Summary box.

In the context of the pandemic spread of COVID-19, the majority of high-income countries have witnessed an extraordinary high death toll of people living in residential care facilities.

Social epidemiology makes an important contribution to better understand this phenomenon, attributable to the biological impact of the pathogen on vulnerable high-risk populations and to the place of care as a decisive social determinant of health.

The tragedy of COVID-19 related deaths in nursing homes is primarily due to its iatrogenic spread and aggravated by socioeconomic circumstances.

Current isolation and confinement policies, including the prolonged separation of residents from their loved ones have failed to show their effectiveness in preventing these developments and are therefore disproportionate. They have to be replaced by policies that respect both the needs of safety of all residents and basic human rights.

In addition to the questionable effectiveness, these policies bear considerable opportunity costs, as they negatively affect quality of life and health outcomes of isolated residents.

Seen through the lens of medicine as a social science and of social epidemiology in particular, the COVID-19 crisis provides opportunities to better understand and fundamentally improve framework conditions within residential care facilities as well as other ‘large households’ all over the globe and to build safer institutions for all people in need of continuous care.

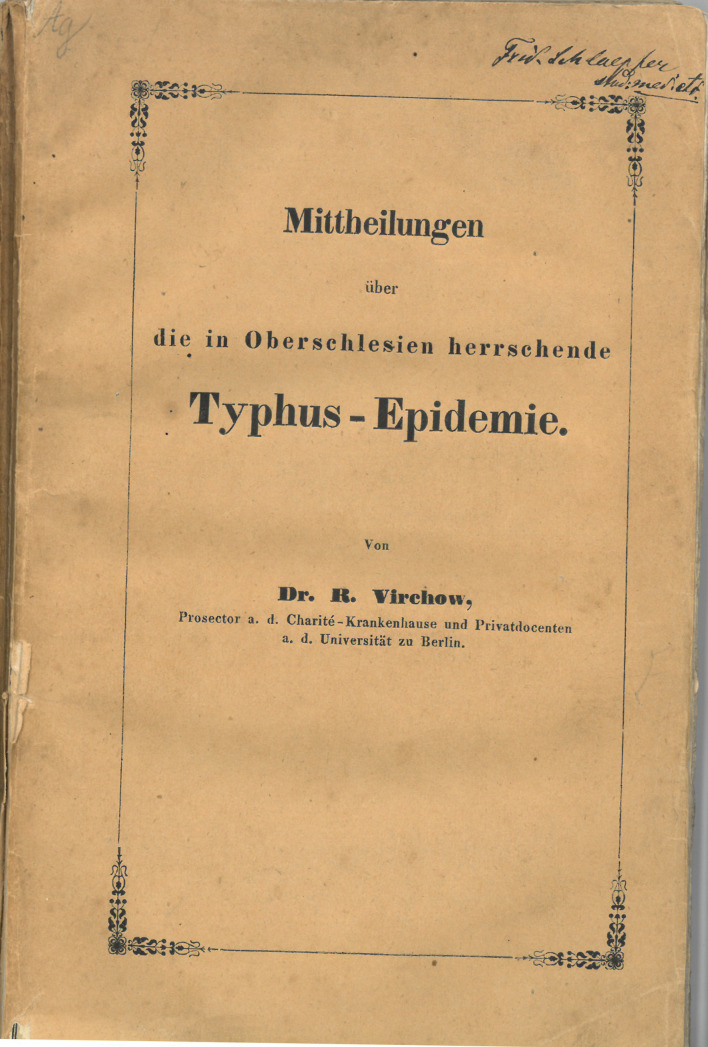

When Rudolf Virchow was sent to the region of Upper Silesia in 1848 to investigate the outbreak of typhus, he went as a young scientist, who was later considered as one of the founders of pathology and infectiology.1 He came back as one of the founders of social hygiene and epidemiology and, after his friend Neumann, coined the sentence ‘medicine is a social science and politics is nothing else but medicine at a larger scale’2 (figure 1).

Figure 1.

Title page of the first print of Rudolf Virchow’s book.1 Source: Courtesy of the University of Zurich Central Library.

How did Virchow come to that statement? He witnessed the situation of the poor, badly nourished population, living closely together in large non-hygienic households. He was convinced that the catastrophic outbreak of this infectious disease could not be blamed on foreigners, the Jewish population or was caused by an obscure bad odour, the miasma (even though he used the term). Virchow was sure that a germ was the pathogenic agens, not having been discovered at this time. Yet, the main factor he presumed to trigger the typhus outbreak was the social situation. This, however, did not prevent him from ignoring the discovery of Ignaz Semmelweis, come to be known as ‘savior of mothers’, that the puerperal sepsis agent is not an infectious substance within the body or due to uterine thrombosis in women but an iatrogenic infection, caused by physicians, carrying the germs on their hands and transmitting them from one para to another.3

In December 2019, an outbreak of a novel corona virus was first identified in Wuhan, China. The WHO announced a public health emergency on 30 January and a world pandemic on 11 March, when the disease affected Iran, Europe from south and west to north and east, and, slightly later, caused outbreaks in the USA, Russia, Australia and New Zealand, soon affecting also countries in the middle and south American as well as in the African continent.

At a global level—as excellently elaborated by Prasad et al—4 COVID-19 both unveiled and exacerbated existing inequalities and injustices within a country, making different populations particularly vulnerable to COVID-19 and its sequelae, among them people living in poverty, without shelter, without regular residence, without employment or people living in residential care facilities.5 In many high-income countries, the reaction of politics, scientists and clinicians, although differing in detail, followed a common pattern: it started with counting the first cases, trying to trace back the ‘patient (or population) zero’, focusing on acute hospitals, especially intensive care units (ICUs), closing boarders, locking down more or less strictly and rapidly the whole population and totally isolating people living in nursing homes and increasingly in all larger institutions from their loved ones.6 7 The main reasons given for the strict isolation was to increase ‘reserve capacities’ in hospitals and to protect the lives of the residents of residential care facilities. They were soon identified as being the most vulnerable in these countries with high risk for COVID-19 infection and severe outcomes due to frailty and chronic comorbidities,8 exposed to circumstances with staff shortage, insufficient access to personal protective equipment and limited staff training in infection prevention and control.9

At the beginning of the spread of the COVID-19 pandemic, health authorities, ethicists and the medical community of high-income countries, however, anxiously focused on the ICUs. In Europe, many hospitals increasingly reported to have quickly maximised resource capacities, reduced postponable interventions and—although challenging—being able to adequately respond to COVID-19 related medical needs of the population. Too long unnoticed, a tragedy of far greater magnitude was to be uncovered in the previously ignored ‘side stage’: the disproportionate dying of residents in nursing homes, already living under total isolation since several weeks. This phenomenon is being observed in almost all high-income countries, no matter if the residents live in a public or privately funded residential care facility.10 Even in New Zealand, one of the countries with the sharpest and—being an island—easier to perform lock down, the isolation of households through the creation of ‘household bubbles’ and one of the lowest infection rates, the disproportionate dying in nursing homes was not preventable.11 What was happening? Was it a law of nature that this population was seemingly dying anyway only due to their frailty and comorbidities? And is keeping next of kin, significant others or legal representatives away the best these countries can do in order to protect citizens living in residential care facilities?

It becomes more and more evident that the ‘nursing home bubble’ is not a safe place, but on the contrary, a place of highly elevated risk independently from lockdown conditions.12 Thus, our question becomes a rhetorical one and the answer is: no, it is not,8–14 and this insight is not new. We could have known that from Virchow, Semmelweis or James Carville’s famous Bill Clinton election campaign slogan of the fundamental relevance of economic aspects (Box 1).

Box 1. Social sciences and public health central insights on infections.

An infectious ‘enemy’ does not primarily reside in ‘foreigners’ or ‘others’ (social or religious groups, migrants, visitors, a ‘they’), carrying infections to a whatsoever ‘inside’ (countries, institutions, families, a ‘we’).

Demarcating boarders via mechanical barriers or defining ‘in’ and ‘out’ groups is a social construction, a myth never able to stop a natural phenomenon such as a viral epidemic.

People in large households (or camps) are vulnerable to infections due to their social situation, therefore, not external, but internal factors are decisive.

In health and social care facilities, where people at high risk live closely together, infections, nosocomial or not, are rapidly spread.

The health and social care staff contribute significantly to the spread of the disease.

This is aggravated if teams are understaffed, underequipped, underpaid, sent to work even with symptoms, being undertested altogether with the residents: It's the economy, stupid!

It does not matter whether this is due to depleted public health and social care services or the maximisation of shareholder value of big private companies running residential care facilities as capital investments.

This is the story of the COVID-19 tragedy observable in many high-income countries in these days, told through the lens of medicine as a social science, focusing history of medicine and social epidemiology: with the pandemic spread of COVID-19, wealthy countries have built their responses informed by natural science and epidemiology,4 focusing the acute setting, personal protective equipment and testing, and establishing ethics guidelines for the expected ‘tough’ triage of lifesaving resources like ventilators or extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO) in acute hospitals.15 In large long-term care facilities, crowded with a vulnerable high-risk population, healthcare workers or (before the total isolation) next-of-kin meanwhile infected an ‘individual zero’. As COVID-19 can affect an individual without (initially) being symptomatic, the virus easily spread despite lockdown conditions via healthcare teams and residents’ interactions. This was observable even in highly skilled, excellent nursing facilities with the staff themselves being at high risk, literally turning nursing homes into ‘grounds zero’ and unwillingly contributing to the deaths of care-dependent people who cannot afford personal care at home or in a safer setting.16 In many high-income countries, already before COVID-19, a great ‘viral dying’ can be observable in residential care facilities every winter. Compared with that, COVID-19 is much deadlier, and we currently have no vaccination and only very limited treatment options.

As the current evidence therefore increasingly reveals,8–14 16 age, frailty and comorbidities are important risk factors, but the social context of nursing homes as well as other communal establishments10 in many high-income countries contributes, according to Virchow’s social hygiene hypothesis, immensely to the death toll itself, with a variation from zero % (Hong Kong) to up to 85% of all COVID-19 related deaths according to official figures (Canada), with excess rates of nursing home deaths not entirely being dependent on the total share of national COVID-19 related deaths.10 Nurses, administrators, housekeeping staff and doctors working in ‘nursing home bubbles’ should not feel and cannot be made guilty. These professionals are the ones who have committed themselves to care professionally for this particularly vulnerable population ‘behind closed doors’. It is the custodial logic inherent to many places of residential care that bears the risk of creating a system of high-risk and deadly institutions. Policies of banning visits indiscriminately were ineffective in preventing this phenomenon and negatively impacted both physical and mental health as well as quality of life.17 18 The current evidence strongly suggests that the isolation measures have not been effective in preventing the COVID-19 spread. In addition, they may impact morbidity and mortality, for example, due to the aggravation of dementia and psychiatric diseases by constraining social contacts and by limiting access to necessary medical care, such as visits of General Practitioners (GPs) and palliative care specialists, physiotherapists, podologists and others. Therefore, the social death of the most vulnerable may precede the biological one due to the continued separation from significant others.

What could be an agenda to address this tragedy in residential care facilities of high-income countries? First, primary care has to be strengthened, in order that authorities, GPs, managers and nursing staff are able to plan and respond effectively to the emerging care needs of people living in residential care facilities. Second, both creative and safe strategies should be found that enable residents to keep in contact with their loved ones and legal representatives, thus maintaining quality of life and ensure essential human rights. There is no logic in believing that properly instructed spouses or other next of kin as well as legal representatives are more dangerous than GPs, nurses or housekeeping staff are, and in fact current evidence supports this assumption from social epidemiology and history of infectious diseases.18 In contrast to staff, relatives do not have to care for 20 nursing home residents at once on a busy day, but just visit their one and only mother, father, child or best friend, give their love, sense of belonging and protection, thus providing individual care, maintaining quality of life and immensely alleviating the challenging care work of the skilled staff under lock down conditions. In addition, nursing homes need the best protective material and training as to how to use it for staff and relatives alike.

An additional cautionary note is necessary: not all nursing home residents have lost decision-making capacity. Many of them do have capacity. They must therefore be involved in decisions on medical care and on taking or averting risks. Although many residents want to be cared for in their homes in case of a severe deterioration of health, not all want to forego life-prolonging treatment, some want to be transferred to hospitals and ICUs, which should be addressed by state-of-the-art advance care planning.19 Some residents weigh freedom and safety differently and want to see children or grandchildren, as is guaranteed by democratic states to all citizens who always also have responsibilities for their community. Administrators of nursing homes should therefore do the best to offer practical, creative solutions, for example, to separate ‘risk taking’ and ‘risk averting groups’ in order to minimise risks both to the staff and to residents.

What could be the more general lesson to be learnt from this situation in residential care facilities, taking place in many high-income countries, which the Canadian philosopher Monique Lanoix labelled as a humanitarian crisis?20 As large living communities of vulnerable individuals are at risk of becoming ‘grounds zero’, we might resume ‘old’ ideas of small communities of elderly or disabled persons, served by skilled, well paid healthcare teams within community neighbourhoods, which might even be cheaper in general. For sure, it would be more humane and safer, and, as up to 85% of COVID-19 related deaths in high-income countries are nursing home residents, with the exception of Hong Kong, implementing whole nursing home repeated testing of staff and residents and a short, sharp quarantine for residents, which should be carefully evaluated,8 and approximately 34% of all deaths are people living in communal establishments,10 the next pandemic might not be as deadly, even without having highly effective treatments or a vaccination at hand.8 To alleviate the global death toll of COVID-19 with the variety of contextual and local vulnerabilities and populations needing specific protection,4 like people living in refugee camps, undocumented working migrants in agriculture or the meat industry, often accommodated in large lodgings, as well as those living in poor neighbourhoods, we might finally again refer to Dr Virchow, calling for more social justice, as ‘politics is nothing but medicine at a larger scale’.

Social epidemiology and history of infectious diseases are key for a deeper understanding of the factors that contribute to these tragedies and for the development of better solutions. If a fair share of the billions currently being spent in high-income countries for basic natural science research and contact tracing goes to transformation, funding and staffing of the residential care setting,21 and also to other ‘big households’ around the world, to build safer living environments, the latter contributions might finally be the game changer to better deal with the next airborne disease pandemic and prevent unnecessary suffering and death for many people around the globe.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Professor Dr Ann Gallagher, University of Surrey (UK) for helpful comments on an earlier version of the manuscript and Professor Dr Wilhelm Hufen, University of Mainz (Germany) for his inputs and remarks regarding the unlawfulness of the total isolation in our discussions during the last few weeks.

Footnotes

Handling editor: Seye Abimbola

Collaborators: Professor Dr Ann Gallagher, University of Surrey (UK) for helpful comments on an earlier version of the manuscript. Professor Dr Wilhelm Hufen, University of Mainz (Germany) for his inputs and remarks regarding the unlawfulness of the total isolation in our discussions during the last few weeks.

Contributors: The authors cover the fields of sociology, nursing science, social epidemiology, evidence-based medicine, medical education and clinical ethics. We are working both in the fields of clinical practice, research and academic teaching and have been highly involved in developing national statements and policies in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic and also in transnational networking and guideline development. We discussed strategies for an adequate response to the COVID-19 pandemic. Departing from growing national and international evidence related to the dramatic situation in residential care facilities, we felt that there are important 'blind spots' of current understandings of its dynamics. The commentary reflects the summary of these discussions. We have all equally contributed to the review, interpretation and analysis of the current policies of confinement and COVID-19 outbreaks in nursing homes and other larger households of vulnerable persons and to the writing of the article and have read and understood the BMJ authorship policies.

Funding: The authors have not declared a specific grant for this research from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: Tanja Krones, Gabriele Meyer and Settimio Monteverde declare no competing interests according to the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors form (no payment of institutions or individually for any aspect of the submitted work, no patents or other relationships that could have influenced our submitted work.)

Patient and public involvement: Patients and/or the public were not involved in the design, or conduct, or reporting, or dissemination plans of this research.

Patient consent for publication: Not required.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data availability statement: There are no data in this work.

References

- 1.Virchow R. Mittheilungen über die in Oberschlesien herrschende Typhus-Epidemie (news about the typhoid epidemic in upper Silesia. Berlin: B. Reimer, 1848. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mackenbach JP. Politics is nothing but medicine at a larger scale: reflections on public health's biggest idea. J Epidemiol Community Health 2009;63:181–4. 10.1136/jech.2008.077032 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kadar N, Romero R, Papp Z. Ignaz Semmelweis: the "Savior of Mothers": On the 200th anniversary of his birth. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2018;219:519–22. 10.1016/j.ajog.2018.10.036 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Prasad V, Sri BS, Gaitonde R. Bridging a false dichotomy in the COVID-19 response: a public health approach to the 'lockdown' debate. BMJ Glob Health 2020;5:e002909. 10.1136/bmjgh-2020-002909 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kali E. Coronavirus and the social determinants of health. National community Reinvestment coalition. Available: https://ncrc.org/coronavirus-and-the-social-determinants-of-health/ [Accessed 13 Jun 2020].

- 6.Wilkinson D. Icu triage in an impending crisis: uncertainty, pre-emption and preparation. J Med Ethics 2020;46:287–8. 10.1136/medethics-2020-106226 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Emanuel EJ, Persad G, Upshur R, et al. Fair allocation of scarce medical resources in the time of Covid-19. N Engl J Med 2020;382:2049–55. 10.1056/NEJMsb2005114 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Salcher-Konrad M, Jhass A, Naci H, et al. Updated findings: living systematic review of emerging evidence on COVID-19 related mortality and spread of disease in long-term care, 2020. Available: https://ltccovid.org/2020/06/30/updated-findings-living-systematic-review-of-emerging-evidence-on-covid-19-related-mortality-and-spread-of-disease-in-long-term-care/ [Accessed 13 Jul 2020].

- 9.Burki T. England and Wales see 20 000 excess deaths in care homes. Lancet 2020;395:1602. 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)31199-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Comas-Herrera A, Zalakaín J, Litwin C, et al. Mortality associated with COVID19 outbreaks in care homes: early International evidence. International long-term care policy network, CPEC-LSE. Available: https://ltccovid.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/06/Mortality-associated-with-COVID-21-May-1.pdf [Accessed 13 Jun 2020].

- 11.Radio New Zealand Health staff working to deal with dementia care facility Covid-19 cluster. Available: https://www.rnz.co.nz/news/national/413602/health-staff-working-to-deal-with-dementia-care-facility-covid-19-cluster [Accessed 13 Jun 2020].

- 12.Koshkouei A, Abel L, Pilbeam C. How can pandemic spreads be contained in care homes? Available: https://www.cebm.net/covid-19/how-can-pandemic-spreads-be-contained-in-care-homes/ [Accessed 13 Jun 2020].

- 13.Birnbaum M, Booth W. Nursing homes linked to up to half of coronavirus deaths in Europe, who says. Washington post, 2020. Available: https://www.washingtonpost.com/world/europe/nursing-homes-coronavirus-deaths-europe/2020/04/23/d635619c-8561-11ea-81a3-9690c9881111_story.html [Accessed 13 Jun 2020].

- 14.Etard J-F, Vanhems P, Atlani-Duault L, et al. Potential lethal outbreak of coronavirus disease (COVID-19) among the elderly in retirement homes and long-term facilities, France, March 2020. Euro Surveill 2020;25:2000448 10.2807/1560-7917.ES.2020.25.15.2000448 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Truog RD, Mitchell C, Daley GQ. The Toughest triage — allocating ventilators in a pandemic. N Engl J Med 2020;382:1973–5. 10.1056/NEJMp2005689 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Barnett M, Grabowski D. Nursing homes are ground zero for Covid-19 pandemic. JAMA Health Forum 2020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gordon AL, Goodman C, Achterberg W, et al. Commentary: COVID in care Homes-Challenges and dilemmas in healthcare delivery. Age Ageing 2020;13:afaa113. 10.1093/ageing/afaa113 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Abramson A. Protecting nursing home residents during COVID-19. American psychological association. Available: http://www.apa.org/topics/covid-19/nursing-home-residents [Accessed 14 Jun 2020].

- 19.Brinkman-Stoppelenburg A, Rietjens JAC, van der Heide A. The effects of advance care planning on end-of-life care: a systematic review. Palliat Med 2014;28:1000–25. 10.1177/0269216314526272 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lanoix M. Nursing homes in the time of Covid-19. impact ethics. Available: https://impactethics.ca/2020/04/21/nursing-homes-in-the-time-of-covid-19 [Accessed 14 Jun 2020].

- 21.Oliver D. David Oliver: let's not forget care homes when covid-19 is over. BMJ 2020;369:m1629. 10.1136/bmj.m1629 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]