelevant information from working memory during memory processing) (Harnishfeger, 1995). Behavioural inhibition, on the other hand, refers to the control of emotional and social behaviours in a social context. It is the control of overt behaviours, the ability to adapt actions to environmental changes, and suppress impulsions which violate norms (Harnishfeger, 1995).

1.2. Disinhibition, impulsivity and compulsivity: nested concepts related to inhibition deficits

For some authors (e.g., Rascovsky et al., 2011), impulsivity is a subcomponent of the larger syndrome of disinhibition. Conversely, for other authors (e.g., Rochat et al., 2013), disinhibition, referring to the lack of control in a specific social context, is a subdimension of the broader concept of impulsive behaviours. While impulsivity was historically associated with risk-seeking and compulsivity with harm-avoidance, it is progressively recognised that the two concepts share neuropsychological mechanisms involving dysfunctional inhibition of thoughts and behaviours.

Impulsivity is a multidimensional construct defined as “a predisposition toward rapid, unplanned reactions to internal or external stimuli with diminished regard to the negative consequences of these reactions” (Chamberlain & Sahakian, 2007). It is measured through questionnaires as a trait (e.g., Barratt Impulsiveness Scale (BIS-11) (Patton et al., 1995)) or through tasks (e.g., Go/NoGo task). This reflects the different facets of impulsive behaviour, which is characterised as the (i) inability to stop automatic responses, (ii) tendency towards quick choices and decision-making, (iii) difficulty to delay gratification (Averbeck et al., 2014). Impulsivity and compulsivity share the feeling of “lack of control” (Fineberg et al., 2014, Stein & Hollander, 1995). While impulsivity describes quick unplanned actions, compulsivity is defined as persistent non-goal orientated actions and is typically assessed through tasks measuring an inability to flexibly adapt behaviours and/or switch attention between stimuli (Ahearn et al., 2012; Fineberg et al., 2014, 2018).

2. Assessing inhibition deficits

For each test and questionnaire, we have described the instructions, the ability to identify cognitive or behavioural inhibition disorders and to differentiate dementia syndromes. Table 1 summarises this information.

Table 1.

Main available tests and scales measuring disinhibition in neurodegenerative dementias.

| Inhibition type | Tests/Scales | Measures of disinhibition | Discrimination patients vs. controls (whole test) | Discrimination within dementia syndromes (whole test) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cognitive | Stroop | Errors; Latency to complete | bvFTD, AD, PD | b |

| Hayling | Errors; Latency to complete | bvFTD, AD, PD | bvFTD < AD bvFTD < PD |

|

| TMT | Errors; Latency to complete | bvFTD, AD | bvFTD < AD | |

| WCST | Perseverative Errors | bvFTD, AD | bvFTD < AD | |

| Go/No-go | Errors; Reaction time | bvFTD, AD, PD, PSP | b | |

| Stop signal | Stop signal reaction time | AD, PD | b | |

| Graphic alternating pattern | Frequency of perseverations | bvFTD, AD | b | |

| Behavioural | NPI | Frequency score, severity score, impact on the caregiver score | FTD, ADa, PSPa, HDa | FTD < ADa PSP < PDa |

| MFS | Presence/absence | b | FTD < AD | |

| FBI | 4-point scale frequency | FTD | FTD < ADa bvFTD < PSPa | |

| DAPHNE | 5-point scale severity | bvFTD | bvFTD < AD bvFTD < PSP | |

| CBI & Short-CBI | 4-point scale frequency | b | FTD < ADa bvFTD < PD&HD AD < PD&HD bvFTD < PSPa |

|

| FTLD-CDR | 5-point scale severity | FTD | b | |

| FrSBe | 5-point scale frequency | FTD | FTD < ADa |

AD: Alzheimer's disease; bvFTD: behavioural variant of Frontotemporal dementia; CBI: Cambridge Behavioural Inventory; FBI: Frontal Behavioural Inventory; FrSBe: Frontal System Behavioural scale; FTD: frontotemporal dementia; FTLD-CDR: Frontotemporal Lobar Degeneration modified Clinical Dementia Rating scale; HD: Huntington's disease; MFS: Middleheim Frontality Score; NPI: Neuropsychiatric Inventory; PD: Parkinson's disease; PSP: Progressive supranuclear palsy; TMT: Trail Making Test; WCST: Wisconsin Card Sorting Test.

x < y: x patients perform poorer the test/show more abnormalities than y patients.

Discrimination shown for the disinhibition subscale.

Comparison not specifically assessed in the publication.

2.1. Cognitive inhibition

In neuropsychological practice, there are a number of tests that are performed routinely. The Stroop, the Hayling, the Trail Making and the Wisconsin card sorting tests are amongst the most used (O’Callaghan, Hodges, & Hornberger, 2013; Rabin et al., 2005).

The Stroop Colour Word Interference test (Stroop, 1935), usually named Stroop test, is a test in which colour words are written in a different coloured ink to the colour they refer to. Participants are asked to identify and name the colour in which words are written, suppressing the automatic response to read the words themselves (Matías-Guiu et al., 2019). Behavioural variant of frontotemporal dementia (bvFTD) and Alzheimer's disease (AD) patients perform significantly less well on the Stroop test than controls, but there is a poor differentiation between these two diseases (Collette et al., 2007; Perry & Hodges, 2000).

One of the most sensitive standard tests for measuring inhibition is the Hayling Sentence Completion Task (HSCT; Burgess & Shallice, 1996; O’Callaghan, Hodges, & Hornberger, 2013), often referred to as Hayling Test. This test measures response initiation and inhibition of response by a sentence completion task. In the first part (part A), subjects must complete a sentence in an automatic condition, with an appropriate word (e.g., for « The rich child attended a public … », the correct answer is « school»). In the second part of the test (part B), subjects must complete a sentence in an inhibition condition, with an inappropriate word, requiring inhibition of the automatic answer (e.g., for « London is a very lively … », « city » is considered an incorrect answer, but « banana » would be considered correct). Errors in part B are recorded and form an error score, while times to complete part A (initiation time) and part B (initiation + inhibition time) are also recorded. Together, these measures can be computed to form an overall score of cognitive inhibition (Burgess & Shallice, 1996; Santillo et al., 2016; Matías-Guiu et al., 2019). Impaired performances are demonstrated in bvFTD and AD patients (Collette et al., 2009; Hornberger et al., 2008), with poorer performances in bvFTD patients (Hornberger et al., 2010), as well as in pre-symptomatic C9orf72 carriers with high risk of developing bvFTD (Montembeault et al., 2020).

Both the Stroop and Hayling tests rely on the suppression of prepotent verbal responses and resistance to distractor interference. However, in healthy subjects, there is a positive correlation between the Hayling test and the Stroop test for response initiation but not for the inhibitory component (Jantscher et al., 2011; Santillo et al., 2016). These tests therefore measure a different dimension of inhibitory capacity (Santillo et al., 2016). It also appears that the Hayling test could be more discriminative than the Stroop test when comparing bvFTD and AD (O’Callaghan, Hodges, & Hornberger, 2013).

Another classical but less used test to assess cognitive inhibition specifically is the Trail Making Test (TMT; 1944). This is a quick and easy test in which participants are asked to connect numbers from 1 to 25 in ascending order in part A. In part B, participants must perform the same thing but this time, alternating between 2 series, a number series and a letter series (1-A-2-B-3-C…). Part B therefore requires inhibitory skills in order to switch from one series to another (Amieva et al., 2009). Thus, errors or slow performance in part B may be indicative of cognitive inhibition difficulties. A study showed that AD patients made more errors than healthy subjects, with mostly perseveration errors, due to impairments in flexibility and inhibition (Amieva et al., 1998).

Finally, the Wisconsin Card Sorting Test (WCST; Berg, 1948) is particularly used in the clinical field to measure working memory, planning skills and, more particularly, shifting abilities (Coulacoglou & Saklofske, 2017). Participants are asked to sort cards according to standard stimuli (their colour, shape or number) one at a time, but without any rules concerning the sorting criteria. The investigator chooses a classification criteria (sorting the cards according to their colour, form or number) but this is only revealed to participants by giving them feedback (“right” or “wrong”) on each trial. Regularly, the classification criterion is changed without any warning and the participant must notice according to the feedback received and adapt their sorting to the new sorting rule (Silva-Filho et al., 2007). Thus, this test assesses the ability to shift from one task to another and the principle measure of this ability is the number of perseveration errors, which assesses whether the subject can inhibit a routine response. This test allows differentiation between bvFTD and AD patients, with a higher number of perseveration errors in bvFTD patients (Gregory et al., 2002).

Another way to approach inhibition deficits on a more fundamental level is to explore its motor aspects through motor response inhibition tests. The Go/No-Go and the Stop Signal tasks were developed to measure motor response inhibition and therefore assess the underlying process required to cancel an intended movement (O’Callaghan, Hodges, & Hornberger, 2013).

Trials of the Go/No-Go task (Donders, 1969) assess processing speed, in the go trials, and response inhibition, in the no-go trials. In this task, one or several stimuli are designated as targets or “go trials” and one stimulus is designated as a nontarget or “no-go trial”. Stimuli can be visual targets on a screen or motor behaviours performed by an experimenter for example. Participants are asked to respond as fast and as accurately as possible for a go trial (pressing a button or performing the motor behaviour) but to inhibit their response when it is a no-go trial (Coulacoglou & Saklofske, 2017). Reaction times and number of errors are recorded. Depending on the Go/No-Go task used, reaction times have been found to discriminate bvFTD and AD patients from control subjects, whereas other studies have found that bvFTD patients show similar (Collette et al., 2007) or even better (Castiglioni et al., 2006) performances compared with AD patients.

A simple Go/No-Go task is found in the Frontal Assessment Battery (FAB, Dubois et al., 2000), which is commonly used in clinical practice. In this version of the task, participants are trained to give a particular response to a specific stimulus (e.g., tapping one time when the examiner taps twice), followed by learning a new association (e.g., not tapping when the examiner taps twice) during three more training trials. The Go/No-Go subtest of the FAB has shown good discrimination of bvFTD patients from age-matched controls. However, it was not able to discriminate between bvFTD and AD patients (Bertoux et al., 2013; Castiglioni et al., 2006).

The Stop Signal task, developed by the work of Logan and Cowan (1984), is a variant of the Go/No-Go task and is widely used to measure inhibition of prepotent responses. Participants must respond as quickly as possible to predetermined stimuli, the “go trials”. On some trials, the go stimulus is followed by a stop signal (auditory signal for example) after a variable Stop Signal Delay (SSD): in that case, participants are asked to inhibit their already initiated responses. Speed and accuracy on the go trials are measured, as well as the stop signal reaction time (SSRT) (Friedman & Miyake, 2004; McMorris, 2016; Gervais et al., 2017). Using this test, Amieva and collaborators showed that AD patients show greater impairment in the Stop Signal task than in the Go/No-Go task (Amieva et al., 2002).

Finally, the Graphic Alternating Patterns test consists in copying graphic alternating patterns and measures the number of perseverations. Patients are asked, for example, to copy four double loops and a line with alternating peaks and plateaus. Frequency of perseveration in alternating lines and loops was higher in bvFTD and AD, in comparison to healthy subjects (Matías-Guiu et al., 2019), as well as the derived rule violations score (Possin et al., 2009).

2.2. Behavioural inhibition

Standardised caregiver questionnaires used in the behavioural assessment of neurodegenerative diseases often contain subscales related to disinhibition. Behavioural questionnaires to measure disinhibition are an important contribution to the clinical interview and, in some cases, allow discrimination between neurodegenerative diseases.

The Neuro-Psychiatric Inventory (Cummings et al., 1994) consists in an interview with the caregiver to assess 12 behavioural disturbances occurring in dementia patients, including disinhibition, agitation/aggression, aberrant motor activity and appetite disturbances (Boutoleau-Bretonnière et al., 2013; Cummings et al., 1994). The frequency, the severity and the impact on the caregiver are determined. This scale is mostly used in AD (Vercelletto et al., 2006) but is also useful in discriminating between FTD and AD, with FTD patients showing higher scores on the disinhibition subscale (Boutoleau-Bretonnière et al., 2012; Levy et al., 1996).

Another clinical and behavioural assessment tool is the Middleheim Frontality Score (MFS; Deyn et al., 2005) constituted of 10 items including disinhibition, impaired emotional control or stereotyped behaviours (Deyn et al., 2005). This quick and easy tool reliably discriminates FTD from AD patients, however, as it only considers the presence or absence of a behaviour, it does not allow the follow-up of patients (Boutoleau-Bretonnière et al., 2013).

The Frontal Behavioural Inventory (Kertesz et al., 1997) is a questionnaire designed for FTD patients to capture both behavioural and personality changes and includes 24 items specific to the disease. Twelve items represent positive symptoms involving diminished inhibition such as perseverations, excessive jocularity, poor judgment, inappropriateness, aggressiveness, impulsivity or hyperorality and each item is scored on a four-point scale (Kertesz et al., 1997; Santillo et al., 2016). The FBI is more specific for “prefrontal” disturbances than more general behavioural rating scales such as the NPI (Santillo et al., 2016) and allows good discrimination between FTD and AD patients (Kertesz et al., 2003; Vercelletto et al., 2006).

Another and more recent tool specialised in the assessment of bvFTD patients is the DAPHNE scale, consisting of ten items spread across six domains; disinhibition, apathy, perseverations, hyperorality, personal neglect and loss of empathy (Boutoleau-Bretonnière et al., 2015). Within disinhibition, there are 4 items, each scored from 0 to 4 with specific examples to guide the caregiver. This efficient scale has demonstrated more relevant psychometric properties than FBI with a specificity and a sensitivity of 92% (Boutoleau-Bretonnière et al., 2015).

The Cambridge Behavioural Inventory (CBI; Bozeat et al., 2000) is an 81-item questionnaire completed by a caregiver, divided into 13 subsections scored on a four-point scale (Wedderburn et al., 2008). This classic tool is useful to distinguish AD and FTD, particularly using items of disinhibition-related behaviours. The occurrence of behaviours is assessed rather than the intensity, which is in contrast to the NPI which includes both measures (Boutoleau-Bretonnière et al., 2013). This scale is very complete but is also lengthy. Wear et al. (2008) successfully developed a shorter version of 45 items in 2008 which is still able to differentiate bvFTD and AD from Parkinson's disease (PD), Huntington Disease (HD) and healthy subjects.

A less used test is the Frontotemporal Lobar Dementia Modified Clinical Dementia Rating Scale (FTLD-modified CDR scale, Knopman et al., 2008). This scale is a modified version of the CDR scale (Morris, 1993) but with two additional domains: “Language”, and “Behaviour, Comportment, Personality”. This last domain assesses socially inappropriate behaviours on a four-point scale (Knopman et al., 2008). This scale is a reliable tool for defining disease severity in FTD (Johnen & Bertoux, 2019) but the behavioural assessment of disinhibition remains rather succinct (Boutoleau-Bretonnière et al., 2013).

Finally, the Frontal System Behavioural scale (FrSBe; Grace & Malloy, 2001) is a 46-item behaviour rating scale designed to measure behaviours associated with damage to the frontal system with subscales measuring apathy, disinhibition and executive dysfunction in approximately 10 min (Grace & Malloy, 2001; Malloy et al., 2007). Behaviours are assessed before and after the illness, which is useful to quantify changes over time. Fifteen items are included as representative of disinhibition and are scored on a five-point scale. Some studies have found different neuroanatomical correlates of disinhibition in FTD by using the NPI (Rosen et al., 2005; Hornberger et al., 2011) or the FrSBe (Zamboni et al., 2008) (see also subsection 6 on brain correlates), which may reflect differences in sensitivity between these two tests for disinhibition measurement (O’Callaghan, Hodges, & Hornberger, 2013).

Overall, studies using questionnaires such as NPI, CBI or FrSBe have found that behaviours related to disinhibition (especially inappropriate behaviours, impulsive motor/verbal actions and ritualistic routines) were significantly higher in FTD patients compared to AD patients (Levy et al., 1996; Bozeat et al., 2000; Wedderburn et al., 2008; O’Callaghan, Hodges, & Hornberger, 2013).

2.3. Current limits in assessing disinhibition deficits in clinical practice and clinical research

The first obvious limitation in assessing disinhibition deficits in clinical practice concerns the administration of questionnaires to the caregiver. Given the typical anosognosia in patients, especially those with bvFTD, caregivers are often asked to provide insight into behavioural changes of patients. However, this presents a non-negligible bias. The second limitation is the fact that these tools for diagnosis, evaluation, and follow-up assessments are mostly written tests which lack ecological validity and sometimes are even limited in their cultural validity in non-western populations (see for example Kohli & Kaur, 2006, on WCST). There is therefore an important gap within this field of research which requires reliable and effective methods to assess behavioural symptoms, for example through performance-based testing (Johnen & Bertoux, 2019). In this vein, we very recently proposed a semi-ecological paradigm to objectively identify and quantify another behavioural and cognitive symptom typical of dementia; apathy (Batrancourt et al., 2019). The study of disinhibition could also benefit from a similar approach, which is undoubtedly less biased in comparison to the aforementioned more “traditional” methods.

3. Inhibition deficits in behavioural variant frontotemporal dementia and Alzheimer's disease

3.1. Behavioural variant frontotemporal dementia (bvFTD)

In bvFTD patients, cognitive and behavioural inhibition is the most frequent and early impaired domain, reported in 46.2% of cases (Lindau et al., 2000). According to clinical criteria for bvFTD (Rascovsky et al., 2011), disinhibition, especially behavioural, is a core feature of the clinical syndrome. Its global frequency ranges from 46 (Lindau et al., 2000) to 76% (Rascovsky et al., 2011). It results in three main alterations: socially inappropriate behaviour, loss of manners or decorum, and impulsive, rash or careless actions. Socially inappropriate behaviour can manifest itself by “staring, inappropriate physical contact with strangers, inappropriate sexual behaviour, verbal or physical aggression”. Loss of manners or decorum consists in “lack of social etiquette, insensitive or due comments, preference for crass jokes and slapstick humour, inappropriate choice of clothing or gifts”. Impulsive, rash or careless actions are represented by “new gambling behaviour, driving or investing recklessly, overspending, gullibility to phishing/Internet scams” (Convery et al., 2019).

Some symptoms, including undue familiarity, disorganised behaviours, and sexual acting out, could be related to impaired mechanisms of cognitive control (Hornberger, Geng, & Hodges, 2011). In this context, law violations, as a possible surrogate of behavioural disinhibition, are frequently observed in bvFTD. These consist in “theft, traffic violations, physical violence, sexual harassment, trespassing, and public urination, thus reflecting mainly disruptive, impulsive actions” (Diehl-Schmid et al., 2013; Liljegren et al., 2015; Shinagawa et al., 2017). Patients with bvFTD commit law violations up to five times more often than AD patients. More rarely, disinhibition can also manifest itself as inappropriate/disinhibited sexual behaviours (Ahmed et al., 2018, Mendez and Shapira, 2013, Mendez and Shapira, 2014).

Paholpak (2016) suggests that disinhibited behaviours result from at least two mechanisms, some based on impaired social cognition (e.g., saying embarrassing things) and others associated with a more generalised impulsivity (e.g., laughing or crying too easily).

A lack of social cognition could lead to disinhibited behaviour in social conditions. BvFTD patients have impaired emotion recognition (Bertoux et al., 2012), particularly for anger and disgust (Lough et al., 2006), and are impaired in tests of theory of mind (ToM) (Gregory et al., 2002). This may partly explain abnormalities in interpersonal behaviour (like offensive comments or behaviours towards others), and difficulties to identify social violations. Social inappropriateness is thus often the first clinical sign of a neurodegenerative process (Desmarais et al., 2018). Finally, disruptive symptoms considered as the result of behavioural disinhibition are major predictors for caregiver distress in bvFTD (Cheng, 2017).

Behavioural disinhibition is found to worsen until intermediate stages of the disease and is then followed by a tendency for improvement in later phases, as shown in a recent study on 167 patients followed up a year assessed and rated through the NPI and FBI (Cosseddu et al., 2020). This is particularly relevant for the evaluation of outcomes in bvFTD therapeutic trials’ design: behavioural disinhibition cannot be a good marker of therapeutic efficacy given its progression.

Patients with bvFTD often present with deficits in executive functions, a term that encompasses various complex cognitive functions including cognitive inhibition (Perry & Hodges, 2000; Slachevsky et al., 2004; Hornberger et al., 2008; Krueger et al., 2009; Torralva et al., 2009 a,b). Errors in different cognitive tests (e.g., perseveration or rule violations) are considered representative of cognitive disinhibition and such performance assessments can aid in the diagnosis of bvFTD (Carey et al., 2008, Kramer et al., 2003, Libon et al., 2007, Thompson, 2005). Generally, decreased error sensitivity or insensitivity (frequency of uncorrected errors) in cognitive inhibition tasks is considered a highly sensitive index of bvFTD (Ranasinghe et al., 2016).

However, if we look for clear discriminative abilities, most tests used in clinical practice, such as the Stroop test, are not good enough (Hutchinson & Mathias, 2007; Perry & Hodges, 2000; Matías-Guiu et al., 2019). Only the Hayling test seems to be a good candidate to reliably distinguish between bvFTD and early AD patients, at least at the individual level (Hornberger et al., 2008, 2010; Ramanan et al., 2017). Among the different cognitive tests available, the Hayling Test is more fitted to real-life inhibitory demands, with the ability to suppress inappropriate words being a part of many social interactions. In bvFTD patients, it is found to be highly sensitive to cognitive inhibition impairments (Hornberger et al., 2011; Santillo et al., 2016; Matías-Guiu et al., 2019).

Very recently, using the Hayling test, we demonstrated that cognitive inhibition was amongst the first cognitive functions showing subtle changes in non-symptomatic individuals at risk for bvFTD due to carrying a C9orf72 mutation (C9+) (Montembeault et al., 2020). We found that C9+ individuals younger than 40 years had a higher error score (part B) but an equivalent completion time (part B - part A), compared to controls. C9+ individuals older than 40 years had both higher error scores and longer completion times. Completion time significantly predicted the estimated number of years to clinical conversion from pre-symptomatic to symptomatic phase in C9+ individuals (based on the average age at onset of affected relatives in the family).

3.2. Alzheimer's disease (AD)

Previous studies have reported that behavioural disinhibition is more characteristic of bvFTD than of AD (Levy et al., 1996; Mendez et al., 1998; Hirono et al., 1999; Kertesz et al., 2000; Bathgate et al., 2001; Nagahama et al., 2006). However, neuropsychiatric symptoms such as apathy, anxiety, and disinhibition can be core aspects of AD patients (Kumar et al., 1988), especially at middle/late stages (Kumfor et al., 2014). Approximately 30% of patients with AD show inappropriate social behaviours typically within 30–36 months of diagnosis (Craig et al., 2005). Disinhibited behaviours range from impulsive decisions and hypersexual comments or actions, to disproportionate jocularity and incongruous approach of strangers. Although uncommon as first symptoms, among alterations of social behaviour, disinhibition has been reported in 6.9% of cases, compared to 5% and 2% of social awkwardness and apathy at the beginning of the disease (Lindau et al., 2000). Social disinhibition seen in AD appears to be multifactorial and secondary to impaired social cognitive abilities (Desmarais et al., 2018), as already discussed for bvFTD (see subsection 4.1). Although AD patients are not impaired in tests of ToM (Gregory et al., 2002), abnormalities in recognition of basic emotions are frequently reported (Weiss et al., 2008), which could contribute to abnormal and inappropriate behaviours.

More rarely and at very early stages, AD patients may present with an atypical, bvFTD-like clinical profile. However, this presentation is characterised by a milder and more restricted behavioural profile than in bvFTD, with a high co-occurrence of memory dysfunction and dysexecutive abnormalities (Mendez et al., 2013), typical AD atrophy-pattern mainly centred around temporoparietal regions (Ossenkoppele et al., 2015) and cerebrospinal fluid biomarkers or post-mortem confirmation of AD pathology.

Regarding the association of such symptoms with AD severity, one of the most common tools for social/behavioural evaluation in dementia, the NPI (Cummings et al., 1994), has been used in combination with the CDR scale (Morris, 1993), which is a disease severity scale. Several NPI dimensions, but in particular apathy and disinhibition, are found to correlate with the CDR score (Kazui et al., 2016).

Inhibitory mechanisms play a crucial role in various domains of cognition, such as working memory, selective attention and shifting abilities, usually impaired in AD. In AD, a discrepancy in performance amongst different tests can be found, according to the type of inhibitory mechanisms affected. For example, controlled inhibition processes measured by the Stroop task appear to be affected, while the more automatic inhibition of return is relatively preserved, suggesting that inhibitory deficits are not the result of a general breakdown of inhibitory function (Amieva et al., 2004). Substantial effects of AD on tasks such as negative priming (Sullivan, Faust, & Balota, 1995; Amieva et al., 2002), which are not cognitively complex but do require controlled inhibition, support this hypothesis.

More recently, Kaiser et al (2018) conducted a meta-analysis of 64 studies to quantify the magnitude of impairment of inhibitory control in patients with AD compared with healthy subjects on different commonly used tasks (trail making, Stroop, stop signal, negative priming, inhibition of return, Hayling, Go/No-Go and antisaccade tests). Comparing two indexes, the response time and error rates, they found large differences between AD patients and controls in the basic inhibition conditions, with AD patients being slower and making more errors. However, similarly large differences were also present in many of the baseline control-conditions and a derived inhibition score (i.e., control-condition score–inhibition-condition score) suggested only a small difference for errors and not for the response time, with high variability across tasks and AD severity. Inhibition tasks (especially the error rate) can discriminate AD patients from controls well, suggesting a specific deterioration of inhibitory-control skills. However, further processes such as a general reduction in processing speed and other attentional processes contribute to AD patients' performance deficits observed on a variety of inhibitory-control tasks.

The Hayling test shows a great potential to discriminate patients, including AD patients, from controls (Nash et al., 2007). Another commonly used clinical test, the Trail-Making-Test part B, is able to show cognitive inhibition deficits and can discriminate between AD and bvFTD patients (Ranasinghe et al., 2016).

In summary, disinhibition is frequent in both bvFTD and AD, with greater social disinhibition in bvFTD and comparable generalised impulsivity in both diseases (Paholpak et al., 2016). However, using the Barratt Impulsiveness Scale (BIS-11), Mariano et al (2020) showed higher scores of impulsive behaviour in bvFTD patients than in AD patients and controls, but not with neuropsychological tests. Dealing with these behaviours is a hard and heavy challenge for caregivers, with cases of personal neglect or reduced self-care (Diogenes syndrome) (Finney & Mendez, 2017), sexists comments, overt aggression, and in more extreme situations, they can result in criminal charges or pathological gambling (Tondo et al., 2017).

3.3. Anatomopathology of disinhibition in AD and bvFTD

Few studies have analysed the occurrence of disinhibition in autopsy-confirmed cases. Prior studies were conducted without distinguishing among patients who exhibited disinhibition alone or a combination of apathy and disinhibition symptoms (Mendez et al., 2013; Léger & Banks, 2014).

Some authors highlighted the occurrence of disinhibition as a clinical presentation of bvFTD, but also of some AD cases and “phenocopy” patients with psychiatric disorders (e.g., addictive disorders, gambling disorder and kleptomania) similar to bvFTD (Miki et al., 2016). The “in vivo” differentiation of “true” bvFTD cases with FTLD pathology from mimicking cases is not always easy. Thus, these authors proposed the following features (among others) as markers of underlying FTLD pathology:

-

a)

“socially inappropriate behaviours can be frequently interpreted as contextually inappropriate behaviours prompted by environmental visual and auditory stimuli, in the framework of environmental dependency syndrome (Lhermitte, 1986). Taking a detailed history usually reveals various kinds of such behaviours in various situations in everyday life rather than the repetition of a single kind of behaviour (e.g., repeated shoplifting);

-

b)

a correlation between the distribution of cerebral atrophy and neurological and behavioural symptoms is usually observed, and the proportion of FTLD cases with right side-predominant cerebral atrophy may be higher in a psychiatric setting (“behavioural patients”) than a neurological setting (“cognitive patients”)”.

This last element highlights the so-called “right hemisphere bias” (see specific subsection 6.4, page 30) in the generation of disinhibited behaviours.

A recent study investigated whether different types of post-mortem neuropathology in 887 patients with clinical diagnosis of AD or bvFTD were differentially related to the two main neuropsychiatric symptoms of apathy and disinhibition. They identified that the combination of apathy and disinhibition was largely associated with FTLD neuropathology, irrespective of clinical diagnosis. Disinhibition alone occurred less frequently in either AD or FTLD neuropathology compared with apathy, contrary to the common belief of it being highly associated with bvFTD. Finally, the frequency of disinhibition over disease progression remained low for those with either AD or FTLD neuropathology (Borges et al., 2019).

4. Inhibition deficits in other neurodegenerative diseases

4.1. Parkinson's disease (PD)

In PD, disinhibition is often reported under the term of “impulsivity” (see also section 5) and occurs in 13.6% of treated patients (Weintraub et al., 2010). It can manifest itself by pathological gambling, hypersexuality, compulsive shopping and binge eating, which have significant implications for patients and their families (Potenza et al., 2007; Voon & Fox, 2007). Some studies have also reported social disinhibition in PD patients who show difficulties in recognition of emotions and ToM impairments (Bodden et al., 2010; Saltzman et al., 2000; Desmarais et al., 2018). However, in contrast to AD and bvFTD, deficits in social cognition occur later in the course of the disease and early PD patients perform comparably to healthy controls (Bodden et al., 2010). This social impairment could have a multifactorial origin as the disease evolves, with advanced PD patients presenting executive dysfunction and psychiatric comorbidities which could explain the severe functional impairments observed (Desmarais et al., 2018).

Cognitive tasks also show inhibition deficits as PD patients are found to make riskier choices in response to monetary rewards (Voon et al., 2011a, b) and have impaired tolerance for delayed gratification (Voon et al., 2010). PD patients also show impulsivity on both verbal and action-response measures of inhibitory functioning, such as the Hayling Test and Go/No-Go tasks (Cooper et al., 1994, Obeso et al., 2011).

However, compared with bvFTD patients, PD patients show a milder degree of inhibitory impairment, both behaviourally (Barrett Impulsiveness Scale) and cognitively (Hayling Test) (O’Callaghan, Naismith, et al., 2013).

4.2. Progressive supranuclear palsy (PSP)

In PSP, the pathology affecting the brainstem and basal ganglia can extend to the prefrontal cortex, resulting in a prefrontal-subcortical syndrome (Donker Kaat et al., 2007; Rosen et al., 2005; Williams & Lees, 2009). This results in an apathetic phenotype mostly, but can include disinhibited behaviours, albeit less frequently as only described in a third of patients (Bak et al., 2010; Litvan et al., 1996). Assessment using the NPI reported that behavioural disinhibition in PSP was significantly higher than in PD, with both groups of patients under dopaminergic treatment (Aarsland et al., 2001). Another study showed that PSP and PD patients had impaired performance on the Go/No-Go task compared to healthy subjects, but there were no differences between patients (Zhang et al., 2016). Finally, in a very recent study, PSP patients performed similarly to controls on the Hayling test, but they presented “positive” disinhibition-related symptoms on the FBI which were less severe than in bvFTD (Santillo et al., 2016). This finding is in agreement with previous results using the CBI (Bak et al., 2010).

4.3. Huntington's disease (HD)

Inhibition impairments are also reported in 34.6% of patients suffering from HD (Paulsen et al., 2001), manifesting as impulsivity, hyperactivity, “acting out” and emotional lability (Duff et al., 2010). These behaviours can include speaking out of turn, embarrassing remarks (like inappropriate sexual remarks) and childish behaviours (Eddy et al., 2016), which are particularly troubling for caregivers. Sometimes, as mentioned above in previous diseases, disinhibition can also lead to illegal behaviours such as stealing (Johnson & Paulsen, 2015). HD patients are also impaired in social cognition, with difficulties in recognising emotions and theory of mind impairments (Bodden et al., 2010; Snowden et al., 2003, 2008). These are found to lead to disinhibited behaviours in social situations (Eddy et al., 2016). Some studies showed that disinhibition is negatively correlated with age (Paulsen et al., 2001), and more severe in younger mutated gene carriers (Duff et al., 2007).

Basal ganglia and caudate nucleus represent the epicentre of brain damage. The occurrence of inhibition disorders in these patients underlines the role of such structures in the genesis of such pathological behaviours (see also section 6).

5. Impulsivity and compulsivity across neurodegenerative diseases

Excessive impulsivity and compulsivity are common in neurodegenerative diseases, in particular in bvFTD for which they are among the discriminative diagnostic criteria (Rascovsky et al., 2007, 2011). In AD, impulsivity (including agitation, irritability, aggressivity, disinhibition) (Rochat et al., 2013) tends to increase with the severity and progression of the disease (Bidzan et al., 2012; Rochat et al., 2008) but both impulsive and compulsive behaviours are generally less frequent than in bvFTD (Miller et al., 1995; Rascovsky et al., 2011). It therefore appears that in these neurodegenerative diseases, at least, impulsive and compulsive behaviours co-occur with disinhibition.

6. Structural, metabolic and functional correlates of disinhibition

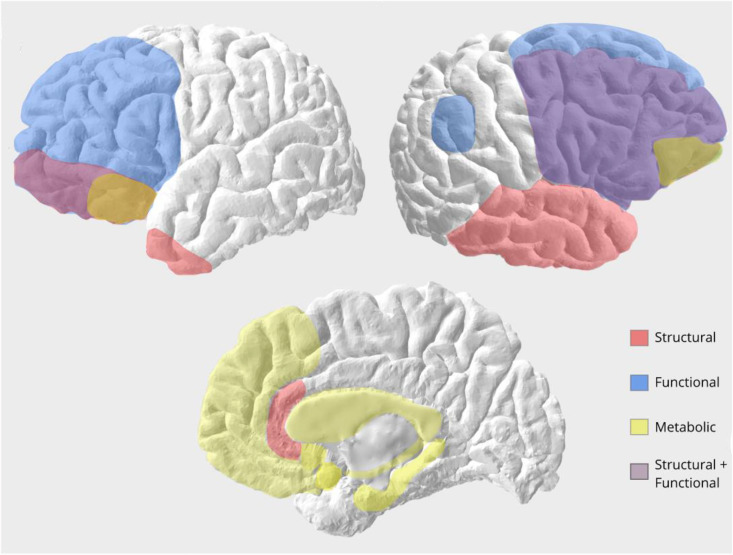

Here, we report major imaging and physiological results available in the literature of the considered neurodegenerative dementias. Fig. 1 summarises the main hemispheric areas.

Fig. 1.

Hemispheric brain regions (left and right hemisphere, medial/limbic regions) associated with different measures of disinhibition in patients with neurodegenerative diseases. In red, atrophied regions associated with disinhibition, as such left and right orbitofrontal cortex, right inferior and middle frontal cortex, right inferior, middle and superior gyri, temporal pole and subgenual cingulate. In blue, regions showing different functional activity in disinhibited patients, as such the right angular cortex and prefrontal cortex. In yellow, regions found to show metabolic differences in disinhibited patients, as such posterior orbitofrontal cortex, medial frontal cortex and limbic structures including the hippocampus, amygdala, caudate, nucleus accumbens and insula (insula not shown here). In violet, overlapping regions involved in both structural and functional studies, such as the right lateral prefrontal cortex and left inferior frontopolar regions.

6.1. Structural studies: grey matter

As mentioned above, disinhibition, both cognitive and behavioural, is a symptom of several neurodegenerative diseases. Although the literature remains relatively sparse, progress has been made in relating brain and neurodegeneration to disinhibition and its severity, often combining cognition and behaviour.

One of the first voxel-based morphometry studies conducted by Rosen and collaborators in 2005 correlated subscores of the NPI with atrophy in 148 patients with various neurodegenerative dementias, including patients with FTD, semantic (sv-PPA) and non-fluent variant (nf-PPA) of primary progressive aphasia, corticobasal degeneration, PSP and AD. The study found that the NPI subscore of disinhibition correlated with atrophy in the subgenual cingulate cortex, but only in the FTLD patient group (Rosen et al., 2005). Later, Possin and collaborators assessed executive function, in a large sample of patients (FTD, AD, PSP, sv-PPA, corticobasal syndrome, amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, Mild Cognitive Impairment-MCI) and controls by using various tests (e.g., TMT, the Design Fluency, etc.) (Possin et al., 2009). Rule violation scores, considered a proxy measure of cognitive disinhibition, correlated with right inferior and middle frontal gyri atrophy.

In more recent studies targeting FTD patients and using more specific measures of disinhibition as well as advanced imaging analysis methods, the orbitofrontal cortex seems to be the most important region implicated in disinhibition. In particular, atrophy of the medial part of orbitofrontal cortex is found to be associated with scores on disinhibition items of the NPI (Massimo et al., 2009). In a study comparing subgroups of bvFTD patients having as first symptom either apathy or disinhibition, it was found that the latter group showed greater atrophy in frontotemporal regions compared with the former (Santamaria Garcia et al., 2016). Multivariate analyses confirmed that brain areas including right orbitofrontal, but also right dorsolateral prefrontal, and left caudate were enough to distinguish these patient subgroups (Santamaria Garcia et al., 2016).

The importance of orbitofrontal cortex in disinhibition has also been corroborated in other neurodegenerative diseases. A study spanning a large cohort of several neurodegenerative diseases (including AD, bvFTD, sv-PPA, nf-PPA, PSP, CBD and MCI) found that although NPI-measured disinhibition correlated with various brains regions, only the orbitofrontal cortex significantly predicted disinhibition when entered into a hierarchical regression (Krueger et al., 2011). The frontal lobes are also associated with NPI-measured disinhibition in AD patients alone, in particular with the right frontal pole cortical thickness (Finger et al., 2017).

However, studies have demonstrated that disinhibition neural correlates also extend to the temporal lobe. In a study of bvFTD and AD patients, atrophy in orbitofrontal/subgenual, medial prefrontal cortex and anterior temporal lobe areas covaried with the total error score of the Hayling Test of disinhibition (Hornberger et al., 2011). Similarly, atrophy in both orbitofrontal cortex and temporal pole brain regions correlated with the NPI disinhibition frequency score in this same study (Hornberger et al., 2011). This convergent evidence from two different behavioural measures suggests that behavioural disinhibition involves the orbitofrontal but also temporal cortices.

Temporal lobe involvement has been corroborated in studies using other measures of behavioural disinhibition. In a recent study comparing subgroups of FTD patients ranging from “primary severe apathy” to “primary severe disinhibition” measured on the CBI-Revised questionnaire, authors found that those having isolated or additional behavioural disinhibition presented with a specific atrophy of right temporal gyri (O'Connor et al., 2017). This is in agreement with a pioneering study on anatomical correlates of disinhibition which found a correlation between the severity of disinhibition, quantified by using the FSBD subscale, and atrophy in the right superior temporal sulcus, right mediotemporal limbic structures and right nucleus accumbens (Zamboni et al., 2008). The relationship between disinhibition and right mediotemporal limbic structures has also been identified in another study in which bvFTD patients having the behavioural disinhibition as first symptoms were more atrophic in mediotemporal limbic structures, compared with those presenting with apathy (Garcia et al., 2015). These findings support the view that successful execution of complex social behaviours also relies on the integration of reward attribution and emotional processing, represented in mesolimbic structures.

Taken together, these findings suggest that behavioural disinhibition stems from the breaking down of connections between the temporal lobe and orbitofrontal regions rather than a consequence of the loss of specific functions represented separately in the temporal or frontal lobes (Bakchine, 2000). It has been suggested that temporolimbic structures and the nucleus accumbens are part of the same circuit including the orbitofrontal cortices and that behavioural disinhibition may be due to a loss of inhibition by the frontal monitoring system on the limbic system (Zamboni et al., 2008). This is enhanced by the findings that atrophy of insula (part of the limbic system) correlates with behavioural disinhibition, and that in humans the anterior insula integrates emotional and visceral information into representations of present moment context that guide socially appropriate behaviours (Wiech et al., 2010). Moreover, atrophy in the anterior insula is one of the earliest structural biomarkers of behavioural symptoms in FTD (Seeley, 2010). Frontolimbic disconnection through the anterior insula is therefore a strong candidate mechanism for explaining symptoms of behavioural disinhibition in FTD.

Finally, a recent paper, using statistical classification approaches, identified four subtypes of bvFTD based on distinctive patterns of atrophy defined by selective vulnerability of specific networks (Ranasinghe et al., 2016). The frequency of disinhibition and obsessive behaviours were the highest in the group which showed semantic appraisal network-predominant degeneration which included the anterior temporal lobe and subgenual cingulate (Ranasinghe et al., 2016). Thus, it may be possible to divide disinhibition into different subforms and these could be associated with different brain regions and networks. More efforts to build a consensus and refine disinhibition definitions and measures will be required in order to investigate the underlying neural correlates more precisely.

In addition to the hemispheric areas, recently we have found that performance on the Hayling test was correlated with grey matter volume in the cerebellum (i.e., lower cerebellar volumes are associated with lower performance) in individuals carrying a C9orf72 mutation (Montembeault et al., 2020). Connectivity studies have shown that the cerebellum is extensively connected with the prefrontal cortex via the thalamus (Behrens et al., 2003), which are both key regions in FTD. The neural connectivity between these brain regions might explain the correlation between cerebellum integrity and cognitive inhibition. More specifically, brain-behaviour relationships between specific posterior cerebellar regions and cognitive inhibition, or executive tasks suggestive of cognitive inhibition, have also been reported, especially in patients affected by spinocerbellar ataxia type 2. Thus, Stroop test performance has been associated with grey matter volume in the vermis crus II (Olivito et al., 2018), Go/No-Go task performance with grey matter volume in the vermis lobule VI (Lupo et al., 2018) and finally, Wisconsin Card Sorting task performance with grey matter volume in the vermis VIIb (Olivito et al., 2018).

6.2. Structural studies: white matter

The relationship between white matter fibers integrity and behavioural disinhibition has been investigated in recent years using diffusion tensor based imaging methods.

Powers et al (2014) found a correlation between fractional anisotropy in the right corona radiata and NPI-measured disinhibition in bvFTD. However, this could be explained because of the widespread involvement of this projection fibers tract within the brain and may therefore also reflect the overall pathology severity rather than specific severity of behavioural disinhibition.

A more detailed study in bvFTD and AD patients found that fractional anisotropy of the uncinate fasciculus (connecting the frontal with the superior and middle temporal gyri) and of the forceps minor (from the genu of the corpus callosum to the frontal pole) correlated with scores on the Hayling Test (Hornberger et al., 2011). As these tracts all enable the connection among frontal subregions and between frontal and temporal regions, this study points to networks within these regions being implicated in inhibitory functioning. The role of right uncinate fasciculus in disinhibition has been confirmed in another study on bvFTD and PSP patients, using a different measure, that of the Hayling total error score (Santillo et al., 2016), along with the right anterior cingulum and forceps minor. The authors concluded that their results support an associative model of inhibitory control, within a distributed network including medial temporal lobe, insula and orbitofrontal cortex, and connected by the intercommunicating white matter tracts.

Another white matter tract related to disinhibition is the superior longitudinal fasciculus (SLF) which connects the frontal, occipital, and temporal lobes. Bilateral SLF integrity is associated with disinhibition scores measured on the FrSBe in bvFTD patients (Sheelakumari et al., 2019). However, another study found a relationship among bilateral SLF and a large battery of cognitive and neuropsychological tests which also included tests of disinhibition such as the TMT (Borroni et al., 2007). These latter findings therefore suggest that SLF may not in fact be a specific neural correlate of disinhibition but of overall cognitive abilities.

The white matter tracts seemingly involved in disinhibition are numerous. This may be due to the fact that disinhibition is a complex behaviour which reflects the disconnection of multiple areas of the brain within the frontal, temporal and limbic regions, but also with the parietal lobes as demonstrated by the involvement of SLF shows (see also section 7 “Neurophysiological correlates” for a complementary interpretation). The interpretation of these findings is also limited by the diverse measures used to assess disinhibition in different studies, with scales focusing more on cognitive disinhibition while others focus on behavioural disinhibition. Finally, although bvFTD patients’ disinhibition can appear as a prominent and dominant behavioural dysfunction, it is not often isolated from other behavioural dysfunctions, such as apathy for instance. This makes the investigation of the neural correlates of disinhibition more difficult and studies should consider including measures of other behavioural symptoms as covariates in their analysis.

6.3. Metabolic studies

The study of brain metabolism has provided further evidence in the investigation of the neural correlates of disinhibition in neurodegenerative diseases. A strong correlation between behavioural disinhibition, measured by the NPI, and reduced metabolic activity in the posterior orbitofrontal cortex in bvFTD patients has been demonstrated (Peters et al., 2006). However, other studies with similar results in orbitofrontal cortex also found a relationship with other limbic structures including hippocampus, amygdala, caudate, accumbens and insula in patients with AD, FTLD and subjective cognitive impairments, in agreement with structural studies (Franceschi et al., 2005; Schroeter et al., 2011). This was also the case in a study which used a clustering approach to identify two major variants of cerebral hypometabolism in bvFTD patients, “frontal” and “temporo-limbic”, and which found that isolated disinhibition assessed on the NPI and FBI was only present in the latter sub-group (Cerami et al., 2016). However, this neuropsychological data was available for very few participants.

More recently, a study found hypometabolism in the bilateral medial and basal frontal cortex to be related to disinhibition in bvFTD patients presenting behavioural disinhibition (Morbelli et al., 2016). Interestingly, hypometabolism exceeded grey matter atrophy in terms of both extension and statistical significance in all comparisons. Disinhibition in these patients was assessed according to clinical examination and unstructured interviews and so is difficult to define precisely.

6.4. Right hemisphere bias?

Some of these studies paved the way for discussion about a potential right hemisphere bias with respect to behavioural disinhibition especially. Previously, this has been attributed to the involvement of the right hemisphere in complex social behaviours.

In a recent study this point was addressed dividing disinhibition items from the FrSBe into person-based versus non-person-based items. Person-based items were related to social aspects, and non-person-based items were related to generalised impulsivity (Paholpak et al., 2016). Using grey matter volumes from tensor-based morphometry, Paholpak et al. (2016) found that severity of person-based disinhibition in both bvFTD and early-onset AD patients significantly correlated with the left anterior superior temporal sulcus, whereas generalised-impulsivity correlated with the right orbitofrontal cortex (OFC) and the left anterior temporal lobe. This study therefore suggests that behavioural disinhibition can be dissected into subcategories corresponding to different brain areas highlighting the need for further defining of behavioural disinhibition.

6.5. Functional studies

Not many studies have used functional approaches to relate behavioural and cognitive disinhibition with functional networks in neurodegenerative diseases. One study published in 2013 found that prefrontal hyperactivity unique to bvFTD was marginally associated with their behavioural disinhibition scores on the FBI (Farb et al., 2013). Moreover, frontolimbic disconnection associated with lower disinhibition scores and stereotypy (measured on the stereotypy rating inventory) was correlated with elevated default-mode network connectivity in particular within the right angular gyrus node. The authors suggested that in FTD patients, observed frontolimbic disconnection may lead to unconstrained prefrontal cortex hyperconnectivity which may represent a compensatory response to the absence of affective feedback during the planning and execution of behaviour. Conversely, hyperconnectivity can also be interpreted as in some psychiatric conditions. In schizophrenia, for example, disease-induced impaired connectivity may lead to isolation of some brain systems, which can then demonstrate hyperconnectivity because they become less susceptible to influence from other systems (van den Heuvel et al., 2013). It is increasingly clear that more studies investigating networks functionally involved in behavioural disinhibition are required in order to confirm such claims.

6.6. Structural, metabolic and functional correlates of impulsivity and compulsivity

Lesion and neuroimaging (structural, functional and PET) studies indicate that the main regions involved in the circuits modulating impulsivity, compulsivity and related disorders in neurodegenerative diseases are the ventromedial prefrontal cortex (VMPFC), the OFC, the ACC, the amygdala, dorsal and ventral striatum (Averbeck et al., 2014; Brown et al., 2006; Matsuo et al., 2009; Paholpak et al., 2016). Impulsive and compulsive processes are thus thought to be related to cortico-striatal circuits modulated by different neurotransmitters (Robbins, 2007), with one striatal component (ventral striatum for impulsion/dorsal striatum for compulsion) driving impulsive and compulsive behaviours and one prefrontal component (VMPFC for impulsion/OFC for compulsion) restraining them (Fineberg et al., 2014). More research will clarify to what extent these regions may ressemble those underlying disinhibition and shed light on the possible relationship between impulsivity, compulsivity and disinhibition.

7. Neurophysiological correlates

In 2018, Hughes and colleagues found changes in cortical oscillatory dynamics as well as in frontal connectivity (specifically, cross-frequency coupling changes at the inferior frontal gyrus, pre-supplementary motor area, and motor cortex) in patients with bvFTD during a well characterised response inhibition task (Hughes et al., 2018). More interestingly, these brain measures of motor inhibition were correlated with everyday disinhibited behaviours in patients, as measured by Go/No-Go response inhibition paradigm.

Other authors have investigated recursive social decision-making behaviour which requires flexible, context-sensitive long-term strategies for negotiation which is highly sensitive to inhibition deficits (Melloni et al., 2016). They found that oscillatory measures could track the subtle social negotiation impairments in bvFTD. Risky offers during an ultimatum game moderated classic anticipatory alpha/beta activity in controls, but these effects were reduced in bvFTD patients. Source analysis demonstrated fronto-temporo-parietal involvement in long-term social negotiation that was also affected in bvFTD. This neurophysiological evidence is in agreement with evidence from structural and functional imaging pointing to similar regions. In brief, both studies suggest that brain oscillation patterns associated with behavioural control provide a neuropathological pathway of the different sources of impaired control in bvFTD.

Within this framework, Agustín Ibáñez has proposed three alternative neuroanatomical frameworks of inhibitory control and social-behavioural inappropriateness (Ibáñez, 2018). The first one is the canonical response inhibition network which includes motor, pre-motor and the inferior frontal gyrus. The second one, termed “bvFTD general disinhibition model”, is a network which takes into account multiple dimensions of non-adaptive behaviour and includes lateral temporal cortex, posterior and dorsal-anterior cingulate cortex, and posterior parietal cortex (Lansdall et al., 2017). The involvement of posterior parietal cortex could partially explain the correlation of some measures of disinhibition with the SLF, a major white matter bundle connecting parietal and frontal cortices. This bvFTD general disinhibition model also includes other components associated with impulse control depending on the inferior frontal region, anterior cingulate cortex but also with basal-temporal involvement (Zamboni et al., 2008). This is in line with the occurrence of disinhibition in neurodegenerative diseases primarily affecting basal ganglia as PD and HD. Finally, the third framework is the “social context network model” (SCNM) (Baez et al., 2017; Ibáñez & García, 2018; Ibáñez & Manes, 2012) which explains the bvFTD deficit as a general contextual deficit of social and cognitive processes and involves several brain regions, including the frontal pole, the orbitofrontal and temporal cortices, the insula, and the anterior cingulate cortex. Within these regions, for example, reduced fronto-posterior oscillations in bvFTD are associated with impaired social coordination (Ibáñez et al., 2017, Melloni et al., 2016), and complex social emotions (exacerbated counter-empathic dispositions) are related with disinhibition and extended fronto-temporo-parietal atrophy (Santamaria-Garcia et al., 2017). These proposed neurophysiological models of inhibition deficits mirror very closely structural, metabolic and functional correlates reported (Fig. 1).

8. Treatments of disinhibition

8.1. Phamacological interventions

The discussion of treatment strategies to diminish general behavioural disinhibition or impulsive behaviours in dementia patients is mainly based on bvFTD. No work has investigated this in other patients, such as AD (Keszycki et al., 2019).

Trieu and collaborators (2020) have just published a complete and systematic review of the literature through searching on PubMed, Embase, and PsycINFO databases for reports on pharmacological interventions for individuals with bvFTD (Trieu et al., 2020). Studies were included only if the efficacy of the intervention in alleviating bvFTD symptoms was provided as an outcome, and were measured with behavioural scales, such as the NPI (Cummings et al., 1994) or the FBI (Milan et al., 2008). The authors collapsed several clinical signs and symptoms under the term of “disinhibition”, such as general disinhibition, agitation, aggression, irritability, and abnormal risk-taking behaviours. In this study, consistently with our review approach, interesting results for general disinhibition and abnormal risk-taking behaviour were reported. It was found that five studies reported a positive effect of therapeutic intervention on general disinhibition. The most interesting were those administrating dextroamphetamine (Huey et al., 2008), or citalopram (30 mg, followed by a 6-week treatment with a daily dose of citalopram of 40 mg; Herrmann et al., 2012). Moreover, positive effects were also obtained with yokukansan (an Asian herbal medicine; Kimura et al., 2010), and with Souvenaid (Pardini et al., 2015), a patented combination of nutrients which include omega-3 fatty acids, choline, uridine monophosphate and a mixture of antioxidants and vitamin B. Finally, abnormal risk-taking behaviour was improved by a single dose of methylphenidate (40 mg) (Rahman et al., 2006).

Other studies have shown positive effects on disinhibition behaviours by using diverse selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs-namely, paroxetine, sertraline, and fluoxetine) (Herrmann et al., 2012; Lebert & Pasquier, 1999; Swartz et al., 1997). Some SSRIs, such as citalopram, seem to reduce sexual disinhibition in patients with dementia (Tosto et al., 2008). Generally speaking, neurochemistry of bvFTD is characterised by serotoninergic network disruption, with decreased serotonin levels and corresponding receptors in frontotemporal regions and neuronal loss in the raphe nuclei (Franceschi et al., 2005; Huey et al., 2006).

Also, the use of antipsychotic medications for the treatment of severe neurobehavioural symptoms has been suggested, particularly when SSRIs are not successful (Miller & Llibre Guerra, 2019). Within this category and concerning behavioural disinhibition, aripiprazole has shown good control of sexual disinhibition in a patient with bvFTD (Nomoto et al., 2017). In general, olanzapine, quetiapine, and risperidone have inconsistent evidence of benefit. Overall, the available studies suggest that physicians should use the smallest effective dose for the shortest possible duration to minimise adverse effects, and only in cases of refractory or severe behavioral symptoms (Reese et al., 2016).

Recently, brexpiprazole has been investigated for the treatment of agitation in AD, a largely unmet area of importance. Overall, well-tolerated brexpiprazole expands the armamentarium of treatment options available for these patients (Stummer et al., 2020). One could speculate that behavioural disinhibition could also benefit from this novel drug.

Old case studies also suggest that the anticholinesterase inhibitor rivastigmine might be helpful for this symptom (Alagiakrishnan et al., 2003), like antiepileptics such as gabapentin and carbamazepine (Alkhalil et al., 2004; Freymann et al., 2005; Miller, 2001), whereas donepezil might increase sexual disinhibition (Alagiakrishnan et al., 2003; Lo Coco & Cannizzaro, 2010) and socially disinhibited behaviour (Mendez et al., 2007).

Finally, in the case of disinhibition, particular attention must be paid to all the drugs stimulating the dopamine system. Particular concern for these drugs is their potential adverse effects involving increased behavioural disturbances such as disinhibition, as well as risk-taking behaviours, and hallucinations. Such symptoms have been observed in patients receiving dopamine replacement therapy for PD. Routine use of dopamine drugs in FTD patients is not currently recommended (Tsai & Boxer, 2014) especially if disinhibited.

8.2. Non pharmacological interventions

Most studies on non pharmacological interventions in neurodegenerative diseases have focused on reducing aggression and agitation, with no, or very few, studies focusing on the treatment of impulsivity or disinhibition (Keszycki, et al., 2019). However, some case examples have suggested that the engagement in previous hobbies or games may reduce socially inappropriate disinhibited behaviours in FTD patients. Therapeutic activities targeting other symptoms (e.g., agitation and aggression) can have a similar impact through the reduction of monotony and inactivity (Ikeda et al., 1995). Anecdotally, we reported a comparable experience with an FTD patient during the COVID-19 pandemic lockdown during which exacerbated disinhibition was attenuated by combining a small dose of atypical antipsychotic and doing recreational/social activities, like for example writing to family and friends to ask for news (Migliaccio & Bouzigues, 2020).

Some literature regarding non-pharmacological methods to mitigate sexual disinhibition suggests either ignoring the inappropriate situations by avoiding the problem such as “substituting staff who are less likely to trigger it” and wearing clothing that opens from the back (Hajjar & Kamel, 2003) or confronting it by expressing its inappropriateness (Keszycki, et al., 2019).

9. Concluding remarks

This review highlights that disinhibition is an important symptom of bvFTD and AD, as well as in some other pathologies. However, the definition of inhibition across studies remains rather vague. Although a division between cognitive and behavioural aspects exists in the literature, only a few studies highlighted a double dissociation (Olson et al., 1989; Harnishfeger, 1995). The division has been largely based on the different types of tests that exist, with some assessing cognitive inhibition and others behavioural inhibition. Thus, it is difficult to know if these are part of one same process or if these could be truly subdivided.

Moreover, disinhibition and impulsivity/compulsivity often co-occur, share common measurement methods and underlying neuropsychological mechanisms. However, the precise mechanisms of inhibition deficits underlying disinhibited, impulsive and compulsive behaviours are still unclear. It would be of great interest to investigate the relationships between these concepts, neuropsychological mechanisms and anatomofunctional networks specific to each subcomponent to understand whether or how these could be used in the diagnosis of neurodegenerative diseases.

Concerning the brain correlates of these behavioural symptoms, more efforts are required to build a consensus and refine the definition of inhibition and disinhibition as well as how these are assessed. Although imaging and neurophysiological studies have put forward some frameworks, it is only after such refining that future studies will be in a position to suggest models of the mechanisms underlying inhibition deficits in neurodegeneration.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Acknowledgements and Funding

Raffaella Migliaccio is supported by “France Alzheimer” and “Philippe Chatrier” Foundations, and by “Rosita Gomez association”. Delphine Tanguy is supported by École Normale Supérieure Paris-Saclay. Arabella Bouzigues is supported by Fondation Vaincre Alzheimer. Raffaella Migliaccio, Richard Levy, Valérie Godefroy and Bénédicte Batrancourt are supported by Fondation pour la Recherche Médicale.

Reviewed 13 July 2020

References

- Aarsland D., Litvan I., Larsen J.P. Neuropsychiatric symptoms of patients with progressive supranuclear palsy and Parkinson's disease. JNP. 2001;13:42–49. doi: 10.1176/jnp.13.1.42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ahearn D.J., McDonald K., Barraclough M., Leroi I. An exploration of apathy and impulsivity in Parkinson disease. Curr Gerontol Geriatr Res. 2012;2012:390701. doi: 10.1155/2012/390701. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ahmed R.M., Goldberg Z.-L., Kaizik C., Kiernan M.C., Hodges J.R., Piguet O., Irish M. Neural correlates of changes in sexual function in frontotemporal dementia: Implications for reward and physiological functioning. Journal of Neurology. 2018;265:2562–2572. doi: 10.1007/s00415-018-9024-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alagiakrishnan K., Sclater A., Robertson D. Role of cholinesterase inhibitor in the management of sexual aggression in an elderly demented woman. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. 2003;51:1326. doi: 10.1046/j.1532-5415.2003.514204.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alkhalil C., Tanvir F., Alkhalil B., Lowenthal D.T. Treatment of sexual disinhibition in dementia: Case reports and review of the literature. American Journal of Therapeutics. 2004;11:231–235. doi: 10.1097/00045391-200405000-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amieva H., Lafont S., Auriacombe S., Carret N.L., Dartigues J.-F., Orgogozo J.-M., Fabrigoule C. Inhibitory breakdown and dementia of the alzheimer type: A general phenomenon? Journal of Clinical and Experimental Neuropsychology. 2002;24:503–516. doi: 10.1076/jcen.24.4.503.1034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amieva H., Lafont S., Auriacombe S., Rainville C., Orgogozo J.M., Dartigues J.F., Fabrigoule C. Analysis of error types in the trial making test evidences an inhibitory deficit in dementia of the Alzheimer type. J Clin Exp Neuropsychol. 1998;20:280–285. doi: 10.1076/jcen.20.2.280.1161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amieva H., Le Goff M., Stoykova R., Lafont S., Ritchie K., Tzourio C., Fabrigoule C., Dartigues J.-F. Trail making test A et B (version sans correction des erreurs) : Normes en population chez des sujets âgés, issues de l’étude des trois cités. Revue de neuropsychologie. 2009;1:210. [Google Scholar]

- Amieva H., Phillips L.H., Della Sala S., Henry J.D. Inhibitory functioning in Alzheimer's disease. Brain: a Journal of Neurology. 2004;127:949–964. doi: 10.1093/brain/awh045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aron A.R. The neural basis of inhibition in cognitive control. The Neuroscientist: a Review Journal Bringing Neurobiology, Neurology and Psychiatry. 2007;13:214–228. doi: 10.1177/1073858407299288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Averbeck B.B., O'Sullivan S.S., Djamshidian A. Impulsive and compulsive behaviors in Parkinson's disease. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology. 2014;10:553–580. doi: 10.1146/annurev-clinpsy-032813-153705. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baez S., García A.M., Ibanez A. The social context network model in psychiatric and neurological diseases. Current Topics in Behavioral Neurosciences. 2017;30:379–396. doi: 10.1007/7854_2016_443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bak T.H., Crawford L.M., Berrios G., Hodges J.R. Behavioural symptoms in progressive supranuclear palsy and frontotemporal dementia. Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery, and Psychiatry. 2010;81:1057–1059. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.2008.157974. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bakchine S. In: Behavior and Mood Disorders in Focal Brain Lesions. Bogousslavsky J., Cummings J., editors. Cambridge University Press; Cambridge: 2000. Temporal lobe behavioral syndromes; pp. 369–398. [Google Scholar]

- Bari A., Robbins T.W. Inhibition and impulsivity: Behavioral and neural basis of response control. Progress in Neurobiology. 2013;108:44–79. doi: 10.1016/j.pneurobio.2013.06.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bathgate D., Snowden J.S., Varma A., Blackshaw A., Neary D. Behaviour in frontotemporal dementia, Alzheimer's disease and vascular dementia. Acta Neurologica Scandinavica. 2001;103:367–378. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0404.2001.2000236.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Batrancourt B., Lecouturier K., Ferrand-Verdejo J., Guillemot V., Azuar C., Bendetowicz D., Migliaccio R., Rametti-Lacroux A., Dubois B., Levy R. Exploration deficits under ecological conditions as a marker of apathy in frontotemporal dementia. Frontiers in Neurology. 2019;10 doi: 10.3389/fneur.2019.00941. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Behrens T.E.J., Johansen-Berg H., Woolrich M.W., Smith S.M., Wheeler-Kingshott C.a.M., Boulby P.A., Barker G.J., Sillery E.L., Sheehan K., Ciccarelli O., et al. Non-invasive mapping of connections between human thalamus and cortex using diffusion imaging. Nature Neuroscience. 2003;6:750–757. doi: 10.1038/nn1075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berg E.A. A simple objective technique for measuring flexibility in thinking. The Journal of General Psychology. 1948;39:15–22. doi: 10.1080/00221309.1948.9918159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bertoux M., Delavest M., de Souza L.C., Funkiewiez A., Lépine J.-P., Fossati P., Dubois B., Sarazin M. Social Cognition and Emotional Assessment differentiates frontotemporal dementia from depression. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2012;83:411–416. doi: 10.1136/jnnp-2011-301849. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bertoux M., Funkiewiez A., O'Callaghan C., Dubois B., Hornberger M. Sensitivity and specificity of ventromedial prefrontal cortex tests in behavioral variant frontotemporal dementia. Alzheimer’s & Dementia. 2013;9:S84–S94. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2012.09.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bidzan L., Bidzan M., Pąchalska M. Aggressive and impulsive behavior in Alzheimer's disease and progression of dementia. Medical Science Monitor: International Medical Journal of Experimental and Clinical Research. 2012;18:CR182–CR189. doi: 10.12659/MSM.882523. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bodden M.E., Dodel R., Kalbe E. Theory of mind in Parkinson's disease and related basal ganglia disorders: A systematic review. Movement Disorders. 2010;25:13–27. doi: 10.1002/mds.22818. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borges L.G., Rademaker A.W., Bigio E.H., Mesulam M.-M., Weintraub S. Apathy and disinhibition related to neuropathology in amnestic versus behavioral dementias. American Journal of Alzheimer's Disease and Other Dementias. 2019;34:337–343. doi: 10.1177/1533317519853466. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borroni B., Brambati S.M., Agosti C., Gipponi S., Bellelli G., Gasparotti R., Garibotto V., Di Luca M., Scifo P., Perani D., et al. Evidence of white matter changes on diffusion tensor imaging in frontotemporal dementia. Archives of Neurology. 2007;64:246. doi: 10.1001/archneur.64.2.246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boutoleau-Bretonnière C., Evrard C., Hardouin J.B., Rocher L., Charriau T., Etcharry-Bouyx F., Auriacombe S., Richard-Mornas A., Lebert F., Pasquier F., et al. DAPHNE: A new tool for the assessment of the behavioral variant of frontotemporal dementia. Dement Geriatr Cogn Dis Extra. 2015;5:503–516. doi: 10.1159/000440859. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]