Abstract

The study investigated why sustainable technologies are not used to collect, dismantle and sell e-waste at Agbogbloshie given the risk of injury and extensive environmental pollution associated with handling of electronic waste. The study objectives were to examine the nature of technologies adopted to manage e-waste, assess challenges faced in adopting sustainable technologies; determine the missing links between formal and informal e-waste workers. Research questions were; what is the current level of technology adopted to manage e-waste and challenges limiting the adoption of sustainable technologies; and what are the missing links between the formal and informal sectors that limit adoption of sustainable e-waste management strategies. Data collection involved use of questionnaire to gather data on technologies used for e-waste management, challenges faced in using such technologies and what the workers consider as solutions to sustainable e-waste management. Field observations helped to explain waste management operations and questionnaire responses were analyzed using descriptive statistics. Study results show most of the e-waste workers are youthful and not much educated. The use of unsustainable technologies to manage e-waste has contributed to physical injuries to workers and pollution of the environment. A major challenge limiting the use of sustainable technologies is lack of financial resources to acquire modern equipment despite the laborious nature of the work. The paper concludes that sustainable solutions to electronic waste management requires support from government to subsidize the cost of sustainable technologies in e-waste management.

Keywords: Electronic waste, Sustainability, Environment, Pollution

electronic waste; sustainability; environmental; Pollution, Agricultural Water Management; Environmental Analysis; Environmental Assessment; Geography; Remote Sensing; Tourism; Environmental science, Agriculture.

1. Introduction

Electronic waste (e-waste) refers to broken down electronic devices that are no longer useful for the purposes they were intended for (Luther, 2009). The definition includes Electrical or Electronic Equipment's (EEE) that use electric power but have reached their end-of-life. Other components of e-waste such as power cables, sub assemblages and consumables that are part of electronic products at the time of discarding them are part of the waste (European Union, 2002; UNEP, 2007). The definition of e-waste includes electronic products that are not spoilt but discarded by their owners (UNU/Step, 2014).

Electronic waste is not just waste in the real sense, but a great business opportunity for those engaged in the selling and recycling of the waste. As a result, large inflow of Electronic waste into developing countries has occurred due to weak regulatory standards and poor enforcement of environmental laws when it comes to extraction and handling of valuable metals such as silver, gold and iron from e-waste (Chatterjee, 2012). In essence, African countries such as Kenya was considered the highest importer of electronic waste in 2010 when it imported, 1,400 tons of refrigerators, 2,800 tons of TV sets, 2,500 tons of personal computers, 500 tons of printers and 150 tons of mobile phone wastes (UNEP, 2010). In the USA, 3 million tons of e-waste is produced annually and 2.3 million tons are produced in China per annum (Finlay, 2005).

Unfortunately, most people only see social and economic opportunities when burning, and dismantling e-waste without being conscious of the health hazards and negative impacts (European Commission, 2010; Borthakur and Govind, 2018). In view of the fact that e-waste contains hazardous chemicals and materials such as cadmium, mercury and lead that are harmful to people and the environment, attention has to be paid to sustainable management practices (Zafar, 2016; Shaw, 2016). Realizing the dangers of handling e-waste in the informal sector, the Basel Convention Regional Centre was set up to build the capacity of informal e-waste managers in Nigeria, Senegal and Egypt on hazardous waste management (www.basel.int?/tabid=2334). This initiative is to create public awareness on the hazardous nature of chemical elements contained in e-waste and the effects on human health Otieno and Omwenga (2016) and the environment as ozone depleting gasses such as chlorofluorocarbons (CFCs) are found in e-waste (Maria-Grazia, 2016).

1.1. E-waste management and use of sustainable technologies

The rapid increase in e-waste has led to global calls for adopting proper management systems (Lundgren, 2012). Most developed countries export their electronic wastes to developing countries because of the high labour costs incurred to dismantle and recycle e-waste (Badoni, 2017). In developing countries however, the use of crude methods has lowered the cost of processing e-waste in countries such as China, India and Pakistan (Badoni, 2017). Application of crude methods to manage e-waste such as burning and dissolution of items in strong acids with little or no effort to protect human health and the environment are practices that deserve sustainable solutions (Prakash et al., 2010).

Sustainable approaches to e-waste management come in different dimensions such as developing strong policies, building capacity and application of efficient technologies to dismantle and recycle e-waste. The Extended Producer Responsibility policy for example, ensures that administrative, financial and physical e-waste management responsibilities are shifted from Government to companies producing and selling electronic products (Esenduran et al., 2019). In the case of Switzerland, the Extended Producer Responsibility (EPR) and the Advance Recycling Fee (AFR) policy ensure producers and importers of EEE manage e-waste products (EU–WEEE Directive, 2003; Sinha-Khetriwal et al., 2005). In Japan, the Consumer Pays model requires retailers to take back EEE sold to customers when the equipment's become obsolete by paying a fee to retail outlets as they take back the e-waste (Widmer et al., 2005). In the USA individual state legislations co-exist with the National Electronic Action Plans initiated by the US Environmental Protection Agency to ensure efficient e-waste management (Gaidajis et al., 2010).

In developing countries attempts to promote sustainable e-waste management include building the capacity of the informal sector to collect and recycle e-waste using safe technologies to prevent health and environmental consequences (World Resources Forum, 2019). In Peru the technical capacity of e-waste workers were built to use hydraulic compaction machines and disassembling electronic equipment's with pneumatic systems (WEE-Peru, 2015). In Columbia 185 tons of mobile phone waste in 30 cities were collected and recycled from 2007 to 2014 (GSMA-LATAM, 2015).

1.2. E-waste management challenges in Ghana

Ghana has an open door policy that allows the import of e-waste that is sold to individuals and companies as second hand electronic goods and spare parts (Oteng-Ababio (2012). In Ghana, items that have reached their end of life are collected door to door by scrap dealers who pay fees to owners of the waste and later re-sell to small and medium e-waste traders or wholesalers (Tetteh, 2018). Dealers in e-waste who are responsible for recycling, processing, refurbishment, reuse and residual disposal of e-waste at Agbogbloshie have adopted crude methods such as use of hammers and stones to dismantle e-waste (Oteng-Ababio and Amankwaa, 2014). Hand sorting of hazardous waste and open burning of e-waste considered injurious to people's health are common practices (Oteng-Ababio and Amankwaa, 2014). Disrespect, false accusations, neglect, and exclusion of informal e-waste workers from planning and capacity building initiatives have made it difficult to find solutions to manage electronic waste in Ghana (Amuzu, 2018).

Enactment of Act 917 has provided a legal backing to establish a national e-waste plant to address e-waste management (Quaye et al., 2019). Under Act (917) of 2016, a manufacturer or importer of an electronic equipment is required to register with the Environmental Protection Agency of Ghana and pay an electronic waste levy. The imposition of the levy is to cater for the costs of the collection, treatment, recovery and environmentally sound disposal and recycling of e-waste. There is also a pilot remediation project at Agbogbloshie initiated by the Blacksmith Institute, now Pure Earth to demonstrate environmentally sound remediation of a site contaminated by crude e-waste recycling operations (www.pureearth.org). Even though the legal frame work is aimed at addressing e-waste management the informal sector that is a major player has been left out. To bridge this gap, the Ministry of Environment, Science, Technology & Innovation and the German Government have proposed business models to build the capacity of informal e-waste workers to manage and recycle e-waste sustainably (World Resources Forum, 2019).

1.3. Chemical components of E-waste and their effects (Table 1)

Table 1.

Chemical Sources and their Effects (Source: Developed from Huang et al., 2014).

| Chemical | Main Source | Effects on environment & human health |

|---|---|---|

| Lead (Pb) | Glass of cathode ray tubes (CRT) in television sets/computer monitors, Acid batteries; Polyvinyl chloride (PVC) cables |

Lead do accumulates in the bodies of water and soil organisms leading to poisoning; Pb can enter the human body through uptake of food, water and breathing of air as such can be found in food such as fruits, vegetables, meat, grain, and seafood. Lead can cause several unwanted effects, such as:

|

| Beryllium | Connectors; Mother boards and finger clips |

When inhaled, beryllium compounds can lead to an irreversible and sometimes fatal scarring of the lungs-berylliosis or chronic beryllium disease (CBD). Can affect other organs, such as the lymph nodes, skin, spleen, liver, kidneys, and heart. |

| Polychlorinated biphenyls (PCBs) | Electrical transformers, capacitors of TV sets, computer monitors & radios, PVC | Chloracne and related dermal lesions have been reported in workers occupationally exposed to PCBs; Others are pigmentation disturbances of skin and nails, erythema and thickening of the skin, and burning sensations; Reproductive function may be disrupted by exposure to PCBs; Neurobehavioral and developmental deficits have been reported in newborns exposed to PCBs in utero. |

| Mercury (Hg) | Batteries, flat screen TV Sets, switches, relays, computer housing | When products and wastes containing mercury are improperly disposed, mercury is released into the air, ground or water. Mercury is persistent in the environment --it never breaks down or goes away. Exposure to mercury can affect thinking, memory, attention, language, fine motor skills and visual-spatial abilities. |

| Barium | CRT, Vacuum tubes | As a result of extensive use of barium in e-waste, its concentration in air, water and soil may be higher than naturally occurring concentrations on many locations. Most of the health risks that people working on e-waste are exposed to includes paralyses and in some cases even death |

| Chromium | Steel housing of CPU, chrome plating and in metal ceramics. | The uptake of too much chromium can cause health effects as well, for instance skin rashes, upset stomachs and ulcers, respiratory problems; weakened immune systems, kidney and liver damage, alteration of genetic material, lung cancer and even death. |

| Cadmium (Cd) | Switches, solder joints, Housing coatings, cathode ray tubes, rechargeable batteries | High exposures to cadmium can occur especially to people who live near e-waste sites or factories that release cadmium into the air. When cadmium is released into the environment and people breathe it, they stand a chance of having severe lung damage and this can lead to death. Cadmium do accumulates in kidneys and it damages its filtering mechanisms. Other health problems are Diarrhoea, stomach pains and severe vomiting, damage to the central nervous system and damage to the immune system. |

| Nonylphenol (NP) | Insulators, Housing, Casing | The toxicity of NP is said to be low in humans. However, NP is highly irritating and corrosive to the skin and eye. In terms of the environment, NP is highly toxic to fish, aquatic invertebrates, and aquatic plants. |

2. Study area and methods

2.1. Study area

The study area lies between latitude 5° 33′ 44″ and 5° 33′, 17″ North and longitude 0° 13′ 10″ and 0° 13′.48″ West covering an area of 0.313km2. The physical environment of Agbogbloshie is characterized by roads, buildings, drains and polluted streams. There is no visible extensive vegetation cover as the area is built up with bare surfaces made of concrete and sand.

The area is multicultural with people from different backgrounds in Ghana and neighboring African countries such as Burkina Faso and Togo who do business there. Most of the workers live in informal structures made of kiosks, wooden structures and a few concrete buildings.

The economic life of the area thrives on business in terms of buying and selling of food items such as vegetables, grains, meat, fish, root and tuber crops. Two major food items sold there are onion and yam.

Medium scale industrial companies operating in the area include Pepsi Cola and Domond roofing sheet company. Small scale industrial activities undertaken in the area include manufacture of gas stoves used for commercial food vending, khebab grills, coal ports and spare parts meant for different local machines. Galaway a section of the area specializes in the manufacture of corn mills, bread mixing machines and manufacture of car parts. The recovery and recycling of electronic waste is a major activity in the area which has attracted much attention.

2.2. Methods

Primary data was obtained through administering of open and close ended questionnaires to 180 respondents. Out of the 180 respondents, 120 of them are regular workers who work at specific spots. They are termed spot workers because they do not have defined land parcels on which they work neither do they have shops as they work in open spaces and temporary shelters meant to protect them from rainfall and the sun.

Simple random sampling method was used to select 120 respondents for interview categorized as recyclers and re-furbishers of e-waste. The first respondent out of the 120 interviewed was selected at random and thereafter every other second person at a spot was interviewed. Accidental sampling method was used to select 60 respondents who do not have spots on which they work but visit the site to deliver e-waste items for sale and leave the next moment. Such respondents have engaged in the collection and recycling of e-waste for the past 10 years. Major questions focused on background of respondents, technologies used for waste management, and effects of e-waste on people's health and the physical environment. In addition to the questionnaire survey, an official each of the Environmental Protection Agency, Scrap Dealers Association and Accra Metropolitan Assembly were interviewed on issues of effects of e-waste on the health of people and the environment, government policies on e-waste management and prevailing technologies.

Field observations were done to understand procedures at the site to help explain the study results. Data analysis was done using the Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS) and results presented in tables and figures. There was no test of hypothesis as preposition were stated instead of hypothesis.

This study was approved by the ethical committee of Wisconsin International University College (see Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Map of study area.

3. Results

3.1. Background of e-waste workers

The dismantling and recycling of electronic waste at Agbogbloshie is dominated by people with no formal education as study results show 65% of the respondents have never been to school. Few of them (20%) have studied up to the Junior High School level and 10% had primary school education (Figure 2). Only 5% of the respondents have Senior High School education qualifications. The high illiterate working population exist because the work does not require any skilled training or education to function in this business.

Figure 2.

Educational Level of Respondents. Source: Field data.

Study results show majority of the e-waste workers are not only uneducated but also very youthful as 48.3% of the respondents belong to the age bracket of (26–35) years and 38.3% are (15–25) years of age (Figure 3). Those below 15 years constitute 11.7%. These youthful population are able to endure the collection, sorting and recycling of waste because of their energy levels as much physical energy is required for the work.

Figure 3.

Ages of e-waste workers. Source: Field data.

3.2. Transport and types of e-waste

Transporting e-waste to Agbogbloshie starts with door to door collection of waste from homes and offices as scrap dealers walk through the city of Accra using routes such as Madina through, Adenta and Ashaley-Botwe. E-waste collectors usually bargain the fees they pay to owners of the waste they collect. Collection of e-waste is done with the aid of hand driven carriages that are pushed around. These carriages are either owned by those using them or hired by paying daily user fees. After the waste is collected, it is either sold to scrap dealers at Agbogbloshie or sold to middlemen.

There is no formal specialization regarding the types of e-waste collected as majority of the e-waste collectors, thus, 70% of them collect all types of e-waste. Five percent (5%) pick household appliances such as fridges and microwaves only while 5% collect only Information Technology (IT) and telecommunication equipment (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Types of waste collected. Source: Field data.

3.3. E-waste dismantling and recycling technologies

The dismantling of electronic waste at the study site for many years has been characterized by the use of crude technologies that result in physical injury to workers (Figure 5). All respondents 100% use their bare hands to sort e-waste, burn and retrieve valuable items from electronic waste. Dismantling electronic parts is done using stones, hammers and hitting waste items on the ground to get them crushed for the useful parts to be extracted for sale and for recycling. Major items recovered for recycling include copper, brass, iron and steel. The use of crude methods to handle e-waste was confirmed by officers interviewed from the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) and Accra Metropolitan Assembly (AMA).

Figure 5.

Technology used for recycling. Source: Field data.

Despite the risky nature of the waste, only few of the workers 38% use protective gloves, gears, nose covers and goggles. The few who wear protective gloves commented that they are uncomfortable wearing the gloves when hammering or chiseling electronic waste equipment hence prefer to work hands free. The view of Environmental Protection Agency is that, the use of crude methods has consequences for the people using them and the environment.

The workers at Agbogbloshie also believe that the easiest way to recover valuables from e-waste is to burn the waste regardless of the toxic smoke inhaled during the process. For the purposes of human and environmental safety however, cable stripping machines have been made to strip cables to check against burning but only 23% of respondents occasionally use it.

3.4. Refurbishing/reuse

Refurbishing of broken down electrical items is very common in Ghana as it is expensive buying new products. Recovered electronic parts from electronic waste dump sites such as mother boards, parts of cell phones, fridges and TV sets are valuable inputs for repair works. The Agbogbloshie e-waste site has become an important market for electronic spare parts. There are no designated spare part shops however, that sell electronic parts required to refurbish broken down equipment's as such it requires much effort looking around for spare parts.

3.5. Environmental and health effects of e-waste

Environmental and health consequences of e-waste management have been reported by (38%) of the respondents who identified soil contamination as a major environmental effect of unsustainable e-waste management. Air pollution was mentioned by (30%) of respondents and leakage of hazardous liquid chemicals such as acid contained in batteries of cars and other motor part fluids end up infiltrating the soil to make the soil heavily stained giving it a permanently dark colour Figure 6.

Figure 6.

Environmental and health effects of e-waste management. Source: Field data.

Physical injuries suffered while using crude implements include body cuts when cutting metals or stepping on metal chippings or pieces of metals lying on the ground as reported by 8% of the respondents. Other forms of injuries associated with the use of bear hands to dismantle e-waste occurs when hitting materials against each other to break them up or when stones and hammers are used to separate joined metals. Health problems arising out of the use of unsustainable e-waste management systems was reported by 24% of respondents.

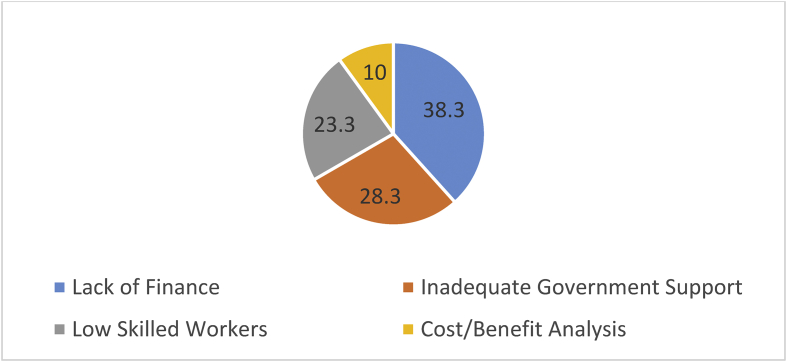

3.6. Factors limiting use of sustainable e-waste management technologies

Majority of the informal e-waste workers are of the view that capital to acquire new technology is a major challenge to the use of sustainable technologies as mentioned by 38.3% of them (Figure 7). Even though respondents wished they could acquire clean technologies to retrieve valuable elements from electronic waste, they are limited by funds as income earned from sale of e-waste is only enough for subsistence but not to buy expensive machinery. The few people who use cable stripers are of the view that the stripers are expensive to buy not to mention high electricity charges that go with the use of the cable striper. To quote one of the workers “it is not that we don't like to have all the good technologies, but, the money to buy them is the problem, however, if we use these crude methods, we don't have to pay for the cost of any machine for that reason we make hundred percent profit’‘.

Figure 7.

Constraints to use of technology. Source: Field data.

The chairman of Agbogbloshie e-waste workers association, for example, mentioned that at their meetings modern tools are shown to them such as cable strippers, but only a few of their members can afford to buy them. A few of the respondents (10%) explained further that, cost and benefit analyses are done before decisions are made to go for modern technologies to manage electronic waste. Others consider possible assistance from government as an enabler that will help them acquire better tools for their work given that 28.3% of the respondents said the cost of tools are beyond their means. For this reason, they are okay with the crude methods and do not see the need to change technology.

Respondents believe that they contribute to keeping the city clean for that matter play an important role that deserve to be supported by government and development partners when they are trained and provided with tools for free. Thirty eight percent of respondents mentioned lack of finance as a source of limitation to the use of sustainable technologies.

4. Discussions

Electronic waste management at Agbogbloshie is handled by workers who are not educated or have minimal education and very youthful as they are mostly below the age of 45 years. The low level of education among e-waste workers may account for the seemingly unconcerned attitudes shown when polluting the atmosphere through burning of e-waste materials and contaminating the soil when engine oil and other chemicals are released from electronic parts into water bodies and onto the land. It is not only the biophysical environment that is polluted through such actions, but the health of workers is also affected. Providing some education to the youth who are responsible for the collection, recycling and refurbishment of electronic materials may improve the quality of the immediate environment at the waste site. Earlier studies by Oteng-Ababio and Amankwaa (2014) show a similar result as the mean age of e-waste workers was 21 years.

Transport of e-waste is done with hand held carriages as scrap dealers walk around to collect e-waste but hardly use vehicles as it is a more expensive means of transport. The use of manual labour to crash electronic gadgets cause workers to become fatigued regardless of the youthful energy they have and could do better using modern tools to recover copper wires, brass and ion when financial resources become available to them.

Use of unsustainable methods to recover valuable metals such as open burning of wires and breaking of Cathode Ray Tubes (CRT) has led to heavy pollution of the soil and air in Agbogbloshie (Williams et al., 2013). Previous studies reveal that workers who do not protect themselves at work get injured and pollute nearby water bodies (Caravanos et al., 2011). According to Prakash et al. (2010) and Amoyaw-Osei et al. (2011) the lagoon close to Agboglosie and river Odaw are heavily polluted to the extent that the fish stock in the water are being killed.

E-waste workers are not concerned about not wearing protective cloths such as overalls, eye glasses and gloves at work though it is adversely affecting their health. They are also comfortable with the burning of plastic covers on electronic products to extract valuable metals despite the fact that, they inhale pollutants into their systems during the process which affect their health. A respondent remarked that many informal e-waste workers are sick yet they were not aware of their health status until a health group came to the site to take their blood samples to test for infections and upper respiratory diseases before they became aware of diseases they have contracted. This finding confirms an earlier study by Asante et al. (2012) that Agbogbloshie e-waste site is made up of unhealthy workers. Although many of the workers look physically strong, there is a gradual breakdown of their immune system.

Even though most of the youth are comfortable using crude tools, some expressed interest to be trained to engage in sustainable e-waste management provided they will not be asked to pay for the training and tools. They believe that use of crude implements can deliver the same level of output as technologically based machines as such they are comfortable using the crude tools regardless of their safety. It would have been expected that the 20% Junior High school graduates who have studied some basic science and have some level of understanding of the poisonous chemicals contained in lead and cadmium would have been careful when using their bare hands but are rather careless. These deficiencies have compelled the Environmental Protection Agency to take a decision to build the capacity of e-waste workers to address environment, health and sustainable livelihood issues (UNEP, 2008). This capacity building will ensure proper e-waste dismantling for a safe environment (Heacock et al., 2016).

5. Conclusion

The study identified the processes and methods of collecting, transporting and recycling electronic waste as less efficient. These inefficient methods have consequences for the people and the physical environment. Sustainable technology is seen as a remedy for addressing poor e-waste management, but this can only be achieved when financial support is offered e-waste workers to cater for the high cost of acquiring and maintaining their tools. This support is necessary because of the high profit motive of workers who do not want to spend out of their earnings to buy tools and are also not concerned about the environment. Other challenges against the use of sustainable technologies for e-waste management include, lack of capacity building and unwillingness to use protective cloths at work due to the reported discomfort when working. E-waste workers have suggested government assistance in terms of training and provision of efficient tools for sustainable e-waste management.

Finally, the paper concludes that, integrating sustainable technologies into management of electronic waste is the way forwards to keep the youth healthy in business and sustain their efforts to keep the city clean as they work to earn a living. For the youth to be effective in handling e-waste, modern ways of working such as use of the right tools and being conscious of the hazardous nature of materials they handle will make them cautious while working.

Declarations

Author contribution statement

Selase Kofi Adanu: Analyzed and interpreted the data; Contributed reagents, materials, analysis tools or data; Wrote the paper.

Shine Francis Gbedemah: Contributed reagents, materials, analysis tools or data; Wrote the paper.

Mawutor Komla Attah: Conceived and designed the experiments; Performed the experiments; Analyzed and interpreted the data; Contributed reagents, materials, analysis tools or data; Wrote the paper.

Funding statement

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interest statement

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Additional information

No additional information is available for this paper.

References

- Amuzu D. Environmental injustice of informal e-waste recycling in Agbogbloshie-Accra: urban political ecology perspective. Local Environ. 2018;23 1:1–16. [Google Scholar]

- Amoyaw-Osei Y., Agyekum O., Pwamang J., Mueller E., Fasko R., Schluep M. 2011. Ghana E-Waste Country Assessment, SBC E-Waste Africa Project, Accra, Ghana.http://www.basel.int/Portals/4/Basel%20Convention/docs/meetings/cop/cop9/b ali- declaration/BaliDeclaration.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Asante K.A., Agusa T., Biney C.A., Agyekum W.A., Bello M., Otsuka M., Itai T., Takahashi S., Tanabe S. Multi-trace element levels and arsenic speciation in urine of e-waste recycling workers from Agbogbloshie, Accra in Ghana. Sci. Total Environ. 2012;424:63–73. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2012.02.072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Badoni P.D. 2017. E-waste Management in India.http://www://electronicsforu.com [Google Scholar]

- Basel Convention Controlling transboundary movements of hazardous wastes and their disposal. 1989. www.basel.int?/tabid=2334 [PubMed]

- Borthakur A., Govind M. Management of the challenges of electronic waste in India: an analysis. Waste and Resource Management. 2018;171 1:1–23. [Google Scholar]

- Caravanos J., Clark E., Fuller R., Lambertson C. Assessing worker and environmental chemical exposure risks at an e-waste recycling and disposal site in Accra, Ghana. J. Health Pollut. 2011;1:16–25. [Google Scholar]

- Chatterjee S. Sustainable electronic waste management and recycling processes. Am. J. Environ. Eng. 2012;2(1):23–33. [Google Scholar]

- Esenduran G., Atasu A., Wassenhove L.N. Valuable e-waste: implications for extended producer responsibility. IISE Transactions. 2019;51(4):382–396. [Google Scholar]

- European Commission . Science for Environment Policy, DG, Environmental News Alert; April, 2010. E-waste in Developing Countries Needs Careful Management. [Google Scholar]

- European Union . 2002. Being wise with Waste: the EU’s Approach to Waste Management.http://www.ec.europa.eu/environment/waste/pdf/WASTE [Google Scholar]

- EU-WEEE . 2003. Directive 2003/108/EC of the European Parliament and the council of 8 December 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Finlay A. Association for progressive communications; 2005. E-waste Challenges in Developing Countries: South African Case Study, ACP Issue Papers; pp. 1–22. [Google Scholar]

- Gaidajis G., Angelakoglou K., Aktsoglou D. E-Waste: environmental problems and current management. J. Eng. Sci. Technol. Rev. 2010;3(1):193–199. [Google Scholar]

- GSMA Latin America . 2015. La Vision Magazine 2015 - 2016 Edition.http://gsma.com/latinamerica/resources/vision magazine-2016 [Google Scholar]

- Heacock M., Kelly C.B., Asante K.A., Birnbaum L.S., Bergman Å.L., Bruné M.N., Buka I., Carpenter D.O., Chen A., Huo X., Kamel M., Landrigan P.J., Magalini F., Diaz-Barriga F., Neira M., Omar M., Pascale A., Ruchirawat M., Sly L., Sly P.D., Van den Berg M., Suk W.A. E-waste and harm to vulnerable populations: a growing global problem. Environ. Health Perspect. 2016 doi: 10.1289/ehp.1509699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang J., Nkrumah P.T., Anim D.O., Mensah E. E-waste disposal effects on the aquatic environment: Accra, Ghana. Rev. Environ. Contam. Toxicol. 2014;19 229:19–34. doi: 10.1007/978-3-319-03777-6_2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luther L. Diane Publishing Co.; 2009. Managing Electronic Waste: Issues with Exporting E-Waste. Rongressional Research Service. [Google Scholar]

- Lundgren K. International Labour Organization; Geneva: 2012. The Global Impact of E-Waste: Addresssing the challenge. [Google Scholar]

- Maria-Grazia G. 2016. E-waste Management as a Global Challenge, Introductory Chapter, E-Waste in Transition from Pollution to Resource. [Google Scholar]

- Otieno I., Omwenga E. 2016. E-waste Management in Kenya: Challenges and Opportunities.https://www.google.com/search?q=Otieno%2C+I.%2C+and+Omwenga%2C+E.%2C+2016%2C+E-Waste+Management+in+Kenya%3A+Challenges+and+Opportunities&ie=utf-8&oe=utf-8&client=firefox-b-ab [Google Scholar]

- Oteng-Ababio M. The legal and the reasonable: exploring the dynamics of e-waste disposal strategies in Ghanaian households. J. US China Publ. Adm. 2012;9 1:38–52. [Google Scholar]

- Oteng-Ababio M., Amankwaa E.F. The E-waste conundrum: balancing evidence from the North and on-the-ground developing countries’ realities for improved management. African Review of Economics and Finance. 2014;6 1:181–204. [Google Scholar]

- Prakash S., Manhart A., Amoyaw-Osei Y., Agyekum O. 2010. Socio-economic Assessment and Feasibility Study on Sustainable E-Waste Management in Accra, Ghana.http://www.oeko.de/oekodoc/1057/2010-105-en.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Quaye W., Akon-Yamga G., Asante A., Daniels C. 2019. The E-Waste Management System in Ghana through the Transformative Innovation Policy Lens.http://www.tipconsortium.net/the-e-waste-management-system-in-ghana-through-the-transformative-innovation-policy-lens/ [Google Scholar]

- Shaw R.D. 2016. The challenge of E-Waste Management in Developing Countries.https://www.google.com/search?q=Shaw%2C+R.D.%2C+2016%2C+The+Challenge+of+E-Waste+Management+in+Developing+Countries&ie=utf-8&oe=utf-8&client=firefox-b-ab [Google Scholar]

- Sinha-Khetriwal D., Kraeuchi P., Schawninger M. A comparison of electronic waste recycling in Switzerland and in India. Environ. Impact Assess. Rev. 2005;25 5:492–504. [Google Scholar]

- Tetteh R. 2018. Lets Clean Ghana.https://www.graphic.com.gh/features/opinions (accessed November 2018) [Google Scholar]

- United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP) elsewhere forecast; India: 2010. Urgent Need to Prepare Developing Countries for Surge in E-Wastes. Rocketing Sales of Cell Phones, Gadgets, Appliances in China.http://www.unep.org/Documents.Multilingual/Default.Print.asp?DocumentID=612&ArticleID=6471 [Google Scholar]

- United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP) 2008. Bali Declaration on Waste Management for Human Health and Livelihood. Ninth Meeting of the Conference of the Parties to the Basel Convention on the Control of Trans-boundary Movements of Hazardous Wastes and Their Disposal, 23–27 June 2008, Bali, Indonesia. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations University,/Step . 2014. The Global E-Waste Monitor, Quantities, Flows and Resources.i.unu.edu/media/unu.edu/news/52624 [Google Scholar]

- United Nations Environment Programme . 2007. E-waste Volume II, E-Waste Management Manual.www.unep.org.jp/ietc/Publications/spc/Ewastemanual (accessed October 2018) [Google Scholar]

- WEEE . 2015. Peru. http:race-peru.pe. [Google Scholar]

- Williams E., Kahhat R., Bengtsson M., Hayashi S., Hotta Y., Totoki Y. Linking informal and formal electronics recycling via an interface organization. Challenges. 2013;4:136–153. [Google Scholar]

- Widmer R., Oswald-Krapf H., Sinha-Khetriwal D., Schnellmann M., Boni H. Global perspectives on e-waste. Environ. Impact Assess. Rev. 2005;25:436–458. [Google Scholar]

- World Resources Forum . 2019. Introduction of Sustainable E-Waste Management in Ghana: an Innovative Cooperation between MESTI, EPA and GIZ Supported by the German Government.https://www.wrforum.org/world-resources-forum-2019/workshops/sustainable-e-waste-management-in-ghana/www.pureearth.org [Google Scholar]

- Zafar S. 2016. Significance of E-Waste Management, Echoing Sustainability in MENA.https://www.ecomena.org/ewaste-management/EcoMENA [Google Scholar]