Abstract

Background

Survivors of critical illness often experience poor outcomes after hospitalization, including delayed return to work, which carries substantial economic consequences.

Objective

To conduct a systematic review and meta-analysis of return to work after critical illness.

Methods

We searched PubMed, Embase, PsycINFO, CINAHL, and Cochrane Library from 1970 to February 2018. Data were extracted, in duplicate, and random-effects meta-regression used to obtain pooled estimates.

Results

Fifty-two studies evaluated return to work in 10,015 previously employed survivors of critical illness, over a median (IQR) follow-up of 12 (6.25–38.5) months. By 1–3, 12, and 42–60 month follow-up, pooled return to work prevalence (95% confidence interval) was 36% (23–49%), 60% (50–69%), and 68% (51–85%), respectively (τ2=0.55, I2=87%, p=0.03). No significant difference was observed based on diagnosis (acute respiratory distress syndrome [ARDS] versus non-ARDS) or region (Europe versus North America versus Australia/New Zealand), but was observed when comparing mode of employment evaluation (in-person versus telephone versus mail). Following return to work, 20–36% of survivors experienced job loss, 17–66% occupation change, and 5–84% worsening employment status (e.g., fewer work hours). Potential risk factors for delayed return to work include pre-existing comorbidities and post-hospital impairments (e.g., mental health).

Conclusion

Approximately two-thirds, two-fifths, and one-third of previously employed ICU survivors are jobless up to 3, 12, and 60 months following hospital discharge. Survivors returning to work often experience job loss, occupation change, or worse employment status. Interventions should be designed and evaluated to reduce the burden of this common and important problem for survivors of critical illness.

Trial Registration Number

PROSPERO CRD42018093135.

Keywords: Return to Work, Employment, Intensive Care Unit, Critical Illness, Survivor

INTRODUCTION

Rising intensive care unit (ICU) utilization and improvements in critical care medicine have resulted in an ever-expanding population of survivors of critical illness.[1, 2] Following ICU hospitalization, these survivors often experience the “post-intensive care syndrome” (PICS), a constellation of physical, cognitive, and mental health impairments which contribute to disability and poor quality of life.[2] Delayed return to work is common after critical illness, and is likely a consequence of post-ICU impairments, carrying substantial financial consequences for patients, their families, and society.[3]

Despite burgeoning interest in post-ICU outcomes, there remains an incomplete understanding of the epidemiology of delayed return to work after critical illness, including longitudinal trends, associated factors, and lost earnings. Recent studies in previously-employed survivors of critical illness found that 67% and 69% returned to work at 12 and 60 months, respectively, and more than 70% accrued substantial lost earnings[4, 5]. In order to better understand the effects of critical illness on return to work, we conducted a systematic review and meta-analysis of studies evaluating return to work following intensive care unit (ICU) hospitalization in survivors of critical illness.

METHODS

Search Strategy and Selection Criteria

The conduct and reporting of this meta-analysis followed the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines.[6] This meta-analysis protocol was registered on PROSPERO (accessible at: www.crd.york.ac.uk; ID = CRD42018093135). This meta-analysis only involved the return to work outcome detailed in the PROSPERO protocol.

This systematic review and meta-analysis assessed studies that evaluated return to work following intensive care unit (ICU) hospitalization in survivors of critical illness, specifically focusing on return to work prevalence over time and associated patient and clinical variables. To identify eligible studies, we searched five electronic databases (PubMed, Embase, PsycINFO®, CINAHL, and Cochrane Library) from January 1, 1970 to February 14, 2018, with no language restrictions. As prior studies may have evaluated return to work as one of several post-ICU outcomes, without including work-related terms (e.g., “employment”) in the title, abstract, or keywords, a broad search was performed, using keywords “intensive care,” “outcome assessment,” and “follow-up” to capture articles with any assessment of any post-discharge outcomes in survivors of critical illness (full search strategy in Online Data Supplement).[7] To identify eligible studies, we also conducted a hand search of reference lists of relevant articles, along with a search of personal files.

Our inclusion criteria included primary research studies that 1) enrolled adult survivors (≥16 years old) of critical illness, and 2) performed a patient-level evaluation of return to work after hospital discharge. We excluded studies enrolling fewer than 50% ICU patients and with fewer than 20 patients for follow-up. Our aim was to evaluate return to work in general ICU survivors (i.e., hospitalized in medical or surgical ICUs); hence we excluded studies that primarily included patients from specialty ICUs (e.g., cardiac surgery, neurologic/neurosurgical, or trauma ICU). We excluded abstracts and dissertations not published in peer-reviewed journals.

Trained reviewers screened, in duplicate, titles and abstracts, followed by full-text articles, using DistillerSR© (2014 Evidence Partners, Ottawa, Canada). All screening conflicts were resolved by consensus.

Data Analysis

Two independent reviewers (from amongst K.D.S., M.R.S., R.O.H., R.S., K.F.D.) abstracted data from each eligible article, with conflicts resolved by an independent researcher (R.S., K.D.S., K.F.D., or B.B.K.). Data collected from each eligible study included: author, journal, publication year, country, start date, end date, study design, study location, sample size, patient demographics, sample size of patients working before ICU hospitalization, work status during follow-up, predictors of return to work, and secondary outcomes related to employment, such as estimated lost earnings.

Our primary analysis involved estimating the proportion of previously employed survivors reporting return to work after critical illness. First, regarding post-ICU follow-up, prior outcome studies often use 1, 3, 6 and 12 month follow-up time points. In addition, some studies we identified evaluated survivors beyond 12 months, and we determined that 18 to 36 and 42 to 60 months were logical cut points based on the data. Next, for studies reporting proportions of previously employed ICU survivors returning the work, we calculated log odds of return to work at each follow-up time point. Random-effects meta-regression of the log odds was then used to estimate pooled proportions of return to work as a function of follow-up time (categorical: 1 to 3, 6, 12, 18 to 36, 42 to 60 months); this model was fit via a restricted maximum likelihood Knapp-Hartung modification to estimate between-study heterogeneity (τ2), given a small number of studies available at each follow-up time.[8] Pooled log odds estimates were back-transformed to proportions and presented with corresponding 95% confidence intervals (CIs). An I2 statistic estimated residual heterogeneity, and a p-value calculated to test the null hypothesis of no differences in pooled proportions across follow-up time.

Our primary analysis included only studies evaluating return to work at the defined follow-up time points. For studies with multiple data within a follow-up time points (e.g., 24 and 36 months), we included only the data most distant from ICU discharge as some studies reported rising employment rates over time. Subgroup analyses were conducted evaluating factors that are thought to influence return to work: (1) ICU admission diagnosis category, specifically acute respiratory distress syndrome [ARDS] vs. non-ARDS (other diagnoses [i.e., sepsis] were infrequent and, as such, further subgroup analyses were not conducted; (2) geographic region (Europe versus North America versus Australia/New Zealand); and (3) mode of employment evaluation (in-person versus telephone interview versus mailed questionnaire), to account for possible reporting differences.[9] Additionally, to evaluate for temporal trends in employment, a subgroup analysis was conducted involving enrollment dates (pre-1990, 1991–2000, 2001–2010, 2011-current). These subgroup analyses were conducted by including the main term for subgroup (categorical) and an interaction of the subgroup and follow-up time categories. We were unable to evaluate other variables of interest including survivors’ age, severity of illness, and length of stay with return to work, as the majority of studies did not report these variables for the subpopulation that was previously employed. Sensitivity analyses included a) including studies with non-discrete follow-up times, using the chronologically latest value for follow-up time reported in the study (i.e., 3rd quartile if median [IQR] reported and maximum if median [range] reported); and b) extending the primary analysis model to include an indicator of whether the employment data was collected during periods of global economic downturn (i.e., 2008 to 2010) to further evaluate for temporal trends in employment.

Risk of bias was independently assessed by two reviewers (from amongst K.D.S. and/or M.R.S. and/or R.O.H or K.D.S. and/or R.S. and/or K.F.D.), using the Newcastle Ottawa Scale[10] for observational studies, including those conducted as longitudinal follow-up of randomized controlled trials. Disagreements were resolved by consensus. Publication bias was assessed visually using funnel plots, and quantitatively using the Egger statistical test [11, 12] [12]. A two-sided p<0.05 was considered statistically significant. All analyses were performed using STATA version 15.1 (College Station, TX).

RESULTS

Our search yielded 41,977 articles; after removal of duplicates, 26,877 abstracts were reviewed, of which 2,754 were reviewed as full text. After excluding 2,689 articles and adding 8 articles from personal files, 73 potential citations were identified. Among these articles, 52 unique studies evaluated return to work in previously employed ICU survivors (Figure 1, Table 1, eTable 2).[4, 5, 13–63] These studies included 13 retrospective[16, 18, 23, 30, 33, 39, 42, 43, 47, 48, 52, 56, 62] and 39 prospective[4, 5, 13–15, 17, 19–22, 24–28, 30–32, 34–38, 40, 41, 44–46, 49–51, 53–55, 57–61, 63] cohort studies, of which 3 were longitudinal follow-up within a randomized trial.[4, 37, 59] Eleven (21%) studies included more than one follow-up time point after discharge.[4, 5, 26, 28, 29, 34, 37, 45, 49, 51, 55, 62] Fourteen (27%) studies were published between 1984–2000, 17 (33%) from 2001–2010, and 21 (40%) from 2011–2018. Eleven studies conducted employment assessments during either the first (2000–2004) or second (2008–2010) global economic downturns occurring during the publication period.[4, 32, 36, 46–48, 50–52, 55, 63, 64] Twenty eight (54%) studies were conducted in Europe,[15, 17, 18, 20, 22, 25–27, 30–36, 38–42, 44, 48–51, 58, 62, 63] 14 (27%) in North America,[4, 5, 13, 14, 16, 19, 23, 24, 28, 29, 37, 45, 52, 55, 60] 8 (15%) in Australia/New Zealand,[21, 43, 46, 47, 53, 54, 59, 61] and 2 (4%) in Asia.[56, 57] Nine studies (17%) evaluated return to work in survivors of acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS).[4, 5, 19, 24, 39, 45, 47, 57, 63] Employment evaluation occurred via in-person visit in 18 (35%) studies,[18, 19, 21, 26–29, 31, 36, 39, 43, 45, 50, 55, 57–60, 63] telephone interview in 18 (35%) studies,[4, 5, 13–15, 23, 30, 32, 34, 42, 46, 47, 49, 52–54, 56, 61] mailed questionnaire in 15 (29%) studies,[16, 17, 20, 22, 24, 25, 33, 35, 37, 38, 40, 41, 44, 48, 51] and national database in 1 study.[62] The majority of studies used “had returned to work”, “back to work”, “working”, or multiple phrases to describe survivors’ post-ICU employment status, and did not report the specific employment question(s) used, the timing of return to work, or status of survivors who had not returned to work (i.e., retirement, unemployment, disability). Three studies differentiated whether previously employed survivors were currently working or had ever returned to worked at the time of post-ICU follow-up[4, 5, 62]. Eleven (21%) studies evaluated factors associated with return to work.[4, 5, 19, 37, 44, 45, 51, 54, 55, 61, 62, 65] Notably, four (8%) studies enrolled patients who were seen in a multi-disciplinary ICU survivor clinic,[21, 50, 58, 60] of which one evaluated an intervention to improve return to work.[58]

Figure 1. Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) flow diagram.

Table 1. Summary of 52 studies included in review.

| Author Year (Country) |

Study design, location, population studied, employment instrumenta | Enrollment: Sample size and demographics | Employed before ICU, % (n/N) | Post-ICU Return to Work Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Parno et al. 1984 (USA)[13] | Prospective, medical-surgical ICU, any patient, mailed questionnaire | N = 217; mean age (SD) = 55 (4.6) | 45% (97/216) | 61% (59/97) returned to work at 24m |

| Goldstein et al. 1986 (USA)[14] | Prospective, medical & cardiac ICU, any patient, mail/telephone interview | N = 2213; mean age = 64 to 65b | 30% (656/2213) | 65% (360/549) returned to work at 12m |

| Zaren & Hedstrand 1987 (Sweden)[15] | Prospective, general ICU, age ≤64 years old, telephone interview | N = 717; mean age (SD) = 50 (19), 44% female | 65% (339/518) | 75% (254/339) returned to work at 12m |

| Mundt et al. 1989 (USA)[16] | Retrospective, medical-surgical ICU, any patient, mailed questionnaire | N=887; mean age (SD) = 59 (18), 43% female | 47% (419/887) | 70% (295/419) returned to work at 6m |

| Ridley & P. Wallace 1990 (UK)[17] | Prospective, general ICU, any patient, mailed questionnaire | N = 156 | 35% (48/136) | 79% (38/48) returned to work between 12 to 36m |

| Doepel et al. 1993 (Finland)[18] | Retrospective, general ICU, severe acute pancreatitis, in-person interview | N = 37; mean age (range) = 49 (26 to 90), 32% female | 84% (31/37) | 70% (26/37) returned to work at mean 74m (range 12 to 168m) |

| McHugh et al. 1994 (USA)[19] | Prospective, multiple ICU, ARDS requiring intubation, in-person interview | N = 37; mean age = 41, 38% female | 73% (27/37) | 56% (15/27) returned to work at 12m |

| Bell & Turpin 1994 (UK)[20] | Prospective case-control, general & cardiac ICU, any patient, mailed questionnaire | N = 172; mean age = 54 to 63, 39% femaleb | 42%c (66/156)d | 63% (35/56) returned to work at 3mb,c,d |

| Daffurn et al. 1994 (Australia)[21] | Prospective, general ICU, present >48hrs, clinic visit | N = 54; mean age (SD) = 51 (18) | 44% (24/54) | 50% (12/24) returned to work at 3m |

| Munn et al. 1995 (UK)[22] | Prospective, general ICU, any patient, mailed questionnaire | N = 504 | 59% (123/207) | 30% (37/123) returned to work at 3m |

| Fakhry et al. 1996 (USA)[23] | Retrospective, surgical ICU, present in ICU >14d, mail/telephone interview | N = 39; mean age = 53, 31% female | 58% (11/19) | 45% (5/11) returned to work at mean 18m (range 4 to 30m) |

| Weinert et al. 1997 (USA)[24] | Prospective, general ICU, acute lung injury, mailed questionnaire | N = 24; mean age (SD) = 40 (12), 33% female | 54% (13/24) | 54% (7/13) returned to work at median 15m (range 6 to 41m) |

| Hurel et al. 1997 (France)[25] | Prospective, medical-surgical ICU, any patient, mailed questionnaire | N = 223; mean age (SD) = 52 (18), 44% female | 30% (68/223) | 62% (42/68) returned to work at 6m |

| Eddleston et al. 2000 (UK)[26] | Prospective, general ICU, any patient, in-person questionnaire | N = 143; mean age (SD) = 49 (12), 48% female | 33% (47/143) | 23% (11/47) returned to work at 3m 49% (23/47) returned to work at 6m 79% (37/47) returned to work at 12m |

| Wehler et al. 2001 (Germany)[27] | Prospective, medical ICU, present in ICU >24hrs, telephone interview | N = 185; mean age (SD) = 56 (18), 44% female | 25% (46/185) | 98% (45/46) returned to work at 6m |

| Chelluri et al. 2002 and 2004 (USA)[28, 29] | Prospective, multiple ICUf, intubated >48hrs, in-person interview | N = 817; mean age (SD) = 60 (19), 46% female | 23% (176/772) | 18% (32/176) returned to work at 2m 34% (32/93) returned to work at 12m |

| Haraldsen & Andersson 2002 (Sweden)[30] | Retrospective, surgical ICU, abdominal sepsis, mail/telephone interview | N = 49; median age = 67 | 47% (23/49) | 74% (17/23) returned to work at median 72m (range 24 to 178m) |

| Wehler et al. 2003 (Germany)[31] | Prospective, medical ICU, present in ICU >24hrs, telephone interview | N = 318; mean age (SD) = 57 (17), 42% female | 32% (102/318)d | 91% (64/70) returned to work at 6m |

| Lizana et al. 2003 (Belgium)[32] | Prospective, medical-surgical ICU, any patient, telephone interview | N = 96; median (IQR) age = 60 (42, 75), 36% female | 47% (45/96) | 62% (28/45) returned to work at 18m |

| Halonen et al. 2003 (Finland)[33] | Retrospective, surgical & general ICU, severe pancreatitis, mailed questionnaire | N = 145; mean age = 44, 17% female | 68% (99/145) | 87% (86/99) returned to work at median 66m (range 19 to 127m) |

| Cuthbertson et al. 2005 (UK)[34] | Prospective, general ICU, any patient, telephone interview | N = 300; median age = 61, 41% female | 39% (67/173) | 25% (17/67) returned to work at 3m 49% (33/67) returned to work at 6m 58% (39/67) returned to work at 12m |

| Graf et al. 2005 (Germany)[35] | Prospective, medical ICU, present >24hr, mailed questionnaire | N = 173; mean age (SD) = 61 (13), 25% female | 53% (91/173) | 23% (21/91) retuned to work at 60m |

| Cinquepalmi et al. 2006 (Italy)[36] | Prospective, surgical ICU, pancreatic necrosis surgery, clinic visit | N = 35; mean age (SD) = 55 (11), 29% female | 100% (32/32) | 38% (12/32) returned to work at 6m |

| Longo et al. 2007 (Canada)[37] | Prospective (post-RCT), general ICU, severe sepsis, mailed questionnaire | N = 98; mean age (SD) = 60 (17), 48% female | 21% (21/98)g | 76% (16/21) returned to work at 1m 86% (18/21) returned to work at 7m |

| Ylipalosaari et al. 2007 (Finland)[38] | Prospective, general ICU, present in ICU >48hrs, mailed (80%) and telephone (20%) questionnaire | N = 142; median (IQR) age = 57 (43, 69), 39% female | 33% (47/142) | 36% (17/47) returned to work at median 24m (interquartile range 21 to 28m)d |

| Linden et al. 2009 (Sweden)[39] | Retrospective, general ICU, ARDS requiring ECMO, in-person questionnaire | N = 21; mean age = 40, 43% female | 100% (21/21) | 76% (16/21) returned to work at mean 26m (range 12 to 50m) |

| van der Schaaf et al. 2009 (Netherlands)[40] | Cross-sectional, general ICU, present in ICU >48hrs, mailed questionnaire | N = 255; mean age (SD) = 59 (17), 34% female | 33% (82/251) | 54% (44/82) returned to work at 12m |

| van der Schaaf et al. 2009 (Netherlands)[41] | Prospective, medical-surgical ICU, receiving MV >48hrs, mailed questionnaire | N = 30; mean age (SD) = 57 (16), 40% female | 40% (12/30) | 42% (5/12) returned to work at 12m |

| Poulsen et al. 2009 (Denmark)[42] | Retrospective, general ICU, septic shock, telephone interview | N = 70; median (IQR) age = 59 (46, 67), 21% female | 33% (23/70) | 43% (10/23) returned to work at 12m |

| Kelly & McKinley 2010 (Australia)[43] | Retrospective, general ICU, present in ICU >48hrs, clinic/phone interview | N = 39; mean age (SD) = 60 (16), 41% female | 36% (14/39) | 43% (6/14) returned to work at mean 3.5m (range 1 to 7 months) |

| Myhren et al. 2010 (Norway)[44] | Prospective, general ICU, present in ICU >24hrs, mailed questionnaire | N = 194; mean age (SD) = 49 (15), 40% female | 63% (122/194) | 55% (67/122) returned to work at 12mh |

| Herridge et al. 2011 (Canada)[45]i | Prospective, medical-surgical ICU, ARDS requiring MV, clinic or home visit | N = 83; median (IQR) age = 45 (36, 56), 45% female | 77% (64/83) | 63% (40/64) returned to work at 12m 92% (49/53) returned to work at 60m |

| Dennis et al. 2011 (Australia)[46] | Prospective, medical-surgical ICU, present in ICU >48hrs, telephone interview | N = 77; mean age (SD) = 54 (18), 42% female | 45% (32/71) | 50% (16/32) returned to work at 6m |

| Luyt et al. 2012 (France)[63] | Prospective case-control, general ICU, H1N1 influenza with ARDS, in-person questionnaire | N = 37, median (IQR) age 39 (32, 49), 51% femalej | 78% (29/37) | 90% (26 of 29) returned to work at 12m |

| Hodgson et al. 2012 (Australia)[47] | Retrospective, general ICU, ARDS requiring ECMO, telephone interview | N = 21; mean age (SD) = 36 (12), 52% female | 100% (15/15) | 53% (8/15) working at median 8.4m (range 6 to 16m) |

| Kowalczyk et al. 2013 (Poland)[48] | Cross-sectional, general ICU, present in ICU >24hrs, mailed questionnaire | N = 186; mean age (SD) = 48 (19), 42.5% female | 55% (102/185) | 48% (49/102) returned to work at 12–60m |

| Cuthbertson et al. 2013 (Scotland)[49] | Prospective, adult ICU, severe sepsis, telephone interview | N = 439; median age = 58 (45, 67), 47% female | 73% (62/85) | 85% (53/62) returned to work at 42mk 79% (46/58) returned to work at 60mk |

| Fonsmark & Nielsen 2015 (Denmark)[50] | Prospective, medical-surgical ICU, present in ICU >4d & in hospital >10d, in-person interview | N = 101; median (IQR) age = 60 (49, 66), 39% female | 49% (49/101) | 33% (16/49) returned to work at ≥2m |

| Quasim et al. 2015 (UK)[51] | Prospective, general ICU, any patient, mailed questionnaire | N = 75j | 54% (28/52) | 46% (11/24) returned to work at 12ml 64% (18/28) returned to work at median 27m (range 24 to 29m) |

| Pratt et al. 2015 (USA)[52] | Retrospective, ICU, 90-day survivors of severe shock, telephone interview | N = 76; mean age (SD) = 55 (17), 47% female | 47% (17/36) | 53% (9/17) returned to work at mean±SD 60±16m (range 36 to 84m) |

| Team Study 2015 (AUS & NZ)[53] | Prospective, ICU, requiring MV >48hrs, telephone interview | N = 192; mean age (SD) = 58 (16), 39% female | 64% (77/120) | 38% (29/77) returned to work at 6m |

| Reid et al. 2016 (Australia)[54] | Prospective, general ICU, any patient requiring MV, telephone interview | N = 39; mean age (SD) = 56 (2), 23% female | 51% (18/35)m | 50% (9/18) returned to work at 12m |

| Norman et al. 2016 (USA)[55] | Prospective, medical-surgical ICU, respiratory failure or cardiogenic shock or septic shock, questionnaire | N = 113; median (IQR) age = 53 (44, 60), 39% femalej | 26% (115/446) | 42% (48/113) returned to work at 3m 52% (49/94) returned to work at 12md |

| Yang et al. 2017 (China)[56] | Retrospective, general ICU, severe pancreatitis for >14d, telephone interview | N = 214; median (IQR) age = 45 (38, 52), 34% female | 34% (73/214)n | 66% (48/73) returned to work at median 17m (IQR 10 to 24m)o |

| Wang et al. 2017 (China)[57] | Prospective, general ICU, severe ARDS, in-person interview | N = 72; mean age (SD) = 42 (15), 29% femalep | 100% (72/72) | 56% (40/72) returned to work at 12mm |

| McPeake et al. 2017 (Scotland)[58] | Prospective, medical-surgical ICU, level 3 stay x 72hrs or level 2 stay x 14d & age<65,q clinic visit | N = 40; median (IQR) age = 51 (43, 57), 38% female | 43% (17/40) | 88% (15/17) returned to work at 12m |

| Kamdar et al. 2017 (USA)[4]r | Prospective (post-RCT), medical or surgical ICU, ARDS, telephone interview | N = 825; mean age = 45 to 54, 52% femalek | 47% (386/825) | 55% (214/386) ever returned to work at 6m 67% (253/379) ever returned to work at 12m |

| Kamdar et al. 2018 (USA)[5] | Prospective, medical or surgical ICU, ARDS, telephone interview | N = 138; median age = 46 to 49, 46% femalej | 49% (67/138) | 49% (33/67) ever returned to work at 12m 55% (37/67) ever returned to work at 24m 60% (40/67) ever returned to work at 36m 66% (43/65) ever returned to work at 48m 69% (44/64) ever returned to work at 60m |

| Haines et al. 2018 (Australia)[59] | Prospective (post-RCT), mixed ICU, present in ICU >5d, in person questionnaire | N = 56; mean age (SD) = 59 (14), 39% female | 52% (29/56) | 69% (20/29) returned to work at 54m |

| Sevin et al. 2018 (USA)[60] | Prospective, medical ICU, at risk for Post Intensive Care Syndrome, in person interview | N = 62; median (IQR) age = 50 (36, 57), 45% female | 76% (47/62) | 15% (7/47) returned to work at 1m |

| Hodgson et al. 2018 (Australia)[61] | Prospective, general ICU, >24hrs MV, telephone interview | N = 107; mean age = 47 to 53, 27% femalej | 41% (107/262) | 71% (76/107) returned to work at 6m |

| Riddersholm et al. 2018 (Denmark)[62] | Retrospective, ICU, present in ICU >72hrs & working prior to admission, country database | N = 5,762; median (IQR) age = 50 (38, 58), 36% femalej | 100% (5,762/5,762) | 60% (3,457/5,762) ever returned to work at 12md 68% (3,918/5,762) ever returned to work at 24md 74% (4,274/5,762) ever returned to work over median 6.4y (95% CI 6.1 to 6.6y) |

ARDS = acute respiratory distress syndrome; d = days; ECMO = extracorporeal membrane oxygenation; hrs = hours; ICU = Intensive Care Unit; m = months; MV = mechanical ventilation; RCT = randomized controlled trial; RTW = return to work

Cohort studies unless noted otherwise

Mean/Median age not provided for total population. Paper provided mean/median for groups within total population.

Proportion estimated from bar graph

Numerator not provided. Calculated using other available data.

Full-time workers who returned to full-time work.

Medical, Neurologic, Trauma, Surgical ICU

Merged two populations: patients receiving Activated Protein C (APC) and no APC

Includes patients returning to school

Study involved two secondary analyses evaluating risk factors for RTW[65]

Included baseline data specifically for previously-employed survivors

Included 25 of 62 (40%) and 24 of 58 (41%) of 42m and 60m survivors reporting “I work less” compared to pre-ICU

Data published in another study[58]

Merged from two populations: patients receiving 1 vs. 1.5 kCal/mL enteral nutrition

Merged from two populations: patients with and without persistent inflammation-immunosuppression and catabolism syndrome (PICS) after severe acute pancreatitis

Denominator not provided; calculated using other available data.

Merged from two populations: patients receiving and not receiving ECMO

Levels refers to the UK Intensive Care Society definition of ICU patients

The included studies evaluated return to work in 10,015 (median = 48.5, interquartile range [IQR] 25.5 to 94, range = 11 to 5,762) previously employed ICU survivors, with a median maximum follow-up time of 12 (IQR = 6.25 to 38.5, range = 1 to 178) months. Five (10%) studies reported a median time to return to work, ranging from 10 to 29 weeks.[4, 5, 30, 57, 62, 63] Six (12%) studies provided demographic and/or ICU data specifically for previously employed survivor subcohort.[4, 5, 51, 55, 57, 61–63] Additionally, four (8%) studies documented death, loss to follow-up, and participation refusal specifically among previously employed survivors, with rates of 3% (20 of 631), 6% (36 of 631), and 1% (6 of 631), respectively, across longitudinal follow-up.[4, 5, 55, 56] In risk of bias evaluation of the 52 observational studies, 46% did not have adequate representativeness of the exposed cohort, and 52% did not have adequate follow-up (eTable 6, eFigure 2). The funnel plots and Egger tests did not support evidence of publication bias, based on follow-up time point category (eFigures 3 and 4).

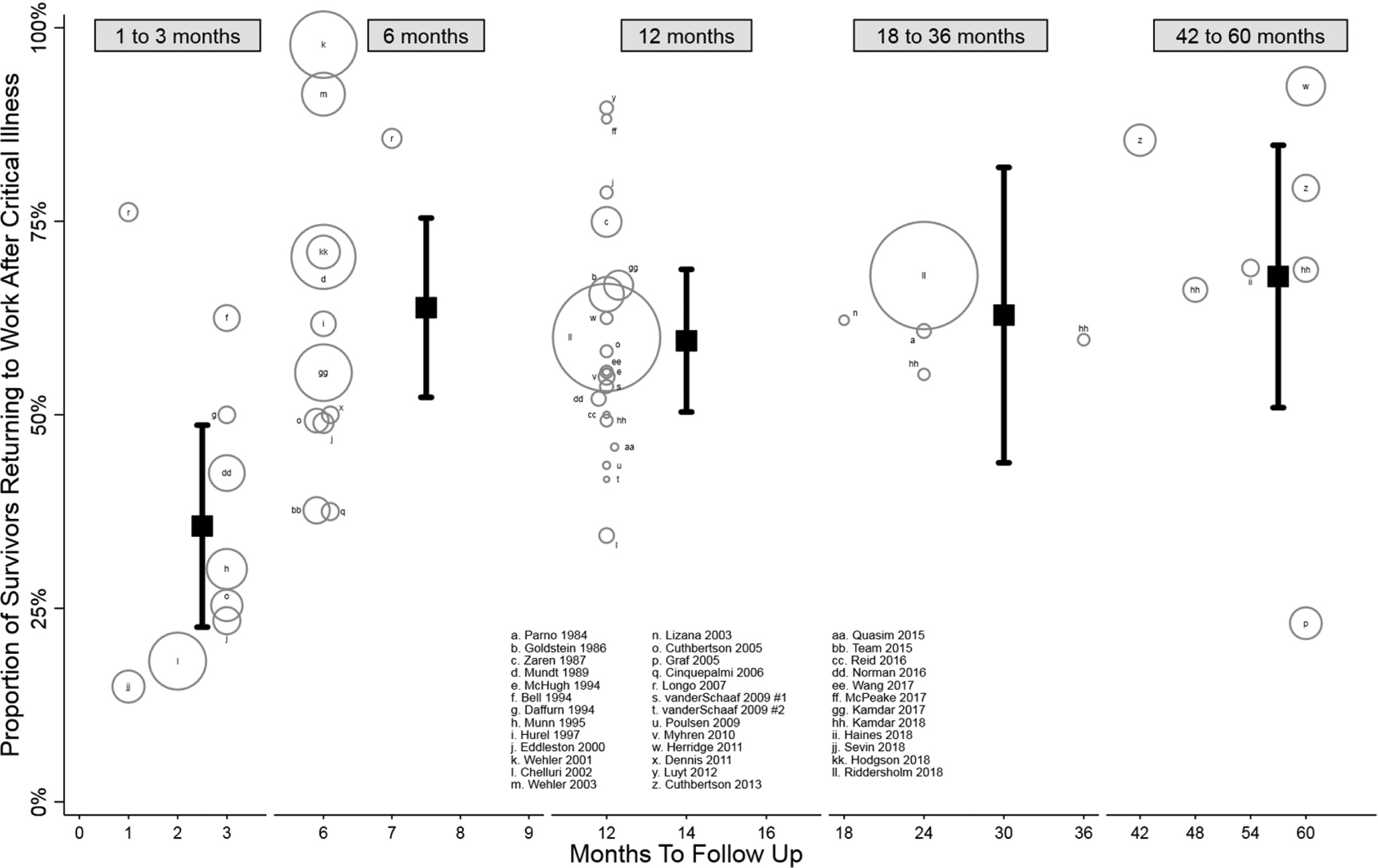

When evaluating the 38 studies with discrete follow-up time points, we estimated pooled 1 to 3, 6, 12, 18 to 36, and 42 to 60 month return to work prevalence (95% CI) of 36% (23–49%), 64% (52–75%), 60% (50–69%), 63% (44–82%), and 68% (51–85%), respectively (τ2=0.55, I2=87%, p=0.03) (Figure 2, eTable 3). These results did not differ substantially (p=0.65) when including the 11 studies[17, 23, 24, 30, 33, 38, 39, 43, 48, 50, 51] reporting only non-discrete follow-up time points (eTable 4, eFigure 1).

Figure 2.

Proportion of survivors returning to work after critical illness, among 38 studies with discrete follow-up time points. Black squares represent pooled proportions (with 95% confidence intervals) by that time point: 36% (23–49%) by 1 to 3 months, 64% (52–75%) by 6 months, 60% (50–69%) by 12 months, 63% (44–82%) by 18 to 36 months, and 68% (51–85%) by 42 to 60 months. Pooled estimates calculated using random effects meta-regression. For the 3 pairs of estimates falling within the same follow-up stratum, only the final follow-up point estimate was included. Bubbles represent 53 point estimates from the 38 studies, with bubble size corresponding to study sample size.

In subgroup analyses of studies only including discrete follow-up time points, significant return to work differences, stratified by follow-up time point, were not observed when comparing disease category (eTable 3), region (eTable 3), or date of enrollment (Online Data Supplement), but were observed when comparing mode of employment evaluation (eTable 3). Sensitivity analyses yielded no significant differences (Online Data Supplement). Among secondary outcomes reported, previously employed survivors often received new disability benefits and incurred substantial lost earnings, totaling up to US $26,949 at 12 months and $180,221 60 months after critical illness (Table 2, Online Data Supplement). Additionally, among survivors who returned to work, 5–84% were working less or subsequently retired, 17–66% changed occupations, and 20–36% subsequently incurred job loss (Table 2, Online Data Supplement).

Table 2. Secondary Outcomes Associated with Return to Work After Critical Illness.

| Theme | Month | Outcome |

|---|---|---|

| Decline in post-ICU employment status | 3 | 17% newly part-time[20], 15–23% worse work status[20] |

| 6 | 4 of 29 (14%)[53], 25 of 107(23%)[61], 80 of 190 (42%)[4] working less | |

| 12 | 28 of 549 (5%)[14] and 85 of 191 (45%)[4] working less, 79 of 94 (84%) newly part-time or unemployed[55] | |

| 36 | 9 of 39 (23%) worse work status[17] | |

| 60 | 17% to 33% increase in part-time work[52]; 59% manual vs. 45% white-collar workers not RTW[48] | |

| Occupation change | 6 | 22 of 107 (21%) changed occupation[61] |

| 12 | 79 of 257 (31%) changed occupation[4] | |

| 18 | 66% changed occupation due to physical limitations caused by illness[23] | |

| 29 | 3 of 18 (17%) who RTW took on different role due to health issues[51] | |

| Poor work performance | 12 | 69 of 257 (27%)[4] reduced effectiveness at work |

| Job loss after returning to work | 12 | 69 of 257 (27%)[4], 1,235 of 4,274 ever RTW (29%) lost job within 12 months[62] |

| 60 | 12 of 33 (36%), of whom 6 (50%) lost job due to illness[5] | |

| 127 | 17 of 86 (20%)[33] | |

| Illness or poor health affecting return to work | 3 | 5–11%[20] not RTW due to health |

| 6 | 31 of 107 (29%)[61], 19 of 68 (28%)[25], 41 of 72 (57%)[4] not RTW due to health | |

| 12 | 37 of 251 (15%)[40], 6 of 12 (50%)[41], 82 of 107 (77%)[72] not RTW due to health | |

| 28 | 26 of 47 (55%)[38] not RTW due to health | |

| 29 | 6 of 28 (21%)[51] not RTW due to sickness | |

| 41 | 6 of 13 (46%)[24] not RTW due to health | |

| 54 | 5 of 29 (17%)[59] not RTW due to health | |

| 84 | 10 of 17 (59%) previously employed had new disability[52] | |

| Receiving new disability benefits | 6 | 57 of 549 (10%)[14], 56 of 386 (15%)[4] |

| 12 | 76 of 379 (20%)[4], 18 of 67 (27%)[5] | |

| 24 | 20 of 67 (30%)[5] | |

| 36 | 20 of 65 (31%)[5] | |

| 48 | 21 of 64 (33%)[5] | |

| 60 | 7 of 23 (30%)[30] | |

| 72 | Pre-post ICU increase from 46 of 70 (66%) to 59 of 70 (84%)[42] | |

| 76 | Never RTW: 89%[62]; job loss within one year of RTW: 59%[62] | |

| Newly retired after critical illness | 6 | 30 of 419 (7%)[16], 14 of 386 (4%)[4] |

| 12 | 15 of 93 (16%)[28], 6 of 82 (7%)[40]; 1 of 12 (8%)[41], 5 of 18 (28%)[54], 15 of 379 (4%)[4] | |

| 18 | 2 of 45 (4%)[32] | |

| 24 | 2 of 53 (4%)[45], 3 of 67 (4%)[5] | |

| 26 | 2 of 21 (10%)[39] | |

| 27 | 1 of 28 (4%)[51] | |

| 36 | 4 of 67 (6%)[5] | |

| 48 | 4 of 65 (6%)[5] | |

| 60 | 5 of 64 (8%)[5] | |

| 74 | 5 of 31 (16%)[18] | |

| 76 | 111 of 1,235 (9%) retired within one year of return to work [62] | |

| Psychological Outcomes | 6 | Not RTW: worse disability scores, health status, anxiety, depression[61], QOL[25] |

| 12 | RTW: higher HRQOL, fewer depression symptoms[44] | |

| 29 | RTW: higher QOL[51] | |

| 60 | RTW: lower anxiety, depression scores[48] | |

| Lost earnings | 12 | 71% accrued lost earnings, mean (SD) US$26,949 (22,447) (60% of pre-ICU income)[4]; €1,482–1,513 lower yearly income in non-retired survivors returning to work[62] |

| 60 | 77% accrued lost earnings, mean (SD) US$180,221 (110,285) (55% of pre-ICU income)[5] | |

| Change in healthcare coverage | 12 | Unemployed/disabled: 14% decline in private insurance, 16% rise in Medicare/Medicaid[4] |

| 60 | Unemployed/disabled: 33% decline in private insurance, 37% rise in Medicare/Medicaid[5] |

HRQOL = Health-related quality of life; ICU = intensive care unit; QOL = quality of life; RTW = return to work

Eleven studies reported risk factors for delayed return to work after critical illness (Table 3, eTable 5).[4, 5, 19, 37, 44, 45, 51, 54, 55, 61, 62, 65] Possible predictors of delayed return to work (i.e., >50% of studies demonstrating a similar positive finding) included lower education, pre-existing comorbidities, non-trauma admission, discharge to non-hospital location, and mental health impairments following hospital discharge.

Table 3.

| Total Number of Studies | % | % |

|---|---|---|

| 2 | 50% | 50% |

| 3 | 67% | 33% |

| 1 | 100% | 0% |

| 3 | 33% | 67% |

| 1 | 100% | 0% |

| 4 | 0% | 100% |

| 1 | 100% | 0% |

| 2 | 0% | 100% |

| 6 | 50% | 50% |

| 4 | 50% | 50% |

| 2 | 50% | 50% |

| 1 | 100% | 0% |

| 4 | 50% | 50% |

| 3 | 33% | 67% |

| 2 | 50% | 50% |

| 4 | 50% | 50% |

| 5 | 20% | 80% |

| 2 | 0% | 100% |

ICU = Intensive Care Unit

Includes all risk factors identified via univariable or multivariable analysis, with p<0.05 denoting significance. Detailed study-by-study findings provided in eTable 5.

Excludes 1 study (Longo et al. 2007[37]) suggesting delayed return to work in patients not receiving activated protein C.

DISCUSSION

Our systematic review identified 52 studies that evaluated return to work in previously employed survivors of critical illness. Delayed return to work and joblessness are common and persistent issues, with approximately two-thirds, two-fifths, and one-third jobless up to 3, 12, and 60 months after ICU hospitalization. Significant differences in return to work were not observed when evaluated according to ICU admission diagnosis category (ARDS versus non-ARDS) or geographic region but were observed when different modes of employment evaluation (in-person versus telephone versus mail) were utilized. Previously employed survivors frequently required new disability benefits and accrued substantial lost earnings, and those who did return to work were vulnerable to subsequent job loss, occupation changes, and worsening employment status.

As part of growing interest in post-ICU outcomes, we observed an increase in research studies that evaluated return to work following critical illness. Our analysis of 10,015 previously employed survivors demonstrated that 36%, 64%, 60%, 63%, and 68% of survivors had reported returning to work by 1 to 3, 6, 12, 18 to 36, and 42 to 60 month follow-up. Although our review included general medical-surgical survivors and excluded those in neurological intensive care, our return to work rates were similar to or exceeded the rates observed following traumatic brain injury [66] and stroke.[67] While our analysis was limited by substantial heterogeneity, in particular timing and modes of employment evaluation, we observed consistent trends in return to work over time, culminating in nearly one-third of survivors having not returned to work up to 60 months after critical illness.

In subgroup and sensitivity analyses, we found few differences in return to work by geographic region or when evaluated during economic downturn, suggesting little influence of societal or economic factors on the findings. Additionally, we observed no significant difference based on ICU admission diagnosis (ARDS versus non-ARDS). Lastly, significant return to work differences were observed when comparing different types of follow up; notably, studies involving mailed questionnaire reported a particularly high return to work prevalence (53%) at 1 to 3 months. Given that 1 to 3 month response rates by mail were more than 50% lower than in-person/telephone rates (22% versus 48%), it is possible that only survivors who returned to work were able to respond to mailed questionnaires. While death, loss to follow-up, and refusal rates were low (1–6%) in previously employed survivors undergoing serial in-person or telephone evaluations, the majority of studies used return to work as a secondary outcome and did not report these data. Trials incorporating return to work as a primary outcome could report these data and perform a more detailed investigation of variables preventing or promoting return to work. Future research should consider direct and standardized return to work assessments while determining core data elements and the optimal timing of data collection. Additionally, qualitative and quantitative studies could focus on patient-reported reasons for delayed return to work, modeling these factors with variables gathered during the trial.

Notably, despite an overall rise in return to work over time, there was a decline between 6 and 12 months, suggesting that for some individuals, working was short-lived. This observation was supported by two longitudinal studies reporting fixed or declining employment rates with concomitant increase in job loss (8 to 14% increase from 6 to 12 months and 12% to 25% increase from 24 to 60 months),[4, 5] and a national database study of 5,762 patients reporting a cumulative incidence of job loss (after return to work) of nearly 50% 3 years after intensive care.[62] Though no study evaluated risk factors for subsequent job loss after return to work, lasting physical, cognitive, and mental health impairments following critical illness may play a role.[1, 2] Several studies suggested an association of joblessness with depression, anxiety, and poor quality of life, with improved mental health and quality of life after return to work.[25, 44, 45, 48, 51, 61, 65] Given the cross-sectional nature of these studies, the directionality of associations is unclear. However, there is known a negative impact of depression and anxiety on return to work, particularly when combined with somatic illness.[68] Longitudinal studies which evaluate the co-occurrence and association of post-ICU impairments, predictors or return to work and their effects are needed. Also needed are trials of interventions to facilitate return to work, for example, specialist-led vocational[69] or combined cognitive and vocational rehabilitation interventions[70] such as those used in survivors of traumatic brain injury.

From an economic standpoint, we identified six studies reporting that previously employed survivors often received new disability benefits after critical illness, with rates of 20–27% at 12 months to 59–89% at 76 months.[4, 5, 14, 30, 42, 62] Jobless survivors in the U.S. also were likely to transition from private to government-provided healthcare coverage,[4, 5] and despite return to work, the majority of non-retired survivors incurred substantial lost earnings that increased over time, totaling up to two-thirds of pre-ICU annual income.[4, 5, 62] While these data do not include other financial consequences, such as medical expenses and caregiver costs, they highlight the substantial economic implications that require further investigation.

Finally, four included studies evaluated outcomes as part of novel multi-disciplinary outpatient ICU recovery programs aimed at evaluating and improving impairments common in survivors of critical illness.[21, 50, 58, 60] Unsurprisingly, at the time of enrollment in these programs (approximately 1 to 5 months after discharge), survivors commonly exhibited disabling cognitive (up to 64%)[60], physical (83%)[50] and mental health (69%)[60] impairments in addition to low return to work rates (15–33%). Of these four studies, one included an intense 5-week peer-supported physical and psychological rehabilitation program, resulting in ICU survivors exhibiting significant improvements in self-efficacy and quality of life metrics at 12-month follow-up, with a return to work rate of 88%.[58] Adding to this literature, a qualitative review of return to work after injury highlighted workplace-related issues, such as cumbersome administrative processes and a lack of goodwill and trust as perceived barriers to return to work.[71] Coordination with employers, in addition to patient-focused rehabilitation, will be vital to post-ICU programs aimed at helping survivors return to work.

Strengths of this systematic review include a comprehensive screening strategy that included 41,977 citations and 2,754 full texts to help maximize identifying eligible studies. Moreover, we performed meta-regression, along with subgroup and sensitivity analyses, and evaluation of secondary outcomes and factors associated with return to work. Despite these strengths, our review had limitations. First, there was substantial between-study heterogeneity in the meta-analysis that was not eliminated with sensitivity and subgroup analyses. The observational nature of the studies, variable follow-up times, and temporal trends may have contributed to this. Population and individual factors may have also contributed, including ICU types, admission diagnoses, pre-existing comorbidities, age, gender, region, and pre-ICU occupation. Moreover, the use of non-standardized employment questionnaires, with varying definitions of employment and modes of data collection also contribute to heterogeneity. A standardized, detailed data collection research tool for return to work assessment does exist,[4, 5, 72, 73] which can be used without cost for non-commercial use (see www.improveLTO.com). To address this heterogeneity, we performed a random-effects meta-regression to derive more conservative pooled estimates, and excluded studies with non-discrete follow-up time points. Second, due to their cross-sectional, bi-directional nature, the risk factors presented must be interpreted with caution. Future studies should assist with understanding the temporal nature of these associations. Finally, potentially eligible studies may have been omitted despite a highly sensitive search strategy.

CONCLUSION

This systematic review and meta-analysis demonstrated that delayed return to work is common after critical illness, affecting two-thirds, two-fifths, and one-third of previously employed survivors up to 3, 12, and 60 months following hospitalization. Notably, this meta-analysis was limited by substantial between-study heterogeneity. For survivors who return to work after critical illness, the experience is often accompanied by subsequent job loss, change in occupation and worsening employment status. Potential risk factors for delayed return to work include pre-existing comorbidities along with mental health impairments after critical illness. Future efforts should focus on designing, evaluating, and optimizing multi-disciplinary vocational interventions aimed at helping survivors return to work.

Supplementary Material

KEY MESSAGES.

What is the key question?

Among previously employed survivors of critical illness, what proportion return to work following intensive care unit (ICU) hospitalization?

What is the bottom line?

One to 3, 6, 12, 18 to 36, and 42 to 60 months following intensive care hospitalization, previously-employed survivors had a pooled return to work prevalence (95% confidence interval) of 36% (23–49%), 64% (52–75%), 60% (50–69%), 63% (44–82%), and 68% (51–85%).

Why read on?

No substantial differences in return to work were observed when stratified by diagnosis (ARDS versus non-ARDS) or region (Europe versus North America versus Australia/New Zealand); however, there were significant differences when comparing mode of employment evaluation (in-person versus telephone versus mail). Additionally, survivors who returned to work commonly experienced adverse work-related outcomes, including changes in occupation, worsening employment status (e.g., fewer work hours), and subsequent job loss.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We thank Usman Sagheer for his assistance.

FUNDING

BK is supported by a Paul B. Beeson Career Development Award through the National Institutes of Health/National Institute on Aging (K76AG059936). DN is supported by funding from the National Institutes of Health/National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (R24HL111985). There were no sources of funding for the writing of this manuscript, including by a pharmaceutical company or other agency. BK had full access to the data and final responsibility for the decision to submit this study for publication.

Footnotes

COMPETING INTERESTS: None declared.

References

- 1.Elliott D, Davidson JE, Harvey MA, Bemis-Dougherty A, Hopkins RO, Iwashyna TJ, et al. Exploring the scope of post-intensive care syndrome therapy and care: engagement of non-critical care providers and survivors in a second stakeholders meeting. CritCare Med 2014;42:2518–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Needham DM, Davidson J, Cohen H, Hopkins RO, Weinert C, Wunsch H, et al. Improving long-term outcomes after discharge from intensive care unit: report from a stakeholders’ conference. CritCare Med 2012;40:502–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Coopersmith CM, Wunsch H, Fink MP, Linde-Zwirble WT, Olsen KM, Sommers MS, et al. A comparison of critical care research funding and the financial burden of critical illness in the United States. CritCare Med 2012;40:1072–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kamdar BB, Huang M, Dinglas VD, Colantuoni E, von Wachter TM, Hopkins RO, et al. Joblessness and Lost Earnings after Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome in a 1-Year National Multicenter Study. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2017;196:1012–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kamdar BB, Sepulveda KA, Chong A, Lord RK, Dinglas VD, Mendez-Tellez PA, et al. Return to work and lost earnings after acute respiratory distress syndrome: a 5-year prospective, longitudinal study of long-term survivors. Thorax 2018;73:125–33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG, Group P. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. J Clin Epi 2009;62:1006–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Turnbull AE, Rabiee A, Davis WE, Nasser MF, Venna VR, Lolitha R, et al. Outcome Measurement in ICU Survivorship Research From 1970 to 2013: A Scoping Review of 425 Publications. Crit Care Med 2016;44:1267–77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cornell JE, Mulrow CD, Localio R, Stack CB, Meibohm AR, Guallar E, et al. Random-effects meta-analysis of inconsistent effects: a time for change. Ann Intern Med 2014;160:267–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Feveile H, Olsen O, Hogh A. A randomized trial of mailed questionnaires versus telephone interviews: response patterns in a survey. BMC medical research methodology 2007;7:27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wells G, Shea B, O’connell D, Peterson J, Welch V, Losos M, et al. The Newcastle-Ottawa Scale (NOS) for assessing the quality of nonrandomised studies in meta-analyses. Ottawa (ON): Ottawa Hospital Research Institute; 2009; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Egger M, Davey Smith G, Schneider M, Minder C. Bias in meta-analysis detected by a simple, graphical test. Bmj 1997;315:629–34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sterne JA, Sutton AJ, Ioannidis JP, Terrin N, Jones DR, Lau J, et al. Recommendations for examining and interpreting funnel plot asymmetry in meta-analyses of randomised controlled trials. Bmj 2011;343:d4002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Parno JR, Teres D, Lemeshow S, Brown RB, Avrunin JS. Two-year outcome of adult intensive care patients. Med Care 1984;22:167–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Goldstein RL, Campion EW, Thibault GE, Mulley AG, Skinner E. Functional outcomes following medical intensive care. Crit Care Med 1986;14:783–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zaren B, Hedstrand U. Quality of life among long-term survivors of intensive care. CritCare Med 1987;15:743–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mundt DJ, Gage RW, Lemeshow S, Pastides H, Teres D, Avrunin JS. Intensive care unit patient follow-up. Mortality, functional status, and return to work at six months. Arch Intern Med 1989;149:68–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ridley SA, Wallace PG. Quality of life after intensive care. Anaesthesia 1990;45:808–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Doepel M, Eriksson J, Halme L, Kumpulainen T, Hockerstedt K. Good long-term results in patients surviving severe acute pancreatitis. The British journal of surgery 1993;80:1583–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.McHugh LG, Milberg JA, Whitcomb ME, Schoene RB, Maunder RJ, Hudson LD. Recovery of function in survivors of the acute respiratory distress syndrome. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 1994;150:90–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bell D, Turpin K. Quality of life at three months following admission to intensive and coronary care units. Clin Intensive Care 1994;5:276–81. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Daffurn K, Bishop GF, Hillman KM, Bauman A. Problems following discharge after intensive care. Intensive Crit Care Nurs 1994;10:244–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Munn J, Willatts SM, Tooley MA. Health and activity after intensive care. Anaesthesia 1995;50:1017–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Fakhry SM, Kercher KW, Rutledge R. Survival, quality of life, and charges in critically III surgical patients requiring prolonged ICU stays. J Trauma 1996;41:999–1007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Weinert CR, Gross CR, Kangas JR, Bury CL, Marinelli WA. Health-related quality of life after acute lung injury. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 1997;156:1120–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hurel D, Loirat P, Saulnier F, Nicolas F, Brivet F. Quality of life 6 months after intensive care: results of a prospective multicenter study using a generic health status scale and a satisfaction scale. Intensive Care Med 1997;23:331–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Eddleston JM, White P, Guthrie E. Survival, morbidity, and quality of life after discharge from intensive care. Crit Care Med 2000;28:2293–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wehler M, Martus P, Geise A, Bost A, Mueller A, Hahn EG, et al. Changes in quality of life after medical intensive care. Intensive Care Med 2001;27:154–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chelluri L, Im KA, Belle SH, Schulz R, Rotondi AJ, Donahoe MP, et al. Long-term mortality and quality of life after prolonged mechanical ventilation. CritCare Med 2004;32:61–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Quality of Life After Mechanized Ventilation in the Elderly Study I. 2-month mortality and functional status of critically ill adult patients receiving prolonged mechanical ventilation. Chest 2002;121:549–58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Haraldsen P, Andersson R. Quality of life, morbidity, and mortality after surgical intensive care: a follow-up study of patients treated for abdominal sepsis in the surgical intensive care unit. Eur J Surg Suppl 2003:23–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wehler M, Geise A, Hadzionerovic D, Aljukic E, Reulbach U, Hahn EG, et al. Health-related quality of life of patients with multiple organ dysfunction: individual changes and comparison with normative population. Crit Care Med 2003;31:1094–101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Garcia Lizana F, Peres Bota D, De Cubber M, Vincent JL. Long-term outcome in ICU patients: what about quality of life? Intensive Care Med 2003;29:1286–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Halonen KI, Pettila V, Leppaniemi AK, Kemppainen EA, Puolakkainen PA, Haapiainen RK. Long-term health-related quality of life in survivors of severe acute pancreatitis. Intensive Care Med 2003;29:782–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Cuthbertson BH, Scott J, Strachan M, Kilonzo M, Vale L. Quality of life before and after intensive care. Anaesthesia 2005;60:332–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Graf J, Wagner J, Graf C, Koch K-C, Janssens U. Five-year survival, quality of life, and individual costs of 303 consecutive medical intensive care patients—A cost-utility analysis. CritCare Med 2005;33:547–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Cinquepalmi L, Boni L, Dionigi G, Rovera F, Diurni M, Benevento A, et al. Long-term results and quality of life of patients undergoing sequential surgical treatment for severe acute pancreatitis complicated by infected pancreatic necrosis. Surg Infect (Larchmt) 2006;7 Suppl 2:S113–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Longo CJ, Heyland DK, Fisher HN, Fowler RA, Martin CM, Day AG. A long-term follow-up study investigating health-related quality of life and resource use in survivors of severe sepsis: comparison of recombinant human activated protein C with standard care. Crit Care 2007;11:R128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ylipalosaari P, Ala-Kokko TI, Laurila J, Ohtonen P, Syrjala H. Intensive care unit acquired infection has no impact on long-term survival or quality of life: a prospective cohort study. Crit Care 2007;11:R35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Linden VB, Lidegran MK, Frisen G, Dahlgren P, Frenckner BP, Larsen F. ECMO in ARDS: a long-term follow-up study regarding pulmonary morphology and function and health-related quality of life. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand 2009;53:489–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.van der Schaaf M, Beelen A, Dongelmans DA, Vroom MB, Nollet F. Functional status after intensive care: a challenge for rehabilitation professionals to improve outcome. J Rehabil Med 2009;41:360–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.van der Schaaf M, Beelen A, Dongelmans DA, Vroom MB, Nollet F. Poor functional recovery after a critical illness: a longitudinal study. J Rehabil Med 2009;41:1041–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Poulsen JB, Moller K, Kehlet H, Perner A. Long-term physical outcome in patients with septic shock. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand 2009;53:724–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kelly MA, McKinley S. Patients’ recovery after critical illness at early follow-up. J Clin Nurs 2010;19:691–700. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Myhren H, Ekeberg O, Stokland O. Health-related quality of life and return to work after critical illness in general intensive care unit patients: a 1-year follow-up study. Crit Care Med 2010;38:1554–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Herridge MS, Tansey CM, Matte A, Tomlinson G, Diaz-Granados N, Cooper A, et al. Functional disability 5 years after acute respiratory distress syndrome. The New England journal of medicine 2011;364:1293–304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Dennis DM, Hebden-Todd TK, Marsh LJ, Cipriano LJ, Parsons RW. How do Australian ICU survivors fare functionally 6 months after admission? Critical care and resuscitation : journal of the Australasian Academy of Critical Care Medicine 2011;13:9–16. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Hodgson CL, Hayes K, Everard T, Nichol A, Davies AR, Bailey MJ, et al. Long-term quality of life in patients with acute respiratory distress syndrome requiring extracorporeal membrane oxygenation for refractory hypoxaemia. Crit Care 2012;16:R202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kowalczyk M, Nestorowicz A, Fijalkowska A, Kwiatosz-Muc M. Emotional sequelae among survivors of critical illness: a long-term retrospective study. Eur J Anaesthesiol 2013;30:111–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Cuthbertson BH, Elders A, Hall S, Taylor J, MacLennan G, Mackirdy F, et al. Mortality and quality of life in the five years after severe sepsis. Crit Care 2013;17:R70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Fonsmark L, Rosendahl-Nielsen M. Experience from multidisciplinary follow-up on critically ill patients treated in an intensive care unit. Dan Med J 2015;62. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Quasim T, Brown J, Kinsella J. Employment, social dependency and return to work after intensive care. J Intensive Care Soc 2015;16:31–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Pratt CM, Hirshberg EL, Jones JP, Kuttler KG, Lanspa MJ, Wilson EL, et al. Long-Term Outcomes After Severe Shock. Shock 2015;43:128–32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Investigators TS, Hodgson C, Bellomo R, Berney S, Bailey M, Buhr H, et al. Early mobilization and recovery in mechanically ventilated patients in the ICU: a bi-national, multi-centre, prospective cohort study. Crit Care 2015;19:81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Reid DB, Chapple LS, O’Connor SN, Bellomo R, Buhr H, Chapman MJ, et al. The effect of augmenting early nutritional energy delivery on quality of life and employment status one year after ICU admission. Anaesthesia and intensive care 2016;44:406–12.27246942 [Google Scholar]

- 55.Norman BC, Jackson JC, Graves JA, Girard TD, Pandharipande PP, Brummel NE, et al. Employment Outcomes After Critical Illness: An Analysis of the Bringing to Light the Risk Factors and Incidence of Neuropsychological Dysfunction in ICU Survivors Cohort. Crit Care Med 2016;44:2003–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Yang N, Li B, Ye B, Ke L, Chen F, Lu G, et al. The long-term quality of life in patients with persistent inflammation-immunosuppression and catabolism syndrome after severe acute pancreatitis: A retrospective cohort study. Journal of critical care 2017;42:101–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Wang ZY, Li T, Wang CT, Xu L, Gao XJ. Assessment of 1-year Outcomes in Survivors of Severe Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome Receiving Extracorporeal Membrane Oxygenation or Mechanical Ventilation: A Prospective Observational Study. Chin Med J (Engl) 2017;130:1161–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.McPeake J, Shaw M, Iwashyna TJ, Daniel M, Devine H, Jarvie L, et al. Intensive Care Syndrome: Promoting Independence and Return to Employment (InS:PIRE). Early evaluation of a complex intervention. PloS one 2017;12:e0188028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Haines KJ, Berney S, Warrillow S, Denehy L. Long-term recovery following critical illness in an Australian cohort. Journal of Intensive Care 2018;6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Sevin CM, Bloom SL, Jackson JC, Wang L, Ely EW, Stollings JL. Comprehensive care of ICU survivors: Development and implementation of an ICU recovery center. Journal of critical care 2018;46:141–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Hodgson CL, Haines KJ, Bailey M, Barrett J, Bellomo R, Bucknall T, et al. Predictors of return to work in survivors of critical illness. Journal of critical care 2018;48:21–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Riddersholm S, Christensen S, Kragholm K, Christiansen CF, Rasmussen BS. Organ support therapy in the intensive care unit and return to work: a nationwide, register-based cohort study. Intensive Care Med 2018;44:418–27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Luyt CE, Combes A, Becquemin MH, Beigelman-Aubry C, Hatem S, Brun AL, et al. Long-term outcomes of pandemic 2009 influenza A(H1N1)-associated severe ARDS. Chest 2012;142:583–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Axelrad H, Sabbath EL, Hawkins SS. The 2008–2009 Great Recession and employment outcomes among older workers. Eur J Ageing 2018;15:35–45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Adhikari NKJ, McAndrews MP, Tansey CM, Matte A, Pinto R, Cheung AM, et al. Self-reported symptoms of depression and memory dysfunction in survivors of ARDS. Chest 2009;135:678–87; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Adhikari NKJ, Tansey CM, McAndrews MP, Matte A, Pinto R, Cheung AM, et al. Self-reported depressive symptoms and memory complaints in survivors five years after ARDS. Chest 2011;140:1484–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.van Velzen JM, van Bennekom CA, Edelaar MJ, Sluiter JK, Frings-Dresen MH. How many people return to work after acquired brain injury?: a systematic review. Brain Inj 2009;23:473–88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Edwards JD, Kapoor A, Linkewich E, Swartz RH. Return to work after young stroke: A systematic review. Int J Stroke 2018;13:243–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Ervasti J, Joensuu M, Pentti J, Oksanen T, Ahola K, Vahtera J, et al. Prognostic factors for return to work after depression-related work disability: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Psychiatr Res 2017;95:28–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Radford K, Sutton C, Sach T, Holmes J, Watkins C, Forshaw D, et al. Early, specialist vocational rehabilitation to facilitate return to work after traumatic brain injury: the FRESH feasibility RCT. Health technology assessment 2018;22:1–124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Howe EI, Langlo KS, Terjesen HCA, Roe C, Schanke AK, Soberg HL, et al. Combined cognitive and vocational interventions after mild to moderate traumatic brain injury: study protocol for a randomized controlled trial. Trials 2017;18:483. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.MacEachen E, Clarke J, Franche RL, Irvin E, Workplace-based Return to Work Literature Review G. Systematic review of the qualitative literature on return to work after injury. Scand J Work Environ Health 2006;32:257–69. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Needham DM, Dinglas VD, Bienvenu OJ, Colantuoni E, Wozniak AW, Rice TW, et al. One year outcomes in patients with acute lung injury randomised to initial trophic or full enteral feeding: prospective follow-up of EDEN randomised trial. Bmj 2013;346:f1532. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Dinglas VD, Hopkins RO, Wozniak AW, Hough CL, Morris PE, Jackson JC, et al. One-year outcomes of rosuvastatin versus placebo in sepsis-associated acute respiratory distress syndrome: prospective follow-up of SAILS randomised trial. Thorax 2016;71:401–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.