Abstract

Novel antiviral active molecule 2- [(4,6-diaminopyrimidin-2-yl)sulfanyl]-N-(4-fluoro- phenyl)acetamide has been synthesised and characterized by FT-IR and FT-Raman spectra. The equilibrium geometry, natural bond orbital calculations and vibrational assignments have been carried out using density functional B3LYP method with the 6-311G++(d,p) basis set. The complete vibrational assignments for all the vibrational modes have been supported by normal coordinate analysis, force constants and potential energy distributions. A detailed analysis of the intermolecular interactions has been performed based on the Hirshfeld surfaces. Drug likeness has been carried out based on Lipinski's rule and the absorption, distribution, metabolism, excretion and toxicity of the title molecule has been calculated. Antiviral potency of 2- [(4,6-diaminopyrimidin-2-yl)sulfanyl]-N-(4-fluoro-phenyl) acetamide has been investigated by docking against SARS-CoV-2 protein. The optimized geometry shows near-planarity between the phenyl ring and the pyrimidine ring. Differences in the geometries due to the substitution of the most electronegative fluorine atom and intermolecular contacts due to amino pyrimidine were analyzed. NBO analysis reveals the formation of two strong stable hydrogen bonded N–H···N intermolecular interactions and weak intramolecular interactions C–H···O and N–H···O. The Hirshfeld surfaces and consequently the 2D-fingerprint confirm the nature of intermolecular interactions and their quantitative contributions towards the crystal packing. The red shift in N–H stretching frequency exposed from IR substantiate the formation of N–H···N intermolecular hydrogen bond. Drug likeness and absorption, distribution, metabolism, excretion and toxicity properties analysis gives an idea about the pharmacokinetic properties of the title molecule. The binding energy −8.7 kcal/mol of the nonbonding interaction present a clear view that 2- [(4,6-diaminopyrimidin-2-yl)sulfanyl]-N-(4-fluoro- phenyl) acetamide can irreversibly interact with SARS-CoV-2 protease.

Keywords: Density functional theory, Natural bond orbital analysis, Hirshfeld surface, FT-IR and Raman spectra, SARS-CoV-2

Graphical abstract

Highlights

-

•

NBO analysis elucidates the effect of hyperconjugation and rehybridization.

-

•

FT-IR and FT-Raman Spectral analysis substantiates the formation of intermolecular interactions

-

•

Hirshfeld surface analysis reveals multiple hydrogen bonded interactions

-

•

Drug likeness and ADMET analysis reveals pharmacokinetic properties

-

•

Molecular docking shows the interaction of DAPF with SARS-CoV-2 protease.

1. Introduction

Pyrimidine and its derivatives take up a key position in the field of medicinal chemistry due to its multifarious pharmacological activities. In an urge for searching new promising small therapeutic agents, we introduce 2- [(4,6-diaminopyrimidin-2-yl)sulfanyl]-N-(4-fluoro- phenyl) acetamide (DAPF). In the present study, we focus on the investigation on the molecular structure, electronic properties, vibrational spectra and molecular docking of the title compound, with the hope that the results of the present investigation may be decisive in the prognosis of its mechanism of biological activity.

Pyrimidines, the fundamental building blocks for nucleic acids, are invoking much scientific interest owing to their potential biological activities and pharmacological applications [1]. Pyrimidines are also reported to show anti-HIV, [2] antidengue [3] and anticancer [4] activities. The title compound DAPF, which has the amino substituent at the 4,6- position are found to be Troponin I-Interacting Kinase (TNNI3K) Inhibitors [5]. Also, the presence of the amino group in the 4-position are found to be HIV inhibitors [6]. Aminopyrimidines and polyaminopyrimidines are important therapeutic agents used as tyrosine kinase inhibitor such as Gleevec and the hypocholesterolemic agent rosuvastatin [[7], [8], [9]].

Molecular and spectral investigation of 2-mercapto pyrimidine and 2,4-diamino-6-hydroxy-5-nitroso pyrimidine [10], pyrazinamide [11], DFT assisted Quantum computations of aminopyrimidine [12], 2-amino-5-nitropyrimidines [13], FT-IR spectral study on 4-aminopyrimidine and deuterium substituted 4-aminopyrimidine [13], fluocytosine [14] have been carried out and the vibrational bands have been reported. The C—S stretching frequencies in sulfanyl- aminobenzene have been reported [15]. The nature of substituent at 2- and 6-positions in the pyrimidine ring was found to greatly influence the anti-tubercular activity. Structural study by spectroscopic and quantum chemical methods, have been reported on chloropyrimidine based anti-microbial agents such as 4-cholro2,6-dimethylsulfanyl pyrimidine-5‑carbonitrile and 4-cholro-2- methylsulfanyl-6-(2-thienyl) pyrimidine-5‑carbonitrile which demonstrates activity against M. Tuberculosis [16]. The title molecule has gained attention owing to its structure, functional group and their diverse biological activity. Crystal structure of the title compound [17] has been reported and no other studies have been reported so far. The initiation of cART (combinational antiretroviral therapy) drugs ritonavir, darunavir, and lamivudine/zidovudine did not reduce the cerebellar dysfunctions such as ataxia, dementia and neurocognitive disorders associated with HIV infections. The presence of the amino group in the title molecule has the ability to reduce the cerebellar dysfunction [18]. The physical, biochemical, pharmacological and pharmacokinetic properties of fluorine atom in the title molecules may play an important role in drug design owing to their C—F bond strength, dipole moment, strong electronegetivity and modest lipophilicity [19].

Elucidating the structure activity of DAPF using density functional theory, spectroscopic techniques and molecular docking may pave a way in the development of new HIV protease inhibitor which may reduce the cerebellar dysfunctions. Even though DFT studies have been reported on pyrimidine derivatives, spectral investigation and density functional theory studies of DAPF has not been carried out.

Vibrational spectral analysis of DAPF using quantum chemical computations aided by density functional theory is an efficient method in understanding the various types of bonding and normal modes of vibrations. The complete vibrational assignments for all the vibrational modes have been supported by normal coordinate analysis, force constants and potential energy distributions. A detailed analysis of the intermolecular interactions has been performed using NBO analysis and the intermolecular contacts have been exposed based on the Hirshfeld surface analysis. Antiviral potency of DAPF has been investigated by docking against viral proteins.

The theoretical and experimental calculations have been carried out to probe the structure of DAPF. Also, FT-IR and FT-Raman spectra of DAPF have been described by both experimental and theoretical methods. The antiviral activity has been performed using molecular docking studies, which shows it can irreversibly interact with SARS-CoV-2 main protease.

2. Experimental

To an ethanolic solution of 4,6-diamino-pyrimidine-2- thiol (0.5 g, 3.52 mmol) potassium hydroxide (0.2 g, 3.52 mmol) was added and the mixture was refluxed for 30 min. To this 3.52 mmol of 2-chloro-N-(4-fluoro- phenyl) acetamide was added and the mixture was refluxed for 4 h. The completion of the reaction has been monitored by thin layer chromatography (TLC). Ethanol was evaporated in vacuo and cold water was added and the precipitate formed was filtered and dried to give a crystalline powder. Colourless block-like crystals were obtained by slow evaporation [17].

The room temperature FTIR spectra of the compound was measured in the 4000–400 cm1 region at a resolution of š1 cm1 using a BRUKER IFS-66V vacuum Fourier transform spectrometer equipped with a mercury cadmium telluride (MCT) detector, a KBr beam splitter and globar source. The far IR spectrum was recorded on the same instrument using the polyethylene pellet technique.

The mid-infrared spectrum of the sample has been recorded in the region 4000–400 cm−1 at a resolution of 1 cm−1 using a PerkinElmer Spectrum1 FT-IR spectrophotometer, with the samples in the form of KBr pellets. The FT-Raman spectrum has been recorded using Bruker RFS 27 spectrometer in the region 4000–50 cm−1 with the use of Nd:YAG 1064 nm laser source.

3. Computational details

The equilibrium geometry and the vibrational wavenumbers of the title molecule has been done using Gaussian 09W [20] program package. The geometric optimization has been carried out using DFT calculations at the B3LYP/6-311G++(d,p) level of theory. The natural bonding orbitals (NBO) calculations [21] have been carried out using NBO3.1 program as implemented in the Gaussian 09W package at the DFT/B3LYP level in order to understand the interactions that takes place between the filled and vacant orbitals, which is a measure of delocalization or hyperconjugation. The normal coordinate analysis (NCA) has been performed using MOLVIB 7.0 program [22,23]. The input for the MOLVIB program has been given as suggested by Pulay [24]. Crystal Explorer program 3.1.0 has been employed to carry out the Hirshfeld surface [25] and the associated 2D-fingerprint plots [26]. Molecular docking simulation has been carried out using the Auto Dock 4.2.6 software package and the ligand-protein interactions have been studied [27]. The ligand-protein binding sites have been visualized using PYMOL graphic software [28].

4. Result and discussions

4.1. Optimized geometry

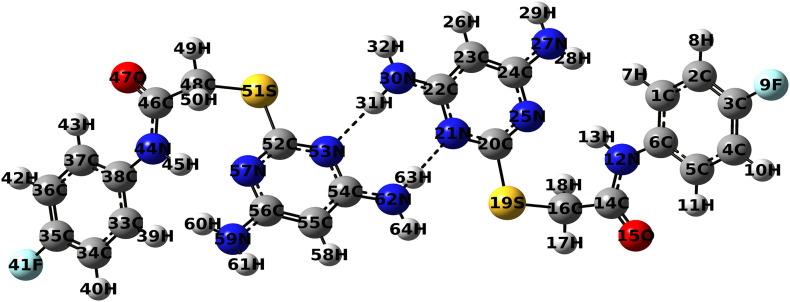

The optimized structural parameters of the monomer and dimer form of the title compound have been performed using GAUSSIAN 09W program package and the optimized structure has been visualized using Gauss View 5.0.9. Geometric optimization has been carried out using B3LYP function and 6-311G++(d,p) basis set. The optimized dimer structure of the DAPF is depicted in Fig. 1 .

Fig. 1.

Optimized molecular structure of DAPF dimer at Becke three Lee–Yang–Parr/6-311++G(d,p) level of theory representing the most stable structure with minimum energy.

The optimized bond length of DAPF is given in Table 1 . The optimized bond angle and dihedral angle of DAPF have been shown in Tables S2 and S3.

Table 1.

Optimized bond length of DAPF monomer and dimer by Becke three Lee–Yang–Parr/6-311G++(d,p) in comparison with X-ray diffraction data.

| Bond length | Monomer |

Dimer |

Δ(d-m) |

Expt. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Calc/Å | Calc/Å | /Å | /Å | |

| C1–C2 | 1.387 | 1.387 | 0.000 | 1.377 |

| C1–C6 | 1.401 | 1.400 | −0.001 | 1.386 |

| C1–H7 | 1.085 | 1.085 | 0.000 | 0.930 |

| C2–C3 | 1.384 | 1.384 | 0.000 | 1.358 |

| C2–H8 | 1.082 | 1.082 | 0.000 | 0.930 |

| C3–C4 | 1.382 | 1.382 | 0.000 | 1.359 |

| C3–F9 | 1.353 | 1.352 | −0.001 | 1.360 |

| C4–C5 | 1.390 | 1.390 | 0.000 | 1.389 |

| C4–H10 | 1.083 | 1.083 | 0.000 | 0.930 |

| C5–C6 | 1.399 | 1.399 | 0.000 | 1.389 |

| C5–H11 | 1.078 | 1.078 | 0.000 | 0.930 |

| C6–N12 | 1.407 | 1.407 | 0.000 | 1.415 |

| N12–H13 | 1.018 | 1.019 | 0.001 | 0.860 |

| N12–C14 | 1.366 | 1.365 | −0.001 | 1.339 |

| C14–O15 | 1.218 | 1.218 | 0.000 | 1.223 |

| C14–C16 | 1.529 | 1.529 | 0.000 | 1.513 |

| C16–H17 | 1.087 | 1.087 | 0.000 | 0.970 |

| C16–H18 | 1.089 | 1.089 | 0.000 | 0.970 |

| C16–S19 | 1.834 | 1.833 | −0.001 | 1.805 |

| S19–C20 | 1.777 | 1.782 | 0.005 | 1.762 |

| C20–N21 | 1.325 | 1.326 | 0.001 | 1.329 |

| C20–N25 | 1.331 | 1.327 | −0.004 | 1.321 |

| N21–C22 | 1.342 | 1.354 | 0.012 | 1.359 |

| C22–C23 | 1.400 | 1.405 | 0.005 | 1.388 |

| C22–N30 | 1.364 | 1.344 | −0.020 | 1.345 |

| C23–C24 | 1.389 | 1.385 | −0.004 | 1.384 |

| C23–H26 | 1.082 | 1.082 | 0.000 | 0.930 |

| C24–N25 | 1.350 | 1.354 | 0.004 | 1.361 |

| C24–N27 | 1.374 | 1.374 | 0.000 | 1.344 |

| N27–H28 | 1.009 | 1.009 | 0.000 | 0.860 |

| N27–H29 | 1.008 | 1.008 | 0.000 | 0.860 |

| N30–H31 | 1.008 | 1.022 | 0.014 | 0.860 |

| N30–H32 | 1.006 | 1.005 | −0.001 | 0.860 |

| Inter and intramolecular distances | ||||

| N21···H63 | – | 2.029 | 2.029 | 2.291 |

| H31···N53 | – | 2.024 | 2.024 | 2.291 |

| H13···N25 | 2.034 | 0.000 | −2.034 | 2.245 |

Å- Angstrom.

Δ(d-m)- Difference in bond length between dimer and monomer molecule.

Expt - Experimental.

The molecular structure and the crystallographic information of DAPF [C12H12FN5OS] have been taken from Cambridge Crystallographic Data Center (CCDC 1529607). The molecular structure of DAPF constitutes a di substituted phenyl ring and a tri substituted pyrimidine ring bridged by thioacetamide moiety. The observed theoretical parameters are in good agreement with the experimental data with certain discrepancies. The C2 – C3, C3 – C4 bond lengths in the phenyl ring are shortened when compared to other C—C bond length and the endoangle C2-C3 – C4(121.56°) has been increased, leading to the distortion from the regular hexagon structure, due to the substitution of the most electronegative fluorine atom. There exist an intramolecular interaction between N12 – H13 of the sulfanylacetamide moiety and the nitrogen atom N25 of the pyrimidine ring resulting in an increase of N12 – H13 bond length (0.01Ǻ). On dimerization, DAPF leads to the formation of two N – H···N hydrogen bonded intermolecular interactions, which adds stability to the system. This hydrogen bonded interaction causes substantial changes with an increase in the N30 – H31 bond length by 0.018 Ǻ and the C22 – N30 – H31 bond angle by 5° when compared with the single molecular structure. This elongation of N – H bond may be due to charge redistributions and orbital interactions [29].

4.2. Natural bond orbital study

DAPF has been subjected to NBO analysis to elucidate the possible intramolecular and intermolecular interactions between the filled and vacant orbital, which is a measure of hyperconjugation or intramolecular delocalization. The stabilization energy E(2) associated with the interaction between the filled orbital i and the vacant orbital j, calculated by the second order perturbation theory [30] have been tabulated (Table 2 ).

Table 2.

Second Order Perturbation Theory Analysis of Fock Matrix of DAPF dimer in NBO basis.

| Donor |

Acceptor |

E(2) |

E(j) – E(i) |

F(i,j) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (i) | (j) | kcal/mol | a.u | a.u |

| n3(F9) | π* (C3–C4) | 18.17 | 0.43 | 0.086 |

| n1(N12) | π* (C5–C 6) | 34.89 | 0.29 | 0.091 |

| n1(N12) | π* (C14–O15) | 63.18 | 0.28 | 0.12 |

| n2(O15) | σ* (N12–C14) | 25.17 | 0.72 | 0.122 |

| n2(O15) | σ* (C5–H11) | 1.1 | 0.73 | 0.026 |

| n2(O15) | σ* (C14–C16) | 21.16 | 0.61 | 0.103 |

| n2(S19) | σ* (C14–C16) | 5.05 | 0.61 | 0.051 |

| n2(S19) | π* (C20–N21) | 25.65 | 0.22 | 0.073 |

| n1(N21) | σ* (C20–N25) | 12.48 | 0.88 | 0.095 |

| n1(N21) | σ* (C22–N30) | 4.03 | 0.84 | 0.053 |

| n1(N25) | σ* (N12–H13) | 7.31 | 0.8 | 0.069 |

| n1(N25) | σ* (C20–N21) | 11.97 | 0.9 | 0.094 |

| n1(N25) | σ* (C23–C24) | 9.01 | 0.92 | 0.083 |

| n1(N27) | π* (C24–N25) | 39.71 | 0.29 | 0.105 |

| n1(N30) | π* (C22–C23) | 58.38 | 0.26 | 0.116 |

| From unit1 to unit 2 | ||||

| n1(N21) | σ* (N62–H63) | 10.54 | 0.8 | 0.084 |

| From unit2 to unit 1 | ||||

| n1(N53) | σ* (N30–H31) | 10.64 | 0.8 | 0.084 |

| Within unit 2 | ||||

| n1(N53) | σ* (C52 - N57) | 12.48 | 0.88 | 0.095 |

| n1(N53) | σ* (C54 - C55) | 9 | 0.88 | 0.081 |

| n1(N53) | σ* (C54 - N62) | 4.02 | 0.84 | 0.053 |

| n1(N62) | π* (C54 - C55) | 59.61 | 0.26 | 0.116 |

E(2) represents energy of the hyperconjugative interaction.

E(j) – E(i) is the energy difference between donor(i) and acceptor(j) NBO orbitals.

F(i,j) is the Fock matrix element between i and j NBO orbitals.

Intramolecular interactions arises due to the hyperconjugation and electron density transfer (EDT) from filed lone pair electrons of the n(Y) of the “Lewis base” Y into the unfilled anti-bond σ*(X – Y) of the “Lewis acid” in X-H···Y have been recorded [31]. The calculated second order perturbation energies (E(2)) in NBO basis confirms the presence of a hydrogen bonded intramolecular interactions n1(O25) → σ*(N12 –– H13) with the stabilization energy of 7.72 kcal/mol. As a result, the length of the N –– H bond involved in intramolecular interaction is lengthened by 0.01 Ǻ respectively. This is well reflected in the optimized molecular geometry. The NBO studies on DAPF monomer and dimer manifests the formation of two strong H-bonded intermolecular interactions between the nitrogen lone pairs n1(N30) and σ* (N62–H63) antibonding orbital. The occupancies and their energies for the interacting NBOs are represented in Table 3 .

Table 3.

Occupancy of the interacting NBOS with their corresponding energies of DAPF monomer and dimer.

| Parameters | Occupancy (e) |

Energy (a.u.) |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Monomer | Dimer | Δocc | Monomer | Dimer | Δ | |

| \n1(N21) | 1.89501 | 1.88287 | −0.01214 | −0.3476 | −0.36193 | −0.01433 |

| σ* (N30 – H31) | 0.00837 | 0.03613 | 0.02776 | 0.40416 | 0.43901 | 0.03485 |

| σ* (C22 – N30) | 0.03048 | 0.02634 | −0.00414 | 0.44296 | 0.48025 | 0.03729 |

| σ* (N21 – C22) | 0.02521 | 0.02732 | 0.00211 | 0.50599 | 0.48755 | −0.01844 |

| n1(N53) | 1.89509 | 1.88303 | −0.01206 | −0.3476 | −0.36232 | −0.01472 |

| aσ*(C54 – C55) | 0.03281 | 0.03087 | −0.00194 | 0.5252 | 0.52014 | −0.00506 |

| aσ* (N62 – H63) | 0.00837 | 0.03583 | 0.02746 | 0.43901 | 0.43876 | −0.00025 |

| aσ* (C54 – N62) | 0.03048 | 0.02626 | −0.00422 | 0.48025 | 0.48147 | 0.00122 |

| σ* (C22 – C23) | 0.03281 | 0.03094 | −0.00187 | 0.5252 | 0.5202 | −0.005 |

| n1(N30) | 1.78013 | 1.71749 | −0.06264 | −0.29972 | −0.26689 | 0.03283 |

Δocc difference in occupancy between dimer and monomer.

Values for monomer are taken from identical NBOs of other unit.

The magnitude of charge transferred from lone pairs of n(N21) → σ* (N62 – H63) and n(N53) → σ* (N30 – H31) has been significantly increased by 0.02746e and 0.02776e upon dimerization. This evinces the weakening of the bond strength and the elongation of bond length. The hyperconjugative interactions between n1(N21) → σ* (N62 – H63) and n1(N53) → σ* (N30–H31) with the stabilization energy of 10.54 kcal/mol quantify the extend of intermolecular interactions.

The effect of rehybridization has a negative impact in N30 – H31 bond. The observed data from Table 4 shows that the s-character of N30 – H31 hybrid orbital has been increased by 4.59% from sp 2.60 to sp 2.16 that leads to the strengthening of N30 – H31bond and its contraction. The composition of hydrogen bonded natural bonding orbitals in terms of natural atomic hybrids shows that the redistribution of natural charges in the N – H bond becomes negative (−0.0177) at H31 resulting in the destabilization of the H-bond. The effect of rehybridization and hyperconjugation result in the contraction and the elongation of the N – H bond. However the effect of rehybridization has been overcome by the hyperconjugative effect resulting in the elongation of N – H bond and a concomitant red shift in N – H stretching frequency.

Table 4.

Composition of H-bonded NBOs in terms of natural atomic hybrids of DAPF monomer and dimer.

| NBO | Monomer | Dimer | ΔNB0 |

|---|---|---|---|

| spn (N30–H31) | sp2.69 | sp2.16 | −0.053 |

| % s-char | 27.040 | 31.630 | 4.590 |

| pol. N30% | 30.170 | 27.190 | −2.980 |

| pol. H31% | 69.830 | 72.810 | 2.980 |

| q(N30)/e | 0.549 | 0.521 | −0.028 |

| q(H31)/e | −0.836 | −0.853 | −0.018 |

| spn (C22 – N30) | sp1.88 | sp1.87 | 0.01 |

| % s-char | 34.650 | 34.720 | 0.070 |

| pol. C22% | 41.250 | 40.780 | −0.470 |

| pol. N30% | 58.750 | 59.220 | 0.470 |

| q(C22)/e | 0.642 | 0.639 | −0.004 |

| q(N30)/e | −0.767 | −0.770 | −0.003 |

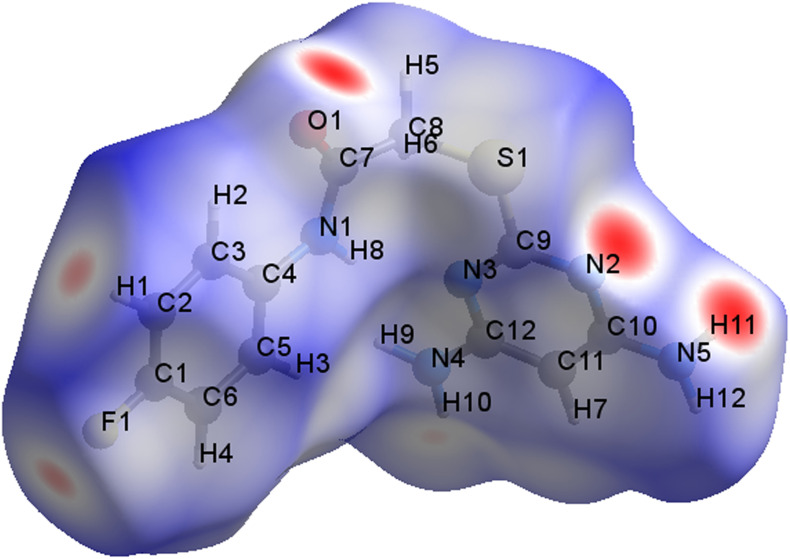

4.3. Hirshfeld surface analysis

Hirshfeld surface analysis provides an insight into the intermolecular interactions in the crystal structure because it is not only connected with molecule itself but it has also contributions from nearest neighbour molecules. Hirshfeld surface analysis of DAPF was carried out using Crystal Explorer 3.1 to investigate the short contacts between atoms with potential to form hydrogen bonds and the quantitative ratios of these interactions besides of the π stacking interactions [[32], [33]]. The Hirshfeld surface of DAPF mapped over dnorm has been depicted in Fig. 2 .

Fig. 2.

Hirshfeld surface of DAPF mapped over dnorm region −0.382 to +1.154 a.u.

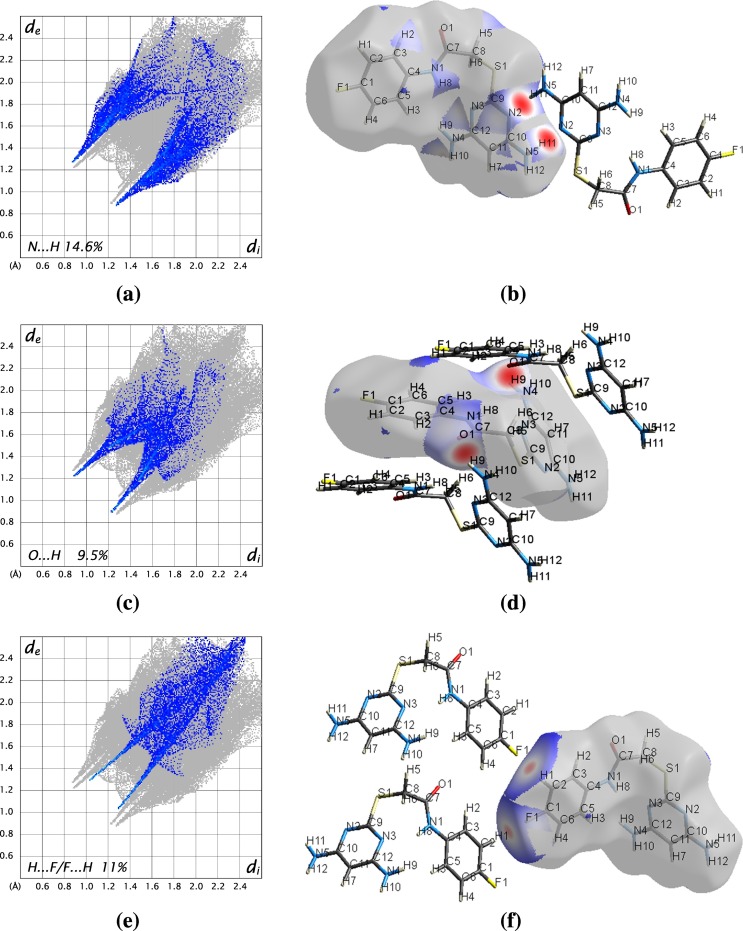

For the 3D Hirshfeld surfaces, 2D view on intermolecular contacts in crystals can be generated by building 2D finger plots [34]. From the fingerprint plot Fig. 3(a), the N···H interactions are represented by a spike in the bottom left of the fingerprint plot, whose contribution is 8% and the counterpart H···N interaction is represented on the bottom right of the fingerprint plot with the contribution of 6.6%, of the total N···H/H···N 14.6%. The most prominent N···H interaction is from the hydrogen of the amino group, with the nitrogen of the neighbouring pyrimidine ring, which is responsible for the distinctive red spot on the dnorm surface as shown in Fig. 3(b). As seen in Fig. 3(c) O···H interaction makes up 9.5% of the Hirshfed surface of the molecule in the structure. The red spot on the dnorm surface is due to the interaction of the carbonyl oxygen of the acetamide group with the proton of the diaminopyrimidine Fig. 3(d). It is noteworthy that H···F contributes 11% on the Hirshfeld surface as seen by two sharp peaks Fig. 3(e), is due to the fluorine atom from the phenyl group interacts with hydrogen atom of the neighbouring phenyl group, which is responsible for the red spot on the dnorm surface as seen in Fig. 3(f). Hirshfeld analysis results shows that prominent interaction has been observed in N···H, than H···F and H···O. Multiple hydrogen bonding interaction, impart enhanced stability to supramolecular structures.

Fig. 3.

2D Fingerprint plot of DAPF mapped over dnorm surface showing the characteristic hydrogen bonded interactions.

(a) 2D Fingerprint plot of DAPF with characteristic N···H interaction.

(b) dnorm surfaces of DAPF displaying N···H interaction.

(c) 2D Fingerprint plot of DAPF with characteristic O···H interaction.

(d) dnorm surfaces of DAPF displaying O···H interaction.

(e) Fingerprint plot of DAPF with characteristic H ···F interaction.

(f) dnorm surfaces of DAPF displaying H ···F interaction.

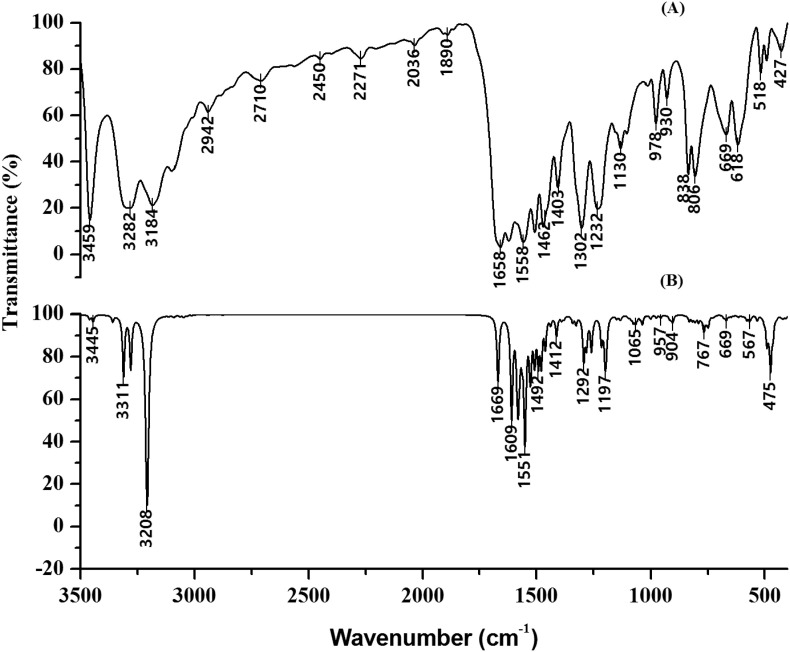

4.4. Vibrational spectral analysis

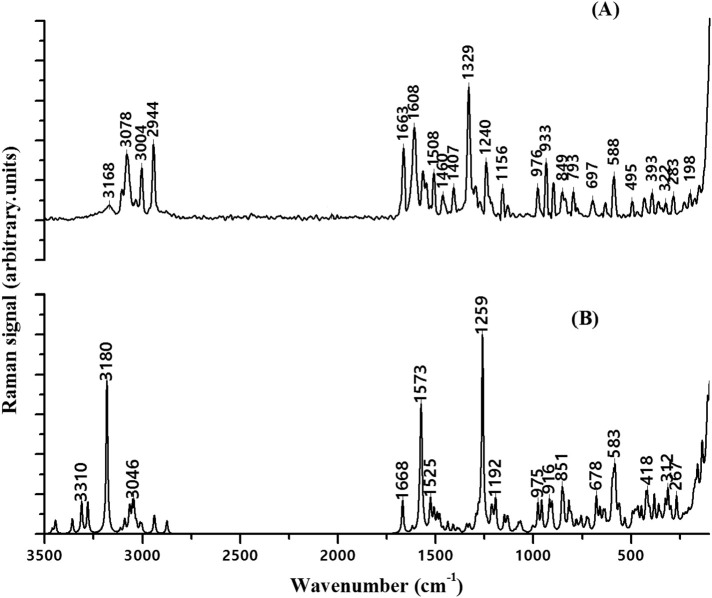

The dimer molecule of DAPF consists of 64 atoms, which undergo 186 vibrational modes. The assignments of the fundamental modes of vibrations have been made based on the normal coordinate analysis following the force field calculation with the ab initio method used for the geometry optimization of the dimer molecule. Multiple scaling factors have been employed for scaling, and those are available in supplementary Table S3. The vibrational assignments have been carried out on the basis of the characteristic group vibrations of phenyl ring, acetamide group, methylene group, pyrimidine ring and amine group. The experimental and calculated wave numbers of DAPF along with their normal modes and their corresponding potential energy distribution (PED) are presented in Table 5 . Experimental and simulated IR and Raman spectra of DAPF have been shown in Fig. 4, Fig. 5 .

Table 5.

Vibrational assignments of DAPF dimer by normal coordinate analysis.

| νIR | νRaman | ν(scaled) | IR(I) | Raman(I) | Assignments of modes with PED≥10% |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3459s | 3549 | 29 | 70 | νasNH(Am3)(99) | |

| 3282s | 3279 | 371 | 380 | νNH(Amd)(99) | |

| 3184s | 3208 | 2993 | 2 | νssNH (Am2) (32)+νssNH(Am4) (32)+νasNH(Am3) (16),νasNH(Am4) (16) | |

| 3102w | 3112 | 6 | 44 | νCH (99) | |

| 3098s | 3078s | 3093 | 6 | 43 | νCH(99) |

| 3035w | 3045 | 6 | 162 | νCH (99) | |

| 3004s | 3014 | 5 | 80 | νCH (99) | |

| 2943m | 3005 | 0 | 71 | νMetip(95) | |

| 2944s | 2942 | 4 | 110 | νssMet(M1)(95) | |

| 1670 | 238 | 48 | νCO(67)+βCNH(Amdr1) (15) | ||

| 1658s | 1663s | 1668 | 266 | 36 | νCO(72) + βCNH(Amdr3) (11) |

| 1608s | 1619 | 1 | 13 | γNH(Am2) (42)+γNH(Am4) (42) | |

| 1602s | 1609 | 848 | 0 | γNH(Am2) (35)+γNH(Am4) (31)+νCNr2 (11) | |

| 1576m | 1572 | 28 | 101 | νCC(51)+βCCH(10)+βCNH(10) | |

| 1558s | 1564 | 150 | 13 | νCC(26)+νCN(21)+ γNH(Am2)((17) | |

| 1508s | 1544s | 1510 | 1183 | 2 | νCC(33)+νCN(19)+βCCH(10) |

| 1507 | 148 | 27 | νCN (r2) (29)+νCCr3 (29) | ||

| 1470s | 1508m | 1492 | 176 | 21 | νCC(31)+νCN(r2)((30) |

| 1479 | 305 | 33 | βCCH(r1)((54)+νCC(r1)((31) | ||

| 1460m | 1412 | 323 | 31 | βCCH(r1)((51)+νCC(r2) (34) | |

| 1403s | 1410 | 116 | 1 | νCN(r2)((33)+νCNar(30) | |

| 1406m | 1341 | 13 | 14 | νCN(r4)((35)+νCNar(r2)(28) | |

| 1302s | 1329s | 1326 | 41 | 13 | γMetM2 (90) |

| 1295 | 52 | 13 | γMetM1(86) | ||

| 1294w | 1271 | 25 | 6 | βCCH(r1)(80) | |

| 1232m | 1240m | 1237 | 6 | 10 | βCCH1(r3)(82) |

| 1190 | 4 | 7 | νCN(r2) (51)+νCC(11)+ γCNH2 (10) | ||

| 1155w | 1148 | 40 | 15 | νCN(r4) (20)+νCC(20)+Rtrd(r3 (17)+βCCH(r2) (15)+βCCH(r2) (15) | |

| 1130m | 1134 | 22 | 21 | βCCH(r1) (65)+νCC(19)+νCF(r1) (11) | |

| 1129 | 19 | 12 | βCCH(r3) (66)+νCC(r3) (16)+ νCF(r3)(8) | ||

| 1013m | 1129w | 1035 | 15 | 13 | ωCS(M2) (29)+2ωCC3(M1)((28)+νCC(10) |

| 976 | 56 | 0 | ρCNH(Am2)((27)+ ρCNH(Am1) (15)+ρ(Am4) (13)+νCC(M1) (20) | ||

| 976m | 957 | 18 | 29 | νCNar4 (45)+Rtrdr4 (37) | |

| 947 | 20 | 30 | νCNr2 (43)+Rtrdr2(42)ρ | ||

| 930w | 933m | 930 | 0 | 0 | ωCH(r1) (89) |

| 904 | 3 | 3 | νCC(r3) (34)+βCN3 (15)+βCN(Amd2) (14)+νCN(r1) (10) | ||

| 896m | 852 | 42 | 23 | νCS(M1) (24)+Rasd2' (20)+νCN(r2) (19)+νCC(r1) (15) | |

| 838m | 849w | 832 | 3 | 30 | νCC(r1) (30)+ ρMet(M1)((20)+βCN(Amd) (11) |

| 806m | 803 | 39 | 1 | ωCH(r1)(73) | |

| 791 | 17 | 7 | ωCH(r1)((46)+ ρMet(M1)((23) | ||

| 793w | 720 | 40 | 0 | 2ωCH(r1)(81) | |

| 669m | 698w | 669 | 7 | 7 | Rpuk(r2) (27)+ωCN(16)+ωCS(13) |

| 636 | 34 | 1 | 2ωMet(M1)) (32)+2ωCN(M1)(23) | ||

| 618m | 632w | 622 | 0 | 5 | Rad(r1) (52)+Rad'(r1) (22) |

| 591 | 4 | 2 | Rad'(r3) (20)+ Rad (r3) (19) | ||

| 518w | 588m | 533 | 3 | 17 | ωCS(M2) (31)+ Rad2'(M2)(15)+ νCN (r4) (10) |

| 494 | 32 | 5 | ω(Amd2) (20)+ νCS(M2)(19)+ Rad'(M2) (13) | ||

| 495w | 449 | 1 | 5 | βCN(r2) (18)+βNNr2 (16)+Rad(r2) (14) | |

| 432w | 402 | 10 | 7 | βNCC(M2) (30)+ τCC(15)+ Rad'(r2)(11) | |

| 393w | 381 | 1 | 0 | Rayt(r3) (56)+ ωCH(M2) (21)+ Rat1'(r3) (15) | |

| 362w | 326 | 5 | 3 | Rpuk(r4) (15)+ωCF(M2) (12) | |

| 322w | 298 | 7 | 4 | βNN(r2) (37)+βCN(r2) (16) | |

| 284w | 234 | 7 | 2 | βCN(r1) (32)+βCN(r3) (21)+βCF(r3) (11) | |

| 229w | 2 | 1 | τSCM2 (21)+ Rayt(r4) (19)+τCC(M2) (17) |

νIR- Frequency of Infrared.

νRaman- Frequency of Raman.

νCal –Calculated frequency.

aIIR- Infrared intensity.

bIRaman- Raman intensity.

PED- Potential energy distribution.

s: strong; m: medium; w:weak.

Symbols used: ν -stretching; νas - asymmetric stretching; νas - symmetric stretching; β – bending; ω – wagging; γ- inplane bending; γ’- outplane bending; ρ- rocking; τ- torsion; Rad- asymmetric deformation; Rad’- asymmetric deformation out of plane; Rpuk- puckering; Amd - amide; Am -amine; ip – inplane stretching; Met- methyl; M1-moleculeI; M2-moleculeII; r1- ring1; r2- ring2; r3- ring3; r4- ring4.

Fig. 4.

FT-IR spectrum of DAPF. (A) Experimental Fourier transform-Infrared spectra of DAPF revealing the characteristics Infrared bands in the region 4000–0 cm−1. (B) Simulated Fourier transform-Infrared spectra of DAPF revealing the characteristics Infrared bands in the region 4000 cm−1 to 400 cm−1.

Fig. 5.

FT-Raman spectrum of DAPF. (a) Experimental Fourier transform-Raman spectra of DAPF revealing the characteristics Raman bands in the region 4000 cm−1 to 0 cm−1. (b) Simulated Fourier transform-Raman spectra of DAPF revealing the characteristics Raman bands in the region 4000 cm−1 to 0 cm−1.

4.4.1. Phenyl ring vibrations

The vibrations of the disubstituted phenyl ring have been adopted using Wilson's scheme [35]. The C – H stretching frequencies of the disubstituted benzene are expected to be in the region 3000 – 3100 cm – 1 [36]. The selection rules allowed for disubstituted benzene for C – H stretching vibrations are 2, 7b, 20a and 20b. The bands observed at 3102 cm – 1 with medium intensity and the band observed at 3078 cm – 1 with strong intensity in Raman spectra have been assigned to mode 20b and 2 respectively. The C – H inplane bending vibrations falls in the region 1300 to 1100 cm – 1 and is characterized by the normal modes 3, 9a, 15, 18a, 18b. The band with weak intensity observed at 1148 cm – 1 and a strong band at 1130 cm – 1 in IR have been assigned to mode 18b. The band at 1240cm – 1 in Raman spectra with weak intensity is assigned to mode 3. The out of plane bending vibrations of the para disubstituted phenyl ring exhibits in the region 1000 – 675 and the allowed selection rules are 10a, 10b, 17a, 17b. The bands observed at 836, 805 cm – 1 in IR spectra and Raman bands at 894 cm – 1, 933 cm – 1 have been assigned to modes 10b and 10a respectively.

In the case of disubstituted benzene derivatives the selection rule allows five normal modes for C – C stretching vibrations. The modes are 8a, 8b, 19a, 19b and 14. In Raman spectrum the vibration mode 8a has been observed at 1563 cm – 1 and 1544 cm – 1 and in simulated spectrum it has been observed at 1572 cm – 1 and 1545 cm – 1. The ring mode appears at 1470 cm – 1 in the IR spectrum and the corresponding calculated wavenumber is 1492 cm – 1. The counterpart Raman band has been observed at 1463 cm – 1 and the theoretical band at 1479 cm – 1. The radial skeletal mode 6a of the phenyl ring has been observed at 808 cm – 1 in IR and Raman. The simulated IR band observed at 805 cm – 1 and the Raman band at 795 cm – 1 has been assigned to mode 6a. The outofplane skeletal mode 4 has been observed at 674 cm – 1 in IR spectrum and at 670 cm – 1 in simulated IR spectrum.

4.4.2. Amide group vibrations

Amides are of fundamental chemical interest owing to their conjugation between lone pair electrons in the Nitrogen and the carbonyl bond results in distinct physical and chemical properties [37]. Secondary amides are probably the most important as they are the backbone of every protein molecule. Secondary amide contains only one N—H stretching band in the infrared spectrum. This band appears between 3370 and 3500 cm−1 [38]. Therefore, band observed at 3282 cm−1 in IR is assigned to the N—H stretching. The down shift in N – H stretching frequency validates the spectral evidence of the N – H···N intramolecular hydrogen bond formation. The strength of N – H···N bond has been well reflected by an increase in the bond length (0.001 Å). Also, the shift has been evinced by the intramolecular charge transfer interaction between N25 → N12 – H13 in NBO basis with the stabilization energy 7.31 kcal/mol. An interesting feature of the amide group is the amide I band and is known as the C O stretching mode. In fluorophenylacetamide the amide I band arises due to the delocalization of the nitrogen lone pair electrons and is observed as a strong intense band at 1658 cm−1 in IR. Normal Coordinate analysis of DAPF shows amide I band has been coupled with amide II and amide III bands. The amide II band known as N – H inplane bending has been observed as an intense peak in the IR spectra at 1515 cm−1. The Raman counterpart is observed at 1519 cm−1. The C O out of plane bending known as amide VI band has been observed at 518 cm−1 in IR and at 525 cm−1 in Raman.

4.4.3. Methylene vibrations

The asymmetric and the symmetric vibrations of the methylene group normally occur in the region 3100 – 2900 cm−1 [39]. The presence of the neighbouring acetamide moiety and the sulphur lone pair affects the spectral behaviour of the sp3 methylene group. The occurrence of the adjacent sulphur atom can shift the position and the intensity of the CH stretching and bending vibrations. The hyperconjugative interactions between the s lone pair and σ*(C – H), lowers the wavenumber and the weakening of C – H bonds. NBO result substantiates the above fact as seen from the hyperconjugative interaction S19 → C16 – H18 with the stabilization energy of 1.72 kJ/mol. The IR band observed at 2942 cm−1with medium intensity is assigned to CH2 symmetric and asymmetric stretching.

4.4.4. Pyrimidine ring vibrations

Pyrimidine ring vibrations have been characterized by the C – N stretching vibration, C – C stretching and bending vibrations. In pyrimidine, quadrant stretch bands occur at 1590 – 1520 cm−1 [40,41] and the semicircle bands occur in the region 1480–1375 cm-1. These bands can be viewed both in IR spectra as well as Raman spectra [42,43]. The spectrum of DAPF shows the band with strong intensity at 1558 cm-1in IR and the band at 1544 cm−1 in Raman with medium intensity have been assigned to quadrant stretching mode. Semicircle stretching vibrations has been observed at 1507 cm−1 in IR and Raman spectra. Quadrant inplane bending mode has been observed at 632 cm−1 in Raman spectra and the theoretical band at 636 cm−1.

4.4.5. Amine vibrations

In primary amines, vibrational frequencies have been characterized by NH2 antisymmetric stretching, NH2 symmetric stretching, NH2 scissoring, NH2 wagging, C – N stretching and CCN bending. Strong absorption in the range 3548–3459 cm-1 has been marked as NH2 antisymmetric stretching in the IR spectra [44]. In DAPF, the antisymmetric N – H stretching mode has been observed at 3459 cm−1 as an intense band in the IR spectrum. The dimer molecule of DAPF has been bonded by two strong N – H···N bonds. In case of primary aromatic amines the symmetric stretching is expected in the region 3422–3360 cm−1 [45]. The band observed at 3183 cm−1 in IR spectra has been assigned to N – H symmetric stretching. The red shift in wavenumber (~180 cm-1) shows the spectral evidence for the formation of N – H···N intermolecular interactions. This has been validated from the results of optimized geometry as seen with an increase in the N30 – H31 bond length by 0.018 Ǻ and the C22 – N30 – H31 bond angle by 5° over the isolated molecule. Also, the down shift in stretching frequency has been substantiated by the second order perturbation energy that takes place between n1(N53) → σ* (N30–H31) with the stabilization energy of 10.54 kcal/mol and the occupancy of the interacting NBOs. These hydrogen bonded interactions restrain protein molecules to their native configurations and an important role in inhibiting the gelling of sickle–cell deoxyhemoglobin. Also, intermolecular N···H – N hydrogen bonding plays an important role in the stability of protein structure [46]. The NH2 scissoring mode in aryl amine is in the region of 1638 – 1602 cm−1 [47,48]. The NH2 scissoring mode known as the symmetric deformation mode is assigned to the band at 1622 cm−1in the IR while the respective Raman band is observed at 1608 cm−1. Raman bands with weak intensity at 698 cm−1and the widened IR band at 669 cm-1contributes to the NH2 wagging mode. The band observed with medium intensity at 1446 cm−1and 1406 cm−1have been assigned to the C–N stretching vibration in IR and Raman respectively.

4.5. Drug likeness of DAPF

According to the rule of thumb, orally absorbed drugs tend to obey Lipinski's rule of five. The rule of five was derived from an analysis of compounds from the World Drugs Index database aimed at identifying features that have been important in making a drug orally active. It has been found that the factors concerned involved numbers that are multiples of five: a molecular weight less than 500; no more than 5 hydrogen bond donor (HBD) groups; no more than 10 hydrogen bond acceptor groups; a calculated log P value less than +5 [[49], [50], [51], [52], [53], [54]]. DAPF has been passed through Lipinski's rule of five (Table 6 ) to overcome drug-likeness filter.

Table 6.

Drug likeness properties of DAPF.

| Lipinski's rule | Drug likeness properties of DAPF | Lipinski's rule satisfied (yes/no) |

|---|---|---|

| Molecular weight (≤500 g/mol) |

293.32 g/mol | Yes |

| Number of HB acceptors (≤10) | 4 | Yes |

| Number of HB donors (≤5) | 3 | Yes |

| Lipophilicity log P (≤5) | 1.74 | Yes |

| Molar refractivity (40 to130) | 76 | Yes |

4.6. ADMET property analysis

There is an overall of 26 constraints in ADMET statistics, which has been taken from the full text of peer-reviewed scientific journals through weekly PubMed and Google Scholar searches from 2002 to 2011 [55]. ADMET (Absorption, Distribution, Metabolism, Excretion and Toxicity) results show that DAPF (+) in human intestinal absorption and blood-brain barrier permeability, which suggests that the molecule is well absorbed in the human body (Table 7 ). Inhibition and initiation of P-glycoprotein have been described as the causes of drug-drug interactions. [56]. It has been observed that DAPF has P-glycoprotein non-inhibitor, which shows the noninteracting activity of DAPF with other drugs. ADMET data show DAPF is in permissible limit [55,57]. Organic cation transporters are accountable for drug absorption and disposition in the kidney, liver, and intestine [58]. ADMET result of DAPF shows that it has been a non-inhibitor of renal organic cation transporter. The human cytochromes P450 (CYPs) are responsible for about 90% oxidative metabolic reactions. Inhibition of CYP enzymes will lead to inductive or inhibitory failure of drug metabolism [59]. A non-inhibitor and non-Substrate property of DAPF supports the fact it is safe to the human liver. The Ames test is employed to test the mutagenic activity of chemical compounds. It is usually carried out to test bacteria and viruses to whether a given chemical can cause cancer [60,61]. ADMET result of DAPF is shown in Table 7.

Table 7.

Absorption, distribution, metabolism, excretion, toxicity (ADMET) properties of DAPF.

| Model | Result | Probability |

|---|---|---|

| Absorption | ||

| Blood-brain barrier | BBB+ | 0.9789 |

| Human intestinal absorption | HIA+ | 0.8629 |

| Caco-2 permeability | Caco2- | 0.5649 |

| P-glycoprotein substrate | Non-substrate | 0.7566 |

| P-glycoprotein inhibitor | Non-inhibitor | 0.6319 |

| Non-inhibitor | 0.9546 | |

| Renal organic cation transporter | Non-inhibitor | 0.7981 |

| Distribution | ||

| Subcellular localization | Mitochondria | 0.4296 |

| Metabolism | ||

| CYP450 2C9 substrate | Non-substrate | 0.8784 |

| CYP450 2D6 substrate | Non-substrate | 0.8302 |

| CYP450 3A4 substrate | Non-substrate | 0.6196 |

| CYP450 1A2 inhibitor | Inhibitor | 0.7502 |

| CYP450 2C9 inhibitor | Inhibitor | 0.5890 |

| CYP450 2D6 inhibitor | Non-inhibitor | 0.6972 |

| CYP450 2C19 inhibitor | Inhibitor | 0.6940 |

| CYP450 3A4 inhibitor | Inhibitor | 0.6666 |

| CYP Inhibitory promiscuity | High CYP Inhibitory Promiscuity | 0.8737 |

| Excretion | ||

| Toxicity | ||

| Human ether-a-go-go-related gene inhibition | Weak inhibitor | 0.9943 |

| Non-inhibitor | 0.7087 | |

| AMES toxicity | Non AMES toxic | 0.6974 |

| Carcinogens | Non-carcinogens | 0.8358 |

| Fish toxicity | Low FHMT | 0.8744 |

| Tetrahymena pyriformis toxicity | High TPT | 0.7894 |

| Honey bee toxicity | Low HBT | 0.8417 |

| Biodegradation | Not ready biodegradable | 1.0000 |

| Acute oral toxicity | III | 0.5613 |

| Carcinogenicity (three-class) | Non-required | 0.4045 |

ADMET result shows DAPF has been non-ames toxic and non-carcinogenic. Human Ether-à-go-go-Related Gene (hERG) is a gene delicate to drug binding [62]. ADMET results shows DAPF have been weak inhibitor and non-inhibitor of hERG inhibition (predictor I and II). That means the DAPF molecules will well bind with SARS-CoV-2 main protease [63]. Analyzing the ADMET properties, together with their attributes and prediction, has given an idea about the pharmacokinetic properties of DAPF.

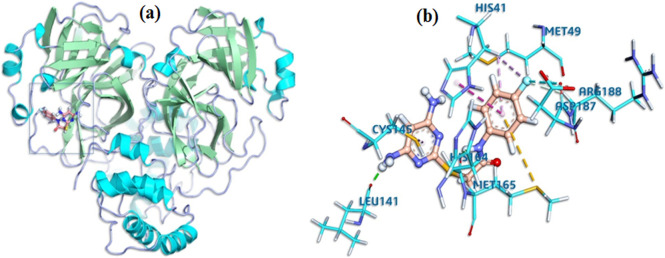

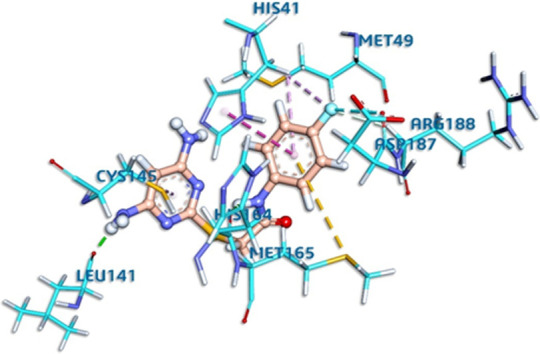

4.7. Docking study of DAPF with SARS-CoV-2 main protease

4.7.1. In silico calculation

Molecular docking has been used to acquire binding modes and binding affinities of DAPF. Binding mode and affinity to SARS-CoV-2 main protease are essential for insilico drug design [[64], [65], [66], [67], [68]]. The protein structure of SARS-COV-2 has been retrieved from protein data bank (PDB id: 5r80). The protein (SARS-COV-2) and ligands (DAPF) structures have been modified by Autodock Tools [69]. The chains of main protease have been modified by removing water and bound ligand. Missing amino acids have been checked and polar hydrogens have been added to the protein structure. Center Grid box x:5.108, y:18.9177, z:-18.1863 and number of points in x,y,z dimensions are considered as 30x30x30 Å3 respectively and grid spacing has been taken as 0.3750 Å. Ligand has been prepared by adding Gasteiger charges, detecting root and choosing torsions from the torsion tree of Autodock Tools panel [70]. Docking procedure has been performed by using the Lamarckian genetic algorithm [71] and the results have been tabulated in Table 8 .

Table 8.

Bond distances of DAPF and types of bond with SARS-CoV-2 main protease.

| Molecule name DAPF |

Distance (Å) | Bond category | Bond type |

|---|---|---|---|

| DAPF:H - A:LEU141:O | 1.77679 | Hydrogen bond | Conventional hydrogen bond |

| A:ARG188:HA - :DAPF:F | 2.62388 | Hydrogen bond; Halogen |

Carbon hydrogen bond; Halogen (fluorine) |

| DAPF:H - A:HIS164:O | 2.9894 | Hydrogen bond | Conventional hydrogen bond |

| A:ASP187:O - :DAPF:F | 3.16325 | Halogen | Halogen (fluorine) |

| DAPF:F - A:MET49 | 4.28188 | Hydrophobic | Alkyl |

| DAPF - A:MET49 | 4.65914 | Hydrophobic | Pi-alkyl |

| DAPF - A:CYS145 | 4.69418 | Hydrophobic | Pi-alkyl |

| A:HIS41 - :DAPF | 4.74499 | Hydrophobic | Pi-Pi stacked |

| A:MET165:SD - :DAPF | 5.50755 | Other | Pi-sulphur |

DAPF bound to the active site of main protease with good complementarity (Fig. 6 ) and formed three hydrogen bonds and four hydrophobic bonds with the mainprotease. The binding energy of the nonbonding interaction is −8.7 kcal/mol. All these results present a clear view that DAPF can irreversibly interact with main protease. The catalytic dyad composed of Histidine 41 and Cysteine 145 is a set of amino acids that can be found in the active site of most SARS-CoV-2 main proteases, plays an essential role in drug binding [72]. DAPF bound both to Histidine 41 and Cysteine 145 (Fig. 6 and Table 8) claims to be a good antiviral drug.

Fig. 6.

Comprehensive perception of main protease and DAPF after docking, (a) secondary structure of SARS-CoV-2 mainprotease represented by ribbon and DAPF represented is by ball and stick model (b) interactions of DAPF with SARS-CoV-2 main protease amino acids. Bonds are in dots. DAPF (orange) surrounding amino acids (sky blue) are in three letters code.

5. Conclusion

The compound DAPF has been characterized by FT-IR, FT-Raman at B3LYP/6-311++G(d,p) level using DFT calculations and the complete vibrational analysis has been carried out in order to elucidate the structure activity relationship. The presence of the intermolecular and intramolecular hydrogen bonds has been analyzed using NBO analysis. The transfer of electrons from the lone pair nitrogen to the anti-bonding orbital of N—H bond evinces the formation of two hydrogen bonds that brings about most interesting biological properties. The occurrence of N–H···N intermolecular interactions and the conspicuous shifting in the wavenumber have been authenticated by the increase in N—H bond length and an increase in the electron density in the antibonding orbitals. Also, intermolecular N – H···N hydrogen bonding plays an important role in the stability of protein structure. Hirshfeld surfaces and the 2D fingerprint plot confirms the presence of the intermolecular contacts N – H···N, C – H···O, C – H···F and their quantitative contributions, impart stability to the system. Drug likeness and ADMET property analysis gives an idea about the pharmacokinetic properties of the title molecule. The binding energy −8.7 kcal/mol of the nonbonding interaction presents a clear view that DAPF can irreversibly interact with SARS-CoV-2 protease.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Jenepha Mary: Conceptualization, Data Curation, Investigation, Software, writing and Validation. Mohd Usman Mohd Siddique, Venkatesan Jayaprakash: Provision of Sample. Sayantan Pradhan: Writing and Data Curation. James. C: Supervision.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Footnotes

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.saa.2020.118825.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

Supplementary tables

References

- 1.Mohd R., Asif H., Mohammad S., Ravinesh M., Afzal H., Obaid A. Design and synthesis of pyrimidine molecules endowed with thiazolidin-4-one as new anticancer agents. Eur. J.Med.Chem. 2014;83:630–645. doi: 10.1021/jm0009540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hester R.E., Girling R.B. Royal Society of Chemistry; London, UK: 1991. Spectroscopy of Biological Molecules. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Diwakar R., Wenmin C., Ye T., Xuwang C., Peng Z., Clercq D., Pannecouque E., Xinyong L. Design, synthesis and biological evaluation of 3-benzyloxy-linked pyrimidinylphenylamine derivatives as potent HIV-1 NNRTIs. Bioorg. & Med. Chem. 2013;21:7398–7405. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2013.09.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wang Q.-Y., Patel S.J., Vangrevelinghe E., Xu H.Y., Rao R., Heudi O., Ma N.L., Poh M.K., Phong W.Y., Keller T.H., Jacoby E., Vasudevan S.G. Antimicrob. Agents And Chemother. 2009, May:1823–1831. doi: 10.1128/aac.01148-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Philp Joanne, Lawhorn Brian G., Graves Alan P. 4,6-Diaminopyrimidines as highly preferred troponin I-interacting kinase (TNNI3K) J. Med. Chem. 2018;61:3076–3088. doi: 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.8b00125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gadhachanda Venkat R., et al. 4-Aminopyrimidines as novel HIV-1 inhibitors. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2007;17:260–265. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2006.09.047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Aparna E.P., Devaky K.S. Advances in the solid-phase synthesis of pyrimidine derivatives. ACS Comb. Sci. 2019;21(2):35–68. doi: 10.1021/acscombsci.8b00172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Turck A., Ple N., Mongin F., Queguiner G. Advances in the directed metallation of azines and diazines (pyridines, pyrimidines, pyrazines, pyridazines, quinolines, benzodiazines and carbolines), Part. 2:metallation of pyrimidines,pyrazines, pyridazines and benzodiazines. Tetrahedron. 2001;57(21):4489–4505. doi: 10.1016/S0040-4020(01)00225-3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Schomaker J.M., Delia T.J. Arylation of halogenated pyrimidines via a Suzuki coupling reaction. J. Org. Chem. 2001;66(21):7125–7128. doi: 10.1021/jo010573+. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Krishnakumar V., John Xavier R. Molecular and vibrational structure of 2-mercapto pyrimidine and 2,4-diamino-6-hydroxy-5-nitroso pyrimidine: FT-IR, FT-Raman and quantum chemical calculations. Spectrochim. ActaA. 2006;63:454–463. doi: 10.1016/j.saa.2005.05.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gunasekaran S., Ponnambalam U., Muthu S. Vibrational and normal coordinate analysis of pyrazinamide. Asain Journal of Chemistry. 2004;16(3):1513–1518. [Google Scholar]

- 12.McCarthy W.J., Lapinski L., Novak M.J., Adamovicz L. Out-of-plane vibrations of NH2 in 2-aminopyrimidine and formamide. J. Chem. Phys. 1998;108(24):10116–10128. doi: 10.1063/1.476471. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Politzer P., Kirschenheuter G.P., Miller R.S. Computational study of 2-aminopyrimidine, 2-amino-5-nitropyrimidine, and the corresponding S,S-dimethyl-N-sulfilimines. J. Phys. Chem. 1988;92:1436. doi: 10.1021/j100317a015. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14.S. Seshadri, S. Gunasekaran, S. Muthu, S. Kumaresan, R. Arunbalaji, Vibrational spectroscopy investigation using ab initio and density functional theory on flucytosine, J. Raman Spectrosc. 38 (2007)1523–1531. doi: 10.1002/jrs.1808. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 15.Muthu S., Uma Maheswari J. Quantum mechanical study and spectroscopic (FT-IR, FT-Raman, 13C, 1H, UV) study, first order hyperpolarizability, NBO analysis, HOMO and LUMO analysis of 4-[(4-aminobenzene) sulfonyl] aniline by ab initio HF and density functional method. Spectrochim. ActaA. 2012;92:154–163. doi: 10.1016/j.saa.2012.02.056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Khan A.Y., Kalashetti M.B., Belavagi N.S., Deshapa-nde N., Khazi I.A.M. Synthesis, characterization and biological evaluation of novel thienopyrimidine and triazolothienopyrimidine derivatives as anti-tubercular and antibacterial agents. Med. Chem. Res. 2014;23:3235–3243. doi: 10.1007/s00044-013-0900-1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Subasri, Timiri Ajay Kumar, Barij Nayan Sinha, Venkatesan Jayaprakash, Vijayan Viswanathan and Devadasan Velmurugana. Crystal Structures of N-(4-chloro-phen-yl)-2-[(4,6-di-amino-pyrimidin-2-yl)sulfan-yl]acetamide and N-(3-chloro-phen-yl)-2-[(4,6-di-amino-pyrimidin-2-yl)sulfan-yl]acetamide, Acta Cryst E 73 (2017) 467–471. doi: 10.1107/s2056989017003243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 18.Hoyera Carolin, Alonsoa Angelika, Schlotter-Weigelb Beate, Plattena Michael, Fatara Marc. HIV-associated cerebellar dysfunction and improvement with aminopyridine therapy. Case Rep Neurol. 2017;9:121–126. doi: 10.1159/000475544. 10.1159%2F000475544. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Johnson B.M., Shu Y.Z., Zhuo X., Meanwell N.A. Metabolic and pharmaceutical aspects of fluorinated compounds. J. Med. Chem. 2020 doi: 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.9b01877. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Frisch M.J., Trucks G.W., Schlegel H.B., Scuseria G.E., Robb M.A., Cheeseman J.R., Scalmani G., Barone V., Petersson G.A., Nakatsuji H., Li X., Caricato M., Marenich A., Bloino J., Janesko B.G., Gomperts R., Mennucci B., Hratchian H.P., Ortiz J.V., Izmaylov A.F., Sonnenberg J.L., Williams-Young D., Ding F., Lipparini F., Egidi F., Goings J., Peng B., Petrone A., Henderson T., Ranasinghe D., Zakrzewski V.G., Gao J., Rega N., Zheng G., Liang W., Hada M., Ehara M., Toyota K., Fukuda R., Hasegawa J., Ishida M., Nakajima T., Honda Y., Kitao O., Nakai H., Vreven T., Throssell K., Montgomery J.A., Jr., Peralta J.E., Ogliaro F., Bearpark M., Heyd J.J., Brothers E., Kudin K.N., Staroverov V.N., Keith T., Kobayashi R., Normand J., Raghavachari K., Rendell A., Burant J.C., Iyengar S.S., Tomasi J., Cossi M., Millam J.M., Klene M., Adamo C., Cammi R., Ochterski J.W., Martin R.L., Morokuma K., Farkas O., Foresman J.B., Fox D.J. Gaussian, Inc.; Wallingford CT: 2009. Gaussian 09. Revision C.01. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Glendening E.D., Reed A.E., Carpenter J.E., Weinhold F. University of Wisconsin; Madison: 1998. NBO Version 3.1, TCI. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sundius T. Scaling of ab initio force fields by MOLVIB. Vib. Spectrosc. 2002;29:89–95. doi: 10.1016/S0924-2031(01)00189-8. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sundius T. Molvib - a flexible program for force field calculations. J. Mol. Struct. 1990;218:321–326. doi: 10.1016/0022-2860(90)80287-T. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pulay P., Fogarasi G., Pongor G., Boggs J.E., Vargha A. Combination of theoretical ab initio and experimental information to obtain reliable harmonic force constants. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1983;105:7037. doi: 10.1021/ja00362a005. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wolff S.K., Grimwood D.J., McKinnon J.J., Turner M.J., Jayatilaka D., Spackman M.A. University of Western Australia; 2012. CrystalExplorer (Version 3.0), [prod.] [Google Scholar]

- 26.McKinnon J.J., Jayatilaka D., Spackman M.A. Towards quantitative analysis of intermolecular interactions with Hirshfeld surfaces. Chem. Commun. 2007:3814–3816. doi: 10.1039/b704980c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Morris G.M., Goodsell D.S., Halliday R.S., Huey R., Hart W.E., Belew R.K., Olson A.J. Automated docking using a lamarckian genetic algorithm and empirical binding free energy function. J. Comput. Chem. 1998;19:1639–1662. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1096-987X(19981115)19:14%3C1639. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 28.The PYMOL Molecular Graphics System, LLC, Schrodinger. 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Li X., Liu L., Schlegel H. Bernhard, on the physical origin of blue-shifted hydrogen bonds. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2002;124:9639–9647. doi: 10.1021/ja020213j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Glendening E.D., Reed A.E., Carpenter J.E., Weinhold F. Gaussian Inc.; Pittsburgh: 2003. NBO Version 3.1. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Reed A.E., Curtis L.A., Weinhold F.A. Intermolecular interactions from a natural bond orbital, donor-acceptor viewpoint. Chem. Rev. 1988;88:899–926. doi: 10.1021/cr00088a005. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bernstein J., Davis R.E., Shimoni L. Chang, Patterns in hydrogen bonding: functionality and graph set analysis in crystals. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 1995;34(15):1555–1573. doi: 10.1002/anie.199515551. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hirshfeld F.L. Bonded-atom fragments for describing molecular charge densities. Theoreticachimica Acta. 1977;44(2):129–138. doi: 10.1002/anie.199515551. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Spackman M.A., Jayatilaka D. Hirshfeld surface analysis. CrystEngComm. 2009;11:19–32. doi: 10.1039/B818330A. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Varsanyi G. Freeman; New York: 1985. Assignments for Vibrational Spectra of 700 Benzene Derivatives; Adam Hilger: London, 1974.Fersht, A. Enzyme Structure and Mechanism.https://ui.adsabs.harvard.edu/link_gateway/1975JMoSt..29..383B/doi:10.1016/0022-2860(75)85047-2 [Google Scholar]

- 36.Socrates G. Wiley–Interscience Publication; New York: 1980. Infrared Characteristic Group Frequencies. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Smith Brian C. CRC Press; 1998. Infrared Spectral Interpretation: A Systematic Approach. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lin–Vien D., Colthup N.B., Fately W.G., Grasselli J.G., Bentley F.F. 1991. The Handbook of Infrared and Raman Characteristic Frequencies of Organic Molecules, Academic, New York. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hubert Joe I., Aruldhas G., Kumar S.A., Ramasamy P. Vibrational spectra and phase transition in triglycine sulpho-phosphate. J. Cryst. Res.Technol. 1994;29:685–692. doi: 10.1002/crat.2170290520. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Dollish F., Fately G., Bentley W.G. John Wiley & Sons; New York: 1974. Characteristic Raman Frequencies of Organic Compounds. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Freeman S.K. John Wiley and Sons; New York: 1974. Applications of Laser Raman Spectroscopy. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Michaelian K.H., Ziegler S.M. Vibrational spectra and assignments for series of mono- and dihalonaphthalenes. Appl. Spectrosc. 1973;27:13–21. 10.1366%2F000370273774333966. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Short L.N., Thompson H.W. Infra-red spectra of derivatives of pyrimidine. J. Chem. Soc. 1952;38:168–187. doi: 10.1039/JR9520000168. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Smith Brian C. CRC Press; 2011. Infrared Spectral Interpretation: A Systematic Approach. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Nyquist R.A. Factors affecting infrared group frequencies: carbonyl stretching absorption bands, sadtler. Appl. Spectrosc. 1986;40(3):336–339. 10.1366%2F0003702864509105. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Jeffrey G.A., Saenger W. New York; Springer-Verlag: 1991. Hydrogen Bonding in Biological Structures. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Rajamani T., Muthu S., Karabacak M. Electronic absorption, vibrational spectra, nonlinear optical properties, NBO analysis and thermodynamic properties of N-(4-nitro-2-phenoxyphenyl) methanesulfonamide molecule by ab initio HF and density functional methods. Spectrochim. ActaA. 2013;108 doi: 10.1016/j.saa.2013.01.090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Lin-Vien Daimay, Colthup Norman. F.F. Bentley, Infrared and Raman characteristics Frequencies of Organic Compounds, Academic Press; Jeanette Grasselli: 1991. William Fateley. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Lipinski C.A. Lead-and drug-like compounds: the rule-of-five revolution. Drug Discov. Today Technol. 2004;1(4):337–341. doi: 10.1016/j.ddtec.2004.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Walters W.P., Murcko M.A. Prediction of drug-likeness. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 2002;54(3):255–271. doi: 10.1016/s0169-409x(02)00003-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Clark D.E., Pickett S.D. Computational methods for the prediction of drug-likeness. Drug Discov. Today. 2000;5(2):49–58. doi: 10.1016/s1359-6446(99)01451-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Tian S., Wang J., Li Y., Li, Xu L., Hou T. The application of in silico drug-likeness predictions in pharmaceutical research. Advanced drug delivery reviews. 2015;86:2–10. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2015.01.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Ursu O., Rayan A., Goldblum A., Oprea T. Understanding drug-likeness. Wiley Interdiscip. Rev. Comput. Mol. Sci. 2011;5:760–781. doi: 10.1002/wcms.52. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Egan W.J., Walters W.P., Murcko M.A. Guiding molecules towards drug-likeness. Current Opinion in Drug Discovery & Development. 2002;5(4):540–549. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Cheng Feixiong, Li Weihua, Zhou Yadi, Shen Jie, Wu Zengrui, Liu Guixia, Lee Philip W. Yun Tang, admetSAR: a comprehensive source and free tool for assessment of chemical ADMET properties. J. Chem. Inf. Mode. 2012;52(11) doi: 10.1021/ci300367a. 3099-3015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Soga S., Shirai H., Kobori M., Hirayama Use of amino acid composition to predict ligand-binding sites. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 2007;47(2):400–406. doi: 10.1021/ci6002202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Escuder-Gilabert L., Molero-Monfort M., Villanueva-Camañas R.M., Sagrado S., Medina-Hernández M.J. Potential of biopartitioning micellar chromatography as an in vitro technique for predicting drug penetration across the blood–brain barrier. J. Chromatogr. B. 2004;807:193–201. doi: 10.1016/j.jchromb.2004.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Zhang L., Brett C.M. Giacomini KMJArop, toxicology, role of organic cation transporters in drug absorption and elimination. Annu. Rev. Pharmacol. Toxicol. 1998;38(1):431–460. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pharmtox.38.1.431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Uttamsingh Vinita, Lu Chuang, Miwa Gerald, Gan Liang-Shang. Relative contributions of the five major human cytochromes P450, 1A2, 2C9, 2C19, 2D6, and 3A4, to the hepatic metabolism of the proteasome inhibitor bortezomib. Drug Metab. Dispos. 2005;33(11):1723–1728. doi: 10.1124/dmd.105.005710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Forman D. Ames, the Ames test, and the causes of cancer. BMJ. 1991;303(6800):428–429. doi: 10.1136/bmj.303.6800.428. 10.1136%2Fbmj.303.6800.428. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Mortelmans K. Zeiger EJMrf, mutagenesis mmo. The Ames Salmonella/microsome mutagenicity assay. Mutation Research. 2000;455:29–60. doi: 10.1016/s0027-5107(00)00064-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Sanguinetti M.C., Tristani-Firouzi M.J.N. hERG potassium channels and cardiac arrhythmia. Nature. 2006;440(7083):463–4699. doi: 10.1038/nature04710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Dai W., Zhang B., Su H., Li J., Zhao Y., Xie X., Jin Z., Liu F., Li C., Li Y., Bai F. Structure-based design of antiviral drug candidates targeting the SARS-CoV-2 main protease. Science. 2020 Apr 22;368(6497):1331–1335. doi: 10.1126/science.abb4489. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Morris G.M., M. Lim-Wilby. Molecular docking, InMolecularmodeling of proteins Humana Press, chapter. 2008;19:365–382. doi: 10.1007/978-1-59745-177-2_19. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Brooijmans N. Kuntz ID, Molecular recognition and docking algorithms. Annu. Rev. Biophys. 2003;32(1):335–373. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biophys.32.110601.142532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Shoichet B.K., Mc Govern S.L., Wei B., Irwin J.J. Lead discovery using molecular docking. Current opinion in chemical biology. 2002;6(4):439–446. doi: 10.1016/s1367-5931(02)00339-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Jones G., Willett P. Glen RC, Leach AR, R. Taylor, Development and validation of a genetic algorithm for flexible docking. J. Mol. Biol. 1997;267(3):727–748. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1996.0897. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Taylor R.D., Jewsbury P.J., Essex J.W. A review of protein-small molecule docking methods. J. Comput. Aided Mol. Des. 2002;16(3):151–166. doi: 10.1023/a:1020155510718. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Morris G.M., Huey R., Lindstrom W., Sanner M.F., Belew R.K., Goodsell D.S., Olson A.J. AutoDock4 and AutoDockTools4: automated docking with selective receptor flexibility. J. Comput. Chem. 2009;16:2785–2791. doi: 10.1002/jcc.21256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Gasteiger J., Marsili M. Iterative partial equalization of orbital electronegativity-a rapid access to atomic charges. Tetrahedron. 1980;36(22):3219–3228. doi: 10.1016/0040-4020(80)80168-2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Morris G.M., Goodsell D.S., Halliday R.S., Huey R., Hart W.E., Belew R.K., Olson A.J. Automated docking using a Lamarckian genetic algorithm and an empirical binding free energy function. J. Comput. Chem. 1998;19(14):1639–1662. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1096-987X(19981115)19:14%3C1639::AID-JCC10%3E3.0.CO;2-B. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Buller A.R., Townsend C.A. Intrinsic evolutionary constraints on protease structure, enzyme acylation, and the identity of the catalytic triad. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2013;110(8):E653–E661. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1221050110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary tables