Abstract

Background:

Various risk factors are coupled with atherosclerotic complications, such as myocardial infarction and stroke. Periodontitis is considered one of them.

Aims and Objectives:

The objective of the study is to compare and correlate the occurrences of periodontitis with serum levels of cardiac-biomarkers in patients with coronary heart-disorders.

Materials and Methods:

Of 70 individuals diagnosed with coronary artery diseases, 32 patients with chronic periodontitis constituted the test group, 31 without chronic periodontitis constituted the control group. Cardiac-biomarkers analyzed were Troponin T, Troponin I, Myoglobin; low density lipoprotein (LDL), high-density lipoprotein, very LDL (VLDL), total cholesterol (TC), and highly sensitive C-reactive protein (Hs-CRP). Periodontal characteristics were drawn from the plaque index (PI) and gingival index, probing depth (PD), clinical attachment loss, and periodontal inflammatory surface area (PISA).

Statistical Analysis:

In order to separate any association between cardiac biomarkers and clinical parameters of periodontitis, detailed statistical analysis through independent t-test and Pearson test of correlation was done.

Results:

Statistically significant differences were seen not only in PI, PD, and PISA between both the groups (P < 0.05), but also between various cardiac parameters of test and control groups (P < 0.001). Positive relations were seen in the test group, between cardiac biomarkers such as TC, VLDL, Hs-CRP, and Troponin T with periodontal parameters such as PD and PISA.

Conclusion:

The study reveals, a strong association between periodontitis and diseases of cardiovascular nature, highlighting the need for awareness and timely medical interventions to prevent periodontitis from scaling up and interfering with the risk of cardiovascular problems.

Keywords: Cardiac biomarkers, chronic periodontitis, coronary artery disease, lipid profile, troponin and myoglobin

INTRODUCTION

Periodontal medicine, a term first coined by Offenbacher refers to an area that analyzes a host of all-new data. It points to a binding relation between periodontal diseases and systemic health conditions. Being a critically important constituent of overall health, oral health in patients with periodontitis is a potential risk leading to other diseases. Worth noting is that the infections on account of periodontitis are considered chronic with occasional acute bursts. Periodontitis can trigger systemic inflammations by actuating the acute hepatic phase response owing to the possible bacteremia which is temporary but recurrent in nature.[1]

Coronary artery disease, also known as coronary heart disease is the culmination of atheromatous plaques formed within the arterial walls. Severe periodontitis patients are twice at the risk of a fatal heart-attack, and three times prone to a stroke compared to those without periodontitis; and this is true for cases known through cardiovascular risk, such as, lipid profile, cholesterol readings, body mass, conditions associated with diabetes and smoking habits.[2] The fact that periodontal pathogens have been observed in the atherosclerotic plaques of humans establishes that infections caused by periodontitis can develop bacteremia and accelerate accumulation of atherosclerotic plaque.[3]

Biomarkers play a very critical role in drawing conclusions for a diagnosis. Owing to highly sensitive (Hs) nature, preciseness and level of availability, analysis of cardiac troponins is currently considered gold standard for diagnosing myocyte necrosis bio-chemically. Myocardium releases two types of troponins, namely I (cTnl) and T (cTnT) which can be diagnosed within 2–4 h, but an increase which is helpful to diagnosis often does not happen until 4–6 h of the observed event due to gradual nature of discharge from necrotized cardiomyocytes. This also answers why plasma of cTn can remain at elevated levels of duration as lengthy as 14 days in the presence of extensive myocardial necrosis. In the event of injury to myocytes, myoglobin (Myo), another major marker by virtue of it is comparably low-weight in the presence of myocyte injury, skips into and persists in circulatory system for its short (half) life of just 10–30 min. Increase in plasma levels become apparent within an hour of the start of the event. Similar increase is helpful in early diagnosis of acute myocardial infarction (AMI), say between 2 and 12 h of the event. Nevertheless, it should be noted that Myo is not myocardium specific.[4]

The analysis of cross-sectional evidences denotes that periodontitis causes only little elevation in markers of acute phase responses from liver like, C-reactive protein (CRP), haptoglobin, αl-antitrypsin, and fibrinogenin in response to virulence factors like lipopolysacharides of blood borne oral bacteria, which also triggers discharge of cytokines such as interleukin (IL)-6 and tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-α).[5] Hs-CRP is a precursory indicator of atherothrombosis, thus being a strongest marker of inflammation in the event of cardiovascular diseases.[6] Thus, the aim of this study in this background has been to analyze the instance of chronic periodontitis in patients having cardiac biomarkers in serum levels of patients pointing to coronary heart problems. Also to deduce a probable association between both chronic periodontitis and coronary heart disorder by correlating both cardiac biomarkers and periodontal clinical as well as inflammatory parameters.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study population and design

This analytical cross-sectional study attempts to check the differences in various cardiac parameters between cardiac patients with periodontitis and without periodontitis. Seventy patients diagnosed with coronary artery disease(s) marked by cardiac necrosis, coronary angiography, and characteristic changes in electrocardiogram (ECG) and clinically established symptoms were short-listed for double-blinded cross-sectional analysis. From this, those who did not match the eligibility criteria were seven in number and were excluded. Thus, the final number of patients was 63. After a round of interview to assess their suitability for including in the study, these volunteers were subjected to periodontal tests, conducted while patients were in-hospital, or shortly after they were discharged.

Patients diagnosed with chronic periodontitis who had bleeding while probing; patients with clinical attachment loss (CAL) ≥1 having minimum 20 natural teeth with at least two probing pockets having a depth more than 3 mm;[7] those who had not had any medical care for periodontitis in the previous 6 months, and those who had not used any systemic antibiotics in the preceding 6 weeks of the study, constituted the test group (N = 32). Thus, the test group comprised of patients having coronary artery disease with chronic periodontitis; and subjects without chronic periodontitis formed the control group (N = 31). Participants found to have any other systemic health concerns, conditions of compromised immune system, auto-immune disorder, having prolonged antimicrobial therapy, recent treatment with corticosteroids (since corticosteroids may mask the immune response of the host being an immunosuppressant) or nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), (as NSAIDs may façade inflammatory reaction of the host, leading to misinterpretation of the inflammatory markers/parameters), or presently receiving any treatment for periodontitis were excluded.

Ethical parameters for clinical researches, mentioned in the Declaration of Helsinki 2008 were adhered to during the study. Protocol was approved of by the Scientific and Ethical Committee of the institution from December 2017 to June 2018. After being thoroughly educated about the study protocol, the volunteers’ willingness was obtained in writing, duly signed.

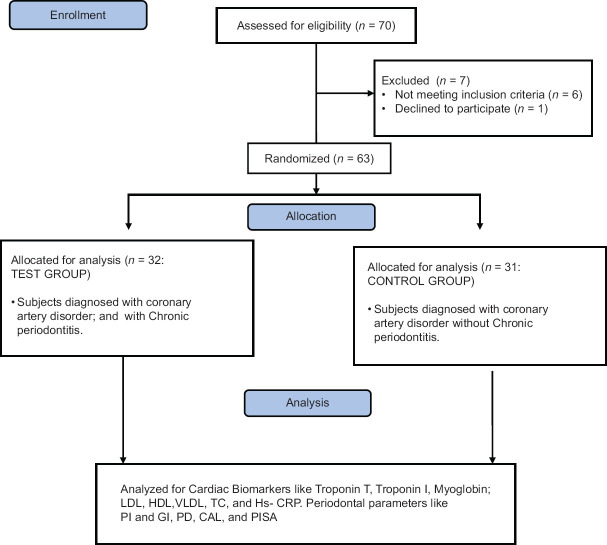

A periodontal specialist (B. R) singly performed the examination, remaining blinded to clinical, cardiac, and hematological information of patients. In order to gauge the probing pocket depth and loss of clinical attachment at six sites per tooth, excluding the third molars, a properly calibrated UNC-15 probe, (Hu-Friedy, Chicago, IL, USA) was put in use. Using parameter of periodontal inflammatory surface area (PISA), periodontal disease characterized by inflammation was assessed, which was the sum of periodontal probing depth (PD) of bleeding on probing-affected areas, for the complete dentition.[8] PISA also referred to the extent of inflammation that could be quantitatively assessed to separate subjects with active inflammation from those having noninflammed or healed tissues. Also considered were the plaque index (PI) (O’Leary et al., 1972) and gingival index (GI) (Loe and Silness, 1963). The consort flow chart for the study population and design is given in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Consort flow chart. n – number; LDL – low-density lipoproteins; HDL – high-density lipoproteins; VLDL – Very low-density lipoproteins; TC – Total count; HS-CRP–High- sensitivity C-reactive protein; PI – Plaque index; GI – Gingival index; PD – Probing depth; CAL – Clinical attachment loss; PISA – Periodontal inflammatory surface area

Cardiology study and hematologic measurements

In order to diagnose the presence of coronary artery diseases, ECG and coronary angiography were resorted to. The cardiac biomarkers were assessed by withdrawing patient's blood on his/her arrival at the emergency section, and at 6, 8, 12, and 18 h, together with bio-medical criteria of lipid profile. Besides low-density lipoprotein (LDL), high density lipoprotein (HDL), very LDL (VLDL) and total cholesterol (TC), inflammatory marker, Hs CRP, were recorded and assessed through the blood. The blood drawn was collected; it was transferred into ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid – containing tubes to assess cardiac biomarkers such as peak cTn, TcI, and Myo readings by chemiluminiscence immunoassay from Beckman Coulter Inc. (Brea, CA, USA). This brings out the sensitivity and specificity percentages of 96 and 94 respectively for a cutoff point of 0.50 ng/mL, where Myo escalation is pointed to, by an increase of >70% ng/mL at any point of the time measurement. Blood serum was separated by centrifuging at 13,000 rotations per minute before performing the chemiluminiscence assay. Samples along with control serum were diluted to the ratio of 1:50. After 100 μl of standardized solution and serum were transferred to the wells, 50 μl of immune-reagent was added, followed by incubating and shaking at 300 rpm for an hour. 3,3’,5,5’-Tetramethylbenzidine (TMB) substrate 100 μl was added, followed by incubating on a shaker at 300 rpm for 25 min at room-temperature. After the buffer was aspirated away; 25 μl of TMB stopper solution was added specifically to each well on finding sufficient color, which was again incubated for 1 min.[9]

Statistical analysis

For analysis of data, SPSS version 23 (IBM Inc. Chicago, Illinois, USA) was used. To ascertain associations between cardiac biomarker indicators and periodontal clinical parameters, independent t-test and Pearson correlation tests were done. Kappa statistics assessed inter and intra testing reliability, which was found 0.77 and 0.81, respectively, showing a high degree of conformity in the findings.

RESULTS

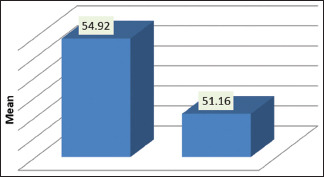

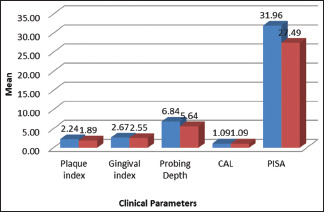

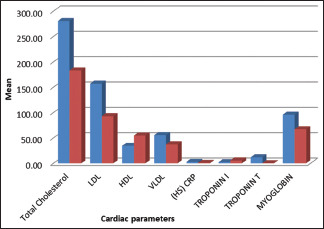

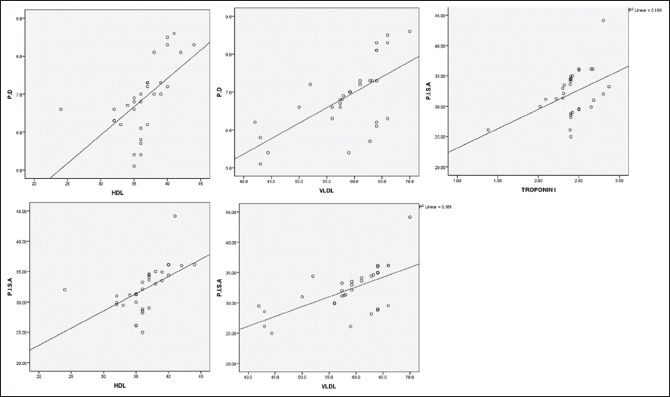

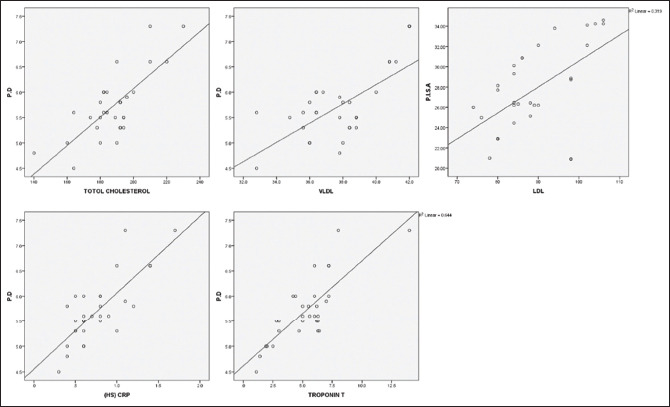

Table 1 and Graph 1 represents the Intergroup comparison of mean age in years. While the mean age was 54.92 years for the test group, in control group, it stood at 51.16 years. There were no statistically significant differences between the two groups in age (P = 0.113). This finding ensures matching between the two groups, as age could be a possible confounding factor in this association. The fact that individuals with other systemic diseases and those who have been under treatment for periodontal disease were excluded in this study also adds value in the quest of eliminating intrusion of bias. As for comparison of PI, PD, and PISA between the two groups (P < 0.05), as shown in Table 2 and Graph 2, the variations were significant, where mean PI of 2.24 ± 0.59, 1.89 ± 0.40; mean PD value of 6.83 ± 0.99, 5.63 ± 0.60; and mean PISA of 31.9 ± 3.7, 27.48 ± 4.22 were statistically analyzed in the respective order of test groups and control groups. While not much difference was noticed between GI and CAL in the groups, significant variations were noted between different cardiac parameters among test and control groups (P < 0.001), as shown in Table 3 and Graph 3. Comparison between cardiac biomarkers and periodontal parameters in test group was captured in Table 4 and Graph 4, and that of control group in Table 4 and Graph 5, indicated statistically positive and measurable similarities among TC, VLDL, Hs-CRP and Troponin T with PD and PISA in patients having congestive cardiac disorder and chronic periodontitis.

Table 1.

Intergroup comparison of mean age in years

| Group | n | Minimum | Maximum | Mean±SD | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Test | 32 | 39 | 65 | 54.92±6.825 | 0.113 (NS) |

| Control | 31 | 30 | 65 | 51.16±9.450 |

NS – Notsignificant (P>0.05); n – Sample size; SD – Standard deviation; P – Probablility value

Graph 1.

Intergroup comparison of mean age

Table 2.

Intergroup comparison of periodontal clinical parameters

| Parameter | Mean±SD | Mean difference | P | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Test group | Control group | |||

| Plaque index | 2.2408±0.59228 | 1.8948±0.40816 | 0.34600 | 0.020* |

| Gingival index | 2.6680±0.40360 | 2.5500±0.17678 | 0.11800 | 0.187 (NS) |

| Probing depth | 6.836±0.9995 | 5.636±0.6048 | 1.2000 | <0.001** |

| CAL | 1.092±0.6582 | 1.092±0.6582 | 0.0000 | 1 (NS) |

| PISA | 31.9568±3.74697 | 27.4852±4.22111 | 4.47160 | <0.001** |

*Significant (P<0.05); **Highly significant (P<0.001). NS – Not significant (P>0.05); CAL – Clinical attachment loss; PISA – Periodontal inflammatory surface area; SD – Standard deviation; P – Probablility value

Graph 2.

Intergroup comparison of periodontal clinical parameters

Table 3.

Intergroup comparison of cardiac parameters

| Parameter | Mean±SD | Mean difference | P | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Test group | Control group | |||

| Total cholesterol | 280.32±47.20 | 182.84±23.55 | 97.480 | <0.001** |

| LDL | 157.04±19.73 | 92.76±9.81 | 64.280 | <0.001** |

| HDL | 34.44±4.33 | 54.72±8.19 | −20.280 | <0.001** |

| VLDL | 55.67±9.18 | 37.37±2.27 | 18.30 | <0.001** |

| HS CRP | 2.77±0.74 | 0.87±0.71 | 1.90 | <0.001** |

| Troponin I | 2.22±0.27 | 5.58±1.11 | −3.36 | <0.001** |

| Troponin T | 11.72±2.12 | 0.26±0.14 | 11.46 | <0.001** |

| Myoglobin | 95.69±14.66 | 67.00±12.72 | 28.69 | <0.001** |

**Highly significant (P<0.001). There is statistically significant difference present between various cardiac parameters between test group and control group (P<0.001). LDL – Low-density lipoprotein; HDL – High-density lipoprotein; VLDL – Very LDL; HS CRP – Highly sensitive C-reactive protein; SD – Standard deviation; P – Probablility value

Graph 3.

Intergroup comparison of cardiac parameters

Table 4.

Correlation between clinical and cardiac parameters

| Group | Parameter | Statistics | Total cholesterol | LDL | HDL | VLDL | HS CRP | Troponin I | Troponin T | Myoglobin |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control | PI | Pearson correlation | 0.068 | 0.246 | −0.193 | 0.058 | 0.183 | 0.267 | 0.123 | 0.389 |

| P | 0.746 | 0.236 | 0.355 | 0.781 | 0.381 | 0.197 | 0.557 | 0.055 | ||

| n | 25 | 25 | 25 | 25 | 25 | 25 | 25 | 25 | ||

| GI | Pearson correlation | 0.177 | 0.183 | −0.068 | 0.155 | 0.026 | −0.169 | 0.215 | −0.038 | |

| Significant (two-tailed) | 0.399 | 0.382 | 0.747 | 0.459 | 0.902 | 0.418 | 0.303 | 0.858 | ||

| n | 25 | 25 | 25 | 25 | 25 | 25 | 25 | 25 | ||

| PD | Pearson correlation | 0.752** | 0.279 | −0.318 | 0.699** | 0.793** | 0.246 | 0.825** | 0.148 | |

| Significant (two-tailed) | <0.001 | 0.177 | 0.122 | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.236 | <0.001 | 0.480 | ||

| n | 25 | 25 | 25 | 25 | 25 | 25 | 25 | 25 | ||

| CAL | Pearson correlation | −0.291 | 0.152 | −0.045 | −0.308 | −0.008 | −0.167 | −0.273 | 0.094 | |

| Significant (two-tailed) | 0.158 | 0.468 | 0.829 | 0.134 | 0.968 | 0.425 | 0.187 | 0.656 | ||

| n | 25 | 25 | 25 | 25 | 25 | 25 | 25 | 25 | ||

| PISA | Pearson correlation | 0.390 | 0.563** | −0.317 | 0.361 | 0.362 | 0.212 | 0.389 | 0.360 | |

| Significant (two-tailed) | 0.054 | 0.003 | 0.122 | 0.076 | 0.075 | 0.308 | 0.054 | 0.077 | ||

| n | 25 | 25 | 25 | 25 | 25 | 25 | 25 | 25 | ||

| Test | PI | Pearson correlation | 0.070 | 0.067 | −0.087 | 0.155 | −0.621** | 0.173 | 0.133 | −0.263 |

| Significant (two-tailed) | 0.738 | 0.750 | 0.680 | 0.461 | 0.001 | 0.408 | 0.527 | 0.204 | ||

| n | 25 | 25 | 25 | 25 | 25 | 25 | 25 | 25 | ||

| GI | Pearson correlation | 0.040 | 0.061 | 0.197 | −0.022 | −0.163 | −0.335 | 0.166 | 0.063 | |

| Significant (two-tailed) | 0.851 | 0.771 | 0.345 | 0.916 | 0.435 | 0.101 | 0.427 | 0.767 | ||

| n | 25 | 25 | 25 | 25 | 25 | 25 | 25 | 25 | ||

| PD | Pearson correlation | 0.210 | 0.365 | −0.591** | 0.647** | 0.045 | 0.290 | 0.217 | −0.068 | |

| Significant (two-tailed) | 0.313 | 0.073 | 0.002 | <0.001 | 0.830 | 0.160 | 0.297 | 0.746 | ||

| n | 25 | 25 | 25 | 25 | 25 | 25 | 25 | 25 | ||

| CAL | Pearson correlation | 0.119 | 0.343 | −0.212 | 0.381 | −0.022 | 0.265 | 0.047 | −0.216 | |

| Significant (two-tailed) | 0.571 | 0.093 | 0.308 | 0.061 | 0.917 | 0.201 | 0.824 | 0.300 | ||

| n | 25 | 25 | 25 | 25 | 25 | 25 | 25 | 25 | ||

| PISA | Pearson correlation | −0.085 | 0.236 | −0.550** | 0.423* | −0.021 | 0.417* | 0.311 | −0.309 | |

| Significant (two-tailed) | 0.685 | 0.256 | 0.004 | 0.035 | 0.919 | 0.038 | 0.130 | 0.133 | ||

| n | 25 | 25 | 25 | 25 | 25 | 25 | 25 | 25 |

**Correlation is significant at the P<0.01 level (two-tailed); *Correlation is significant at the P<0.05 level (two-tailed). LDL – Low-density lipoprotein; HDL – High density lipoprotein; VLDL – Very LDL; HS CRP – Highly sensitive C-reactive protein; PI – Plaque index; GI – Gingival index; PD – Probing depth; CAL – Clinical attachment loss; PISA – Periodontal inflammatory surface area; n – Total number; P – Probablility value

Graph 4.

Correlation between periodontal and cardiac parameters in the test group. PD – Probing depth; PISA – Periodontal inflammatory surface area; HDL – High-density lipoproteins; VLD L– Very low-density lipoproteins

Graph 5.

Correlation between periodontal and cardiac parameters in the control group. PD – Probing depth; PISA -– Periodontal inflammatory surface areal; HS-CRP – Highsensitivity C-reactive protein; VLDL – Very low-density lipoproteins; LDL – low-density lipoproteins

DISCUSSION

When systemically challenged with gram-negative bacteria or virulence factors such as lipopolysaccharide (LPS) or endotoxins, blood vessels show inflammatory cell infiltration that subsequently leads to vascular smooth muscle proliferation and fatty degeneration with intra-vascular coagulation.[10]

The current study has shown statistically significant differences not only in periodontal parameters such as PI, PD, and PISA between both the groups (P < 0.05), but also between various cardiac parameters of test and control groups (P < 0.001). This correlation was seen indicative of the inflammatory background in both coronary artery diseases as well in chronic periodontitis. However, logistic regression analysis by Mattilla et al., who analyzed that the factors influencing dental health and coronary heart disease were not dependent on age, TC, HDL, triglycerides (TGs), C peptide, diabetes, hypertension, and even smoking.[11]

In the current study, positive relations were seen in the test group, between cardiac biomarkers like TC, VLDL, Hs-CRP, and Troponin T with periodontal parameters such as PD and PISA. These findings were in accordance with the studies by DeStefano F, et al. who showed a relation between periodontal diseases and coronary heart disease citing linkage between periodontitis, AMI and/or atherosclerosis.[12] The elevated levels of inflammatory parameters in patients with coronary artery disease with chronic periodontitis could be attributed to the systemically hyper inflammatory monocyte phenotype that discharges inordinately higher levels of inflammatory cytokines indicating high risk of atherosclerosis and emboli formation due to underlying M0 + phenotype.[13]

Atherosclerosis that leads to cardiovascular diseases is marked by dyslipidemia, bio-marked by abnormal levels of TG, cholesterol or lipoproteins in plasma, although other confounding factors like chronic inflammation also contribute to its pathogenesis. This probably explains the reason for the statistically significant elevated levels of lipid parameters like VLDL in test group, having positive correlation with periodontal parameters.[14] LDL accelerates the onset of atheroma caused by accelerating monocytic discharge of IL-1 β, TxA2, and TNF-α and exaggerates response to LPS.[15] The demonstration of lipid deposition in descending aorta of a rat where in periodontitis was induced by ligatures, pointed that diet high in cholesterol could exacerbate periodontitis in those animals.[16]

Periodontal epithelium and connective tissues can be attacked by anaerobic bacteria such as Porphyromonas gingivalis, Prevotella intermedia, Tannerella forsythia, and Aggregatibacter actinomycetemcomitans. These were shown to be viably persistent in the coronary endothelium and atherosclerotic plaque as well.[17] P. gingivalis in vitro, in the presence of LDL-induced macrophages to change into foam cells and the measure of tissues damaged by periodontitis is directly linked to the proportion of macrophages activated by LDL.[18]

A study establishing role of P. gingivalis in aggression, degradation, inactivation of proteins and dysfunctions at cellular levels, by modification of oxidative phosphatidylcholines in vascular LDL, arrived at the conclusion that P. gingivalis can change both protein expression and LDL's potential to proliferate, besides playing a critical role in periodontitis-related atherosclerosis.[19]

According to recent literature, CRP and its peptides influence processes such as shedding of cellular adhesion molecules, which has intrigued the researchers regarding its role in influencing adhesion and trans-migration of leukocytes around the endothelial wall. What is hypothesized here is that an inflammation, even low grade, identified by CRP contributes to an evidence of chronic infection.[20]

Cardiac troponins T and I, the myofibrillar proteins, have been recognized as specific and sensitive myocyte injury markers, thereby fortifying stratification and substantially helping the diagnosis, in patient care of coronary syndromes.[21] The relation of periodontitis with serum LPS/endotoxin, and raised levels of troponin have been observed in the studies conducted by Goteiner et al.[22]

Taking into consideration elevated ST in ECG and typical AMI aspects, it was seen that the total count of leukocytes correlated the linkage between chronic periodontitis and cTnI; and also between cerebral palsy and Myo.[23] Similarly, the extremity level of periodontitis has a direct impact on the size of AMI, as counted by serum troponin I and Myo levels.[24] Likewise, other markers showing cardiac lesions in chronic patients with inflammation are troponin T, troponin I, pro-BNP, LDH, and high sensitivity CRPs.[25] Myo is considered a less effective marker with respect to specificity compared to troponin in investigating myocardial necrosis even though both are used in the present analytical study due to their better prediction capabilities in people with coronary artery disorder, and their relation with final peak of troponin.[26]

The limitations of this study are its small sample size which raises questions on the power to detect significant differences between the groups. Nevertheless, this is one of the first attempts to correlate between cardiac parameters and periodontal health of subjects in the study area and offers important insights for future health promotional initiatives. Although statistically significant, the variability of analyzed markers has been low; hence, there is a need to interpret the results with care and in terms of their clinical cardiac relevance. In addition, in order to interpret these findings, more studies on gingival crevicular fluid-markers associated with chronic periodontitis will be warranted in future.

CONCLUSION

This study significantly contributes to further data for research highlighting the jurisdiction and severity of periodontitis and its linkage to coronary artery diseases, by way of cardiac bio-markers, such as cardiac troponin I, cardiac troponin T, Myo, lipid profile, and chronic periodontitis.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Williams RC, Offenbacher S. Periodontal medicine: The emergence of a new branch of periodontology. Periodontol 2000. 2000;23:9–12. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0757.2000.2230101.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Beck JD, Offenbacher S, Williams R, Gibbs P, Garcia R. Periodontitis: A risk factor for coronary heart disease? Ann Periodontol. 1998;3:127–41. doi: 10.1902/annals.1998.3.1.127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Haraszthy VI, Zambon JJ, Trevisan M, Zeid M, Genco RJ. Identification of periodontal pathogens in atheromatous plaques. J Periodontol. 2000;71:1554–60. doi: 10.1902/jop.2000.71.10.1554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Janota T. Biochemical markers in the diagnosis of myocardial infarction. Coret Vasa. 2014;56:e304–10. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chiu B. Multiple infections in carotid atherosclerotic plaques. Am Heart J. 1999;138:S534–6. doi: 10.1016/s0002-8703(99)70294-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ridker PM. Intrinsic fibrinolytic capacity and systemic inflammation: Novel risk factors for arterial thrombotic disease. Haemostasis. 1997;27(Suppl 1):2–11. doi: 10.1159/000217475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Armitage GC. Periodontal diagnoses and classification of periodontal diseases. Periodontol 2000. 2004;34:9–21. doi: 10.1046/j.0906-6713.2002.003421.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nesse W, Abbas F, Van Der Ploeg I, Spijkervet FK, Dijkstra PU, Vissink A. Periodontal inflamed surface area: Quantifying inflammatory burden. J Clin Periodontol. 2008;35:668–73. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-051X.2008.01249.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Loo WY, Yue Y, Fan CB, Bai LJ, Dou YD, Wang M, et al. Comparing serum levels of cardiac biomarkers in cancer patients receiving chemotherapy and subjects with chronic periodontitis. J Transl Med. 2012;10(Suppl 1):S5. doi: 10.1186/1479-5876-10-S1-S5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kweider M, Lowe GD, Murray GD, Kinane DF, McGowan DA. Dental disease, fibrinogen and white cell count; links with myocardial infarction? Scott Med J. 1993;38:73–4. doi: 10.1177/003693309303800304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mattila KJ, Nieminen MS, Valtonen VV, Rasi VP, Kesäniemi YA, Syrjälä SL, et al. Association between dental health and acute myocardial infarction. BMJ. 1989;298:779–81. doi: 10.1136/bmj.298.6676.779. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.DeStefano F, Anda RF, Kahn HS, Williamson DF, Russell CM. Dental disease and risk of coronary heart disease and mortality. BMJ. 1993;306:688–91. doi: 10.1136/bmj.306.6879.688. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Beck J, Garcia R, Heiss G, Vokonas PS, Offenbacher S. Periodontal disease and cardiovascular disease. J Periodontol. 1996;67:1123–37. doi: 10.1902/jop.1996.67.10s.1123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Austin MA, Hokanson JE, Edwards KL. Hypertriglyceridemia as a cardiovascular risk factor. Am J Cardiol. 1998;81:7B–12B. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9149(98)00031-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Salbach PB, Specht E, Von Hodenberg E, Kossmann J, Janssen-Timmen U, Schneider WJ, et al. Differential low density lipoprotein receptor-dependent formation of eicosanoids in human blood-derived monocytes. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1992;89:2439–43. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.6.2439. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ekuni D, Tomofuji T, Sanbe T, Irie K, Azuma T, Maruyama T, et al. Periodontitis-induced lipid peroxidation in rat descending aorta is involved in the initiation of atherosclerosis. J Periodontal Res. 2009;44:434–42. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0765.2008.01122.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kozarov EV, Dorn BR, Shelburne CE, Dunn WA, Jr, Progulske-Fox A. Human atherosclerotic plaque contains viable invasive Actinobacillus actinomycetemcomitans and Porphyromonas gingivalis. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2005;25:e17–8. doi: 10.1161/01.ATV.0000155018.67835.1a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pussinen PJ, Vilkuna-Rautiainen T, Alfthan G, Palosuo T, Jauhiainen M, Sundvall J, et al. Severe periodontitis enhances macrophage activation via increased serum lipopolysaccharide. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2004;24:2174–80. doi: 10.1161/01.ATV.0000145979.82184.9f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bengtsson T, Karlsson H, Gunnarsson P, Skoglund C, Elison C, Leanderson P, et al. The periodontal pathogen Porphyromonas gingivalis cleaves apoB-100 and increases the expression of apoM in LDL in whole blood leading to cell proliferation. J Intern Med. 2008;263:558–71. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2796.2007.01917.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zouki C, Beauchamp M, Baron C, Filep JG. Prevention of In vitro neutrophil adhesion to endothelial cells through shedding of L-selectin by C-reactive protein and peptides derived from C-reactive protein. J Clin Invest. 1997;100:522–9. doi: 10.1172/JCI119561. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Thomas RA, Krishnakumari S. Cardiac biomarkers: Past, present and future. Int J Cur Res Rev. 2015;7:1. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Goteiner D, Craig RG, Ashmen R, Janal MN, Eskin B, Lehrman N. Endotoxin levels are associated with high-density lipoprotein, triglycerides, and troponin in patients with acute coronary syndrome and angina: Possible contributions from periodontal sources. J Periodontol. 2008;79:2331–9. doi: 10.1902/jop.2008.080068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.MacKinnon DP, Fairchild AJ, Fritz MS. Mediation analysis. Annu Rev Psychol. 2007;58:593–614. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.58.110405.085542. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Marfil-Álvarez R, Mesa F, Arrebola-Moreno A, Ramírez-Hernández JA, Magán-Fernández A, O’Valle F, et al. Acute myocardial infarct size is related to periodontitis extent and severity. J Dent Res. 2014;93:993–8. doi: 10.1177/0022034514548223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Loos BG, Craandijk J, Hoek FJ, Wertheim-Van Dillen PM, Van Der Velden U. Elevation of systemic markers related to cardiovascular diseases in the peripheral blood of periodontitis patients. J Periodontol. 2000;71:1528–34. doi: 10.1902/jop.2000.71.10.1528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sanchis J, Bodí V, Llácer Á, Facila L. Usefulness of concomitant myoglobin and troponin elevation as a biochemical marker of mortality in non-ST-segment elevation acute coronary syndrome. Am J Cardiol. 2003;91:448–51. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9149(02)03244-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]