Abstract

Background & Aims

Georgia, with a high prevalence of HCV infection, launched the world’s first national hepatitis C elimination program in April 2015. A key strategy is the identification, treatment, and cure of the estimated 150,000 HCV-infected people living in the country. We report on progress and key challenges from Georgia’s experience.

Methods

We constructed a care cascade by analyzing linked data from the national hepatitis C screening registry and treatment databases during 2015–2018. We assessed the impact of reflex hepatitis C core antigen (HCVcAg) testing on rates of viremia testing and treatment initiation (i.e. linkage to care).

Results

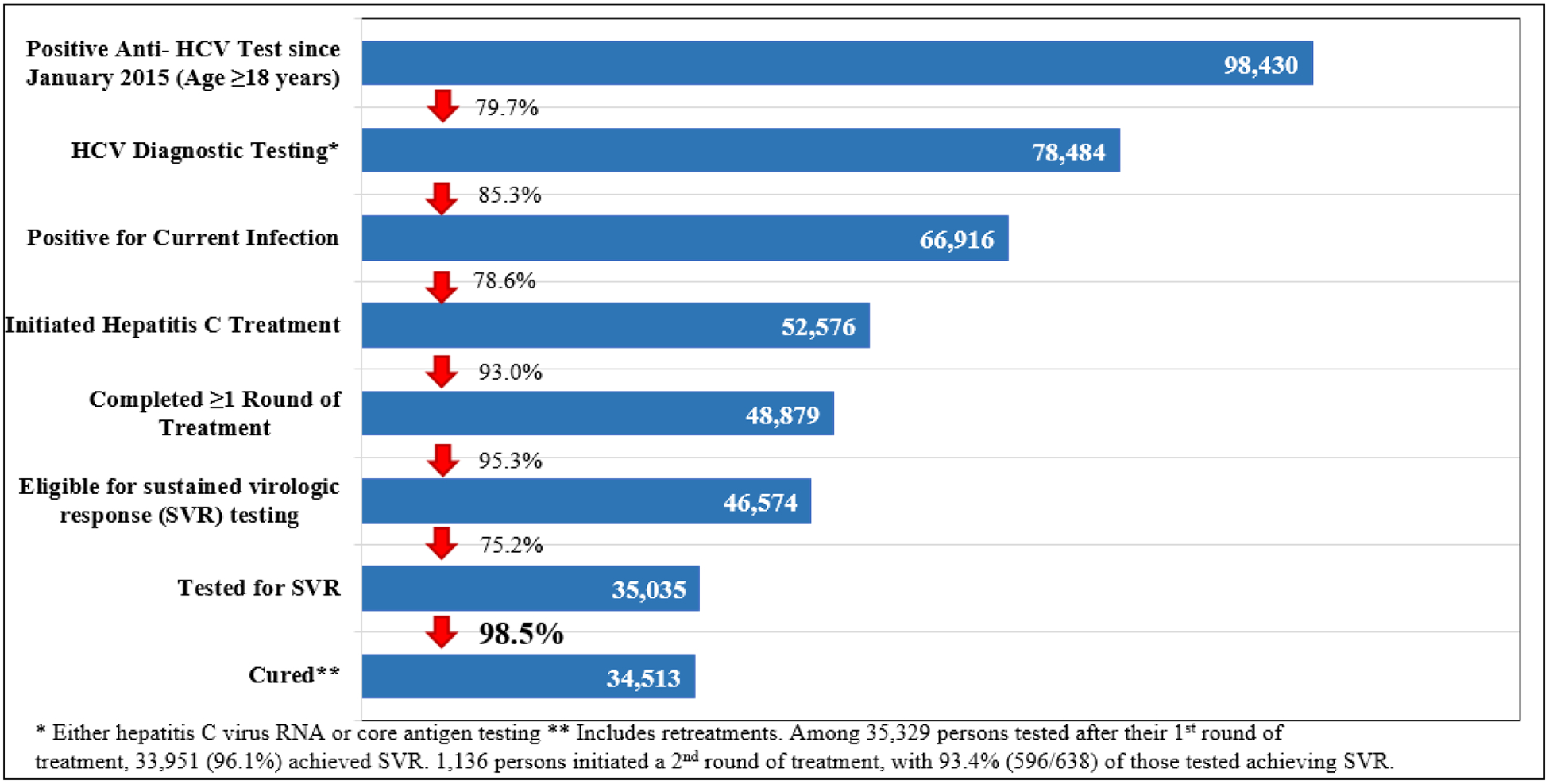

As of December 31, 2018, 1,101,530 adults (39.6% of the adult population) were screened for HCV antibody, of whom 98,430 (8.9%) tested positive. Of the individuals who tested positive, 78,484 (79.7%) received viremia testing, of whom 66,916 (85.3%) tested positive for active HCV infection. A total of 52,576 people with active HCV infection initiated treatment and 48,879 completed their course of treatment. Of the 35,035 who were tested for cure (i.e., sustained virologic response [SVR]), 34,513 (98.5%) achieved SVR. Reflex HCVcAg testing, implemented in March 2018, increased rates of monthly viremia testing by 97.5% among those who screened positive for anti-HCV, however, rates of treatment initiation decreased by 60.7% among diagnosed viremic patients.

Conclusions

Over one-third of people living with HCV in Georgia have been detected and linked to care and treatment, however, identification and linkage to care of the remaining individuals with HCV infection is challenging. Novel interventions, such as reflex testing with HCVcAg, can improve rates of viremia testing, but may result in unintended consequences, such as decreased rates of treatment initiation. Linked data systems allow for regular review of the care cascade, allowing for identification of deficiencies and development of corrective actions.

Keywords: Georgia, Hepatitis C, Hepatitis C diagnostic testing, Screening, Linkage to care

Lay summary:

This report describes progress inGeorgia’s hepatitis C elimination programand highlights efforts to promote hepatitis C virus screening and treatment initiation on a national scale. Georgia has made progress towards eliminating hepatitis C, treating over 50,000 people, approximately one-third of the number infected, and achieving cure for 98.5% of those tested. However, identifying infected individuals and linking them to care remains challenging. Novel approaches to increase diagnostic testing can have unintended consequences further down the care cascade.

Introduction:

Georgia, a small middle-income country with a population of 3.7 million, located at the cross-roads of Europe and Asia, launched the world’s first national hepatitis C elimination program in April 2015, with the ambitious goal of a 90% reduction in hepatitis C prevalence by 2020.1 At the time the program was initiated, a national seroprevalence survey was conducted that estimated 150,000 Georgians (5.4% of the adult population) were living with HCV infection.2 To achieve the elimination goal, Georgia implemented several strategies, including the identification and treatment of all HCV-infected people in the country.3 The feasibility of this strategic goal was made possible by an April 2015 memorandum of understanding (MOU) between the government of Georgia and Gilead Sciences, in which Gilead Sciences agreed to provide direct-acting antiviral (DAA) medications free-of-charge for eligible Georgians with HCV infection.3,4 The cost of DAAs in 2015 was prohibitive; without the MOU with Gilead Sciences this program could not have transpired. A large number of Georgians enrolled in the program during the first 3 years, and cure rates exceeded 95% among those treated and tested for cure (i.e., sustained virologic response [SVR]).5 Yet, despite the availability of treatment and high cure rates, important challenges remain. We report on progress, key challenges, and lessons learned from Georgia’s experience in identifying persons with HCV infection and linking them to hepatitis C care and treatment.

Patients and Methods:

Georgia’s Hepatitis C Elimination Program

Georgia’s hepatitis C elimination program provides hepatitis C testing free-of-charge in a variety of settings (Table 1). Initial screening is conducted using a rapid HCV antibody (anti-HCV) assay that tests for past or present HCV infection; people who screen positive on the antibody test are then referred to authorized treatment sites for diagnosis of active HCV infection by testing for HCV RNA using PCR, before being notified of their results and enrolled for treatment if they test positive for HCV RNA. To increase access by identifying and linking HCV-infected persons to care, in December 2017, HCV core antigen (HCVcAg) testing was introduced in a limited number of settings, and expanded in March 2018 when the program implemented reflex HCVcAg for all anti-HCV positive patients screened in hospitals, antenatal clinics, and blood banks. Each patient with a positive anti-HCV test during their visit had a serum sample obtained and shipped to the National Reference Laboratory (Lugar Center) in Tbilisi for centralized HCVcAg testing. HCVcAg has comparable sensitivity and specificity to HCV RNA testing for identifying active HCV infection.6 To minimize false-negative results, all specimens that tested negative or inconclusive by HCVcAg were subsequently tested for HCV RNA. National Centers for Disease Control and Public Health (NCDC) staff informed patients by telephone of the results of the diagnostic testing (HCVcAg or HCV RNA) and referred those that tested positive for treatment.

Table 1.

Number of adults aged ≥18 years screened for anti-HCV antibody and percentage testing positive, by group screened – Georgia, 2015–2018

| Group/Location of Screening | No. Adults (aged ≥18) Screened | % anti-HCV Positive |

|---|---|---|

| Blood donors | 112,926 | 3.0% |

| NCDC | 131,479 | 33.4% |

| Pregnant women/ANCs | 108,776 | 0.6% |

| Hospitalized patients | 468,479 | 4.7% |

| Harm-reduction beneficiaries | 10,886 | 30.6% |

| Outpatients | 612,452 | 5.0% |

| Prisoners | 7,008 | 24.3% |

| Military recruits | 19,759 | 1.5% |

| Persons living with HIV* | 3,889 | 39.5% |

Abbreviations: ANC = antenatal clinic; HCV = hepatitis C virus; HIV = human immunodeficiency virus; NCDC = National Centers for Disease Control and Public Health

Data through July 1, 2018

People confirmed to have active HCV infection by HCVcAg or HCV RNA testing are eligible to enroll in the treatment program.3,7 During the enrollment process, patients undergo additional diagnostic testing, including determination of HCV genotype, assessment of degree of liver fibrosis, and screening for comorbidities and contraindications to treatment. Patients found eligible for treatment based on results of the initial workup are prescribed a DAA treatment regimen according to national treatment guidelines8 and are followed during the course of their treatment. Within 12–24 weeks of completing treatment, patients are to return to the treatment site for HCV RNA testing to determine whether they had reached an SVR. Those with SVR are considered cured of their HCV infection. Initially, DAA treatment was exclusively sofosbuvir (SOF)-based and included ribavirin with or without pegylated interferon, depending on the HCV genotype, per national guidelines.4 Beginning in February 2016, the DAA combination sofosbuvir and ledipasvir (SOF/LED) was introduced, and treatment regimens were revised.4 For the first year of the program, treatment was limited to those with severe liver disease, defined as METAVIR score correlating to F3 or F4 (based on liver elastography), or FIB-4 score >3.25.1 In July 2016, the treatment program was expanded to include all people with HCV infection, regardless of level of liver fibrosis.

Although treatment is free for program enrollees, at the start of the program Georgians were required to pay for diagnostic testing, with prices determined by a sliding scale based on the patients’ ability to pay. Recognizing testing costs as a barrier to hepatitis C elimination, the government of Georgia reduced the number of tests required for each patient9 and beginning in March 2018, provided HCV RNA or HCVcAg testing free-of-charge to all Georgians.

Data Management and Analysis

Every Georgian citizen is provided a unique national identification number for accessing healthcare services, including those offered through the hepatitis C elimination program. Georgia developed information systems to collect data from the hepatitis C screening registry, laboratories, and the hepatitis C treatment program, all of which can be linked using each person’s unique national identification number. Although this number must be provided by all patients prior to enrolling in the treatment program, screening data from harm-reduction sites (including needle and syringe programs and opioid substitution therapy sites) are collected and reported anonymously to protect the privacy of clients. Beginning in 2017, harm-reduction sites began using the national identification number for consenting beneficiaries as well, allowing for analysis of data from these sites within the national hepatitis C elimination program.10

We analyzed national screening registry data from January 2015 through December 2018, as well as hepatitis C treatment data from April 2015 through December 2018, to assess the effectiveness of screening, linkage to care and treatment services, as well as outcomes (i.e. the care cascade). We calculated the percentage of people who screened positive for HCV antibody, and of those who were positive, we calculated the percentage who received diagnostic testing to determine active, viremic infection. Of those who tested positive for active HCV infection, the rates of treatment initiation, treatment completion, and testing for and achieving virologic cure (SVR) were assessed.

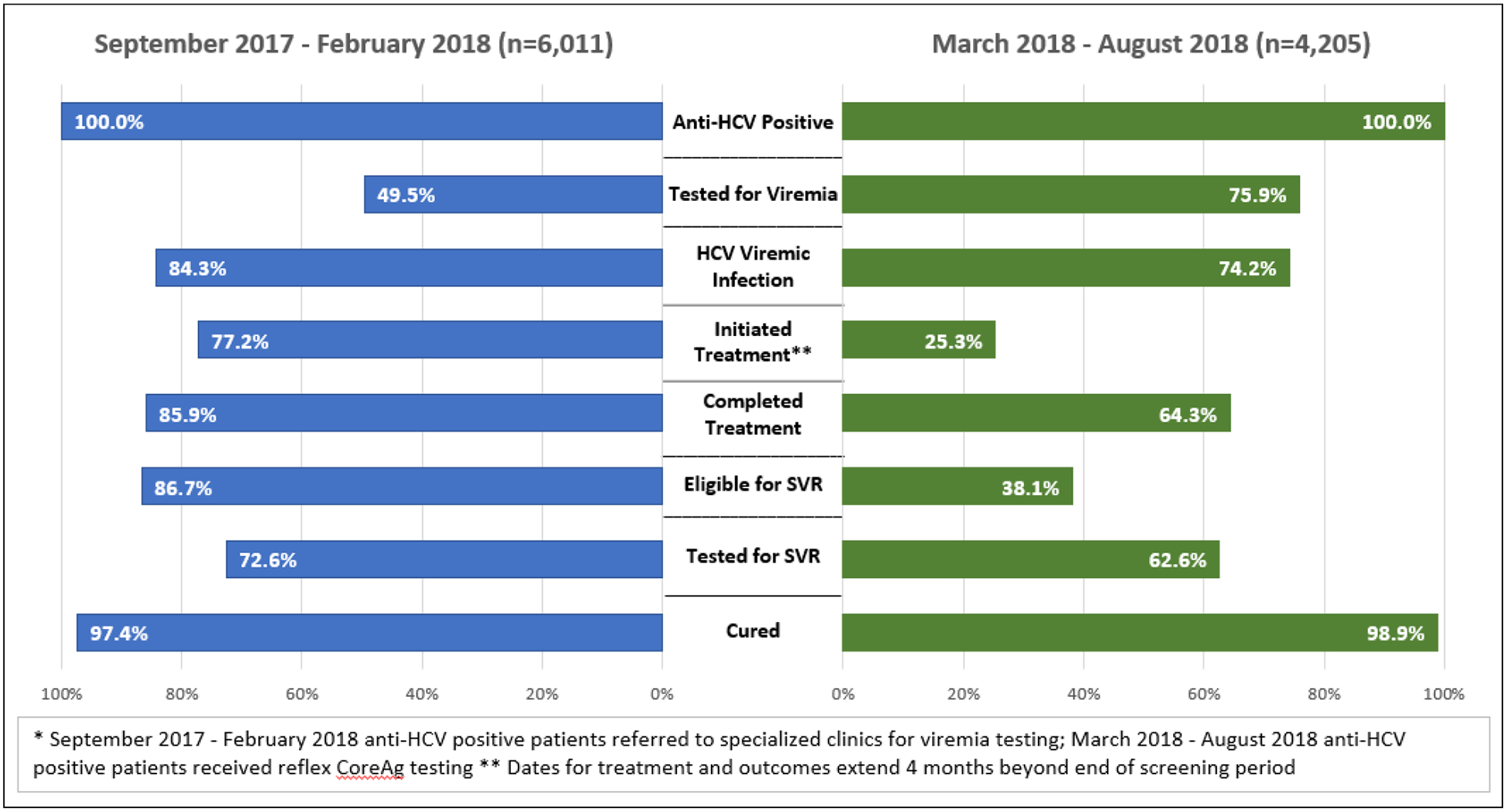

In order to better understand the effectiveness of HCVcAg reflex testing as a diagnostic tool for ensuring treatment initiation, we constructed 2 care cascades among hospitalized patients; one cascade included patients who screened positive for HCV antibody and were referred to a treatment center for diagnosis of active HCV infection, while the other included hospitalized patients who screened positive for HCV antibody and received reflex HCVcAg testing for diagnosis of active HCV infection, and if positive, were referred to a treatment center. To ensure comparability, we limited our care cascade analysis to 4 months following a positive HCV antibody test result and calculated each strata of the cascade based on the percent from the previous strata. The first cascade covered a period of time during which antibody screening was offered to all hospitalized patients and those who screened positive were referred to a treatment center to receive diagnostic viremia testing (1 September 2017 to 28 February 2018). The second cascade covered the period of time when antibody screening was offered to all hospitalized patients and those who screened positive had reflex testing for HCVcAg (1 March 2018 to 31 December 2018), with results and referral communicated to the patient by telephone as described in the methods.

For our analysis, individuals screened for hepatitis C multiple times were reported only once using data from their most recent screening, and screening rates relative to the adult population were determined using 2014 census data.2,11 We limited our analysis to adults aged ≥18 years although treatment is available for children aged 12–17. All data were de-identified prior to analysis. Statistical significance was determined using chi-square test with p value <0.05; analysis was performed in SAS version 9.4.

This analysis utilizes data from Georgia’s hepatitis C elimination program, which was determined by Georgia’s NCDC to be a program evaluation and deemed by NCDC and CDC to be a non-research public health program activity.

Results:

Screening

Screening programs for hepatitis C began in early 2015 in anticipation of the program launch in April of that year. As of December 31, 2018, a total of 1,101,530 adults (39.6% of the Georgian adult population) had been screened with a rapid anti-HCV test at various settings throughout the country, with more screened at outpatient settings than any other setting (Table 1). Screening rates greatly increased in November 2016 (Fig. 1) with implementation of the hospital-based screening program, which mandated medical facilities to offer anti-HCV screening to all hospitalized patients; since then, 466,087 hospitalized adults have been screened, an average of 33,292 patients per month through December 2018.

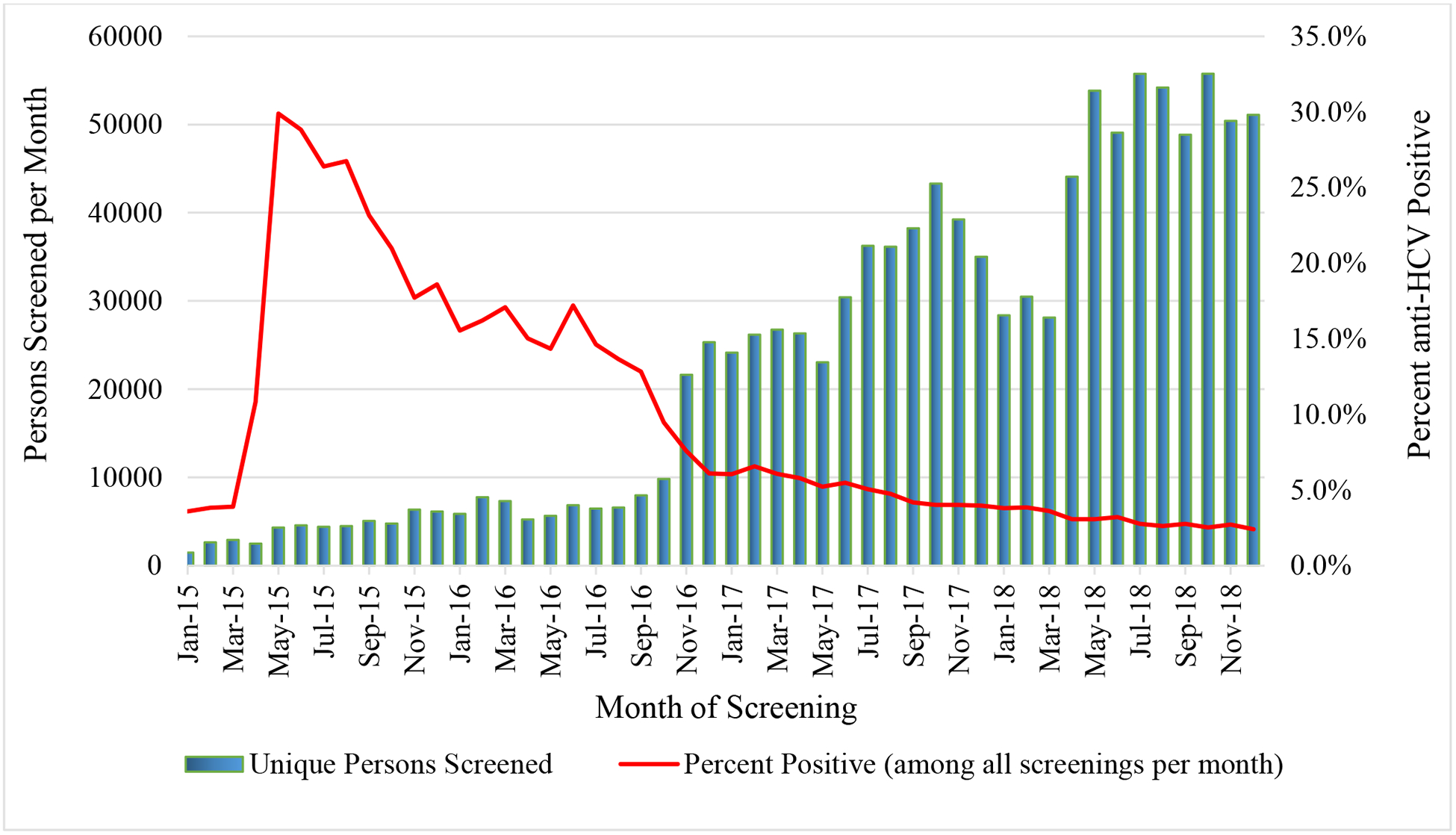

Fig 1.

Adults screened for hepatitis C virus antibody (anti-HCV) and percent positive per month, Georgia hepatitis C elimination program, January 2015 – December 2018

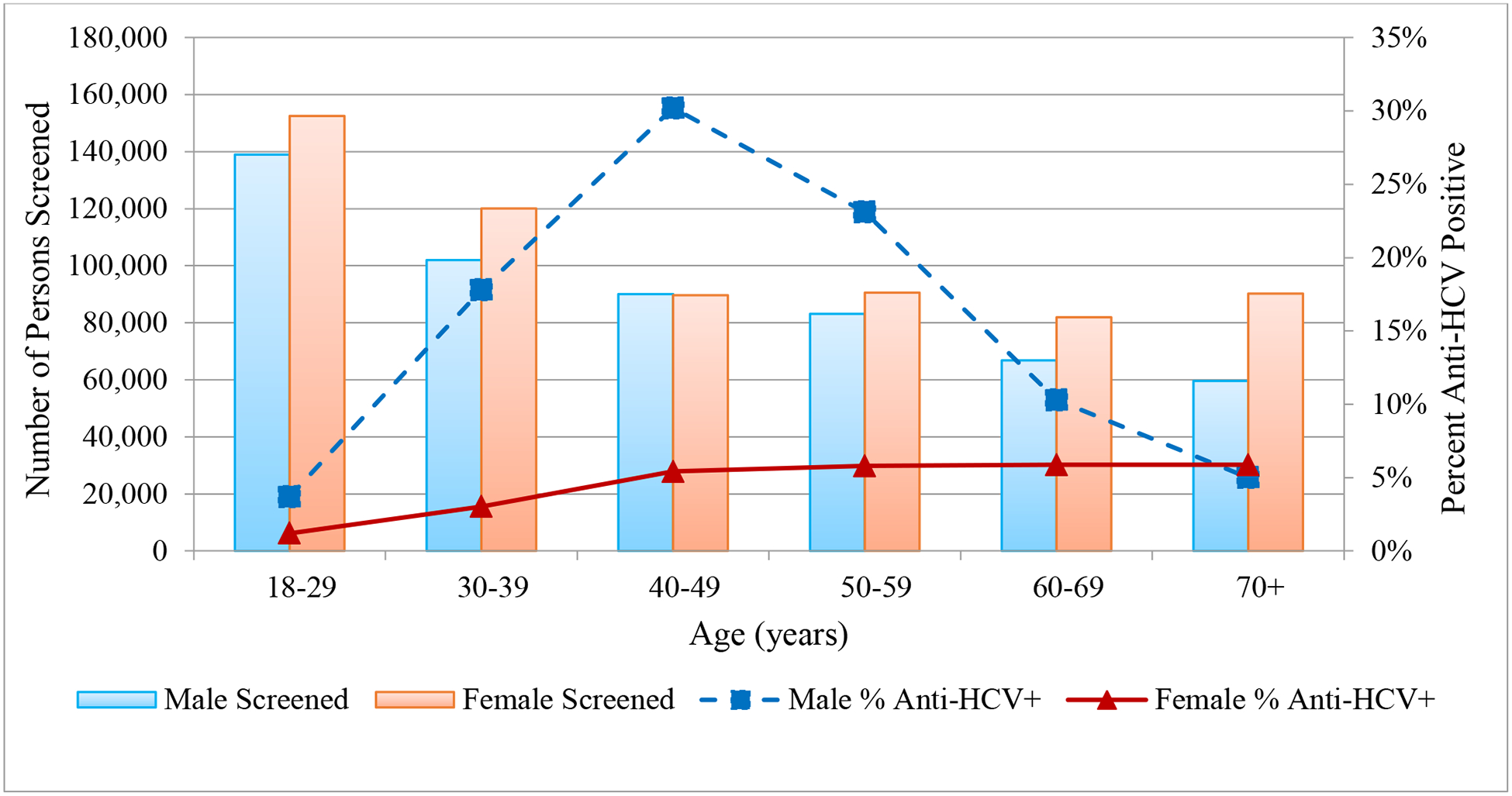

Of those screened, 98,430 (8.9%) had a positive anti-HCV result. The percentage of individuals who tested positive for anti-HCV peaked immediately following launch of the elimination program (29.8%) in May 2015 (Fig. 1). However, over time, the percentage of people who are anti-HCV positive has gradually decreased, dropping to 2.4% by December of 2018 (Fig. 1). Anti-HCV positivity rates varied by site, with the highest rates among harm-reduction centers and correctional facilities; the lowest rates were observed among antenatal clinic attendees (Table 1). Anti-HCV positivity rates also varied by age and sex, with the highest rates occurring among men aged 40–49 years (Fig. 2).

Fig 2:

Hepatitis C virus antibody (anti-HCV) screening and percent positive by age and sex, Georgia, January 2015 – December 2018

Diagnosis of Active HCV Infection

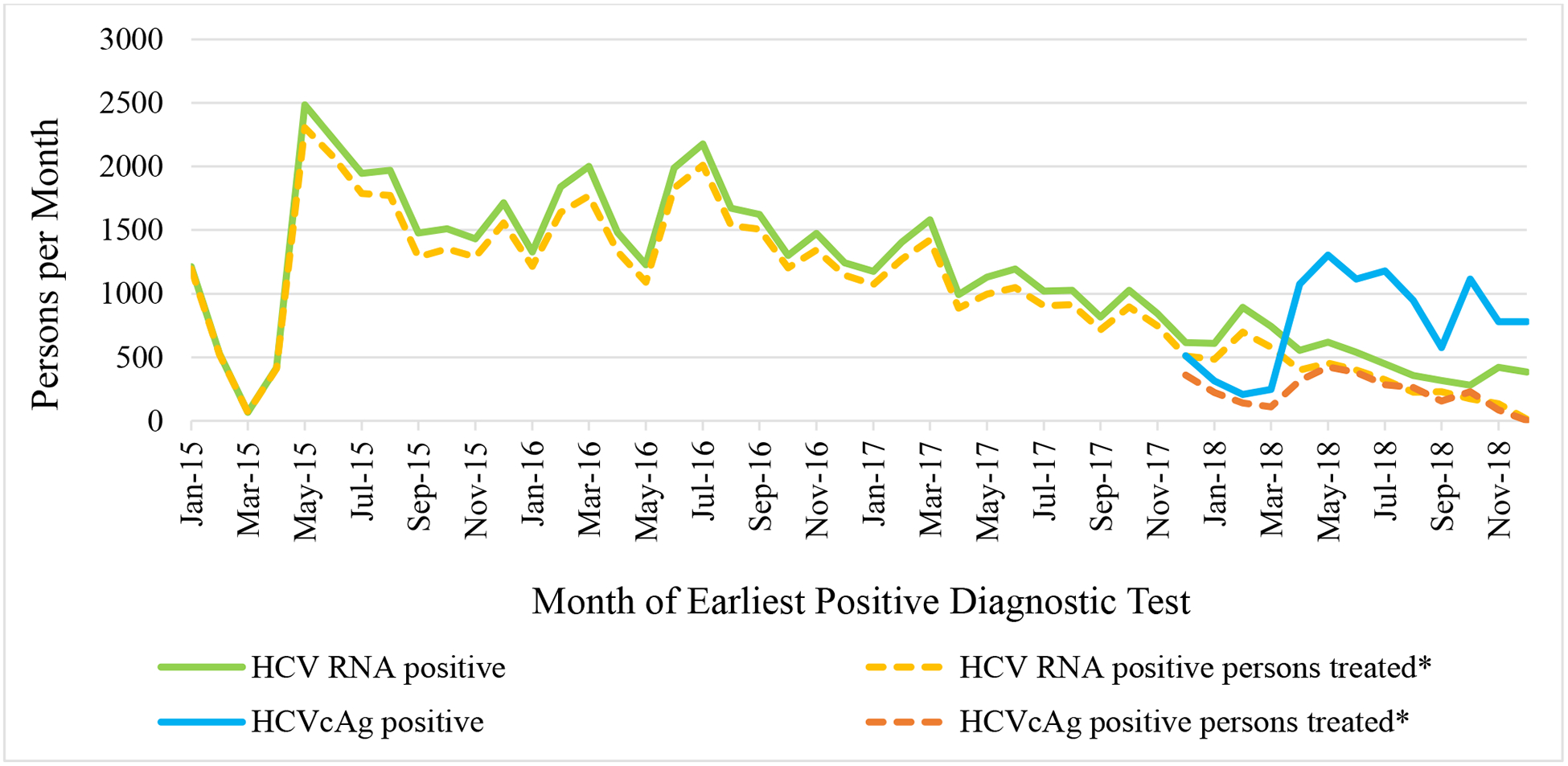

Of the 98,430 people with positive anti-HCV test results, 78,484 (79.7%) received HCV RNA or HCVcAg testing to determine whether they had active HCV infection; of those, 66,916 (85.3%) tested positive. Initially, those who screened positive on an antibody test were referred to a specialized treatment site for HCV RNA testing. Reflex HCVcAg testing was introduced broadly in March 2018 for those who screened positive for HCV antibody in hospitals, antenatal clinics, and blood banks. In the 6 months prior, from September 2017 – February 2018, 35.7% of individuals who screened positive for HCV antibody received viremia testing for active HCV infection (901/2,401 per month), compared to 74.1% during March – December 2018 (1,517/2,047 per month), a 97.5% increase. This reversed a downward trend since the peak in July 2016, when 2,641 received testing to diagnose active HCV infection (data not shown).

Treatment initiation and outcomes

From April 2015 through December 2018, of 66,916 persons diagnosed with active HCV infection by either HCV RNA or HCVcAg testing (introduced in December 2017), 52,576 (78.6%) initiated treatment. From the launch of the program through December 2017, rates of people testing HCV RNA positive closely paralleled rates of people initiating treatment, 44,617/49,153 (90.8%) (Fig. 3). However, from March 2018 through December 2018 (the period during which hospitalized patients, blood donors and pregnant women received reflex HCVcAg testing), only 2,254 (24.7%) of the 9,118 people who were HCVcAg positive initiated treatment compared with 2,939 (62.9%) of the 4,669 who received HCV RNA testing at a treatment center during the same time period, a decrease of 60.7% (p <0.05).

Fig 3. Hepatitis C virus RNA (HCV RNA) or HCV core antigen (HCVcAg) diagnostic testing and initiation of treatment* by test method and month of diagnosis, Georgia hepatitis C elimination program, January 2015 – December 2018.

* Beginning in December 2017 HCVcAg testing has been available in a limited number of harm-reduction sites, and these results are included in the analysis of hospitalized patients

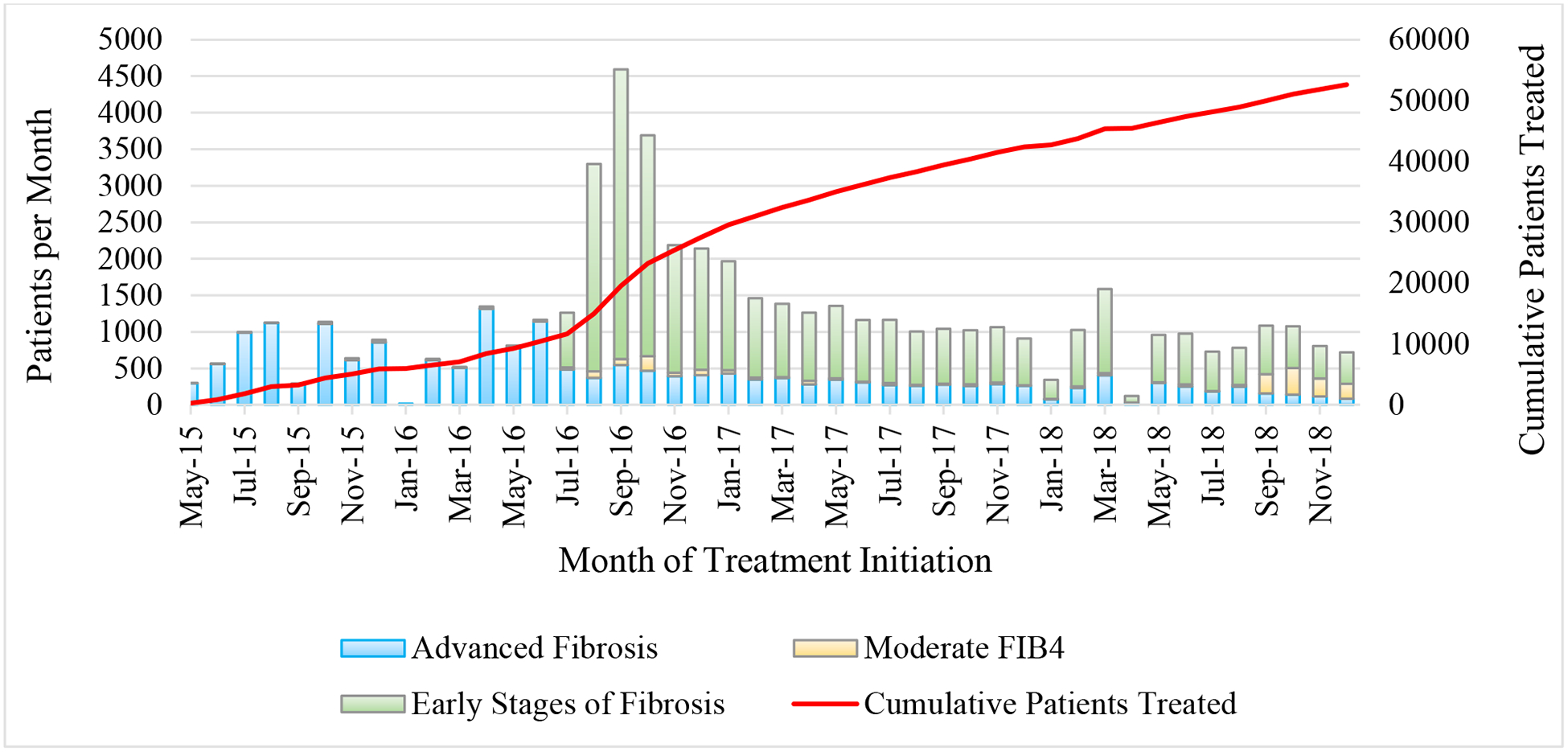

When the program launched in April 2015, only 4 specialized sites, all located in the capital of Tbilisi were authorized as treatment sites, but by December 2018, treatment capacity had expanded to 41 specialized sites throughout the country. As of December 2018, a total of 52,576 adults had enrolled in the treatment program and initiated treatment. From April 2015 through May 2016, of 9,257 patients who entered treatment, 9,056 (97.8%) had severe liver disease (Fig. 4). When the program was expanded for all HCV-infected individuals, of 43,319 entering the treatment program from July 2016 through December 2018, only 9,691 (22.4%) had severe liver disease (Fig. 4).

Fig 4. Fibrosis stage of patients initiating treatment per month, Georgia hepatitis C elimination program, January 2015 – December 2018.

* Advanced fibrosis defined as fibroscan ≥ F3 or FIB4 > 3.25. Early stages of fibrosis: fibroscan < F3 or FIB4 < 1.45. Moderate: FIB4 1.45–3.25 with no fibroscan result. For all classifications, priority given to fibroscan result when available.

The number of patients initiating treatment per month peaked at 4,593 in September 2016, following the treatment expansion (Fig. 4). During the 2-year period from January 2017 through December 2018, an average of 1,041 patients per month began treatment (Fig. 4). As of December 2018, a total of 48,879 patients had completed at least one course of treatment (1,136 patients initiated a second course of treatment after relapse or discontinuation from their initial regimen). Among 46,574 eligible for SVR, 35,035 (75.2%) received SVR testing, of whom 34,513 (98.5%) ultimately achieved SVR after their latest course of treatment (Fig. 5). When considering the initial treatment regimen only (excluding retreatment data), viral cure rates were lower among 5,077 patients who received SOF-based regimens (n = 4,170/5,077; 82.1%) than among 30,236 who received SOF/LED-based regimens (n = 29,765/30,236; 98.4%). SVR rates also varied by degree of fibrosis for both SOF-based and SOF/LED-based regimens, and by genotype only among patients receiving SOF-based regimens (data not shown).5 Among 52,576 patients initiating treatment, 1,280 (2.4%) discontinued treatment, with the most common causes for not completing treatment being death (49.4%; n = 632), self-discontinuation (19.9%; n = 255), and loss to follow-up (16.3%; n = 208). Of those who died during treatment, the majority 370/632 (58.5%) had severe liver disease (METAVIR scores of F3 or F4).

Fig 5.

Georgia hepatitis C elimination program care cascade, April 28, 2015 – December 31, 2018

Effectiveness of HCVcAg reflex testing on treatment initiation

To understand the impact of reflex HCVcAg on treatment initiation, to minimize bias, we did a sub-analysis of care cascades limited to hospitalized patients who received reflex HCVcAg viremia testing to those who were referred for RNA testing. A lower percent, 2,976/6,011 (49.5%) of those who were anti-HCV positive received diagnostic viremia testing when referred to a treatment center for RNA testing, compared to 3,191/4,205 (75.9%) of those diagnosed by reflex HCVcAg testing (p <0.05). However, among those who were diagnosed with active HCV infection by RNA testing, 1,937/2,508 (77.2%) initiated treatment, compared to 600/2,368 (25.3%) of those diagnosed by HCVcAg (p <0.05). When we compare the 2 care cascades, we find that, overall, among those screened and diagnosed by RNA 1,937/6,011 (32.2%) initiated treatment, compared to 600/4,205 (14.3%) of those in the HCVcAg cascade (p <0.05) (Fig. 6).

Fig 6.

Care cascade, by percentage, among hospitalized patients before and after the implementation of HCVcAg reflex testing.

Discussion:

The availability of all-oral DAAs capable of curing HCV infection has transformed the global landscape, providing a novel opportunity to eliminate chronic hepatitis C as a public health threat.12,13 Georgia was the first country in the world to formally launch a national hepatitis C elimination program but has recently been joined by other countries, such as Egypt, Iceland, and Australia.12,14,15 Georgia’s elimination program stands out for its comprehensive approach, with innovative strategies in place to not only identify those infected with HCV and link them to care and treatment services, but also to improve access to quality diagnostics, safeguard the nation’s blood supply, and reduce infection with blood borne pathogens among people who inject drugs and in the healthcare setting.1,7,16

Since the launch of the program in 2015, numerous lessons learned have been identified and shared, not only successes, but challenges.3,7,8,16 Nevertheless, access to treatment has been, and continues to be, the cornerstone of the program. Georgia has made remarkable progress since launching the elimination program in 2015; of the estimated 150,000 persons living with hepatitis C in the country,2 approximately one-third have been identified and received treatment,5 averting an estimated 3,000 deaths and preventing over 20,000 new HCV infections.17 Yet despite this success, Georgia faces challenges in identifying and linking to care the missing thousands still living with hepatitis C in the country that were highlighted in this report.

The program began with 4 treatment centers and limited options for screening. Georgia rapidly expanded access to treatment, and as of December 2018, more than 40 treatment centers were operating throughout the country, some of which were located in high-risk settings like correctional facilities and harm-reduction sites. Enrollment at the start of the program in 2015 and 2016 was high, and can be attributed in part to the large proportion of people who were anti-HCV positive, as high as 30% in May of 2015 (Fig. 1). This is likely reflective of the large number of people who knew they were infected with HCV prior to program implementation, but had not yet sought or could not afford treatment. The 2015 serosurvey found that 36% of people who tested anti-HCV positive were aware of their infection, but few had sought care, citing the availability and cost of treatment as major barriers.2

During the 18-month period between May 2015 and January 2017, about 20% (30,000 of the 150,000 living with HCV infection in Georgia) of the target population entered treatment, with a spike observed after enrollment restrictions were expanded to include all infected persons regardless of stage of liver disease (Fig. 4). However, the number of patients entering treatment began to decline precipitously in late 2016, likely reflecting an exhaustion of the number of patients who were aware of their infection and motivated to receive treatment- the “low hanging fruit” of the program. In response, the program took steps to decrease barriers, including lowering costs of diagnostic testing, increasing the number of screening and treatment sites, and implementing innovative programs to identify and link to care HCV-infected people. Although treatment was offered to Georgians free-of-charge, diagnostics were not, and testing-related costs were subsequently identified as a barrier to program enrollment, which may partly explain the 25% who were eligible but did not receive SVR testing.9,18 In response, the program began aggressively lowering the costs of diagnostics, and simultaneously simplifying testing and care guidelines; for example, the requirement of some diagnostics, such as HCV RNA testing at 4 weeks of treatment and at end-of-treatment, have been eliminated. Studies are underway to identify additional barriers to testing for remaining harder-to-reach HCV-infected populations.

Over 98,000 people screened positive for anti-HCV through December 2018, representing nearly half of the estimated number of anti-HCV positive adults in Georgia.2 Nevertheless, of those who screened positive since the program launched, over 20% failed to receive further diagnostic testing to diagnose active infection. To address this gap, the hospital-based hepatitis C screening program, the blood banks, and antenatal clinics, which screen a large proportion of the monthly total screened, began conducting reflex HCVcAg testing in March 2018. This strategy proved effective in nearly doubling the rate of persons receiving viremia testing following a positive screening test. Paradoxically, while there was a dramatic increase in persons receiving diagnostic testing to determine active infection, rates of treatment initiation among those diagnosed in these settings (hospitals, antenatal clinics, and blood banks), even with reflex testing, were lower than those in other settings (e.g., outpatient care, harm-reduction settings, prisons). This observation may be multifactorial. First, there are inherent differences among the populations seeking healthcare in different settings. Perhaps more significantly, the shift in provider responsibility for linking patients diagnosed with active HCV infection to care from hepatitis C treatment provider clinics (the only sites conducting HCV RNA testing prior to reflex testing) to the National Reference Laboratory, which relies on NCDC for communication of results to patients by telephone, clearly could have contributed to the lower rates observed. Patients who obtained HCV RNA testing at treatment sites had voluntarily taken an important step in seeking care by going to a treatment site, while reflex testing, which automated the process, did not rely on the patient’s initiative to seek further care. It is likely that many patients who received reflex testing may not have even been aware of their HCV infection, counseled on the results, or motivated to access treatment. To examine this issue more closely, we analyzed a subset of hospitalized patients and compared the care cascade among those patients receiving diagnostic testing by referral for RNA testing to the patients receiving reflex HCVcAg testing. This analysis revealed that overall treatment initiation rates were significantly lower among the patients tested with the HCVcAg. Of course, this is not a function of the HCVcAg test, but rather the processes of informing and counseling patients of their HCV infection. This is a classic example of the law of unintended consequences.

The reduced treatment initiation rates associated with reflex HCVcAg testing have been recognized and are being addressed by the program. The ability to recognize and react to challenges can be attributed to Georgia’s advanced hepatitis C information system, which links screening, laboratory diagnostics, and treatment data and allows for near real-time analysis and feedback on program performance. This system affords policy makers the ability to quickly identify deficiencies and make evidence-based adjustments. In response to the drop-off in treatment initiation rates, the program is developing and piloting strategies, such as deploying patient navigators in hospitals, and decentralizing diagnostic testing, to overcome this gap in linkage to care. The Georgia experience highlights challenges that may be encountered when screening, testing for viremia, and treatment are conducted at different sites.

A major initiative in 2019 is integration of screening, care and treatment services in primary healthcare settings and harm-reduction centers throughout the country. This allows patients and harm-reduction beneficiaries to receive hepatitis C care and treatment services in familiar and convenient locations, a strategy that has been demonstrated to be effective.19,20 Georgia plans to expand treatment services to every district in the country and all harm-reduction sites, expanding not only geographic access, but also providing services to the most marginalized and at-risk populations. The results of these efforts could be the key to accessing the “hardest to reach” populations.

The first of its kind, Georgia’s comprehensive HCV elimination program, which was recently recognized as the first European Association for the Study of Liver- international Liver Foundation (EILF) Center of Excellence in Viral hepatitis Elimination,16 can inform hepatitis C elimination efforts in countries throughout the world. Challenges, as well as best practices, have been identified and are being shared. Georgia’s 2015 serosurvey paved the way for the program’s success by yielding accurate estimates of the hepatitis C burden and facilitating target setting.2 Gilead Science’s commitment to providing program participants with medications free-of-charge resulted in an early and robust enrollment of persons already aware of their HCV infection, but unable to afford out-of-pocket treatment costs. Although the cost of medications was a major barrier in 2015 when Georgia launched the program, given the dramatic reductions in cost of DAAs in many countries, this may no longer be an important impediment in much of the world.21 However, it is clear from the experience in Georgia that even with no-cost medications, reaching a substantial proportion of those living with hepatitis C can be a major challenge; additional barriers encountered included the cost of diagnostics, which contributed to relatively low treatment initiation and SVR testing rates, geographic access to care, stigmatized and marginalized populations, and lack of awareness or motivation by the public and possibly by health care providers. Another important lesson from Georgia’s HCV elimination program is that a comprehensive, evidence-based program with near real-time access to program data and indicators, which allows for nimble programmatic adjustments, may be the key to overcoming barriers and achieving timely and cost-effective hepatitis C elimination.

Other countries embarking on hepatitis C elimination efforts will likely experience barriers similar to those encountered by the country of Georgia.12,15,22 Georgia offers best practices and lessons learned that can be adapted when developing national elimination plans, particularly in reducing barriers to identifying HCV-infected individuals and linking them to curative treatment. Georgia will encounter new, unforeseen challenges, and must continue to identify and develop innovative approaches to overcoming barriers as the country strives to meet its elimination goals. This country’s robust hepatitis C elimination efforts can serve as a model for countries developing programs not only to eliminate viral hepatitis, but other public health threats as they emerge.

Highlights.

One-third of HCV-infected individuals in Georgia have received treatment.

Use of reflex HCV core antigen greatly increased the number of individuals diagnosed with active infection

Identification of HCV-infected individuals and treatment initiation continue to be major challenges to HCV elimination in Georgia.

Financial support

The authors received no financial support to produce this manuscript.

Abbreviations

- ANC

antenatal clinic

- DAA

direct-acting antiviral

- FIB-4

Fibrosis-4 score

- HCVcAg

hepatitis C core antigen

- MOU

memorandum of understanding

- NCDC

National Centers for Disease Control and Public Health

- SVR

sustained virologic response

Footnotes

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest that pertain to this work.

Publisher's Disclaimer: Disclaimer

Publisher's Disclaimer: The findings and conclusions in this report are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official position of the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

References

- [1].Nasrullah M, Sergeenko D, Gvinjilia L, Gamkrelidze A, Tsertsvadze T, Butsashvili M, et al. The role of screening and treatment in national progress toward hepatitis C elimination - Georgia, 2015–2016. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2017;66(29):773–776. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Hagan LM, Kasradze A, Salyer SJ, Gamkrelidze A, Alkhazashvili M, Chanturia G, et al. Hepatitis C prevalence and risk factors in Georgia, 2015: setting a baseline for elimination. BMC Public Health 2019;19(Suppl 3):480. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Mitruka K, Tsertsvadze T, Butsashvili M, Gamkrelidze A, Sabelashvili P, Adamia E, et al. Launch of a nationwide hepatitis C elimination program–Georgia, April 2015. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2015;64(28):753–757. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Gvinjilia L, Nasrullah M, Sergeenko D, Tsertsvadze T, Kamkamidze G, Butsashvili M, et al. National progress toward hepatitis C elimination - Georgia, 2015–2016. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2016;65(41):1132–1135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Tsertsvadze T, Gamkrelidze A, Chkhartishvili N, Abutidze A, Sharvadze L, Kerashvili V, et al. Three years of progress towards achieving hepatitis C elimination in the country of Georgia, April 2015 – March 2018. Clin Infect Dis 2019. 10.1093/cid/ciz956 [Epub ahead of print]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Freiman JM, Tran TM, Schumacher SG, White LF, Ongarello S, Cohn J, et al. Hepatitis C core antigen testing for diagnosis of hepatitis C virus infection: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Ann Intern Med 2016;165(5):345–355. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Nasrullah M, Sergeenko D, Gamkrelidze A, Averhoff F. HCV elimination - lessons learned from a small Eurasian country, Georgia. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol 2017;14(8):447–448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].National Hepatitis C Virus Elimination Progress Report, Georgia − 2015–2017. Appendix 2. Available at: https://www.moh.gov.ge/uploads/files/2019/Failebi/25.04.2019-2.pdf. [Accessed 6 May 2019].

- [9].Zarkua J. Simplification of pretreatment diagnostic evaluation and ontreatment monitoring procedures within HCV elimination project Presented at the 4th hepatitis C Technical Advisory Group (TAG) meeting. Tbilisi, Georgia, November 28, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- [10].Stvilia K, Spradling PR, Asatiani A, Gogia M, Kutateladze K, Butsashvili M, et al. Progress in testing for and treatment of hepatitis C virus infection among persons who inject drugs — Georgia, 2018. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2019;68(29):637–641. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].National Statistics Office of Georgia. Main statistics: population. Tbilisi, Georgia: National Statistics Office of Georgia; 2016. Available at: http://geostat.ge/index.php?action=page&p_id=152&lang=eng. [Accessed 6 May 2019]. [Google Scholar]

- [12].Cooke GS, Andrieux-Meyer I, Applegate TL, Atun R, Burry JR, Cheinquer H, et al. , Lancet Gastroenterology & Hepatology Commissioners. Accelerating the elimination of viral hepatitis: a lancet Gastroenterology & hepatology commission. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol 2019;4(2):135–184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].World Health Organization. Global Hepatitis Report, 2017. WHO; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- [14].Esmat G, El-Sayed MH, Hassany M, Doss W, Waked I, National Committee for the Control of Viral Hepatitis. One step closer to elimination of hepatitis C in Egypt. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol 2018;3(10):665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Popping S, Bade D, Boucher C, van der Valk M, El-Sayed M, Sigurour O, et al. The global campaign to eliminate HBV and HCV infection: international viral hepatitis elimination meeting and core indicators for development towards the 2030 elimination goals. J Virus Erad 2019;5(1):60–66. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Averhoff F, Lazarus JV, Sergeenko D, Colombo M, Gamkrelidze A, Tsertsvadze T, et al. Excellence in viral hepatitis elimination - lessons from Georgia. J Hepatol 2019;71:645–647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Walker JG, Kuchuloria T, Sergeenko D, Fraser H, Lim AG, Shadaker S, et al. Interim effect evaluation of the hepatitis C elimination programme in Georgia: a modelling study. Lancet Glob Health 2020;8:e244–e253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Tsereteli M. Barriers and facilitators to enrollment in the treatment program among general population Presented at the 4th hepatitis C Technical Advisory Group (TAG) meeting. Tbilisi, Georgia, November 28, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- [19].Kattakuzhy S, Gross C, Emmanuel B, Teferi G, Jenkins V, Silk R, et al. Expansion of treatment for hepatitis C virus infection by task shifting to community-based nonspecialist providers: a nonrandomized clinical trial. Ann Intern Med 2017;167(5):311–318. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Gupta N, Mbituyumuremyi A, Kabahizi J, Ntaganda F, Muvunyi CM, Shumbusho F, et al. Treatment of chronic hepatitis C virus infection in Rwanda with ledipasvir-sofosbuvir (SHARED): a single-arm trial. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol 2019;4(2):119–126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].World Health Organization. Progress Report on Access to Hepatitis C Treatment: Focus on Overcoming Barriers in Low and Middle Income Countries. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 2018. http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/260445/WHO-CDS-HIV-18.4-eng.pdf;jsessionid=7090253C8CCE163E5B148508158B7536?sequence=1. [Accessed 2 May 2019]. [Google Scholar]

- [22].Doyle JS, Scott N, Sacks-Davis R, Pedrana AE, Thompson AJ, Hellard ME, et al. , Eliminate Hepatitis C Partnership. Treatment access is only the first step to hepatitis C elimination: experience of universal anti-viral treatment access in Australia. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2019;49(9):1223–1229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]