Abstract

Oligonucleotides can be used to modulate gene expression via a range of processes including RNAi, target degradation by RNase H-mediated cleavage, splicing modulation, non-coding RNA inhibition, gene activation and programmed gene editing. As such, these molecules have potential therapeutic applications for myriad indications, with several oligonucleotide drugs recently gaining approval. However, despite recent technological advances, achieving efficient oligonucleotide delivery, particularly to extrahepatic tissues, remains a major translational limitation. Here, we provide an overview of oligonucleotide-based drug platforms, focusing on key approaches — including chemical modification, bioconjugation and the use of nanocarriers — which aim to address the delivery challenge.

Subject terms: Drug discovery, Antisense oligonucleotide therapy, Nucleic-acid therapeutics, Drug delivery

Oligonucleotide-based drugs have the potential to treat or manage a wide range of diseases. However, the widespread application of such therapies has been hampered by the difficulty in achieving efficient delivery to extrahepatic tissues. Here, Roberts et al. overview oligonucleotide-based drug platforms and assess approaches being employed to improve their delivery.

Introduction

Oligonucleotides are nucleic acid polymers with the potential to treat or manage a wide range of diseases. Although the majority of oligonucleotide therapeutics have focused on gene silencing, other strategies are being pursued, including splice modulation and gene activation, expanding the range of possible targets beyond what is generally accessible to conventional pharmaceutical modalities. The majority of oligonucleotide modalities interact with their cognate target molecules via complementary Watson–Crick base pairing, and so interrogation of the putative target sequence is relatively straightforward. Highly specific lead compounds can often be rationally designed based on knowledge of the primary sequence of a target gene alone and lead candidates identified by rapid screening. By contrast, conventional small-molecule pharmaceuticals require much larger, and often iterative, screening efforts followed by extensive medicinal chemistry optimization. In addition, the use of oligonucleotides allows for precision and/or personalized medicine approaches as they can theoretically be designed to selectively target any gene with minimal, or at least predictable, off-target effects. Furthermore, it is possible to target patient-specific sequences that are causative of rare disease1, specific alleles (for example, SNPs or expanded repeat-containing mutant transcripts can be preferentially targeted without silencing the wild-type mRNA2–5), distinct transcript isoforms6, pathogenic fusion transcripts (for example, Bcr–Abl7), traditionally ‘undruggable’ targets (for example, proteins that may lack hydrophobic pockets that may accommodate a small molecule that also inhibits protein activity)8,9 and viral sequences that evolve resistance to an oligonucleotide therapy (whereby the oligonucleotide design is modified to compensate for acquired escape mutations)10.

In addition to their ability to recognize specific target sequences via complementary base pairing, nucleic acids can also interact with proteins through the formation of three-dimensional secondary structures — a property that is also being exploited therapeutically. For example, nucleic acid aptamers are structured nucleic acid ligands that can act as antagonists or agonists for specific proteins11 (Box 1). Similarly, guide RNA molecules contain hairpin structures that bind to exogenously introduced Cas9 protein and direct it to specific genomic DNA loci for targeted gene editing12 (Box 2). An in-depth discussion of these modalities is beyond the scope of this Review.

As of January 2020, ten oligonucleotide drugs have received regulatory approval from the FDA (Fig. 1; Table 1). However, a major obstacle preventing widespread usage of oligonucleotide therapeutics is the difficultly in achieving efficient delivery to target organs and tissues other than the liver. In addition, off-target interactions13–17, sequence and chemistry-dependent toxicity and saturation of endogenous RNA processing pathways18 must also be carefully considered. The most commonly used strategies employed to improve nucleic acid drug delivery include chemical modification to improve ‘drug-likeness’, covalent conjugation to cell-targeting or cell-penetrating moieties and nanoparticle formulation. More recently developed approaches such as endogenous vesicle (that is, exosome) loading, spherical nucleic acids (SNAs), nanotechnology applications (for example, DNA cages) and ‘smart’ materials are also being pursued.

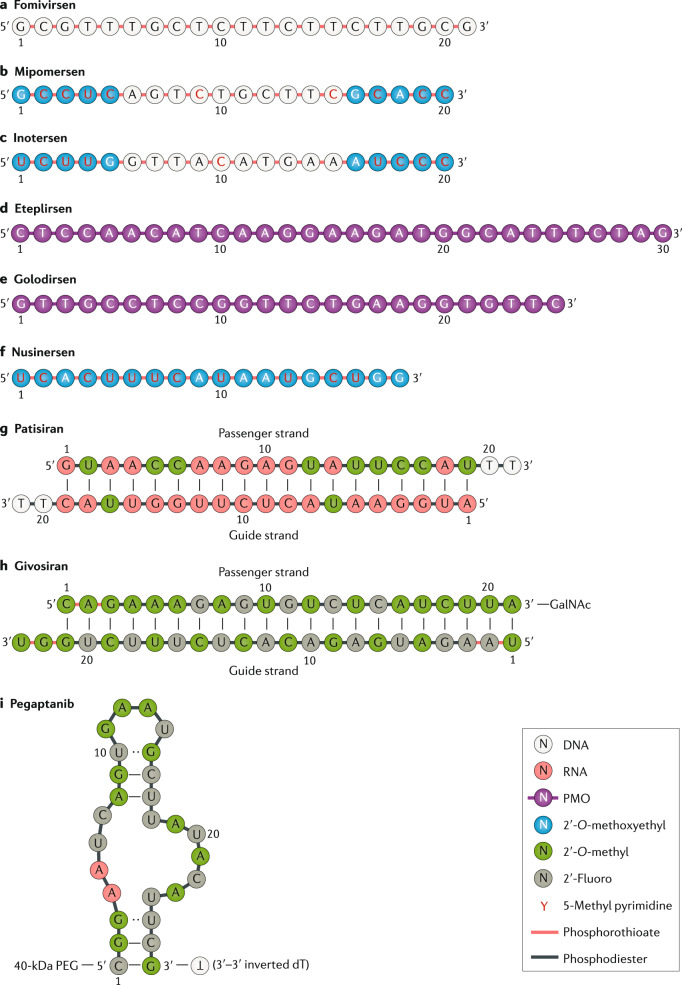

Fig. 1. Chemistry of FDA-approved oligonucleotide drugs.

Chemical composition of the FDA-approved oligonucleotide drugs fomivirsen (part a), mipomersen (part b), inotersen (part c), eteplirsen (part d), golodirsen (part e), nusinersen (part f), patisiran (part g), givosiran (part h) and pegaptanib (part i). Drugs are ordered by mechanism of action. Drug names, trade names, principal developing company, modality and RNA target are described in Table 1 for each compound. The drug defibrotide consists of a mixture of single-stranded and double-stranded ribonucleotides of variable length and sequence composition harvested from pig intestine. It therefore cannot be easily represented in the same manner as the other oligonucleotide drugs and so is not shown here. GalNAc, N-acetylgalactosamine; PEG, polyethylene glycol; PMO, phosphorodiamidate morpholino oligonucleotide. Part i structure adapted from ref.284, Springer Nature Limited.

Table 1.

FDA-approved oligonucleotide therapeutics

| Name (market name), company | Target (indication) | Organ (ROA) | Chemistry (modality) | FDA approval | Comments |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Fomivirsen (Vitravene), Ionis Pharma Novartis |

CMV UL123 (cytomegalovirus retinitis) | Eye (IVI) | 21mer PS DNA (first-generation ASO) | August 1998 |

First approved nucleic acid drug Local delivery Withdrawn from use owing to reduced clinical need |

|

Pegaptanib (Macugen), NeXstar Pharma Eyetech Pharma |

VEGF-165 (neovascular age-related macular degeneration) | Eye (IVI) | 27mer 2ʹ-F/2ʹ-OMe pegylated (aptamer) | December 2004 |

First approved aptamer drug Local delivery Limited commercial success due to competition |

|

Mipomersen (Kynamro), Ionis Pharma Genzyme Kastle Tx |

APOB (homozygous familial hypercholesterolaemia) | Liver (SQ) | 20mer PS 2ʹ-MOE (gapmer ASO) | January 2013 |

Rejected by EMA owing to safety Limited commercial success due to competition |

|

Defibrotide (Defitelio), Jazz Pharma |

NA (hepatic veno-occlusive disease) | Liver (IV) | Mixture of PO ssDNA and dsDNA | March 2016 | Unique sequence-independent mechanism of action |

|

Eteplirsen (Exondys 51), Sarepta Tx |

DMD exon 51 (Duchenne muscular dystrophy) | Skeletal muscle (IV) | 30mer PMO (steric block ASO) | September 2016 |

Systemic delivery to non-hepatic tissue Low efficacy |

|

Nusinersen (Spinraza), Ionis Pharma Biogen |

SMN2 exon 7 (spinal muscular atrophy) | Spinal cord (IT) | 18mer PS 2ʹ-MOE (steric block ASO) | December 2016 | Local delivery |

|

Patisiran (Onpattro), Alnylam Pharma |

TTR (hereditary transthyretin amyloidosis, polyneuropathy) |

Liver (IV) | 19 + 2mer 2ʹ-OMe modified (siRNA LNP formulation) | August 2018 |

First approved RNAi drug Nanoparticle delivery system Requires co-treatment with steroids and antihistamines |

|

Inotersen (Tegsedi), Ionis Pharma Akcea Pharam |

TTR (hereditary transthyretin amyloidosis, polyneuropathy) |

Liver (SQ) | 20mer PS 2ʹ-MOE (gapmer ASO) | October 2018 | Same gapmer ASO platform as mipomersen |

|

Givosiran (Givlaari), Alnylam Pharma |

ALAS1 (acute hepatic porphyria) | Liver (SQ) | 21/23mer Dicer substrate siRNA (GalNAc conjugate) | November 2019 |

Enhanced stability chemistry Hepatocyte-targeting bio-conjugate |

|

Golodirsen (Vyondys 53), Sarepta Tx |

DMD exon 53 (Duchenne muscular dystrophy) | Skeletal muscle (IV) | 25mer PMO (steric block ASO) | December 2019 | Same PMO chemistry platform as eteplirsen |

ASO, antisense oligonucleotide; dsDNA, double-stranded DNA; 2ʹ-F, 2ʹ-fluoro; GalNac, N-acetylgalactosamine; IT, intrathecal; IV, intravenous; IVI, intravitreal injection; LNP, lipid nanoparticle; 2ʹ-MOE, 2ʹ-O-methoxyethyl; 2ʹ-OMe, 2ʹ-O-methyl; NA, not applicable; PMO, phosphorodiamidate morpholino oligonucleotide; PO, phosphodiester; PS, phosphorothioate; ROA, route of administration; siRNA, small interfering RNA; SQ, subcutaneous; ssDNA, single-stranded DNA.

This Review will provide an overview of oligonucleotide-based drug platforms and focus on recent advances in improving oligonucleotide drug delivery.

Box 1 Aptamers — evolved nucleic acid ligands.

Aptamers are structured, single-stranded nucleic acid molecules (typically ~20–100 nucleotides) that fold into defined secondary structures and act as ligands that interact with target proteins by way of their three-dimensional structure and adaptive fit11. In contrast with other kinds of nucleic acid therapeutics, aptamers are not rationally designed. Instead, they are generated by an in vitro evolution methodology called SELEX (systematic evolution of ligands by exponential enrichment)286–288. Pegaptanib (originally developed by NeXstar Pharmaceuticals and Eyetech Pharmaceuticals) (Fig. 1i; Table 1), an RNA-based aptamer that targets the VEGF-165 vascular endothelial growth factor isoform as an anti-angiogenic therapy for neovascular age-related macular degeneration, is currently the only aptamer approved for clinical use.

Aptamers have primarily been used to target extracellular targets (for example, receptors), which somewhat simplifies the delivery problem for this class of oligonucleotide. However, as with other RNA species, RNA aptamers are rapidly degraded in most extracellular environments, meaning that chemical modification of aptamers is essential for in vivo activity. SELEX can be performed with libraries of chemically modified RNAs to a limited extent, as some nucleotide analogues, such as 2ʹ-fluoro and 2ʹ-O-methyl, are tolerated in both reverse transcriptase and T7 RNA polymerase enzymatic steps289,290. The introduction of post-SELEX chemical modifications is an alternative approach to further enhance aptamer drug-like properties.

The inherent chirality of amino acids in nature, in turn, enforces chirality in enzymatically produced nucleic acids (that is, l-amino acids and d-nucleotides). However, SELEX can be performed using enantiomeric protein analogues of target proteins synthesized with unnatural d-amino acids. The resulting aptamers are necessarily composed of d-RNA as a consequence of the restrictions of the enzymatic SELEX steps. However, the l-RNA versions of these identified aptamers can now be generated by chemical synthesis, which will thereby recognize the natural l-protein. These highly stable ‘mirror image’ aptamers are called spiegelmers (or l-RNA aptamers) and are not substrates for natural nucleases291.

Box 2 Nucleic acid-programmable nucleases.

The discovery that the CRISPR–Cas9 system could be repurposed for use in mammalian cells has led to a renaissance in the field of gene editing12. This system, which evolved as a form of bacterial immune defence against invading bacteriophages292–294, consists of a protein component (that is, the Cas9 enzyme that introduces double-stranded DNA breaks) and one or more guide RNA components (for example, the single guide RNA that directs Cas9 to a specific target site in genomic DNA). The modularity of the system allows for testing of many potential single guide RNAs, whereas the protein component is invariant. By contrast, previous gene editing approaches (for example, meganuclease, zinc finger nucleases and TALENs (transcription activator-like effector nucleases)) required costly and time-consuming protein engineering in order to confer target specificity. The CRISPR–Cas9 system induces double-strand breaks at specific genomic DNA loci, which are subsequently repaired by one of several DNA repair mechanisms. Such editing can be used to knockout a gene by disrupting the translational reading frame, excise a specific region from the genome, repair a point mutation or knock-in a desired DNA sequence. Furthermore, nuclease-deficient Cas9 variants (dCas9) have been developed that interact with target DNA sequences but do not induce double-strand breaks. dCas9 fusions with transcriptional activation (VPR; VP64-p65-Rta)295 or silencing proteins (KRAB)296 can therefore be used to target these fusion proteins to specific promoter sequences, and thereby modulate gene expression without inducing permanent changes in the DNA sequence. The majority of CRISPR–Cas9 gene editing therapies are dependent on the use of viral vectors for delivery of the effector components. The development of a compact Cas9 enzyme derived from Staphylococcus aureus (SaCas9) has enabled the delivery of the CRISPR system using adeno-associated viral vectors297. However, non-viral approaches using Cas9 ribonucleoprotein complexes loaded with synthetic oligonucleotide guide RNAs are also being developed298. These include gold nanoparticles (CRISPR–gold)299, liposomes300,301 and cell-penetrating peptide-modified Cas9 (ref.302).

Oligonucleotide-based platforms

Antisense oligonucleotides

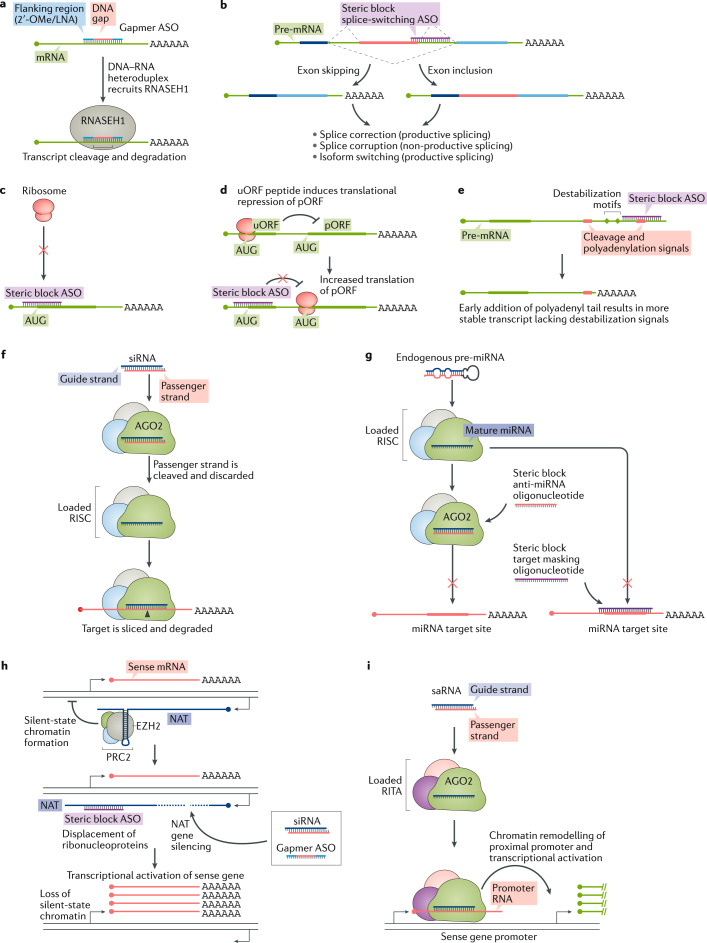

Antisense oligonucleotides (ASOs) are small (~18–30 nucleotides), synthetic, single-stranded nucleic acid polymers of diverse chemistries, which can be employed to modulate gene expression via various mechanisms. ASOs can be subdivided into two major categories: RNase H competent and steric block. The endogenous RNase H enzyme RNASEH1 recognizes RNA–DNA heteroduplex substrates that are formed when DNA-based oligonucleotides bind to their cognate mRNA transcripts and catalyses the degradation of RNA19. Cleavage at the site of ASO binding results in destruction of the target RNA, thereby silencing target gene expression (Fig. 2a). This approach has been widely used as a means of downregulating disease-causing or disease-modifying genes20. To date, three RNase H-competent ASOs have received regulatory approval; fomivirsen, mipomersen and inotersen (Fig. 1a–c; Table 1).

Fig. 2. Oligonucleotide-mediated gene regulatory mechanisms.

a | Gapmer antisense oligonucleotides (ASOs), consisting of a DNA-based internal ‘gap’ and RNA-like flanking regions (often consisting of 2ʹ-O-methyl (2ʹ-OMe) or locked nucleic acid (LNA) modified bases) bind to target transcripts with high affinity. The resulting RNA–DNA duplex acts as a substrate for RNASEH1, leading to the degradation of the target transcript. b | Steric block oligonucleotides targeted to pre-mRNA splicing signals modulate alternative splicing to either promote exon skipping or exon inclusion (depending on the type of splicing signal targeted). The resulting mature mRNA species can be spliced in a productive manner (for example, to restore the reading frame or to switch to an alternative isoform) or in a non-productive manner (for example, to remove an exon that is required for protein function and/or to disrupt the translation reading frame). c | Steric block antisense oligonucleotides can disrupt translation initiation by targeting the AUG start codon. d | Some transcripts contain upstream open reading frames (uORFs) that modulate the translational activity of the primary open reading frame (pORF). Targeting the uORF with steric block ASOs disrupts this regulation, leading to activation of pORF translation. e | Transcript stability can be modulated by shifting the usage of cleavage and polyadenylation signals. For example, a steric block ASO targeted to a distal polyadenylation signal results in the preferential usage of a weaker proximal polyadenylation signal. The resulting shorter transcript is more stable as it lacks RNA destabilization signals. f | Small interfering RNAs (siRNAs) enter the RNA-induced silencing complex (RISC), which consists of Argonaute 2 protein (AGO2), DICER1 and TARBP2, and the passenger strand is discarded. The guide strand directs the RISC to complementary target genes that are cleaved by the slicer activity of AGO2. g | Endogenous microRNAs (miRNAs) are loaded into miRISC. miRNA activity can be inhibited by steric block ASOs that either complex with the mature miRNA loaded in the RISC complex or by masking a target site through interactions with the targeted transcript. h | Natural antisense transcripts (NATs) recruit epigenetic silencing complexes, such as PRC2, to a sense gene locus. Interference of the epigenetic modifier protein association with the NAT using steric block ASOs or degradation of the NAT via siRNA or gapmer ASO results in ‘unsilencing’ of the sense gene. i | Small activating RNAs (saRNAs) can recruit the RNA-induced transcriptional activation (RITA) complex (consisting of AGO2, CTR9 and DDX5 (ref.285)) to low-copy promoter-associated RNA, leading to transcriptional activation of the proximal gene. EZH2, Enhancer of zeste homolog 2; PRC2, polycomb repressive complex 2.

Current-generation RNase H-competent ASOs generally follow the ‘gapmer’ pattern, whereby a central DNA-based ‘gap’ is surrounded by RNA-based (but chemically modified) flanking regions that promote target binding21 (Fig. 1b,c). Notably, RNASEH1 is active in both the cytoplasm and the nucleus22,23, thereby enabling the targeting of nuclear transcripts (for example, immature pre-mRNAs and long non-coding RNAs) that may be less accessible to other technologies (for example, small interfering RNA (siRNA); see below).

Steric block oligonucleotides are ASOs that are designed to bind to target transcripts with high affinity but do not induce target transcript degradation as they lack RNase H competence. Such oligonucleotides therefore comprise either nucleotides that do not form RNase H substrates when paired with RNA or a mixture of nucleotide chemistries (that is, ‘mixmers’) such that runs of consecutive DNA-like bases are avoided.

Steric block oligonucleotides can mask specific sequences within a target transcript and thereby interfere with transcript RNA–RNA and/or RNA–protein interactions. The most widely used application of steric block ASOs is in the modulation of alternative splicing in order to selectively exclude or retain a specific exon(s) (that is, exon skipping and exon inclusion, respectively). In these cases, the oligonucleotide ‘masks’ a splicing signal such that it becomes invisible to the spliceosome, leading to alterations in splicing decisions24,25. Typically, such splice correction approaches have been used to restore the translational reading frame in order to rescue production of a therapeutic protein26,27. However, the same technology can also be used for splice corruption, whereby an exon is skipped in order to disrupt the translation of the target gene28 (Fig. 2b). Given that alternative splicing is responsible for much proteomic diversity, it is possible that steric block oligonucleotides may also be utilized to promote isoform switching, thereby diminishing the expression of harmful protein isoforms and/or promoting the expression of beneficial ones. To date, three splice-switching ASOs have been FDA-approved; eteplirsen, golodirsen and nusinersen (Fig. 1d–f).

Notably, steric block ASOs have also been demonstrated to inhibit translation inhibition29,30 (Fig. 2c), interfere with upstream open reading frames that negatively regulate translation31 in order to activate protein expression32 (Fig. 2d), inhibit nonsense-mediated decay in a gene-specific manner by preventing assembly of exon junction complexes33 and influence polyadenylation signals to increase transcript stability34 (Fig. 2e).

RNAi — precision duplex silencers

siRNA molecules are the effector molecules of RNAi and classically consist of a characteristic 19 + 2mer structure (that is, a duplex of two 21-nucleotide RNA molecules with 19 complementary bases and terminal 2-nucleotide 3ʹ overhangs)35. One of the strands of the siRNA (the guide or antisense strand) is complementary to a target transcript, whereas the other strand is designated the passenger or sense strand. siRNAs act to guide the Argonaute 2 protein (AGO2), as part of the RNA-induced silencing complex (RISC), to complementary target transcripts. Complete complementarity between the siRNA and the target transcript results in cleavage (that is, slicer activity) of the target opposite position 10–11 of the guide strand, catalysed by AGO2 (refs36–38), leading to gene silencing (Fig. 2f). As of May 2020, two siRNAs have received FDA approval: patisiran and givosiran (Fig. 1g,h; Table 1).

Numerous variations of the archetypal siRNA design have provided benefits in terms of reduced passenger strand activity and/or improved potency. These include Dicer substrate siRNAs39, small internally segmented siRNAs40, self-delivering siRNAs (asymmetric and hydrophobic)41, single-stranded siRNAs42,43 and divalent siRNAs44.

microRNA inhibition

microRNAs (miRNAs) are endogenous RNAi triggers that have been implicated in a multitude of physiological and pathophysiological processes, including cancer45,46, cell cycle progression47, infectious disease48,49, immunity50, diabetes51, metabolism52, myogenesis53,54 and muscular dystrophy55,56. miRNAs therefore constitute a rich class of putative drug targets. miRNA hairpins embedded within long primary miRNA transcripts are sequentially processed by two RNase III family enzymes, DICER1 (Dicer) and DROSHA, which liberate the hairpin and then cleave the loop sequence, respectively37,57,58. The resulting duplex RNA (analogous to an siRNA) is loaded into an argonaute protein (for example, AGO2) and one strand discarded to generate the mature, single-stranded miRNA species. As with siRNAs, miRNAs guide RISC to target sequences where they initiate gene silencing. In contrast with siRNAs, miRNAs typically bind with partial complementarity and induce silencing via slicer-independent mechanisms59,60.

Steric block ASOs have been extensively utilized to competitively inhibit miRNAs via direct binding to the small RNA species within the RISC complex61 (Fig. 2g). Such ASOs are known as anti-miRNA oligonucleotides, anti-miRs or antagomirs62. The first anti-miRNA drug to enter clinical trials was miravirsen63 (later called SPC3649, Santaris Pharma A/S/Roche; Table 2), which is an ASO designed to treat chronic hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection via targeting of the liver-specific miRNA miR-122. This miRNA binds to two sites in the 5ʹ untranslated region of the HCV viral RNA and thereby stabilizes it48,64–68. Miravirsen sequesters miR-122, leaving the viral RNA exposed to exonucleolytic degradation with a concomitant failure of the virus to replicate and a reduction in viral load. Despite miravirsen showing promising results in terms of viral suppression, a rebound in HCV load was eventually observed in patient serum67, and an escape mutation that renders the HCV genome refractory to miravirsen has also been reported69. A rival anti-miR-122 drug, RG-101 (Regulus Therapeutics), for the treatment of HCV infection was similarly developed, but both miravirsen/SPC3649 and RG-101 are no longer in clinical development. Notably, Regulus is also developing anti-miRNA oligonucleotide drugs targeting miR-21 for Alport nephropathy70 and miR-17 for polycystic kidney disease71 (Table 2). Similarly, miRagen Therapeutics is developing cobomarsen, an oligonucleotide inhibitor of miR-155 for the treatment of cutaneous T cell lymphoma72, and remlarsen, a double-stranded mimic of miR-29 for the treatment of keloids73 (Table 2).

Table 2.

Selected oligonucleotide therapeutics that have entered development

| Company | Drug (partner) | Modality/delivery technology | Target/organ | Indication | Clinical trial stage |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ionis Pharmaceuticals | IONIS-HTTRx/RG6042 (Roche) | ASO/none | HTT/brain | Huntington disease | Phase III |

| Tofersen (Biogen) | ASO/none | SOD1/brain and spinal cord | ALS | Phase III | |

| IONIS-C9Rx | ASO/none | C9ORF72/brain and spinal cord | ALS | Phase II | |

| IONIS-MAPTRx | ASO/none | MAPT/brain | Alzheimer disease/FTD | Phase II | |

| IONIS-DNM2-2.5Rx (Dynacure) | ASO/none | DNM2/muscle | Centronuclear myopathy | Phase I | |

| Undisclosed | ASO/none | Various targets/heart and tumours | Various rare diseases, cardiometabolic disorders and cancers | Phase II | |

| Sarepta Therapeutics | Casimersen | PMO ASO/none | DMD exon 45/muscle | DMD | Phase III |

| SRP-5051 | PPMO ASO/peptide platform | DMD exon 51/muscle | DMD | Phase I | |

| Nippon Shinyaku Pharma | Viltolarsen | ASO/none | DMD exon 53/muscle | DMD | Phase II (approved in Japan) |

| Alnylam Pharmaceuticals | Fitusiran/ALN-AT3 (Sanofi Genzyme) | siRNA/GalNAc platform | SERPINC1/liver | Haemophilia A and B | Phase III |

| Lumasiran/ALN-GO1 | siRNA/GalNAc platform | HAO1/liver | Primary hyperoxaluria type 1 | Phase III | |

| Vutrisiran/ALN-TTRsc02 | siRNA/GalNAc platform | TTR/liver | Hereditary amyloidosis | Phase III | |

| Revusiran/ALN-TTRSC | siRNA/GalNAc platform | TTR/liver | Hereditary amyloidosis | Phase III — discontinued | |

| Inclisiran (Medicines Company and Novartis) | siRNA/GalNAc platform | PCSK9/liver | Hypercholesterolaemia | Phase III | |

| Wave Life Sciences | Suvodirsen | ASO/stereopure | DMD exon 51/muscle | DMD | Phase III — discontinued |

| WVE-120101; WVE-120102 (Takeda) | ASO/stereopure | Mutant HTT/brain and spinal cord | Huntingdon disease | Phase I | |

| Quark Pharmaceuticals | QPI-1002 | siRNA/none | TP53/kidney | Kidney delayed graft function/acute kidney injury | Phase III |

| Sylentis | Tivanisiran | siRNA/none | TRPV1/eye | Dry eye syndrome | Phase III |

| Moderna | AZD8601 (AstraZeneca) | mRNA/none | VEGFA/heart | Cardiac regeneration | Phase II |

| Santaris/Roche | Miravirsen | Anti-miRNA/none | miR-122/liver | Hepatitis C infection | Phase II — discontinued |

| Regulus Therapeutics | RG-012 (Sanofi Genzyme) | Anti-miRNA/none | miR-21/kidney | Alport syndrome | Phase II |

| RGLS4326 | Anti-miRNA/none | miR-17/kidney | Autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease | Phase I | |

| RG-101 | Anti-miRNA/GalNAc platform | miR-122/liver | Hepatitis C infection | Phase II — discontinued | |

| Mirage Therapeutics | Cobomarsen/MRG-106 | Anti-miRNA/none | miR-155/lymphomas | Cutaneous T cell lymphoma | Phase II |

| Remlarsen/MRG-201 | miRNA mimic/none | miR-29/skin | Cutaneous fibrosis | Phase II | |

| Arbutus Biopharma | AB-729 | Anti-miRNA/GalNAc platform | Hepatitis B virus HBsAg/liver | Hepatitis B infection | Phase I |

| Arrowhead Pharmaceuticals | ARO-AAT | siRNA/TRiM platform — GalNAc-related | AAT/liver | α1-Antitrypsin deficiency | Phase II |

| Silence Therapeutics | SLN124 | siRNA/GalNAc platform | TMPRSS6/liver | β-Thalassaemia | Phase I |

| Dicerna Pharmaceuticals | DCR-PHXC | siRNA/GalXC platform — GalNAc-related | LDHA/liver | Primary hyperoxaluria | Phase I |

| MiNA Therapeutics | MTL-CEPBA | saRNA/LNP (SMARTICLES) | CEBPA/liver | Hepatocellular carcinoma | Phase I/II |

| Avidity Biosciences | Undisclosed | siRNA or ASO/antibody platform | DMPK/muscle | Myotonic dystrophy I | Preclinical |

| PepGen Ltd | Undisclosed | siRNA or ASO/peptide platform | Undisclosed target/muscle and central nervous system | Neuromuscular disease | Preclinical |

| Stoke Therapeutics | Undisclosed | ASO/none | SCN1A/brain | Dravet syndrome | Preclinical |

ALS, amyotrophic lateral sclerosis; ASO, antisense oligonucleotide; DMD, Duchenne muscular dystrophy; FTD, frontotemporal dementia; GalNAc, N-acetylgalactosamine; LNP, lipid nanoparticle; miRNA, microRNA; PMO, phosphorodiamidate morpholino oligonucleotide; PPMO, peptide–PMO; saRNA, small activating RNA; siRNA, small interfering RNA.

An alternative approach to miRNA inhibition is the use of steric block ASOs to inhibit a specific miRNA regulatory interaction via masking of the target sequence on an mRNA transcript74,75 (Fig. 1g). However, the potential of steric block ASOs to disrupt these and other trans-acting regulators of RNA expression has yet to be fully realized.

Transcriptional gene activation

Many gene loci express long non-coding RNA species (for example, promoter-associated RNA and natural antisense transcripts, NATs) that are often involved in the transcriptional repression of the proximal protein-coding gene (or genes)76. Targeting these long non-coding RNAs with ASOs or siRNAs (referred to as antagoNATs77 or small activating RNAs78) can reverse the effects of this negative regulation leading to transcriptional activation (or ‘unsilencing’; Fig. 2h), as has been shown in the case of numerous disease-relevant genes including BACE1 (Alzheimer disease)79, BDNF (Parkinson disease)80, UBE3A (Angelman syndrome)81 and SCN1A (Dravet syndrome)82, among others. Alternatively, small activating RNAs can recruit epigenetic remodelling complexes to activate transcription via a distinct mechanism83,84 (Fig. 2i). Similarly, there is a growing appreciation of the importance of endogenous small RNAs in the nucleus that function as natural mediators of such transcriptional gene activation or silencing events, and may themselves constitute targets for oligonucleotide therapeutics85,86.

MiNA Therapeutics is currently developing MTL-CEBPA, a small activating RNA targeting CEBPA87,88 (CCAAT/enhancer-binding protein-α, a key transcription factor involved in hepatocyte differentiation and tumour suppression) delivered as a lipid nanoparticle formulation, as a treatment for hepatocellular carcinoma (Table 2). This drug is the first gene-activating oligonucleotide to be tested in a phase I clinical trial in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma and cirrhosis89.

An alternative approach for specific gene activation is the TANGO (Targeted Augmentation of Nuclear Gene Output) method currently under development by Stoke Therapeutics (Table 2). This strategy takes advantage of naturally occurring non-productive alternative splicing events, which result in premature termination codon generation and transcript degradation via nonsense-mediated decay. Splice-correcting ASOs are targeted to the sites of non-productive alternative splicing products to promote the generation of the productive transcript isoform, thereby upregulating target gene expression (Stoke Therapeutics’ science).

Delivery challenges

Achieving effective delivery of oligonucleotide therapeutics to many tissues remains a major translational challenge. Oligonucleotides are typically large, hydrophilic polyanions (single-stranded ASOs are ~4–10 kDa, double-stranded siRNAs are ~14 kDa), properties that mean they do not readily pass through the plasma membrane. For activity, systemically injected nucleic acid drugs must resist nuclease degradation in the extracellular space90, bypass renal clearance91,92, evade non-productive sequestration by certain plasma proteins93, avoid removal by the reticuloendothelial system (that is, mononuclear phagocytes, liver sinusoidal endothelial cells and Kupffer cells)94, cross the capillary endothelium at the desired target cell(s) within an organ/tissue by paracellular or transcellular routes, traverse the plasma membrane, escape the endolysosomal system before lysosomal degradation or re-export via exocytosis95 and arrive at the correct intracellular site of action. Systemic delivery to the central nervous system (CNS) presents an additional obstacle, as oligonucleotide-based therapeutics are generally not able to traverse the blood–brain barrier (BBB).

To date, the majority of oligonucleotide therapeutics (and almost all of the approved nucleic acid drugs) have focused on either local delivery (for example, to the eye or spinal cord) or delivery to the liver. The eye is considered an immune-privileged organ, meaning that this has been an anatomical target of choice for gene and oligonucleotide therapies (for example, pegaptanib and fomivirsen). Conversely, direct injection of oligonucleotides into the cerebrospinal fluid via lumbar puncture has been demonstrated to result in a favourable distribution of therapeutic molecules throughout the CNS (for example, nusinersen)96. The liver is a highly perfused tissue, with a discontinuous sinusoidal endothelium, meaning that uptake of free oligonucleotides and larger nanoparticles can occur rapidly before renal clearance. The liver also contains very high concentrations of receptors that can facilitate uptake and/or are rapidly recycled (for example, scavenger receptors and the asialoglycoprotein receptor). Although other highly vascularized tissues with discontinuous or fenestrated endothelia, such as the kidneys and spleen, are also sites for oligonucleotide accumulation, the development of effective technologies for extrahepatic systemic delivery remains a major goal for the oligonucleotide therapeutics field.

Strategies to enhance delivery

Chemical modification

Chemical modification represents one of the most effective approaches to enhance oligonucleotide drug delivery. Modification of the nucleic acid backbone, the ribose sugar moiety and the nucleobase itself has been extensively employed in order to improve the drug-like properties of oligonucleotide drugs and thereby enhance delivery92,97 (Fig. 3). Specifically, modification is utilized to improve oligonucleotide pharmacokinetics, pharmacodynamics and biodistribution. Specific patterns of modification are also required for the functionality of certain therapeutic modalities (for example, gapmers). The importance of chemistry is exemplified by the observation that extensive chemical modification of second-generation gapmer ASOs is sufficient to enable delivery to a wide variety of tissues, without the need for an additional delivery agent98. Furthermore, of the ten approved oligonucleotide therapies approved to date (Table 1), eight are ‘naked’ (that is, lacking an additional delivery vehicle) and so are dependent on chemical modification alone to facilitate their tissue delivery. This is also true of gapmer ASOs currently in development by Ionis Pharmaceuticals, including drugs for the treatment of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, Alzheimer disease, centronuclear myopathy and, most notably, Huntington disease99 (Table 2).

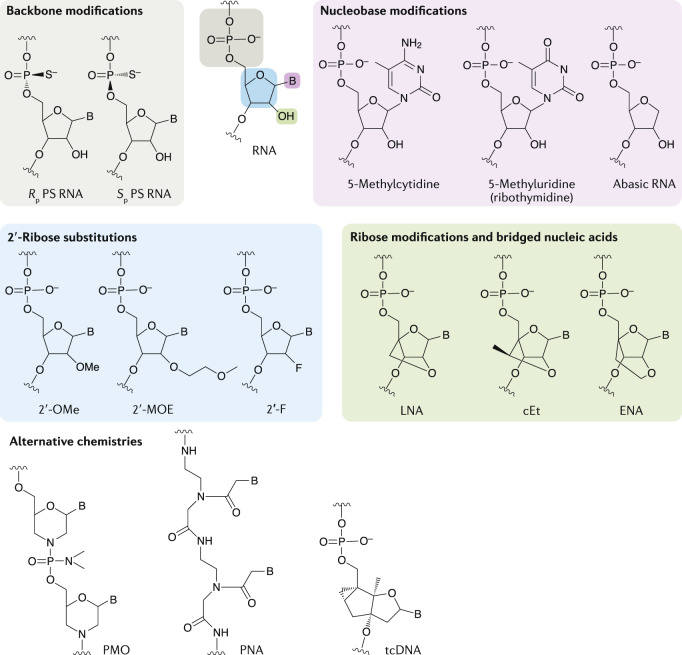

Fig. 3. Common chemical modifications used in oligonucleotide drugs.

Schematic of an RNA nucleotide and how it can be chemically modified at the backbone, nucleobase, ribose sugar and 2ʹ-ribose substitutions. B, nucleobase; cEt, constrained ethyl bridged nucleic acid; ENA, ethylene-bridged nucleic acid; 2ʹ-F, 2ʹ-fluoro; LNA, locked nucleic acid; 2ʹ-MOE, 2ʹ-O-methoxyethyl; 2ʹ-OMe, 2ʹ-O-methyl; PMO, phosphorodiamidate morpholino oligonucleotide; PNA, peptide nucleic acid; PS, phosphorothioate; tcDNA, tricyclo DNA.

Backbone modification

The incorporation of phosphorothioate (PS) linkages (Fig. 3), in which one of the non-bridging oxygen atoms of the inter-nucleotide phosphate group is replaced with sulfur, is widely used in therapeutic oligonucleotides100. There are many other kinds of backbone modification (for example, boranophosphate101), although these have been less commonly used. PS backbone modifications are readily tolerated in ASO designs and do not disrupt RNase H activity. By contrast, siRNAs that contain PS modifications at every linkage are less active than the equivalent phosphodiester (PO) siRNA102, and, as such, PS-containing siRNAs are typically modified at the termini only, if at all. Sulfated molecules, such as oligonucleotides containing PS linkages or thiol tails, are also taken up by scavenger receptors (such as the stabilins STAB1 and STAB2), which mediate their internalization into tissues such as the liver103–105. The incorporation of PS linkages has the dual effect of conferring nuclease resistance and promoting binding to proteins in both plasma and within cells. Oligonucleotide interactions with plasma proteins such as albumin106 have the effect of improving drug pharmacokinetics by increasing the circulation time (and therefore reducing renal clearance). However, binding of a PS-containing gapmer ASO to plasma α2-macroglobulin (A2M) was found to be non-productive93. PS modification of oligonucleotides also increases interactions with intracellular proteins (for example, nucleolin107–111) that are believed to promote their accumulation in the nucleus, the target site of action for splice-switching oligonucleotides.

Notably, resistance to cellular nucleases results in prolonged tissue retention and long-lasting drug effects. In cases where this is undesirable, in the case of toxicity due to prolonged gene silencing for example, the incorporation of one or more PO linkages can be used to ‘tune’ the durability of the oligonucleotide by reducing its nuclease stability112.

A disadvantage of PS backbone modifications is that they have the effect of reducing the binding affinity of an oligonucleotide for its target, a limitation that can be compensated for by incorporating additional types of modification (discussed below).

Stereochemistry

The introduction of an additional sulfur atom in a PS linkage results in the generation of a chiral centre at each modified phosphorous atom, with the two possible stereoisomeric forms (designated Sp and Rp, respectively) (Fig. 3). As such, a fully PS backbone 20mer oligonucleotide is in fact a racemic mixture of the 219 possible permutations (that is, more than half a million different molecules). The physicochemical properties of each stereocentre are distinct in terms of hydrophobicity/ionic character, nuclease resistance, target affinity and RNase H activity113. In particular, a 3ʹ-SpSpRp-5ʹ ‘stereochemical code’ contained within the ‘gap’ region of gapmer ASOs was found to be particularly active113. Wave Life Sciences has developed a scalable method of synthesizing oligonucleotides with defined stereochemistry at each PS linkage113, and is advancing oligonucleotide drugs with defined stereochemistry for various indications. However, they recently discontinued development of suvodirsen, a stereopure ASO designed to treat Duchenne muscular dystrophy (DMD) via skipping of dystrophin exon 51, owing to lack of efficacy in a phase I clinical trial114. Parallel clinical programmes with stereopure oligonucleotides targeting Huntington disease and C9ORF72 amyotrophic lateral sclerosis/frontotemporal dementia are ongoing (Table 2).

It is intriguing to speculate that the racemic mixtures of oligonucleotide drugs currently approved or in development contain many stereoisomers that exhibit low activity, thereby reducing the overall potency of the bulk mixture, and a small number of hyperfunctional molecules. Identification of the most active stereoisomers would provide a major step forwards in oligonucleotide drug development, allowing for lower doses with more efficacious compounds. Notably, it has been suggested that a stereorandom mixture of Sp and Rp centres is required to balance stability and silencing activity115. Nucleotide stereochemistry has also been exploited for aptamer development (Box 1).

Nucleobase modification

Strategies to modify nucleobase chemistry are also being investigated. For example, pyrimidine methylation (5-methylcytidine and 5-methyluridine/ribothymidine) (Fig. 3) has the effect of increasing the oligonucleotide melting temperature by ~0.5 °C per substitution97, and has been commonly incorporated into ASOs (such as those under development by Ionis Pharmaceuticals).

In addition, abasic nucleotides (that is, nucleotides lacking a nucleobase) (Fig. 2) have been used to abrogate miRNA-like silencing while maintaining on-target slicer activity116 and for allele-specific silencing of mutant HTT and ATXN3 transcripts117.

Terminal modification

Phosphorylation of the 5ʹ terminus of the siRNA guide strand is essential for activity, as this group makes an important contact in the MID domain of AGO2 (refs118,119). Removal of this terminal phosphate group by cellular phosphatases therefore has the effect of reducing siRNA potency. The addition of a 5ʹ-(E)-vinylphosphonate modification acts as a phosphate mimic that is not a phosphatase substrate. This modification also protects against exonuclease degradation and enhanced silencing in vivo120. Similarly, terminal inverted abasic ribonucleotides have been used to block exonuclease activity121. The conjugation of delivery-promoting moieties to oligonucleotide termini is discussed below.

Ribose sugar modification

Oligonucleotides are frequently modified at the 2ʹ position of the ribose sugar. Combinations of DNA (2ʹ-deoxy) and RNA bases are critical to the activity of gapmer ASOs (that is, for generating RNase H substrate heteroduplexes), and are utilized on the 3ʹ termini of some siRNA designs in order to confer nuclease resistance35.

Similarly, 2ʹ-O-methyl (2ʹ-OMe), 2ʹ-O-methoxyethyl (2ʹ-MOE) and 2ʹ-Fluoro (2ʹ-F) (Fig. 3) are among the most commonly used 2ʹ substituents. These modifications increase oligonucleotide nuclease resistance by replacing the nucleophilic 2ʹ-hydroxyl group of unmodified RNA, leading to improved stability in plasma, increased tissue half-lives and, consequently, prolonged drug effects. Furthermore, these modifications also enhance the binding affinity of the oligonucleotide for complementary RNA by promoting a 3ʹ-endo pucker conformation (RNA-like) of the ribose122,123. These 2ʹ-ribose modifications are not compatible with RNase H activity, meaning they are typically used for steric block oligonucleotides, or for the flanking sequences in gapmer ASOs. Although 2ʹ substitutions that enhance binding affinity are not improvements in delivery per se, they can compensate for limited drug bioavailability as the fraction of the injected dose that reaches its intended target is more active.

For steric block and gapmer ASOs, the oligonucleotide simply needs to bind to its cognate target (and support RNase H cleavage with a DNA gap in the case of the latter). For siRNAs, the situation is more complex as the oligonucleotides must maintain the capacity for loading into an AGO2 protein and support slicer cleavage. However, extensive chemical modification has been reported using 2ʹ-OMe and 2ʹ-F chemistries124, and active siRNAs have been generated in which every single 2ʹ-hydroxyl is modified, suggesting that the RNAi machinery is remarkably tolerant of chemical modification125,126. Furthermore, full chemical modification has been shown to be highly important for the activity of siRNA bioconjugates127 (discussed below). Conversely, the introduction of 2ʹ-ribose modifications at certain specific positions can ablate RISC loading and silencing activity. This phenomenon has been exploited in order to inactivate the passenger strand of the siRNA duplex, and thereby minimize its potential to mediate off-target silencing effects128.

2ʹ-MOE modifications are not typically incorporated into siRNA designs (the one exception being single-stranded siRNAs42). Alnylam Pharmaceuticals has developed two patterns of siRNA chemical modification that form the basis for many of the products in their development pipeline129. The first is standard template chemistry, which consist of an alternating pattern of 2ʹ-F and 2ʹ-OMe modifications at all ribose positions. This design was shown to increase siRNA potency by more than 500-fold relative to the unmodified PO siRNA in some cases126. The now-discontinued drug revusiran (Table 2), targeting TTR for transthyretin amyloidosis, is an example of a standard template chemistry siRNA design130. The second approach is termed enhanced stability chemistry, in which siRNAs contain a greater proportion of 2ʹ-OMe than standard template chemistry siRNAs and also incorporate PS linkages at the two internucleotide bridges at the 3ʹ terminus of the guide strand and the 5ʹ termini of both strands129,131. The approved Alnylam drug givosiran (Fig. 1h) is an example of an enhanced stability chemistry siRNA design.

2ʹ-OMe modifications can also abrogate the immune responses that can be induced by ASOs, siRNAs and CRISPR guide RNAs (Box 2). These oligonucleotide drugs have the potential to stimulate immune reactions in both sequence and chemistry-dependent ways via cellular pattern recognition receptors located in the cytoplasm or endosome121,132,133. Specifically, the Toll-like receptors can induce the interferon response: TLR3 recognizes double-stranded RNA motifs; TLR7 and TLR8 recognize single-stranded RNA; and TLR9 recognizes unmethylated CpG dinucleotides134,135. Similarly, the RIG-I and PKR systems also recognize double-stranded RNA in the cytoplasm136. Some of these immunogenic effects of siRNAs can be ablated by the inclusion of 2ʹ-OMe modifications at key positions137,138. Conversely, incorporation of 5ʹ-triphosphate-modified oligonucleotides139, or conjugation with CpG motif-containing TLR9 agonists140,141, and other chemical modifications142 have been used to generate therapeutic immunostimulatory oligonucleotides.

Bridged nucleic acids

Bridged nucleic acids (BNAs) are types of nucleotide in which the pucker of the ribose sugar is constrained in the 3ʹ-endo conformation via a bridge between the 2′ and 4′ carbon atoms. The most commonly used variations are locked nucleic acid (LNA)143,144, 2′,4′-constrained 2′-O-ethyl (constrained ethyl) BNA (cEt) and, to a lesser extent, 2′‐O,4′‐C‐ethylene‐bridged nucleic acid (ENA)145,146 (Fig. 3). BNAs enhance both nuclease stability and the affinity of the oligonucleotide for target RNA (typically by an increase of 3–8 °C in melting temperature per modified nucleotide in the case of LNA147). BNA modifications have therefore been incorporated into the flanking regions of gapmers to improve target binding. As such, cEt-flanking 3–10–3 gapmers are more efficacious than the MOE 5–10–5 equivalents98. Conversely, BNA nucleotides are not compatible with RNase H-mediated cleavage and so are excluded from the DNA gap region. LNA modifications have also been utilized in steric block ASOs, such as miRNA inhibitors. For example, miravirsen and cobomarsen (discussed above) are both full PS ASO mixmers containing DNA and LNA modifications distributed throughout their sequences. Conversely, tiny LNAs are short (8mer) fully LNA-modified oligonucleotides designed to simultaneously inhibit multiple members of an miRNA family (as these may execute redundant physiological functions) through complementarity to the miRNA seed sequence that is common between family members148.

Alternative chemistries

Whereas the majority of oligonucleotides are derived from RNA or DNA, other chemistries have been developed that differ substantially from these natural archetypes. PMO (phosphorodiamidate morpholino oligonucleotide) is a charge-neutral nucleic acid chemistry in which the five-membered ribose heterocycle is replaced by a six-membered morpholine ring149,150 (Fig. 3). Sarepta Therapeutics is developing PMO-based steric block ASOs for exon skipping in the context of DMD (Table 2). To date, two PMO drugs have been approved by the FDA, eteplirsen and golodirsen (Fig. 1d,e; Table 1), which target exons 51 and 53 of the dystrophin mRNA, respectively. Sarepta is also developing further ASO products based on the same chemistry targeting dystrophin exons 43, 44, 45 (casimersen), 50, 52 and 55 (Sarepta Therapeutics’ pipeline) (Table 2). Additionally, Nippon Shinyaku Pharma recently published encouraging data on a rival exon 53-targeting PMO (viltolarsen, NS-065/NCNP-01)151 and received marketing authorization in Japan in March 2020 (see Related links) (Table 2).

Notably, PMO backbone linkages contain chiral centres, meaning that PMO drugs are necessarily racemic mixtures. In contrast with PS modifications described above, the effects of defined PMO stereochemistry have not been explored to date.

Another strategy that has been explored is the use of peptide nucleic acid (PNA), a nucleic acid mimic in which a pseudo peptide polymer backbone substitutes for the PO backbone of DNA/RNA152,153 (Fig. 3). As both PMOs and PNAs are uncharged nucleic acid molecules, they can be covalently conjugated to charged delivery-promoting moieties such as cell-penetrating peptides (CPPs) (discussed below). Conversely, a disadvantage of these chemistries is that both PMO and PNA interact minimally with plasma proteins, meaning that they are rapidly cleared via urinary excretion.

The use of a constrained DNA analogue that increases the stability of RNA target–oligonucleotide duplexes by 2.4 °C per modification, known as tricyclo-DNA (tcDNA) (Fig. 3), is also being investigated154. Interestingly, systemically administered tcDNA ASOs were shown to exhibit activity in the brain, suggesting that these molecules have the capacity to deliver oligonucleotides across the BBB155. Given the non-natural structures of PMO, PNA and tcDNA, these chemistries are less suitable to RNase H and RNAi applications but have instead been used in steric block oligonucleotides, and for splice correction in particular155–157. However, tcDNA has recently been incorporated into the flanking sequences of a gapmer designed to silence mutant HTT transcripts158.

A final example is the development of a novel short interfering ribonucleic neutral (siRNN) chemistry159. These siRNN molecules contain a modified phosphotriester structure that neutralizes the charge of the equivalent unmodified PO/PS linkages, and thereby promotes their uptake in recipient cells. siRNNs act as prodrugs, which are converted to classical siRNAs by thioesterases in the cytoplasm159.

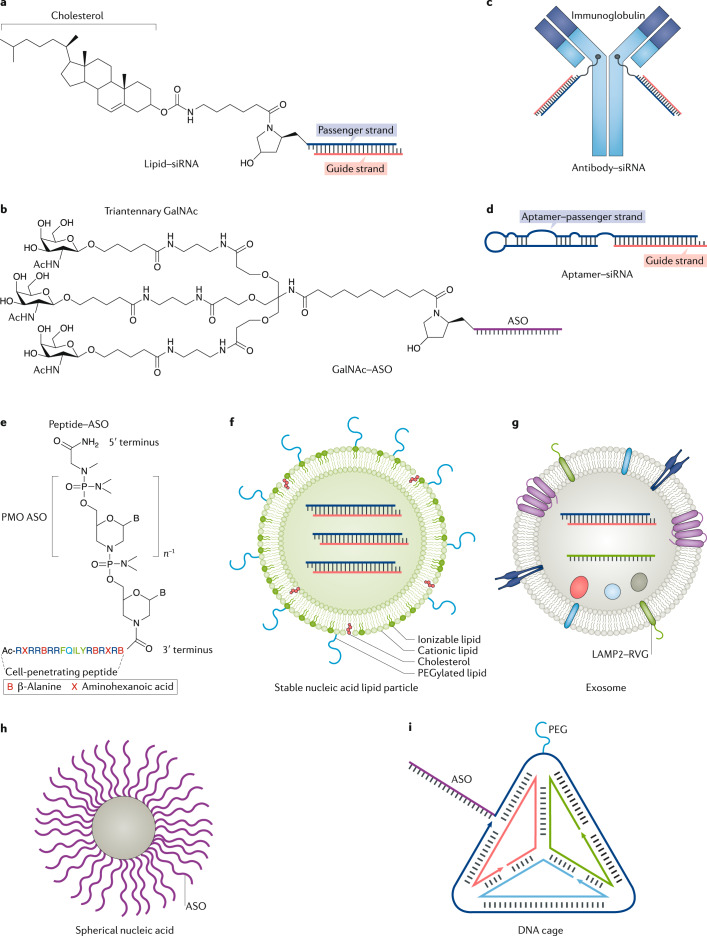

Bioconjugation

The delivery potential of ASOs and siRNAs can be enhanced through direct covalent conjugation of various moieties that promote intracellular uptake, target the drug to specific cells/tissues or reduce clearance from the circulation. These include lipids (for example, cholesterol that facilitates interactions with lipoprotein particles in the circulation)160–162, peptides (for cell targeting and/or cell penetration)5,163–167, aptamers168, antibodies9,169 and sugars (for example, N-acetylgalactosamine (GalNAc))170,171. Bioconjugates constitute distinct, homogeneous, single-component molecular entities with precise stoichiometry, meaning that high-scale synthesis is relatively simple and their pharmacokinetic properties are well defined. Furthermore, bionconjugates are typically of small size (relative to nanoparticle approaches, discussed below), meaning that they generally exhibit favourable biodistribution profiles (on account of being able to reach tissues beyond those with discontinuous or fenestrated endothelia).

For siRNAs there are four termini to which conjugates could potentially be attached. However, conjugation to the 5ʹ terminus of the guide strand is avoided as this terminal phosphate makes specific contacts with side-chain residues within the MID domain of AGO2 that are required for RNAi activity118,119. Conjugation to the passenger strand is generally preferred so as not to encumber the on-target silencing activity of the guide strand and, conversely, to diminish the off-target gene silencing potential of the passenger strand. Conjugates can be designed such that they are disassembled following cellular entry. This can be achieved by using acid-labile linkers that are cleaved in the endosome, disulfide linkers that are reduced in the cytoplasm or Dicer substrate-type siRNA designs172.

A common theme in oligonucleotide bioconjugation approaches is the promotion of interactions between the conjugate and its corresponding cell surface receptor protein, leading to subsequent internalization by receptor-mediated endocytosis. The interaction of bioconjugates with cell type-associated receptors thereby enables targeted delivery to specific tissues, or cell types within a tissue. To date, the physiological effects of saturating such receptor pathways have not been extensively studied173.

Lipid conjugates

Covalent conjugation to lipid molecules has been used to enhance the delivery of siRNAs and antagomir ASOs. Cholesterol siRNAs (conjugated to the 3ʹ terminus of the passenger strand) (Fig. 4a) have been utilized for hepatic gene silencing (for example, Apolipoprotein B, Apob)161 and, more recently, to silence myostatin (Mstn) in murine skeletal muscle (a target organ in which it has historically been particularly challenging to achieve effective RNAi) after systemic delivery174. Other lipid derivatives have also been exploited to enhance siRNA delivery. For example, siRNAs conjugated to α-tocopherol (vitamin E) were reported to induce potent silencing of Apob in the mouse liver175. In this case, the lipid moiety was conjugated to the 5ʹ terminus of the passenger strand of a Dicer substrate siRNA 27/29mer duplex. Upon cellular entry, the siRNA is cleaved by Dicer so as to generate the mature 19 + 2mer active RNAi trigger and to simultaneously cleave off the α-tocopherol175. Similarly, siRNAs conjugated to long-chain (>C18) fatty acids via a trans-4-hydroxyprolinol linker attached to the 3ʹ end of the passenger strand were capable of inducing comparable levels of Apob silencing to cholesterol-conjugated siRNAs160. The in vivo activity of lipid-conjugated siRNAs was demonstrated to be dependent on their capacity to bind to lipoprotein particles (for example, HDL and LDL) in the circulation160 and, thereby, hijack the endogenous system for lipid transport and uptake. Pre-assembly of cholesterol siRNAs with purified HDL particles resulted in enhanced gene silencing in the liver and jejunum relative to cholesterol siRNAs alone160. Furthermore, lipoprotein particle pre-assembly was also shown to affect siRNA biodistribution, with LDL siRNA particles taken up almost exclusively in the liver, and HDL siRNA particles primarily taken up by the liver, and also the adrenal glands, ovary, kidney and small intestine160. Accordingly, endocytosis of cholesterol siRNAs was shown to be mediated by scavenger receptor-type B1 (SCARB1, SR-B1) or LDL receptor (LDLR) for HDL and LDL particles, respectively160. In vivo association of siRNAs with the different classes of lipoprotein is governed by their overall hydrophobicity, with the more hydrophobic conjugates preferentially binding to LDL and the less lipophilic conjugates preferentially binding to HDL176.

Fig. 4. Oligonucleotide delivery strategies.

Schematics of various delivery strategies for small interfering RNAs (siRNAs) and antisense oligonucleotides (ASOs). a | Lipid–siRNA conjugate wherein cholesterol is conjugated to the 3ʹ terminus of the passenger strand. b | Triantennary N-acetylgalactosamine (GalNAc) moiety conjugated to an ASO. c | Antibody–siRNA conjugate. Oligonucleotides can be attached to the antibody or Fab fragment using click chemistry or thiol–maleimide linkages. d | Aptamer–siRNA conjugate. In vitro transcription can be used to generate a chimaeric aptamer–passenger strand as a single molecule. e | Peptide–ASO conjugate. The example is a PMO (phosphorodiamidate morpholino oligonucleotide) conjugated to a cell-penetrating peptide (Pip–9b2)209. f | Stable nucleic acid lipid particle encapsulating siRNAs. g | Engineered exosome with the brain-targeting rabies virus glycoprotein (RVG) peptide displayed on the outer surface255. The exosome consists of a membrane containing lipids and proteins derived from the donor cell. The exosome also contains therapeutic cargo (for example, siRNA) and proteins and nucleic acids (for example, microRNA) derived from the donor cell. h | Spherical nucleic acid nanoparticle consisting of a gold core coated in densely packed ASOs attached by metal–thiol linkages. i | Self-assembled DNA cage tetrahedron nanostructure. Oligonucleotide therapeutics (for example, siRNAs and ASOs) can be incorporated into the design of the DNA cage itself. Additional targeting ligands and polyethylene glycol (PEG) can be further conjugated to the nanostructure. LAMP2, lysosome-associated membrane protein 2; Pip, PMO/peptide nucleic acid internalization peptide. Part d shows a schematic of the PSMA (prostate-specific membrane antigen) aptamer adapted from ref.168, Springer Nature Limited.

GalNAc conjugates

GalNAc is a carbohydrate moiety that binds to the highly liver-expressed asialoglycoprotein receptor 1 (ASGR1, ASPGR) with high affinity (Kd = 2.5 nM)177 and facilitates the uptake of PO ASOs178,179 and siRNAs into hepatocytes by endocytosis129,170,171,180. ASGR1 is very highly expressed in the liver, and is rapidly recycled to the cell membrane, making it an ideal receptor for effective liver-targeted delivery. The interaction between GalNAc and ASGR1 is pH-sensitive, such that dissociation of the receptor and oligonucleotide conjugate occurs during acidification of the endosome129. The GalNAc moiety is subsequently subject to enzymatic degradation that liberates the oligonucleotide179. GalNAc-conjugated ASOs are preferentially delivered to hepatocytes in vivo, whereas unconjugated ASOs are primarily detected in non-parenchymal liver cells179.

Typically, a triantennary GalNAc structure (Fig. 4b) is used as the conjugated moiety, although there are other structural variants129,181. GalNAc conjugation enhanced ASO potency by ~7-fold in mouse, specific to the liver179, and by ~30-fold in human patients182. As such, GalNAc conjugation is now one of the leading strategies for delivering experimental oligonucleotide drugs currently in development, given its high liver silencing potential, small size relative to nanoparticle complexes, defined chemical composition and low cost of synthesis. In particular, GalNAc conjugation features heavily in the drug development pipelines of several pharma companies, most notably Alnylam, who are developing drugs for the treatment of diseases such as haemophilia A and B and primary hyperoxaluria type 1 (Table 2). Furthermore, a GalNAc-conjugated siRNA, givosiran (developed by Alnylam), received FDA approval in November 2019 (Table 1). Givosiran is a GalNAc-conjugated, blunt-ended, enhanced stability chemistry siRNA duplex targeting 5ʹ-aminolevulinate synthase 1 (ALAS1) for the treatment of acute hepatic porphyria183. Similarly, inclisiran, a second GalNAc-conjugated siRNA containing 2ʹ-F, 2ʹ-OMe and PS modifications (developed by Alnylam/The Medicines Company and acquired by Novartis184), is in late-stage clinical trials for the treatment of familial hypercholesterolaemia (Table 2). Inclisiran targets PCSK9 (proprotein convertase subtilisin/kexin type 9), which is a circulating factor that negatively regulates expression of LDLR and is primarily expressed in the liver. Hepatic PCSK9 knockdown therefore increases the availability of LDLR to remove LDL cholesterol from the circulation185,186. Subcutaneous injection of inclisiran resulted in long-term downregulation of circulating PCSK9 and LDL cholesterol (~6 months) suggesting that an infrequent treatment regimen may be a sufficient lipid-lowering strategy180,187.

Numerous additional pharmaceutical companies — namely Dicerna Pharmaceuticals, Silence Therapeutics, Arbutus Biopharma and Arrowhead Pharmaceuticals — are also developing GalNAc-conjugated oligonucleotide products (Table 2).

Antibody and aptamer conjugates

Although there is a plethora of technologies capable of delivering nucleic acids to hepatic cells, there is still a need for strategies that can target cell surface receptors specific to other tissues. Antibodies have been used as delivery vehicles for other kinds of drugs188, although their utility for oligonucleotide delivery is still in the early stages of development. Specific interactions between an antibody and a cell surface receptor have the potential to enable delivery to tissues and/or cell subpopulations that are not accessible using other technologies. Various receptors have been successfully targeted for siRNA delivery (Fig. 4d), including the HIV gp160 protein169, HER2 (ref.189), CD7 (T cell marker)190, CD71 (transferrin receptor, highly expressed in cardiac and skeletal muscle)191 and TMEFF2 (ref.192). Similarly, ASOs have also been conjugated with antibodies against CD44 (a neural stem cell marker), EPHA2 and EGFR193. In these cases, the ASO was delivered as a duplex with a DNA carrier strand to which the antibody was attached via click chemistry194. Such a design allows the DNA passenger to be degraded after cellular entry, thereby releasing the ASO from the complex194. Antibody–siRNA and antibody–ASO conjugates targeting tissues such as skeletal muscle are currently being developed by Avidity Biosciences (Table 2) and Dyne Therapeutics, respectively.

Similarly, the conjugation of therapeutic oligonucleotides to nucleic acid aptamers (Box 1) has also been explored for enhancing delivery of siRNAs and ASOs to specific target cells168,195,196. Aptamers can be considered ‘chemical antibodies’ that bind to their respective target proteins with high affinity, but present numerous advantages over antibodies as they are simple and inexpensive to manufacture (that is, by chemical synthesis), are smaller in size and exhibit lower immunogenicity197.

Peptide conjugates

Peptides are an attractive source of ligands that may confer tissue/cell-targeting, cell-penetrating (that is, CPPs) or endosomolytic properties onto therapeutic oligonucleotide conjugates. CPPs (also known as protein transduction domains) are short (typically <30 amino acids) amphipathic or cationic peptide fragments that are typically derived from naturally occurring protein translocation motifs (as in the case of HIV-TAT (transactivator of transcription protein), Penetratin 1 (homeodomain of the Drosophila Antennapedia protein) and Transportan (a chimeric peptide consisting of part of the galanin neuropeptide fused to the wasp venom, mastoparan)) or are based on polymers of basic amino acids (that is, arginine and lysine)198. One of the most promising applications of CPPs is their direct chemical conjugation to charge-neutral ASO chemistries, such as PMO and PNA. Several groups have pioneered the use of peptide–PMO (PPMO) conjugates (Fig. 4e) for the treatment of various diseases, most notably for dystrophin splice switching in the context of DMD. Early PPMO dystrophin exon skipping studies demonstrated efficacy using (RXR)4-PMO199,200 and the ‘B’ peptide (with sequence (RXRRBR)2XB)199,201, where X and B are 6-aminohexanoic acid and β-alanine spacer residues, respectively. The spacer residues are important for the optimal positioning of the charged arginine side chains202,203. This approach was further modified by generating a chimeric peptide consisting of B peptide fused with a muscle-targeting peptide (MSP)204. The resulting B–MSP–PMO conjugates demonstrated further dystrophin restoration efficacy in the mdx mouse model of DMD (although the relative arrangement of the peptide constituents was found to be important, with MSP–B–PMO exhibiting low activity)204,205. Exon skipping activity has also been reported when PMOs were conjugated to a different muscle-targeting peptide (M12) identified by phage display, although activity in the heart was minimal206. Subsequently, several series of peptides known as ‘Pip’s (PMO/PNA internalization peptide) consisting of R, B and X amino acids with an internal core containing hydrophobic residues have been developed164,207–209. Current-generation Pip–PMO conjugates (Fig. 4e) are much more potent than naked PMO in dystrophic animal models and, importantly, reach cardiac muscle (a tissue critical to the lethality of DMD) after systemic delivery164,209–211. The PPMO hydrophobic core is required for cardiac delivery, but can itself be scrambled, inverted, or individual residues substituted with only minimal changes to efficacy164,209. A major challenge for PPMO technology is toxicity, with evidence of renal damage in both rat (at very high doses) and cynomolgus monkey studies using arginine-rich CPP–PMOs212,213. Notably, the arginine content of the CPP is correlated with both exon skipping activity and nephrotoxicity209, and so current research efforts are directed towards the optimization of peptide chemistry to mitigate renal toxicity without compromising splice correction efficacy. Sarepta Therapeutics is developing SRP-5051, a PPMO designed to skip dystrophin exon 51 (Table 2). Additionally, PepGen Ltd is commercializing PPMO technology (Table 2).

PPMO uptake is energy dependent and appears to involve distinct endocytic pathways in skeletal and cardiac muscle cells214. It has been reported that treatment of chloroquine can enhance PPMO activity, suggesting that many conjugate molecules may not escape the endolyosomal compartment215. PPMOs have also been shown to spontaneously form micelles of defined sizes and surface charge, meaning that they are more readily taken up by endocytosis, in part mediated by scavenger receptors104.

PPMO technology has also been demonstrated to be effective for targeting CUG repeat-expanded transcripts in the context of myotonic dystrophy type I (DM1) (whereas naked PMO was completely ineffective)5, for splice correction to restore BTK expression for the treatment of X-linked agammaglobulinaemia216 and for delivery to the CNS in animal models of spinal muscular atrophy211. Similarly, brain delivery (to the cerebellum and Purkinje cells in particular) of an arginine-rich CPP–PMO conjugate after systemic delivery has also been demonstrated217.

PPMOs are also promising antibacterial (as they are capable of traversing the bacterial cell wall) and antiviral agents. Intranasal administration of (RXR)4 peptide–PMO conjugates targeting an essential bacterial gene acpP in murine infection models was shown to be bactericidal and increased survival218. Further, arginine-rich peptide–PMO conjugates were shown to exert protective effects in murine viral infection models of SARS-CoV219,220 and Ebola221.

Conjugation of peptides to charged-backbone oligonucleotides has been explored to a much lesser extent, as charge–charge interactions between the constituents complicate synthesis and purification, and conjugates may have the potential to self-aggregate. Nevertheless, there are a few examples of such conjugates. It was recently demonstrated that conjugation of an ASO gapmer to a ligand for the glucagon-like peptide 1 receptor (GLP1R) conferred targeted gene silencing in pancreatic β-cells166, the pancreas being a particularly challenging organ to deliver to. In this case, the targeting moiety was a 40-amino acid peptide consisting of a modified GLP1 sequence covalently conjugated to the ASO via the carboxy terminus. Peptide conjugation has also been explored for siRNA delivery. For example, the cyclic RGD peptide (recognized by αvβ3 integrin receptors) has successfully been used to deliver anti-VEGFR2 siRNA conjugates to mouse tumours167. Similarly, the CPPs TAT(48–60) and penetratin have been utilized as siRNA conjugates for delivery to the lung via the intratracheal route222. Although modest silencing of the target gene was observed, administration of the unconjugated peptides alone also exhibited a repressive effect. Furthermore, treatment with the penetratin–siRNA conjugates was associated with the release of pro-inflammatory markers TNF, IL-12 p40 and IFNα222. These observations highlight that potential peptide-mediated non-specific effects on gene expression and innate immune activation must be carefully considered.

Nanocarriers

Advances in nanotechnology and material science offer advantages and potential solutions to the challenge of oligonucleotide drug delivery, in particular the requirements for crossing biological barriers and transmembrane intracellular delivery. The major advantages of nanoparticle delivery systems include bespoke optimization of nanoparticle biophysical (for example, size, shape and chemical/material composition) and biological (for example, ligand functionalization for targeting) properties, allowing for highly tailored delivery platforms. A wide range of nanocarriers for nucleic acid drug delivery are at various stages of development, including non-covalent complexation with cationic polymers (for example, polyethylenimine)223, dendrimers224,225, CPPs (for example, MPG-8 (ref.226), PepFect6 (ref.227), RVG-9R228, and Xentry-KALA229) and inorganic methods (for example, calcium phosphate nanoparticles)230. Below, we focus on lipid-based formulations for oligonucleotide delivery and emerging novel approaches including endogenously derived exosomes, SNAs and self-assembling DNA nanostructures.

Lipoplexes and liposomes

Formulation with lipids is one of the most common approaches to enhancing nucleic acid delivery. Mixing polyanionic nucleic acid drugs with lipids leads to the condensing of nucleic acids into nanoparticles that have a more favourable surface charge, and are sufficiently large (~100 nm in diameter) to trigger uptake by endocytosis. Lipoplexes are the result of direct electrostatic interaction between polyanionic nucleic acid and the cationic lipid, and are typically a heterogeneous population of relatively unstable complexes. Lipoplex formulations need to be prepared shortly before use, and have been successfully used for local delivery applications228. By contrast, liposomes comprise a lipid bilayer, with the nucleic acid drug residing in the encapsulated aqueous space. Liposomes are more complex (typically consisting of cationic or fusogenic lipids (to promote endosomal escape231) and cholesterol PEGylated lipid) and exhibit more consistent physical properties with greater stability than lipoplexes232. For example, some lipid nanoparticles (LNPs), also known as stable nucleic acid lipid particles (Fig. 4f), are liposomes that contain ionizable lipid, phosphatidylcholine, cholesterol and PEG–lipid conjugates233,234 in defined ratios and have been successfully utilized in multiple instances. Landmark examples are the silencing of hepatitis B virus and APOB by siRNAs in preclinical animal studies137,235 and, more recently, the approval of patisiran, an siRNA that is delivered as an LNP formulation236. Encapsulation of nucleic acid cargos provides a means of protection from nuclease digestion in the circulation and in the endosome. Additionally, ionizable LNPs also associate with APOE, which further facilitates liver uptake via LDLR-mediated endocytosis237. Similarly, LNPs containing lipidoid or lipid-like materials have demonstrated robust siRNA-mediated silencing in rodents238,239 and non-human primates240.

A disadvantage of LNPs is that their delivery is primarily limited to the liver and reticuloendothelial system as the sinusoidal capillary epithelium in this tissue provides spaces large enough to allow the entry of these relatively large nanoparticles137,241,242. However, local delivery of LNPs has been used to successfully deliver siRNAs to the CNS after intracerebroventricular injection243. Conversely, the large size of nanoparticles is advantageous as it essentially precludes renal filtration244 and permits delivery of a higher payload.

LNPs can be further functionalized with peptides245, PEG246 or other ligands that confer cell-specific targeting (for example, GalNAc (hepatocytes)234,237, anisamide (lung tumours)247, strophanthidin (various tumours)248 and vitamin A (hepatic stellate cells)249). Notably, an increase in the complexity of LNPs complicates manufacture and may increase their toxicity, which is a major concern that may limit their clinical utility. For example, LNP siRNA particles (such as patisiran) require premedication with steroids and antihistamines to abrogate unwanted immune reactions250.

Exosomes

An area of nanotechnology that is gaining interest is based on the application of natural biological nanoparticles known as exosomes (a class of extracellular vesicle). Exosomes are heterogeneous, lipid bilayer-encapsulated vesicles approximately 100 nm in diameter that are generated as a result of the inward budding of the multivesicular bodies251,252. Exosomes are thought to be released into the extracellular space by all cells, where they facilitate intercellular communication via the transfer of their complex macromolecular cargoes (that is, nucleic acids, proteins and lipids)253,254. Exosomes present numerous favourable properties in terms of oligonucleotide drug delivery: exosomes are capable of traversing biological membranes, such as the BBB255; the presence of the marker protein CD47 protects exosomes from phagocytosis, thereby increasing their circulation time relative to liposomes256; exosomes are considered non-toxic and have been safely administered to patients with graft-versus-host disease257; exosomes have the potential to be produced in an autologous manner; exosomes from some sources have been shown to have inherent pro-regeneration and anti-inflammatory properties that may augment the effects of therapeutic oligonucleotide delivery258,259; and engineered exosomes can serve as a modular platform whereby combinations of therapies and/or targeting moieties can be deployed.

A major challenge for exosome therapeutics is the efficient loading of therapeutic oligonucleotide cargo. Vesicles can be loaded either endogenously (for example, by overexpression of the cargo in the producer cell line260) or exogenously (for example, by electroporation255,256,261, sonication262, co-incubation with cholesterol-conjugated siRNAs263,264 and so forth). The loading of exosomes with splice-switching PMOs has been achieved via conjugation with the CP05 peptide, which binds to CD63 (a marker commonly found on exosomes) so as to decorate the exosomes with PMO cargo265.

The pattern of exosome biodistribution can be favourably altered through the display of surface ligands, such as peptides like rabies virus glycoprotein (RVG) to enhance brain penetration and facilitate delivery to cells within the nervous system255,266,267 (Fig. 4g) or GE11 that promotes binding to tumour cells by interacting with EGFR268. Similarly, exosomes decorated with an RNA aptamer targeting PSMA (prostate-specific membrane antigen) were capable of delivering siRNAs to xenograft tumours and inducing tumour regression269.

Methods for the manufacture of therapeutic exosomes at high scale, including clinical grade, have been reported261. The use of mesenchymal stem cell lines (with the potential for immortalization) and culture in bioreactors enables large volumes of exosome-containing conditioned media to be generated. Subsequently, methods such as tangential flow filtration and size-exclusion liquid chromatography provide a scalable means of isolating therapeutic exosomes from these supernatants270. Therapeutic applications of engineered exosome technology are presently at an advanced preclinical stage for two companies: Codiak Biosciences and Evox Therapeutics.

Spherical nucleic acids

An alternative nanoparticle-based delivery strategy is the SNA approach. SNA particles consist of a hydrophobic core nanoparticle (comprising gold, silica or various other materials) that is decorated with hydrophilic oligonucleotides (for example, ASOs, siRNAs and immunostimulatory oligonucleotides) that are densely packed onto the surface via thiol linkages (Fig. 4h). In contrast to other nanoparticle designs, SNA-attached oligonucleotides radiate outwards from the core structure. While exposed, the oligonucleotides are protected from nucleolytic degradation to some extent as a consequence of steric hindrance, high local salt concentration, and through interactions with corona proteins271.

SNA particles carrying an siRNA targeting the anti-apoptotic factor Bcl2l12 were able to promote tumour apoptosis, reduce the tumour burden and extend survival in glioblastoma xenograft-bearing mice272. Importantly, this study demonstrated that SNAs have the potential to cross the BBB in both tumour-bearing mice (with impaired BBB integrity) and also in wild-type mice272, although the majority of SNA particles were deposited in the liver and kidneys. SNA particles have also been applied for topical delivery to skin keratinocytes in the context of diabetic wound healing (that is, GM3S-targeting siRNA)273 and psoriasis (that is, TNF-targeting ASO)274. SNA particles are currently being commercialized for oligonucleotide delivery applications by Exicure, Inc.

DNA nanostructures

DNA nanostructures, of which there are many varieties, have also been utilized for oligonucleotide delivery. These structures include DNA origami, whereby long DNA molecules are held in defined structures using short DNA ‘staples’ that enable a wide variety of complex shapes to be formed, including polygonal nanostructures such as DNA cages. DNA nanostructures typically self-assemble owing to base pairing complementarity of their constituent parts, and can be designed with precise geometries such that their physical properties (for example, size, flexibility and shape) can be fine-tuned in order to maximize their delivery potential. DNA nanostructures used for nucleic acid delivery applications will typically be modular structures that incorporate nucleic acid drugs (and targeting ligands such as aptamers) within the design of the structure itself. For example, DNA nanostructures have been designed that incorporate ASOs (Fig. 4i), siRNAs275 and immunostimulatory oligonucleotides276 displayed on the structure surface. A highly interesting property of DNA nanostructures is that they have been reported to not accumulate in the liver, and can be engineered to be small (~20 nm), meaning extrahepatic delivery is possible. However, further reducing the size of DNA nanostructures without additional functionalization will likely result in enhanced renal filtration, and overall lower bioavailability275,277.

Stimuli-responsive nanotechnology