Abstract

COVID-19 was declared a global pandemic by the WHO and has affected millions of patients around the world. COVID-19 disproportionately affects persons with endocrine conditions, thus putting them at an increased risk for severe disease. We discuss the mechanisms that place persons with endocrine conditions at an additional risk for severe COVID-19 and review the evidence. We also suggest precautions and management of endocrine conditions in the setting of global curfews being imposed and offer practical tips for uninterrupted endocrine care.

Key words: COVID-19, endocrinology, diabetes, hypertension, obesity, metabolic syndrome

Introduction

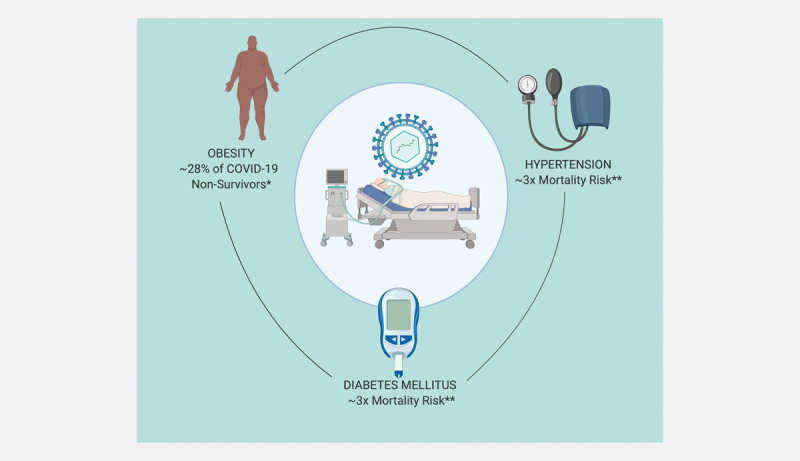

Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) was declared a pandemic by the World Health Organization (WHO) on March 11, 2020 with over 3,059,642 cases and 211,028 deaths being reported from 213 countries and territories at the time of writing this review 1 2 . There is increasing evidence to suggest that patients with endocrinopathies such as diabetes mellitus (DM), hypertension (HTN), obesity and cardiovascular disease are at higher risk for COVID-19 related complications 3 . Reports from the UK and US have indicated a high prevalence of DM and obesity in COVID-19 non-survivors and severe cases 4 5 . In the US, the most commonly reported cardiometabolic comorbidities associated with COVID-19 are HTN (49.7%), obesity (48.3%), DM (28.3%), and cardiovascular disease (27.8%) ( Fig. 1 ) 6 . Furthermore, DM is the most common comorbidity in COVID-19 deaths according to one report 4 . Given these data, both the WHO and the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) list DM, HTN and obesity as risk factors for development of more severe COVID-19 outcomes 6 7 8 . In this review, we summarize common endocrinopathies associated with COVID-19.

Fig. 1.

Clinical impact of endocrine conditions on COVID-19 *Louisiana Department of Health Updates for 3/27/2020. http://ldh.la.gov **ref 3 .

Overview of the Novel Coronavirus-Cell Interaction

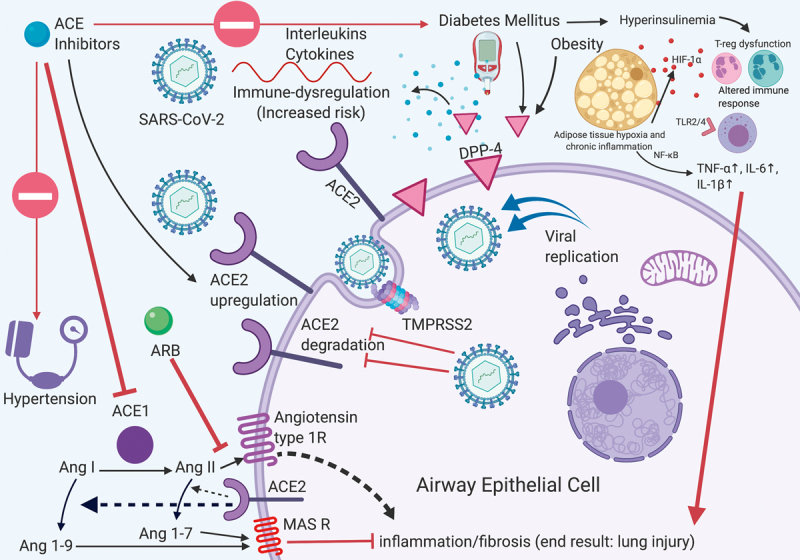

Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) is a betacoronavirus that was identified as the causative pathogen of COVID-19 9 . This virus enters the intracellular environment by binding of the spike protein on its receptor binding domain (RBD) to angiotensin converting enzyme 2 (ACE2) which is present on the epithelial surface of human cells ( Fig. 2 ) 9 . Notably, ACE2 is a distinct molecule from the well-known angiotensin converting enzyme 1 (ACE1), which is a therapeutic target. After attachment to ACE2, the SARS-CoV-2 recruits a serine protease TMPRSS2, which facilitates viral protein priming and cytoplasmic entry ( Fig. 2 ) 10 . ACE2 is cleaved by a protease ADAMTS17, which in turn reduces its surface expression. After entering the cytoplasm, the virus enters the nucleus via an endosomal pathway and viral replication ensues 10 .

Fig. 2.

Molecular interplay between endocrine conditions, ACE modulation and COVID-19: Illustration of endocrine conditions, mitigating factors and associated risks of COVID-19. Red arrows demonstrate deleterious effects and block arrows reflect inhibition. ACE: Angiotensin converting enzyme; ARB: Angiotensin receptor blocker; Ang: Angiotensin; DPP-4: Dipeptidyl peptidase-4.

Diabetes mellitus

Pathophysiology and risk

There are several reasons why DM may aggravate the risk of severe COVID-19. First, DM may facilitate cell entry of SARS-CoV-2 by augmenting the surface expression of ACE2 through hyperinsulinemia-mediated reduction in ADAMTS17 activity 11 12 13 . In humans, higher expression of ACE2 protein in the pancreatic islets was associated with hyperglycemia and diabetes caused by SARS-coronavirus (SARS-CoV) another coronavirus that uses ACE2 for cell entry, suggesting that SARS-CoV-2 may act through a similar mechanism 14 . Second, ACE2 modulators such as ACE1 inhibitors (ACEi), angiotensin receptor blockers (ARBs), and thiazolidenediones, which are used frequently in DM may upregulate ACE2 expression 9 15 . Third, DM is associated with complement defects and reduced antigen stimulated IL-6, IL-8 and TNF-α 16 17 ; and impairment of T-regulator cells (Tregs) and antigen presenting cells (APCs) that may exacerbate the immunodeficiency 18 . Fourth, co-existing HTN and obesity, acting via HIF-1α and toll-like receptors, may contribute to the pre-existing chronic inflammation leading to impaired immune-mediated clearance of SARS-CoV-2 18 19 . Lastly, dipeptidyl peptidase-4 (DPP-4), a surface glycoprotein, which degrades glucagon like peptide 1 (’GLP-1’, an incretin hormone), is known to be elevated in DM and obesity 20 21 22 , and also functions as a surface receptor for coronaviruses 23 24 . Although the latter is yet to be shown for SARS-CoV-2, the unique role of DPP-4 in coronavirus infections makes DPP-4 inhibition a possible therapeutic target, which may work both by reducing DPP-4 expression and offsetting the cytokine mediated end organ damage 19 25 . This assessment is further strengthened by evidence that DPP-4 inhibition showed anti-inflammatory effects in pre-clinical human studies 19 26 27 . Taken together, patients with DM may be predisposed to cytokine storms resulting in end organ injury and mortality ( Fig. 2 ) 28 .

A review of sixteen clinical studies with a total of 9,011 patients with COVID-19 revealed a prevalence of DM between 2.0% and 56.6% [median (IQR)%: 13.2 (9.10–23.70)], highlighting the high risk that patients with DM face in the wake of the global COVID-19 pandemic ( Table 1 ) 3 6 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 37 38 39 40 41 42 43 . Additionally, hyperglycemia has been seen in 35–58% of inpatients with COVID-19 suggesting the burden of impaired glucose metabolism 29 34 . Other studies have reported a higher DM prevalence in severe cases of COVID-19 when compared to mild cases (14.3 vs. 5.0%, p= 0·009) 39 , as well as an increased mortality risk and an increased case fatality rate in patients with DM (~3x, Fig. 1 ) 3 , in comparison to persons without DM (7.3 vs. 2.3%, respectively), indicating the amplified risk to patients with DM 44 . In a different study DM was highlighted as the most common comorbidity occurring in 41% of all COVID-19 deaths 4 . Additionally, one study noted that COVID-19-affected patients with DM as a sole comorbidity had a 16.5% mortality rate compared to 0% in comorbidity free COVID-19 patients, whereas another reported poor outcomes in COVID-19 inpatients with uncontrolled hyperglycemia compared to their euglycemic counterparts 45 46 . The US CDC included DM as a risk factor for severe COVID-19 in their clinical guidance 8 .

Table 1 Prevalence of diabetes mellitus (DM) and hypertension (HTN) in patients with COVID-19.

| Title | Author | Sample | Diabetes prevalence | Hypertension prevalence | Obesity prevalence |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Clinical Course and Outcomes of Critically Ill Patients With SARS-CoV-2 Pneumonia in Wuhan, China: A Single-Centered, Retrospective, Observational Study | Yang et al. 29 | 52 critically sick patients | 17% | NR | NR |

| Clinical Characteristics of Coronavirus Disease 2019 in China | Guan et al. 82 | 1099 patients | 7.40% | 15% | NR |

| Clinical characteristics of 140 patients infected with SARS-CoV-2 in Wuhan, China | Zhang et al. 31 | 140 patients | 12.10% | 30% | NR |

| Clinical Characteristics of 138 Hospitalized Patients With 2019 Novel Coronavirus-Infected Pneumonia in Wuhan, China | Wang et al. 32 | 138 patients | 10.10% | 31.20% | NR |

| Clinical findings in a group of patients infected with the 2019 novel coronavirus (SARS-Cov-2) outside of Wuhan, China: retrospective case series | Xu et al. 33 | 62 patients | 2% | 8% | NR |

| Epidemiological and clinical characteristics of 99 cases of 2019 novel coronavirus pneumonia in Wuhan, China: a descriptive study | Chen et al. 34 | 99 patients | 13% | NR | NR |

| A familial cluster of pneumonia associated with the 2019 novel coronavirus indicating person-to-person transmission: a study of a family cluster | Chan et al. 41 | Family of 6 patients | 16% | 32% | NR |

| Clinical course and risk factors for mortality of adult inpatients with COVID-19 in Wuhan, China: a retrospective cohort study | Zhou et al. 3 | 191 patients | 19% | 30% | NR |

| Analysis of Myocardial Injury and Cardiovascular Diseases in Critical Patients with New Coronavirus Pneumonia | Chen et al. 83 | 150 patients | 13.3% | 32.6% | NR |

| A Trial of Lopinavir-Ritonavir in Adults Hospitalized with Severe Covid-19 | Cao et al. 36 | 199 patients | 11.16% | NR | NR |

| Characteristics and Outcomes of 21 Critically Ill Patients With COVID-19 in Washington State | Arentz et al. 38 | 21 critically sick patients | 33.3% | NR | NR |

| Epidemiologic and Clinical Characteristics of 91 Hospitalized Patients with COVID-19 in Zhejiang, China: A retrospective, multi-centre case series. | Qian et al. 40 | 91 patients | 8.79% | 16.48% | NR |

| Host susceptibility to severe COVID-19 and establishment of a host risk score: findings of 487 cases outside Wuhan. | Shi et al. 39 | 487 patients | 6% | 20.3% | NR |

| Clinical Characteristics of Covid-19 in New York City | Goyal et al. 42 | 393 patients | 25.2% | 50.1% | 35.8% |

| Hospitalization Rates and Characteristics of Patients Hospitalized with Laboratory-Confirmed Coronavirus Disease 2019 — COVID-NET, 14 States, March 1–30, 2020 | Garg et al. 6 | 178 patients | 28.3% | 49.7% | 48.3% |

| Presenting Characteristics, Comorbidities, and Outcomes Among 5700 Patients Hospitalized With COVID-19 in the New York City Area | Richardson et al. 43 | 5700 patients | 56.6% | 33.8% | 41.7% |

NR: Not reported.

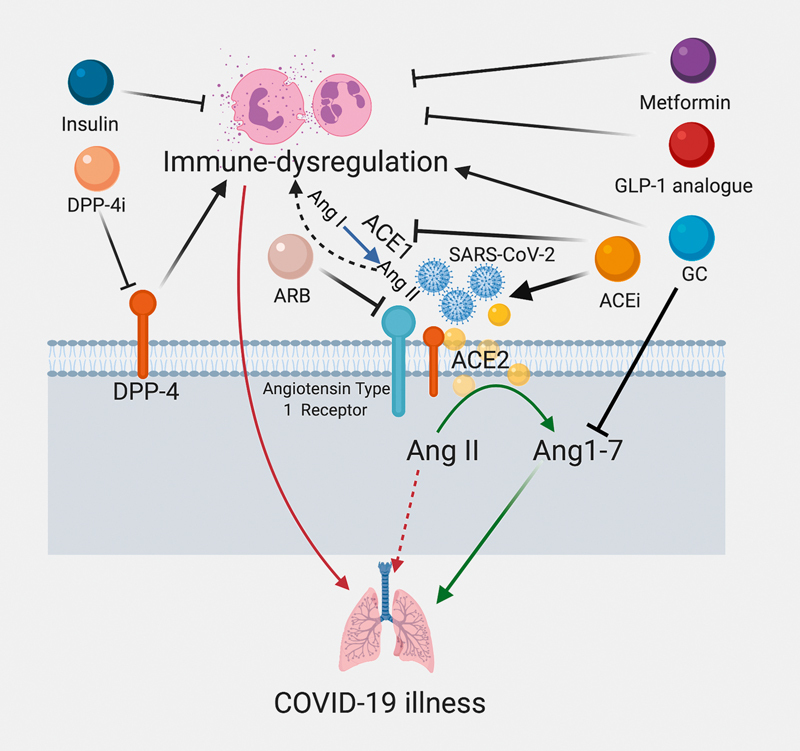

Evidence of an increased risk of long term metabolic complications in patients that have recovered from SARS, caused by SARS-CoV, raises concern for a possible increased risk for similar complications in COVID-19. This was demonstrated in a follow-up study of thirty one recovered SARS patients in comparison to healthy volunteers at 12 years that revealed abnormal glucose metabolism in 60% (vs. 16%), hyperlipidemia in 68% (vs. 40%), and cardiovascular abnormality in 44% (vs. 0%) of study participants 47 . It was speculated that the use of pulse dose glucocorticoids may have contributed to these long-term metabolic derangements 47 . Glucocorticoid use in hospitalized COVID-19 patients may also play a role in acute inpatient hyperglycemia. However, glucocorticoid use has fallen out of favor in the routine management of COVID-19 according to CDC and WHO guidelines 48 49 and evidence points to glucocorticoids attenuating anti-inflammatory angiotensin 1–7 levels and delaying viral clearance ( Fig. 3 ), providing a molecular basis for avoiding their universal use 50 51 . A clinical trial is currently underway to determine the efficacy of systemic glucocorticoid therapy in COVID-19 52 .

Fig. 3.

Effects of commonly used drugs in obesity, diabetes mellitus, and hypertension on immune dyregulation. Red arrows indicate negative clinical consequences, green arrows indicate positive clinical implications, black arrows reflect stimulation and block arrows signify inhibition. ACE: Angiotensin converting enzyme; ARB: Angiotensin receptor blockers; Ang: Angiotensin; DPP-4: Dipeptidyl peptidase-4; GLP-1: Glucagon like peptide-1; GC: Glucocorticoids.

Clinical approach

Recently, the American Diabetes Association (ADA) issued patient recommendations regarding preparedness and precautions for COVID-19 ( Table 2 ) including keeping updated contact information; ensuring adequate stocks of simple carbohydrates, medications and insulin; and ensuring availability of supplies such as rubbing alcohol, glucagon kits, ketone strips, soap and household items 53 . The American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists also emphasizes adequate emergency preparedness and provided a checklist of emergency plan action items to ensure the uninterrupted care of DM ( Table 2 ) 54 55 .

Table 2 Endocrinology and COVID-19: Resources and Links.

| Society | Resource | Web Link |

|---|---|---|

| American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists | Diabetes emergency plan (for patients) | http://mydiabetesemergencyplan.com |

| Endocrine Society | General resources for endocrinologists | https://www.endocrine.org |

| European Society of Endocrinology | General resources for endocrinologists | https://www.ese-hormones.org |

| Society for Endocrinology | General resources for endocrinologists | https://www.endocrinology.org/clinical-practice/covid-19-resources-formanaging- endocrine-conditions |

| Society for Endocrinology | Adrenal insufficiency positionstatement | https://www.endocrinology.org/news/item/14050/Coronavirus-advicestatement- for-patients-with-adrenal %2fpituitary-insufficiency |

| American Diabetes Association | Inpatient blood glucose management | https://care.diabetesjournals.org/content/43/Supplement_1/S193 |

| American Thyroid Association | Frequently asked questions | https://www.thyroid.org/covid-19/coronavirus-frequently-asked-questions |

| National Osteoporosis Foundation | Patients and Providers Fact Sheet | https://cdn.nof.org/wp-content/uploads/NOF-COVID-Factsheet_.pdf |

| National Center for Transgender Equality | Plan of Action | https://transequality.org/covid19/plan |

| The National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases | General guidelines | https://www.niddk.nih.gov/health-information/endocrine-diseases/adrenalinsufficiency- addisons-disease |

| Centers for Disease Control and Prevention | General guidelines | https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/index.html |

| World Health Organization | General guidelines | https://www.who.int/emergencies/diseases/novel-coronavirus-2019 |

From a clinical practice standpoint patient counseling should include discussing glycemic goals and sick day insulin dosing regimens, as well as adequate hydration and maintaining access to food (including nonperishable items, glucose and electrolyte tablets). Furthermore, adoption and continuation of a healthy diet and recommended 150 minutes of weekly exercise such as indoor walking and other physical distancing compatible exercises should be encouraged 56 . Recommended vaccinations for influenza, pneumococcal and other infections should be emphasized (based on CDC or equivalent local authority guidelines). The latter is of major importance since viral co-infection has been frequent in COVID-19 57 58 59 . Furthermore, patients should be notified of insulin availability without a prescription in many countries as a contingency measure (US, Canada, India, Mexico, etc.) 60 61 62 63 .

For inpatient hyperglycemia management, the blood glucose target recommended by the ADA Standards of Medical Care in Diabetes is 140–180 mg/dL for most critically-ill and non-critically ill patients, with more stringent glycemic goals (blood glucose 110–140 mg/dL) recommended for selected patients if hypoglycemia can be avoided 64 . However, specific glycemic targets for patients with COVID-19 have not been released by the ADA to date. In the aforementioned guidelines, the ADA recommends the consideration of more liberal glycemic goals (blood glucose>180 mg/dL) for patients that have severe comorbidities, are terminally ill, or where frequent glucose monitoring or close nursing supervision is not possible. In these patients less aggressive insulin regimens with the aim of minimizing glycosuria, dehydration, and electrolyte disturbances may be more appropriate, however clinical judgment combined with continuing assessment of clinical status that includes changes in the trajectory of glucose measures, illness severity, nutritional status, or concomitant medications that might affect glucose levels, should be incorporated into medical decision making. Furthermore, it is reasonable to discontinue sodium-glucose co-transporter-2 inhibitors (SGLT-2i) that have been associated with intravascular volume depletion and increased risk of euglycemic ketosis 56 . Discontinuation of sulfonylureas is also advisable, particularly in critical patients, where drug renal clearance may be compromised 56 . Chloroquine and hydroxochloroquine, which are under investigation for efficacy in the treatment of COVID-19, may cause hypoglycemia 65 66 . In contrast, antiviral drugs such as ritonavir and lopinavir, which were used for COVID-19 previously, are associated with hyperglycemia 67 . Use of these drugs should also be accompanied by adjustments in diabetes regimens.

Because of the need for flexible management, insulin remains the safest drug for the management of hyperglycemia in DM patients and has an added anti-inflammatory effect in the critical illness setting 68 . Importantly, DPP-4 inhibitors and GLP-1 receptor analogues may not only attenuate the chronic inflammatory state in DM but also have independent lung-protective and immunomodulatory effects (in pre-clinical studies) and may prove beneficial ( Fig. 3 ) 19 69 70 71 .

Panic-buying is a major threat in this crisis. Fortunately, to date, there is no report of a major household or medical supply shortage and clinicians should counsel patients against this practice to ensure adequate availability for others 72 73 74 .

Resources and future directions

The Endocrine Society has established a dedicated COVID-19 webpage with resources for clinicians and researchers with many other societies such as the European Society of Endocrinology and the Society for Endocrinology ( Table 2 ) 75 .

This pandemic has led to a fast-tracking of telemedicine. Authorities in the US, Canada and France announced wider coverage of telemedicine visits, which is likely to directly benefit patients with DM 76 77 . However, it is not known whether the telemedicine visits will suffice for insulin pump follow-up, which currently mandate inperson visits.

There are still many areas of uncertainty that warrant further investigation with respect to DM and COVID-19. Some of these include the differences between type 1 and type 2 DM, optimal vs. poor glycemic control, and the effect of age and other co-existing conditions in patients with DM among others.

Hypertension

Pathophysiology and risk

A high prevalence of HTN has been noted among patients with COVID-19, with HTN possibly predisposing to an elevated risk for more severe disease. The risk could stem from a variety of reasons. Foremost, HTN is associated with immune dysregulation, which manifests as higher IL-17 levels, abnormal natural killer cell function and cytotoxic T-cell anomalies partly reversible with mineralocorticoid receptor antagonists 78 79 . Other contributors include overactive sympathetic drive, dysregulated NFκB and elevations in the pro-inflammatory peptide, angiotensin II ( Fig. 2 ) 80 81 .

A review of twelve studies, which included data from 8,635 patients with COVID-19, revealed the prevalence of HTN to be between 8.0 and 50.1% [median (IQR)%: 30.6 (17.43–33.50)] ( Table 1 ) 3 6 30 31 32 33 35 37 39 40 41 42 43 82 83 . A US-based study reported a 50.1% prevalence of HTN 42 . Moreover, one study 34 of 191 patients found a 3-fold higher risk of mortality in patients with HTN while other studies reveled a 1.57–2.71-fold risk of severe COVID-19 illness 39 84 ( Fig. 1 ). Shi et al. also included HTN as one of three indices in a COVID-19 risk assessment score 39 . This risk may be further enhanced by the co-existence of DM, which is present in 60.2–85.8% of persons with HTN (depending on the diagnostic threshold used) 85 .

However, it should be noted that HTN is highly prevalent among the elderly, and the elderly are over-represented among COVID-19 patients requiring hospital admission and critical care. Thus, the risk attributed to HTN might be the result of reverse causality. The prevalence of HTN or DM may be greater in severe patients, but studies have failed to report if these comorbidities co-exist with others, hence increasing the risk for severity. Moreover, the associated risks currently remain associations. A comprehensive isolation of the exposure of HTN or DM has not been reported. Therefore the causal risk carried by these comorbidities individually, or together, has not been established and remains unclear.

Renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system and COVID-19

SARS-CoV-2 enters the human body through attachment to the ACE2 receptors that are present on the cell surface of type 2 alveolar epithelial cells in the lungs ( Fig. 2 ) 9 86 87 . These receptors are also present in other tissues, with tissue ACE2 levels not always correlating with plasma ACE2 activity 88 . Although ACEi/ARBs do not directly affect ACE2 activity, some studies in experimental animal models have shown that ACEi/ARBs can upregulate the expression and activity of ACE2 in certain tissues including the heart and kidney, but studies regarding their effects on ACE2 expression and activity in the lungs are lacking 89 90 . One study demonstrated increased intestinal messenger RNA levels of ACE2 in patients previously treated with ACEi but not in those treated with ARBs 91 . Equally, there are reports of higher ACE2 urinary levels in type 1 and 2 DM but the clinical implications of these findings remains unclear in the context of COVID-19 70 92 93 . In light of these findings, it has been proposed that ACEi/ARBs could enhance the risk for severe COVID-19 and re-evaluating their use has been suggested 94 95 96 . On the contrary, higher plasma ACE2 may bind SARS-CoV-2 and protect against lung and other tissue injury (shown in animal models) and this is proposed as a therapeutic target 97 . Furthermore, angiotensin 1–7 uptitrated by the use of ACEi/ARBs may offer immunoprotection and attenuate the severity of COVID-19 by acting via the Mas receptor pathway ( Fig. 2 ) 98 99 100 101 . Similarly, ACEi may reduce angiotensin II levels and attenuate immunodysregulation 102 . This position is further supported by other recent reviews that point to the confusing nature of these unproven assertions regarding greater risk to COVID-19 patients taking ACEi/ARBs 98 103 104 105 . No direct evidence to support the theoretical risk of ACEi/ARBs use with regards to COVID-19 severity has been published as of April 22, 2020. One clinical study reported milder COVID-19, improved immune function and lower viral loads in patients with HTN who were treated with ACEi/ARBs compared to those who were not 106 and better clinical outcomes in another study 107 . These findings refute the theoretical concerns about these agents and support their continued use ( Table 2 ) 106 107 .

Various societies have endorsed the continued use of ACEi/ARBs based on the lack of evidence of harm ( Table 2 ). The European Society of Cardiology released a statement strongly recommending “ that patients and physicians continue their usual anti-hypertensive therapy because there is no clinical or scientific evidence to suggest that treatment with ACEi or ARBs should be discontinued because of the Covid-19 infection ” 108 . Many others followed suit ( Table 2 ) 108 109 110 111 112 . The American Heart Association recently published a white paper reporting the lack of studies investigating and demonstrating evidence of harm 103 . A clinical trial, ’Recombinant Human Angiotensin Converting Enzyme 2 (rhACE2) as a Treatment for Patients With COVID-19 ’ (ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier: NCT04287686), is currently examining the role of ACE2 receptor modulation in COVID-19 and may provide conclusive evidence on this matter 113 114 .

Obesity

Pathophysiology and risk

Obesity is a state of chronic adipose tissue hypoxia leading to a pro-inflammatory state with increased levels of IL-1, IL-6, and TNF-α ( Figs. 2 and 3 ) 18 115 116 . The immunological dysfunction in obesity could also stem from T-cell insulin resistance and exhaustion 18 . We speculate that this would presumably lead to an altered immune response, not only to the virus but also to a future vaccine. One review raised the possibility of adipose tissue representing a SARS-CoV-2 target and reservoir, albeit no study reflecting this has been published to date 117 . Another study demonstrated prolonged influenza viral shedding in obese persons 118 . Likewise, the alteration of myeloid and lymphoid responses within the adipose tissue consequently leads to an aberration of adipokine profiles 117 119 . Similarly, obesity is linearly associated with raised C-reactive protein (CRP) levels, which is proximately triggered by adipocytic derived IL-6 115 120 . Not surprisingly, CRP has been correlated with severe disease, providing a pathophysiological link between obesity and poor COVID-19 outcomes 121 122 . There is also evidence to suggest attenuated Mas receptor signaling (of angiotensin 1–7) within the renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system may further aggravate the pre-existing immune dysregulation 123 124 . In addition, higher levels of pro-inflammatory DPP-4 levels seen in obesity and the consequent hyperinsulinemia may both independently exacerbate COVID-19 risks ( Figs. 2 and 3 ) 21 . While the benefits of DPP-4 inhibition are unproven, there is a clear anti-inflammatory and lung-protective effect of GLP-1 receptor analogues in obesity that may prove useful in mitigating risks for severe disease 71 125 . Furthermore, co-existing obesity hypoventilation syndrome and obstructive sleep apnea, both complications of obesity, may compromise respiratory function that could also account for the observed effects. Moreover, obesity is independently linked with a higher thrombosis risk that is especially relevant as COVID-19 has an increased predilection for microangiopathy and venous thrombosis 126 127 128 . The latter, in conjunction with compromised cardiorespiratory reserve, may acutely impede mechanical ventilation of critically-ill obese persons. Furthermore, it is vital for future investigations to analyze the link between patients’ anthropometric characteristics and severe COVID-19 since visceral adiposity is likely to represent a higher risk for COVID-19 illness 129 . On a more chronic basis, obesity poses an additional challenge both from a nursing and a rehabilitation standpoint 130 .

Recently, the Louisana Department of Health reported obesity as the third most common comorbidity (after DM and chronic kidney disease) associated with mortality, with a prevalence of 28% in COVID-19 non-survivors ( Fig. 1 ) 4 . Moreover, the CDC reported obesity being present in 48.3% of all COVID-19 hospitalized patients 6 . A review of three clinical studies, comprising of a total of 6,271 patients showed that obesity was prevalent in 35.8–48.3% [median (IQR)%: 41.7 (35.80–48.30)] of hospitalized COVID-19 patients ( Table 1 ) 6 42 43 . Another study noted obesity as an independent risk for COVID-19 hospitalization 131 . The National Health Service in the UK also reported obesity as a risk factor for severe disease and mortality in COVID-19 5 . In light of these data, the CDC updated their guidance to include a BMI>40 kg/m 2 as a risk factor for severe COVID-19 8 .

Common ’Bad’ actors in metabolic disease related cytokine storm

It is important to consider the cumulative pathophysiology of commonly described endocrinopathies and COVID-19 severity. In this section, we discuss plausible underlying mechanisms for severe COVID-19 in hosts with these conditions.

Betacoronaviruses, including SARS-CoV-2, enter human cells by binding to ACE2 in various tissues. However, betacoronaviruses such as MERS-CoV and SARS-CoV also directly infect immune cells. Specifically, MERS-CoV binds to monocytes and dendritic cells and SARS-CoV affects T-cells through DPP-4 receptors 132 . After being exposed to a betacoronavirus, monocytes, macrophages and dendritic cells release the proinflammatory cytokine IL-6. IL-6 has two major modes of pleiotropic signaling ( cis and trans ) 133 . Cis -signaling occurs when IL-6 attaches to its membrane bound receptors (mIL-6R) present on immune cells, triggering activation of other immune pathway cells such as T-cells, B-cells and natural killer cells and leading to further IL-6 release and immune activation. Pathological activation of this signaling leads to a cytokine release syndrome (CRS). Trans -signaling occurs when IL-6 binds to its soluble receptor (sIL-6R) that is present in vascular endothelium. This triggers the release of vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) and monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 (MCP-1). Together with reduction of E-cadherin, the result is increased vascular permeability and leakage causing syndromes such as CRS, acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) and shock 134 . A third pathological signaling mechanism is the trans -pathway (distinct from trans -signaling), which is mediated by attachment of IL-6 on T-helper 17 cells, which leads to pathological consequences such as ARDS 132 .

The ’bad’ actors of immune dysregulation are increased in obesity, DM and HTN and may account for the severity of disease. For instance, IL-6 levels are significantly higher in type 1 and 2 DM and directly proportional to BMI in obese persons 115 120 135 . IL-6 has a bidirectional relationship with DM as it is implicated in causing insulin resistance and disorders of glucose homeostasis 136 . T-cells in type 1 DM are more sensitive to IL-6 possibly leading to immune dysregulation and CRS 137 . In HTN, IL-6 levels are higher, likely mediated by the increased levels of angiotensin II and aldosterone, which directly trigger IL-6 secretion by the vasculature 138 . This effect is blocked by ARBs and mineralocorticoid receptor antagonists 139 . Elevated CRP, another predictor of COVID-19 severity, is a downstream effect of IL-6, and elevated in obesity, DM and HTN 140 . DPP-4, a known co-receptor of beta-coronaviruses is higher in persons with obesity and DM, and has independent pro-inflammatory effects 20 . Finally, the possibility of the pathological trans -pathway signaling of IL-6 in obesity, DM and HTN cannot be excluded given the pre-existing immune-dysregulatory state, and may contribute to CRS and clinical consequences such as ARDS. Taken together, the ’bad actors’ of immune dysregulation linked with severe COVID-19 are highly prevalent in obesity, DM and HTN, and may account for the higher severity noted in these states. Fig. 3 describes the immune-pharmacology of endocrine conditions and COVID-19.

Other endocrinopathies

Hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis

Glucocorticoids have both immune-stimulatory and -inhibitory effects 141 . During the initial phase of viral infection, glucocorticoids prime the immune response to counteract foreign antigens. However, in the advanced phase of viral infection, blunting of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis activation may occur that may lead to glucocorticoid insufficiency in the critical illness setting 141 . Given the widespread use of glucocorticoids and the possible risk to patients with adrenal insufficiency (AI), the Society for Endocrinology released an advisory statement conveying the lack of evidence to support a higher risk for contracting COVID-19 in patients with AI ( Table 2 ). They also reinforced sick-day glucocorticoid dosing and physical distancing rules as these patients may theoretically be at a higher risk for COVID-19 complications and mortality due to adrenal crisis, although this has yet to be described 142 . A recent opinion piece also highlighted the increased risks faced by patients taking physiological and supraphysiological doses of glucorticoids and encouraged identification of these patients and counseling about possible risks and precautions 143 . Patients with AI are at an elevated risk of infection, and patients with primary AI have been shown to have significantly decreased natural killer cell cytotoxicity that may compromise early recognition and elimination of virally infected cells and impair anti-viral immune defenses, although COVID-19 specific infection risk has not been reported to date 144 . Recently, COVID-19 specific guidance for the management of AI was published that advised specific sick-day rules in addition to reinforcing the importance of education and physical distancing 145 . This guidance recommended that adults with AI on physiological glucocorticoids and acute suspected or confirmed COVID-19 should double their morning hydrocortisone dose and then take 20mg hydrocortisone every 6 hours in order to provide evenly spaced glucocorticoid coverage for the persistent acute inflammation and often continuous fever experienced by patients with COVID-19. Those taking prendisonole 5–15 mg daily should take 10mg every twelve hours while those on doses of prednisolone>15 mg should continue to take their usual daily prednisolone dose but should split this into a morning and afternoon dose of at least 10mg each. Once the patient shows resolution of fever and significant clinical improvement, the hydrocortisone dose can be tapered to double the physiologic replacement dose and then normal routine doses when fully recovered. If the clinical symptoms and signs of COVID-19 worsen, it is recommend that patients contact emergency medical services and administer a subcutaneous or intramuscular injection of hydrocortisone 100 mg (or take 50–100 mg hydrocortisone orally if this injection is not available) 145 . Those with AI who contract COVID-19 and require mechanical ventilation or are severely ill, should be dosed according to acute stress dosing guidelines ( Table 2 ) 145 . Additionally, the use of venous thromboembolism prophylaxis with heparin in patients receiving glucocorticoids is recommended, given the increased risk of thrombotic events in COVID-19 141 . Furthermore, an increased risk to those with posterior pituitary deficits and electrolyte abnormalities has been logically speculated and the need to stock reasonable supplies emphasized 143 .

In another piece, addressing the management of Cushing syndrome during the COVID-19 pandemic, deferring biochemical workup for mild Cushing syndrome, appropriate management of comorbidities, risk-benefit assessment of definitive treatment (pharmacotherapy and surgery), and Pneumocystis jirovec i prophylaxis were emphasized 146 . According to the authors, for those on maintenance pharmacotherapy, dose titration according to clinical features or on the basis of the most recent biochemical values is reasonable 146 . Authors also advised postponement of imaging and localization studies for suspected (mild) cases. Further, they recommended urgent treatment only in sight- or life-threatening situations and reinforcement of sick-day rules, highlighting the need to re-evaluate the care of these patients once the current pandemic abates or is under control in the local geographical region 146 .

Hypothalamic-pituitary-thyroid axis

It is known that ACE2 receptors are expressed in thyroid tissue and play a critical role in physiological processes 147 . An overexpression of ACE2 has also been implicated in thyroid cancer progression 147 . In hyperthyroid animals, cardiac angiotensin 1–7 activity was augmented, suggesting a renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system regulating effect of thyroid hormones 148 . In observational studies, thyroid abnormalities, including sick euthyroid syndrome and thyroiditis, were reported in 3.6% of patients 108 and other endocrine disorders (excluding DM and HTN) were present in 13% of COVID-19 patients 34 . Direct damage to thyroid tissue from COVID-19 has also been reported at autopsy 149 . Thyroid disorders were also linked with a higher mortality risk in one report 150 . From a clinical practice standpoint, structural thyroid disease management warrants careful consideration. In particular, we agree with one opinion piece that suggested prioritization of suspected anaplastic and aggressive medullary thyroid cancer (serum calcitonin≥10 pg/ml) while deferring the care of less aggressive differentiated thyroid cancer 151 .

Diabetes insipidus

Central and nephrogenic diabetes insipidus (DI) pose a particular challenge due to reduced availability of laboratory (electrolyte) testing. An opinion piece recently highlighted this challenge, encouraging the practice of once a week aquaresis by omitting one dose of vasopressin in individuals with existing DI 152 . This would primarily prevent retention of excess free water and consequently maintain eunatremia. Further, they emphasized that the major risk in these patients is that of hyponatremia, which could be mitigated by daily bodyweight measurements, early self-recognition of clinical features of hyponatremia and counseling patients about drinking to thirst. In the inpatient setting, patients are vulnerable to hyponatremia both due to overtreatment of DI, and excess vasopressin from COVID-19 pneumonia in the context of syndrome of inappropriate antidiuretic hormone secretion 153 . For that reason, 0.9% saline should be used for volume resuscitation, and in the critical illness setting where frequent shifts in volume distribution occurs. Moreover, frequent clinical and biochemical assessment of sodium status should occur, while hypotonic fluids should be employed in hypernatremic patients 152 . Special caution should be exercised in the care of adipsic DI patients and endocrinology consultants should be involved early in their inpatient care 152 .

Bone and mineral metabolism

While there is no evidence of increased risk of COVID-19 to patients with bone-mineral metabolism disorders, the unprecedented global lockdowns have significantly affected their care. Given that most infusion centers, outpatient laboratories and bone scanning centers are temporarily closed, the National Osteoporosis Foundation released a guidance statement ( Table 2 ) 154 . It is advisable for those on medications such as Denosumab and Romosozumab to receive timely infusions, however, infusions of bisphosphonates such as Zolendronic acid may be deferred due to their long half-life 154 .

Hyperlipidemia

Hyperlipidemia was present in 5% of patients according to a review of 190 patients hospitalized with COVID-19 31 . The development of metabolic/lipid abnormalities in patients who recover from COVID-19 may also be anticipated based on data from the SARS cohort population 47 . Endocrinologists may be healthcare providers for this group in the future and should be wary of the possible long-term metabolic complications that may exist following COVID-19 infection.

Racial differences in COVID-19 outcomes

Several reports of higher mortality among Black and Hispanic people have emerged 155 156 . The CDC recently reported that 33% of COVID-19 inpatients in the US were Black despite only constituting 13% of the US population 6 . The state of Louisiana reported that Black and Asian patients constituted 59% and 0.83% of COVID-19 non-survivors 157 . New York City also reported a disproportionate mortality among Hispanics and Blacks 158 . While ACE2 expression is higher in Asian populations compared to Whites or Blacks, our current knowledge of these differences does not justify the disproportionate mortality 159 160 . This scourge is likely multifactorial: 1. Higher genetic predisposition to endocrine disorders, such as an increased prevalence of HTN in Black and obesity among Latin/Hispanic patients and 2. Racial disparity in access to healthcare and hospitals that may delay timely care, coupled with suboptimally controlled underlying chronic disease. The CDC surveillance data of the COVID-19–associated hospitalization rate among patients for the 4-week period ending March 28, 2020, was 4.6 per 100 000 population, with the following race/ethnicity data: 261 (45.0%) were non-Hispanic white (White), 192 (33.1%) were non-Hispanic Black (Black), 47 (8.1%) were Hispanic, 32 (5.5%) were Asian, two (0.3%) were American Indian/Alaskan Native, and 46 (7.9%) were of other or unknown race 6 . These social barriers for racial minorities amplify their vulnerability to endocrine disease in general and to COVID-19 as a consequence.

Sex differences in COVID-19 outcomes

In the US, over half of COVID-19 related hospitalizations occurred among men (5.1 vs. 4.1 per 100 000 population). Sex differences for general infections are likely multifactorial, including robustness of the immune responses (both innate and adaptive), sex-dependent production of steroid hormones (including testosterone and estrogens), immune response-related X-linked genes, and presence of disease susceptibility genes. The estrogen receptor signaling pathway has been identified as critical for protection in females infected with coronaviruses 151 . A plausible explanation for higher COVID-19 affection of men may be related to the downstream steps after ACE2 binding of SARS-CoV-2. As described previously, the SARS-CoV-2 viral capsid binds to surface ACE2 and subsequently engages a cellular serine protease TMPRSS2 for protein priming ( Fig. 2 ) 10 . From oncological studies, it is known that TMPRSS2 is an androgen responsive gene, which is highly expressed in men 161 . As suggested by one study, the higher TMPRSS2 expression in men could account for their higher vulnerability to COVID-19 161 . Further studies are required to ascertain the sex differences in COVID-19 related outcomes.

Care of transgender persons

Human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection and cancer are more frequent in transgender persons when compared to the general population 162 163 . These conditions coupled with pre-existing endocrinopathies can compromise the immune function, presumably leading to a higher COVID-19 risk in transgender persons. However, there is currently no published evidence to support this 162 . Transgender persons also frequently face social challenges such as poverty, homelessness and inadequate access to healthcare, which diminishes their ability to observe COVID-19 precautions and seek timely care 164 . It is therefore advisable that clinicians re-inforce and individualize guidance to this population while ensuring sufficient prescription refills. A plan of action is available at https://transequality.org/covid19/plan ( Table 2 ) 164 . For elective procedures such as gender confirmation surgery, postponement is appropriate in line with the CDC and WHO guidelines 48 49 .

General COVID-19 precautions for patients with endocrine conditions

All patients should maintain updated contact information for their healthcare

Adequate availability of prescription refills should be ensured

Emergency precautions and sick-day rules should be addressed on all routine clinic visits

Providers should remain up to date with evolving COVID-19 data and perform a careful critical appraisal of the available and increasing literature to be able to identify high-quality evidence to facilitate informed decisions to individualize care

Elective endocrine clinic visits should be deferred and alternative communication means such as telehealth visits consistent with social distancing should be encouraged

Mailing of prescriptions rather than inperson pickup should be adopted wherever feasible

Patients should be advised to stay updated with recommended vaccinations

Smoking (including hookah/waterpipe) cessation should be advised 165

Panic buying and stockpiling of medical supplies should be strongly discouraged

Patients should be informed of COVID-19 resources (CDC, WHO websites etc.) to obtain accurate information and follow best practices with respect to COVID-19 ( Table 2 )

Conclusion

In conclusion, endocrinologists routinely care for a high proportion of COVID-19 vulnerable patients who are at increased risk for life-threatening complications. Clinicians should counsel patients on emergency preparedness, contingency plans, maintaining adequate but not excessive supplies, social distancing and accessing reliable information resources. Further, care should only be based on available evidence and caution should be exercised against basing decisions on incomplete or inconclusive evidence. These measures may mitigate some of the risks faced by our vulnerable patient population in this unprecedented crisis.

Authors’ Disclaimer

To the best knowledge of the authors, the studies included in this article report data from distinct patient populations consistent with ethical scientific publication, a matter of concern in recent times 166 . Additionally, due to the ongoing COVID-19 crisis this document is not based on extensive systematic review or meta-analysis, but on expert consensus. The document should be considered as guidance only; it is not intended to determine an absolute standard of medical care. The doctors concerned must make the management plan for an individual patient

Funding Statement

Funding Information This work was funded by the intramural research program of the National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest. Dr. Stratakis laboratory holds patents on the function of the PRKAR1A, PDE11A, and GPR101 molecules and has received research funding from Pfizer Inc. for work related to GPR101 and acromegaly/gigantism.

References

- 1.WHO Director-General’s opening remarks at the media briefing on COVID-19; 11 March 2020 (press release); 2020

- 2.Coronavirus disease (COVID-2019) situation reports (press release). Online, March 16, 2020

- 3.Zhou F, Yu T, Du R et al. Clinical course and risk factors for mortality of adult inpatients with COVID-19 in Wuhan, China: A retrospective cohort study. Lancet. 2020;395:1054–1062. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30566-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Health LDo. Louisiana Department of Health Updates for 3/27/2020 Online: ldh.la.gov; 2020 cited Louisiana Department of Health. Available fromhttp://ldh.la.gov/index.cfm/newsroom/detail/5517

- 5.Center ICNAaR. Report on 775 patients critically ill with COVID-19 2020; updated March 27, 2020. Available fromhttps://www.icnarc.org/About/Latest-News/2020/03/27/Report-On-775-Patients-Critically-Ill-With-Covid-19

- 6.Garg S, Kim L, Whitaker M et al. Hospitalization Rates and Characteristics of Patients Hospitalized with Laboratory-Confirmed Coronavirus Disease 2019 – COVID-NET, 14 States, March 1–30, 2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2020;69:458–464. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6915e3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.WHO. Q & A on coronaviruses (COVID-19) (Guidance). 2020; updated March 9, 2020. Available fromhttps://www.who.int/news-room/q-a-detail/q-a-coronaviruses

- 8.Prevention CfDCa. People who are at higher risk for severe illness. Online; 2020 March 26, 2020

- 9.Wan Y, Shang J, Graham R et al. Receptor recognition by the novel coronavirus from Wuhan: An analysis based on decade-long structural studies of SARS coronavirus. J Virol. 2020;94:e00127–20. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00127-20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hoffmann M, Kleine-Weber H, Schroeder S et al. SARS-CoV-2 cell entry depends on ACE2 and TMPRSS2 and is blocked by a clinically proven protease inhibitor. Cell. 2020;181:e8. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2020.02.052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Muniyappa R, Gubbi S. COVID-19 pandemic, corona viruses, and diabetes mellitus. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2020;318:E736–E741. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00124.2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Roca-Ho H, Riera M, Palau V et al. Characterization of ACE and ACE2 expression within different organs of the NOD mouse. Int J Mol Sci. 2017;18:563. doi: 10.3390/ijms18030563. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Salem ES B, Grobe N, Elased K M. Insulin treatment attenuates renal ADAM17 and ACE2 shedding in diabetic Akita mice. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2014;306:F629–F639. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00516.2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yang J K, Lin S S, Ji X J et al. Binding of SARS coronavirus to its receptor damages islets and causes acute diabetes. Acta Diabetol. 2010;47:193–199. doi: 10.1007/s00592-009-0109-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zhang W, Xu Y-Z, Liu B Pioglitazone upregulates angiotensin converting enzyme 2 expression in insulin-sensitive tissues in rats with high-fat diet-induced nonalcoholic steatohepatitis. Sci World J. 2014. p. 603409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 16.Calvet H M, Yoshikawa T T. Infections in Diabetes. Infect Dis Clin North Am. 2001;15:407–421. doi: 10.1016/s0891-5520(05)70153-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Geerlings S E, Hoepelman AI M. Immune dysfunction in patients with diabetes mellitus [DM] FEMS Immunol Med Microbiol. 1999;26:259–265. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-695X.1999.tb01397.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Daryabor G, Kabelitz D, Kalantar K. An update on immune dysregulation in obesity-related insulin resistance. Scand J Immunol. 2019;89:e12747. doi: 10.1111/sji.12747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Varin E M, Mulvihill E E, Beaudry J L et al. Circulating levels of soluble dipeptidyl peptidase-4 are dissociated from inflammation and induced by enzymatic DPP4 inhibition. Cell Metab. 2019;29:e5. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2018.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Anoop S, Misra A, Bhatt S P et al. High circulating plasma dipeptidyl peptidase- 4 levels in non-obese Asian Indians with type 2 diabetes correlate with fasting insulin and LDL-C levels, triceps skinfolds, total intra-abdominal adipose tissue volume and presence of diabetes: A case–control study. BMJ Open Diabetes Res Care. 2017;5:e000393. doi: 10.1136/bmjdrc-2017-000393. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Stengel A, Goebel-Stengel M, Teuffel P et al. Obese patients have higher circulating protein levels of dipeptidyl peptidase IV. Peptides. 2014;61:75–82. doi: 10.1016/j.peptides.2014.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ryskjaer J, Deacon C F, Carr R D et al. Plasma dipeptidyl peptidase-IV activity in patients with type-2 diabetes mellitus correlates positively with HbAlc levels, but is not acutely affected by food intake. Eur J Endocrinol. 2006;155:485–493. doi: 10.1530/eje.1.02221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kleine-Weber H, Schroeder S, Krüger N et al. Polymorphisms in dipeptidyl peptidase 4 reduce host cell entry of Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus. Emerg Microbes Infect. 2020;9:155–168. doi: 10.1080/22221751.2020.1713705. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Raj V S, Mou H, Smits S L et al. Dipeptidyl peptidase 4 is a functional receptor for the emerging human coronavirus-EMC. Nature. 2013;495:251–254. doi: 10.1038/nature12005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Iacobellis G. COVID-19 and diabetes: Can DPP4 inhibition play a role? Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2020;162:108125. doi: 10.1016/j.diabres.2020.108125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Makdissi A, Ghanim H, Vora M et al. Sitagliptin exerts an antinflammatory action. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2012;97:3333–3341. doi: 10.1210/jc.2012-1544. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zhuge F, Ni Y, Nagashimada M et al. DPP-4 inhibition by linagliptin attenuates obesity-related inflammation and insulin resistance by regulating M1/M2 macrophage polarization. Diabetes. 2016;65:2966–2979. doi: 10.2337/db16-0317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mehta P, McAuley D F, Brown M et al. COVID-19: Consider cytokine storm syndromes and immunosuppression. Lancet. 2020;395:1033–1034. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30628-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Yang X, Yu Y, Xu J et al. Clinical course and outcomes of critically ill patients with SARS-CoV-2 pneumonia in Wuhan, China: A single-centered, retrospective, observational study. Lancet. Respir Med. 2020 doi: 10.1016/S2213-600(20)30079-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Huang C, Wang Y, Li X et al. Clinical features of patients infected with 2019 novel coronavirus in Wuhan, China. Lancet. 2020;395:497–506. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30183-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zhang J J, Dong X, Cao Y Y Clinical characteristics of 140 patients infected with SARS-CoV-2 in Wuhan, China Allergy. 2020. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 32.Wang D, Hu B, Hu C et al. Clinical characteristics of 138 hospitalized patients with 2019 novel coronavirus-infected pneumonia in Wuhan, China. JAMA. 2020;323:1061–1069. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.1585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Xu X W, Wu X X, Jiang X G et al. Clinical findings in a group of patients infected with the 2019 novel coronavirus [SARS-Cov-2] outside of Wuhan, China: Retrospective case series. BMJ. 2020;368:m606. doi: 10.1136/bmj.m606. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Chen N, Zhou M, Dong X et al. Epidemiological and clinical characteristics of 99 cases of 2019 novel coronavirus pneumonia in Wuhan, China: A descriptive study. Lancet. 2020;395:507–513. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30211-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lu R, Zhao X, Li J et al. Genomic characterisation and epidemiology of 2019 novel coronavirus: Implications for virus origins and receptor binding. Lancet. 2020;395:565–574. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30251-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Cao B, Wang Y, Wen D et al. A Trial of lopinavir-ritonavir in adults hospitalized with severe Covid-19. N Engl J Med. 2020 doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2001282. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Chen C, Chen C, Yan J T et al. Analysis of myocardial injury and cardiovascular disease in critically ill patients with new type of coronavirus pneumonia (J/OL) Chin J Cardiovasc Dis. 2020:48. doi: 10.3760/cma.j.cn112148-20200225-00123. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Arentz M, Yim E, Klaff L et al. Characteristics and outcomes of 21 critically ill patients with COVID-19 in Washington State. JAMA. 2020;323:1612–1614. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.4326. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Shi Y, Yu X, Zhao H et al. Host susceptibility to severe COVID-19 and establishment of a host risk score: Findings of 487 cases outside Wuhan. Critical Care. 2020;24:108. doi: 10.1186/s13054-020-2833-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.

- 41.Chan JF-W, Yuan S, Kok K-H et al. A familial cluster of pneumonia associated with the 2019 novel coronavirus indicating person-to-person transmission: a study of a family cluster. Lancet. 2020;395:514–523. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30154-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Goyal P, Choi J J, Pinheiro L C et al. Clinical characteristics of Covid-19 in New York City. N Eng J Med. 2020 doi: 10.1056/NEJMc2010419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Richardson S, Hirsch J S, Narasimhan M et al. Presenting Characteristics, Comorbidities, and Outcomes Among 5700 Patients Hospitalized With COVID-19 in the New York City Area. JAMA. 2020 doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.6775. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Novel Coronavirus Pneumonia Emergeny rResponse Epidemiology Team.The epidemiological characteristics of an outbreak of 2019 novel coronavirus diseases (COVID-19) in China Chin J Epidemiol 202041145–151. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Guo W, Li M, Dong Y et al. Diabetes is a risk factor for the progression and prognosis of COVID-19. Diabetes Metab Res Rev. 2020:e3319. doi: 10.1002/dmrr.3319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.https://glytecsystems.com/wp-content/uploads/Sage.Glycemic-Characteristics-and-Clinical-Outcomes-of-Covid-19-Patients.FINAL_.pdf https://glytecsystems.com/wp-content/uploads/Sage.Glycemic-Characteristics-and-Clinical-Outcomes-of-Covid-19-Patients.FINAL_.pdf

- 47.Wu Q, Zhou L, Sun X et al. Altered lipid metabolism in recovered SARS patients twelve years after infection. Sci Rep. 2017;7:9110. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-09536-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Prevention CfDCa. Interim Clinical Guidance for Management of Patients with Confirmed Coronavirus Disease (COVID-19) (ONLINE). Online 2020 (March 15, 2020). Guidelines for COVID-19 management. Available fromhttps://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/hcp/clinical-guidance-management-patients.html

- 49.WHO Clinical management of severe acute respiratory infection when novel coronavirus (nCoV) infection is suspected 2020 (cited 2020 March 15). Guidelines. Available athttps://www.who.int/docs/default-source/coronaviruse/clinical-management-of-novel-cov.pdf

- 50.Bornstein S R, Dalan R, Hopkins D et al. Endocrine and metabolic link to coronavirus infection. Nat Rev Endocrinol. 2020 doi: 10.1038/s41574-020-0353-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Marshall A C, Shaltout H A, Nautiyal M et al. Fetal betamethasone exposure attenuates angiotensin-[1-7]-Mas receptor expression in the dorsal medulla of adult sheep. Peptides. 2013;44:25–31. doi: 10.1016/j.peptides.2013.03.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Zhou Y H, Qin Y Y, Lu Y Q et al. Effectiveness of glucocorticoid therapy in patients with severe novel coronavirus pneumonia: Protocol of a randomized controlled trial. Chin Med J (Engl) 2020;133:1080–1086. doi: 10.1097/CM9.0000000000000791. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Association AD COVID-19 from the American Diabetes Association (Online). ADA; 2020 March 2020:Webpage9. Available fromhttps://www.diabetes.org/diabetes/treatment-care/planning-sick-days/coronavirus

- 54.AACE Position Statement: Coronavirus [COVID-19] and People with Diabetes (Updated March 18, 2020) (press release). Online: aace.com, March 18, 2020

- 55.American College of Endocrinology L, Novo Nordisk, Medtronic. My Diabetes Emergency Plan. Online: mydiabetesememergencyplan.com; 2016

- 56.Katulanda P, Dissanayake H, Ranathunga I et al. Prevention and management of COVID-19 among patients with diabetes: An appraisal of the literature. Diabetologia. 2020 doi: 10.1007/s00125-20-05164-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Prevention CfDCa. Vaccine information for adults: Diabetes type 1 and 22016 March 18, 2020 (cited 2020 March 18). Available fromhttps://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/adults/rec-vac/health-conditions/diabetes.html

- 58.Smith S A, Poland G A.Influenza and pneumococcal immunization in diabetes Diabetes Care 200427(Suppl 1):S111–S113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Shah N. Higher co-infection rates in COVID19. Coronavirus (Internet). 2020 (cited 2020 March 18). Available fromhttps://medium.com/@nigam/higher-co-infection-rates-in-covid19-b24965088333

- 60.Mueller L.Buying Insulin in Canada Without a Prescription (BTC) (Electronic)Online2017 (updated September 1, 2017; cited 2020 March 18). Drug Commentary. Available fromhttps://www.pharmacycheckerblog.com/buying-insulin-canada-without-prescription

- 61.Tribble SJ You Can Buy Insulin Without A Prescription, But Should You? (Electronic). Online2015 (updated December 14, 2015; cited 2020 March 18). Health Guide. Available fromhttps://www.npr.org/sections/health-shots/2015/12/14/459047328/you-can-buy-insulin-without-a-prescription-but-should-you

- 62.PG Buying Insulin (India) (Internet). P G, editor. Online2007 October 11, 2007. (cited 2020 March 18, 2020). Available fromhttps://www.indiamike.com/india/health-and-well-being-in-india-f2/buying-insulin-t44927/#post392426

- 63.Fletcher F. Has anyone traveled to Mexico to buy their supplies? March 18. 2020 Ed OnlineForum.tudiabetes.org; 2017

- 64.Association AD 13 Diabetes Care in the Hospital. Diabetes Care 2016; 39 (Suppl 1): S99 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 65.Cansu DÜ, Korkmaz C. Hypoglycaemia induced by hydroxychloroquine in a non-diabetic patient treated for RA. Rheumatology. 2008;47:378–379. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/kem378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Goyal V, Bordia A. The hypoglycemic effect of chloroquine. J Assoc Physicians India. 1995;43:17–18. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Lee G A, Seneviratne T, Noor M A et al. The metabolic effects of lopinavir/ritonavir in HIV-negative men. AIDS (London, England) 2004;18:641–649. doi: 10.1097/00002030-200403050-00008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Hansen T K, Thiel S, Wouters P J et al. Intensive insulin therapy exerts antiinflammatory effects in critically ill patients and counteracts the adverse effect of low mannose-binding lectin levels. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2003;88:1082–1088. doi: 10.1210/jc.2002-021478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Viby N E, Isidor M S, Buggeskov K B et al. Glucagon-like peptide-1 [GLP-1] reduces mortality and improves lung function in a model of experimental obstructive lung disease in female mice. Endocrinology. 2013;154:4503–4511. doi: 10.1210/en.2013-1666. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Drucker D J.Coronavirus infections and type 2 diabetes-shared pathways with therapeutic implications Endocr Rev 202041pii: bnaa011 10.1210/endrev/bnaa011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Zhou F, Zhang Y, Chen J et al. Liraglutide attenuates lipopolysaccharide-induced acute lung injury in mice. Eur J Pharmacol. 2016;791:735–740. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2016.10.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.World B Retailers call for rationing of rubbing alcohol, hand sanitizer2020 March 18, 2020 (cited 2020 March 18). Available fromhttps://www.msn.com/en-ph/money/topstories/retailers-call-for-rationing-of-rubbing-alcohol-hand-sanitizer/ar-BB112KyJ?li=BBr8Mkm

- 73.Baker J. Extra insulin supplies, medications advised for people with diabetes in wake of COVID-19. Endocrine Today (Internet). 2020; (cited 2020 March 21). Available fromhttps://www.healio.com/endocrinology/diabetes/news/online/%7B19b3e970-b54c-499b-8cfa-01591e7bcd6b%7D/extra-insulin-supplies-medications-advised-for-people-with-diabetes-in-wake-of-covid-19

- 74.Administration UFaD Current and Resolved Drug Shortages and Discontinuations Reported to FDA 2020 (cited 2020 April 21). Available fromhttps://www.accessdata.fda.gov/scripts/drugshortages/

- 75.Society E COVID-10 Member Resources and Communications (Electronic). www.endocrine.org2020 (updated March 25, 2020; cited 2020 March 25). Available fromhttps://www.endocrine.org/membership/covid-19-member-resources-and-communications

- 76.Services CfMM President Trump Expands Telehealth Benefits for Medicare Beneficiaries During COVID-19 Outbreak. Online: CMS. 2020; March 17: 2020

- 77.Ministry of Solidarity and Health F COVID-19 and telehealth: who can practice remotely and how? Online 2020 (updated March 31, 2020). Available fromhttps://solidarites-sante.gouv.fr/soins-et-maladies/maladies/maladies-infectieuses/coronavirus/professionnels-de-sante/article/covid-19-et-telesante-qui-peut-pratiquer-a-distance-et-comment

- 78.Singh M V, Chapleau M W, Harwani S C et al. The immune system and hypertension. Immunol Res. 2014;59:243–253. doi: 10.1007/s12026-014-8548-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Amador C A, Barrientos V, Pena J et al. Spironolactone decreases DOCA-salt-induced organ damage by blocking the activation of T helper 17 and the downregulation of regulatory T lymphocytes. Hypertension. 2014;63:797–803. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.113.02883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Kvakan H, Luft F C, Muller D N. Role of the immune system in hypertensive target organ damage. Trends Cardiovasc Med. 2009;19:242–246. doi: 10.1016/j.tcm.2010.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Abboud F M, Harwani S C, Chapleau M W. Autonomic neural regulation of the immune system: implications for hypertension and cardiovascular disease. Hypertension. 2012;59:755–762. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.111.186833. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Guan W-j, Ni Z-y, Hu Y et al. Clinical Characteristics of Coronavirus Disease 2019 in China. N Eng J Med. 2020;382:1708–1720. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2002032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Chen C, Chen C, Jiangtao Y Analysis of myocardial injury and cardiovascular diseases in critical patients with new Coronavirus pneumonia. Chin J Cardiovasc Dis. 2020.

- 84.Guan W-j, Liang W-h, Zhao Y et al. Comorbidity and its impact on 1590 patients with Covid-19 in China: A nationwide analysis. Eur Respir J. 2020:2.000547E6. doi: 10.1183/13993003.00547-2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Kabakov E, Norymberg C, Osher E et al. Prevalence of hypertension in type 2 diabetes mellitus: impact of the tightening definition of high blood pressure and association with confounding risk factors. J Cardiometab Syndr. 2006;1:95–101. doi: 10.1111/j.1559-4564.2006.05513.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Turner A J, Hiscox J A, Hooper N M. ACE2: from vasopeptidase to SARS virus receptor. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 2004;25:291–294. doi: 10.1016/j.tips.2004.04.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Yan R, Zhang Y, Li Y et al. Structural basis for the recognition of SARS-CoV-2 by full-length human ACE2. Science. 2020;367:1444. doi: 10.1126/science.abb2762. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Ramchand J, Patel S K, Kearney L G et al. Plasma ACE2 activity predicts mortality in aortic stenosis and is associated with severe myocardial fibrosis. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging. 2020;13:655–664. doi: 10.1016/j.jcmg.2019.09.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Ferrario C M, Jessup J, Chappell M C et al. Effect of angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibition and angiotensin II receptor blockers on cardiac angiotensin-converting enzyme 2. Circulation. 2005;111:2605–2610. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.104.510461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Soler M J, Ye M, Wysocki J et al. Localization of ACE2 in the renal vasculature: amplification by angiotensin II type 1 receptor blockade using telmisartan. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2009;296:F398–F405. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.90488.2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Vuille-dit-Bille R N, Camargo S M, Emmenegger L et al. Human intestine luminal ACE2 and amino acid transporter expression increased by ACE-inhibitors. Amino Acids. 2015;47:693–705. doi: 10.1007/s00726-014-1889-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Burns K D, Lytvyn Y, Mahmud F H et al. The relationship between urinary renin-angiotensin system markers, renal function, and blood pressure in adolescents with type 1 diabetes. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2017;312:F335–F342. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00438.2016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Gutta S, Grobe N, Kumbaji M et al. Increased urinary angiotensin converting enzyme 2 and neprilysin in patients with type 2 diabetes. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2018;315:F263–F274. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00565.2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Zheng Y Y, Ma Y T, Zhang J Y et al. COVID-19 and the cardiovascular system. Nat Rev Cardiol. 2020;17:259–260. doi: 10.1038/s41569-020-0360-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Fang L, Karakiulakis G, Roth M.Are patients with hypertension and diabetes mellitus at increased risk for COVID-19 infection? Lancet Respir Med 20208e21.doi: 10.1016/S2213-2600(20)30116-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Diaz JH. Hypothesis: angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors and angiotensin receptor blockers may increase the risk of severe COVID-19. J Travel Med 2020; pii: taaa041 doi. 10.1093/jtm/taaa041 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 97.Imai Y, Kuba K, Rao S et al. Angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 protects from severe acute lung failure. Nature. 2005;436:112–116. doi: 10.1038/nature03712. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.South A M, Tomlinson L, Edmonston D et al. Controversies of renin–angiotensin system inhibition during the COVID-19 pandemic. Nat Rev Nephrol. 2020 doi: 10.1038/s41581-020-0279-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Peiró C, Moncada S. Substituting Angiotensin-[1-7] to Prevent Lung Damage in SARSCoV2 Infection? Circulation 2020; doi: 10.1161/ CIRCULATIONAHA.120047297 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 100.Kickbusch I, Leung G. Response to the emerging novel coronavirus outbreak. BMJ. 2020;368:m406. doi: 10.1136/bmj.m406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Dalan R, Bornstein S R, El-Armouche A et al. The ACE-2 in COVID-19: Foe or Friend? Horm Metab Res. 2020 doi: 10.1055/a-1155-0501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Schiffrin E L, Flack J M, Ito S et al. Hypertension and COVID-19. Am J Hypertens. 2020;33:373–374. doi: 10.1093/ajh/hpaa057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Danser AH J, Epstein M, Batlle D. Renin-Angiotensin System Blockers and the COVID-19 Pandemic. Hypertension. 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 104.Sparks M A, South A, Welling P et al. Sound Science before Quick Judgement Regarding RAS Blockade in COVID-19. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2020 doi: 10.2215/CJN.03530320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Vaduganathan M, Vardeny O, Michel T et al. Renin–Angiotensin-Aldosterone System Inhibitors in Patients with Covid-19. N Eng J Med. 2020;382:1653–1659. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsr2005760. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Meng J, Xiao G, Zhang J et al. Renin-angiotensin system inhibitors improve the clinical outcomes of COVID-19 patients with hypertension. Emerg Microb Infect. 2020;9:757–760. doi: 10.1080/22221751.2020.1746200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Zhang P, Zhu L, Cai J et al. Association of inpatient use of angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitors and angiotensin ii receptor blockers with mortality among patients with hypertension hospitalized with COVID-19. Circ Res. 2020 doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.120.317134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Cardiology ESf. Position Statement of the ESC Council on Hypertension on ACE-Inhibitors and Angiotensin Receptor Blockers (Online). 2020 (updated March 13, 2020; cited 2020 March 15). Available fromhttps://www.escardio.org/Councils/Council-on-Hypertension-(CHT)/News/position-statement-of-the-esc-council-on-hypertension-on-ace-inhibitors-and-ang

- 109.Canada H Hypertension Canada’s Statement on: Hypertension, ACE-Inhibitors and Angiotensin Receptor Blockers and COVID-19 (Online). Online 2020 (cited 2020 March 17). Position statement]. Available fromhttps://hypertension.ca/wp-content/uploads/2020/03/2020-30-15-Hypertension-Canada-Statement-on-COVID-19-ACEi-ARB.pdf

- 110.Hypertension ISo A statement from the International Society of Hypertension on COVID-19 (Online). Online 2020 (updated March 16, 2020; cited 2020 March 17). Position Statement]. Available from: A statement from the International Society of Hypertension on COVID-19

- 111.Hypertension ESo. Statement of the European Society of Hypertension (ESH) on hypertension, Renin Angiotensin System blockers and COVID-19 Online2020 (updated March 12, 2020; cited 2020 March 17). Position Statement. Available fromhttps://www.eshonline.org/spotlights/esh-statement-on-covid-19/

- 112.Cardiology AHAHFSoAACo. Patients taking ACE-i and ARBs who contract COVID-19 should continue treatment, unless otherwise advised by their physician (Web). Online; 2020 (updated March 17, 2020; cited 2020 March 17). 1: (Position Statement). Available fromhttps://newsroom.heart.org/news/patients-taking-ace-i-and-arbs-who-contract-covid-19-should-continue-treatment-unless-otherwise-advised-by-their-physician

- 113.Li YP. Recombinant human angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (rhACE2) as a Treatment for patients with COVID-19 (Online). Online: clinicaltrials.gov. 2020;(updated February 27, 2020; cited 2020 March 15). Clinical trial registration. Available fromhttps://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT04287686

- 114.Aronson J K, Ferner R E. Drugs and the renin-angiotensin system in covid-19. BMJ. 2020;369:m1313. doi: 10.1136/bmj.m1313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Ellulu M S, Patimah I, Khaza’ai H et al. Obesity and inflammation: the linking mechanism and the complications. Arch Med Sci. 2017;13:851–863. doi: 10.5114/aoms.2016.58928. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Rodriguez-Hernandez H, Simental-Mendí L E, Rodgriguez-Ramirez G et al. Obesity and Inflammation: Epidemiology, Risk Factors, and Markers of Inflammation. Int J Endocrinol. 2013:678159. doi: 10.1155/2013/678159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Ryan P M, Caplice N M. Is Adipose tissue a reservoir for viral spread, immune activation and cytokine amplification in COVID-19. Obesity. 2020 doi: 10.1002/oby.22843. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Maier H E, Lopez R, Sanchez N et al. Obesity increases the duration of influenza a virus shedding in adults. J Infect Dis. 2018;218:1378–1382. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jiy370. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Mraz M, Haluzik M. The role of adipose tissue immune cells in obesity and low-grade inflammation. J Endocrinol. 2014;222:R113–R127. doi: 10.1530/JOE-14-0283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Choi J, Joseph L, Pilote L. Obesity and C-reactive protein in various populations: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Obes Rev. 2013;14:232–244. doi: 10.1111/obr.12003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Wang L. C-reactive protein levels in the early stage of COVID-19. Med Mal Infect. 2020; pii: S0399-077X(20)30086-X; doi: 10.1016/j. medmal.2020.03.007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 122.

- 123.Trim W, Turner J E, Thompson D. Parallels in immunometabolic adipose tissue dysfunction with ageing and obesity. Front Immunol. 2018;9:169. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2018.00169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Patel V B, Mori J, McLean B A et al. ACE2 deficiency worsens epicardial adipose tissue inflammation and cardiac dysfunction in response to diet-induced obesity. Diabetes. 2016;65:85–95. doi: 10.2337/db15-0399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Bloodworth M H, Rusznak M, Pfister C C et al. Glucagon-like peptide 1 receptor signaling attenuates respiratory syncytial virus-induced type 2 responses and immunopathology. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2018;142:e12. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2018.01.053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Abdollahi M, Cushman M, Rosendaal F R. Obesity: Risk of venous thrombosis and the interaction with coagulation factor levels and oral contraceptive use. Thromb Haemost. 2003;89:493–498. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.Stein P D, Beemath A, Olson R E. Obesity as a risk factor in venous thromboembolism. Am J Med. 2005;118:978–980. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2005.03.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128.Tang N, Bai H, Chen X et al. Anticoagulant treatment is associated with decreased mortality in severe coronavirus disease 2019 patients with coagulopathy. J Thromb Haemost. 2020;18:1094–1099. doi: 10.1111/jth.14817. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129.Stefan N, Birkenfeld A L, Schulze M B et al. Obesity and impaired metabolic health in patients with COVID-19. Nat Rev Endocrinol. 2020 doi: 10.1038/s41574-020-0364-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130.Sattar N, McInnes I B, McMurray JJ V. Obesity a risk factor for severe COVID-19 infection: Multiple potential mechanisms. Circulation. 2020 doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.120.047659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 131.Lighter J, Phillips M, Hochman S et al. Obesity in patients younger than 60 years is a risk factor for Covid-19 hospital admission. Clin Infect Dis. 2020 doi: 10.1093/cid/ciaa415. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 132.Moore BJ B, June C H. Cytokine release syndrome in severe COVID-19. Science. 2020;368:473–474. doi: 10.1126/science.abb8925. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 133.Kang S, Tanaka T, Narazaki M et al. Targeting interleukin-6 signaling in clinic. Immunity. 2019;50:1007–1023. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2019.03.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 134.Rockx B, Kuiken T, Herfst S et al. Comparative pathogenesis of COVID-19, MERS, and SARS in a nonhuman primate model. Science. 2020 doi: 10.1126/science.abb7314. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 135.Pradhan A D, Manson J E, Rifai N et al. C-Reactive protein, interleukin 6, and risk of developing type 2 diabetes mellitus. JAMA. 2001;286:327–334. doi: 10.1001/jama.286.3.327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 136.Pickup J C, Mattock M B, Chusney G D et al. NIDDM as a disease of the innate immune system: association of acute-phase reactants and interleukin-6 with metabolic syndrome X. Diabetologia. 1997;40:1286. doi: 10.1007/s001250050822. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 137.Hundhausen C, Roth A, Whalen E et al. Enhanced T cell responses to IL-6 in type 1 diabetes are associated with early clinical disease and increased IL-6 receptor expression. Sci Transl Med. 2016;8:356ra119. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.aad9943. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 138.Chamarthi B, Williams G H, Ricchiuti V et al. Inflammation and hypertension: the interplay of interleukin-6, dietary sodium, and the renin-angiotensin system in humans. Am J Hypertens. 2011;24:1143–1148. doi: 10.1038/ajh.2011.113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 139.Luther J M, Gainer J V, Murphey L J et al. Angiotensin II induces interleukin-6 in humans through a mineralocorticoid receptor-dependent mechanism. Hypertension. 2006;48:1050–1057. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.0000248135.97380.76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 140.Smith G D, Lawlor D A, Harbord R et al. Association of C-reactive protein with blood pressure and hypertension. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2005;25:1051–1056. doi: 10.1161/01.ATV.0000160351.95181.d0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 141.Isidori A M, Pofi R, Hasenmajer V et al. Use of glucocorticoids in patients with adrenal insufficiency and COVID-19 infection. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2020 doi: 10.1016/S2213-8587(20)30149-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 142.Endocrinology Sf. (webpage). Online2020 (updated March 11, 2020; cited 2020 March 15). Advice Statement. Available fromhttps://www.endocrinology.org/news/item/14050/Coronavirus-advice-statement-for-patients-with-adrenal%2fpituitary-insufficiency

- 143.Kaiser U B, Mirmira R G, Stewart P M.Our Response to COVID-19 as Endocrinologists and Diabetologists J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2020105pii: dgaa148 10.1210/clinem/dgaa148 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]