Abstract

Background:

Current preoperative risk assessment tools are often cumbersome, have limited accuracy, and are poorly adopted. The Care Assessment Need (CAN) score, an existing tool developed for primary care providers in the U.S. Veterans Administration health-care system (VA), is automatically calculated for individual patients using electronic health record data. Therefore, it could present an efficient preoperative risk assessment tool. The aim of this project was to determine if the CAN score can be repurposed as a preoperative risk assessment tool for patients undergoing total knee arthroplasty (TKA).

Methods:

A multicenter retrospective observational study was conducted using national VA data from 2013 to 2016. The cohort included veterans who underwent TKA identified through ICD-9 (International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision), ICD-10, and CPT (Current Procedural Terminology) codes. The focus of the study was the preoperative patient CAN score, a single numerical value ranging from 0 to 99 (with a higher score representing greater risk) that is automatically calculated each week using multiple data points in the VA electronic health record. Study outcomes of interest were 90-day readmission, prolonged hospital stay (>5 days), 1-year mortality, and non-routine patient discharge.

Results:

The study included 17,210 veterans. Their median preoperative CAN score was 75, although there was substantial variability in patient CAN scores among different facilities. A preoperative CAN score of >75 was significantly associated with mortality (odds ratio [OR] = 3.54), prolonged length of stay (OR = 1.97), 90-day readmission (OR = 1.65), and non-routine discharge (OR = 1.57). The CAN score had good accuracy with a receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve value of >0.7 for all outcomes except 90-day readmission.

Conclusions:

The CAN score can be leveraged as an extremely efficient way to risk-stratify patients before TKA, with results that surpass other commonly available and labor-intensive alternatives. As a result, this simple and efficient solution is well positioned for broad adoption as a standardized decision support tool.

Level of Evidence:

Prognostic Level IV. See Instructions for Authors for a complete description of levels of evidence.

Assessing preoperative risk is a critical part of surgical care, especially for resource-intense scheduled surgery such as total knee arthroplasty (TKA). Studies have demonstrated a wide variety of risk factors, including comorbid conditions, pain, and mental health status, associated with poor outcomes after TKA1,2. As a result, there have been efforts to design preoperative risk assessment tools to help surgeons to risk-stratify and counsel patients3. Unfortunately, currently available surgical risk assessment tools are often cumbersome, requiring patients or providers to manually input various data elements; have limited accuracy; and are poorly adopted4-7. Thus, there remains a need for a preoperative risk assessment tool that is both accurate and efficient for providers.

The Care Assessment Need (CAN) score was developed by the U.S. Veterans Administration (VA) to help primary care providers identify high-risk patients to better target resources and improve care coordination8. The score was developed using statistical models to identify high-risk primary care patients receiving care within the VA9. This team used information from the electronic health record to predict the risk of hospitalization or death during 90 days and 1 year and their study showed that better care coordination for high-risk patients could be achieved by using prediction models.

The CAN scores are automatically calculated from the VA’s national electronic health record using commonly recorded variables, including sociodemographic data, diagnosis (inpatient and outpatient), vital signs, health care utilization, medications, and laboratory values8,10,11. (For a complete list of the variables, see the “Model Terms” slide at https://www.hsrd.research.va.gov/for_researchers/cyber_seminars/archives/713-notes.pdf.) The CAN scores range from 0 to 99, with a higher score representing a greater risk of admission or death within a specified time period (90 days or 1 year) in relation to all other enrolled veterans. The CAN score is automatically updated weekly for all outpatients who have a primary care provider within the national VA system.

Given that this comprehensive score is available for most VA patients, and calculated weekly, we hypothesized that the CAN score could have value in preoperative risk stratification for patients undergoing TKA. To test this hypothesis, we evaluated the ability of a preoperative CAN score to predict postsurgical outcomes in a TKA cohort.

Materials and Methods

Data

A multicenter retrospective cohort study was conducted using national VA data from 2013 to 2016, obtained from the Corporate Data Warehouse (CDW). The CDW is a national VA data repository that encompasses a broad range of routinely collected patient, provider, facility, health-care system, and other administrative data including laboratory tests, pharmacy use, inpatient and outpatient utilization, appointments, vital status, staff information, and many other data sources. Patients were identified using ICD-9 (International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision), ICD-10, and CPT (Current Procedural Terminology) codes for TKA (see Appendix).

VA hospitals were identified by Station ID, and hospital TKA volume was a count of all cases over 3 years. Patients were excluded if their procedure was performed at a very-low-volume center (<10 TKAs in 4 years).

For this study, we utilized the CAN score for combined mortality and readmissions. We used the CAN score that was closest in time prior to the patients’ operative date. Four different patient outcomes of interest were evaluated: mortality at 1 year, prolonged hospital length of stay (>5 days), 90-day readmission (including both emergency room [ER] and inpatient admissions), and non-routine discharge (i.e., not discharged to home). Patients not eligible for analysis of 90-day readmission because their hospital stay had been >90 days or they had undergone outpatient surgery were excluded from this model, as were patients with a recorded length of stay of >365 days.

Analysis

Bivariate analyses were carried out with each independent variable and outcome variable using chi-square tests, Fisher exact tests, and analysis of variance (ANOVA). We performed a median split in order to set a cut point for the CAN score. We then performed multilevel mixed-effects logistic regression models, clustering by facility. Demographic predictors (e.g., age and sex) are already part of the CAN score calculations and thus were not included in our models. Analyses were performed using STATA/MP15 (StataCorp) and SAS Enterprise Guide 7.1 (SAS Institute).

Results

Cohort

Our initial cohort included 17,580 patients who underwent TKA from 2013 to 2016 in the VA health-care system. A CAN score was automatically calculated and recorded for 98% (17,210) of these patients within 6 months prior to their procedure. Overall patient demographics were consistent with the VA population, with 94% being men and a mean age of 65 years (Table I). Four patients were excluded because they had a >365-day of length of stay and 493 were excluded because they were not eligible for analysis of 90-day readmission.

TABLE I.

Demographics of Patients with and without a CAN Score of >75 from 2013 to 2016

| Demographics | CAN Score >75* | Total* (N = 17,210) | |

| Yes (N = 10,140) | No (N = 7,070) | ||

| Male sex | 9,444 (93) | 6,695 (95) | 16,139 (94) |

| Age (yr) | 66 ± 9 | 64 ± 8 | 65 ± 8 |

| Race | |||

| White | 7,906 (78) | 5,815 (82) | 13,721 (80) |

| Black | 1,597 (16) | 781 (11) | 2,378 (14) |

| American Indian | 63 (1) | 65 (1) | 128 (1) |

| Native Hawaiian | 44 (<1) | 37 (1) | 81 (<1) |

| Asian | 21 (<1) | 28 (<1) | 49 (<1) |

| Other | 252 (2) | 73 (1) | 325 (2) |

| Unknown | 257 (3) | 271 (4) | 528 (3) |

| Non-Hispanic ethnicity | 9,523 (94) | 6,697 (95) | 16,220 (94) |

The values are given as the number of patients with the percentage in parentheses except for age, which is given as the mean and standard deviation.

Facility Variation

Eighty-eight facilities performed >10 TKAs from 2013 to 2016. Four patients from 3 other facilities were excluded secondary to low procedure volume.

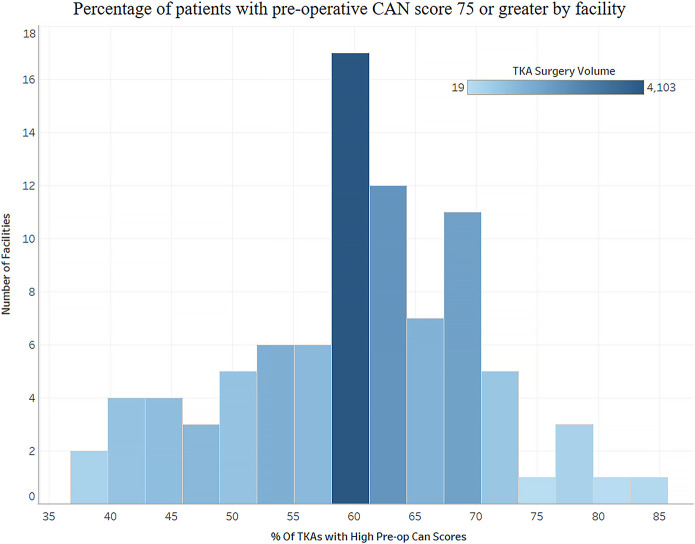

The median preoperative CAN score for the cohort was 75. The preoperative CAN scores varied substantially among facilities, with the percentage of patients with a preoperative CAN score of 75 ranging from 38% to 85% (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Variability in preoperative CAN scores among facilities.

Outcomes

In the total cohort, 19% returned for care in the ER (11%) or were readmitted for inpatient care (7%) within 90 days after the TKA, 1% died by 1 year, approximately 2% had a non-routine discharge, and 23% had a prolonged length of stay (Table II).

TABLE II.

Outcomes of Interest by CAN Score*

| Outcomes | CAN Score >75† | Total† (N = 17,210) | |

| Yes (N = 10,140) | No (N = 7,070) | ||

| Any readmission within 90 days after discharge | |||

| No | 7,955 (78) | 6,069 (86) | 14,024 (81) |

| Yes | 2,185 (22) | 1,001 (14) | 3,186 (19) |

| 90-day readmission | |||

| Inpatient stay | 887 (9) | 375 (5) | 1,262 (7) |

| ER visit | 1,298 (13) | 626 (9) | 1,924 (11) |

| All | 2,185 (22) | 1,001 (14) | 3,186 (19) |

| 1-yr mortality | |||

| No | 10,011 (99) | 7,044 (100) | 17,055 (99) |

| Yes | 129 (1) | 26 (<1) | 155 (1) |

| Non-routine discharge | |||

| No | 9,602 (95) | 6,797 (96) | 16,399 (95) |

| Yes | 175 (2) | 97 (1) | 272 (2) |

| Unknown/NA‡ | 363 (4) | 176 (2) | 539 (3) |

| Long length of stay (>5 days) | |||

| No | 7,040 (69) | 5,786 (82) | 12,826 (75) |

| Yes | 2,770 (27) | 1,121 (16) | 3,891 (23) |

| NA‡ | 330 (3) | 163 (2) | 493 (3) |

The CAN score was the risk combined event (mortality and readmission).

The values are given as the number of patients with the percentage in parentheses.

NA = not applicable because listed as an outpatient surgery (only has a visit date).

Models

Using a median split of 75, we performed logistical models accounting for hospital effects, with a CAN score of >75 as a bivariate outcome. We found no significant interaction between a CAN score of >75 and white race. This threshold cutoff of 75 was a significant predictor of all 4 outcomes (Table III). Three of the 4 outcomes had good predictive models (receiver operating characteristic [ROC] curve value of >0.7), the highest being non-routine discharge (ROC = 0.87).

TABLE III.

Models of CAN Score of >75 for Outcomes of Interest

| Outcome/Predictor* | Odds Ratio | P > |z| | 95% Confidence Interval | |

| Non-routine discharge (n = 16,675, Wald χ2 = 14.2, p < 0.001, ROC curve = 0.871 [95% CI, 0.853-0.889]) | ||||

| White | 1.43 | 0.043 | 1.01 | 2.03 |

| CAN score >75 | 1.57 | 0.001 | 1.20 | 2.05 |

| Constant | 0.00 | <0.001 | 0.00 | 0.01 |

| Length of stay >5 days (n = 16,721, Wald χ2 = 233.6, p < 0.001, ROC curve = 0.833 [95% CI = 0.826-0.841]) | ||||

| White | 0.75 | <0.001 | 0.67 | 0.83 |

| CAN score >75 | 1.97 | <0.001 | 1.80 | 2.17 |

| Constant | 0.19 | <0.001 | 0.13 | 0.26 |

| 1-yr mortality (n = 17,214, Wald χ2 = 35.2, p <0.001, ROC curve = 0.708 [95% CI = 0.668-0.749]) | ||||

| White | 1.29 | 0.233 | 0.85 | 1.96 |

| CAN score >75 | 3.54 | <0.001 | 2.32 | 5.40 |

| Constant | 0.00 | <0.001 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| 90-day readmission (n = 17,214, Wald χ2 = 178.7, p <0.001, ROC curve = 0.606 [95% CI = 0.595-0.616]) | ||||

| White | 0.75 | <0.001 | 0.68 | 0.83 |

| CAN score >75 | 1.65 | <0.001 | 1.52 | 1.79 |

| Constant | 0.20 | <0.001 | 0.18 | 0.23 |

White = yes versus no, and CAN score >75 = yes versus no. CI = confidence interval.

Discussion

The VA developed a patient assessment tool for primary care that automatically extracts a comprehensive range of patient data from the electronic health record11. In this study, we validated the potential of the CAN score as a preoperative screening and assessment tool for patients undergoing TKA. Our analysis revealed several important insights. First, the CAN score performed well as a risk assessment tool. Using a score cut point of 75, the CAN score models captured much of the variability, with ROC values of >0.7 for several important outcomes: prolonged length of stay, non-routine discharge, and 1-year mortality. This is a surprisingly good performance when compared with other calculators, such as the labor-intensive American College of Surgeons (ACS) risk calculator, which requires manual entry of 21 different preoperative risk factors12-14. There has been much interest in risk stratification for TKA. Many of the variables used in other studies on risk of TKA, including body mass index (BMI), sex, and laboratory values, are included in the CAN score7,15-17.

The CAN score was designed to be a risk tool to help allocate resources and improve care. In a prior study of patients >65 years of age enrolled in an exercise program, Serra et al. found that the CAN score did not correlate well with physical function tests18. Combining the findings from that study and our study generates some interesting questions. If the CAN score is predictive of mortality and hospitalization but not physical function, how does it fit into counseling of TKA patients? How should we stratify patients who are physically stronger preoperatively but at increased risk of readmission or mortality within a year? These are all important avenues for next steps.

This project’s purpose was to demonstrate the potential of the CAN score as a tool to help a physician to risk-stratify surgical patients efficiently. A dichotomized score (high versus low) provides an efficient clinical workflow to identify patients at high risk for poor outcomes. Some of the variables that lead to a high CAN score are potentially modifiable by the surgeon while others are not. A high CAN score could prompt a more thorough investigation of the medical record, provide time to medically optimize, and allow a patient to provide more informed consent.

In our assessment, we also found wide facility-level variation in patients’ preoperative CAN scores before TKA. This type of variation suggests a lack of standardization in preoperative risk assessment and is consistent with other research6. This variation highlights the potential utility for additional standardized preoperative assessment tools such as the CAN score. The CAN score, which is calculated automatically from electronic health record data, and is strongly correlated with outcomes, can provide greater patient assessment consistency as well as a consistent risk adjustment factor for performance quality assurance measures.

There are 3 main limitations to our work. First, the VA patient population is unique, which limits generalizability. Another limitation is that CAN-score availability is currently limited to the VA health-care system. However, because the CAN utilizes commonly recorded patient health-care variables, a similar system could be developed with other electronic health records utilizing similar data and methodology. Finally, our assessment was based on data for a specific surgical condition (TKA). Although we expect that these results will have some level of generalizability for other types of surgery, that assumption needs to be validated and quantified.

There are several important strengths to our research. Notably, as the VA is the largest health-care system in the U.S., this research included a large cohort of patients, from a wide geographic range, using a robust longitudinal database. In addition, the data utilized to calculate the CAN score were obtained from common structured data fields in the electronic health record. Since >96% of U.S. hospitals have electronic health records and there is a federal mandate for “meaningful use” of the electronic health record, implementing a CAN-type score would be of interest to non-VA health-care systems19,20.

An additional strength is that this method of risk assessment is automated, and therefore extremely efficient, for time-limited clinicians. Finally, this study highlights the benefit of utilizing the preexisting electronic health record data to improve clinical care.

Automated scores calculated from existing electronic health record data offer an efficient way to risk-stratify patients before TKA. Understanding the pronounced CAN score risk-threshold effect will require further evaluation. We recommend future research to validate and quantify the benefit of this risk assessment strategy in a prospective clinical trial.

Appendix

Supporting material provided by the authors is posted with the online version of this article as a data supplement at jbjs.org (http://links.lww.com/JBJSOA/A163).

Acknowledgments

Note: The authors are grateful for the research insight of Reese H. Clark.

Footnotes

Investigation performed at Palo Alto Veterans Hospital, Palo Alto, California

Disclosure: This work was supported by the nonprofit organization Palo Alto Veterans Institute for Research (PAVIR). The Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest forms are provided with the online version of the article (http://links.lww.com/JBJSOA/A162).

Disclaimer: The contents do not represent the views of the United States Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) or the United States Government.

References

- 1.Lingard EA, Katz JN, Wright EA, Sledge CB; Kinemax Outcomes Group. Predicting the outcome of total knee arthroplasty. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2004. October;86(10):2179-86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Baker PN, van der Meulen JH, Lewsey J, Gregg PJ; National Joint Registry for England and Wales; Data from the National Joint Registry for England and Wales. The role of pain and function in determining patient satisfaction after total knee replacement. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2007. Jul; 89(7):893-900. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cohen ME, Bilimoria KY, Ko CY, Hall BL. Development of an American College of Surgeons National Surgery Quality Improvement Program: morbidity and mortality risk calculator for colorectal surgery. J Am Coll Surg. 2009. June;208(6):1009-16. Epub 2009 Apr 17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wingert NC, Gotoff J, Parrilla E, Gotoff R, Hou L, Ghanem E. The ACS NSQIP Risk Calculator is a fair predictor of acute periprosthetic joint infection. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2016. July;474(7):1643-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Morris ZS, Wooding S, Grant J. The answer is 17 years, what is the question: understanding time lags in translational research. J R Soc Med. 2011. December;104(12):510-20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Eamer G, Al-Amoodi MJH, Holroyd-Leduc J, Rolfson DB, Warkentin LM, Khadaroo RG. Review of risk assessment tools to predict morbidity and mortality in elderly surgical patients. Am J Surg. 2018. September;216(3):585-94. Epub 2018 Apr 18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Twiggs JG, Wakelin EA, Fritsch BA, Liu DW, Solomon MI, Parker DA, Klasan A, Miles BP. Clinical and statistical validation of a probabilistic prediction tool of total knee arthroplasty outcome. J Arthroplasty. 2019. November;34(11):2624-31. Epub 2019 Jun 13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fihn S, Box T. Care Assessment Need (CAN) Score and the Patient Care Assessment System (PCAS): tools for care management. 2013. June 27 Accessed 2019 Dec 1. https://www.hsrd.research.va.gov/for_researchers/cyber_seminars/archives/713-notes.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wang L, Porter B, Maynard C, Evans G, Bryson C, Sun H, Gupta I, Lowy E, McDonell M, Frisbee K, Nielson C, Kirkland F, Fihn SD. Predicting risk of hospitalization or death among patients receiving primary care in the Veterans Health Administration. Med Care. 2013. April;51(4):368-73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fihn S, Box T. Update on the Care Assessment Need Score-CAN 2.0 and the Patient Care Assessment System (PCAS). 2016. January Accessed 2019 Feb 1. https://www.hsrd.research.va.gov/for_researchers/cyber_seminars/archives/1088-notes.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fihn SD, Francis J, Clancy C, Nielson C, Nelson K, Rumsfeld J, Cullen T, Bates J, Graham GL. Insights from advanced analytics at the Veterans Health Administration. Health Aff (Millwood). 2014. July;33(7):1203-11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Edelstein AI, Kwasny MJ, Suleiman LI, Khakhkhar RH, Moore MA, Beal MD, Manning DW. Can the American College of Surgeons Risk Calculator predict 30-day complications after knee and hip arthroplasty? J Arthroplasty. 2015. September;30(9)(Suppl):5-10. Epub 2015 May 27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bilimoria KY, Liu Y, Paruch JL, Zhou L, Kmiecik TE, Ko CY, Cohen ME. Development and evaluation of the universal ACS NSQIP Surgical Risk Calculator: a decision aid and informed consent tool for patients and surgeons. J Am Coll Surg. 2013. November;217(5):833-42.e1-3. Epub 2013 Sep 18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Keller DS, Ho JW, Mercadel AJ, Ogola GO, Steele SR. Are we taking a risk with risk assessment tools? Evaluating the relationship between NSQIP and the ACS Risk Calculator in colorectal surgery. Am J Surg. 2018. October;216(4):645-51. Epub 2018 Jul 19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Charlson M, Szatrowski TP, Peterson J, Gold J. Validation of a combined comorbidity index. J Clin Epidemiol. 1994. November;47(11):1245-51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ward DT, Metz LN, Horst PK, Kim HT, Kuo AC. Complications of morbid obesity in total joint arthroplasty: risk stratification based on BMI. J Arthroplasty. 2015. September;30(9)(Suppl):42-6. Epub 2015 Jun 3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bohl DD, Maltenfort MG, Huang R, Parvizi J, Lieberman JR, Della Valle CJ. Development and validation of a risk stratification system for pulmonary embolism after elective primary total joint arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty. 2016. September;31(9)(Suppl):187-91. Epub 2016 Mar 17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Serra MC, Addison O, Giffuni J, Paden L, Morey MC, Katzel L. Physical function does not predict care assessment need score in older veterans. J Appl Gerontol. 2017. January 1:733464817690677. Epub 2017 Jan 1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Office of the National Coordinator for Health Information Technology Quick stats. Accessed 2019 Dec 9. http://dashboard.healthit.gov/quickstats/quickstats.php

- 20.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Public Health and Promoting Interoperability Programs (formerly, known as Electronic Health Records Meaningful Use). Introduction. Accessed 2019. December 9 https://www.cdc.gov/ehrmeaningfuluse/introduction.html [Google Scholar]