Highlights

-

•

Sustainability transformations are multi-level and multi-phase processes.

-

•

Socio-political shocks can be windows of opportunity but process needs to be navigated.

-

•

Case studies in Chile, South Africa and Uzbekistan show different outcomes.

-

•

Success depends on features and capacities to navigate transformation processes.

-

•

Different phases of transformation require different features and capacities.

Abstract

Faced with accelerating environmental challenges, research on social-ecological systems is increasingly focused on the need for transformative change towards sustainable stewardship of natural resources. This paper analyses the potential of rapid, large-scale socio-political change as a window of opportunity for transformative change of natural resources governance. We hypothesize that shocks at higher levels of social organization may open up opportunities for transformation of social-ecological systems into new pathways of development. However, opportunities need to be carefully navigated otherwise transformations may stall or lead the social-ecological system in undesirable directions. We investigate (i) under which circumstances socio-political change has been used by actors as a window of opportunity for initiating transformation towards sustainable natural resource governance, (ii) how the different levels of the systems (landscape, regime and niche) interact to pave the way for initiating such transformations and (iii) which key features (cognitive, structural and agency-related) get mobilized for transformation. This is achieved through analyzing natural resource governance regimes of countries that have been subject to rapid, large-scale political change: water governance in South Africa and Uzbekistan and governance of coastal fisheries in Chile. In South Africa the political and economic change of the end of the apartheid regime resulted in a transformation of the water governance regime while in Uzbekistan after the breakdown of the Soviet Union change both at the economic and political scales and within the water governance regime remained superficial. In Chile the democratization process after the Pinochet era was used to transform the governance of coastal fisheries. The paper concludes with important insight on key capacities needed to navigate transformation towards biosphere stewardship. The study also contributes to a more nuanced view on the relationship between collapse and renewal.

1. Introduction

With globalization and the new era of the Anthropocene, it has become increasingly clear that a prosperous social and economic development rests on the capacity of the biosphere to sustain it. Incremental changes and adaptations on current development pathways may be insufficient for achieving sustainability (Olsson et al., 2017; Westley et al., 2011). Hence, the interest is increasing in understanding transformations of social-ecological systems (SES) from unsustainable development pathways towards more sustainable ones that reconnect societal development with the biosphere and stewardship of critical ecosystem services (Folke et al., 2010; Gunderson and Holling, 2002; Walker et al., 2009). Achieving such sustainability transformations, however, can be difficult because of the persistence of existing social and ecological structures and processes, which have to be overcome during transformation processes (Olsson et al., 2014). Understanding of transformation thus has to go beyond a focus on what triggers transformation to unravelling the capacities to reduce the resilience of the undesired, status quo system as well as nurturing and navigating the emergence of new, desired systems.

There is a rich literature on path dependency, traps, and early warnings in relation to thresholds, transitions, and regime shifts in the social or ecological domains (Carpenter et al., 2011; Carter and Barrett, 2006; Gargiulo and Benassi, 2000; Geels, 2002; Goertz and Diehl, 1995; Gordon et al., 2008; Keeler, 1993; Pelling and Dill, 2010; Scheffer et al., 2012; Thelen, 1999). Building on early studies on transitions, transformations, and regime shifts of linked social-ecological systems (SES) (Berkes and Folke, 1998; Danter et al., 2000; Gunderson and Holling, 2002; Olsson et al., 2004b; Scoones, 1999) the number of studies on this topic has rapidly increased in the last decade (Abson et al., 2017; Adger et al., 2009; Avelino, 2017; Blythe et al., 2018; David Tàbara et al., 2018; Enfors, 2013; Goldstein et al., 2018; Loorbach et al., 2017; Patterson et al., 2017; Pereira et al., 2015; Reyers et al., 2018; Westley et al., 2017). By transformation we refer to the capacity to create fundamentally new systems of human-environmental interactions and feedbacks when ecological, economic, or social structures make the existing system untenable (Walker et al., 2004). This includes breaking the self-reinforcing feedbacks of a social-ecological system that produce undesired outcomes and that lock them into certain trajectories as well as creating new feedbacks that can help it move in new directions (Olsson et al., 2017).

Sustainability transformations thus involve the change of multiple elements of the SES, including beliefs, behaviors, and institutions at multiple levels (Moore et al., 2014). It has been proposed that the capacity to transform a SES draws on agency and structures from multiple levels, making use of crises as windows of opportunity for novelty and innovation, and recombining sources of experience and knowledge to navigate the process of social-ecological transformation (Folke et al., 2010, 2005; Olsson et al., 2004b). When faced with shocks, SES may deal with change through adaptation or transformation (Brown and Westaway, 2011; Folke et al., 2010). This does not necessarily entail that these responses are sustainable, as they may continue to develop on unsustainable pathways (Chapin et al., 2010). Major socio-political changes as they have occurred in the last decades in various regions of the world, constituted shocks that severely affected natural resource governance in the respective countries. Few studies, however, have investigated whether and how such radical political change at national levels enabled transformations of the governance of natural resources like freshwater or seafood (Gelcich et al., 2010; Herrfahrdt-Pähle and Pahl-Wostl, 2012; Nastar and Ramasar, 2012).

We address this question by investigating whether and under which conditions socio-political change (e.g. from dictatorship towards democracy) served as a window of opportunity for initiating transformation of natural resource governance and whether and how transformative processes were maintained. To this end we analyze transformations in natural resource governance of three countries that have been subject to rapid, large-scale political change: water governance and related ecosystem services in South Africa and Uzbekistan and governance of shellfisheries in coastal ecosystems of Chile. The development of the resource governance regimes in the three case studies after the socio-political shocks was very different: from transforming marine governance (Chile) to largely maintaining the status quo under a different name (Uzbekistan). We analyze which elements, if any, of the SES in each case have transformed and what has enabled this transformation.

Our conceptual framework for analyzing the three case studies focusses on capturing 1) processes of transformation or persistence and cross-level interactions during different phases before and after the socio-political shock and 2) the SES features that get mobilized for initiating and navigating transformational change or opposing such change. For the former we build on the framework of phases and sub processes of SES transformations proposed by Olsson et al. (2004, 2006) and Moore et al. (2014) combined with the multi-level perspective on transitions proposed by Geels (2007). For the latter we review resilience thinking to identify key cognitive, structural, and agency-related features that affect processes of change in SES. We analyze cross-level interactions and key features during different phases of preparing, navigating and institutionalizing a transformation in the three case studies to compare reasons explaining their different outcomes. We conclude with proposing key capacities for successful transformation towards improved biosphere stewardship.

2. Conceptual background: cross-level interactions and key features of transformational change

Research in recent years has consolidated our understanding of sustainability transformations as multi-level and multi-phase processes where change agents navigate different opportunity contexts in order to achieve change (Avelino and Rotmans, 2009; Chaffin and Gunderson, 2016; Cosens et al., 2014; Geels et al., 2017; Loorbach et al., 2017; Olsson et al., 2006; Patterson et al., 2017; Smith et al., 2005). We combine an analysis of multiple phases with an analysis of multiple levels from the resilience and transitions literatures to capture the temporal and the multi-level dimensions of transformations, which has rarely been done.

2.1. Integrating phases and levels of transformation

Sustainability transformations can be conceptualized as typically proceeding in three phases: the preparation phase, the navigation phase and the stabilization or institutionalization phase, serving to build resilience of the new regime (Chapin et al., 2010; Moore et al., 2014; Olsson et al., 2004b; Olsson et al., 2006; Rotmans et al., 2001). These phases are often triggered or influenced by environmental and/or social disruptions, which can put the prevailing regime under pressure and make it more open to change (Gunderson and Holling, 2002; Olsson et al., 2006).

The resilience and the transitions literatures both conceptualize complex SES as multi-level systems and transformations of these systems as multiphase and cross-scale processes (Geels and Schot, 2007; Gunderson and Holling, 2002), but have different points of departure and theoretical focuses (see for example Folke et al., 2010; Olsson et al., 2014; Moore et al., 2014). For example, in the SES perspective, the word “transition” is used in the “navigating the transition” phase which means that “transition” is a subset of a larger transformation rather than addressing the whole shift. Over the past decades, the transition and resilience fields have moved closer together (see e.g. Loorbach et al., 2017; Olsson et al., 2014) and in this article we build on this literature to combine insights from both of these fields in our analytical framework, similarly as proposed by Moore et al. (2014).

The multi-level perspective from transition management focusses on three interacting levels: the landscape, the regime and the niche (Geels, 2010). The landscape constitutes the social and environmental background of a regime. It transports the broad social values and political culture but also environmental problems. The landscape thus provides the “railings” for social interaction and developments within regimes, defined as dominant and (semi-) coherent rule sets established to address certain problems, for example a natural resource governance regime. Interactions between the landscape and the regime are usually characterized by long-term processes. The regime describes “the most dominant actors, structures and practices; it dominates the functioning of the societal system and defends the status quo” (Avelino and Rotmans, 2009). Regimes can be influenced by the emergence of new ideas, technologies, etc., that have been developed in niches – small protected areas for experimentation and out-of-the-box-thinking (Geels, 2002; Gunderson and Holling, 2002; Westley et al., 2011). Niches develop when actors begin to question a current regime and find ways and room for innovation and experimenting with alternative regime configurations. When operating in niches, actors are often not bound by regime constraints – a situation enabling them to mobilize different resources and come up with novel ideas (Avelino and Rotmans, 2009).

Both strands of literature argue that transformative change develops as these multiple levels interact (Avelino and Rotmans, 2009; Chaffin and Gunderson, 2016; Cosens et al., 2014; Olsson et al., 2014). For example, major disruptions at the landscape level, such as political elections or a major drought, may put pressure on an established resource governance regime, which seems no longer functional under the changed conditions. This may lead to questioning an economic model based on massive water use by irrigated agriculture to the detriment of the environment. If actors of a specific niche have previously developed new knowledge on alternative modes of using and governing water, they might use the instability of the regime caused by the disruptions at the landscape level as a window of opportunity to start institutionalizing the new approach (Avelino and Rotmans, 2009; Chaffin and Gunderson, 2016).

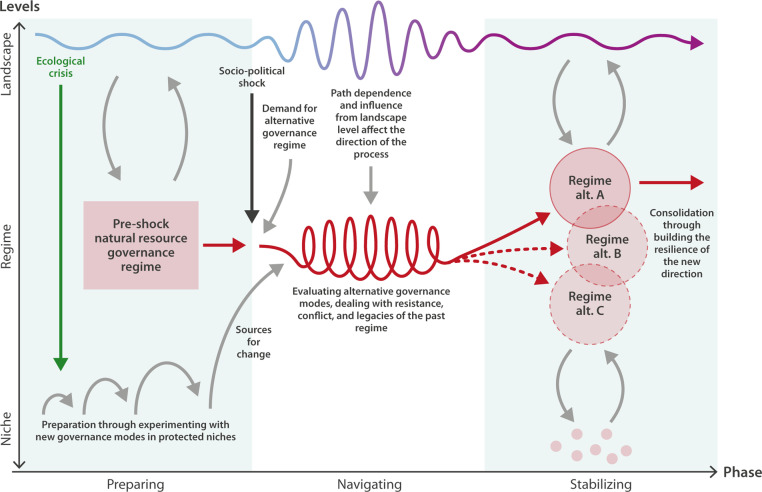

In Fig. 1 below we integrate the phases of transformations - preparing, navigating and stabilizing - into the multi-level approach to transitions. Following the framework proposed by Moore et al. (2014), we assume that the niche development and preparation phase is often triggered by a perturbation or crisis, in our cases an ecological crisis. However, we expand the framework by adding a second perturbation at the end of the preparation phase. We hypothesize that this perturbation, such as the socio-political shocks we investigate, shakes up and weakens the established regimes and provides a window of opportunity for actors to promote and institutionalize alternative approaches for governing natural resources. The resulting framework allows us to analyze the interaction across different levels during the phases of transformation.

Fig. 1.

Transformations as multi-level and multi-phase processes. In the preparation phase, a crisis or anticipated risks, such as ecological ones, can trigger initiatives to experiment with new practices and alternative governance modes. Within protected niches the experiments and the innovations they generate can be developed and combined with other ideas that share the same concerns. Opportunities for transitioning towards new governance modes can open up due to abrupt change at the landscape level, e.g. following a sociopolitical shock. Alternative governance modes, developed in the preparation phase, can be transferred into the navigation phase and start to become institutionalized. This process includes evaluating and combining a range of available, and sometimes competing, ideas and approaches. This phase may lead to the institutionalization of a sustainability transformation. There are, however, risks that legacies from the landscape level and the previous regime affect the disruptive potential of the alternative modes leading to alternative outcomes: i) the ideas are actively rejected/shut down/outcompeted or ii) the ideas are coopted by the status quo system. In the stabilization phase, the alternative approaches (whether sustainable or not) have been institutionalized within new governance regimes and are embedded in the landscape level. Processes include consolidating new values, implementing and enforcing new rules and regulations, and routinization of new practices (Illustration by J. Lokrantz/Azote).

2.2. Key features enabling or hindering transformation

Shocks, such as socio-political change, that can trigger a transformation often originate outside of the respective resource governance regime. The impact of a shock on the regime and its development, however, largely depends on the constellation of actors and interactions between a number of factors and processes within the respective regime. The resilience literature has identified social features that are important for resilience and transformability of SES (Anderies et al., 2004; Folke et al., 2005, 2003; Olsson et al., 2004b; Olsson et al., 2006; Pahl-Wostl, 2009). Our aim is to identify which of these features (and in which combinations) have facilitated a transformation at the regime level in situations where a large-scale shock provided a window of opportunity. We argue that on the one hand the presence of a number of features of resilience (such as combining different types of knowledge, social learning and leadership) can enable transformations. On the other hand, some features of resilience need to be broken down before transformation is possible (such as social networks, power structures and institutional settings that consolidate a status quo) (Olsson et al., 2014). We group these features into three categories, which are assumed to be the main leverage points for transformation: cognitive, structural and agency-related features (Table 1; see methods below).

Table 1.

Cognitive, structural and agency-related features identified as important for transformation in the resilience literature.

| Feature | Description or Example | Reference (examples) |

|---|---|---|

| Cognitive | ||

| Awareness of need for change | Political and personal will to transform | (Cosens et al., 2014; Olsson et al., 2006) |

| Social learning | Change at individual level as well as in broader social units/ communities of practice, e.g. through participation, collaborative governance | (Folke et al., 2005; Pahl-Wostl et al., 2007; Reed et al., 2010) |

| Social memory | Preserve and make knowledge available, e.g. experience for dealing with change | (Folke et al., 2005) |

| Knowledge integration | Combining different types of knowledge, knowledge integration | (Folke et al., 2005; Gelcich et al., 2019) |

| Structural | ||

| Enabling institutional setting | Flexible, formal/informal institutions | (Ostrom, 2009) |

| Bridging organizations and collaborative learning platforms | Structures that facilitate dialog and learning | (Folke et al., 2005; Olsson et al., 2006) |

| Diversity of actor groups | Regarding function and knowledge | (Folke et al., 2005; Gelcich et al., 2019) |

| Trust | The level of trust within groups, networks or society at large, e.g. in the ability of the government to address problems | (Folke et al., 2005; Olsson et al., 2006; Ostrom, 2009) |

| Informal institutions | Informal spaces support integration of knowledge and experimentation | (Pahl-Wostl, 2015) |

| (Shadow) networks / niche | Enhance collaboration across levels and scales, activate social memory, enable deviation from status quo | (Folke et al., 2005; Olsson et al., 2006; Rotmans et al., 2001) |

| Agency-related features | ||

| Leadership | Build trust, link actors and knowledge | (Folke et al., 2005; Olsson et al., 2006) |

| Power | Distribution of power across levels, shifts in power | (Avelino and Rotmans, 2009; Boonstra, 2016; Westley et al., 2013) |

| Access to information or flow of information | Availability of information as a condition for e.g. identifying sound solutions or building social memory | (Olsson et al., 2004b) |

Cognitive features address the prevailing paradigms and knowledge systems. A necessary requirement for the initiation of change is awareness of the need for change, e.g. reflected in the political and personal will to transform (Cosens et al., 2014). This includes the ability to identify emerging windows of opportunity (Folke et al., 2010). Social memory, the way collective memory is created and how social arrangements structure actions (Olick and Robbins, 1998), is important for preserving knowledge such as how to deal with unexpected events and making it available for dealing with uncertainty and change in other contexts (Folke et al., 2005). Sometimes knowledge that was suppressed by the old regime resurfaces and gets used again. Once a new system is established after a transformation, new knowledge is generated, integrating or slowly replacing former knowledge (e.g. on water saving techniques). Whether old, replaced social knowledge can be reactivated at a later point in time is influenced by how long the new system prevailed and how rigorously it replaced old knowledge (de Melo et al., 2001). In most SES, different sources or types of knowledge coexist and interact, such as scientific knowledge, local knowledge, tacit knowledge, experimental knowledge and experiential knowledge (Folke et al., 2003). Combining these types of knowledge and expanding from knowledge of structures towards knowledge of functions (e.g. of ecosystems) is vital for understanding social-ecological interactions and shaping change (knowledge integration; Folke et al., 2005, 2003). The generation of knowledge and social memory is closely linked to social learning, which refers to changes in understanding that are situated within broader social units and has been generated by social interactions of actors within social networks (Reed et al., 2010). It is key for developing new ideas and concepts for dealing with problems of natural resource governance and for expanding knowledge on functions (Pahl-Wostl et al., 2007).

Structural features refer to organizational and institutional relations and structures within a SES. They are the result of a co-evolutionary process of the environmental system on the one hand and hierarchies, power relations, legislative and management procedures on the other (Kallis and Norgaard, 2010). They stabilize a system but should be flexible enough to enable change, communication and learning across levels and scales. The latter are critical for the development, entrance and diffusion of new ideas into the SES (Ostrom, 2009). An enabling institutional setting (e.g. legislation) is assumed to support adaptation to environmental change and thus foster resilience (Folke et al., 2005). Besides formal institutional arrangements and organizations, informal institutions and networks are assumed to play an important role in promoting alternative approaches to natural resource governance and management, e.g. by supporting the integration of knowledge and experimentation e. However, rigid informal institutions also have the potential to hinder structural change.

Processes of learning and innovation can be facilitated by so-called bridging organizations and collaborative learning platforms, which (in a formal setting) bring a diverse set of stakeholders and policy makers together for discussing and solving problems of natural resource use and management and facilitating dialogue and learning across levels of governance (Folke et al., 2005; Hahn et al., 2006; Olsson et al., 2006). Within these learning platforms in particular, but also in other settings of social learning in general, the diversity of actor groups regarding functions and knowledge is important (Folke et al., 2005). To function well, mixed actor groups depend on good social relations in the form of trust, confidence and empowerment (Olsson et al., 2006). Thus, trust relates to a form of social capital that exists at societal level rather than on the individual level. These forms of relational capital within society are difficult to build but easily destroyed (Wallis and Ison, 2011). Diverse actor groups and trust are the basis for the formation of networks – in particular shadow networks (Olsson et al., 2006) – combining actors with different backgrounds and enabling discussions outside the formal organizational and institutional setting, enhancing collaboration across levels and activating social memory (Folke et al., 2005). Shadow networks are particularly important in the niche development and the preparation phase, for increasing flexibility of institutions and prevailing paradigms as well as for developing new ideas and fostering out-of-the-box-thinking (Olsson et al., 2006; Sendzimir et al., 2007).

Change and innovation in complex social-ecological or socio-technical systems are initiated and guided by actors or actor groups whose success depends on the respective constellation of actors, the distribution of power and leadership (Avelino and Rotmans, 2009). With the category of agency-related features we therefore account for agency, incentives and power as important drivers or barriers for transformation and change (de Haan and Rotmans, 2018; Folke et al., 2010; Westley et al., 2011). Innovation and learning depend on the existence of leadership and the leader's ability to build trust, form coalitions of actors and actor groups, compile knowledge, create and communicate a vision (Folke et al., 2005; Kotter, 1995; Olsson et al., 2006). The success of leaders or institutional entrepreneurs in institutionalizing new approaches to natural resource governance depends among other things on their position within a hierarchy, their ability to use their power to introduce new ideas, the distribution of power across levels and shifts in power (Avelino, 2017; Avelino and Rotmans, 2009; Boonstra, 2016; Folke et al., 2005; Westley et al., 2011, 2013). This involves the ability of institutional entrepreneurs to influence (formal and informal) decision making (Safarzyńska and van den Bergh, 2010), by e.g. building alliances and organizing potential winners against potential losers of change (Kotter, 1995) . On a conceptual level, power is used by niche-actors to influence and challenge a current regime (Avelino and Rotmans, 2009). The availability of power is among others based on the ability to access information (Folke et al., 2005; Olsson et al., 2004a). The flow of information enables combining different sources of knowledge and building social memory (Olsson et al., 2004a), thereby linking agency-related features to the cognitive features.

3. Methods

3.1. Selection of case studies, identification of phases of transformation and critical features

We selected cases that recently experienced a large socio-political shock and have a looming ecological crisis. Chile, South Africa and Uzbekistan all underwent significant political disruptions during the 1990s and they are all struggling with ecological crises such as water shortages or declining fish stocks. We delineated the different phases of transformation in each case study based on the timing of the shock (distinction between preparation and navigation phase) and other major changes on the landscape level, but also by the occurrence of new social interactions and change of old ones within the respective governance regime itself (distinction between navigation and stabilizing phase). From the literature, we identified a number of features, which were associated as critical elements of transformations. We then aimed at further structuring our analysis by grouping these features in cognitive, structural and agency-related features. We thus diverge from other approaches grouping along hierarchical levels (O´Brien and Sygna, 2013). This allowed us to trace features such as power or trust across different societal levels. It further enabled us to not only identify but also evaluate the relevance of different sets of features in each case study in the respective phases. We did this using our own field research and the literature (see sources of data below). An extensive analysis of all relevant features can be found in Tables A1–A3 in the Appendix. Here we present key within and cross-level processes within each phase (Fig. 2, Fig. 3, Fig. 4) and a summary of key features that facilitated these processes in Table 2, Table 3, Table 4.

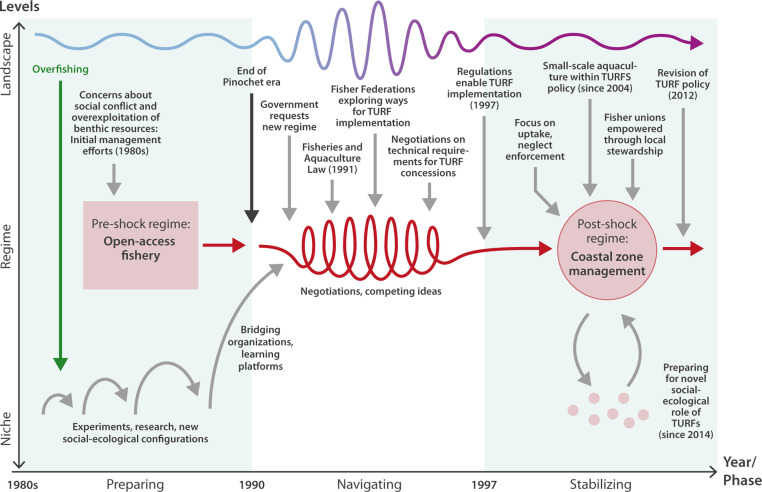

Fig. 2.

Multi-level analysis: Chile (Illustration by J. Lokrantz/Azote).

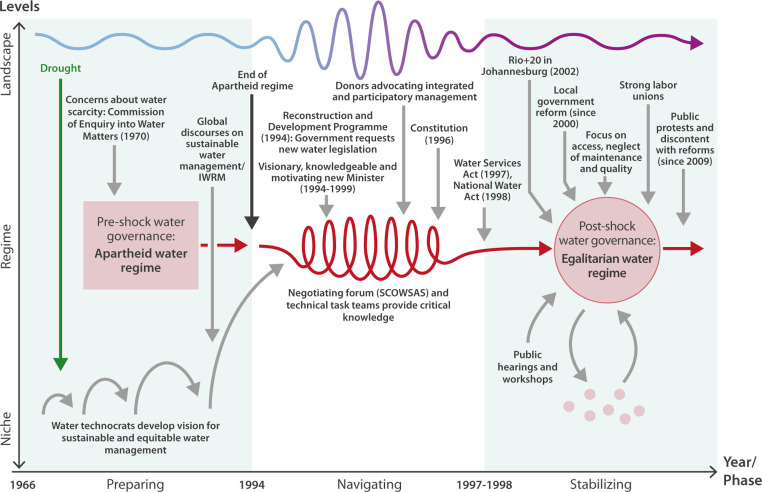

Fig. 3.

Multi-level analysis: South Africa (Illustration by J. Lokrantz/Azote).

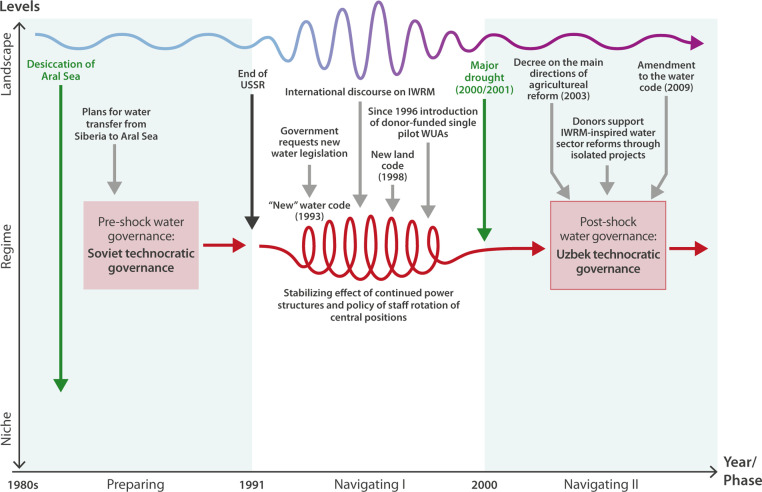

Fig. 4.

Multi-level analysis: Uzbekistan (Illustration by J. Lokrantz/Azote).

Table 2.

Key features of transformative change: Chile. TURFs = territorial user rights for fisheries. For details see Table A1.

| Feature/phase | Preparing (1980s-1990) | Navigating (1990–1997) | Stabilizing (since 1998) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cognitive | Scientists and fishers came together because of the declining resources; awareness of need for experimenting and need of new knowledge; emergence of communities of practice; social learning lead to a shift in mental models towards collaborative management; learning about the role of others | Reviving of bridging relationships between fisher organizations; awareness among key individuals at the national level (policy makers) | Adaptation of new concepts; slow shift towards participatory and more polycentric practices based on social learning within a key group of people from the Undersecretary of Fisheries. |

| Structural | Pre-existing concept of fishing cove and fishing unions which linked past experiences with future co-management approach; missing regulations in fisheries (open access) triggered individuals to act; existing social capital facilitated collective action and experimentation | Change from dictatorship to democracy enabled establishment of new networks and revival of old ones and opened up space for establishing new institutions; Confederations of artisanal fishers re-emerged and acted as a bridging organization that allows transfer of knowledge. | Demanding requirements of TURFs imply increased costs; increased problem with poaching from outsiders of TURFs is a hard problem to address; Formal government and informal fisher support networks struggle to address the issue. |

| Agency | Leadership created the safe space for experimentation; a network of key individuals provided agency for preparing for change | The confederation is a national player that provided the necessary political leverage for creating the new legislative framework; Scientists played an active role in disseminating the potential of TURFs around Chile. | Policy has consolidated and key leaders have been instrumental to adapt policy in time to include other activities for organized fishers such as aquaculture and artificial reefs. |

Table 3.

Key features of transformative change: South Africa. For details see Table A2.

| Feature/phase | Preparing (1966–1993) | Navigating (1994–1998) | Stabilizing (since 1999) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cognitive | Dominating technical control paradigm; dominating white commercial farming and mining at expense of non-white population (dual economy); Commission of Enquiry into Water Matters (1970) raises awareness towards water scarcity, pollution and innovative water governance; group of water technocrats develops a vision for sustainable water management | Strong political commitment for change towards equity, sustainability, efficiency; inclusive and participatory process of developing a new water legislation (inclusion of local and international knowledge); high rotation of staff at all levels of water administration intended to deactivate former (apartheid era) social knowledge and ties | Revision of reforms and reduction of number of CMAs from 19 to nine in order to enhance implementation; loss of social memory due to high staff turnover |

| Structural | Highly centralized water governance regime; limited access to land and water for non-white population; informal network of water managers and scientists forms to circumvent centralized and authoritarian water bureaucracy and discuss vision for future water law | Constitution acknowledges the right to water and environmental rights and calls for cooperative governance, i.e. linkages across levels; technical task teams and negotiating forum provide critical knowledge; promulgation of National Water Act (1998) requires setup of new participatory institutions (CMAs, WUAs) | Flexibility and openness as well as demanding requirements of the new water legislation slow down implementation process; poor results (especially regarding access to safe water supply and sanitation) and corruption undermine trust in the government |

| Agency | Strong lobby of (white) commercial farming and mining | Visionary and knowledgeable Minister uses momentum of political change and integrates available (national and international) knowledge to develop state-of -the-art water law; shift of power from white minority to democratic government supported by BBBEE Policy | High turn-over in staff at all levels (including Ministers and Deputy Director Generals) creates uncertainty, disrupts the reform process, means a loss of memory and results in a lack of transparency and trust |

Table 4.

Key features of transformative change: Uzbekistan. For details see Table A3.

| Feature/phase | Preparing (1960s-1990) | Navigating I (1991–1999) | Navigating II (since 2000) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cognitive | No awareness of need for change; dominance of technical control paradigm; loss of memory of alternative governance modes | Strong social memory concerning Soviet mode of governance; persistence of top-down management and technical control paradigm; creation of knowledge and knowledge management controlled by the state; introduction of new water paradigm by international donors | Need to reform water management because of land reforms; no room for social learning; adaptation of new concepts according to old water management paradigm; WUAs are increasingly acknowledged by farmers |

| Structural | State order system; dominance of the agricultural sector; cultural values such as strong hierarchies restrict experimentation; low level of trust among actors | Strong informal networks (of powerful elites) and informal institutions (clientelism, patron-client relationships, corruption) are used to bypass rigid and outdated water law; frequent change of cadres; restrictions on civil society | Introduction of new water management institutions in a top-down manner by very variable decrees creates legal uncertainty; further restrictions on civil society; new formal rules are contested not by open criticism but by reverting to informal practices |

| Agency | Strong influence of regional elites prevents emergence of new leaders | Persistence of Soviet leadership; elites´ vested interests in economic and political power act against (market-based) reforms; lack of transparency and access to information | New institutions such as WUAs are integrated in the existing patronage system; removal of successful and influential leaders |

3.2. Sources of data

The paper is primarily based on analysis of secondary data documented in the literature as well as reports. This literature review has been supplemented by revisiting field notes and interviews of the authors´ previous research projects in the case study countries. These include the EU-INTAS Amudelta project (Restoration and management options for Tugai and aquatic ecosystems in the Amudarya river delta, 2000–2003), the NeWater project (New Approaches to adaptive water management under uncertainty, 2005–2009) for South Africa and Uzbekistan, the FONDECYT projects (Assessment of TURFs management policies and ecosystem services, 2009–2011; 2012–2014) and policy documents produced by the Undersecretary of Fisheries in Chile and the Chilean Fishery and Aquaculture Law (1991).

4. Patterns of cross-level interactions and key features enabling or preventing change in Chile, South Africa and Uzbekistan

In this section, we briefly characterize the respective SES in each case study and the ecological and livelihood crises they experienced. We then analyze events and features at different levels of the SES after the socio-political shock that have enabled or hindered the transformation to a new governance regime. Details of each case study, particularly a detailed table of cognitive, structural and agency-related features enabling or hindering transformation can be found in the Appendix.

4.1. Chile

Chile experienced a socio-political shock when the Pinochet regime ended in 1990 and Chile's national government changed into a democracy after 17 years of dictatorship (Fig. 2). Before the 1990s marine coastal management in Chile was based on top-down government interventions. An emerging collapse of the loco (a highly valued mollusk) was evident in the 1980s (Gelcich et al., 2010). During the Pinochet dictatorship most resources, including marine resources, operated under a de facto open access regime. This pre-shock regime of open access changed into a governance regime where marine resources were managed through TURFs (Territorial user rights for fisheries). This transformation was enabled through key processes and features at different times and levels of the SES as detailed below.

4.1.1. Before the socio-political shock (preparing)

Collaborations between fishers and scientists to address an ecological crisis in the 1980s resulted in an enhanced understanding of the potential role of fishers in structuring marine ecosystems. This came at a time when artisanal fishers were concerned about the depletion and recovery of several key benthic resources (Gelcich et al., 2010). It created the opportunity for scientists and existing fisher associations to exchange information and develop participatory research at a larger scale, encompassing specific fishing coves, or “caletas” (Navarrete et al., 2010). These pilot experiences constituted a set of critical learning platforms, which generated new knowledge that helped to develop a shared vision of local fisher associations having exclusive rights and responsibilities to collectively manage local benthic resources (Gelcich et al., 2010). At the end of the preparation phase, artisanal fishers in Chile were reorganizing into a single national confederation or meta-organization that grouped all artisanal fisher associations. This confederation was in effect a “shadow network” that had been suppressed between 1973 and 1989 (Gelcich et al., 2010). The confederation became a significant national player during the transformation because it had grassroots support (see below). This social reorganization provided the necessary political leverage to navigate the major shifts in governance that included the new Fishery and Aquaculture Law (FAL) in 1991.

Critical features that allowed preparing for the transformation were the recognition of the depletion of resource stocks (Castilla, 2010), the need for experimenting to gain new knowledge on the ecology and dynamics of targeted stocks (cognitive) and a network of key individuals that could affect change (agency) as well as latent institutions such as fishing associations that could serve as seeds for future management institutions (structural) (Table 2 and A1 in Appendix).

4.1.2. During the shock and its direct aftermath (navigating)

After democratic elections in 1990, the new government identified the overexploitation of key resources as a social and economic priority and was determined to reform the legislative system, including the governance of coastal fisheries (Gelcich et al., 2010). This provided a favorable political context and with the help of a national network or confederation of fishers (which had been latent for 17 years) the knowledge generated from the research and experiments between artisanal fishers and researchers before the shock (which showed for example that natural re-stocking was possible) (Castilla, 1994) was incorporated into the policy process. This knowledge provided critical elements for the governance transformation, which resulted in the establishment of TURFs.

The governance transformation, however, did not end after legislation granting TURFs had been designed. Prior to their implementation the details on how marine tenure was going to be allocated to fishers was negotiated in debates among fishers, managers and politicians (Gelcich et al., 2010). This was immersed in bureaucratic indecision until 1997. During these years, fisher associations that wished to engage with the TURFs policy could only do so informally , supported by teams of university-linked biologists (Meltzoff et al., 2002). Key people in the Undersecretary of Fishery, jointly with the national confederation of fishers and support of the marine scientific community, finally navigated the transition toward legal TURF regulations for implementation in 1997.

A critical element for navigating this transformation was the ability to communicate new knowledge through a preexisting social network of fishers. In particular, the reemerged fisher confederation provided the capacity and political leverage to help scale the initiative (Gelcich et al., 2010). Members of the confederation of artisanal fishers acted as institutional entrepreneurs (Olsson et al., 2008) and facilitated cross-scale and cross-organizational interactions. In effect, the confederation of fishers represented a bridging organization that could enhance vertical integration from local to national levels among different players.

4.1.3. Long-term developments (stabilizing)

Once the TURFs policy was implemented, the process entered into a stabilizing phase. In this phase a series of legal adjustments were developed, such as the inclusion of aquaculture practices in certain parts of the TURF and changes in the fees payed for having exclusive rights. An underlying aspect to consider when analyzing the stabilizing phase in Chile is that from 2003 onwards, due to the huge development of abalone aquaculture, the price of the loco exported from Chile to the Asian luxury seafood markets was negatively affected (Castilla et al., 2016; Chávez et al., 2010). In essence, it appears that the international export price of loco is determined by the interaction among supply and demand of abalone. The 40-fold increase of aquaculture abalone harvest, during 2002–2013, strongly influenced the price of loco (Castilla et al., 2016). This strong link between the loco fishery, global trade, and distant consumers, which resulted in strong price drops, is decoupled from direct local management practices, but can strongly influence the stabilization of the TURF regime. In fact, one of the main issues which affects the TURF regime relates to the cost of enforcement and high levels of poaching (Gelcich et al., 2017). Poaching implies increased costs associated with surveillance, loss of revenue from harvests, and reduced economic revenue (Davis et al., 2015). The importance and prevalence of poaching is suggestive of a needed policy change to increase logistical support to stop and prosecute poachers. Both formal and informal fisher support networks have struggled to deal with the issue.

Critical features during the stabilizing phase during which the policy was consolidated include a shift towards polycentric and participatory practices (cognitive) and leadership by key people that ensured that the policy was adapted in time to include new emerging activities such as aquaculture (agency) (Sepúlveda et al., 2019). Structural issues such as increasing costs of monitoring and lack of institutions to deal with poaching by outsiders have, however, challenged the new governance regime (Gelcich et al., 2017). New interdisciplinary approaches will be critical to solve the emerging governance frontiers associated with the transformation towards TURFs in a broader management context. Most importantly, developing these approaches into implementable policies and management protocols requires the development of new tools, which can complement and enrich TURFs through the establishment of new learning platforms. A new policy process in which management of de-facto open access areas has been developed since 2013, early assessments of these further governance transformations are urgently required (Gelcich et al., 2019). In addition, academics and practitioners are working with small-scale fishers to design learning platforms in which fishers create enforced, no-take protected areas within their TURFs in exchange for the opportunity costs foregone for not fishing and a price premium in their products (Gelcich and Donlan, 2015). This type of learning platforms are beginning to fill an important gap to design necessary refinements, or even begin establishing a new preparation phase, for further transformations.

4.2. South Africa

The socio-political shock in South Africa was the end of apartheid in 1994 (Fig. 3). Water management until then had been for decades dominated by an engineering, centralized, technical control paradigm, manifesting itself in the view that each drop flowing into the ocean is wasted. During the apartheid era, access to water for domestic and productive purposes was largely a privilege of the white minority. Lack of water, droughts and their consequences created awareness about the need for better management of the scarce water resources. After the end of apartheid water governance changed from an apartheid to an egalitarian water management regime including one of the most progressive water laws in the world. This transformation was triggered and enabled by multiple factors across levels and phases as detailed below.

4.2.1. Before the socio-political shock (preparing)

During apartheid, the water act of 1956 favored industrial and large-scale agricultural water use and thus mainly served the economic interests of the white minority. As a consequence there was a huge backlog in access to safe drinking water and sanitation and poor health standards in black communities, particularly in rural areas (Eales, 2011). Starting in the 1970s and following a severe drought, some concepts of sustainable water governance and management were introduced into water management circles. A critical element in these discussions was the Commission of Enquiry into Water Matters (1970). It questioned man's ability to overcome natural water shortages by building water infrastructure that was embedded in a highly centralized water governance regime. The commission raised awareness of problems of water scarcity and pollution and called for innovative and sustainable water governance and management (Movik et al., 2016). These issues were further discussed in an informal network of water technocrats during the 1980s (Van Koppen et al., 2011) (cf. Table 3; for an extended version of this table cf. Table A2 in the Appendix).

Key features characterizing the preparation phase were the dominance of a technical control paradigm but also an awareness of water scarcity (cognitive), informal networks of water managers that were able to discuss alternative visions of future water management (structural) and a strong lobby of white commercial farmers and miners. While some features such as the awareness and the informal networks that developed new ideas were conducive to enabling a transformation, other features such as the strong control paradigm or the influence of powerful water users presented major obstacles for water governance reforms.

4.2.2. During the shock and its direct aftermath (navigating)

Following the first democratic elections in 1994, the new ANC-led government identified water as a key pillar in the construction of the post-apartheid state (Backeberg, 2005; Swatuk, 2009). Safe access to water and sanitation for black communities and sustainable water governance were priorities of the new democratic government (Muller, 2014; van Koppen and Schreiner, 2014). A new water act was introduced based on the principles of sustainable, efficient and socially inclusive use of water under the motto “some, for all, forever”. The already favorable political context was supported by the emerging global discourse on sustainable development and the occurrence of a drought in South Africa, which created a sense of urgency (Backeberg, 2005).

The new water legislation reduced the fragmentation of responsibilities at national level while at the same time decentralizing water management to the basin level (DWAF, 1997). For this purpose, 19 Catchment Management Agencies (CMAs) were planned (DWA, 2012). Their task was to manage multiple uses of water resources by coordinating the activities and balancing the interests of water users and water management organizations and by promoting community participation in water management (Republic of South Africa, 1998).

Critical features throughout the reform endeavor were social learning and leadership. Large emphasis was given to drawing on international and local expertise and best practices as well as involving citizens in the development of white papers, bills etc. through public hearings and workshops at various levels (Backeberg, 2005; de Coning, 2006). The initial phase of drafting a new water legislation (from 1994 to 1999) was guided and shaped by Kader Asmal, the visionary and knowledgeable Minister with a background as a human rights advocate. He provided political will and authority and was able to motivate and create a strong sense of ownership for the process (Movik et al., 2016).

4.2.3. Long-term developments (stabilizing)

During the following stabilization phase, until 2005, despite changing Ministers, continuity in terms of leadership was provided through the Deputy Director General. Since then, however, constantly changing staff led to high levels of uncertainty and disruption of social memory. The years 1999 to 2016 saw six changes of the Minister (DWS, 2016). At the lower levels of administration the high turn-over of staff was enhanced by (broad-based) Black Empowerment Policy (BBBEE), i.e. the exchange of experienced senior water managers with young professionals with little work experience (Van Koppen et al., 2011). The result was a lack of strategic leadership as well as a lack of implementation at all levels and a deficit of institutionalization of the newly established organizations.

Another obstacle to implementation was that the new legislation provided a framework, guidelines and directions for water policy, but few regulatory procedures, standards and tools e. It is the task of the water administration and practitioners to transfer these into regulations as implementation is proceeding, e.g. regarding the forms of water service provision and type of service provider (SALGA et al., 2003). This was one reason why the establishment of 19 CMAs exceeded implementation capacities and had to be revised. In 2012 the number of CMAs was reduced to nine. These difficulties together with a continuing high turnover of staff, and financial and technical shortcomings considerably slowed down the reform process over the past decade. In recent years the insight is gaining ground that there is a need to reduce complexity in order to speed up the process (Schreiner, 2013). The urgent need for reform results was underlined by public protests since 2009, which were spurred by slow progress e.g. regarding access to save water and sanitation and revealed undermined trust in the government. Currently, efforts are underway to amend water legislation and streamline institutional arrangements and implementation (DWS, 2019).

4.3. Uzbekistan

Uzbekistan experienced a socio-political shock in 1991 when the Soviet Union collapsed and the country became independent (Fig. 4). The break-up of the Soviet Union literally came as a surprise to many people in the country (Pomfret, 2000). Agriculture in the Uzbek Soviet Socialist Republic (UzSSR) was since the 1960s highly specialized on cotton production through large-scale irrigation. Overuse of water resources resulted in an ecological crisis which became apparent in the 1980s when the fishery in the Aral Sea collapsed and water shortages and soil salinization became increasingly problematic (Micklin, 2007). The pre-shock natural resource governance regime was highly centralized, following a Soviet technocratic management style. After the socio-political change the water management regime changed from Soviet to Uzbek technocratic management without undergoing a transformation. The absence of a transformation despite the urgent need for change to address the looming ecological crisis was the result of key processes and features at multiple levels during all phases of the evolution of the water governance regime.

4.3.1. Before the socio-political shock (preparing)

Before the breakup of the Soviet Union, water management in the UzSSR was characterized by a widespread belief in technical solutions and a technical control paradigm (Schlüter and Herrfahrdt-Pähle, 2011; Wegerich, 2005). Single voices of criticism, e.g. of the cotton monoculture and its negative social and ecological impacts, were disregarded (Obertreis, 2007). The only solution proposed to tackle the looming problems was the diversion of Siberian rivers to Central Asia.

Key features characterizing the preparation phase were a lack of awareness of the need for change (cognitive), strong hierarchies restricting experiments (structural) and a lack of emerging new leaders and fresh ideas (agency) (Tables 4 and A3 in the Appendix). The belief in the superiority of the Soviet ideology over the former feudal system of social organization entailed a disregard of traditional knowledge and a loss of social memory on, for instance, irrigation techniques, which used to be more flexible (Obertreis, 2007). It also led to high degrees of centralization, specialization and division of labor in state farms. Informal institutions gained relevance as a means to circumvent strict social norms and strong state control over citizens. These included using social ties, networks and nepotism for acquiring goods, services and administrative positions. A lack of trust of the central Soviet regime in Central Asian elites and the resulting lack of mobility of cadres to the center supported the development of regional networks (Jones Luong, 2002; Wegerich, 2005). These networks and regional elites influenced the emergence of new, regime-compatible leaders (Heinemann-Grüder and Haberstock, 2007). This, combined with the foreclosure of the Soviet Union towards the western world, prevented the emergence of new ideas or norms, which might have prepared the regime for change.

4.3.2. During the shock and its direct aftermath (navigating I)

After independence, a new water code was quickly adopted to secure water provision to the agricultural sector. It was largely based on Soviet water law and aimed at assuring stability and a continuous production of cotton as a strategic cash crop and source of income for the ruling elites (Veldwisch and Spoor, 2008). The international discourse on Integrated Water Resources Management (IWRM), decentralization and participation in the water sector that also reached Uzbekistan through donor involvement, did not resonate with most of the Uzbek water administration. However, since 1996 a small number of pilot Water User Associations (WUAs) were established with the personal backing of a provincial governor and the support of donors (Veldwisch, 2008) (Fig. 4).

Many key cognitive features from before the shock persisted during the navigation phase (Table 4). The continuity of Soviet-style management prevented the building of trust in the (new) political and administrative regime, and the emergence of new leaders or networks. The strong belief in the role of government as interventionist continued after independence (Jones Luong, 2003). In line with this, new institutions were generally imposed from the top down, which left little room for social learning, self-organization and horizontal linkages (Veldwisch, 2008). As a consequence, new ideas about water governance were not developed within Uzbekistan, but were imported from outside the country, if they entered the national discourse at all. At the same time agency related features were strongly influenced by the persistence of Soviet elites and the entanglement of political power and economic gains through the state order system. With its many opportunities for rent-seeking and corruption, the state order system provided strong incentives for the ruling elites against market-oriented reforms (Jones Luong, 2003).

4.3.3. Long-term developments (navigating II)

In Uzbekistan, the water governance regime did not stabilize. A devastating drought in 2000 and 2001, as a second major environmental shock, triggered minor reforms such as a transition from managing water resources according to administrative to hydrological boundaries (Republic of Uzbekistan, 2003) and the nation-wide implementation of WUAs. The latter, however, was to a large extent a necessary consequence of the 1998 land reforms, which created thousands of new farm entities, i.e. water users, and thus the necessity to add another layer of water administration to deliver water to them (Veldwisch and Mollinga, 2013). The result was a devolution of water management tasks to lower levels, while the financial means and capacity remained on higher levels of administration (Abdullaev and Rakhmatullaev, 2013). However, WUAs in Uzbekistan were organized in a top-down, non-participatory fashion and did not resonate with demands formulated by local population and stakeholders (Sehring, 2009).

Critical structural and agency related elements largely remained unchanged, e.g. the centralized decision-making and oppression of novel ideas or leaders. The top-down imposition of new formal institutions such as WUAs by way of decrees instead of amendments to the water law added to the centralization of power and increased legal uncertainty (Republic of Uzbekistan, 2002; Schlüter and Herrfahrdt-Pähle, 2011; Veldwisch, 2008). During the course of implementation, the WUA concept was highly deformed to suit government interests (e.g. restricted participation and independence) (Veldwisch and Mollinga, 2013), which also involved the integration of WUAs into the existing patronage networks (Sehring, 2009). The dominance of informal institutions over the formal system reduced the pressure to change formal institutions and incentivized actors to reassure existing formal norms, while practicing contradictory informal norms (Hornidge et al., 2013). Despite these shortcomings, WUAs over time, however, became increasingly acknowledged by farmers as useful institutions for local water management (Schlüter and Herrfahrdt-Pähle, 2011).

5. Discussion

The three case studies feature different degrees of transformation of their resource governance regime following socio-political shocks. In Chile and South Africa, transformations have taken place and new governance regimes emerged, albeit their long-term success (Chile) and their successful implementation (South Africa) is questionable. In Uzbekistan no transformation occurred and the old water governance regime persisted with only slight changes that remained within the old paradigm despite the breakup of the Soviet Union. Both, the patterns of cross-level interactions and the key features for transformation offer explanations for these results.

5.1. Patterns of cross-level interactions

The transition literature suggests that transitions at regime level most likely occur if two preconditions are met: first, there is pressure from the landscape level to address unfavorable developments at the regime level and, second, there exist innovative solutions for the perceived problems at the niche level (Geels, 2002). If these innovations have the potential to improve social and ecological structures at different levels of the SES, they can support and strengthen the new regime by a process of selection, learning and adoption (Moore et al., 2014).

We can clearly observe the importance of cross-level interactions for transformation in South Africa and Chile. Here, at the landscape level, new governments requested alternative (more sustainable) natural resource governance regimes while donors pushed for integrated and participatory management. These demands were met by ideas for innovative governance arrangements, resulting from experimentation at the niche level during the preparation phase. In South Africa, innovations developed both at a formal level (through the Commission of Enquiry into Water Matters) and later within informal groups (shadow networks). They created the enabling conditions for a later up-scaling of innovation to the water governance level. The innovations were introduced and adopted into the reform discourse during the navigation phase through learning platforms such as the negotiation forum on water (SCOWSAS). In Chile bridging organizations and learning platforms played a critical role in developing a new vision and practices for coastal management, which was successfully scaled up during the navigation phase through the work of key scientists, support of government and fisher meta-organizations.

A link across levels from the niche to the landscape was largely absent in Uzbekistan. As in the other cases there was a demand for a new water governance regime, however, this was not met by any experimentation at the niche level that could have prepared the system, or bridging organizations that could have connected different levels at any stage of the process from independence to today. The absence of experimentation and the lack of reactivation of pre-Soviet knowledge was in part due to the rigid political regime resulting from 70 years of Soviet ideology, strong state control, repression and deeply rooted cultural factors. After independence, the water sector merely and reluctantly reacted to external developments and requirements from the landscape level (land reform, available donor funding) by introducing minor changes to the existing Soviet water legislation. Some more substantial changes and experimentation such as the introduction of hydrological boundaries and water user associations (WUAs) during the navigation phase were quickly reshaped to fit the existing water governance regime (Veldwisch and Mollinga, 2013; Zavgorodnaya, 2006). This resulted in a reverse transition path (Avelino and Rotmans, 2009), where the innovation was coopted by the status quo system (Westley et al., 2017).

In addition to preparedness and connectivity across scales, the landscape level and its connectivity to external and lower level processes enabled or prevented regime change in other important ways: first, through interactions between different sectors, such as water and agriculture; second, through the connection to global discourses of IWRM and sustainable water governance; and third, through the pace and degree of change at the landscape level itself.

With regard to the first point, changes to the water governance regime in Uzbekistan were strongly influenced by the demands of agriculture because of the dependence of the state budget on irrigated cotton as a cash crop, the lack of financial capital, vested interests of the persistent Soviet leadership and the poor state of the economy. These conditions created strong path dependencies which put immense time pressure on the development of the new water legislation and significantly reduced the size of the window of opportunity (which began to close again already in 1992, when the new water legislation was adopted). The more significant changes initiated after the severe drought in 2001 did not lead to a transformation as they were also eventually suppressed by the rigidity of the regime. The WUAs, for instance, which over time were appreciated by the farmers in part because they adapted them to their needs through bricolage (Sehring, 2009), were rolled back and a process of re-consolidation of small farms was initiated. The rigidity at the landscape level created by vested interests, the importance of agriculture for the state budget in combination with a lack of initiative for change (see below) prevented any innovation or promising initiative from affecting a change in the water governance regime.

Second, the global discourse on IWRM and sustainable water management in the 1980s informed local discussions in South Africa during the preparation phase and thus influenced the development of ideas about new governance forms. By contrast, the Uzbek population was largely precluded from these discourses during Soviet times and had to rely on new impulses for alternative water governance from inside of a highly rigid regime. There was thus not only a lack of re-activation of social-ecological memory but also a lack of new ideas from outside that may have helped develop water governance innovations.

Third, our comparison indicates that the pace and degree of institutional change at the landscape level may influence the outcomes of regime transformation, with too little or too much change being problematic. In Uzbekistan too little change at the landscape level prevented the onset and the development of a transformation. In South Africa, on the contrary, too much change at the landscape level may have hindered progress at the regime level and prevented the stabilization of the new regime. The introduction of a new administrative level (local government) and other reform efforts such as land reforms, stalled the implementation of the new water legislation because of changing or lack of institutional counterparts. Within the water sector itself, high turnover of staff at multiple levels and frequent changes of Ministers, which implied changing emphasis on different aspects of reform, slowed down implementation. Currently, a complete revision of the policy is under way and a merger of the two water acts is discussed (DWA, 2013; DWS, 2019, 2017). It is thus questionable whether the regime has already entered the stabilizing phase or is still meandering in the navigation phase, while at the landscape level rent seeking black elites rise to power (Plaut and Holden, 2012).

Finally, transformations do not end once a new governance regime is institutionalized and implemented. In Chile, fisheries governance has experienced a further transformation after the stabilizing phase. In 2012, Chile acknowledged that the co-managed TURF system was not enough to achieve coastal sustainability and that new complementary governance approaches were necessary to include the management of multiple species in areas which are not TURF areas (Gelcich, 2014). Consequently, Chile passed legislation to create what have been termed Management Plans (Planes de Manejo; Fisheries and Aquaculture Law 20657, 2013). The Management Plan legal framework allows national and local fisheries agencies, in a joint process with artisanal fishers and the fishing industry, to create locally agreed-upon fishery management plans, that can operate at different geographical scales (cove, bay, administrative region, set of regions), for different species or multiple species (Gelcich, 2014). This change offers an enabling condition to shift towards further multi-level governance in small-scale benthic fisheries management, but early assessments to these further transformations are key to fine tune and navigate the process (Gelcich et al., 2019).

5.2. Key features at and across levels that enabled transformational change

Preparedness for change, particularly awareness of a problem, preparation of new knowledge and knowledge integration appeared to be key cognitive features in support of sustainability transformation. Both South Africa and Chile displayed a high level of preparedness and urge for change. In both cases, parts of the population and administration reacted to early signs of crisis by striving for and actively working towards political regime change and improved natural resource governance regimes (within niches). Within these niches, transformative spaces (Pereira et al., 2015) were created, which enabled the generation of new knowledge through discourse, exchange of ideas, and experimentation with new configurations of the SES. A diversity of worldviews, cultural knowledge systems and a perception of the need for change, acted as sources of novelty and transformative capacity (Olsson et al., 2010). This was not the case in Uzbekistan, where a strong desire to remain part of the Soviet Union, a persistent strong belief in a technical control paradigm, a lack of awareness for environmental problems and a belief in the state as problem solver dominated the way of thinking. At the same time, cultural features, such as the perception of water as given from God, the attitude to not complain about (social) wrongs, a give and take mentality and a lack of initiative worked against real change. These results suggest that the availability of a diversity of understandings, but also a belief of non-state actors in the capacity to influence change before and at the time of the political shock are critical for successfully transforming natural resource governance.

Social memory, which has been highlighted as key for preserving desirable practices and knowledge (e.g. Folke et al., 2003) appeared less important in the South African and Uzbek cases. Instead, the way actors dealt with social memory of the previous political regime strongly influenced the development of transformative processes in the water sector. In South Africa, the political will to break with the past and deactivate social memory by exchanging staff was a critical factor. While it resulted in a loss of knowledge, it at the same time provided fresh thinking and a break with former Apartheid rules and practices. In Uzbekistan, however, such unlearning processes (Cummings et al., 2013) that included cutting the ties with (pre-)Soviet social memory did not take place. In Chile, existing social memory was first enhanced with new knowledge about ecological dynamics and social-ecological interactions that was generated in the niche spaces and then networked and combined with knowledge on how to navigate political processes.

As also shown elsewhere (Westley et al., 2011, 2013) leadership and power emerged as important agency-related features. In South Africa, the new Minister turned out to be a strong and motivating leader, who was able to align the political demand for change with the innovations created in niches by a shadow network. In Chile, the government agencies which agreed to financially support the base-line studies to implement TURFs, academics who provided basic science and fisher meta-organizations who built trust between fishers were critical for the navigation phase. However, unless the influence of such leaders is institutionalized, the whole process may break down if key individuals leave (Pahl-Wostl et al., 2013). In Uzbekistan, on the contrary, the persistence of Soviet leadership and existing power structures after the breakup of the Soviet Union and thus the institutionalization of old cadres and networks prevented the introduction of significant change in Uzbek water governance (Sehring, 2009). The strong vested interests of persisting elites in the status quo (i.e. cotton production and state procurement) together with a continued centralization of power acted as critical barriers for transformational change. The socio-political change in the Soviet Union is often described as a collapse but this case shows that much of the structures, values and agency remain. Building on resilience theory and literature such as (Cumming and Peterson, 2017) our results provide a more nuanced view on the relationship between collapse and renewal.

In the three case studies structural features turned out to often have a negative impact on transformation processes, particularly during the stabilizing phase. This may be explained by the fact that structural features such as formal and informal institutions and institutional settings usually take a long time to change since they are driven by cognitive and agency-related changes. In Uzbekistan, persistent structural features such as a low level of trust, a lack of civil society engagement, persistent informal networks dominating formal institutions and strong hierarchies prevented the generation of new knowledge. In Chile, poaching and illegal fishing increased management costs and are eroding the TURFs system (Oyanedel et al., 2018). Shadow networks could be an exception to this pattern, probably because they operate outside the established institutional settings and are thus less influenced by them (which in fact is part of their advantage). Further, in our case studies bridging organizations played a significant role in bringing in and transporting new knowledge and ensuring its institutionalization.

6. Conclusion

Socio-political shocks may constitute windows of opportunity for transforming natural resource governance regimes as has been the case in Chile and South Africa. However, the onset and success of a sustainability transformation critically depends on the interplay of cognitive, structural and agency-related capacities throughout all phases of the transformation. Our results support the notion that transformative capacity is crucial (Brodnik and Brown, 2018; Olsson et al., 2006; Wolfram, 2016; Ziervogel et al., 2016) and that such capacity is different in different phases (Olsson et al., 2014). In the initial phase of a social-ecological transformation, the capacity at the niche level to experiment with novel ideas and social-ecological system configurations is critical, as became evident in the Uzbek case which lacked this capacity. Both the Chilean and South African cases indicate the importance of a capacity to navigate the transition phase by institutionalizing the new governance approach developed in the niche spaces. However, contrary to the Chilean case, the South African case seemed to lack the capacity to implement the new approach in the stabilization phase, a process that was additionally impeded by ongoing processes of socio-political change at the highest national level. Our comparison revealed that features that allow experimenting with novel social-ecological relations, as well as features such as leadership and bridging organizations that support knowledge integration and exchange are of particular importance for social-ecological transformations where understanding of the social and ecological dimensions are needed. We also found that features of resilience that are beneficial in one case such as social networks (Chile), can be detrimental in another (Uzbekistan), highlighting the importance of the context and the history of a specific place.

This research contributes to the increasing number of case studies that inform our understanding of the multiple interacting factors that enable or prevent sustainability transformations (David Tàbara et al., 2018; Fazey et al., 2018; Loorbach et al., 2017; Otto et al., 2020; Patterson et al., 2017; Schot and Kanger, 2018; Waddell et al., 2015). We have engaged in a broad analysis of social-ecological transformations that goes beyond selected parts or phases of a system and beyond leverage points, such as social tipping (Otto et al., 2020). We argue that social tipping alone is not sufficient, but that there needs to be capacities to navigate the tipping process towards a desirable outcome. Our analyses have shown that a successful transformation depends on a number of interacting factors across levels, such as the state of preparedness of the SES, the enabling environment as well as the degree of change at the landscape level, the prevalence of visionary leadership, and the capacity to navigate each phase of the transformation. These insights are particularly interesting for understanding transformations in social-ecological systems that happen beyond the community and neighborhood levels (Olsson et al., 2017; Westley et al., 2011).

Our comparison of three cases of transformation with different outcomes provides a first step towards developing middle-range theories or generalizable insights into processes of transformation in social-ecological systems that take relevant contextual specifics, i.e. sets of conditions that enable or prevent critical sub-processes of a transformation, into account (Schlüter et al., 2019). Our analytical framework, which combines a multi-phase and multi-level perspective with an analysis of critical cognitive, agency and structural features was useful to unravel and compare the causes behind successful and unsuccessful sustainability transformation across cases. It allowed us to scrutinize the interplay of critical processes with enabling or hindering conditions across levels and phases. Its usefulness goes beyond the specific cases of transformation following socio-political change analyzed here and could provide a means for qualitative comparison of more case studies.

The case studies also provide insights in to how agency and strategies for change play out in relation to the “break down” of the existing dominant system, the dynamics of its interactions and, ultimately, its undesired pathways. A successful transformation often entails breaking down resilient structures and processes before building new ones. These insights have practical implications in the way that they can help change-makers to understand when to do what and where. It helps to (1) explore the different capacities needed in the different phases of a transformation, (2) understand how the capacities are linked and how the abilities in one phase also set up the conditions for the next phase, and(3) understand the abilities to switch to new sets of capacities when entering a new phase. Key insights in regards to capacities are: the ability to experiment with new social-ecological system configurations creates novelty in the preparation phase and establishes new attractors, the ability to engage in institutional bricolage and handle conflict and push back in the navigation phase is important for the durability during the stabilization phase, and the ability to transfer values about sustainability and equity supports moving through the navigation phase into institutionalization and the stabilization phase.

Our study also shows the need for further research to explore the different capacities, and their relations and interactions, needed during different phases for achieving transformations to sustainability. Future questions include for instance: Are shocks necessary to unravel rigid structures at high levels of natural resource governance in order to allow for transformation? How critical is the window of opportunity and what can still be achieved once it has closed? How can transformative change in the absence of socio-political shocks be triggered? What are the capacities needed in each phase and how does the presence or absence of such capacities affect the outcome of transformative change? The insights from this study and the questions can guide future analyses of large-scale transformations needed to deal with the Anthropocene challenges (Bai et al., 2016; Ogden et al., 2013; Sachs et al., 2019) such as climate change and transitions to low carbon societies (Geels et al., 2017; Rockström et al., 2017) and solutions for the food, climate and health nexus (Watts et al., 2018). Especially how such transformations can lead to reconfigurations of social-ecological systems’ interactions in ways that enable people and nature to thrive together.

Author statement