Abstract

Objectives:

This study aims to identify factors specific to the COVID-19 pandemic that affect resident physicians’ well-being, identify potential sources of anxiety, and assess for depression and stress among residents.

Methods:

A cross-sectional survey was performed in April 2020 that evaluated resident perceptions about COVID-19 pandemic, its impact on their personal lifestyle, and coping mechanisms adopted. The respondents also completed the Beck Depression Inventory-II (BDI-II) and Cohen Perceived Stress Scale (PSS-10).

Results:

Of 37 residents, 29 completed the survey for a response rate of 78%. We found that 50% of residents harbored increased anxiety due to the pandemic and reported fears of spreading disease. Factors that negatively impacted their well-being included social isolation from colleagues (78%), inability to engage in outdoor activities (82%), and social gatherings (86%). Residents expressed concern about the effect of the COVID-19 pandemic on their didactic education and clinical rotations. The mean PSS-10 total score was 17 (SD = 4.96, range = 0-33) and the mean BDI-II total score was 6.79 (SD = 6.00). Our residents adopted a number of coping mechanisms in response to COVID-19.

Conclusions:

We identified factors specific to the COVID-19 pandemic that adversely affected resident physician well-being. Trainees were concerned about the risk of developing COVID-19 and spreading this to their family. Residents also harbored anxiety regarding the effect of COVID-19 on their education. Lifestyle changes including social isolation also resulted in a negative effect on resident well-being. Developing strategies and resources directed to addressing these concerns may help support well-being and alleviate stress and anxiety.

Keywords: Coronavirus, medical education, mental health, physician, anxiety, health care provider

Introduction

The Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic has presented academic medical institutions with a unique set of challenges with respect to ensuring the safety and well-being of resident physicians. The Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME) has developed a conceptual framework for graduate medical education (GME) to function at their institutions but with an emphasis on resident physician safety. A number of operational changes, including social distancing and modified clinical and didactic training policies, have been implemented to mitigate the spread of COVID-19.1,2 The intent of these operational changes is to prevent the acquisition of the COVID-19 virus by resident physicians and to conserve the resident workforce.1,2 The effect of such interventions as well as consequences of the current crisis on the well-being and mental health of resident physicians is not known at this time. Although there has been a disproportionately lower number of cases in children when compared with adults, COVID-19-related pediatric disease has been rising and is associated with a wide array of presentations including myocardial disease, end organ damage, and death.3,4

Even before the COVID-19 pandemic, a robust body of work has demonstrated that resident physicians face burnout, depression, and anxiety during their training.5-7 Consequently, the potential for a decline in their well-being due to the COVID-19 pandemic is highly plausible. The psychological effect of the COVID-19 pandemic among health care personnel (HCP) was demonstrated by Lai et al,8 who found that HCP in China demonstrated symptoms of depression (50%), anxiety (44%), and distress (71%) due to the pandemic. In India, Chew et al9 reported that 12.4%, 17.1%, and 3.8% of HCP suffered from depression, anxiety, and stress, respectively. The HCP caring for patients with COVID-19 in Singapore10 also reported symptoms of depression (8.9%), anxiety (14.5%), and stress (6.6%).

Similarly, reviews of psychological sequelae among HCP revealed a number of negative emotional outcomes, including stress, depression, irritability, fear, and boredom associated with quarantine.11 Studies have described the impact of inadequate testing, limited treatment options, and insufficient personal protective equipment (PPE) on the psychological health of HCP.12-14 The HCP evaluated in these studies included physicians and nurses, and to our knowledge, similar studies about resident physicians have not been published and this is a gap of knowledge especially pertinent to the COVID-19 pandemic.15

As the COVID-19 pandemic continues to accelerate,16 residents will continue to be deployed as an essential part of the health care workforce.17 Gaining an understanding of the effect of the COVID-19 pandemic on resident physicians may provide leaders in GME with information to compile resources and strategies to support well-being during this unprecedented pandemic.

The purpose of this study was to determine factors specific to the COVID-19 pandemic that affected resident physician well-being, identify potential sources of anxiety, and assess for depression and stress among residents.

Methods

We performed a cross-sectional study to include 37 pediatric resident physicians training at the Valley Children’s Healthcare (VCH) Pediatric Residency program in Madera, CA. This study was conducted at VCH in April 2020 during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Study instruments

We developed a 45-question survey and made modifications based on feedback obtained from residency program leadership. The survey included demographic information, questions regarding the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on personal lifestyle, risk perceptions, self-rated mental health, and coping mechanisms. Using a 5-point Likert-type scale, respondents answered questions to determine the impact of missed training and loss of educational opportunities. The survey also included the Beck Depression Inventory-II (BDI-II) and Cohen Perceived Stress Scale (PSS-10).

Beck Depression Inventory

The BDI-II consists of 21 items that evaluate symptoms of depression occurring in the last 2 weeks. The scores range from 0 to 63 with a score of 0 to 13 as minimal depression, 14 to 19 as mild, 20 to 28 as moderate, and 29 to 63 as severe depression.18

Perceived Stress Scale

The 10-item Perceived Stress Scale (PSS-10), proposed by Cohen et al,19 and validated by Reis et al,20 is a self-reported measure of the degree of stressfulness of situations encountered in the last 30 days. The results range from 0 to 40 with a higher score indicating an increased perception of stress.

Study procedures

The survey was distributed anonymously via e-mail using an online survey website (SurveyMonkey™). Participants were given 1 week to complete the survey and residency leadership introduced the survey during virtual meetings with residents.

Descriptive analyses, counts, and percentages were completed for nominal variables, whereas mean values and standard deviations were performed for continuous variables. To analyze correlations between demographic indicators and COVID-19, chi-square, and Fisher exact tests were used. A p ⩽ 0.05 was considered significant. The data were analyzed using the Statistica software (StatSoft Inc., version 7.0). The study was approved by the VCH Institutional Review Board.

Results

Among the 37 resident physicians in our program, 29 of the 37 completed the survey for a response rate of 78%. Of the respondents, 62% were women, 76% were non-Hispanic, and 41% were white. Sixty-two percent of respondents were between 26 and 30 years of age and 41% were married or in a domestic partnership. Table 1 includes the demographics of our study population.

Table 1.

Demographics characteristics of pediatric resident physicians surveyed (N = 29).

| Characteristic | Total (N = 29) % (n) |

|---|---|

| Age | |

| 26-30 | 62 (18) |

| 31-35 | 35 (10) |

| 36-40 | 3 (1) |

| Sex | |

| Male | 38 (11) |

| Female | 62 (18) |

| Ethnicity | |

| Hispanic | 24 (7) |

| Non-Hispanic | 76 (22) |

| Race | |

| White | 41 (12) |

| African American | 0 (0) |

| Asian | 38 (11) |

| Other | 21 (6) |

| Level of training | |

| PGY-1 | 38 (11) |

| PGY-2 | 38 (11) |

| PGY-3 | 24 (7) |

| Living arrangement | |

| Living alone | 52 (15) |

| Living with partner | 24 (7) |

| Living with spouse and children | 14 (4) |

| Living with friends or roommates | 10 (3) |

| Marital status | |

| Single | 55 (16) |

| Married or domestic partnership | 41 (12) |

| Widowed/divorced/separated | 4 (1) |

Abbreviation: PGYs, postgraduate years.

Factors affecting resident well-being during COVID-19

Fifty percent of resident physician reported an increased level of anxiety as result of the COVID-19 pandemic. The majority of residents (64%) expressed concerns about the effect of the pandemic on their didactic education and on their clinical rotations (79%). Certain lifestyle changes due to the pandemic notably affected resident well-being. Eighty-two percent and 86% of residents reported that the inability to engage in outdoor activities and the inability to engage in social gatherings, respectively, were distressing. Similarly, 78% of residents stated that social isolation from colleagues and friends negatively impacted them. Eleven percent of trainees reported encountering food insecurity and 11% admitted to financial strain due to the COVID-19 pandemic.

Perceived risk of acquisition of disease and coping mechanisms

Forty-one percent of resident physicians stated that they perceived their risk of developing COVID-19 disease as “likely” or “extremely likely” but only 7% reported concerns regarding the possibility of developing a severe complication of COVID-19 infection such as pneumonia, hospitalization, or death. Nearly 50% of respondent harbored fears of spreading the virus to family members or friends and 49% were concerned about the potential for spreading the virus to patients. Sixty percent of our residents were concerned about the effect of limited PPE on their ability to provide care safely.

Coping mechanisms adopted by residents during the pandemic are described in Table 2. When asked to indicate “To what extent do you agree with the following statement,” 79% of residents “strongly agreed” or “agreed” with the statement; and “I have sought support from family and friends more frequently,” 82% “strongly agreed” or “agreed” that they sought support from their peer support system or colleagues. Although 58% of respondents were involved in measures to enhance well-being, nearly half were not satisfied with these measures.

Table 2.

Coping mechanism responses by resident physicians during the COVID-19 pandemic.

| Methods of coping | Strongly agree (%) | Agree (%) | Neutral (%) | Disagree (%) | Strongly disagree (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| I have been paying more attention to my mental well-being | 7 | 39 | 26 | 18 | 0 |

| I have been exercising more to ensure physical well-being | 11 | 18 | 21 | 29 | 21 |

| I have been washing my hands and disinfecting more frequently | 57 | 38 | 7 | 0 | 0 |

| I have been avoiding public places as much as possible | 50 | 49 | 4 | 4 | 0 |

| I have been buying larger quantities of household essentials and food items | 4 | 29 | 25 | 29 | 14 |

| I have been reaching out to family and friends more frequently | 29 | 50 | 11 | 11 | 0 |

| I have sought support from my peer support system/colleagues | 36 | 46 | 14 | 4 | 0 |

| I have sought support from my educational leadership directors | 25 | 46 | 18 | 11 | 0 |

Abbreviation: COVID-19, Coronavirus Disease 2019.

Depression and stress among residents during COVID-19 pandemic

Of our respondents, 21% displayed symptoms of mild depression and 7% displayed symptoms of moderate depression. According to the Beck Inventories, the mean BDI-II total score was 6.79 (SD = 6.00). The average BDI-II total score between postgraduate year (PGY)-1 (M = 7.80, SD = 7.50), PGY-2 (M = 5.73, SD = 4.65), and PGY-3 (M = 7.00 SD = 6.19) were not significantly different. Using the recommended cut-off score of 16,18 the proportion of probable depression was not significantly different in relation to sex or marital status.

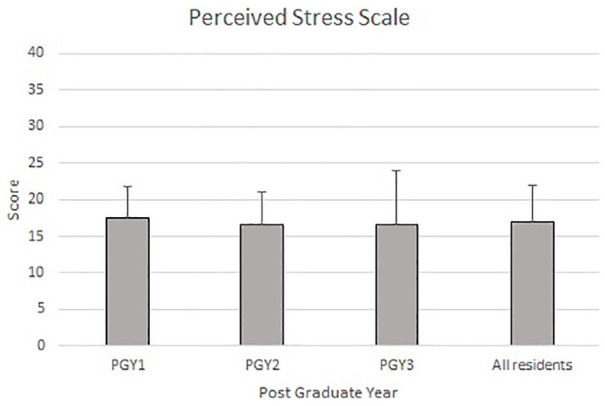

Thirty-nine percent of our residents acknowledged that their stress level was slightly higher than average and 35% reported that their stress level was much higher than average. For the total sample, the mean PSS-10 total score was 17 (SD = 4.96, range: 0-33), Factor 1 (“Negative”) score was 10.43 (SD = 4.22, range: 0-24), and Factor 2 (“Positive”) score was 6.57 (SD = 1.89, range: 0-16). Figures 1 and 2 show the scores of the PSS-10 and BDI-II by PGYs, respectively.

Figure 1.

Perceived Stress Score-10: Total, according to Resident Postgraduate Year

Figure 2.

Beck Depression Score: Total, according to Resident Postgraduate Year

Discussion

We identified factors specific to the COVID-19 pandemic that adversely affected resident physician well-being. In our study, nearly 50% of resident physicians harbored anxiety about acquiring COVID-19 and spreading the infection to family members and patients. Such concerns are not unfounded considering the morbidity and mortality of the disease among HCP in Italy21 and China.22 During the Ebola Virus Disease pandemic, Jalloh et al23 found that HCP suffered from post-traumatic stress disorder due to fears of infecting their family and patients. Similar concerns were reported during the 2009 H1N1 pandemic.24 The concern of spreading COVID-19 infection for health care workers may be linked with PPE availability. It is well known that the current supply of PPE may not be adequate to meet the projected demands and 60% of our residents also cited worry about institutional PPE availability and their ability to care for patients safely.8,25,26 Involving residents in communications with hospital administration about institutional PPE status may help allay anxieties regarding PPE supply. In centers wherein PPE supplies are limited, resident work tasks may be reassigned to focus on clinical areas of need. Kang et al27 established that HCP contaminate themselves frequently during PPE use, thereby increasing their risk for infection. Training regarding PPE donning and doffing in a simulated environment and use of competency checklists may help trainees feel safe when caring for patients.

Our study found that resident physicians harbored concerns about the effect of COVID-19 pandemic on their education. They reported that cancelation of research and educational presentations at national conferences affected their well-being. Professional organizations have created processes for residents to present their research in a virtual format to foster their educational experience. Encouraging residents to document their accepted research and educational presentations on their curriculum vitae as accepted, but “cancelled due to COVID-19” may prevent them from incurring a sense of disappointment. At our institution, we developed a telemedicine curriculum for residents to be used for their continuity clinic curriculum to prevent lapses in their continuity clinic experience. We also created a timecard for residents on distance learning to ensure their educational accountability. The timecards are reviewed by program leadership and residents document the learning activities completed.

Finally, the respondents in this study overwhelmingly agreed lifestyle changes due to COVID-19 negatively affected their well-being. A systematic review by Raj7 identified social connectedness as an important factor influencing resident well-being. Although social distancing is a fundamental component to control the COVID-19 pandemic,28 the psychological fallout among residents must be considered. During times of crisis, it may be difficult for a resident to maintain their own well-being. Collectively sharing the responsibility of wellness with fellow residents may create high-quality relationships and increase connectedness to their program. Such groups may also be a useful resource for sharing ideas on how to creatively respond to the pandemic. The residents in our program reached out to colleagues independently, but creating a daily check-in using social media or virtual meetings platforms can help them stay in regular communication. We found that conducting scheduled town hall meetings with program leadership and group debriefing sessions with our psychologists helped foster transparency and address resident concerns. Previous studies have reported that during the COVID-19 pandemic, individual psychotherapy such as cognitive behavioral therapy and mindfulness-based therapies have been beneficial including the general population and health care personnel.

There are several limitations in our study. This was a small, single institution study performed during Stage 2 of ACGME pandemic planning and hence is limited in generalizability. However, similar studies specific to resident wellness during a pandemic or disaster situation have not been published previously and therefore our results may be useful for future research endeavors. As the COVID-19 section of survey was not validated, response bias may have affected our results. Finally, due to our study design, we were not able to measure baseline sense of well-being prior to the pandemic. Larger multicenter studies are necessary to understand how changes in the operational framework of the academic training environment affect resident well-being during pandemics or disasters.

Conclusions

We identified factors specific to the COVID-19 pandemic that adversely affected resident physician well-being. Trainees were concerned about the risk of developing COVID-19 and spreading this to their family. Residents also harbored anxiety regarding the effect of COVID-19 on their education. Lifestyle changes including social isolation also resulted in a negative effect on resident well-being. Developing strategies and resources directed to addressing these concerns may help support well-being and alleviate stress and anxiety. With the ambiguity regarding the course of the COVID-19 pandemic, pediatricians who interact with residents or are involved in resident education should focus on developing strategies and resources specifically directed to address these concerns to promote well-being and allay anxiety during this difficult time.

Footnotes

Funding:The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Declaration of Conflicting Interests:The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Author Contributions: The first draft of the manuscript was written by PS and VV. PS and VV were responsible for the conception and design of the study. They contributed to the abstraction, analysis and, interpretation of data. KA and JL was responsible for analysis and, interpretation of data. CS and AV were responsible for the design and contributed to the analysis and interpretation of the data and provided oversight. All of the authors contributed to the drafting and revising of the manuscript and approved the final version submitted for publication.

References

- 1. ACGME Resident/Fellow Education and Training Considerations related to Coronavirus (COVID-19). ACGME; https://acgme.org/Newsroom/Newsroom-Details/ArticleID/10085/ACGME-Resident-Fellow-Education-and-Training-Considerations-related-to-Coronavirus-COVID-19. Updated 2020. Accessed April 18, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 2. Nasca T. ACGME’s early adaptation to the COVID-19 pandemic: principles and lessons learned. J Grad Med Educ. 2020;12:375-378. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Hasan A, Mehmood N, Fergie J. Coronavirus Disease (COVID-19) and pediatric patients: a review of epidemiology, symptomatology, laboratory and imaging results to guide the development of a management algorithm. Cureus. 2020;12:e7485. doi: 10.7759/cureus.7485. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Chiel L, Winthrop ZS, Winn A. The COVID-19 pandemic and pediatric graduate medical education. Pediatrics. 2020:e20201057. doi: 10.1542/peds.2020-1057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Collier V, McCue J, Markus A, Smith L. Stress in medical residency: status quo after a decade of reform? Ann Intern Med. 2002;136:384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Low ZX, Yeo KA, Sharma VK, et al. Prevalence of burnout in medical and surgical residents: a meta-analysis. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2019;16:1479. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Raj SK. Well-being in residency: a systematic review. J Grad Med Educ. 2016;8:674-684. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Lai J, Ma S, Wang Y, et al. Factors associated with mental health outcomes among health care workers exposed to coronavirus disease 2019. JAMA Netw Open. 2020;3:e203976. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Chew NWS, Lee GKH, Tan BYQ, et al. A multinational, multicentre study on the psychological outcomes and associated physical symptoms amongst healthcare workers during COVID-19 outbreak [published online ahead of print April 21, 2020]. Brain Behav Immun. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2020.04.049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Tan BYQ, Chew NWS, Lee GKH, et al. Psychological impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on health care workers in Singapore. Ann Intern Med. 2020;172:M20-1083. doi: 10.7326/M20-1083. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Brooks S, Webster R, Smith L, et al. The psychological impact of quarantine and how to reduce it: rapid review of the evidence. Lancet. 2020;395:10227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Adams J, Walls R. Supporting the health care workforce during the COVID-19 global epidemic. JAMA. 2020;323:1439. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.3972. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Varun Choudhary M. Addressing anxiety about the coronavirus (COVID-19): healthcare workers. Magellanhealthinsights.com; https://magellanhealthinsights.com/2020/03/12/addressing-anxiety-about-the-coronavirus-covid-19-healthcare-workers/. Updated 2020. Accessed April 23, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 14. Lima C, Carvalho P, Lima I, et al. The emotional impact of Coronavirus 2019-nCoV (new Coronavirus disease). Psychiatry Res. 2020;287:112915. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Tran BX, Ha GH, Nguyen LH, et al. Studies of novel coronavirus disease 19 (COVID-19) pandemic: a global analysis of literature. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17:4095. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) situation summary. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/cases-updates/summary.html. Updated 2020. Accessed April 18, 2020.

- 17. Pepe D, Martinello R, Juthani-Mehta M. Involving physicians-in-training in the care of patients during epidemics. J Grad Med Educ. 2019;11:632-634. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Beck A, Ward CH, Mendelson M, Mock J, Erbaugh J. Inventory for measuring depression. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1961;4:561-571. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1961.01710120031004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Cohen S, Kamarck T, Mermelstein R. A global measure of perceived stress. J Health Soc Behav. 1983;24:385. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Reis RS, Hino AA, Añez CR. Perceived stress scale: reliability and validity study in Brazil. J Health Psychol. 2010;15:107-114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Slisco A. More than 50 doctors in Italy have now died from coronavirus. Newsweek. March 27, 2020. https://www.newsweek.com/more-50-doctors-italy-have-now-died-coronavirus-1494781. Accessed March 27, 2020.

- 22. Wu Z, McGoogan J. Characteristics of and important lessons from the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) outbreak in China. JAMA. 2020;323:1239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Jalloh MF, Li W, Bunnell RE, et al. Impact of Ebola experiences and risk perceptions on mental health in Sierra Leone, July 2015. BMJ Glob Health. 2018;3:e000471. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Goulia P, Mantas C, Dimitroula D, Mantis D, Hyphantis T. General hospital staff worries, perceived sufficiency of information and associated psychological distress during the A/H1N1 influenza pandemic. BMC Infect Dis. 2010;10:322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19). Strategies for optimizing the supply of facemasks Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/hcp/ppe-strategy/index.html. Updated 2020. Accessed April 23, 2020.

- 26. Worker at NYC hospital where nurses wear trash bags as protection dies from coronavirus. New York Post. March 25, 2020. https://nypost.com/2020/03/25/worker-at-nyc-hospital-where-nurses-wear-trash-bags-as-protection-dies-from-coronavirus/. Accessed April 23, 2020.

- 27. Kang J, O’Donnell J, Colaianne B, Bircher N, Ren D, Smith K. Use of personal protective equipment among health care personnel: results of clinical observations and simulations. Am J Infect Control. 2017;45:17-23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Glass RJ, Glass LM, Beyeler WE, Min HJ. Targeted social distancing designs for pandemic influenza. Emerg Infect Dis. 2006;12:1671-1681. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]