Abstract

Background

COVID-19 pandemic has disrupted the global health systems worldwide. According to the tremendous rate of interhuman transmission via aerosols and respiratory droplets, severe measures have been required to contain contagion spread. Accordingly, medical and surgical maneuvers involving the respiratory mucosa and, among them, transnasal transsphenoidal surgery have been charged of maximum risk of spread and contagion, above all for healthcare professionals.

Method

Our department, according to the actual COVID-19 protocol national guidelines, has suspended elective procedures and, in the last month, only three patients underwent to endoscopic endonasal procedures, due to urgent conditions (a pituitary apoplexy, a chondrosarcoma causing cavernous sinus syndrome, and a pituitary macroadenoma determining chiasm compression). We describe peculiar surgical technique modifications and the use of an endonasal face mask, i.e., the nose lid, to be applied to the patient during transnasal procedures for skull base pathologies as a further possible COVID-19 mitigation strategy.

Results

The nose lid is cheap, promptly available, and can be easily assembled with the use of few tools available in the OR; this mask allows to both operating surgeon and his assistant to perform wider surgical maneuvers throughout the slits, without ripping it, while limiting the nostril airflow.

Conclusions

Transnasal surgery, transgressing respiratory mucosa, can definitely increase the risk of virus transmission: we find that adopting further precautions, above all limiting high-speed drill can help preventing or at least reducing aerosol/droplets. The creation of a non-rigid face mask, i.e., the nose lid, allows the comfortable introduction of instruments through one or both nostrils and, at the same time, minimizes the release of droplets from the patient’s nasal cavity.

Keywords: Nose lid, COVID-19, Transnasal surgery, Pituitary surgery, Endoscopic endonasal skull base surgery

Introduction

COVID-19 resulting from the new coronavirus strain (SARS-CoV-2) represents an unprecedented challenge for the global health system.

Since its appearance in Wuhan, China, in December 2019, it has rapidly spread worldwide up to be classified as a pandemic by the World Health Organization (WHO) on March 12, 2020 [3].

The interhuman transmission is the result of droplets’ projection toward another host or via human contact (e.g., handshaking) or through an inert surface [25]: the estimated half-life of SARS-CoV-2 in the droplets has been estimated to range between 1.1 to 1.2 h and it should be minded that the use of a common N95 mask does not get the risk of contagion down to zero [4, 13].

All over the world, ‘lock down’ and ‘social distancing’ have been key strategies to control infection outbreak. A great amount of information concerning the circulation of the infection among healthcare professionals has pointed out equal volume of issues within the scientific community, in particular regarding the best strategies to contain the transmission of the virus in the intrahospital environment [19].

Due to alarming increase of cases affected by this contagious disease, many hospitals have decreased or stopped elective interventions and moved their effort and personnel to admit and take care of patients affected by COVID-19 [12].

In particular, many questions have arisen about the safety of performing medical and surgical maneuvers involving the respiratory mucosa and, in the field of neurosurgery, transnasal transsphenoidal surgery has been charged of maximum risk of spread and contagion, above all for healthcare professionals. [24]

However, patients’ needs cannot remain unfulfilled, so that we had to embrace the great challenge of continuing assistance at least for urgent and non-deferrable cases, while reducing the risks of this tremendous infectious disease.

Transnasal pituitary and skull base surgery is performed in a narrow longitudinal canal: the possibility that aerosols and droplets from the nostrils escape aspiration is described and the evidence that, subsequently, they could be inhaled by surgeons has been described [22]. The adoption of correct strategies to obtain a reduction of human contacts between medical personnel and patients along with the use of adequate PPE for both parties is crucial to keep the practice safe [1].

Accordingly, several groups developed a cogent and “maximally safe” protocol to give most appropriate treatment to the patients, while minimizing the risks of COVID-19 diffusion [7, 17, 19].

Herein, we report further tailored preventive measures we adopted during non-deferrable endoscopic endonasal surgery in order to reduce the possibility of transmission.

Materials and methods

Patient selection

Our department, according to the actual COVID-19 protocol national guidelines, has suspended elective procedures and reviewed our criteria of prioritization [21]. Accordingly, we retain that a pituitary/skull base procedure can be considered non-deferrable upon the presence of

pituitary apoplexy associated with neurological defects;

tumors with massive suprasellar and/or supradiaphragmatic component with CSF circulation obstacle and/or hydrocephalus and/or intracranial hypertension signs;

At admission, patients are screened via interview and temperature is registered. Upon any suspicion of COVID-19, the infectivologist will be consulted in order to rule out the workflow; in any case, whether delaying surgery increases risks, precautions as for positive patients are required.

However, it should be minded that the certainty of COVID-19 negativity status is somehow difficult to assess: many COVID-19 cases are asymptomatic, and the reliability of screening tests is often limited and eventually low.

As general rule though, basic precautions, i.e., accurate and frequent hand washing, wearing a surgical mask and social distancing should be taken regardless of the patient Covid-19 status [10]; further peculiar precautions should be adopted in addition during critic procedures involving the respiratory mucosa, such as oro-tracheal aspiration, intubation, extubation, and/or when performing transnasal, transoral surgery, being essential to distinguish COVID-19-positive patients from the negative ones [6, 10, 11, 19].

Hence, in the last month, only three patients required urgent treatment, respectively, for the treatment of a pituitary apoplexy, a chondrosarcoma causing cavernous sinus syndrome and a pituitary macroadenoma determining chiasm compression. Once we cleared COVID-19 status (telephone interview and serological exam were run), we decided to adopt endoscopic endonasal approach in all these cases.

Measures inside the OR

Only surgeons and nurses directly involved in the procedures have been admitted to the theater; it was mandatory for each of them to wear maximum level PPE [6, 11, 20, 21]: FFP2 mask, covered by surgical mask, disposable gowns and caps, face screen.

Technical consideration

Considering all the above, we retained useful to adopt peculiar surgical technique modifications, in order to further limit the spread of droplets and aerosols [3, 11, 24]

Before starting, cottonoid pledgets soaked with diluted iodopovidone are placed and left in place for at least 5 min to rinse off mucosa from any contamination [5];

After usual nasal pyramid sterile draping, an endonasal surgery facial mask, namely a nose lid, is assembled: a sterile non-latex glove layer is used to cover nostril and fixed with adhesive protection film over the nasal bridge; initially, two and then three narrow slit cut are placed over the nares to let instruments enter the nostrils (Figs. 1, 2, and 3).

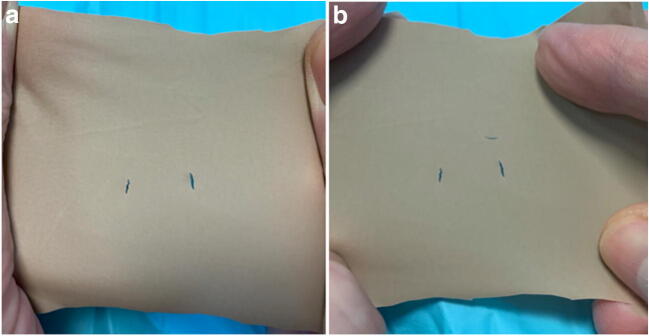

Fig. 1.

Pictures showing the layer of sterile non-latex glove with a two and b three slit cuts, being used as nose lid. Without any instrument that pierces it, the cuts are minimal

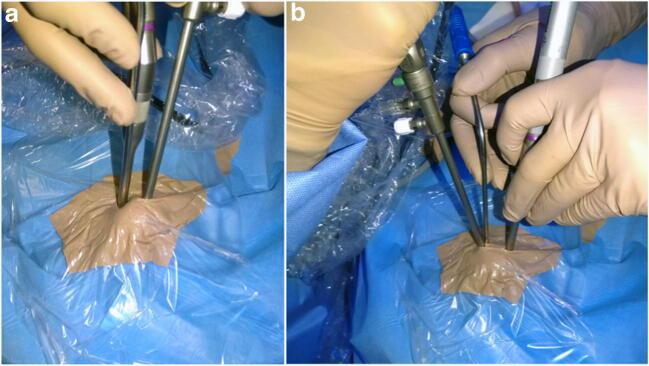

Fig. 2.

Picture showing the intraoperative setting. The nose lid is fixed with adhesive protection film over the nasal bridge and instruments can slide through the slit cuts the lid adheres to their outer diameter. a The endoscope is inserted through one nostril, i.e., the right. b Three-four hands technique: the endoscope is held by assistant at the most superior aspect of the left nostril and the surgeon holds the instruments inside the right nostril and the suction tube beneath the endoscope

Fig. 3.

Picture showing the details of intraoperative setting demonstrating that air flow through the nose can be limited by the use of the nose lid. a The microdrill is inserted through the left nostril and the nose lid adheres to its outer diameter. b The endoscope and suction tube are inserted through one nostril, i.e., the right, in two different slit cuts. c The endoscope is inserted through the right nostril while the microdrill in the left one, each of them in the relative slit cut

The slit cuts permit to limit the empty space of the nares allowing the entrance and exit only of the surgical instruments. The procedure then has been run as usual throughout into 3 steps: the nasal, the sphenoid, and the sellar phases.

A corridor between middle turbinates and the nasal septum is created and thereafter the nasal septum is detached from the sphenoid rostrum with blunt instruments. Cautery is limited as much as possible. The anterior wall of the sphenoid sinus is widely opened with osteotomes and rongeurs preferably and opening of the sellar floor is performed using chisel and hammer; microdrill with continuous irrigation, to reduce as much as possible the spreading of aerosol and bone dust, is used only to refine skull base opening upon the need.

Discussion

COVID-19 requires meticulous precautions in order of limiting person-to-person spread, being respiratory droplets deposited on the mucous membranes of mouth, nose, and eyes of nearby people and by close personal contact, the main routes of diffusion [2, 8, 18].

Accordingly, medical and surgical maneuvers involving the respiratory mucosa were immediately considered high-risk procedures [11, 16, 24].

It should be remembered that an otorhinolaryngologist was the first doctor to die from COVID-19.

Patients with symptomatic COVID-19 should be treated for neurosurgical disease only when surgery is not deferrable, namely when delaying it, the patient is exposed to concrete risks quoad vitam et valetudinem. Patients harboring COVID-19 represent the main source of viral transmission and therefore must be treated in an adequate in hospital setting with personnel being provided of adequate personal protective equipment (PPE). Additionally, a quite vast number of patients be carrier of SARS-CoV-2 and can be responsible for infection transmission.

Considering the above, caseload reduced, and routine activities have been cancelled and/or postponed if possible, to limit the spread of SARS-CoV2.

Neurosurgical scientific societies identified the transnasal skull base surgery, transoral and transfacial corridors, as the most riskful for diffusion of COVID-19 and also recommended to spare the opening of paranasal cavities and mastoids during transcranial corridors [7, 19–21, 23]. To our knowledge, “maximally safe” protocols for performing neurosurgical procedures, while minimizing the risks of COVID-19 diffusion, include the use of adequate PPE, OR settings, and the advice of reducing aerosol/droplets generating maneuvers [15, 19, 21].

Our study reports the use of a face mask, namely a nose lid (Figs. 1 and 2), to be applied to the patient during endonasal procedures for skull base pathologies as a further possible COVID-19 mitigation strategy. Numerous models of face masks have been proposed and tested by individual users, researchers, doctors, and commercial entities with varying degrees of success in other disciplines [9, 14]. At the moment, in our field, there are no models of face masks to contain the spread of the virus.

In our case, the mask, i.e. the nose lid, it is cheap, promptly available and can be easily assembled with the use of a few tools that we all have available in the OR. The necessary materials include a non-latex glove and sterile protective film. This mask allows to both operating surgeon and his assistant to perform wider surgical maneuvers throughout the slits, without ripping it, while limiting the nostril airflow.

Conclusions

Transnasal surgery, transgressing respiratory mucosa, can definitely increase the risk of virus transmission: therefore, more stringent protective and preventive measures are mandatory. Endonasal endoscopic surgical interventions can be safely performed, if necessary, only respecting correct protocols and wearing adequate personal protective equipment.

We find that adopting further precautions, above all limiting high-speed drill, can help preventing or at least reducing aerosol/droplets.

Besides, the creation of a non-rigid face mask, i.e., the nose lid, allows the comfortable introduction of instruments through one or both nostrils and, at the same time, minimizes the release of droplets from the patient’s nasal cavity.

Nonetheless, it remains advisable to strictly adhere to COVID-19 protocols and carefully evaluate patients and procedures, in order to ensure safety and eventually limit the contagion.

Funding information

No funding was received for this research.

Compliance with ethical standards

Ethical approval

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Informed consent

For this type of study, formal consent is not required.

This article does not contain any studies with human participants performed by any of the authors.

Conflict of interest

All authors certify that they have no affiliations with or involvement in any organization or entity with any financial interest (such as honoraria; educational grants; participation in speakers’ bureaus; membership, employment, consultancies, stock ownership, or other equity interest; and expert testimony or patent-licensing arrangements), or non-financial interest (such as personal or professional relationships, affiliations, knowledge, or beliefs) in the subject matter or materials discussed in this manuscript.

Footnotes

This article is part of the Topical Collection on Neurosurgical technique evaluation

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Ali Y, Alradhawi M, Shubber N, Abbas AR. Personal protective equipment in the response to the SARS-CoV-2 outbreak - a letter to the editor on "World Health Organization declares global emergency: a review of the 2019 novel coronavirus (COVID-19)" (Int J Surg 2020; 76:71-6) Int J Surg. 2020;78:66–67. doi: 10.1016/j.ijsu.2020.04.051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Anderson EL, Turnham P, Griffin JR, Clarke CC (2020) Consideration of the aerosol transmission for COVID-19 and public health. Risk Anal. 10.1111/risa.13500 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 3.Anderson RM, Heesterbeek H, Klinkenberg D, Hollingsworth TD. How will country-based mitigation measures influence the course of the COVID-19 epidemic? Lancet. 2020;395:931–934. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30567-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Boškoski I, Gallo C, Wallace MB, Costamagna G (2020) COVID-19 pandemic and personal protective equipment shortage: protective efficacy comparing masks and scientific methods for respirator reuse. Gastrointest Endosc. 10.1016/j.gie.2020.04.048 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 5.Cappabianca P, Cavallo LM, Solari D, Stagno V, Esposito F, de Angelis M. Endoscopic endonasal surgery for pituitary adenomas. World Neurosurg. 2014;82:S3–S11. doi: 10.1016/j.wneu.2014.07.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Castelnuovo P, Turri-Zanoni M, Karligkiotis A, Battaglia P, Pozzi F, Locatelli DISBSB, Bernucci C, Iacoangeli M, Krengli M, Marchetti M, Pareschi R, Pompucci A, Rabbiosi D (2020) Skull base surgery during the Covid-19 pandemic: the Italian skull base society recommendations. Int Forum Allergy Rhinol. 10.1002/alr.22596 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 7.Chaves ALF, Castro AF, Marta GN, Junior GC, Ferris RL, Giglio RE, Golusinski W, Gorphe P, Hosal S, Leemans CR, Magne N, Mehanna H, Mesia R, Netto E, Psyrri A, Sacco AG, Shah J, Simon C, Vermorken JB, Kowalski LP. Emergency changes in international guidelines on treatment for head and neck cancer patients during the COVID-19 pandemic. Oral Oncol. 2020;107:104734. doi: 10.1016/j.oraloncology.2020.104734. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.David AP, Jiam NT, Reither JM, Gurrola JG, Aghi M, El-Sayed IH (2020) Endoscopic skull base and transoral surgery during the COVID-19 pandemic: minimizing droplet spread with a negative-pressure otolaryngology viral isolation drape (NOVID). Head Neck. 10.1002/hed.26239 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 9.Erickson MM, Richardson ES, Hernandez NM, Bobbert DW, Gall K, Fearis P (2020) Helmet modification to PPE with 3D printing during the COVID-19 pandemic at Duke University Medical Center: a novel technique. J Arthroplasty. 10.1016/j.arth.2020.04.035 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 10.Francis N, Dort J, Cho E, Feldman L, Keller D, Lim R, Mikami D, Phillips E, Spaniolas K, Tsuda S, Wasco K, Arulampalam T, Sheraz M, Morales S, Pietrabissa A, Asbun H, Pryor A (2020) SAGES and EAES recommendations for minimally invasive surgery during COVID-19 pandemic. Surg Endosc. 10.1007/s00464-020-07565-w [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 11.Givi B, Schiff BA, Chinn SB, Clayburgh D, Iyer NG, Jalisi S, Moore MG, Nathan CA, Orloff LA, O'Neill JP, Parker N, Zender C, Morris LGT, Davies L (2020) Safety recommendations for evaluation and surgery of the head and neck during the COVID-19 pandemic. JAMA Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 10.1001/jamaoto.2020.0780 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 12.Grelat M, Pommier B, Portet S, Amelot A, Barrey C, Leroy HA, Madkouri R (2020) Covid-19 patients and surgery: guidelines and checklist proposal. World Neurosurg. 10.1016/j.wneu.2020.04.155 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 13.Iorio-Morin C, Hodaie M, Sarica C, Dea N, Westwick HJ, Christie SD, McDonald PJ, Labidi M, Farmer JP, Brisebois S, D'Aragon F, Carignan A, Fortin D (2020) Letter: The Risk of COVID-19 infection during neurosurgical procedures: a review of severe acute respiratory distress syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) modes of transmission and proposed neurosurgery-specific measures for mitigation. Neurosurgery. 10.1093/neuros/nyaa157 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 14.Ishack S, Lipner SR (2020) Applications of 3D printing technology to address COVID-19 related supply shortages. Am J Med. 10.1016/j.amjmed.2020.04.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 15.Kowalski LP, Sanabria A, Ridge JA, Ng WT, de Bree R, Rinaldo A, Takes RP, Makitie AA, Carvalho AL, Bradford CR, Paleri V, Hartl DM, Vander Poorten V, Nixon IJ, Piazza C, Lacy PD, Rodrigo JP, Guntinas-Lichius O, Mendenhall WM, D'Cruz A, Lee AWM, Ferlito A (2020) COVID-19 pandemic: effects and evidence-based recommendations for otolaryngology and head and neck surgery practice. Head Neck. 10.1002/hed.26164 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 16.Kulcsar MA, Montenegro FL, Arap SS, Tavares MR, Kowalski LP. High risk of COVID-19 infection for head and neck surgeons. Int Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2020;24:e129–e130. doi: 10.1055/s-0040-1709725. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lo YT, Yang Teo NW, Ang BT (2020) Editorial. Endonasal neurosurgery during the COVID-19 pandemic: the Singapore perspective. J Neurosurg 1–3. 10.3171/2020.4.JNS201036 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 18.Luan RS, Wang X, Sun X, Chen XS, Zhou T, Liu QH, Lü X, Wu XP, Gu DQ, Tang MS, Cui HJ, Shan XF, Ouyang J, Zhang B, Zhang W, Sichuan University Covid- ERG Epidemiology, treatment, and epidemic prevention and control of the coronavirus disease 2019: a review. Sichuan Da Xue Xue Bao Yi Xue Ban. 2020;51:131–138. doi: 10.12182/20200360505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Patel ZM, Fernandez-Miranda J, Hwang PH, Nayak JV, Dodd R, Sajjadi H, Jackler RK (2020) Letter: precautions for endoscopic transnasal skull base surgery during the COVID-19 pandemic. Neurosurgery. 10.1093/neuros/nyaa125 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 20.Patel ZM, Fernandez-Miranda J, Hwang PH, Nayak JV, Dodd RL, Sajjadi H, Jackler RK (2020) In reply: precautions for endoscopic transnasal skull base surgery during the COVID-19 pandemic. Neurosurgery. 10.1093/neuros/nyaa156 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 21.Ramakrishna R, Zadeh G, Sheehan JP, Aghi MK (2020) Inpatient and outpatient case prioritization for patients with neuro-oncologic disease amid the COVID-19 pandemic: general guidance for neuro-oncology practitioners from the AANS/CNS Tumor Section and Society for Neuro-Oncology. J Neurooncol. 10.1007/s11060-020-03488-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 22.van Doremalen N, Bushmaker T, Morris DH, Holbrook MG, Gamble A, Williamson BN, Tamin A, Harcourt JL, Thornburg NJ, Gerber SI, Lloyd-Smith JO, de Wit E, Munster VJ. Aerosol and surface stability of SARS-CoV-2 as compared with SARS-CoV-1. N Engl J Med. 2020;382:1564–1567. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc2004973. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Vukkadala N, Qian ZJ, Holsinger FC, Patel ZM, Rosenthal E (2020) COVID-19 and the otolaryngologist: preliminary evidence-based review. Laryngoscope. 10.1002/lary.28672 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 24.Workman AD, Welling DB, Carter BS, Curry WT, Holbrook EH, Gray ST, Scangas GA, Bleier BS (2020) Endonasal instrumentation and aerosolization risk in the era of COVID-19: simulation, literature review, and proposed mitigation strategies. Int Forum Allergy Rhinol. 10.1002/alr.22577 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 25.Yu J, Ouyang W, Chua MLK, Xie C (2020) SARS-CoV-2 transmission in patients with cancer at a Tertiary Care Hospital in Wuhan, China. JAMA Oncol. 10.1001/jamaoncol.2020.0980 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]