Abstract

Titanium dioxide (TiO2) has a long history of application in blood contact materials, but it often suffers from insufficient anticoagulant properties. Recently, we have revealed the photocatalytic effect of TiO2 also induces anticoagulant properties. However, for long-term vascular implant devices such as vascular stents, besides anticoagulation, also anti-inflammatory, anti-hyperplastic properties, and the ability to support endothelial repair, are desired. To meet these requirements, here, we immobilized silver nanoparticles (AgNPs) on the surface of TiO2 nanotubes (TiO2-NTs) to obtain a composite material with enhanced photo-induced anticoagulant property and improvement of the other requested properties. The photo-functionalized TiO2-NTs showed protein-fouling resistance, causing the anticoagulant property and the ability to suppress cell adhesion. The immobilized AgNPs increased the photocatalytic activity of TiO2-NTs to enhances its photo-induced anticoagulant property. The AgNP density was optimized to endow the TiO2-NTs with anti-inflammatory property, a strong inhibitory effect on smooth muscle cells (SMCs), and low toxicity to endothelial cells (ECs). The in vivo test indicated that the photofunctionalized composite material achieved outstanding biocompatibility in vasculature via the synergy of photo-functionalized TiO2-NTs and the multifunctional AgNPs, and therefore has enormous potential in the field of cardiovascular implant devices. Our research could be a useful reference for further designing of multifunctional TiO2 materials with high vascular biocompatibility.

Keywords: Vascular biocompatibility, UV irradiation, TiO2, Sliver nanoparticles(AgNPs), Synergic effect

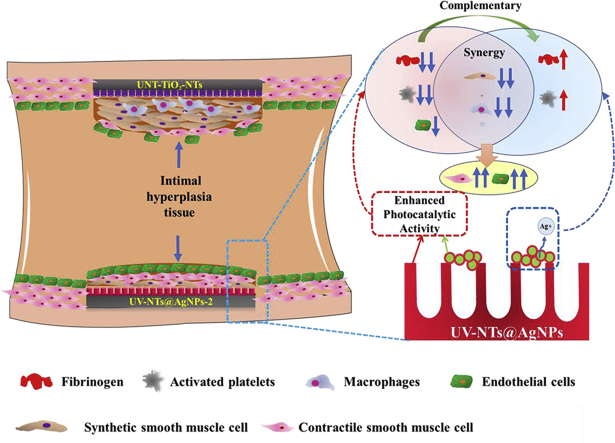

Graphical abstract

Highlights

-

•

Photo-functionalized TiO2NTs@Ag composites showed excellent vascular compatibility.

-

•

UV irradiation greatly improved the anticoagulant properties of the composites.

-

•

Moderately loaded AgNPs strongly inhibited SMCs and MAs, but weakly inhibited ECs.

1. Introduction

Based on the excellent chemical stability and biosafety [1], titanium dioxide (TiO2) is a popular medical ceramic with broad application for blood-contacting devices [2,3]. However, like most inorganic materials, TiO2 has a shortage of insufficient anticoagulant properties [4]. To overcome this shortage, people developed many surface modification techniques to improve the anticoagulant properties of TiO2. However, most of these modification methods are complicated to operate, require expensive biomolecules, and with unavoidable contamination of various reagents [[5], [6], [7]]. In a recent study, we have discovered a new approach to improve the anticoagulant properties of TiO2: ultraviolet (UV) irradiation [8]. Compared with the traditional surface modification method, UV irradiation treatment has the advantages of being simple, economical, and green. During UV irradiation, the photocatalytic reaction changs various chemical properties of the surface of TiO2, suppressing the fibrinogen fouling [9,10]. Therefore, the photo-functionalized TiO2 exhibited an excellent anticoagulant property and a promising application potential in blood contact materials.

However, long-term implanted blood contact devices, such as vascular stents, in addition to the problem of coagulation in vivo, also face challenges such as inflammation, smooth muscle cells (SMCs) hyperplasia and restenosis, and reduced endothelial repair [11]. Therefore, it is necessary to introduce additional multifunctional materials with anti-inflammatory and selectively inhibitory effects on SMCs to the surface of the photofunctionalized TiO2. Since organic molecules are not stable during the photocatalytic process [12,13], inorganic functional elements on the surface of TiO2 appear as a reasonable choice.

Silver nanoparticles (AgNPs) are inorganic functional materials, combining properties of anti-inflammation [14] and SMCs inhibition [15]. They are rarely used for surface modification of vascular stents, because they tend to induce coagulation [16]. However, in combination with TiO2, Ag nanoparticles can form a Schottky barrier with TiO2, thereby enhancing the photocatalytic activity of TiO2. Therefore, the introduction of an appropriate amount of AgNPs on TiO2 may enhance the photo-induced anticoagulant properties of TiO2. Endothelial cells (ECs) seem to have a stronger resistance to the toxicity of Ag ions than SMCs [17]. Therefore, immobilization of an appropriate amount of AgNPs on the surface of TiO2 may inhibit SMCs without excessive inhibition of the EC growth. Therefore, tuning of the amount of AgNPs immobilized on the surface of TiO2 becomes very important. It has been reported that TiO2 can generate and immobilize AgNPs from a AgNO3 solution on the surface by photoreduction. Moreover, adjusting the time of the photoreduction can easily alter the number of AgNPs [18,19].

Based on the above knowledge, in this paper, different amounts of AgNPs were fixed on the surface of TiO2 nanotubes by photoreduction to form the TiO2-NTs@Ag composite material. Then, through UV pretreatment, we obtained a photofunctionalized TiO2-NTs@Ag composite material. We characterized the surface morphology, surface physicochemical properties, and photocatalytic properties of the composite material. After that, we systematically evaluated the composite material by testing anticoagulant and anti-inflammatory properties, and the interaction with blood vessel cells. Finally, through implantation in rat abdominal aorta, we show that the photofunctionalized TiO2-NTs@Ag composite has excellent vascular biocompatibility in vivo. The synergistic and complementary effects of TiO2-NTs and AgNPs in vivo on the excellent vascular biocompatibility of the TiO2-NTs@Ag composite are discussed.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Preparation of TiO2-NTs decorated with AgNPs

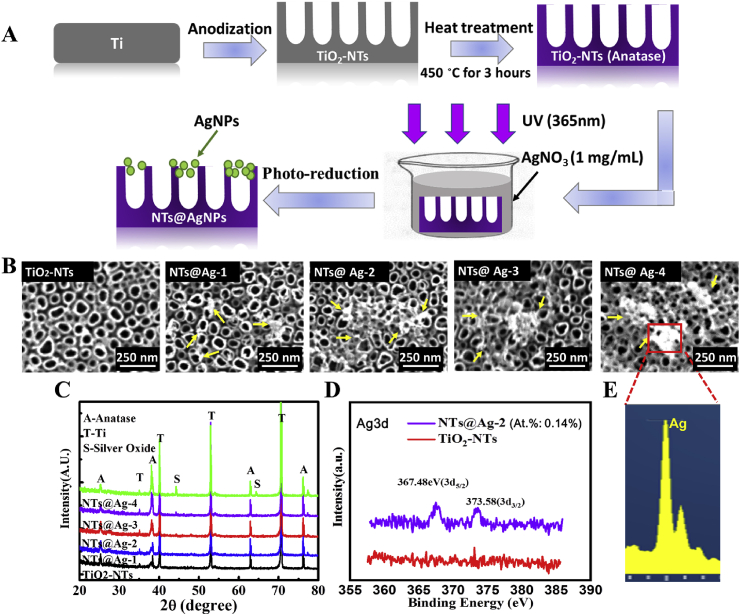

The process of preparation of TiO2-NTs decorated with AgNPs is illustrated in Fig. 1(A). Briefly, TiO2-NTs were prepared by an anodic oxidation. The electrolyte was a mixture of glycerol (C3H8O3, Chengdu Kelong Trial Chemical Factory) and water (4:1, v/v). The electrolyte contained 0.5 wt% NH4F and 0.35 wt% NaCl. A pure Ti foil (99.5%, 0.05 mm thickness) was placed in the electrolyte for 2 h of anodic oxidation at a constant current voltage of 21 V. Then, the samples were heat-treated at 450 °C for 3 h to obtain TiO2-NTs with anatase crystal structure [20]. Next, the TiO2-NTs were immersed in an aqueous silver nitrate (AgNO3) solution (c = 1 mg/mL) and subjected to photochemical reduction treatment (UV light intensity = 4 mW/cm2, wavelength λ = 365 nm) to fix AgNPs on TiO2-NTs [21]. Photo-reduction treatment times were 10, 30, 60, and 180 s to obtain the composite materials labeled as NTs-Ag1, NTs-Ag2, NTs-Ag3, respectively. All samples were stored in air for more than 4 weeks before UV irradiation treatment.

Fig. 1.

Preparation strategies and surface characterization of the materials. (A) Schematic illustration of the fabrication of TiO2-NTs and NTs@Ag. (B) surface topography detected by SEM. (C) XRD spectra. (C) High-resolution spectrum of XPS Ag3d peak of TiO2-NTs and NTs@Ag-2. (E) EDX spectrum of NTs@Ag-4.

2.2. UV irradiation pretreatment

The TiO2-NTs and NTs-Ag samples were pretreated by UV irradiation for 1 h in the air. A photolithography machine (URE-2000/25-T9, Chinese Academy of Science, China) with an intensity of 12 mW/cm2 was used as the source of UV light (λ = 365 nm). In this paper, the prefixes “UNT-" and “UV-" are used to denominate the samples without and with UV irradiation pretreatment, respectively. After the UV irradiation treatment, all samples were evaluated for surface chemistry and bioactivity within 24 h.

2.3. Materials surface characterization

The surface topography of TiO2-NTs and NT-Ag samples was determined by scanning electron microscopy (SEM Quanta 200, FEI, Holland). The structures of TiO2-NTs and NT-Ag samples were determined by X-ray diffraction (XRD; X'Pert Pro MPD, Philips, Holland) by using a copper target at a glancing angle of 0.5°. The surface compositions of the samples were characterized by energy dispersive spectroscopy (EDS, Quanta 200, FEI, Holland) and X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS; XSAM800, Kratos, Ltd., United Kingdom). For XPS analysis, the C1s peak at 284.5 eV was used as a reference for charge correction.

2.4. Functional characterization of materials

2.4.1. Photocatalytic activity

The samples were immersed in 1 mL of methylene blue (MB) aqueous solution (c = 5 mg/L) for UV irradiation for 1 h, 2 h, and 3 h. At each time point, 100 μL of MB solutions were taken from each sample to test the absorbance value at 664 nm by the microplate reader (UV-2550, Shimadzu Corporation). The relationship between the absorbance value (A) and the degradation rate (G) of MB was as follows:

| G = [(A0-At) / A0] × 100% | (1) |

where A0 was the initial absorbance value of MB solutions, and At was the absorbance value after t hours of degradation.

2.4.2. Hydrophilicity

Before and after UV irradiation, the hydrophilicity of samples was detected by a drop shape analysis system (DSA 100; Krüss, Germany) by the sessile drop method (5 μL droplet).

2.4.3. Oxydation of adsorbed hydrocarbons on the surface of the sample

The oxidation of the adsorbed hydrocarbons on the sample's surface was determined by the XPS detection of the energy shift of oxygen-containing hydrocarbons at about 288 eV.

2.5. Determination of anticoagulant properties

2.5.1. Platelet adhesion

The method of platelet adhesion test has been described elsewhere [22]. Briefly, the platelet-rich plasma (PRP) was obtained from the human xx anticoagulated blood of a volunteer who did not take any medication in the recent ten days. The blood was centrifuged at xx g for yy min at room temperature. The samples (7×7 mm2) were covered with 50 μL of RPR and incubated at 37 °C for 1 h. After incubation, the samples were washed by NaCl and immersed into glutaraldehyde aqueous solution (c = 2.5 wt%) for 6 h. Then the samples were stained by rhodamine and gradient chemical dried. Finally, the platelets on the samples were observed by the fluorescence microscope and SEM.

2.5.2. Fibrinogen adsorption

Briefly, the platelet-poor plasma (PPP) was obtained from human blood by xx min centrifugation at yy g. The samples were covered with 50 μL of PPP and incubated at 37 °C for 1 h. After incubation, the samples were washed by NaCl and immersed into an PBS solution of bovine serum albumin (BSA, c = 10 mg/mL) for 30 min. Then the samples were washed again with NaCl, covered with 20 μL of HRP (horseradish peroxidase)-labeled mouse anti-human fibrinogen monoclonal antibody (biosis, china), and incubated at 37 °C for 1 h. Then, the samples were thoroughly washed with PBS. After that, 20 μL of TMB solution (diluted 1:4 in PBS) was added onto the samples. After reacted for 10 min, 50 μL of 1 M H2SO4 was added to stop the reaction, and a microplate reader determined the absorbance values at 450 nm. The relative amount of adsorbed Fgn was quantified according to a calibration curve.

2.5.3. Hemolysis

The detailed steps of the hemolysis test have also been described in our previous study [8].

Ex-vivo evaluation of anticoagulant properties.

The Local Ethical Committee approved all of the animal experiments in this study. New Zealand White Rabbits with a weigh of 4.0–4.5 kg were injected with a low dose of heparin (50 U/kg) before the experiment. An extracorporeal perfusion test as described before has been performed [23]. Briefly, all the samples were weighed before the test. Then, the TiO2-NTs and NTs-Ag on the Ti foils were rolled up and placed into a PVC catheter of xx mm inner diameter. After that, the PVC catheter was used to connect the rabbit's rabbit's unilateral carotid artery and contralateral jugular vein to let the blood flow through the samples surfaces for 30 min. Afterward, the samples were rinsed with physiological saline solution and fixed in glutaraldehyde solution for 12 h. Then, the samples were gradient dehydrated with ethanol, weighed, and the thrombus weight was calculated. Finally, the cells and fibrin fibers on the samples were observed by SEM.

2.6. Cells culture

In this experiment, peritoneal macrophages were obtained from Sprague-Dawley (SD) rats. Human umbilical vein ECs (HVECs) and artery SMCs (HVSMCs) were obtained from the newborn umbilical cord (Huaxi Hospital, Chengdu, China). The cell concentrations were 5×104 cells/mL for macrophages seeding, and 2×104 cells/mL for ECs and SMCs seeding.

Briefly, after autoclavation, the TiO2-NTs and NTs-Ag samples (7×7 mm2) were placed into a 24-well plate. Then 1 mL of cell culture medium containing cells was added. The samples were incubated in a cell incubator with 5% CO2 at 37 °C for 1 d or 3 d. Afterward, the samples were washed by PBS to remove non-attached cells and then fixed with a 2.5% glutaraldehyde for 12 h. Finally, the cells on the samples were stained by rhodamine and observed by a fluorescence microscope.

2.7. In vivo rat subcutaneous implantation

In this study, the selected samples, UNT-TiO2-NTs, UV-TiO2-NTs, UNT-NTs@Ag-2, and UV-NTs@Ag-2, were implanted in the subcutaneous tissue of the back of rats. The details of this experiment were the same as in our previous study [24].

2.8. Implantation of wire in vascular In vivo

The UNT-TiO2-NTs and UV-NTs@Ag-2 were fabricated on Ti wires with 0.2 mm diameter and 1 mm length. Then, the wires were implanted into the wall of the abdominal aorta of the Sprague−Dawley male rats (6 weeks old). Briefly, the rats were anesthetized by pentobarbital sodium, and their abdominal aortas were isolated. Then, the samples were implanted into the blood vessel and fixed to contact with the aorta intimately. After implantation (4 weeks), the samples and vascular tissues were collected together and fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde. After dehydration in increasing ethanol concentrations, de-alcoholation, and staining, the samples were further studied by histological examination.

2.9. Statistics

All the experiments were done in triplicate (n = 3). The statistical significance between the sample groups was assessed by SPSS11.5 software using one-way ANOVA and LSD posthoc test. A value of p < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

3. Results and disscusion

3.1. Surface characterization of the composited materials

Fig. 1(A) shows the process of preparation of TiO2-NTs decorated with AgNPs. A more detailed description is in section 2.1.

The SEM results in Fig. 1(B) confirm the successful formation of the TiO2-NTs with a diameter of about 70–100 nm. Moreover, after photo-reduction, some nanoparticles emerged on the TiO2-NTs surface. The size and amount of the nanoparticles increased with the photo-reduction time. The XRD spectra (Fig. 1(C)) indicated that the crystalline form of TiO2 was mainly anatase, but also contains small amounts of rutile. This anatase and rutile mixed TiO2 has been reported to have good photocatalytic properties [25]. The signal of Ag was observed on the NTs-Ag-4 samples, indicating the integration of silver in the coating. The Ag signal on other NTs-Ag samples decreased with the decrease of the photo-reduction time. XPS (Fig. 1(D)) revealed a clear Ag signal of the TiO2-NTs, even after a photo-reduction treatment time as short as 30 s. Finally, the EDS results (Fig. 1(E)) confirmed the nanoparticles on the NTs@Ag-4 to be silver nanoparticles (AgNPs). All the above results indicated that the TiO2-NTs and AgNPs composited materials were successfully fabricated.

3.2. The photo-induced functions of the composited materials

After 1, 3, and 5 h of UV irradiation, methylene blue (MB) degradation as an indicator of photocatalytic activity showed a linear dose dependence with the AgNPs loading on the surface of TiO2-NTs (Fig. 2(A)). This indicates that the addition of AgNPs enhanced the photocatalytic activity of TiO2-NTs, which can be attributed to the formation of a Schottky barrier between AgNPs and TiO2, which reduces the electron-hole recombination rate [26].

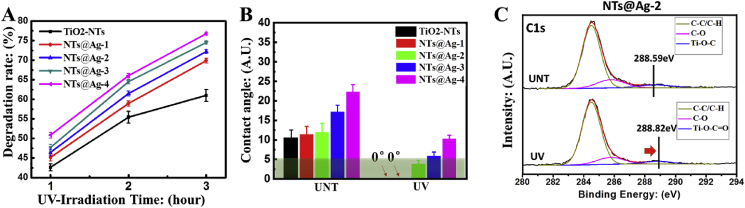

Fig. 2.

Characterization of the photo-induced functions of the composited materials. (A) Photocatalytic activity of samples determined by degradation of methylene blue (MB). (B) Hydrophilicity of samples before and after UV irradiation. (C) High-resolution spectra of the XPS C1s peak of NT@Ag-2 before and after 1 h UV irradiation. (For interpretation of the references to colour in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the Web version of this article.)

As shown in Fig. 2(B), due to the photo-induced hydrophilic (PIH) effect of TiO2 [27], the samples with UV radiation (UV-samples) were highly hydrophilic with water contact angles for TiO2-NTs, NTs@Ag-1 and NTs@Ag-2 below 5°, showing superhydrophilicity [28].

During the UV irradiation, the photo-generated reactive oxygen species (ROS) produced by TiO2 may oxidize the surface adsorbed hydrocarbons. As shown in Fig. 2(C), the high-resolution spectrum of XPS C1s of UNT-NTs@Ag-2 showed a shoulder at 288.59 eV, which may be attributed to the adsorbed oxygen-containing hydrocarbons [29]. After 1 h of UV irradiation, the shoulder of UV-NTs@Ag-2 shifted to 288.82 eV, which could be attributed to a Ti–O–C O structure [30]. The result indicated the oxidation of hydrocarbons on the Ag decorated TiO2-NTs during UV irradiation treatment.

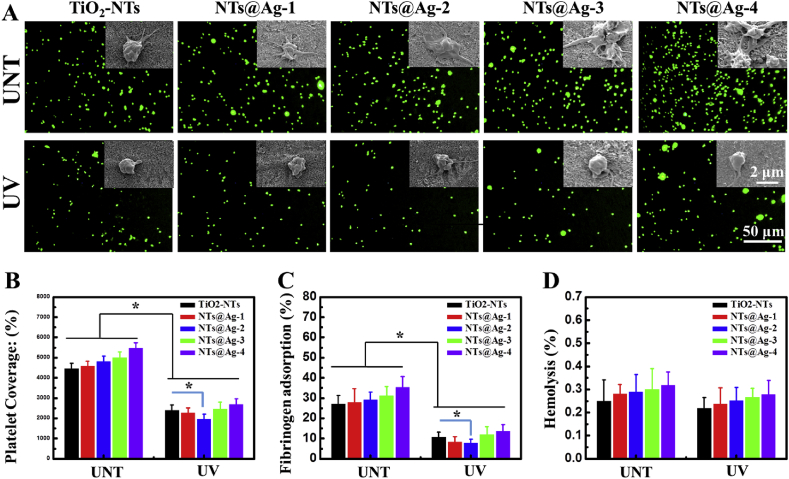

3.3. Evaluation of the blood compatibility of samples

The results of the platelet adhesion test are shown in Fig. 3(A and B). On the surface of UNT-samples, the amount of adhered platelets increased with the Ag loading density. Moreover, the SEM images showed that with increased AgNPs loading, platelets present more pseudopodia and spread larger, indicating higher activation [31]. This deterioration in anticoagulant properties of TiO2-NTs may be caused by the activating effect of AgNPs on platelets [32]. However, on the surface of the UV treated samples, the adhesion and spreading of platelets were strongly inhibited. Especially, the UV-NTs@Ag-2 showed the strongest photo-induced anticoagulant properties, which could be related to its enhanced photocatalytic activity and the relatively lower AgNPs loading amount. Although UV-NTs@Ag-3 and UV-NTs@Ag-4 showed a stronger photocatalytic activity than UV-NTs@Ag-2, their photo-induced anticoagulant properties were lower than those of UV-NTs@Ag-2. This indicates that at high AgNP concentrations their direct pro-coagulation effect exceeds, whereas at low concentrations the indirect thomboprotection via the photocatalytic effect is dominant.

Fig. 3.

In vitro blood compatibility characterization. (A) Fluorescent and SEM pictures of platelet adhesion after 1 min of incubation. (B) Platelet surface coverage of samples. (C) Relative quantification of Fgn adsorption. (D) Hemolysis rate of samples. Data are presented as mean ± SD (n ≥ 4) and analyzed using one-way ANOVA, *p < 0.05.

As shown in Fig. 3(C), the fibrinogen adsorption on the samples showed similar trends as the platelet adhesion. Loading AgNPs increased the adsorption of fibrinogen, which could be related to the high affinity of Ag to the S–S group or –SH group of proteins [33]. In contrast, UV irradiation strongly inhibited the fibrinogen adsorption, which could be related to its photo-induced hydrophilicity and the oxidation of surface hydrocarbons [9]. The NTs@Ag-2 showed the strongest fibrinogen fouling resistance, which could be related to the balance between its enhanced photocatalytic activity and a suitable amount of AgNPs.

A basic aspect of blood compatibility is no hemolysis, besides the anticoagulant properties. As shown in Fig. 3(D), all the samples induced only minimal hemolysis; for AgNTs@Ag-4, the hemolysis was enhanced only by about 0.05% compared to the bare TiO2 nanotubes. UV-NTs@Ag therefore appear safe for vascular implantation.

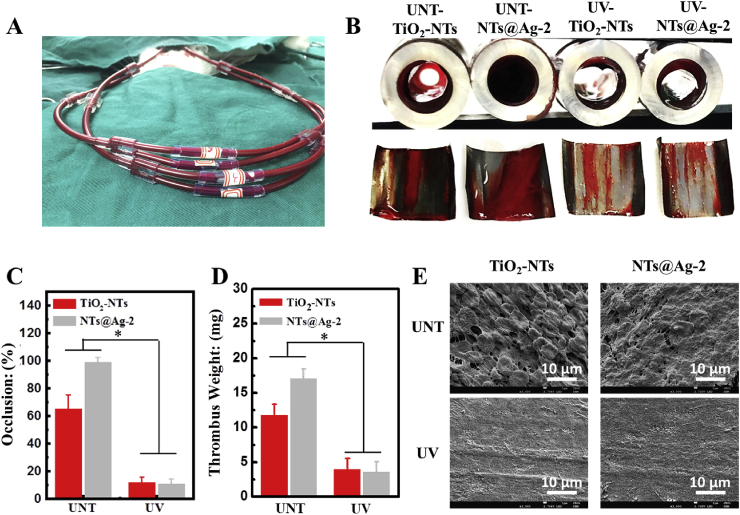

In this study, we constructed an ex-vivo blood circulation model (Fig. 4(A)) to further evaluate the anticoagulant property of the material in an environment closer to the in vivo environment [34]. As shown in Fig. 4(B and C), after 30 min ex-vivo blood circulation, catheters containing TiO2-NTs and NTs@Ag-2 without UV irradiation treatment were severely blocked by thrombi, with occlusion rates of 65.6% and 99.2%, respectively. However, the thrombotic occlusion rates for the UV irradiated TiO2-NTs and NTs@Ag-2 samples were significantly decreased to 11.7% and 10.9%, respectively. Fig. 4(D) shows the result of thrombus weighing. The thrombus weight on the surface of UNT-TiO2-NTs and UNT-NTs@Ag-2 was 12.2 and 17.2 mg, respectively. After UV irradiation, the weight of the thrombus on the surface of UV-TiO2-NTs and UV-NTs@Ag-2 significantly decreased to 3.7 and 3.5 mg, respectively. SEM results show (Fig. 4(E)) that the thrombus formed on UNT-TiO2-NTs contained a large number of accumulated blood cells, of which only the erythrocytes can still be distinguished. On UNT-NTs@Ag-2, the surface of erythrocytes in thrombus is further covered with a lot of fibrin fibers. In contrast, the UV pretreated samples exhibited strong photo-induced anticoagulant properties. No thrombus but only a small amount of platelet adhesion was observed. The above results suggest that the addition of AgNPs to TiO2-NTs leads to more severe coagulation. However, after being UV irradiation, these TiO2-NTs decorated with AgNPs exhibited powerful photo-induced anticoagulant properties, making up for the coagulation effect brought by AgNPs. Therefore, the composite material of TiO2-NTs and AgNPs obtains excellent anticoagulant properties through the synergistic and complementary effects of AgNPs and photofunctionalized TiO2.

Fig. 4.

Ex-vivo blood compatibility characterization. (A) Photo of the ex-vivo evaluation of anticoagulant properties. (B) Cross-sectional pictures of the catheters containing the samples after 30 min circulation with front view of the thrombus on sample surfaces. (C) Occlusion rate of samples. (D) Thrombosis weight on the samples. (E) SEM images of the samples. Data are presented as mean ± SD (n ≥ 4) and analyzed using one-way ANOVA, *p < 0.05.

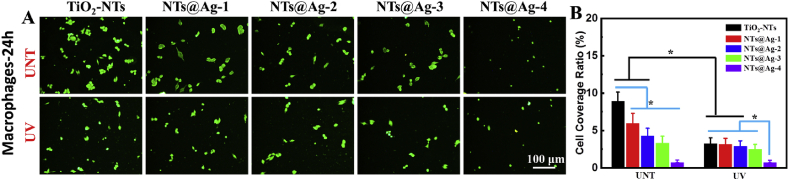

3.4. Evaluation of anti-inflammatory properties

Inflammation is an essential cause of proliferation and delayed endothelial repair after stent implantation [35]. Macrophages (MAs) play an important role in vascular inflammation. Therefore, we studied the adhesion and growth behavior of MAs on the surface of composite materials. As shown in Fig. 5(A and B), after 24 h of culture, a large number of MAs adhered to the surface of the TiO2-UNT sample, and the MAs showed the characteristics of spreading and reunion. With the gradual increase in the loading of AgNPs, the number of MAs adhering to the sample surface decreased. On the surface of NTs@Ag-4 with the highest load of AgNPs, only a few scattered MAs were observed. On the surface of UV-TiO2-NTs, UV-NTs@Ag-1, UV-NTs@Ag-2 after photo-functionalization, the number of MAs decreased significantly compared to the samples without UV treatment, indicating that the photo-functionalization of TiO2 and AgNPs exhibited synergistic inhibition of MAs adhesion and growth. With the further increase of AgNPs loading, on UV-NTs@Ag-3 and UV-NTs@Ag-4, the direct inhibitory effect of AgNPs on macrophages could play the dominant role.

Fig. 5.

Adhesion and growth behavior of macrophages (MAs) on material surfaces after cultured for 1 day. (A) MAs on the samples observed by fluorescence microscopy. (B) Results of cell density statistics. Data are presented as mean ± SD (n ≥ 6) and analyzed using one-way ANOVA, *p < 0.05.

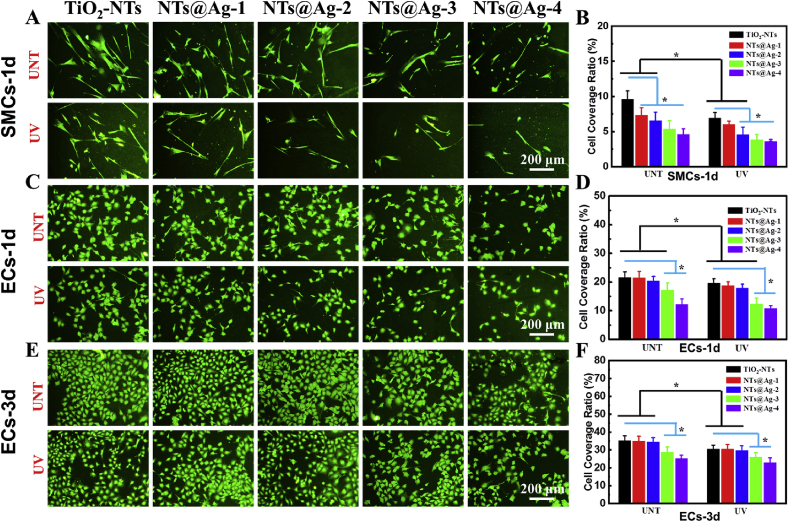

3.5. Adhesion and growth behavior of ECs and SMCs on samples

The growth behavior of SMCs and ECs on vascular stent materials plays a vital role for the reconstruction of blood vessels and stent surface after stent implantation. Excessive proliferation of smooth muscle tissue causes restenosis in the stent [36]. The complete re-endothelialization of the stent surface, therefore, is the key to the success of the stent-implantation [37]. Drug-eluting stents non-selectively inhibit smooth muscle tissue proliferation and the endothelialization process on the surface of the stent, which is likely to cause the severe side effect of late thrombosis [38]. Therefore, drawing on the lessons of drug-eluting stents, the new generation of stents should suppress the growth of SMCs while minimizing the inhibition of ECs growth.

The adhesion and growth behavior of SMCs and ECs on composite materials' surfaces here is studied in vitro. One-day cell culture (Fig. 6(A and B)) showed that AgNPs loading, or UV irradiation pretreatment increased the ability of TiO2-NTs to inhibit SMCs growth. On the sample surface without UV treatment, the adhesion and aggregation of SMCs decreased significantly with the increase of AgNPs loading. Among the samples with high AgNPs loading, the number of SMCs did not drop further after UV irradiation pretreatment, indicating that a large number of AgNPs dominate the inhibition effect on SMCs. However, on the samples with low AgNPs loading, UV irradiation further reduced the number of SMCs. On these samples, AgNPs and photofunctionalized TiO2 showed a synergistic inhibition effect on SMCs.

Fig. 6.

SMCs and ECs culture experiments. (A) Rhodamine staining of SMCs, and (B) SMCs surface coverage on the samples cultured for 1 day. (C) Rhodamine staining of ECs, and (D) ECs surface coverage on the samples cultured for 1 day. (E) Rhodamine staining of ECs, and (F) ECs surface coverage on the samples cultured for 3 days. Data are presented as mean ± SD (n ≥ 6) and analyzed using one-way ANOVA, *p < 0.05.

Concerning ECs, UV irradiation and high-dose AgNPs loading inhibited ECs adhesion after 1-day culture (Fig. 6(C and D)) on TiO2-NTs. At the same time, low-dose AgNPs loading showed low toxic to ECs. In detail, compared with the untreated samples, UV-TiO2-NTs, UV-NTs@Ag-1, UV-NTs@Ag-2 only showed the inhibitory effect of photofunctionalized TiO2 on ECs. UV-NTs@Ag-3 embodied the synergistic inhibition of photofunctionalization and AgNPs. UV-NTs@Ag-4 only showed the inhibitory effect of a large number of AgNPs on ECs. ECs culture for 3 days had the same trends as culture for 1 day.

Based on the culture results of SMCs and ECs, the ratio of SMCs surface coverage on UNT-TiO2 was 9.6% (1 d), and the ECs surface coverage was 21.5% (1 d) and 34.2% (3 d). On UV-NTs@Ag-2, the surface coverage of SMCs was 4.7% (1 d), and the surface coverage of ECs was 19.3% (1 d) and 30.1% (3 d), showed significant SMCs inhibitory effect and very low inhibitory effect on ECs, and thus have potential as a vascular stent coating.

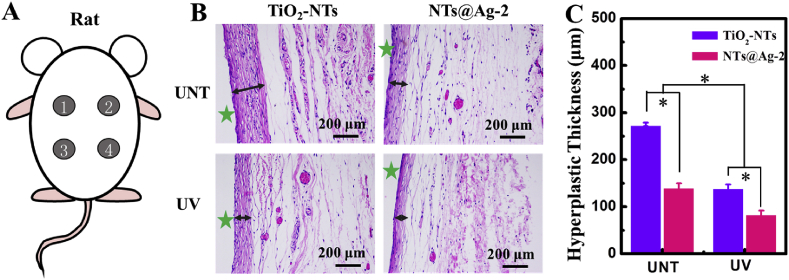

3.6. Evaluation of tissue compatibility in vivo

Subcutaneous implantation experiments on the back of a rat were selected as a simple and effective method to study the tissue compatibility of the photo-functionalized composite material [39]. As shown in Fig. 7(A), after implantation for 4 weeks, the thickness of newly formed tissue on the samples decreased in the order: UNT-TiO2-NTs > UNT-NTs@Ag-2 ≈ UV-TiO2-NTs > UV-NTs@Ag (Fig. 7(B and C)). Both loading AgNPs on TiO2-NTs or treating TiO2-NTs with UV reduced tissue proliferation. The UV-TiO2-NTs showed the best antiproliferative property in all samples, with a thickness of the newly formed tissue of less than one-third of the hyperplastic tissue on UNT-TiO2-NTs, as an effect of the synergy of photofunctionalization of TiO2 and AgNPs.

Fig. 7.

Subcutaneous implantation of samples to evaluate the tissue compatibility. (A) Schematic diagram of subcutaneous implantation in the back of a rat. (B) H&E staining of hyperplastic tissue after 4 weeks of implantation. (C) Thickness of hyperplastic tissue. Data are presented as mean ± SD (n ≥ 3) and analyzed using one-way ANOVA, *p < 0.05.

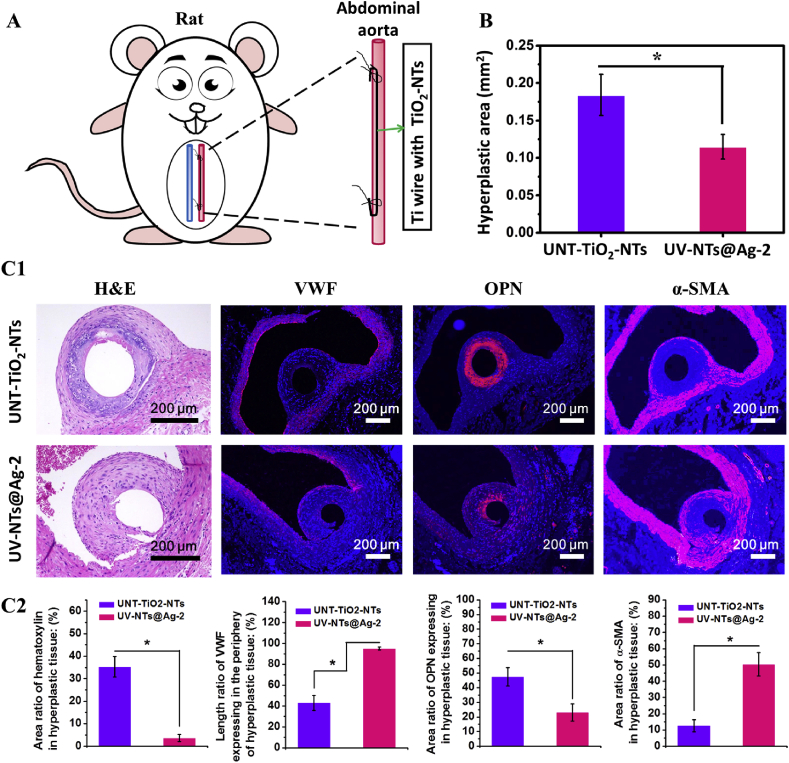

3.7. Evaluation of vascular biocompatibility in vivo

As shown in Fig. 8(A), we comprehensively evaluated the vascular biocompatibility of the photo-functionalized composite material through the rat abdominal aortic graft model. As shown in Fig. 8(B), after 4 weeks of implantation, the cross-sectional area of the hyperplastic tissue around the implant UV-NTs@Ag-2 was decreased by about 33% relative to the control sample (UNT-TiO2-NTs). The photo-functionalized composite material showed a good anti-proliferative effect in blood vessels. Fig. 8 (C1, C2) shows the histological images of the hyperplastic tissue on the sample surface and their quantitative evaluation:

-

(1)

The H&E stains showed a large number of (hematoxylin)-stained cells aggregated in the hyperplastic tissue around UNT-TiO2-NTs, indicating the aggregation of monocytes [40]. In contrast, the monocyte aggregation was not observed in the hyperplastic tissue around UV-NTs@Ag-2. The statistical results of H&E staining showed that hematoxylin (monocytes) accounted for 35.2% and 3.7% of the cross-section in the newborn tissues around UNT-TiO2-NTs and UV-NTs@Ag-2, respectively. This result indicated that UV-NTs@Ag-2 had anti-inflammatory effects in blood vessels.

-

(2)

The vWF stains showed that vWF was expressed only sporadically at the luminal surface of the UNT-TiO2-NTs hyperplastic tissue. In contrast, there was continuous and complete vWF expression at the luminal surface of the UV-NTs@Ag-2 hyperplastic tissue. Quantification of the vWF stains showed that the length of the VWF expression accounted for 43.0% and 95.2% of the edge of the newly formed tissue around UNT-TiO2-NTs and UV-NTs@Ag-2, respectively. This result indicated that UV-NTs@Ag-2 achieved a substantially complete endothelialization in blood vessels [41].

-

(3)

The OPN stains showed a larger number of OPN-positive cells, which are regarded as synthetic SMCs [42], aggregated in the hyperplastic tissue around UNT-TiO2-NTs compared to UV-NTs@Ag-2. OPN quantification shows that in the new tissue surrounding UNT-TiO2-NTs and UV-NTs@Ag-2, the OPN positive expression areas account for 47.5% and 23.1% of the tissue cross-section, respectively. This result suggested that UV-NTs@Ag-2 suppresses the conversion of SMCs or fibroblasts to a synthetic phenotype and reduces the proliferation of new tissue, which may also inhibit the restenosis in a stent.

-

(4)

The α-SMA stains showed a small amount of α-SMA positive expression around the OPN positive expression regions in the hyperplastic tissues of UNT-TiO2-NTs. However, in the hyperplastic tissue of UV-NTs@Ag-2, there was a strong α-SMA positive expression around the OPN positive cell aggregation. The quantitative evaluation of α-SMA staining showed that α-SMA positive expression areas accounted for 12.6% and 50.3% of the tissue cross-sections in the new tissues around UNT-TiO2-NTs and UV-NTs@Ag-2, respectively. It can be concluded that UV-NTs@Ag-2 had the function of maintaining the contractile phenotype of SMCs to enhance vascular stability, which might provide a stable environment for the repair of ECs [43].

Fig. 8.

Implantation of the samples in abdominal aortas of SD rats for 4 weeks to evaluate the vascular biocompatibility. (A) Schematic diagram of implantation. (B) Statistical analysis of the area of the new hyperplastic tissue. (C1) Hematoxylin&eosin (H&E), von Willebrand factor (vWF), Osteopontin (OPN), and alpha smooth muscle cell actin (α-SMA) staining of the hyperplastic tissue in the abdominal aorta. (C2) Quantification of hematoxylin, VWF, OPN, and α-SMA images. Data are presented as mean ± SD (n ≥ 3) and analyzed using one-way ANOVA, *p < 0.05.

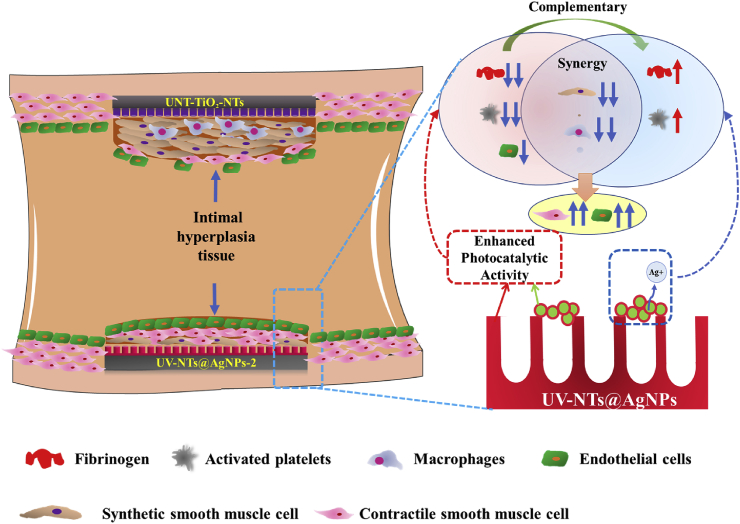

Here, we summarized the possible interaction mechanism between the photo-functionalized composite material and the vascular tissue after implantation. As shown in Fig. 9, when exposed to UV irradiation, through the Schottky barrier, AgNPs promote the photocatalytic activity of TiO2, which enhanced the photo-induced anticoagulant properties of UV-NTs@Ag-2. The enhanced photo-induced anticoagulation outplayed the procoagulant effect of AgNPs. The photo-functionalized TiO2, AgNPs, and Ag+ released by AgNPs synergistically suppressed the inflammation in the blood vessels and the excessive proliferation of synthetic SMCs, reducing the tissue hyperplasia on the material surface. Besides, although photo-functionalized TiO2 had an inhibitory effect on ECs, the inhibition of inflammation and proliferation of synthetic SMCs by photo-functionalized composite materials benefited to the contractile SMCs, which might provide a stable environment for the ECs to cover the new tissues. Finally, through the synergy and complementary effects of the photo-functionalized TiO2 and AgNPs, the photo-functional UV-NTs@Ag-2 composite material exhibited good anti-proliferative ability and promoted the repairment of ECs, thus exhibited excellent vascular biocompatibility.

Fig. 9.

Schematic representation of photo-functionalized TiO2 and multifunctional AgNPs to enhance vascular biocompatibility of the composite materials through complementary and synergistic effects.

4. Conclusion

In this study, we successfully prepared AgNPs-decorated TiO2-NTs composites and modified them using UV irradiation. The modified composite material obtains multiple biological functions of anti-blood protein pollution, anti-coagulation, anti-inflammatory, and selective inhibition of SMCs through the synergistic and complementary effects of the photofunctionalized TiO2-NTs and the multifunctional AgNPs. In vivo evaluation showed that the photo-functionalized composite material had beneficial effects of inhibiting hyperplasia and promoting ECs repair in blood vessels. Our research shows that loading the appropriate amount of noble metals may be an effective method to enhance the vascular compatibility of the photo-functionalized TiO2. This photo-functional TiO2 @ noble metals composites might have wide applications in the field of blood implantable devices, especially for long-term blood implantable devices.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Jiang Chen: Conceptualization, Writing - original draft. Sheng Dai: Data curation. Luying Liu: Data curation. Manfred F. Maitz: Writing - review & editing. Yuzhen Liao: Writing - review & editing. Jiawei Cui: Writing - review & editing. Ansha Zhao: Conceptualization. Ping Yang: Writing - review & editing. Yunbing Wang: Conceptualization.

Declaration of competing interest

None.

Acknowledgement

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (nos. 31870958, 31700821, and 81771988).

Footnotes

Peer review under responsibility of KeAi Communications Co., Ltd.

Contributor Information

Jiang Chen, Email: chenjiang@my.swjtu.edu.cn.

Sheng Dai, Email: 1147976572@qq.com.

Luying Liu, Email: 1175116619@qq.com.

Manfred F. Maitz, Email: manfred@maitz-online.de.

Yuzhen Liao, Email: 94374283@qq.com.

Jiawei Cui, Email: 1563798788@qq.com.

Ansha Zhao, Email: anshazhao@263.net.

Ping Yang, Email: yangping8@263.net.

Nan Huang, Email: huangnan1956@163.com.

Yunbing Wang, Email: yunbing.wang@scu.edu.cn.

References

- 1.Wei Y., Ma Y., Chen J., Yang X., Ni S., Hong F., Ni S. Novel ordered TiO2 nanodot array on 316LSS with enhanced antibacterial properties. Mater. Lett. 2020;266:127503. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zhao Y., Tu Q., Wang J., Huang Q., Huang N. Crystalline TiO2 grafted with poly(2-methacryloyloxyethyl phosphorylcholine) via surface-initiated atom-transfer radical polymerization. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2010;257(5):1596–1601. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Xiao Y., Wang W., Tian X., Tan X., Yang T., Gao P., Xiong K., Tu Q., Wang M., Maitz M.F., Huang N., Pan G., Yang Z. A versatile surface bioengineering strategy based on mussel-inspired and bioclickable peptide mimic. Research. 2020;2020:12. doi: 10.34133/2020/7236946. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Roy S.C., Paulose M., Grimes C.A. The effect of TiO2 nanotubes in the enhancement of blood clotting for the control of hemorrhage. Biomaterials. 2007;28(31):4667–4672. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2007.07.045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Yang Y., Li X., Qiu H., Li P., Qi P., Maitz M.F., You T., Shen R., Yang Z., Tian W., Huang N. Polydopamine modified TiO2 nanotube Arrays for long-term controlled elution of bivalirudin and improved hemocompatibility. Acs Appl. Mater. Inter. 2018;10(9):7649–7660. doi: 10.1021/acsami.7b06108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Liu T., Zeng Z., Liu Y., Wang J., Maitz M.F., Wang Y., Liu S., Chen J., Huang N. Surface modification with dopamine and heparin/poly-l-lysine nanoparticles provides a favorable release behavior for the healing of vascular stent lesions. Acs Appl. Mater. Inter. 2014;6(11):8729–8743. doi: 10.1021/am5015309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yang Z., Wang J., Luo R., Li X., Chen S., Sun H., Huang N. Improved hemocompatibility guided by pulsed plasma tailoring the surface amino functionalities of TiO2 coating for covalent immobilization of heparin. Plasma Process. Polym. 2011;8(9):850–858. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chen J., Zhao A., Chen H., Liao Y., Yang P., Sun H., Huang N. The effect of full/partial UV-irradiation of TiO2 films on altering the behavior of fibrinogen and platelets. Colloids Surf. B Biointerfaces. 2014;122:709–718. doi: 10.1016/j.colsurfb.2014.08.004. 0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chen J., Yang P., Liao Y., Wang J., Chen H., Sun H., Huang N. Effect of the duration of UV irradiation on the anticoagulant properties of titanium dioxide films. Acs Appl. Mater. Inter. 2015;7(7):4423–4432. doi: 10.1021/am509006y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Liao Y., Li L., Chen J., Yang P., Zhao A., Sun H., Huang N. Tailoring of TiO2 films by H2SO4 treatment and UV irradiation to improve anticoagulant ability and endothelial cell compatibility. Colloids Surf. B Biointerfaces. 2017;155(Supplement C):314–322. doi: 10.1016/j.colsurfb.2017.04.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yang Y., Gao P., Wang J., Tu Q., Bai L., Xiong K., Qiu H., Zhao X., Maitz M.F., Wang H., Li X., Zhao Q., Xiao Y., Huang N., Yang Z. Endothelium-mimicking multifunctional coating modified cardiovascular stents via a stepwise metal-catechol-(amine) surface engineering strategy. Research. 2020;2020:20. doi: 10.34133/2020/9203906. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kim S.B., Hong S.C. Kinetic study for photocatalytic degradation of volatile organic compounds in air using thin film TiO2 photocatalyst. Appl. Catal. B Environ. 2002;35(4):305–315. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yamashita H., Harada M., Misaka J., Takeuchi M., Neppolian B., Anpo M. Photocatalytic degradation of organic compounds diluted in water using visible light-responsive metal ion-implanted TiO2 catalysts: Fe ion-implanted TiO2. Catal. Today. 2003;84(3):191–196. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Liu X., Chen J., Qu C., Bo G., Jiang L., Zhao H., Zhang J., Lin Y., Hua Y., Yang P., Huang N., Yang Z. A mussel-inspired facile method to prepare multilayer-AgNP-loaded contact lens for early treatment of bacterial and fungal keratitis. ACS Biomater. Sci. Eng. 2018;4(5):1568–1579. doi: 10.1021/acsbiomaterials.7b00977. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ramírez-Lee M.A., Rosas-Hernández H., Salazar-García S., Gutiérrez-Hernández J.M., Espinosa-Tanguma R., González F.J., Ali S.F., González C. Silver nanoparticles induce anti-proliferative effects on airway smooth muscle cells. Role of nitric oxide and muscarinic receptor signaling pathway. Toxicol. Lett. 2014;224(2):246–256. doi: 10.1016/j.toxlet.2013.10.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Stevens K.N.J., Croes S., Boersma R.S., Stobberingh E.E., van der Marel C., van der Veen F.H., Knetsch M.L.W., Koole L.H. Hydrophilic surface coatings with embedded biocidal silver nanoparticles and sodium heparin for central venous catheters. Biomaterials. 2011;32(5):1264–1269. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2010.10.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Shi Q., Wang X., Yu W., Huang R. [Influence of the concentration of silver nanoparticles on the proliferation behavior of human umbilical vein endothelial cell and human umbilical artery smooth muscle cells] Sheng Wu Yi Xue Gong Cheng Xue Za Zhi. 2010;27(4):875–881. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Piwoński I., Spilarewicz-Stanek K., Kisielewska A., Kądzioła K., Cichomski M., Ginter J. Examination of Ostwald ripening in the photocatalytic growth of silver nanoparticles on titanium dioxide coatings. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2016;373:38–44. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hernández-Gordillo A., González V.R. Silver nanoparticles loaded on Cu-doped TiO2 for the effective reduction of nitro-aromatic contaminants. Chem. Eng. J. 2015;261:53–59. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Qiu Y., Ouyang F. Fabrication of TiO2 hierarchical architecture assembled by nanowires with anatase/TiO2(B) phase-junctions for efficient photocatalytic hydrogen production. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2017;403:691–698. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Petronella F., Truppi A., Sibillano T., Giannini C., Striccoli M., Comparelli R., Curri M.L. Multifunctional TiO2/FexOy/Ag based nanocrystalline heterostructures for photocatalytic degradation of a recalcitrant pollutant. Catal. Today. 2017;284:100–106. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Yang T., Du Z., Qiu H., Gao P., Zhao X., Wang H., Tu Q., Xiong K., Huang N., Yang Z. From surface to bulk modification: plasma polymerization of amine-bearing coating by synergic strategy of biomolecule grafting and nitric oxide loading. Bioactive Mater. 2020;5(1):17–25. doi: 10.1016/j.bioactmat.2019.12.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Yang Z., Zhao X., Hao R., Tu Q., Tian X., Xiao Y., Xiong K., Wang M., Feng Y., Huang N., Pan G. Bioclickable and mussel adhesive peptide mimics for engineering vascular stent surfaces. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. Unit. States Am. 2020:202003732. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2003732117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jiang T., Xie Z., Wu F., Chen J., Liao Y., Liu L., Zhao A., Wu J., Yang P., Huang N. Hyaluronic acid nanoparticle composite films confer favorable time-dependent biofunctions for vascular wound healing. ACS Biomater. Sci. Eng. 2019;5(4):1833–1848. doi: 10.1021/acsbiomaterials.9b00295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Li H., Shen X., Liu Y., Wang L., Lei J., Zhang J. Facile phase control for hydrothermal synthesis of anatase-rutile TiO2 with enhanced photocatalytic activity. J. Alloys Compd. 2015;646:380–386. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tahir K., Ahmad A., Li B., Nazir S., Khan A.U., Nasir T., Khan Z.U.H., Naz R., Raza M. Visible light photo catalytic inactivation of bacteria and photo degradation of methylene blue with Ag/TiO2 nanocomposite prepared by a novel method. J. Photochem. Photobiol. B Biol. 2016;162:189–198. doi: 10.1016/j.jphotobiol.2016.06.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wang R., Hashimoto K., Fujishima A., Chikuni M., Kojima E., Kitamura A., Shimohigoshi M., Watanabe T. Light-induced amphiphilic surfaces. Nature. 1997;388(6641):431–432. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Miyauchi M., Tokudome H. Low-reflective and super-hydrophilic properties of titanate or titania nanotube thin films via layer-by-layer assembly. Thin Solid Films. 2006;515(4):2091–2096. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Aita H., Att W., Ueno T., Yamada M., Hori N., Iwasa F., Tsukimura N., Ogawa T. Ultraviolet light-mediated photofunctionalization of titanium to promote human mesenchymal stem cell migration, attachment, proliferation and differentiation. Acta Biomater. 2009;5(8):3247–3257. doi: 10.1016/j.actbio.2009.04.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Xing M., Shen F., Qiu B., Zhang J. Highly-dispersed boron-doped graphene nanosheets loaded with TiO2 nanoparticles for enhancing CO2 photoreduction. Sci Rep-Uk. 2014;4(1):6341. doi: 10.1038/srep06341. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Goodman S.L., Grasel T.G., Cooper S.L., Albrecht R.M. Platelet shape change and cytoskeletal reorganization on polyurethaneureas. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. 1989;23(1):105–123. doi: 10.1002/jbm.820230109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ragaseema V.M., Unnikrishnan S., Kalliyana Krishnan V., Krishnan L.K. The antithrombotic and antimicrobial properties of PEG-protected silver nanoparticle coated surfaces. Biomaterials. 2012;33(11):3083–3092. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2012.01.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Jiang L., Guo D., Wang L., Chang S., Li J.-B., Zhan D.-S., Fodjo E.K., Gu H.-X., Li D.-W. Sensitive and selective SERS probe for detecting the activity of γ-glutamyl transpeptidase in serum. Anal. Chim. Acta. 2020;1099:119–125. doi: 10.1016/j.aca.2019.11.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Qiu H., Qi P., Liu J., Yang Y., Tan X., Xiao Y., Maitz M.F., Huang N., Yang Z. Biomimetic engineering endothelium-like coating on cardiovascular stent through heparin and nitric oxide-generating compound synergistic modification strategy. Biomaterials. 2019;207:10–22. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2019.03.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Inoue T., Croce K., Morooka T., Sakuma M., Node K., Simon D.I. Vascular inflammation and repair, implications for Re-endothelialization. Restenosis Stent Thrombosis. 2011;4(10):1057–1066. doi: 10.1016/j.jcin.2011.05.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Orford J.L., Selwyn A.P., Ganz P., Popma J.J., Rogers C. The comparative pathobiology of atherosclerosis and restenosis. Am. J. Cardiol. 2000;86(4):6H–11H. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9149(00)01094-8. Supplement 2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Su L.-C., Xu H., Tran R.T., Tsai Y.-T., Tang L., Yang J., Nguyen K.T. Abstract 291: in situ Re-endothelialization via multifunctional nanoscaffolds. Atertio. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 2013;33(suppl_1) A291-A291. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wang J., Jin X., Huang Y., Ran X., Luo D., Yang D., Jia D., Zhang K., Tong J., Deng X., Wang G. Endovascular stent-induced alterations in host artery mechanical environments and their roles in stent restenosis and late thrombosis. Regen. Biomater. 2018;5(3):177–187. doi: 10.1093/rb/rby006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Yang Z., Qiu H., Li X., Gao P., Huang N. Plant-inspired gallolamine catalytic surface chemistry for engineering an efficient nitric oxide generating coating. Acta Biomater. 2018;76:89–98. doi: 10.1016/j.actbio.2018.06.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Yu X., Antoniades H.N., Graves D.T. Expression of monocyte chemoattractant protein 1 in human inflamed gingival tissues. Infect. Immun. 1993;61(11):4622–4628. doi: 10.1128/iai.61.11.4622-4628.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Jaffe E.A., Hoyer L.W., Nachman R.L. Synthesis of von Willebrand factor by cultured human endothelial cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. Unit. States Am. 1974;71(5):1906–1909. doi: 10.1073/pnas.71.5.1906. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Liu K., Fang C., Shen Y., Liu Z., Zhang M., Ma B., Pang X. Hypoxia-inducible factor 1a induces phenotype switch of human aortic vascular smooth muscle cell through PI3K/AKT/AEG-1 signaling. Oncotarget. 2017;8(20):33343–33352. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.16448. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 43.Sharifpoor S., Simmons C.A., Labow R.S., Paul Santerre J. Functional characterization of human coronary artery smooth muscle cells under cyclic mechanical strain in a degradable polyurethane scaffold. Biomaterials. 2011;32(21):4816–4829. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2011.03.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]