Abstract

More than a quarter of working-age households in the United States do not have sufficient savings to cover their expenditures after a month of unemployment. Recent proposals suggest giving workers early access to a small portion of their future Social Security benefits to finance their consumption during the COVID-19 pandemic. We empirically analyze their impact. Relying on data from the Survey of Consumer Finances, we build a measure of households' expected time to cash shortfall based on the incidence of COVID-induced unemployment. We show that access to 1% of future benefits allows 75% of households to maintain their current consumption for three months in case of unemployment. We then compare the efficacy of access to Social Security benefits to already legislated approaches, including early access to retirement accounts, stimulus relief checks, and expanded unemployment insurance.

Keywords: Covid-19, Social security, Household finance

Highlights

-

•

We study a proposal to give workers access to a small portion of future Social Security benefits to finance consumption during the Covid-19 crisis.

-

•

We estimate that a 1% cut in future benefits has a present value $2884 for the average worker, and $4220 for the average household.

-

•

Early access to 1% of future benefits allows three quarters of unemployed workers to finance their consumption for more than three months.

-

•

Compared to alternatives, early access to Social Security would not add to government liabilities. But, it would reduce resources for retirement.

1. Introduction

The COVID-19 pandemic has pushed US unemployment to its highest level since the Great Depression. Now, policymakers are weighing an unprecedented change to the Social Security system: allowing workers to access a portion of future benefits prior to retirement to finance consumption today.1 Early access to Social Security wealth would boost household liquidity. But, it will also decrease the resources that retirees will have later in life. The magnitudes are uncertain and may vary across the wealth distribution. Assessment of this proposal requires careful consideration of workers' Social Security benefits and their distribution. Only then is it possible to analyze the impact of a cut to future benefits on households, today and in the future.

This paper undertakes this task. Specifically, we build on the Catherine et al. (2020) estimate of Social Security wealth to compute the market value of expected Social Security benefits for each worker we observe in the Survey of Consumer Finances (SCF). We compute expected benefits by simulating workers' earnings trajectories and then discount these benefits, accounting for the long-run correlation between Social Security and stock market returns. We find that a 1% decrease (representing on average $15) in monthly benefits significantly boosts liquidity. It provides on average $2884 per worker today.

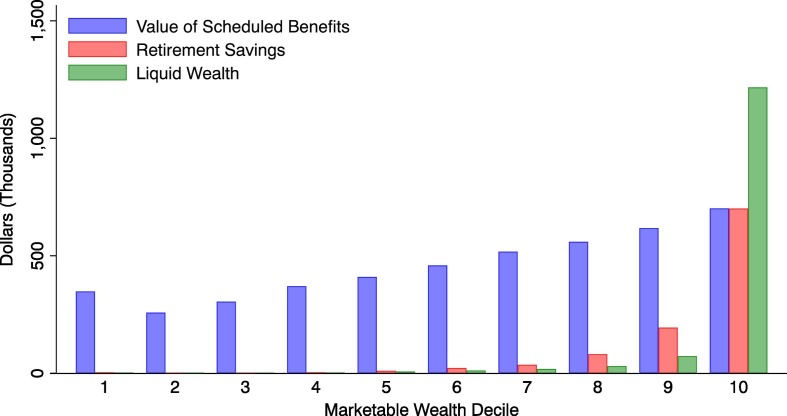

As Fig. 1 illustrates, Social Security benefits are relatively evenly distributed across the wealth distribution, whereas the value of retirement accounts and liquid savings is concentrated in the top decile. Social Security is hugely significant to most Americans: It represents nearly 60% of the wealth of the bottom 90% (Catherine et al., 2020). In its last annual report, the Social Security Administration reports that the aggregate value of benefits scheduled for current participants is nearly $80 trillion.

Fig. 1.

Distribution of various forms of wealth.

This figure shows the distribution of Social Security wealth, retirement wealth, and liquid wealth across deciles of the marketable wealth distribution. The blue bar denotes the per household average present value of scheduled Social Security benefits, the red bar shows the per household average amount of retirement savings, and the green bar displays the per household average liquid wealth. We calculate the present value of Social Security benefits by simulating workers' earnings trajectories and matching this data with the SCF based on current earnings. Retirement accounts are defined as IRA accounts, thrift accounts, or any current or future defined contribution pension obligations and comes from the SCF. Liquid wealth is defined as all wealth held in transactions accounts, certificates of deposit, mutual funds, stocks, bonds, and also comes from the SCF.

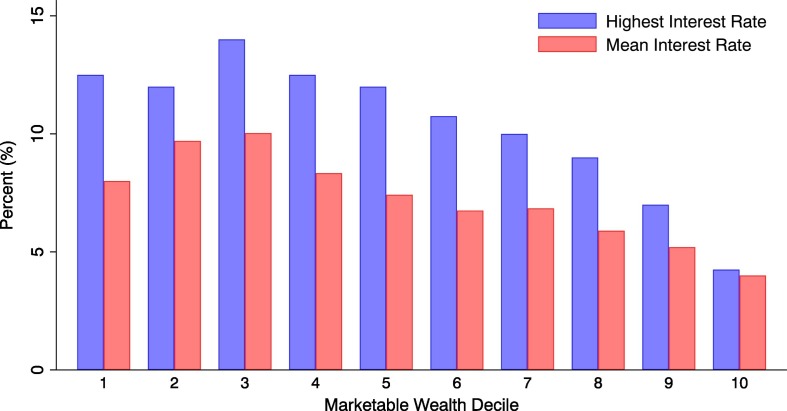

Allowing workers to tap a share of Social Security benefits early would allow them to borrow at historically low interest rates. For most of them, this cannot be done on private markets. As Fig. 2 shows, in 2016, a majority of households faced a marginal interest rate above 10%. Households who do not need this loan can choose to invest the money in government bonds and should be indifferent. From the point of view of the government, an approach like this one transforms implicit Social Security liabilities into public debt but leaves its overall long-run obligations unchanged.

Fig. 2.

Private borrowing rates across the wealth distribution.

This figure shows the maximum and mean borrowing rates for SCF respondents for each decile of the marketable wealth distribution. The blue bars represent the mean highest borrowing rates reported by each household. The red bars represent mean borrowing rates. Credit card rates are only included if the respondent has rolled over a nonzero balance from the previous month. People with no debt are excluded. Bars represent the median value in each decile.

In the second part of the paper, we measure how many days it takes for households to run out of cash in case of unemployment. We use this measure to evaluate the efficiency of an early distribution of 1% of Social Security benefits and compare this policy to already enacted alternatives: allowing workers to tap retirement accounts without penalty, $1200 stimulus checks, and the extension of unemployment insurance by $600 per week. Importantly, we adjust our unemployment estimates to reflect the fact that this crisis disproportionately displaces young workers in particular industries (e.g., food services and entertainment) with the least liquid savings. Overall, distributing 1% of the value of scheduled benefits allows 75% of households to go through 3 months of unemployment without cutting their consumption. A similar – and more administrable – approach would be to provide workers an advance on future Social Security benefits: a $2500 check today corresponds to less than a 1% cut in future benefits for nearly all workers. Only the supplemental unemployment insurance of $600 per week provides more liquidity, which is hardly surprising since it implies a median replacement rate of 134% (Ganong et al., 2020).

For most retirees, Social Security income is their primary source of support during retirement. Thus, consideration of any Social Security-based emergency liquidity program must consider the impact on future retirement security. The goal of this paper is to provide an actuarial analysis of a proposal to decrease future Social Security benefits to fund consumption today and to quantify its effect on household liquidity. We do not seek to provide a normative judgment on optimal policies to be pursued. Indeed, there are strong political economy arguments against a Social Security-based approach: opening up the idea that Social Security can be used to meet liquidity needs may lead policymakers to meet other needs that occur during working lives through erosion of retirement support, rather than alternative social insurance arrangements.2

One contribution of our paper is it provides a framework to evaluate the consequences of policy proposals in this vein for households and to determine whether they are being priced in an actuarially fair manner. The baseline approach we consider estimates the liquidity that results from a fairly priced exchange of 1% of future Social Security benefits for a check today. On average, $15 less in monthly benefits in retirement means households can finance their consumption for two months. The details of current policy proposals are not yet clear, but some press reports suggest significantly larger magnitudes: that workers may be able to opt into $10,000 of benefits today. This would constitute 3.5% share of future benefits or claiming benefits five months later, if priced in an actuarially fair way. Further, since workers can opt-in to this program, concerns about adverse selection loom large.

This paper adds to several strands of literature. First, we contribute to the growing literature on the economic impact of COVID-19 and evaluation of policies aimed at stemming it (Baker et al., 2020; Barrero et al., 2020; Bartik et al., 2020; Ganong et al., 2020; Gormsen and Koijen, 2020). In a recent policy piece, Biggs and Rauh (2020) consider a related approach: allowing workers to access Social Security wealth today and delay retirement to repay these benefits. Under current law, workers can offset a 1% cut in benefits by claiming benefits eight weeks later.

We also add to the literature on the design of public savings programs. In the U.S. and many other countries, public savings are designed to be illiquid to supplement the private market for longevity insurance, plagued by adverse selection problems (Abel, 1986; Hosseini, 2015; Eckstein et al., 1985). In recent work, Beshears et al. (2019) point out that illiquid retirement savings are optimal with households with present bias. They suggest a role for three distinct types of savings accounts: liquid savings, semi-liquid retirement accounts with withdrawals made at penalty, and fully illiquid accounts. We extend this literature by pointing out that the optimal mandatory savings rate could be countercyclical. Practically, even if these three types of savings vehicles are first-best, when nearly half of households lack any semi-liquid retirement savings, introducing some liquidity into the Social Security program may be beneficial. Much work has advocated the provision of lump-sum benefits of Social Security wealth to discourage early retirement, noting households' preferences for one-time payouts that enable them to pay down mortgages or other debt (Maurer et al., 2016; Maurer and Mitchell, 2018). We build on this insight, suggesting that lump sum payments in this crisis would provide households a way to finance expenditure at record-low rates of interest.

The remainder of our paper proceeds as follows. Section 2 describes the Social Security program and our approach for valuing Social Security benefits, and estimates the consequences of early access to Social Security across the age distribution. Section 3 compares this approach to other alternatives to increase households' liquidity, including tapping retirement accounts, stimulus checks, and extended unemployment benefits. Section 4 concludes.

2. Valuing scheduled benefits

In this section, we estimate how much can be paid immediately to households in exchange for a small cut in future Social Security benefits. Because benefits are determined based on individuals' historical earnings, the present value of benefits depends on age and earnings trajectories.

We estimate the market value of a benefit cut in two steps. First, we compute expected benefits by simulating earnings trajectories and applying the Social Security benefit formula, assuming all workers retire at full retirement age.3 Second, we discount expected benefits using the real yield curve4 implied by Treasury inflation-protected securities (TIPS) and taking into account the long run correlation between Social Security and stock market returns, following the approach of Catherine et al. (2020).

2.1. Expected benefits

2.1.1. Simulating earnings

To forecast benefits, we simulate earnings using the income process estimated in Guvenen et al. (2019). Specifically, we assume that a worker i earnings at age t are:

| (2.1) |

where L 1, t is the average wage in the economy and L 2, it represents the idiosyncratic component of earnings. The latter evolves as follows:

| (2.1.1) |

| (2.1.2) |

| (2.1.3) |

| (2.1.4) |

| (2.1.5) |

| (2.1.6) |

| (2.1.7) |

where z i is a component of earnings with persistence ρ and innovations drawn from a mixture of normal distributions. Transitory shocks ε i also have a normal mixture distribution. Finally, workers can experience a period of unemployment with probability p which depends on age, earnings and gender, and whose length follows an exponential distribution. We refer readers to Guvenen et al. (2019)’s study for more details.

2.1.2. Benefit formula

Social Security benefits are computed in three steps. First, past taxable earnings are wage-indexed, which means that they are adjusted to reflect the growth in nominal wages up to the year a worker reaches age 60. In a second step, the average indexed yearly earnings (“AIYE”) is determined by averaging the best 35 years of indexed earnings. Finally, benefits are computed as a concave function of the AIYE. Specifically, benefits equal the sum of 90% of the share of the AIYE below the first Social Security “bend point” ($11,112 in 2019), 32% of the share AIYE between the first and second bend point ($66,996) and 15% of the remaining part of the AIYE. Since the 1980's, these bend points have tracked the evolution of earnings, representing 0.21 and 1.25 times the national wage index L 1. We assume that they will keep evolving that way. Hence, the value of benefits is a piece-wise linear function of the AIYE:

| (2.2) |

where L 1, 60 is the level of wage index when a worker turns 60.

2.2. Market value

We need to determine the present value of a stream of benefits protected against inflation, backed by the Federal government and indexed on the national wage index. We define the present value of expected benefits as:

| (2.3) |

where T is the maximum age, m ik is mortality at age k, and Ψ s is the appropriate discount factor for benefits paid at age s.

When discounting benefits, we take into account that wage indexation exposes the government to systematic risk because of the correlation between market returns and the wage index. This contemporaneous correlation is small but Benzoni et al. (2007) argue that the labor and stock markets are cointegrated, which reduces the present value of benefits substantially (Catherine, 2019; Geanokoplos and Zeldes, 2010). To take this into account, we model the evolution of the log national index l 1 and the log cumulative market returns s t as in Benzoni et al. (2007):

| (2.4) |

In these equations, μ − δ determines the unconditional log aggregate growth rate of earnings and v 1 its volatility. μ and σ s represent expected stock market log returns and their volatility. The state variable y t keeps track of whether the labor market performed better or worse than the stock market relative to expectations. Finally, κ determines the strength of the cointegration between the labor and stock markets.

In Catherine et al. (2020), we show that the market beta of a “wage bond” paying a single cash flow indexed to the value of L 1, n in n years is:

| (2.5) |

and we demonstrate that, under the no-arbitrage condition, the expected return on such a bond is:

| (2.6) |

where r is the risk-free rate. Therefore, for workers below age 60, the appropriate discount factor for a benefit expected at age s is:

| (2.7) |

where f k is the forward real interest rate between years k-1 and k.

2.3. Calibration and validity

We calibrate the dynamics of idiosyncratic earnings using the benchmark estimation of Guvenen et al. (2019) (see Appendix Table C.1). In Catherine et al. (2020), we use the same simulation strategy to estimate the value of future benefits, net of future payroll taxes, from 1989 to 2016. We validate this approach by showing that, when using the same macroeconomic assumptions, we can track very well the evolution of aggregate Social Security obligations reported by the Office of the Chief Actuary of the SSA. Moreover, we also show that our simulation produces full-retirement benefits that match those observed in the SCF. Finally, the income process estimated in Guvenen et al. (2019) matches many moments of the cross-section and dynamics of earnings.

We calibrate the model in Section 2.2 as in Benzoni et al. (2007). These authors estimate κ=.16 and ϕ=.08 using US macroeconomic data from 1929 to 2004. This calibration implies a market beta of 0.5 for very distant Social Security benefits. We assume an equity premium of μ − r=0.06. We use the TIPS yield curve of April 2020 to compute forward interest rates. Finally, we use the SSA wage growth projections from the 2019 report of the Office of the Chief Actuary for the national wage index.5

It is worth noting that our simulation does not take into account the effect of the COVID downturn on wages. Implicitly, we assume that, after the pandemic, labor market conditions will return to normal within a couple of years. There are two reasons we are skeptical the downturn will meaningfully impact our valuation of Social Security: first, at the individual level, since Social Security benefits are determined based on the best 35 years in the labor force, corona induced un- or under-employment should not impact benefits. Second, at the more macro-level, even two years of 0% growth will decrease the market value of Social Security by at most 2%.

2.4. Results

We simulate past and future earnings for 800,000 workers per cohort, producing a cross-section of 36 million observations for the year 2020. The simulated dataset includes age, average past taxable earnings and the present value of expected benefits. We use this simulated data to estimate how much can be paid to workers today in exchange for a small cut in old-age benefits. Our focus is on working age (20 to 61 year-old) individuals. The answer to this question is a function of workers' age and earnings histories.

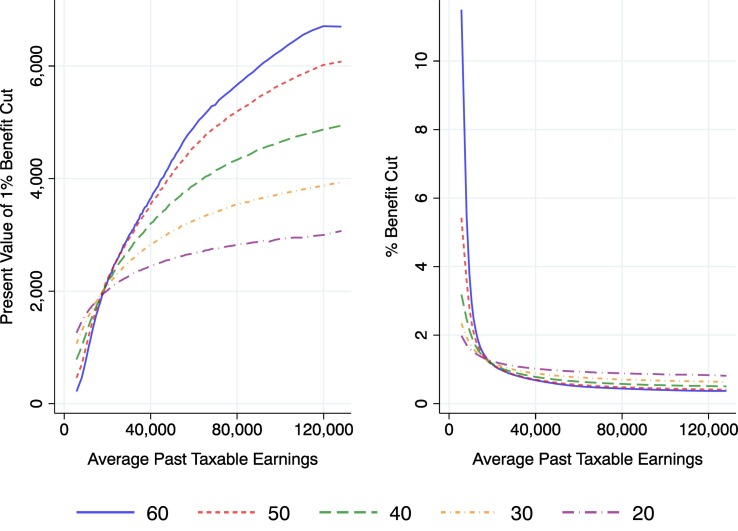

Panel A of Fig. 3 illustrates this fact. The present value of a 1% cut is highest for workers who are approaching retirement because they borrow against more imminent cash flows. In contrast, it is less significant for workers who have just entered the labor force and who will start repaying this loan in forty years.6 But importantly, across the age and earnings distribution, just a 1% decrease in benefits significantly boosts liquidity by providing more than $2000 to the large majority of workers. In dual-earner households, the provision of liquidity would be twice as large.

Fig. 3.

Price of early Social Security check.

This figure shows the relationship between benefit cuts and check size as a function of workers' age and the average past taxable earnings. Panel A shows how much can be paid in exchange for a 1% benefit cut. Panel B shows the benefit cuts corresponding to a $2500 check. The graphs are constructed by simulating data following the procedure outlined in Section 2.

To illustrate this point another way, we consider what cut in benefits would be required to deliver workers $2500 today (Fig. 3, Panel B), enough to finance roughly one month of consumption for the median household. For all but the lowest earners, the decrease in future benefits is minor: for 40 year old individuals earning the median income of around $34,000, a $2500 check represents between 0.8% (75th percentile) and 1% (25th percentile) of future benefits.

It is worth noting that this is not the case for workers close to retirement with limited past earnings, for whom a $2500 check today could represent between 5 and 10% of future benefits. This is a population that has not accrued much Social Security wealth (e.g., because of little time spent in the workforce).

3. Relaxing housing liquidity constraints

We next quantify the magnitude of households' liquidity constraints and consider how they are exacerbated by COVID-19. We then document the extent to which a small cut in future Social Security benefits redresses them. We compare this approach to already legislated household support: penalty-free access to retirement accounts, stimulus checks, and a significant expansion of unemployment benefits.

3.1. Time to cash shortfall

We start by estimating how long it takes for households to run out of cash when they are on unemployment benefits. This depends on their liquid wealth, the generosity of unemployment benefits and their consumption level. We define the variable “Days to shortfall” as:

| (3.1) |

where the denominator represents daily expenditures minus insurance benefits. Two categories of households are more likely to run out of cash faster: (i) those with rent and mortgage payments and (ii) those with low liquid wealth-to-earnings ratios. We build these variables using the 2016 SCF, which provides detailed information on wealth, income, and expenditures by household.

First, we assume that baseline unemployment insurance covers 50% of after-tax income. In reality, the benefit formula varies by state and takes into account workers' earnings and employment histories. Because the SCF does not provide geographic information about respondents, we are unable to compute replacement rates by state. However, our assumption is broadly consistent with the 45% average replacement rate reported by the Department of Labor for 2019. After-tax income is computed using the federal tax code and taking into account income, family composition and deductions.

Housing and fixed expenditures include rent, mortgage payments, property taxes, co-op, and mobile home fees, car lease payments, as well as other loan payments. The details of these expenses is reported in the SCF. We assume that consumption of other goods and services represent 60% of after-tax income, which generate higher savings rates among higher earners, in line with prior work (Dynan et al., 2004). Our calibration implies an average saving rate of 6%, which matches the aggregate personal savings rate over the last 20 years.7

Finally, liquid wealth is constructed as in Bhutta and Dettling (2018) and includes transactions accounts, certificates of deposit, mutual funds, stocks, and bonds. Using these estimates yields a proxy of Eq. (3.1) that can be observed in the data, which is the measure we use for the remainder of the paper.

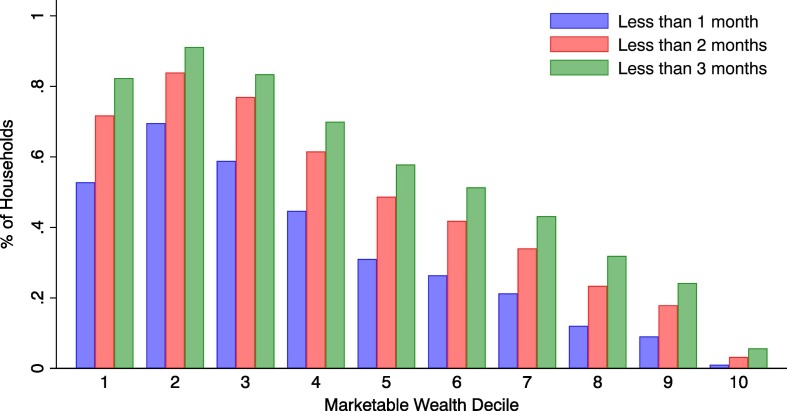

Fig. 4 shows the share of households who can maintain their consumption up to 30, 60 or 90 days when unemployed, for each decile of marketable wealth.8 Unsurprisingly, wealthy households can afford to remain unemployed for longer. But the differences are stark: for those in the bottom three deciles of the marketable wealth distribution, more than 85% cannot cover three months of expenditures should they become unemployed. In the top decile, less than 5% face the same issue. Age is an important explanation for this fact: workers who have just entered the labor force have yet to accumulate significant precautionary savings.

Fig. 4.

Time to shortfall by decile of wealth.

This figure shows the fraction of households who can maintain their consumption on standard unemployment benefits for less than three, two, or one month before running out of cash by decile of marketable wealth. The time to shortfall measure is based on estimates of liquid wealth, consumption, and fixed expenditures computed from the Survey of Consumer Finances.

3.2. Impact of COVID-19 without intervention

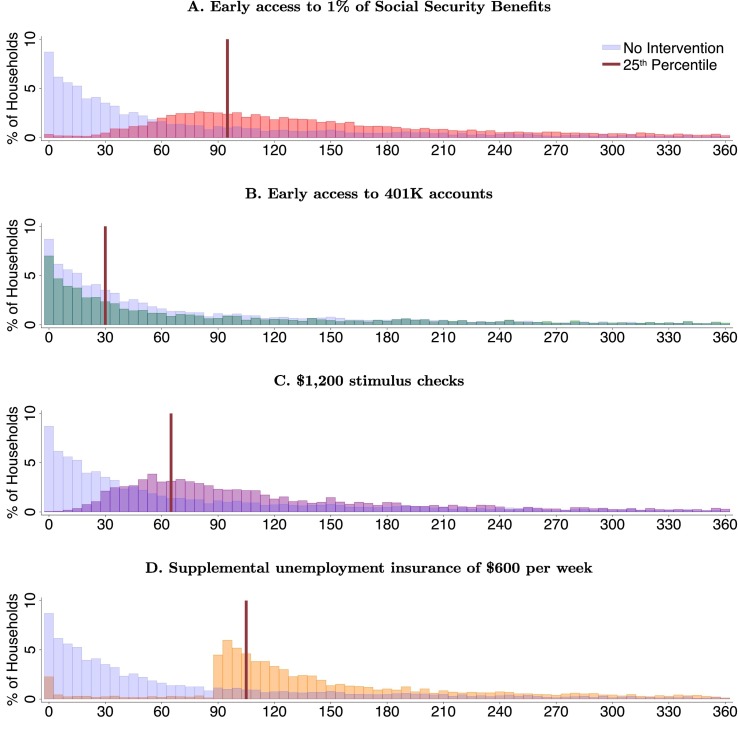

In Fig. 5 , Panel A, we consider the implication of the counterfactual world in which aggressive stimulus efforts had not been undertaken to provide liquidity to households in need. We illustrate how our measure of days until cash shortfall is distributed throughout the population.

Fig. 5.

Days to cash shortfall under different policies.

This figure shows the number of days until working-age households run out of cash in case of unemployment under different policies. Time to Shortfall is defined as liquid wealth divided by daily expenditures minus daily unemployment benefits, which we assume covers 50% of after-tax income. Each bin represents a 5-day increment and the graphs report the percentage of households who would run out of cash within these 5 days. The light blue bars in each graph show the no intervention case. Panel A refers to the policy proposal of providing individuals checks equal to 1% of the present value of expected Social Security benefits. Panel B shows the scenario in which workers can withdraw from their retirement accounts without penalty. Panel C shows the effect of giving $1200 checks to households using the policy outlined in the CARES Act. Panel D shows the results of $600 in extra unemployment insurance, as provided for by the CARES Act. The red, vertical lines represent the 25th percentile of the each time to shortfall variable.

Importantly, we adjust the SCF sample weights such that our sample is representative of workers who have lost their jobs as a consequence of the coronavirus crisis as of March 2020. This is important, since COVID-based unemployment is substantially likely to displace exactly those workers without private savings: Already, estimates suggest that 40% of workers making $40,000 or less annually have lost their jobs because of the pandemic.9

Using data from the Current Population Survey (CPS) and the Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS), we estimate the probability of becoming employed in that last six weeks as a function of industry, education, and age. We then adjust the SCF weights by multiplying them by the model implied probability of unemployment and dividing by the mean of this variable.

Overall, American households do not have sufficient liquid savings to weather the COVID-19 crisis. If displaced workers were only receiving unemployment benefits to supplement on average 50% of lost wages (as in normal times), more than 25% of working age households would not be able to meet their current expenditures after a month of unemployment, and 50% cannot last more than 75 days.

3.3. Early social security benefits

What would be the effect of allowing households to borrow against 1% of scheduled Social Security benefits? To analyze the quantitative effects of this policy, we must estimate the present value of Social Security benefits for each household in the SCF. To do this, we simulate a data set of 36 million individuals using the procedure described in Section 2.1, which contains age, sex, the present value of future benefits, average past taxable wage earnings, and current wage earnings. We then match the SCF to the simulated data by randomly assigning each individual in the SCF to a simulated outcome with the same age, sex, and wage income.

Early access to 1% of Social Security benefits are a boon to the liquidity of the most vulnerable households, as illustrated in Panel A of Fig. 5. With 1% of Social Security benefits today, the bottom 25% of the marketable wealth distribution would have an additional 85 days on average until they are no longer able to cover their current consumption, and the 25th percentile in terms of liquidity shortfall now has an additional two-and-a-half months of support, and the median is over three months. Even this small cut in benefits supports more consumption than most of the alternatives already legislated, as discussed below.

From an administrability standpoint, early access to 1% of Social Security benefits will pose challenges. This is because the government will have to arrive at estimates of earnings trajectories for individuals. Although this paper provides a framework for how such estimation may take place, it is a difficult task and the administration of COVID-related policies thus far raises questions of its feasibility.10 A more easily implementable approach would be a one-time advance of future Social Security benefits: a $2500 check today would represent less than a 1% cut in future benefits for all but the very lowest earners (Fig. 3, Panel B). This approach could also in principle be made optional without raising adverse selection concerns because the size of checks today would be unrelated to future benefits, so there would be no advantage for those who expect lower benefits in the future to disproportionately withdraw today.

An added benefit of a $2500 check is this approach is untethered from the policy risk associated with the Social Security program. The most salient policy risk relates to the resolution of the Social Security funding, which we discuss in Appendix B.3.

3.4. Retirement accounts withdrawals

Congress' COVID-19 stimulus package allows for penalty-free access to retirement accounts. This option is attractive to households: 30% of those with retirement accounts have already tapped them in the last two months, and, in April 2020, another 20% anticipate doing so in the near future (Berger, 2020).

However, relative to a Social Security-based approach, this has a much more muted effect on household liquidity (Panel B). Under this policy, the bottom 25% of the marketable wealth distribution have an additional 29 days on average before they are no longer able to finance their consumption, and the 25th percentile has only 9 days of support. The median, however, gets 3 months of support.

This is because the vast majority of workers made most vulnerable by the crisis do not have the funds in their retirement accounts to finance consumption today. As Fig. 1 illustrates, only half of workers have a retirement account, and in the bottom decile of marketable wealth, only 31% have non-zero retirement savings. Second, even for those who could gain liquidity by accessing retirement accounts, this requires liquidation of investment assets in the midst of a dramatic downturn (the S&P dropped by 16% in March alone).

3.5. Stimulus checks

Congress legislated a one-time issuance of $1200 COVID-19 relief check for all individuals earning less than $75,000.11 This approach does not boost household liquidity as much as providing 1% of Social Security benefits early: the median household receives $2200 from the stimulus, but $4200 from a 1% cut in future benefits.

These stimulus checks also cost over $290 billion.12 Already, the consequences for the U.S. deficit of COVID-19 spending are significant, with debt ballooning to over 100% of GDP (Swagel, 2020). There is widespread disagreement on the effect of large government debts and deficits in the economics literature (Blanchard, 2019; Rogoff, 2016). Given the low interest rate environment and lack of inflationary concerns, substantial focus on deficits might be misplaced. But it is worth noting that funding household consumption through Social Security is budget neutral and allows for liquidity constraints to be relaxed for a few months at least without increasing government liabilities.

3.6. Supplemental unemployment benefits

Since the onset of the pandemic through the end of July, unemployment benefits were increased by an extra $600 weekly, costing the U.S. government $260 billion to provide. While the median household receives $600 per week, there are still a large plurality of households that need more than this to avoid a shortfall. For those in the 25th percentile, this proposal provides an additional 105 days of liquidity, 10 days more than what 1% of Social Security benefits delivers. But policy can be designed differently so that the Social Security approach delivers more, e.g. 2% of benefits today lengthens the time to cash shortfall by more than supplemental UI.

Unlike a Social Security-based approach, paying very high UI benefits introduces labor supply disincentives. Recent work suggests that two-thirds of UI eligible workers are currently receiving benefits that exceed lost earnings (Ganong et al., 2020) and notes that such a significant expansion can impede reallocation responses needed to confront the COVID-19 shock (Barrero et al., 2020). Such concerns are consistent with a long literature the labor market impact of generous unemployment benefits, which can discourages workers from re-entering the workforce (Fredriksson and Holmlund, 2006; Lalive et al., 2006; Lentz, 2009). However, there is evidence that generous UI during recessions is optimal (Crépon et al., 2013). Yet as the economy reopens, these issues may become more relevant.

3.7. Other considerations and concerns

Despite policies already enacted to support households, many will find themselves unable to meet their financial obligations in the coming months. For those without access to credit, the result will be delinquency on obligations like rent and mortgage payments, that could result in eviction or bankruptcy. For those with access to credit, borrowers (many subprime) will take out loans at private rates that are on average 80 times more costly (Fig. 2).

Recent proposals for the provision of liquidity through Social Security suggest that workers be given the option to withdraw a portion of future benefits. But this approach raises concerns about adverse selection: workers who anticipate lower benefits in the future may disproportionately choose to withdraw. A mandatory benefits cut, in contrast, does not undermine the provision of longevity insurance through Social Security, and it allows all households to benefit from low interest rates. Those who need funds will have them; and those who do not, can save.

One issue for policymakers to weigh is that the lump-sum payment of Social Security benefits will hasten the depletion of the Social Security trust fund by a few years. Thus policymakers will be forced to weigh entitlement reform sooner. Another potential concern with providing access to future Social Security benefits is that this decreases the funds they will have to finance consumption in retirement. Indeed, today for the vast majority of Americans these savings are their largest source of income after leaving the workforce.

A key difference between a Social Security-based approach and other alternatives is its budget neutrality. A $2500 benefit check has no effect on government liabilities, as it can be financed by the issuance of bonds that are explicitly backed by a decrease in future Social Security benefits. This is in contrast to stimulus spending: the CARES Act required a budgetary outlay of $260 billion for 13 weeks of expanded unemployment insurance, and $290 billion for one-time checks to most families. While it is true that early access to retirement savings is also budget neutral, its ability to deliver liquidity to households is minimal, as described above.

4. Conclusion

In the United States, Social Security wealth is designed to be illiquid to provide longevity insurance that safeguards retirees in old age. The result is that for most American workers, illiquid forced savings exceed the liquid wealth they have on hand to finance consumption shocks. But optimal illiquidity is time-varying, and in downturns like this current crisis, there is a case to be made for allowing workers to access their illiquid Social Security wealth.

We illustrate the potential of this approach by carefully computing the market value of workers' Social Security benefits based on their age, earnings history, and estimated future earnings trajectories, adapting the approach of Catherine et al. (2020). We find that a minimal cut in scheduled Social Security benefits of just 1% is sufficient to finance household expenditure for two months. A related, and more administrable, alternative would be to provide workers their first $2500 in Social Security benefits today, which we show amounts to less than 1% of future benefits for nearly all workers. This provides more liquidity to households most vulnerable than alternative approaches already enacted, like penalty-free withdrawals from retirement savings accounts, and stimulus checks. It is also fiscally neutral and unlikely to introduce labor market distortions.

Footnotes

We thank Nathan Hendren and three anonymous referees for their comments. All errors are our own.

Stein et al. (2020) provides some detail on a recent Trump Administration proposal.

Sarin (2020) details these concerns.

As we discuss in Appendix B.1, this assumption does not really impact our findings.

The construction of this series is detailed in Appendix A.1.

Appendix B.2 discusses the implications of alternative assumptions for the equity premium and wage growth. For workers nearing retirement, the implications of alternative parameters are not meaningful. For young workers they are significant. For example, at age 20, an 8% (4%) equity premium decreases (increases) the present value of future benefits by around 40% (30%).

The dynamics across the age and income distribution are of some interest. For workers with the lowest earnings, a 1% benefit cut is actually of higher value for younger workers than older ones. This is because young workers with low past earnings have the potential to (and in expectation, will) rise in the income distribution over their time in the labor force, whereas for older workers, their earnings history is now fixed.

We compare to the FRED series PSAVERT. We details the computation of after-tax income in Appendix A.2, expenses in Appendix A.3, and the relationship between earnings and saving rates in Appendix B.4.

It is worth noting that there is evidence that households have cut normal times consumption during the COVID-19 pandemic across the earnings distribution Cox et al. (2020). In Appendix Figure B.6, we adjust to reflect this, seeing how the days to shortfall change if non-committed spending falls to 50% of after-tax income (around a 17% drop from baseline levels). The headline takeaway is unchanged: more than 80% of those in the bottom three deciles of the wealth distribution are within three months of a cash shortfall, even if their consumption falls.

This estimate was recently provided by Federal Reserve Chairman Jay Powell (Canilang et al., 2020).

There are many such recent examples, e. g. the months it took to disburse CARES Act stimulus checks, with 35 million individuals still without benefits as of June (Konish, 2020).

We take into account that, for heads of households, this number is increased to $112,500, and for couples filing jointly, the amount is $150,000 For people making over this, the stimulus is gradually phased out. Further, joint filers receive $2400 in stimulus plus an additional $500 for each qualifying dependent. Details are provided in Appendix A.6.

As estimated by the Committee for a Responsible Federal Budget (Fink, 2020). For more information, visit http://www.crfb.org/blogs/visualization-cares-act.

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpubeco.2020.104243.

Appendix A. Supplementary material

This includes details on our data (Appendix A), alternatives assumptions to those in our main specification (Appendix B), and calibrations for the simulation (Appendix C).

References

- Abel Andrew B. Capital accumulation and uncertain lifetimes with adverse selection. Econometrica. 1986;54:1079–1097. [Google Scholar]

- Baker Scott R., Bloom Nicholas, Davis Steven J., Terry Stephen J. COVID-induced economic uncertainty. NBER Working Paper No. 2020;26983 [Google Scholar]

- Barrero Jose Maria, Bloom Nick, Davis Steven J. COVID-19 is also a reallocation shock. Becker-Friedman Institute Working Paper No. 2020:2020–2059. [Google Scholar]

- Bartik Alexander W., Bertrand Marianne, Cullen Zoë B., Glaeser Edward L., Luca Michael, Stanton Christopher T. How are small businesses adjusting to COVID-19? Early evidence from a survey. NBER Working Paper No. 2020;26989 [Google Scholar]

- Benzoni Luca, Collin-Dufresne Pierre, Goldstein Robert S. Portfolio choice over the life-cycle when the stock and labor markets are Cointegrated. J. Financ. October 2007;62(5):2123–2167. [Google Scholar]

- Berger Sarah. 3 in 10 Americans withdrew money from retirement savings amid the coronavirus pandemic – and the majority spent it on groceries. Magnify Money. 2020 [Google Scholar]

- Beshears John, Choi James, Laibson David, Madrian Brigitte C., Skimmyhorn William. Vox EU; 2019. The Effect of Automatic Enrolment on Debt. [Google Scholar]

- Bhutta Neil, Dettling Lisa. Money in the bank? Assessing families’ liquid savings using the survey of consumer finances. FEDS Note. 2018 [Google Scholar]

- Biggs Andrew G., Rauh Joshua D. Funding direct payments to Americans through social security deferral. Stanford University Graduate School of Business Research Paper No. 2020;3580533 [Google Scholar]

- Blanchard Olivier. Public debt and low interest rates. Am. Econ. Rev. 2019;109:1197–1229. [Google Scholar]

- Canilang Sara, Duchan Cassandra, Kreiss Kimberly, Larrimore Jeff, Merry Ellen, Troland Erin, Zabek Mike. Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System. 2020. Report on the economic well-being of U.S. households in 2019, featuring supplemental data from April 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Catherine Sylvain. Working paper; 2019. Labor Market Risk and the Private Value of Social Security. [Google Scholar]

- Catherine Sylvain, Miller Max, Sarin Natasha. Working Paper. 2020. Social Security and Trends in Inequality. [Google Scholar]

- Cox Natalie, Ganong Peter, Noel Pascal, Vavra Joseph, Wong Arlene, Farrell Diana, Greig Fiona. Brookings Paper on Economic Activity; 2020. Initial Impacts of the Pandemic on Consumer Behavior: Evidence from Linked Income, Spending, and Savings Data. [Google Scholar]

- Crépon Bruno, Duflo Esther, Gurgand Marc, Rathelot Roland, Zamora Philippe. Do labor market policies have displacement effects? Evidence from a clustered randomized experiment. Q. J. Econ. 2013;128(2):531–580. [Google Scholar]

- Dynan Karen E., Skinner Jonathan, Zeldes Stephen P. Do the rich save more? J. Polit. Econ. 2004;112 [Google Scholar]

- Eckstein Zvi, Eichenbaum Martin, Peled Dan. Uncertain lifetimes and the welfare enhancing properties of annuity markets and social security. J. Public Econ. 1985;26:303–326. [Google Scholar]

- Fink Jenni. Stimulus checks cost $290 billion. A fraction of that could have changed response to coronavirus outbreak, experts say. Newsweek. 2020 [Google Scholar]

- Fredriksson Peter, Holmlund Bertil. Improving incentives in unemployment insurance: a review of recent research. J. Econ. Surv. 2006;20:357–386. [Google Scholar]

- Ganong Peter, Noel Pascal, Vavra Joseph. US unemployment insurance replacement rates during the pandemic. Becker-Friedman Institute Working Paper No. 2020;2020-62 doi: 10.1016/j.jpubeco.2020.104273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geanokoplos John, Zeldes Stephen P. 2010. Market Valuation of Accrued Social Security Benefits; pp. 213–233. [Google Scholar]

- Gormsen Niels Joachim, Koijen Ralph S.J. University of Chicago, Becker Friedman Institute for Economics Working Paper No. 2020–22; 2020. Coronavirus: Impact on Stock Prices and Growth Expectations. [Google Scholar]

- Gürkaynak Refet, Sack Brian, Wright Jonathan. vol. 5. 2008. The TIPS Yield Curve and Inflation Compensation. (Finance and Economics Discussion Series, 2008). [Google Scholar]

- Guvenen Fatih, Karahan Fatih, Ozkan Serdar, Song Jae. What do data on millions of U.S. workers reveal about life-cycle earnings risk? SSRN Electron. J. 2019 NBER Working Paper No. 20913. [Google Scholar]

- Hosseini Roozbeh. Adverse selection in the annuity market and the role for social security. J. Polit. Econ. 2015;123:941–984. [Google Scholar]

- Konish Lorie. CNBC; 2020. 35 Million Stimulus Checks Are Still Outstanding. What you Need to Know if You’re Waiting for your Money. [Google Scholar]

- Lalive Rafael, van Ours Jan, Zweimüller Josef. How changes in financial incentives affect the duration of unemployment. Rev. Econ. Stud. 2006;73(4):1009–1038. [Google Scholar]

- Lentz Rasmus. Optimal unemployment insurance in an estimated job search model with savings. Rev. Econ. Dyn. 2009;12:37–57. [Google Scholar]

- Maurer Raimond, Mitchell Olivia S. Evaluating lump sum incentives for delayed social security claiming. Public Policy and Aging Report. 2018;28:S15–S21. [Google Scholar]

- Maurer Raimond, Mitchell Olivia S., Rogalla Ralph, Siegelin Ivonne. Accounting and actuarial smoothing of retirement payouts in participating life annuities. Insurance: Mathematics and Economics. 2016;71:268–283. [Google Scholar]

- Munnell Alicia H., Chen Anqi. Center for Retirement Research at Boston College; Technical Report, Chestnut Hill, MA: 2019. Are Social Security's Actuarial Adjustments Still Correct? [Google Scholar]

- Rogoff Kenneth. MIT Press; Cambridge: 2016. Progress and Confusion: The State of Macroeconomic Policy. [Google Scholar]

- Sarin Natasha. Bloomberg; 2020. Tapping Social Security Would Be a Big Mistake. [Google Scholar]

- Stein Jeff, Dawsey Josh, Hudson John. Top white house advisers, unlike their boss, increasingly worry stimulus spending is costing too much. Wash. Post. 2020 [Google Scholar]

- Swagel Phill. Congressional Budget Office; 2020. CBO’s Current Projections of Output, Employment, and Interest Rates and a Preliminary Look at Federal Deficits for 2020 and 2021. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

This includes details on our data (Appendix A), alternatives assumptions to those in our main specification (Appendix B), and calibrations for the simulation (Appendix C).