Abstract

Peroxyzymes simply use H2O2 as a cosubstrate to oxidize a broad range of inert C–H bonds. The lability of many peroxyzymes against H2O2 can be addressed by a controlled supply of H2O2, ideally in situ. Here, we report a simple, robust, and water-soluble anthraquinone sulfonate (SAS) as a promising organophotocatalyst to drive both haloperoxidase-catalyzed halogenation and peroxygenase-catalyzed oxyfunctionalization reactions. Simple alcohols, methanol in particular, can be used both as a cosolvent and an electron donor for H2O2 generation. Very promising turnover numbers for the biocatalysts of up to 318 000 have been achieved.

Keywords: photobiocatalysis, peroxyzymes, halogenation, hydroxylation, H2O2 generation

Introduction

Peroxyzymes (i.e., oxidative enzymes utilizing H2O2 as a stoichiometric oxidant) are on the rise. As biocatalysts, they entail the benefits associated with enzymes such as operating under mild (i.e., energy-saving) reaction conditions and often exhibiting superb regio-, chemo-, and enantio-selectivity. Compared to other oxidizing enzymes such as P450 monooxygenases, they excel by their simplicity in terms of oxygen activation.1 Instead of relying on complex enzyme cascades for the activation of molecular oxygen, peroxyzymes use already activated oxygen in the form of H2O2.2 Nevertheless, in most cases, simple bulk addition of all H2O2 is not advisable because of undesired side reactions and/or limited stability of biocatalysts against H2O2. Slow, continuous, or portion-wise supply of H2O2 is one alternative to maintain overall low concentrations of H2O2 but leads to significant dilution effects. Also, so-called “hot spots” of locally high H2O2 concentrations at the entry point of the stock solution into the reaction medium eventually inactivate the biocatalysts. Finally, especially in the case of hypohalite-forming enzymes (vide infra), excess H2O2 is wasted in a futile disproportionation reaction yielding H2O and 1O2.3,4 The latter may also be expected to lead to undesired side reactions. Therefore, in situ generation of H2O2 from O2 has emerged as a viable alternative.2 A broad range of enzymatic, electrochemical, and chemical in situ H2O2 generation systems have been proposed in the past few years. Photochemical approaches for the in situ reduction of O2 to H2O2 are attractive because they also enable using sacrificial electron donors such as EDTA5,6 or simple alcohols.7 Enzymatic H2O2 generation methods are more restricted in terms of sacrificial electron donors that can be used.8−10 Furthermore, combining photocatalysis with biocatalysis offers new possibilities for organic synthesis ranging from new regeneration approaches for cofactor-dependent enzymes,11−25 photoenzymatic cascades,26 and “new to nature” reactions catalyzed by photoexcited enzymes.27−32 Yet, the combination of photocatalysis with biocatalysis is not always unproblematic due to issues of photobleaching33 and formation of reactive oxygen species.34−36

Therefore, we became interested in the photocatalyst sodium anthraquinone sulfonate (SAS) for the oxidation of small sacrificial electron donors such as methanol37,38 and reductive activation of ambient O2 to H2O2. Compared to established heterogeneous photocatalysts,7,39 SAS is homogeneously dissolved in the reaction medium, which may alleviate the sluggish reaction kinetics by eliminating diffusion limitations of the heterogeneous photocatalysts. Furthermore, the mechanism of anthraquinone-mediated oxygen activation40 does not involve long-lived radical species, which in previous studies have been observed to impair the stability of the biocatalysts used. SAS has also been studied extensively as a photocatalyst for aerobic oxidation of a broad range of different alcohols using molecular oxygen as a stoichiometric electron acceptor (yielding H2O2 as byproduct).37,41−43

We, therefore, decided to evaluate SAS-catalyzed oxidation of simple alcohols to promote peroxyzyme-catalyzed oxidation reactions. As the first model enzyme, we used vanadium-dependent chloroperoxidase from Curvularia inaequalis (CiVCPO).4,34,44−53CiVCPO oxidizes Cl–, Br–, and I– to the corresponding hypohalites, which then undergo spontaneous chemical oxidation and halogenation reactions. We envisioned a productive coupling of SAS-catalyzed H2O2 generation with CiVCPO-induced halogenation of thymol (Scheme 1).

Scheme 1. Photoenzymatic Halogenation Combining Photocatalytic In Situ Generation of H2O2 Via O2 Reduction in the Presence of Methanol to Drive CiVCPO-Initiated Halogenation of Thymol.

Upper: overall reaction, lower: dissection into photochemical H2O2 generation (blue) and chemoenzymatic halogenation of thymol (red).

Results and Discussion

For the first set of experiments, we chose methanol as a sacrificial electron donor. Due to the excellent solvent stability of the biocatalyst, we used 40% (v/v) of methanol in phosphate buffer (pH 6). Hence, methanol served two purposes, as a sacrificial electron donor and as a cosolvent for the hydrophobic thymol starting material. Illuminating SAS alone with the visible light in the presence of methanol and ambient air led to an accumulation of H2O2 in the reaction mixture (Figure S1). After approximately 5 h (ca. 2 mM H2O2), the H2O2 accumulation ceased, most likely reaching a steady state between SAS-mediated H2O2 formation and decomposition (vide infra).

Performing the same experiment albeit in the presence of CiVCPO and thymol, a linear product accumulated over more than 30 h, reaching more than 95% conversion of the starting material. Overall, 9.14 mM 4-bromothymol (1b) was produced with traces of the 2-bromo isomer (1a) and the dibromination product (2,4-dibromo thymol, 1c stemming from the sequential halogenation of the primary product 1a)49,54 (Figure 1a). On performing the experiment either in the darkness or in the absence of SAS (under otherwise identical conditions), no conversion of the starting material was observed. In the absence of CiVCPO, traces of 4-bromothymol were observed upon prolonged reaction times. We, hence, conclude that the reaction indeed proceeds via the sequence outlined in Scheme 1. Substitution of the phosphate buffer with Tris-HCl gave almost identical results (Table S1). Interestingly, under otherwise identical conditions, performing the experiment in sodium citrate buffer gave only poor results. Currently, we lack a plausible explanation for this observation.

Figure 1.

Halogenation of thymol by combining CiVCPO and visible light-driven in situ generation of H2O2 using SAS. (a) Conversion of thymol (1, ■) into 4-brominated thymol (1b, ⧫) in the presence of CiVCPO (100 nM) and SAS (0.5 mM), and control reactions in the dark (⧫) in the absence of CiVCPO (⧫) or SAS (⧫). (b) Influence of varied concentrations of SAS (⧫ = 0.25 mM, ● = 1 mM, and ▲ = 2 mM) and (c) CiVCPO on the reaction course. (d) Other cosolvent (as well as electron donor) investigated. Reaction conditions were as follows: [substrate] = 10 mM, [CiVCPO] = 25–100 nM, [SAS] = 0.5–2 mM, [NaBr] = 25 mM, pH 6.0 (NaPi buffer, 60 mM), 40% of cosolvent, and visible light illumination (λ > 400 nm). The concentration of methanol and formate was 100 mM. The yielded products were quantified by gas chromatography. Error bars represent the standard deviation of duplicate experiments.

Increasing the photocatalyst concentration from 0.25 to 2 mM increased the product (1b) formation rate from 0.48 to 0.66 mM h–1 (Figure 1b). The nonproportional increase of 1b may indicate a decreasing optical transparency of the reaction mixture and a resulting suboptimal illumination of the entire reaction mixture, and hence a suboptimal utilization of the photocatalysts. Similar effects have been observed in other photocatalytic systems such as algaeal fermentation. Increasing the photocatalyst concentration, however, also negatively influenced the overall selectivity of the reaction and significant amounts of the dibromination product (1c) accumulated in the reaction mixture. In general, upon prolonged reaction times (i.e., upon near-full conversion of the thymol starting material), 1b was further brominated to 1c (Figure S2). Similarly, using 1b as a starting material also led to the formation of 1c. The biocatalyst concentration had no significant influence on the overall product formation (Figure 1c). Together with the previous observation, this may indicate that H2O2 generation reaction was overall rate limiting. This assumption is supported by the almost linear correlation observed between the product formed and the intensity of the light source (Figure S3). Also, the wavelength had a significant influence on the overall productivity (Figure S4). Applying blue light gave higher product concentrations as compared to bathochrome green or red light, which we attribute to the different overlaps with the SAS absorption spectrum (Figure S5).

Next, we turned our attention to the concentration and nature of the sacrificial electron donor. Increasing the methanol concentration from 10% (v/v) to 30% (v/v) also resulted in an increased product accumulation (Figure S6). Further increase of the methanol concentration up to 70% (v/v) did not significantly influence the product formation (rate).

The system does not necessarily rely on methanol as also other alcohols such as ethanol and 2-propanol yielded promising results (Figure 1d). Noteworthy, the methanol oxidation products formaldehyde and formate were also oxidized at significant rates yielding H2O2, pointing toward triple oxidation of methanol to CO2. It is also possible to scale up the halogenation reaction to 100 mL, in which 967 mg (45% isolated yield) of halogenated thymol was obtained (for details, see the scaling-up experiments in the Supporting Information).

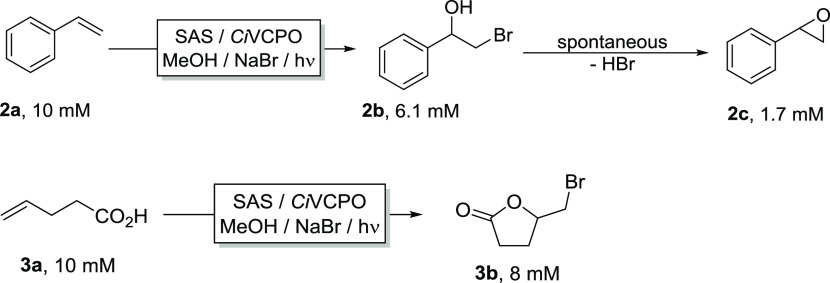

The synthetic scope of the new photoenzymatic reaction system was essentially identical to the traditional application of CiVCPO using stoichiometric H2O2 (Figures 2 and S7). Similar to previous reports,47 the hydroxybromination of styrene proceeded smoothly to the desired hydroxybromide (2b, 61%) and epoxide (2c, 17% originating from spontaneous oxirane formation). Also, the recently reported bromolactonization of 4-pentenoic acid gave the desired bromolactone (3b) in 80% yield.44,46

Figure 2.

Hydroxybromination and bomocyclization reactions by combining CiVCPO and visible light-driven in situ generation of H2O2 using SAS. Reaction conditions were as follows: [substrate] = 10 mM, [CiVCPO] = 50 nM, [SAS] = 0.5 mM, pH 6.0 (NaPi buffer, 60 mM), 40% of methanol, 32 h, and visible light illumination (λ > 400 nm). Experiments were performed in independent duplicates.

Overall, these experiments have demonstrated that CiVCPO-initiated bromofunctionalization reactions can be driven by photocatalytic H2O2 generation using SAS as a photocatalyst. In these experiments, CiVCPO performed up to 318 000 catalytic turnovers (on average 2.7 s–1 over 32 h). Compared to previous systems coupling CiVCPO to other heterogeneous H2O2-generating photocatalysts,34 the present system enabled significantly more robust production schemes (i.e., continuous product formation over at least 30 h). As CiVCPO itself is known to be highly robust against H2O2, we believe that this observation is in line with the hypothesized absence of reactive oxygen species such as hydroxyl radicals of superoxide.34 Interestingly enough, under the current conditions, bulk addition of H2O2 gave higher catalyst turnover numbers (Table S2). We attribute this to the insufficient light penetration into the reaction mixture and therefore suboptimal utilization of the photocatalyst. Future optimization will focus on alternative reactor concepts such as flow chemistry setups or internal illumination to alleviate this limitation.

To investigate whether somewhat less robust peroxyzymes can profit from the seemingly milder in situ H2O2 generation system based on SAS, we turned our attention to the recombinant, evolved peroxygenase from Agrocybe aegerita (rAaeUPO).55−58 From a synthetic point of view, rAaeUPO is very interesting as it catalyzes the specific oxyfunctionalization of a broad range of compounds.7,10,55−57,59−69 As a heme-dependent enzyme, it however, is also prone to irreversible oxidative inactivation by H2O2 or other reactive oxygen species. Therefore, we next performed an experiment on the hydroxylation of ethylbenzene using rAaeUPO and SAS-mediated H2O2 generation (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Hydroxylation of ethylbenzene into (R)–1-phenyl ethanol (⧫) and acetophenone (●) by combining rAaeUPO and visible light-driven in situ generation of H2O2 using SAS. Reaction conditions were as follows: [substrate] = 50 mM, [rAaeUPO] = 100 nM, [SAS] = 0.5 mM, 40% of methanol, and visible light illumination (λ > 400 nm). Experiments were performed as independent duplicates.

Pleasingly, the steady accumulation of the ethylbenzene oxyfunctionalization products ((R)-1-phenyl ethanol, 4b and acetophenone, 4c) was observed for at least 48 h, indicating a very high robustness of rAaeUPO under the reaction conditions chosen. In contrast to previous experiments on the rAaeUPO-catalyzed hydroxylation of ethylbenzene, we observed a low enantio-selectivity (34% ee) and a high degree of overoxidation, which can be attributed to SAS-catalyzed oxidation of the substrate 4a into 4b, and the enzymatic product 4b into 4c. Further optimization of the ratio of SAS to rAaeUPO alleviates this issue.

Again, we compared the performance of the biocatalyst using the proposed photochemical H2O2 generation system with bulk addition of H2O2 (Figure S8 and Table S2). In contrast to H2O2-tolerant CiVCPO, rAaeUPO performed significantly better under in situ H2O2 generation.

While overoxidation is undesired in the case of the stereoselective hydroxylation of ethylbenzene, it is desirable in the case of the oxidation of cyclohexane to cyclohexanone as the precursor for ε-caprolactame.70−75 As rAaeUPO has previously been reported to hydroxylate (cyclo)alkanes, we envisioned a photoenzymatic cascade to transform cyclohexane into the corresponding alcohol or ketone.76 In a first experiment, we used cyclohexane solubilized in an aqueous reaction buffer and the cosubstrate methanol in the presence of rAaeUPO (Table 1). Cyclohexane was converted at reasonable conversion (71%), yielding an approximate 6:1 ratio of cyclohexanone to cyclohexanol, which we attribute to the photocatalytic, SAS-mediated oxidation of cyclohexanol. This ratio, however, can be inverted using cyclohexane as a second phase under otherwise identical conditions (Table 1). Here, a significant proportion of the primarily formed cyclohexanol partitioned into the (catalyst-free) organic phase and thereby was not available for further SAS- or rAaeUPO-catalyzed further oxidation.

Table 1. Photoenzymatic Hydroxylation of Cyclohexane in a Two-Phase Reaction Systema.

| 5b [mM] | 5c [mM] | TON (SAS) | TON (rAaeUPO) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| monophase | 2.6 | 15.1 | 35 | 177 000 (71% conv.) |

| two-phase | 13.3 | 3.5 | 33 | 168 000 |

Reaction conditions: substrate/NaPi buffer (pH 6.0, 60 mM) phase ratio = 1:1 (v/v). In the aqueous phase: [rAaeUPO] = 100 nM, [SAS] = 0.5 mM, 40% of methanol, 32 h, visible light illumination (λ > 400 nm). For the monophase reaction, 25 mM of substrate was added.

In both cases, very good catalytic turnover of the biocatalysts above 150 000 and reasonable turnover numbers in the range of 35 for the photocatalyst were calculated.

The SAS-catalyzed aerobic “overoxidation” of cyclohexanol to cyclohexanone yields H2O2 as a byproduct, which itself can be used to promote the rAaeUPO-catalyzed hydroxylation of cyclohexane. This way, an overall aerobic oxidation of cyclohexane to cyclohexanone can be imagined (Figure 4). In a first experiment, we used 2 mM cyclohexanol to “kick-start” the photocatalytic generation of H2O2 and therewith the entire cascade.

Figure 4.

Self-sufficient, aerobic oxidation of cyclohexane to cyclohexanone. Reaction conditions were as follows: [cyclohexanol] = 2 mM, [cyclohexane] = 25 mM, [rAaeUPO] = 100 nM, [SAS] = 0.5 mM in NaPi buffer (pH 6.0, 60 mM). The values shown stem from one experiment (no duplicates).

Conclusions

In this work, we have expanded the scope of photogeneration of H2O2 to promote peroxyzyme-catalyzed halogenation and hydroxylation reactions. Water-soluble sodium anthraquinone sulfonate is a promising alternative to established heterogeneous photocatalysts. In contrast to the latter, SAS enables highly robust peroxyzyme reactions, and the turnover numbers for the two peroxyzymes used here (CiVCPO and rAaeUPO) reached 318 000 and 177 000, respectively. Most likely, this is due to the avoidance of oxygen radical species in the case of SAS-catalyzed H2O2 generation.

Furthermore, SAS also functions as an oxidation catalyst for peroxygenase-derived conversion of alcohol into ketones in a simple and self-sufficient manner. The catalytic activity of SAS itself is yet not optimal. Especially, the optical intransparency of the reaction mixtures suggests that light does not deeply penetrate the reaction mixtures. As a consequence, the majority of SAS present in the reaction mixtures is not illuminated and therefore remains “idle.” Further optimization will therefore focus on alternative reactor concepts with optimized surface to bulk ratios enabling more efficient utilization of the photocatalyst.

Experiment Section

Catalyst Preparation

The heterologous expression and purification of vanadium chloroperoxidase from C. inaequalis (CiVCPO) were performed according to reported procedures.77 The recombinant unspecific peroxygenase from A. aegerita (rAaeUPO) was produced and purified by following previous methods.57 The photocatalyst SAS was purchased from Sigma-Aldrich and used without extra treatment.

Photoenzymatic Halogenation Reactions

The photochemical enzymatic halogenation reactions using CiVCPO were performed at 30 °C in 1.0 mL of sodium phosphate buffer (NaPi, pH 6.0, 60 mM). Specifically, a stock solution (5 mM) of sodium anthraquinone sulfonate (SAS) in above NaPi buffer and thymol (100 mM) in methanol were first prepared. Hundred microliters of each stock solution was added to 795 μL of a premixed solution (300 μL methanol and 495 μL NaPi buffer) in a 4 mL glass vial. Afterward, CiVCPO was added (5 μL). In the final solution, the reaction conditions were as follows: [substrate] = 10 mM, [CiVCPO] = 50 nM, [NaBr] = 25 mM, [SAS] = 0.5 mM, pH 6.0 (NaPi buffer, 60 mM), and 40% of methanol in 1.0 mL. As the final step, the reaction vial was closed and exposed to visible light (Philips 7748XHP 150 W, white light bulb) under gentle magnetic stirring (200 rpm). At intervals, aliquots were withdrawn, extracted with ethyl acetate (containing 5 mM dodecane as an internal reference, extraction ratio 1:2), and analyzed by gas chromatography (SHIMADZU). All the above reactions were performed in independent duplicates.

Photoenzymatic Hydroxylation Reactions

The photochemical enzymatic hydroxylation reactions using rAaeUPO were performed using a very similar approach, as described for halogenation reactions. In a typical monophase reaction, a stock solution (5 mM) of sodium anthraquinone sulfonate (SAS) in NaPi buffer (pH 6.0, 60 mM) was first prepared. Hundred microliters of the stock solution was added to 895 μL of a premixed solution (400 μL methanol and 495 μL NaPi buffer) in a 4 mL glass vial. Afterward, the substrate (ethylbenzene or cyclohexane) rAaeUPO was added. The final reaction conditions were as follows: [substrate] = 50 mM, [rAaeUPO] = 100 nM, [SAS] = 0.5 mM, pH 6.0 (NaPi buffer, 60 mM), and 40% of methanol in 1.0 mL at 30 °C. The reaction vial was closed and exposed to visible light under gentle magnetic stirring (200 rpm).

In a typical two-phase reaction, approximately 500 μL of a premixed solution (200 μL methanol and 300 μL NaPi buffer) was added in a 4 mL glass vial. rAaeUPO was first added to this mixture, followed by addition of 500 μL of substrate (ethylbenzene or cyclohexane) as the organic phase. In the final solution, the reaction conditions were as follows: substrate/ NaPi buffer (pH 6.0, 60 mM) phase ratio = 1:1 (v/v). In the aqueous phase: [rAaeUPO] = 100 nM, [SAS] = 0.5 mM, 40% of methanol, 30 °C. All the above photoenzymatic hydroxylation reactions were performed in independent duplicates.

Scaling Up the Synthesis of 4-Br-Thymol

The scale-up reactions were performed in 100 mL for each batch (six batches in total). The reaction conditions were as follows: [substrate] = 15 mM, [CiVCPO] = 75 nM, [NaBr] = 25 mM, [SAS] = 0.5 mM, pH 6.0 (NaPi buffer, 60 mM), 40% methanol, and 30 °C. The mixture in a transparent DURAN bottle was placed (six batches at the same time) and stirred gently. The mixture was irradiated for 36 h at 30 °C under visible light. At the end of the reaction, the organic compounds were extracted using ethyl acetate (3×). The organic phase was combined and dried over anhydrous Na2SO4. After evaporating the ethyl acetate under reduced pressure, a yellowish oil was obtained. The crude product was purified by silica column using petroleum ether/ethyl acetate (40:2, v/v) as an eluent.

Acknowledgments

W.Z. gratefully acknowledges the financial support from the “Young Talent Support Plan” of Xi’an Jiaotong University (no. 7121191208). B.Y. acknowledges the financial support from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (no. 21706205), the China Postdoctoral Science Foundation (no. 2018M633518), and the Natural Science Foundation of Shaanxi Province (no. 2018JQ2062). F.H. acknowledges the financial support from the European Research Commission (ERC consolidator grant, no. 648026), the Netherlands Organisation for Scientific Research (VICI grant no. 724.014.003), and M.A. from the Spanish Government Project BIO2016-79106-R-Lignolution and the Comunidad de Madrid Synergy CAM project Y2018/BIO-4738-EVOCHIMERA-CM. We also thank Instrument Analysis Center of Xi'an Jiao Tong University for help with characterizations.

Supporting Information Available

The Supporting Information is available free of charge at https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/acscatal.0c01958.

Preparation of the enzymes, the photoenzymatic reaction setup, analytical data, and additional results (PDF)

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Supplementary Material

References

- Wang Y.; Lan D.; Durrani R.; Hollmann F. Peroxygenases En Route to Becoming Dream Catalysts. What Are the Opportunities and Challenges?. Curr. Opin. Chem. Biol. 2017, 37, 1–9. 10.1016/j.cbpa.2016.10.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burek B. O. O.; Bormann S.; Hollmann F.; Bloh J.; Holtmann D. Hydrogen Peroxide Driven Biocatalysis. Green Chem. 2019, 21, 3232–3249. 10.1039/C9GC00633H. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Renirie R.; Pierlot C.; Wever R.; Aubry J. M. Singlet Oxygenation in Microemulsion Catalysed by Vanadium Chloroperoxidase. J. Mol. Catal. B: Enzym. 2009, 56, 259–264. 10.1016/j.molcatb.2008.05.014. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Renirie R.; Pierlot C.; Aubry J.-M.; Hartog A. F.; Schoemaker H. E.; Alsters P. L.; Wever R. Vanadium Chloroperoxidase as a Catalyst for Hydrogen Peroxide Disproportionation to Singlet Oxygen in Mildly Acidic Aqueous Environment. Adv. Synth. Catal. 2003, 345, 849–858. 10.1002/adsc.200303008. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Churakova E.; Kluge M.; Ullrich R.; Arends I.; Hofrichter M.; Hollmann F. Specific Photobiocatalytic Oxyfunctionalization Reactions. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2011, 50, 10716–10719. 10.1002/anie.201105308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perez D. I.; Mifsud Grau M.; Arends I. W. C. E.; Hollmann F. Visible Light-driven and Chloroperoxidase-catalyzed Oxygenation Reactions. Chem. Commun. 2009, 44, 6848–6850. 10.1039/b915078a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang W.; Burek B. O.; Fernández-Fueyo E.; Alcalde M.; Bloh J. Z.; Hollmann F. Selective Activation of C-H bonds by Cascading Photochemistry with Biocatalysis. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2017, 129, 15451–15455. 10.1002/anie.201708668. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Willot S. J.-P.; Hoang M. D.; Paul C. E.; Alcalde M.; Arends I. W. C. E.; Bommarius A. S.; Bommarius B.; Hollmann F. FOx News: Towards Methanol-Driven Biocatalytic Oxyfunctionalisation Reactions. ChemCatChem 2020, 12, 2713–2716. 10.1002/cctc.202000197.. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ni Y.; Fernández-Fueyo E.; Baraibar A. G.; Ullrich R.; Hofrichter M.; Yanase H.; Alcalde M.; van Berkel W. J. H.; Hollmann F. Peroxygenase-Catalyzed Oxyfunctionalization Reactions Promoted by the Complete Oxidation of Methanol. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2016, 55, 798–801. 10.1002/anie.201507881. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Willot S. J. P.; Fernández-Fueyo E.; Tieves F.; Pesic M.; Alcalde M.; Arends I. W. C. E.; Park C. B.; Hollmann F. Expanding the Spectrum of Light-Driven Peroxygenase Reactions. ACS Catal. 2019, 9, 890–894. 10.1021/acscatal.8b03752. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feyza Özgen F.; Runda M. E.; Burek B. O.; Wied P.; Bloh J. Z.; Kourist R.; Schmidt S. Artificial Light-Harvesting Complexes Enable Rieske Oxygenase Catalyzed Hydroxylations in Non-Photosynthetic cells. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2020, 59, 3982–3987. 10.1002/anie.201914519. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Köninger K.; Gómez Baraibar Á.; Mügge C.; Paul C. E.; Hollmann F.; Nowaczyk M. M.; Kourist R. Recombinant Cyanobacteria for the Asymmetric Reduction of C=C Bonds Fueled by the Biocatalytic Oxidation of Water. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2016, 55, 5582–5585. 10.1002/anie.201601200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoschek A.; Bühler B.; Schmid A. Overcoming the Gas–Liquid Mass Transfer of Oxygen by Coupling Photosynthetic Water Oxidation with Biocatalytic Oxyfunctionalization. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2017, 56, 15146–15149. 10.1002/anie.201706886. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zachos I.; Gassmeyer S.; Bauer D.; Sieber V.; Hollmann F.; Kourist R. Photobiocatalytic Decarboxylation for Olefin Synthesis. Chem. Commun. 2015, 51, 1918–1921. 10.1039/C4CC07276F. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seel C. J.; Králík A.; Hacker M.; Frank A.; König B.; Gulder T. Atom-Economic Electron Donors for Photobiocatalytic Halogenations. ChemCatChem 2018, 10, 3960–3963. 10.1002/cctc.201800886. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rauch M.; Schmidt S.; Arends I. W. C. E.; Oppelt K.; Kara S.; Hollmann F. Photobiocatalytic Alcohol Oxidation using LED Light Sources. Green Chem. 2017, 19, 376–379. 10.1039/C6GC02008A. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mifsud M.; Gargiulo S.; Iborra S.; Arends I. W. C. E.; Hollmann F.; Corma A. Photobiocatalytic Chemistry of Oxidoreductases Using Water as the Electron Donor. Nat. Commun. 2014, 5, 3145 10.1038/ncomms4145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gargiulo S.; Arends I. W. C. E.; Hollmann F. A Photoenzymatic System for Alcohol Oxidation. ChemCatChem 2011, 3, 338–342. 10.1002/cctc.201000317. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Grau M. M.; van der Toorn J. C.; Otten L. G.; Macheroux P.; Taglieber A.; Zilly F. E.; Arends I. W. C. E.; Hollmann F. Photoenzymatic Reduction of C=C Double Bonds. Adv. Synth. Catal. 2009, 351, 3279–3286. 10.1002/adsc.200900560. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hollmann F.; Taglieber A.; Schulz F.; Reetz M. T. A Light-Driven Stereoselective Biocatalytic Oxidation. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2007, 46, 2903–2906. 10.1002/anie.200605169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoon J.; Lee S. H.; Tieves F.; Rauch M.; Hollmann F.; Park C. B. Light-Harvesting Dye-Alginate Hydrogel for Solar-Driven, Sustainable Biocatalysis of Asymmetric Hydrogenation. ACS Sustainable Chem. Eng. 2019, 7, 5632–5637. 10.1021/acssuschemeng.9b01075. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kuk S. K.; Gopinath K.; Singh R. K.; Kim T.-D.; Lee Y.; Choi W. S.; Lee J.-K.; Park C. B. NADH-Free Electroenzymatic Reduction of CO2 by Conductive Hydrogel-Conjugated Formate Dehydrogenase. ACS Catal. 2019, 9, 5584–5589. 10.1021/acscatal.9b00127. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kim J.; Park C. B. Shedding Light on Biocatalysis: Photoelectrochemical Platforms for Solar-driven Biotransformation. Curr. Opin. Chem. Biol. 2019, 49, 122–129. 10.1016/j.cbpa.2018.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee S. H.; Choi D. S.; Kuk S. K.; Park C. B. Photobiocatalysis: Activating Redox Enzymes by Direct or Indirect Transfer of Photoinduced Electrons. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2018, 57, 7958–7985. 10.1002/anie.201710070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee S. H.; Choi D. S.; Pesic M.; Woo Y.; Paul C.; Hollmann F.; Park C. B. Cofactor-Free, Direct Photoactivation of Enoate Reductases for Asymmetric Reduction of C=C Bonds. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2017, 56, 8681–8685. 10.1002/anie.201702461. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Litman Z. C.; Wang Y.; Zhao H.; Hartwig J. F. Cooperative Asymmetric Reactions combining Photocatalysis and Enzymatic Catalysis. Nature 2018, 560, 355–359. 10.1038/s41586-018-0413-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Black M. J.; Biegasiewicz K. F.; Meichan A. J.; Oblinsky D. G.; Kudisch B.; Scholes G. D.; Hyster T. K. Asymmetric Redox-neutral Radical Cyclization Catalysed by Flavin-dependent ‘Ene’-Reductases. Nat. Chem. 2020, 12, 71–75. 10.1038/s41557-019-0370-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sandoval B. A.; Kurtoic S. I.; Chung M. M.; Biegasiewicz K. F.; Hyster T. K. Photoenzymatic Catalysis Enables Radical-Mediated Ketone Reduction in Ene-Reductases. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2019, 58, 8714–8718. 10.1002/anie.201902005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biegasiewicz K. F.; Cooper S. J.; Emmanuel M. A.; Miller D. C.; Hyster T. K. Catalytic Promiscuity enabled by Photoredox Catalysis in Nicotinamide-Dependent Oxidoreductases. Nat. Chem. 2018, 10, 770–775. 10.1038/s41557-018-0059-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sandoval B. A.; Meichan A. J.; Hyster T. K. Enantioselective Hydrogen Atom Transfer: Discovery of Catalytic Promiscuity in Flavin-Dependent ‘Ene’-Reductases. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2017, 139, 11313–11316. 10.1021/jacs.7b05468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Emmanuel M. A.; Greenberg N. R.; Oblinsky D. G.; Hyster T. K. Accessing Non-natural Reactivity by Irradiating Nicotinamide-Dependent Enzymes with Light. Nature 2016, 540, 414–417. 10.1038/nature20569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim J.; Lee S. H.; Tieves F.; Paul C. E.; Hollmann F.; Park C. B. Nicotinamide Adenine Dinucleotide as a Photocatalyst. Sci. Adv. 2019, 5, eaax0501 10.1126/sciadv.aax0501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rauch M. C. R.; Huijbers M. M. E.; Pabst M.; Paul C. E.; Pesic M.; Arends I. W. C. E.; Hollmann F. Photochemical Regeneration of Flavoenzymes – An Old Yellow Enzyme Case-study. Biochim. Biophys. Acta, Proteins Proteomics 2020, 140303 10.1016/j.bbapap.2019.140303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang W.; Fernández-Fueyo E.; Ni Y.; van Schie M.; Gacs J.; Renirie R.; Wever R.; Mutti F. G.; Rother D.; Alcalde M.; Hollmann F. Selective Aerobic Oxidation Reactions using a Combination of Photocatalytic Water Oxidation and Enzymatic Oxyfunctionalizations. Nat. Catal. 2018, 1, 55–62. 10.1038/s41929-017-0001-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Schie M. M. C. H.; Younes S.; Rauch M.; Pesic M.; Paul C. E.; Arends I. W. C. E.; Hollmann F. Deazaflavins as Photocatalysts for the Direct Reductive Regeneration of Flavoenzymes. Mol. Catal. 2018, 452, 277–283. 10.1016/j.mcat.2018.04.015. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Höfler G. T.; Fernández-Fueyo E.; Pesic M.; Younes S. H.; Choi E.-G.; Kim Y. H.; Urlacher V. B.; Arends I. W. C. E.; Hollmann F. A Photoenzymatic NADH Regeneration System. ChemBioChem 2018, 19, 2344–2347. 10.1002/cbic.201800530. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang W.; Gacs J.; Arends I. W. C. E.; Hollmann F. Selective Photooxidation Reactions using Water Soluble Anthraquinone Photocatalysts. ChemCatChem 2017, 9, 3821–3826. 10.1002/cctc.201700779. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang W.; Bariotaki A.; Smonou I.; Hollmann F. Visible-Light-Driven Photooxidation of Alcohols Using Surface-Doped Graphitic Carbon Nitride. Green Chem. 2017, 19, 2096–2100. 10.1039/C7GC00539C. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- van Schie M.; Zhang W. Y.; Tieves F.; Choi D. S.; Park C. B.; Burek B. O.; Bloh J. Z.; Arends I.; Paul C. E.; Alcalde M.; Hollmann F. Cascading g-C3N4 and Peroxygenases for Selective Oxyfunctionalization Reactions. ACS Catal. 2019, 9, 7409–7417. 10.1021/acscatal.9b01341. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Nishimi T.; Kamachi T.; Kato K.; Kato T.; Yoshizawa K. Mechanistic Study on the Production of Hydrogen Peroxide in the Anthraquinone Process. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2011, 2011, 4113–4120. 10.1002/ejoc.201100300. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Peng Y.; Li D.; Fan J.; Xu W.; Xu J.; Yu H.; Lin X.; Wu Q. Enantiocomplementary C–H Bond Hydroxylation Combining Photo-Catalysis and Whole-Cell Biocatalysis in a One-Pot Cascade Process. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2020, 2020, 821–825. 10.1002/ejoc.201901682. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang W.; Gacs J.; Arends I. W. C. E.; Hollmann F. Selective Photooxidation Reactions using Water Soluble Anthraquinone Photocatalysts. ChemCatChem 2017, 9, 3821–3826. 10.1002/cctc.201700779. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu J.; Arkin M.; Peng Y.; Xu W.; Yu H.; Lin X.; Wu Q. Enantiocomplementary Decarboxylative Hydroxylation Combining Photocatalysis and Whole-Cell Biocatalysis in a One-Pot Cascade Process. Green Chem. 2019, 21, 1907–1911. 10.1039/C9GC00098D. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Younes S. H. H.; Tieves F.; Lan D.; Wang Y.; Süss P.; Brundiek H.; Wever R.; Hollmann F. Chemoenzymatic Halocyclization of γ,δ-Unsaturated Carboxylic Acids and Alcohols. ChemSusChem 2020, 13, 97–101. 10.1002/cssc.201902240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu X.; But A.; Wever R.; Hollmann F. Towards Preparative Chemoenzymatic Oxidative Decarboxylation of Glutamic acid. ChemCatChem 2020, 12, 2180–2183. 10.1002/cctc.201902194. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Höfler G. T.; But A.; Younes S. H. H.; Wever R.; Paul C. E.; Arends I. W. C. E.; Hollmann F. Chemoenzymatic Halocyclization of 4-Pentenoic acid at Preparative Scale. ACS Sustainable Chem. Eng. 2020, 8, 2602–2607. 10.1021/acssuschemeng.9b07494. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dong J. J.; Fernandez-Fueyo E.; Li J.; Guo Z.; Renirie R.; Wever R.; Hollmann F. Halofunctionalization of Alkenes by Vanadium Chloroperoxidase from Curvularia inaequalis. Chem. Commun. 2017, 53, 6207–6210. 10.1039/C7CC03368K. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fernández-Fueyo E.; Younes S. H. H.; Rootselaar Sv.; Aben R. W. M.; Renirie R.; Wever R.; Holtmann D.; Rutjes F. P. J. T.; Hollmann F. A Biocatalytic Aza-Achmatowicz Reaction. ACS Catal. 2016, 6, 5904–5907. 10.1021/acscatal.6b01636. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fernández-Fueyo E.; van Wingerden M.; Renirie R.; Wever R.; Ni Y.; Holtmann D.; Hollmann F. Chemoenzymatic Halogenation of Phenols by using the Haloperoxidase from Curvularia inaequalis. ChemCatChem 2015, 7, 4035–4038. 10.1002/cctc.201500862. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- ten Brink H. B.; Dekker H. L.; Shoemaker H. E.; Wever R. Oxidation Reactions Catalyzed by Vanadium Chloroperoxidase from Curvularia inaequalis. J. Inorg. Biochem. 2000, 80, 91–98. 10.1016/S0162-0134(00)00044-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Renirie R.; Hemrika W.; Piersma S. R.; Wever R. Cofactor and Substrate Binding to Vanadium Chloroperoxidase Determined by UV–VIS Spectroscopy and Evidence for High Affinity for Pervanadate. Biochem. 2000, 39, 1133–1141. 10.1021/bi9921790. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Schijndel J. W. P. M.; Barnett P.; Roelse J.; Vollenbroek E. G. M.; Wever R. The Stability and Steady-state Kinetics of Vanadium Chloroperoxidase from the Fungus Curvularia inequalis. Eur J Biochem 1994, 225, 151–157. 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1994.00151.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Schijndel J. W. P. M.; Vollenbroek E. G. M.; Wever R. The Chloroperoxidase from the Fungus Curvularia inaequalis - a Novel Vanadium Enzyme. Biochim. Biophys Acta 1993, 1161, 249–256. 10.1016/0167-4838(93)90221-C. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Getrey L.; Krieg T.; Hollmann F.; Schrader J.; Holtmann D. Enzymatic Halogenation of the Phenolic Monoterpenes Thymol and Carvacrol with Chloroperoxidase. Green Chem. 2014, 16, 1104–1108. 10.1039/C3GC42269K. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ullrich R.; Nüske J.; Scheibner K.; Spantzel J.; Hofrichter M. Novel Haloperoxidase from the Agaric Basidiomycete Agrocybe aegerita Oxidizes Aryl Alcohols and Aldehydes. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2004, 70, 4575–4581. 10.1128/AEM.70.8.4575-4581.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Molina-Espeja P.; Canellas M.; Plou F. J.; Hofrichter M.; Lucas F.; Guallar V.; Alcalde M. Synthesis of 1-Naphthol by a Natural Peroxygenase Engineered by Directed Evolution. ChemBioChem 2016, 17, 341–349. 10.1002/cbic.201500493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Molina-Espeja P.; Ma S.; Mate D. M.; Ludwig R.; Alcalde M. Tandem-yeast Expression System for Engineering and Producing Unspecific Peroxygenase. Enzyme Microb. Technol. 2015, 73–74, 29–33. 10.1016/j.enzmictec.2015.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Molina-Espeja P.; Garcia-Ruiz E.; Gonzalez-Perez D.; Ullrich R.; Hofrichter M.; Alcalde M. Directed Evolution of Unspecific Peroxygenase from Agrocybe aegerita. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2014, 80, 3496–3507. 10.1128/AEM.00490-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rauch M. C. R.; Tieves F.; Paul C. E.; Arends I. W.; Alcalde M.; Hollmann F. Peroxygenase-catalysed Epoxidation of Styrene Derivatives in Neat Reaction Media. ChemCatChem 2019, 11, 4519–4523. 10.1002/cctc.201901142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gomez de Santos P.; Cervantes F. V.; Tieves F.; Plou F. J.; Hollmann F.; Alcalde M. Benchmarking of Laboratory Evolved Unspecific Peroxygenases for the Synthesis of Human Drug Metabolites. Tetrahedron 2019, 75, 1827–1831. 10.1016/j.tet.2019.02.013. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Freakley S. J.; Kochius S.; van Marwijk J.; Fenner C.; Lewis R. J.; Baldenius K.; Marais S. S.; Opperman D. J.; Harrison S. T. L.; Alcalde M.; Smit M. S.; Hutchings G. J. A Chemo-Enzymatic Oxidation Cascade to Activate C–H bonds with in situ generated H2O2. Nature Commun. 2019, 10, 4178 10.1038/s41467-019-12120-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fernández-Fueyo E.; Ni Y.; Gomez Baraibar A.; Alcalde M.; van Langen L. M.; Hollmann F. Towards Preparative Peroxygenase-Catalyzed Oxyfunctionalization Reactions in Organic Media. J. Mol. Catal. B. Enzym. 2016, 134, 347–352. 10.1016/j.molcatb.2016.09.013. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kluge M.; Ullrich R.; Scheibner K.; Hofrichter M. Stereoselective Benzylic Hydroxylation of Alkylbenzenes and Epoxidation of Styrene Derivatives Catalyzed by the Peroxygenase of Agrocybe aegerita. Green Chem. 2012, 14, 440–446. 10.1039/C1GC16173C. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Poraj-Kobielska M.; Kinne M.; Ullrich R.; Scheibner K.; Kayser G.; Hammel K. E.; Hofrichter M. Preparation of Human Drug Metabolites using Fungal Peroxygenases. Biochem. Pharmacol. 2011, 82, 789–796. 10.1016/j.bcp.2011.06.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peter S.; Kinne M.; Wang X. S.; Ullrich R.; Kayser G.; Groves J. T.; Hofrichter M. Selective Hydroxylation of Alkanes by an Extracellular Fungal Peroxygenase. FEBS J. 2011, 278, 3667–3675. 10.1111/j.1742-4658.2011.08285.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barková K.; Kinne M.; Ullrich R.; Hennig L.; Fuchs A.; Hofrichter M. Regioselective Hydroxylation of diverse Flavonoids by an Aromatic Peroxygenase. Tetrahedron 2011, 67, 4874–4878. 10.1016/j.tet.2011.05.008. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kluge M.; Ullrich R.; Dolge C.; Scheibner K.; Hofrichter M. Hydroxylation of Naphthalene by Aromatic peroxygenase from Agrocybe aegerita proceeds via oxygen transfer from H2O2 and Intermediary Epoxidation. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2009, 81, 1071–1076. 10.1007/s00253-008-1704-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kinne M.; Poraj-Kobielska M.; Aranda E.; Ullrich R.; Hammel K. E.; Scheibner K.; Hofrichter M. Regioselective Preparation of 5-hydroxypropranolol and 4 ’-hydroxydiclofenac with a Fungal Peroxygenase. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2009, 19, 3085–3087. 10.1016/j.bmcl.2009.04.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kinne M.; Ullrich R.; Hammel K. E.; Scheibner K.; Hofrichter M. Regioselective Preparation of (R)-2-(4-hydroxyphenoxy)propionic acid with a Fungal Peroxygenase. Tetrahedron Lett. 2008, 49, 5950–5953. 10.1016/j.tetlet.2008.07.152. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wedde S.; Rommelmann P.; Scherkus C.; Schmidt S.; Bornscheuer U. T.; Liese A.; Gröger H. An Alternative Approach towards Poly-Caprolactone through a Chemoenzymatic Synthesis: Combined Hydrogenation, Bio-Oxidations and Polymerization without the Isolation of Intermediates. Green Chem. 2017, 19, 1286–1290. 10.1039/C6GC02529C. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Scherkus C.; Schmidt S.; Bornscheuer U. T.; Gröger H.; Kara S.; Liese A. Kinetic Insights into ε-Caprolactone Synthesis: Improvement of an Enzymatic Cascade Reaction. Biotechnol. Bioeng. 2017, 114, 1215–1221. 10.1002/bit.26258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt S.; Scherkus C.; Muschiol J.; Menyes U.; Winkler T.; Hummel W.; Gröger H.; Liese A.; Herz H. G.; Bornscheuer U. T. An Enzyme Cascade Synthesis of ε-Caprolactone and its Oligomers. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2015, 54, 2784–2787. 10.1002/anie.201410633. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Staudt S.; Burda E.; Giese C.; Müller C. A.; Marienhagen J.; Schwaneberg U.; Hummel W.; Drauz K.; Gröger H. Direktoxidation von Cycloalkanen zu Cycloalkanonen mit Sauerstoff in Wasser. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2013, 52, 2359–2363. 10.1002/anie.201204464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pennec A.; Hollmann F.; Smit M. S.; Opperman D. J. One-pot Conversion of Cycloalkanes to Lactones. ChemCatChem 2015, 7, 236–239. 10.1002/cctc.201402835. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Pennec A.; Jacobs C. L.; Opperman D. J.; Smit M. S. Revisiting Cytochrome P450-Mediated Oxyfunctionalization of Linear and Cyclic Alkanes. Adv. Synth. Catal. 2015, 357, 118–130. 10.1002/adsc.201400410. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Peter S.; Karich A.; Ullrich R.; Grobe G.; Scheibner K.; Hofrichter M. Enzymatic One-Pot Conversion of Cyclohexane into Cyclohexanone: Comparison of Four Fungal Peroxygenases. J. Mol. Catal. B: Enzym. 2014, 103, 47–51. 10.1016/j.molcatb.2013.09.016. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hasan Z.; Renirie R.; Kerkman R.; Ruijssenaars H. J.; Hartog A. F.; Wever R. Laboratory-Evolved Vanadium Chloroperoxidase exhibits 100-fold higher Halogenating Activity at Alkaline pH - Catalytic Effects from First and Second Coordination Sphere Mutations. J. Biol. Chem. 2006, 281, 9738–9744. 10.1074/jbc.M512166200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.