Abstract

Background

Doctors commonly continue to work when they are unwell. This norm is increasingly problematic during the COVID-19 (SARS-CoV-2) pandemic when effective infection control measures are of paramount importance. This study investigates the barriers existing before COVID-19 that prevent junior doctors with an acute respiratory illness working in Canberra, Australia, from taking sick leave, and offers suggestions about how to make sick leave more accessible for junior doctors.

Methods

Anonymous online survey study.

Results

192 junior doctors were invited to participate in the study. Fifty-four responded, and only those who had worked whilst unwell with an acute respiratory illness were included, providing a total number of fifty responses. Of these, 72% believed they were infectious at the time they worked whilst unwell. 86% of respondents did not feel supported by the workplace to take sick leave when they were unwell, and 96% identified concerns about burdening colleagues with extra workload and lack of available cover as the main deterrents to accessing sick leave.

Conclusion

Junior doctors at our health service, pre-COVID-19, do not widely feel empowered to take sick leave when they have an acute respiratory illness. Junior doctors are primarily concerned about burdening their colleagues with extra workloads in an environment where they perceive there to be a lack of available cover. Having more available cover, leadership from seniors, and clearer guidelines around the impact of sick leave on registration may contribute to a culture where junior doctors feel supported to access sick leave.

Keywords: COVID-19, Hospital-acquired infection, Junior doctor health, Junior doctor wellbeing, Nosocomial spread, Sick leave availability

Highlights

-

•

Results capture junior doctors' sick leave behaviours before COVID-19.

-

•

86% of junior doctor respondents did not feel supported to take sick leave.

-

•

72% of the doctors who reported working whilst unwell believed they were infectious.

-

•

Doctors were concerned about inadequate cover and burdening colleagues with work.

-

•

Cultural and practical changes may improve sick leave accessibility for junior doctors.

Introduction

It has been widely observed that doctors are likely to continue working when they are unwell [[1], [2], [3], [4], [5], [6], [7], [8], [9], [10]], with the literature indicating that between 51% and 86% of doctors continue to work when they are sick [[1], [2], [3], [4], [5], [6], [7], [8], [9]], a rate higher than that seen amongst most other groups [1,4,9,10]. In the current COVID-19 (SARS-CoV-2) pandemic the implications of working whilst unwell have been highlighted more dramatically than ever [[11], [12], [13], [14]], and the need to address and resolve this existing norm amongst medical professionals is increasingly urgent. Doctors working when they are sick, also known as presenteeism, poses a potential infection risk to patients and colleagues [2,7,15,16] and compromises the robust infection control measures that are needed to prevent the spread of nosocomial infections, such as COVID-19 [12,17,18] and influenza [15]. There have been numerous documented cases of intra-hospital spread of COVID-19 from healthcare workers both in Australia and overseas [11,13,14], including in Tasmania where COVID-19 spread in a medical ward after some staff worked whilst symptomatic [13]. Data from the NHS indicating that up to 20% of hospital COVID-19 positive patients contracted the virus during their time in hospital further highlights the importance of healthcare workers taking sick leave when they are unwell [11]. In addition to the risk of spreading infection, not taking appropriate sick leave may worsen the health and wellbeing of doctors, and perpetuates a longstanding cultural norm of working through illness [4,5,8,19].

In a landscape where it is imperative that doctors do not work when they are sick, understanding the complex cultural and organisational barriers that deter doctors from taking sick leave is of the utmost importance. Multiple reasons for presenteeism have been identified in the pre-COVID-19 literature through survey, questionnaire and interview studies engaging directly with doctors at varying levels in their career [[1], [2], [3], [4], [5], [6], [7], [8], [9], [10],20]. Concern about burdening colleagues with an increased workload [[1], [2], [3],5,10] and a sense of duty to patients [2,3,5,10] are consistently expressed as prominent obstacles to taking sick leave amongst doctors. In a survey study of New Zealand doctors by Tan et al., in which 82% reported presenteeism in the preceding 12 months, 71% of doctors identified “not wanting to burden co-workers” as a reason they did not take sick leave [2]. Even more dramatically, in a survey study of attending physicians by Szymczak et al., 98.5% of doctor respondents reported not wanting to let down colleagues as a reason they worked whilst sick [5]. Additionally, broader cultural and social norms - such as an expectation that doctors are healthy and hardworking, and a commitment to caring for patients - widely promote presenteeism amongst this cohort [[2], [3], [4], [5],10,19,21]. Collectively these findings contribute to the poor self-care and health behaviours commonly exhibited by doctors [6,8,9,21].

Survey studies into sick leave behaviours of junior doctors in New South Wales (NSW) have been conducted in recent years, which provide useful insights into the sick leave behaviours of this cohort. In the Australian Medical Association NSW Hospital Health Check survey of 1958 junior doctors in 2019, 62% “rarely” or “never” took sick leave when unwell [22]. 77% were deterred from taking sick leave due to “concerns about increasing workload for other team members”, and 62% because of “no sick reliever” [22]. Similar results were demonstrated in the NSW Health Junior Medical Officer Survey in 2018 [23], with “nil cover, impact on rest of team/colleagues” and “nil cover if not there” being identified as the two largest deterrents to junior doctors taking sick leave, at 76% and 54% respectively [23]. While these large studies provide valuable information on the accessibility of sick leave amongst the NSW junior doctor cohort, they do not include other Australian states and territories, and as such it is difficult to ascertain whether these patterns are limited to NSW or reflect a wider norm. Furthermore, these studies related to sickness in general, rather than to respiratory illness specifically.

There are other studies that exist which do include doctors nationwide, however these also do not focus on respiratory illness and do not specifically investigate the barriers that exist to taking sick leave exist. These include the 2008 Australian Medical Association survey study into Junior Doctor Health and Wellbeing in Australia and New Zealand, which found that 22.3% of males and 10.2% of females had never taken any personal leave for their own health [21], and the MABEL study, a survey which asks a large number of Australian doctors at different points in their career about sick leave behaviours and accessibility, but does not ask them to identify factors that deter them from taking sick leave [24].

The aim of this study was to identify what barriers existed to prevent junior doctors working in the Australian Capital Territory (ACT) and experiencing acute respiratory symptoms from taking sick leave. This study was conducted in November 2019 before COVID-19, and as such provides a valuable snapshot of the pre-COVID-19 attitudes, behaviors and cultural norms that led to junior doctors working when unwell with an acute respiratory illness in the ACT. Identifying and subsequently addressing these obstacles is imperative in improving the health of doctors, patients and healthcare organisations, and is of heightened importance now when the obstacles to taking sick leave must be dismantled to prevent the nosocomial spread of COVID-19.

Methods

We conducted a survey study to investigate the barriers that prevented junior doctors with symptoms of an acute respiratory illness from taking sick leave while employed at Canberra Health Services in Australia. All junior (postgraduate year 1 and postgraduate year 2) doctors employed in this health service were invited to complete a ten question, anonymous, online survey hosted on Survey Monkey (https://www.surveymonkey.com/r/LBDTVQ3). An anonymous link to this survey was sent to each doctors' staff email, and posted on the Facebook group page for the intern (postgraduate year 1) cohort. Additionally, an announcement inviting doctors to participate in the study was made at intern teaching. The survey link remained open for two weeks in November 2019 and could be completed any time during this period.

Informed consent was obtained in the first questions of the online survey (see appendix 1). The survey then asked participants whether they had come to work with an acute respiratory illness in the last two years, before asking various questions about their illness. Only respondents who answered “yes” to the first question were included in the study. In order to investigate the experiences of these respondents who had not taken sick leave when unwell with acute respiratory symptoms, participants were asked if they felt supported by their workplace to take sick leave, and asked to identify factors that deterred them from taking sick leave. One of the questions allowed for multiple responses to enable the selection of multiple relevant barriers to taking appropriate sick leave, and another question only allowed for a single response to identify which factor respondents perceived as the most significant. The response options offered were based on the literature cited in this study and empirical insights into potential barriers to taking sick leave that may exist. The final question asked participants to suggest a cultural or organisational change that would improve the accessibility of sick leave and allowed for a free text response. Key words that were repeated in the free text responses were used to capture emerging qualitative themes, and responses were then organised into these themes (see Table 2 ). The STROBE checklist for cross-sectional studies was used in writing up this report [25].

Table 2.

Qualitative analysis of free text response, by theme.

| Theme | Words associated with this theme | No. of responses including these words | Examples of free text response |

|---|---|---|---|

| Concerns about inadequate cover | Cover, redundancy, staffing, floaters, supernumerary | 38 | “Increased availability of JMO cover for sick leave” “Have a dedicated sick cover doctor, who would be a float on the ward if no one was sick, rather than people having to work double shifts to cover sick leave.” “Often does not have anyone to cover which makes me really reluctant to call in sick as it will burden my team mates.” |

| Concerns about registration requirements | Registration, finish, AHPRA | 9 | “Sick leave with a medical certificate should not impact on eligibility for medical registration unless it is for an extended period” “Start internship earlier in the year. ACT health has one of the latest starting dates. This adds extra pressure for anyone who might need to finish internship early if they wish to work in a different state.” “We work long hours and yet those are not counted towards meeting the registration requirements … when you take a sick day you are automatically penalised.” |

| Lack of leadership from senior staff | Senior, supportive | 4 | “Senior colleagues (registrars) being more supportive of junior staff being unwell.” “Seeing more senior doctors modelling good behaviour (ie. staying home when sick)” |

| Unclear process | Process, guidelines | 4 | “Making the process for applying for sick leave more streamlined, and making it a hospital issue if there is no one to cover” “Unclear about the process for calling in sick, particularly on weekends” |

| Other | Guilt, staff awareness, duty of care | 3 | “As a junior doctor always working in understaffed environments the professional guilt of not working is strong.” “More of an emphasis on duty of care to patients” “Better support from admin staff” |

Ethics approval was obtained through the ACT Health Human Research Ethics Committee, 2019/ETH13251.

Results

Of the 192 doctors invited to participate there were 54 responses, equating to a response rate of 28%. Four of these responses were excluded as the doctors had indicated that they did not come to work when unwell, and thus they did not meet the inclusion criteria. As such the final response rate was 26% (fifty participants).

In Australia, intern doctors (PGY1) are required to rotate through different departments in order to meet requirements for general registration. Junior doctors in their second year (PGY2) in Australia largely continue to rotate through departments before beginning specialty training.

At the time they reported being unwell, 27 (54%) of the junior doctor respondents were working in Medicine, 30 (15%) in Surgery, 4 (2%) in Critical Care and 12 (6%) in Womens' or Childrens' units (see Table 1). One third of respondents (32%) reported a fever at the time of illness and the majority of participants (72%) believed they were infectious when working while unwell.

Table 1.

Summary of results.

| N | % | |

|---|---|---|

| Area of Work | ||

| Medicine | 27 | 54 |

| Surgery | 15 | 30 |

| Critical Care | 2 | 4 |

| Womens/Childrens | 6 | 12 |

| Fever at the time | ||

| Yes | 16 | 32 |

| No | 34 | 68 |

| Perceived as infective | ||

| Yes | 36 | 72 |

| No | 14 | 28 |

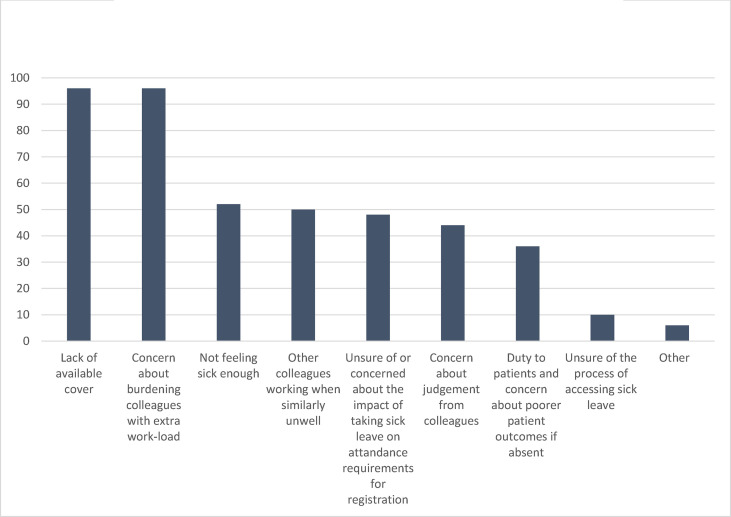

The majority of respondents (86%) indicated that they did not feel supported to take sick leave when unwell. When asked to select reasons that deterred them from taking sick leave and multiple responses were allowed, 96% of respondents were concerned about burdening their colleagues with extra work-load and 96% about a lack of available cover (see Fig. 1 ). Not feeling sick enough to take leave and seeing other colleagues working when similarly unwell were also commonly selected factors, at 52% and 50% respectively. Nearly half (48%) of the doctors were unsure of or concerned about the impact that taking sick leave could have on their registration requirements, and 10% were unsure about how to access sick leave. 44% were concerned about judgement from colleagues, and 36% were deterred by a sense of duty towards their patients and a concern that patient outcomes would be poorer in their absence.

Fig. 1.

Reasons that deterred junior doctors from taking sick leave (%, multiple responses allowed).

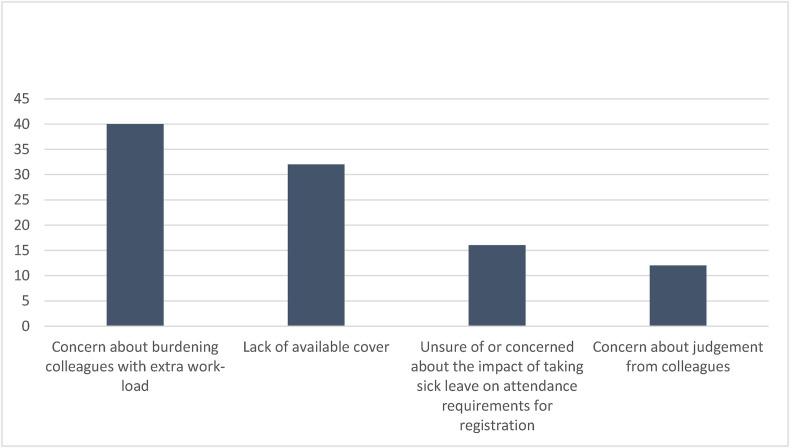

When participants were only allowed to identify one factor as the single biggest deterrent to taking sick leave, concern about burdening colleagues with extra work and no available cover were the two most prominent reasons selected, at 40% and 32% respectively (see Fig. 2 ), followed by concerns about registration requirements (16%) and judgement from colleagues (12%).

Fig. 2.

Biggest single factor deterring junior doctors from taking sick leave (%).

All but one of the participants provided a free text response about what cultural or organisational changes might make sick leave more accessible (see Table 2). More available cover was suggested by 76% (38) of respondents, making it overwhelmingly the biggest emerging theme (see Table 2). Numerous junior doctors were worried that lack of cover meant that if they took sick leave it would burden their teammates, who they felt were already working in understaffed environments with high workloads. In addition to reporting that cover was often not available (particularly for night shifts and in rural secondments), respondents expressed concerns about how cover was organised, noting that the system for arranging cover was inconsistent between hospitals and difficult to organise out of hours. Notably, junior doctors were concerned that if they were sick it often meant that the colleague who was called to cover them would work double shifts and more overall hours, making them vulnerable to also becoming unwell. Suggestions were made for more streamlined systems between hospitals and capacities to draw on staff from both hospitals within the health service to provide sick cover at either site, more junior doctors as designated floaters and sick cover on teams, built in redundancies in specific teams and departments, and a 24/7 administrative contact to arrange cover out of hours and to allow sick cover to start on time (see Table 2).

In Australia interns (PGY1) are required to undertake 10 weeks of surgery, 10 weeks of medicine, 8 weeks of emergency medicine and a combination of other approved terms to make up a total of 47 weeks full time equivalent before being granted general registration [14]. Nine junior doctors expressed concern about registration requirements and suggested clearer guidelines about how much sick leave can be taken without it affecting registration. Junior doctors also expressed frustration that they work many hours in overtime and out of hours shifts that do not count towards registration, and that the weekly roster exceeds full time equivalent, but that this additional time does not always count to compensate for the absence of any sick leave taken when calculating registration requirements.

Four respondents recommended more leadership from senior staff, including senior doctors staying home when unwell to set a cultural example, and sending home junior staff when they are sick.

Other contributions included suggestions for clearer guidelines about how to access sick leave including when on call, more emphasis on duty of care to patients and the potential harms they can incur by doctors treating them whilst unwell, and more support from an administrative level. Finally, one respondent advocated for a greater sense of hospital, rather than personal, accountability for staffing issues, suggesting that this would be helpful in alleviating the guilt junior doctors feel for understaffing when they are required to take sick leave.

Discussion

These results indicate that the predominant factor deterring junior doctors from taking sick leave is concern about burdening their colleagues with increased workloads. This is reflective of their experience that there is not adequate sick cover in place, that the workplace is understaffed, and that junior doctors already have high workloads. These findings are consistent with the sentiment broadly emerging across the literature that doctors' concern towards burdening their colleagues makes them reluctant to take sick leave [[1], [2], [3],5,10], and ultimately suggest that inadequate staffing and cover in hospital systems strengthens a culture where taking sick leave is perceived as being unsupported and problematic.

That 86% of the doctors who worked when unwell in our study did not feel supported to take sick leave is concerning. In their cross-sectional study of 70 junior doctors Fitzpatrick et al. found that those who did not perceive their hospital to promote their wellbeing were nearly nine times more likely to be emotionally exhausted [26]. Furthermore, they found that presenteeism made junior doctors more likely to experience emotional exhaustion [26]. Ensuring a positive organisational culture within hospitals where junior doctors feel valued and empowered to look after their own health is therefore important in protecting this cohort from emotional exhaustion, and is vital in combating the cultural norm evidenced in the literature that physicians often give little or poor attention to their own medical problems [4,8,21]. The fact that nearly half (44%) of junior doctors in our study felt concerned about judgement from their colleagues if they took sick leave is a significant reminder the “climate of stoicism” Baldwin observed in 1997 still permeates the medical culture today [8].

This “climate of stoicism” may provide some insight into why doctors may be especially more likely to work when they have an acute respiratory illness than when they have other illnesses, making the sick leave behaviours of doctors with respiratory illness particularly important. Of the 869 Norweigan physicians who reported working with an illness in Rosvold and Bjertness' 2001 study, over 60% of them had symptoms of influenza or a respiratory illness, making this the most common illness to work with [6]. Similarly, respiratory illnesses were the most common illness to work with in Szymczak's study, with 60% of the 280 attending physicians who worked while unwell listing their symptoms to be “acute onset of significant respiratory tract symptoms” [5]. In investigating why this is the case, Szymczak offers that there is a perception that doctors should continue working with a respiratory tract illness, with respondents in the study widely reporting an expectation to continue working with these symptoms [5]. Szymczak suggests that perhaps this is because respiratory illnesses are sometimes considered too mild to take leave for, occur more frequently, and can take multiple days to recover from [5]. This expectation is of course particularly problematic during the era of COVID-19, and attitudes towards working when unwell with respiratory symptoms may have now changed significantly.

Interestingly, while it is a dominant reason in the literature [2,3,5,10], a sense of duty to patients was not a common reason in this study for not taking sick leave, with no respondents selecting it as the single biggest deterrent to taking leave and 36% selecting it as a factor when multiple responses were allowed. This is perhaps due to the fact that this cohort were junior doctors, compared to senior doctors in other studies who may feel a higher degree of responsibility for patient outcomes. Unique to junior doctors were concerns about how absence due to illness may impact their ability to meet their registration requirements, with one in six selecting this as the biggest single reason to not take sick leave.

In their 2009 study on presenteeism – in which over 80% of physicians continued to work when they had a respiratory tract infection – Gudgeon et al. ominously warned that:

“further research is required to explore and address this issue, not only for common respiratory tract infections but to ensure that proper infection control practices are in place to prevent healthcare workers from acting as vectors – as happened in SARS – should another pandemic respiratory illness occur.” [7].

In the era of COVID-19 there is a unique opportunity to use the heightened awareness of the implications of working whilst unwell to change the culture around presenteeism and improve the accessibility of sick leave for doctors. It has already been shown that cultural change regarding the accessibility of sick leave is possible and beneficial. In their analysis of presenteeism among physicians in the Health and Organisation among University Physicians Europe study, Gustaffson et al. found that “organisational care for employee health and well-being reduced the frequency of sickness presenteeism in all countries [Sweden, Norway, Iceland and Italy]” [4]. Similarly, in their research exploring whether workplace conditions had become more conducive to junior doctors taking appropriate sick leave, Perkin et al. found that junior doctors were more than twice as likely to take sick leave in 2001 than in 1993, at 36.8% and 15.1% respectively [1]. The more flexible sick leave arrangements offered in the “fit notes” model in the United Kingdom- including graded and partial sick absences – have shown some benefits in other work sectors, and there may be scope to investigate whether similar models would improve the accessibility of sick leave in a junior doctor cohort [27]. Substantial efforts to improve junior doctor health and wellbeing are already underway in Australia. The 2017 NSW Health Junior Medical Officer (JMO) Wellbeing and Support Plan offers welcome initiatives that respond to concerns raised by junior doctors about their work, wellbeing, health and training [28]. The plan is robust and the initiatives are promising and important. However, while they acknowledge that “a lack of cover for when staff are on leave – resulting in staff not wanting to take sick leave, annual leave etc as they are concerned about the workload on their colleagues” as a key issue arising from the JMO wellbeing and support forum [28], no initiatives are offered to improve sick leave cover or the accessibility of sick leave in the plan [28]. Whilst the issue of inadequate cover and the inaccessibility of sick leave for junior doctors is being increasingly recognised, tangible changes at a systems level still need to be made to address this.

Suggestions from junior doctors in our study as to how to improve accessibility of sick leave commonly centre around the theme of improving the availability of cover so that individuals do not feel that they are burdening their colleagues by increasing their workload if absent (see Table 3 ). These include having more doctors as designated sick relief rather than requiring other doctors to work double shifts or having no cover, and shifting the sense of responsibility to cover shifts from the individual to the hospital organisation. This echoes suggestions made in the literature by Perkin et al. [1], Jena et al. [3], and Tan et al. [2] that providing more cover is fundamental in addressing sickness presenteeism in the medical workforce. Assuring doctors that they would be covered if unwell would create a more supportive culture and potentially position junior doctors to be less concerned about judgement from their colleagues if they are absent from work. Respondents in our study also suggested having clear and consistent policies pertaining to sick leave, something that is advocated for by Gustaffson et al. [4], Chow and Mermel [16], and Tan et al. [2]. In the case of junior doctors in Australia, details about the effects of sick leave on registration requirements would help empower doctors to utilise sick leave when it is necessary for them to do so. Baldwin [8], Chow and Mermel [16], and Gustaffson et al. [4] also argue that health services for junior doctors should be promoted, with Chow and Mermel suggesting that review by an “occupational health representative” when doctors are unsure about whether they are too sick to work would be useful [16]. This may improve the extent to which junior doctors perceive that their hospital organisation cares about their health and wellbeing, and thus, if we are to be guided by the compelling findings of Gustaffson et al. [4] and Fitzpatrick et al. [26], reduce their rates of presenteeism [4] and make them less vulnerable to experiencing emotional exhaustion [26].

Table 3.

Respondents' suggestions to address barriers to accessing sick leave.

| Theme | Suggestions |

|---|---|

| Concerns about inadequate cover |

|

| Concerns about registration requirements |

|

| Lack of leadership from seniors |

|

| Unclear process |

|

| Other |

|

We note several limitations to this study. Firstly, this study only examined the responses of doctors who did not take sick leave. Thus, the responses may be reflective of a sampling bias toward doctors who worked whilst unwell and does not communicate the views of doctors who did feel supported to access sick leave. The response rate of 26% may also reflect that this is a hard to reach group and may have been increased if reminders to complete the survey were sent. Reminders were not sent as this was not specified in the ethics application and thus specific ethics approval to send reminders was not granted. Furthermore, the survey design only allowed brief full text responses which found consistent themes but did not allow deeper interrogation of the structural and cultural reasons for attendance at work whilst unwell. Further studies using a semi-structured interview design would allow for a deeper qualitative analysis and would be valuable prior to any intervention to effect cultural change. Furthermore, interviewing hospital administrators on this issue could clarify whether there is a shared understanding between junior doctors and administrators around junior doctor sick leave behaviour. While these results reflect a certain moment within this particular cohort and health district, their wider application and relevance to other settings is not known. Finally, the survey was not piloted and did not use standadised questions.

We intend to repeat this survey study in 2021 and observe whether the same concerns for accessing sick leave still exist. Additionally, in this upcoming survey we plan to quantify how many junior doctors in the ACT took sick leave for an acute respiratory illness pre and post COVID-19, in order to observe whether organisational changes to sick leave and cover during COVID-19 have improved the rates at which junior doctors access sick leave. We intend to use the same survey in this future study, with modifications to allow for doctors who did take sick leave to have their responses included.

Informed consent

Participants were provided with written study information at the start of the online survey and provided their informed consent via the online survey before undertaking the survey.

Ethics

Ethics approval was obtained through the ACT Health Human Research Ethics Committee, 2019/ETH13251.

Authorship statement

Lucy Mitchell: Obtained ethics approval, Methodology, Investigation, Formal analysis, Writing - original draft, review and editing, Formatting, Project administration.

Nicholas Coatsworth: Conceptualization, Methodology, Investigation, Formal analysis, Writing – review and editing, Supervision, Project administration.

Conflict of interest

There are no competing interests or conflicts of interest declared in this study.

Funding

This study was not funded and was completed by two doctors working at The Canberra Hospital.

Provenance and peer review

Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Acknowledgments

We would like to acknowledge and thank Dr. Luke Streitberg and Dr. Michael Hall for their review and edits of this paper.

We are grateful for the insights, edits and suggestions offered by the reviewers at the Journal of Infection, Disease and Health.

Footnotes

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.idh.2020.07.005.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

The following is the Supplementary data to this article:

References

- 1.Perkin M.R., Higton A., Witcomb M. Do junior doctors take sick leave? Occup Environ Med. 2003;60(9):699–700. doi: 10.1136/oem.60.9.699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tan P.C.M., Robinson G., Jayathissa S., Weatherall M. Coming to work sick: a survey of hospital doctors in New Zealand. N Z Med J. 2014;127(1399) [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jena A.B., Meltzer D.O., Press V.G., Arora V.M. Why physicians work when sick. Arch Intern Med. 2012;172(14):1107–1108. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2012.1998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gustafsson Sendén M., Løvseth L., Schenck-Gustafsson K., Fridner A. What makes physicians go to work while sick: a comparative study of sickness presenteeism in four European countries (HOUPE) Swiss Med Wkly. 2013;143(3334) doi: 10.4414/smw.2013.13840. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Szymczak J.E., Smathers S., Hoegg C., Klieger S., Coffin S.E., Sammons J.S. Reasons why physicians and advanced practice clinicians work while sick: a mixed-methods analysis. JAMA Pediatr. 2015;169(9):815–821. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2015.0684. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rosvold E.O., Bjertness E. Physicians who do not take sick leave: hazardous heroes? Scand J Publ Health. 2001;29(1):71–75. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gudgeon P., Wells D., Baerlocher M., Detsky A. Do you come to work with a respiratory tract infection? Occup Environ Med. 2009;66(6):424. doi: 10.1136/oem.2008.043927. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Baldwin P., Dodd M., Wrate R. Young doctors' health—II. Health and health behaviour. Soc Sci Med. 1997;45(1):41–44. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(96)00307-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.McKevitt C., Morgan M., Dundas R., Holland W. Sickness absence and ‘working through’illness: a comparison of two professional groups. J Publ Health. 1997;19(3):295–300. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.pubmed.a024633. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Oxtoby K. Why doctors don't take sick leave. BMJ. 2015;351:h6719. doi: 10.1136/bmj.h6719. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Harding L., Campbell D. Up to 20% of hospital patients with Covid-19 caught it at hospital. Guardian. 2020 May 18:2020. [Google Scholar]

- 12.NSW Government and Clinical Excellence Commission. Infection prevention and control management of COVID-19 in healthcare settings.

- 13.ABC . ABC News; April 30, 2020. Hospital staff 'worked with coronavirus symptoms', Ruby Princess 'likely' cause of Tasmanian outbreak. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Boccia S., Ricciardi W., Ioannidis J.P.A. What other countries can learn from Italy during the COVID-19 pandemic. JAMA Int Med. 2020;180(7):927–928. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2020.1447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Parkash N., Beckingham W., Andersson P., Kelly P., Senanayake S., Coatsworth N. Hospital-acquired influenza in an Australian tertiary Centre 2017: a surveillance based study. BMC Pulm Med. 2019;19(1):79. doi: 10.1186/s12890-019-0842-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chow E.J., Mermel L.A. More than a cold: hospital-acquired respiratory viral infections, sick leave policy, and a need for culture change. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2018;39(7):861–862. doi: 10.1017/ice.2018.94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.WHO Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) situation report 29. 2020. https://www.who.int/docs/default-source/coronaviruse/situation-reports/20200218-sitrep-29-covid-19.pdf?sfvrsn=6262de9e_2 Updated Jan 31, 2020. Available from:

- 18.Centres for Disease Control and Prevention . Centre for Disease Control and Prevention; 2020. Interim infection prevention and control recommendations for healthcare personnel during the coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic.https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/hcp/infection-control-recommendations.html Updated July 9, 2020. Available from: [Google Scholar]

- 19.Whitelaw S. There's incredible pressure on doctors to keep working while they are sick. Article published online at March 9, 2020. https://www.smh.com.au/national/there-s-incredible-pressure-on-doctors-to-keep-working-while-they-are-sick-20200308-p547xx.html.

- 20.Aronsson G., Gustafsson K., Dallner M. Sick but yet at work. An empirical study of sickness presenteeism. J Epidemiol Community. 2000;54(7):502–509. doi: 10.1136/jech.54.7.502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Australian Medical Association . ACT: AMA; Barton: 2008. AMA survey report on junior doctor health and wellbeing. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Australian Medical Association NSW . 2019. Hospital health Check. [Google Scholar]

- 23.NSW Government . 2018. NSW health JMO survey. [Google Scholar]

- 24.MABEL . 2018. MABEL medicine in Australia: balancing employment and life, hospital doctor not enrolled in a specialty training program (interns and medical officers) [Google Scholar]

- 25.STROBE. STOBE Statement Checklist of items that should be included in reports of cross-sectional studies. https://www.strobe-statement.org/fileadmin/Strobe/uploads/checklists/STROBE_checklist_v4_cross-sectional.pdf Available from: [DOI] [PubMed]

- 26.Fitzpatrick M., Garsia K., Eyre K., Blackhall C.-A., Pit S. Emotional exhaustion among regional doctors in training and the application of international guidelines on sustainable employability management for organisations. Aust Health Rev. 2020;44:609–617. doi: 10.1071/AH19121. https://doi.org/10.1071/AH19121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sanderson KaC F. Presenteeism implications and health risks Australian. Fam Physician. 2013;42(4):172–175. April 2013. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.NSW Health . 2017. NSW health JMO wellbeing and support plan November. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.