Abstract

Background

Pregnancy-associated breast cancer (PABC) is defined as breast cancer that is diagnosed during pregnancy and/or the postpartum period. Definitions of the duration of the postpartum period have been controversial, and this variability may lead to diverse results regarding prognosis. Moreover, evidence on the dose-response association between the time from the last pregnancy to breast cancer diagnosis and overall mortality has not been synthesized.

Methods

We systematically searched PubMed, Embase, and the Cochrane Library for observational studies on the prognosis of PABC published up to June 1, 2019. We estimated summary-adjusted hazard ratios (HRs) and the corresponding 95% confidence intervals (CIs). Subgroup analyses based on diagnosis time, PABC definition, geographic region, year of publication and estimation procedure for HR were performed. Additionally, dose-response analysis was conducted by using the variance weighted least-squares regression (VWLS) trend estimation.

Results

A total of 54 articles (76 studies) were included in our study. PABC was associated with poor prognosis for overall survival (OS), disease-free survival (DFS) and cause-specific survival (CSS), and the pooled HRs with 95% CIs were 1.45 (1.30–1.63), 1.39 (1.25–1.54) and 1.40 (1.17–1.68), respectively. The corresponding reference category was non-PABC patients. According to subgroup analyses, the varied definition of PABC led to diverse results. The dose-response analysis indicated a nonlinear association between the time from the last delivery to breast cancer diagnosis and the HR of overall mortality (P < 0.001). Compared to nulliparous women, the mortality was almost 60% higher in women with PABC diagnosed at 12 months after the last delivery (HR = 1.59, 95% CI 1.30–1.82), and the mortality was not significantly different at 70 months after the last delivery (HR = 1.14, 95% CI 0.99–1.25). This finding suggests that the definition of PABC should be extended to include patients diagnosed up to approximately 6 years postpartum (70 months after the last delivery) to capture the increased risk.

Conclusion

This meta-analysis suggests that PABC is associated with poor prognosis, and the definition of PABC should be extended to include patients diagnosed up to approximately 6 years postpartum.

Keywords: Pregnancy-associated breast cancer, Prognosis, Survival, Dose-response, Meta-analysis

Background

Breast cancer is the second most common cancer worldwide and the most commonly occurring malignancy in women [1]. Due to the trend of delayed delivery, the number of women with breast cancer during a pregnancy or in the subsequent few years after a pregnancy is expected to increase [2]. Breast cancer occurring during pregnancy is a challenging clinical situation since the welfare of both the mother and the foetus must be considered in any treatment plan. Conventionally, pregnancy-associated breast cancer (PABC) is defined as breast cancer that is diagnosed during pregnancy or the postpartum period. Definitions of how many years after delivery breast cancer can be diagnosed under this definition have ranged from 0.5 to 5 years, and sometimes even longer [3, 4]. PABC is viewed as a clinically and biologically special type of breast cancer and only comprises 0.2–0.4% of all breast cancers [5, 6]. However, it is the most common cancer in pregnancy and is diagnosed in approximately 15 to 35 per 100,000 births, and the number of breast cancer cases diagnosed during pregnancy is less than after delivery [7–10].

Pregnancy itself may temporarily increase the risk of developing breast cancer, although it has a long-term protective effect on the development of breast cancer [11, 12]. However, whether PABC has a worse prognosis is currently controversial. A meta-analysis published in 2016 showed that the risk of death increased in women with PABC compared with women with non-PABC (pooled hazard ratio (HR), 1.57; 95% confidence interval (CI), 1.35–1.82) [13]. However, other recent studies found no significant difference in the prognosis of PABC and non-PABC [14–17]. Meanwhile, the specific definition of PABC has varied and this variability may lead to diverse results on the relationship among pregnancy, postpartum and breast cancer. Therefore, it is necessary to specify the definition of PABC by summarizing epidemiological evidence. This study was initiated to understand the prognosis of PABC and examine the dose-response relationship to provide quantitative evidence for defining PABC.

Methods

Search strategy

This meta-analysis was performed in accordance with the preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses (PRISMA) guidelines. We did our best to include studies published to date regarding the prognosis of PABC. Eligible studies were found by searching PubMed, Embase, and the Cochrane Library for relevant reports published before June 1, 2019. The keywords used for the search were (“pregnan*” OR “gestation*” OR “childbirth” OR “postpartum” OR “parity”) AND “breast” AND (“cancer” OR “neoplasia” OR “carcinoma”). The references lists of all retrieved articles and previous systematic reviews were manually searched.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

All eligible studies met the following criteria: (1) observational prognostic studies with a follow-up period longer than 6 months; (2) participants were diagnosed with breast cancer by clinical diagnosis and/or histologically; (3) the case group was diagnosed with PABC, and the control group was non-PABC or nulliparity; (4) the outcomes were in terms of overall survival (OS), disease-free survival (DFS) or cause-specific survival (CSS); and (5) the risk point estimate was reported as an HR with 95% CI, or the data were presented such that an HR with 95% CI could be calculated. The exclusion criteria were as follows: (1) duplicated or irrelevant articles; (2) reviews, letters, and case reports; (3) non-human studies; and (4) studies with inappropriate data for meta-analysis, such as incomplete or inconsistent data.

Data extraction

Two reviewers extracted the data independently using a predefined data extraction form. Any disagreements were resolved by discussion. The extracted data included the first author, publication year, country, PABC definition, control definition, sample size, cancer type, stage or grade, age, matching criteria, adjusted variables, and adjusted HRs with 95% CIs.

Assessment of study quality

The methodological quality of the studies was assessed by the Newcastle-Ottawa scale (NOS) [18]. A score of 0–9 was allocated to each study, with higher scores indicating higher quality.

Meta-analysis and statistical analysis

We used adjusted HRs and 95% CIs, which are most appropriate for time-to-data events. If HRs were not reported, we estimated HRs from the raw data or Kaplan-Meier curves [19]. The I-square (I2) test was performed to assess the impact of study heterogeneity on the results of the meta-analysis. If severe heterogeneity was present at I2 > 50%, a random effects model was chosen; otherwise, a fixed effects model was used. Visual inspection of the funnel plot and Egger’s and Begg’s tests were performed to assess publication bias. Subgroup analyses were performed according to the diagnosis time, PABC definition, geographic region, year of publication and estimation procedure for HR.

Variance-weighted least squares regression (VWLS) model was used to evaluate the dose-response association between the time from the last pregnancy to breast cancer diagnosis and HR of overall mortality [20]. Restricted cubic splines were used to check the time from the last pregnancy as a continuous, nonlinear exposure, and the time was defined by the 5th, 35th, 65th and 95th percentiles of the distribution [21]. The time from the last pregnancy to breast cancer diagnosis reported in each study was converted to months. We used the average value of the lower and upper limits of each category. If the lowest category was open ended, the average value of the upper limit and 0 was used. If the highest category was open ended, the average value was defined as 1.5 times the lower limit. All statistical analyses were performed using STATA Version 13.0. P < 0.05 was considered significant.

Results

Search results and study characteristics

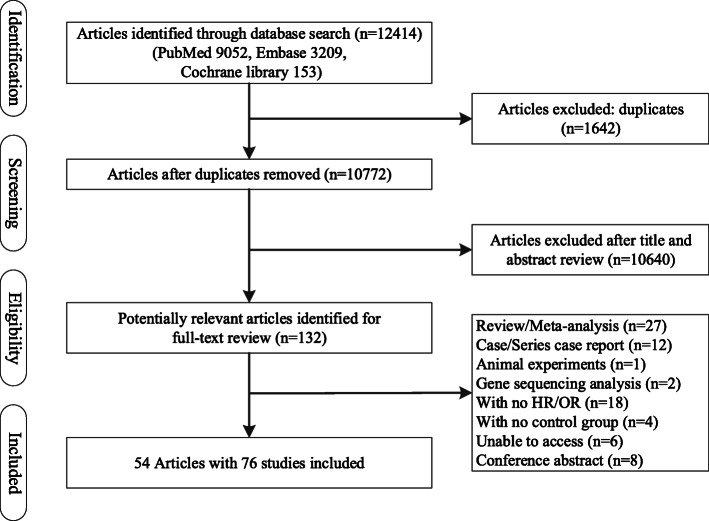

We initially identified 12,414 articles and screened their titles and abstracts (Fig. 1). After duplicated and irrelevant articles were excluded, 54 articles with 76 studies met the inclusion criteria and were thus included in our meta-analysis. The quality of the studies was assessed based on the NOS and ranged from 6 to 9 (mean of 7.2). The characteristics of the studies are summarized in Table 1.

Fig. 1.

Schematic representation of the study selection process

Table 1.

Characteristics of the studies included in the meta-analysis

| Study ID | Country | No. of PABC cases | No. of controls | PABC definition | Cancer stage or grade | Mean/median age of PABC | Follow-up years | Outcomes measured | HR estimate | HR | 95% CI | NOS score | Matching criteria | Adjusting variable |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mausner, 1969 [22] | USA | 73 | 647 | Pregnancy & < 6 months postpartum | Stage I II III, Grade I II III | 35 | 5 | OS | indirect | 1.36 | 1.07–1.73 | 7 | – | – |

| Wallgren, 1977 [23] | Sweden | 15 | 58 | Pregnancy & < 12 months postpartum | Grade I II III | < 30 | 10 | OS | indirect | 1.35 | 0.71–2.58 | 7 | – | – |

| Nugent, 1985 [24] | USA | 19 | 155 | Pregnancy | Stage I II III | 32 | 5 | OS | indirect | 0.96 | 0.55–1.67 | 6 | – | – |

| Tretli, 1988-Pregnancy [25] | Norway | 20 | 40 | Pregnancy | Stage I II III | 33 | 4 | OS | indirect | 2.41 | 1.32–4.37 | 6 | Diagnosed year, diagnosed age | – |

| Tretli, 1988-Postpartum [25] | Norway | 15 | 40 | Unspecified | Stage I II III | 36 | 4 | OS | indirect | 1.47 | 0.66–3.27 | 6 | – | |

| Greene, 1988 [26] | USA | 8 | 36 | Pregnancy | NA | <35 | 14 | OS | indirect | 1.50 | 0.18–12.62 | 6 | – | – |

| Petrek, 1991 [27] | USA | 56 | 166 | Pregnancy & < 12 months postpartum | NA | – | 5 | OS | paper | 0.74 | 0.37–1.45 | 6 | – | Node status |

| Zemlickis, 1992 [28] | Canada | 102 | 269 | Pregnancy & postpartum (unspecified) | Stage 0 I II III IV | 33 | 25 | CSS | indirect | 1.25 | 0.93–1.69 | 8 | Stage, age at diagnosis | – |

| Ishida, 1992 [29] | Japan | 192 | 191 | Pregnancy & < 24 months postpartum | Stage 0 Tis I II III IV | 32 | 10 | OS | indirect | 2.00 | 1.27–3.16 | 6 | – | |

| Guinee, 1994-Pregnancy [30] | USA | 26 | 139 | Pregnancy | NA | 28(20–29) | 10 | OS | paper | 2.83 | 1.24–6.45 | 8 | – | Tumour size, number of positive axillary nodes |

| Guinee, 1994-Postpartum [30] | USA | 40 | 139 | < 12 Months postpartum | NA | 28(20–29) | 10 | OS | paper | 1.88 | 0.88–3.98 | 8 | – | |

| Von Schoultz, 1995 [31] | Sweden | 173 | 1740 | Pregnancy & < 60 months postpartum | NA | < 50 | 7 | DFS | paper | 1.02 | 0.72–1.43 | 9 | – | Age, nodal status, tumour size, ER status |

| Ezzat, 1996-OS [32] | Saudi Arabia | 28 | 84 | Pregnancy | Stage I II III | 20–45 | 7 | OS | paper | 0.90 | 0.6–1.3 | 6 | Year of diagnosis, date of beginning | – |

| Ezzat, 1996-DFS [32] | Saudi Arabia | 28 | 84 | Pregnancy | Stage I II III | 20–45 | 7 | DFS | paper | 1.10 | 0.8–1.5 | 6 | – | |

| Anderson, 1996-OS [33] | USA | 22 | 205 | Pregnancy & < 12 months postpartum | Stage 0 I II IIIa | < 30 | 10 | OS | paper | 2.40 | 1.28–4.50 | 8 | – | Stage, axillary LN involvement, adjuvant CT, tumour size |

| Anderson, 1996-DFS [33] | USA | 22 | 205 | Stage 0 I II IIIa | < 30 | 10 | DFS | indirect | 3.19 | 1.20–8.49 | 8 | – | ||

| Bonnier, 1997-OS [34] | France | 154 | 308 | Pregnancy & < 6 months postpartum | Grade I II III | 33.9(23.2–46.4) | 5 | OS | paper | 1.46 | 0.72–2.96 | 6 | – | Clinical tumour size, microscopic lymph-node involvement, inflammatory cancer, age |

| Bonnier, 1997-DFS [34] | France | 154 | 308 | Grade I II III | 5 | DFS | paper | 1.48 | 1.00–2.19 | 6 | – | |||

| Olson, 1998 [35] | USA | 146 | – | – | NA | < 45 | 15 | OS | paper | – | – | 7 | – | Age, tumour size, lymph nodes, ER status, histology |

| Reeves, 2000 [36] | UK | – | – | – | Stage I II III IV | < 60 | > 10 | OS | paper | – | – | 9 | – | Age at diagnosis, year of diagnosis, hospital, weight in kg |

| Ibrahim, 2000 [37] | Saudi Arabia | 72 | 216 | Pregnancy | Stage I II III IV, Grade I II III | 34 | 10 | OS | indirect | 0.94 | 0.62–1.44 | 6 | Age, stage, year of diagnosis | – |

| Daling, 2002 [38] | USA | 83 | 309 | < 24 Months postpartum | Stage I II III IV | < 45 | 5 | OS | indirect | 2.30 | 1.4–3.9 | 9 | – | Age, diagnosis year |

| Aziz, 2003 [39] | Pakistan | 24 | 48 | Pregnancy & < 12 months postpartum | NA | 32(20–45) | 7 | OS | indirect | 1.67 | 0.82–3.41 | 6 | Age, tumour grade, tumour size, axillary lymph node status | – |

| Siegelmann-Danieli, 2003-OS [40] | Israel | 22 | 192 | Pregnancy & < 12 months postpartum | NA | 33(25–27) | 5 | OS | indirect | 3.39 | 0.58–19.81 | 6 | – | – |

| Siegelmann-Danieli, 2003-DFS [40] | Israel | 20 | 181 | NA | 33(25–28) | 5 | DFS | indirect | 4.81 | 1.46–15.9 | 6 | – | – | |

| Bladstrom, 2003 [41] | Sweden | 94 | 14,599 | Pregnancy | NA | ≤45 | 5 | OS | paper | 2.40 | 2.0–2.9 | 9 | – | Age, time of diagnosis, time period interaction, number of children, age at first child’s birth |

| Bladstrom, 2003(2) [41] | Sweden | 94 | 14,599 | Pregnancy | NA | ≤45 | 10 | OS | paper | 1.20 | 0.9–1.7 | 9 | – | |

| Whiteman, 2004 [42] | USA | 59 | 355 | < 12 Months postpartum | NA | 20–45 | 15 | OS | paper | 1.51 | 1.02–2.23 | 9 | – | Surgery, radiation therapy, race, oral contraceptive use, education, BMI, stage history of breast disease |

| Rodriguez, 2008 [43] | USA | 797 | 4177 | Pregnancy & < 12 months postpartum | Stage I II III IV | < 55 | 13 | OS | paper | 1.14 | 1.00–1.29 | 9 | – | Race, tumour size, AJCC stage, surgery, hormone receptor |

| Stensheim, 2009-Pregnancy [44] | Norway | 59 | 13,106 | Pregnancy | NA | < 50 | 5 | CSS | paper | 1.23 | 0.82–1.81 | 7 | – | Age, diagnostic period, initial extent of disease |

| Stensheim, 2009-Postpartum [44] | Norway | 46 | 13,106 | < 6 Months postpartum | NA | < 50 | 5 | CSS | paper | 1.95 | 1.36–2.78 | 7 | – | |

| Beadle, 2009-OS [45] | USA | 104 | 564 | Pregnancy & < 12 months postpartum | Stage I II III | ≤35 | 10 | OS | indirect | 1.24 | 0.87–1.79 | 6 | – | – |

| Beadle, 2009-DFS (distant metastasis) [45] | USA | 104 | 564 | Pregnancy & < 12 months postpartum | Stage I II III | ≤35 | 10 | DFS | indirect | 1.35 | 0.98–1.85 | 6 | – | – |

| Beadle, 2009-DFS (locoregional recurrence) [45] | USA | 104 | 564 | Stage I II III | ≤35 | 10 | DFS | indirect | 1.44 | 0.78–2.66 | 6 | – | – | |

| Halaska, 2009-OS [46] | Greece | 32 | 32 | Pregnancy & < 12 months postpartum | Grade I II III | < 45 | 10 | OS | indirect | 1.42 | 0.58–3.48 | 6 | Age at diagnosis, tumour size, axillary lymph node status, presence or absence of metastatic deposits | – |

| Halaska, 2009-DFS [46] | Greece | 32 | 32 | Grade I II III | < 45 | 10 | DFS | indirect | 1.82 | 0.82–4.05 | 6 | – | ||

| Largillier, 2009-OS [47] | France | 105 | 788 | Pregnancy & < 12 months postpartum | Grade I II III | <35 | 10 | OS | paper | 1.51 | 1.05–2.20 | 7 | – | – |

| Largillier, 2009-DFS [47] | France | 105 | 788 | Grade I II III | <35 | 10 | DFS | paper | 1.25 | 0.90–1.74 | 7 | – | – | |

| Phillips, 2009 [48] | Multicentre | 676 | – | – | NA | – | 10 | OS | paper | – | – | 8 | – | Study centre, education, BMI, time since last full-term pregnancy, age at diagnosis |

| Moreira, 2010 [49] | Brazil | 87 | 252 | Pregnancy & < 12 months postpartum | NA | ≤ 45 | 10 | OS | paper | 1.52 | 1.10–2.10 | 7 | Registration institution, age, registration year | – |

| Johansson, 2011 [50] | Sweden | 1110 | 14,611 | Pregnancy & < 24 months postpartum | NA | 15–44 | 15 | OS | paper | 1.51 | 1.36–1.68 | 7 | – | Age, calendar time, education |

| Murphy, 2012 [51] | USA | 99 | 186 | Pregnancy & < 12 months postpartum | Grade 0 I II III | 35(24–48) | 18 | OS | paper | 0.59 | 0.29–1.17 | 7 | Age, year of diagnosis | Tumour grade, ER status, LN involvement |

| Azim, 2012-OS [52] | Italy | 65 | 130 | Pregnancy | NA | < 50 | 6 | OS | paper | 1.70 | 0.80–3.90 | 7 | Age, year of surgery, pathological tumour size, pathological nodal status | pN, neoadjuvant chemotherapy, ER |

| Azim, 2012-DFS [52] | Italy | 65 | 130 | Pregnancy | NA | < 50 | 6 | DFS | paper | 2.30 | 1.30–4.20 | 7 | Age, pT, pN, neoadjuvant chemotherapy, Ki-67, HER2, perivascular invasion | |

| Ali, 2012-OS [53] | USA | 40 | 40 | Pregnancy & < 12 months postpartum | Stage I II III IV | 33(24–42) | 16 | OS | indirect | 2.15 | 1.13–4.09 | 7 | – | Age and stage-matched |

| Ali, 2012-DFS [53] | USA | 40 | 40 | Stage I II III IV | 33(24–42) | 16 | DFS | indirect | 2.00 | 1.12–3.59 | 7 | – | ||

| Amant, 2013-OS [54] | Belgium | 311 | 865 | Pregnancy | Stage I II III, Grade I II III | 33(31–36) | 5 | OS | paper | 1.19 | 0.73–1.93 | 8 | – | Age at diagnosis, stage, grading, histologic tumour type, ER/PR status, HER2, chemotherapy |

| Amant, 2013-DFS [54] | Belgium | 311 | 865 | Pregnancy | Stage I II III, Grade I II III | 33(31–36) | 5 | DFS | paper | 1.34 | 0.93–1.91 | 8 | – | |

| Litton, 2013-OS [55] | USA | 75 | 150 | Pregnancy | Stage I II III | 24–45 | 5 | OS | paper | 1.87 | 1.04–3.36 | 7 | Age at diagnosis, stage at diagnosis, year of diagnosis | Age at diagnosis, year of diagnosis, clinical cancer stage, tumour nuclear grade |

| Litton, 2013-DFS [55] | USA | 75 | 150 | Pregnancy | Stage I II III | 24–45 | 5 | DFS | paper | 2.09 | 1.19–3.67 | 7 | ||

| Valentini, 2013 [56] | USA | 75 | 269 | Pregnancy & < 12 months postpartum | NA | 32.5(20–45) | 15 | OS | paper | 0.79 | 0.25–2.44 | 7 | – | Age at diagnosis, tumour size, lymph node status, ER status, use of chemotherapy, oophorectomy |

| Dimitrakakis, 2013 [57] | Greece | 39 | 39 | Pregnancy & < 12 months postpartum | Stage I II III IV, Grade I II III | 34.3 ± 5.0 | 5 | OS | paper | 9.28 | 2.94–29.27 | 6 | Stage, age, year of diagnosis | Stage, ER status, grade, age at diagnosis |

| Calliha, 2013-OS [58] | USA | 76 | 86 | Pregnancy & < 60 months postpartum | Stage 0 I II III IV, Grade I II III | ≤45 | 5 | OS | paper | 2.65 | 1.09–6.42 | 6 | – | Tumour biological subtype, clinical stage, year of diagnosis |

| Calliha, 2013-DFS [58] | USA | 74 | 84 | Pregnancy & < 60 months postpartum | Stage 0 I II III IV, Grade I II III | ≤45 | 5 | DFS | paper | 2.80 | 1.12–6.57 | 6 | – | Tumour biological subtype, clinical stage, year of diagnosis, local recurrence |

| Bell, 2013-OS [59] | Australia | 13 | 377 | Pregnancy & < 12 months postpartum | NA | < 48 | 5 | OS | paper | 2.50 | 0.5–11.7 | 6 | – | – |

| Bell, 2013-DFS [59] | Australia | 13 | 377 | Pregnancy & < 12 months postpartum | NA | < 48 | 5 | DFS | paper | 0.90 | 0.2–4.4 | 6 | – | – |

| Moller, 2013 [60] | UK | – | – | – | Stage I II III IV | 10–54 | 10 | OS | paper | – | – | 7 | – | Age, stage |

| Framarino-dei-Malatesta, 2014 [61] | Italy | 22 | 45 | Pregnancy | NA | 37.2 ± 3.2 | 10 | OS | indirect | 0.96 | 0.29–3.21 | 6 | Age | – |

| Madaras, 2014 [62] | Hungary | 31 | 31 | Pregnancy & < 12 months postpartum | – | 34 | 10 | OS | indirect | 5.76 | 2.09–15.98 | 7 | Age, year of first breast cancer diagnosis | – |

| Nagatsuma, 2014 [63] | Japan | – | – | – | Stage 0 I II III IV, Grade I II III | 26–44 | 10 | OS | paper | – | – | 7 | – | Age at diagnosis, AJCC clinical stage, histological tumour grade, oestrogen and progesterone receptor status, HER2 status |

| Strasser-Weippl, 2014 [64] | China | 109 | 1274 | Pregnancy & < 60 months postpartum | Grade I II III | < 45 | 5 | DFS | paper | 1.62 | 1.04–2.54 | 8 | – | Age, oestrogen receptor, progesterone receptor, HER2 status, disease stage |

| Genin, 2015-OS [65] | France | 87 | 174 | Pregnancy & < 12 months postpartum | Grade I II III | 35(27–40) | 10 | OS | indirect | 1.09 | 0.79–1.52 | 7 | Age, year of diagnosis | – |

| Genin, 2015-DFS [65] | France | 87 | 174 | Pregnancy & < 12 months postpartum | Grade I II III | 35(27–40) | 10 | DFS | paper | 1.87 | 1.05–3.33 | 7 | Age, year of diagnosis | Age, ER, HR status, tumour stage, HER2 status, Ki-67 rate |

| Iqbal, 2017 [14] | Canada | 501 | 5832 | Pregnancy & < 21 months postpartum | Stage I II III IV | 20–45 | 5 | OS | paper | 1.11 | 0.86–1.45 | 9 | – | Year of diagnosis, age, tumour size, nodal status, oestrogen receptor status, progesterone receptor status, chemotherapy, radiotherapy, et al |

| Kim, 2017 [66] | Korea | 344 | 668 | Pregnancy & < 12 months postpartum | Stage 0 I II III IV, Grade I II III | 20–45 | 10 | OS | indirect | 1.85 | 1.28–2.67 | 8 | Operation period, age, initial stage | – |

| Bae, 2018(1) [67] | Korea | 40 | 2770 | Pregnancy & < 12 months postpartum | Stage 0 I II III | 33.5 (27–40) | 5 | CSS | paper | 4.00 | 1.20–12.90 | 8 | – | Age, stage, chemotherapy |

| Bae, 2018(2) [68] | Korea | 411 | 83,381 | Pregnancy & < 12 months postpartum | Stage 0 I II III IV | 20–49 | 15 | OS | paper | 1.03 | 0.74–1.42 | 9 | – | Age at diagnosis, stage, high versus low/intermediate, luminal subtype, HER2 subtype, et al |

| Boudy, 2018-DFS [16] | France | 49 | 51 | Pregnancy | Grade I II III | < 46 | 5 | DFS | indirect | 1.19 | 0.75–1.91 | 8 | Propensity score | – |

| Boudy, 2018-CSS [16] | France | 49 | 51 | Pregnancy | Grade I II III | < 46 | 5 | CSS | indirect | 1.06 | 0.65–1.72 | 8 | – | |

| Johansson, 2018 [2] | Sweden | 778 | 1661 | Pregnancy & < 24 months postpartum | Stage 0 I II III IV | 15–44 | 10 | OS | indirect | 0.90 | 0.55–1.40 | 9 | – | Age, period, education, region, tumour characteristics, pathologic T stage, N stage, ER/PR |

| Chuang, 2018 [69] | China (Taiwan) | – | – | – | Stage I II III | 20–50 | > 10 | OS | paper | – | – | 9 | – | Age and year of diagnosis, stage, tumour size, positive lymph nodes, histological grading, treatments |

| Ploquin, 2018-OS [15] | France | 111 | 253 | Pregnancy | Stage 0 I II III IV | 22–46 | 5 | OS | paper | 1.10 | 0.67–1.79 | 8 | Age, clinical T stage, hormone receptor | Clinical nodal status, age |

| Ploquin, 2018-DFS [15] | France | 111 | 253 | Pregnancy | Stage 0 I II III IV | 22–46 | 5 | DFS | paper | 1.15 | 0.78–1.68 | 8 | ||

| Suleman, 2019-OS [70] | Saudi Arabia | 110 | 114 | Pregnancy | Stage I II III IV | 20–48 | > 10 | OS | indirect | 2.58 | 1.26–5.26 | 7 | Diagnosed year | – |

| Suleman, 2019-DFS [70] | Saudi Arabia | 110 | 114 | Pregnancy | Stage I II III IV | 20–48 | > 10 | DFS | indirect | 1.18 | 0.70–1.97 | 7 | – | |

| Choi, 2019 [17] | Korea | 63 | 3804 | Pregnancy & < 12 months postpartum | NA | < 50 | 10 | OS | paper | 1.52 | 0.82–2.83 | 8 | – | Histologic type, stage, ER, PR, age at diagnosis, Charlson comorbidity index |

BMI Body mass index, ER Oestrogen receptor, PR Progesterone receptor, HER-2 Human epidermal growth factor receptor-2

Overall survival (OS)

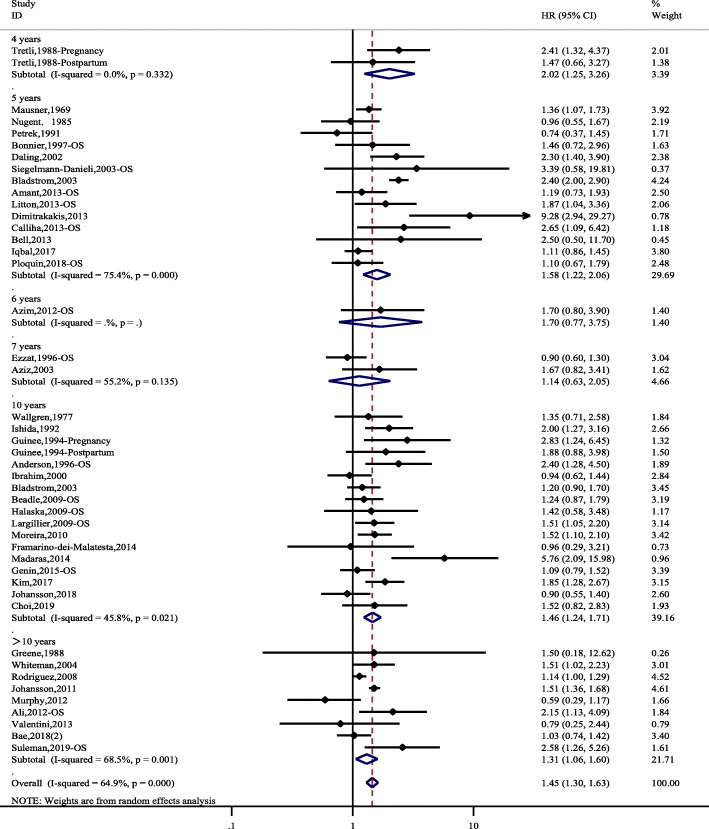

Forty-five studies comprising 6602 PABC patients and a total of 157,657 individuals were identified for the meta-analysis of OS. There was an overall increased risk of death for PABC patients compared to controls, with a pooled hazard ratio of 1.45 (95% CI 1.30–1.63). There was significant heterogeneity (I2 = 64.9, P<0.001). The subgroup analysis according to different follow-up durations (4 years, 5 years, 6 years, 7 years, 10 years and > 10 years) had similar results to the overall analysis (Fig. 2). However, the 6-year and 7-year OS, with few studies, showed nonsignificant results.

Fig. 2.

Hazard ratios and 95% CIs of studies included in the meta-analysis of OS

Disease-free survival (DFS)

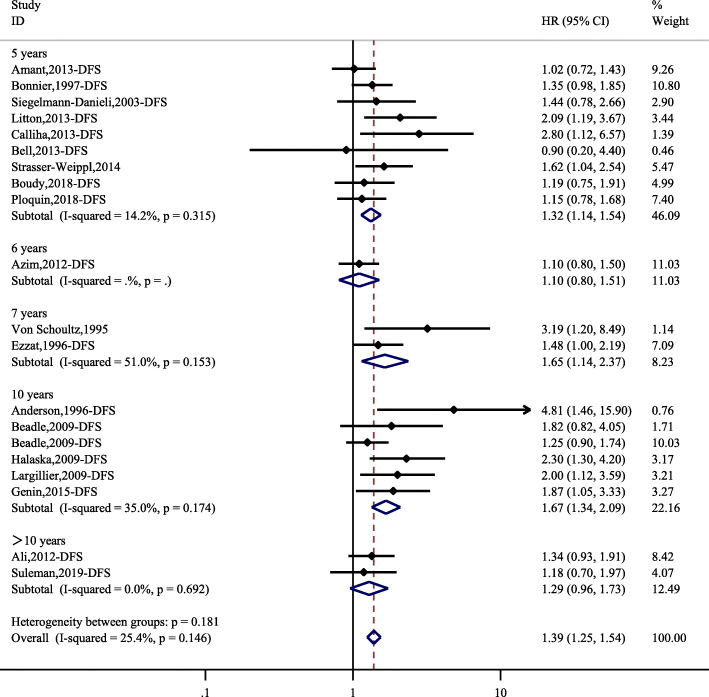

Twenty studies comprising 1786 PABC patients and a total of 9762 individuals were identified for the meta-analysis of DFS. The overall HR was 1.39 (95% CI, 1.25–1.54). There was no significant heterogeneity (I2 = 24.5, P = 0.146). The subgroup analysis according to different follow-up durations (5 years, 6 years, 10 years and > 10 years) had similar results as the overall analysis (Fig. 3). However, the 7-year DFS, with only 2 studies, showed nonsignificant results.

Fig. 3.

Hazard ratios and 95% CIs of studies included in the meta-analysis of DFS

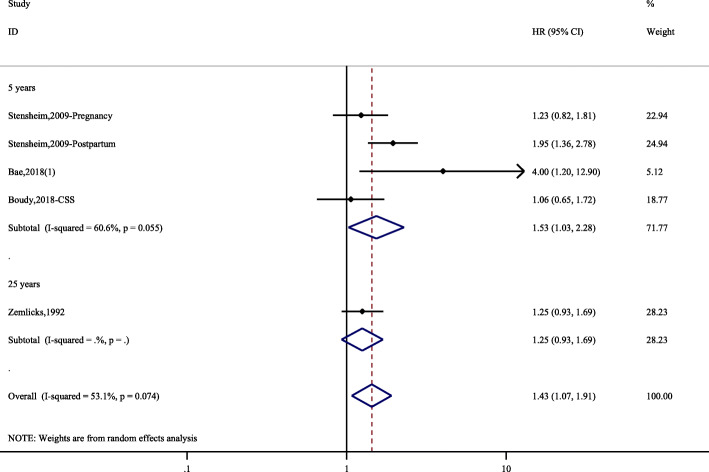

Cause-specific survival (CSS)

Only 6 studies provided information on CSS with 296 PABC patients and a total of 29,598 individuals. The overall HR was 1.40 (95% CI, 1.17–1.68). There was no significant heterogeneity (I2 = 53.1, P = 0.074). The subgroup analysis (5-year CSS) had similar results as the overall analysis (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4.

Hazard ratios and 95% CIs of studies included in the meta-analysis of CSS

Subgroup analyses

Several factors that may have induced differences in outcomes were investigated with subgroup analyses, including diagnosis time, PABC definition, geographic region, year of publication and estimation procedure for HR. The results consistently showed worse prognoses in women with PABC than in those with non-PABC, except for the subgroup based on PABC definition and year of publication (Table 2). It is worth noticing that the specific definition has varied and this variability led to diverse results. Studies published during the years 2000–2010 and 2011–2019 had a clear trend of poor prognoses, which was less apparent in those published before 2000. The pooled HR of DFS based on studies published before 2000 was 1.27 (95% CI, 0.97–1.72).

Table 2.

Subgroup analyses

| Subgroups | No. of Articles (No. of Studies) |

HR (95% CI) | Heterogeneity Test | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| I2 (%) | P-value | |||||

| All studies included | 54 (76) | – | – | – | ||

| Diagnosed time | During pregnancy | OS | 13 (14) | 1.46(1.12–1.90) | 73.6 | < 0.001 |

| DFS | 7 (7) | 1.30(1.11–1.53) | 26.3 | 0.228 | ||

| During postpartum period | OS | 13(13) | 1.97(1.67–2.33) | 49.0 | 0.023 | |

| DFS | 2(2) | 1.86(1.17–2.93) | 0.0 | 0.740 | ||

| PABC definition | Pregnancy & < 6 months postpartum | OS | 2(2) | 1.37(1.09–1.72) | 0.0 | 0.852 |

| Pregnancy & < 12 months postpartum | OS | 20(20) | 1.44(1.20–1.72) | 60.7 | < 0.001 | |

| DFS | 8(9) | 1.52(1.27–1.81) | 17.4 | 0.288 | ||

| Pregnancy & < 24 months postpartum | OS | 3(3) | 1.42(1.01–2.01) | 67.4 | 0.047 | |

| Pregnancy & < 60 months postpartum | OS | 3(3) | 1.48(0.90–2.44) | 65.2 | 0.057 | |

| Geographic region | Europe | OS | 15(17) | 1.53(1.26–1.86) | 71.1 | < 0.001 |

| DFS | 9(9) | 1.32(1.15–1.52) | 8.7 | 0.363 | ||

| North America | OS | 16(17) | 1.38 (1.17–1.63) | 53.2 | 0.005 | |

| DFS | 5(6) | 1.68(1.35–2.08) | 15.5 | 0.315 | ||

| Asia | OS | 9(9) | 1.42(1.09–1.85) | 60.0 | 0.010 | |

| Others | OS | 2(2) | 1.55(1.13–2.13) | 0.0 | 0.544 | |

| Year of publication | Before 2000 | OS | 11(13) | 1.46(1.18–1.82) | 45.4 | 0.038 |

| DFS | 3(3) | 1.27(0.97–1.72) | 50.7 | 0.107 | ||

| 2000–2010 | OS | 11(12) | 1.48(1.19–1.85) | 79.0 | < 0.001 | |

| DFS | 4(5) | 1.40(1.14–1.71) | 20.5 | 0.284 | ||

| 2011–2019 | OS | 20(20) | 1.43(1.20–1.72) | 62.7 | < 0.001 | |

| DFS | 11(11) | 1.50(1.29–1.76) | 11.5 | 0.334 | ||

| HR estimate | Paper report | OS | 24(25) | 1.42(1.22–1.65) | 73.1 | < 0.001 |

| DFS | 12(12) | 1.35(1.19–1.53) | 29.1 | 0.160 | ||

| Indirect | OS | 19(20) | 1.43(1.28–1.60) | 47.4 | 0.010 | |

| DFS | 7(8) | 1.48(1.22–1.79) | 24.7 | 0.232 | ||

Dose-response association between the time from the last pregnancy to breast cancer diagnosis and HR of overall mortality

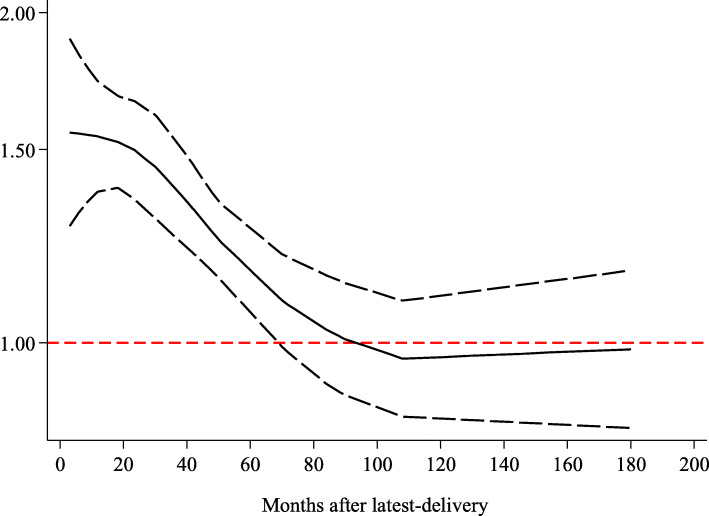

As the meta-analysis included studies reporting the HRs with their 95% CIs of overall mortality relating to three or more categories of time since the last pregnancy, all the studies were eligible to be included in the dose-response analysis. A total of ten studies were included in the dose-response meta-analysis, and nulliparous women were taken as the corresponding reference category (Table 3). The analysis of departure from linearity indeed indicated a nonlinear association between the time from the last delivery to breast cancer diagnosis and the hazard ratio of PABC overall mortality (P < 0.001). The nonlinear spline showed a decreasing trend. Compared to nulliparous women, the mortality was almost 60% higher in women with PABC diagnosed at 12 months after the last delivery (HR = 1.59, 95% CI 1.30–1.82), and the mortality was not significantly different at 70 months after the last delivery (HR = 1.14, 95% CI 0.99–1.25) (Fig. 5). These results showed a higher risk of death than that in nulliparous patients, suggesting that the definition of PABC should be extended to include patients diagnosed up to approximately 6 years postpartum (70 months since the last delivery) to capture the increased risk.

Table 3.

Characteristics of the studies included in the dose-analysis meta-analysis

| Study ID | Time point of breast cancer diagnosis | Time after last delivery (months) |

No. of participants | Adjusted HRa | 95% CI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Guinee, 1994 [30] | Postpartum 1–12 m | 1–12 | 40 | 1.88 | 0.88–3.98 |

| Postpartum 13–48 m | 13–48 | 51 | 1.09 | 0.54–2.19 | |

| Postpartum ≥49 m | ≥49 | 35 | 0.54 | 0.19–1.55 | |

| Olson, 1998 [35] | Postpartum < 24 m | 0–24 | 42 | 3.1 | 1.8–5.4 |

| Postpartum ≥24 m | ≥24 | 352 | 1.3 | 0.9–2.0 | |

| Reeves, 2000 [36] | Postpartum < 60 m | 0–60 | 67 | 1.56 | 1.01–2.42 |

| Postpartum 60–108 m | 60–108 | 80 | 0.88 | 0.58–1.32 | |

| Postpartum > 120 m | > 120 | 525 | 0.99 | 0.77–1.27 | |

| Daling, 2002 [38] | Postpartum < 24 m | 0–24 | 83 | 2.3 | 1.5–3.4 |

| Postpartum 24–60 m | 24–70 | 120 | 1.5 | 1.0–2.1 | |

| Postpartum > 60 m | > 70 | 661 | 1.2 | 0.9–1.6 | |

| Whiteman, 2004 [42] | Postpartum ≤12 m | 0–12 | 59 | 1.51 | 1.02–2.23 |

| Postpartum 13–48 m | 13–48 | 213 | 1.25 | 0.95–1.64 | |

| Postpartum > 48 m | > 48 | 1470 | 1.06 | 0.86–1.31 | |

| Phillips, 2009 [48] | Postpartum < 24 m | 0–24 | 133 | 2.75 | 1.98–3.83 |

| Postpartum 24–60 m | 24–60 | 231 | 2.2 | 1.65–2.94 | |

| Postpartum ≥72 m | ≥72 | 2067 | 0.98 | 0.79–1.22 | |

| Calliha, 2013 [58] | Postpartum < 60 m | 0–60 | 86 | 2.65 | 1.09–6.42 |

| Postpartum ≥60 m | ≥60 | 172 | 1.52 | 0.71–3.28 | |

| Nagatsuma, 2014 [63] | Postpartum ≤24 m | 0–24 | 37 | 2.19 | 1.05–4.56 |

| Postpartum 36–60 m | 36–60 | 59 | 1.49 | 0.79–2.83 | |

| Postpartum > 60 m | > 60 | 181 | 0.81 | 0.46–1.43 | |

| Johansson, 2018 [2] | Postpartum 0–6 m | 0–6 | 41 | 1.16 | 0.64–2.14 |

| Postpartum 6–12 m | 6–12 | 84 | 1.3 | 0.83–2.03 | |

| Postpartum 12–24 m | 12–24 | 194 | 1.01 | 0.70–1.46 | |

| Postpartum 24–60 m | 24–60 | 629 | 1.22 | 0.96–1.55 | |

| Postpartum 60–120 m | 60–120 | 1106 | 1.08 | 0.87–1.53 | |

| Postpartum > 120 m | > 120 | 1623 | 0.98 | 0.78–1.22 | |

| Chuang, 2018 [69] | Postpartum 0–12 m | 0–12 | 347 | 1.29 | 0.96–1.74 |

| Postpartum 13–24 m | 13–24 | 410 | 1.27 | 0.95–1.70 | |

| Postpartum 25–60 m | 25–60 | 1583 | 1.06 | 0.88–1.27 |

aCorresponding reference category: nulliparous

Fig. 5.

Dose-response relation between the time from the last delivery to breast cancer diagnosis and the HR of overall mortality

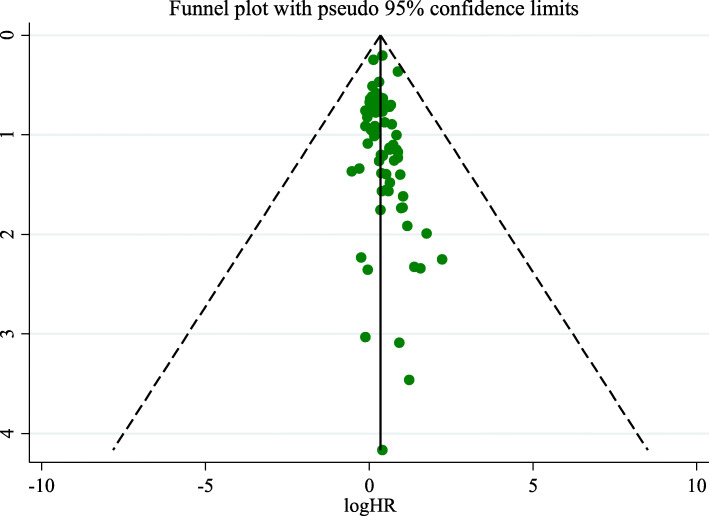

Publication Bias

As shown in Fig. 6, each point represents an independent study of the indicated association, and a visual inspection of the funnel plot did not suggest evidence of publication bias among the articles (Egger’s test, P = 0.451; Begg’s test, P = 0.077).

Fig. 6.

Funnel plot to explore the presence of publication bias

Discussion

We reviewed and meta-analyzed the existing scientific literature on the prognosis of PABC to draw a powerful conclusion that PABC is associated with a poor prognosis. Our results are consistent with those of the previous meta-analysis conducted in 2016 [13]. However, the negative effect on OS and DFS appears to be less pronounced in our study overall than in the previous meta-analysis. This is the largest and latest meta-analysis in this field. It included a larger number of participants, thus reducing the small-study effect to a great degree. The studies included in our meta-analysis were of relatively high quality. The mean Newcastle-Ottawa score of the studies was 7.2.

There are two explanations that may account for the results. On the one hand, mammary gland involution following pregnancy has been suggested to explain the poor prognosis [71]. Breast degeneration is the process of tissue remodelling, until wound healing, inflammatory bowel disease and immune infiltration reach a state indistinguishable from the non-productive breast [72, 73], which supposedly promotes tumour progression. On the other hand, pregnancy and breastfeeding lead to less timely detection and clinical examination. The delayed diagnosis allows more time for tumour growth, increasing the metastatic potential of the disease [52, 74]. Pregnancy also makes the treatment strategy more conservative to ensure the safety of the foetus [10, 75]. However, the exact reasons for the poor prognosis of PABC need to be explored in the future.

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first dose-response meta-analysis providing comprehensive insights into the association between the time from the last pregnancy to breast cancer diagnosis and the overall mortality of PABC. The scientific value of dose-response meta-analyses is higher than meta-analyses with exposure classified as two categories [20, 76]. Through the variance weighted least-squares regression with a random effects model, we found a nonlinear direct association between the time from the last pregnancy to breast cancer diagnosis and overall mortality. Compared with nulliparous women, the mortality was almost 60% higher in women with PABC diagnosed at 12 months after the last delivery, and the mortality had no significant difference at 70 months after the last delivery. We propose that the definition of PABC should include patients diagnosed up to at least 6 years postpartum to better delineate the increased risk imparted by a postpartum diagnosis. These findings also provide valuable insights into further research. Callihan’s cohort demonstrated that breast cancer patients diagnosed within 5 years postpartum have a significantly higher risk of metastasis and mortality than nulliparous patients [58]. Compared to that cohort, our dose-response meta-analysis provides a higher quality of evidence to expand the definition of PABC. Understanding the differences between breast cancers diagnosed during different times postpartum would better permit the translation of informative data from basic science and epidemiologic studies into the clinical care and treatment of breast cancer in young women.

The present meta-analysis has the following limitations that must be taken into account. First, if HRs and 95% CIs were not directly reported in the included studies, we estimated HRs from the crude data or Kaplan-Meier curves. This may cause bias without adjustment. However, we performed subgroup analysis based on the estimation procedure for HR. This analysis consistently showed a worse prognosis for women with PABC than for those with non-PABC. Second, the meta-analysis was based on data from observational studies; although most of the included studies adjusted for several relevant confounders (including age, year of diagnosis, tumour stage, axillary lymph node status, oestrogen receptor, hormonal receptor status, HER2 status, family history, etc.), residual confounding by other potential factors cannot be ruled out. Third, high between-study heterogeneity is another limitation of the current meta-analysis. This was likely due to significant differences in the sample sizes, definitions of PABC and/or treatment interventions. Last, the language of the studies was limited to English, which may result in potential language bias.

Conclusions

In summary, this meta-analysis suggests that PABC is associated with a poor prognosis for OS, DFS and CSS compared to non-PABC cases. The definition of PABC should be extended to include patients diagnosed up to approximately 6 years postpartum to capture the increased risk of death. Further long-term prospective cohort studies with larger sample sizes should be conducted to validate this article’s findings.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Abbreviations

- PABC

Pregnancy-associated breast cancer

- HR

Hazard ratio

- CI

Confidence interval

- VWLS

Variance weighted least-squares regression

- OS

Overall survival

- DFS

Disease-free survival

- CSS

Cause-specific survival

- PRISMA

Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses

- NOS

Newcastle-Ottawa Scale

- BMI

Body mass index

- ER

Oestrogen receptor

- PR

Progesterone receptor

- HER-2

Human epidermal growth factor receptor-2

Authors’ contributions

YZ and HJ designed the research study; CS and JX performed the literature search and statistical analysis; and CS interpreted the data and drafted the manuscript. Both YZ and HJ are corresponding authors. ZY, LL and FH critically revised the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Youth Talent Fund of the Second Hospital of Shandong University (2018YT26). The study funders had no role in the design, data acquisition, analyses, or data interpretation of this project.

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Yuan Zhang and Hongying Jia contributed equally to this work.

Contributor Information

Chunchun Shao, Email: ebmshao@qq.com.

Yuan Zhang, Email: ebmzhangyuan@yeah.net.

Hongying Jia, Email: jiahongying@sdu.edu.cn.

References

- 1.Bray F, Ferlay J, Soerjomataram I, Siegel RL, Torre LA, Jemal A. Global cancer statistics 2018: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin. 2018;68(6):394–424. doi: 10.3322/caac.21492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Johansson ALV, Andersson TM, Hsieh CC, Jirstrom K, Cnattingius S, Fredriksson I, Dickman PW, Lambe M. Tumor characteristics and prognosis in women with pregnancy-associated breast cancer. Int J Cancer. 2018;142(7):1343–1354. doi: 10.1002/ijc.31174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lee GE, Mayer EL, Partridge A. Prognosis of pregnancy-associated breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2017;163(3):417–421. doi: 10.1007/s10549-017-4224-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lyons TR, Schedin PJ, Borges VF. Pregnancy and breast cancer: when they collide. J Mammary Gland Biol Neoplasia. 2009;14(2):87–98. doi: 10.1007/s10911-009-9119-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lee YY, Roberts CL, Dobbins T, Stavrou E, Black K, Morris J, Young J. Incidence and outcomes of pregnancy-associated cancer in Australia, 1994-2008: a population-based linkage study. Bjog. 2012;119(13):1572–1582. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.2012.03475.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bae SY, Kim SJ, Lee J, Lee ES, Kim EK, Park HY, Suh YJ, Kim HK, You JY, Jung SP. Clinical subtypes and prognosis of pregnancy-associated breast cancer: results from the Korean breast Cancer society registry database. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2018;172(1):113–121. doi: 10.1007/s10549-018-4908-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Andersson TM, Johansson AL, Hsieh CC, Cnattingius S, Lambe M. Increasing incidence of pregnancy-associated breast cancer in Sweden. Obstet Gynecol. 2009;114(3):568–572. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e3181b19154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lambe M, Ekbom A. Cancers coinciding with childbearing: delayed diagnosis during pregnancy? Bmj. 1995;311(7020):1607–1608. doi: 10.1136/bmj.311.7020.1607. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Smith LH, Danielsen B, Allen ME, Cress R. Cancer associated with obstetric delivery: results of linkage with the California cancer registry. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2003;189(4):1128–1135. doi: 10.1067/s0002-9378(03)00537-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Case AS. Pregnancy-associated breast Cancer. Clin Obstet Gynecol. 2016;59(4):779–788. doi: 10.1097/GRF.0000000000000235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wohlfahrt J, Andersen PK, Mouridsen HT, Melbye M. Risk of late-stage breast cancer after a childbirth. Am J Epidemiol. 2001;153(11):1079–1084. doi: 10.1093/aje/153.11.1079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nichols HB, Schoemaker MJ, Cai J, Xu J, Wright LB, Brook MN, Jones ME, Adami HO, Baglietto L, Bertrand KA, et al. Breast Cancer risk after recent childbirth: a pooled analysis of 15 prospective studies. Ann Intern Med. 2019;170(1):22–30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 13.Hartman EK, Eslick GD. The prognosis of women diagnosed with breast cancer before, during and after pregnancy: a meta-analysis. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2016;160(2):347–360. doi: 10.1007/s10549-016-3989-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Iqbal J, Amir E, Rochon PA, Giannakeas V, Sun P, Narod SA. Association of the Timing of pregnancy with survival in women with breast Cancer. JAMA Oncol. 2017;3(5):659–665. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2017.0248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ploquin A, Pistilli B, Tresch E, Frenel JS, Lerebours F, Lesur A, Loustalot C, Bachelot T, Provansal M, Ferrero JM, et al. 5-year overall survival after early breast cancer diagnosed during pregnancy: a retrospective case-control multicentre French study. Eur J Cancer. 2018;95:30–37. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2018.02.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Boudy AS, Naoura I, Selleret L, Zilberman S, Gligorov J, Richard S, Thomassin-Naggara I, Chabbert-Buffet N, Ballester M, Bendifallah S, et al. Propensity score to evaluate prognosis in pregnancy-associated breast cancer: analysis from a French cancer network. Breast. 2018;40:10–15. doi: 10.1016/j.breast.2018.03.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Choi M, Han J, Yang BR, Jang MJ, Kim M, Kim TY, Im SA, Lee HB, Moon HG, Han W, et al. Prognostic impact of pregnancy in Korean patients with breast Cancer. Oncologist. 2019;24(12):e1268–76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 18.Rong Y, Chen L, Zhu T, Song Y, Yu M, Shan Z, Sands A, Hu FB, Liu L. Egg consumption and risk of coronary heart disease and stroke: dose-response meta-analysis of prospective cohort studies. BMJ (Clinical research ed) 2013;346:e8539. doi: 10.1136/bmj.e8539. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tierney JF, Stewart LA, Ghersi D, Burdett S, Sydes MR. Practical methods for incorporating summary time-to-event data into meta-analysis. Trials. 2007;8:16. doi: 10.1186/1745-6215-8-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Greenland S, Longnecker MP. Methods for trend estimation from summarized dose-response data, with applications to meta-analysis. Am J Epidemiol. 1992;135(11):1301–1309. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a116237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Witte JS, Greenland S. A nested approach to evaluating dose-response and trend. Ann Epidemiol. 1997;7(3):188–193. doi: 10.1016/s1047-2797(96)00159-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mausner JS, Shimkin MB, Moss NH, Rosemond GP. Cancer of the breast in Philadelphia hospitals 1951-1964. Cancer. 1969;23(2):260–274. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(196902)23:2<260::aid-cncr2820230203>3.0.co;2-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wallgren A, Silfversward C, Hultborn A. Carcinoma of the breast in women under 30 years of age: a clinical and histopathological study of all cases reported as carcinoma to the Swedish Cancer registry, 1958-1968. Cancer. 1977;40(2):916–923. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(197708)40:2<916::aid-cncr2820400248>3.0.co;2-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nugent P, O'Connell TX. Breast cancer and pregnancy. Arch Surg. 1985;120(11):1221–1224. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.1985.01390350007001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tretli S, Kvalheim G, Thoresen S, Host H. Survival of breast cancer patients diagnosed during pregnancy or lactation. Br J Cancer. 1988;58(3):382–384. doi: 10.1038/bjc.1988.224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Greene FL. Gestational breast cancer: a ten-year experience. South Med J. 1988;81(12):1509–1511. doi: 10.1097/00007611-198812000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Petrek JA, Dukoff R, Rogatko A. Prognosis of pregnancy-associated breast cancer. Cancer. 1991;67(4):869–872. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19910215)67:4<869::aid-cncr2820670402>3.0.co;2-q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zemlickis D, Lishner M, Degendorfer P, Panzarella T, Burke B, Sutcliffe SB, Koren G. Maternal and fetal outcome after breast cancer in pregnancy. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1992;166(3):781–787. doi: 10.1016/0002-9378(92)91334-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ishida T, Yokoe T, Kasumi F, Sakamoto G, Makita M, Tominaga T, Simozuma K, Enomoto K, Fujiwara K, Nanasawa T, et al. Clinicopathologic characteristics and prognosis of breast cancer patients associated with pregnancy and lactation: analysis of case-control study in Japan. Jpn J Cancer Res. 1992;83(11):1143–1149. doi: 10.1111/j.1349-7006.1992.tb02737.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Guinee VF, Olsson H, Moller T, Hess KR, Taylor SH, Fahey T, Gladikov JV, van den Blink JW, Bonichon F, Dische S, et al. Effect of pregnancy on prognosis for young women with breast cancer. Lancet. 1994;343(8913):1587–1589. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(94)93054-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.von Schoultz E, Johansson H, Wilking N, Rutqvist LE. Influence of prior and subsequent pregnancy on breast cancer prognosis. J Clin Oncol. 1995;13(2):430–434. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1995.13.2.430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ezzat A, Raja MA, Berry J, Zwaan FE, Jamshed A, Rhydderch D, Rostom A, Bazarbashi S. Impact of pregnancy on non-metastatic breast cancer: a case control study. Clin Oncol (R Coll Radiol) 1996;8(6):367–370. doi: 10.1016/s0936-6555(96)80081-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Anderson BO, Petrek JA, Byrd DR, Senie RT, Borgen PI. Pregnancy influences breast cancer stage at diagnosis in women 30 years of age and younger. Ann Surg Oncol. 1996;3(2):204–211. doi: 10.1007/BF02305802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bonnier P, Romain S, Dilhuydy JM, Bonichon F, Julien JP, Charpin C, Lejeune C, Martin PM, Piana L. Influence of pregnancy on the outcome of breast cancer: a case-control study. Societe Francaise de Senologie et de Pathologie Mammaire study group. Int J Cancer. 1997;72(5):720–727. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0215(19970904)72:5<720::aid-ijc3>3.0.co;2-u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Olson SH, Zauber AG, Tang J, Harlap S. Relation of time since last birth and parity to survival of young women with breast cancer. Epidemiology. 1998;9(6):669–671. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Reeves GK, Patterson J, Vessey MP, Yeates D, Jones L. Hormonal and other factors in relation to survival among breast cancer patients. Int J Cancer. 2000;89(3):293–299. doi: 10.1002/1097-0215(20000520)89:3<293::aid-ijc13>3.0.co;2-r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ibrahim EM, Ezzat AA, Baloush A, Hussain ZH, Mohammed GH. Pregnancy-associated breast cancer: a case-control study in a young population with a high-fertility rate. Med Oncol. 2000;17(4):293–300. doi: 10.1007/BF02782194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Daling JR, Malone KE, Doody DR, Anderson BO, Porter PL. The relation of reproductive factors to mortality from breast cancer. Cancer Epidemiol Biomark Prev. 2002;11(3):235–241. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Aziz S, Pervez S, Khan S, Siddiqui T, Kayani N, Israr M, Rahbar M. Case control study of novel prognostic markers and disease outcome in pregnancy/lactation-associated breast carcinoma. Pathol Res Pract. 2003;199(1):15–21. doi: 10.1078/0344-0338-00347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Siegelmann-Danieli N, Tamir A, Zohar H, Papa MZ, Chetver LL, Gallimidi Z, Stein ME, Kuten A. Breast cancer in women with recent exposure to fertility medications is associated with poor prognostic features. Ann Surg Oncol. 2003;10(9):1031–1038. doi: 10.1245/aso.2003.03.068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Bladstrom A, Anderson H, Olsson H. Worse survival in breast cancer among women with recent childbirth: results from a Swedish population-based register study. Clin Breast Cancer. 2003;4(4):280–285. doi: 10.3816/cbc.2003.n.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Whiteman MK, Hillis SD, Curtis KM, McDonald JA, Wingo PA, Marchbanks PA. Reproductive history and mortality after breast cancer diagnosis. Obstet Gynecol. 2004;104(1):146–154. doi: 10.1097/01.AOG.0000128173.01611.ff. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Rodriguez AO, Chew H, Cress R, Xing G, McElvy S, Danielsen B, Smith L. Evidence of poorer survival in pregnancy-associated breast cancer. Obstet Gynecol. 2008;112(1):71–78. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e31817c4ebc. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Stensheim H, Moller B, van Dijk T, Fossa SD. Cause-specific survival for women diagnosed with cancer during pregnancy or lactation: a registry-based cohort study. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27(1):45–51. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.17.4110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Beadle BM, Woodward WA, Middleton LP, Tereffe W, Strom EA, Litton JK, Meric-Bernstam F, Theriault RL, Buchholz TA, Perkins GH. The impact of pregnancy on breast cancer outcomes in women<or=35 years. Cancer. 2009;115(6):1174–1184. doi: 10.1002/cncr.24165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Halaska MJ, Pentheroudakis G, Strnad P, Stankusova H, Chod J, Robova H, Petruzelka L, Rob L, Pavlidis N. Presentation, management and outcome of 32 patients with pregnancy-associated breast cancer: a matched controlled study. Breast J. 2009;15(5):461–467. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-4741.2009.00760.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Largillier R, Savignoni A, Gligorov J, Chollet P, Guilhaume MN, Spielmann M, Luporsi E, Asselain B, Coudert B, Namer M. Prognostic role of pregnancy occurring before or after treatment of early breast cancer patients aged <35 years: a GET(N) a working group analysis. Cancer. 2009;115(22):5155–5165. doi: 10.1002/cncr.24608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Phillips KA, Milne RL, West DW, Goodwin PJ, Giles GG, Chang ET, Figueiredo JC, Friedlander ML, Keegan TH, Glendon G, et al. Prediagnosis reproductive factors and all-cause mortality for women with breast cancer in the breast cancer family registry. Cancer Epidemiol Biomark Prev. 2009;18(6):1792–1797. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-08-1014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Moreira WB, Brandao EC, Soares AN, Lucena CE, Antunes CM. Prognosis for patients diagnosed with pregnancy-associated breast cancer: a paired case-control study. Sao Paulo Med J. 2010;128(3):119–124. doi: 10.1590/S1516-31802010000300003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Johansson AL, Andersson TM, Hsieh CC, Cnattingius S, Lambe M. Increased mortality in women with breast cancer detected during pregnancy and different periods postpartum. Cancer Epidemiol Biomark Prev. 2011;20(9):1865–1872. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-11-0515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Murphy CG, Mallam D, Stein S, Patil S, Howard J, Sklarin N, Hudis CA, Gemignani ML, Seidman AD. Current or recent pregnancy is associated with adverse pathologic features but not impaired survival in early breast cancer. Cancer. 2012;118(13):3254–3259. doi: 10.1002/cncr.26654. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Azim HA, Jr, Santoro L, Russell-Edu W, Pentheroudakis G, Pavlidis N, Peccatori FA. Prognosis of pregnancy-associated breast cancer: a meta-analysis of 30 studies. Cancer Treat Rev. 2012;38(7):834–842. doi: 10.1016/j.ctrv.2012.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Ali SA, Gupta S, Sehgal R, Vogel V. Survival outcomes in pregnancy associated breast cancer: a retrospective case control study. Breast J. 2012;18(2):139–144. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-4741.2011.01201.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Amant F, von Minckwitz G, Han SN, Bontenbal M, Ring AE, Giermek J, Wildiers H, Fehm T, Linn SC, Schlehe B, et al. Prognosis of women with primary breast cancer diagnosed during pregnancy: results from an international collaborative study. J Clin Oncol. 2013;31(20):2532–2539. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2012.45.6335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Litton JK, Warneke CL, Hahn KM, Palla SL, Kuerer HM, Perkins GH, Mittendorf EA, Barnett C, Gonzalez-Angulo AM, Hortobagyi GN, et al. Case control study of women treated with chemotherapy for breast cancer during pregnancy as compared with nonpregnant patients with breast cancer. Oncologist. 2013;18(4):369–376. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.2012-0340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Valentini A, Lubinski J, Byrski T, Ghadirian P, Moller P, Lynch HT, Ainsworth P, Neuhausen SL, Weitzel J, Singer CF, et al. The impact of pregnancy on breast cancer survival in women who carry a BRCA1 or BRCA2 mutation. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2013;142(1):177–185. doi: 10.1007/s10549-013-2729-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Dimitrakakis C, Zagouri F, Tsigginou A, Marinopoulos S, Sergentanis TN, Keramopoulos A, Zografos GC, Ampela K, Mpaltas D, Papadimitriou C, et al. Does pregnancy-associated breast cancer imply a worse prognosis? A matched case-case study. Breast Care (Basel) 2013;8(3):203–207. doi: 10.1159/000352093. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Callihan EB, Gao D, Jindal S, Lyons TR, Manthey E, Edgerton S, Urquhart A, Schedin P, Borges VF. Postpartum diagnosis demonstrates a high risk for metastasis and merits an expanded definition of pregnancy-associated breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2013;138(2):549–559. doi: 10.1007/s10549-013-2437-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Bell RJ, Fradkin P, Parathithasan N, Robinson PJ, Schwarz M, Davis SR. Pregnancy-associated breast cancer and pregnancy following treatment for breast cancer, in a cohort of women from Victoria, Australia, with a first diagnosis of invasive breast cancer. Breast. 2013;22(5):980–985. doi: 10.1016/j.breast.2013.05.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Moller H, Purushotham A, Linklater KM, Garmo H, Holmberg L, Lambe M, Yallop D, Devereux S. Recent childbirth is an adverse prognostic factor in breast cancer and melanoma, but not in Hodgkin lymphoma. Eur J Cancer. 2013;49(17):3686–3693. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2013.06.047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Framarino-Dei-Malatesta M, Piccioni MG, Brunelli R, Iannini I, Cascialli G, Sammartino P. Breast cancer during pregnancy: a retrospective study on obstetrical problems and survival. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2014;173:48–52. doi: 10.1016/j.ejogrb.2013.11.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Madaras L, Kovacs KA, Szasz AM, Kenessey I, Tokes AM, Szekely B, Baranyak Z, Kiss O, Dank M, Kulka J. Clinicopathological features and prognosis of pregnancy associated breast cancer - a matched case control study. Pathol Oncol Res. 2014;20(3):581–590. doi: 10.1007/s12253-013-9735-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Nagatsuma AK, Shimizu C, Takahashi F, Tsuda H, Saji S, Hojo T, Sugano K, Takeuchi M, Fujii H, Fujiwara Y. Impact of recent parity on histopathological tumor features and breast cancer outcome in premenopausal Japanese women. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2013;138(3):941–950. doi: 10.1007/s10549-013-2507-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Strasser-Weippl K, Ramchandani R, Fan L, Li J, Hurlbert M, Finkelstein D, Shao ZM, Goss PE. Pregnancy-associated breast cancer in women from Shanghai: risk and prognosis. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2015;149(1):255–261. doi: 10.1007/s10549-014-3219-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Genin AS, De Rycke Y, Stevens D, Donnadieu A, Langer A, Rouzier R, Lerebours F. Association with pregnancy increases the risk of local recurrence but does not impact overall survival in breast cancer: a case-control study of 87 cases. Breast. 2016;30:222–227. doi: 10.1016/j.breast.2015.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Kim YG, Jeon YW, Ko BK, Sohn G, Kim EK, Moon BI, Youn HJ, Kim HA. Clinicopathologic characteristics of pregnancy-associated breast Cancer: results of analysis of a Nationwide breast Cancer registry database. J Breast Cancer. 2017;20(3):264–269. doi: 10.4048/jbc.2017.20.3.264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Bae SY, Jung SP, Jung ES, Park SM, Lee SK, Yu JH, Lee JE, Kim SW, Nam SJ. Clinical characteristics and prognosis of pregnancy-associated breast Cancer: poor survival of luminal B subtype. Oncology (Switzerland) 2018;95(3):163–169. doi: 10.1159/000488944. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Bae SY, Kim KS, Kim JS, Lee SB, Park BW, Lee SW, Lee HJ, Kim HK, You JY, Jung SP. Neoadjuvant chemotherapy and prognosis of pregnancy-associated breast cancer: a time-trends study of the Korean breast cancer registry database. J Breast Cancer. 2018;21(4):425–432. doi: 10.4048/jbc.2018.21.e58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Chuang SC, Lin CH, Lu YS, Hsiung CA. Association of pregnancy and mortality in women diagnosed with breast cancer: a Nationwide population based study in Taiwan. Int J Cancer. 2018;143(10):2416–2424. doi: 10.1002/ijc.31777. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Suleman K, Osmani AH, Al Hashem H, Al Twegieri T, Ajarim D, Jastaniyah N, Al Khayal W, Al Malik O, Al Sayed A. Behavior and outcomes of pregnancy associated breast Cancer. Asian Pacific J Cancer Prev. 2019;20(1):135–138. doi: 10.31557/APJCP.2019.20.1.135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Jindal S, Gao D, Bell P, Albrektsen G, Edgerton SM, Ambrosone CB, Thor AD, Borges VF, Schedin P. Postpartum breast involution reveals regression of secretory lobules mediated by tissue-remodeling. Breast Cancer Res. 2014;16(2):R31. doi: 10.1186/bcr3633. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Conklin MW, Eickhoff JC, Riching KM, Pehlke CA, Eliceiri KW, Provenzano PP, Friedl A, Keely PJ. Aligned collagen is a prognostic signature for survival in human breast carcinoma. Am J Pathol. 2011;178(3):1221–1232. doi: 10.1016/j.ajpath.2010.11.076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.O'Brien J, Lyons T, Monks J, Lucia MS, Wilson RS, Hines L, Man YG, Borges V, Schedin P. Alternatively activated macrophages and collagen remodeling characterize the postpartum involuting mammary gland across species. Am J Pathol. 2010;176(3):1241–1255. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2010.090735. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Al-Sehli H, D'Souza R, Maxwell C. Breast cancer in pregnancy: a retrospective cohort study. Obstet Gynecol. 2018;131:135S. doi: 10.1159/000493128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Martinez MT, Bermejo B, Hernando C, Gambardella V, Cejalvo JM, Lluch A. Breast cancer in pregnant patients: a review of the literature. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2018;230:222–227. doi: 10.1016/j.ejogrb.2018.04.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Berlin JA, Longnecker MP, Greenland S. Meta-analysis of epidemiologic dose-response data. Epidemiology (Cambridge, Mass) 1993;4(3):218–228. doi: 10.1097/00001648-199305000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.